Introduction

Research on the predictors of opioid misuse (OM) initiation among justice-involved populations is critical to resolving the OM crisis in the United States (U.S.). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health defines OM as the non-medical use of prescription opioids or use of illicit opioids, such as heroin (SAMHSA, 2017). Adolescent OM is among the highest priority drug problems in the U.S. Recent research has underscored the importance of adult correctional populations in significantly reducing statewide OM and opioid-rated overdoses (Green et al., 2018). Identifying correlated of OM among JIC may likewise reduce statewide rates of OM and overdose among adolescents and adults.

Substantial research has demonstrated the importance of family structure in the etiology of adolescent substance abuse, with the preponderance of evidence indicating that those in two-parent households have a lower risk. However, nontraditional family structures are progressively common in modernity, and single-parent family structures are far prevalent among JIC than those in the general population. The current study investigates the association between different types of family structures and current OM among JIC. Understanding these relationships can not only provide insight on how modern family structures impact OM among JIC, but also inform the implementation of treatment programs in juvenile correctional settings that may prevent or reduce overall OM, overdose and overdose-related deaths.

Opioids

Between 2005 and 2010, there were 4,186 calls made to poison control centers for adolescent OM (Sheridan et al., 2016). With this upswing in calls to poison control centers, and even more adolescent opioid-related emergencies going unreported, it is imperative that adolescents are considered when addressing the opioid crisis (Sheridan et al., 2016). In a recent study, Boyd (2006) found that 12% of adolescents reported using opioids non-medically, and of those, 21% used them for purposes other than pain relief. The use of opioids in pediatric emergency medicine for adolescents grew from 16.5% to 23.8% between 2001 and 2010 (Mazer-Amirshahi, Mullins, Rasooly, van den Anker, & Pines, 2014). In more recent years, illicit opioids, such as heroin and fentanyl have become more available (Forsyth, Biggar, Chen, & Burstein, 2017; Garbutt, Kulka, Dodd, Sterkel, & Plax, 2018; O’Donnell, Gladden, & Seth, 2017). Whether obtained from doctors, household members or street dealers, more access to opioids elevates risk for misuse, which may be exacerbated for JIC in single-parent households.

Family Structure and Drug Use

There are multiple conceptual models that explain the effects of family structure on adolescent drug use including economic resources, residential mobility, parent-child socialization and stress. For many scholars, non-traditional (two-parent) family structures, such as single-parent families, represent family disruption rather than stability. Single-parent, grandparent-only, or no-parent family structures sometime result in harmful changes in parent/child roles, resources and security. These perspectives are corroborated by a burgeoning body of research documenting the adverse effects of living in a non-two-parent households on various outcomes (Bzostek & Beck, 2011; Choi, DiNitto, Marti, & Choi, 2017; Hemovich, Lac, & Crano, 2011; 1998; S.-A. Lee, 2018; Mitchell et al., 2015).

While scarce research has examined family structure and OM, substantial research has shown that adolescents from single-parent households are more prone to drug and alcohol use (Barrett & Turner, 2006; Waldron et al., 2014). Analyzing three years of data from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, Hoffmann and Johnson (1998) found that the risk of drug use (marijuana, other illicit drugs and alcohol) was highest among adolescents in father-custody families (father-only and father-stepmother families) and lowest in mother-father families, even after controlling for the effects of sex, age, race-ethnicity, family income and residential mobility. Data from the National Survey of Parents and Youth found that those in two-parent households were least likely to use drugs and were monitored more closely than single-parent youth (Hemovich et al., 2011). Another study found that adolescents living in rural two-parent households were 32% less likely to use prescription drugs non-medically than adolescents in single-parent households (Havens, Young, & Havens, 2011). Some evidence indicated that the effects of single-parent households varies by gender. Hemovich and Crano (2009) found that drug use among daughters living with single fathers significantly exceeded that of daughters living with single mothers, while gender of parent was not associated with sons’ usage (Hemovich & Crano, 2009).

Some research indicates that the relationship between family structure and delinquency is nuanced and single-parent households may actually be more protective than two-parent households in certain contexts (Ford-Gilboe, 2000). For example, when individuals terminate dysfunctional marriages, their children are at less risk for developing depression, anxiety and other pyschological problems (Kelly, 2003). Some research suggest that it is not the structure of the family itself, but rather instability in the family structure that are associated with adverse child health and behavioral outcomes (Bzostek & Beck, 2011; S.-A. Lee, 2018; Mitchell et al., 2015). Lee and McLanahan (2015) found that family instability had a causal effect on children’s development, but the effect depended on the context of the family structure transition, the population being examined and the outcome of interests (D. Lee & McLanahan, 2015).

