Abstract

Background

Pancreatoduodenectomy is a surgical procedure used to treat diseases of the pancreatic head and, less often, the duodenum. The most common disease treated is cancer, but pancreatoduodenectomy is also used for people with traumatic lesions and chronic pancreatitis. Following pancreatoduodenectomy, the pancreatic stump must be connected with the small bowel where pancreatic juice can play its role in food digestion. Pancreatojejunostomy (PJ) and pancreatogastrostomy (PG) are surgical procedures commonly used to reconstruct the pancreatic stump after pancreatoduodenectomy. Both of these procedures have a non‐negligible rate of postoperative complications. Since it is unclear which procedure is better, there are currently no international guidelines on how to reconstruct the pancreatic stump after pancreatoduodenectomy, and the choice is based on the surgeon's personal preference.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pancreaticogastrostomy compared to pancreaticojejunostomy on postoperative pancreatic fistula in participants undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 9), Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 30 September 2016), Ovid Embase (1974 to 30 September 2016) and CINAHL (1982 to 30 September 2016). We also searched clinical trials registers (ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO ICTRP) and screened references of eligible articles and systematic reviews on this subject. There were no language or publication date restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the clinical outcomes of PJ compared to PG in people undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration. We performed descriptive analyses of the included RCTs for the primary (rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula and mortality) and secondary outcomes (length of hospital stay, rate of surgical re‐intervention, overall rate of surgical complications, rate of postoperative bleeding, rate of intra‐abdominal abscess, quality of life, cost analysis). We used a random‐effects model for all analyses. We calculated the risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes, and the mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes (using PG as the reference) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) as a measure of variability.

Main results

We included 10 RCTs that enrolled a total of 1629 participants. The characteristics of all studies matched the requirements to compare the two types of surgical reconstruction following pancreatoduodenectomy. All studies reported incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula (the main complication) and postoperative mortality.

Overall, the risk of bias in included studies was high; only one included study was assessed at low risk of bias.

There was little or no difference between PJ and PG in overall risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula (PJ 24.3%; PG 21.4%; RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.62; 7 studies; low‐quality evidence). Inclusion of studies that clearly distinguished clinically significant pancreatic fistula resulted in us being uncertain whether PJ improved the risk of pancreatic fistula when compared with PG (19.3% versus 12.8%; RR 1.51, 95% CI 0.92 to 2.47; very low‐quality evidence). PJ probably has little or no difference from PG in risk of postoperative mortality (3.9% versus 4.8%; RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.34; moderate‐quality evidence).

We found low‐quality evidence that PJ may differ little from PG in length of hospital stay (MD 1.04 days, 95% CI ‐1.18 to 3.27; 4 studies, N = 502) or risk of surgical re‐intervention (11.6% versus 10.3%; RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.61; 7 studies, N = 1263). We found moderate‐quality evidence suggesting little difference between PJ and PG in terms of risk of any surgical complication (46.5% versus 44.5%; RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.18; 9 studies, N = 1513). PJ may slightly improve the risk of postoperative bleeding (9.3% versus 13.8%; RR 0.69, 95% CI: 0.51 to 0.93; low‐quality evidence; 8 studies, N = 1386), but may slightly worsen the risk of developing intra‐abdominal abscess (14.7% versus 8.0%; RR 1.77, 95% CI 1.11 to 2.81; 7 studies, N = 1121; low quality evidence). Only one study reported quality of life (N = 320); PG may improve some quality of life parameters over PJ (low‐quality evidence). No studies reported cost analysis data.

Authors' conclusions

There is no reliable evidence to support the use of pancreatojejunostomy over pancreatogastrostomy. Future large international studies may shed new light on this field of investigation.

Plain language summary

Attachment to the jejunum versus stomach for the reconstruction of pancreatic stump following pancreaticoduodenectomy ('Whipple' operation)

Review question

Is pancreaticogastrostomy (PG, a surgery to join the pancreas to the stomach) better than pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ, a surgery to join the pancreas to the bowel) in terms of postoperative pancreatic fistula after a 'Whipple' operation (a major surgical operation involving the pancreas, duodenum, and other organs)?

Background

Pancreatoduodenectomy ('Whipple' operation) is a surgical procedure to treat diseases (most often cancer) of the pancreatic head, and sometimes, the duodenum. In a Whipple operation, the pancreas is detached from the gut then reconnected to enable pancreatic juice containing digestive enzymes to enter the digestive system. A common complication following Whipple surgery is pancreatic fistula, which occurs when the reconnection does not heal properly, leading to pancreatic juice leaking from the pancreas to abdominal tissues. This delays recovery from surgery and often requires further treatment to ensure complete healing. PJ and PG are surgical procedures often used to reconstruct the pancreatic stump after Whipple surgery and both procedures are burdened by a non‐negligible rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula. It is unclear which procedure is better.

Search date

We searched up to September 2016.

Study characteristics

We included 10 randomized controlled studies (1629 participants) that compared PJ and PG in people undergoing Whipple surgery. The studies' features were adequate to make feasible and the planned comparison between the two surgical techniques. The primary outcomes were pancreatic fistula and death. Secondary outcomes were duration of hospitalization, surgical re‐intervention, overall complications, bleeding, abdominal abscess, quality of life, and costs.

Key results

We could not demonstrate that one surgical procedure is better than the other. PJ may have little or no difference from PG in overall postoperative pancreatic fistula rate (PJ 24.3%; PG 21.4%), duration of hospitalization, or need for surgical re‐intervention (11.6% versus 10.3%). Only seven studies clearly distinguished clinically significant pancreatic fistula which required a change in the patient's management. We are uncertain whether PJ improves the risk of clinically significant pancreatic fistula when compared with PG (19.3% versus 12.8%). PJ probably has little or no difference from PG in rates of death (3.9% versus 4.8%) or complications (46.5% versus 44.5%). The risk of postoperative bleeding in participants undergoing PJ was slightly lower than those undergoing PG (9.3% versus 13.8%), but this benefit appeared to be balanced with a higher risk of developing an abdominal abscess in PJ participants (14.7% versus 8.0%). Only one study reported quality of life; PG may be better than PJ in some quality of life parameters. Cost data were not reported in any studies.

Quality of the evidence

Most studies had flaws in methodological quality, reporting or both. Overall, the quality of evidence was low.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Pancreaticojejunostomy compared with pancreatogastrostomy after pancreatoduodectomy.

| Pancreaticojejunostomy compared with pancreatogastrostomy after pancreatoduodectomy | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy (mainly for pancreatic cancer) Setting: hospital Intervention: pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) Comparison: pancreatogastrostomy (PG) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with PG | Risk with PJ | |||||

|

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C) Follow up: 30 days |

214 per 1000 | 254 per 1000 | RR 1.19 (0.88 to 1.62) | 1513 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b,c | |

|

Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C) Follow up: 30 days |

128 per 1000 | 193 per 1000 | RR 1.51 (0.92 to 2.47) | 1184 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c,d | |

|

Postoperative mortality Follow up: 90 days |

48 per 1000 | 41 per 1000 | RR 0.84 (0.53 to 1.34) | 1629 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Moderatec,d | |

|

Length of hospital stay Follow up: 30 days |

The mean length of hospital stay in the PG group was 15.2 days | The mean length of hospital stay in the PJ group was 1.04 days higher (1.18 lower to 3.27 higher) | MD 1.04 (‐1.18 to 3.27) | 502 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b,c | |

|

Surgical re‐intervention Follow up: 30 days |

103 per 1000 | 122 per 1000 | RR 1.18 (0.86 to 1.61) | 1263 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c,d | |

|

Surgical complications Follow up: 30 days |

445 per 1000 | 458 per 1000 | RR 1.03 (0.90 to 1.18) | 1513 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea,c | |

| Postoperative bleeding Follow up: 30 days | 138 per 1000 | 95 per 1000 | RR 0.69 (0.51 to 0.93) | 1386 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c,d | |

|

Intra‐abdominal abscess Follow up: 30 days |

80 per 1000 | 142 per 1000 | RR 1.77 (1.11 to 2.81) | 1121 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c,d | |

|

Quality of life Follow‐up: 0 to 12 months |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 320 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c,e | |

| Cost analysis | Not reported | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk was the control group proportion in the study. The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: Mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

a Downgraded one level for serious risk of bias.

b Downgraded one level for serious heterogeneity.

c Publication bias could not be assessed because of few studies.

d Downgraded one level for serious imprecision. (The CI of risk ratio overlapped 0.75 and 1.25 or total number of events < 300).

e Downgraded one level for serious imprecision (total population size < 400).

