Abstract

Background

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder affecting primarily the skin of the scalp, face, chest, and intertriginous areas, causing scaling and redness of the skin. Current treatment options include antifungal, anti‐inflammatory, and keratolytic agents, as well as phototherapy.

Objectives

To assess the effects of topical pharmacological interventions with established anti‐inflammatory action for seborrhoeic dermatitis occurring in adolescents and adults.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to September 2013: the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register, CENTRAL in The Cochrane Library (2013, Issue 9), MEDLINE (from 1946), Embase (from 1974), LILACS (from 1982), and the GREAT database. We searched five trials databases and checked the reference lists of included studies for further references to relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Selection criteria

We included RCTs in adults or adolescents (> 16 years) with diagnosed seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp or face, comparing topical anti‐inflammatory treatments (steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and lithium salts) with other treatments.

Data collection and analysis

Pairs of authors independently assessed eligibility for inclusion, extracted data, and evaluated the risk of bias. We performed meta‐analyses if feasible.

Main results

We included 36 RCTs (2706 participants), of which 31 examined topical steroids; seven, calcineurin inhibitors; and three, lithium salts. The comparative interventions included placebo, azoles, calcipotriol, a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory compound, and zinc, as well as different anti‐inflammatory treatments compared against each other. Our outcomes of interest were total clearance of symptoms, erythema, scaling or pruritus scores, and adverse effects. The risk of bias in studies was most frequently classified as unclear, due to unclear reporting of methods.

Steroid treatment resulted in total clearance more often than placebo in short‐term trials (four weeks or less) (relative risk (RR) 3.76, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22 to 11.56, three RCTs, 313 participants) and in one long‐term trial (lasting 12 weeks). Steroids were also more effective in reducing erythema, scaling, and pruritus. Adverse effects were similar in both groups.

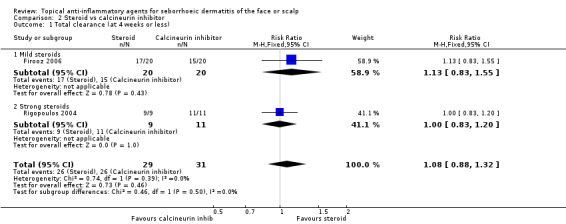

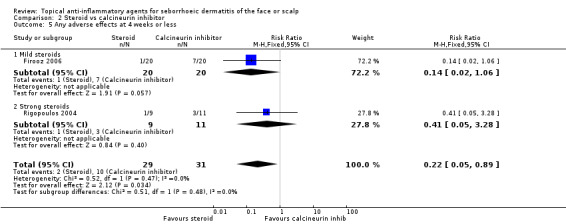

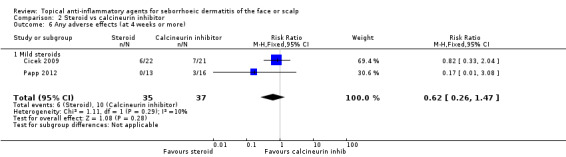

There may be no difference between steroids and calcineurin inhibitors in total clearance in the short‐term (RR 1.08, 95% 0.88 to 1.32, two RCTs, 60 participants, low‐quality evidence). Steroids and calcineurin inhibitors were found comparable in all other assessed efficacy outcomes as well (five RCTs, 237 participants). Adverse events were less common in the steroid group compared with the calcineurin group in the short‐term (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.89, two RCTs, 60 participants).

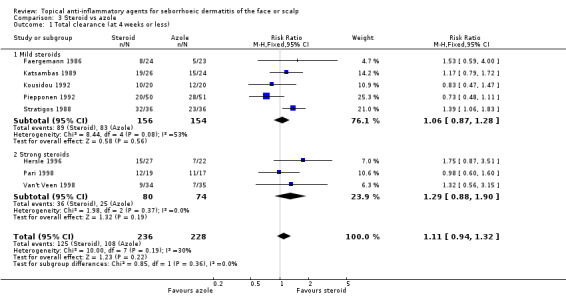

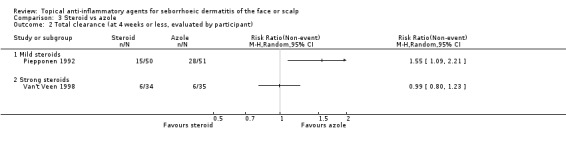

There were comparable rates of total clearance in the steroid and azole groups (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.32, eight RCTs, 464 participants, moderate‐quality evidence) as well as of adverse effects in the short‐term, but less erythema or scaling with steroids.

We found mild (class I and II) and strong (class III and IV) steroids comparable in the assessed outcomes, including adverse events. The only exception was total clearance in long‐term use, which occurred more often with a mild steroid (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.98, one RCT, 117 participants, low‐quality evidence).

In one study, calcineurin inhibitor was more effective than placebo in reducing erythema and scaling, but there were similar rates in total clearance or adverse events for short‐term treatment. In another study, calcineurin inhibitor was comparable with azole when erythema, scaling, or adverse effects were measured for longer‐term treatment.

Lithium was more effective than placebo with regard to total clearance (RR 8.59, 95% CI 2.08 to 35.52, one RCT, 129 participants) with a comparable safety profile. Compared with azole, lithium resulted in total clearance more often (RR 1.79, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.90 in short‐term treatment, one RCT, 288 participants, low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Topical steroids are an effective treatment for seborrhoeic dermatitis of the face and scalp in adolescents and adults, with no differences between mild and strong steroids in the short‐term. There is some evidence of the benefit of topical calcineurin inhibitor or lithium salt treatment. Treatment with azoles seems as effective as steroids concerning short‐term total clearance, but in other outcomes, strong steroids were more effective. Calcineurin inhibitor and azole treatment appeared comparable. Lithium salts were more effective than azoles in producing total clearance.

Steroids are similarly effective to calcineurin inhibitors but with less adverse effects.

Most of the included studies were small and short, lasting four weeks or less. Future trials should be appropriately blinded; include more than 200 to 300 participants; and compare steroids to calcineurin inhibitors or lithium salts, and calcineurin inhibitors to azoles or lithium salts. The follow‐up time should be at least one year, and quality of life should be addressed. There is also a need for the development of well‐validated outcome measures.

Plain language summary

Topical anti‐inflammatory agents for seborrhoeic dermatitis of the face or scalp

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is an inflammation of the skin that most often affects areas of the body that have a lot of sebaceous glands. These include the skin of the scalp; face; chest; and flexure areas such as the armpits, groin, and abdominal folds. The most typical symptoms of seborrhoeic dermatitis are scaling of the skin and reddish patches. Seborrhoeic dermatitis is fairly common: one to three in 100 people have seborrhoeic dermatitis. The disease is more common in men than in women. Anti‐inflammatory, antifungal, and antikeratolytic treatments can be used to treat seborrhoeic dermatitis. The treatment does not cure the disease but relieves the symptoms.

We included 36 randomised controlled trials with 2706 participants, examining the effect of anti‐inflammatory treatments on seborrhoeic dermatitis. These trials were short‐term; most of them lasting four weeks or less.

Topical steroid treatment (such as hydrocortisone and betamethasone), topical calcineurin inhibitor treatment (such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus), and topical lithium salts all reduced the symptoms of seborrhoeic dermatitis when compared with placebo treatment. Mild (such as hydrocortisone 1%) and strong (such as betamethasone) steroid compounds were comparable in short‐term follow up. Short‐term total clearance was achieved with antifungal azole treatment (such as ketoconazole and miconazole), as well as with steroids. Strong steroids were better than azole treatment in reducing erythema, scaling, and pruritus, and were comparable in terms of safety. Steroids were also as effective as calcineurin inhibitors, but side‐effects occurred more often with calcineurin inhibitors. We found no differences between calcineurin inhibitors and azole treatments in effectiveness or side‐effects. Lithium was more effective than azoles but had a similar frequency of side‐effects (one study).

The most common side‐effects were burning, itching, erythema, and dryness in all treatment groups.

Topical anti‐inflammatory agents are useful in treating seborrhoeic dermatitis. Steroids are the most investigated anti‐inflammatories. We still do not know the effects and safety of topical anti‐inflammatory treatments in long‐term or continuous use. This is regrettable as the disease is chronic in nature. Furthermore, there are no data concerning the effects of different treatments on quality of life.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Calcineurin inhibitor compared with steroid for seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp or face.

| Steroid compared with calcineurin inhibitor for seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp or face | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with seborrhoeic dermatitis Settings: community setting implied from context but not stated Intervention: steroid Comparison: calcineurin inhibitor | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Calcineurin inhibitor | Steroid | |||||

| Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less) Investigator's assessment Follow up: ≦ 2 weeks | 839 per 1000 | 906 per 1000 (738 to 1000) | RR 1.08 (0.88 to 1.32) | 60 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low¹,² | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the risk in the control groups of the relevant trials. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Participants were not blinded. ²Small number of participants in studies.

Summary of findings 2. Steroid compared with azole for seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp or face.

| Steroid compared with azole for seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp or face | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp or face Settings: community setting implied from context but not stated Intervention: steroid Comparison: azole | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Azole | Steroid | |||||

| Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less) Investigator's assessment Follow up: 3 to 4 weeks | 474 per 1000 | 526 per 1000 (445 to 625) | RR 1.11 (0.94 to 1.32) | 464 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate¹ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Risk of bias considerable in all studies.