The Current Study

Florida contains the third largest population of juveniles in the criminal justice system in the U.S. and the state has seen a dramatic increase in opioid-related overdose deaths in the past decade(O’Donnell et al., 2017). JIC have a higher prevalence of living in single-parent households and substance abuse than youth in the general population. However, our review of the literature could identify a single study of family structure and OM among JIC. Data from statewide samples showed that over 80% of JIC in Florida reported living in a non-traditional family structures (Michael T. Baglivio et al., 2014; Johnson, 2017). An earlier study found that half of JIC in detention facilities had one or more substance use disorders (McClelland, Elkington, Teplin, & Abram, 2004).

The aim of the current study was to investigate the association between types of family structures (single-parent, grand-parent only and two-parent households) and OM among JIC. Drawing on empirical evidence, this study hypothesizes that single-parent and grant-parent only households will be associated with a higher likelihood of OM among Florida JIC compare to two-parent households. Prior research found evidence of developmental sensitives to family transitions (Kelly, 2003) and justice-involvement (DeLisi, Neppl, Lohman, Vaughn, & Shook, 2013), therefore we will examine the interaction effects of family structure and age. It is also hypothesized that younger adolescents in single-parent households will have a higher likelihood of OM than older adolescents in sing-parent households. To test these hypotheses, the study leverages statewide data from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (FLDJJ). Other known explanations of adolescent OM are considered: race, gender, age, family income, history of somatic complaints, history of mental health diagnoses, level of optimism, number of adjudicated felonies and school enrollment status.

Methods

Data

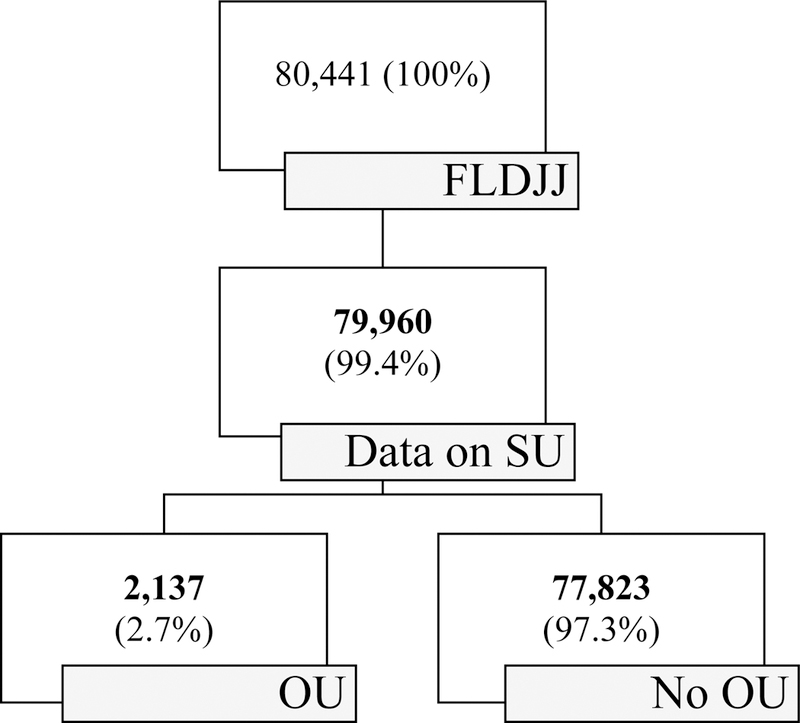

The study uses statewide data from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (FLDJJ). FLDJJ is a state agency of Florida that manages minors who were arrested for delinquency and operates juvenile detention centers. Since 2004, FLDJJ has collected data on all youth who were arrested using a comprehensive assessment and case management process. When a minor is arrested in Florida, they complete an enrollment process to enter the FLDJJ system. As a part of the enrollment process, all youth are administered the Positive Achievement Change Tool (PACT) assessment. The PACT instrument has been validated across multiple samples of FLDJJ data published in several peer-reviewed journals (M. T. Baglivio & Jackowski, 2013). Trained personnel conduct semi-structured interviews using the PACT software. The interface guides all aspects of data collection; it includes open-ended questions, an interview guide, the PACT manual and coding techniques. This report includes 80,441 JIC in the FLDJJ PACT dataset; <1% (n=481) of the total cases were omitted due to missing data on substance use (SU), resulting in a final dataset of 79,960 individuals.

The population of 79,960 represents all youth who entered the FLDJJ from 2007 to 2015, completed the Full PACT assessment, reached the age of 18 by year 2015 and had data on the current SU question. Nearly 38.3% were non-Latina/o White (n=30,591), 45.6% of subjects were non-Latina/o Black or African American (n=36,443), 15.7% were Latina/o (n=12,536) and 0.5% were another race (n=390). Roughly 21.9% of the sample were female (n= 17,497) and the mean age in 2007 was 14. See Figure 1 for a flow diagram of the sample.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of FLDJJ Data on OM.

