Abstract

The proteasome holoenzyme is a molecular machine that degrades most proteins in eukaryotes. In the holoenzyme, its heterohexameric ATPase injects protein substrates into the proteolytic core particle, where degradation occurs. The heterohexameric ATPase, referred to as 'Rpt ring', assembles through six ATPase subunits (Rpt1–Rpt6) individually binding to specific chaperones (Rpn14, Nas6, Nas2, and Hsm3). Here, our findings suggest that the onset of Rpt ring assembly can be regulated by two alternative mechanisms. Excess Rpt subunits relative to their chaperones are sequestered into multiple puncta specifically during early-stage Rpt ring assembly. Sequestration occurs during stressed conditions, for example heat, which transcriptionally induce Rpt subunits. When the free Rpt pool is limited experimentally, Rpt subunits are competent for proteasome assembly even without their cognate chaperones. These data suggest that sequestration may regulate amounts of individual Rpt subunits relative to their chaperones, allowing for proper onset of Rpt ring assembly. Indeed, Rpt subunits in the puncta can later resume their assembly into the proteasome. Intriguingly, when proteasome assembly resumes in stressed cells or is ongoing in unstressed cells, excess Rpt subunits are recognized by an alternative mechanism—degradation by the proteasome holoenzyme itself. Rpt subunits undergo proteasome assembly until the holoenzyme complex is generated at a sufficient level. The fully-formed holoenzyme can then degrade any remaining excess Rpt subunits, thereby regulating its own Rpt ring assembly. These two alternative mechanisms, degradation and sequestration of Rpt subunits, may help control the onset of chaperone-mediated Rpt ring assembly, thereby promoting proper proteasome holoenzyme formation.

Keywords: ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities (AAA), chaperone, proteasome, protein assembly, protein complex

Introduction

The proteasome holoenzyme is an essential protease in eukaryotes, consisting of the 19-subunit regulatory particle (RP)2 and the 28-subunit proteolytic core particle (CP) (1–3). One or two RP associate with the axial ends of the CP, generating singly-capped or doubly-capped proteasome holoenzymes (RP1-CP and RP2-CP). In the proteasome holoenzyme, the RP recognizes polyubiquitinated protein substrates and translocates them into the CP, where their degradation occurs (4). The cylindrical CP is a stack of four heteroheptameric rings, which consist of seven different α and β subunits in the arrangement of α1–7β1–7β1–7α1–7 (5). The inner β rings contain peptidase subunits (β1, β2, and β5). The outer α rings serve as the binding surface for the RP (6, 7). The RP can be further divided into two subcomplexes: base and lid each consisting of nine integral subunits (8). In the base, six distinct ATPase subunits (Rpt1–6) form a heterohexameric Rpt ring, which directly associates with the α ring of the CP (1–3, 9, 10). Also, the heterohexameric Rpt ring provides the binding site for the lid (1–3). Thus, the Rpt ring of the base mediates formation of base–lid and base–CP interfaces, which are required for both assembly and function of the proteasome holoenzyme (lid–base–CP) (1–3).

During early-stage proteasome holoenzyme formation, the heterohexameric Rpt ring assembles via multiple chaperones: Rpn14, Nas6, Nas2, and Hsm3 (referred to as chaperones henceforth) (11–15). These chaperones are evolutionarily conserved between yeast and humans (16, 17). Each chaperone binds to its cognate Rpt protein in a pairwise manner: Rpn14–Rpt6, Nas6–Rpt3, Nas2–Rpt5, and Hsm3–Rpt1. Three distinct “chaperone–Rpt–Rpt modules” form: Rpn14–Rpt6–Rpt3–Nas6; Nas2–Rpt5–Rpt4; and Hsm3–Rpt1–Rpt2. These modules then join to complete the heterohexameric Rpt ring of the base. Both structural and biochemical studies show that the chaperones sterically obstruct the base's interaction with the CP and lid (18–21). Through this mechanism, the chaperones can block any premature or inappropriate associations between the base and the other subcomplexes, the lid and CP. Upon completion of the proteasome holoenzyme, the chaperones release (12, 13, 19, 22).

Although it is well agreed that late-stage proteasome assembly relies on chaperones' cooperative actions on the base, it has not been examined how early-stage chaperone–Rpt subunit association might be ensured prior to heterohexameric Rpt ring formation. Quantitative proteomics data suggest that early-stage Rpt–Rpt modules are always in complex with their cognate chaperones, whereas the heterohexameric Rpt ring can be in complex with only a subset of chaperones, instead of all four (14). Also, in conditions when increased proteasome assembly is required for protein degradation, yeast cells induce an additional chaperone, Adc17, which acts transiently during early-stage Rpt ring assembly, suggesting that these early steps are crucial for enhancing the entire proteasome assembly (23). Based on biochemical studies, deletion of chaperones results in an overall reduction of heterohexameric Rpt ring assembly, rather than an increase in aberrant assembly intermediates (11, 12, 14, 23); the cellular abundance of individual Rpt subunits remains largely unchanged. These observations suggest the possibility that individual chaperone–Rpt subunit association may promote proper onset of heterohexameric Rpt ring assembly. Furthermore, distinct chaperone–Rpt–Rpt modules form at different rates and levels (14, 23). These data prompted us to examine whether and how the onset of heterohexameric Rpt ring assembly might be regulated for proper proteasome holoenzyme formation.

Our findings suggest that early-stage Rpt ring assembly can be regulated by two alternative mechanisms: 1) degradation, and 2) sequestration of excess Rpt subunits relative to the chaperones. Under conditions when increased proteasome assembly is required, transient sequestration of Rpt subunits appears to control the amounts of Rpt subunits relative to the chaperones. Alternatively, under normal conditions, the fully-formed proteasome holoenzyme itself degrades excess Rpt subunits, thereby regulating its own assembly via the chaperones. Our data indicate that these two mechanisms may help control the onset of chaperone-mediated Rpt ring assembly to promote proper proteasome holoenzyme formation.

Results

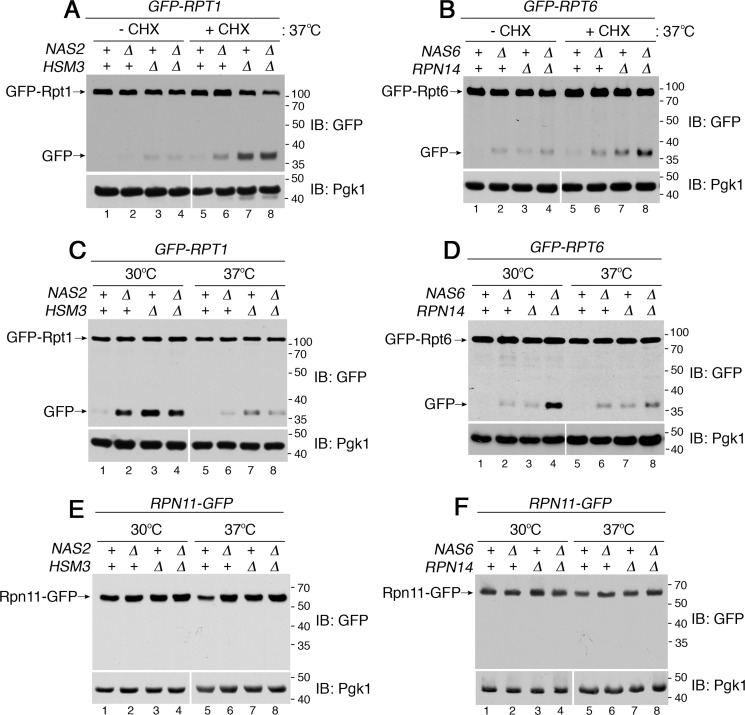

Chaperones are crucial during early-stage Rpt ring assembly in stressed conditions

To examine regulations during chaperone-mediated assembly of the heterohexameric Rpt ring, we generated two panels of chaperone deletion mutants in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: 1) nas2Δ, hsm3Δ, and nas2Δhsm3Δ, and 2) nas6Δ, rpn14Δ, and nas6Δrpn14Δ. Two chaperones, Nas6 and Rpn14, are in complex with the same Rpt3–Rpt6 module (11, 14, 16). The other two chaperones, Nas2 and Hsm3, exist in the Rpt5–Rpt4 module and Rpt1–Rpt2 module, respectively. Using these two panels of chaperone mutants, we can disrupt individual modules in their progression into hexameric Rpt ring assembly. Chaperone-mediated Rpt ring assembly has been suggested to increase in stressed conditions, including heat stress, in which enhanced proteasome assembly is needed for protein degradation (23). Therefore, we first cultured these chaperone deletion mutants at the normal growth temperature, 30 °C, and then exposed them to heat stress at 37 °C. We then examined both proteasome assembly and activity by subjecting whole-cell extracts to native PAGE and in-gel peptidase assays.

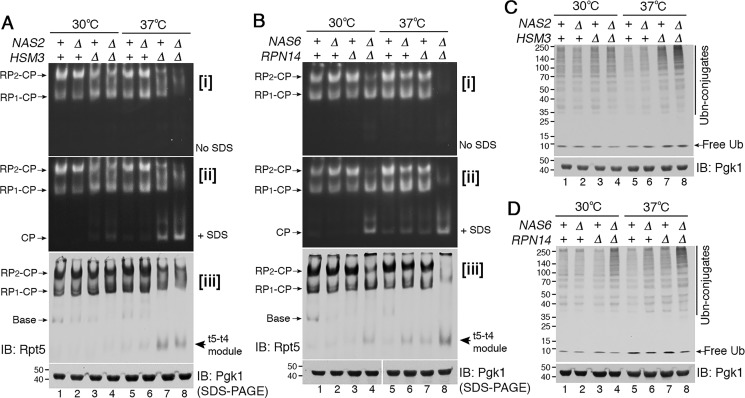

In WT cells, doubly-capped proteasome holoenzymes (RP2–CP) are predominant because RPs are generated at sufficient levels, allowing two RPs to associate with a CP at both axial ends (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 and 5). In both hsm3Δ and nas2Δhsm3Δ cells at 30 °C, RP2–CP is decreased, and RP1–CP is comparatively increased, indicating deficient RP assembly in the chaperone mutants (Fig. 1A, panel i, lanes 3 and 4) (23, 24). Strikingly, when the nas2Δhsm3Δ double mutants are exposed to heat stress at 37 °C, they fail to generate discrete RP2–CP or RP1–CP complexes and instead exhibit aberrant complexes with a significant decrease in proteolytic activity (Fig. 1A, lane 8). Reduced holoenzyme formation at 37 °C was accompanied with free CP accumulation (Fig. 1A, panel ii, lanes 7 and 8). These results reflect that RP assembly defects are exacerbated upon heat stress, leading to a severe decrease in free RP and accumulation of the free CP. This trend was also observed in the nas6Δrpn14Δ double mutants, exhibiting little detectable proteasome holoenzymes together with free CP accumulation upon heat stress (Fig. 1B, lane 8). Overall, upon heat stress, proteasome holoenzyme assembly is severely disrupted when only two chaperones are deleted, although the other two chaperones remain intact. Our data suggest that individual chaperones become crucial for RP assembly that is required to generate proteasome holoenzymes in stressed conditions.

