Abstract

Degeneration of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the brain is the major cause for Parkinson’s disease (PD). While genetic loci and cellular pathways involved in DA neuron proliferation have been well documented, the genetic and molecular and cellular basis of DA cell survival remains to be elucidated. Recently, studies aimed to uncover the mechanisms of DA neural protection and regeneration have been reported. One of the most recent discoveries, i.e., multi-function of human oncogene SCL/TAL interrupting locus (Stil) in DA cell proliferation, neural protection, and regeneration, created a new field for studying DA cells and possible treatment of PD. In DA neurons, Stil functions through the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway by releasing the inhibition of SUFU to GLI1, and thereby enhances Shh-target gene transcription required for neural proliferation, protection, and regeneration. In this review article, we will highlight some of the new findings from researches relate to Stil in DA cells using zebrafish models and cultured mammalian PC12 cells. The findings may provide the proof-of-concept for the development of Stil as a tool for diagnosis and/or treatment of human diseases, particularly those caused by DA neural degeneration.

Subject terms: Cell death in the nervous system, Mechanisms of disease

FACTS

Stil is a human oncogene which may also function as ON-OFF switches that regulate the death and survival of neurons

Stil is required for neural proliferation and regeneration

Stil-mediated Shh signaling transduction protects dopaminergic neurons in response to toxic drug treatment

OPEN QUESTIONS

How to control the expression of Stil mRNA in neurons?

Does Stil play a role in regulation of neural function?

Can Stil be developed as a molecular marker for diagnosis of neural degeneration?

Introduction

The SCL/TAL interrupting locus (Stil) is a human oncogene that was originally identified from human T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia, where it functions as a hematopoietic transcription factor1. The sequence of Stil gene is highly conserved in vertebrate species2. In humans, the Stil transcript is comprised of 18 exons which yield a peptide of 1287 amino acids in 143-KD2,3. While STIL does not share any known structural motifs with other proteins, analyses of the human STIL sequence revealed some similarities between STIL and the C-terminus of cytokine TGF-β4 and the C-terminus of centriole duplication factor Ana25. STIL is expressed in all cell types examined so far6–10. In prometaphase-synchronized cells and mouse tumor cell lines, STIL functions as a cell cycle checkpoint protein that regulates the transition of mitotic entry during cell proliferation11. In developing human cancer cells, STIL is localized to the pericentriolar region of the centrosomes, where it regulates in spindle pole positioning as well as centriole formation and duplication12–14.

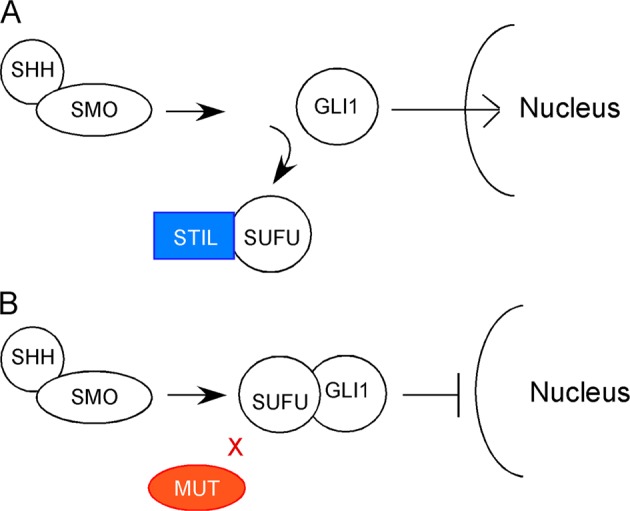

While ample proof of STIL functions in cancer can be found in the literature, evidence also exists that STIL is involved in the development and function of the nervous system. In mouse, for example, functional expression of Stil is required for setting the midline and left-right polarity of the central nervous system (CNS)15. In mutants which lack proper Stil expression and/or with defective structure of Shh receptors, the embryos develop abnormally and die at age of E11. Using molecular genetic approaches, Izraeli et al.15 and Kasai et al.16 demonstrated that Stil functions in the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway. Specifically, Stil regulates the transcription of Shh-target gene Gli1. Normally, GLI1 forms heterodimers after binding to cytoplasmic protein SUFU. The heterodimers cannot be translocated to the nucleus thereby the transcription of Gli1 gene is inhibited. When STIL is expressed, STIL binds SUFU, frees GLI1 from SUFU repression. Then, GLI1 can enter the nucleus, and gene transcription can start. If Stil is mutated, the transcription of Gli1 cannot be initiated (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Diagrams that illustrate the roles of STIL in the Shh pathway.

