Abstract

Background

Naproxen, a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug, is used to treat various painful conditions including postoperative pain, and is often administered as the sodium salt to improve its solubility. This review updates a 2004 Cochrane review showing that naproxen sodium 550 mg (equivalent to naproxen 500 mg) was effective for treating postoperative pain. New studies have since been published.

Objectives

To assess efficacy, duration of action, and associated adverse events of single dose oral naproxen or naproxen sodium in acute postoperative pain in adults.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Oxford Pain Relief Database for studies to October 2008.

Selection criteria

Randomised, double blind, placebo‐controlled trials of single dose orally administered naproxen or naproxen sodium in adults with moderate to severe acute postoperative pain.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. Pain relief or pain intensity data were extracted and converted into the dichotomous outcome of number of participants with at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours, from which relative risk and number‐needed‐to‐treat‐to‐benefit (NNT) were calculated. Numbers of participants using rescue medication over specified time periods, and time to use of rescue medication, were sought as additional measures of efficacy. Information on adverse events and withdrawals were collected.

Main results

The original review included 10 studies with 996 participants. This updated review included 15 studies (1509 participants); 11 assessed naproxen sodium and four naproxen. In nine studies (784 participants) using 500/550 mg naproxen or naproxen sodium the NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours was 2.7 (95% CI 2.3 to 3.2). No dose response was demonstrated over the range 200/220 mg to 500/550 mg, but limited data was identified. Median time to use of rescue medication was 8.9 hours for naproxen 500/550 mg and 2.0 hours for placebo. Use of rescue medication was significantly less common with naproxen than placebo. Associated adverse events were generally of mild to moderate severity and rarely led to withdrawal.

Authors' conclusions

Doses equivalent to 500 mg and 400 mg naproxen administered orally provided effective analgesia to adults with moderate to severe acute postoperative pain. About half of participants treated with these doses experienced clinically useful levels of pain relief, compared to 15% with placebo, and half required additional medication within nine hours, compared to two hours with placebo. Associated adverse events did not differ from placebo.

Plain language summary

Single dose oral naproxen and naproxen sodium for acute postoperative pain in adults

This review assessed evidence from 1509 participants in 15 randomised, double blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trials of naproxen or naproxen sodium (a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug) in adults with moderate to severe acute postoperative pain. At doses equivalent to 500 mg and 400 mg, orally administered naproxen provides effective analgesia. About half of those treated experienced at least half pain relief over four to six hours, and the effects lasted, on average, up to nine hours. Associated adverse events did not differ from placebo, but these studies are of limited use for studying adverse effects.

Background

This review is an update of a previously published review in The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 4, 2004) on 'Single dose oral naproxen and naproxen sodium for acute postoperative pain' (Mason 2004). The title now states that the review is limited to adults.

Acute pain occurs as a result of tissue damage either accidentally due to an injury or as a result of surgery. Acute postoperative pain is a manifestation of inflammation due to tissue injury. The management of postoperative pain and inflammation is a critical component of patient care. The aim of this series of reviews is to present evidence for relative analgesic efficacy through indirect comparisons with placebo, in very similar trials performed in a standard manner, with very similar outcomes, and over the same duration. Such relative analgesic efficacy does not in itself determine choice of drug for any situation or patient, but guides policy‐making at the local level.

Recent reviews include lumiracoxib (Roy 2007), paracetamol (Toms 2008), and celecoxib (Derry 2008), and the series will include updates of existing reviews like ibuprofen (Collins 1999) and aspirin (Oldman 1999), in addition to new reviews such as ketoprofen and dexketoprofen (Barden 2008), lornoxicam (Hall 2008), diflunisal (Moore 2008), and parecoxib (Lloyd 2008).

Single dose trials in acute pain are commonly short in duration, rarely lasting longer than 12 hours. The numbers of participants is small, allowing no reliable conclusions to be drawn about safety. To show that the analgesic is working it is necessary to use placebo (McQuay 2005). There are clear ethical considerations in doing this. These ethical considerations are answered by using acute pain situations where the pain is expected to go away, and by providing additional analgesia, commonly called rescue analgesia, if the pain has not diminished after about an hour. This is reasonable, because not all participants given an analgesic will have significant pain relief. Approximately 18% of participants given placebo will have significant pain relief (Moore 2006), and up to 50% may have inadequate analgesia with active medicines. The use of additional or rescue analgesia is hence important for all participants in the trials.

Clinical trials measuring the efficacy of analgesics in acute pain have been standardised over many years. Trials have to be randomised and double blind. Typically, in the first few hours after an operation, or following discontinuation of patient controlled analgesia, patients develop pain that is moderate to severe in intensity, and will then be given the test analgesic or placebo. Pain is measured using standard pain intensity scales immediately before the intervention, and then using pain intensity and pain relief scales over the following four to six hours for shorter acting drugs, and up to 12 or 24 hours for longer acting drugs. Pain relief of half the maximum possible pain relief or better (at least 50% pain relief) is typically regarded as a clinically useful outcome. For patients given rescue medication it is usual for no additional pain measurements to be made, and for all subsequent measures to be recorded as initial pain intensity or baseline (zero) pain relief (baseline observation carried forward). This process ensures that analgesia from the rescue medication is not wrongly ascribed to the test intervention. In some trials the last observation is carried forward, which gives an inflated response for the test intervention compared to placebo, but the effect has been shown to be negligible over four to six hours (Moore 2005). Patients usually remain in the hospital or clinic for at least the first six hours following the intervention, with measurements supervised, although they may then be allowed home to make their own measurements in trials of longer duration.

Clinicians prescribe non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on a routine basis for a range of mild‐to‐moderate pain. NSAIDs are the most commonly prescribed analgesic medications worldwide, and their efficacy for treating acute pain has been well demonstrated (Moore 2003). They reversibly inhibit cyclooxygenase (prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase), the enzyme mediating production of prostaglandins and thromboxane A2 (FitzGerald 2001). Prostaglandins mediate a variety of physiological functions such as maintenance of the gastric mucosal barrier, regulation of renal blood flow, and regulation of endothelial tone. They also play an important role in inflammatory and nociceptive processes. However, relatively little is known about the mechanism of action of this class of compounds aside from their ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase‐dependent prostanoid formation (Hawkey 1999). Since NSAIDs do not depress respiration and do not impair gastro‐intestinal motility, as do opioids (BNF 2002), they are clinically useful for treating pain after minor surgery and day surgery, and have an opiate‐sparing effect after more major surgery (Grahame‐Smith 2002).

Naproxen is an NSAID much prescribed worldwide, and is the most commonly prescribed NSAID in the USA. Naproxen is often prescribed as the sodium salt (naproxen sodium) to improve its solubility for oral administration. Naproxen sodium 550 mg, equivalent to 500 mg of naproxen (Martindale 1999), is considered an effective dose for treating postoperative pain (Rasmussen 1993). Specific data for the frequency of naproxen administration for postoperative pain relief are unavailable. However, in England in 2007 there were over 1.3 million prescriptions for oral naproxen and naproxen sodium in primary care (PCA 2007). A major concern regarding the use of conventional NSAIDs postoperatively is the possibility of bleeding from both the operative site (because of the inhibition of platelet aggregation) (Forrest 2002) and from the upper gastrointestinal tract, (especially in patients stressed by surgery, the elderly, frail, or dehydrated). Other potentially serious adverse events include acute liver injury, acute renal injury, heart failure, and adverse reproductive outcomes (Hernandez‐Diaz 2001). However, such complications are more likely to occur with chronic use and NSAIDs generally present fewer risks if used in the short term, as in the treatment of postoperative pain (Rapoport 1999).

The previous version of this Cochrane review by Mason 2004, found ten studies, in which 582 participants received active treatment (505 naproxen sodium, 77 with naproxen) and 414 received placebo. For doses equivalent to 400 to 500 mg naproxen, between four and five participants needed to be treated for one to achieve at least 50% pain relief who would not have done so with placebo. The median time to use of rescue medication was 7.9 hours with naproxen, compared to 2.9 hours for placebo, and there was no significant difference in numbers of participants experiencing any adverse event. Since that review, a number of new studies have been published, which has permitted calculation of more robust estimates of both efficacy and harm.

Objectives

To evaluate the analgesic efficacy and safety of oral naproxen or naproxen sodium in the treatment of acute postoperative pain, using methods that permit comparison with other analgesics evaluated in the same way, using wider criteria of efficacy recommended by an in‐depth study at the individual patient level (Moore 2005).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were included if they were full publications of double blind trials of a single dose of oral naproxen or naproxen sodium against placebo for the treatment of moderate to severe postoperative pain in adults, with at least ten participants randomly allocated to each treatment group. Multiple dose studies were included if appropriate data from the first dose were available, and cross‐over studies were included provided that data from the first arm were presented separately.