Background

Description of the condition

Pancreatoduodenectomy is a surgical procedure used to treat diseases of the pancreatic head, and less often of the duodenum, such as cancer (Chen 2015; Kamisawa 2016; Yamaguchi 2012), traumatic lesions, and chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatic carcinoma (which originates from the exocrine component of the pancreatic gland and mainly occurs in the head of the organ) is the most frequent indication for pancreatoduodenectomy (also known as pancreaticoduodenectomy). Pancreatic carcinoma is among the top 10 malignancies in terms of both incidence and mortality (Kamisawa 2016; Torre 2015). Pancreatoduodenectomy is the only potentially curative treatment (Gall 2015; Kamisawa 2016).

Independent of the indication to perform pancreatoduodenectomy, once the pancreatic head and the duodenum are resected, the surgeon needs to reconnect both the biliary tract and the pancreatic stump (that is, the remaining parts of the organ: the pancreatic body and tail) to enable the bile and pancreatic juice to reach the intestinal tract, ultimately enabling the person to digest food taken orally (Cheng 2016a; Cheng 2016b; Hüttner 2016).

While the technique for the reconstruction of the biliary tract is quite standardized, entailing the anastomosis of the common bile duct, or choledochus, to the jejunum, the reconstruction of the pancreatic stump is a subject of debate (Conzo 2015; Gómez 2014; Menahem 2015; Sakorafas 2001; Zhang 2015). Two procedures can be used: pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ, also known as pancreaticojejunostomy), which is anastomosis of the pancreatic stump and the jejunum, and pancreatogastrostomy (PG, also known as pancreaticogastrostomy), which is anastomosis of the pancreatic stump and stomach.

Pancreatoduodenectomy is a major surgery, which is technically demanding, time consuming, and prone to postoperative complications that can lead to deaths in a non‐negligible percentage of cases: in fact, the procedure is burdened by a 20% to 40% postoperative complication rate and a 1% to 6% postoperative mortality rate (Penumadu 2015; Shukla 2011; Testini 2016). Adverse events are mainly linked to leakage from one (or more) of the three anastomoses required for this surgical procedure: pancreatico‐digestive (between the pancreas and the alimentary tract), bilio‐digestive (between the biliary ducts (originating from the liver) and the alimentary tract), and gastro‐digestive anastomosis (between the stomach and the rest of the alimentary tract). The most common is pancreatico‐digestive anastomosis leakage (De Carlis 2014; Lai 2009; Testini 2016). Other potential postoperative complications include bleeding and intra‐abdominal abscess (Conzo 2015; Menahem 2015; Testini 2016; Zhang 2015). Assessing whether a surgical technique minimizes such complications in order to decrease morbidity and mortality associated with this type of operation can therefore be considered to be of paramount importance.

See Appendix 1 for a glossary of terms.

Description of the intervention

PJ and PG are surgical procedures used to reconstruct the pancreatic stump after pancreatoduodenectomy (Conzo 2015; Gómez 2014; Sakorafas 2001). PJ is currently performed more frequently worldwide (approximate ratio of 3:1) (Fernández‐Cruz 2011; Kamisawa 2016; Tewari 2010). For both PJ and PG, a dehiscence (leakage) of the anastomosis between the pancreatic stump and the stomach or the jejunum can occur, which represents the most frequent postoperative complication in pancreatic surgery (Menahem 2015; Penumadu 2015; Shukla 2011; Zhang 2015). Dehiscence can lead to the formation of a pancreatic fistula. Pancreatic juice (essential for digestion) can leak from the fistula into the peritoneal cavity or drained via one or more surgical drains placed during surgery with the aim of avoiding fistula formation. If a fistula forms, surgical re‐intervention to remove the pancreatic remnant may be required as a life‐saving measure. However, this depends on the output of the fistula, since low outputs can be often managed conservatively (the fistula heals with medical support but without surgical re‐intervention), whereas high outputs often require redo surgery. In the worst‐case scenario, the dehiscence of the pancreatico‐digestive anastomosis can lead to death (generally in the postoperative period, which is often defined as within 90 days of surgery).

Many factors have been considered to influence the development of postoperative pancreatic fistula, such as age, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, pancreatic texture, and pancreatic duct size (e.g. < 3 mm) (Ramacciato 2011; Riall 2008).

Other potential postoperative complications include hemorrhage and formation of intra‐abdominal abscess, both or which contribute to the morbidity and mortality following pancreatoduodenectomy (Conzo 2015; Menahem 2015; Testini 2016; Zhang 2015).

How the intervention might work

Surgeons most often perform PJ to connect the pancreatic stump to the jejunum. Although many techniques have been introduced to reduce the postoperative pancreatic fistula rate (such as duct‐to‐mucosa anastomosis and telescopic invagination of pancreatic stump into the jejunal loop), the issue remains and no one technique is considered to be superior (Hua 2015). Pancreatic juice enters the jejunum and pancreatic enzymes become activated by intestinal hormones (such as enterokinase), which can lead to tissue damage at the pancreatojejunal anastomosis. Obstruction or edema of the jejunal loop can also increase tension at the anastomotic level, thus increasing the likelihood of postoperative pancreatic fistula.

PG has been advocated for the prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula following pancreatoduodenectomy (McKay 2006). The primary reasons for performing PG rather than PJ are: (ⅰ) prevention of pancreatic enzyme activation by the acidic gastric environment and lack of enterokinase production by the stomach; (ⅱ) promotion of anastomosis healing by the better blood supply and greater thickness of the stomach wall (as compared to the jejunal wall); (ⅲ) invagination of the pancreatic stump into the stomach is technically easier compared to the same procedure using the jejunum; and (ⅳ) reduction of tension on the anastomosis by the routine use of nasogastric tube decompression. Due to these advantages, PG has the potential to prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula.

Why it is important to do this review

There are currently no international guidelines on how to reconstruct the pancreatic stump after pancreatoduodenectomy because it is unclear if one procedure (PJ or PG) is better than the other. It is therefore important to provide people, physicians (especially surgeons), and healthcare policy makers with a systematic review of the available evidence along with a formal comparison (meta‐analysis) of the outcomes obtained with each procedure.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pancreaticogastrostomy compared to pancreaticojejunostomy on postoperative pancreatic fistula in participants undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reported as full text only. Cross‐over and cluster‐randomized studies were not eligible.

Types of participants

We included adults undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy for any pancreatic/duodenal disease requiring this surgical treatment (although we expect that most if not all participants were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer).

Types of interventions

Pancreaticojejunostomy reconstruction.

Pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (time point closest to 30 days; defined by the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (Bassi 2005a; Bassi 2017).

Overall rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C).

Rate of clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C).

2. Postoperative mortality (time point closest to 90 days).

Secondary outcomes

Length of hospital stay (days).