Summary of findings 3. Strong steroid (class III or IV) compared with mild steroid (class I or II) for seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp or face.

| Strong steroid (class III or IV) compared with mild steroid (class I or II) for seborrhoeic dermatitis | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with seborrhoeic dermatitis Settings: community setting implied from context but not stated Intervention: strong steroid (class III or IV) Comparison: mild steroid (class I or II) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Mild steroid (class I or II) | Strong steroid (class III or IV) | |||||

| Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less) Investigator's assessment Follow up: 3 to 4 weeks | 413 per 1000 | 397 per 1000 (268 to 578) | RR 0.96 (0.65 to 1.4) | 93 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate¹ | ‐ |

| Total clearance (more than 4 weeks) Investigator's assessment Follow up: 6 weeks | 644 per 1000 | 509 per 1000 (406 to 631) | RR 0.79 (0.63 to 0.98) | 117 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low² | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Imprecision (two small studies). ²One study that was not blinded (patient and care provider not blinded; blinding of outcome assessment not reported).

Summary of findings 4. Lithium compared with azole for seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp or face.

| Lithium compared with azole for seborrhoeic dermatitis | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with seborrhoeic dermatitis Settings: community setting Intervention: lithium Comparison: azole | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Azole | Lithium | |||||

| Total clearance Investigator's assessment Follow up: 4 weeks | 147 per 1000 | 263 per 1000 (162 to 426) | RR 1.79 (1.1 to 2.9) | 288 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low¹ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹One study in which participants were not blinded and blinding of others was not reported.

Background

Seborrhoeic dermatitis or eczema is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder primarily affecting areas rich in sebaceous glands (Kim 2010). Such areas include, for example, skin of the scalp, face, chest, and intertriginous areas (areas where folds of skin are touching each other, such as the armpits, groin, and abdominal folds). These areas are liable to irritation from sweating and infection (Naldi 2009). Typical symptoms of the disease are scaling of the skin and erythematous (reddish) patches (Schwartz 2006).

Description of the condition

The specific cause of seborrhoeic dermatitis (SeD) is not known in detail. Despite its name and affected areas, this disease is not always associated with excessive sebum secretion (Burton 1983). It has been suggested that many endogenous and exogenous factors are associated with the course and severity of this disorder. These include hormonal factors; comorbidities (associated diseases); individual immunological features; and nutritional, environmental, and lifestyle factors (Gupta 2004; Schwartz 2006), but the mechanism of action of each of these factors has not been determined. A causative role has been suggested for Malassezia yeasts because SeD responds to antifungal treatments when a concurrent decrease of the number of the yeasts on the skin is seen (Gupta 2004). However, the overall evidence is still somewhat unclear.

The diagnosis of this disease is largely clinical and based on affected areas and the type of rash. Ill‐defined erythematous patches with fine scaling on the sides of the nose, eyebrows, and scalp are seen most often in adult patients. Pruritus (itch) is often present in an affected scalp (Del Rosso 2011). In dark‐skinned people, SeD can present as postinflammatory changes, such as hypopigmentation (Halder 2003). A skin biopsy is rarely needed for diagnosis, but it can be useful for excluding other less common conditions, such as lupus (Naldi 2009; Schwartz 2006). Dandruff is a commonly used term for any scalp condition that produces fine scales, but it has also been used in the context of mild SeD (Naldi 2009; Schwartz 2006). The disease has a chronic nature with occasional relapses. The severity of SeD varies from mild flaking to severe oily scaling. The distribution of lesions is generally symmetrical (Gupta 2004). Although the disease affects the skin of the scalp, it does not normally cause baldness.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a fairly common skin disorder. The prevalence is not known precisely as there are no validated criteria for diagnosis of the condition (Naldi 2009). An infantile form (cradle cap) has been reported to affect as many as 70% of newborns during the first three months of life, but this quickly resolves (Foley 2003). So, the overall prevalence of seborrhoeic dermatitis is 10% in children five years of age or younger (Foley 2003). In the adult population, prevalence is between 1% to 3%, and occurrence is more common in adolescents and young adults than those in middle age (Gupta 2004). The incidence increases again in people over 50 years of age (Gupta 2004). Seborrhoeic dermatitis affects men more frequently than women, and some diseases, such as Parkinson's disease and HIV (human immunodeficiency virus)/AIDS, are known to increase the risk of the disease (Naldi 2009).

Description of the intervention

The standard treatments for seborrhoeic dermatitis include topical anti‐inflammatory (immunomodulatory) agents, such as corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors, to reduce inflammation; topical antifungals, such as azoles, ciclopirox olamine, and zinc pyrithione, to reduce Malassezia; and topical keratolytic agents, such as salicylic acid, tar, selenium sulphide, and zinc pyrithione, to soften and remove thick hardened crusts. Many agents have multiple mechanisms of action, and in some, the exact mechanism is not known (Gupta 2004; Naldi 2009; Schwartz 2006).

How the intervention might work

Topical corticosteroids (e.g. hydrocortisone, betamethasone, clobetasol, and desonide) have traditionally been used in the treatment of SeD. They reduce inflammation and relieve erythema and itching. Calcineurin inhibitors (e.g. pimecrolimus and tacrolimus) have also been used for their anti‐inflammatory effects. It has been suggested that lithium salts, lithium succinate (often in combination with zinc sulphate), and lithium gluconate have anti‐inflammatory effects, but they may also have antifungal properties (Gupta 2004; Naldi 2009; Schwartz 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a fairly common skin disorder that affects a considerable number of children and adults. There are many available treatment options, but it is unclear which should be preferred. It is important to evaluate the efficacy of these options in order to improve the outcome of the therapy. This review is one of two Cochrane systematic reviews on this topic and will focus on treatment options with an established anti‐inflammatory mechanism. The other Cochrane review is focused on drugs with an antifungal mechanism (Okokon 2011).

Objectives

To assess the effects of topical pharmacological interventions with established anti‐inflammatory action for seborrhoeic dermatitis occurring in adolescents and adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials and cross‐over randomised controlled trials (including within‐patient studies).

We excluded cluster randomised trials.

Types of participants

We included studies of adults or adolescents (> 16 years) with diagnosed seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp or face. At least 75% of the study participants had to be over 10 years of age to fulfil the age criterion.

We excluded studies of people having other skin diseases or seborrhoeic dermatitis occurring solely in areas other than the scalp or face.

Types of interventions

We included the following topically administered drugs with an established anti‐inflammatory mechanism of action: corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. We also included lithium salts in the review as it has been suggested that their effect is based on anti‐inflammatory properties.

We excluded studies in which the anti‐inflammatory intervention had been combined with a non‐anti‐inflammatory agent in preparation. We examined all clinically relevant comparisons between treatments.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Percentage of treated persons with total resolution of symptoms as evaluated by the outcome assessor (total clearance).

Disease severity scores for scaling, pruritus, or erythema at the end of treatment as evaluated by participant self‐report, outcome assessor, or both.

Percentage of persons treated who develop side‐effects or intolerance to treatment.

Secondary outcomes

Improvement in quality of life.

Timing of outcomes

We defined the timing of outcomes using the following categories:

When the treatment period lasted for four weeks or less, we defined these outcomes as short‐term effects.

When the treatment period lasted for more than four weeks, we defined these outcomes as long‐term effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases up to 18 September 2013:

the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register using the following terms: "seborrh* dermatitis" or "scalp dermatos*" or "scalp dermatitis" or "scalp eczema" or "cradle cap" or dandruff or malassezia or "seborrh* eczema";

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library using the search strategy in Appendix 1;

MEDLINE via OVID (from 1946) using the strategy in Appendix 2;

Embase via OVID (from 1974) using the strategy in Appendix 3;

the Global Resource of EczemA Trials (GREAT, Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology, accessed at http://www.greatdatabase.org.uk on 18 September 2013) using the same search terms as for the Skin Group Specialised Register above; and

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database, from 1982) using the strategy in Appendix 4.

Trials databases

We searched the following trials registers on 22 October 2013, using the following search terms: seborrheic dermatitis or seborrhoeic or dandruff or cradle cap or malassezia or scalp dermatoses.

The metaRegister of Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com).

The US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

The Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au).

The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry platform (www.who.int/trialsearch).

The EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu).

Searching other resources

References from included studies

We checked the bibliographies of included studies for further references to relevant trials.

Adverse effects

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of the target interventions. We examined data on adverse effects from the included studies we identified.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three authors (TOk, HK, and JJ) independently identified relevant articles retrieved from the literature searches by assessing their titles and abstracts. Where we had differing views, we retained the article for full‐text assessment.

The same three authors and one additional author (TOr) independently assessed the full‐text papers using study eligibility forms in order to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria. Where there were differing views that could not be resolved between the review authors, a third author (PP) made the decision of inclusion or exclusion.

Data extraction and management

The same authors (TOk, HK, and JJ) carried out data extraction independently using data extraction forms. A third researcher (PP) resolved discrepancies if consensus could not be found between the primary authors. TOk and HK managed the data including entering it into Review Manager (RevMan). HK checked the entered data for accuracy. We requested any further information needed from the original authors by email and included any relevant information obtained in this manner in the review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The assessment of the risk of bias included an evaluation of the following components for each included study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011):

(a) selection bias ‐ we considered whether the methods of randomisation were adequate and whether the treatment allocation was concealed in the included studies. As there was some overlap between the clinical spectrum of seborrhoeic eczema and dandruff, we paid attention to the presence of the diagnosis of seborrhoeic dermatitis in participants and to the baseline severity of the disease in study groups; (b) performance bias ‐ we assessed whether the participants and the caregivers were blinded to the interventions and whether cointerventions and other treatments were similar in study groups; (c) detection bias ‐ we evaluated whether the outcome assessors were blinded to the interventions; (d) attrition bias ‐ we assessed whether the trial described dropout rates and whether they were acceptable, whether compliance was acceptable in all groups, and whether the study reports used intention‐to‐treat analysis (we used the number of randomised participants in our analyses, where available); (e) reporting bias ‐ we evaluated whether there were signs of selective reporting in the studies; and (f) other bias ‐ we evaluated whether there might have been other sources of bias, for example, relating to particular study designs.