Studies were excluded if they were:

posters or abstracts not followed up by full publication;

reports of trials concerned with pain other than postoperative pain (including experimental pain);

studies using healthy volunteers;

studies where pain relief was assessed by clinicians, nurses or carers (i.e., not patient‐reported);

studies of less than four hours' duration or which failed to present data over four to six hours post‐dose.

Types of participants

Studies of adult participants (15 years old or above) with established moderate to severe postoperative pain were included. For studies using a visual analogue scale (VAS), pain of at least moderate intensity was assumed when the VAS score was greater than 30 mm (Collins 1997). Studies of participants with postpartum pain were included provided the pain investigated resulted from episiotomy or Caesarean section (with or without uterine cramp). Studies investigating participants with pain due to uterine cramps alone were excluded.

Types of interventions

Orally administered naproxen or naproxen sodium or matched placebo for relief of postoperative pain.

Types of outcome measures

Data collected included the following:

characteristics of participants;

pain model;

patient‐reported pain at baseline (physician, nurse, or carer reported pain was not included in the analysis);

patient‐reported pain relief and/or pain intensity expressed hourly over four to six hours using validated pain scales (pain intensity and pain relief in the form of VAS or categorical scales, or both), or reported total pain relief (TOTPAR) or summed pain intensity difference (SPID) at four to six hours;

patient‐reported global assessment of treatment (PGE), using a standard five‐point scale

number of participants using rescue medication, and the time of assessment;

time to use of rescue medication;

withdrawals ‐ all cause, adverse event;

adverse events ‐ participants experiencing one or more, and any serious adverse event, and the time of assessment.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched:

Cochrane CENTRAL (to December 2002 for original search and January 2003 to October 2008 for the update);

MEDLINE via Ovid (1966 to December 2002 for the original search and 2002 to October 2008 for the update);

EMBASE via Ovid (1980 to December 2002 for the original search and 2002 to October 2008 for the update);

Oxford Pain Database (Jadad 1996a).

Reference lists of retrieved articles were searched.

See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy, Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy, and Appendix 3 for the Cochrane CENTRAL search strategy.

Language

No language restriction was applied.

Unpublished studies

Abstracts, conference proceedings and other grey literature were not searched. Merck provided details of two unpublished studies for the original review, but manufacturers were not contacted for this update.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed and agreed the search results for studies that might be included in the updated review. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or referral to a third review author.

Quality assessment

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for quality using a five‐point scale (Jadad 1996b).

The scale used is as follows:

Is the study randomised? If yes give one point.

Is the randomisation procedure reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point.

Is the study double blind? If yes then add one point.

Is the double blind method reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point.

Are the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts described? If yes add one point.

The results are described in the 'Methodological quality of included studies' section below, and 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Data management

Data were extracted by two review authors and recorded on a standard data extraction form. Data suitable for pooling were entered into RevMan 5.0.14.

Data analysis

QUOROM guidelines were followed (Moher 1999). For efficacy analyses we used the number of participants in each treatment group who were randomised, received medication, and provided at least one post‐baseline assessment. For safety analyses we used number of participants who received study medication in each treatment group. Analyses were planned for different doses. Sensitivity analyses were planned to investigate any effect of pain model (dental versus other postoperative pain), trial size (39 or fewer versus 40 or more per treatment arm), and quality score (two versus three or more) on the primary outcome. A minimum of two studies and 200 participants were required for any analysis (Moore 1998).

Primary outcome

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

For each study, mean TOTPAR (total pain relief) or SPID (summed pain intensity difference) for active and placebo groups were converted to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID by division into the calculated maximum value (Cooper 1991). The proportion of participants in each treatment group who achieved at least 50%maxTOTPAR was calculated using verified equations (Moore 1996; Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). These proportions were then converted into the number of participants achieving at least 50%maxTOTPAR by multiplying by the total number of participants in the treatment group. Information on the number of participants with at least 50%maxTOTPAR for active treatment and placebo was then used to calculate relative benefit (RB) and number‐needed‐to‐treat‐to‐benefit (NNT). Pain measures accepted for the calculation of TOTPAR or SPID were:

five‐point categorical pain relief (PR) scales with comparable wording to "none, slight, moderate, good or complete";

four‐point categorical pain intensity (PI) scales with comparable wording to "none, mild, moderate, severe";

VAS for pain relief;

VAS for pain intensity.

If none of these measures were available, numbers of participants reporting "very good or excellent" on a five‐point categorical global scale with the wording "poor, fair, good, very good, excellent" were taken as those achieving at least 50% pain relief (Collins 2001).

Further details of the scales and derived outcomes are in the glossary (Appendix 4).

Secondary outcomes:

1. Use of rescue medication

Numbers of participants requiring rescue medication were used to calculate relative risk (RR) and numbers needed to treat to prevent (NNTp) use of rescue medication for treatment and placebo groups. Median (or mean) time to use of rescue medication was used to calculate the weighted mean of the median (or mean) for the outcome. Weighting was by number of participants.

2. Adverse events

Numbers of participants reporting adverse events for each treatment group were used to calculate RR and numbers needed to treat to harm (NNH) estimates for:

any adverse event;

any serious adverse event (as reported in the study);

withdrawal due to an adverse event.

3. Withdrawals

Withdrawals for reasons other than lack of efficacy (participants using rescue medication ‐ see above) and adverse events were noted, as were exclusions from analysis where data were presented.

Relative benefit or risk estimates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed‐effect model (Morris 1995). NNT, NNTp and NNH with 95% CI were calculated using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). A statistically significant difference from control was assumed when the 95% CI of the relative benefit did not include the number one.

Homogeneity of studies was assessed visually (L'Abbé 1987). The z test (Tramèr 1997) was used to determine if there was a significant difference between NNTs for different doses of active treatment, or between groups in the sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

The original review included ten studies (Brown 1997; Forbes 1986; Fricke 1993; Gottesdiener 1999; Kiersch 1993; Kiersch 1994; Mahler 1976; Merck 1997a; Merck 1997b; Reicin 2001). The new searches identified seven potentially relevant studies. Two of these were excluded after reading the full publication (Demirel 2005; Yilmaz 2006), and five new studies were included (Binning 2007; Chan 2005; Hill 2006; Malmstrom 2004; Rasmussen 2005). In total 15 studies are included and 37 studies are excluded in this review update. Details are in the 'Characteristics of included studies' and the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Two of the previously included studies remain unpublished. These studies were conducted by the pharmaceutical company Merck & Co Inc, Rahway, New Jersey, USA, and provided data from trials where naproxen sodium 550 mg was used as an active comparator for rofecoxib in acute dental pain (Merck 1997a; Merck 1997b). One study (Frezza 1985) was previously classified as "awaiting translation", and has been moved to "excluded studies" because we were not able to obtain a copy in the UK.

In the 15 included studies, a total of 836 participants received active treatment (626 naproxen sodium; 210 naproxen) and 673 received placebo.

Naproxen 200 mg or naproxen sodium 220 mg was used in two treatment arms (Kiersch 1993; Mahler 1976), 400 mg or 440 mg in three treatment arms (Fricke 1993; Kiersch 1994; Mahler 1976), 500 mg or 550 mg in ten treatment arms (Binning 2007; Brown 1997; Chan 2005; Forbes 1986; Gottesdiener 1999; Hill 2006; Malmstrom 2004; Merck 1997a; Merck 1997b; Reicin 2001) and naproxen sodium 1100 mg slow release in one treatment arm (Rasmussen 2005).

The majority of studies used the sodium salt, with only four not doing so (Binning 2007; Chan 2005; Hill 2006; Mahler 1976). None directly compared different formulations, and only one (Mahler 1976) compared different doses of the same formulation.

Nine studies enrolled participants with dental pain following extraction of at least one impacted third molar (Forbes 1986; Fricke 1993; Gottesdiener 1999; Hill 2006; Kiersch 1993; Kiersch 1994; Malmstrom 2004; Merck 1997a; Merck 1997b), one enrolled participants with pain following arthroscopic knee surgery (Binning 2007), and five enrolled participants with pain following major orthopaedic, gynaecological, abdominal, thoracic or general surgery (Brown 1997; Chan 2005; Mahler 1976; Rasmussen 2005; Reicin 2001).

Trial duration was six hours in one study, eight hours in two studies, 12 hours in seven studies, and 24 hours in five studies. One study (Chan 2005) was a multiple dose study, but reported data separately for the first dose.