Rate of surgical re‐intervention (time point closest to 30 days; to repair a pancreatic fistula, drain an intra‐abdominal abscess, or stop bleeding).

Overall rate of surgical complications (time point closest to 30 days; classified by the Clavien‐Dindo classification of surgical complications (Clavien 2009; Dindo 2004).

Rate of postoperative bleeding (time point closest to 30 days).

Rate of intra‐abdominal abscess (time point closest to 30 days).

Quality of life.

Cost analysis.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted a literature search to identify all published and unpublished randomized controlled trials by using a combination of headings and text words relating to pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) and pancreatogastrostomy (PG). The literature search identified potential studies in all languages. We had planned to translate non‐English language papers and fully assess them for potential inclusion in the review as necessary, but we did not find non‐English language literature eligible for this review.

We searched the following electronic databases to identify potential studies:

the Cochrane Library databases (Cochrane Reviews and other reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and health technology assessments) (February 2017) (Appendix 2);

MEDLINE (Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE 1946 to February 2017) (Appendix 3);

Embase (OvidSP 1974 to February 2017) (Appendix 4);

CINAHL (1982 to February 2017) (Appendix 5).

In June 2017 we also searched PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) before completing the review to capture non‐MEDLINE records (February 2017).

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We contacted authors of identified studies to locate other published and unpublished studies, but none of them replied to our emails.

We searched for errata or retractions from eligible studies on www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed and reported the date this was done within the review.

Grey literature database

OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu).

Clinical trials registers

We searched:

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp/en/); and

ClinicalTrials.gov.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SM, ML) independently screened titles and abstracts of all potential studies we identified as a result of the search for inclusion and coded them as 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. We retrieved the full text of studies, and two review authors (SM, ML) independently screened the full text and identified studies for inclusion, as well as identified and recorded reasons for exclusion of the ineligible studies. We resolved any disagreements through discussion or, if required, by consulting two other review authors (PP, YC). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Data extraction and management

We used a standardized data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data which was piloted on at least one study in the review. Two review authors (SM, XW) extracted the following study characteristics from included studies:

Methods: study design, number of study centers and location, withdrawals, date of study.

Participants: number, mean age, gender, diagnostic criteria (for pancreatic fistula), inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria.

Interventions: intervention, comparison.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected.

Two review authors (SM, XW) independently extracted outcome data from included studies. We noted in the Characteristics of included studies table if outcome data was reported in an unusable way. We resolved disagreements by consensus or by involving two other authors (PP, JG). Two review authors (MB, JG) entered data from the data collection forms into the Review Manager file (Review Manager 2014). We double‐checked that the data were entered correctly by comparing the study reports with how the data were presented in the systematic review. A second review author spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the study report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SM, BT) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving two other review authors (PP, NC). The 'Risk of bias' assessment considers the following domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias.

We did not consider blinding of participants (which cannot influence outcomes in the present setting) and personnel (which is not applicable in the present setting) to be relevant. We graded each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarized the 'Risk of bias' judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. We considered blinding separately for different key outcomes where necessary, for example unblinded outcome assessment risk of bias for all‐cause mortality may be very different than for a participant‐reported pain scale.

When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that contribute to that outcome.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to a published protocol (Cheng 2016) and reported any deviations in Differences between protocol and review.

Measures of treatment effect

We analyzed dichotomous data (e.g. mortality, pancreatic fistula and reoperation rates) as risk ratios (RR) and continuous data (e.g. length of hospital stay) as mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) as a measure of uncertainty. We ensured that higher scores for continuous outcomes had the same meaning for the particular outcome, explained the direction to the reader, and reported where the directions were reversed if this was necessary.

We undertook meta‐analyses only where this was meaningful, that is, if the treatments, participants and the underlying clinical question were sufficiently similar for pooling to make sense. In light of the unavoidable clinical heterogeneity of surgical outcomes (which depends on the ability and experience of individual surgeons), we used the inverse variance random‐effects model (DerSimonian 2015). We performed a meta‐analysis using Review Manager software (Review Manager 2014).

Unit of analysis issues

We did not find unit of analysis issues.

Dealing with missing data

No missing data were found In the case of withdrawals or dropouts, we used available data and reported the number of withdrawals or dropouts.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among studies in each analysis (Higgins 2003); we regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the I² was > 50%. In case of substantial heterogeneity, we explored it by prespecified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Publication bias was evaluated by assessing funnel plot asymmetry. Other causes of reporting bias (such as duplication bias) were excluded (no duplicates were found).

Data synthesis

'Summary of findings' table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table for all considered outcomes. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence as it relates to the studies which contribute data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes (GRADEpro GDT 2015). To this aim, we used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We justified all decisions to downgrade the quality of studies using footnotes and made comments to aid a reader's understanding of the review where necessary. We planned to consider whether there was any additional outcome information that could not be incorporated into the meta‐analyses and note this in the comments and state if it supports or contradicts the information from the meta‐analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We carried out the following subgroup analyses:

Studies performed in Western versus Eastern countries.

Pancreatoduodenectomy performed through a laparotomy versus laparoscopy.

Different procedures (e.g. single or double‐layer PG, end‐to‐end or end‐to‐side PJ).

Different risks of postoperative pancreatic fistula.

Different etiologies (e.g. pancreatic cancer, periampullary cancer, and others).

We used the following outcomes in subgroup analysis:

Postoperative pancreatic fistula.

Postoperative mortality.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis defined a priori to assess the robustness of our conclusions. This involved:

changing between fixed‐effect and a random‐effects models;

changing between worst‐ and best‐case scenario analysis for missing data;

excluding studies in which the mean, standard deviation, or both, were imputed;

excluding studies that did not use International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) criteria (Bassi 2005a; Bassi 2017);

excluding studies assessed at high risk of bias; and

excluding studies that did not apply classical reconstruction approach.

Reaching conclusions

We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative or narrative synthesis of included studies for this review. We avoided making recommendations for practice, and implications for research provide the reader with a clear sense of where the focus of any future research in the area should be and what the remaining uncertainties are.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

We identified a total of 1316 records through electronic searches of The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), and CINAHL. We did not identify any records from scanning reference lists. We excluded 482 duplicate records and 821 clearly irrelevant records from assessment of titles and abstracts. The remaining 13 records were retrieved for further assessment. We included 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Characteristics of included studies) and excluded three prospective, non‐randomized trials (Characteristics of excluded studies). See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 10 studies (Characteristics of included studies) that included a total of 1629 participants (mean = 163 participants per study). Studies were conducted in Belgium (Topal 2013), Canada (Grendar 2015), Egypt (El Nakeeb 2014), France (Duffas 2005), Germany (Keck 2016; Wellner 2012), Italy (Bassi 2005 ), Spain (Fernández‐Cruz 2008; Figueras 2013) and USA (Yeo 1995). The average age of participants ranged from 57.2 years to 68.0 years. The mean proportion of female participants ranged from 34.1% and 51.7%.

All studies randomly compared pancreatogastrostomy (PG) with pancreatojejunostomy (PJ) in participants undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy. While all studies reported on the incidence of pancreatic fistula (the most common complication of this type of surgery) and postoperative mortality, four reported participants' length of stay (N = 502), seven reported rate of surgical re‐intervention (N = 1263), nine reported overall rate of surgical complications (N = 1513), eight reported rate of postoperative bleeding (N = 1386), seven reported rate of intra‐abdominal abscess (N =1121), and one reported quality of life (N = 320). None reported cost analysis data.