We assessed the study quality without blinding to authorship or journal.

We have summarised the information in the 'Risk of bias' table for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we expressed the combined estimate of effects as risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (Cl). For the main outcome (total clearance), we expressed summary estimates also as number needed to treat (NNT) for statistically significant findings, with a 95% CI and the baseline risk to which it applies.

For continuous outcomes, we used the mean difference with a 95% CI for summarising results. Where similar outcomes were measured differently across studies but measured the same concept, we used the standardised mean difference and a 95% confidence interval.

Unit of analysis issues

When there was intrapatient correlation in studies that had randomised body parts of the same participant and the study authors had not adjusted for this clustering effect, we did this adjustment according to the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

We analysed studies with multiple treatment groups using pair‐wise comparisons. We avoided counting the control group of multiple treatment studies twice, by dividing the number of control participants over the number of comparisons in the same meta‐analysis, excluding the outcome of any adverse effects.

Dealing with missing data

We applied the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle by considering dropouts as non‐responders (conservative approach). If data necessary for meta‐analysis (such as standard deviations) were missing in the trial reports, we asked study authors for additional information. If they could not be reached, we calculated the necessary data from other statistics, if such information was available, or approximated them from information (e.g. graphics) given in the reports.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by examining types of participants, interventions, and outcomes in each study. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic. We interpreted heterogeneity in effect estimates as considerable when the I² statistic was greater than 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias as within‐study reporting bias (selective outcome reporting) and as publication bias. We did not perform funnel plot analyses as the number of studies was small in our meta‐analyses. To avoid language bias, we imposed no language restrictions.

Data synthesis

For studies judged to be clinically and statistically homogenous with an I² statistic < 50%, we pooled the measures of treatment effect using their weighted average for the treatment effect (using a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis method, as implemented in Review Manager). For studies deemed to be heterogeneous (I² statistic ≥ 50%), we performed a random‐effects meta‐analysis. For studies with I² statistics more than 80%, we did not perform a meta‐analysis, but described the results individually.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to explore heterogeneity by examining age (less than 65 or over 65 years), gender (male or female), and dose (frequency) distributions of the studies. We aimed to conduct subgroup analyses if significant heterogeneity between the studies for the primary outcomes in a comparison appeared. The number of studies was small in most comparisons; therefore, performing subgroup analyses was not reasonable with the exception of comparison between mild and strong steroids.

Sensitivity analysis

We aimed to but did not perform sensitivity analyses to examine the effects of risk of bias as there were few studies in each comparison. Furthermore, the overall risk of bias was at least moderate in most studies.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

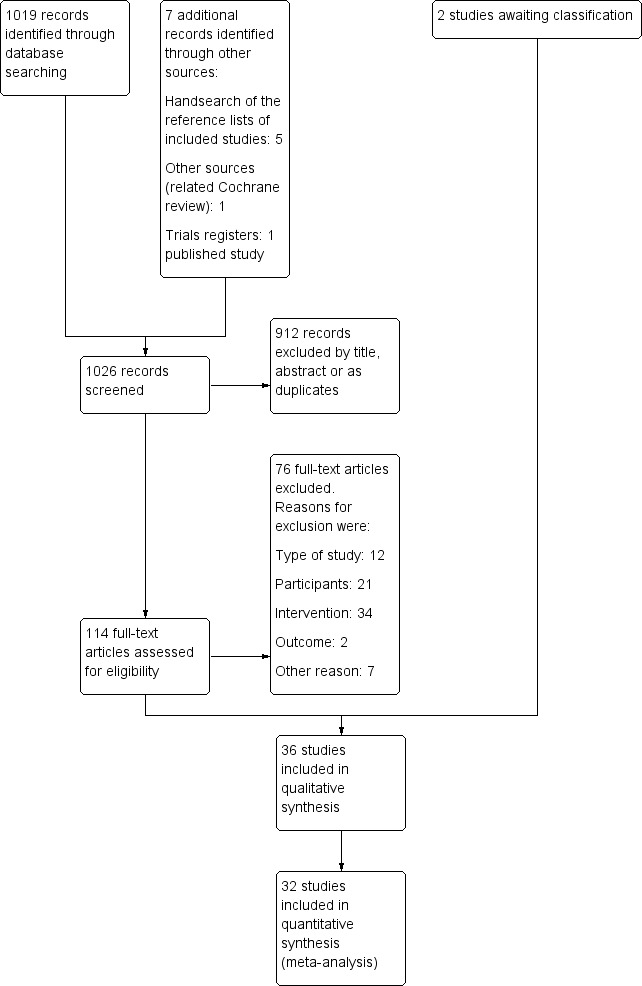

The database searches yielded 1019 records. We identified a further seven records:

five from handsearching the references of our included studies;

one from a related Cochrane review (Okokon 2011); and

one published study from a trials register (Ortonne 2011).

We screened 1026 records, of which we excluded 912 based on the title and abstract or because they were duplicates.

We screened 114 full‐text articles. We excluded 76 records (see the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables).

Altogether, we included 36 studies (see the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables). We assigned two studies to the Studies awaiting classification section on the grounds that it was unclear whether they measured the outcomes of interest.

We present our screening process in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Study design

All 36 included studies, with 2706 participants, were reported as randomised controlled trials, with three comparing body parts.

Year of study

The 36 included studies were carried out between 1970 and 2012 with 13 studies before the year 1990, 10 studies between 1990 and 2000, and 13 studies after the year 2000.

Participants

In seven studies, a physician explicitly diagnosed participants with seborrhoeic dermatitis (SeD), and in 29 studies, this was unclear (implied from context but not clearly stated). The definition of SeD was given in one study only (Cicek 2009). The studied area was the scalp only in 16 reports; the face only in 10 reports; the face and scalp in one report; and the face, scalp, or both with other areas in seven reports. Two studies did not specify the affected and investigated areas, but it could be concluded that they included facial or scalp involvement based on the assessed body areas.

Six studies included participants under 18 years of age (from ages 12, 14, or 15 upwards). Four reports did not state the age of the participants. In three studies, there was an upper limit of age (65 years in two and 55 years in one study). All studies but one included both men and women (Langtry 1997 included only homosexual men with HIV). Frequent exclusion criteria were pregnancy, lactation state, other dermatoses or interventions, too severe or mild disease, or HIV. The older studies often did not report the exclusion criteria.

The number of participants in individual studies varied between 12 and 303, resulting in a median of 64.

Geography

The geographical variation of studies was as follows: USA (10 studies), France (four studies), Greece (four studies), Sweden (four studies), Turkey (three studies), Finland (two studies), UK (two studies), Iran (one study), Denmark (one study), Korea (one study), India (one study), Canada (one study), and Netherlands (one study). One study was multicentre (Belgium, France, Germany, Mexico, and South Korea).

Interventions

The included studies used the following drugs (doses and mode of delivery) for seborrhoeic dermatitis.

Mild steroids (class I or class II, classification according to the ATC (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical) classification by the World Health Organization (WHO))

hydrocortisone (cream 1%, liniment 1%, lotion 0.1%, ointment 1.0%, and solution 1%)

alclometasone (ointment 0.05%)

desonide (cream 0.05%)

Strong steroids (class III or class IV, classification according to ATC classification by the WHO)

methylprednisolone (cream 1%)

betamethasone (lotion 0.1%, lotion 0.05%, cream 0.1%, and solution 1 mg/ml)

clobetasol (shampoo 0.05% and cream 0.05%)

amcinonide (lotion 0.1%)

mometasone (solution 0.1% or cream 0.1%)

fluocinolone acetonide (solution 0.01%, shampoo 0.01%)

Calcineurin inhibitors

pimecrolimus (cream 1%)

tacrolimus (ointment 0.1%)

Azoles

ketoconazole (cream 2%, foaming gel 2%, shampoo 2%, shampoo 1%, and hydrogel 20 mg/g)

metronidazole (gel 0.75%)

miconazole (base 2%)

Lithium (gluconate ointment 8% and succinate ointment 8%)

Zinc pyrithione (shampoo 1%)

Calcipotriol (solution 50 μg/ml)

Promiseb® (cream)

Placebo or propylene glycol

We decided to pool together all steroid studies as there were so many different steroidal compounds studied and often only one study on one compound. We also decided to pool together all calcineurin inhibitors and all azoles as the number of studies was limited. This enabled us to make the following direct comparisons.

Steroids compared with placebo (six trials)

Steroids compared with calcineurin inhibitors (five trials)

Steroids compared with azoles (12 trials)

Steroids compared with other compounds (calcipotriol, zinc pyrithione, Promiseb®) (three trials)

Mild steroids compared with strong steroids (five trials)

Calcineurin inhibitors compared with placebo (one trial)

Calcineurin inhibitors compared with azoles (two trials)

Calcineurin inhibitors compared with other compounds (zinc pyrithione) (one trial)

Lithium salts compared with placebo (two trials)

Lithium salts compared with azoles (one trial)

We also identified two studies comparing a mild steroid with another mild steroid (Cornell 1986; Cornell 1993) and one study comparing a strong steroid with another strong steroid (Cornell 1989). We do not display the results for these comparisons, however, as the focus of this review is to compare anti‐inflammatory treatments with placebo and comparisons between different anti‐inflammatory treatment classes.

We contacted three authors for additional data, which we received from two.

