Abstract

Ether-a-go-go family (EAG) channels play a major role in many physiological processes in humans, including cardiac repolarization and cell proliferation. Cryo-EM structures of two of them, KV10.1 and human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG or KV11.1), have revealed an original nondomain-swapped structure, suggesting that the mechanism of voltage-dependent gating of these two channels is quite different from the classical mechanical-lever model. Molecular aspects of hERG voltage-gating have been extensively studied, indicating that the S4-S5 linker (S4-S5L) acts as a ligand binding to the S6 gate (S6 C-terminal part, S6T) and stabilizes it in a closed state. Moreover, the N-terminal extremity of the channel, called N-Cap, has been suggested to interact with S4-S5L to modulate channel voltage-dependent gating, as N-Cap deletion drastically accelerates hERG channel deactivation. In this study, using COS-7 cells, site-directed mutagenesis, electrophysiological measurements, and immunofluorescence confocal microscopy, we addressed whether these two major mechanisms of voltage-dependent gating are conserved in KV10.2 channels. Using cysteine bridges and S4-S5L–mimicking peptides, we show that the ligand/receptor model is conserved in KV10.2, suggesting that this model is a hallmark of EAG channels. Truncation of the N-Cap domain, Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain, or both in KV10.2 abolished the current and altered channel trafficking to the membrane, unlike for the hERG channel in which N-Cap and PAS domain truncations mainly affected channel deactivation. Our results suggest that EAG channels function via a conserved ligand/receptor model of voltage gating, but that the N-Cap and PAS domains have different roles in these channels.

Keywords: ion channel, electrophysiology, peptides, physiology, biophysics, allosteric regulation, EAG channel, Kv 10.2 channel, S4-S5 linker, S6 C-terminus, voltage dependence

Introduction

Voltage-gated potassium (KV) channels regulate a variety of cellular processes, including membrane polarization (1, 2), apoptosis (3), cell proliferation (4), and cell volume (5). In connection with such a variety of functions of KV channels, mutations in these channels cause a variety of pathological conditions in humans: neurological disorders (6, 7), cardiac arrhythmias (2), multiple sclerosis (8), and pain syndrome (9). It has also been shown that KV channels are associated with the development of malignant tumors cancer (10). KV10 channels belong to the ether-a-go-go family (EAG),5 as hERG channels. Two isoforms of KV10 channels are expressed in mammals: KV10.1 (eag1) and KV10.2 (eag2), which show 70% amino acid sequence identity. KV10.1 has been detected mainly in the brain, whereas KV10.2 is also expressed in other tissues such as the skeletal muscles, heart, placenta, lungs, and liver (11).

Atomic structures of rat KV10.1 (12) and human hERG (KV11.1) channels (13) highlighted many structural similarities: nonswapped pore and voltage domains, i.e. facing voltage-sensor and pore domains are from the same subunit, short S4-S5 linkers (S4-S5L) and similar N-terminal structures such as Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) and N-Cap domains. We hypothesized that molecular mechanisms of gating identified in hERG may apply to the closely related KV10 channels.

In the heart, deactivation of hERG channels (closing of the activation gate) is slow, allowing a major role for this channel in the late repolarization phase of the action potential. In this channel, two mechanisms have been shown to play a major role in the deactivation process.

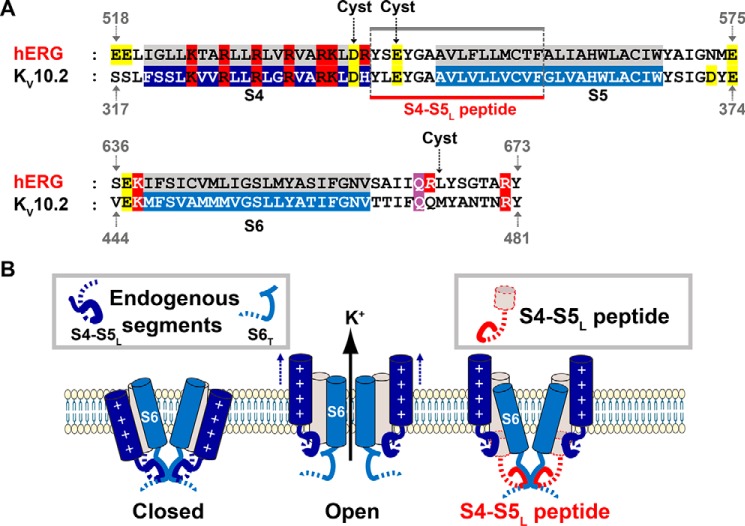

First, hERG deactivation is due to a voltage-dependent interaction between the S4-S5 region, including the S4-S5 linker and a part of S5 (named S4-S5L, Fig. 1A) and the C-terminal part of the S6 segment (named here S6T), which is the activation gate (14, 15). In other words, at resting potentials, S4-S5L (the ligand) is bound to the S6T gate (the receptor) and locks it in a closed state (as shown in Fig. 1B, left). Upon membrane depolarization, S4 drags S4-S5L out of the S6T gate, and the channel opens (Fig. 1B, middle). Upon repolarization S4-S5L binds to the S6T gate and channel deactivates (back to Fig. 1B, left). Here, using two distinct approaches, we observe that this ligand/receptor mechanism, which we originally proposed for hERG, is conserved in KV10.2 (15).