Figure 1.

Proteasome holoenzyme formation requires chaperone-mediated Rpt ring assembly during heat stress. A and B, upon heat stress, early-stage Rpt ring assembly requires the chaperones. Yeast strains were grown at 30 °C (lanes 1–4), and then exposed to heat stress at 37 °C for 4 h (lanes 5–8). Proteasome activities were assessed by subjecting whole-cell lysates (60 μg) to native PAGE and in-gel peptidase assays using the fluorogenic peptide substrate, LLVY-AMC (panel i). After imaging the native gels in panel i, 0.02% SDS was added to activate free CP in panel ii; SDS denatures the substrate entry gate of the CP (25). Native gels were then subjected to immunoblotting (IB) to detect levels of the Rpt5–Rpt4 modules (t5–t4 module) and proteasome holoenzymes (panel iii). Pgk1 is a loading control. B, Pgk1 blot in lanes 1–4 and 5–8 derives from two different gels, which were processed the same in parallel during immunoblotting and signal detection. C and D, ubiquitinated protein degradation requires chaperone-mediated proteasome assembly during heat stress. Whole-cell lysates (20 μg) from samples as in A and B were subjected to 10% BisTris SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for ubiquitin. Pgk1 is a loading control.

To assess heterohexameric Rpt ring assembly of the RP during heat stress, we examined a representative assembly intermediate, the Rpt5–Rpt4 module. This module is not readily detectable when it can efficiently assemble into the proteasome holoenzyme (Fig. 1, A and B, panel iii, lanes 1 and 5) (11, 14). Upon heat stress at 37 °C, this module accumulates in the hsm3Δ and hsm3Δnas2Δ mutants (Fig. 1A, panel iii, lanes 7 and 8). Also, the nas6Δrpn14Δ double mutants noticeably accumulate the Rpt5–Rpt4 module at 37 °C, relative to 30 °C (Fig. 1B, panel iii, compare lane 8 to 4). These results suggest that, although this Rpt5–Rpt4 module can form, it cannot proceed to higher-order complexes in the chaperone deletion mutants (11). This interpretation is supported by apparent lack of late-stage assembly intermediates, such as base or RP species in the nas2Δhsm3Δ and nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants at 37 °C (Fig. 1, A and B, panel iii, lane 8). These data suggest that upon heat stress, chaperones become crucial during early-stage Rpt ring assembly, where individual chaperone–Rpt–Rpt modules associate to form the heterohexameric Rpt ring.

We tested whether defects in early-stage Rpt ring assembly in the chaperone mutants are reflected in proteasome function in cellular protein degradation. Both nas2Δhsm3Δ and nas6Δrpn14Δ double mutants accumulate more ubiquitinated proteins at 37 °C than at 30 °C (Fig. 1, C and D, compare lane 8 to 4). These results indicate further impairment of cellular protein degradation, resulting from exacerbated defects at early-stage Rpt ring assembly. Although free CP accumulates in both nas2Δhsm3Δ and nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants (Fig. 1, A and B, panel ii, lane 8), the CP alone cannot degrade ubiquitinated protein substrates without the RP (25).

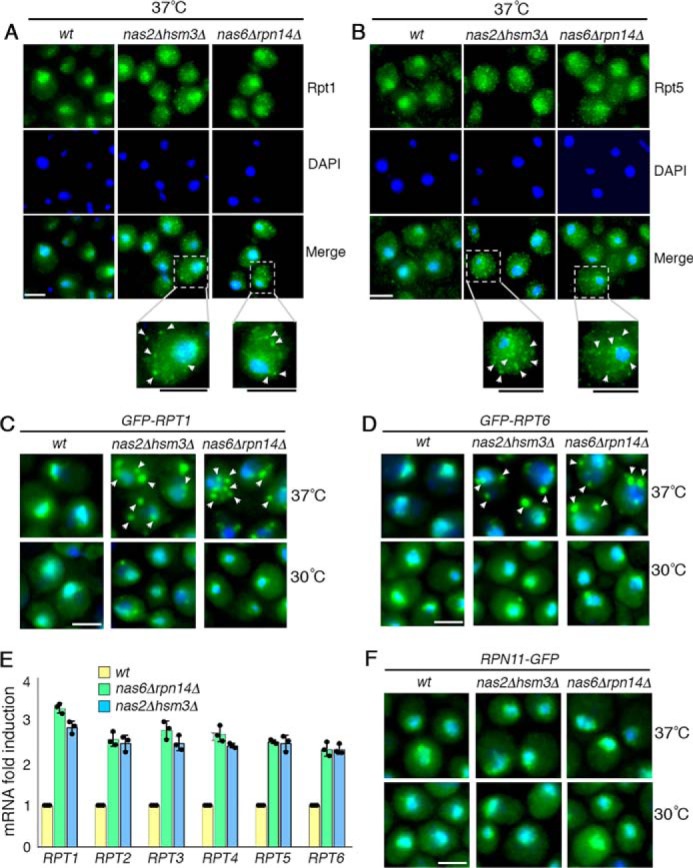

During early-stage Rpt ring assembly, excess Rpt subunits are sequestered into puncta

Heterohexameric Rpt ring assembly has been suggested to initiate in the cytoplasm, where its assembly chaperones are also detected (14, 26–29). To examine potential regulations in this process, we visualized cellular localization of Rpt subunits in the chaperone deletion mutants using immunofluorescence. In WT cells, Rpt1 was detected mainly in the nucleus with a dim diffuse cytoplasmic signal, consistent with previous findings (Fig. 2A) (26, 30). However, the nas2Δhsm3Δ double mutants exhibited Rpt1 in multiple small puncta in the cytoplasm at 37 °C, in addition to nuclear Rpt1 signal (Fig. 2A, see enlarged image). Similarly, the nas6Δrpn14Δ double mutants also exhibited Rpt1 in multiple small puncta (Fig. 2A, see enlarged image). To test whether other Rpt subunits also exhibit puncta formation, we examined an additional Rpt subunit, Rpt5. In both nas2Δhsm3Δ and nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants, Rpt5 also forms multiple small puncta, like Rpt1 (Fig. 2B). Punctate signals of both Rpt1 and Rpt5 are detected mainly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2, A and B) and not the nucleus, where proteasome holoenzyme assembly is normally completed (26–29). Cytoplasmic Rpt subunit puncta correlate with exacerbated defects in proteasome assembly in both nas2Δhsm3Δ and nas6Δrpn14Δ cells upon heat stress (Fig. 1). These results suggest that these puncta may sequester multiple Rpt subunits upon chaperone deficiency during heterohexameric Rpt ring assembly.

Figure 2.

During early-stage Rpt ring assembly, excess Rpt subunits are sequestered into puncta. A–D, excess Rpt subunits are sequestered into puncta during early-stage Rpt ring assembly. Indicated yeast strains were exposed to heat stress at 37 °C for 4 h (A and B). Yeast cells were imaged using epi-fluorescence microscopy to visualize Rpt1 and Rpt5, using antibodies specific to these subunits (A and B). Scale bar, 5 μm for all panels. For insets, scale bars are shown as black lines directly below the panels. C and D, GFP-tagged Rpt1 and Rpt6 are expressed from their endogenous chromosomal loci and were visualized at 30 °C (bottom panels) and then after 15 min of heat stress at 37 °C (top panels). DAPI staining indicates nuclei. Arrowheads indicate cytoplasmic punctate structures of Rpt subunits. Scale bar, 5 μm for all panels. E, increased mRNA levels of all six Rpt subunits in the chaperone deletion mutants. Quantitative real-time PCR results for RPT subunits were normalized to ACT1. Fold induction of RPT subunit mRNA in the indicated chaperone deletion mutants was calculated relative to WT (average ± S.D.; n = 3, biological replicates); individual data points are indicated as dots. F, lid subunit, Rpn11, does not form puncta and exhibits normal nuclear localization. Experiments were conducted as in C and D. Scale bar, 5 μm for all panels.

To test whether these Rpt subunit puncta can be localized using a yEGFP tag (referred to as GFP for simplicity), we used two yeast strains, in which GFP–Rpt1 and GFP–Rpt6 are integrated in their endogenous chromosomal locus. Both strains have been characterized to show that N-terminal GFP tagging does not interfere with proteasome assembly or activity (14). We also confirmed that expression levels of GFP–Rpt1 and GFP–Rpt6 are indistinguishable from untagged Rpt subunits (Fig. S1) and that they incorporate into the proteasome holoenzyme like untagged Rpt subunits in Fig. 1 (Fig. S2). As early as 15 min following heat stress, GFP–Rpt1 in both nas2Δhsm3Δ and nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants formed multiple cytoplasmic puncta (Fig. 2C, top panels; see also Fig. S3). This is also the case for GFP–Rpt6 in both double-chaperone deletion mutants (Fig. 2D, top panels). Upon heat stress, WT cells exhibit Rpt subunit-puncta in a transient manner (Fig. S4), suggesting that sequestration of Rpt subunits may occur during Rpt ring assembly in stress conditions.

Upon the slightest decrease in proteasome holoenzyme activities, cells transcriptionally induce proteasome subunits to compensate for reduced proteasome function (31, 32). Because deletion of chaperones disrupts proteasome holoenzyme formation upon heat stress (Fig. 1, A and B), we examined whether this condition also leads to induction of Rpt subunits. Indeed, mRNA levels of all six Rpt subunits are increased by 2-fold or more in both nas6Δrpn14Δ and nas2Δhsm3Δ cells (Fig. 2E). Because all six Rpt subunits are induced together, this would exacerbate the burden to the remaining chaperones in both nas6Δrpn14Δ and nas2Δhsm3Δ cells. These results suggest that Rpt subunit puncta formation might normally serve to sequester excess Rpt subunits, relative to the chaperones, during early-stage heterohexameric Rpt ring assembly.

Next, we tested whether Rpt subunit puncta form in response to other proteasome stressors, such as canavanine, an arginine analog. Similar to heat stress, canavanine induces protein misfolding, increasing flux of protein substrates into the proteasome for degradation. When canavanine was added to yeast culture, Rpt subunit puncta were readily detected in the nas6Δrpn14Δ double mutants but minimally in the nas2Δhsm3Δ double mutants (Fig. S5). This difference is consistent with their phenotypes because the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants are hypersensitive to canavanine, but the nas2Δhsm3Δ mutants are not (11, 14). Both mutants are highly sensitive to heat, which correlates with their noticeable Rpt subunit puncta formation (Fig. 2, A–D) (11, 14). These results suggest that, under multiple stressed conditions, proteasome assembly depends on successful early-stage Rpt ring assembly by the chaperones.