Outcomes

Twenty‐three of the 36 included studies used total clearance as a measure of outcome. Resolution of symptoms was measured either on scale or as resolution of that specific symptom as follows: scaling in 19 studies, erythema in 17 studies, pruritus in 15 studies. The validation of the scales used was not reported in any of the articles. In four studies, adverse events were the only outcome we could use in this review (Cicek 2009; Ortonne 1992; Ortonne 2011). Seven studies (19%) did not report the side‐effects.

Excluded studies

We excluded 76 studies. The most frequent reason for exclusion was that the intervention in the study was not anti‐inflammatory or it was a combination of two drugs. Another common reason for excluding a study was that the proportion of people with SeD was unclear or that the proportion of them was too small. We identified two studies that did not report outcomes relevant for this review or did not report them in numerical form. We excluded them as they had no useful data to add to the analyses (Kim 2012; Marks 1974).

We present detailed reasons for exclusions in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Studies awaiting classification and ongoing studies

We assigned two studies to the Studies awaiting classification section as we had no evidence that they measured the outcomes of interest. We will reconsider these studies in the next update of the review. See the 'Characteristics of studies awaiting classification' tables for details. We identified seven studies from trials registers that are either ongoing or not yet published. See the 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' tables for details.

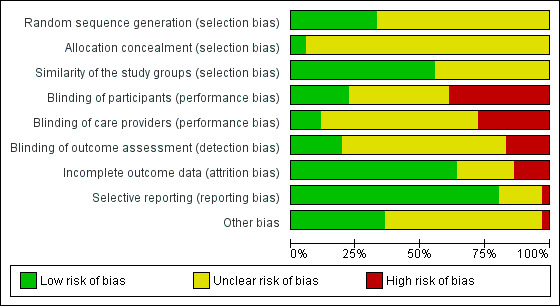

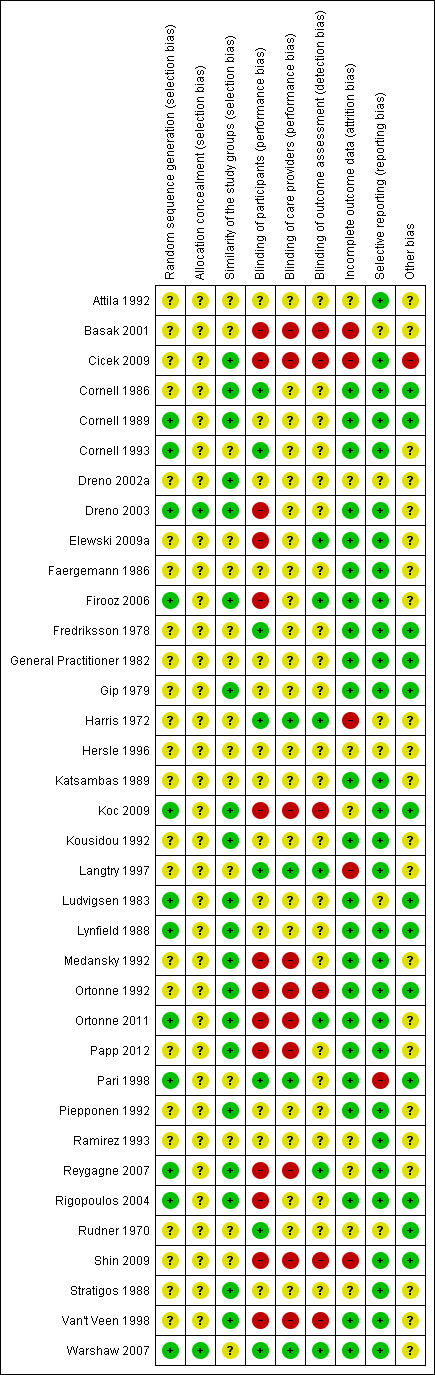

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias in the included studies as described above (Assessment of risk of bias in included studies). The most frequent classification of risk of bias in studies was unclear. This was especially because of unclear reporting of methods, such as reporting studies to be double‐blind without specifying who was blinded. Figure 2 displays the overall percentages of risk of bias for the studies included in the review. Figure 3 displays the risk of bias judged for each included study.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study

Allocation

Most reports classified selection bias as unclear. They often stated that participants were randomly allocated but did not report the methods of randomisation or allocation sequence concealment in detail. Twelve studies reported the generation of the randomisation sequence, and most commonly, it was computer‐based. Only two studies described the allocation concealment method; otherwise, the studies did not mention it at all, and therefore we classified them as unclear risk.

Blinding

Most often the studies were reported to be double‐blind, but it was not clear which two of the three parties (the participants, the caregivers, or the outcome assessors) were blinded. In these cases, we evaluated the risk of bias as unclear. Seven reports stated that the whole study was outcome assessor blinded. Six of the included studies were completely open‐label or did not mention blinding, which we rated as at high risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We evaluated attrition bias to be low in 23 of the studies. The reason we classified a study with a high risk for attrition bias was most often because of a considerable dropout rate (over 20%). We evaluated attrition bias to be unclear in eight studies when it was unclear whether the results given in percentages were calculated using the randomised or the completed participant numbers.

Selective reporting

We classified the risk for reporting bias as low in 29 of the studies. One study did not prespecify the outcomes in the report, but the outcomes reported were those commonly used in SeD studies. In seven studies, there was no mention of side‐effects at all, which we consider a serious omission. However, we did not assess the lack of information concerning side‐effects as a reporting bias unless the measurement of adverse effects was part of the predefined outcome measures, but had not been reported.

Other potential sources of bias

We sought other potential sources of bias. One study (Cicek 2009) evaluated both the efficacy outcome and side‐effects using the same symptoms (erythema and pruritus were both an efficacy outcome and a side‐effect); therefore, it was impossible for a reader to evaluate when or why these symptoms were classified as an outcome or a side‐effect. Therefore, we classified the risk of bias as high for this trial. One study (Koc 2009) did not report the affected area (although we could conclude from the report that facial involvement was an inclusion criterion); therefore, we were not sure that the efficacy or the intervention on facial or scalp SeD was the same as reported in the article. We judged the risk of bias as low regarding this study. One study (Langtry 1997) only included male HIV participants, which may limit the ability to generalise the results into other populations. (We judged risk of bias as unclear.)

The most common circumstance in studies classified as having unclear risk was author affiliation to the pharmaceutical industry or interventions sponsored or provided by the pharmaceutical industry (N = 21 for studies having some kind of affiliations to the pharmaceutical industry). This classification was done categorically, and it does not imply that in the opinion of the review authors, these studies have increased risk of bias. In 13 studies, we were unable to identify other potential sources of bias, so we classed these at low risk of bias.

Similarity of study groups (selection bias)

Most of the included studies described adequately the similarity of study groups, and the risk of bias was low in 20 studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

We have addressed the comparisons under the following headings.

Steroids versus comparators

Steroids versus placebo

Steroids versus calcineurin inhibitors

Steroids versus azoles

Mild steroids versus strong steroids

Other comparisons for steroids

Calcineurin inhibitors versus comparators

Calcineurin inhibitors versus placebo

Calcineurin inhibitors versus azoles

Calcineurin inhibitors versus zinc pyrithione

Lithium versus comparators

Lithium salts versus placebo

Lithium salts versus azoles

For each of these comparisons, we addressed our prespecified outcomes. Our primary outcomes were as follows.

Percentage of treated persons with total resolution of symptoms as evaluated by the outcome assessor (total clearance).

Disease severity scores for scaling, pruritus, or erythema at the end of treatment as evaluated by participant self‐report, outcome assessor, or both.

Percentage of persons treated who develop side‐effects or intolerance to treatment.

With regard to our primary outcome 'Total clearance', we considered this to be present where the terms "complete" or "total" resolution of symptoms or cure or clearance were used, whereas we did not accept as total clearance the term "excellent" without any definition of its meaning. Total clearance was the investigator's assessment unless otherwise stated. The included studies reported our other primary outcomes 'Disease severity' and 'Adverse events'.

None of the included studies assessed our secondary outcome 'Quality of life'.

Steroids versus comparators

We identified six studies comparing steroids with placebo or vehicle, five studies comparing steroids with calcineurin inhibitors, and 12 studies comparing steroids with azoles. Of these studies, one compared steroid with placebo and azole, one compared steroid with calcineurin inhibitor and azole, and one compared steroid with calcineurin inhibitor and zinc pyrithione. Additionally, we identified one study that compared steroid with Promiseb®, which is a non‐steroidal compound, and one study that compared steroid with calcipotriol (vitamin D).

We performed subgroup analyses using the strength of the steroid compound as classification criterion. We classified class I and II steroids as mild steroids, and we classified class III and IV steroids as strong steroids. Five identified studies compared strong steroids with mild steroids. Furthermore, we identified two studies comparing a mild steroid with another mild steroid (Cornell 1986; Cornell 1993), and one study comparing a strong steroid with another strong steroid (Cornell 1989). We did not display the results for these three comparisons, as the focus of this review is to compare anti‐inflammatory treatments with placebo and comparisons between different anti‐inflammatory treatment classes. We also included analyses comparing mild steroids with strong steroids. We consider these comparisons to be most important from the clinical decision‐making point of view.

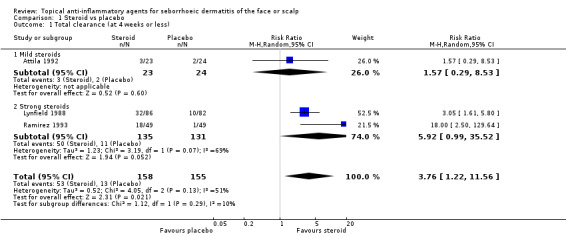

Steroids versus placebo

In our analyses, steroids displayed a stronger effect on the studied outcomes than placebo with a comparable safety profile.