Figure 1.

Alignment used to design the cysteine mutants and the S4-S5L peptide, hypothetical ligand/receptor model. A, alignment between hERG and KV10.2. This alignment was used to (i) introduce the cysteines in S4-S5L and S6T and (ii) design the S4-S5L peptide from the previously identified hERG S4-S5L inhibiting peptide. S4-S5L refers to the S4-S5 region, including the S4-S5 linker and a part of S5. S6T refers to the C-terminal part of the S6 segment, which is the activation gate. The alignment was obtained using Cobalt (43). In red are represented the basic residues, in yellow acidic residues, and in purple the position of the narrowest part of the bundle crossing, also the gating residue (44). The color boxes represent the transmembrane segments. Introduced cysteines in hERG (15) and KV10.2 in the present study are indicated. Gray line represents the inhibiting S4-S5L peptide in hERG (15). Red line represents the peptide engineered in KV10.2 for the present study. B, left: scheme of the hypothetical ligand/receptor model in which S4-S5L (deep blue) binds to S6T (light blue) to stabilize the channel in a closed state. Middle, upon membrane depolarization, S4 pulls S4-S5L out of the S6T receptor, allowing channel opening. Right, the KV10.2 S4-S5L peptide (red) mimics endogenous S4-S5L, locking the channel in its closed conformation.

Second, hERG deactivation is modulated by the channel N terminus. In the N-terminal eag domain, deletion in the N-Cap and/or the PAS domains, profoundly accelerated deactivation with no major effect on maximal current amplitude (16–19). Moreover, covalent binding of the N-Cap and the S4-S5L closed the channel (20). These observations suggested that the N-Cap and/or the PAS domains regulate channel deactivation by modulating S4-S5L and S6T interaction. In KV10.2, we show that the eag domain presents quite different functions. Deletions of the N-Cap and PAS domains, separately or altogether, completely abolish channel activity, at least partially due to a defect in membrane trafficking.

In conclusion, we show that slowing activating channels follow an allosteric model, in which the voltage sensor and pore domains are weakly coupled, via a ligand, S4-S5L and a receptor, S6T. In KV10.2, such coupling is not modulated by the eag domain, as proposed for hERG (20).

Results

As in hERG, covalent binding of S4-S5L to S6T locks the KV10.2 channel closed

The similar structures of hERG and KV10.1 (12, 13) showing a nonswapped arrangement of the pore and voltage sensor domains suggest that voltage-gating of these channels does not follow the classical mechanical-lever model in which S4-S5L constricts the S6T gate (21). Also, functional evidence obtained by several groups including ours, strongly suggests that hERG channels do not follow the mechanical-lever model (14, 15). First, Ferrer and collaborators, observed that introduction of a cysteine in S4-S5L (D540C) and another cysteine in S6T (L666C) locks the channel in a closed state in oxidative conditions. This was associated to a restricted movement of the voltage sensor in a oxidative condition, as measured by gating currents, suggesting the formation of a disulfide bridge (14). Also, mutagenesis experiments on hERG suggested electrostatic interaction between Asp-540 and Leu-666 playing a major role in hERG voltage-dependent gating (22). Such observations suggest that in the WT hERG channel, specific interactions between S4-S5L and the activation gate (S6T) stabilize the closed channel. In transfected COS-7 cells, we could reproduce the experiments originally done by Ferrer and collaborators (14) in the Xenopus oocyte model. Moreover we could observe that a S4-S5L mimicking peptide inhibits the hERG channel, suggesting a ligand/receptor model, in which S4-S5L, directly under the control of the voltage sensor S4, binds to S6T to lock the channel in a closed state (see Fig. 1B, right).

