Abstract

Background

Neuroblastoma is a rare malignant disease and mainly affects infants and very young children. The tumours mainly develop in the adrenal medullary tissue, with an abdominal mass as the most common presentation. About 50% of patients have metastatic disease at diagnosis. The high‐risk group is characterised by metastasis and other features that increase the risk of an adverse outcome. High‐risk patients have a five‐year event‐free survival of less than 50%. Retinoic acid has been shown to inhibit growth of human neuroblastoma cells and has been considered as a potential candidate for improving the outcome of patients with high‐risk neuroblastoma. This review is an update of a previously published Cochrane Review.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of additional retinoic acid as part of a postconsolidation therapy after high‐dose chemotherapy (HDCT) followed by autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), compared to placebo retinoic acid or to no additional retinoic acid in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma (as defined by the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) classification system).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (2016, Issue 11), MEDLINE in PubMed (1946 to 24 November 2016), and Embase in Ovid (1947 to 24 November 2016). Further searches included trial registries (on 22 December 2016), conference proceedings (on 23 March 2017) and reference lists of recent reviews and relevant studies. We did not apply limits by publication year or languages.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating additional retinoic acid after HDCT followed by HSCT for people with high‐risk neuroblastoma compared to placebo retinoic acid or to no additional retinoic acid. Primary outcomes were overall survival and treatment‐related mortality. Secondary outcomes were progression‐free survival, event‐free survival, early toxicity, late toxicity, and health‐related quality of life.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

The update search did not identify any additional studies. We identified one RCT that included people with high‐risk neuroblastoma who received HDCT followed by autologous HSCT (N = 98) after a first random allocation and who received retinoic acid (13‐cis‐retinoic acid; N = 50) or no further therapy (N = 48) after a second random allocation. These 98 participants had no progressive disease after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT. There was no clear evidence of difference between the treatment groups either in overall survival (hazard ratio (HR) 0.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.46 to 1.63; one trial; P = 0.66) or in event‐free survival (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.49; one trial; P = 0.59). We calculated the HR values using the complete follow‐up period of the trial. The study also reported overall survival estimates at a fixed point in time. At the time point of five years, the survival estimate was reported to be 59% for the retinoic acid group and 41% for the no‐further‐therapy group (P value not reported). We did not identify results for treatment‐related mortality, progression‐free survival, early or late toxicity, or health‐related quality of life. We could not rule out the possible presence of selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, and other bias. We judged the evidence to be of low quality for overall survival and event‐free survival, downgraded because of study limitations and imprecision.

Authors' conclusions

We identified one RCT that evaluated additional retinoic acid as part of a postconsolidation therapy after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT versus no further therapy in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma. There was no clear evidence of a difference in overall survival and event‐free survival between the treatment alternatives. This could be the result of low power. Information on other outcomes was not available. This trial was performed in the 1990s, since when many changes in treatment and risk classification have occurred. Based on the currently available evidence, we are therefore uncertain about the effects of retinoic acid in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma. More research is needed for a definitive conclusion.

Plain language summary

Retinoic acid after intensive chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of adding retinoic acid as part of a postconsolidation therapy after intensive chemotherapy (high‐dose chemotherapy) followed by autologous (from the same person) bone marrow transplantation (haematopoietic stem cell transplantation) in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma. A consolidation therapy tries to destroy possible remnant cancer cells after a preceding therapy has achieved the elimination of detectable tumour. A postconsolidation therapy is applied after that consolidation therapy. The addition of retinoic acid was compared to the same pretreatment but placebo (inactive) retinoic acid or no addition of retinoic acid for two primary and five secondary outcomes. The primary outcomes were overall survival (participants who did not die) and treatment‐related mortality (participants who died due to complications of the intervention). Secondary outcomes were progression‐free survival (the condition did not worsen), event‐free survival (staying free of any of a particular group of events), early and late toxicity (harmful effects), and health‐related quality of life.

Background

Neuroblastoma is a rare cancerous disease and mainly affects infants and very young children. The high‐risk group is prone to spread of the disease and other characteristics that increase the risk of an adverse event. Retinoic acid stops uncontrolled cell growth in laboratory cell cultures and might reduce the return of the tumour after high‐dose chemotherapy followed by autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to 24 November 2016. We included a single randomised trial with 50 people allocated to the addition of retinoic acid after high‐dose chemotherapy followed by autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and 48 people allocated to the same treatment but without the addition of retinoic acid.

Key results

The update search did not identify any new studies. Overall survival and event‐free survival were no different between the two treatment alternatives. Other outcomes, including those concerning adverse events, were not adequately reported. Additional retinoic acid as part of a postconsolidation therapy after high‐dose chemotherapy followed by autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation may not improve survival in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma, and we lack information on its safety. More research is needed before we can draw solid conclusions.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence is based on a single study. The quality of the evidence in this single included study is low.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Retinoic acid postconsolidation therapy compared to no further treatment for high‐risk neuroblastoma patients treated with autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

| Retinoic acid postconsolidation therapy compared to no further treatment for high‐risk neuroblastoma patients treated with autologous HSCT | ||||||

| Patient or population: high‐risk neuroblastoma patients treated with autologous HSCT Settings: paediatric oncology departments Intervention: retinoic acid postconsolidation therapy Comparison: no further treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No further treatment | Retinoic acid post‐consolidation therapy | |||||

| Overall survival (reported as mortality) | 583 per 10001 | 533 per 1000 (331 to 760) | HR 0.87 (0.46 to 1.63) | 98 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | The length of follow‐up was not mentioned for the 98 participants eligible for this review |

| Treatment‐related mortality ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No adequate information on this outcome was provided |

| Progression‐free survival ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No information on this outcome was provided |

| Event‐free survival (reported as relapse, disease progression, death from any cause, or second neoplasm) | 604 per 10001 | 549 per 1000 (371 to 749) | HR 0.86 (0.50 to 1.49) | 98 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | The length of follow‐up was not mentioned for the 98 participants eligible for this review |

| Early toxicity ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No adequate information on this outcome was provided |

| Late toxicity including secondary malignancies ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No adequate information on this outcome was provided |

| Health‐related quality of life ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No information on this outcome was provided |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; HR: Hazard ratio; HSCT: haematopoietic stem cell transplantation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1The assumed risk is based on the number of events in the control group at the final time point of the survival curve presented in the included study. 2The presence of selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias and other bias was unclear, so we downgraded one level for study limitations. 3Since this is a small study and the 95% CIs include values favouring both the intervention and the control treatment we downgraded one level for imprecision.

Background

Description of the condition

Neuroblastoma is a rare malignant disease and mainly affects infants and very young children (GARD 2017). Tumours develop in the sympathetic nervous system such as adrenal medullary tissue or paraspinal ganglia, and may be localised or metastatic at diagnosis (Cole 2012). The median age at diagnosis is 17 months and the incidence rate of neuroblastoma is age‐dependent, with an incidence rate of 64 per million children in the first year of life reducing to 29 per million children in the second year of life (Goodman 2012). The incidence rate in adults is less than one per million a year, but adults have a considerably worse prognosis (Esiashvili 2007). Cohn 2009 proposed the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) classification system (see Table 2). Of 8800 people with neuroblastoma, 36.1% had high‐risk neuroblastoma. Berthold 2005 estimated that 50% of people with neuroblastoma have metastatic disease at diagnosis. Patients in the high‐risk group had a five‐year event‐free survival rate (defined as the time from diagnosis until the time of first occurrence of relapse, progression, secondary malignancy, or death, or until the time of last contact if none of these occurred) of less than 50%. Matthay 2012 addressed new approaches with targeted therapy that may improve the outcome in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma.