Total clearance (at four weeks or less of treatment)

Three studies, with a total of 303 participants, investigated this outcome. Participants achieved 'Total clearance' with steroids more often than with placebo (risk ratio (RR) 3.76, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22 to 11.56) when pooling steroids together (Analysis 1.1) (number needed to treat (NNT) 4, 95% CI 3 to 6). Two studies not included in this meta‐analysis (Harris 1972; Reygagne 2007; Table 5) further supported this finding. However, there were indications that only a strong steroid is more effective than placebo (RR 5.92, 95% CI 0.99 to 35.52) in Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Steroid vs placebo, Outcome 1 Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less).

1. Reygagne 2007.

| The study investigated clobetasol propionate shampoo (0.05%) with three different application times (2.5 minutes, 5 minutes, and 10 minutes) and the comparisons included ketoconazole and vehicle. Each group included 11 participants. Some of the results are unobtainable from the figures in the report, and only results stated in the text could be used. The study lasted 4 weeks. The study has not been included in the meta‐analyses as the mode of application was different from all other studies. | |||

| Steroid | Vehicle | Azole | |

| Total clearance | 18.2% to 45.5% (in different application groups) | 9.1% | 9.1% |

| Erythema scores¹ | 0.1 in clobetasol 5‐minute group; otherwise, not reported (P value = 0.024 for comparison with vehicle) | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Scaling scores (loose desquamation)² | 0.3 in clobetasol 10‐minute group, and 0.4 in clobetasol 5‐minute group; otherwise, not reported (P value = 0.027 for comparison between clobetasol 10‐minute group and vehicle group) | 1.0 | Not reported |

| Pruritus score | ‐ 4.8 mm in clobetasol 5‐minute group; otherwise, not reported (P value = 0.007 for comparison with vehicle) | ‐ 34 mm | ‐ not reported in text (8.9 mm approximated from figure) |

| Any adverse effects | 1 participant (9%) in all groups experienced burning. 1 participant in clobetasol 10‐minute group reported dry skin. 1 participant in clobetasol 5‐minute group reported folliculitis | 1 participant (9%) experienced burning. Eczema was reported in 1 person | 1 participant (9%) experienced burning |

¹Outcome "erythema scores" refers to erythema scores at end of study. A lower score relates to a better treatment effect. ²Outcome "scaling scores" refers to scaling scores at end of study. A lower score relates to a better treatment effect.

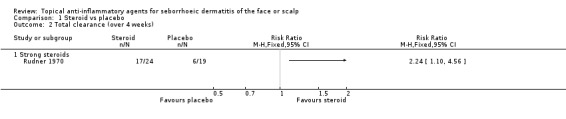

Total clearance (at four weeks or more)

One study with 43 participants examined the effect of a strong steroid on total clearance compared with placebo and found that participants achieved total clearance more often with the steroid than with placebo (RR 2.24, 95% CI 1.10 to 4.56) (Analysis 1.2) (NNT 3, 95% 1 to 11).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Steroid vs placebo, Outcome 2 Total clearance (over 4 weeks).

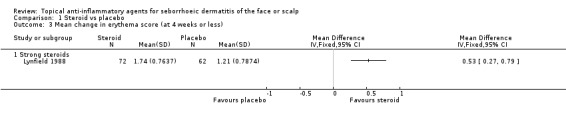

Erythema (at four weeks or less of treatment)

One study with 134 participants examined the mean change in erythema scores. There was a greater reduction in erythema score with a strong steroid (in favour of steroid) than with placebo (mean difference (MD) 0.53, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.79) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Steroid vs placebo, Outcome 3 Mean change in erythema score (at 4 weeks or less).

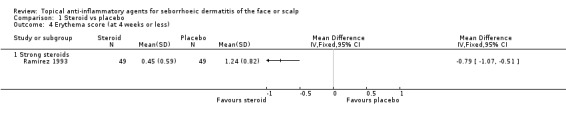

This finding is furthermore supported by another study (44 participants) (Reygagne 2007; Table 5). A study with 98 participants examined the level of erythema scores at the end of treatment and found that with strong steroid the erythema score was lower (in favour of steroid) when compared with placebo (MD ‐0.79, 95% CI ‐1.07 to ‐0.51) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Steroid vs placebo, Outcome 4 Erythema score (at 4 weeks or less).

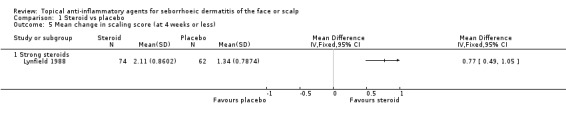

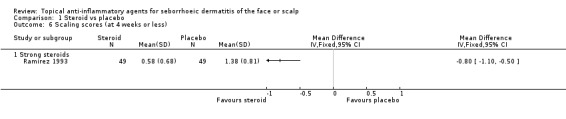

Scaling (at four weeks or less of treatment)

One study with 136 participants examined the mean change in scaling scores. There was a greater reduction in scaling score with strong steroid (in favour of steroid) than with placebo (MD 0.77, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.05) (Analysis 1.5). Another study with 98 participants reported the level of scaling scores at the end of treatment, and here also, a strong steroid was more effective than placebo because the scaling score was lower with steroid (MD ‐0.80, 95% CI ‐1.10 to ‐0.50) (Analysis 1.6).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Steroid vs placebo, Outcome 5 Mean change in scaling score (at 4 weeks or less).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Steroid vs placebo, Outcome 6 Scaling scores (at 4 weeks or less).

One study with 44 participants (Reygagne 2007; Table 5) further supported this finding.

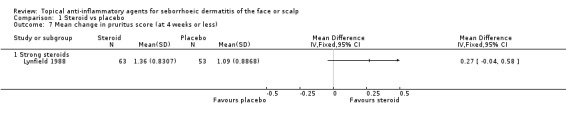

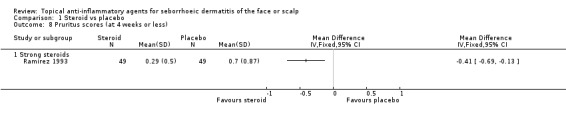

Pruritus (at four weeks or less of treatment)

One study with 116 participants examined the mean change in pruritus scores and found that there were no statistically significant differences between a strong steroid and placebo (MD 0.27, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.58) (Analysis 1.7). Another study with 98 participants reported the level of pruritus scores at the end of treatment. In this study, a strong steroid proved to be more effective than placebo (MD ‐0.41, 95% CI ‐0.69 to ‐0.13) (Analysis 1.8).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Steroid vs placebo, Outcome 7 Mean change in pruritus score (at 4 weeks or less).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Steroid vs placebo, Outcome 8 Pruritus scores (at 4 weeks or less).

Another study with 44 participants found a strong steroid to be more effective in this outcome when compared with placebo (Reygagne 2007; Table 5).

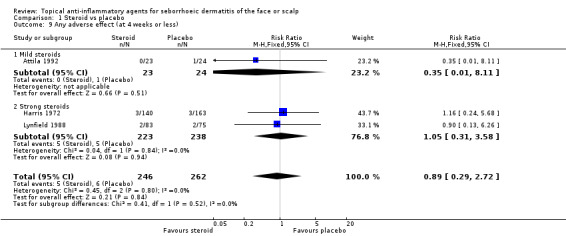

Any adverse effects

One study compared a mild steroid and placebo, and three studies compared a strong steroid and placebo. As a whole, there were 606 participants in these trials. We found no statistically significant differences between steroid treatment and placebo regardless of the strength of the steroid (pooled RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.72) (Analysis 1.9). One study with 44 participants (Reygagne 2007; Table 5) supported this finding. We could not use in meta‐analysis one study with 100 randomised participants, which reported that there were no adverse effects (Ramirez 1993), as the effect estimate was inestimable.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Steroid vs placebo, Outcome 9 Any adverse effect (at 4 weeks or less).

The most commonly reported adverse effects were burning and itching in both steroid and placebo treatment. The proportion of participants experiencing any adverse effect was mostly low, approximately two to three per cent of the total study population.

Steroids versus calcineurin inhibitors

In our analyses, there were no statistically significant differences between steroids and calcineurin inhibitors in terms of the assessed outcomes in three studies. In two studies, only the adverse events outcomes were of relevance to this review (Cicek 2009; Papp 2012). There were implications that adverse events may be more common in calcineurin inhibitor treatment when compared with steroids.

Total clearance (at four weeks or less of treatment)

There was no statistically significant difference between steroids and calcineurin inhibitors for this outcome in two studies with a combined total of 60 participants (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.32) (Analysis 2.1), and there were no conclusive statistical differences between a strong and a mild steroid when compared with calcineurin inhibitor. We rated the quality of the evidence as low (Table 1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroid vs calcineurin inhibitor, Outcome 1 Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less).

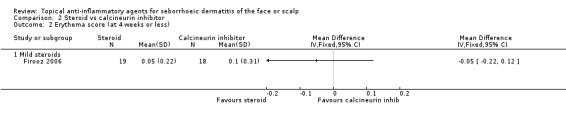

Erythema (at four weeks or less of treatment)

One study with 37 participants examined the erythema scores at the end of treatment and found that there was no statistically significant difference between a mild steroid and calcineurin inhibitor (MD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.12) (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroid vs calcineurin inhibitor, Outcome 2 Erythema score (at 4 weeks or less).