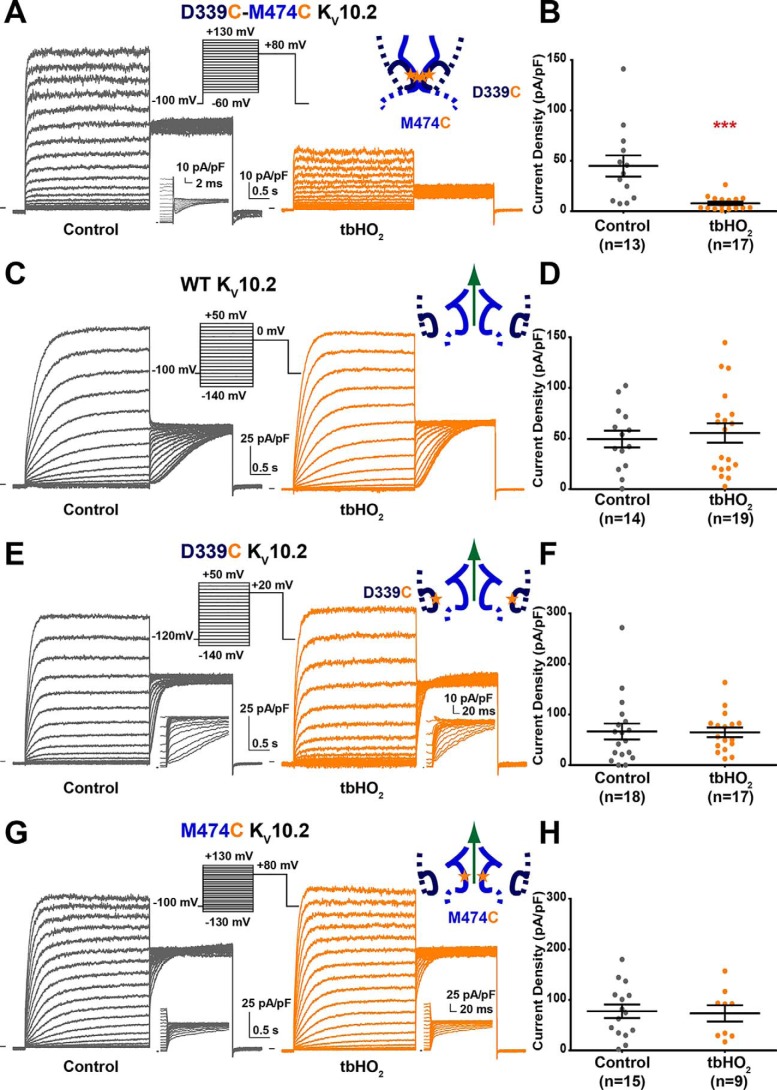

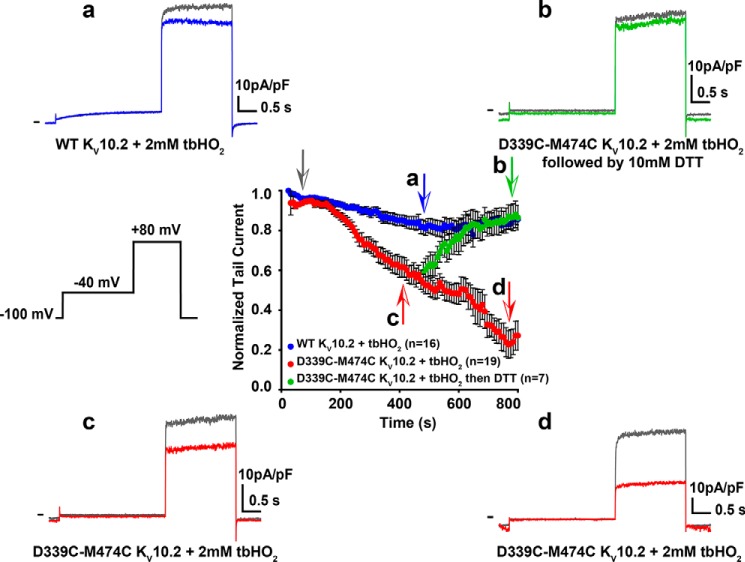

To check whether KV10.2 channels follow the same voltage-gating mechanism as hERG channels, we aligned the amino acid sequences of the two channels, and mutated to a cysteine Asp-339 and Met-474 in KV10.2, corresponding to hERG positions in which cysteines were previously introduced: Asp-540 in S4-S5L and Leu-666 in S6T (14, 15) (black arrows in Fig. 1A). As for the hERG double cysteine mutant, a 2-h application of 0.2 mm tert-butylhydroperoxide (tbHO2) led to an almost complete inhibition of the D339C/M474C KV10.2 channel current (Fig. 2, A and B). Knowing the high homology between hERG and KV10.2 (65%), we supposed that D339C and M474C in KV10.2 also form a disulfide bridge in oxidative conditions, as a cause of the drastic current reduction. As control experiments, 0.2 mm tbHO2 application had no effect on tail current amplitude when only one (D339C or M474C KV10.2) or none (WT KV10.2) of the two cysteines was introduced (Fig. 2, C–H) and activation curves showed a similar shift in all conditions (Fig. S1). Because a 2-h tbHO2 application represents a slow time course for a putative disulfide bridge formation, we also applied a higher concentration of tbHO2 (2 mm) for a shorter time. As in the Ferrer study (14) on hERG, this concentration led, in around 12 min, to an almost complete inhibition of the D339C/M474C KV10.2 channel current but not the WT channel current (Fig. 3). This inhibition was reversed by 10 mm DTT, as in the Ferrer study on hERG (14).

Figure 2.

