Abstract

Background

People with severe mental illness show high rates of unemployment and work disability, however, they often have a desire to participate in employment. People with severe mental illness used to be placed in sheltered employment or were enrolled in prevocational training to facilitate transition to a competitive job. Now, there are also interventions focusing on rapid search for a competitive job, with ongoing support to keep the job, known as supported employment. Recently, there has been a growing interest in combining supported employment with other prevocational or psychiatric interventions.

Objectives

To assess the comparative effectiveness of various types of vocational rehabilitation interventions and to rank these interventions according to their effectiveness to facilitate competitive employment in adults with severe mental illness.

Search methods

In November 2016 we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsychINFO, and CINAHL, and reference lists of articles for randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews. We identified systematic reviews from which to extract randomised controlled trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials and cluster‐randomised controlled trials evaluating the effect of interventions on obtaining competitive employment for adults with severe mental illness. We included trials with competitive employment outcomes. The main intervention groups were prevocational training programmes, transitional employment interventions, supported employment, supported employment augmented with other specific interventions, and psychiatric care only.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently identified trials, performed data extraction, including adverse events, and assessed trial quality. We performed direct meta‐analyses and a network meta‐analysis including measurements of the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA). We assessed the quality of the evidence for outcomes within the network meta‐analysis according to GRADE.

Main results

We included 48 randomised controlled trials involving 8743 participants. Of these, 30 studied supported employment, 13 augmented supported employment, 17 prevocational training, and 6 transitional employment. Psychiatric care only was the control condition in 13 studies.

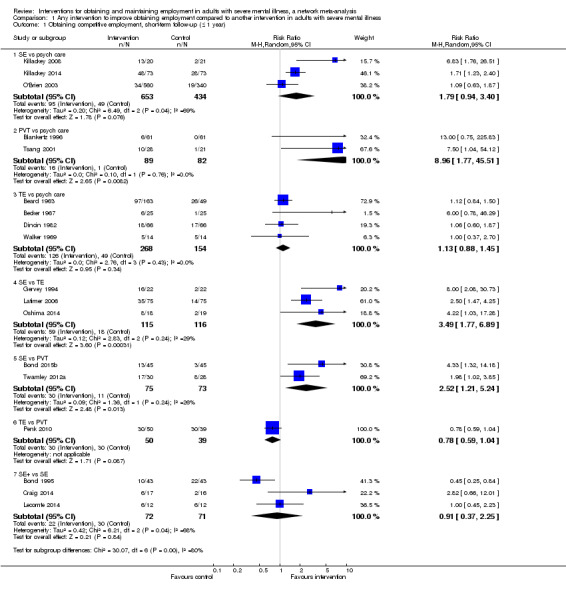

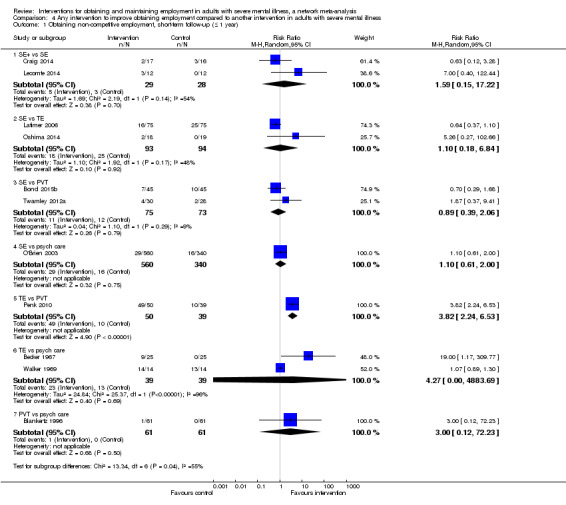

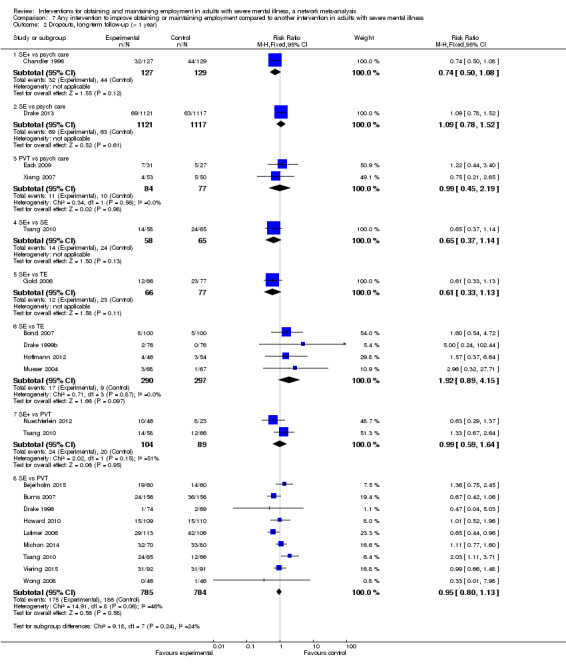

Direct comparison meta‐analysis of obtaining competitive employment

We could include 18 trials with short‐term follow‐up in a direct meta‐analysis (N = 2291) of the following comparisons. Supported employment was more effective than prevocational training (RR 2.52, 95% CI 1.21 to 5.24) and transitional employment (RR 3.49, 95% CI 1.77 to 6.89) and prevocational training was more effective than psychiatric care only (RR 8.96, 95% CI 1.77 to 45.51) in obtaining competitive employment.

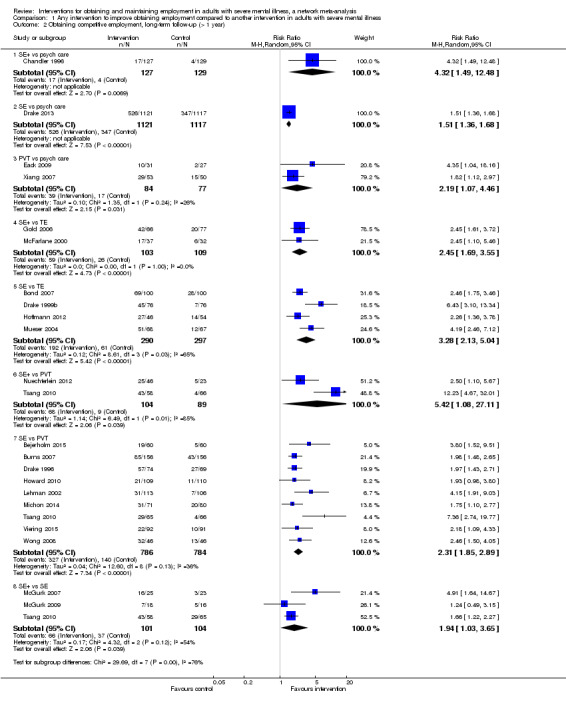

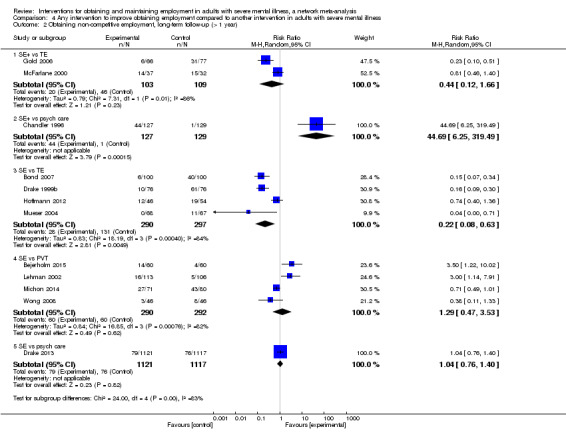

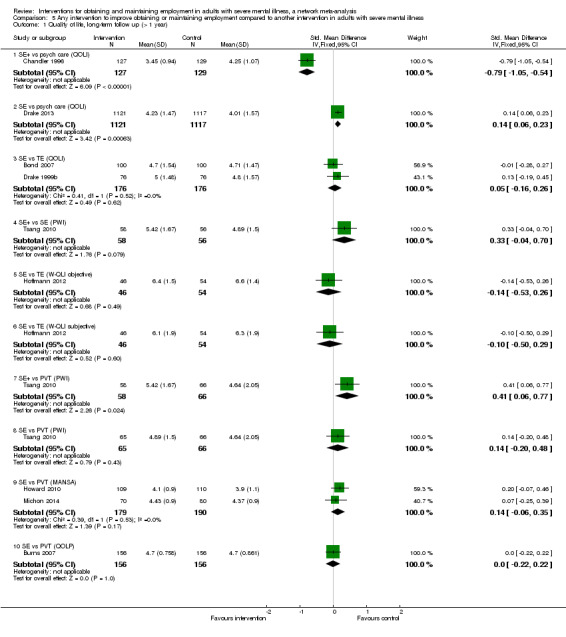

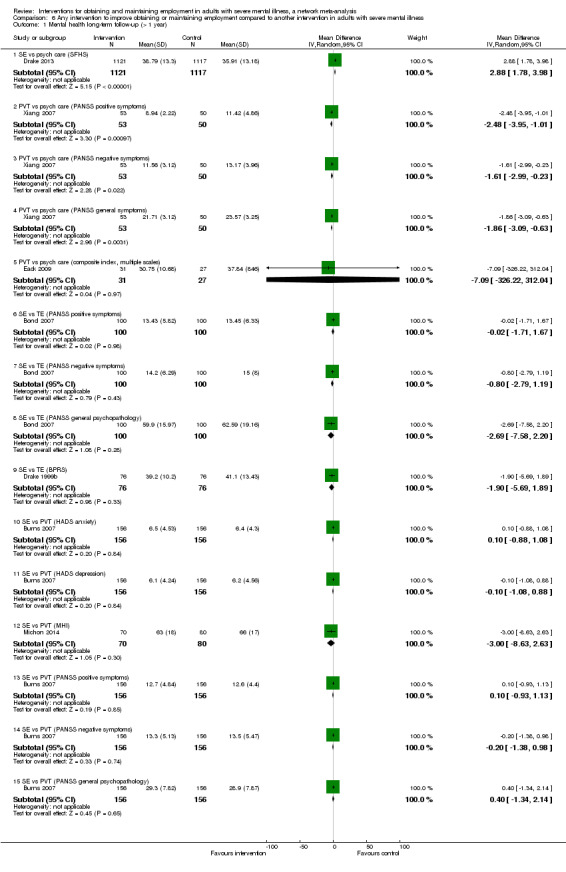

For the long‐term follow‐up direct meta‐analysis, we could include 22 trials (N = 5233). Augmented supported employment (RR 4.32, 95% CI 1.49 to 12.48), supported employment (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.68) and prevocational training (RR 2.19, 95% CI 1.07 to 4.46) were more effective than psychiatric care only. Augmented supported employment was more effective than supported employment (RR 1.94, 95% CI 1.03 to 3.65), transitional employment (RR 2.45, 95% CI 1.69 to 3.55) and prevocational training (RR 5.42, 95% CI 1.08 to 27.11). Supported employment was more effective than transitional employment (RR 3.28, 95% CI 2.13 to 5.04) and prevocational training (RR 2.31, 95% CI 1.85 to 2.89).