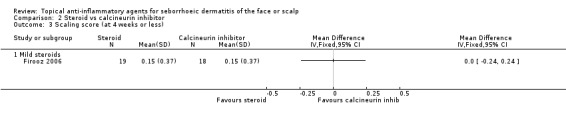

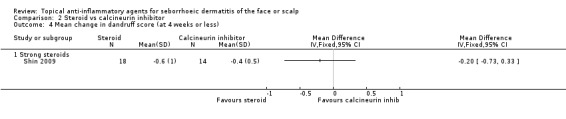

Scaling (at four weeks or less of treatment)

One study with 38 participants examined the scaling scores at the end of treatment and found that there were no statistically significant differences between steroids and calcineurin inhibitors (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.24) (Analysis 2.3). Another study with 32 participants examined the mean change in dandruff scores, and the findings of this study were similar (MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.73 to 0.33) (Analysis 2.4).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroid vs calcineurin inhibitor, Outcome 3 Scaling score (at 4 weeks or less).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroid vs calcineurin inhibitor, Outcome 4 Mean change in dandruff score (at 4 weeks or less).

Pruritus (at four weeks or less of treatment)

One study with 37 participants examined pruritus scores and found that there were no statistically significant differences between a mild steroid and calcineurin inhibitor (Firooz 2006). We could not use the results of the trial in analyses for statistical reasons. (The standard deviations were 0.00 in the other treatment arm.)

Any adverse effects

Two studies with a combined total of 60 participants examined the incidence of adverse events when comparing calcineurin inhibitors with steroids for short‐term treatment. Adverse events were found to be less common with steroid treatment (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.89) (Analysis 2.5). The most commonly reported adverse effects were erythema, burning, and prickling sensations.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroid vs calcineurin inhibitor, Outcome 5 Any adverse effects at 4 weeks or less.

Two studies with a combined total of 72 participants examined the incidence of adverse effects for long‐term treatment. There was no statistically significant difference between steroid and calcineurin‐inhibitor treatment (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.47) (Analysis 2.6). One study with 54 participants (Shin 2009) did not report adverse effects with sufficient detail.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroid vs calcineurin inhibitor, Outcome 6 Any adverse effects (at 4 weeks or more).

Steroids versus azoles

No statistically significant differences were found between steroids and azoles in their efficacy in producing total clearance when evaluated by the investigator for short‐term treatment, whereas when evaluated by the participant, azole treatment was found to be more effective than a mild steroid. For short‐term treatment, the effect of azoles was milder than that of (at least strong) steroids on erythema, scaling, or pruritus. When long‐term treatment was given, an azole compound was found to be more effective than a steroid compound in producing total clearance. There seemed to be no differences between steroids and azoles for adverse effects; however, in one study of long‐term use, there were more adverse effects with a strong steroid than with an azole compound.

Total clearance (at four weeks or less of treatment)

A total of eight studies with a combined number of 464 participants assessed the comparative effectiveness of steroids and azoles in producing total clearance and found that there were no statistically significant differences between them (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.32) when judged by the investigator (Analysis 3.1). The finding was similar in studies investigating mild and strong steroids. We rated the quality of the evidence as moderate (Table 2).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Steroid vs azole, Outcome 1 Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less).

One study with 44 participants, which we did not include in the meta‐analysis, reached inconclusive results (Reygagne 2007; Table 5). There was also one study (62 participants) with conflicting results where azole treatment was more effective than steroid treatment in producing an excellent (this trial did not use total clearance as an outcome) response (Ortonne 1992).

Two studies assessed the comparative effectiveness of steroids and azoles in producing total clearance when judged by the participant. In one study with 101 participants, azole treatment was more effective in producing total clearance when compared with a mild steroid (RR 1.55, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.21) (Piepponen 1992), whereas in another study with 69 participants, there were no statistically significant differences between a strong steroid and an azole treatment (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.23) (Van't Veen 1998) (Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Steroid vs azole, Outcome 2 Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less, evaluated by participant).

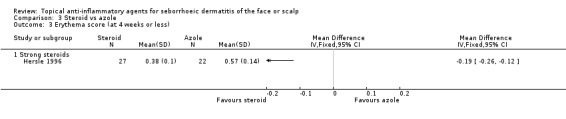

Erythema (at four weeks or less of treatment)

Three studies with a combined total of 160 participants addressed the effect of steroids and azoles on erythema evaluated by erythema scores at the end of treatment. One study (49 participants) comparing a strong steroid with azole found steroid to be more effective (MD ‐0.19, 95% CI ‐0.26 to ‐0.12) (Analysis 3.3). In two studies comparing mild steroids with azoles (111 participants), the results were inconsistent (Kousidou 1992; Stratigos 1988). We could not use these trials in the analysis because of missing statistical data.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Steroid vs azole, Outcome 3 Erythema score (at 4 weeks or less).

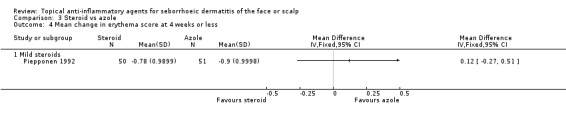

One study (101 participants, mild steroid) assessed the mean change in erythema scores. There was no statistically significant difference between the two treatments (MD 0.12, 95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.51) (Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Steroid vs azole, Outcome 4 Mean change in erythema score at 4 weeks or less.

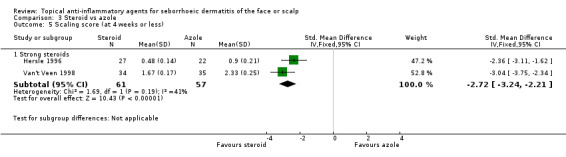

Scaling (at four weeks or less of treatment)

Two studies with a combined total of 118 participants addressed the effect of steroids when compared with azoles on scaling evaluated by scaling scores at the end of treatment. Strong steroids were associated with statistically significantly lower scaling scores (in favour of steroids) at the end of treatment (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐2.72, 95% CI ‐3.24 to ‐2.21 for strong steroids, two studies) (Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Steroid vs azole, Outcome 5 Scaling score (at 4 weeks or less).

By contrast, there was a high degree of heterogeneity (I² statistic of 90%) between the results for the two trials comparing mild steroids with azoles (Kousidou 1992; Stratigos 1988, altogether 111 participants). The first mentioned trial found azole treatment to be more effective when compared with steroid (MD 0.92, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.59, 39 participants), whereas the results of the latter trial displayed no statistically significant difference between steroid and azole treatment (MD ‐0.38, 95% CI ‐0.85 to 0.08, 72 participants).

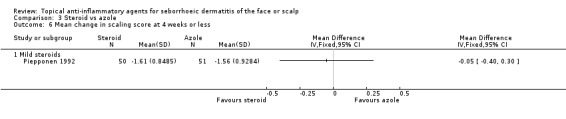

One study with 101 participants addressed the mean change in scaling scores and found that the treatments were equally effective (MD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.30) (Analysis 3.6).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Steroid vs azole, Outcome 6 Mean change in scaling score at 4 weeks or less.

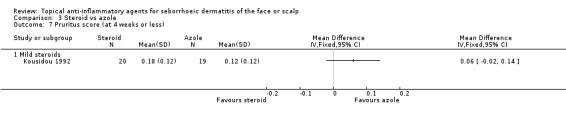

Pruritus (at four weeks or less of treatment)

Five studies with a combined total of 260 participants assessed the effect of steroids and azoles on pruritus evaluated by pruritus scores at the end of treatment. One trial with mild steroids (Stratigos 1988, 72 participants) noted no statistically significant difference in pruritus at four weeks (72 participants). We could not use the results of this trial in the meta‐analysis because of lack of statistical data. In the other trial with mild steroids, the treatments seemed comparable as well (MD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.14, 39 participants) (Analysis 3.7).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Steroid vs azole, Outcome 7 Pruritus score (at 4 weeks or less).

The results of three studies with strong steroids displayed a high degree of heterogeneity (I² statistic of 83%), and therefore we could not pool them together in a meta‐analysis. However, in two of these trials, there were indications that strong steroids are more effective than azoles in reducing pruritus (MD ‐1.52, 95% CI ‐2.17 to ‐0.88, 49 participants in Hersle 1996) (MD ‐1.81, 95% CI ‐2.38 to ‐1.25, 69 participants in Van't Veen 1998), whereas in the third study, there were no statistically significant differences between a strong steroid and azole treatment (MD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐0.99 to 0.43, 31 participants) (Pari 1998).

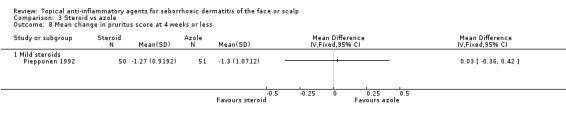

One study with 101 participants evaluated the mean change in pruritus scores and found that the treatments were equally effective (MD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.42) (Analysis 3.8).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Steroid vs azole, Outcome 8 Mean change in pruritus score at 4 weeks or less.

Total clearance (at more than four weeks of treatment)

Only one study (Ortonne 1992), with 62 participants lasting four months, assessed clearance as a long‐term outcome. However, this trial did not measure total clearance; instead, it evaluated excellent clearance. We did not predefine excellent clearance as an outcome of interest.

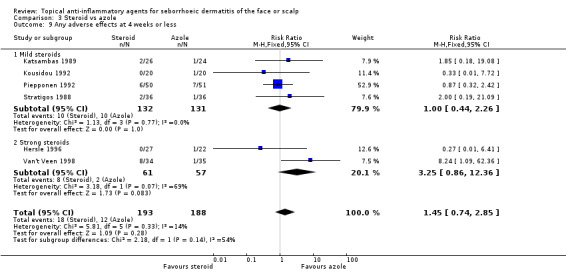

Any adverse effects

Three studies did not report adverse effects at all (Faergemann 1986; Fredriksson 1978; Pari 1998).