Introduction of 2 cysteines in the S4-S5L and S6T regions of KV10.2 (D339C/M474C KV10.2) locks the channel closed in oxidative conditions. A, representative, superimposed recordings of the D339C/M474C KV10.2 current after 2 h incubation in Tyrode without (control) or with 0.2 mm tbHO2 (tbHO2). Left inset, activation voltage protocol used (one sweep every 8 s). Right inset, scheme of S4-S5L/S6T with introduced cysteines (stars). B, mean ± S.E. D339C/M474C KV10.2 maximum tail-current density, in control or tbHO2. ***, p < 0.001 versus control, Mann-Whitney test. C and D, same as A and B for WT KV10.2. E and F, same as A and B for D339C KV10.2. G and H, same as A and B for M474C KV10.2.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of D339C/M474C KV10.2 current reduction upon addition of 2 mm tbHO2. Time course of the effect of tbHO2 application on normalized WT and D339C/M474C KV10.2 tail currents. From a holding potential of −100 mV, followed by a 3-s prepulse at −40 mV, tail currents were recorded at +80 mV, every 8 s. Following stabilization of the tail current, 2 mm tbHO2 was perfused (gray arrow), and the step protocol was repeated for 6 min. Following the tbHO2 application, a fraction of the cells was then perfused with 10 mm DTT, and the step protocol was continued for an additional 6 min. Each data point represents the mean ± S.E. current magnitude normalized to values obtained before tbHO2, n = 16 (WT), 19 (D339C/M474C in tbHO2), and 7 (D339C/M474C in DTT). Insets (a–d) correspond to representative recordings at the arrows.

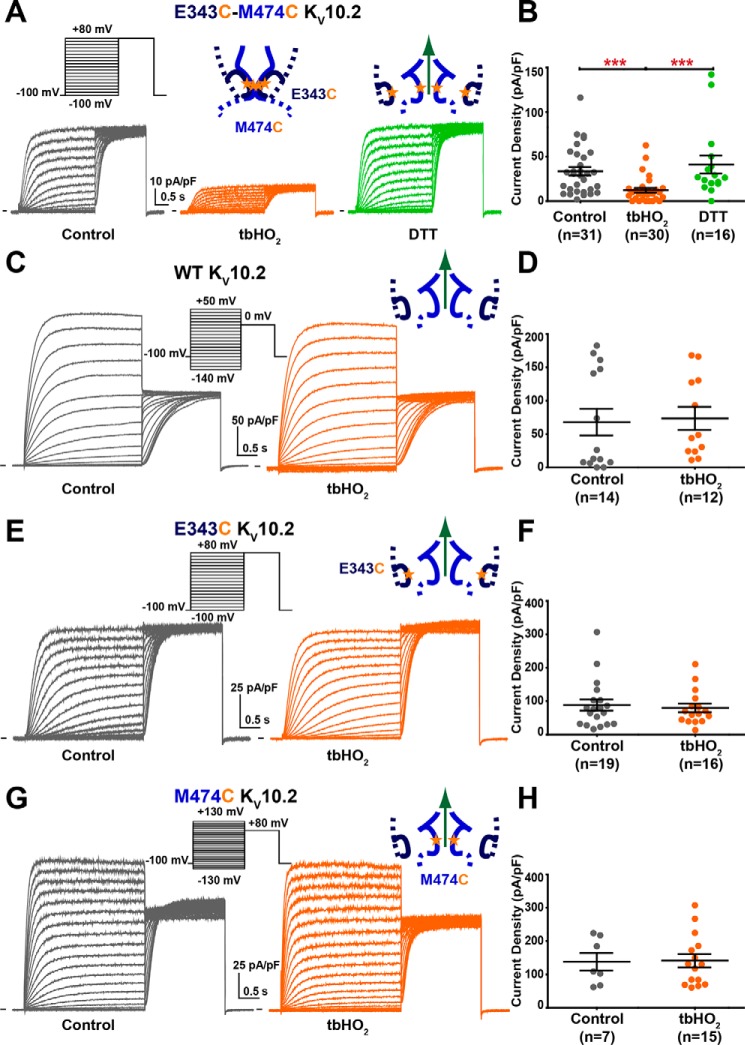

To strengthen the hypothesis of the interaction between S4-S5L and S6T in KV10.2, we also tested the tbHO2 effect on another double mutant of the KV10.2 channel. We chose the E343C/M474C KV10.2 channel, because Glu-343, in S4-S5L, is aligned with Glu-544 in hERG, which when mutated to a cysteine together with L666C in hERG S6T (Fig. 1A), also lead to channel inhibition, suggesting the formation of a disulfide bridge (15). We observed an inhibition of the current after 15 min incubation of 2 mm tbHO2, which is reversed by 10 mm DTT (Fig. 4, A and B). Control experiments showed no effect either on tail current amplitude or on the activation curve when only one (E343C or M474C KV10.2) or none (WT KV10.2) of the two cysteines was introduced (Fig. 4, C–H, Fig. S2). Altogether, these observations confirmed that two different disulfide bridges created between the two introduced cysteines in S4-S5L and S6T locks KV10.2 in a closed state, as in hERG (14, 15).

Figure 4.