In two studies (El Nakeeb 2014; Fernández‐Cruz 2008) the reconstruction of the pancreatic stump with the stomach was performed differently from other studies: El Nakeeb 2014 used an isolated Y‐shaped jejunal loop (Roux technique) and Fernández‐Cruz 2008 used a gastric partition technique, as compared to the classic Whipple approach. Therefore, we excluded these two studies from sensitivity analyses to explore their influence on the findings.

The included studies reported that they were conducted without direct funding.

Excluded studies

We excluded three studies (Arnaud 1999; Heeger 2013; Takano 2000) because they were prospective but non‐randomized comparisons of PJ and PG (Characteristics of excluded studies).

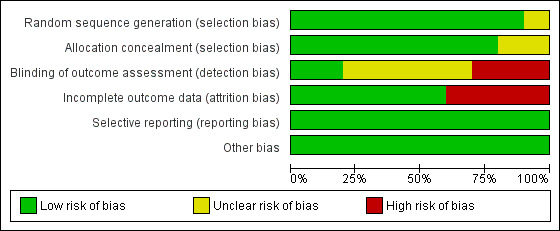

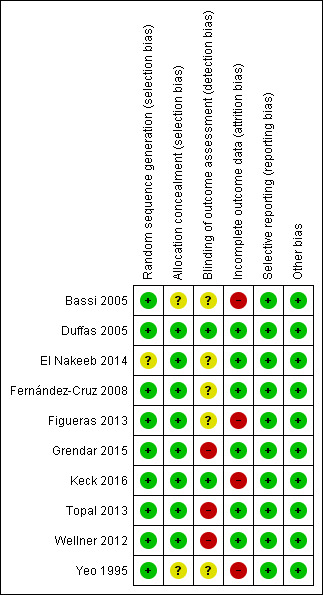

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias of the included studies is shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Only one study was considered to be at low risk of bias for all domains (Duffas 2005); the remaining nine RCTs were assessed at high risk of bias for one or two domains (Bassi 2005; El Nakeeb 2014; Fernández‐Cruz 2008; Figueras 2013; Grendar 2015; Keck 2016; Topal 2013; Wellner 2012; Yeo 1995). Details regarding the judgments on the risk of each type of bias are reported in the risk of bias tables (see Characteristics of included studies).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation was assessed at low risk of bias in nine studies where participants were randomised using computer‐generated numbers or a random numbers table (Bassi 2005; Duffas 2005; Fernández‐Cruz 2008; Figueras 2013; Grendar 2015; Keck 2016; Topal 2013; Wellner 2012; Yeo 1995) and unclear risk of bias in one study (El Nakeeb 2014). Allocation concealment was at low risk of bias in eight studies that used sealed opaque envelopes or central allocation methods to conceal the allocations (Duffas 2005; El Nakeeb 2014; Fernández‐Cruz 2008; Figueras 2013; Grendar 2015; Keck 2016; Topal 2013; Wellner 2012) and unclear risk of bias in two studies (Bassi 2005; Yeo 1995).

Blinding

Blinding of outcome assessment was assessed at low risk of bias in two studies (Duffas 2005; Keck 2016), unclear risk of bias in five studies (Bassi 2005; El Nakeeb 2014; Fernández‐Cruz 2008; Figueras 2013; Yeo 1995) and high risk of bias in two studies (Grendar 2015; Topal 2013; Wellner 2012). As explained in the Methods section, we did not consider blinding of participants (which could not influence outcomes) and personnel (which was not applicable).

Incomplete outcome data

There were no post‐randomization dropouts from seven studies (Duffas 2005; El Nakeeb 2014; Fernández‐Cruz 2008; Figueras 2013; Grendar 2015; Topal 2013; Wellner 2012) which were considered to be free from risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data. There were 133 dropouts (17.8%) from three studies (Bassi 2005; Keck 2016; Yeo 1995), but data were not analyzed on an intention‐to‐treat basis. These three studies were considered to be at high risk of attrition bias.

There were some losses of participants to follow‐up in two studies (Figueras 2013; Keck 2016). These two studies were considered to be high risk of bias due to loss of subjects to follow‐up.

Selective reporting

Study protocols were available for five studies (El Nakeeb 2014; Figueras 2013; Grendar 2015; Keck 2016; Topal 2013); all pre‐specified outcomes were reported, and these studies were considered to be free of selective reporting bias. The study protocols were not available for the other five studies. These five studies reported the outcomes of interest for this review (Bassi 2005; Duffas 2005; Fernández‐Cruz 2008; Wellner 2012; Yeo 1995). The review authors considered the five studies to be free of selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

No other sources of bias were found.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Postoperative pancreatic fistula

Overall rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C)

The overall postoperative pancreatic fistula rate was 24.3% (181/746) in the PJ group and 21.4% (164/767) in the PG group. The estimated RR for postoperative pancreatic fistula was 1.19 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.62; 9 studies, 1513 participants; Analysis 1.1). We downgraded the quality of evidence to low due to high risk of bias, concerns of publication bias, and inconsistency in the direction and magnitude of effects across the studies (I² = 52%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy, Outcome 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C).

Rate of clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C)

Only seven studies distinguished between any postoperative pancreatic fistula and clinically significant pancreatic fistula (El Nakeeb 2014; Fernández‐Cruz 2008; Figueras 2013; Grendar 2015; Keck 2016; Topal 2013; Wellner 2012). The clinically significant pancreatic fistula rate was 19.3% (112/581) in the PJ group and 12.8% (77/603) in the PG group. The estimated RR for clinically significant pancreatic fistula was 1.51 (95% CI 0.92 to 2.47; 7 studies, 1184 participants; Analysis 1.2). We downgraded the quality of evidence to very low due to high risk of bias, concerns of publication bias, serious imprecision, and inconsistency in the direction and magnitude of effects across the studies (I² = 60%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy, Outcome 2 Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C).

Postoperative mortality (time point closest to 90 days)

Postoperative mortality was 3.9% (31/803) in the PJ group and 4.8% (40/826) in the PG group. The estimated RR for postoperative mortality was 0.84 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.34; 10 studies, 1431 participants; Analysis 1.3). We downgraded the quality of evidence to moderate due to concerns of publication bias and serious imprecision.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy, Outcome 3 Postoperative mortality.

Secondary outcomes

Length of hospital stay (days)

The estimated MD for length of hospital stay was 1.04 days (95% CI ‐1.18 to 3.27; 4 studies, 502 participants; Analysis 1.4). We downgraded the quality of evidence to low due to high risk of bias, concerns of publication bias, and inconsistency in the direction and magnitude of effects across the studies (I² = 93%).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy, Outcome 4 Length of hospital stay.

Rate of surgical re‐intervention (time point closest to 30 days; to repair a pancreatic fistula, drain an intra‐abdominal abscess, or stop bleeding)

The surgical re‐intervention rate was 11.6% (72/623) in the PJ group and 10.3% (66/640) in the PG group. The estimated RR for surgical re‐intervention was 1.18 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.61; 7 studies, 1263 participants; Analysis 1.5). We downgraded the quality of evidence to low due to high risk of bias, concerns of publication bias, and serious imprecision.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy, Outcome 5 Surgical re‐intervention.

Overall rate of surgical complications (time point closest to 30 days; classified by the Clavien‐Dindo classification of surgical complications)

The overall rate of surgical complications was 46.5% (347/746) in the PJ group and 44.5% (341/767) in the PG group. The estimated RR for overall surgical complications was 1.03 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.18; 6 studies, 995 participants; Analysis 1.6). We downgraded the quality of evidence to moderate due to high risk of bias and concerns of publication bias.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy, Outcome 6 Surgical complications.