Note: <1% (n=481) of 80,441 individuals were omitted from the study due to missing data on SU.

Measures

Opioid misuse.

The FLDJJ criteria for current opioid misuse, abbreviated as OM, was positive urinalysis or other evidence of illicit opioid or non-medical use prescription opioid consumption within the past-30 days, abbreviated P30D, at the final screen. OM included heroin and other opioids such as Dilaudid, Demerol, Percodan, Codeine, Oxycontin, etc.). Responses were coded into a dichotomous measure that reported whether or not the youth met the FLDJJ criteria for P30D OM. The response items were (0) no, did not meet FLDJJ criteria for P30D OM” or (1) yes, P30D OM as indicated by urine analysis or evidence.”

Family structure.

The type of family structure referred to different types of living arrangements. The PACT interview guide ask the FLDJJ interviewers to identify all persons with whom youth is currently living. The process resulted in a thirteen-item categorical variable. Response options were (1) both parents, (2) single mother, (3) single father, (4) mother and stepfather, (5) father and stepmother, (6) grandparents, (7) other relatives, (8) the ward of an older sibling, (9) foster or group home, (10) paramour, (11) friends, (12) alone and (13) transient. These responses were then re-coded into a four-item categorical variable. The mutually exclusive categories were (0) single-parent household, (1) grandparent-only household, (2) two-parent household and (3) other type of family structure. A single-parent household refers to when a child lives with one parent without a co-parent or partner in the household. A two-parent household referred to co-parenting adults living in the same household. They may be biological, adoptive, or step-parents.

Control variables.

The study adjusts for known predictors of P30D OM (race, gender, age, family income, history of somatic complaints, history of mental diagnoses, history of depression, level of optimism, number of adjudicated felonies and school enrollment status). Race was by a four-item categorical variable where the youth was asked what race they identify as. Response options were (0) White, (1) Black, (2) Hispanic and (3) other.

Gender was reported by FLDJJ as the “sex of the offender” with the categories male and female (0= male, 1= female). Age was operationalized by date of birth in 2007, resulting in a continuous variable ranging from 10 to 18 years of age. Family income was measured through a four-item ordinal variable reporting the combined annual income of the youth and family. Response options were (0) under $15,000, (1) from $15,000 to $34,999, (2) from $35,000 to $49999 and (3) $50,000 and above.

History of somatic complaints was measured by a four-item ordinal variable reporting the total number of lifetime somatic complaints. Response options were (1) no history of somatic complaints, (2) a history of one or two somatic complaints, (3) a history of three or four somatic complaints and (4) a history of five or more somatic complaints. History of mental health diagnosis was measured by a dichotomous variable reporting the youth’s lifetime mental health diagnoses at intake. These included schizophrenia, bi-polar, mood, thought, personality, and adjustment disorders, but exclude conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, substance abuse, and ADHD. All data was validated or confirmed by a healthcare professional. Response items were (0) no history of mental health diagnosis or (1) a history of one or more mental health diagnoses. History of depression-anxiety was by a four-item ordinal variable reporting their history of depression-anxiety. Response items were (1) no history of depression-anxiety, (2) a history of occasional depression-anxiety, (3) a history of consistent depression-anxiety and (4) a history of impairment from depression-anxiety. Optimism level was measured by a four-item ordinal variable reporting their current level of aspirations. Response options were (1) high aspirations, a sense of purpose, committed to a better life, (2) normal aspirations, some sense of purpose, (3) low aspirations and little sense of purpose or plans for better and (4) believes nothing matters, expects to be dead soon.

Adjudicated felonies were by an ordinal variable reporting the actual number of youth’s felony adjudications in the FLDJJ system. The categories were (0) none, (1) one, (2) two, or (3) three or more. Current enrollment status referred to youth’s middle or high school enrollment status in the P30D. It was operationalized through a four-item categorical variable reporting enrollment status at intake. Response options were (0) enrolled or graduated, (1) suspended, (2) dropped out, or (3) expelled.

Analytical procedures

Data analysis was conducted using Stata Statistical Software, version 15 and 13 SE (StataCorp, 2017). A complete case analysis was appropriate given that there was minimal missing data (<1%) that was Missing Completely At Random and the sample size was large. Demographic data were summarized using descriptive statistics. A chi-square test of independence was performed to test whether there were significant relationships between the categorical variables and OM. Multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals. The predictive margins were estimated (using the STATA margins procedures) to estimate and plot interaction effects. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to confirm adequate model fit.