a Normally, STIL binds SUFU, releases SUFU’s suppression on GLI1, then GLI1 can be translocated to the nucleus for gene transcription. b When STIL is mutated, Shh down-stream signaling transduction cannot be completed because the SUFU-GLI1 heterodimers cannot enter the nucleus for gene transcription. (Modified from reference15)

Recent studies have shown that Stil plays important role for proliferation, survival, regeneration, and possibly functions in dopaminergic (DA) neurons17,18. In humans, DA-mediated neural transduction is required for integration of sensory-motor signals and the control of movement19–22. The lack of DA cells and/or malfunction of DA neural networks may lead to a variety of neurological diseases, such as PD23–26. In this article, we will review some of the findings relate to the roles of Stil in DA cells. The data presented in this article are obtained from studies conducted in zebrafish models and cultured mammalian DA cell lines. The results may provide insight for future development of Stil as a potential bio-marker for better understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying human neurological disorders.

Multi-function of STIL in DA cells

STIL protects DA cells

While most the studies related to Stil were carried out using cultured cancer cell lines and mouse models9,11,15,16,27–29, research that characterize Stil mutations that cause dramatic phenotypes (e.g., embryonic lethality, nervous system malfunction) can also be found by using other species, such as zebrafish. Pfaff et al.30 reported that in zebrafish, STIL is highly expressed in proliferating cells. During metaphase, STIL is concentrated in areas near the poles of the mitotic spindles. In cassiopeia (designated csp, which is a homolog of human Stil) mutants, the Stil gene is mutated, and the organization of spindle pole in proliferating cells is completely disrupted. Often, the mutants lack one or both centrosomes. As a consequence, the embryos develop abnormally and die between 7 and 10 days post-fertilization. In another study, Li and Dowling31 demonstrated that in zebrafish night blindness b (designated nbb; also a homolog of human Stil) mutants, not only the development but also the function of the CNS are interrupted. In homozygous nbb mutants, massive cell degeneration occurs in the developing brain, and the embryos die before 7 days post-fertilization. In heterozygous nbb mutants, animals are viable but after 9 months of age, abnormalities are found in the CNS, e.g., the number of retinal DA cells is decreases, and the animals become night blind particularly after prolonged dark adaptation. In addition, in nbb mutants the susceptibility of DA cells to neurotoxin is increased17, and the rate of DA cell regeneration is decreased32. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the nbb locus revealed a nucleotide substitution at a donor-splicing site in the Stil transcript, which results in a predicted truncated peptide with 301 amino acids17.