Full details are in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality of included studies

All included studies were both randomised and double blind. Six studies were given a quality score of five (Chan 2005; Forbes 1986; Gottesdiener 1999; Hill 2006; Malmstrom 2004; Rasmussen 2005), four a score of four (Binning 2007; Brown 1997; Kiersch 1994; Reicin 2001), and five a score of three (Fricke 1993; Kiersch 1993; Mahler 1976; Merck 1997a; Merck 1997b).

Full details are in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Effects of interventions

All 15 studies provided some data for quantitative analysis. Fourteen studies contributed data to the primary efficacy outcome. One trial (Hill 2006) reported the data in a form that could not be used to calculate number of participants with 50% pain relief, and a request for further data from the manufacturer was not answered.

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

Naproxen 200 mg and naproxen sodium 220 mg versus placebo

Two studies with 202 participants provided data (Kiersch 1993; Mahler 1976), (Table 1).

1. Summary of outcomes ‐ analgesia and rescue medication.

| Analgesia | Rescue medication | |||||

| Study ID | Treatment | PI or PR | Number with 50% PR | PGR: v good or excellent | Median time to use (hr) | % using |

| Binning 2007 | (1) Naproxen 500 mg, n = 34 (2) Nimesulide, 100 mg, n = 29 (3) Placebo, n = 31 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 12.5 (3) 13.0 |

(1) 20/34 (3) 19/31 |

no usable data | no data | at 8 hours: (1) 41 (3) 47 |

| Brown 1997 | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg n = 46 (2) Bromfenac 25 mg, n = 44 (3) Bromfenac 50 mg, n = 43 (4) Ketorolac, 30 mg (IM), n = 42 (5) Placebo, n = 43 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 7.8 (5) 3.9 |

(1) 15/46 (5) 4/43 |

at 12 hrs: (1) 31/45 (5) 17/41 |

no data | 4 pts in total by 12 hours |

| Chan 2005 | (1) Naproxen 500 mg, n = 60 (2) Lumiracoxib 400 mg, n = 60 (3) Placebo, n = 60 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.3 (3) 5.6 |

(1) 24/60 (3) 12/60 |

no usable data | (1) 3.9 (3) 2.0 |

at 12 hours: (1) 78 (2) 90 |

| Forbes 1986 | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 38 (2) Codeine sulphate 60 mg, n = 44 (3) Naproxen sodium 550 mg + codeine sulphate 60 mg, n = 38 (4) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 36 (5) Placebo, n = 42 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 12.8 (5) 4.1 |

(1) 22/38 (5) 5/42 |

no usable data | (1) 7.9 (5) 1.9 |

at 12 hours: (1) 63 (5) 85 |

| Fricke 1993 | (1) Naproxen sodium 440 mg, n = 81 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 81 (3) Placebo, n = 39 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 11.6 (3) 2.9 |

(1) 43/81 (2) 2/39 |

no usable data | (1) 7.0 (3) 1.1 |

at 12 hours: (1) 64 (3) no data |

| Gottesdiener 1999 | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 25 (2) DFP 5 mg, n = 48 (3) DFP 25 mg, n = 50 (4) DFP 50 mg, n = 48 (5) Placebo, n = 25 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 13.0 (5) 3.4 |

(1) 15/25 (5) 2/25 |

at 8 hours: (1) 12/25 (5) 2/25 |

(1) 8.0 (5) 1.6 |

at 24 hours: (1) 60 (5) 92 |

| Hill 2006 | (1) Naprox 500 mg, n = 39 (2) AZD3582 375 mg, n = 41 (3) AZD3582 750 mg, n = 37 (4) AZD3582 1500 mg, n = 42 (5) AZD3582 2250 mg, n = 41 (6) Placebo, n = 42 |

no usable data | no data | no data | (1) >8 (6) 2.4 |

no data |

| Kiersch 1993 | (1) Naproxen sodium 220 mg, n = 80 (2) Ibuprofen 200 mg, n = 81 (3) Placebo, n = 42 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 11.5 (3) 3.7 |

(1) 42/80 (3) 4/42 |

at 12 hours: (1) 46/80 (3) 4/42 |

(1) 9.4 (3) 2.0 |

at 12 hours: (1) 51 (3) 90 |

| Kiersch 1994 | (1) Naproxen sodium 440 mg, n = 92 (2) Acetaminophen 1000 mg, n = 89 (3) Placebo, n = 45 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 10.5 (3) 3.1 |

(1) 43/92 (3) 3/45 |

no data | (1) 9.9 (3) 2.0 |

no data |

| Mahler 1976 | (1) Naproxen 200 mg, n = 40 (2) Naproxen 400 mg, n = 37 (3) Aspirin 600 mg, n = 39 (4) Aspirin 1200 mg, n = 41 (5) Placebo, n = 40 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 7.4 (2) 10.4 (5) 6.2 |

(1) 12/40 (2) 17/37 (5) 9/40 |

no data | no data | no usable data |

| Malmstrom 2004 | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 50 (2) Etoricoxib 120 mg, n = 50 (3) Paracetamol+Codeine 600/60 mg, n = 50 (4) Placebo, n = 50 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 15.6 (4) 4.2 |

(1) 37/50 (4) 6/50 |

at 8 hours: (1) 42/51 (4) 7/50 |

(1) 20.8 (4) 1.6 |

at 24 hours: (1) 27/51 (4) 49/50 |

| Merck 1997a | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 38 (2) MK‐0966 7.5 mg, n = 38 (3) MK‐0966 25 mg, n = 38 (4) MK‐0966 50 mg, n = 38 (5) MK‐0966 100 mg, n = 38 (6) Placebo, n = 38 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 15.0 (6) 2.6 |

(1) 27/38 (6) 1/38 |

no data | (1) 12 (6) 1.6 |

at 12 hours: (1) 43 (6) 57 |

| Merck 1997b | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 48 (2) MK‐0966 12.5 mg, n = 72 (3) MK‐0966 25 mg, n = 72 (4) MK‐0966 50 mg, n = 72 (5) Placebo, n = 48 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.9 (5) 1.7 |

(1) 21/48 (5) 0/48 |

no data | (1) 5.4 (5) 1.5 |

at 12 hours: (1) 75 (5) 76 |

| Rasmussen 2005 | (1) Naproxen sodium controlled release 1100 mg, n = 73 (2) Etoricoxib 120 mg, n = 80 (3) Placebo, n = 75 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 8.7 (3) 4.4 |

(1) 27/73 (3) 10/75 |

no usable data | (1) 5.6 (3) 2.6 |

at 24 hours: (1) 55/73 (3) 74/75 |

| Reicin 2001 | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 55 (2) Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 110 (3) Placebo, n = 53 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.8 (3) 5.4 |

(1) 24/55 (3) 10/53 |

no usable data | (1) 5.9 (3) 2.8 |

at 12 hours: (1) 38/55 (3) 49/53 |

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with naproxen 200 mg or naproxen sodium 220 mg was 45% (54/120; range 30% to 53%), and with placebo was 16% (13/82; range 10% to 23%). The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.9 (1.6 to 5.1), giving an NNT of at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours of 3.4 (2.4 to 5.8).

Naproxen 400 mg and naproxen sodium 440 mg versus placebo

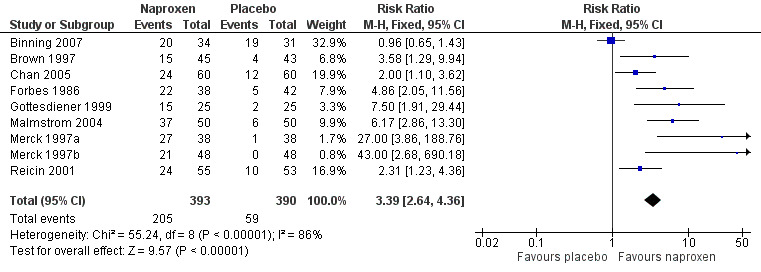

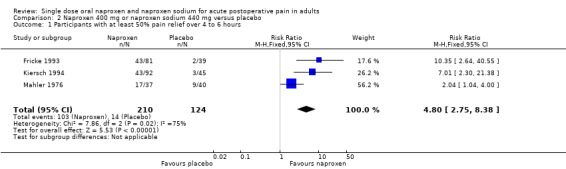

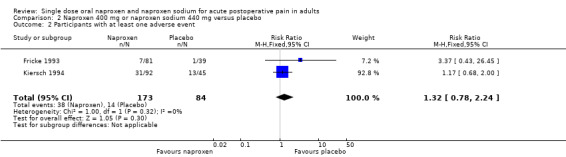

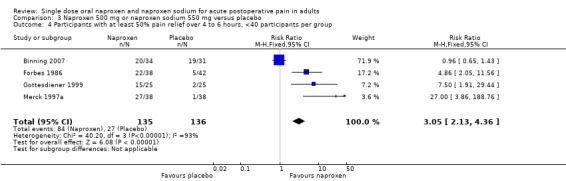

Three studies with 334 participants provided data (Fricke 1993; Kiersch 1994; Mahler 1976), (Table 1; Figure 1).