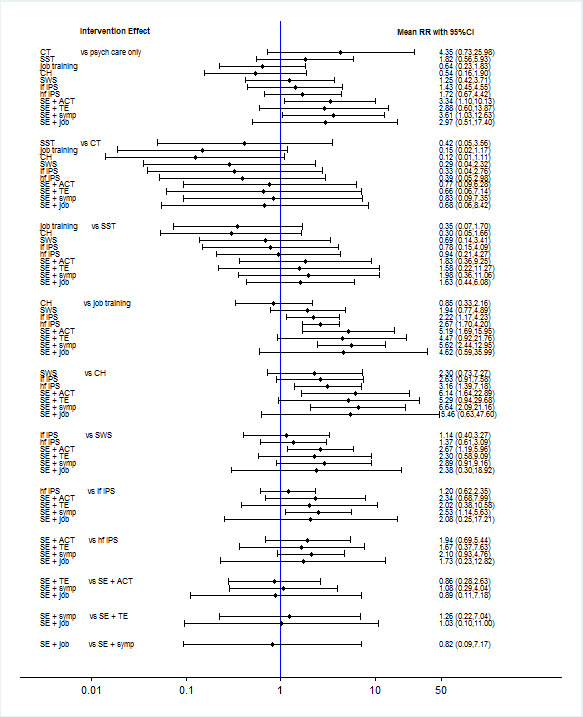

Network meta‐analysis of obtaining competitive employment

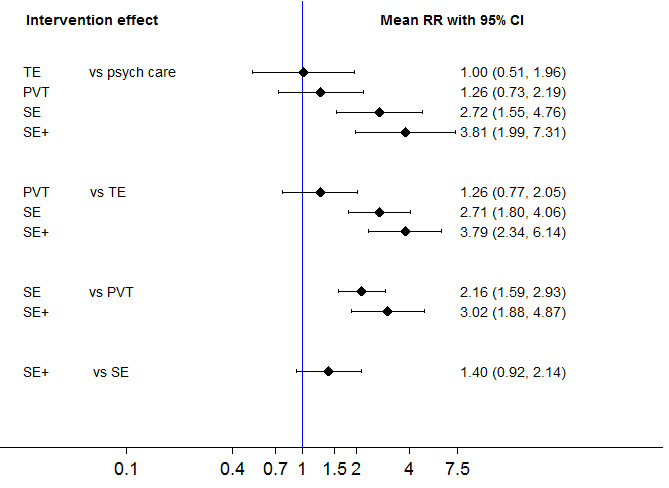

We could include 22 trials with long‐term follow‐up in a network meta‐analysis.

Augmented supported employment was the most effective intervention versus psychiatric care only in obtaining competitive employment (RR 3.81, 95% CI 1.99 to 7.31, SUCRA 98.5, moderate‐quality evidence), followed by supported employment (RR 2.72 95% CI 1.55 to 4.76; SUCRA 76.5, low‐quality evidence).

Prevocational training (RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.19; SUCRA 40.3, very low‐quality evidence) and transitional employment were not considerably different from psychiatric care only (RR 1.00,95% CI 0.51 to 1.96; SUCRA 17.2, low‐quality evidence) in achieving competitive employment, but prevocational training stood out in the SUCRA value and rank.

Augmented supported employment was slightly better than supported employment, but not significantly (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.92 to 2.14). The SUCRA value and mean rank were higher for augmented supported employment.

The results of the network meta‐analysis of the intervention subgroups favoured augmented supported employment interventions, but also cognitive training. However, supported employment augmented with symptom‐related skills training showed the best results (RR compared to psychiatric care only 3.61 with 95% CI 1.03 to 12.63, SUCRA 80.3).

We graded the quality of the evidence of the network ranking as very low because of potential risk of bias in the included studies, inconsistency and publication bias.

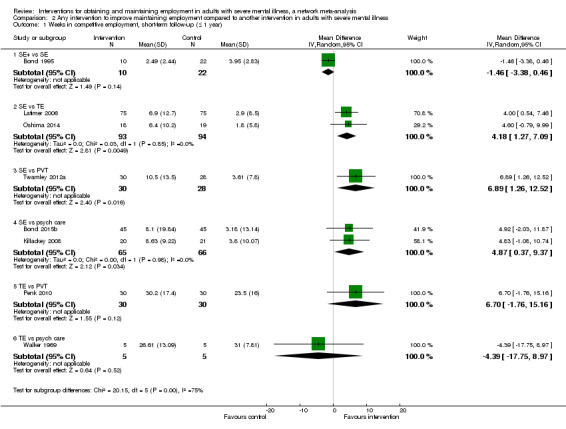

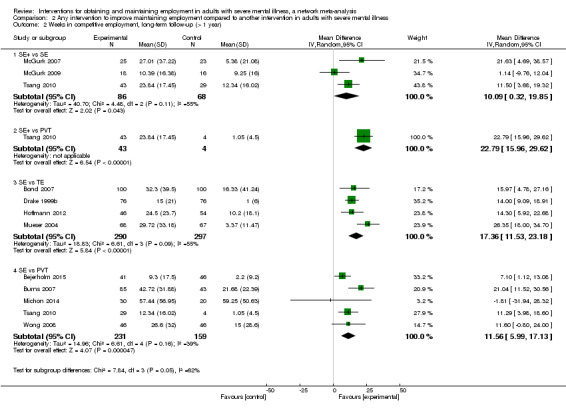

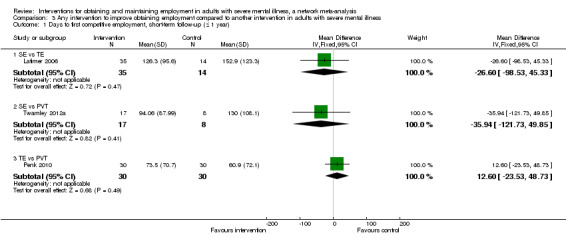

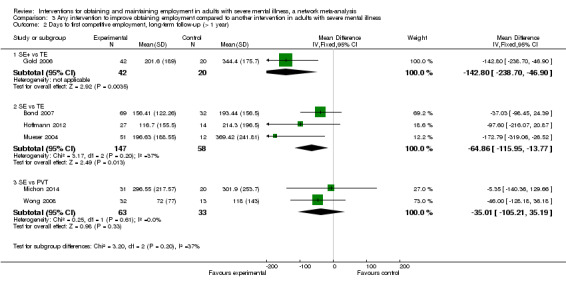

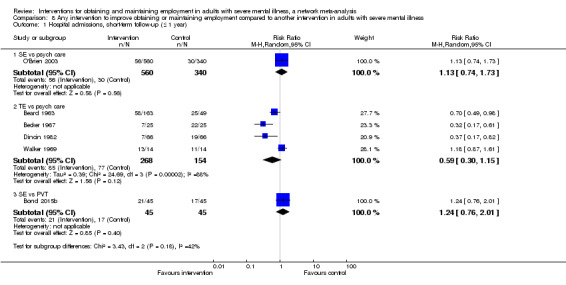

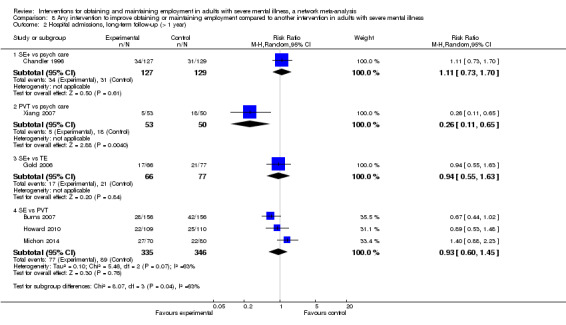

Direct meta‐analysis of maintaining competitive employment

Based on the direct meta‐analysis of the short‐term follow‐up of maintaining employment, supported employment was more effective than: psychiatric care only, transitional employment, prevocational training, and augmented supported employment.

In the long‐term follow‐up direct meta‐analysis, augmented supported employment was more effective than prevocational training (MD 22.79 weeks, 95% CI 15.96 to 29.62) and supported employment (MD 10.09, 95% CI 0.32 to 19.85) in maintaining competitive employment. Participants receiving supported employment worked more weeks than those receiving transitional employment (MD 17.36, 95% CI 11.53 to 23.18) or prevocational training (MD 11.56, 95% CI 5.99 to 17.13).

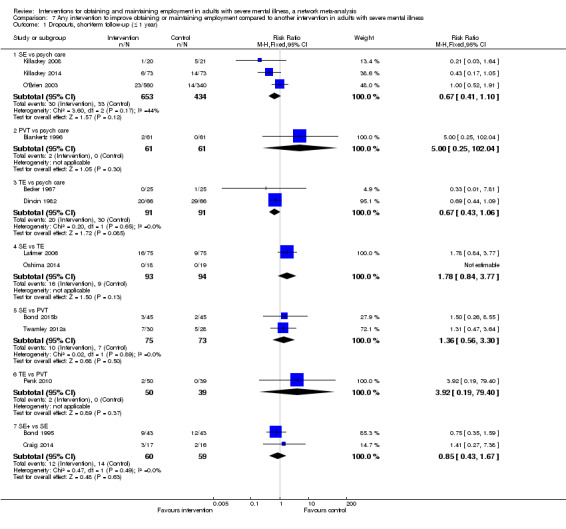

We did not find differences between interventions in the risk of dropouts or hospital admissions.

Authors' conclusions

Supported employment and augmented supported employment were the most effective interventions for people with severe mental illness in terms of obtaining and maintaining employment, based on both the direct comparison analysis and the network meta‐analysis, without increasing the risk of adverse events. These results are based on moderate‐ to low‐quality evidence, meaning that future studies with lower risk of bias could change these results. Augmented supported employment may be slightly more effective compared to supported employment alone. However, this difference was small, based on the direct comparison analysis, and further decreased with the network meta‐analysis meaning that this difference should be interpreted cautiously. More studies on maintaining competitive employment are needed to get a better understanding of whether the costs and efforts are worthwhile in the long term for both the individual and society.

Plain language summary

Helping adults with severe mental illness get a job and to keep it, a network meta‐analysis

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this review was to find out if it is possible to help adults with severe mental illness get a job and to keep it.

People with severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, are more often unemployed. However, these people still often have a desire to work. There are many ways to try and help them obtain a competitive job. People with severe mental illness used to be placed in sheltered employment or they were enrolled in prevocational training, before searching for competitive work. Now there are also interventions focusing directly on finding a job quickly, with ongoing support to keep the job. This is known as supported employment. Recently, there has been a growing interest in combining supported employment with other prevocational or psychiatric interventions.

Key messages

Supported employment and augmented supported employment are more effective than the other interventions in obtaining and maintaining competitive employment for people with severe mental illness without increasing the risk for hospital admissions. The difference in effectiveness between supported employment and augmented supported employment is small. Future research should evaluate the cost‐effectiveness of augmented supported employment compared to supported employment only.

What was studied in the review?

We included 48 randomised controlled trials involving 8743 participants. The interventions included prevocational training, transitional employment, such as sheltered jobs, supported employment, supported employment augmented with other specific interventions or psychiatric care only. We used the data from these studies about the number of participants who obtained a competitive job and the number of weeks they worked. Through a direct comparison meta‐analysis and a network meta‐analysis we assessed the difference in effectiveness between all interventions, and ranked these accordingly.

What are the results of the review?

