Abstract

Background

Ten per cent to 15% of couples have difficulty in conceiving. A proportion of these couples will ultimately require assisted reproduction. Prior to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) a baseline ultrasound is performed to detect the presence of ovarian cysts.

Previous research has suggested that there is a relationship between the presence of an ovarian cyst prior to COH and poor outcome of in vitro fertilization (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Objectives

The aim of this review was to determine the effectiveness and safety of functional ovarian cyst aspiration prior to ovarian stimulation versus a conservative approach in women with an ovarian cyst who were undergoing IVF or ICSI.

Search methods

We searched the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Specialised Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.gov, Google Scholar and PubMed. The evidence was current to April 2014 and no language restrictions were applied.

Selection criteria

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing functional ovarian cyst aspiration versus conservative management of ovarian cysts that have been seen on transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) prior to COH for IVF or ICSI. Ovarian cysts were defined as simple, functional ovarian cysts > 20 mm in diameter. Oocyte donors and women undergoing donor oocyte cycles were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection, data extraction and risk of bias assessments were conducted independently by two review authors. The primary outcome measures were live birth rate and adverse events. The overall quality of the evidence for each comparison was rated using GRADE methods.

Main results

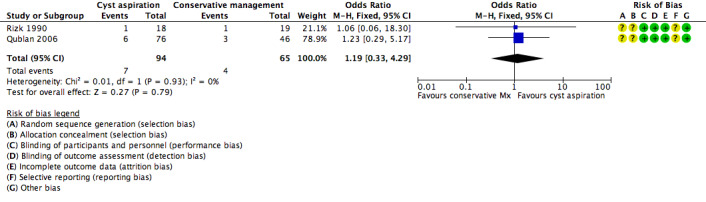

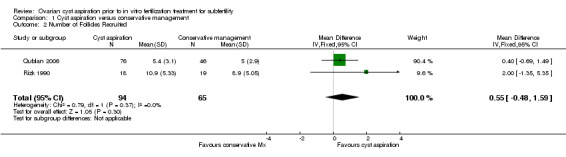

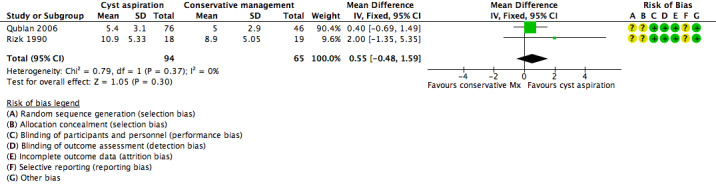

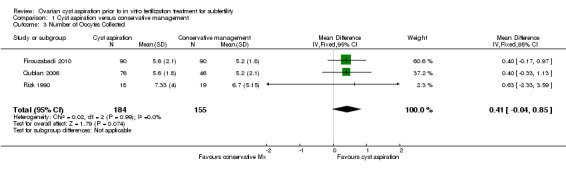

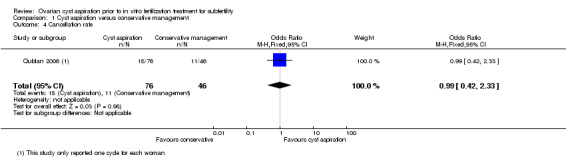

Three studies were eligible for inclusion (n = 339), all of which used agonist protocols. Neither live birth rate nor adverse events were reported by any of the included studies. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference in the clinical pregnancy rate between the group who underwent ovarian cyst aspiration and the conservatively managed group (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.33 to 4.29, two RCTs, 159 women, I2 = 0%, very low quality evidence). This suggested that if the clinical pregnancy rate in women with conservative management was assumed to be 6%, the chance following cyst aspiration would be between 2% and 22%. There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in the mean number of follicles recruited (0.55 follicles, 95% CI ‐0.48 to 1.59, 2 studies, 159 women, I2 = 0%, very low quality evidence) mean number of oocytes collected (0.41 oocytes, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.85, 3 studies, 339 women, I2 = 0%, low quality evidence) or cancellation rate (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.42 to 2.33, one RCT, 122 women, very low quality evidence). The main limitations of the evidence were imprecision, risk of bias associated with poor reporting of study methods, and inconsistent reporting of study findings in one RCT which meant that some of the data could not be used.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to determine whether drainage of functional ovarian cysts prior to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation influences rates of live birth, clinical pregnancy, number of follicles recruited, or number of oocytes collected in women with a functional ovarian cyst. The findings of this review do not provide supportive evidence for this approach, particularly in view of the requirement for anaesthesia, extra cost, psychological stress and risk of surgical complications.

Plain language summary

Ovarian cyst aspiration and IVF outcomes

Review question

Cochrane authors investigated the effectiveness and safety of cyst aspiration before ovarian stimulation versus a conservative approach (no aspiration) in women undergoing In vitro fertilization (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Our primary outcomes were live birth rate and adverse events. We also assessed pregnancy rates, number of follicles recruited, and number of oocytes retrieved.

Background

IVF is a treatment for infertility in which a woman's eggs (oocytes) are fertilized by sperm in a laboratory dish. One or more of the fertilized eggs (embryos) are then transferred into the woman's uterus, where it is hoped the egg will implant and result in a pregnancy.

The woman's ovaries are stimulated to produce multiple eggs which are then retrieved for fertilization by sperm. This differs from what usually occurs, when one egg is produced by the ovary. Stimulation of the ovaries is achieved by a woman taking several different drugs to maximise the chance of getting several eggs suitable for fertilization. Prior to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) a baseline ultrasound is performed to detect the presence of any functional ovarian cysts. The evidence on the effect of draining such an ovarian cyst on the end result of IVF was examined in this review.

Study characteristics

Three randomized controlled trials were included involving 339 women of reproductive age who required IVF treatment due to tubal factor infertility, anovulation, male factor infertility, endometriosis or fertility of unknown cause. These studies compared the outcome of IVF cycles in women whose cyst was drained versus the outcomes when the cyst was not drained. The evidence was current to April 2014.

Key results

None of the included studies reported live birth rates or adverse event rates. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was any difference in the pregnancy rate, the number of follicles recruited, or the number of eggs retrieved, between women who had their cyst drained and women who did not.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was low or very low for all comparisons, the main reasons for this being small study numbers, low numbers of events and poor reporting of study methods. There was inconsistent reporting of study findings in one RCT, which meant that some of the data could not be used

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Cyst aspiration versus conservative management for subfertility.

| Cyst aspiration versus conservative management for subfertility | ||||||

| Population: women with subfertility Settings: infertility and IVF centres in Jordan, Iran and the United Kingdom (London) Intervention: cyst aspiration versus conservative management | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Conservative management | Cyst aspiration | |||||

| Live birth rate | This primary review outcome was not reported in any of the included studies | Not estimable | ||||

| Adverse events rate | This primary review outcome was not reported in any of the included studies | Not estimable | ||||

| Clinical pregnancy rate Ultrasound diagnosis of intrauterine pregnancy | 62 per 1,000 | 72 per 1,000 (21 to 220) |

OR 1.19 (0.33 to 4.29) |

159 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1,2 | |

| Number of follicles recruited Ultrasound diagnosis | The mean number of follicles recruited in the cyst aspiration groups was 0.55 higher (0.48 lower to 1.59 higher) | 159 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1,2 | |||

| Number of oocytes collected Transvaginal oocyte aspiration | The mean number of oocytes collected in the cyst aspiration groups was 0.41 higher (0.04 lower to 0.85 higher) | 339 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | |||

| Cancellation rate per cycle | 239 per 1,000 | 237 per 1,000 (117 to 423) |

OR 0.99 (0.42 to 2.33) |

122 (1 study) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ Very low1,2 | Each woman had only one cycle |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for serious risk of bias; none of the studies adequately described their methods of randomization and allocation concealment 2 Downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision: wide confidence interval compatible with benefit in either group or no effect, and/or very low event rate 3 Downgraded one level for serious imprecision: wide confidence interval compatible with benefit in either group or no effect

Background

Description of the condition

Ten per cent to 15% of couples have difficulty in conceiving (Speroff 2011). A proportion of these couples will ultimately require assisted reproduction, including in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Prior to IVF the pituitary is down‐regulated with either gonadotropin‐releasing hormone agonists (GnRHa), using long, short or flare‐up protocols, or the use of a GnRH antagonist. The GnRHa functions to suppress endogenous pituitary gonadotropin secretion by down‐regulation of receptors and thereby prevents a premature luteinising hormone (LH) surge during exogenous gonadotropin stimulation. The advantage of a GnRHa is that it reduces the need for frequent LH monitoring and reduces cycle cancellation due to premature luteinisation, prior to oocyte retrieval. The downside of using a GnRHa is that it sometimes blunts the response of the ovary to gonadotropin stimulation and increases the dose and duration of gonadotropin therapy required to stimulate follicular development.