1. The INRG consensus pretreatment classification scheme.

| INRG stage | Age (months) | Histologic category | Grade of tumour differentiation | MYCN | 11q aberration | Ploidy | Pretreatment risk group | |

| Code | Interpretation | |||||||

| L1/L2 | – | Ganglioneuroma maturing; ganglioneuroblastoma intermixed | ‐ | – | – | – | A | Very low |

| L1 | – | Any, except ganglioneuroma or ganglioneuroblastoma | – | Not amplified | – | – | B | Very low |

| Amplified | – | – | K | High | ||||

| L2 | < 18 | Any, except ganglioneuroma or ganglioneuroblastoma | – | Not amplified | No | – | D | Low |

| Yes | – | G | Intermediate | |||||

| ≥ 18 | Ganglioneuroblastoma nodular; neuroblastoma | Differentiating | Not amplified | No | – | E | Low | |

| Yes | – | H | Intermediate | |||||

| Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated | Not amplified | – | – | H | Intermediate | |||

| – | Amplified | – | – | N | High | |||

| M | < 18 | – | – | Not amplified | – | Hyperdiploid | F | Low |

| < 12 | – | – | Not amplified | – | Diploid | I | Intermediate | |

| 12 to < 18 | – | – | Not amplified | – | Diploid | J | Intermediate | |

| < 18 | – | – | Amplified | – | – | O | High | |

| ≥ 18 | – | – | – | – | – | P | High | |

| MS | < 18 | – | – | Not amplified | No | – | C | Very low |

| Yes | – | Q | High | |||||

| Amplified | – | – | R | High | ||||

Reference: Cohn 2009.

The INRG consensus classification schema includes the criteria INRG stage, age, histologic category, grade of tumour differentiation, MYCN status, presence/absence of 11q aberrations, and tumour cell ploidy. Sixteen statistically or clinically different pretreatment groups of patients (lettered A through R), or both, were identified using these criteria. The categories were designated as very low (A, B, C), low (D, E, F), intermediate (G, H, I, J), or high (K, N, O, P, Q, R) pretreatment risk subsets.

An abdominal mass is the most common presentation of neuroblastoma. In general, neuroblastoma occurs at a single location, usually the medulla of the adrenal gland or along the paravertebral sympathetic chain. Organ‐specific symptoms may be caused by the local presence of metastases, such as eye problems associated with retrobulbar tumours, pancytopenia associated with bone marrow infiltration, abdominal distension and respiratory problems associated with liver enlargement, paralysis, and Horner syndrome associated with ganglion involvement (Berthold 2005; NCI PDQ 2017). Furthermore, there are general signs and symptoms like tiredness, weakness or pain. Some neuroblastomas regress spontaneously without therapy, while others progress with a fatal outcome despite therapy. One study of infants younger than 12 months showed that nearly half of the study population within three years of follow‐up had a spontaneous regression at diagnosis (Hero 2008). A tumour mass may be confirmed by ultrasound, X‐rays, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging. Guidelines for using imaging methods have been developed in response to the increased importance of image‐defined factors in staging and risk assessment (Brisse 2011).

The International Neuroblastoma Staging System provides the current definitions for diagnosis, the stages 1, 2A, 2B, 3, 4, and 4S shown in Table 3, and treatment response shown in Table 4 (Brodeur 1993). The INRG classification system provides the current definitions for the very low, low, intermediate, and high‐risk groups shown in Table 2 (Cohn 2009).

2. The International Neuroblastoma Staging System.

| Stage | Definition |

| 1 | Localised tumour with complete gross excision, with or without microscopic residual disease; representative ipsilateral lymph nodes negative for tumour microscopically (nodes attached to and removed with the primary tumour may be positive) |

| 2A | Localised tumour with incomplete gross excision; representative ipsilateral nonadherent lymph nodes negative for tumour microscopically |

| 2B | Localised tumour with or without complete gross excision, with ipsilateral nonadherent lymph nodes positive for tumour. Enlarged contralateral lymph nodes must be negative microscopically |

| 3 | Unresectable unilateral tumour infiltrating across the midlinea, with or without regional lymph node involvement; or localised unilateral tumour with contralateral regional lymph node involvement; or midline tumour with bilateral extension by infiltration (unresectable) or by lymph node involvement |

| 4 | Any primary tumour with dissemination to distant lymph nodes, bone, bone marrow, liver, skin and/or other organs (except as defined for stage 4S) |

| 4S | Localised primary tumour (as defined for stage 1, 2A or 2B), with dissemination limited to skin, liver, and/or bone marrowb (limited to infants < 1 year of age) |

Reference: Brodeur 1993.

Note: Multifocal primary tumours leg, bilateral adrenal primary tumours should be staged according to the greatest extent of disease, as defined above, and followed by a subscript letter M e.g. 3M. aThe midline is defined as the vertebral column. Tumours originating on one side and crossing the midline must infiltrate to or beyond the opposite side of the vertebral column. bMarrow involvement in stage 4S should be minimal, i.e. < 10% of total nucleated cells identified as malignant on bone marrow biopsy or on marrow aspirate. More extensive marrow involvement would be considered to be stage 4. The (Meta‐iodobenzylguanidine) MIBG scan (if performed) should be negative in the marrow.

3. Response to treatment.

| Response | Primary tumour | Metastatic sites |

| Complete response | No tumour | No tumour; catecholamines normal |

| Very good partial response | Decreased by 90% to 99% | No tumour; catecholamines normal; residual 99Tc bone changes allowed |

| Partial response | Decreased by more than 50% | All measurable sites decreased by > 50%. Bones and bone marrow: number of positive bone sites decreased by > 50%; no more than 1 positive bone marrow site allowed |

| Minimal response | No new lesions; > 50% reduction of any measurable lesion (primary or metastases) with < 50% reduction in any other; < 25% increase in any existing lesion | |

| No response | No new lesions; < 50% reduction but < 25% increase in any existing lesion | |

| Progressive disease | Any new lesion; increase of any measurable lesion by > 25%; previous negative marrow positive for tumour | |

Reference: Brodeur 1993.

Description of the intervention

Retinoic acid is a derivative of vitamin A (retinol) that includes 13‐cis retinoic acid, also known as isotretinoin, among others. Retinoic acid regulates the growth and development of epithelial cells, and inhibits growth of human neuroblastoma cells (Sidell 1982). It reduces morphological signs characteristic of several malignant human neuroblastoma cell lines (Sidell 1983). In a phase I clinical trial, 13‐cis retinoic acid was used in children with neuroblastoma after autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) without signs of myelosuppression (Villablanca 1995). In a phase III clinical trial, 13‐cis retinoic acid was added in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma after receiving high‐dose chemotherapy (HDCT) followed by autologous HSCT as well as after receiving standard‐dose chemotherapy (SDCT) (Matthay 1999). The test intervention of this review is the addition of retinoic acid as part of a therapy that comes after the consolidation therapy, which constitutes HDCT followed by autologous HSCT. Yalçin 2015 included three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in a Cochrane Review including the study Matthay 1999. The objective of the review was to compare the efficacy of HDCT followed by autologous HSCT with standard‐dose chemotherapy in children with high‐risk neuroblastoma.

How the intervention might work

Retinoic acid induces the differentiation of human neuroblastoma cell lines and stops uncontrolled cell growth in vitro (Reynolds 2003). Thus, retinoic acid might reduce the relapse rate, which occurs frequently after intensive chemotherapy with or without autologous HSCT in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma.

Why it is important to do this review

People with high‐risk neuroblastoma might have improved survival if retinoic acid as part of a postconsolidation therapy were added after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT. However, it is possible that a considerable number of patients may not respond to the addition of retinoic acid. It is therefore important to evaluate the current evidence base for the efficacy and the possible adverse events associated with this treatment. This review is an update of an earlier published Cochrane Review (Peinemann 2015).

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and adverse events of additional retinoic acid as part of a postconsolidation therapy after high‐dose chemotherapy (HDCT) followed by autologous haematopoietc stem cell transplantation (HSCT), compared to the same pretreatment with placebo retinoic acid or to no additional retinoic acid in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma (as defined by the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) classification system).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

People with high‐risk neuroblastoma according to the INRG or the Children's Oncology Group classification of risk groups shown in Table 2 and Table 5.