Introduction of 2 cysteines in the S4-S5L and S6T regions of KV10.2 (E343C/M474C KV10.2) locks the channel closed in oxidative conditions. A, representative, superimposed recordings of the E343C/M474C KV10.2 current after 15 min incubation in Tyrode without (control) or with 2 mm tbHO2 (tbHO2), or after a subsequent 5-min incubation in 10 mm DTT. Left inset, activation voltage protocol used (one sweep every 8 s). Middle and right insets, schemes of S4-S5L/S6T with introduced cysteines in the presence of tbHO2 or DTT, respectively (stars). B, mean ± S.E. E343C/M474C KV10.2 maximum tail-current density, in control, tbHO2, or tbHO2 followed by DTT. ***, p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney test. C and D, same as A and B for WT KV10.2. E and F, same as A and B for E343C KV10.2. G and H, same as A and B for M474C KV10.2.

As in hERG, a KV10.2 S4-S5L mimicking peptide inhibits KV10.2 channels

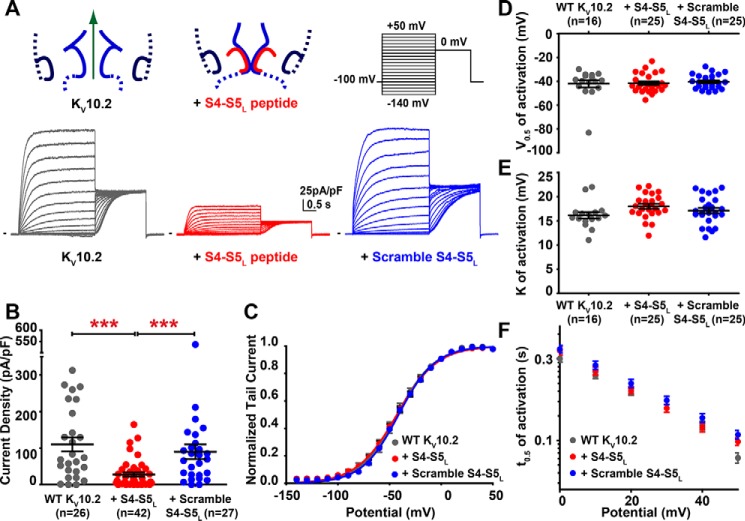

Recently, we observed that (i) co-expressing a hERG S4-S5L mimicking peptide with hERG channel partially inhibited the generated current and (ii) covalently binding this peptide to the hERG channel completely inhibited it (15). These observations suggest that in hERG channels, S4-S5L rather acts as a voltage-controlled ligand that binds to the S6T gate and stabilizes it in the closed state (Fig. 1B, left, for the endogenous interaction and B, right, for the mimicking peptide). This mechanism of gating is consistent with Ferrer et al. (14) observation that covalent binding of S4-S5L and S6T channel regions locks the channel in a closed state. Using the alignment between hERG and KV10.2 (Fig. 1A), we designed the KV10.2 S4-S5L peptide from the position of the S4-S5L peptide sequence that was inhibiting the hERG channel (15). Co-expressing the KV10.2 channel with its specific S4-S5L peptide led to a profound decrease in current density (more than 70%), with no shift in the activation curve, as observed for hERG (Fig. 5, A–E). As an additional control, co-expressing KV10.2 with a scramble S4-S5L peptide led to current density similar to the one observed in the absence of peptide (Fig. 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

S4-S5L peptide inhibits KV10.2 channels. A, representative, superimposed recordings of the WT KV10.2 current in the absence (left; 2 μg of KV10.2 plus 2 μg of GFP encoding plasmids), in the presence of S4-S5L peptide (middle; 2 μg of KV10.2 plus 2 μg of peptide encoding plasmids), and in the presence of a scramble S4-S5L peptide (right; 2 μg of KV10.2 plus 2 μg of peptide encoding plasmids). Left insets: schemes of the hypothetical effect of the S4-S5L inhibiting peptide on KV10.2 channel; right inset: activation voltage protocol used (one sweep every 8 s). B, mean ± S.E. KV10.2 maximum tail-current density in the absence or presence of the indicated peptide (S4-S5L peptide or scramble S4-S5L peptide). ***, p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney test. C, activation curve, obtained from tail currents using the protocol shown in A, in the absence or presence of the indicated peptide (n = 16–25). D, mean ± S.E. half-activation potential in the absence or presence of the indicated peptide. E, mean ± S.E. activation curve slope in the absence or presence of the indicated peptide. F, mean ± S.E. half-activation time as a function of membrane potential, in the absence or presence of the indicated peptide.