Results

In the total sample (79,960), 2.7% (2,137) met criteria for P30D OM and 44.3% lived in single-parent households. The P30D group had fewer single-parent households compared to the non-P30D group (35.0% versus 44.5%). The unadjusted odds ratios indicated that JIC in grandparent-only households had a 62% increased likelihood of P30D OM compared to JIC in single-parent households (unadjusted odds ratio: 1.62; 95% CI, 1.38–1.89). Also, compared to JIC in single-parent households, those in two-parent households were 63% as likely (unadjusted odds ratio: 1.63; 95% CI, 1.46–1.81) and those in other types of households were 35% as likely (unadjusted odds ratio: 1.35; 95% CI, 1.21–1.50) as those in single-parent households. Among the P30D OM group, 80.6% were White, 8.3% were Black and 10.2% were Latina/o. Among those who were assessed but did not meet criteria for P30D OM, 37.1% were White, 46.6% were Black and 15.8% were Latina/o. For complete descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis, see Table 1-A and Table 1-B.

Table 1-A.

Characteristics of justice-involved children by past-30 day opioid misuse (P30D OM).

| Total (n=79.960) |

No P30D OM (n=77,823) |

P30D OM (n=2,138) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Family structure | ||||||

| Single-parent household | 35,388 | 44.3 | 34,641 | 44.5 | 747 | 35.0 |

| Grandparent-only household | 6,293 | 7.9 | 6,081 | 7.8 | 212 | 9.9 |

| Two-parent | 17,123 | 21.4 | 16,543 | 21.3 | 580 | 27.1 |

| Other | 21,156 | 26.5 | 20,558 | 26.4 | 598 | 28.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 30,591 | 38.3 | 28,868 | 37.1 | 1,723 | 80.6 |

| Black | 36,443 | 45.6 | 36,266 | 46.6 | 177 | 8.3 |

| Latina/o | 12,536 | 15.7 | 12,318 | 15.8 | 218 | 10.2 |

| Other | 390 | 0.5 | 371 | 0.5 | 19 | 0.9 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 62,463 | 78.1 | 61,006 | 78.4 | 1,457 | 68.2 |

| Female | 17,497 | 21.9 | 16,817 | 21.6 | 680 | 31.8 |

| Household income | ||||||

| Under $15000 | 20,715 | 25.9 | 20,248 | 26.0 | 467 | 21.9 |

| From $15000 to $34999 | 41,883 | 52.4 | 40,864 | 52.5 | 1,019 | 47.7 |

| From $35000 to $49999 | 11,842 | 14.8 | 11,445 | 14.7 | 397 | 18.6 |

| $50000 & over | 5,520 | 6.9 | 5,266 | 6.8 | 254 | 11.9 |

| History of somatic complaints | ||||||

| None | 69,008 | 86.3 | 67,410 | 86.6 | 1,598 | 74.8 |

| One or two | 9,641 | 12.1 | 9,196 | 11.8 | 445 | 20.8 |

| Three or four | 834 | 1.0 | 775 | 1.0 | 59 | 2.8 |

| Five or more | 477 | 0.6 | 442 | 0.6 | 35 | 1.6 |

Data displayed as column percent. The data continues in Table 1-B.

Table 1-B.

Characteristics of justice-involved children by past-30 day opioid misuse (P30D OM) (continued).

| Total (n=79.960) |

No P30D OM (n=77,823) |

P30D OM (n=2,138) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| History of mental diagnosis | ||||||

| None | 66,469 | 83.1 | 65,019 | 83.5 | 1,450 | 67.9 |

| Yes, history of diagnosis | 13,491 | 16.9 | 12,804 | 16.5 | 687 | 32.1 |

| History of depression-anxiety | ||||||

| None | 50,633 | 63.3 | 49,812 | 64.0 | 821 | 38.4 |

| Occasional | 21,986 | 27.5 | 21,176 | 27.2 | 810 | 37.9 |

| Consistent | 6,247 | 7.8 | 5,837 | 7.5 | 410 | 19.2 |

| Impairment | 1,094 | 1.4 | 998 | 1.3 | 96 | 4.5 |

| Optimism level | ||||||

| High | 10,858 | 13.6 | 10,763 | 13.8 | 95 | 4.4 |

| Normal | 44,347 | 55.5 | 43,443 | 55.8 | 904 | 42.3 |

| Low | 23,856 | 29.8 | 22,781 | 29.3 | 1,075 | 50.3 |

| Very low | 899 | 1.1 | 836 | 1.1 | 63 | 2.9 |

| Adjudicated felonies | ||||||

| None | 24,175 | 30.2 | 23,503 | 30.2 | 672 | 31.4 |

| One | 34,009 | 42.5 | 33,137 | 42.6 | 872 | 40.8 |

| Two | 13,793 | 17.2 | 13,396 | 17.2 | 397 | 18.6 |

| Three or more | 7,983 | 10.0 | 7,787 | 10.0 | 196 | 9.2 |

| Current school enrollment | ||||||

| Enrolled or graduated | 41,069 | 51.4 | 40,352 | 51.9 | 717 | 33.6 |

| Suspended | 4,813 | 6.0 | 4,707 | 6.0 | 106 | 5.0 |

| Dropped out | 26,018 | 32.5 | 25,036 | 32.2 | 982 | 46.0 |

| Expelled | 8,060 | 10.1 | 7,728 | 9.9 | 332 | 15.5 |

Note. Data displayed as column percent. The data are a continuation of Table 1-A.