4. Children's Oncology Group assignment to low, intermediate, and high‐risk group.

| INSS stage | Age | MYCN | INPC classification | DNA index | Risk group |

| 1 | 0 to 21 y | Any | Any | Any | Low |

| 2A/2B | < 365 d | Any | Any | Any | Low |

| ≥ 365 d to 21 y | Nonamplified | Any | ‐ | Low | |

| ≥ 365 d to 21 y | Amplified | Favorable | ‐ | Low | |

| ≥ 365 d to 21 y | Amplified | Unfavorable | ‐ | High | |

| 3 | < 365 d | Nonamplified | Any | Any | Intermediate |

| < 365 d | Amplified | Any | Any | High | |

| ≥ 365 d to 21 y | Nonamplified | Favorable | ‐ | Intermediate | |

| ≥ 365 d to 21 y | Nonamplified | Unfavorable | ‐ | High | |

| ≥ 365 d to 21 y | Amplified | Any | ‐ | High | |

| 4 | < 548 d | Nonamplified | Any | Any | Intermediate |

| < 365 d | Amplified | Any | Any | High | |

| ≥ 548 d to 21 y | Any | Any | ‐ | High | |

| 4S | < 365 d | Nonamplified | Favorable | > 1 | Low |

| < 365 d | Nonamplified | Any | = 1 | Intermediate | |

| < 365 d | Nonamplified | Unfavorable | Any | Intermediate | |

| < 365 d | Amplified | Any | Any | High |

Reference: NCI PDQ 2017 DNA index: favorable > 1 (hyperdiploid) or < 1 (hypodiploid); unfavorable = 1 (diploid). Abbreviations. d: days of age; y: years of age.

Types of interventions

-

Intervention

Addition of retinoic acid as part of a postconsolidation therapy after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT

-

Comparator

Placebo retinoic acid or no addition of retinoic acid to postconsolidation therapy as described above

Types of outcome measures

We did not use the outcomes listed here as criteria for including studies, but these are the outcomes of interest within studies we identified for inclusion.

Primary outcomes

Overall survival: the event is death by any cause from the start of retinoic acid treatment

Treatment‐related mortality: incidence of deaths that were classified as treatment‐related, or the participants died of treatment complications

Secondary outcomes

Progression‐free survival: time staying free of disease progression from start of retinoic acid treatment; participants may still have the disease but their disease is stable or showing a partial response to treatment; the events are death from all causes or any progression of the disease

Event‐free survival: time staying free of any of a particular group of defined events from the start of retinoic acid treatment; participants may still have the disease; the events are death from all causes, any sign of the disease in participants who had a complete response to treatment, any relapse or progression of the disease, or events that were defined by the individual study protocol

Early toxicity: adverse events within 90 days of the therapy; incidence of all reported adverse events, severe events (grades 3 and 4 of toxicity), and incidence of toxicity‐related discontinuation of treatment. Examples of possibly‐reported classifications: the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTEP 2010); WHO Toxicity Grading Scale for Determining the Severity of Adverse Events (ICSSC 2003)

Late toxicity: adverse events including secondary malignancy occurring 90 days or more beyond therapy

Health‐related quality of life measured by validated questionnaires

Search methods for identification of studies

We used search methods as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and by Cochrane Childhood Cancer (Higgins 2011; Kremer 2008). We applied no language restrictions.

Electronic searches

We searched in the following medical literature databases. We tailored the terms and syntax used for the search in MEDLINE to the requirements of the other two databases. Cochrane Childhood Cancer ran the searches in the three mentioned electronic databases; the review authors ran all other searches.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (2016, Issue 11) using the search strategy shown in Appendix 1.

MEDLINE in PubMed (1946 to 24 November 2016) using the search strategy shown in Appendix 2.

Embase in Ovid (1947 to 24 November 2016) using the search strategy shown in Appendix 3.

We searched for ongoing trials by scanning the following online registries on 22 December 2016:

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/). Search: diagnosis 'neuroblastoma'; intervention 'retinoic acid'. Limits: study type 'interventional studies'; phase '2' or '3'.

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/). Search: diagnosis 'neuroblastoma'; intervention 'retinoic acid'. Limits: none.

We searched abstracts of the following annual meeting proceedings on 23 March 2017:

Annual Meetings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) (meetinglibrary.asco.org/abstracts): 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016 (ASCO Meetings 2012 to 2016). Search online by browsing abstracts by meeting and by category (Pediatric Oncology, Pediatric Solid Tumors): 'retinoic'. Search online all abstracts: 'retinoi'.

Annual Meetings of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) (www.bloodjournal.org/page/ash‐annual‐meeting‐abstracts): ASH meetings in 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016. Search online all abstracts: 'neuroblastoma'.

Congresses of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) (Pediatric Blood & Cancer at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/): 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016. Search in the downloaded PDF: 'retinoi'.

Searching other resources

We searched for information about trials not registered in electronic databases in reference lists of relevant articles and review articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In preparing this updated Cochrane Review, we endorsed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement, adhered to its principles and conformed to its checklist (Moher 2009). We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching and removed duplicates. Two review authors independently examined the remaining references. We obtained the full texts of potentially relevant references. Two review authors independently examined the eligibility of retrieved papers, resolving any disagreements by discussion and consultating with a third review author if necessary. We documented reasons for exclusion. If we identified multiple reports of one study we used the most recently published results. We checked the multiple reports for possible duplicate data, addressed the issue, and did not include duplicate data in our analyses. We include a study selection flow chart in the review.

Data extraction and management

For each included study, two review authors independently abstracted study characteristics and outcomes, including information on study design, participant characteristics (such as inclusion criteria, age, stage, co‐morbidity, previous treatment, number enrolled in each arm), interventions (such as type of retinoic acid, dose applied, duration of therapy, control treatment), risk of bias, follow‐up duration, outcome measures, and deviations from protocol, onto a data extraction form specifically designed for this review. We resolved any differences in opinion between the review authors by discussion or by appeal to a third review author.

Where possible, all data extracted were those relevant to an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, in which all participants were analysed in the groups to which they were assigned. If this was not possible, we reported it. We noted the time points at which outcomes were collected and reported.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently appraised the risks of bias in the included studies, resolving differences between review authors by discussion or by appeal to a third review author. We used the items listed in the Cochrane Childhood Cancer module (Kremer 2008), which is based on the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011):

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Blinding of participants (performance bias)

Blinding of personnel (performance bias)

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) for each outcome separately

Incomplete outcome data such as missing data for each outcome separately (attrition bias)

Selective reporting such as not reporting prespecified outcomes (reporting bias)

Other sources of bias such as bias related to the specific study design (other bias)

We applied the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). In general, a low risk of bias means that plausible bias is unlikely to seriously alter the results (for example, participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment). A high risk of bias means that plausible bias seriously weakens confidence in the results (for example, participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments). Unclear risk of bias means that plausible bias raises some doubt about the results (for example, the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement). In addition to the 'Risk of bias' tables, we included 'Methodological Quality' summaries. We took the results of the 'Risk of bias' assessment into account when interpreting the review results.

Measures of treatment effect

For analyses of time‐to‐event data, the primary effect measure was the HR. If the HR was not directly given in the publication, we estimated HRs according to methods proposed by Parmar 1998 and Tierney 2007. For all analyses we reported the 95% CIs.

We would have calculated the risk ratio for dichotomous outcomes. In the case of rare events, we planned to use the Peto odds ratio instead. We planned to analyse continuous data and present them using the mean difference (MD) if all results were measured on the same scale (e.g. length of hospital stay). If this was not the case (e.g. pain or quality of life), we planned to use the standardised mean difference (SMD). However, we did not identify either dichotomous or continuous data.

Dealing with missing data

We conformed to the Cochrane guidance for dealing with missing data (Higgins 2011). If data were missing or only imputed data were reported, we planned to contact trial authors to request data on the outcomes among participants who were assessed. When relevant data for study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment were missing, we contacted study authors to retrieve the missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to assess heterogeneity between studies by visual inspection of forest plots, by estimation of the percentage of heterogeneity between trials which cannot be ascribed to sampling variation (I2 statistic) (Higgins 2003) and, if possible, by subgroup analyses. If there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity, we planned to investigate and report the possible reasons for this. We considered an I2 statistic value greater than 50% to indicate substantial heterogeneity. However, as only one trial met our inclusion criteria, this was not applicable.

Assessment of reporting biases

In addition to the evaluation of reporting bias as described in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section, we planned to assess reporting bias (such as publication bias, time lag bias, multiple publication bias, location bias, citation bias, language bias) by constructing a funnel plot when there were enough included studies (that is, at least 10 studies included in a meta‐analysis) because otherwise the power of the tests is too low to distinguish chance from real asymmetry (Higgins 2011). Since we only included one trial in the review, this was not applicable.