Another option for ovarian stimulation is the use of GnRH antagonists, which block the GnRH receptor in a dose‐dependent, competitive fashion. The advantage of using a GnRH antagonist is that gonadotropin suppression is almost immediate and therefore the duration of treatment is substantially decreased compared to a cycle using a GnRHa (Speroff 2011). Secondly, GnRH antagonists do not cause the same flare effect as cycles using GnRHa, therefore the risk of stimulating the development of a functional ovarian cyst is reduced (Depalo 2012).

Prior to ovarian stimulation a baseline ultrasound is performed to detect the presence of functional ovarian cysts (Greenebaum 1992). An incidence of up to 13.6% of functional ovarian cysts has been reported in the literature following pituitary down‐regulation (Ron‐El 1989). A large variation in incidence is due to the differences in the definition of an ovarian cyst that is used, the age and ovarian reserve of the women, type of protocol, and small sample sizes (Jenkins 1996).

Previous research has suggested that there is a relationship between the presence of a functional ovarian cyst prior to ovarian stimulation and poor outcome during IVF (Jenkins 1993). It is proposed that the presence of a baseline functional ovarian cyst disrupts the final stages of folliculogenesis by reducing the area available for follicular development and by altering local angiogenesis (Segal 1999). Some authors report that there are no effects on the clinical response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) (Hornstein 1989; Penzias 1992) whilst others have documented greater gonadotropin utilisation when a conservative approach is used. These authors found that this approach resulted in subsequent lower numbers of oocytes retrieved and consequently lower pregnancy rates (Segal 1999; Zeyneloglu 1998).

The exact mechanism of ovarian cyst formation remains unclear. Several explanations have been suggested (Firouzabadi 2010) and these include the effect of primary flare‐up caused by the GnRHa affecting gonadotropins; inadequate suppression of circulating gonadotropins following pituitary suppression; the direct effect of GnRHa on the ovaries and subsequent steroidogenesis; the quantity of progesterone at the time of GnRH therapy; and the persistence of a follicular or corpus luteum cyst formed in the preceding cycle (Rizk 1990).

Description of the intervention

Different methods have been employed to manage these functional ovarian cysts and include continuing the GnRHa suppression, the administration of a combined oral contraceptive pill until the cyst has resolved (a conservative approach), and surgical cyst aspiration (Biljan 1998). Some authors report that the presence of such ovarian cysts do not impact on the subsequent clinical response to COH in IVF cycles (Hornstein 1989; Penzias 1992). Meanwhile, other authors are concerned that longer suppression with GnRHa is associated with greater gonadotropin utilisation, fewer mature oocytes, and consequently lower pregnancy rates (Segal 1999; Zeyneloglu 1998).

Possible adverse events might include infection, bleeding, injury to surrounding structures, need for further surgery including oophorectomy, anaesthetic complications, and the costs of both the procedure itself and any subsequent complications. Ovarian cyst aspiration is generally a simple procedure however complications may occasionally arise.

The transvaginal route has the disadvantage of being semi‐sterile, and this carries with it a potential risk of infecting pelvic structures. Bleeding and bowel injury have been reported however the risk of these complications is low due to the inherent advantage of real time ultrasound (O'Neill 2001). The most common complication is infection, which has been reported in one study to occur at a rate of 1.3%. In both reported cases in this study the resulting pelvic infection caused the loss of an ovary (Rizk B, Kingsland C, unpublished data). Although low risk, the possibility of this complication should be considered in women with a single ovary.

How the intervention might work

Some studies have suggested that ovarian cysts may decrease the chance of pregnancy in an IVF cycle as their presence may increase the risk of cycle cancellation (Keltz 1995). An adverse effect of ovarian cysts on the outcome of IVF could be mediated by three mechanisms (Rizk 1990).

1. A potential endocrine effect with disruption of the final stages of the preovulatory follicles. This is thought to be mediated by early luteinisation, premature LH surge and rise of progesterone levels thereby reducing oocyte quality and producing a negative effect on the endometrium.

2. A mechanical effect whereby the ovarian cyst may physically reduce the space for other follicles to develop.

3. Alteration of the blood supply to the detriment of follicular development by reducing the number and quality of oocytes collected.

IIt has been suggested that the aspiration of these functional ovarian cysts prior to the commencement of COH may increase the live birth rate.

Why it is important to do this review

The aim of this Cochrane review was to determine whether aspiration of simple, functional ovarian cysts (> 20 mm) prior to COH improves the number of follicles recruited, the number of oocytes retrieved, and subsequent live birth rates. This information would provide guidance to health consumers and IVF providers on the impact of this intervention. Considering the requirement for anaesthesia, extra cost, anxiety related to undergoing a surgical procedure and risk of surgical complications, it may be wise to treat women with ovarian cysts who are undergoing IVF treatment conservatively until evidence is available for this procedure.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to determine the effectiveness and safety of functional ovarian cyst aspiration prior to ovarian stimulation versus a conservative approach in women with an ovarian cyst who were undergoing IVF or ICSI.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Crossover and pseudo‐randomised trials were not included.

Types of participants

All women of reproductive age presenting for assisted reproductive techniques (IVF and ICSI) who were diagnosed to have simple, single non‐functional ovarian cysts greater than 2 cm in diameter at the time of ovarian stimulation. Diagnosis should have been based on vaginal ultrasound examination prior to COH. Donors and women undergoing donor oocyte cycles were not considered.

Types of interventions

Comparisons of cyst aspiration with transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) guidance versus conservative management (no aspiration) prior to COH.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Live birth rate per woman, defined as the delivery of one or more living fetuses after 20 completed weeks of gestation

Adverse events, such as infection, bleeding, injury to surrounding structures, need for further surgery including oophorectomy, anaesthetic complications and costs of both the procedure itself and any subsequent complications

Secondary outcomes

3. Clinical pregnancy per woman randomized, defined by the presence of a gestational sac determined by ultrasound examination; biochemical pregnancies were not considered

4. Number of follicles recruited per woman randomized

5. Number of oocytes collected per woman randomized

6. Cancellation rate per cycle, defined as a cycle cancelled due to an inadequate response to ovarian stimulation.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the following databases for all published and unpublished RCTs that compared cyst aspiration versus conservative management on IVF outcomes, without language restrictions and in consultation with the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator. The searches were conducted in April 2014.

Electronic searches

Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Specialised Register (Appendix 1)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Appendix 2)

MEDLINE (R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE (R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE (R) (Appendix 3)

EMBASE (Ovid) (Appendix 4)

PsycINFO (Ovid) (Appendix 5)

CINAHL (EBSCO) (Appendix 6)

PubMed (Appendix 7)

Other electronic sources of trials included the following.

Trial Registers for ongoing and registered trials: 'ClinicalTrials.gov', a service of the US National Institutes of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2home); and The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search portal (http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) (Appendix 8).