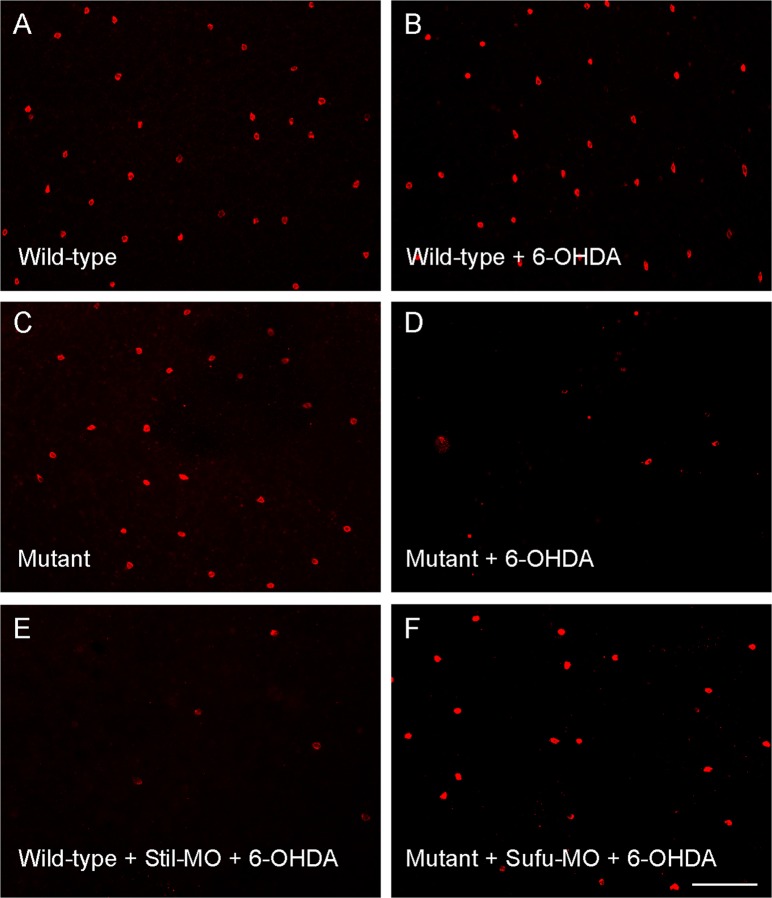

To investigate if the expression of Stil is required for maintaining the DA cells (e.g., whether or not the decrease of DA cells in nbb mutants is due to age-related neural degeneration), Li et al.17 examined the survival of DA neurons in zebrafish retinas in response to treatment with DA-specific neurotoxins, such as 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)33,34. They found that deficiency in Stil expression led to increases in toxic susceptibility in DA neurons. In wild-type zebrafish, for example, treatment with sub-toxic levels of 6-OHDA (0.33 µg/μl) produced no obvious effects on the survival of DA cells (Fig. 2a, b). In nbb mutants, however, the same treatment led to significant DA degeneration (Fig. 2c, d). The susceptibility of DA cells to neural toxins can be reversed by manipulating the levels of Shh signaling transduction, e.g., by inhibition of STIL expression using Stil-specific morpholinos (MOs), or increase of Shh signaling transduction by knocking-down SUFU expression with Sufu-specific MOs. In zebrafish, treatment with gene-specific MOs can efficiently knock-down their protein expressions35,36. In wild-type zebrafish, decreases in STIL expression (by Stil-MO) led to increases of the susceptibility of DA cell to sub-toxic levels of 6-OHDA. As a consequence, DA cell degeneration was observed when treated with sub-toxic levels of 6-OHDA (Fig. 2e). In contrast, in nbb mutants, inhibition of SUFU expression (by Sufu-MO, which then lifted its suppression to GLI1, and increased Gl1 transcription) lowered the susceptibility of DA cells to neural toxins and protected the DA cells after drug treatment (Fig. 2f).

Fig. 2. Fluorescent images of flat-mounted zebrafish retinas that show the DA cells (labeled with antibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase) after treatment with sub-toxic 6-OHDA.

a, b Wild-type retinas that received sham or sub-toxic 6-OHDA treatment. No differences in the number of DA cells were observed. c, d Mutant retinas that received sham or sub-toxic 6-OHDA treatment. The number of DA cells was decreased after drug treatment. e, f Wild-type and mutant retinas that received sub-toxic 6-OHDA injections, but previously treated with Stil- and Sufu-specific MOs, respectively. Note the increase of drug susceptibility (decreases in cell survival) in wild-type fish and the decrease of drug susceptibility (increases in cell survival) in mutant fish. Scale bar, 100 μm. (Modified from reference17)