Supported employment and augmented supported employment are more effective than prevocational training, transitional employment or psychiatric care only in obtaining employment in both types of meta‐analysis. In the direct comparison meta‐analysis prevocational training was also more effective than psychiatric care only. Augmented supported employment shows slightly better results than supported employment alone, again in both types of meta‐analysis. However, this result was less clear in the network meta‐analysis. In the subgroup analysis supported employment with symptom‐related skills training showed the best results. The results are based on moderate‐ to very low‐quality evidence, meaning that the results of future studies could change our conclusions. Augmented supported employment is more effective than prevocational training and supported employment in maintaining competitive employment in the direct comparison meta‐analysis. The results favour supported employment compared to transitional employment in maintaining competitive employment.

Overall, we did not find any differences between interventions in the risk of participants dropping out or hospital admissions.

How up to date is this review?

We searched for studies that had been published up to 11 November 2016.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings of network meta‐analysis.

|

Patient or population: adults with severe mental illness Settings: (community) psychiatric care/mental health services Interventions/comparisons: interventions for obtaining competitive employment: augmented supported employment, supported employment. pre‐vocational training, transitional employment, psychiatric care only | ||||||

| Comparison | Illustrative comparative risksa (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | SUCRA | No of participants (studies with direct evidence) b | Quality of the evidence (GRADE)c | |

| Assumed likelihood with control intervention | Corresponding likelihood with intervention | |||||

| Outcome: Number of participants who obtained competitive employment (follow up > 1 year) | ||||||

| Augmented supported employment vs. psychiatric care only |

187 per 1000 (18.7%) |

712 per 1000 (372 to 1366) |

RR 3.81 (1.99 to 7.31) | 98.5% | 256 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

| Supported employment vs. psychiatric care only |

187 per 1000 (18.7%) |

509 per 1000 (290 to 890) |

RR 2.72 (1.55 to 4.76) |

76.5% | 2238 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 |

| Pre‐vocational training vs. psychiatric care only |

187 per 1000 (18.7%) |

236 per 1000 (136 to 410) |

RR 1.26 (0.73 to 2.19) |

40.3% | 161 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 |

| Transitional employment vs. psychiatric care only |

187 per 1000 (18.7%) |

187 per 1000 (95 to 367) |

RR 1.00 (0.51 to 1.96) |

17.2% | 0 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 4 |

| Augmented supported employment vs. transitional employment |

223 per 1000 (22.3%) |

845 per 1000 (522 to 1369) |

RR 3.79 (2.34 to 6.14) |

212 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5 | |

| Supported employment vs. transitional employment |

223 per 1000 (22.3%) |

604 per 1000 (401 to905) |

RR 2.71 (1.80 to 4.06) |

87 (4 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate6 | |

| Pre‐vocational training vs. transitional employment |

223 per 1000 (22.3%) |

281 per 1000 172 to 457) |

RR 1.26 (0.77 to 2.05) |

0 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low7 | |

| Augmented supported employment vs. pre‐vocational training |

263 per 1000 (26.3%) |

794 per 1000 (494 to 1280) |

RR 3.02 (1.88 to 4.87) |

193 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low8 | |

| Supported employment vs prevocational training |

263 per 1000 (26.3%) |

568 per 1000 (419 to 771) |

RR 2.16 (1.59 to 2.93) |

1569 (9 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low9 | |

| Augmented supported employment vs supported employment only |

457 per 1000 (45.7%) |

640 per 1000 420 to 978) |

RR 1.40 (0.92 to 2.14) |

205 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low10 | |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

a The corresponding likelihood of obtaining employment with intervention (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed likelihood with the control intervention (= median likelihood across studies) and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). b Number of participants in direct comparison only.

c We did not downgrade because of reporting bias as insufficient studies contributed to network treatment estimates to allow us to draw meaningful conclusions.

1 We downgraded one level due to study limitations (majority moderate risk of bias studies).

2 We downgraded one level due to study limitations (majority moderate risk of bias studies) and one level due to inconsistency (predictive interval for intervention effect includes effect that would have different interpretation and loop inconsistency).

3 We downgraded one level due to study limitations (majority moderate risk of bias studies), one level because of inconsistency (predictive interval for intervention effect includes effect that would have different interpretations) and one level for imprecision (CIs include values favouring either intervention).

4 We downgraded one level due to study limitations (majority moderate risk of bias studies) and one level because of imprecision (CIs include values favouring either intervention).

5 We downgraded two levels due to study limitations (majority high risk of bias studies).

6 We downgraded one level due to study limitations (majority moderate risk of bias studies).

7 We downgraded one level due to study limitations (majority moderate risk of bias studies) and one level because of imprecision (confidence intervals include values favouring either intervention).

8 We downgraded one level due to study limitations (majority moderate risk of bias studies) and one level because ofinconsistency (moderate level of heterogeneity).

9 We downgraded one level due to study limitations (majority moderate risk of bias studies), one level due to inconsistency (predictive interval for intervention effect includes effect that would have different interpretation and loop inconsistency) and one level because of detected publication bias (small study effects).

10 We downgraded one level due to study limitations (majority moderate risk of bias studies) and one level because of imprecision (confidence intervals include values favouring either intervention). CI: confidence interval RR: risk ratio

Background

Description of the condition

Mental illness is responsible for a significant loss of potential labour supply, high rates of unemployment, and a high incidence of sickness absence and reduced productivity at work (OECD 2012). Today in OECD countries, between one‐third and one‐half of all new disability benefit claims are for reasons of mental health, and among young adults that proportion goes up to over 70% (OECD 2012). Among people with severe mental illness the rates of work disability and unemployment are even higher. In the USA and the UK the employment rates for severely mentally ill people are reported to be less than 20% (Marwaha 2007; Salkever 2007). However, many people with severe mental illness do often have a desire to obtain some form of employment or participation in society (Hatfield 1992; McQuilken 2003; Mueser 2001).

There has been lack of consensus about a specific definition of severe mental illness (Delespaul 2013; Ruggeri 2000). Generally, severe mental illness is defined by three tangible indicators: diagnosis, disability and duration. The predominant diagnoses are psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorders and major depression with psychotic features. Other psychiatric diagnoses such as personality disorders and severe concurrent diagnoses (psychiatric diagnosis with substance abuse) are sometimes included within the category of severe mental illness. The duration of the disorder suggests a persistence of mental health problems over time (e.g. frequency and intensity of use of psychiatric services). People with severe mental illness experience difficulties with functioning in one or more areas of daily life (Corbière 2013).

It's well known that work contributes to the quality of life of people in general and also for those with severe mental illness (Gold 2014; Lötters 2013; Schuring 2013). Competitive employment offers multiple advantages such as enhancing income, increasing self‐esteem, developing social skills, improvement of symptoms, decreasing number of hospital admissions and de‐stigmatisation (Bond 2001a; Burns 2009; Corbière 2009; Gold 2014; Mueser 2014; Perkins 2009), whereas unemployment can lead to social isolation with subsequent economic and social deprivation, which further reduces the probability of obtaining a job (Carlier 2013). Competitive employment means work in the competitive labour market that is performed on a full‐time or part‐time basis in an integrated setting; and for which an individual is compensated at or above the minimum wage, but not less than the customary or usual wage paid by the employer for the same or similar work performed by individuals who are not disabled. An integrated setting means a setting typically found in the community in which an individual with the most severe disabilities interacts with non‐disabled individuals (34 C.F.R. § 363.3(b) 2015).

Description of the intervention

In the past, people with severe mental illness were treated for long periods, or their whole lives, in hospital settings. Since the 1970s, a lot has changed. People with severe mental illness are increasingly living in the community supported by multidisciplinary community treatment teams, such as assertive community treatment or intensive case management. These are intensive mental health programme models that provide clinical and case management services. These programmes have substantially reduced psychiatric hospital use, increased housing stability, and moderately improved symptoms and subjective quality of life (Dieterich 2010; Marshall 1998). Along with this evolution in psychiatric care, the perspective on vocational participation has also changed. In the last decades, many vocational rehabilitation programmes have been developed and evaluated for people with severe mental illness. Vocational rehabilitation programmes are designed to help people with disabilities to obtain and maintain employment. Initially, people with severe mental illness, who had a desire to work, were placed in sheltered employment or enrolled in prevocational training and volunteer work before competitive employment. Competitive employment was considered to be too stressful. Caretakers preferred a stepwise approach so people could acquire certain skills before involvement in competitive employment.

In the mid 1980s, a new vocational rehabilitation approach emerged, known as supported employment (Crowther 2001). Supported employment emphasises a rapid search for a competitive job, with ongoing support provided as needed to get and keep the job (Drake 1999a). This method seems to be more effective in employment outcomes compared to prevocational training (Crowther 2001; Kinoshita 2013), however this intervention is not yet in wide use (OECD 2012). An important reason for this could be that the widespread implementation encounters too many financial or organisational barriers (Bond 2012a). Over the last couple of years, there has been a growing interest in strengthening supported employment with other prevocational skills training programmes such as social skills training. This method is called augmented supported employment or integrated supported employment (Boycott 2012).

At the moment the following interventions are in use.

Prevocational training

Prevocational training is a stepwise approach in which participants get trained before being employed. This approach is also called 'train, then place' or 'traditional vocational rehabilitation'. These programmes often use training classes, workshops, assessments or counselling. Training is provided in generic work skills or personal development such as self‐esteem, assertiveness and stress management (Corrigan 2001; Loveland 2007). There are also specific training programmes that focus on improvement of social or cognitive skills (Corbière 2009).

Social skills training

Social skills training consists of behavioural training focused on specific situations, problems, and activities. The ultimate goal of this training is the generalisation of learned skills to community‐based activities with improved functioning. Social skills training utilises principles from learning theory to improve social functioning by working with people to remediate problems in activities of daily living, leisure, relationships, or employment. There are two forms of social skills training: the basic model and the social problem‐solving model. In the basic model, complex social repertoires are broken down into simpler steps, subjected to corrective learning, practised through role playing, and applied in natural settings. The social problem‐solving model focuses on improving impairments in information processing that are assumed to be the cause of social skills deficits (Bellack 1993). In this model, social skills training is used to increase skills acquisition and reduce psychiatric symptoms in people with severe mental illness. Examples of social skills that are trained are assertiveness, use and interpretation of verbal and non‐verbal communication, and daily living skills (Dilk 1996; Kopelowicz 2006; Kurtz 2008).

Cognitive training

Cognitive functioning is often impaired in people with severe mental illness and is associated with poor vocational functioning (McGurk 2014). The terms 'cognitive training', 'cognitive remediation' and 'cognitive rehabilitation' are used both interchangeably and inconsistently in the literature and in clinical practice. These interventions are based on behavioural training and aim to improve cognitive processes (attention, memory, executive function, social cognition or meta‐cognition) with the goal of durability and generalisation. This can positively affect community functioning (Keshavan 2014; Wykes 2011).

Transitional employment

Transitional employment refers to segregated programmes designed to help individuals with disabilities who are viewed as not (yet) capable of working in a competitive employment setting. Usually transitional employment programmes are run by non‐profit organisations that receive funding through state and federal sources (Boardman 2003; Krainski 2013). Transitional employment can also be used as a first step to more gainful forms of employment.

Sheltered workshop

A transitional sheltered workshop refers to a workplace that provides a segregated working environment where people with a mental or physical disability can acquire job skills and vocational experience. It is hoped that this training and experience will assist them to acquire the skills necessary for competitive employment. There are also extended sheltered workshop programmes, typically designed to be long‐term placements for individuals who are expected not to be able to work in the community. Sheltered workshops are authorised to employ people with disabilities at sub‐minimum wages (Gervey 1994; Hsu 2009; Migliore 2010).