Table 2 shows the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis estimating the association between family structure and P30D OM. The adjusted model controlled for race, gender, age, family income, history of somatic complaints, history of mental diagnosis, history of depression, level of optimism, number of adjudicated felonies and current school enrollment status. The hypothesis was not supported by the evidence. The adjusted odds ratios (aOR) indicated that JIC in grandparent-only households were 28% as likely to meet criteria for P30D OM as JIC in single-parent households (aOR: 1.28; 95% CI, 1.09–1.50). Also, compared to JIC in single-parent households, those in two-parent were 16% as likely (aOR: 1.16; 95% CI, 1.03–1.31). The differences in P30D OM between JIC in single-parent households versus other types of family structures was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Logistic regression estimating past-30 day opioid misuse.

| AOR | CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Family structure (ref=single-parent household) | - | - |

| Grandparent-only household | 1.28** | [1.09,1.50] |

| Two-parent household | 1.16* | [1.03,1.31] |

| Other | 0.92 | [0.82,1.03] |

| Race (ref=white) | - | - |

| Black | 0.12*** | [0.10,0.14] |

| Latina/o | 0.46*** | [0.39,0.53] |

| Other | 1.06 | [0.66,1.70] |

| Sex (ref=male) | - | - |

| Female | 1.50*** | [1.35,1.66] |

| Age | 0.95*** | [0.93,0.97] |

| Family income (ref=under $15k) | - | - |

| $15000 to $34999 | 1.07 | [0.95,1.20] |

| $35000 to $49999 | 1.26** | [1.09,1.46] |

| $50000 & over | 1.59*** | [1.34,1.89] |

| History of somatic complaints (ref=none) | - | - |

| One or two | 1.21** | [1.07,1.36] |

| Three or four | 1.48** | [1.11,1.98] |

| Five or more | 1.29 | [0.89,1.89] |

| History of mental health diagnoses (ref=none) | - | - |

| Mental health diagnoses | 1.07 | [0.96,1.19] |

| History of depression-anxiety (ref=none) | - | - |

| Occasional | 1.55*** | [1.39,1.72] |

| Consistent | 2.03*** | [1.76,2.34] |

| Impairment | 2.26*** | [1.76,2.89] |

| Optimism (ref=high aspirations) | - | - |

| Normal optimism | 2.13*** | [1.71,2.64] |

| Low optimism | 4.31*** | [3.46,5.36] |

| Very low optimism | 7.02*** | [4.95,9.94] |

| Adjudicated felonies (ref=none) | - | - |

| One | 1.16** | [1.04,1.29] |

| Two | 1.36*** | [1.18,1.55] |

| Three or more | 1.30** | [1.09,1.55] |

| Enrollment status (ref=enrolled or graduated) | - | - |

| Suspended | 1.28* | [1.03,1.59] |

| Dropped out | 1.86*** | [1.67,2.06] |

| Expelled | 2.24*** | [1.94,2.58] |

| Constant | 0.01*** | [0.01,0.02] |

| Observations | 79,960 | |

Note: aOR=Adjusted odds ratios. 95% confidence intervals (CI) in brackets.