1.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Naproxen 400 mg or naproxen sodium 440 mg versus placebo, outcome: 2.1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with naproxen 400 mg or naproxen sodium 440 mg was 49% (103/210; 46% to 53%), and with placebo was 11% (14/124; 5% to 23%). The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 4.8 (2.8 to 8.4), giving an NNT of at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours of 2.7 (2.2 to 3.5).

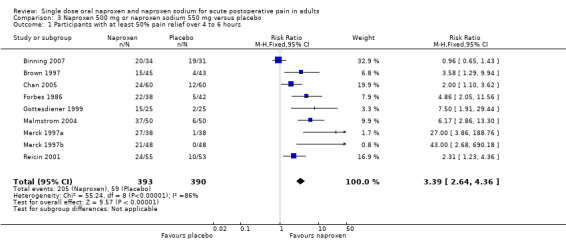

Naproxen 500 mg and naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo

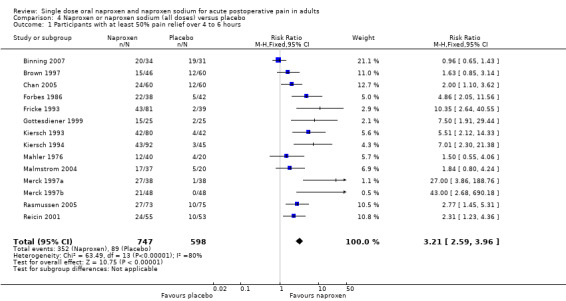

Nine studies with 784 participants provided data (Binning 2007; Brown 1997; Chan 2005; Forbes 1986; Gottesdiener 1999; Malmstrom 2004; Merck 1997a; Merck 1997b; Reicin 2001), (Table 1; Figure 2).

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo, outcome: 3.1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg was 52% (200/394; 33% to 74%), and with placebo was 15% (59/390; 0% to 20%). The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 3.4 (2.6 to 4.4), giving an NNT of at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours of 2.7 (2.3 to 3.3).

There was no significant dose response over the range covered in these trials. Three people would need to be treated with doses equivalent to 400 mg or 500 mg naproxen for one to achieve at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours, who would not have done so if treated with placebo.

| A. Summary of results: number of participants with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | |||||

| Dose (mg) | Studies | Participants | Naproxen (%) | Placebo (%) | NNT (95%CI) |

| 200/220 | 2 | 202 | 45 | 16 | 3.4 (2.4 to 5.8) |

| 400/440 | 3 | 334 | 49 | 11 | 2.7 (2.2 to 3.5) |

| 500/550 | 9 | 784 | 52 | 15 | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.2) |

Sensitivity analysis of primary outcome

Methodological quality

All studies scored three or more for quality, so no sensitivity analysis was carried out for this criterion.

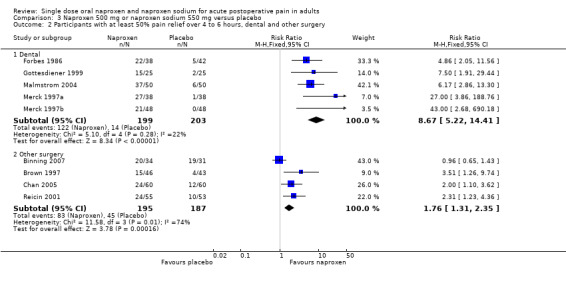

Pain model: dental versus other surgery

Eight studies in dental pain and seven in other types of surgery reported the primary outcome. In dental studies the event rates with active treatment ranged from 44% to 74%, and with placebo from 0% to 12%. In other types of surgery the event rates with active treatment ranged from 30% to 59%, and with placebo from 9% to 61%.

In participants with dental pain, for all doses combined, the proportion achieving at least 50% pain relief with naproxen or naproxen sodium was 55% (250/452) and with placebo was 7% (23/329). The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 8.1 (5.4 to 12), and the NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours was 2.1 (2.6 to 3.4). In participants with pain following other types of surgery, for all doses combined, the proportion achieving at least 50% pain relief with naproxen or naproxen sodium was 40% (139/345) and with placebo was 21% (73/342). The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 1.9 (1.5 to 2.4), and the NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours was 5.3 (3.9 to 8.2) (z = 6.6, P < 0.00006).

For 500 mg naproxen or 550 mg naproxen sodium, in dental studies (five studies, 402 participants), the relative benefit compared to placebo was 8.7 (5.2 to 14) and the NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours was 1.8 (1.6 to 2.1), while for studies in other surgery the relative benefit was 1.8 (1.3 to 2.4) and the NNT was 5.4 (3.6 to 11) (z = 5.9, P < 0.00006) (Figure 3). Excluding the single trial in arthroscopic knee surgery (Binning 2007) did not significantly change this result (NNT 4.5 (3.1 to 7.7)).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo, outcome: 3.4 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, dental and other surgery.

Trial size

Nine studies had 40 or more participants in both treatment arms, and three had fewer than 40 participants. For the 500 mg/550 mg dose, there were five studies (two dental, three other surgery, 513 participants) with 40 or more participants and three (two dental, one other surgery, 191 participants) with less than 40 participants. There was no difference for the outcome of at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours between these groups, although the amount of information on which to base a conclusion was limited.

Formulation

All dental studies used naproxen sodium. In studies in other types of surgery, three (four treatment arms) used naproxen (Binning 2007; Chan 2005; Mahler 1976), two used naproxen sodium (Brown 1997; Reicin 2001) and one used controlled release naproxen sodium (Rasmussen 2005), at various doses. There were insufficient data for the naproxen group to carry out any statistical analysis.

| B. Sensitivity analysis: number of participants with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | |||||

| Dose (mg) | Studies | Participants | Naproxen (%) | Placebo (%) | NNT (95%CI) |

| All doses Dental | 8 | 781 | 55 | 7 | 2.1 (2.6 to 3.4) |

| All doses Other | 7 | 687 | 40 | 21 | 5.3 (3.9 to 8.2) |

| 500/550 Dental | 5 | 402 | 61 | 7 | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.1) |

| 500/550 Other | 4 | 382 | 43 | 24 | 5.4 (3.6 to 11) |

| 500/550, >40 pts/arm | 5 | 513 | 47 | 13 | 2.9 (2.4 to 3.7) |

| 500/550, <40 pts/arm | 3 | 191 | 64 | 23 | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.6) |

| 500 (naproxen) | 2 | 185 | 47 | 34 | not calculated |

| 550 (naproxen sodium) | 7 | 599 | 54 | 9 | 2.3 (2.0 to 2.7) |

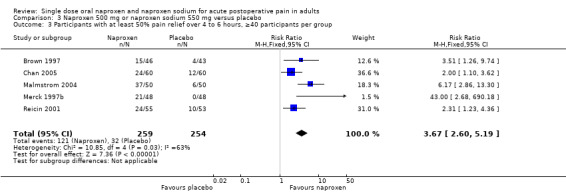

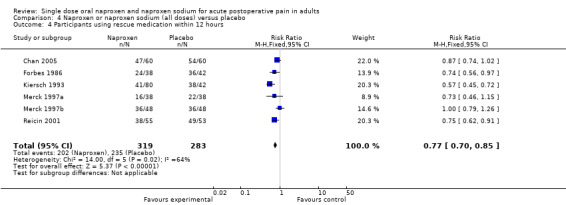

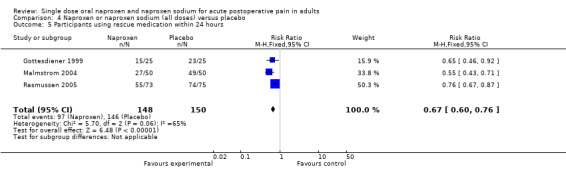

Use of rescue medication

Ten studies reported on participants requiring rescue medication, one at eight hours (Binning 2007), six at 12 hours (Chan 2005; Forbes 1986; Kiersch 1993; Merck 1997a; Merck 1997b; Reicin 2001) and three at 24 hours (Gottesdiener 1999; Malmstrom 2004; Rasmussen 2005), (Table 1).