Data synthesis

One review author analysed the data using Review Manager 2014, and another review author checked them. If sufficient clinically‐similar studies were available, we planned to pool their results, but since we included only one study this was not applicable. We did not identify trials with multiple groups that 'shared' a comparison group, so it was not necessary to divide the 'shared' comparison group into the number of treatment groups and comparisons between each treatment group and treat the split comparison group as independent comparisons. We used a random‐effects model with inverse variance weighting for all analyses (DerSimonian 1986).

We used GRADEpro 2015 to create the 'Summary of findings' table as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We presented overall survival, treatment‐related mortality, progression‐free survival, event‐free survival, early toxicity, late toxicity, and health‐related quality of life, provided that data were presented for both treatment arms. For each outcome two review authors independently assessed the quality of the evidence by using the five GRADE considerations, that is, study limitations, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned a subgroup analysis by age (younger than 18 months versus older than 18 months) since the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group classification has established 18 months as the optimum cut‐off for age. We also planned a subgroup analysis on MYCN gene amplification (with versus without MYCN amplification). However, the included study did not provide enough data to enable us to do this.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses of studies at low risk of bias versus studies at high or uncertain risk of bias, but since we include only one trial this was not applicable.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

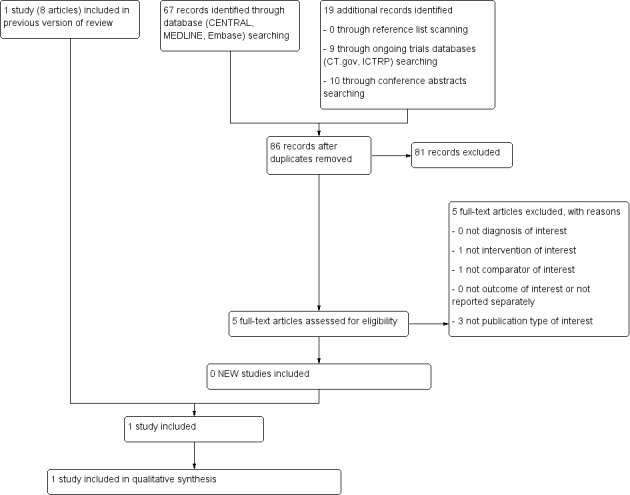

See Figure 1 for the study flow diagram of the search for the previous and the current version of this Cochrane Review.

1.

1Study flow diagram of current review version.

Abbreviations. CT.gov: ClinicalTrials.gov; ICTRP: International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

For the original version of the review we retrieved 591 records after searching the databases CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase (on 1 October 2014) and removing duplicates. We screened the title or abstract, or both, and excluded 492 records. We screened the full texts of 99 publications that reported potentially relevant data and excluded 91 publications. We included eight publications associated with one RCT (Matthay 1999). The study by Matthay et al., published in 1999, reported the main information and results and the publication by Matthay et al. 2009 updated these data. Four further publications were also associated with the study. Two conference proceedings (Reynolds 1998; Reynolds 2002; see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table) were associated with the study Matthay 1999. However, as it is known that information provided in conference proceedings often differs substantially from information provided in subsequent full‐text publications (Yoon 2012), we did not include these results in our analyses. We retrieved 31 records searching the study registries ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal, duplicates removed (27 December 2013), but found no additional relevant studies. We found no additional studies by screening the reference lists of relevant articles and reviews.

For this update we retrieved 67 records after searching the databases CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase (on 24 November 2016) and removing duplicates. We screened the title or abstract, or both, and excluded 62 records. We screened the full texts of five publications that reported potentially relevant data and excluded all five of them. We retrieved nine records by searching the study registries ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal, duplicates removed (22 December 2016), but found no additional relevant studies. We found no additional studies by screening the reference lists of relevant articles and reviews or by screening the conference abstracts. We knew about an erratum associated with the Matthay 1999 study (Erratum 2014), which we incorporated in this update. It was not necessary to contact authors to for missing information.

Included studies

We have described the characteristics of the included RCT in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Design

We include a randomised, prospective, parallel, controlled clinical trial. Matthay 1999 enrolled participants from 1991 to 1996.

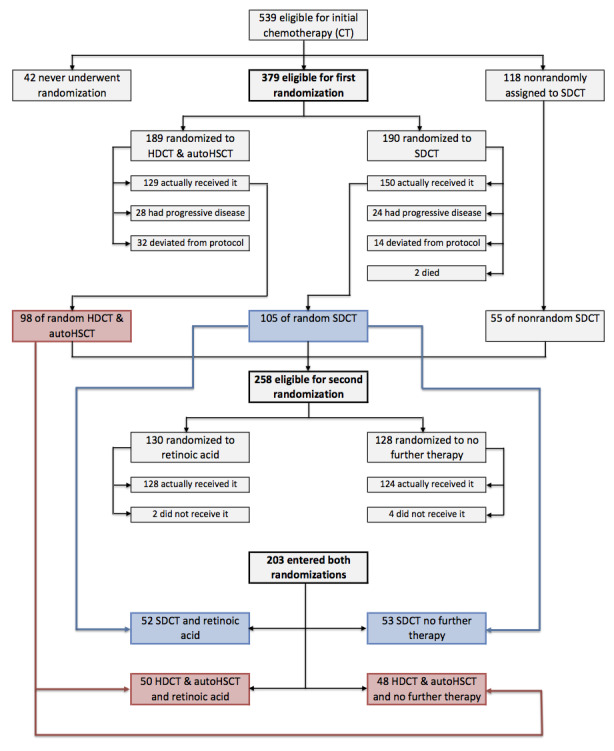

Sample sizes

Matthay 1999 randomised 379 participants with high‐risk neuroblastoma to either HDCT followed by autologous HSCT (N = 189) or to continuous standard‐dose chemotherapy without transplantation (N = 190) in a first randomisation (Figure 2). After the first randomisation, 98 of the transplanted participants progressed to a second randomisation. Of the 98 transplanted participants, 50 were randomised to additional retinoic acid and 48 to no further therapy (Figure 2).

2.

Flow of patients in the Matthay 1999 study (as prepared by review author FP). Abbreviations. BMT: bone marrow transplantation; ContCT: continuation chemotherapy; CT: chemotherapy; HDCT: high‐dose chemotherapy; RA: retinoic acid.

Setting

Matthay 1999 was a multicentre study conducted in the United States of America.

Participants

Matthay 1999 included participants with high‐risk neuroblastoma stages 1, 2, 3, and 4, although most had stage 4. Patients who had progressive disease before week eight of the protocol were deemed ineligible for the trial. The characteristics of 98 participants with autologous HSCT randomised to retinoic acid or to no further therapy were not separately reported. The duration of their follow‐up was not mentioned.

Interventions

Participants in the retinoic arm received six cycles of retinoic acid. One cycle consisted of 13‐Cis retinoic acid at a dose of 160 mg/mg/m2 a day for 14 consecutive days in a 28‐day cycle (14 days on, 14 days off), resulting in a cumulative dose after 28 days of 2240 mg/m2. The control group received no further treatment. Regarding the consolidation therapy, high‐dose chemotherapeutic substances and doses were specified, such as carboplatin, etoposide, melphalan, and total‐body irradiation.

Primary outcomes

Matthay 1999 reported overall survival. Treatment‐related mortality was not reported separately for the treatment groups of interest.

Secondary outcomes

Matthay 1999 reported event‐free survival. It did not report early and late toxicity separately for the treatment groups of interest. Progression‐free survival and health‐related quality of life were not reported.

Excluded studies

We excluded 96 records of potentially relevant full‐text articles, 91 records in the previous version and five records (Chen 2015; Kushner 2015; Kushner 2016; Mora 2015; Mostoufi‐Moab 2016) in the current version (Figure 1) based on:

not the diagnosis of interest: n = 7 (seven in the previous version and none in the current version);

not the intervention of interest: n = 21 (20 in the previous version and one in the current version); this includes Kohler 2000 in which 49 of 175 participants (28%) did not receive high‐dose chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation and no separate data for eligible participants were available;

not the comparator of interest: n = 47 (46 in the previous version and one in the current version);

not the outcome of interest or not reported separately: n = 5 (five in the previous version and none in the current version);

not the publication type of interest: n = 16 (13 in the previous version and three in the current version).