p <0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

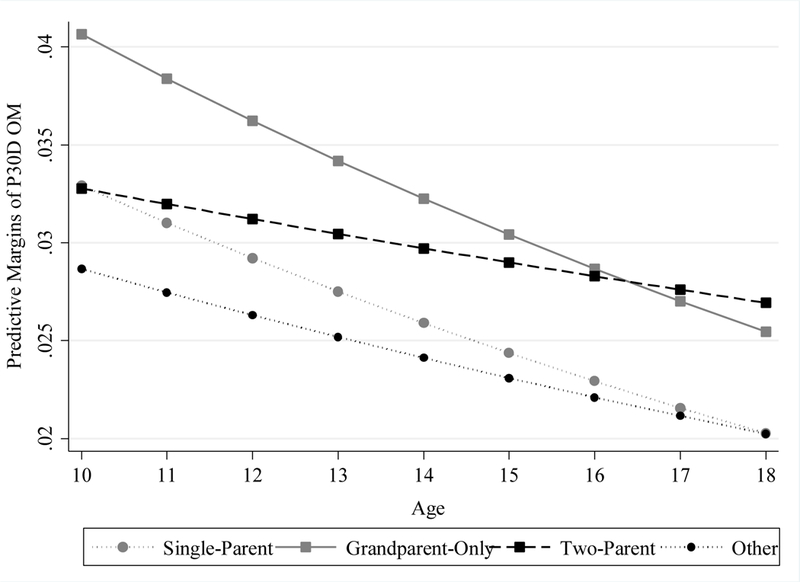

To examine whether the association between family structure and OM varied by age, the study estimated the predictive margins of the interaction between family structure types and age using Stata’s margins procedure. For a one unit increase in age in 2007, there was a 5% decreased chance of P30D OM (aOR: 0.95; 95% CI, 0.93–0.97), and there were significance differences in the effect of family structure by age. JIC 10–15 years of age living in grandparent-only households had a higher risk of OM than older JIC living in grandparent-only households. JIC 16–18 years of age who lived in two-parent households had a higher risk than other 16–18 year-olds in other family structures but lower risk than 10–15 year olds in two-parent households. The predictive margins were graphically displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Predictive margins of past-30 day opioid misuse (P30D OM) by family structure and age (n=79,960).

Compared to Whites, Blacks had an 88% decreased likelihood of P30D OM (aOR: 0.12; 95% CI, 0.10–0.14) and Latina/o had a 54% decreased likelihood (aOR: 0.45; 95% CI, 0.39–0.53). Females were 1.50 times as likely as males to meet criteria for P30D OM (aOR: 1.50; 95% CI, 1.35–1.66). Compared to those with family income levels below $15,000, JIC in the $35000 to $49,999 income bracket were 1.26 times as likely (aOR: 1.26; 95% CI, 1.09–1.46) and those in the $50,000 and over income bracket were 1.59 times as likely to meet criteria for P30D OM (aOR: 1.59; 95% CI, 1.34–1.89). Compared to those with no history of somatic complaints, those with one or two were 21% as likely (aOR: 1.21; 95% CI, 1.07–1.36) and those with three or four were 48% as likely to meet criteria for P30D OM (aOR: 1.48; 95% CI, 1.11–1.98). History of mental diagnosis was not significant.

Compared to JIC with no history of depression-anxiety, those with consistent depression (aOR: 2.03; 95% CI, 1.76–2.34) or impairment due to depression (aOR: 2.26; 95% CI, 1.76–2.89) were more than twice as likely to meet P30D OM criteria. Compared to those with high optimism, those with normal optimism were twice as likely (aOR: 2.13; 95% CI, 1.71–2.64), those with low optimism were more than 4 times as likely (aOR: 4.31; 95% CI, 3.46–5.36), those with very low optimism were over 7 times as likely to meet criteria for P30D OM (aOR: 7.02; 95% CI, 4.95–9.94). JIC with one felony were 16% as likely as those with no felonies (aOR: 1.16; 95% CI, 1.04–1.29). Those with two (aOR: 1.36; 95% CI, 1.18–1.55) or three felonies (aOR: 1.29; 95% CI, 1.08–1.53) were approximately 30% as likely to meet criteria for P30D OM as those with no felonies. Lastly, compared to those who were enrolled or graduated, those who were suspended were 28% as likely (aOR: 1.28; 95% CI, 1.03–1.59), those who were dropped out were 86% as likely (aOR: 1.86; 95% CI, 1.67–2.06) and those who were expelled were more than twice as likely to meet criteria for P30D OM (aOR: 2.24; 95% CI, 1.94–2.58).

Discussion

Synopsis and Interpretations

In a statewide sample of 79,960 JIC in Florida, 2.7% met criteria for P30D OM. This is substantial given that less than 8% of those who met criteria for P30D OM were over the age of 16 at the first screen. More than 38% of P30D users were 13 to 14 years of age. Though these data are largely drawn from urine analysis, underestimation of OM is possible. Many users may have simply evaded detection or failed to disclose. The fact that FLDJJ data only includes youth who age-out of the system, the data may not reflect the surge of OM in more recent years because it excluded youth who have not yet turned 18 years old.

Nearly 73% of the sample did not live in a two-parent household, including 35% who lived in single-mother or single-father households. Unexpectedly, there was a higher proportion of two-parent and grandparent-only households among those who met criteria for P30D OM than the non-P30D OM group. Family structures with more adults, especially older adult, are more likely to have prescription opioids in the household. Single-parent family structures can be associated with strain, such as diminished resources or the stress of experiencing parental separation or divorce, that can drive adolescents to substance abuse as a coping mechanism (Barrett & Turner, 2006; Hemovich & Crano, 2009). However, the strain of a single-parent household may not be as relevant to OM as the increase in access to prescription opioids associated with two-parent and grandparent-only households. These nuances may be uncovered in future research that examine family structure and OM while controlling for the presence of prescription opioids in the household. On the other hand, youth may not have used prescription opioids, but rather heroin, fentanyl, or other illicit opioids. As some scholars have proposed (Ford-Gilboe, 2000; Kelly, 2003; D. Lee & McLanahan, 2015), perhaps the type of family structure is not as important as the quality of the family structure; single-parent household can be more functional in certain contexts than two-parent households and other family structures.