Social enterprise

A social enterprise/firm is a semi‐commercial business that offers paid employment at competitive rates for people who have difficulty integrating into the normal labour force (Boardman 2003; Gilbert 2013; Latimer 2005). Some of them are consumer‐run businesses (Latimer 2005). In an integrated working environment groups of clients are trained and supervised among both disabled and non‐disabled workers (Corbière 2009). A recent survey in the UK showed that over 50% of the employees were diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (Gilbert 2013). People with mental illness experience social enterprises as providing a flexible environment that promotes feelings of belonging, success, competence and individuality (Svanberg 2010). Through working in a social enterprise people can gain access to other more rewarding job opportunities in the labour market but can also increase psychosocial outcomes (Savio 1993; Vilotti 2014).

The Clubhouse model

A clubhouse is a building run by clients with severe mental illness and staff, where clients meet for social activity, mutual support and graded work experience. There are now approximately 300 clubhouses in various countries around the world, many of which are accredited by the International Center for Clubhouse Development (ICCD). The Clubhouse approach involves a period of preparation before clients attempt to return to competitive employment. This period of preparation consists of two stages: the work‐ordered day and transitional employment (Beard 1982). The work‐ordered day refers to a process whereby clients join work crews (working side by side with staff and other clients) that take responsibility for managing and maintaining the clubhouse. Work crews are a means to prepare for the next stage called transitional employment (Bond 1999; Norman 2006). Clients are discouraged from seeking competitive employment until they have achieved success in transitional employment, and are free to return to work crews at any time (Bilby 1992).

Supported employment

Supported employment programmes attempt to help adults with severe mental illness obtain competitive employment quickly and provide them with ongoing support to maintain employment (Bond 2001a).

Individual placement and support

The most clearly described and widely researched supported employment model is Individual Placement and Support (IPS). In this model, help is provided with looking for a job and, once employed, support is provided indefinitely. The services are integrated with mental health treatment services.

Individual placement and support is based on eight principles: (1) focus on competitive employment outcomes, (2) zero exclusion: open to anyone with severe mental illness who wants to work, (3) rapid job search, (4) attention to client preferences in services and job searches, (5) employment specialists systematically develop relationships with employers based upon client preferences, (6) time‐unlimited and individualised supports, (7) employment services are integrated with mental health treatment services, and (8) clients receive personalised benefit counselling (Becker 1993; Drake 2012).

Bond and colleagues studied the effectiveness of fidelity to the key principles of IPS (see above), and found evidence for the contribution of all these principles in helping people obtain and retain work (Bond 1999; Bond 2004).

Augmented supported employment

Augmented supported employment is supported employment augmented with other interventions, which may further increase employment outcomes. Any type of intervention can be used in combination with augmented supported employment; for example cognitive skills training with supported employment (Loveland 2007; McGurk 2004; Tsang 2009).

Psychiatric care only

Psychiatric care only is defined as usual psychiatric care for individuals with severe mental illness without any specific vocational component. Usually psychiatric care includes medication, supportive psychotherapy and case management. A well‐studied specific model of psychiatric care is assertive community treatment (ACT).

Assertive community treatment

ACT is a 24‐hour team‐based approach that provides clinical and case management to individuals with severe mental illness in the community. This multidisciplinary team consists of mental health care professionals such as case managers, a psychiatrist, psychiatric nurses, social workers and occupational therapists. The caseload is low, which enables intensive and frequent contacts. ACT teams practise 'assertive outreach', meaning that they continue to contact and offer services to reluctant or uncooperative people. They also place particular emphasis on medication compliance. In addition, ACT teams also provide help with housing, finances, activities of daily living, interpersonal relationships and employment (Bond 2001b; Stein 1998).

A number of studies, including meta‐analysis, demonstrate significant advantages of assertive community treatment in reducing hospital admissions, improving psychiatric symptoms and quality of life and increasing independent living (Dieterich 2010; Marshall 1998).

How the intervention might work

Prevocational training assumes that people with severe mental illness need to learn certain skills before they can hold a competitive job. In a protective environment, and in a stepwise way, people with severe mental illness are gradually exposed to 'normal' working conditions and routines. For some people, working in a competitive job is not possible (or not preferred by people with a severe mental illness) and working in a sheltered workplace may be their best possible option. These types of interventions focus on helping and empowering the individual.

In contrast, supported employment stands for rapid job search without extended preparation, but with prolonged intensive supervision on the job if needed. Another key component of supported employment is the integration of employment services and a mental health treatment team (Bond 2004). Therefore, it is also important that the mental health professionals agree on work rehabilitation as a treatment outcome. In addition, the job coach has an important role by empowering the employer in providing a healthy and stimulating workplace for the individual.

Although supported employment seems to be more effective than prevocational training in obtaining and maintaining competitive employment (Crowther 2001; Kinoshita 2013), there still seems to be room for improvement. A variety of factors, such as cognitive impairment or social difficulties, have been identified as contributing to brief job tenure and unsuccessful job terminations (Becker 1998; McGurk 2004). Consequently there is a growing interest in combining supported employment with other vocational interventions, such as social skills training or cognitive training (Bell 2008a; McGurk 2005; Mueser 2005; Tsang 2009). A certain number of people with severe mental illness may need a vocational rehabilitation process that combines elements from different types of interventions, focusing both on empowering the individual and on the future employer and working environment.

From research in occupational health settings, we know that a case manager who functions as an intermediary between the curative treatment setting and the work setting can decrease time to return to work (Schandelmaier 2012). This case manager may be a return‐to‐work co‐ordinator, an employment specialist, an occupational health specialist or the employer himself. It is possible that this element of case management as part of supported employment is the most effective aspect of this intervention. Corbière 2014 showed that SE employment specialists who use a client‐centred approach and have good relationships with employers and supervisors, have more vocational successes. A more recent study again confirmed that employment specialist skills are important to predict job acquisition (Corbière 2016).

Why it is important to do this review

Several systematic reviews have compared supported employment to one or more forms of prevocational training (e.g. Crowther 2001; Kinoshita 2013; Twamley 2003). The conclusions of these reviews suggest that supported employment may be more effective in obtaining competitive employment and may also increase length of employment. However, in the most recent systematic review (Kinoshita 2013), the authors considered the quality of evidence as very low, due to the small number of studies that contributed to the primary outcome (days in competitive employment). A large amount of data were considerably skewed, and therefore the authors excluded them from their meta‐analysis. There also appeared to be an overall high risk of bias in the individual studies.

In addition, not all forms of supported employment and prevocational training were compared, and therefore it remains somewhat unclear which particular form of supported employment or prevocational training actually has the largest effect on obtaining and maintaining work. Furthermore, not all types of interventions were directly compared with each other, and we do not know what the most effective components of these sometimes complex interventions are. Recently, new studies regarding supported employment enhanced with other prevocational interventions have been published but these results have not yet been included in the existing systematic reviews. It would be interesting to compare these results to those obtained with other types of interventions.

A network meta‐analysis enables us to perform direct and indirect comparisons between all types of interventions, and this may help clarify which components are particularly effective. We aim to present a ranking of these various types of vocational rehabilitation interventions based on their effectiveness. This ranking would be very helpful for mental and occupational healthcare professionals and policymakers interested in supporting people with severe mental illness to obtain and also to maintain employment.

Objectives

To assess the comparative effectiveness of various types of vocational rehabilitation interventions and to rank these interventions according to their effectiveness to facilitate competitive employment in adults with severe mental illness.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐randomised controlled trials, that assessed the effects of vocational rehabilitation interventions in people with severe mental illness. We excluded quasi‐experimental studies.

Types of participants

We included trials with adults aged between 18 and 70 years who had been diagnosed with severe mental illness. We defined severe mental illness as schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, depression with psychotic features or other long‐lasting psychiatric disorders, with a disability in social functioning or participating in society, such as personality disorder, severe anxiety disorder, post‐traumatic stress disorder, major depression or autism with a duration of at least two years. Study participants had to be unemployed due to severe mental illness.

We excluded data from analyses where participants had a problem with substance abuse without any other mental disorder, or they had mental retardation, dementia, other neurocognitive disorders or terminal illness.

Types of interventions

We included trials of all types of vocational rehabilitation compared to each other or to no intervention or psychiatric care only.

We used the following classification of interventions and subgroups:

Prevocational training

Job‐related skills training

-

Symptom‐related skills training

Cognitive training

Social skills training

Transitional employment

Sheltered workshop

Social enterprise

Clubhouse model

Supported employment

Low‐fidelity IPS/not IPS

High‐fidelity IPS

Augmented supported employment

Supported employment + job‐related skills training

Supported employment + symptom‐related skills training

Supported employment + sheltered employment

Psychiatric care only

ACT

Types of outcome measures

We included studies only if they measured the primary outcome: percentage or number of participants who obtained competitive employment.

Primary outcomes

Percentage or number of participants who obtained competitive employment

The primary outcome of our review was obtaining competitive employment. This means work in the competitive labour market for which an individual is compensated at or above minimum wage.

We included all follow‐up times and categorised these as short‐term follow‐up if less than or up to 12 months, and long‐term follow‐up if longer than 12 months.

Secondary outcomes

Employment

Number of weeks in competitive employment

Number of days to first competitive employment

Percentage of participants who obtained non‐competitive employment (such as employment in a sheltered workplace or volunteer work)

Clinical outcomes

Quality of life (e.g. QOLI) (Lehman 1988)

Mental health (psychiatric symptoms) (e.g. PANSS) (Kay 1987)

Adverse events

Dropouts

Hospital admissions

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

First, we searched the following electronic databases from 1970 to 11 November 2016 to identify potentially relevant systematic reviews. We used comprehensive search strategies to find the eligible RCTs.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016 issue 11) via the Cochrane Library

MEDLINE (PubMed)

Embase

PsycINFO

CINAHL

Second, we searched for additional RCTs, which were not yet included in systematic reviews. We searched the same databases.

We developed two electronic search strategies by combining search words for the concepts 'mental disorder', 'return to work' and 'systematic reviews' or 'randomised controlled trial' (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9). We searched with these concepts for reviews and additional RCTs.

We used PubMed's 'My NCBI' (National Center for Biotechnology Information) email alert service for identification of newly published systematic reviews and RCTs using a basic search strategy.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all identified studies for additional potentially relevant studies. Additionally, we consulted domain experts with years of experience in vocational rehabilitation for people with severe mental illness, to identify unpublished materials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

First, we focused on the selection of systematic reviews and then we continued with the selection of additional RCTs. Two authors (YS, FS) independently screened the titles and abstracts of publications identified by both search strategies. We discarded all studies that were not applicable according to our inclusion criteria. We then obtained the full text of the remaining references. Two authors (YS, FS) independently decided whether the reviews and RCTs met the inclusion criteria and classified the different types of interventions. We resolved disagreements through discussion. In case of persistent disagreement we consulted a third author (JM).

Data extraction and management

Two authors (YS, JM) extracted data for our meta‐analyses and network meta‐analyses from the individual RCTs that were included in the systematic reviews, and from the additional RCTs that we included. Two authors (YS, JM) independently extracted characteristics and outcome data of the included studies. We resolved disagreements through discussion or with assistance from a third author (FS) when necessary. We used a data collection form that was specifically designed and piloted by the author team. We extracted the following study characteristics:

Methods: study design, total duration of study, study location and setting, year of publication

Participants: number of participants, diagnosis, duration of mental illness, inclusion and exclusion criteria, gender, mean age, ethnicity, work history, disability benefits.