Searching other resources

In order to obtain additional relevant data, we examined reference lists of eligible articles and contacted the study authors where necessary. RH acted in the capacity of the IVF expert. Data published in the abstracts of the major international fertility meetings were also considered. Relevant searches were performed using Google Scholar (Appendix 9) and PubMed (Appendix 10).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

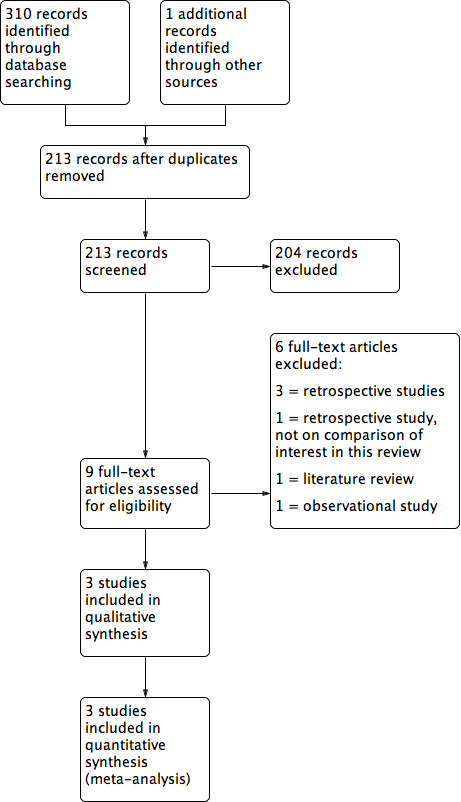

Two review authors (RM and RH) independently scanned the titles and abstracts of the articles retrieved by the search, see Figure 1. Those judged to be irrelevant were removed while the full texts of potentially eligible articles were retrieved and independently examined by two review authors (RM and RH). Full‐text articles were assessed according to the inclusion criteria and those eligible for inclusion in the review were selected. If the published study was deemed to contain insufficient information, the trial authors were contacted. Disagreements were resolved by a meeting of review authors or by consulting an external author.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted by RM and RH using a custom‐designed data extraction form. RM corresponded with study investigators in order to resolve any data queries as required.

Data were extracted on the following study characteristics:

methods (randomization, sample size, power calculation, percentage of cancelled cycles, trial design);

participants (age, duration of infertility, including range and SD);

interventions (timing of cyst diagnosis and subsequent aspiration, short or long protocol, cyst description, procedural complications, type of complication if present);

Outcomes (live birth rate, adverse events, clinical pregnancy per woman randomized, number of follicles recruited per woman randomized, number of oocytes retrieved per woman randomized, cancellation rate).

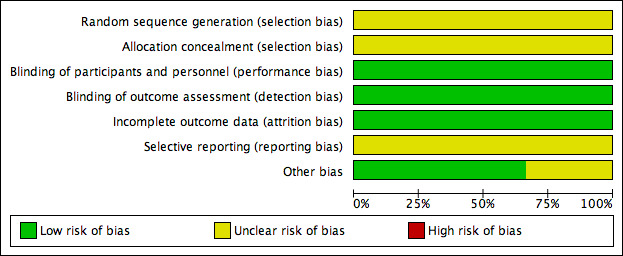

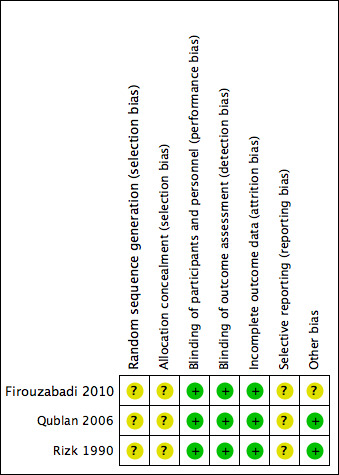

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2, Figure 3 and Characteristics of included studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

The Cochrane Collaboration's recommended tool for assessing risk of bias is a domain‐based evaluation (Cochrane 2011). Assessments were made by RM and RH for the following domains:

selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment);

performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel);

detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment);

attrition bias (incomplete outcome data);

reporting bias (selective reporting);

other bias.

These assessments were attributed a high, low, or unclear risk of bias rating.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data (for example live birth rates), the numbers of events in the control and intervention groups of each study were used to calculate the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratios (ORs).

For continuous data, if all studies reported exactly the same outcomes we planned to calculate the mean differences (MDs) between treatment groups. If similar outcomes were reported on different scales we planned to calculate the standardized mean difference (SMD).

The 95% CIs were presented for all outcomes. Where data were not available to calculate ORs or MDs we utilized the most detailed numerical data available that facilitated similar analyses of the included studies (for example test statistics, P values). We compared the magnitude and direction of effect reported by each study with how they were presented in the review, taking account of legitimate differences.

Unit of analysis issues

The primary analysis was per woman randomized to the intervention or control group. To ensure data collected from different studies were comparable, only data from the first cycle were used if a study measured multiple cycles per woman. If only per cycle data were available, we planned to report these as "Other data" rather than in forest plots.

Dealing with missing data

Trial authors were contacted by e‐mail to obtain any missing data. Several authors were contacted and no further information was provided. Only available data were included in the assessment of risk bias and the analyses. The potential impact was reported on in the discussion section.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity (variation) between the results of different studies was assessed by inspecting the scatter in the data points on a graph and the overlap of their CIs; and, more formally, by considering the I2 statistic and the P value for the Chi2 test. We planned to interpret a low P value (or a large Chi2 statistic relative to its number of degrees of freedom) as providing evidence of heterogeneity of the intervention effects (a variation in effect estimates beyond chance). In conjunction with consideration of the magnitude and direction of the effects seen, we would have interpreted the I2 statistic as follows:

• 0% to 40%, might not be important; • 30% to 60%, may represent moderate heterogeneity; • 50% to 90%, may represent substantial heterogeneity; • 75% to 100%, high heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In order to minimise the impact of reporting biases, we conducted an extensive search for eligible articles and were alert to the possibility of duplication of data. If 10 or more studies were included in one analysis we planned to construct a funnel plot in order to assess possible reporting biases.

Data synthesis

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a clinically meaningful summary. We pooled the outcomes statistically where appropriate. The meta‐analysis was carried out using Review Manager 5.3 and the data were combined using a fixed‐effect model. The effect estimate used was the Mantel‐Haenszel OR with 95% CI.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not plan any subgroup analyses. If substantial heterogeneity was found, we planned to examine clinical and methodological differences between the studies that might explain the heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to undertake sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes to determine whether the conclusions were robust to arbitrary decisions made regarding the eligibility and analysis of the studies.

These analyses included consideration of whether the review conclusions would have differed if the following were applied.

1. Eligibility was restricted to studies without high risk of bias.

2. A random‐effects model had been adopted.

3. The summary effect measure was relative risk rather than OR.

Overall quality of the body of evidence: summary of findings table

A summary of findings table was generated using GRADEPRO software. This table evaluated the overall quality of evidence for the review outcomes using GRADE criteria: study limitations (that is risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias. Judgements about evidence quality (high, moderate, or low) were justified, documented, and incorporated into reporting of results for each outcome. See Table 1.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search retrieved 310 articles. Nine studies were potentially eligible and were retrieved as the full text. Three studies met our inclusion criteria. Six studies were excluded.

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and also Figure 1.

Included studies

Study design and setting

The three included studies were RCTs, which took place in Iran (Qublan 2006), Jordan (Firouzabadi 2010) and the United Kingdom (Rizk 1990).

Participants

The studies included 184 women in the intervention groups and 155 in the control groups. All studied women presented with infertility. One of the three studies (Qublan 2006) outlined the causes of infertility. The remaining study authors (Firouzabadi 2010; Rizk 1990) were contacted to clarify the demographic data of their IVF patients, however further information was not forthcoming. The mean participant age was 22 to 43 years across the three studies. See Table 2, Table 3, Table 4.