In addition, the family structure-OM relationship varied by age. Though the younger cohort had a higher risk on average, the highest predicative margins of P30D OM were observed among 10–15 year-olds in grandparent-only households and 16–18 year-olds in two-parent households. The results also show striking racial differences in P30D OM. This could be due to issues with disclosure of OM among minority youth. However, it is less likely due to the fact that the data relies on official documents, such as urine evidence. In addition, minority youth are not substantially under-reporting other drug types. Another explanation could be that racial/ethnic minorities have less access to healthcare that, coupled with racial biases in prescription opioid prescribing practices, can result in a significantly less chance that minority JIC can obtain opioids compared to White JIC.

Limitations

Despite its relevance and scientific merit, the study had limitations that must be considered before discussing the interpretations of the findings and their implications. The cross-sectional data limits the ability to establish either causal conclusions or the exact temporal sequence between the exposure, single-parent household, and the outcome, OM. The sample is representative of FLDJJ, but it may not be appropriate to extend conclusions from this study to all JIC in the United States. The measure of OM combines prescription opioids and illegal opioids. Future studies should distinguish opioid types to identify important differences among opioid types. There are other relevant factors that could not be controlled for using the dataset, such as the presence of opioids in the household. Scholars should build upon the current study and address these limitation in future research.

Implications

Conventional notions of two-parent households as the gold standard for healthy child development may be insufficient and antiquated. Though single-parent households can cause strain on the parent and the child, the findings suggest that JIC in two-parent and grandparent only households have higher risks of OM than those in single-parent households. Adolescent substance abuse interventions and efforts to identify risk factors should focus on the quality of the family structure rather than the type of family structure. The benefits of a two-parent household may be undermined by dysfunctional relationships and increased access to prescription medicine and other substances. Two-parent and grandparent-only family structures may benefit from safe opioid disposal programs such as the Deterra drug deactivation pouch. Because risk of relapse and overdose are significantly higher after incarceration (Green et al., 2018), correctional facilities can equip formerly incarcerated individuals and their families with prescription medicine disposal systems and substance abuse treatment upon re-entry into their communities. In addition, the interaction between family structure and age indicated potential (age-related) developmental sensitivities to certain family structures and related parenting practices. These nuances must be considered in the development of intervention programs.

Impairment due to depression, low levels of optimism and school dropout were associated with a significantly higher risk, 2–9 times increased chances of P30D OM. These factors are often indicators of distress. Trauma-informed programs have been shown to be effective in reducing substance misuse (McHugo et al., 2005). Najavits and colleagues (2006) found evidence that the Seeking Safety intervention effectively reduced substance misuse by addressing substance abuse and childhood adversity. The Florida juvenile justice community can benefit from widely implementing evidence-based programs such as these that address trauma exposure and substance use simultaneously. Alternatively, the root cause of adolescent OM may not be trauma exposure, but instead, a lack of life skills. Programs that 1) teach healthy ways to manage stress and depression, 2) develop high levels of optimism and 3) foster school completion and high academic expectations may be the most effective in reducing adolescent OM.

As federal and state agencies launch initiatives to support families and communities that suffer from the opioid crisis, stakeholders must ensure that resources are not disproportionately allocated in such a manner that amplifies health disparities. Research on OM among underserved populations can help ensure that adequate resources are equally allocated to minority and disadvantaged communities. One of the most vulnerable populations, JIC, are widely understudied in substance abuse research. Without adequate attention in research and access to treatment services, JIC and their families may suffer the harshest consequences of the opioid epidemic.

Conclusions

Children in the juvenile justice system are often understudied and underserved but play a critical role in understanding and resolving the opioid epidemic. Justice-involved children in Florida who lived in a single-parent household were associated with less risk of P30D OM as those in two-parent and grandparent-only households. Interactions between family structure and age indicated that the family structure with highest risk of P30D OM among JIC under 16 years of age was grandparent-only households. However, among JIC 16–18 years of age two-parent households had the highest risk. In assessing risk for drug abuse, stakeholders must consider the quality of the family environment rather than the type of family structure. Safe opioid disposal practices in households with multiple adults may reduce risk of misuse and overdose.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

This research was supported by the NIDA T32 training grant at the UF Substance Abuse Training Center in Public Health from the National Institutes of Health under award number T32DA035167 (Dr. Linda B. Cottler, PI) and by Dr. Micah E. Johnson. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice.

Author biography:

Micah E. Johnson, PhD, MA, is a National Institute of Drug Abuse Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Epidemiology in the College of Medicine and Public Health and Health Professionals at the University of Florida. His research focuses on substance use among pediatric health disparity populations. He founded the Study of Teen Opioid Misuse Laboratory at the University of Florida.