Interventions: description of intervention, comparison, duration, intensity.

Outcomes: description of primary and secondary outcomes, moment of measurements.

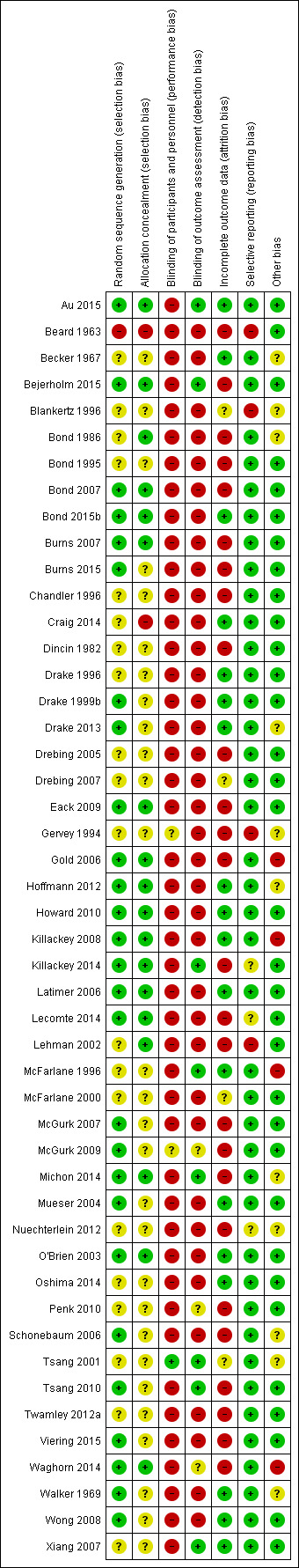

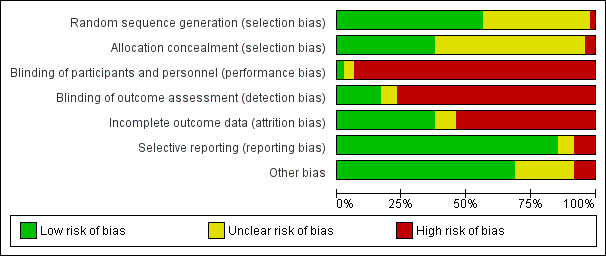

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias to assess the methodological quality of the included trials (Higgins 2011a; Appendix 10).

We assessed the following domains according to this tool:

Sequence generation (selection bias)

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)

Other potential sources of bias

Each of the domains were scored as 'high', 'low' or 'unclear' risk of bias, following criteria outlined in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. We conducted sensitivity analyses by excluding studies we judged to have a high risk of bias in any of the domains listed above.

In case of cluster‐RCTs, we addressed the six components of the 'Risk of bias' tool as well as recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, incorrect analysis and comparability with individually randomised trials.

For RCTs that had previously been included in systematic reviews, one review author (JM) reassessed the risk of bias and ensured that the results agreed with those published. In case of disagreement, JM discussed the risk of bias with another author (YS). We contacted the original author of the systematic review if disagreement persisted.

Two authors (YS, JvM) independently assessed the risk of bias of the RCTs that were not included in an existing systematic review. In case of persistent disagreement, we consulted a third review author (FS). If information was absent for evaluation of the methodological criteria, we contacted the authors of the study with a request to provide additional information.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed dichotomous outcome data as risk ratios (RR) with their 95% confidence interval (CI). Additionaly, we calculated the corresponding risks of the interventions for the primary outcome. For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) when outcome measurements were made on the same scale. If the same outcome was measured with different scales, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) with its 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐RCTs

With cluster‐RCTs we used the group estimates taking into account the cluster randomisation. Studies in which clusters of individuals were randomised to groups, but where the intervention was intended to work at the level of the individual, were analysed taking into account the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC), as was explained in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). When the authors of cluster‐randomised trials did not report ICCs, we assumed an ICC of 0.1 (Higgins 2011b).

Multi‐arm studies

With multi‐arm studies we used the data from all comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted trial authors to obtain missing data. Where this was not possible, or the missing data could have led to serious bias, we explored the impact of including these studies in the overall assessment of results by a sensitivity analysis.

If numerical outcome data such as standard deviations (SDs) or correlation coefficients were missing and they could not be obtained from the study authors, we calculated them from other available statistics such as P values, according to the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

We reported information regarding loss to follow‐up, and we assessed this as a potential risk of bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the standard pairwise meta‐analyses we estimated different heterogeneity variances for each pairwise comparison. We assessed statistically the presence of heterogeneity within each pairwise comparison using the I² statistic (Higgins 2003), where an I² value of 25% to 49% indicates a low degree of heterogeneity, 50% to 75% a moderate degree of heterogeneity and more than 75% indicates a high degree of heterogeneity.

In the network meta‐analyses we assumed a common estimate for the heterogeneity variance across the different comparisons. The assessment of statistical heterogeneity in the entire network is based on the magnitude of the heterogeneity variance parameter estimated from the network meta‐analysis models. We used the Tau² statistic to assess heterogeneity within the comparisons. A Tau² value greater than 1 suggests presence of substantial statistical heterogeneity. We assessed the assumption of transitivity by comparing the distribution of the potential effect modifiers age, gender and working history across the comparisons.

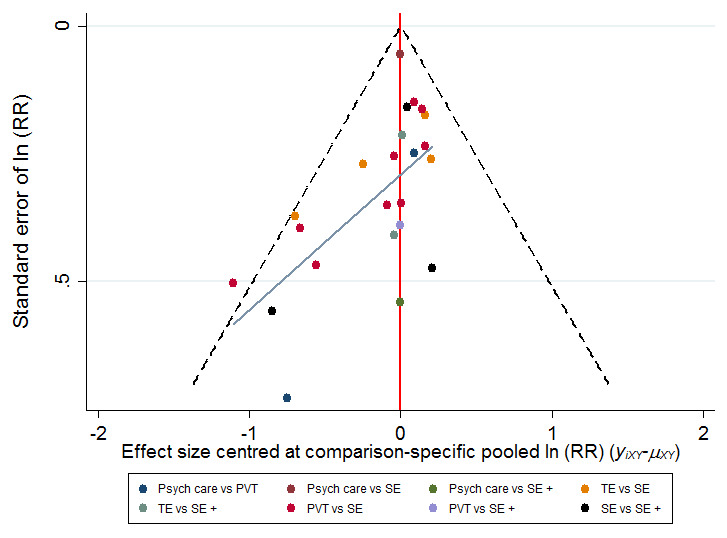

Assessment of reporting biases

We employed a comparison‐adjusted funnel plot for the detection of small study effects (Chaimani 2013). Assymetry in the funnel plot can indicate the presence of small study effects, which can be a result of publication bias.

Data synthesis

Relative treatment effects

We extracted the risk ratio (RR) and reported the RR and the corresponding risks for the primary outcome: number of participants in competitive employment. For one other outcome measure (the number of days or weeks in competitive employment), we used the pooled mean differences (MDs). To avoid confusion about the number of days or weeks, we recalculated this considering the number of hours worked per week. We calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) as a summary statistic when the concepts of being in competitive employment were the same but authors of studies had used different measurement scales.

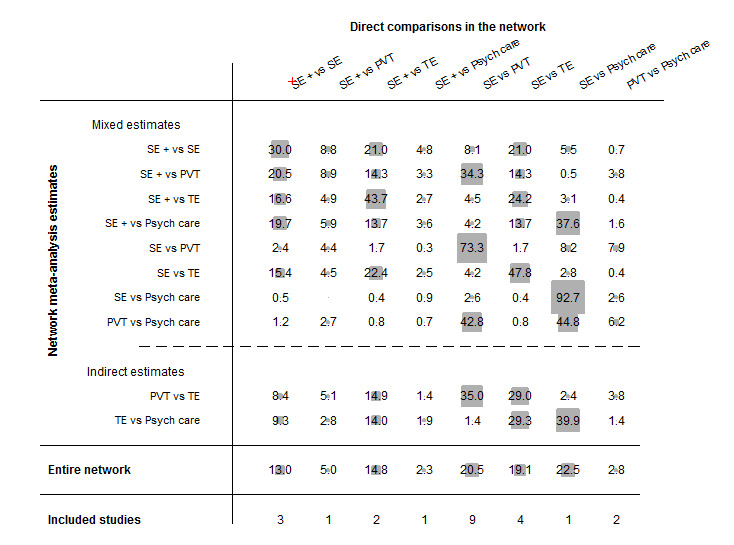

Where comparable data and outcomes existed for different interventions, we performed direct and indirect comparisons using a network analysis and multiple treatments meta‐analysis (White 2011). A network meta‐analysis differs from standard pairwise meta‐analysIs primarily because it uses information across available comparisons to estimate indirect pairwise comparisons. We have presented results from network meta‐analyses as summary relative effect sizes (MD or SMD) for each possible pair of treatments.

Methods for direct and indirect or mixed treatment comparisons

In the direct comparisons, we pooled data from studies we judged to be clinically homogeneous using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) software (RevMan 2014). We performed standard pairwise meta‐analysis for every comparison that contained at least two studies. We used a random‐effects model if studies had high statistical heterogeneity (I² > 75%); otherwise we used a fixed‐effect model.

In the indirect and mixed comparisons, we performed network meta‐analyses in STATA version 13 using the mvmeta command (White 2012) and self‐programmed STATA routines available at http://www.mtm.uoi.gr.

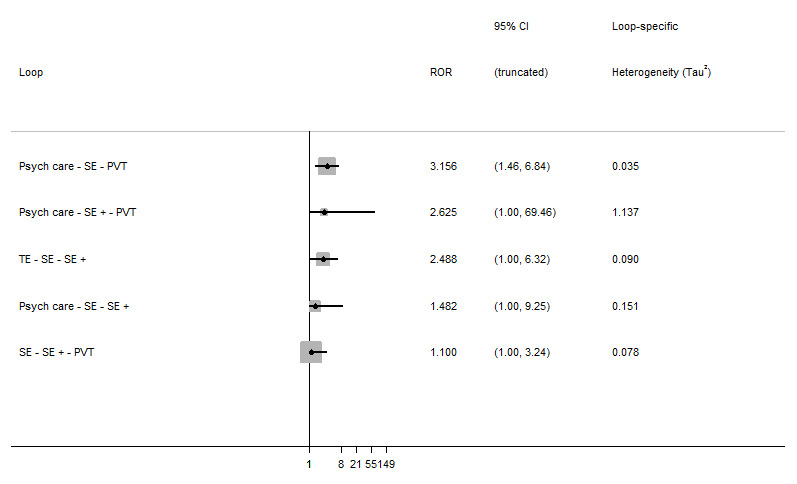

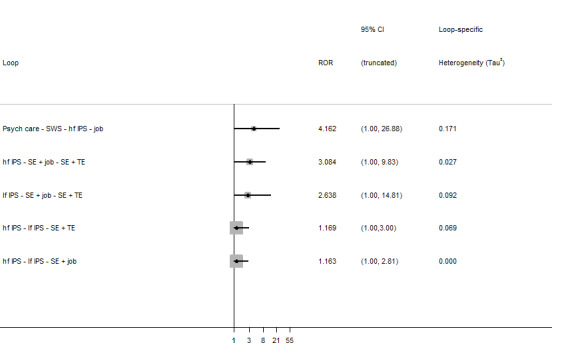

Assessment of statistical inconsistency in network meta‐analysis

To evaluate the presence of inconsistency locally we used the loop‐specific approach. This method evaluates the consistency assumption in each closed loop of the network separately as difference between direct and indirect estimates for a specific comparison in the loop (inconsistency factor). Then, we used the magnitude of the inconsistency factors and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to make inferences about the presence of inconsistency in each loop. We assumed a common heterogeneity estimate within each loop. We present this approach graphically in a forest plot using the ifplot command in STATA.