1. Firouzabadi 2010.

| Treatment group | Control | P | |

| Randomised | 90 | 90 | |

| Cycles cancelled prior to egg collection |

2 | 13 | |

| Completed | 88 | 77 | |

| Live birth rate | Not available | Not available | |

| Clinical pregnancy rate | 10.6% | 14.3% | > 0.05 |

| Number of follicles recruited | Not available | Not available | |

| Number of oocytes collected | 5.6±2.1 | 5.2±1.8 | > 0.05 |

2. Qublan 2005 .

| Treatment group | Control | ||

| Randomised | 76 | 46 | |

| Cycle cancelled (poor response) | 17 | 12 | |

| Completed | 59 | 34 | |

| Live birth rate | Not available | Not available | |

| Clinical pregnancy rate | 10.2% | 8.8% | > 0.05 |

| Number of follicles recruited | 5.4 ± 3.1 | 5 ± 2.9 | > 0.05 |

| Number of oocytes collected | 5.6 ± 1.8 | 5.2 ± 2.1 | > 0.05 |

3. Rizk 1990 .

| Treatment group | Control | P | |

| Randomised | 18 | 19 | |

| Discontinued | 0 | 0 | |

| Completed | 18 | 19 | |

| Live birth rate | Not available | Not available | |

| Clinical pregnancy rate | 1 out of 18 (5.56%) | 1 out of 19 (5.26%) | > 0.05 |

| Number of follicles recruited | 10.9 ± 5.33 | 8.9 ± 5.05 | > 0.05 |

| Number of oocytes collected | 7.33 ± 4.0 | 6.7 ± 5.15 | > 0.05 |

Definitions of an ovarian cyst differed across the studies. Rizk et al defined an ovarian cyst as a unilocular or bilocular, sonolucent, cystic structure with mean diameters between 20 mm and 60 mm (Rizk 1990); Firouzabadi et al defined a functional ovarian cyst as being ≥ 25 mm with an ovarian structure and sonolucent thin walls; and Qublan et al defined a functional ovarian cyst as a thin‐walled intraovarian sonolucent structure with a mean diameter of ≥ 15 mm and E2 levels of ≥ 50 pg/ml (Qublan 2006)

Intervention

All three included studies compared cyst aspiration to conservative management (no cyst aspiration).

Outcomes

No included study reported the live birth rate per woman randomized.

No included study reported adverse events. Study authors were contacted but no further information was provided.

All three included studies reported on the clinical pregnancy rate (Firouzabadi 2010; Qublan 2006; Rizk 1990). The data for Firouzabadi 2010 were not usable, as due to inconsistent reporting in the review it was unclear which data applied to which study group.

Two of three studies reported the number of follicles recruited (Qublan 2006; Rizk 1990).

All three included studies reported on the number of oocytes collected (Firouzabadi 2010; Qublan 2006; Rizk 1990).

Two of three studies reported the cancellation rates per cycle (Firouzabadi 2010; Qublan 2006). The data for Firouzabadi 2010 were not usable, as due to inconsistent reporting in the review it was unclear which data applied to which study group.

Excluded studies

Six studies were excluded from the analysis. For details see the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Three of these studies were retrospective studies (Fiszbajn 2000; Gün Eryılmaz 2012; Kumbak 2009), one was a literature review (Legendre 2014), and one was an observational study (Levi 2003). One study (Feldberg 1988) investigated ovarian cysts that developed during ovulation induction.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

One study (Qublan 2006) used a table of random numbers available in a standard statistics textbook for selection of participants, however the number allocated to each group was unequal (76 versus 46) suggesting that the reliability of the randomization method was questionable. The remaining two studies did not describe the sequence generation method used (Firouzabadi 2010; Rizk 1990). Thus all studies were rated as at unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Allocation concealment was inadequately described in each of the three studies and therefore they were rated as having an unclear risk of bias for this domain. The authors were contacted for clarification, however further information was not forthcoming.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention it was not possible to perform double blinded trials.

All three included studies (Firouzabadi 2010; Qublan 2006; Rizk 1990) were rated as at low risk of detection and performance bias; although neither personnel nor study participants were blinded, we did not consider that blinding was likely to influence the findings for the primary outcome of live birth.

Lack of blinding was likely to influence reporting of adverse events, but these were not reported by any of the three studies.

Incomplete outcome data

One included study analyzed all women who were randomized and we judged it to be at low risk of attrition bias (Firouzabadi 2010). It was unclear whether all women who were randomized were analyzed in the other two studies (Qublan 2006; Rizk 1990) so we judged them at unclear risk of this bias.

Selective reporting

Protocols were not available for any of the three included studies (Firouzabadi 2010; Qublan 2006; Rizk 1990), therefore the risk of reporting bias was unclear. Trial authors were contacted for further information regarding their protocols but no further information was made available. Among these studies, two (Firouzabadi 2010; Qublan 2006) reported outcomes that were not clearly pre‐stated in the methods section. None of the studies reported live birth or adverse effects.

In summary, we judged the three included studies as having unclear risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

No other potential sources of bias were detected in two of the studies. Inconsistent reporting in the published paper of Firouzabadi 2010 meant that for some outcomes data were not usable. Therefore this study was rated as at unclear risk of other potential bias associated with poor reporting.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

1. Cyst aspiration versus conservative management

Primary outcomes

1.1 Live birth rate per woman randomized

No included study reported on this outcome.

1.2 Adverse events

No included study reported on this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

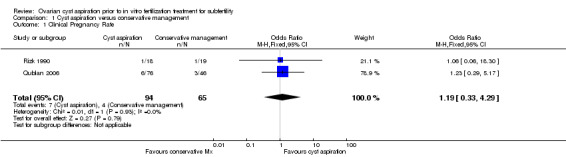

1.3 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman randomized

All three included studies (Firouzabadi 2010; Qublan 2006; Rizk 1990) reported on the clinical pregnancy rate, but the data for Firouzabadi 2010 were unusable, as noted above. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was any difference between the groups (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.33 to 4.29, 159 participants, I2 = 0%, very low quality evidence) (Analysis 1.1,Figure 4). This suggested that if the clinical pregnancy rate in women with conservative management was assumed to be 6%, the chance following cyst aspiration would be between 2% and 22%.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cyst aspiration versus conservative management, Outcome 1 Clinical Pregnancy Rate.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Cyst aspiration versus conservative management, outcome: 1.1 NEW Clinical Pregnancy Rate.

1.4 Number of follicles recruited per woman randomized

See Analysis 1.2, Figure 5.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cyst aspiration versus conservative management, Outcome 2 Number of Follicles Recruited.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Cyst aspiration versus conservative management, outcome: 1.2 Number of Follicles Recruited.

Two studies (Qublan 2006; Rizk 1990) reported the mean number of follicles recruited and no clear evidence of a difference was seen between the groups (MD 0.55, 95% CI ‐0.48 to 1.59, 159 participants, I2 = 0%, very low quality evidence).

1.5 Number of oocytes collected per woman randomized

All three included studies (Firouzabadi 2010; Qublan 2006; Rizk 1990) reported on the mean number of oocytes collected and no clear evidence of a difference was seen between the groups (OR 0.41, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.85, 339 participants, I2 = 0%, low quality evidence) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cyst aspiration versus conservative management, Outcome 3 Number of Oocytes Collected.

1.6 Cancellation rate per woman

Two studies (Firouzabadi 2010; Qublan 2006) reported the cancellation rate, but the data for Firouzabadi 2010 were unusable, as noted above. As Qublan 2006 only included one cycle, the cancellation rate per cycle equated to the cancellation rate per woman. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between the groups (OR 0.99, 0.42 to 2.33, one RCT, 302 women,very low quality evidence). (Analysis 1.4)

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cyst aspiration versus conservative management, Outcome 4 Cancellation rate.

Sensitivity analyses

No sensitivity analyses were performed as neither primary outcome (live birth rate, adverse events) was reported in the included studies.

Discussion

Summary of main results

See Table 1.

This review compared the IVF outcomes of functional ovarian cyst aspiration versus conservative management in subfertile women in whom functional ovarian cysts of greater than 20 mm were present. It was difficult to draw any conclusions about the impact of cyst aspiration compared to conservative management.

None of the three RCTs reported either live birth or adverse events, which were the primary outcomes for this review.

There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between the groups in the clinical pregnancy rate, total number of follicles recruited, or number of oocytes collected.

Two of the three included studies (Firouzabadi 2010; Qublan 2006) reported a cancellation rate per cycle that exceeded the expected rate of up to 10% that is seen in clinical practice currently (Al‐Inany 2011; CDC 2009). Qublan 2006 reported a cancellation rate of 23.7% for the cyst aspiration group and 23.9% for the conservatively managed group. Firouzabadi 2010 reported a cancellation rate of 2.2% and 14.9% but did not make it clear which rate applied to which group.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In the three included trials we noted the following.

Different definitions of functional ovarian cysts were used in each study. Rizk 1990 defined an ovarian cyst as a unilocular or bilocular sonolucent cystic structure with mean diameters between 20 mm and 60 mm. Firouzabadi 2010 defined an ovarian cyst as an ovarian structure with sonolucent thin walls > 25 mm in diameter. Qublan 2006 defined an ovarian cyst as a thin‐walled intraovarian sonolucent structure with a mean diameter of ≥ 15 mm and E2 levels of ≥ 50ρg/ml; the mean diameter of cysts in the participants in this study was 21 to 22 mm (SD 6).