Rate of postoperative bleeding (time point closest to 30 days)

The overall rate of postoperative bleeding was 9.3% (63/681) in the PJ group and 13.8% (97/705) in the PG group. The estimated RR for postoperative bleeding was 0.69 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.93; 8 studies, 1386 participants; Analysis 1.7). We downgraded the quality of evidence to low due to high risk of bias, concerns of publication bias, and serious imprecision.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy, Outcome 7 Postoperative bleeding.

Rate of intra‐abdominal abscess (time point closest to 30 days)

The overall rate of abdominal abscess was 14.7% (82/559) in the PJ group and 8.0% (45/562) in the PG group. The estimated RR for abdominal abscess was 1.77 (95% CI 1.11 to 2.81; 7 studies, 1121 participants; Analysis 1.8). We downgraded the quality of evidence to low due to high risk of bias, concerns of publication bias, and serious imprecision.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy, Outcome 8 Intra‐abdominal abscess.

Quality of life

One study (320 participants) reported this outcome (Keck 2016). The quality of life scales used were the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer ‐ Quality of Life Questionnaire ‐ C30 (EORTC‐QLQ‐C30) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer ‐ Pancreatic Cancer Module 26 (EORTC‐PAN26). The range of both scales was 0 to 100 with higher values indicating better quality of life. Summary data for this outcome were not available, so we performed a narrative synthesis. The quality of life scores on both emotional and social functioning were higher in the PG group than in the PJ group at 12 months' follow‐up. We downgraded the quality of evidence to low due to high risk of bias, concerns about publication bias, and serious imprecision.

Cost analysis

None of the studies reported this outcome.

Subgroup analysis

We performed the following subgroup analyses:

Studies performed in Western versus Eastern countries (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3);

Different procedures (e.g. single or double‐layer PG, end‐to‐end, or end‐to‐side PJ) (Table 2; Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3; Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2; Analysis 4.3); and

Different risks of postoperative pancreatic fistula (Analysis 5.1; Analysis 5.2; Analysis 5.3).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by Western versus Eastern countries), Outcome 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by Western versus Eastern countries), Outcome 2 Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by Western versus Eastern countries), Outcome 3 Postoperative mortality.

1. Surgical techniques for the reconstruction of pancreatic stump following pancreaticoduodenectomy in included studies.

| Study ID | Surgical techniques | |

| Pancreaticojejunostomy | Pancreaticogastrostomy | |

| Bassi 2005 | End‐to‐side | Single‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy |

| Duffas 2005 | End‐to‐end or end‐to‐side | Single‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy |

| El Nakeeb 2014 | End‐to‐side | Double‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy |

| Fernández‐Cruz 2008 | Duct‐to‐mucosa | Double‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy |

| Figueras 2013 | Duct‐to‐mucosa | Double‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy |

| Grendar 2015 | Duct‐to‐mucosa | Double‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy |

| Keck 2016 | Various types of pancreaticojejunostomy | Various types of pancreaticogastrostomy |

| Topal 2013 | End‐to‐side | Single or double‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy |

| Wellner 2012 | Duct‐to‐mucosa | Double‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy |

| Yeo 1995 | End‐to‐end or end‐to‐side | Double‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by pancreaticojejunostomy techniques), Outcome 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by pancreaticojejunostomy techniques), Outcome 2 Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by pancreaticojejunostomy techniques), Outcome 3 Postoperative mortality.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by pancreaticogastrostomy techniques), Outcome 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by pancreaticogastrostomy techniques), Outcome 2 Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by pancreaticogastrostomy techniques), Outcome 3 Postoperative mortality.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula), Outcome 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula), Outcome 2 Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula), Outcome 3 Postoperative mortality.

The rate of clinically significant pancreatic fistula was higher in the PJ group than in the PG group in Western countries (Analysis 2.2). The rates of overall postoperative pancreatic fistula and clinically significant pancreatic fistula were higher in the PJ group than in the PG group in the subgroup analysis of end‐to‐end or end‐to‐side PJ (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2). There was no change in any of the primary outcomes except for clinically significant pancreatic fistula between the PJ group and the PG group in the subgroup analysis stratified by risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula (Analysis 5.2). The rate of clinically significant pancreatic fistula was higher in the PJ group than in the PG group for participants with high risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula (PJ 24.5%; PG 10.2%; RR 2.40, 95% CI 1.22 to 4.74; 1 study; 200 participants).

We were unable to perform planned subgroup analyses for type of surgery (laparotomic versus laparoscopic) and different etiologies (e.g. pancreatic cancer, periampullary cancer, and others), because outcome data for the different subgroups were not available from the studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed the following planned sensitivity analyses:

changing between fixed‐ and random‐effects models;

changing between worst‐ and best‐case scenario analysis for missing data;

excluding studies without applying the ISGPF definition (Bassi 2005a; Bassi 2017); and

excluding studies without applying classical reconstruction approach.

We observed no changes in results from changing between fixed‐ and random‐effects models except for clinically significant pancreatic fistula and length of hospital stay outcomes (Table 3). There were some post‐randomization dropouts in three studies (Bassi 2005; Keck 2016; Yeo 1995).

2. Sensitivity analyses.

| Changing between fixed‐effect and random‐effects models | ||||

| Outcomes | Risk ratio (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | ||

| Fixed‐effect | Random‐effects | Fixed‐effect | Random‐effects | |

| Postoperative pancreatic fistula | 1.12 (0.93 to 1.35) | 1.19 (0.88 to 1.62) | NA | NA |

| Clinically significant pancreatic fistula | 1.54 (1.18 to 2.01) | 1.51 (0.92 to 2.47) | NA | NA |

| Postoperative mortality | 0.84 (0.53 to 1.34) | 0.84 (0.53 to 1.34) | NA | NA |

| Length of hospital stay | NA | NA | 1.26 (0.84 to 1.69) | 1.04 (‐1.18 to 3.27) |

| Surgical re‐intervention | 1.18 (0.86 to 1.61) | 1.18 (0.86 to 1.61) | NA | NA |

| Surgical complications | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | 1.03 (0.90 to 1.18) | NA | NA |

| Postoperative bleeding | 0.69 (0.51 to 0.93) | 0.69 (0.51 to 0.93) | NA | NA |

| Intra‐abdominal abscess | 1.85 (1.29 to 2.65) | 1.77 (1.11 to 2.81) | NA | NA |

| Quality of life | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Cost analysis | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Changing between worst‐case scenario analysis and best‐case scenario analysis for missing data | ||||

| Outcomes | Risk ratio (fixed‐effect) (95% CI) | Risk ratio (random‐effects) (95% CI) | ||

| Worst‐case | Best‐case | Worst‐case | Best‐case | |

| Postoperative pancreatic fistula | 1.58 (1.34 to 1.87) | 0.80 (0.67 to 0.96) | 1.50 (1.20 to 1.88) | 1.03 (0.62 to 1.71) |

| Clinically significant pancreatic fistula | 2.38 (1.87 to 3.03) | 0.89 (0.71 to 1.13) | 1.89 (1.15 to 3.11) | 1.27 (0.56 to 2.87) |

| Postoperative mortality | 2.47 (1.71 to 3.59) | 0.42 (0.27 to 0.66) | 1.61 (0.77 to 3.38) | 0.53 (0.21 to 1.36) |

| Length of hospital stay | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Surgical re‐intervention | 2.06 (1.54 to 2.75) | 0.60 (0.46 to 0.79) | 1.36 (0.66 to 2.79) | 0.66 (0.40 to 1.10) |

| Surgical complications | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.27) | 0.90 (0.81 to 1.00) | 1.18 (0.90 to 1.55) | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.10) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 1.46 (1.14 to 1.87) | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.59) | 1.03 (0.59 to 1.82) | 0.52 (0.31 to 0.86) |