Lid subunit, Rpn11, does not belong to Rpt subunit puncta

If Rpt subunit puncta form specifically during early-stage Rpt ring assembly of the base, they should not contain any subunits of the lid because lid–base association occurs during late-stage assembly of the proteasome. We examined representative lid subunit Rpn11. Unlike Rpt subunits, Rpn11–GFP did not exhibit cytoplasmic puncta regardless of growth temperature, and it localized normally to the nucleus in both nas2Δhsm3Δ and nas6Δrpn14Δ double chaperone deletion mutants (Fig. 2F). These data are consistent with the findings that the lid assembles independently of the base and imports into the nucleus for proteasome holoenzyme formation (26, 33, 34). Our data support that Rpt subunit puncta specifically sequester excess Rpt subunits during early-stage Rpt ring assembly.

Rpt subunits can be competent for proteasome assembly even without the chaperones

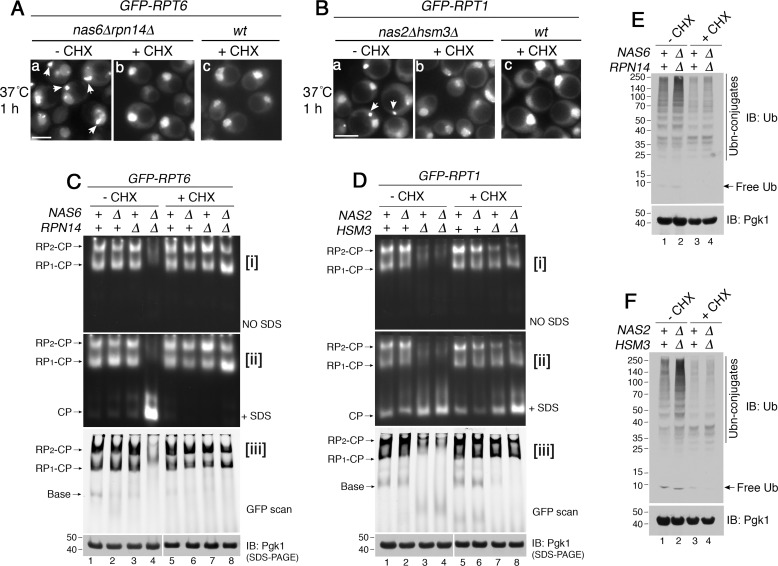

Based on our data, sequestration of Rpt subunits occurs upon heat stress, which transcriptionally induces all six Rpt subunits (Fig. 2E) but not the chaperones (31, 35, 36). These data prompted us to test whether, without chaperones, the Rpt subunits are competent for proteasome assembly if they are not sequestered. The translation inhibitor cycloheximide has been used to block sequestration of other proteins, whose levels are increased due to stress-induced synthesis (37, 38). Indeed, when cycloheximide was added during heat stress, GFP–Rpt6 no longer formed puncta in the nas6Δrpn14Δ double mutant (Fig. 3A, compare panels a to b) and exhibited a normal nuclear localization, like WT (Fig. 3A, panel c). This was also the case for GFP–Rpt1 in the hsm3Δ mutant and nas2Δhsm3Δ double mutant (Fig. 3B, compare panels a to b; see Fig. S6). We then tested whether or not these Rpt subunits can be competent for proteasome assembly without chaperones.

Figure 3.

Rpt subunits can be competent for proteasome assembly without their cognate chaperones. A and B, Rpt subunits are no longer sequestered into puncta upon translation inhibition during heat stress. Live-cell images using epi-fluorescence microscopy are shown. Cycloheximide (CHX, 150 μg/ml) was added at the time of temperature shift to 37 °C and incubated for 1 h. Scale bar, 5 μm for all panels. C and D, Rpt subunits assemble into the proteasome holoenzyme without their cognate chaperones upon translation inhibition. Indicated yeast strains were grown at 37 °C for 4 h in the absence or presence of cycloheximide (150 μg/ml). Proteasome assembly and activities were assessed by subjecting whole-cell lysates (60 μg) to native PAGE and in-gel peptidase assays without or with 0.02% SDS in panels i and ii, respectively. Proteasome holoenzyme levels were examined by scanning the native gels for GFP–Rpt6 (C, panel iii) and GFP–Rpt1 (D, panel iii). See Fig. S7, which shows that untagged Rpt subunits also exhibit the same restoration of proteasome assembly. Pgk1 is a loading control. Pgk1 blots in lanes 1–4 and 5–8 derive from two different gels, which were processed the same in parallel during immunoblotting (IB) and signal detection. E and F, ubiquitinated proteins are degraded upon restoration of proteasome assembly in the chaperone mutants. Whole-cell lysates (20 μg) were obtained from yeast cells that were treated as in C and D. These yeast cells harbor untagged Rpt subunits as in Fig. S7. The lysates were subjected to 10% BisTris SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with an antibody to ubiquitin. Pgk1 is a loading control.

Strikingly, our native gels showed substantial restoration of both proteasome assembly and activity in the nas6Δrpn14Δ double mutants upon translation inhibition (Fig. 3C, lane 4 versus 8). Both RP2–CP and RP1–CP species were readily detected in the nas6Δrpn14Δ double mutant upon cycloheximide treatment at 37 °C, relative to its untreated counterpart (Fig. 3C, panel i, compare lane 8 to 4). Concurrently, in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutant, the free CP incorporated into holoenzymes (RP2–CP and RP1–CP), indicating that sufficient RPs are generated to associate with the CP (Fig. 3C, panel ii, lane 4 versus 8). Also, we confirmed that levels of the proteasome holoenzymes (RP2–CP and RP1–CP) are indeed restored in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants upon cycloheximide treatment (Fig. 3C, panel iii, lane 8). Restoration of RP assembly would not lead to excessive formation of the holoenzyme because the level of the CP is limiting. The hsm3Δ and nas2Δhsm3Δ mutants also exhibited some restoration of both proteasome assembly and activity during heat stress, specifically upon translation inhibition (Fig. 3D, lanes 7 and 8). We confirmed that the GFP tag has no effect on these results (Fig. S7). Cycloheximide did not decrease the proteasome level in WT cells (Fig. 3, C and D, lanes 1 and 5), because the half-life of the proteasome is substantially longer than the duration of our experiments (39). Taken together, these results suggest that Rpt subunits can be competent for proteasome assembly, even without chaperones.

When assembly of the proteasome holoenzyme was restored (Fig. 3, C and D, lane 8), polyubiquitinated proteins no longer accumulated in both nas6Δrpn14Δ and nas2Δhsm3Δ mutants (Fig. 3, E and F, lane 4). Although translation inhibition would decrease generation of polyubiquitinated proteins to some extent, these proteins still accumulate if cellular proteasome activity is reduced (40). These results support that restored proteasome assembly contributes to an improvement in proteasome-mediated protein degradation in the cell.

Limiting the pool of excess Rpt subunits promotes early-stage Rpt ring assembly

How might translation inhibition restore proteasome assembly? Translation inhibition appears to prevent sequestration of Rpt subunits (Fig. 3, A and B), but it is known to result in other effects (40, 41). One such effect is ubiquitin depletion (40). Because of a relatively short half-life of ubiquitin (∼2 h in yeast), the free ubiquitin level is decreased when its synthesis stops (40). If cellular ubiquitin level influences proteasome assembly, increasing ubiquitin expression should have some effects on proteasome assembly. However, ubiquitin induction did not result in any noticeable effects on the overall levels of proteasome holoenzymes in WT, nas6Δrpn14Δ, and nas2Δhsm3Δ cells (Fig. S8). These results suggest that the cellular ubiquitin level is unlikely to have a major effect on proteasome assembly. In addition, proteasome partial loss-of-function mutants are cycloheximide-resistant (40, 41) because they stabilize ubiquitin, and ubiquitin may then be used for other ubiquitin-dependent processes. However, this phenotype is noticeable after days of cycloheximide treatment (40, 41), whereas proteasome assembly is restored within several hours after the treatment (Fig. 3, C and D). Based on this timeline, restoration of proteasome assembly is unlikely to result from cycloheximide resistance.

Rather, proteasome assembly may improve because translation inhibition can affect the pool of free Rpt subunits as follows. First, translation inhibition would limit the pool of free Rpt subunits because further synthesis of new Rpt subunits would be blocked. This effect may help the existing Rpts avoid a “bottleneck” at the onset of Rpt ring assembly for progression into higher-order complexes even without chaperones. Second, because general nascent peptides are also decreased in their synthesis, the existing Rpts would have less nonspecific interactions during early-stage Rpt ring assembly. As a result, Rpt subunits may be able to proceed to the proteasome, even without chaperones, rather than forming puncta.

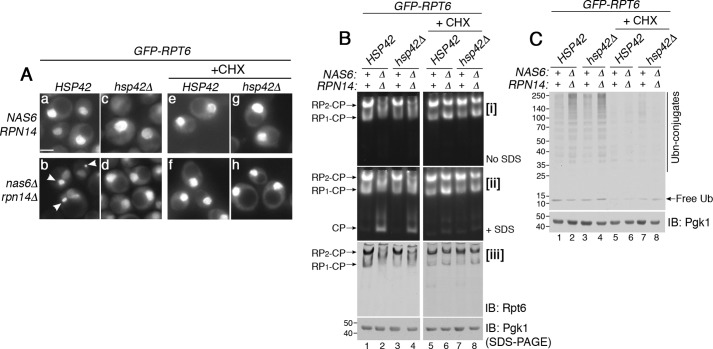

Next, we examined whether Rpt subunits can proceed to proteasome assembly when the free Rpt pool remains high, and their sequestration is blocked. Hsp42, a small heat-shock chaperone, promotes protein sequestration (42). Deletion of HSP42 is known to block protein sequestration under various conditions (43, 44). Indeed, upon deletion of HSP42, GFP–Rpt6 did not exhibit puncta during heat stress in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants (Fig. 4A, compare panels b to d). This is also the case for GFP–Rpt1 in the nas2Δhsm3Δ mutants (Fig. S9A, compare panel b to d). The hsp42Δ single mutant was indistinguishable from WT (Fig. 4A, see panels a and c). We then examined whether these Rpt subunits can assemble into the proteasome holoenzyme. However, proteasome assembly remained equally deficient whether or not Hsp42 is expressed in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 and 4). This is also the case for the nas2Δhsm3Δ mutants (Fig. S9B, lanes 2 and 4). In both nas6Δrpn14Δ and nas2Δhsm3Δ mutants, deletion of HSP42 did not result in any additional assembly intermediates (Fig. 4B, panel iii, lanes 2 and 4; also see Fig. S9B, panel iii, lanes 2 and 4). Because sequestration recognizes excess Rpt subunits, preventing sequestration would increase the pool of Rpt subunits in the cell. However, our data suggest that proteasome assembly cannot be restored simply because a large pool of free Rpt subunits exists.