To check the assumption of consistency in the entire network we used the design‐by‐treatment model as described by Higgins 2012. This method accounts for different sources of inconsistency that can occur when studies with different designs (two‐arm trials versus three‐arm trials) give different results and when there is disagreement between direct and indirect evidence. Using this approach we made inferences about the presence of inconsistency from any source in the entire network based on a Chi² test. We performed the design‐by‐treatment model in STATA using the mvmeta command. Inconsistency and heterogeneity are interwoven: to distinguish between these two sources of variability we employed the I² statistic for inconsistency, as it measures the percentage of variability that cannot be attributed to random error or heterogeneity (within comparison variability).

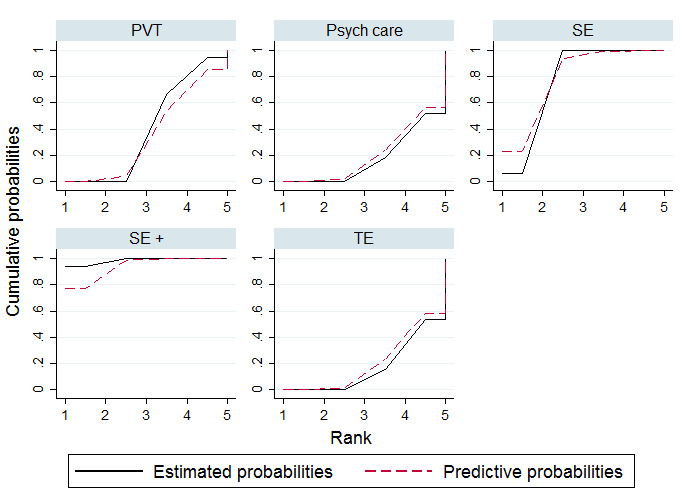

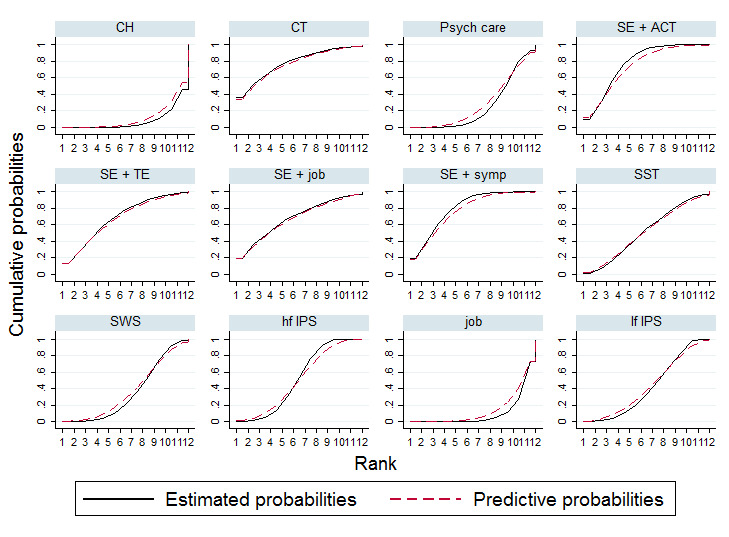

Relative treatment ranking

We also estimated the ranking probabilities for all treatments at each possible rank for each intervention. Then, we obtained hierarchy using the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) and mean ranks (Salanti 2011). SUCRA can also be expressed as a percentage of a treatment that can be ranked first without uncertainty. We performed the SUCRA curves and percentages in STATA using SUCRA commands.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed an intervention subgroup analysis to reduce the possible differences in effectiveness between interventions. Furthermore, we analysed the data to see whether the three possible effect modifiers (age, gender and working history) actually influenced the difference in effect within the network meta‐analysis, focusing on exploring potential inconsistency and heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

If sufficient studies were available, we assessed the effect of excluding studies from the analysis that we had judged to have a high risk of bias. We also checked what the effect was of assumptions that we had made about transitivity.

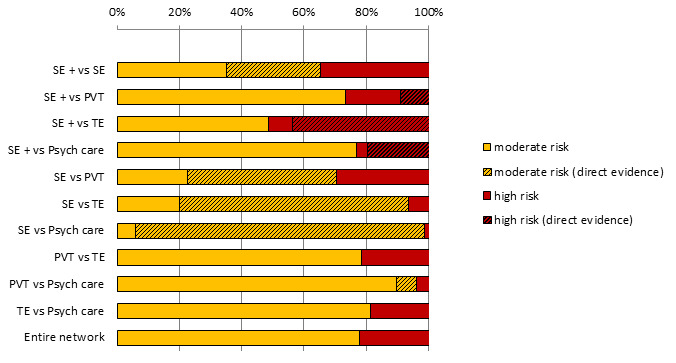

Quality of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach (GRADE Working Group 2013) and the recommendations for network meta‐analyses of Salanti 2014 to assess the quality of evidence for each important comparison. GRADE is used in Cochrane systematic reviews to grade and report quality of evidence within 'Summary of findings' tables. We described the risk of bias as it was assessed within the included reviews. Two authors (YS, FS) assessed the quality criteria independently and resolved any disagreements by discussion.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

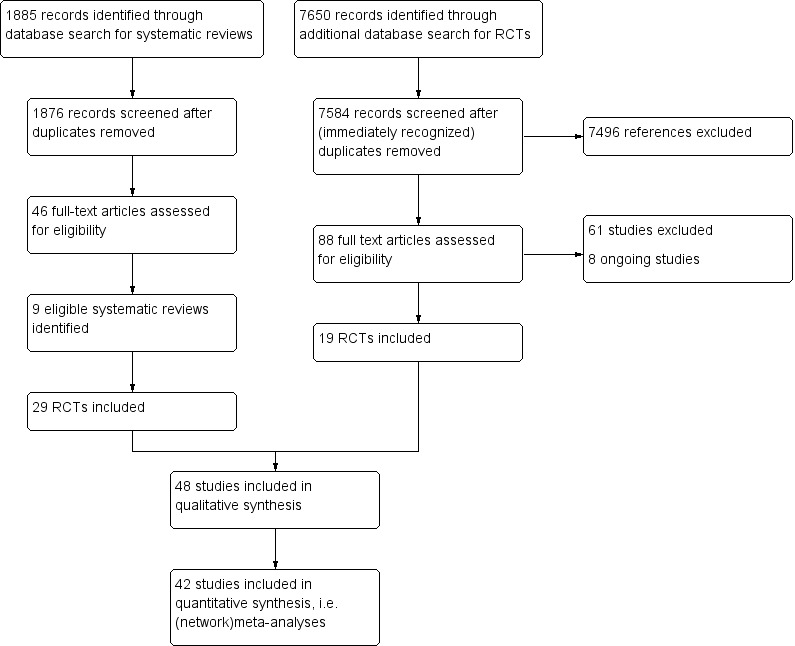

First we searched for relevant systematic reviews to find RCTs. We identified a total of 1885 records and assessed 46 full‐text reviews. Out of nine systematic reviews (Almerie 2015; Arbesman 2011; Bond 2015a; Bouvet 2014; Crowther 2001; Dieterich 2010; Heffernan 2011; Kinoshita 2013; Twamley 2003) we extracted 29 RCTs that fulfilled our eligibility criteria (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). Additionally, we found 7650 records, of which we assessed 88 full‐text RCTs. In total 19 RCTs were also found to be eligible, leading to 48 included RCTs, of which 42 (N = 6712) could be included in the network meta‐analyses and/or meta‐analyses. See Figure 1 for a PRISMA study flow diagram. See Characteristics of excluded studies for the reasons why we excluded studies. Two review authors (YS and FS) checked the eligibility of the identified RCTs. We updated the search on 11 November 2016. Newly published trials will be included in the next version (see Studies awaiting classification). Two new systematic reviews were also identified (Chan 2015; Modini 2016).

1.

PRISMA Study flow diagram

Included studies

See Table 2 and Table 3 for an overview of all included RCTs, their main characteristics, intervention classifications, outcomes and contribution to the analyses.

1. Descriptive details of included studies.

| Study | Country | Follow‐upa | N | Mean age |

Male participants |

Diagnosis (majority) | Working history (majority) |

| Au 2015 | China | short | 90 | 36 | 63% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Beard 1963 | USA | short | 212 | N/A | 60% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| Becker 1967 | USA | short | 50 | 46 | N/A | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Bejerholm 2015 | Sweden | long | 120 | 38 | 56% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Blankertz 1996 | USA | short | 122 | 36 | 64% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Bond 1986 | USA | long | 131 | 25 | 69% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Bond 1995 | USA | short | 86 | 35 | 51% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Bond 2007 | USA | long | 200 | 39 | 64% | Psychotic disorder | no |

| Bond 2015b | USA | short | 90 | 44 | 79% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Burns 2007 | Europe (UK, Italy, Germany, Netherlands, Bulgaria, Switzerland) |

long | 312 | 38 | 60% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Burns 2015 | UK | long | 123 | 38 | 59% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Chandler 1996 | USA | long | 256 | N/A | 43% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| Craig 2014 | UK | short | 159 | 24 | 73% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Dincin 1982 | USA | short | 132 | 25 | 53% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| Drake 1996 | USA | long | 143 | 37 | 48% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| Drake 1999b | USA | long | 152 | 39 | 39% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| Drake 2013 | USA | long | 2238 | 44 | 47% | Affective disorder | N/A |

| Drebing 2005 | USA | short | 21 | 46 | 95% | Affective disorder + substance dependence | yes |

| Drebing 2007 | USA | short | 100 | 46 | 99% | Affective disorder + substance dependence | yes |

| Eack 2009 | USA | long | 58 | 26 | 69% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| Gervey 1994 | USA | short | 34 | 19 | 67% | N/A | no |

| Gold 2006 | USA | long | 143 | N/A | 38% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Hoffmann 2012 | Switzerland | long | 100 | 34 | 65% | Affective disorder | yes |

| Howard 2010 | UK | long | 219 | 38 | 67% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Killackey 2008 | Australia | short | 41 | 21 | 81% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Killackey 2014 | Australia | short | 146 | 20 | 67% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Latimer 2006 | Canada | short | 150 | 40 | 62% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Lecomte 2014 | Canada | short | 24 | 32 | 71% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| Lehman 2002 | USA | long | 219 | 42 | 57% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| McFarlane 1996 | USA | long | 68 | 30 | 65% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| McFarlane 2000 | USA | long | 69 | 33 | 70% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| McGurk 2007 | USA | long | 48 | 38 | 55% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| McGurk 2009 | USA | long | 34 | 44 | 59% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Michon 2014 | Netherlands | long | 151 | 35 | 74% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Mueser 2004 | USA | long | 135 | 41 | 61% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Nuechterlein 2012 | USA | long | 69 | 25 | 67% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| O'Brien 2003 | UK | short | 1037 | N/A | 55% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Oshima 2014 | Japan | short | 37 | 41 | 49% | N/A | yes |

| Penk 2010 | USA | short | 89 | 45 | 100% | Affective disorder +substance abuse/dependence | yes |

| Schonebaum 2006 | USA | long | 177 | 38 | 55% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Tsang 2001 | China | short | 97 | 36 | 62% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Tsang 2010 | China | long | 189 | 35 | 49% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Twamley 2012a | USA | short | 58 | 51 | 64% | Psychotic disorder | yes |

| Viering 2015 | Switzerland | long | 183 | 43 | 47% | Affective disorder | yes |

| Waghorn 2014 | Australia | short | 208 | 32 | 69% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| Walker 1969 | USA | short | 28 | N/A | 96% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| Wong 2008 | China | long | 92 | 34 | 60% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

| Xiang 2007 | China | long | 103 | 38.6 | 47% | Psychotic disorder | N/A |

aFollow‐up: short ≤ 1 year; long > 1 year.

bSecondary outcomes:

1 = maintaining employment 2 = obtaining non‐competitive employment 3 = days to first competitive employment 4 = mental health 5 = quality of life 6 = dropouts 7 = hospital admissions.