Altogether, six studies with a combined total of 381 participants reported the occurrence of any adverse effects at four weeks or less of treatment, and there was no statistically significant difference between steroid and azole treatment (RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.74 to 2.85) (Analysis 3.9). Adverse effects most often reported were dryness of skin, burning, and dandruff. Dryness of skin was more often associated with steroid treatment than with azole treatment.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Steroid vs azole, Outcome 9 Any adverse effects at 4 weeks or less.

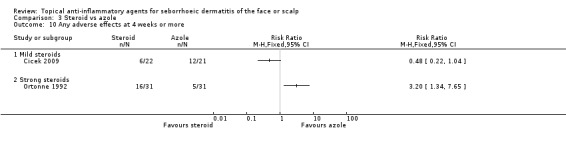

In the long‐term studies (four weeks or more of treatment) comparing steroid and azole treatment, strong steroids seemed to produce adverse effects more often than azoles (RR 3.20, 95% CI 1.34 to 7.65, one study with 62 participants), whereas there were no statistically significant differences between mild steroid and azole treatment in one study with 43 participants (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.04) (Analysis 3.10).

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Steroid vs azole, Outcome 10 Any adverse effects at 4 weeks or more.

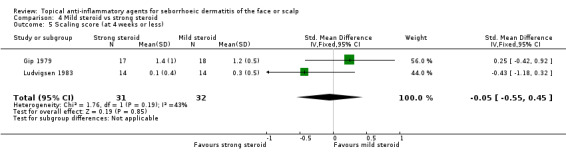

Mild steroids versus strong steroids

We compared mild steroids (class I and II steroids) with strong steroids (class III or IV) in three studies. In general, there were no differences between mild and strong steroids with regard to the assessed outcomes including adverse effects.

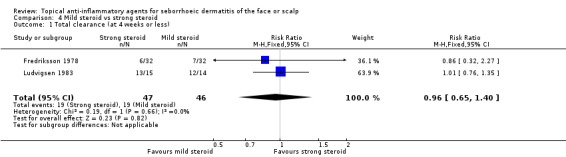

Total clearance (at four weeks or less of treatment)

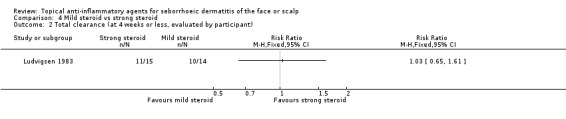

Two studies lasting four weeks or less, with 93 participants, assessed total clearance. We found that there were no statistically significant differences between mild or strong steroids whether total clearance was evaluated by the investigator (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.40) (Analysis 4.1; Table 3) or by the participant (one study, 29 participants) (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.61) (Analysis 4.2). We rated the quality of the evidence as moderate.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mild steroid vs strong steroid, Outcome 1 Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mild steroid vs strong steroid, Outcome 2 Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less, evaluated by participant).

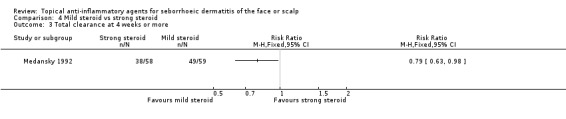

Total clearance (at more than four weeks of treatment)

One study with 117 participants assessed total clearance at four weeks or more. In this study, we found a mild steroid to be more effective than a strong steroid (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.98) (NNT 6, 95% CI 3 to 59) (Analysis 4.3). We rated the quality of the evidence as low (Table 4).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mild steroid vs strong steroid, Outcome 3 Total clearance at 4 weeks or more.

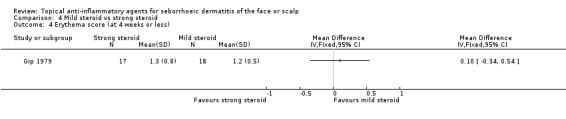

Erythema (at four weeks or less of treatment)

Two studies with a combined total of 55 participants assessed the effect of mild or strong steroids on erythema evaluated with erythema scores. We found that there was no statistically significant difference between mild and strong steroids (MD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.34 to 0.54, one study, 35 participants) (Analysis 4.4). Another trial (Ludvigsen 1983) with 20 participants supported this finding. We could not use the results of the latter trial in the analysis because of a lack of statistical data.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mild steroid vs strong steroid, Outcome 4 Erythema score (at 4 weeks or less).

Scaling (at four weeks or less of treatment)

Two studies with a combined total of 63 participants assessed the effect of mild or strong steroids on scaling evaluated with scaling scores, and we found that there was no statistically significant difference (SMD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.55 to 0.45) (Analysis 4.5).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mild steroid vs strong steroid, Outcome 5 Scaling score (at 4 weeks or less).

Pruritus (at four weeks or less of treatment)

Three studies with a combined total of 114 participants assessed the effect of mild or strong steroids on pruritus evaluated with pruritus scores, and we found that there was no statistically significant difference (SMD 0.13, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.50) (Analysis 4.6).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mild steroid vs strong steroid, Outcome 6 Pruritus score (at 4 weeks or less).

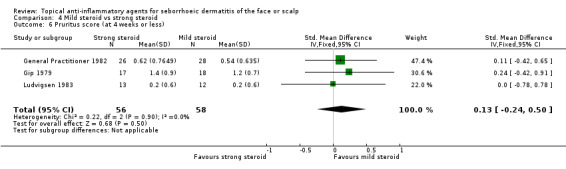

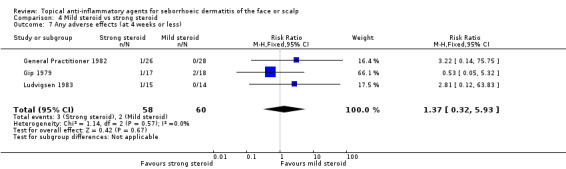

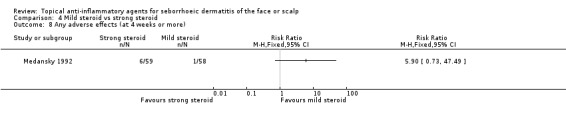

Any adverse effects

When used in the short‐term, there was no statistically significant difference between mild and strong steroids with regard to rate of adverse effects (RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.32 to 5.93) in three studies with a combined total of 118 participants (Analysis 4.7), and in long‐term use, the finding was similar (RR 5.90, 95% CI 0.73 to 47.49) in one study with 117 participants (Analysis 4.8). The reported adverse effects were scalp dryness or appearance of papules or other kinds of rash.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mild steroid vs strong steroid, Outcome 7 Any adverse effects (at 4 weeks or less).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mild steroid vs strong steroid, Outcome 8 Any adverse effects (at 4 weeks or more).

Other comparisons for steroids

There were two additional studies that compared a mild steroid with another mild steroid (Cornell 1986; Cornell 1993), and one study compared a strong steroid with another strong steroid (Cornell 1989). We did not perform analyses on these studies as we were focusing on differences between different classes of drugs.

One study with 56 participants compared a strong steroid (betamethasone) with zinc pyrithione, and we found no statistically significant differences in their effect on scaling (MD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐0.92 to 0.12) (Analysis 5.1), but this study (Shin 2009) did not report adverse effects.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Steroid vs zinc pyrithione, Outcome 1 Scaling score (< 4 weeks).

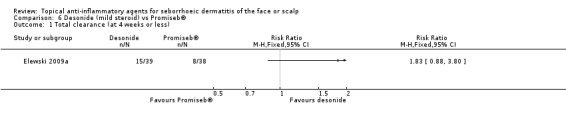

One study with 77 participants compared a mild steroid (desonide) with non‐steroidal cream, Promiseb® (Elewski 2009a). There was no statistically significant difference in the effect on total clearance (RR 1.83, 95% CI 0.88 to 3.80) (Analysis 6.1). In the same study, there were no statistically significant differences between the two drugs with regard to their ability to reduce erythema, scaling, or pruritus or to produce adverse effects.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Desonide (mild steroid) vs Promiseb®, Outcome 1 Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less).

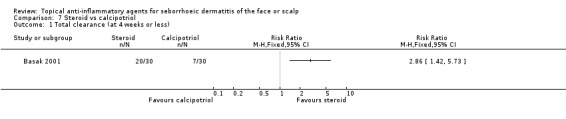

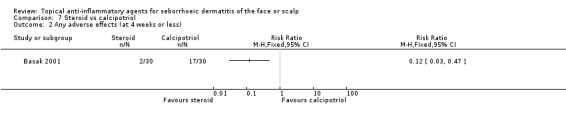

One study with 60 participants compared steroid with calcipotriol (vitamin D compound) (Basak 2001). In this study, steroid proved to be more effective in accomplishing total clearance when compared with calcipotriol (RR 2.86, 95% CI 1.42 to 5.73) (Analysis 7.1). Furthermore, the incidence of adverse effects was lower with steroid treatment than with calcipotriol treatment (RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.47) (Analysis 7.2).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Steroid vs calcipotriol, Outcome 1 Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Steroid vs calcipotriol, Outcome 2 Any adverse effects (at 4 weeks or less).

Calcineurin inhibitors versus comparators

We identified four studies comparing calcineurin inhibitors to steroids as described above. Of these, one study compared calcineurin inhibitor with azole and steroid, one compared calcineurin inhibitor with steroid and zinc pyrithione, one compared calcineurin inhibitor with placebo, and one compared calcineurin inhibitor with azole only.

Calcineurin inhibitors versus placebo

One study with 96 participants found calcineurin inhibitors to be more effective in reducing erythema and scaling when compared with placebo. There were no differences in total clearance or adverse effects between calcineurin inhibitors and placebo.