Figure 4.

Rpt subunits proceed to proteasome assembly when the free Rpt pool is limited. A, sequestration of Rpt subunits can be blocked upon deletion of HSP42. Live-cell images using epi-fluorescence microscopy were obtained upon heat stress at 37 °C for 1 h (panels a–d). The same experiments were also conducted in the presence of cycloheximide (panels e–h, CHX, 150 μg/ml). Arrowheads in panel b indicate GFP–Rpt6 puncta. Scale bar, 5 μm for all panels. B, Rpt subunits incorporate into the proteasome holoenzyme, not simply when their sequestration is blocked but when their continued synthesis is blocked (see text for details). Indicated yeast strains were grown in the absence or presence of cycloheximide (150 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 2 h. Proteasome assembly and activities were assessed by subjecting whole-cell lysates (60 μg) to native PAGE and in-gel peptidase assays without or with 0.02% SDS in panels i and ii, respectively. Proteasome holoenzyme levels were examined by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-Rpt6 antibody (panel iii). Pgk1 is a loading control. The Pgk1 blot in lanes 1–4 and 5–8 derives from two different gels, which were processed the same in parallel during immunoblotting and signal detection. C, cellular ubiquitinated proteins are degraded upon efficient assembly of the proteasome holoenzyme. Whole-cell lysates (20 μg) were obtained from yeast cells that were treated as in B. The lysates were subjected to 10% BisTris SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with an antibody to ubiquitin. Pgk1 is a loading control.

Importantly, upon addition of cycloheximide, proteasome assembly was substantially restored whether or not Hsp42 is expressed in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants (Fig. 4B, lanes 6 and 8). This trend was also observed in the nas2Δhsm3Δ mutants (Fig. S9B, lanes 6 and 8). These data support that controlling the pool of free Rpt subunits, not simply increasing it, keeps these subunits competent for proper onset of Rpt ring assembly. This Rpt pool is normally in complex with their cognate chaperones (13–17), and any remainder of this pool may be regulated via sequestration.

When proteasome assembly is deficient (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 and 4), ubiquitin conjugates accumulate in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants whether or not Hsp42 is present (Fig. 4C, lanes 2 and 4). This confirms that Hsp42 does not affect proteasome assembly or activity. Upon translation inhibition when proteasome assembly is restored in both nas6Δrpn14Δ and nas6Δrpn14Δhsp42Δ mutants (Fig. 4B, lanes 6 and 8), ubiquitin conjugates were nearly undetectable, suggesting that cellular protein degradation is also improved (Fig. 4C, lanes 6 and 8). In the nas2Δhsm3Δ mutants, regardless of Hsp42, cellular protein degradation also depends on the extent of proteasome assembly (Fig. S9C).

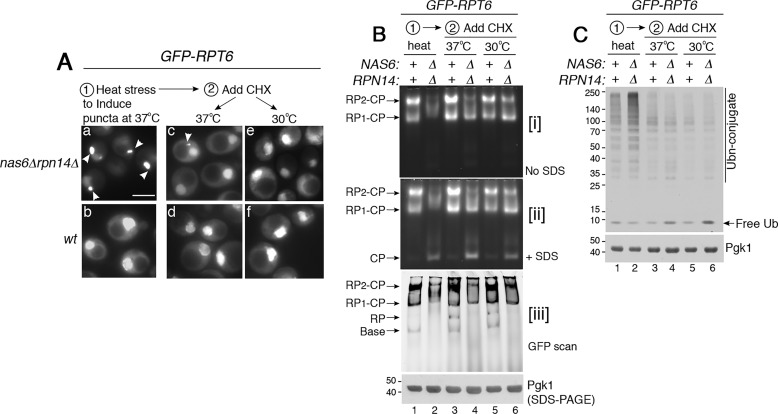

Rpt subunit puncta can serve as a reservoir for future proteasome assembly

We next examined whether Rpt subunits in the puncta can be used for proteasome assembly later. For this, we followed GFP–Rpt6 because Rpt6 is crucial for initiating heterohexameric Rpt ring assembly (12, 20, 45). Nas6 and Rpn14 are in complex with the Rpt3–Rpt6 module and promote its assembly into the proteasome. We first induced GFP–Rpt6 puncta formation in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants by applying heat stress at 37 °C for 2 h (Fig. 5A, panel a). We then added cycloheximide and continued incubation at 37 °C or shifted to 30 °C. In this way, we can block synthesis of new Rpt subunits and follow the fate of the existing Rpt subunits. After cycloheximide addition, GFP–Rpt6 puncta diminished by 4 h at 37 °C, and were nearly undetectable at a normal growth temperature, 30 °C (Fig. 5A, see panels c and e). These results suggest that sequestration of Rpt subunits into puncta can be reversed when the pool of free Rpt subunits is reduced.

Figure 5.

Rpt subunits in the puncta can resume their assembly into the proteasome. A, GFP–Rpt6 in the puncta can reverse to its normal nuclear localization. Live-cell images using epi-fluorescence microscopy are shown. GFP–Rpt6 puncta formation (panel a, arrowheads) was induced at 37 °C for 2 h first (panels a and b). Next, cycloheximide (CHX, 150 μg/ml) was added to track the fate of the existing Rpt6 for 4 h at 37 °C (panels c and d) or 30 °C (panel e and f). Scale bar, 5 μm for all panels. B, GFP–Rpt6, which was sequestered into the puncta, can resume assembly into the proteasome holoenzyme. New protein synthesis was blocked using cycloheximide, as indicated in A. Proteasome assembly and activity were examined by subjecting whole-cell lysates (50 μg) to 3.5% native PAGE and in-gel peptidase assays without or with 0.02% SDS in panels i and ii, respectively. Levels of the proteasome holoenzyme, RP, and base were examined by scanning for GFP–Rpt6 in panel iii. Pgk1 is a loading control. C, ubiquitinated proteins initially accumulate due to deficient proteasome assembly and are degraded upon resumption of proteasome assembly. Whole-cell lysates (20 μg) from yeast cells as in B were subjected to 10% BisTris SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with an antibody to ubiquitin. Pgk1 is a loading control.

When Rpt subunits are sequestered into the puncta (Fig. 5A, panel a), proteasome assembly is deficient in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants relative to WT cells, as expected (Fig. 5B, lane 2 versus 1). We then examined whether GFP–Rpt6 subunits in the puncta can incorporate into the proteasome holoenzyme upon addition of cycloheximide. Based on our native gels, Rpt6, which was sequestered in puncta, now can assemble into the proteasome holoenzyme in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants. Both holoenzymes species (RP2–CP and RP1–CP) became detectable in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants at 37 °C to some extent and more noticeably at 30 °C (Fig. 5B, lane 4 and 6). Also, WT cells exhibit an increase in RP assembly because free RP is detectable, specifically upon cycloheximide addition (Fig. 5B, panel iii, see RP in lanes 3 and 5). This result supports our interpretation that WT cells may transiently sequester excess Rpt subunits during times of stress (Fig. S4) for future rounds of proteasome assembly. Taken together, these data provide some evidence that Rpt subunits in the puncta can be used for later rounds of proteasome assembly.

When proteasome assembly is deficient in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutant during initial heat stress, polyubiquitin conjugates accumulate (Fig. 5C, lane 2). When proteasome assembly is restored, polyubiquitin conjugates are degraded (Fig. 5C, lanes 4 and 6). In these nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants, free ubiquitin is slightly increased (Fig. 5C, lanes 4 and 6). This effect is because free ubiquitin is normally regenerated from the polyubiquitin during degradation of the conjugated protein by the proteasome (40, 46). Such ubiquitin recycling is readily detectable in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants because they exhibit more polyubiquitin conjugates than WT (Fig. 5C, compare lane 2 to 1). These results suggest that restored proteasome assembly correlates with restored proteasome function in protein degradation.

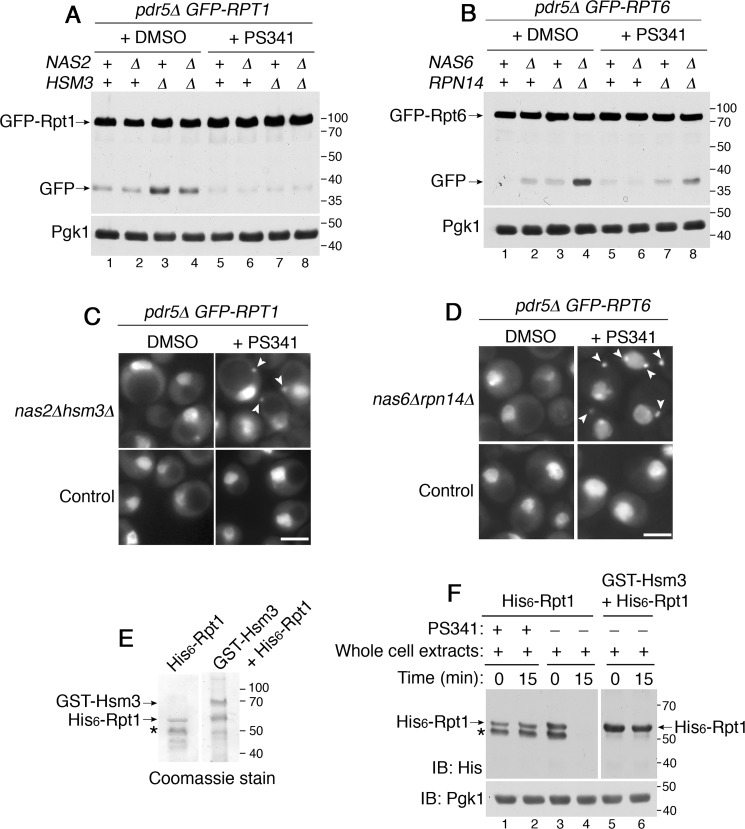

During ongoing proteasome assembly, excess Rpt subunits are regulated by degradation

We sought to examine whether cells can recognize any excess Rpt subunits when proteasome assembly resumes, as in cycloheximide-treated conditions (Fig. 3). For this, we examined the cellular abundance of Rpt subunits in the chaperone mutants following cycloheximide treatment during heat stress. We noticed that the full-length GFP–Rpt1 level was slightly decreased in the nas2Δhsm3Δ double mutants, relative to WT (Fig. 6A, compare lane 8 to 5). Because new protein synthesis is inhibited by cycloheximide, the reduced GFP–Rpt1 level indicates its increased degradation. A decrease in full-length GFP–Rpt1 was accompanied by free GFP liberation in the nas2Δhsm3Δ double mutant (Fig. 6A, lane 8). Free GFP liberation was also observed in the nas2Δ and hsm3Δ single mutants to some extent (Fig. 6A, lanes 6 and 7). When the GFP-fused protein undergoes degradation, the GFP moiety can evade degradation due to its extremely tight folding, and it releases as free GFP while the fused Rpt subunit undergoes degradation (44, 47, 48). The nas6Δrpn14Δ double mutants also exhibited some free GFP liberation, indicating that the fused Rpt6 is also degraded to some extent (Fig. 6B, lane 8). Any partial Rpt1 or Rpt6 fragments were not detectable, suggesting that these subunits are degraded processively (Fig. S10). Therefore, when proteasome assembly resumes during heat stress (Fig. 3, C and D, lanes 6–8), any remaining excess Rpt subunits appear to be degraded.