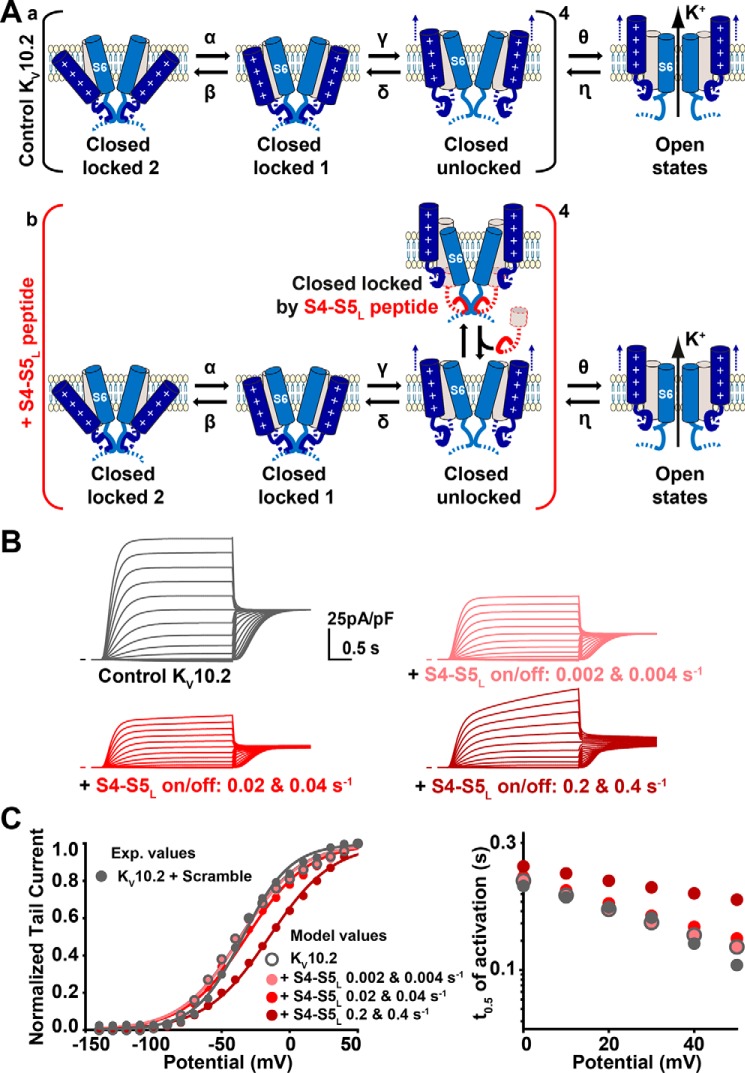

Because the S4-S5L peptide is supposed to interfere with the gating, it may be intriguing that activating and tail currents are inhibited to the same extent, and that neither the activation curve, nor the activation kinetics are modified (Fig. 5, C–F). To address this issue, we used a kinetic model mimicking channel activity in the presence/absence of the peptide (Fig. 6), based on a previous model of KCNE1–KCNQ1 and S4-S5L peptide interaction (23). In the KCNE1–KCNQ1 model, the presence of the peptides was affecting the channel activation curve and activation kinetics. However, when constrained to KV10.2 kinetics, the model did not show any alteration of activation kinetics or steady-state activation (Fig. 6, B and C). This is because peptide binding and unbinding rates (0.02 and 0.04 s−1, respectively) are lower than channel opening/closing rates, because increasing these rates leads to alterations in channel activation kinetics and steady-state activation (Fig. 6, B and C). A peptide with similar binding/unbinding rates impact KCNE1–KCNQ1 channel activation curve and activation kinetics (23) because gating kinetics of this channel are slower than KV10.2 kinetics. Altogether, these observations support the ligand/receptor model of voltage dependence in KV10 channels.

Figure 6.