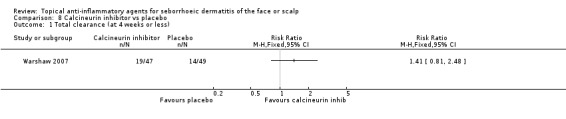

Total clearance (at four weeks or less of treatment)

We identified only one study (96 participants) assessing the effect of calcineurin inhibitors on total clearance when compared with placebo; there was no statistically significant difference in the effect on total clearance (RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.48) (Analysis 8.1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Calcineurin inhibitor vs placebo, Outcome 1 Total clearance (at 4 weeks or less).

Erythema (at four weeks or less of treatment)

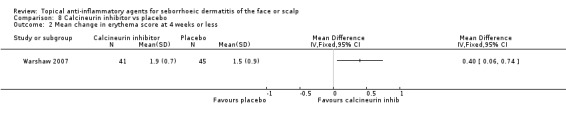

This study (results available for 86 participants) compared the effect of calcineurin inhibitors on erythema with placebo, and we found that calcineurin inhibitor was more effective in reducing erythema when evaluated by mean change in erythema scores (MD 0.40, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.74) (Analysis 8.2).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Calcineurin inhibitor vs placebo, Outcome 2 Mean change in erythema score at 4 weeks or less.

Scaling (at four weeks or less of treatment)

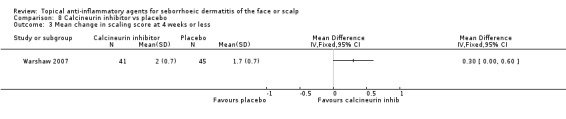

This study (results available for 86 participants) compared the effect of calcineurin inhibitor on scaling with placebo. We found that calcineurin inhibitor was more effective in reducing scaling as evaluated by mean change in scaling scores (MD 0.30, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.60) (Analysis 8.3).

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Calcineurin inhibitor vs placebo, Outcome 3 Mean change in scaling score at 4 weeks or less.

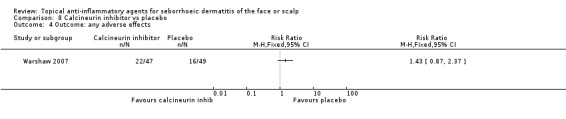

Any adverse effects

In this study (results available for 86 participants), the proportion of participants experiencing adverse effects (at four weeks or less of treatment) was not statistically significantly different between the calcineurin inhibitor group and the placebo group (RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.87 to 2.37) (Analysis 8.4). The nature of these adverse events was not reported.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Calcineurin inhibitor vs placebo, Outcome 4 Outcome: any adverse effects.

Calcineurin inhibitors versus azoles

We identified two studies with a combined total of 90 participants assessing the effect of calcineurin inhibitors when compared with azoles. Of these, in one study, there were data concerning adverse effects relevant for this review. These two studies did not assess total clearance. With regard to efficacy outcomes, we identified no statistically significant differences between calcineurin inhibitors and azoles. Evidence concerning adverse effects was not conclusive.

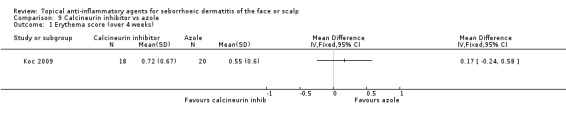

Erythema (at four weeks or more of treatment)

In one study with 38 participants, we found no statistically significant differences between a calcineurin inhibitor and an azole in their effect on erythema evaluated with erythema scores at the end of treatment (MD 0.17, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.58) (Analysis 9.1).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Calcineurin inhibitor vs azole, Outcome 1 Erythema score (over 4 weeks).

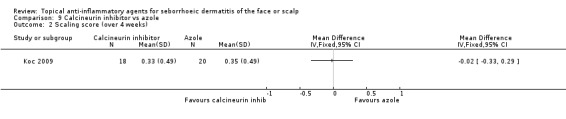

Scaling (at four weeks or more of treatment)

In the same study, we found the calcineurin inhibitor to be comparable to azole treatment in its effect on scaling evaluated with scaling scores at the end of treatment (MD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.33 to 0.29) (Analysis 9.2).

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Calcineurin inhibitor vs azole, Outcome 2 Scaling score (over 4 weeks).

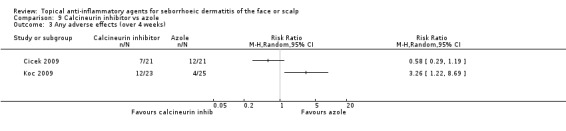

Any adverse effects

Two studies with a combined total of 90 participants addressed the incidence of adverse effects (at four weeks or more of treatment) (Analysis 9.3). Their results were conflicting with a heterogeneity (I² statistic) of over 80%; therefore, we did not use their results in a meta‐analysis. In a study with 42 participants, there were no statistically significant differences in adverse effect rate between calcineurin inhibitor treatment and azole treatment (Cicek 2009). In another trial with 58 participants, there were more adverse events in calcineurin inhibitor treatment when compared with azole treatment (Koc 2009). The trial reported burning, pruritus, and irritation as adverse effects.

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Calcineurin inhibitor vs azole, Outcome 3 Any adverse effects (over 4 weeks).

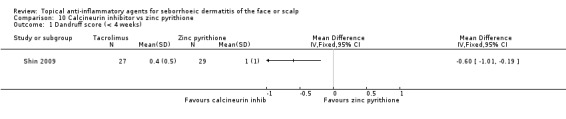

Calcineurin inhibitors versus zinc pyrithione

One study compared calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus) with zinc pyrithione. It also included a comparison with a steroid. We found that when compared with zinc pyrithione, calcineurin inhibitor was more effective in reducing the dandruff scores (MD ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐1.01 to ‐0.19) (Analysis 10.1). The study did not report adverse effects in sufficient detail (Shin 2009).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Calcineurin inhibitor vs zinc pyrithione, Outcome 1 Dandruff score (< 4 weeks).

Lithium versus comparators

We identified two studies comparing lithium salts with placebo (Dreno 2002a; Langtry 1997) and one study comparing lithium salt with azole treatment (Dreno 2003). Lithium seemed to be more effective than placebo with regard to total clearance, but concerning erythema or scaling, there were no statistically significant differences between lithium and placebo. Lithium was also more effective when compared with azole with regard to total clearance. The differences between lithium and its comparators were ambiguous with regard to adverse effects, which were most often burning, erythema, dryness, and pruritus.

Lithium salts versus placebo

Lithium seems to be more effective when compared with placebo with regard to total clearance, with a comparable safety profile.

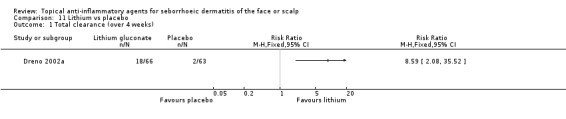

Total clearance (at four weeks or more of treatment)

Only one study with 129 participants assessed total clearance. We found that lithium was more effective than placebo (RR 8.59, 95% CI 2.08 to 35.52) (NNT 4, 95% CI 3 to 9) (Analysis 11.1).

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Lithium vs placebo, Outcome 1 Total clearance (over 4 weeks).

Erythema (at four weeks or less of treatment)

One study with 12 participants assessed the effect of lithium salts on erythema, comparing it to placebo (Langtry 1997). This study was a body‐part study on HIV‐positive male participants. At two weeks of treatment, It was found that there were no statistically significant differences in the percentage change in erythema scores between the lithium compound (30.7% of the baseline value) and placebo treatment (47.1% of the baseline value) (P = 0.055). However, at this point, 50% of the participants had already dropped out.

Scaling (at four weeks or less of treatment)

One study assessed the effect of lithium salts on scaling, comparing it to placebo. This study was a body‐part randomisation study on 12 HIV‐positive male participants (Langtry 1997). At two weeks of treatment, it was found that there were no statistically significant differences in the percentage change in erythema scores between the lithium compound (19.5% of the baseline value) and the placebo treatment (33.8% of the baseline value) (P = 0.76). However, at this point, 50% of the participants had already dropped out.

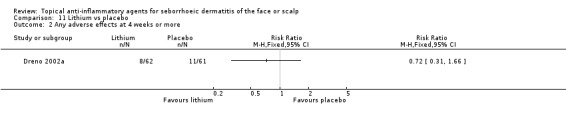

Any adverse effects

In one study lasting for eight weeks, there was no statistically significant difference between lithium and placebo in the occurrence of adverse effects (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.66, 123 participants) (Analysis 11.2). In this study, the adverse effects reported most often were burning, erythema, and pruritus. The report of the other study (Langtry 1997) comparing lithium to placebo was imprecise regarding adverse effects.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Lithium vs placebo, Outcome 2 Any adverse effects at 4 weeks or more.

Lithium salts versus azoles

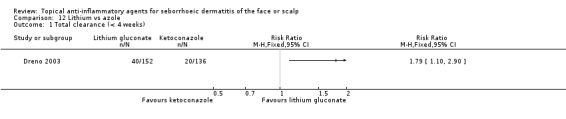

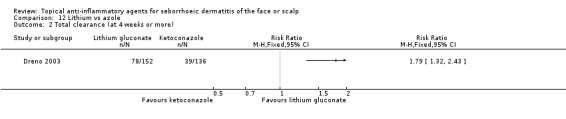

Total clearance (at four weeks or less of treatment)

One study with 288 participants compared the effect of lithium salt with azole on total clearance of SeD. In this study, we found that lithium salt was more effective (RR 1.79, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.90) (Analysis 12.1) in terms of short‐term results (four weeks). We rated the quality of the evidence as low (Table 4).

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Lithium vs azole, Outcome 1 Total clearance (< 4 weeks).