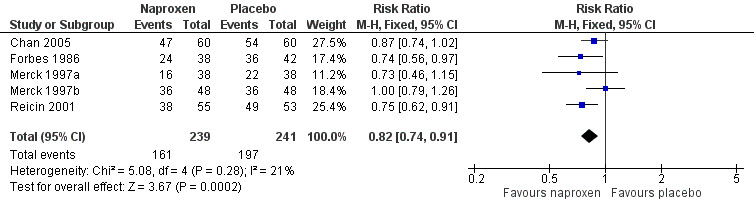

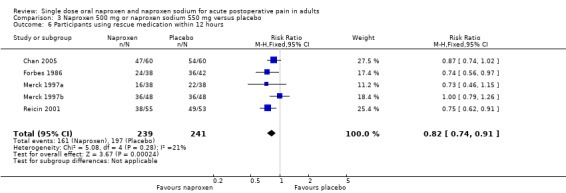

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication at 12 hours was 63% for naproxen (all doses) and 83% for placebo, giving an NNTp of 5.1 (3.8 to 7.8). Four studies were in dental pain and two in other surgery, and doses used were 220 mg (Kiersch 1993) and 500 mg (Chan 2005) naproxen and 550 mg naproxen sodium (Forbes 1986; Merck 1997a; Merck 1997b; Reicin 2001). For 500 mg naproxen or 550 mg naproxen sodium, the NNTp was 6.9 (4.5 to 15) (Figure 4). Seven people would need to be treated with 500 mg naproxen or 550 mg naproxen sodium to prevent one person using rescue medication within 12 hours, who would have done so if treated with the placebo.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo, outcome: 3.8 Participants using rescue medication within 12 hours.

At 24 hours the proportion requiring rescue medication was 66% for naproxen (all doses) and 97% for placebo, giving an NNTp of 3.2 (2.5 to 4.2). Two studies were in dental pain and one in other surgery, and doses used were 550 mg (Gottesdiener 1999; Malmstrom 2004) and 1100 mg SR naproxen sodium (Rasmussen 2005). There were insufficient data for this dose to provide useful information at 24 hours.

| C. Summary of results: weighted mean proportion using rescue medication | |||||

| Time assessed | Studies | Participants | Naproxen (%) | Placebo (%) | NNTp (95%CI) |

| 12 hours (all doses) | 6 | 602 | 63 | 83 | 5.1 (3.8 to 7.8) |

| 24 hours (all doses) | 3 | 298 | 66 | 97 | 3.2 (2.5 to 4.2) |

| 12 hours (500/550) | 5 | 480 | 67 | 82 | 6.9 (4.5 to 15) |

| 24 hours (500/550) | 2 | 150 | 56 | 96 | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.6) |

Twelve studies reported median time to use of rescue medication (Chan 2005; Forbes 1986; Fricke 1993; Gottesdiener 1999; Hill 2006; Kiersch 1993; Kiersch 1994; Malmstrom 2004; Rasmussen 2005; Reicin 2001), (Table 1).

The weighted mean of the median time to use of rescue medication was 8.5 hours for all doses of naproxen combined (679 participants), and two hours for placebo (559 participants). For 500 mg naproxen and 550 mg naproxen sodium (353 participants), the time was very similar at 8.9 hours. Half of participants treated with naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg used rescue medication at nine hours, compared to two hours for those treated with placebo.

| D. Summary of results: weighted mean of median time to use of rescue medication | ||||

| Dose (mg) | Studies | Participants | Naproxen (hrs) | Placebo (hrs) |

| All | 12 | 1238 | 8.5 | 2 |

| 500/550 | 8 | 711 | 8.9 | 2 |

Adverse events

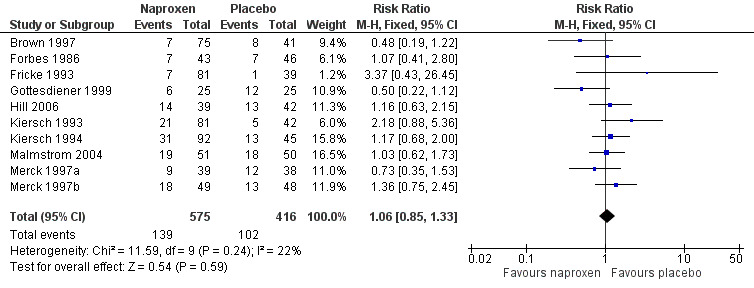

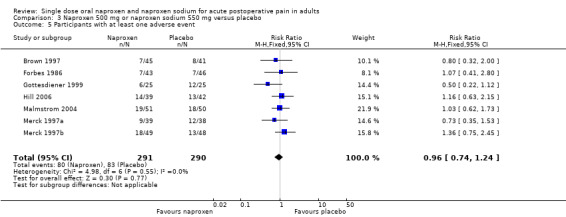

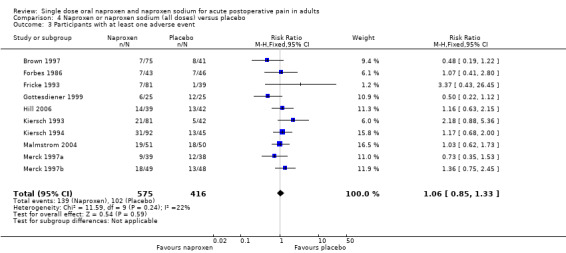

Ten studies reported the number of participants with one or more adverse event for each treatment arm (Brown 1997; Forbes 1986; Fricke 1993; Gottesdiener 1999; Hill 2006; Kiersch 1993; Kiersch 1994; Malmstrom 2004; Merck 1997a; Merck 1997b), (Table 2; Figure 5). The time over which the information was collected was not always explicitly stated and varied between trials, with one study reporting at ten days (Malmstrom 2004), and another possibly at 14 days (Hill 2006). Few studies reported whether adverse event data continued to be collected after rescue medication had been taken. No individual study reported a significant difference between naproxen and placebo, with event rates ranging from 9% to 37% in active treatment arms and 3% to 48% in placebo arms. There was no significant difference between naproxen 400 mg/440 mg or 500 mg/550 mg and placebo treatment arms, where there were sufficient data to combine studies.

2. Summary of outcomes ‐ adverse events and withdrawals.

| Adverse events | Withdrawals | ||||

| Study ID | Treatment | Any | Serious | Adverse event | Other |

| Binning 2007 | (1) Naproxen 500 mg, n = 34 (2) Nimesulide, 100 mg, n = 29 (3) Placebo, n = 31 |

Data not reported for single dose | None | No data | No data |

| Brown 1997 | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg n = 46 (2) Bromfenac 25 mg, n = 44 (3) Bromfenac 50 mg, n = 43 (4) Ketorolac, 30 mg (IM), n = 42 (5) Placebo, n = 43 |

(1) 7/45 (5) 8/41 |

None | No data | (1) I/44 (unable to tolerate medcation) (5) 0/43 |

| Chan 2005 | (1) Naproxen 500 mg, n = 60 (2) Lumiracixib 400 mg, n = 60 (3) Placebo, n = 60 |

No single dose data | No single dose data | No single dose data | No single dose data |

| Forbes 1986 | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 38 (2) Codeine sulphate 60 mg, n = 44 (3) Naproxen sodium 550 mg + codeine sulphate 60 mg, n = 38 (4) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 36 (5) Placebo, n = 42 |

(1) 7/43 (5) 7/46 |

None | None reported | None reported |

| Fricke 1993 | (1) Naproxen sodium 440 mg, n = 81 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 81 (3) Placebo, n = 39 |

(1) 7/81 (3) 1/39 |

None | (1) 1/81 (3) 0/39 |

1 participant excluded for protocol violation |

| Gottesdiener 1999 | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 25 (2) DFP 5 mg, n = 48 (3) DFP 25 mg, n = 50 (4) DFP 50 mg, n = 48 (5) Placebo, n = 25 |

(1) 6/25 (5) 12/25 |

None | None reported | None reported |

| Hill 2006 | (1) Naprox 500 mg, n = 39 (2) AZD3582 375 mg, n = 41 (3) AZD3582 750 mg, n = 37 (4) AZD3582 1500 mg, n = 42 (5) AZD3582 2250 mg, n = 41 (6) Placebo, n = 42 |

(1) 21/81 (3) 5/12 |

None | (1) 0/80 (3) 0/42 |

None reported |

| Kiersch 1993 | (1) Naproxen sodium 220 mg, n = 80 (2) Ibuprofen 200 mg, n = 81 (3) Placebo, n = 42 |

(1) 31/92 (3) 13/45 |

None | (1) 1/92 (3) 0/45 |

None reported |

| Kiersch 1994 | (1) Naproxen sodium 440 mg, n = 92 (2) Acetaminophen 1000 mg, n = 89 (3) Placebo, n = 45 |