| Intra‐abdominal abscess | 1.94 (1.36 to 2.77) | 1.51 (1.09 to 2.08) | 1.86 (1.17 to 2.95) | 1.50 (0.98 to 2.31) |

| Quality of life | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Cost analysis | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Excluding studies without applying the ISGPF definition | ||||

| Outcomes | Risk ratio (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | ||

| Fixed‐effect | Random‐effects | Fixed‐effect | Random‐effects | |

| Postoperative pancreatic fistula | 1.11 (0.91 to 1.37) | 1.24 (0.80 to 1.90) | NA | NA |

| Clinically significant pancreatic fistula | 1.54 (1.18 to 2.01) | 1.51 (0.92 to 2.47) | NA | NA |

| Postoperative mortality | 0.81 (0.47 to 1.41) | 0.81 (0.47 to 1.41) | NA | NA |

| Length of hospital stay | NA | NA | 3.51 (2.59 to 4.44) | 0.51 (‐6.73 to 7.75) |

| Surgical re‐intervention | 1.21 (0.83 to 1.77) | 1.21 (0.83 to 1.77) | NA | NA |

| Surgical complications | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.14) | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.14) | NA | NA |

| Postoperative bleeding | 0.63 (0.45 to 0.89) | 0.63 (0.45 to 0.89) | NA | NA |

| Intra‐abdominal abscess | 1.86 (1.11 to 3.12) | 1.76 (0.82 to 3.81) | NA | NA |

| Quality of life | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Cost analysis | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Excluding studies without applying classical reconstruction approach | ||||

| Outcomes | Risk ratio (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | ||

| Fixed‐effect | Random‐effects | Fixed‐effect | Random‐effects | |

| Postoperative pancreatic fistula | 1.11 (0.91 to 1.35) | 1.16 (0.84 to 1.61) | NA | NA |

| Clinically significant pancreatic fistula | 1.54 (1.16 to 2.04) | 1.54 (0.93 to 2.54) | NA | NA |

| Postoperative mortality | 0.85 (0.52 to 1.39) | 0.85 (0.52 to 1.39) | NA | NA |

| Length of hospital stay | NA | NA | 0.59 (0.11 to 1.06) | 0.31 (‐1.13 to 1.75) |

| Surgical re‐intervention | 1.21 (0.88 to 1.67) | 1.21 (0.88 to 1.67) | NA | NA |

| Surgical complications | 1.00 (0.90 to 1.12) | 1.00 (0.90 to 1.12) | NA | NA |

| Postoperative bleeding | 0.70 (0.51 to 0.95) | 0.70 (0.51 to 0.95) | NA | NA |

| Intra‐abdominal abscess | 1.77 (1.23 to 2.56) | 1.65 (1.01 to 2.69) | NA | NA |

| Quality of life | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Cost analysis | NE | NE | NE | NE |

NE = Not estimable; NA = Not applicable

We observed no change in results from changing between worst‐ and best‐case scenario analysis for missing data except for the outcomes postoperative pancreatic fistula, clinically significant pancreatic fistula, postoperative bleeding, and intra‐abdominal abscess (Table 3).

We observed no change in the results by excluding studies without applying the ISGPF definition except for the outcome intra‐abdominal abscess (Table 3).

We observed no change in the results by excluding two studies (El Nakeeb 2014; Fernández‐Cruz 2008) without applying classical reconstruction approach (Table 3).

We did not perform sensitivity analysis by excluding studies in which the mean or standard deviation or both were imputed because no included studies met this criterion. We did not perform the sensitivity analysis by excluding studies with high risk of bias because nine of the 10 included studies were assessed at high risk of bias.

Discussion

Following pancreatoduodenectomy, there are two main types of surgical operations to connect the residual pancreatic stump to the digestive tract: pancreatojejunostomy (PJ) and pancreatogastrostomy (PG). We aimed to assess if one of these procedures is better in terms postoperative pancreatic fistula and mortality outcomes.

Summary of main results

We included evidence from 10 studies involving 1629 participants undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. PJ and PG reconstruction were similar in postoperative pancreatic fistula rate, mortality, length of hospital stay, surgical re‐intervention rate, and risk of any surgical complications. The risk of postoperative bleeding was lower in participants undergoing PJ, but this benefit was offset by a higher risk of developing an intra‐abdominal abscess associated with the PJ procedure. We found low‐quality evidence for improved quality of life associated with PG reconstruction. The impact of PG reconstruction on postoperative pancreatic fistula was less certain for high‐risk people.

The definition of postoperative pancreatic fistula varied among studies. The incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula ranged from 11.7% to 34.4% according to different definitions applied in each study (Wellner 2012;Bassi 2005; Duffas 2005; El Nakeeb 2014; Fernández‐Cruz 2008; Figueras 2013; Grendar 2015; Keck 2016; Topal 2013; Yeo 1995). An International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) proposed a consensus definition of postoperative pancreatic fistula to compare different surgical experiences in pancreatic surgery (Bassi 2005a; Bassi 2017). Postoperative pancreatic fistula has been graded as A, B, and C (Bassi 2005a); grade A is 'biochemical leak' which has no clinical impact and is no longer regarded as a true fistula; grade B requires a management change for the patient or persistent drainage for more than three weeks; grade C requires re‐operation or leads to organ failure and potentially to death (Bassi 2005a; Bassi 2017). Postoperative pancreatic fistula grades B and C have significant clinical impact and may be associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Bassi 2005a; Gurusamy 2013).

PG was first introduced as an alternative to PJ by Waugh 1946. Since then, several non‐randomized studies (Miyagawa 1992; Morris 1993; Ramesh 1990) have tested PG versus PJ during pancreaticoduodenectomy. All found a lower postoperative pancreatic fistula rate in the PG group over the PJ group. Yeo 1995 performed the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) on this topic in 1995. Yeo 1995 found a similar postoperative pancreatic fistula rate between PG and PJ groups. Yeo 1995 questioned the efficacy of PG reconstruction for the prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Since that time, several further RCTs have been published. Some authors suggested that PG was superior to PJ in terms of postoperative pancreatic fistula (Figueras 2013; Topal 2013), while others did not (Bassi 2005; Duffas 2005; El Nakeeb 2014; Fernández‐Cruz 2008; Grendar 2015; Keck 2016; Wellner 2012).

In this review, the incidence of overall postoperative pancreatic fistula (grades A, B or C) and clinically significant pancreatic fistula (grades B or C) were similar in the PJ and PG groups.

Many factors were considered to influence the development of postoperative pancreatic fistula (e.g. age, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, pancreatic texture, pancreatic duct size; Ramacciato 2011). Other confounding factors (e.g. different types of procedures, different etiologies) may also have an effect on the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula (Figueras 2013; Grendar 2015; Keck 2016; Topal 2013; Wellner 2012). Although some subgroup analyses showed differences in the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula between PJ and PG groups (Analysis 2.2; Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2; Analysis 5.2), the results should be interpreted with caution because few studies were included in each subgroup. Further studies are needed to enable robust analysis.

The current evidence does not support one procedure over the other. The choice between PJ and PG depends on personal experience or surgeon's preference.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The included studies appear to be sufficient to address the review objectives, except cost analysis. All studies directly addressed the issues of our review both in terms of participants and clinical outcomes.

Our findings support the conclusions made in a position statement published by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (Shrikhande 2016), where the choice of the type of surgical reconstruction is left to the surgeon's personal judgement.

Quality of the evidence

The major reason for downgrading the quality of evidence was risk of bias in the studies. Only one study was assessed at overall low risk of bias. A major source of bias was lack of blinding for outcome assessment Another major source of bias was incomplete outcome data.