STIL promotes DA regeneration

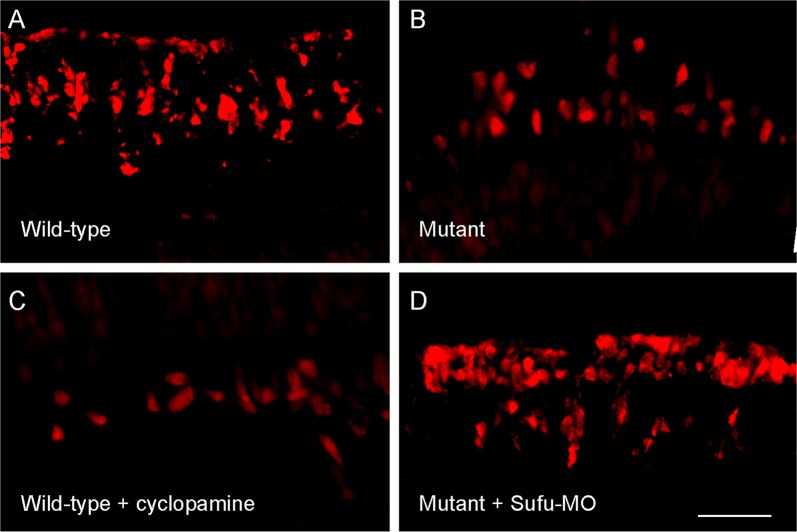

Zebrafish are capable to replace lost neurons by reactivation of stem cell-like glia cells37–42. In a research aimed to distinguish whether or not the decrease of DA neurons in nbb mutants is related to DA neural regeneration, Sun et al. (2014a) examined the proliferation of DA cells in adult zebrafish retinas after 6-OHDA induced neural degeneration. In this study, toxic levels of 6-OHDA (5.0 µg/μl) was applied in order to effectively induce the degeneration of DA cells. After a few days of 6-OHDA treatment, the samples were collected and labeled with antibodies against proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a marker protein that only expresses in proliferating cells38,43. In wild-type animals, after drug-induced cell death of DA cells, robust regeneration of DA cells occurred, e.g., PCNA-positive cells could be readily identified (Fig. 3a). In nbb retinas, however, in response to the same treatment, the rate of DA cell regeneration was decreased, e.g., the number of PCNA-positive cells was only 30–40% of the number of PCNA-positive cells counted in control retinas (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Fluorescent images of retinal sections that show DA cell regeneration.

a, b Sections from wild-type and nbb retinas. Note the decrease of PCNA labeling in the mutant. c A section from cyclopamine-treated wild-type fish. Note the decrease in the number of PCNA-positive cells. d A section from nbb fish that received Sufu-MO injection. Note the increase in the number of PCNA-positive cells. Scale bar, 100 μm. (Modified from reference32)

Because Stil functions in the Shh pathway, Sun et al.32 tested if the survival of DA cells is affected by Shh signaling transduction. The experiments were performed in wild-type animals in which the transduction of Shh signaling was blocked by steroidal alkaloid cyclopamine, and in nbb mutants in which the transduction of Shh signaling was enhanced by knock-down of SUFU expression with Sufu-MO. Previous studies have demonstrated that cyclopamine, an antagonist of SMO receptor in the Shh pathway, can efficiently block the Shh signaling transduction and lower the transcription of Gli144,45. In wild-type fish, treatment with cyclopamine decreased the rate of DA cell regeneration after 6-OHDA induced degeneration (Fig. 3c). In Sufu-MO treated nbb fish, after 6-OHDA treatment the number of cells that express PCNA-positive cells was increased to levels similar as seen in wild-type animals. Together, the data suggest that increases in Shh signaling transduction may rescue the defects in DA cell regeneration due to the expression of nbb mutation (Fig. 3d).

STIL induces mammalian DA cell proliferation

The roles of STIL expression in mammalian DA cell proliferation were evaluated using cultured PC12 cells18. The PC12 cells were originally derived from rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells46–48. Under normal culture conditions and with inductions by nerve growth factor (NGF), PC12 precursor cells can be proliferated and differentiated into DA cells49,50. The overexpression of Stil (by transfection with full-length human Stil sequence) increased the rate of cell proliferation of PC12 cells, by approximately 30% compared to control cells. In contrast, knock-down of Stil function (by Stil-specific shRNA) reduced the rate of PC12 cell proliferation, to a level approximately 45% of controls18.