Figure 6.

During ongoing proteasome assembly, any remaining excess Rpt subunits are degraded. A and B, excess Rpt subunits undergo degradation at 37 °C when proteasome assembly is restored upon cycloheximide treatment. Please see Fig. 3, C and D, for restoration of proteasome assembly (lanes 6–8). Cells were exposed to heat stress at 37 °C for 4 h in the absence or presence of cycloheximide (CHX, 150 μg/ml). Whole-cell extracts were subjected to 10% BisTris SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. GFP release reflects degradation of the fused Rpt subunits (see text for details). Pgk1 is a loading control. Pgk1 blots in lanes 1–4 and 5–8 derive from two different gels, which were processed the same in parallel during immunoblotting and signal detection. C and D, excess Rpt subunits undergo degradation at a normal growth temperature, 30 °C, at which proteasome assembly is comparatively more active than at 37 °C. Please see Fig. 1, A and B, for proteasome assembly at 30 °C versus 37 °C. Yeast cells were first grown at 30 °C and then at 37 °C for 4 h. Samples were analyzed as in A and B. Pgk1 is a loading control. Pgk1 blots in lanes 1–4 and 5–8 derive from two different gels, which were processed the same in parallel during immunoblotting and signal detection. E and F, Rpn11, a subunit of the lid, remains stable in the chaperone mutants. Experiments were conducted as in C and D. Increased Rpn11–GFP level in the chaperone mutants can be attributed to Rpn4-driven transcription induction (see text). Rpn11–GFP level might slightly differ in WT cells at 30 °C versus 37 °C (lane 1 versus 5) due to complex regulation of Rpn4 itself (35, 61). Pgk1 is a loading control. Pgk1 blots in lanes 1–4 and 5–8 derive from two different gels, which were processed the same in parallel during immunoblotting and signal detection.

We tested whether excess Rpt subunits are also degraded during normal growth at 30 °C, when they mainly proceed to proteasome assembly, and puncta formation is scarce (Figs. 1, A and B, lanes 2–4, and 2, C and D, bottom). Indeed, free GFP is liberated from GFP–Rpt1 in nas2Δ, hsm3Δ, and nas2Δhsm3Δ mutants at 30 °C (Fig. 6C, lanes 2–4), suggesting that excess Rpt1 is degraded. Like Rpt1, Rpt6 is also degraded to some extent in the nas6Δrpn14Δ double deletion mutants and weakly in both of the single deletion mutants at 30 °C (Fig. 6D, lanes 2–4). During heat stress at 37 °C, excess Rpt1 and Rpt6 are less degraded, as indicated by a low-level GFP liberation (Fig. 6, C and D, compare lane 8 to 4); these subunits instead form puncta (Fig. 2, C and D, top). Signals for full-length Rpt subunits might seem similar across our samples (Fig. 6, C and D) because only unassembled Rpt subunits are degraded, and they constitute a small fraction within the total cellular pool of Rpt subunits. In the cell, Rpt subunits mainly exist in the proteasome holoenzymes, relative to early-stage Rpt ring assembly (Fig. 1, A and B, panel iii, lanes 1–4). Also, newly synthesized Rpt subunits constantly replenish the total pool of Rpt subunits. Our data suggest that, during ongoing proteasome assembly in unstressed cells, any excess Rpt subunits are degraded rather than forming puncta.

To confirm whether degradation is specific to Rpt subunits upon chaperone deficiency, or generally applies to other proteasome subunits, we examined a representative subunit of the lid, Rpn11. Lid assembles independently of chaperone-mediated Rpt ring assembly (34, 49). In both WT cells and chaperone deletion mutants, Rpn11 remains stable, as indicated by the lack of free GFP release from Rpn11–GFP (Fig. 6, E and F). An apparent increase in the Rpn11–GFP level in the chaperone mutants can be attributed to transcription induction by Rpn4, a compensatory response to reduced proteasome activity in these chaperone mutants (32, 35). Taken together, these results support our conclusion that excess Rpt subunits relative to chaperones are specifically degraded during early-stage Rpt ring assembly.

By degrading Rpt subunits, the proteasome regulates its own Rpt ring assembly via the chaperones

Our data suggest that excess Rpt subunits are degraded when proteasome holoenzyme assembly is restored in stressed cells (Fig. 3, C and D, lanes 6–8) or is generally active in unstressed cells (Fig. 1, A and B, lanes 2–4). Based on these data, we tested whether the fully-formed proteasome holoenzyme itself might be responsible for degrading any excess unassembled Rpt subunits. For this, we inhibited proteasome activity by adding a specific inhibitor, PS341, during yeast culture. We deleted PDR5, a multidrug exporter, to maintain a high intracellular concentration of PS341 (50). Rpt1 degradation was blocked in nas2Δ, hsm3Δ, and nas2Δhsm3Δ mutants when they were grown in PS341-containing media, as shown by the lack of GFP liberation from the GFP–Rpt1 (Fig. 7A, lanes 6–8). Also, Rpt6 degradation was inhibited in the nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants in the presence of PS341, as evident from the substantial reduction in GFP release from GFP–Rpt6 (Fig. 7B, compare lane 8 to 4). These results suggest that fully-formed proteasome holoenzymes degrade unassembled Rpt subunits, which are not in complex with their cognate chaperones, or are slow to proceed to higher-order complexes. Degradation of Rpt subunits would be self-limiting, in that Rpt subunits (substrates) are spared from degradation upon incorporation into the holoenzyme complex (enzyme). These results suggest that the proteasome may contribute to its own assembly process by degrading excess Rpt subunits.

Figure 7.

By degrading excess Rpt subunits, the proteasome participates in its own assembly. A and B, proteasome inhibition using PS341 stabilizes unassembled Rpt subunits. Yeast cells were grown at 30 °C in the presence of DMSO or PS341 (40 μm) for 4 h. Cells were then harvested by TCA lysis and subjected to 10% BisTris SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (IB) with anti-GFP antibody. Pgk1 is a loading control. C and D, proteasome inhibition induces sequestration of Rpt subunits into puncta (arrowheads) in the chaperone mutants. Live-cell images were obtained using epi-fluorescence microscopy. DMSO or PS341 (80 μm) was added to yeast cells for 4 h during their growth at 30 °C. Scale bars, 5 μm for all panels. E, purification of His6–Rpt1 alone, and the His6–Rpt1/GST–Hsm3 co-complex. Indicated proteins were expressed and purified from E. coli and subjected to 10% BisTris SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. Asterisk, nonspecific cleavage product of His6–Rpt1 (E and F). This band is absent in His6–Rpt1/GST-Hsm3 co-complex (lanes 5 and 6 in F) because Rpt1 is more soluble and stable in complex with its cognate Hsm3 chaperone, as shown previously (13, 15). F, recombinant Rpt1 is degraded by the proteasome, whereas the Rpt1–Hsm3 co-complex is not. Recombinant His6–Rpt1 (50 pmol) from E was mixed with whole-cell extracts (50 μg) from yeast cells in the presence or absence of PS341 (1 mm) at 30 °C for 15 min. Co-complex of His6–Rpt1/:GST-Hsm3 (50 pmol) was also mixed with whole-cell extracts (50 μg) for 15 min at 30 °C. Samples were then subjected to 10% BisTris SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. Pgk1 is loading control.

When proteasome-mediated degradation of Rpt subunits is blocked, the resulting excess subunits formed puncta in both nas2Δhsm3Δ and nas6Δrpn14Δ mutants, even without heat stress (Fig. 7, C and D, arrowheads). These results suggest that excess Rpt subunits are sequestered into puncta when they cannot be readily degraded due to reduced proteasome activity in the cell. These data support our model that degradation of excess Rpt subunits serves as an alternative mechanism to their puncta formation during chaperone-mediated Rpt ring assembly.

Because a vacuole-mediated proteolytic pathway has been shown to degrade proteasome subunits under some conditions, including nitrogen starvation (44, 48), we examined whether this pathway has any role in degrading early-stage Rpt subunits. When we deleted PEP4, a major vacuolar protease (51), both Rpt1 and Rpt6 subunits were still degraded in the chaperone deletion mutants, as evident from free GFP release (Fig. S11, also see the figure legend regarding the molecular mass of GFP fragment). These results support our data that Rpt subunits during early-stage proteasome assembly are degraded by the fully-formed proteasome holoenzyme but not by vacuolar proteases.

In addition to tracking Rpt subunit degradation indirectly via GFP release, we sought to use a direct approach to confirm whether the Rpt subunit is a proteasome substrate and whether chaperone binding can prevent Rpt subunit degradation. For this, we expressed and purified His6-tagged Rpt1 alone or together with its cognate chaperone Hsm3. As shown previously, co-purification between Rpt1 and Hsm3, rather than Rpt1 alone, generates a greater yield of Rpt1 (Fig. 7E) (13, 15). Our purification yielded Hsm3–Rpt1 co-complex in ∼1:1 stoichiometry, based on Coomassie staining. To test whether Rpt1 is degraded by the proteasome, we mixed Rpt1 or Rpt1–Hsm3 co-complex with whole-cell extracts from WT yeast cells because they contain the proteasome as well as ubiquitination machineries necessary for targeting proteins to the proteasome. At 15 min following incubation, His6–Rpt1 is no longer detectable (Fig. 7F, lane 4). This Rpt1 remains stable when proteasome activity is inhibited using PS341 or when Rpt1–Hsm3 co-complex is used as a substrate (Fig. 7F). These results support that excess unassembled Rpt subunits are proteasome substrates.