A total of 133/749 (17.8%) participants were excluded from the analysis for various reasons in three studies (Bassi 2005; Keck 2016; Yeo 1995). None of these studies analyzed data on an intention‐to‐treat basis.

Another major issue affecting the quality of evidence was the precision of the outcomes. The confidence intervals for most outcomes were wide, which indicates that the estimates of effects obtained are imprecise.

There were too few included studies to assess publication bias.

Overall, the quality of the evidence was considered to be low (Table 1).

Potential biases in the review process

We believe we identified all relevant completed RCTs in this field of investigation. There were several potential biases of note in the review process. Firstly, the heterogeneity among the included studies (e.g. different etiologies and surgical techniques) may have impact on the primary outcomes and conclusions. The data from the studies were either sparse or not available for subgroup analyses. Secondly, we were unable to construct funnel plots to assess the publication bias due to the small number of included studies. Thirdly, data for length of hospital stay were skewed. The lack of normality might introduce bias in this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (Guerrini 2016 ‐ 8 RCTs; Lei 2014 ‐ 7 RCTs; Menahem 2015 ‐ 7 RCTs) reported statistically significant higher rates of pancreatic fistula in participants undergoing PJ. This suggests that PG might be a better surgical procedure to perform after pancreatoduodenectomy. However, a systematic review and meta‐analysis by Crippa 2016, which included 10 RCTs, found no significant differences among clinical outcomes following PJ or PG. Of note, no different RCTs (or outcomes) were included in the above mentioned reviews and meta‐analyses, Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that inclusion of all available RCTs (n = 10) leads to the same conclusion, that is, PJ is comparable to PG in terms of occurrence of postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Our findings suggest that there is no reliable evidence supporting the use of one surgical procedure over the other (PJ or PG) to reconstruct the pancreatic stump following pancreatoduodenectomy.

Implications for research.

New surgical techniques are needed to address the issues of postoperative mortality and morbidity rates associated with pancreatoduodenectomy.

In our opinion, future studies should:

emphasize the effect of PG for people with high risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy;

report the rate and grade of postoperative pancreatic fistulae according to the updated International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula criteria (Bassi 2005a; Bassi 2017);

report results stratified by etiology (cancer versus benign disease), surgical techniques, and risks of postoperative pancreatic fistula (high risk versus low risk) and report clinically important outcomes (e.g. quality of life, cost effectiveness);

analyze data on an intention‐to‐treat basis for post‐randomization dropouts.

Unfortunately, we found no ongoing trials in this field of investigation.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the help and support of the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Review Group.

The authors would also like to thank the following peer referees and Editors who provided comments to improve the review: Rafael Diaz‐Nieto, Alfretta Vanderheyden, Sarah Rhodes, and Grigorios Leontiadis.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

| Anastomosis | The surgical joining of two usually hollow body parts (or between a hollow organ such as the jejunum or the stomach and a secretory gland such as the pancreas) |

| Biliary tract | The ducts collecting the bile (produced by the liver) and carrying it to the alimentary tract (where the bile joins the pancreatic juice to digest food) |

| Carcinoma | A malignant tumor originating from organs with an epithelium (e.g. pancreas, colon, breast, lung) |

| Chronic | Long‐lasting (as opposed to 'acute') |

| Duct‐to‐mucosa | Surgical creation of a passage between the pancreatic duct and the mucosa of nearby gut |

| Duodenum | The first part of the small bowel (which in turn follows the stomach and precedes the large bowel in the alimentary tract) |

| Exocrine | Refers to the activity of a gland that produces a liquid ('juice') that is released into hollow organs (e.g. bowel). Its counterpart is the term endocrine, which refers to a gland that produces hormones (which are delivered into the bloodstream) |

| Gastric/gastro | Related to the stomach |

| Incidence | The number of new diagnoses |

| Jejunum | The part of the alimentary tract that follows the duodenum and precedes the ileum (which in turn precedes the large bowel or colon) |

| Lesion | Injury |

| Malignancy | Malignant tumor |

| Morbidity | The number of diseases (in this review, the number of postsurgical complications) |

| Mortality | The number of deaths |

| Pancreatic fistula | A complication whereby the pancreas is disconnected from the nearby gut, and then reconnected to allow pancreatic juice containing digestive enzymes to enter the digestive system |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | A major surgical operation involving the pancreas, duodenum, and other organs |

| Pancreaticogastrostomy | Surgical creation of a passage between the transected end of the pancreas and the stomach |

| Pancreaticojejunostomy | Surgical creation of a passage between the transected end of the pancreas and the jejunum |

| Pancreatitis | An inflammatory disease of the pancreas |

| Peritoneal | Relative to the peritoneum, a thin smooth membrane that lines the cavity of the abdomen |

| pH | The inverse logarithm of the concentration of hydrogen ions (H+). A measure of the acidity (or alkalinity) of a liquid |

| Resected | Surgically removed |

| Roux‐en‐Y limb | Denoting any Y‐shaped anastomosis in which the small intestine is included |

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Pancreaticojejunostomy] explode all trees #2 pancreatojejun* or pancreaticojejun* or (pancrea* near/3 jejunostom*):ti,ab,kw #3 #1 or #2 #4 pancreatogastro* or pancreaticogastro* or (pancrea* near/3 (gastro* or stomach)):ti,ab,kw #5 #3 and #4 #6 ((stomach or gastro*) near/5 jejun*) and pancrea* and (surger* or operation* or operated or operative or resect*):ti,ab,kw #7 (stomach or gastro*) and jejun* and pancrea* and anastomosis:ti,ab,kw #8 pancrea* near/3 stump:ti,ab,kw #9 #5 #6 or #7 or #8

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search strategy

1 exp Pancreaticojejunostomy/ 2 (pancreatojejun* or pancreaticojejun* or (pancrea* adj3 jejunostom*)).tw,kw. 3 1 or 2 4 (pancreatogastro* or pancreaticogastro* or (pancrea* adj3 (gastro* or stomach))).tw,kw. 5 3 and 4 6 (((stomach or gastro*) adj5 jejun*) and pancrea* and (surger* or operation* or operated or operative or resect*)).tw. 7 ((stomach or gastro*) and jejun* and pancrea* and anastomosis).tw. 8 (pancrea* adj3 stump).tw,kw. 9 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 10 randomized controlled trial.pt. 11 controlled clinical trial.pt. 12 random*.ab. 13 trial.ab. 14 groups.ab. 15 or/10‐14 16 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 17 9 not 16

Appendix 4. Embase search strategy

1 exp Pancreaticojejunostomy/ 2 (pancreatojejun* or pancreaticojejun* or (pancrea* adj3 jejunostom*)).tw,kw. 3 1 or 2 4 (pancreatogastro* or pancreaticogastro* or (pancrea* adj3 (gastro* or stomach))).tw,kw. 5 3 and 4 6 (((stomach or gastro*) adj5 jejun*) and pancrea* and (surger* or operation* or operated or operative or resect*)).tw. 7 ((stomach or gastro*) and jejun* and pancrea* and anastomosis).tw. 8 (pancrea* adj3 stump).tw,kw. 9 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 10 random*.mp. 11 clinical trial:.mp. 12 exp health care quality/ 13 double‐blind*.mp. 14 blind*.tw. 15 placebo:.mp. 16 or/10‐15 17 exp animal/ not human.sh. 18 16 not 17 19 9 and 18

Appendix 5. CINAHL search strategy

S9 S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8

S8 TX pancrea* and stump

S7 TX (stomach or gastro*) and jejun* and pancrea* and anastomosis

S6 TX ((stomach or gastro*) and jejun*) and pancrea* and (surger* or operation* or operated or operative or resect*)