To investigate whether or not STIL also functions in the Shh pathway as a de-repressor for proper signaling transduction in PC12 cells, Sun et al.51 examined the co-expression of STIL and Shh down-stream proteins, such as SUFU and GLI1, in PC12 cells. They found that both SUFU and GLI1 could be detected by anti-STIL antibody pull-down experiments. STIL and SUFU could also be detected by using anti-GLI1 antibody pull-down assays. These results provide evidence for the conserved roles of STIL in the Shh pathway in mammalian DA cells. The roles of Stil in Shh pathway in PC12 cells can also be demonstrated using pharmacological approaches. Carr et al.18 proposed that down-regulation of Shh signaling transduction by cyclopamine would mimic the proliferation defects caused by Stil-shRNA knock-down. They found that treatment with cyclopamine indeed reduced the proliferation rate of PC12 cells. Interestingly, overexpression of Stil was able to maintain a significant higher growth rate in the presence of cyclopamine. This suggests that when the initial Shh signaling is blocked, some of the down-stream signaling transduction could be continued by exogenous expression of STIL. That is, STIL binds SUFU and releases GLI1, then GLI1 enters the nucleus and starts gene transcription.

By the same token, whether or not the up-regulation of Shh signaling has a role on PC12 cell proliferation depends on the availability of STIL. This can be tested using pharmacologic approaches with purmorphamine while the expression of Stil is down- or up-regulated. It is known that purmorphamine functions as a SMO receptor agonist in the Shh pathway52–54. The application of purmorphamine increased the rate of PC12 cell proliferation18. However, when the expression of Stil mRNA was blocked by Stil-shRNA, purmorphamine could not fully rescue the defects in PC12 cell proliferation18. That suggests that activation the up-stream Shh signaling transduction is not able to bring the proliferation rate to control levels if the expression of down-stream genes (e.g., Stil) is inhibited. Based on these observations, Carr et al.18 concluded that STIL may induce cell proliferation by propagating the intracellular Shh signal for subsequent transcription of Shh-target genes, which are cell cycle specific.

STIL facilitates mammalian DA neural growth

Carr et al.18 examined the distribution of STIL in PC12 cells. They found that STIL was expressed in both developing and NGF-induced mature cells. In differentiated mature cells, STIL was ubiquitous expressed in the cytoplasm, nucleus, as well as in the neurites. The result is not unexpected, considering the primary roles of Stil in mitotic entry, spindle pole organization, centriole formation and duplication. The expression of STIL in mature cells indicates novel non-proliferative functions of STIL in post-mitotic and differentiate cells, such as neural survival, neurite extension, synthesis or release of neurotransmitters. This supports the notion that Stil is involved in the regulation of microtubule elongation55.

While STIL is required for DA cell prolifaration and growth, the expression of Stil is not involved in PC12 cell neural differentiation. After NGF induction, out-growth of neurites was observed in PC12 cells regardless the levels of Stil expression. Also, the rate neurite growth was indistinguishable among the cells in which the expression of Stil was knocked-down (by transfection with Stil-shRNA) or the expression of Stil mRNA was up-regulated (by transfection with plasmids that contained the full-length of human Stil DNA)18.