2. Comparisons and outcomes in included studies.

| Study |

Comparison intervention main group |

Comparison intervention subgroups | Secondary outcomesb | Included in meta‐analysis | Included in network met‐analysis |

| Au 2015 | SE+ vs SE+ | SE+ symp vs SE+ symp |

1, 4, 5, 6 | no | no |

| Beard 1963 | TE vs psych care | CT vs psych care | 7 | yes | no |

| Becker 1967 | TE vs psych care | SWS vs psych care | 2, 7, 6 | yes | no |

| Bejerholm 2015 | SE vs PVT | hf IPS vs job skills training | 1, 2, 3,5 6, | yes | yes |

| Blankertz 1996 | PVT vs psych care | Job skills training vs psych care | 2, 6 | yes | no |

| Bond 1986 | TE vs TE | Not classified CH accelerated vs gradual |

2, 6, 7 | no | no |

| Bond 1995 | SE+ vs SE | SE+job skills training vs lfIPS | 1, 2, 7 | yes | no |

| Bond 2007 | SE vs TE | hf IPS vs CH | 1,2,3,4,5,6 | yes | yes |

| Bond 2015b | SE vs PVT | hf IPS vs job skills training | 1, 2,, 6, 7 | yes | no |

| Burns 2007 | SE vs PVT | hf IPS vs job skills training | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 | yes | yes |

| Burns 2015 | SE vs SE | hf IPS vs lf IPS | 1, 3, 4,5, 6, 7, | no | yes (sub) |

| Chandler 1996 | SE+ vs psych care | SE+ACT vs ACT | 2, 5, 6, 7 | yes | no |

| Craig 2014 | SE+ vs SE | SE+motivational interviewing vs hf IPS | 1, 2, 6 | yes | no |

| Dincin 1982 | TE vs psych care | CH vs psych care care | , 6, 7 | yes | no |

| Drake 1996 | SE vs PVT | lf IPS vs job skills training | 4, 5, 6 | yes | yes |

| Drake 1999b | SE vs TE | hf IPS vs SWS | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | yes | yes |

| Drake 2013 | SE vs psych | hf IPS vs psych | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 | yes | yes |

| Drebing 2005 | SE+ vs SE+ | unclassified SE+TE+contingency management vs SE+TE |

1, 6 | no | no |

| Drebing 2007 | SE+ vs SE+ | unclassified SE+TE+contingency management vs SE+TE |

1 | no | no |

| Eack 2009 | PVT vs psych care | CT vs psych care | 4, 6 | yes | yes |

| Gervey 1994 | SE vs TE | lf IPS vs SWS | 1 | yes | no |

| Gold 2006 | SE vs TE | hf IPS vs SWS | 1,2,3,4,5,6 | yes | yes |

| Hoffmann 2012 | SE vs TE | hf IPS vs SWS | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | yes | yes |

| Howard 2010 | SE vs PVT | hf IPS vs job skills training | 4, , 5, 6, 7 | yes | yes |

| Killackey 2008 | SE vs psych | hf IPS vs psych | 1, 6 | yes | no |

| Killackey 2014 | SE vs psych | hf IPS vs psych | 6 | yes | no |

| Latimer 2006 | SE vs TE | hf IPS vs SWS | 1, 2, 3, 6 | yes | no |

| Lecomte 2014 | SE+ vs SE | SE+symp vs hfIPS | 1, 2 | yes | no |

| Lehman 2002 | SE vs PVT | hf IPS vs job skills training | 2, 6 | yes | yes |

| McFarlane 1996 | Psych care vs psych care | Not classified ACT+multifamily groups vs ACT+crisis family intervention |

2, 4 | no | no |

| McFarlane 2000 | SE+ vs TE | ACT+SE vs SWS | 1, 2 | yes | yes |

| McGurk 2007 | SE+ vs SE | SE+symp vs lf IPS | 1, 4, 7, 6 | yes | yes |

| McGurk 2009 | SE+ vs SE | SE+symp vs lf IPS | 1, 4 | yes | yes |

| Michon 2014 | SE vs PVT | hf IPS vs job skills training | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 | yes | yes |

| Mueser 2004 | SE vs TE | hf IPS vs CH | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 | yes | yes |

| Nuechterlein 2012 | SE+ vs PVT | SE+job vs SST | 6 | yes | yes |

| O'Brien 2003 | SE vs psych care | lf IPS vs psych care | 2, 6, 7 | yes | no |

| Oshima 2014 | SE vs PVT | hf IPS vs job skills training | 1, 2, 6 | yes | no |

| Penk 2010 | TE vs PVT | SWS vs job skills training | 1, 2, 3, 6 | yes | no |

| Schonebaum 2006 | SE+ vs SE+ | ACT+SE vs SE+TE | 1, 6 | yes | yes(sub) |

| Tsang 2001 | PVT vs psych care | SST vs psych care | none | yes | no |

| Tsang 2010 | SE+ vs SE vs PVT | SE+symp vs hf IPS vs job skills training | 1, 5, 6 | yes | yes |

| Twamley 2012a | SE vs PVT | hf IPS vs job skills training | 1, 2, 3, 6 | yes | no |

| Viering 2015 | SE vs PVT | lf IPS vs job skills training | 6 | yes | yes |

| Waghorn 2014 | SE vs SE | lf IPS vs hfIPS | 1, 6 | no | no |

| Walker 1969 | TE vs psych care | SWS vs psych care | 1, 2, 7 | yes | no |

| Wong 2008 | SE vs PVT | hf IPS vs job skills training | 1, 2, 3, 6 | yes | yes |

| Xiang 2007 | PVT vs psych care | SST vs psych care | 4, 6, 7 | yes | yes |

(sub) = included in subgroup network meta‐analysis only.

ACT: assertive community treatment CH: Clubhouse CT: cognitive training job: job related skills training hf IPS: high‐fidelity Individual Placement and Support lf IPS: low‐fidelity Individual Placement and Support Psych care: psychiatric care only PVT: prevocational training SE: supported employment SE+: augmented supported employment SST: social skills training SWS: sheltered workshops Symp: symptom‐related skills training TE: transitional employment

Design

All studies were longitudinal RCTs. Fourteen RCTs were multi centre trials (Au 2015; Bond 1995; Bond 2007; Bond 2015b; Burns 2007; Chandler 1996; Drake 1996; Drake 2013; Howard 2010; Michon 2014; Schonebaum 2006; Tsang 2001; Tsang 2010; Waghorn 2014) and two used a multi‐arm design (Mueser 2004; Tsang 2010).Three studies used a cluster‐randomised design (Craig 2014; O'Brien 2003; Tsang 2001). O'Brien 2003 reported an ICC of 0.00148, indicating a low design effect. The other two trials did not report an ICC. Therefore we adjusted the data to the possible design effect with an assumed ICC of 0.1. We used this equation: 1+(M‐1)ICC to calculate the design effect according to the average cluster size (M) and the (assumed) ICC. For dichotomous data we divided the number of participants and the number of events by the design effect. We only reduced the sample size for continuous data. This method is described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

Setting and time

The majority of included RCTs (N = 30) were performed in North America. Five studies had been conducted in China, four in the UK, three in Australia, two in Switzerland and one each in Japan, the Netherlands and Sweden. One study was a European collaboration between the UK, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Bulgaria and Switzerland. Four RCTs were performed at the same psychiatric rehabilitation centre (Threshold, Chicago, USA) (Bond 1986; Bond 2007; Bond 2015b; Dincin 1982). The follow‐up ranged from three months (Tsang 2001) up to five years (Hoffmann 2012). The majority of included RCTs (N = 37) were published the year 2000 or later (see Table 2).

Participants

The 48 RCTs included 8743 participants with an average of 182 participants per study. The smallest RCT consisted of 21 participants (Drebing 2005, a pilot study) and the largest included 2238 participants (Drake 2013). In 22 RCTs the majority of the participants were white. Of the other RCTs, 13 involved a majority of non‐white participants and 16 RCTs did not describe the ethnicity of the participants. Remarkably, in 10 of out of 30 US trials, the majority of participants were non‐white. The mean age of the participants was 36 years. In one RCT (Gervey 1994) the age of the participants was only 19 years and another RCT (Twamley 2012a) specifically focused on older adults (mean age 51 years). The majority (63%) of the participants were male. In four studies more than 90% of the participants were male (Drebing 2005; Drebing 2007; Penk 2010; Walker 1969). This could be explained by the fact that these participants were all veterans. Marital status was described in 26 trials and nearly all participants were single.

The great majority (N = 39) of the RCTs contained predominantly participants with a psychotic disorder (schizophrenia, schizoaffective or other psychotic disorders). In only four studies (Drake 2013; Drebing 2005; Drebing 2007; Penk 2010) was an affective disorder the main diagnosis of the included participants. In three out of these four trials the majority of participants were diagnosed with substance use disorder and comorbid affective disorder (dual diagnosis) (Drebing 2005; Drebing 2007; Penk 2010). Aside from these trials, in another three RCTs (Blankertz 1996; Killackey 2008; Lehman 2002) substance abuse was described by the majority of participants. Most RCTs did not mention substance abuse or excluded these participants. Four RCTs exclusively included young adults with first episode psychosis (Craig 2014; Killackey 2008; Killackey 2014; Nuechterlein 2012). Somatic comorbidity was outlined in 11 trials. In McGurk 2009 74% of the participants had one or more medical co‐morbidities, often hypertension or diabetes, while almost all participants (92%) in Killackey 2008 were free of medical illness. In the remaining nine studies medical illness/physical impairment that could prevent participation or return to work was an exclusion criteria (Becker 1967; Bejerholm 2015; Bond 2007; Bond 2015b; Craig 2014; Drake 1996; Latimer 2006; McFarlane 1996; Wong 2008).