We have described the excluded studies in more detail in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

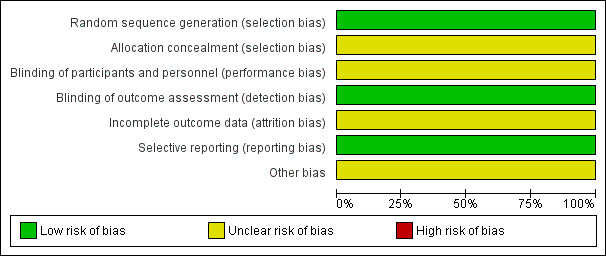

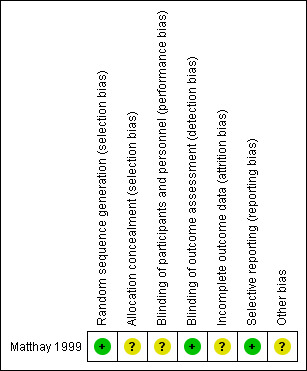

The 'Risk of bias' tables in the Characteristics of included studies section provide details of each item of the 'Risk of bias' tool for RCTs. Figure 3 and Figure 4 provide an overview.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Matthay 1999 clearly described the random sequence generation, which we judged to be at low risk of bias. The concealment of the allocation was not specified, which prompted us to judge it as an unclear risk of selection bias.

Blinding

Matthay 1999 did not report blinding of investigators and participants and we judged it to be at unclear risk of performance bias. We judged a low risk of detection bias, as the study committee and investigators were unaware of participants' treatment assignments, and the study was monitored by an independent committee according to a group sequential monitoring plan.

Incomplete outcome data

The study did not report whether in all eligible participants all outcomes (i.e. overall and event‐free survival) were assessed, so there was an unclear risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

Matthay 1999 reported the outcomes in accord with their protocol. Concerning multiple (duplicate) publication bias, we found eight publications that reported results from the Matthay 1999 study. It appears probable that data for the same participants were included in several publications. However, we did not include duplicate data in the review. Overall, we judged there to be a low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Analysis of data in Matthay 1999 was conducted using the data of the randomised participants, which should be consistent with the ITT principle. However, it was unclear if all 98 participants received the treatment to which they were randomised. Also, not all participants treated with transplantation in the first randomisation and without progressive disease afterwards were included in the second randomisation. It is unclear how many eligible participants did not undergo the second randomisation. The consequences of two randomisations in one study for the risk of bias are unclear. We judged there to be an unclear risk of other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Overall survival

We extrapolated the appropriate data on overall survival from the Kaplan Meier survival curve displayed in Figure 4B of the 2009 update article of Matthay 1999. We then calculated a HR of 0.87 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.63; low quality of evidence; Analysis 1.1; Figure 5). The difference between the groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.66). It was not reported if data for all 98 eligible participants were available, so it is unclear if this is an ITT analysis.

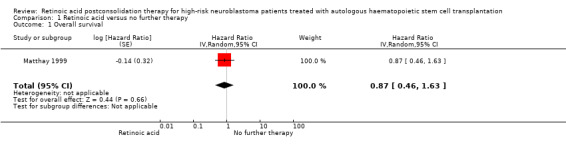

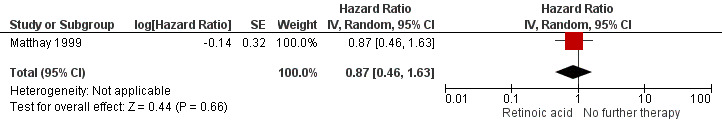

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Retinoic acid versus no further therapy, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Retinoic acid versus no further therapy, outcome: 1.1 Overall survival. Abbreviations. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance; SE: standard error.

We calculated the HR using the complete follow‐up period of the trial. The study also reported five‐year overall survival rates: 59% (standard error 8%) for the retinoic acid group and 41% (standard error 8%) for the no‐further‐therapy group (P value not reported). The values comply with the erratum, which corrected the value of the second standard error.

Treatment‐related mortality

We did not identify any results for treatment‐related mortality reported separately for the retinoic acid group and the control group.

Secondary outcomes

Progression‐free survival

We did not identify any results for progression‐free survival.

Event‐free survival

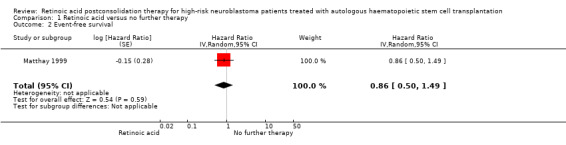

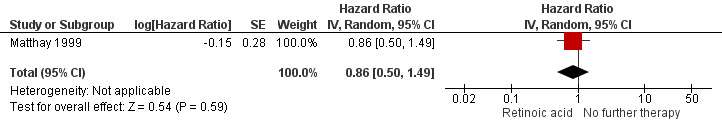

We extrapolated the appropriate data on event‐free survival from the Kaplan Meier survival curves displayed in Figure 4A of the 2009 update article of Matthay 1999. Then, using the complete follow‐up period of the trial, we calculated a HR of 0.86 (95% CI 0.50 to 1.49; low quality of evidence; Analysis 1.2; Figure 6). The difference between the groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.59). It was not reported if data for all 98 eligible participants were available, so it is unclear if this is an ITT analysis.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Retinoic acid versus no further therapy, Outcome 2 Event‐free survival.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Retinoic acid versus no further therapy, outcome: 1.2 Event‐free survival. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance; SE: standard error.

Early toxicity

Matthay 1999 did not separately report severe adverse events for the eligible 98 participants.

Late toxicity including secondary malignancy

We did not identify any results for late toxicity including secondary malignancy reported separately for the retinoic acid group and the control group.

Health‐related quality of life

We did not identify any results for health‐related quality of life.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This Cochrane Review evaluates the current state of evidence on the efficacy of retinoic acid versus control treatment in people diagnosed with high‐risk neuroblastoma, pretreated with HDCT followed by autologous HSCT. This is an update of a previously published Cochrane Review. We did not identify any new studies.

We include one RCT (Matthay 1999) of 98 participants with high‐risk neuroblastoma who received autologous HSCT after a first randomisation and then 13‐cis‐retinoic acid (n = 50) or no further treatment (n = 48) after a second randomisation. This group had no progressive disease after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT. The objectives of study Matthay 1999 were to assess "whether myeloablative therapy in conjunction with transplantation of autologous bone marrow improved event‐free survival compared with chemotherapy alone, and whether subsequent treatment with 13‐cis‐retinoic acid (isotretinoin) further improves event‐free survival". The comparisons were between groups that differed in more than only the intervention of interest. Our review, however, was only interested in the efficacy of retinoic acid versus control treatment in people who were pretreated with transplantation. As a result, only a subset of the participants from the Matthay 1999 were eligible for for inclusion in the review.

There was no statistically significant difference between the treatment groups in either overall survival (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.63; one trial; P = 0.66, low quality of evidence) or event‐free survival (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.49; one trial; P = 0.59, low quality of evidence). We calculated the HRs using the complete follow‐up period of the trial. The study also reported survival estimates at a fixed point in time. At the time point of five years, overall survival was estimated to be 59% (SE 8%) for the retinoic acid group and 41% (SE 8%) for the no‐further‐therapy group (P value not reported). No data were available for the other outcomes of interest (i.e. treatment‐related mortality, progression‐free survival, early and late toxicity, and health‐related quality of life) (see Table 1).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The inclusion of only one study in this review limits the inferences we can draw from the extracted data. 'No evidence of effect', as identified in this review, is not the same as 'evidence of no effect'. The reason that we found no statistically significant difference between study groups could be the fact that the number of participants included was too small to detect a difference between the treatment groups (i.e. low power). Also, the included study was not designed to identify a superior treatment combination.

Furthermore, the study was conducted from 1991 to 1996 (Matthay 1999). The applicability of these data to current clinical practice is limited, as medical knowledge and terms of health care have progressed and changed significantly since then. The results may therefore not be applicable to patients who are treated today. Also, the applicability may depend on the dosing regimen. According to Veal 2013, the medication dose may have a marked influence on retinoic acid plasma concentrations in children with high‐risk neuroblastoma. Matthay 2013 suggested that the medication dose may have the potential to cause different outcomes between studies. Prior treatment and the response to that treatment may also play a role. Since we only found only one eligible study we could not assess these issues.