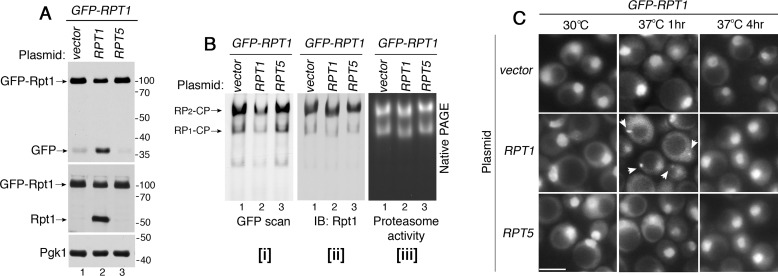

Increasing a Rpt subunit relative to its cognate chaperone results in its degradation and transient sequestration

Our data suggest a model that degradation of Rpt subunits and their sequestration serve to regulate excess Rpt subunits relative to chaperones. We tested whether this model applies to a condition in which all four chaperones are present normally, but a single Rpt subunit exists in excess of its cognate chaperone. For this, we expressed an untagged Rpt1 from a low-copy plasmid in the yeast strain harboring chromosomal GFP–Rpt1. GFP–Rpt1 allows us to sensitively detect even a small subpopulation of Rpt1 that undergoes degradation, based on free GFP liberation (Fig. 6, A and C). Indeed, expression of untagged Rpt1 resulted in degradation of the chromosomal GFP–Rpt1 in unstressed cells (Fig. 8A, lane 2). These data indicate that when the abundance of total Rpt1 is greater than its cognate chaperone, Hsm3, any excess Rpt1 is degraded. To examine whether this degradation also controls stoichiometry among different Rpt subunits, we expressed plasmid-born Rpt5 in the GFP–RPT1 strain. However, excess Rpt5 did not induce degradation of GFP–Rpt1 (Fig. 8A, lane 3). These results support our model, in which the degradation mechanism can eliminate a single excess Rpt subunit relative to its cognate chaperone, rather than the other Rpt subunits, during Rpt ring assembly.

Figure 8.

Increasing a Rpt subunit relative to its cognate chaperone induces its degradation, and transient sequestration. A, Rpt1 undergoes degradation upon expression of excess Rpt1, but not Rpt5. Untagged Rpt1 or Rpt5 were expressed from a low-copy yCP vector in the chromosomal GFP-RPT1 strain. Cells were grown at 30 °C, and were analyzed for free GFP release by 10% BisTris SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (IB). Pgk1 is a loading control. B, both GFP–Rpt1 and untagged Rpt1incorporate into the proteasome holoenzyme in an approximately equal proportion. Whole-cell extracts (60 μg) from the strains in A were resolved using 3.5% native gels, which were scanned to detect GFP–Rpt1 (panel i), and were immunoblotted to detect total Rpt1 in the holoenzyme complexes (panel ii). Proteasome activities were assessed by in-gel peptidase assay (panel iii). In lane 2 of each panel, holoenzyme species migrate slightly faster because they incorporate some untagged Rpt1, instead of all GFP–Rpt1 as in lanes 1 and 3. C, Rpt1 transiently forms puncta specifically upon expression of excess Rpt1, but not Rpt5. GFP–Rpt1 is shown in live-cell images using epi-fluorescence microscopy. Arrowheads indicate Rpt1 subunit puncta, which are specifically detected at 1 h, but not at 4 h following heat stress. Scale bars, 5 μm for all panels.

We then examined whether total Rpt1 in the proteasome holoenzyme consists of GFP–Rpt1 and untagged Rpt1 in equal proportion, using native gels. We first used GFP scan to specifically detect GFP–Rpt1 but not untagged Rpt1. GFP–Rpt1 intensity in the proteasome holoenzyme (RP2–CP and RP1–CP) was decreased in cells expressing plasmid-born Rpt1, as compared with chromosomal GFP–Rpt1 alone (Fig. 8B, panel i, compare lane 2 to 1). However, total Rpt1 in the holoenzyme remains the same as the control GFP–RPT1 strain expressing vector alone (Fig. 8B, panel ii, compare lane 2 to 1). These data indicate that GFP–Rpt1 and untagged Rpt1 together comprise the same total amount of Rpt1 in the holoenzyme complexes. Consistent with our results in Fig. 8A, expression of plasmid-born Rpt5 in the GFP–RPT1 strain did not affect GFP–Rpt1 incorporation into the holoenzyme complexes (Fig. 8B, lane 3). Activities of proteasome holoenzymes are comparable in all samples (Fig. 8B, panel iii).

When excess Rpt1 undergoes degradation at 30 °C (Fig. 8A, lane 2), GFP–Rpt1 puncta were not detectable (Fig. 8C, 30 °C). This supports our model that degradation of excess Rpt subunits serves as an alternative mechanism to their puncta formation. Upon exposure to heat stress for 1 h at 37 °C, GFP–Rpt1 puncta were detectable, specifically upon additional expression of Rpt1, but not Rpt5 (Fig. 8C, arrowheads). However, these Rpt1 subunit puncta are no longer detectable at 4 h upon heat stress. These results suggest that cells may transiently sequester excess Rpt subunits, when all four chaperones exist normally, so as not to overburden chaperones for proper onset of Rpt ring assembly.

Discussion

During proteasome holoenzyme formation, the heterohexameric Rpt ring assembles via four distinct molecular chaperones (11–14, 16, 20). Throughout this process, chaperone actions require associations between individual chaperones and their cognate Rpt subunits. In this study, our findings suggest that cells may promote proper chaperone–Rpt association by two alternative mechanisms, which regulate excess Rpt subunits at the onset of Rpt ring assembly.

Rpt subunit sequestration during chaperone-mediated proteasome assembly

Our findings suggest that, in stressed conditions when cellular needs for protein degradation rise, the chaperone-mediated proteasome assembly becomes crucial, particularly at the onset of Rpt ring assembly (Fig. 1). For this, cells sequester any excess Rpt subunits relative to chaperones (Fig. 2). This sequestration mechanism may serve to balance the level of free Rpt subunits relative to the chaperones, while storing these subunits for proteasome assembly at a later point (Figs. 3–5). This mechanism is relevant to the feature that chaperones are present in substoichiometric amounts to Rpt subunits (52), meaning that excess Rpt subunits would potentially act as a chaperone sink, depleting the chaperones and disrupting proteasome assembly. Among the total cellular Rpt subunits, unassembled Rpt subunits would be a small pool, but this pool seems to exceed the amounts of the chaperones in the cell. Upon heat stress, two representative Rpt subunits, Rpt1 and Rpt6, exhibit some sequestration in WT cells (Fig. S4), suggesting that Rpt subunits are likely to exist in excess of the chaperones. In addition, expressing an additional copy of Rpt1 in WT cells is sufficient to trigger its sequestration into puncta (Fig. 8C), suggesting that chaperones cannot accommodate any excess Rpt subunits.

In stressed conditions when increased proteasome activities are needed, cells transcriptionally induce Rpt subunits, but not the chaperones (31, 32, 35, 36). Instead of up-regulating chaperones, cells may sequester excess Rpt subunits to adapt to dynamically changing conditions. In fact, chaperone overexpression has been shown to interfere with proteasome formation, disrupting the association between RP and CP, as seen in both an overexpression study and pathogenic conditions (53, 54). Because all four chaperones act by sterically hindering premature RP interactions with the CP (12, 13, 18–21), chaperone overexpression would block RP–CP associations in an unregulated manner. Through sequestering excess Rpt subunits into puncta, cells might avoid a risk of disrupting proteasome holoenzyme assembly. Previous studies have shown that specific puncta or granules can sequester fully-formed proteasome holoenzymes, so as to regulate overall proteolytic activity in certain conditions (44, 47, 48). Our study expands this view by providing evidence that proteasome subunit puncta may serve as a mode of regulation for the onset of hexameric Rpt ring assembly of the proteasome.

Proteasome regulates its own assembly process via the chaperones

Our study suggests that excess Rpt subunits can undergo degradation, instead of sequestration. Intriguingly, degradation is proteasome-mediated and is observed during resumption of proteasome assembly in stressed cells and also during ongoing proteasome assembly in unstressed cells (Figs. 6 and 7). Thus, Rpt subunits are both components and substrates of the proteasome. These two fates of Rpt subunits are related and appear to mainly follow cellular proteasome activity. During heat stress, the existing proteasome activity is not sufficient in cells lacking some chaperones, as evident from their growth defects and impaired protein degradation (Fig. 3, E and F, lane 2) (14). When proteasome assembly resumes, Rpt subunits can mainly proceed to the proteasome until the holoenzyme complex is generated to a sufficient level (Fig. 3, C and D, lanes 6–8). Only then, the fully-formed holoenzyme may begin to degrade any remaining excess Rpt subunits (Fig. 6, A and B, lanes 6–8). In unstressed cells at 30 °C, cellular proteasome activity seems largely sufficient, given that chaperone deletion mutants grow like WT cells (14) and can generally degrade ubiquitinated proteins, as compared with 37 °C (Fig. 1, C and D). In this case, excess Rpt subunits are readily degraded (Fig. 6, C and D, lanes 2–4). Because four chaperones together catalyze heterohexameric Rpt ring assembly (11, 14, 16), degradation of excess Rpt subunits does not simply remove chaperone-free Rpt subunits, but might also help minimize untimely assembly events during proteasome holoenzyme formation.

Through degrading the excess Rpt subunits, the holoenzyme itself may contribute to its own chaperone-mediated Rpt ring assembly (Figs. 6–8). It has been shown that completion of proteasome holoenzyme assembly results in eviction of the chaperones, which then recycle to the next round of Rpt ring assembly (12, 19, 22). Thus, the fully-formed holoenzyme not only constitutes the final step of assembly, but also monitors the next round of chaperone-mediated Rpt ring assembly at its onset. Detailed mechanisms remain to be determined as to how these Rpt subunits are targeted for proteasome-mediated degradation. It has been shown that some cancer cells naturally lose expression of chaperones, such as Hsm3 (PSMD5/S5b in humans), resulting in specifically altered cell states, including cellular responses to proteasome inhibitors (55). A future study will be needed to determine whether these two mechanisms in our study are conserved in human cells and have any role in cancers.

Experimental procedures

Biochemical reagents, plasmids, and yeast strains

A complete list of yeast strains is provided in Table 1. Antibodies to Rpt1 and Rpt6 (56) (gifts from Carl Mann; I2BC, Université Paris-Saclay, France) and anti-Rpt5 antibody (Enzo Life Sciences) were used at 1:3000 dilutions. More details regarding anti-Rpt1 and anti-Rpt6 antibodies are included in the Fig. S10 legend. These are rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Anti-GFP antibody (Sigma), anti-ubiquitin antibody (Enzo Life Sciences), anti-His antibody (Sigma), and anti-Pgk1 antibody (Life Technologies, Inc.) are mouse monoclonal antibodies and were used at 1:3000 dilutions, except anti-Pgk1, which was used at 1:10,000. Table 1 lists representative references, in which these antibodies have been used to detect their specific target proteins. At least two biological replicates were performed for all biochemical and imaging experiments.