Consistent with our eligibility criteria, almost all trials included only participants who were unemployed at baseline. We included four additional RCTs with a small percentage (between 8% and 27%) of participants who were partly employed at baseline, and were willing to obtain another job (Eack 2009; Killackey 2008; Killackey 2014; Viering 2015). In one study (Viering 2015) we could extract the data of only those participants who were fully unemployed.

Thirty‐three studies described the percentage of participants with a working history, in 31 of these studies the majority had worked in the past (see Table 2). Most participants in 13 studies had worked recently (in the past five years) (Bejerholm 2015; Burns 2007; Drebing 2005; Drebing 2007; Gold 2006; Howard 2010; Latimer 2006; Michon 2014; Mueser 2004; Penk 2010; Schonebaum 2006; Tsang 2001; Viering 2015). Interest in (competitive) employment was an eligibility criteria in 34 studies. The educational level of the participants can be classified as mainly secondary educated. In five RCTs (Becker 1967; Gervey 1994; Michon 2014; Tsang 2001; Viering 2015) the participants had received primary education, and in another five trials (Au 2015; Drake 1996; Hoffmann 2012; Killackey 2008; Latimer 2006) the educational level was tertiary. In 15 RCTs (Bond 1986; Bond 1995; Bond 2007; Bond 2015b; Chandler 1996; Drake 2013; Drebing 2007; Gold 2006; Hoffmann 2012; Killackey 2008; Lehman 2002; McFarlane 2000; Michon 2014; Viering 2015; Waghorn 2014), the majority of participants received a disability benefit; in two RCTs (Drake 2013; Viering 2015) receiving a disability benefit was a requirement for enrolment in the study. Most trials, though, did not report benefit or other financial support status. Interestingly, only one RCT primarily focused on participants with criminal justice involvement (Bond 2015b).

Interventions

The interventions of all studies could be classified in our predefined intervention main groups: supported employment, augmented supported employment, prevocational training, transitional employment and psychiatric care only. In five studies (Au 2015; Bond 1986; Bond 2015b; Drebing 2005; Drebing 2007) the intervention and control conditions were classified as the same main group and we could only classify the intervention further, as one of our predefined subgroups, in one of these studies (Burns 2015). Subgroup classification of the other four studies was not possible, because these interventions had too many components. All subgroup interventions were represented in the included studies except for social enterprise.

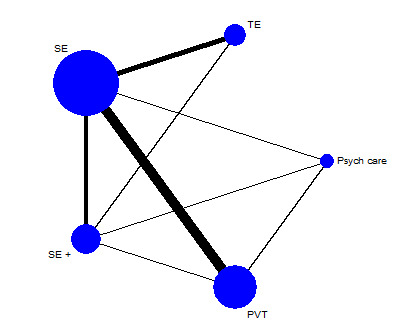

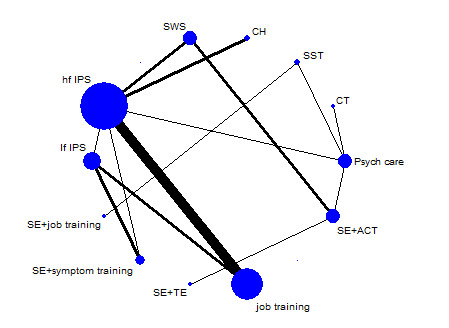

Figure 2 (main groups) and Figure 3 (subgroups) show the networks of evidence for the benefit (obtaining competitive employment) of the included interventions in the network meta‐analysis. Each line refers to the interventions that have been directly compared in studies. The thickness of the line is proportional to the number of participants included in the comparison and the width of each circle is proportional to the number of studies included in the comparison.

2.

Network plot of direct comparisons of intervention main groups (long‐term follow‐up). Psych care: psychiatric care only; PVT: prevocational training; SE: supported employment; SE+: augmented supported employment; TE: transitional employment

3.

Network plot of direct comparisons of intervention subgroups (long‐term follow‐up). CH: Clubhouse; CT: cognitive training; hf IPS: high‐fidelity Individual Placement and Support; job : job‐related skills training; lf IPS: low‐fidelity Individual Placement and Support; Psych care: psychiatric care only; SE + ACT: supported employment + assertive community treatment; SE + job: supported employment + job‐related skills training; SE + symp: supported employment + symptom‐related skills training; SE + TE: supported employment + transitional employment; SST: social skills training; SWS: sheltered workshops

Prevocational training

We classified prevocational training as the main component of the intervention or control condition in 17 RCTs. We found four trials that compared prevocational training to psychiatric care only (Blankertz 1996; Eack 2009; Tsang 2001; Xiang 2007). Blankertz 1996 used job‐related skills training, Eack 2009 used cognitive training, Tsang 2001 and Xiang 2007 used social skills training. The cognitive training in Eack 2009 consisted of three months of weekly, computer‐based neurocognitive training and social cognitive group training sessions. In Tsang 2001 the participants were engaged in 10, weekly group sessions. This was a three‐armed trial with two arms of social skills training with or without follow‐up contacts. Xiang 2007 applied a standardised social skills training programme, the Community Re‐entry Module, to facilitate the transition from hospital to community. This programme contained 16 group sessions.

Twelve RCTs compared SE to job‐related skills training (Bejerholm 2015; Bond 2015b; Burns 2007; Drake 1996; Howard 2010; Lehman 2002; Michon 2014; Tsang 2010; Twamley 2012a; Viering 2015; Wong 2008; Xiang 2007). In addition, Penk 2010 compared sheltered workshops to job‐related skills training and Nuechterlein 2012 compared SE plus job‐related skills training to social skills training. The interventions classified as job‐related skills training were very heterogeneous regarding the support that the participants received. This was a group of interventions/usual care using a stepwise approach, with components of job counselling/coaching and training sessions for job skills or other work‐related tasks such as job interviewing.

Transitional employment

In six RCTs transitional employment was the intervention of interest (Beard 1963; Becker 1967; Bond 1986; Dincin 1982; Penk 2010; Walker 1969) and in eight the control condition (Bond 2007; Drake 1999b; Gold 2006; Hoffmann 2012; Latimer 2006; McFarlane 2000; Mueser 2004; Oshima 2014), most frequently compared to supported employment. Nine RCTs described transitional employment as sheltered workshops (Beard 1963; Becker 1967; Dincin 1982Drake 1999b; Gold 2006; Hoffmann 2012; Latimer 2006; McFarlane 2000; Penk 2010) and five RCTs used the Clubhouse model (Beard 1963; Bond 1986; Bond 2007; Dincin 1982; Mueser 2004) We did not find any trials that evaluated social enterprises.

Supported employment

The most common intervention was supported employment, as we found 30 RCTs that included supported employment as intervention or control condition, see Table 2. The majority (24 RCTs) used high‐fidelity individual placement and support (IPS), In two studies, both the intervention and control condition were supported employment but differed in IPS fidelity (Burns 2015; Waghorn 2014). In the other RCTs, supported employment was the intervention condition, apart form six RCTs that compared augmented supported employment to supported employment only (Bond 1995; Craig 2014; Lecomte 2014; McGurk 2007; McGurk 2009; Tsang 2010). Most included RCTs reported IPS fidelity scores or described the classification (most often as 'good'). Author used the IPS fidelity scale most (such as in Bond 1997), but some trials (Bejerholm 2015; Bond 2015b; Craig 2014) applied a newer edition (Bond 2012b), and Michon 2014 used the QSEIS (Bond 2002). However, some older trials reported no fidelity scores, probably because they were carried out before the development of the fidelity scale (Bond 1995; Chandler 1996; Drake 1996; Gervey 1994). Some newer RCTs (including augmented supported employment) did not use a fidelity scale either (Au 2015; Burns 2015; Killackey 2014; McGurk 2009; Nuechterlein 2012; O'Brien 2003; Schonebaum 2006). In these cases we (YS, FS) discussed fidelity classification (high or low) based on description of the intervention and fidelity in the reports.

Augmented supported employment

We identified 13 RCTs that combined supported employment with another intervention. Au 2015 and Tsang 2010 combined supported employment with social skills training. Tsang 2010, a three‐armed trial, compared supported employment augmented with social skills training, Supported employment only, and prevocational job‐related skills training. Au 2015 compared su[ported employment combined to social skills training and cognitive training, with supported employment combined with social skills training only. Au 2015 and Tsang 2010 described 10 sessions of work‐related social skills training, conducted prior to job search. Nuechterlein 2012 tested the Workplace Fundamental Module, in which the participants receive group skills training for a year integrated with IPS compared to a skills training only. Three other RCTs also focused on the addition of cognitive training or cognitive behavioural interventions (Lecomte 2014; McGurk 2007; McGurk 2009). The cognitive training in Au 2015 consisted of three sessions a week for three months, with visual‐based, computer‐assisted cognitive exercises by two cognitive remediation software systems (Strongarm and Captain's Log). McGurk 2007 and McGurk 2009 also used computer‐based cognitive exercises (Cogpack) for two to three sessions a week for 12 to 16 weeks. The cognitive therapist worked together with the employment specialist and advised about cognitive impairments and supports needed to enhance work performance. McGurk 2009 also used group sessions. Lecomte 2014 implemented eight sessions during one month of group cognitive behavioural therapy. Bond 1995 compared a period of prevocational job‐related skills training followed by supported employment to immediate enrolment in supported employment(without training).

Four studies (Chandler 1996; Gold 2006; McFarlane 2000; Schonebaum 2006) combined supported employment to assertive community treatment (ACT). Schonebaum 2006 compared supported employment plus Clubhouse model to supported employment plus ACT. McFarlane 2000 and Gold 2006 coupled ACT and supported employment and compared this to transitional employment. Chandler 1996 compared supported employment plus ACT to ACT only. Two studies (Drebing 2005; Drebing 2007), including one separate pilot study, focused on contingency management. They used incentives for taking steps towards obtaining and maintaining competitive employment and for abstinence from substance abuse. The participants (veterans) were placed in transitional employment, but this programme also included supported employment components. One study (Craig 2014) added motivational interviewing for care co‐ordinators to supported employment. Six studies delivered high‐fidelity IPS (Craig 2014; Gold 2006; Lecomte 2014; Nuechterlein 2012; Schonebaum 2006; Tsang 2010).

Psychiatric care only

In 13 RCTs the control group did not consist of specific vocational interventions (Beard 1963; Becker 1967; Blankertz 1996; Chandler 1996; Dincin 1982; Drake 2013; Eack 2009; Killackey 2008; Killackey 2014; O'Brien 2003; Tsang 2001; Walker 1969; Xiang 2007). In most of these trials the control condition was care as usual. One study (McFarlane 1996) compared ACT plus family psycho‐education group to ACT plus crisis family intervention. We did not include this trial in the analyses because we could not classify both arms in different intervention groups.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

All RCTs reported data for our primary outcome (percentage or number of participants who obtained competitive employment). The definition used was not always equal. Some trials required a period of time being in competitive employment or a minimum number of hours worked a week, or both, before they counted it as a successful result (Au 2015; Bejerholm 2015; Bond 1986; Drebing 2007; Gervey 1994; Hoffmann 2012; Oshima 2014; Penk 2010; Tsang 2010; Twamley 2012a; Viering 2015; Wong 2008; Xiang 2007). This ranged from a minimum requirement of five days' Hoffmann 2012 to three months' (Xiang 2007) consecutive working and from five hours' (Oshima 2014) to 20 hours' (Tsang 2010; Drebing 2007) working a week. Moreover, Tsang 2010 also required two months of working.