(1) 14/39 (6) 13/42 |

None | None | None |

| Mahler 1976 | (1) Naproxen 200 mg, n = 40 (2) Naproxen 400 mg, n = 37 (3) Aspirin 600 mg, n = 39 (4) Aspirin 1200 mg, n = 41 (5) Placebo, n = 40 |

No usable data | No data | No data | No data |

| Malmstrom 2004 | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 50 (2) Etoricoxib 120 mg, n = 50 (3) Paracetamol+Codeine 600/60 mg, n = 50 (4) Placebo, n = 50 |

10 days: (1) 19/51 (4) 18/50 |

None | None | Did not return for post study visit: (1) 0/51 (4) 1/50 |

| Merck 1997a | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 38 (2) MK‐0966 7.5mg, n = 38 (3) MK‐0966 25 mg, n = 38 (4) MK‐0966 50 mg, n = 38 (5) MK‐0966 100 mg, n = 38 (6) Placebo, n = 38 |

(1) 9/39 (2) 12/38 |

No data | No data | No data |

| Merck 1997b | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 48 (2) MK‐0966 12.5 mg, n = 72 (3) MK‐0966 25 mg, n = 72 (4) MK‐0966 50 mg, n = 72 (5) Placebo, n = 48 |

(1) 18/49 (5) 13/48 |

No data | No data | No data |

| Rasmussen 2005 | (1) Naproxen sodium controlled release 1100 mg, n = 73 (2) Etoricoxib 120 mg, n = 80 (3) Placebo, n = 75 |

No data for single dose | No data for single dose | No data for single dose | No data for single dose |

| Reicin 2001 | (1) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 55 (2) Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 110 (3) Placebo, n = 53 |

No data | No data | (1) 2/55 (3) 3/53 |

No data |

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Naproxen or naproxen sodium (all doses) versus placebo, outcome: 4.3 Participants with at least one adverse event.

Adverse events were generally described as mild to moderate in severity. No study reported a serious adverse event during the single dose phase.

| E. Summary of results: participants with at least one adverse event | |||||

| Dose (mg) | Studies | Participants | Naproxen (%) | Placebo (%) | NNH (95%CI) |

| All doses | 10 | 991 | 24 | 25 | not calculated |

| 440 | 2 | 253 | 22 | 17 | not calculated |

| 500/550 | 7 | 581 | 27 | 29 | not calculated |

Withdrawals and exclusions

(Table 2)

Participants who took rescue medication were classified as withdrawals due to lack of efficacy, and details are reported under "Use of rescue medication" above.

Withdrawals and exclusions were not reported consistently, particularly in older studies. Exclusions may not be of any particular consequence in single dose acute pain studies, where most exclusions result from participants not having moderate or severe pain (McQuay 1982). Withdrawals were sometimes reported without stating which treatment groups these referred to, or when withdrawals occurred, i.e., before assessment of analgesia at four to six hours, or at some other point before the end of the trial. Where details were given, withdrawals or exclusions were usually due to protocol violations or adverse events related to the surgical procedure.

Three studies reported adverse event withdrawals. Reicin 2001 reported two in the naproxen sodium (550 mg) arm and three in the placebo arm (events not specified), while Fricke 1993 and Kiersch 1994 reported one each in their naproxen (440 mg) arms due to postoperative vomiting and headache respectively.

Discussion

This updated review includes five additional studies (Binning 2007; Chan 2005; Hill 2006; Malmstrom 2004; Rasmussen 2005) and adds information on 50% more participants treated with 500 mg/550 mg naproxen/naproxen sodium, the most commonly used dose. All the studies were of adequate methodological quality to minimize bias. The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours for 500 mg/550 mg compared to placebo was barely changed at 2.7 (2.3 to 3.3). About half of the participants treated with this dose achieved this level of pain relief, compared with about 15% treated with placebo. There were no additional trials using doses of 200 mg/220 mg or 400 mg/440 mg, and there remains no demonstrable dose response for this outcome.

Indirect comparisons of NNTs for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours in reviews of other analgesics using identical methods indicate that naproxen 500 mg/550 mg has equivalent efficacy to ibuprofen 400 mg (2.7 (2.5 to 3.0) (Collins 1999) and lumiracoxib 400 mg (2.7 (2.2 to 3.5) (Roy 2007), and is better than paracetamol 1000 mg (3.6 (3.2 to 4.1)) (Toms 2008), but is worse than rofecoxib (2.2 (1.9 to 2.4) (Barden 2005). A current listing of reviews of analgesics in the single dose postoperative pain model can be found at www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier.

This review included eight studies in dental pain, with 452 participants treated with naproxen or naproxen sodium, and seven studies in other types of surgery, with 345 participants treated with naproxen or naproxen sodium. Analysing data from the different pain models separately demonstrated a significant difference between the response in the different models for the primary outcome of at least 50% pain relief. Doses were combined for this analysis because no dose response was demonstrated for the primary outcome in these studies, and because similar numbers (the majority of participants) in both groups were treated with 500 mg/550 mg. Compared with dental studies, those in other types of surgery had higher and more variable placebo response rates, and lower response rates with similar variability for naproxen. This result differs from a previous finding that the effect of the pain model is not significant (Barden 2004), possibly reflecting the limited amount of information available with naproxen.

All the studies had fewer than 100 participants per treatment arm, with many having just below or just over the 40 participants selected a priori as a cut‐off for the sensitivity analysis of study size. This set of studies therefore lacked sensitivity for this sensitivity analysis.

The sodium salt of naproxen was introduced to improve its solubility for oral administration. The planned sensitivity analysis for effect of this formulation was limited to non‐dental trials because all the dental studies used the sodium salt. The analysis demonstrated a difference between the two formulations, but the result should be treated with caution because of the small numbers involved.

A slow release formulation of naproxen sodium was tested in one study (Rasmussen 2005) in orthopaedic surgery. The expectation is that this formulation might take longer to achieve its analgesic effect, but that the effect would last longer. This particular study did not appear to do any better than others in the same pain model using half the dose, but no conclusions can safely be drawn on the basis of this single study.

It has been suggested that data on use of rescue medication, whether as a proportion of participants requiring it, or the median time to use of it, might be helpful in assessing the usefulness of an analgesic, and possibly distinguishing between different doses (Moore 2005). There were insufficient data for 200 mg/220 mg and 400 mg/440 mg doses to formally test for a dose response for this outcome, but the results of the individual studies did not suggest that there was one. The median time to use of rescue medication in these trials was almost nine hours, compared with two hours for placebo. This relatively long duration of action compares favourably with analgesics such as paracetamol where the median time is under four hours (Toms 2008). The full implications of the importance of remedication as an outcome awaits completion of other reviews, allowing examination of a substantial body of evidence.

Reporting of data for adverse events, withdrawals (other than lack of efficacy) or exclusions, and handling of missing data was not always complete, although it did appear to be better in the more recent studies. Adverse events were collected using various methods (questioning, patient diary) over different periods of time. This may have included periods after the use of rescue medication, which may cause its own adverse events. Poor reporting of adverse events in acute pain trials have been noted before (Edwards 1999). The usefulness of single dose studies for assessing adverse events is questionable, but it is non‐the‐less reassuring that there was no difference between naproxen (at any dose) and placebo for occurrence of any adverse event, and that serious adverse events and adverse event withdrawals were rare, and generally not thought to be related to the test drug. Long‐term, multiple dose studies should be used for meaningful analysis of adverse events since, even in acute pain settings, analgesics are likely to be used in multiple doses.

Lack of information about withdrawals or exclusions may have led to an overestimate of efficacy, but the effect is probably not significant because it is as likely to be related to poor reporting as poor methods. In single dose studies most exclusions occur for protocol violations such as failing to meet baseline pain requirements, or failing to return for post treatment visits after the acute pain results are concluded. Where patients are treated with a single dose of medication and observed, often "on site" for the duration of the trial, it might be considered unnecessary to report on "withdrawals" if there were none. For missing data it has been shown that over the four to six hour period, there is no difference between baseline observation carried forward, which gives the more conservative estimate, and last observation carried forward (Moore 2005).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Naproxen and naproxen sodium at the most commonly used dose of 500 mg/550 mg is an effective analgesic, providing at least 50% pain relief to about half of treated patients with acute, moderate to severe, postoperative pain. The NNT of 2.7 for at least 50% pain relief, and nine hour average duration of action, compare favourably with other analgesics commonly used for postoperative pain. In single dose, it is associated with a low rate of adverse events, similar to that with placebo. Lower doses (400 mg/440 mg and 200 mg/220 mg) may provide equivalent levels of analgesia. This review suggests that there may be differences in efficacy following different types of surgery.