In addition to investigating the effect of unilateral ovarian cysts on IVF outcome, Qublan 2006 presented data on the cycle characteristics and IVF outcome of women who developed bilateral functional ovarian cysts. They found that women with bilateral ovarian cysts had a significantly higher E2 level and a higher proportion of poor quality embryos (P < 0.05) compared to those with a unilateral functional ovarian cyst. Moreover, the number of follicles > 14 mm, number of oocytes retrieved, and number of day 2 embryos were significantly lower compared with the unilateral cyst group. Additionally, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of cancellation rate, number of embryos transferred, fertilization, pregnancy and abortion rates.

A long luteal phase pituitary down‐regulation cycle with a GnRHa is still the standard form of ovarian down‐regulation performed worldwide, however the GnRH antagonist approach to prevent an endogenous LH surge is now increasingly used in many IVF units. The three included trials utilized a standardized pituitary down‐regulation protocol, namely long luteal pituitary down‐regulation using GnRHa.

Two of the three studies (Firouzabadi 2010; Rizk 1990) did not provide details on the cause of infertility for their patients undergoing IVF, so these results should be applied with caution to the greater IVF population.

Duration of IVF treatment until completion of treatment, live birth rate, and discontinuation of IVF treatment were not reported.

The overall number of women treated in the three trials was small (339), therefore the results from this review should be interpreted with caution when incorporating the results into clinical practice.

One of the studies (Rizk 1990) is 23 years old and the methods utilized in modern IVF practices have changed substantially. Some of these changes include alterations in the culture medium used, demographic changes in patients seeking fertility treatment, and differing IVF protocols. Applying the results of this review should be interpreted with caution.

Unequal randomization was seen in the study by Qublan 2006. The reason for this is not clear and this is a potential source of bias. The authors were contacted for clarification however further information did not become available.

Clinical heterogeneity exists between the trials, mainly with respect to differing inclusion criteria, slightly different IVF protocols, and differing definitions of an ovarian cyst. Despite this, the authors felt that the derived data were applicable to those women currently undergoing IVF and that the subsequent meta‐analysis was meaningful.

Heterogeneity exists between the included studies as the study by Rizk 1990 had no cycles cancelled prior to oocyte retrieval. Qublan 2006 had a cycle cancellation rate per cycle of 23.7% in the aspirated group and 23.9% in the non‐aspirated group due to inadequate response to ovarian stimulation. Firouzabadi 2010 had a cycle cancellation rate per cycle of 2.2% and 14.9% (but did not make it clear which rate applied to which group)

The cancellation rates reported in the studies by Firouzabadi 2010 and Qublan 2006 were higher than the expected rate of 10% (Al‐Inany 2011). This may be attributed to the age of the data and different healthcare settings. In a setting where the patient is required to purchase all medications used and pay for all theatre costs, cycles may be cancelled if the numbers of follicles are low. In these instances the cancellation rate reported may be higher than what would usually be expected. Applying the results of this review should therefore be interpreted with caution.

The pregnancy rates recorded in the studies would be considered low by today's standards, hence the current applicability of these studies may be questioned.

Quality of the evidence

No evidence was available for live birth, as this outcome was not reported by the included studies.

The overall quality of evidence for clinical pregnancy rate, number of follicles recruited, and number of oocytes collected was low or very low. Limitations included poor reporting of study methods, as none of the studies adequately described their methods of randomization and allocation concealment. Moreover, some of the data reported by Firouzabadi 2010 were unusable due to inconsistency. Findings were imprecise, as the total number of events was low and confidence intervals were wide.

Findings were consistent across all studies despite differences in the definition of ovarian cyst and other methodological differences between the studies.

See Figure 3 for information regarding the individual studies.

Potential biases in the review process

We are unaware of any potential biases in the review process that were likely to have influenced our findings. However, a funnel plot was not constructed as the number of studies was small. We were therefore unable to assess the risk of publication bias. Moreover, planned sensitivity analyses were not performed due to lack of data.

The absence of cycle cancellation as an outcome was recognised as a methodological weakness. As a result, we included cycle cancellation rate per cycle as a secondary outcome.

We feel confident that all relevant studies have been included as the search terms used were broadened varied, and resulted in a comprehensive literature search. The literature search was repeated in April 2014 to capture additional studies published since the initial literature search (April 2013).

We were unable to contact lead authors in the field. One plausible source of bias would be the lack of response from the original trialists when asked to provide additional data.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

No other reviews were identified.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence to determine whether drainage of functional ovarian cysts prior to COH influences live birth rate, clinical pregnancy rate, the number of follicles recruited, or oocytes collected in women with a functional ovarian cyst. The findings of this review do not provide supportive evidence for this approach, particularly in view of the requirement for anaesthesia, extra cost, psychological stress and risk of surgical complications.

Implications for research.

This review highlights the need for well powered, well designed randomized controlled trials to further evaluate the role of cyst aspiration in women undergoing IVF treatment. Future trials need to be rigorous in design and delivery and with subsequent reporting to include high quality descriptions of all aspects of methodology to enable appraisal and interpretation of results. Current evidence lacks data on live birth rates and adverse events related to aspiration of ovarian cysts. Research conducted in the future should report these outcomes to maximise the care of women undergoing IVF in whom ovarian cysts are detected.

Feedback

Feedback on discrepancy in data for Firouzabadi 2010

Summary

Dr Spath pointed out that there is a discrepancy in one of the reviewed original papers (Firouzabadi 2010): the Results section states different findings from the numbers in the Table (with an opposite direction of effect). This applies to the outcomes of clinical pregnancy and cancellation rate.

Reply

The review authors agree that there is a discrepancy here. As we have been unable to contact the authors of the primary study, we have removed the data for this study from the analyses of clinical pregnancy and cancellation rate.

Contributors

Dr. M.A. Spath, Resident, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre

Study authors

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 August 2017 | Feedback has been incorporated | Review amended in response to feedback pointing out inconsistency in one of the included study publications (Firouzabadi 2010). Data from this study have been removed from the analyses for clinical pregnancy and cancellation rate. The conclusions of the review have not changed. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2006 Review first published: Issue 12, 2014

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 20 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 14 April 2008 | Amended | converted to new review format |

| 25 December 2005 | New citation required and major changes | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the peer reviewers and the staff at the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertlity Group (MDSG), in particular Helen Nagels and Marion Showell for their contribution to the review.

We acknowledge the contributions of Jason Chin and Angela Beard to the early development of this full review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MDSG search strategy

<Inception to 19 May 2014>

Keywords CONTAINS "ovarian cyst" or "Ovarian Cysts" or "ovarian cystectomy" or "cyst drainage" or "cyst puncture" or "cyst recurrence" or "cyst resolution" or "cystectomy" or "excision" or "Aspiration" or Title CONTAINS "ovarian cyst" or "Ovarian Cysts" or "ovarian cystectomy" or "cyst drainage" or "cyst puncture" or "cyst recurrence" or "cyst resolution" or "cystectomy" or "excision" or "Aspiration" AND Keywords CONTAINS "Pretreatment", "ivf" or "icsi" or "in‐vitro fertilisation " or "in vitro fertilization" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection techniques" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycle" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection" or "Intracyst" or "*Ovulation Induction" or "ART" or "assisted reproduction" or "assisted reproduction techniques" or "COH" or "controlled ovarian hyperstimulation" or "controlled ovarian stimulation" or Title CONTAINS"Pretreatment", "ivf" or "icsi" or "in‐vitro fertilisation " or "in vitro fertilization" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection techniques" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycle" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection" or "Intracyst" or "*Ovulation Induction" or "ART" or "assisted reproduction" or "assisted reproduction techniques" or "COH" or "controlled ovarian hyperstimulation" or "controlled ovarian stimulation"

Appendix 2. EBM Reviews ‐ Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials search strategy

Database: EBM Reviews ‐ Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

<Inception ‐ 19 May 2014>

1 exp fertilization in vitro/ or exp sperm injections, intracytoplasmic/ (1447)

2 in vitro fertilization.tw. (1195)