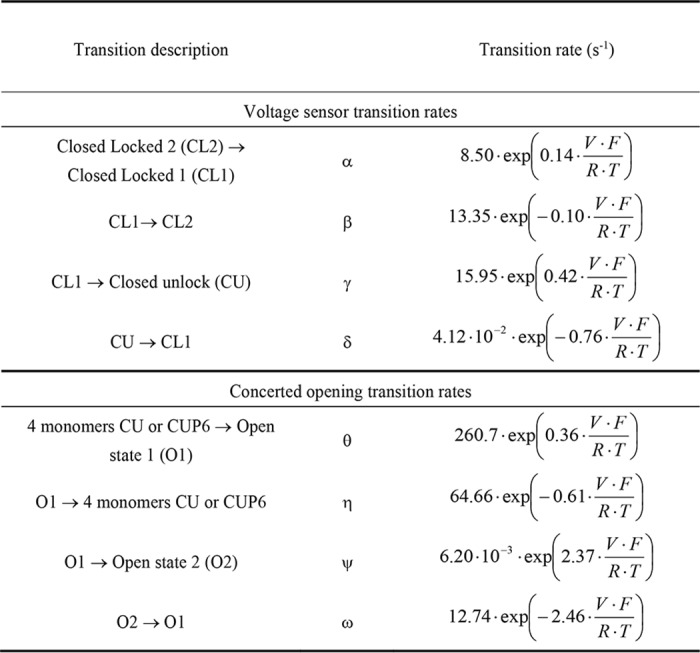

Kinetic model of KV10.2 and its interaction with the S4-S5L peptide. A, kinetic model schemes. This model is based on a previous work on KCNE1-KCNQ1 (23). a, kinetic model in the absence of peptide, on which optimization has been performed (see “Experimental procedures”). Optimized transition rates are presented in Table 1. b, binding of exogenous S4-S5L locks the channel and prevents its opening. Peptides are supposed to interact with each monomer in the unlocked states. B, simulated currents during step protocols (same as in Fig. 5), in the absence (Ctrl) or presence of S4-S5L peptide, at the indicated S4-S5L on/off rates. C, gray filled circles: experimental activation curves and half-activation times in control condition. Other symbols: simulated values in the absence of peptide (control, open circles), or in the presence of peptides, at the indicated rates of peptide binding/unbinding.

As opposed to hERG, N-Cap and PAS domain-deleted KV10.2 channels are not functional