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| SUB62a | MATa lys2-801 leu2-3, 2--112 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 trp1-1 | 57 |

| SP1694B | MATa nas6::TRP1 | 19 |

| sJR192A | MATa rpn14::hphMX | 13 |

| SP1665A | MATa nas6::TRP1 rpn14::hphMX | 19 |

| SP861 | MATa hsm3::KAN | 12 |

| SP1654B | MATa nas2::KAN | 19 |

| SP2497B | MATa nas2::KAN hsm3::KAN | 19 |

| SP2781A | MATα rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 | Derived from Ref. 14 |

| SP3033A | MATa rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 nas2::KAN | This study |

| SP3032A | MATa rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 hsm3::KAN | This study |

| SP3031A | MATα rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 nas2::KAN hsm3::KAN | This study |

| SP3024A | MATa rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 nas6::HIS3 | This study |

| SP3023A | MATα rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 rpn14::hphMX | This study |

| SP3022A | MATa rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 nas6::HIS3 rpn14::hphMX | This study |

| SP2017 | MATa rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 | Derived from Ref. 14 |

| SP3027A | MATα rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 nas2::KAN | This study |

| SP3026A | MATα rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 hsm3::KAN | This study |

| SP3025A | MATα rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 nas2::KAN hsm3::KAN | This study |

| SP2965C | MATa rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 nas6::HIS3 | This study |

| SP2964B | MATα rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 rpn14::hphMX | This study |

| SP2963A | MATα rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 nas6::HIS3 rpn14::hphMX | This study |

| SP2786A | MATa rpn11::RPN11-GFP (HIS3) | This study |

| SP3321A | MATa rpn11::RPN11-GFP (HIS3) nas6::TRP | This study |

| SP3322A | MATα rpn11::RPN11-GFP (HIS3) rpn14:: hphMX | This study |

| SP3323A | MATα rpn11::RPN11-GFP (HIS3) nas6::TRP rpn14:: hphMX | This study |

| SP3324A | MATa rpn11::RPN11-GFP (HIS3) nas2::NAT | This study |

| SP3325A | MATα rpn11::RPN11-GFP (HIS3) hsm3::KAN | This study |

| SP3326A | MATα rpn11::RPN11-GFP (HIS3) nas2::NAT hsm3::KAN | This study |

| SP3364 | MATα rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 hsp42::KAN | This study |

| SP3367 | MATa rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 hsp42::KAN nas6::HIS3 rpn14::hphMX | This study |

| SP3368 | MATα rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 hsp42::KAN | This study |

| SP3371A | MATα rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 hsp42::KAN nas2::KAN hsm3::KAN | This study |

| SP3363A | MATα rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 pdr5::KAN | This study |

| SP3359A | MATa rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 pdr5::KAN nas2::NAT | This study |

| SP3360A | MATa rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 pdr5::KAN hsm3::KAN | This study |

| SP3358A | MATa rpt1::Prpt1-yEGFP1F-RPT1-LEU2 pdr5::KAN nas2::NAT hsm3::KAN | This study |

| SP3065A | MATα rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 pdr5::KAN | This study |

| SP3067B | MATa rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 pdr5::KAN nas6::HIS3 | This study |

| SP3066B | MATa rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 pdr5::KAN rpn14::hphMX | This study |

| SP3064C | MATa rpt6::Prpt6-yEGFP1F-RPT6-LEU2 pdr5::KAN nas6::HIS3 rpn14::hphMX | This study |

a All strains are isogenic to sub62 genetic background.

Chromosomally integrated GFP-tagged RPT1 (YYS1401) and GFP-tagged RPT6 (YYS1461) strains were obtained from Tanaka Keiji (14). These strains were back-crossed three times to the sub62 strain (57), from which our chaperone deletion strains are derived. Untagged Rpt1 and Rpt5 plasmids were obtained from Jeroen Roelofs (pJR751, pJR753, URA-marked yeast centromere plasmid (YCp) containing the endogenous promoter, ORF, and the terminator). A copper-inducible ubiquitin plasmid (YEp96, TRP-marked high-copy plasmid, under the control of the CUP1 promoter) and vector (pES12) were obtained from Mark Hochstrasser (58, 59).

Preparation of yeast cells for live-cell imaging

Yeast cells were grown to A600 = 0.8 and were diluted to A600 = 0.3 in 25 ml of fresh YPD for heat stress or incubation with PS341 (40 μm, Fig. 7, A and B; 80 μm, Fig. 7, C and D) and cycloheximide (150 μg/ml). Total A600 = 7 worth of yeast cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 2 min. Cell pellets were washed twice with 1 ml of YNB media and then resuspended in 20 μl of YNB. Seven μl of the cell suspension was then spotted onto a glass slide with a No. 1.5 coverslip. The glass slide was coated with a 1:1 mixture of polylysine (0.1%) and concanavanine solution (2 mg/ml). Coverslips were sealed to glass slides using VaLap.

For DAPI staining, harvested cells were resuspended in 80% ethanol for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were spun down at 3000 × g for 2 min and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. DAPI was added to the cell suspension at a final 1 μg/ml concentration. Cells were then incubated for 20 min at room temperature and washed one time in 1 ml of PBS. Cell pellets were resuspended in 10 μl of PBS and mounted on the glass slide with a coverslip.

Epi-fluorescence imaging of yeast cells

Fluorescence microscopy was performed using an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope with Prior Lumen Pro200 metal halide lamp, Hamamatsu ORCA-R2 CCD camera, motorized Prior ProScan III stage, ×100 UPLSAPO 1.40NA oil immersion objective, and optical filters for DAPI (Chroma 49000) and EGFP (Chroma 49002). SlideBook 6.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations (3i)) was used to acquire the images. All images were acquired and adjusted identically allowing for direct comparison. Z-series images were acquired at 1.0-μm steps. Maximum intensity projection images were generated using FIJI (ImageJ, National Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence staining of Rpt subunits in yeast cells

Ten ml of yeast cells at A600 = 0.8 were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, using a rotator. Cells were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 3 min and washed two times with 5 ml of 0.1 m KHPO4 (pH 6.5) and once more with 5 ml of K-sorb (1.2 m sorbitol in 0.1 m KPHO4 (pH 6.5)). The cell pellet was resuspended in 550 μl of K-sorb. For spheroplasting, 500 μl of the fixed cells were incubated with 10 μl of β-mercaptoethanol and 5 μl of zymolase at 0.1 mg/ml final for 20 min at room temperature on a rotator. Cells were spun down at 3000 × g for 2 min and were washed once with 1.5 ml of K-sorb and resuspended in 50 μl of K-sorb. Twenty μl of spheroplast cells were placed onto a glass slide coated with a 1:1 mixture of polylysine (0.1%) and concanavanine solution (2 mg/ml). Slides were plunged into −20 °C methanol for 6 min and then −20 °C acetone for 30 s, followed by air-drying for 1–2 min. The slides were then incubated in blocking solution (PBS with 1% BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. PBS/BSA was then aspirated, and the primary antibody was diluted in PBS/BSA at 1:1000 dilution and incubated with the slides overnight at 4 °C. The slides were washed with PBS/BSA three times for 5 min each at room temperature. Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit antibody) was diluted in PBS/BSA at 1:500 and was added to the slides for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were washed with PBS/BSA three times for 5 min each, and with PBS alone two times for 5 min each. DAPI (5 μg/ml in PBS) was added to the slides for 15 min, followed by two washes with PBS for 5 min each. A coverslip was mounted over the cells in Prolong Gold (Invitrogen), and the slide was imaged as described.

Native PAGE and in-gel peptidase assay

Overnight yeast cultures were diluted to A600 = 0.3 and grown to approximately A600 = 2 to examine proteasome level and activity at 30 °C. For heat stress, the log-phase cultures were diluted to A600 = 0.3 in fresh YPD in a total volume of 100 ml and further incubated at 37 °C for 4 h or as specified. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 5 min and were washed once with ice-cold water. Cells were then directly frozen into liquid nitrogen in a dropwise manner. To obtain cryo-lysates, the frozen yeast cells were ground in a mortar and pestle in the presence of liquid nitrogen. The ground powders were hydrated in the proteasome buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol) supplemented with 1 mm ATP, and then centrifuged at 15,000 × g twice for 15 min each in the cold room. Samples were then loaded onto 3.5% native gels and electrophoresed for 3 h at 100 V in the cold room. In-gel peptidase assays were conducted using the fluorogenic peptide substrate LLVY-AMC as described previously (60). Native gels were photographed under UV light using GENE FLASH (SynGene Bio Imaging) to detect proteasome activities and were then scanned to visualize proteasomal complexes that incorporated GFP-tagged Rpt subunits using Amersham Biosciences Typhoon scanner (GE Healthcare), using a Cy2 filter at a pixel size of 100 μm.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from yeast cells at A600 = 0.8, and 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA in a 200-μl reaction with oligo(dT) primer and a reverse transcriptase. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

TCA lysis of yeast cells for SDS-PAGE

Overnight yeast cultures were diluted to A600 = 0.3 in 35 ml of YPD and grown to A600 = 0.8–1.0 for 30 °C samples. For heat stress at 37 °C, the log-phase cultures were diluted to A600 = 0.3 in 35 ml of fresh YPD media and grown for 4 h. A600 = 7 worth of cells were then harvested. Cell pellets were then washed with 20% TCA and were frozen at −80 °C. To conduct TCA lysis, the pellets were first thawed on ice and resuspended in 250 μl of 20% TCA. Approximately 250 μl of glass beads (425–600 μm) were added and vortexed for 1 min, three times in total, with cooling samples on ice between each vortex. To collect lysates, these tubes were pierced at the bottom, nestled into new tubes, and centrifuged for 10 s each, 4–5 times until all lysates are collected in the bottom tubes. The beads in the top tube were washed with 375 μl of 5% TCA. At this time, the beads were removed. The collected lysates were mixed with 625 μl of 5% TCA, vortexed to resuspend all pellets, and centrifuged again at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellets were washed once with 750 μl of 100% ethanol and resuspended in 40 μl of 1 m Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). The resulting lysates were mixed with 40 μl of Laemmli sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Ten μl of samples were loaded onto 10% BisTris SDS-polyacrylamide gels.