3 in vitro fertilisation.tw. (119)

4 intracytoplasmic sperm injection$.tw. (403)

5 (ivf or icsi).tw. (2145)

6 ovulation induction.tw. (409)

7 ART.tw. (892)

8 assisted reproductive technolog$.tw. (111)

9 controlled ovarian hyperstimulation.tw. (246)

10 ovar$ stimulat$.tw. (679)

11 or/1‐10 (4275)

12 (cyst$ adj5 aspirat$).tw. (44)

13 (cyst$ adj5 remov$).tw. (44)

14 (cyst$ adj5 reduc$).tw. (193)

15 (cyst$ adj5 resect$).tw. (43)

16 (cyst$ adj5 excis$).tw. (21)

17 (ovar$ cyst adj5 surg$).tw. (2)

18 (cyst$ adj3 tumour$).tw. (30)

19 (cyst$ adj3 tumor$).tw. (38)

20 (corpus luteum adj5 cyst$).tw. (1)

21 cystectom$.tw. (255)

22 exp Cystectomy/ (127)

23 or/12‐22 (624)

24 11 and 23 (14)

Appendix 3. MEDLINE (R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE (R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE (R) search strategy

<Inception ‐ 19 May 2014>

1 exp fertilization in vitro/ or exp sperm injections, intracytoplasmic/ (25320)

2 in vitro fertilization.tw. (13890)

3 in vitro fertilisation.tw. (1173)

4 intracytoplasmic sperm injection$.tw. (4294)

5 (ivf or icsi).tw. (16395)

6 ovulation induction.tw. (2630)

7 ART.tw. (37082)

8 assisted reproductive technolog$.tw. (3048)

9 controlled ovarian hyperstimulation.tw. (1132)

10 ovar$ stimulat$.tw. (3445)

11 or/1‐10 (72339)

12 (cyst$ adj5 aspirat$).tw. (2021)

13 (cyst$ adj5 remov$).tw. (3407)

14 (cyst$ adj5 reduc$).tw. (4709)

15 (cyst$ adj5 resect$).tw. (3017)

16 (cyst$ adj5 excis$).tw. (2873)

17 (ovar$ cyst adj5 surg$).tw. (66)

18 (cyst$ adj3 tumour$).tw. (1375)

19 (cyst$ adj3 tumor$).tw. (6119)

20 (corpus luteum adj5 cyst$).tw. (188)

21 cystectom$.tw. (8405)

22 exp Cystectomy/ (4619)

23 or/12‐22 (30483)

24 randomized controlled trial.pt. (321955)

25 controlled clinical trial.pt. (83688)

26 randomized.ab. (237538)

27 placebo.tw. (137505)

28 clinical trials as topic.sh. (158334)

29 randomly.ab. (174662)

30 trial.ti. (101611)

31 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (52521)

32 or/24‐31 (788443)

33 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (3681302)

34 32 not 33 (727668)

35 11 and 23 and 34 (15)

Appendix 4. EMBASE search strategy

<Inception ‐ 19 May 2014>

1 exp fertilization in vitro/ (36636)

2 exp intracytoplasmic sperm injection/ (11191)

3 in vitro fertilization.tw. (17635)

4 in vitro fertilisation.tw. (1780)

5 intracytoplasmic sperm injection$.tw. (5788)

6 (ivf or icsi).tw. (25712)

7 ovulation induction.tw. (3640)

8 ART.tw. (53680)

9 assisted reproductive technolog$.tw. (4693)

10 controlled ovarian hyperstimulation.tw. (1678)

11 ovar$ stimulat$.tw. (5351)

12 or/1‐11 (105538)

13 (cyst$ adj5 aspirat$).tw. (2570)

14 (cyst$ adj5 remov$).tw. (4378)

15 (cyst$ adj5 reduc$).tw. (5654)

16 (cyst$ adj5 resect$).tw. (4092)

17 (cyst$ adj5 excis$).tw. (3667)

18 (ovar$ cyst adj5 surg$).tw. (104)

19 (cyst$ adj3 tumour$).tw. (1748)

20 (cyst$ adj3 tumor$).tw. (7798)

21 (corpus luteum adj5 cyst$).tw. (213)

22 cystectom$.tw. (12229)

23 exp CYSTECTOMY/ (13816)

24 or/13‐23 (42988)

25 12 and 24 (337)

26 Clinical Trial/ (876945)

27 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (340667)

28 exp randomization/ (61219)

29 Single Blind Procedure/ (17264)

30 Double Blind Procedure/ (114133)

31 Crossover Procedure/ (36683)

32 Placebo/ (216470)

33 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (85761)

34 Rct.tw. (11270)

35 random allocation.tw. (1229)

36 randomly allocated.tw. (18579)

37 allocated randomly.tw. (1876)

38 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (717)

39 Single blind$.tw. (13192)

40 Double blind$.tw. (135581)

41 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (310)

42 placebo$.tw. (187354)

43 prospective study/ (230661)

44 or/26‐43 (1321345)

45 case study/ (19314)

46 case report.tw. (242133)

47 abstract report/ or letter/ (865150)

48 or/45‐47 (1121555)

49 44 not 48 (1285138)

50 25 and 49 (40)

51 (2012$ or 2013$).em. (1665341)

52 50 and 51 (4)

Appendix 5. PsycINFO (Ovid) search strategy

<Inception ‐ 19 May 2014>

1 exp Reproductive Technology/ (1129)

2 in vitro fertilization.tw. (418)

3 in vitro fertilisation.tw. (57)

4 intracytoplasmic sperm injection$.tw. (31)

5 (ivf or icsi).tw. (326)

6 ovulation induction.tw. (10)

7 ART.tw. (26443)

8 controlled ovarian hyperstimulation.tw. (1)

9 ovar$ stimulat$.tw. (16)

10 assisted reproductive techn$.tw. (242)

11 or/1‐10 (27693)

12 (cyst$ adj5 aspirat$).tw. (3)

13 (cyst$ adj5 remov$).tw. (47)

14 (cyst$ adj5 reduc$).tw. (71)

15 (cyst$ adj5 resect$).tw. (9)

16 (cyst$ adj5 excis$).tw. (10)

17 (ovar$ cyst adj5 surg$).tw. (0)

18 (cyst$ adj3 tumour$).tw. (4)

19 (cyst$ adj3 tumor$).tw. (27)

20 (corpus luteum adj5 cyst$).tw. (0)

21 cystectom$.tw. (13)

22 or/12‐21 (176)

23 11 and 22 (2)

Appendix 6. CINAHL (EBSCO) search strategy

<Inception ‐ 19 May 2014>

| # | Query | Results |

| S15 | S8 and S14 | 36 |

| S14 | S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 | 7,722 |

| S13 | TX cyst* drain* | 74 |

| S12 | TX cyst* excis* | 211 |

| S11 | (MH "Aspiration") OR TX aspiration | 6,746 |

| S10 | TX cyst* aspirat* | 143 |

| S9 | (MH "Cystectomy") OR TX "cystectomy" | 715 |

| S8 | S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 | 5,338 |

| S7 | TX assisted reproductive technolog* | 600 |

| S6 | (MM "Embryo Transfer") | 200 |

| S5 | (MH "Reproduction Techniques+") | 4,907 |

| S4 | (MH "Ovulation Induction") OR TX "ovulation induction" | 430 |

| S3 | TX icsi | 214 |

| S2 | TX "intracytoplasmic sperm injection" | 209 |

| S1 | TX ivf OR (MM "Fertilization in Vitro") | 1,707 |

Appendix 7. PubMed

<Inception to 19 May 2014>

Keywords included:

(("ovarian cysts"[MeSH Terms] OR ("ovarian"[All Fields] AND "cysts"[All Fields]) OR "ovarian cysts"[All Fields] OR ("ovarian"[All Fields] AND "cyst"[All Fields]) OR "ovarian cyst"[All Fields]) AND ("J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf"[Journal] OR "ivf"[All Fields])) OR (("sperm injections, intracytoplasmic"[MeSH Terms] OR ("sperm"[All Fields] AND "injections"[All Fields] AND "intracytoplasmic"[All Fields]) OR "intracytoplasmic sperm injections"[All Fields] OR "icsi"[All Fields]) AND aspiration[All Fields]) (13)