Another point is that the included RCT used an age of one year as the cut‐off point for pretreatment risk stratification. Recently the age cut‐off for high‐risk disease was changed from one year to 18 months (Cohn 2009). As a result, it is possible that people with what is now classified as intermediate‐risk disease were included in the high‐risk groups. Consequently, the relevance of the results of these studies to current practice can be questioned. Survival rates may be overestimated due to the inclusion of participants with intermediate‐risk disease.

Only data on overall and event‐free survival were available for the patient population we were interested in (high‐risk neuroblastoma patients pretreated with HDCT followed by autologous HSCT). The included study did not provide data on, for example, toxicity and quality of life in these participants. As a result we cannot draw any conclusions regarding those outcomes, but they are of course important for clinical practice.

Cheung 2014 addressed the problem of end point selection and questioned the importance of HDCT followed by autologous HSCT: "A rethinking of the consolidation strategy for HR‐NB [explanation: high‐risk neuroblastoma] would be consistent with the general consensus among pediatric oncologists that ASCT [explanation: HDCT followed by autologous HSCT] in all other extracranial pediatric solid tumours is no longer recommended based on unsatisfactory risk‐benefit and cost‐benefit ratios assembled worldwide [the following references was used: Ratko 2012]."

Since information on the toxicity of an intervention is very important we decided to perform a post hoc search in the previous version for studies describing toxicity possibly associated with retinoic acid treatment, to get an impression of the importance of this outcome. We did not update the post hoc search for studies on toxicity data. We screened the 91 studies excluded in the search for the previous version for results on adverse events after retinoic acid application after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma. We included all types of clinical studies and accepted meeting abstracts. We excluded narrative publication types such as nonsystematic reviews, letters and editorials. We did not report on those who received retinoic acid but did not receive transplantation. Thirty‐three out of these 91 potentially relevant publications were relevant (see Table 6); more than 1000 participants with high‐risk neuroblastoma were evaluated. In Kohler 2000, the exact number of relevant participants was not reported. 13‐cis‐retinoic acid (CRA, isotretinoin) was applied in 30 studies. 4‐hydroxyphenylretinamide (fenretinide) was applied in three studies. In 22 of the 33 studies, the authors reported participants with mild to severe organ toxicities associated with retinoic acid treatment. Most participants had mild and transient symptoms such as dry skin, cheilitis, rash, and bone pain. Retinoic acid was applied after a series of highly toxic chemotherapeutic regimens such as induction chemotherapy, myoablative chemotherapy, and autologous HSCT. It is difficult to distinguish adverse events associated with one agent rather than another, and it is difficult to draw causal inferences. Nevertheless, Khan 1996 reported a correlation between peak serum levels of retinoic acid and grade 3 to 4 toxicity such as involvement of skin, liver, as well as hypercalcaemia. We did not extract grade 1 to 2 toxicities. Maurer 2013 reported two participants with probable attribution of an elevation of serum alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase and reported one participant with definite attribution of diarrhoea. However, six of 32 evaluated participants did not have a prior HDCT followed by autologous HSCT and the assignment of individual participants was not reported. We identified 13 studies that specifically reported an association of distinct adverse events with retinoic acid treatment (Clarke 2003; Cross 2009; Haysom 2005; Inamo 1999; Kohler 2000; Kreissman 2013; Marmor 2008; Mugishima 2008; Nishimura 1997; Rayburg 2009; Turman 1999; Villablanca 1993; Villablanca 1995). It should be noted that this was not a complete search for toxicity data and we did not assess the risks of bias in these studies. As a result, we can draw no definitive conclusions from these data.

5. Toxicity possibly associated with retinoic acid after high‐dose chemotherapy followed by autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

| Study | Study design | Type of HSCT | Type of RA | Dose1 | Pat2 | Type of adverse event (N of affected participants) |

| Clarke 2003 | CR | PBSCT | CRA | 160 | 1 | Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (1) |

| Cross 2009 | CR | NR | CRA | 160 | 1 | Hypercalcaemia (1), osteoblastic lesions (1) |

| De Kraker 2008 | SA‐IS | BMT or PBSCT | CRA | 160 | 44 | NR |

| Granger 2012 | SA‐IS | PBSCT | CRA | 160 | 33 | NR |

| Hamidieh 2012 | SA‐IS | PBSCT | CRA | 120 to 160 | 14 | NR |

| Haysom 2005 | CR | BMT | CRA | 160 | 2 | Bone marrow transplant nephropathy (2) |

| Inamo 1999 | CR | BMT | CRA | 33 to 1023 | 1 | Growth failure (1) |

| Khan 1996 | SA‐IS | BMT | CRA | 100 to 200 | 31 | Grade 3/4 toxicity of skin, liver and hypercalcaemia correlated with peak serum levels of CRA |

| Kletzel 2002 | SA‐IS | PBSCT | CRA | 160 | 12 | Ataxia (1) |

| Kogner 2004 | RCT | BMT | CRA | NR | 12 | NR |

| Kohler 2000 | RCT | NR | CRA | 15 to 224 | NR | Dry skin (47), cheilitis (24), bone pain (16), other (13) |

| Kreissman 2013 | RCT | PBSCT | CRA | 160 | 192 | Grade 3 toxic effects: hypertension (4), hematuria (2), elevated serum creatinine (2), proteinuria (3); purged and non‐purged transplantation group combined |

| Kushner 2003a | CS | NR | CRA | 160 | 1 | Cheilitis (1) |

| Laskin 2011 | CS | NR | CRA | NR | 20 | NR |

| Marabelle 2009 | CR | NR | CRA | 160 | 3 | Hypercalcaemia (3) |

| Marmor 2008 | CR | NR | Fenretinide | 666 to 20515 | 2 | Rod electroretinogram suppression (2) |

| Mastrangelo 2011 | SA‐IS | PBSCT | CRA | 160 | 8 | NR |

| Matthay 2006 | SA‐IS | BMT | CRA | 160 | 22 | NR |

| Mugishima 2008 | CR | BMT | CRA | 130 to 400 | 2 | Hypercalcaemia (2) |

| Nishimura 1997 | CR | BMT | CRA | 33 to 1023 | 1 | Generalised metaphyseal modification (1) |

| Park 2011 | SA‐IS | PBSCT | CRA | 160 | 30 | NR |

| Rayburg 2009 | CR | NR | Fenretinide | 2210 | 1 | Langerhans cell histiocytosis (1) |

| Saarinen‐Pihkala 2012 | SA‐IS | BMT or PBSCT | CRA | NR | 36 | NR |

| Simon 2011 | SA‐IS | NR | CRA | 160 | 75 | NR |

| Sirachainan 2008 | CR | NR | CRA | 140 | 1 | NR |

| Sung 2007 | SA‐IS | PBSCT | CRA | 125 | 44 | Skin eruption, particularly face |

| Turman 1999 | CR | BMT | CRA | 160 | 2 | Bone marrow transplant nephropathy (2) |

| Veal 2007 | SA‐IS | NR | CRA | 160 | 28 | Mild skin toxicity (9), cheilitis (1), hypercalcaemia (2) |

| Veal 2013 | SA‐IS | NR | CRA | 160 | 103 | Grade 3 ‐ 4 skin toxicity or cheilitis (5) |

| Villablanca 1993 | SA‐IS | BMT | CRA | 100 to 200 | 49 | Dose‐limiting toxicity of hypercalcaemia (3), arthralgia and myalgia (1), grade 1 to 3 hypercalcaemia (9) |

| Villablanca 1995 | SA‐IS | BMT | CRA | 200 | 51 | Hypercalcaemia (3), rash (2) |

| Villablanca 2011 | SA‐IS | NR | Fenretinide | 1800 to 2475 | 626 | Rash (1), diarrhoea (1), nausea (2), vomiting (1), nyktalopia (1), abdominal pain (4) |

| Yu 2010 | RCT | NR | CRA | 160 | 108 | "Few toxic effects" |

Notice: Studies presented in this table were not eligible for inclusion in this review.