Immunoblotting

Following the transfer of an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, or a native polyacrylamide gel to a PVDF membrane, immunoblotting was conducted at room temperature as follows. The PVDF membrane was incubated in 20 ml of blocking buffer (TBST: TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h. The membrane was washed twice using TBST for 10 min. The membrane was incubated with primary antibodies, which were diluted in blocking buffer, for 1 h (specific dilutions for individual antibodies are indicated under “Biochemical reagents, plasmids, and yeast strains”). Two washes using TBST were conducted as above. Incubation with the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:3000 dilutions in blocking buffer) was also conducted for 1 h, followed by two washes using TBST. PVDF membranes were subjected to enhanced chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Western blotting Chemiluminescence Reagents Plus) and exposed to X-ray films that were developed using a Kodak X-OMAT processor.

Expression and purification of Rpt1 and Rpt1–Hsm3 co-complex

His6-tagged Rpt1 and GST–Hsm3 were expressed in Escherichia coli from the pRSF–Duet1 plasmid (pJR200) and pGEX6P-1–derived plasmid (pJR89) (13). Both plasmids are gifts from Jeroen Roelofs. All E. coli cultures were frozen as droplets into liquid nitrogen and ground into a powder using a mortar and pestle (12). Ground powder was hydrated in lysis buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 300 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol) containing 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, ATP (1 mm), and protease inhibitors. To isolate the Rpt1–Hsm3 co-complex, we individually expressed His6-tagged Rpt1 and GST–Hsm3 in E. coli and mixed the cryo-powders in equal volume. His6–Rpt1 was affinity-purified alone. Following the hydration of the ground powder, Triton X-100 was added to 0.2% final to promote solubilization of the lysates. The resulting lysates were then cleared at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The cleared lysates were incubated with 200 μl of TALON metal-affinity resin (Clontech) for 1 h at 4 °C. Bead-bound proteins were collected by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 5 min and washed with 15 ml of the lysis buffer containing 0.2% Triton X-100 three times. The beads were washed twice with 400 μl of lysis buffer. His-tagged proteins were eluted with 250 μl of lysis buffer containing 150 mm imidazole by rotating for 1 h at 4 °C. Eluates were dialyzed in buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 100 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol) overnight at 4 °C.

Author contributions

A. N. and S. P. conceptualization; A. N., X. F., and G. P. data curation; A. N. formal analysis; A. N., X. F., G. P., and J. D. O. investigation; J. D. O. resources; J. D. O. methodology; J. D. O. and S. P. writing-original draft; J. D. O. and S. P. writing-review and editing; S. P. supervision; S. P. funding acquisition; S. P. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeroen Roelofs, Tanaka Keiji, Carl Mann, and Mark Hochstrasser for sharing yeast strains, plasmids, and antibodies. We also thank Allyson Malloy and Mark Larsen for their assistance with biochemical and imaging experiments. All microscopy was performed at the Light Microscopy Facility at the University of Colorado Boulder.

This work was supported by Boettcher Webb-Waring Biomedical Research Award, a University of Colorado Start-up fund, and National Institutes of Health Grant 1R01GM127688-01A1 (to S. P.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S11, Table S1, and Refs. 1–15.

- RP

- regulatory particle

- CP

- core particle

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- EGFP

- enhanced GFP

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- PVDF

- polyvinylidene difluoride; aminomethylcoumarin.

References

- 1. da Fonseca P. C., He J., and Morris E. P. (2012) Molecular model of the human 26S proteasome. Mol. Cell 46, 54–66 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lander G. C., Estrin E., Matyskiela M. E., Bashore C., Nogales E., and Martin A. (2012) Complete subunit architecture of the proteasome regulatory particle. Nature 482, 186–191 10.1038/nature10774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lasker K., Förster F., Bohn S., Walzthoeni T., Villa E., Unverdorben P., Beck F., Aebersold R., Sali A., and Baumeister W. (2012) Molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome holocomplex determined by an integrative approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1380–1387 10.1073/pnas.1120559109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Finley D. (2009) Recognition and processing of ubiquitin–protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 477–513 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Groll M., Ditzel L., Löwe J., Stock D., Bochtler M., Bartunik H. D., and Huber R. (1997) Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature 386, 463–471 10.1038/386463a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rabl J., Smith D. M., Yu Y., Chang S. C., Goldberg A. L., and Cheng Y. (2008) Mechanism of gate opening in the 20S proteasome by the proteasomal ATPases. Mol. Cell 30, 360–368 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith D. M., Chang S. C., Park S., Finley D., Cheng Y., and Goldberg A. L. (2007) Docking of the proteasomal ATPases' carboxyl termini in the 20S proteasome's α ring opens the gate for substrate entry. Mol. Cell 27, 731–744 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glickman M. H., Rubin D. M., Coux O., Wefes I., Pfeifer G., Cjeka Z., Baumeister W., Fried V. A., and Finley D. (1998) A subcomplex of the proteasome regulatory particle required for ubiquitin-conjugate degradation and related to the COP9-signalosome and eIF3. Cell 94, 615–623 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81603-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tomko R. J. Jr., Funakoshi M., Schneider K., Wang J., and Hochstrasser M. (2010) Heterohexameric ring arrangement of the eukaryotic proteasomal ATPases: implications for proteasome structure and assembly. Mol. Cell 38, 393–403 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Förster F., Lasker K., Beck F., Nickell S., Sali A., and Baumeister W. (2009) An atomic model AAA-ATPase/20S core particle subcomplex of the 26S proteasome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 388, 228–233 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Funakoshi M., Tomko R. J. Jr., Kobayashi H., and Hochstrasser M. (2009) Multiple assembly chaperones govern biogenesis of the proteasome regulatory particle base. Cell 137, 887–899 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park S., Roelofs J., Kim W., Robert J., Schmidt M., Gygi S. P., and Finley D. (2009) Hexameric assembly of the proteasomal ATPases is templated through their C termini. Nature 459, 866–870 10.1038/nature08065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roelofs J., Park S., Haas W., Tian G., McAllister F. E., Huo Y., Lee B. H., Zhang F., Shi Y., Gygi S. P., and Finley D. (2009) Chaperone-mediated pathway of proteasome regulatory particle assembly. Nature 459, 861–865 10.1038/nature08063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saeki Y., Toh-E A., Kudo T., Kawamura H., and Tanaka K. (2009) Multiple proteasome-interacting proteins assist the assembly of the yeast 19S regulatory particle. Cell 137, 900–913 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Le Tallec B., Barrault M. B., Guérois R., Carré T., and Peyroche A. (2009) Hsm3/S5b participates in the assembly pathway of the 19S regulatory particle of the proteasome. Mol. Cell 33, 389–399 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaneko T., Hamazaki J., Iemura S., Sasaki K., Furuyama K., Natsume T., Tanaka K., and Murata S. (2009) Assembly pathway of the mammalian proteasome base subcomplex is mediated by multiple specific chaperones. Cell 137, 914–925 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thompson D., Hakala K., and DeMartino G. N. (2009) Subcomplexes of PA700, the 19 S regulator of the 26 S proteasome, reveal relative roles of AAA subunits in 26 S proteasome assembly and activation and ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24891–24903 10.1074/jbc.M109.023218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barrault M. B., Richet N., Godard C., Murciano B., Le Tallec B., Rousseau E., Legrand P., Charbonnier J. B., Le Du M. H., Guérois R., Ochsenbein F., and Peyroche A. (2012) Dual functions of the Hsm3 protein in chaperoning and scaffolding regulatory particle subunits during the proteasome assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1001–E1010 10.1073/pnas.1116538109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li F., Tian G., Langager D., Sokolova V., Finley D., and Park S. (2017) Nucleotide-dependent switch in proteasome assembly mediated by the Nas6 chaperone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 1548–1553 10.1073/pnas.1612922114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park S., Li X., Kim H. M., Singh C. R., Tian G., Hoyt M. A., Lovell S., Battaile K. P., Zolkiewski M., Coffino P., Roelofs J., Cheng Y., and Finley D. (2013) Reconfiguration of the proteasome during chaperone-mediated assembly. Nature 497, 512–516 10.1038/nature12123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Satoh T., Saeki Y., Hiromoto T., Wang Y. H., Uekusa Y., Yagi H., Yoshihara H., Yagi-Utsumi M., Mizushima T., Tanaka K., and Kato K. (2014) Structural basis for proteasome formation controlled by an assembly chaperone nas2. Structure 22, 731–743 10.1016/j.str.2014.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sokolova V., Li F., Polovin G., and Park S. (2015) Proteasome activation is mediated via a functional switch of the Rpt6 C-terminal tail following chaperone-dependent assembly. Sci. Rep. 5, 14909 10.1038/srep14909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hanssum A., Zhong Z., Rousseau A., Krzyzosiak A., Sigurdardottir A., and Bertolotti A. (2014) An inducible chaperone adapts proteasome assembly to stress. Mol. Cell 55, 566–577 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rousseau A., and Bertolotti A. (2016) An evolutionarily conserved pathway controls proteasome homeostasis. Nature 536, 184–189 10.1038/nature18943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Groll M., Bajorek M., Köhler A., Moroder L., Rubin D. M., Huber R., Glickman M. H., and Finley D. (2000) A gated channel into the proteasome core particle. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 1062–1067 10.1038/80992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Isono E., Nishihara K., Saeki Y., Yashiroda H., Kamata N., Ge L., Ueda T., Kikuchi Y., Tanaka K., Nakano A., and Toh-e A. (2007) The assembly pathway of the 19S regulatory particle of the yeast 26S proteasome. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 569–580 10.1091/mbc.e06-07-0635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lehmann A., Janek K., Braun B., Kloetzel P. M., and Enenkel C. (2002) 20 S proteasomes are imported as precursor complexes into the nucleus of yeast. J. Mol. Biol. 317, 401–413 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fehlker M., Wendler P., Lehmann A., and Enenkel C. (2003) Blm3 is part of nascent proteasomes and is involved in a late stage of nuclear proteasome assembly. EMBO Rep. 4, 959–963 10.1038/sj.embor.embor938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wendler P., Lehmann A., Janek K., Baumgart S., and Enenkel C. (2004) The bipartite nuclear localization sequence of Rpn2 is required for nuclear import of proteasomal base complexes via karyopherin αβ and proteasome functions. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37751–37762 10.1074/jbc.M403551200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Russell S. J., Steger K. A., and Johnston S. A. (1999) Subcellular localization, stoichiometry, and protein levels of 26 S proteasome subunits in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21943–21952 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mannhaupt G., Schnall R., Karpov V., Vetter I., and Feldmann H. (1999) Rpn4p acts as a transcription factor by binding to PACE, a nonamer box found upstream of 26S proteasomal and other genes in yeast. FEBS Lett. 450, 27–34 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00467-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]