Abstract

Background

A specific program designed to teach women to recognise active labour may be beneficial through potentially decreasing the incidence of early admission to hospital, increasing women's confidence, feelings of control and empowerment, and decreasing their anxiety.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of teaching pregnant women specific criteria for self‐diagnosis of active labour onset in term pregnancy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (October 2007). We updated this search on 30 November 2012 and added the results to the awaiting classification section of the review.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing a structured antenatal education intervention for the identification of symptoms for self‐diagnosis of active labour with usual care.

Data collection and analysis

Trial quality was assessed.

Main results

One study involving 245 women was included. Method of randomisation was unclear and 15% of the sample was lost to follow up in this trial. A specific antenatal education program was associated with a reduction in the mean number of visits to the labour suite before the onset of labour (weighted mean difference ‐0.29, 95% confidence interval ‐0.47 to ‐0.11). It is unclear whether this resulted in fewer women being sent home because they were not in labour.

Authors' conclusions

There is not enough evidence to evaluate the use of a specific set of criteria for self‐diagnosis of active labour.

Plain language summary

Antenatal education for self‐diagnosis of the onset of active labour at term

Not enough evidence to prove the benefit of a specific set of criteria to self‐diagnose active labour.

Sometimes it is difficult to tell when active labour has begun. A false diagnosis can mean multiple visits to the hospital, frustration and discomfort for the mother, decreased confidence in caregivers and additional financial burdens. Antenatal education of women has been developed to increase their confidence and decrease their anxiety. Providing a specific set of criteria to women may be an effective way of helping them recognise the onset of active labour. The review of trials found there was not enough evidence to show whether specific criteria are more beneficial than general guidelines in helping women determine their stage of labour.

Background

Timely diagnosis of active or progressive labour is problematic for caregivers and expectant women. The erroneous diagnosis of active labour may lead to a subsequent diagnosis of labour dystocia, the treatments for which are associated with risks for a mother and her infant (Thornton 1994). Mothers' confidence in their caregivers may be undermined and perceptions of the birth experience negatively affected when an incorrect labour diagnosis is amended (Simkin 1996). There may be additional financial burdens placed on facilities resulting from repeated assessment of women's labour status over multiple visits. These potential costs to women, their infants, and to health care may be avoided if admission to hospital for labour care occurs when active labour is established (Crowther 1989). Providing information for pregnant women and their families about labour diagnosis may be a means of enabling women to recognise active labour, and to cope with their contractions with confidence. Potential benefits include enhancing women's feelings of control and empowerment, while providing an opportunity for educators to correct inaccurate information. The number of erroneous labour diagnoses may possibly be reduced by enabling women to remain out of hospital until active labour is likely to have become established. A multitude of educational resources have been developed for pregnant women, the quality of which vary greatly. Commonly it is physicians, midwives or antenatal educators who provide information on the recognition of labour onset.

A specific program designed to teach women to recognise active labour may be beneficial through potentially decreasing the incidence of early admission to hospital, increasing women's confidence and feelings of control and empowerment, and decreasing their anxiety. The aim of this review is to determine the effects of teaching pregnant women a specific set of criteria for diagnosing the onset of active labour. Related reviews focus on the effectiveness of the application of strict criteria for labour diagnosis by caregivers (Lauzon 2001), and on the effectiveness of individual or group antenatal education for childbirth/parenthood (Gagnon 2007).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of teaching pregnant women specific criteria for self‐diagnosis of active labour onset in term pregnancy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials which compared a structured antenatal education intervention for the identification of symptoms for self‐diagnosis of active labour, with standard care in whatever way standard care was defined in the setting; violations of allocated management not sufficient to materially affect outcomes; missing data insufficient to materially affect the comparison.

Types of participants

All pregnant women.

Types of interventions

Any antenatal education programs specifically aimed at enhancing women's abilities to identify signs or symptoms leading to self‐diagnosis of active labour.

Types of outcome measures

The main outcomes of interest were:

caesarean section rate;

labour augmentation rates;

admissions to labour wards or visits to labour assessment units;

use of oxytocics, analgesics, and other intrapartum interventions;

intrapartum complications;

mothers' evaluations of their birth experiences;

rates of hospital discharge diagnoses of 'not in labour' or 'false labour';

rates of out‐of‐hospital emergencies (e.g. unplanned out‐of‐hospital births);

admission rates to special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (October 2007). We updated this search on 30 November 2012 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

The review authors independently selected and assessed the single trial resulting from the search. Names of authors, related institutions, journals of publication, and study results were known by the review authors when inclusion criteria were applied. Trials under consideration were evaluated for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion, regardless of results and conclusions, using standard Cochrane criteria. No identified trials were excluded from this review. Included trial data were processed as described in Clarke 2000.

Results

Description of studies

See table of 'Characteristics of included studies'.

The trial compared a structured antenatal education intervention for the identification of symptoms for self‐diagnosis of active labour, with no specific education, in an urban community hospital in the United States. Study participants were predominantly low‐income single African‐American women.

Risk of bias in included studies

In the single trial included in this review, the method of randomisation is unclear and 15% of the sample was lost to follow up.