Appendix 8. Clinicaltrials.gov and WHO portal for ongoing trials search strategy

<Inception ‐ 24 April 2013>

Keywords included:

Ovarian cyst and IVF (36) ‐ Clinicaltrials.gov

Ovarian cyst and IVF (38) ‐ WHO

Appendix 9. Google Scholar search strategy

<inception ‐ 14 August 2014

Keywords included:

"ovarian cyst*" AND aspiration AND (IVF OR "controlled ovarian hyperstimulation")

Appendix 10. PubMed clinical trials

<inception ‐ 14 August 2014

Keywords included:

(("ovarian cyst"[All Fields] OR "ovarian cysts"[All Fields]) AND aspiration[All Fields]) AND (("J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf"[Journal] OR "ivf"[All Fields]) OR "controlled ovarian hyperstimulation"[All Fields])

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Cyst aspiration versus conservative management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Clinical Pregnancy Rate | 2 | 159 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.33, 4.29] |

| 2 Number of Follicles Recruited | 2 | 159 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.55 [‐0.48, 1.59] |

| 3 Number of Oocytes Collected | 3 | 339 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.41 [‐0.04, 0.85] |

| 4 Cancellation rate | 1 | 122 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.42, 2.33] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Firouzabadi 2010.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Method of allocation not mentioned |

|

| Participants | Research and Clinical Center for Infertility, Shahid Sedughi; University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Yazd, Iran 180 Infertile women aged 19 to 45 years undergoing IVF therapy with a long protocol (HMG, GnRHa) with functional ovarian cysts of > 25 mm Randomly divided into two groups Clinical and treatment characteristics of study groups Cyst aspiration group:

No intervention group:

|

|

| Interventions | Two interventions compared: 1. Cyst aspiration (n = 90) 2. Expectant management (n = 90) For both groups on day 21 of their menstrual cycle, stimulation was implemented first with GnRHa and then with HMG (human menopausal gonadotrophin). On the second day of their menstrual cycle and prior to HMG stimulation FSH, LH and E2 (estradiol) were measured, and on the eight day of the cycle following the stimulation, a transvaginal ultrasound was performed. In cyst aspiration group the cysts were aspirated and ultrasonography was carried out every 3 to 4 days. If at least three follicles with a diameter more than 17 mm were observed 10,000 units of HCG (human chorionic gonadotrophin) would be administered in a single dose. In the no intervention group, following the cyst diagnosis, the conservative treatment was continued and routine ultrasonography was performed. Again if three follicles with a diameter of more than 17 mm were observed a single dose of 10,000 units of HCG was administered. E2 hormone levels were measured for all the women on the same day as HCG administration. In both groups 36 hours after HCG administration, oocyte aspiration was performed and the fetus was transferred 24 to 48 hours later. The pregnancy detection was based chemically on the positive Beta HCG (> 10 IU) and clinically on the observation of a pregnancy sac on ultrasonography at the gestational age of 6 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Quality and quantity of oocyte retrieved Number of embryos transferred Grade of embryos Cancellation rate Clinical pregnancy rate |

|

| Notes | Findings for some outcomes are inconsistent in the study publication ‐ results differ between tables and text and between different parts of the text. As attempts to contact the study authors were unsuccessful, for outcomes where the findings were inconsistently reported the data were omitted from this review. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Does not state method of randomization |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of allocation was unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Neither participants or personnel were blinded but the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by any lack of blinding |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by any lack of blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants included in analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Inconsistent reporting of outcome data in the published paper. |

Qublan 2006.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Allocation performed using a selection from table of random numbers available in a standard statistics textbook Performed between January 2002 and December 2003 |

|

| Participants | Infertility and IVF Center, King Hussein Medical Center, Amman and infertility and IVF Center, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan 1317 women undergoing IVF treatment cycle using a standardized pituitary down‐regulation protocol (long luteal pituitary down‐regulation using a GnRH analogue, triptorelin), that commenced on day 21 of the menstrual cycle were observed for the development of ovarian cysts. Women with a functional ovarian cyst, defined as a thin walled intraovarian sonolucent structure with a mean diameter of > 15 mm and E2 levels of > 50 pg/ml, were included. Those with non‐functional ovarian cysts were excluded. 122 (9.26%) developed ovarian cysts and were randomized to cyst aspiration or the no intervention group. Of those women randomized to the cyst aspiration group (n = 76) 59 women completed treatment and 17 were cancelled due to poor response; defined as fewer than three follicles of ≤ 14 mm observed on days 13 to 16 of stimulation. Of those women randomized to no intervention (n = 76) 34 women completed treatment and 12 were cancelled due to poor response. Demographic data of women with ovarian cysts (n = 122)

‐ Tubal 15.1% ‐ Anovulation 18.3% ‐ Male factor 37.6% ‐ Endometriosis 27.7% ‐ Unexplained 4.3% The mean diameter of cysts in the participants in this study was 21 to 22 mm (SD 6). |

|

| Interventions | Cyst aspiration under local anaesthesia was performed on the day of cyst diagnosis. Ovarian stimulation with HMG was started in all women on the third day of bleeding. Transvaginal ultrasound follow up for follicular growth was commenced on day 8 of ovarian stimulation and repeated every 3 to 4 days thereafter. When at least three follicles reached a diameter of 17 mm, a single dose of 10,000 units of HCG was administered. After 36 hours, transvaginal‐guided oocyte retrieval was performed under general anaesthetic. Fertilization was considered successful after noting the presence of two pronuclei and second polar body 20 to 24 hours after conventional IVF by adding ˜105 motile spermatozoa/ml to droplets of medium each containing one oocyte or after ICSI. Clinical pregnancy was confirmed by demonstrating an intrauterine fetal pole with a positive fetal heartbeat. Two interventions compared: 1. Cyst aspiration (n = 76) 2. Expectant management (n = 46) |

|

| Outcomes | Number of follicles recruited Number of oocytes retrieved Grade of embryos (Coskun et al 1998) Fertlization rates Cancellation rates Pregnancy rates Implanatation rates |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation performed using a selection from table of random numbers available in a standard statistics textbook but numbers allocated to each group very uneven |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of allocation was unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The outcomes are not likely to be influenced by any lack of blinding |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by any lack of blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants included in analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias were detected |

Rizk 1990.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Method and date of allocation not mentioned |

|

| Participants | Bourn Hallan Medical Centre and Kings College Hospital School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, United Kingdom Women undergoing IVF treatment with a unilocular or bilocular, sonolucent ovarian cyst > 20 and < 60 mm identified before ovarian stimulation 14 women had a unilateral ovarian cyst detected at the time of the baseline US scan on the second day of their menstrual cycle; prior to GnRHa down‐regulation (Group A) and 23 women were found to have a cyst after GnRHa down‐regulation (Group B). Group A women had not received any exogenous gonadotropin stimulation for at least 12 weeks preceding their IVF cycle. Women in each group randomly divided into two subgroups; one subgroup had the ovarian cyst aspiration, whereas the other did not (expectant management). Those women who underwent cyst aspiration (both group A and Group B) were combined for analysis as both women had ovarian cysts detected prior to ovarian stimulation as per the inclusion criteria. Those women who had expectant management of their ovarian cyst (both Group A and Group B) were combined for analysis as both women had ovarian cysts detected prior to ovarian stimulation as per the inclusion criteria. Cyst aspiration group:

Expectant management group

|

|

| Interventions | Two interventions compared: 1. Cyst aspiration (n = 18) 2. Expectant management (n = 19) Cyst aspiration was performed under transvaginal US guidance using a 20‐guage ovarian cyst aspiration needle. In all women, ovarian stimulation was then commenced using a combination of clomiphene citrate 100mg/d from day 2 to day 6 of the cycle and hMG, 225 IU intramuscularly IM daily from day 4. Follicular response was monitored by ultrasonic measurements of follicle size and levels of urinary estrogens or serum estradiol. HCG, 5000 units was administered when three follicles were > 14 mm, the mean diameter of the leading follicle > 17 mm and urinary estrogens exceeded 300 μg/d or serum estradiol 3000 ρmo/l. Transvaginal ultrasound guided oocyte retrieval was performed 35 hours after the injection of hCG. |

|

| Outcomes | Number of follicles recruited Number of oocytes collected Number of oocytes fertilised Clinical pregnancy rate |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of sequence generation was unclear |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of allocation was unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The outcomes are not likely to be influenced by any lack of blinding. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by any lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants included in analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias were detected |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Feldberg 1988 | Retrospective study not a randomised control trial and ovarian cysts formed during ovulation induction |

| Fiszbajn 2000 | Retrospective study, not a randomised controlled trial |

| Gün Eryılmaz 2012 | Retrospective study, not a randomised controlled trial |

| Kumbak 2009 | Retrospective study, not a randomised control trial |

| Legendre 2014 | Literature review, not a randomised controlled trial |

| Levi 2003 | Observational study, not a randomised controlled trial |

Differences between protocol and review

Adverse events, including infection, bleeding, injury to surrounding structures, need for further surgery including oophorectomy, anaesthetic complications, and costs of both the procedure itself and any subsequent complications, have been added as a primary outcome.