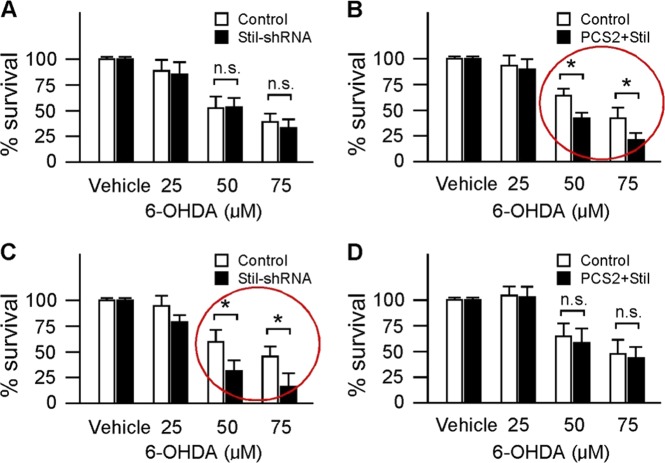

STIL in regulation of DA cell drug susceptibility

The effects of Stil expression on neural protection have been evaluated in cultured PC12 cells56. It appears that, to some extent, STIL may function as a “two-edged blade” that involves in both neural proliferation and degeneration, depends on the status of the cell. In proliferating PC12 cells, knock-down of STIL expression (by shRNA) produced no obvious effect on cells’ drug toxicity, e.g., cell death occured when treated with high doses of 6-OHDA, similar as observed in control cells (Fig. 4a). However, overexpression of Stil (by transfection of full-length human Stil DNA) increased the susceptibility of PC12 cells to neurotoxins, and when exposed to higher doses of 6-OHDA (e.g., 50 µM, 75 µM), excessive cell death was observed (Fig. 4b). In differentiated PC12 cells, Stil functions in opposite ways. That is, overexpression of Stil produced no effect on cell’s drug susceptibility as compared to control cells, but knock-down of Stil increased the drug susceptibility and when treated with higher doses of 6-OHDA, the rate of cell death was increased as compared to control cells (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4. Effects of Stil expression on PC12 cell drug susceptibility.

The rate of survival under control conditions (treated with vehicle solution) is normalized to 100%. a, b Percentage of cell survival after 6-OHDA treatment in proliferating cells. Note the increase of drug susceptibility after the overexpression of Stil (red circle). c, d Percentage of cell survival after 6-OHDA treatment in mature cells. Note the increase of drug susceptibility when the expression Stil is down regulated (red circle). Asterisks indicate statistical differences, p < 0.05; ns, not significant (Modified from reference56)

Conclusion

In summary, this paper provides evidence that through the Shh signaling transduction pathway the human oncogene Stil plays novel roles in DA cells. The expression of Stil is required for neural proliferation, survival, and regeneration. Considering the conserved roles of Stil in cell proliferation, the involvement of Stil in the Shh pathway, and the effect of Shh signaling in drug resistance, it is conceivable that Stil may function as an ON-OFF switch that controls the outcome of Shh signaling transduction, which in turns, regulates the fate of individual cell groups, for example, to be developed or undergo apoptosis. If this model proves true, then Stil may be considered as a bio-marker for basic and translational researches relate to human health, i.e., by analysis of the expression of Stil mRNA, the fate of certain cell types (e.g., cancer cells or neurons) can be predicted (e.g., proliferation, survival, or apoptosis). Future researches on Stil shall include but not limit to the characterization of the regulation of Stil expression in cancer cells and neurons, the interplay between Stil products and hormones that regulate cancer growth and neural degeneration, and the mechanisms of Stil-mediated Shh signaling transduction in drug resistance. At some point, one shall be able to control the molecular ON-OFF switch for Stil expression, and this will lead to either cell proliferation (e.g., neural regeneration) or apoptosis (e.g., cancer cells). It is expected that in the future Stil may be developed as a tool for diagnosis and/or treatment of human diseases.

Acknowledgements

Some of the works described in this review article were conducted in the author’s labs and their researches were supported in part by grants from NIH(Grant# R01EY013147) and NSFC (Grant# 81671242).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by R. Killick