Effects of interventions

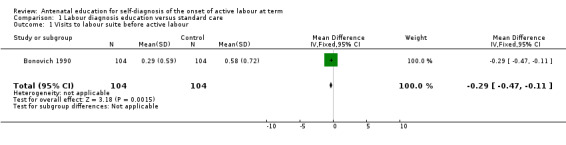

The study by Bonovich (Bonovich 1990) demonstrated that a specific antenatal education program was effective in reducing the mean number of visits to the labour suite before the onset of active labour (experimental group mean 0.29 (standard deviation (SD) 0.59), control group mean 0.58 (SD 0.72); weighted mean difference ‐0.29, 95% confidence interval ‐0.47 to ‐0.11). It is unclear, however, whether this intervention resulted in fewer women being sent home because they were not in labour.

Discussion

The method of randomisation is unclear in the single trial included in this review, and so results must be considered with some caution. Attempts to contact the principal investigator for the purposes of clarification thus far have been unsuccessful.

This type of outcome measurement reporting is of limited clinical value. There is no conclusive evidence of benefit for teaching women a specific antenatal education program for self‐diagnosis of active labour at present. Additionally, there is limited generalisability of results as the women participating were primarily single, low‐income, urban African‐Americans, in one hospital‐based clinic in the US.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

No implications for practice are warranted in light of the small amount of available evidence.

Implications for research.

Most women receive some instruction or advice regarding the signs and symptoms of labour. Whether women would benefit from learning a specific set of criteria for self‐diagnosis of active labour remains unclear. Understanding potential effects on outcomes such as patient satisfaction and empowerment may be enhanced through qualitative methods. Until these are better understood, it is questionable whether the potential risks and benefits of a structured educational program are of sufficient importance to warrant a large clinical trial.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 September 2017 | Amended | Added Published notes to explain that this review will no longer be updated by the review team. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1998 Review first published: Issue 4, 1998

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 December 2012 | Amended | Search updated. Two new reports added to Studies awaiting classification. |

| 12 November 2008 | Amended | Added published note about the next update of this review ‐ seePublished notes. |

| 11 February 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 23 October 2007 | New search has been performed | Search updated. No new trials identified. |

| 31 January 2004 | New search has been performed | Search updated. No new trials identified. |

| 1 July 1998 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

This review will no longer be updated by the review team. A new review team have prepared a new Cochrane Review (Kobayashi 2017) that combines the review by Lauzon 2001 with this review, to include all interventions for labour assessment and care to delay hospital admission.

Acknowledgements

None.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Labour diagnosis education versus standard care.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Visits to labour suite before active labour | 1 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.29 [‐0.47, ‐0.11] |

| 2 Out‐of‐hospital emergencies | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Artificial rupture of membranes | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Intrapartum analgesia | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Intrapartum oxytocics | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Forceps/vacuum extraction | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Caesarean section rates (overall) | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Caesarean section rates for labour dystocia | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Satisfaction with care | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Admission to neonatal intensive care | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Admission to labour ward on first visit | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Empowerment | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labour diagnosis education versus standard care, Outcome 1 Visits to labour suite before active labour.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bonovich 1990.

| Methods | Method of randomisation is unclear: 'study numbers were sequentially assigned and used to randomise subjects to the experimental or control group'. | |

| Participants | 245 nulliparous women > 16 years of age at 30+ weeks' gestation who were able to communicate effectively in English, at a single US hospital‐based outpatient obstetrical clinic. 37 (15%) were lost to follow up, due to incomplete hospital records or admission to hospital for complications before the onset of normal full‐term labour. | |

| Interventions | When participants had reached 37 weeks' gestation, interviews were conducted with the investigator to determine knowledge gained from family and friends regarding labour onset. Correct information was positively reinforced. Specific teaching re: palpation of uterine fundus, differentiation between Braxton‐Hicks and active labour contractions, timing of contractions, recognition of amniotic fluid, and pain perception. Teaching was reinforced at subsequent weekly antenatal visits. | |

| Outcomes | Mean number of visits to labour suite before onset of active labour (i.e. discharged undelivered). | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Contributions of authors

The first draft of the protocol and then the review and its updates were written by Leeanne Lauzon. The drafts were commented on by Ellen Hodnett. The studies were checked for inclusion independently by both review authors. The data were abstracted by Leeanne Lauzon and then checked by Ellen Hodnett. Final drafts were prepared by Leeanne Lauzon and checked by Ellen Hodnett.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of Toronto, Canada.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bonovich 1990 {published data only}

- Bonovich L. Recognizing the onset of labour. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 1990;19(2):141‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Delaram 2009 {published data only}

- Delaram M. The effects of consultation with mother in third trimester of pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes. Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (http://www.irct.ir/) (accessed 6 December 2010) 2009.

Lumluk 2011 {published data only}

- Lumluk T, Kovavisarach E. Effect of antenatal education for better self‐correct diagnosis of true labor: a randomized control study. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 2011;94(7):772‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Clarke 2000

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.1 [updated June 2000]. In: Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 4.1. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Crowther 1989

- Crowther C, Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Brown I. Monitoring the progress of labour. In: Chalmers I, Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC editor(s). Effective care in pregnancy and childbirth. Vol. 2, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

Gagnon 2007

- Gagnon AJ, Sandall J. Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth or parenthood, or both. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002869.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kobayashi 2017

- Kobayashi S, Hanada N, Matsuzaki M, Takehara K, Ota E, Sasaki H, Nagata C, Mori R. Assessment and support during early labour for improving birth outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011516.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lauzon 2001

- Lauzon L, Hodnett E. Labour assessment programs to delay admission to labour wards. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000936] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Simkin 1996

- Simkin P. The experience of maternity in a woman's life. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 1996;25(3):247‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thornton 1994

- Thornton JG, Lilford RJ. Active management of labour: current knowledge and research issues. BMJ 1994;309:366‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]