1Dose in mg/m2/day. The unit mg/kg may be transformed to mg/m2. The average body weight, body length, and body surface of a 6‐month‐old child may be 8 kg, 67 cm, and 0.39 m2, thus 8 kg divided by 0.39 m2 is roughly equalto a conversion factor of 20 (CDC 2000a). This factor increases continuously with age. The average body weight, body length, body surface of an 11‐year‐old child may be 36 kg, 143 cm, and 1.20 m2, thus 36 kg divided by 1.20 m2 is roughly equal to a conversion factor of 30 (CDC 2000b). The unit mg per day may be transformed to m2 per day. For example, 300 mg per day may vary on average between 769 mg/m2 (300 mg/0.39 m2) and 250 m2 (300 mg/1.20 m2)

2Participants treated with retinoic acid after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT acid and evaluated for toxicity.

3Inamo 1999; Nishimura 1997: Patients received retinoic acid at a dose of 40 mg per day. The daily dose may vary on average between 102 mg/m2 (40 mg/0.39 m2) and 33 m2 (40 mg/1.20 m2)

4Kohler 2000: Participants received retinoic acid at a dose of 0.75 mg/kg per day. The daily dose may vary on average between 15 mg/m2 (0.75 mg/kg * 20) and 22 mg/m2 (0.75 mg/kg * 30).

5Marmor 2008: Participants received retinoic acid at a dose of 800 mg per day. The daily dose may vary on average between 2051 mg/m2 (800 mg/0.39 m2) and 666 m2 (800 mg/1.20 m2).

6Villablanca 2011: 51 of the 62 participants received HSCT.

BMT: bone marrow transplantation; CR: case report; CS: case series; CRA: 13‐cis‐retinoic acid; HDCT: high‐dose chemotherapy; HSCT: haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; N: number of participants; NR: not reported; PBSCT: peripheral blood stem cell transplantation; RA: retinoic acid; SA‐IS: single‐arm intervention study such as phase‐1 or phase‐2 clinical trial

We have only included RCTs, since it is widely recognised that an RCT is the only study design which can be used to obtain unbiased evidence on the use of different treatment options, provided that the design and execution of the RCT are adequate. However, even though RCTs are the highest level of evidence, it should be recognised that data from non‐randomised studies are available.

Quality of the evidence

Separate analyses of transplanted patients treated with or without additional retinoic acid were not reported in the included study. Nevertheless, the data were expressed in the survival curves presented in the study report. We extrapolated survival data from these graphs and estimated a HR to compare the two treatment groups. However, these estimates may be somewhat imprecise because the deduction and estimation process may deviate from the original data. Nevertheless, even considerable deviations would not be expected to change the observed difference in survival estimates.

The risk of bias in the included study was difficult to assess, in part due to a lack of reporting. As a result, we could not rule out the possible presence of selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, and other bias. However, this remains the best available evidence from RCTs comparing the efficacy of additional retinoic acid versus control treatment after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT in high‐risk neuroblastoma patients.

Based on the GRADE assessments, in which we have looked at the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias), we judged the quality of the evidence for the two outcomes for which data were available as low; we downgraded the quality of the evidence due to risks of bias and imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

One of the strengths of this review is the breadth of the search strategy, such that study retrieval bias is very unlikely. Nevertheless, there remains a slight possibility that an unknown number of studies were not registered and not published. Duplicate publication bias is very unlikely, because we searched for follow‐up papers of a single study to ensure that we included the updated version. Also, we excluded secondary analyses of registers or databases, which may use data that have been published previously by individual contributing study centres. Overall, the possibility of reporting bias seems to be low.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We identified one RCT that evaluated additional 13‐cis‐retinoic acid after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT versus no additional retinoic acid in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma without progressive disease. The difference in overall survival and event‐free survival between both treatment alternatives was not statistically significantly different. This could be the result of low power; the included study was not designed to identify a superior treatment combination. Information on other outcomes, like toxicity, were not available. Also, this trial was performed between 1991 and 1996. Since then many changes in, for example, treatment and risk classification have occurred. Therefore, based on the currently available evidence, we are uncertain about the effects of additional retinoic acid after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT in people with high‐risk neuroblastoma.

Implications for research.

More research is needed for a definitive conclusion. Future trials on the use of retinoic acid (either with or without other treatments like anti‐GD2) after HDCT followed by autologous HSCT for people with high‐risk neuroblastoma should be RCTs focusing on overall survival, adverse effects, and quality of life. RCTs should be performed in homogeneous study populations (like stage of disease) and have a long‐term follow‐up. The number of included participants should be sufficient for the power needed for the results to be reliable. Different risk groups, using the most recent definitions, should be taken into account. For example, particular subgroups of participants may benefit from retinoic acid.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 November 2016 | New search has been performed | We updated the search for eligible studies to 24 November 2016. |

| 24 November 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | We could include no new studies in this update; we found an erratum of the already‐included study, but the information provided did not change the conclusions. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 7, 2013 Review first published: Issue 1, 2015

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 April 2016 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Editorial Base of Cochrane Childhood Cancer for their advice and support. The editorial base of Cochrane Childhood Cancer is funded by Stichting Kinderen Kankervrij (KiKa). We thank Jan Kohler for a timely and appropriate response to an inquiry.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library)

1. For Retinoic acid the following text words were used:

retinoic acid OR retinoic acids OR Retinoid* OR Retinoid OR Retinoids OR tretinoin OR Vitamin A Acid OR trans‐Retinoic Acid OR trans Retinoic Acid OR all‐trans‐Retinoic Acid OR all trans Retinoic Acid OR beta‐all‐trans‐Retinoic Acid OR beta all trans Retinoic Acid OR 13‐cis‐RA OR 13‐cis‐retinoic acid OR 4759‐48‐2 OR Retin‐A OR Retin A OR Vesanoid OR isotretinoin OR ATRA OR Accutane OR Airol OR Dermairol

2. For Neuroblastoma the following text words were used:

neuroblastoma OR neuroblastomas OR neuroblast* OR ganglioneuroblastoma OR ganglioneuroblastomas OR ganglioneuroblast* OR neuroepithelioma OR neuroepitheliomas OR neuroepitheliom* OR esthesioneuroblastoma OR esthesioneuroblastomas OR esthesioneuroblastom* OR schwannian

Final search 1 and 2 The search was performed in title, abstract or keywords

[*=zero or more characters]

Appendix 2. Search strategy for MEDLINE (PubMed)

1. For Retinoic acid the following MeSH headings and text words were used:

retinoic acid OR retinoic acids OR Retinoid* OR Retinoid OR Retinoids OR tretinoin OR Vitamin A Acid OR Acid, Vitamin A OR trans‐Retinoic Acid OR Acid, trans‐Retinoic OR trans Retinoic Acid OR all‐trans‐Retinoic Acid OR Acid, all‐trans‐Retinoic OR all trans Retinoic Acid OR beta‐all‐trans‐Retinoic Acid OR beta all trans Retinoic Acid OR 3‐cis‐RA OR 13‐cis‐retinoic acid OR 4759‐48‐2 OR Retin‐A OR Retin A OR Vesanoid OR isotretinoin OR ATRA OR Accutane OR Airol OR Dermairol

2. For Neuroblastoma the following MeSH headings and text words were used:

neuroblastoma OR neuroblastomas OR neuroblast* OR ganglioneuroblastoma OR ganglioneuroblastomas OR ganglioneuroblast* OR neuroepithelioma OR neuroepitheliomas OR neuroepitheliom* OR esthesioneuroblastoma OR esthesioneuroblastomas OR esthesioneuroblastom* OR schwannian

3. For RCTs and CCTs the following MeSH headings and text words were used:

((randomized controlled trial[pt]) OR (controlled clinical trial[pt]) OR (randomized[tiab]) OR (placebo[tiab]) OR (drug therapy[sh]) OR (randomly[tiab]) OR (trial[tiab]) OR (groups[tiab])) AND (humans[mh])

Final search 1 and 2 and 3

[pt = publication type; tiab = title, abstract; sh = subject heading; mh = MeSH term; *=zero or more characters; RCT = randomized controlled trial; CCT = controlled clinical trial]

Appendix 3. Search strategy for Embase (OVID)

1. For Retinoic acid the following Emtree terms and text words were used:

1. exp retinoic acid/ 2. (retinoic acid or retinoic acids).mp. 3. (retinoid* or retinoid or retinoids).mp. 4. tretinoin.mp. 5. Vitamin A Acid.mp. 6. (trans‐retinoic Acid or trans retinoic Acid or all‐trans‐Retinoic Acid or all trans Retinoic Acid).mp. 7. (beta‐all‐trans‐retinoic acid or beta all trans retinoic acid or 3‐cis‐RA or 13‐cis‐retinoic acid).mp. 8. 4759‐48‐2.rn. 9. (Retin‐A or Retin A or Vesanoid or isotretinoin or ATRA or Accutane or Airol or Dermairol).mp. 10. or/1‐9