S5 S3 AND S4

S4 TX pancreatogastro* or pancreaticogastro* or (pancrea* and (gastro* or stomach))

S3 S1 OR S2

S2 TX pancreatojejun* or pancreaticojejun* or (pancrea* and jejunostom*)

S1 (MH "Pancreaticojejunostomy")

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C) | 9 | 1513 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.88, 1.62] |

| 2 Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C) | 7 | 1184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.51 [0.92, 2.47] |

| 3 Postoperative mortality | 10 | 1629 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.53, 1.34] |

| 4 Length of hospital stay | 4 | 502 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [‐1.18, 3.27] |

| 5 Surgical re‐intervention | 7 | 1263 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.86, 1.61] |

| 6 Surgical complications | 9 | 1513 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.90, 1.18] |

| 7 Postoperative bleeding | 8 | 1386 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.51, 0.93] |

| 8 Intra‐abdominal abscess | 7 | 1121 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.77 [1.11, 2.81] |

Comparison 2. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by Western versus Eastern countries).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C) | 10 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Western countries | 9 | 1568 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.88, 1.63] |

| 1.2 Eastern countries | 1 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.9 [0.40, 2.00] |

| 2 Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C) | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Western countries | 6 | 1094 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.69 [1.02, 2.80] |

| 2.2 Eastern countries | 1 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.18, 1.82] |

| 3 Postoperative mortality | 10 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Western countries | 9 | 1539 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.52, 1.39] |

| 3.2 Eastern countries | 1 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.18, 3.16] |

Comparison 3. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by pancreaticojejunostomy techniques).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C) | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Duct‐to‐mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy | 3 | 329 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.63 [0.67, 3.94] |

| 1.2 End‐to‐end or end‐to‐side pancreaticojejunostomy | 5 | 864 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.31 [1.00, 1.72] |

| 2 Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C) | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Duct‐to‐mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy | 4 | 445 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.79 [0.79, 4.02] |

| 2.2 End‐to‐end or end‐to‐side pancreaticojejunostomy | 2 | 437 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.71 [1.55, 4.74] |

| 3 Postoperative mortality | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Duct‐to‐mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy | 4 | 445 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.28, 2.91] |

| 3.2 End‐to‐end or end‐to‐side pancreaticojejunostomy | 5 | 864 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.58, 2.04] |

Comparison 4. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by pancreaticogastrostomy techniques).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C) | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Single‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy | 2 | 300 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.75, 2.10] |

| 1.2 Double‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy | 5 | 564 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.73, 2.18] |

| 2 Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C) | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Single‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Double‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy | 5 | 535 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.45 [0.67, 3.10] |

| 3 Postoperative mortality | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Single‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy | 2 | 300 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.38, 2.18] |

| 3.2 Double‐layer pancreaticogastrostomy | 6 | 680 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.34, 2.07] |

Comparison 5. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy (stratified by risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade A, B or C) | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 High risk | 2 | 351 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.98, 2.01] |

| 1.2 Low risk | 1 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.81 [0.71, 4.59] |

| 1.3 Both high and low risk | 7 | 1033 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.77, 1.65] |

| 2 Clinically significant pancreatic fistula (Grade B or C) | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 High risk | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.40 [1.22, 4.74] |

| 2.2 Low risk | 1 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.63 [0.73, 9.46] |

| 2.3 Both high and low risk | 6 | 855 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.78, 2.33] |

| 3 Postoperative mortality | 10 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 High risk | 1 | 151 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.53 [0.10, 61.13] |

| 3.2 Low risk | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.3 Both high and low risk | 9 | 1478 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.51, 1.31] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bassi 2005.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial Single center |

|

| Participants | Country: Italy.

Number randomized: 163.

Post‐randomization dropouts: 12 (7.4%).

Mean age: 57.2 years. Female: 56 (37.1%). Pancreatic cancer: 99 (65.6%). Biliary cancer: 3 (2.0%). Ampullary cancer: 24 (15.9%). Duodenal cancer: 2 (1.3%). Other: 23 (15.2%). Classic pancreaticoduodenectomy: 15 (9.9%). Pylorus‐preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: 136 (90.1%). Inclusion criteria: Pancreas that was intra‐operatively considered to be soft and had a main duct diameter < 5 mm. |

|

| Interventions | Participants (N = 163) were randomly assigned to two groups. Group 1: Pancreaticojejunostomy (N = 84). Group 2: Pancreaticogastrostomy (N = 79). | |

| Outcomes | Postoperative pancreatic fistula: Yes. Postoperative mortality: Yes. Length of hospital stay: Yes. Rate of surgical re‐intervention: Yes. Overall rate of surgical complications: Yes. Rate of postoperative bleeding: Yes. Rate of intra‐abdominal abscess: Yes. Quality of life: No. Cost analysis: No. |

|

| Notes | Definition of pancreatic fistula: Any clinical significant output of fluid, rich in amylase, confirmed by fistulography. The calculated sample size, based on the reduction of overall complications rate from 25% to 5%, was 136 participants and the study met its estimated accrual. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "random numbers table". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No information provided. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: No information provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "Of the 163 patients that were randomized, 12 ductal cancer specimens were not considered in the present analysis". |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: All the primary outcomes were reported. The review authors consider this study to be free of selective reporting for the primary outcomes. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

Duffas 2005.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial Multicenter |

|

| Participants | Country: France.

Number randomized: 149. Post‐randomization dropout: 0 (0%). Mean age: 58.4 years. Female: 63 (42.3%). Pancreatic cancer: 59 (39.6%). Biliary cancer: 19 (12.8%). Ampullary cancer: 36 (24.1%). Duodenal cancer: 6 (4.0%). Other: 29 (19.5%). Classic pancreaticoduodenectomy: 113 (75.8%). Pylorus‐preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: 36 (24.2%). Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants (N = 149) were randomly assigned to two groups. Group 1: Pancreaticojejunostomy (N = 68). Group 2: Pancreaticogastrostomy (N = 81). | |

| Outcomes | Postoperative pancreatic fistula: Yes. Postoperative mortality: Yes. Length of hospital stay: Yes. Rate of surgical re‐intervention: Yes. Overall rate of surgical complications: Yes. Rate of postoperative bleeding: Yes. Rate of intra‐abdominal abscess: Yes. Quality of life: No. Cost analysis: No. |

|

| Notes | Definition of pancreatic fistula: (1) chemically as fluid obtained through drains or percutaneous aspiration, containing at least 4 times normal serum values of amylase for 3 days, irrespective of the amount of output and the date of appearance or (2) clinically and radiologically, as anastomotic leaks shown by fistulography. The calculated sample size, based on the reduction of intra‐abdominal complications rate from 40% to 20%, was 134 participants and the study met its estimated accrual. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "computerized random number tables". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Random allotment was through a telephone call to the coordinating center". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Postoperative complications were assessed by a physician who was unaware of the allotted treatment". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "There were no protocol violations, no crossovers, or withdrawals after randomization". Comment: There were no post‐randomization dropouts. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: All the primary outcomes were reported. The review authors consider this study to be free of selective reporting for the primary outcomes. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

El Nakeeb 2014.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial Single center |

|

| Participants | Country: Egypt. Number randomized: 90. Post‐randomization dropout: 0 (0%). Mean age: 55.5 years. Female: 40 (44.4%). Pancreatic tumor: 46 (51.1%). Biliary tumor: 2 (2.2%). Ampullary tumor: 36 (40.0%). Duodenal tumor: 6 (6.7%). Other: 0 (0%). Classic pancreaticoduodenectomy: 90 (100%). Pylorus‐preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: 0 (0%). Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|