Cancellation rate per cycle has been added as a secondary outcome between publication of the review protocol and the review. We planned to report this outcome in "Other data" rather than in a forest plot. However, as the relevant study only included one cycle, we were able to report this as "per woman" data.

An additional author has been added between the publication of the review protocol and the review, and two authors moved to 'Acknowledgements'.

We have revised the methods section of the review to reflect current Cochrane standards for conducting and reporting reviews.

The effect estimate used in the final review was the Mantel‐Haenszel OR with 95% CI. In the protocol it was documented that the Peto OR would be used, and this was altered to the Mantel‐Haenszel OR prior to final publication.

Contributions of authors

JC, AB and RH jointly developed the protocol.

For the full review, RM, JC and AB conducted a preliminary literature search and reviewed the available literature. RM, JC and AB were responsible for screening the studies. RM collected the data. RM, JM and RH assessed the quality of the studies. Disagreements were resolved by a meeting of review authors and by consulting an external author. JM developed the summary of findings table, supplied methodological advice and fully edited the draft review.

RM, JM and RH wrote the review. All authors were involved in the review of the final manuscript. RH was the final consultant for the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

None, Other.

External sources

None, Other.

Declarations of interest

RM and JM have no conflicts of interest to disclose. RH is a shareholder in Western IVF and is a member of the medical advisory boards of the pharmaceutical companies Merck‐Serono and MSD, which supply drugs used in IVF cycles.

Edited (no change to conclusions), comment added to review

References

References to studies included in this review

Firouzabadi 2010 {published data only}

- Firouzabadi R, Sekhavat L, Javedani M. The effect of ovarian cyst aspiration on IVF treatment with GnRH. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2010;281:545‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Qublan 2006 {published data only}

- Qublan H, Amarin Z, Tahat Y, Smadi A, Kilani M. Ovarian cyst formation following GnRH agonist administration in IVF cycles : incidence and impact. Human Reproduction 2006;3:640‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rizk 1990 {published data only}

- Rizk B, Tan SL, Kingsland C, Steer C, Mason BA, Campbell S. Ovarian cyst aspiration and the outcome of in vitro fertilization. Fertility and Sterility 1990;54(4):661‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Feldberg 1988 {published data only}

- Feldbert D, Ashkenazi J, Dicker D, Yeshaya A, Vohovitch I, Goldman JA. Ovarian cyst aspiration during in vitro fertilization/embryo transfer. Journal of In Vitro Fertilization and Embryo Transfer 1988;5:372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fiszbajn 2000 {published data only}

- Fiszbajn GE, Lipowicz RG, Elberger L, Grabia A, Dapier SD, Brugo‐Olmedo SP. Conservative management versus aspiration of functional ovarian cyst before ovulation stimulation for assisted reproduction. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 2000;17:206‐63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gün Eryılmaz 2012 {published data only}

- Gün Eryılmaz O, Sarıkaya E, Nur Aksakal F, Hamdemir S, Doğan M, Mollamahmutoğlu L. Ovarian cyst formation following gonadotropin‐releasing hormone‐agonist administration decreases the oocyte quality in IVF cycles. Balkan Medical Journal 2012;29:197‐200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kumbak 2009 {published data only}

- Kumbak B, Kahraman S. Management of prestimulation ovarian cysts during assisted reproductive treatments: impact of aspiration on the outcome. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2008;279(6):875‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Legendre 2014 {published data only}

- Legendre G, Catala L, Morinière C, Lacoeuille C, Boussion F, Sentilhes L, Descamps P. Relationship between ovarian cysts and infertility: what surgery and when?. Fertility and Sterility 2014;101(3):608‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Levi 2003 {published data only}

- Levi R, Özçakir HT, S Adakan, Tavmergen Göker EN, Tavmergen E. Effect of ovarian cysts detected on the beginning day ofovulation induction to the success rates in ART cycles. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2003;29(4):257‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Al‐Inany 2011

- Al‐Inany HG, Youssef MAFM, Aboulghar M, Broekmans FJ, Sterrenburg MD, Smit JG, Abou‐Setta AM. Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonists for assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 5. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001750.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biljan 1998

- Biljan MM, Mahutte NG, Dean N, Hemmings R, Bissonnette F, Tan SL. Effects of pretreatment with a oral contraceptive on the time required to achieve pituitary suppression with gonadotropin releasing hormone analogues and on subsequent implantation and pregnancy rate. Fertility and Sterility 1998;70(6):1063‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CDC 2009

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. 2009 Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2011.

Cochrane 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Depalo 2012

- Depalo R, Jayakrishan K, Garruti G, Totaro I, Panzarino M, Giorgino F, Selvaggi LE. GnRH agonist versus GnRH antagonist in in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF/ET). Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2012;10:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Greenebaum 1992

- Greenebaum E, Mayer JR, Stangel JJ, Hughes P. Aspiration cytology of ovarian cysts in in vitro fertilization patients. Acta Cytologica 1992;1(36):11‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hornstein 1989

- Hornstein MD, Barbieri RL, Ravnikar VA, McShane PM. The effects of baseline ovarian cysts on the clinical response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in an in vitro fertilization program. Fertility and Sterility 1989;3(52):437‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jenkins 1993

- Jenkins JM, Anthony FW, Wood P, Rushen D, Masson GM, Thomas E. The development of functional ovarian cysts during pituitary down‐regulation. Human Reproduction 1993;10(8):1623‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jenkins 1996

- Jenkins JM. The influence, development and management of functional ovarian cysts during IVF cycles. Journal of the British Fertility Society 1996;1(2):132‐6. [Google Scholar]

Keltz 1995

- Keltz MD, Jones EE, Duleba AJ, Polez T, Kennedy K, Olive D. Baseline cyst formation after luteal phase gonadotropin‐releasing hormone agonist administration is linked to poor in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertility and Sterility 1995;64(3):568‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Neill 2001

- O’Neill MJ, Rafferty EA, Lee SI, Arellano RS, Gervais DA, Hahn PF, et al. Transvaginal interventional procedures: aspiration, biopsy, and catheter drainage. Radiographics 2001;21(3):657‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Penzias 1992

- Penzias AS, Jones EE, Seifer DB, Grifo JA, Thatcher SS, DeCherney AH. Baseline ovarian cysts do not affect clinical response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for in vitro fertilization. Fertility and Sterility 1992;5(57):1017‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ron‐El 1989

- Ron‐El R, Herman A, Golan A, Raziel A, Soffer Y, Caspi E. Follicle cyst formation following long‐acting gonadotropin‐releasing hormone analog administration. Fertility and Sterility 1989;52(6):1063‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Segal 1999

- Segal S, Shifren JL, Isaacson KB, Leykin L, Chang Y, Pal L, Toth TL. Effect of a baseline ovarian cyst on the outcome of in vitro fertilization‐embryo transfer. Fertility and Sterility 1999;2(71):274‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Speroff 2011

- Fritz MA, Speroff L. Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. 8. USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Zeyneloglu 1998

- Zeyneloglu HB, Isik AZ, Kara S, Senoz S, Ozcan U, Gokmen O. Impact of baseline cysts at the time of administration of gonadotropin‐releasing hormone analog for in vitro fertilization. International Journal of Fertility and Women's Medicine 1998;6(43):300‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]