Implications for research.

Further trials at lower doses could clarify whether they provide useful analgesia. It should always be the goal to use the lowest dose of a drug that provides the desired clinical effect, and lower doses are likely to be associated with fewer adverse events. Further studies in different types of surgery could clarify whether there are clinically important differences in efficacy in different surgical settings. The major implication is for better reporting of clinical trials, in avoiding average information from highly skewed distributions, in providing information about how many patients achieve a clinically useful level of pain relief, and in reporting other outcomes of clinical relevance, such as time to remedication.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 May 2019 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 11 October 2017 | Review declared as stable | No new studies likely to change the conclusions are expected. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2003 Review first published: Issue 4, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 July 2017 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

| 15 September 2011 | Review declared as stable | The authors of this review ran a quick search for new studies in April 2011 and agreed that this review would not need updating for at least five years. |

| 28 October 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | This review was updated with new authorship and revised conclusions. |

| 28 October 2008 | New search has been performed | Updated review with revised search, more information and new outcomes. Five new studies adding a further 515 participants were included in this update (Binning 2007; Chan 2005; Hill 2006; Malmstrom 2004; Rasmussen 2005) as well as four new excluded studies (Bjornsson 2003; Demirel 2005; Frezza 1985; Yilmaz 2006. Fourteen studies previously included in the excluded studies were deleted. |

Notes

A restricted search in June 2017 did not identify any potentially relevant studies. Therefore, this review has now been stabilised following discussion with the authors and editors. If appropriate, we will update the review if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitate major revisions.

Acknowledgements

Lorna Mason and Jayne Rees (Jayne Edwards) were authors on the original review. We would like to thank Merck & Co Inc, Rahway, New Jersey, USA for providing unpublished data for inclusion in the original review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for MEDLINE via Ovid

naproxen [single term MESH]

naproxen

OR/1‐2

PAIN, POSTOPERATIVE [single term MeSH]

((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$")) [title, abstract or keywords]

((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$)) [title, abstract or keywords]

(("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after")) [title, abstract or keywords]

(("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)) [title, abstract or keywords]

((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")) [title, abstract or keywords]

((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")) [title, abstract or keywords]

OR/4‐10

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab.

trial.ab.

groups.ab.

OR/12‐19

humans.sh.

20 AND 21

3 AND 11 AND 22

For the earlier review the following brand names were also searched:

Acusprain, Aleve, Alganil, Aliviomas, Alpoxen, Alprofen, Anaprox, Antalgin, Aperdan, Apo‐Napro‐Na, Apranax, Arthrosin, Arthroxen, Artroxen, Axer, Clinosyn, Continus, Denaxpren, Diparene, Dysmenalgit, Femex, Floginax, Flogogin, Floxalin, Genoxen, Gibinap, Gibixen, Gynestral, Ilagane, Inza, Laraflex, Laser, Ledox, Leniatril, Lundiran, Madaprox, Miranax, Miranax, Nafasol, Naparatec, Napflam Napmel, Naprel, Napren, Naprex, Naprium, Naprius, Naprobene, Naprocoat, Naprodol, Napro‐Dorsch, Naprogesic, Naprokes, Naprorex, Naproscript, Naprosyn, Naprosyne, Naproval, Naprovite, Natrioxen, Naxen, Nitens, Novo‐Naprox, Numidan, Numide, Nu‐Naprox, Nycopren, Piproxen, Pranoxen, Praxenol, Prexan, Primeral, Pronaxen, Prosaid, Proxen, Proxine, Rheuflex, Rimoxyn, Rofanten, Sobronil, Synalgo, Synflex, Ticoflex, Timpron, Traumox, Valrox, Xenar, Xenopan.

Appendix 2. Search strategy for EMBASE via Ovid

naproxen [single term MESH]

naproxen

OR/1‐2

PAIN, POSTOPERATIVE [single term MeSH]

((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$"))

((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$))

(("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after"))

(("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort))

((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ surg$"))

((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ surg$"))

OR/4‐10

clinical trials.sh

controlled clinical trials.sh

randomized controlled trial.sh

double‐blind procedure.sh

(clin$ adj25 trial$)

((doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$))

placebo$

random$

OR/12‐19

3 AND 11 AND 20

Appendix 3. Search strategy for Cochrane CENTRAL

naproxen [single term MESH]

naproxen [title, abstract or keywords]

OR/1‐2

PAIN, POSTOPERATIVE [single term MeSH]

((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$")) [title, abstract or keywords]

((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$)) [title, abstract or keywords]

(("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after")) [title, abstract or keywords]

(("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)) [title, abstract or keywords]

((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")) [title, abstract or keywords]

((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")) [title, abstract or keywords]

OR/4‐10

clinical trials [exp MESH term]

controlled clinical trials [exp MESH term]

randomized controlled trial [exp MESH term]

double‐blind procedure [single term MESH]

(clin$ adj25 trial$) [title, abstract or keywords]

((doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)) [title, abstract or keywords]

placebo$ [title, abstract or keywords]

random$ [title, abstract or keywords]

OR/12‐19

3 AND 11 AND 20

Appendix 4. Glossary

Categorical rating scale:

The commonest is the five category scale (none, slight, moderate, good or lots, and complete). For analysis numbers are given to the verbal categories (for pain intensity, none = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2 and severe = 3, and for relief none = 0, slight = 1, moderate = 2, good or lots = 3 and complete = 4). Data from different subjects is then combined to produce means (rarely medians) and measures of dispersion (usually standard errors of means). The validity of converting categories into numerical scores was checked by comparison with concurrent visual analogue scale measurements. Good correlation was found, especially between pain relief scales using cross‐modality matching techniques. Results are usually reported as continuous data, mean or median pain relief or intensity. Few studies present results as discrete data, giving the number of participants who report a certain level of pain intensity or relief at any given assessment point. The main advantages of the categorical scales are that they are quick and simple. The small number of descriptors may force the scorer to choose a particular category when none describes the pain satisfactorily.

VAS:

Visual analogue scale: lines with left end labelled "no relief of pain" and right end labelled "complete relief of pain", seem to overcome this limitation. Patients mark the line at the point which corresponds to their pain. The scores are obtained by measuring the distance between the no relief end and the patient's mark, usually in millimetres. The main advantages of VAS are that they are simple and quick to score, avoid imprecise descriptive terms and provide many points from which to choose. More concentration and coordination are needed, which can be difficult post‐operatively or with neurological disorders.

TOTPAR:

Total pain relief (TOTPAR) is calculated as the sum of pain relief scores over a period of time. If a patient had complete pain relief immediately after taking an analgesic, and maintained that level of pain relief for six hours, they would have a six‐hour TOTPAR of the maximum of 24. Differences between pain relief values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the composite trapezoidal rule. The trapezoidal rule is a simple method that approximately calculates the definite integral of the area under the pain relief curve by calculating the sum of the areas of several trapezoids that together closely approximate to the area under the curve.

SPID:

Summed pain intensity difference (SPID) is calculated as the sum of the differences between the pain scores over a period of time. Differences between pain intensity values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the trapezoidal rule.

VAS TOTPAR and VAS SPID are visual analogue versions of TOTPAR and SPID.

See "Measuring pain" in Bandolier's Little Book of Pain, Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2003; pp 7‐13 (Moore 2003).

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Naproxen 200 mg or naproxen sodium 220 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | 2 | 202 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.87 [1.60, 5.15] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Naproxen 200 mg or naproxen sodium 220 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

Comparison 2. Naproxen 400 mg or naproxen sodium 440 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | 3 | 334 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.80 [2.75, 8.38] |

| 2 Participants with at least one adverse event | 2 | 257 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.78, 2.24] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Naproxen 400 mg or naproxen sodium 440 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Naproxen 400 mg or naproxen sodium 440 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Participants with at least one adverse event.

Comparison 3. Naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | 9 | 783 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.39 [2.64, 4.36] |

| 2 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, dental and other surgery | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Dental | 5 | 402 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.67 [5.22, 14.41] |

| 2.2 Other surgery | 4 | 382 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [1.31, 2.35] |

| 3 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, ≥40 participants per group | 5 | 513 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.67 [2.60, 5.19] |

| 4 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, <40 participants per group | 4 | 271 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.05 [2.13, 4.36] |

| 5 Participants with at least one adverse event | 7 | 581 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.74, 1.24] |

| 6 Participants using rescue medication within 12 hours | 5 | 480 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.74, 0.91] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, dental and other surgery.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, ≥40 participants per group.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo, Outcome 4 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, <40 participants per group.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo, Outcome 5 Participants with at least one adverse event.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Naproxen 500 mg or naproxen sodium 550 mg versus placebo, Outcome 6 Participants using rescue medication within 12 hours.