2. For Neuroblastoma the following Emtree terms and text words were used:

1. exp neuroblastoma/ 2. (neuroblastoma or neuroblastomas or neuroblast$).mp. 3. (ganglioneuroblastoma or ganglioneuroblastomas or ganglioneuroblast$).mp. 4. (neuroepithelioma or neuroepitheliomas or neuroepitheliom$).mp. 5. exp esthesioneuroblastoma/ 6. (esthesioneuroblastoma or esthesioneuroblastomas or esthesioneuroblastoma$).mp. 7. schwannian.mp. 8. or/1‐7

3. For RCTs and CCTs the following Emtree terms and text words were used:

1. Randomized Controlled Trial/ 2. Controlled Clinical Trial/ 3. randomized.ti,ab. 4. placebo.ti,ab. 5. randomly.ti,ab. 6. trial.ti,ab. 7. groups.ti,ab. 8. drug therapy.sh. 9. or/1‐8 10. Human/ 11. 9 and 10

Final search 1 and 2 and 3

[mp = title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name]

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Retinoic acid versus no further therapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 1 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.46, 1.63] | |

| 2 Event‐free survival | 1 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.50, 1.49] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Matthay 1999.

| Methods |

Setting

Duration of enrollment

Randomisation

Median follow‐up time

|

|

| Participants |

Eligibility criteria

Number of patients eligible for this review

Age

Gender

Stage of disease

Remission status

Compliance with randomisation

Previous treatment, except initial and consolidation chemotherapy

Comorbidity

|

|

| Interventions |

All participants

First randomisation BMT arm (patients in the continuation chemotherapy arm were not eligible for this review)

2nd randomisation Retinoic acid arm

Control arm

|

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcomes

Secondary outcomes

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A permuted‐block design was used for the random assignment of approximately equal numbers of participants from each of 2 strata (those with and those without metastatic disease) to transplantation or continuation chemotherapy. The 2nd randomisation was similarly balanced with respect to the numbers of participants from each group of the first randomisation and non‐randomised participants who were ineligible for transplantation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment was not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Blinding of participants, physicians and nurses was not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The study committee and investigators were unaware of participants' treatment assignments, and the study was monitored by an independent committee according to a group sequential monitoring plan |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It was not reported if all reported outcomes for all participants were assessed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Reporting was in agreement with the protocol with regard to the outcome measures. We were concerned with the possibility that data for the same participants were included in several publications. However, we did not include duplicate data in the review |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Analysis was conducted using the data of the randomised participants, which should be consistent with the ITT principle. It was unclear if all 98 participants received the treatment to which they were randomised. Also, not all participants treated with transplantation in the first randomisation and without progressive disease afterwards were included in the 2nd randomisation. It is unclear how many eligible patients did not undergo the 2nd randomisation. The consequences of 2 randomisations in 1 study for the risk of bias are unclear. |

AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; BMT: bone marrow transplantation; cGy: centi‐Gray; CR: complete response; N: number.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Adamson 1997 | Not intervention of interest: not HDCT followed by autologous HSCT |

| Adamson 2007 | Not comparator of interest |

| Aksoylar 2013 | Not comparator of interest |

| Anderson 2005 | Not intervention of interest: not HDCT followed by autologous HSCT, only title/abstract available |

| Atra 1996 | Not intervention of interest: not retinoic acid |

| Bagatell 2014 | Not comparator of interest: all participants received retinoic acid |

| Bauters 2011 | Not publication type of interest |

| Castel 2004 | Not publication type of interest |

| Chan 2007 | Not intervention of interest: not HDCT followed by autologous HSCT |

| Chen 2015 | Not an intervention of interest: not a HDCT followed by autologous HSCT |

| Clarke 2003 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Cross 2009 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| De Kraker 2008 | Not comparator of interest |

| Di Bella 2009 | Not intervention of interest: not HDCT followed by autologous HSCT, only title/abstract available |

| Dmitrovsky 2004 | Not publication type of interest |

| Elimam 2006 | Not intervention of interest: not retinoic acid, only title/abstract available |

| Finklestein 1992 | Not intervention of interest: not HDCT followed by autologous HSCT |

| Formelli 2008 | Not intervention of interest: not HDCT followed by autologous HSCT |

| Formelli 2010 | Not intervention of interest: not HDCT followed by autologous HSCT |

| Fouladi 2010 | Not outcome of interest or not reported separately |

| French 2013 | Not intervention of interest: not retinoic acid |

| Frgala 2007 | Not comparator of interest, only title/abstract available |

| Garaventa 2003 | Not comparator of interest |

| Granger 2012 | Not comparator of interest |

| Grissom 1996 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Gyorfy 2003 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Hamidieh 2012 | Not comparator of interest: all participants received retinoic acid |

| Haysom 2005 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Hoefer‐Janker 1969 | Not diagnosis of interest, only title/abstract available |

| Inamo 1999 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Kazanowska 2008 | Not intervention of interest: not HDCT followed by autologous HSCT |

| Khan 1996 | Not comparator of interest: pharmacokinetic study |

| Kletzel 2002 | Not publication type of interest: not RCT |

| Kogner 2004 | Not comparator of interest |

| Kohler 2000 | Not intervention of interest: 28% (49/175) patients did not receive high‐dose chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation confirmed by author inquiry and after contacting the first author of this study, it became clear that separate data on the eligible participants were not available |

| Kreissman 2013 | Not comparator of interest |

| Kushner 1994 | Not intervention of interest: not consolidation therapy |

| Kushner 2001a | Not intervention of interest: not HDCT followed by autologous HSCT |

| Kushner 2001b | Not publication type of interest: not RCT |

| Kushner 2003a | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Kushner 2003b | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Kushner 2015 | Not publication type of interest: not RCT |

| Kushner 2016 | Not a comparator of interest: both arms received retinoic acid |

| Ladenstein 2004 | Not comparator of interest |

| Ladenstein 2014 | Not comparator of interest |

| Laskin 2011 | Not publication type of interest: not RCT |

| Levin 2006 | Not diagnosis of interest |

| Lie 1993 | Not publication type of interest: narrative review |

| Marabelle 2009 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Maris 2000 | Not comparator of interest |

| Marmor 2008 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Mastrangelo 2011 | Not publication type of interest: not RCT |

| Matthay 1995 | Not publication type of interest: narrative review |

| Matthay 1999a | Not intervention of interest, only title/abstract available |

| Matthay 2000 | Not publication type of interest: editorial |

| Matthay 2006 | Not intervention of interest |

| Matthay 2013 | Not publication type of interest: comment |

| Maurer 2013 | Not comparator of interest |

| Maurer 2014 | Not comparator of interest |

| McCann 1993 | Not diagnosis of interest, only title/abstract available |

| Mora 2015 | Not publication type of interest: not RCT |

| Mostoufi‐Moab 2016 | Not publication type of interest: not RCT |

| Mugishima 1995 | Not intervention of interest, only title/abstract available |

| Mugishima 2008 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Nishimura 1997 | not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Olgun 2008 | Not intervention of interest: not retinoic acid, only title/abstract available |

| Ozkaynak 2014 | Not comparator of interest |

| Park 2005 | Not publication type of interest: duplicate data |

| Park 2011 | Not comparator of interest |

| Pearson 2008 | Not comparator of interest: all participants received retinoic acid |

| Rayburg 2009 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Reed 1999 | Not diagnosis of interest: not high‐risk neuroblastoma |

| Reynolds 2001 | Not publication type of interest: narrative review |

| Richtig 2005 | Not diagnosis of interest: melanoma |

| Rustin 1982 | Not diagnosis of interest: not neuroblastoma |

| Saarinen‐Pihkala 2012 | Not comparator of interest |

| Sato 2012 | Not comparator of interest: no comparator |

| Seeger 2000 | Not outcome of interest or not reported separately: pharmacokinetics |

| Simon 2005 | Not intervention of interest: not retinoic acid |

| Simon 2011 | Not comparator of interest: all participants received retinoic acid |