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Aplan P, et al. Disruption of the human scl locus by illegitimate V-(D)-J recombinase activity. Science. 1990;250:1426–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.2255914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aplan P, Lombardi D, Kirsch I. Structural characterization of Sil, a gene frequently disrupted in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mol. Cell Biol. 1991;11:5462–5469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.11.11.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collazo-Garcia N, Scherer P, Aplan P. Cloning and characterization of a murine SIL gene. Genomics. 1995;30:506–513. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karkera J, et al. The genomic structure, chromosomal localization, and analysis of SIL as a candidate gene for holoprosencephaly. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;97:62–67. doi: 10.1159/000064057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens NR, Dobbelaere J, Brunk K, Franz A, Raff JW. Drosophila Ana2 is a conserved centriole duplication factor. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:313–323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen JS, et al. Proteomic characterization of the human centrosome by protein correlation profiling. Nature. 2003;426:570–574. doi: 10.1038/nature02166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basto R, et al. Flies without centrioles. Cell. 2006;125:1375–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelletier L, O’Toole E, Schwager A, Hyman AA, Muller-Reichert T. Centriole assembly in caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2006;444:619–623. doi: 10.1038/nature05318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.David A, et al. Lack of centrioles and primary cilia in STIL(−/−) mouse embryos. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:2859–2868. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.946830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moyer T, Clutario KM, Lambrus BG, Daggubati V, Holland AJ. Binding of STIL to Plk4 activates kinase activity to promote centriole assembly. J. Cell Biol. 2015;22:863–878. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201502088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erez A, et al. The SIL gene is essential for mitotic entry and survival of cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4022–4027. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitagawa D, et al. Spindle positioning in human cells relies on proper centriole formation and on the microcephaly proteins CPAP and STIL. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:3884–3893. doi: 10.1242/jcs.089888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arquint C, Sonnen KF, Stierhof Y, Nigg EA. Cell-cycle-regulated expression of STIL controls centriole number in human cells. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:1342–1352. doi: 10.1242/jcs.099887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vulprecht J, et al. STIL is required for centriole duplication in human cells. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:1353–1362. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izraeli S, et al. Genetic evidence that Sil is required for the sonic hedgehog response pathway. Genesis. 2001;31:72–77. doi: 10.1002/gene.10004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasai K, et al. SCL/TAL1 interrupting locus derepresses GLI1 from the negative control of suppressor-of-fused in pancreatic cancer cell. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7723–7729. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, et al. Functional expression of Stil protects retinal dopaminergic cells from neurotoxin-induced degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:886–893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.417089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr AL, et al. The human oncogene SCL/TAL1 interrupting locus is required for mammalian dopaminergic cell proliferation through the sonic hedgehog pathway. Cell Signal. 2014;26:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto N, Hanakawa T, Maki S, Graybiel AM, Kimura M. Role of corrected nigrostriatal dopamine system in learning to perform sequential motor tasks in a predictive manner. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;82:978–998. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.2.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szczypka MS, Rainey MA, Palmiter RD. Dopamine is required for hyperphagia in Lep(ob/ob) mice. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:102–104. doi: 10.1038/75484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djatchkova-Podkletnova I, Alho H. Alterations in the development of rat cerebellum and impaired behavior of juvenile rats after neonatal 6-OHDA treatment. Neurochem Res. 2005;30:1599–1605. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-8838-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gengler S, Mallot HA, Holscher C. Inactivation of the rat dorsal striatum impairs performance in spatial tasks and alters hippocampal theta in the freely moving rat. Behav. Brain Res. 2005;164:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foltynie T, Kahan J. Parkinson’s disease: An update on pathogenesis and treatment. J. Neurol. 2013;260:1433–1440. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6915-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2015;386:896–912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wijemanne S, Jankovic J. Dopa-responsive dystonia--clinical and genetic heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015;11:414–424. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarakad A, Jankovic J. Diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease. Semin Neurol. 2017;37:118–126. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1601888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izraeli S, et al. Expression of the SIL gene is correlated with growth induction and cellular proliferation. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:1171–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Izraeli S, et al. The SIL gene is required for mouse embryonic axial development and left-right specification. Nature. 1999;399:691–694. doi: 10.1038/21429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castiel A, et al. The stil protein regulates centrosome integrity and mitosis through suppression of chfr. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:532–539. doi: 10.1242/jcs.079731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfaff KL, et al. The zebra fish cassiopeia mutant reveals that SIL is required for mitotic spindle organization. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:5887–5897. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00175-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Dowling JE. Disruption of the olfactoretinal centrifugal pathway may relate to the visual system defect in night blindness b mutant zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:1883–1892. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01883.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun L, et al. The SCL/TAL1 interrupting locus (Stil) is required for cell proliferation in adult zebrafish retinas. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:6934–6940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.506295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Dowling JE. Effects of dopamine depletion on visual sensitivity of zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:1893–1903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01893.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cronin A, Grealy M. Neuroprotective and Neuro-restorative Effects of minocycline and rasagiline in a zebrafish 6-Hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. 2017;367:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bill BR, Petzold AM, Clark KJ, Schimmenti LA, Ekker SC. A primer for morpholino use in zebrafish. Zebrafish. 2009;6:69–77. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2008.0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bedell VM, Westcot SE, Ekker SC. Lessons from morpholino-based screening in zebrafish. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2011;10:181–188. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elr021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raya A, Consiglio A, Kawakami Y, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Izpisúa-Belmonte JC. The zebrafish as a model of heart regeneration. Cloning Stem Cells. 2004;6:345–351. doi: 10.1089/clo.2004.6.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vihtelic TS, Soverly JE, Kassen SC, Hyde DR. Retinal regional differences in photoreceptor cell death and regeneration in light-lesioned albino zebrafish. Exp. Eye Res. 2006;82:558–575. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raymond PA, Barthel LK, Bernardos RL, Perkowski JJ. Molecular characterization of retinal stem cells and their niches in adult zebrafish. BMC Dev. Biol. 2006;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Reilly-Pol T, Johnson SL. Melanocyte regeneration reveals mechanisms of adult stem cell regulation. Semin Cell Dev. Biol. 2009;20:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perlin JR, Robertson AL, Zon LI. Efforts to enhance blood stem cell engraftment: Recent insights from zebrafish hematopoiesis. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:2817–2827. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindsey BW, et al. The role of neuro-epithelial-like and radial-glial stem and progenitor cells in development, plasticity, and repair. Prog. Neurobiol. 2018;170:99–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fimbel SM, Montgomery JE, Burket CT, Hyde DR. Regeneration of inner retinal neurons after intravitreal injection of ouabain in zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:1712–1724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5317-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunn M, Mercola M, Moore D. Cyclopamine, a steroidal alkaloid, disrupts development of cranial neural crest cells in Xenopus. Dev. Dyn. 1995;202:255–270. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taipale J, et al. Effects of oncogenic mutations in Smoothened and Patched can be reversed by cyclopamine. Nature. 2000;406:1005–1009. doi: 10.1038/35023008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greene LA, Tischler AS. Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth-factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1976;73:2424–2428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greene LA, Rein G. Release of [3H]norepinephrine from a clonal line of pheochromocytoma cells (PC12) by nicotinic cholinergic stimulation. Brain Res. 1977;138:521–528. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90687-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rebois R, Reynolds E, Toll L, Howard B. Storage of dopamine and acetylcholine in granules of Pc12, a clonal pheochromocytoma cell-line. Biochemistry. 1980;19:1240–1248. doi: 10.1021/bi00547a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park YH, Kantor L, Wang KK, Gnegy ME. Repeated, intermittent treatment with amphetamine induces neurite outgrowth in rat pheochromocytoma cells (PC12 cells) Brain Res. 2002;951:43–52. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamboliev IA, Smyth LM, Durnin L, Dai Y, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN. Storage and secretion of beta-NAD, ATP and dopamine in NGF-differentiated rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009;30:756–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun L, et al. Characterization of SCL/TAL1 interrupting locus (Stil) mediated Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling transduction during mammalian dopaminergic cell proliferation. Biochem Biophy Res Comm. 2014;449:444–448. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sinha S, Chen J. Purmorphamine activates the hedgehog pathway by targeting smoothened. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:29–30. doi: 10.1038/nchembio753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lauth M, Bergstrom A, Shimokawa T, Toftgard R. Inhibition of GLI-mediated transcription and tumor cell growth by small-molecule antagonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8455–8460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.El-Akabawy G, Medina LM, Jeffries A, Price J, Modo M. Purmorphamine increases DARPP-32 differentiation in human striatal neural stem cells through the hedgehog pathway. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1873–1887. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Comartin D, et al. CEP120 and SPICE1 cooperate with CPAP in centriole elongation. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:1360–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li L, et al. A novel function of the human oncogene Stil: Regulation of PC12 cell toxic susceptibility through the Shh pathway. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:16513. doi: 10.1038/srep16513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]