References

- Baglivio MT, Epps N, Swartz K, Huq MS, Sheer A, & Hardt NS (2014). The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in the lives of juvenile offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(2), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, & Jackowski K (2013). Examining the validity of a juvenile offending risk assessment instrument across gender and race/ethnicity. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 11(1), 26–43. doi: 10.1177/1541204012440107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AE, & Turner RJ (2006). Family structure and substance use problems in adolescence and early adulthood: examining explanations for the relationship. Addiction, 101(1), 109–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01296.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, & Young A (2006). Adolescents’ motivations to abuse prescription medications. Pediatrics, 118(6), 2472–2480. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzostek SH, & Beck AN (2011). Familial instability and young children’s physical health. Social Science & Medicine, 73(2), 282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Marti CN, & Choi BY (2017). Association of adverse childhood experiences with lifetime mental and substance use disorders among men and women aged 50+years. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(3), 359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi M, Neppl TK, Lohman BJ, Vaughn MG, & Shook JJ (2013). Early starters: Which type of criminal onset matters most for delinquent careers? Journal of Criminal Justice, 41(1), 12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2012.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M (2000). Dispelling myths and creating opportunity: a comparison of the strengths of single-parent and two-parent families. ANS Adv Nurs Sci, 23(1), 41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth CJ, Biggar RW, Chen J, & Burstein K (2017). Examining heroin use and prescription opioid misuse among adolescents. Criminal Justice Studies. doi: 10.1080/1478601X.2017.1286836 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt JM, Kulka K, Dodd S, Sterkel R, & Plax K (2018). Opioids in adolescents’ homes: prevalence, caregiver attitudes, and risk reduction opportunities. Acad Pediatr. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Clarke J, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Marshall BDL, Alexander-Scott N, Boss R, & Rich JD (2018). Postincarceration fatal overdoses after implementing medications for addiction treatment in a statewide correctional system. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 405–407. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Young AM, & Havens CE (2011). Nonmedical prescription drug use in a nationally representative sample of adolescents evidence of greater use among rural adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(3), 250–255. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemovich V, & Crano WD (2009). Family structure and adolescent drug use: an exploration of single-parent families. Subst Use Misuse, 44(14), 2099–2113. doi: 10.3109/10826080902858375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemovich V, Lac A, & Crano WD (2011). Understanding early-onset drug and alcohol outcomes among youth: the role of family structure, social factors, and interpersonal perceptions of use. Psychol Health Med, 16(3), 249–267. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2010.532560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JP, & Johnson RA (1998). A national portrait of family structure and adolescent drug use. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 633–645. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME (2017). Childhood trauma and risk for suicidal distress in justice-involved children. Children and Youth Services Review, 83, 80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.10.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JB (2003). Changing perspectives on children’s adjustment following divorce: A view from the United States. Childhood, 10(2), 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, & McLanahan S (2015). Family structure transitions and child development: Instability, selection, and population heterogeneity. American sociological review, 80(4), 738–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S-A (2018). Family structure effects on student outcomes. In Parents, their children, and schools (pp. 43–76): Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mazer-Amirshahi M, Mullins PM, Rasooly IR, van den Anker J, & Pines JM (2014). Trends in prescription opioid use in pediatric emergency department patients. Pediatric Emergency Care, 30(4), 230–235. doi: 10.1097/pec.0000000000000102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GM, Elkington KS, Teplin LA, & Abram KM (2004). Multiple substance use disorders in juvenile detainees. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(10), 1215–1224. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000134489.58054.9c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugo GJ, Kammerer N, Jackson EW, Markoff LS, Gatz M, Larson MJ, . . . Hennigan K (2005). Women, Co-occurring Disorders, and Violence Study: Evaluation design and study population. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(2), 91–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C, McLanahan S, Hobcraft J, Brooks-Gunn J, Garfinkel I, & Notterman D (2015). Family structure instability, genetic sensitivity, and child well-being. American Journal of Sociology, 120(4), 1195–1225. doi: 10.1086/680681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Gallop RJ, & Weiss RD (2006). Seeking safety therapy for adolescent girls with PTSD and substance use disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 33(4), 453–463. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9034-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell JK, Gladden RM, & Seth P (2017). Trends in deaths involving heroin and synthetic opioids excluding methadone, and law enforcement drug product reports, by census region—United States, 2006–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 66(34), 897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2017). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 national survey on drug use and health. NSDUH Series H-52. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan DC, Laurie A, Hendrickson RG, Fu R, Kea B, & Horowitz BZ (2016). Original contributions: association of overall opioid prescriptions on adolescent opioid abuse. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 51, 485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata statistical software: Release 15. In. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron M, Grant JD, Bucholz KK, Lynskey MT, Slutske WS, Glowinski AL, . . . Heath AC (2014). Parental separation and early substance involvement: Results from children of alcoholic and cannabis dependent twins. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 134, 78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]