Comparison 4. Naproxen or naproxen sodium (all doses) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | 14 | 1345 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.21 [2.59, 3.96] |

| 2 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, dental and other surgery | 14 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Dental | 8 | 781 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.96 [5.34, 11.87] |

| 2.2 Other surgery | 6 | 647 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.89 [1.48, 2.42] |

| 3 Participants with at least one adverse event | 10 | 991 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.85, 1.33] |

| 4 Participants using rescue medication within 12 hours | 6 | 602 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.70, 0.85] |

| 5 Participants using rescue medication within 24 hours | 3 | 298 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.60, 0.76] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Naproxen or naproxen sodium (all doses) versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Naproxen or naproxen sodium (all doses) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, dental and other surgery.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Naproxen or naproxen sodium (all doses) versus placebo, Outcome 3 Participants with at least one adverse event.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Naproxen or naproxen sodium (all doses) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Participants using rescue medication within 12 hours.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Naproxen or naproxen sodium (all doses) versus placebo, Outcome 5 Participants using rescue medication within 24 hours.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Binning 2007.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single and multiple dose phases, 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45 mins, then 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 hours |

|

| Participants | Arthroscopic knee surgery Mean age 38 years N = 94 M = 66, F = 28 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen 500 mg, n = 34 Nimesulide 100 mg, n = 29 Placebo, n = 31 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: 100 mm VAS (and non‐std 5 point scale) PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants reporting serious adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1 Period before rescue medication permitted unspecified. Rescue medication: paracetamol 500 mg up to 6 x daily |

|

Brown 1997.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single and multiple dose phases, 5 parallel groups. Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30 mins, then hourly up to 12 hours |

|

| Participants | Major abdominal, gynaecological, thoracic or orthopaedic surgery Mean age 42 years N = 218 M = 71, F = 147 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 46 Bromfenac 25 mg, n = 44 Bromfenac 50 mg, n = 43 IM ketorolac 30 mg, n = 30 Placebo, n = 43 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: non‐std 5 point scale Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants reporting any and serious adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1 Rescue medication permitted after 1 hour. Rescue medication: an opioid |

|

Chan 2005.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single and multiple dose phases. 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30 45, 60, 90, 120 mins, then hourly up to 12 hours |

|

| Participants | Total knee or hip arthroplasty Mean age 65 years N = 180 M = 91, F = 89 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen 500 mg, n = 60 Lumiracoxib 400 mg, n = 60 Placebo, n = 60 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: non std 4 point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants with any, and serious, adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Rescue medication permitted after 1 hour. Rescue medication: iv PCA morphine sulphate (1‐2 mg dose, 5‐10 min lockout) |

|

Forbes 1986.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single oral dose. 5 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at baseline and at hourly intervals up to 12 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical extraction of ≥1 impacted third molar Mean age 21 years N = 198 M = 79, F = 119 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 38 Codeine sulphate 60 mg, n = 44 Naproxen sodium plus codeine 550/60 mg, n = 38 Aspirin 650 mg, n = 36 Placebo, n = 42 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants with any and serious adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Rescue medication permitted after 2 hours |

|

Fricke 1993.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single dose, 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 20, 30, 40 and 60 mins, then hourly up to 12 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical extraction of 3 or 4 impacted third molars Mean age 23 years N = 201 M = 77, F = 124 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen sodium 440 mg, n = 81 Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 81 Placebo, n = 39 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants with any and serious adverse events Number of participants withdrawing due to adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1 Rescue medication permitted after 2 hours. Rescue medication: investigator's choice |

|

Gottesdiener 1999.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single dose, 5 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120 mins then hourly up to 12 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical extraction of ≥2 third molars, one of which was impacted Mean age 26 years N =196 M = 187, F = 9 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 25 DFP 5 mg, n = 48 DFP 25 mg , n = 50 DFP 50 mg, n = 48 Placebo, n = 25 (DFP is an experimental COX‐2 NSAID) |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants with any and serious adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Rescue medication permitted after 1.5 hours. Rescue medication: hydrocodone bitartrate + paracetamol | |

Hill 2006.

| Methods | RCT, DB, 6 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical extraction of impacted third molar Mean age 25 years N = 242 M = 116, F = 126 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen 500 mg, n = 39 AZD3852 375 mg, n = 41 AZD3852 750 mg, n = 37 AZD3852 1500 mg, n = 42 AZD3852 2250 mg, n = 41 Placebo, n = 42 (AZD3852 is an experimental cox‐inhibiting nitric oxide donor drug) |

|

| Outcomes | PI: 100 mm VAS PR: 100 mm VAS Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants with any, and serious, adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Period before rescue medication permitted unspecified. Rescue medication: ibuprofen 400 mg |

|

Kiersch 1993.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single dose, 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 20, 30, 40 and 60 min, then hourly up to 12 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical removal of ≥1 impacted third molar Mean age 25 years N = 203 M = 90, F = 113 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen sodium 220 mg, n = 80 Ibuprofen 200 mg, n = 81 Placebo, n = 42 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants with any and serious adverse events Number of participants withdrawing due adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1 Rescue medication permitted after 2 hours. Rescue medication: investigator's choice |

|

Kiersch 1994.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single dose, 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 20, 30, 40 and 60 mins, then hourly up to 12 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical extraction of 3 or 4 third molars Mean age 24 years N = 226 M = 102, F = 124 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen sodium 440 mg, n = 92 Acetaminophen 1000 mg, n = 89 Placebo, n = 45 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants with any and serious adverse events Number of participants withdrawing due to adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1 Rescue medication permitted after 2 hours. Rescue medication: investigator's choice |

|

Mahler 1976.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single dose, 5 parallel groups in 2 trials at 2 hospitals Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at baseline and hourly up to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Orthopaedic or general surgery Mean age 36 years N = 197 M and F (numbers not given) |

|

| Interventions | Data combined for hospital 1 & 2: Naproxen 200 mg, n = 40 Naproxen 400 mg, n = 37 Aspirin 600 mg, n = 39 Aspirin 1200 mg, n = 41 Placebo, n = 40 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W0 Rescue medication permitted after 2 hours. Rescue medication: second dose of study drug, except naproxen 400 mg group remedicated with placebo |

|

Malmstrom 2004.

| Methods | RCT, BD, single dose, 4 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120 mins, then hourly to 8 hours, then at 10, 12, 20 and 24 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical extraction of ≥2 third molars, with 1 impacted Mean age 201 N = 201 M = 97, F = 104 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 50 Etoricoxib 120 mg, n = 50 Paracetamol plus codeine 600/60 mg, n = 50 Placebo, n = 50 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants with any and serious adverse events Number of participants withdrawing due to adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Rescue medication permitted after 1.5 hours. Rescue medication: paracetamol/hydrocodone 500/550 mg |

|

Merck 1997a.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single dose, 6 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed up to 24 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical extraction of ≥2 third molars Age not given N = 228 M and F (numbers not given) |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 39 MK‐0966 7.5 mg, n = 38 MK‐0966 25 mg, n = 38 MK‐0966 50 mg, n =38 MK‐0966 100 mg, n = 38 Placebo, n = 38 (MK‐0966 is rofecoxib) |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point PR scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants with any adverse event |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, BD2, W0 No details of rescue medication Currently unpublished |

|

Merck 1997b.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single dose, 5 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed up to 24 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical extraction of ≥2 third molars Age not given N = 312 M and F (numbers not given) |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 49

MK‐0966 12.5 mg, n = 72 MK‐0966 25 mg, n = 72 MK‐0966 50 mg, n = 72 Placebo, n = 47 (MK‐0966 is rofecoxib) |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants with any adverse event |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, BD2, W0 No details of rescue medication Currently unpublished |

|

Rasmussen 2005.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single and multiple dose phases, 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120 mins, then hourly to 8 hours, then at 10, 12, 20 and 24 hours |

|

| Participants | Total knee or hip replacement Mean age 65 years N = 228 M = 90, F = 138 |

|

| Interventions | Naproxen sodium CR 1100 mg, n = 73 Etoricoxib 120 mg, n = 80 Placebo, n = 75 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4 point scale PR: std 5 point scale PGE: std 5 point scale Tiem to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants with any and severe adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Period before rescue medication permitted unspecified. Rescue medication: hydrocodone/paracetamol |

|

Reicin 2001.

| Methods | RCT, DB, single dose, 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 hours then hourly to 12 hours |

|