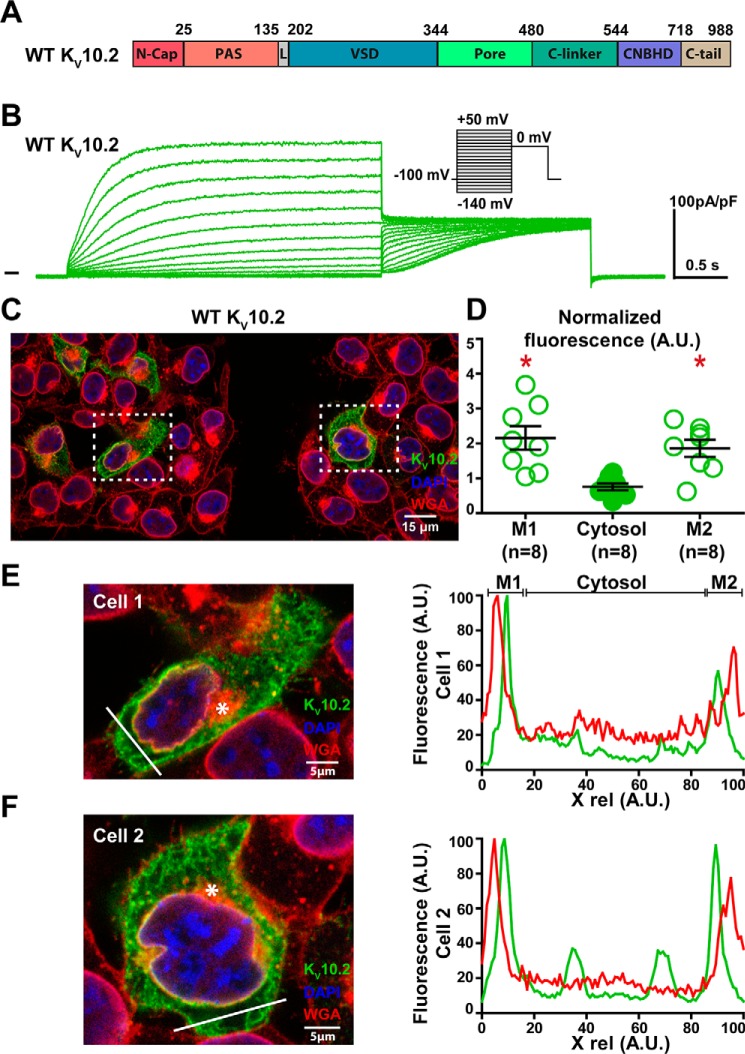

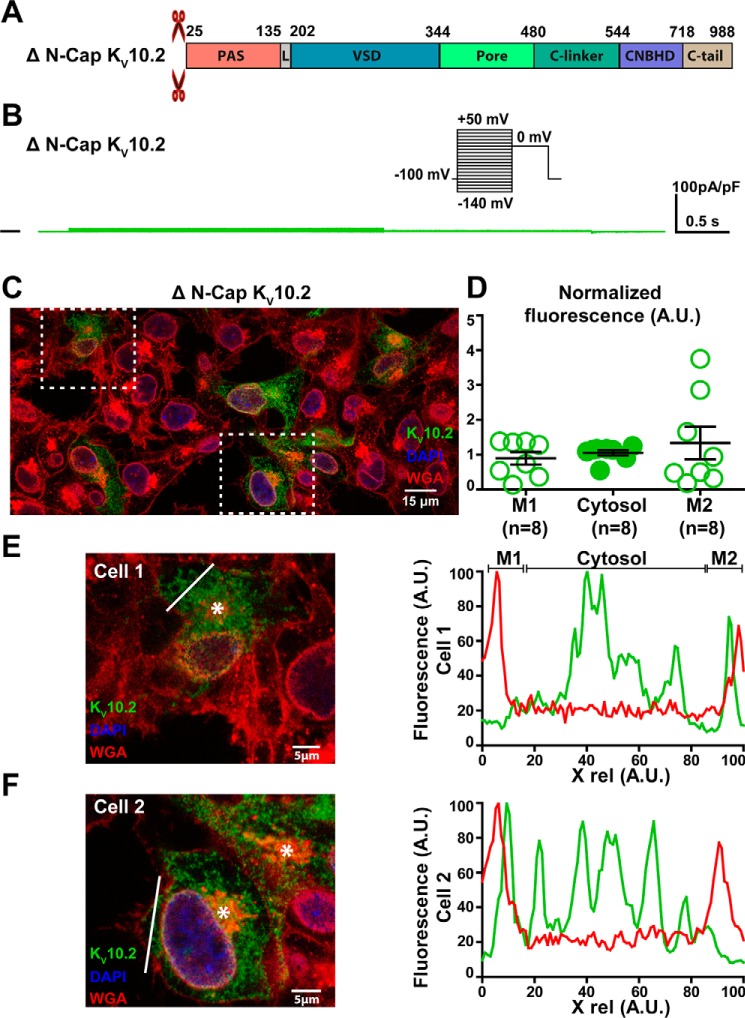

The results described above suggest that in both KV10.2 and hERG channels, deactivation is due to S4-S5L binding to S6T and consequent stabilization of the closed state. It has been shown by several works that intracellular N-cap and PAS domains of hERG (shown in Fig. 7A for KV10.2, cf. alignment in Fig. S3) modulate channel deactivation kinetics. Most importantly truncated hERG channels missing N-Cap or the whole eag domain (N-Cap + PAS), when expressed in Xenopus oocytes, showed robust currents but a more than 5-fold acceleration in deactivation (16–19). Also in mammalian cells, it has been observed that the eag domain is not necessary for hERG channel trafficking, consistent with the observation of robust currents in this model (24, 25). Another work showed that N-Cap is close to S4-S5L (20). Thus, N-Cap may modulate channel deactivation through a direct interaction with this linker. Based on all these observations, we supposed that deletion of both N-Cap and PAS domains in KV10.2 should give rise to functional channels with accelerated deactivation, as in the study on hERG in mammalian cells (25). Transfection of WT KV10.2 tagged with 1D4 at the C terminus gave rise to a current similar to a previous description (6) and immunofluorescence experiments using this tag showed plasma membrane enrichment of the channel, compared with the intracellular compartment (Fig. 7, B–F). Surprisingly, deletion of N-Cap domain, PAS domain, but also of both domains all resulted in nonfunctional KV10.2 channels (Figs. 8B, 9B, and 10B). Immunofluorescence experiments on N-Cap and/or PAS domains truncated channels showed no membrane enrichment of the channels (Figs. 8, C–F, 9, C–F, and 10, C–F). These findings suggest a trafficking defect of the N-Cap and/or PAS domains truncated Kv10.2 channels.

Figure 7.

WT KV10.2 characterization in transfected COS-7 cells. A, domain organization of the channel, showing the eag domain (N-Cap + PAS), a linker domain (L, also named proximal N terminus), the voltage-sensing domain (VSD), the pore domain, C-linker, CNBHD, and C-tail. B, representative, superimposed recordings of the WT KV10.2–1D4 current. Inset: voltage protocol used (one sweep every 8 s). C, representative confocal immunostainings of WT KV10.2–1D4 in transfected COS-7 cells (in green). WGA is used as a membrane marker (in red). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (in blue). Scale bar = 15 μm. D, mean ± S.E. fluorescence of KV10.2 signal in plasma membrane (M1 and M2) and cytosol, as measured in E and F, normalized by the average KV10.2 fluorescence. *, p < 0.05 versus cytosol, paired Student's t test. E and F, left: expanded view of two selected cells, showing the Golgi (stars) and the line used for the line plots shown at the right. Lines have been placed as far as possible from the Golgi to generate accurate plasma membrane plots. Right: line plots of WGA (red) and KV10.2 (green) at the level of the drawn lines at the left. Higher KV10.2 fluorescence densities are observed in the region of the plasma membrane.

Figure 8.

ΔN-Cap KV10.2 characterization in transfected COS-7 cells. A, domains organization of the channel, showing the N-Cap deletion. B, representative, superimposed recordings of the ΔN-Cap KV10.2–1D4 current. Inset: voltage protocol used (one sweep every 8 s). C, representative confocal immunostainings of ΔN-Cap KV10.2–1D4 in transfected COS-7 cells (in green). WGA is used as a membrane marker (in red). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (in blue). Scale bar = 15 μm. D, mean ± S.E. fluorescence of the KV10.2 signal in plasma membrane (M1 and M2) and cytosol, as measured in E and F, normalized by the average KV10.2 fluorescence. E and F, left: expanded view of two selected cells, showing the Golgi (stars) and the line used for the line plots shown on the right. Lines have been placed as far as possible from the Golgi to generate accurate plasma membrane plots. Right: line plots of WGA (red) and KV10.2 (green) at the level of the drawn lines at the left. Higher KV10.2 fluorescence densities are not observed in the region of the plasma membrane, as opposed to the WT condition.

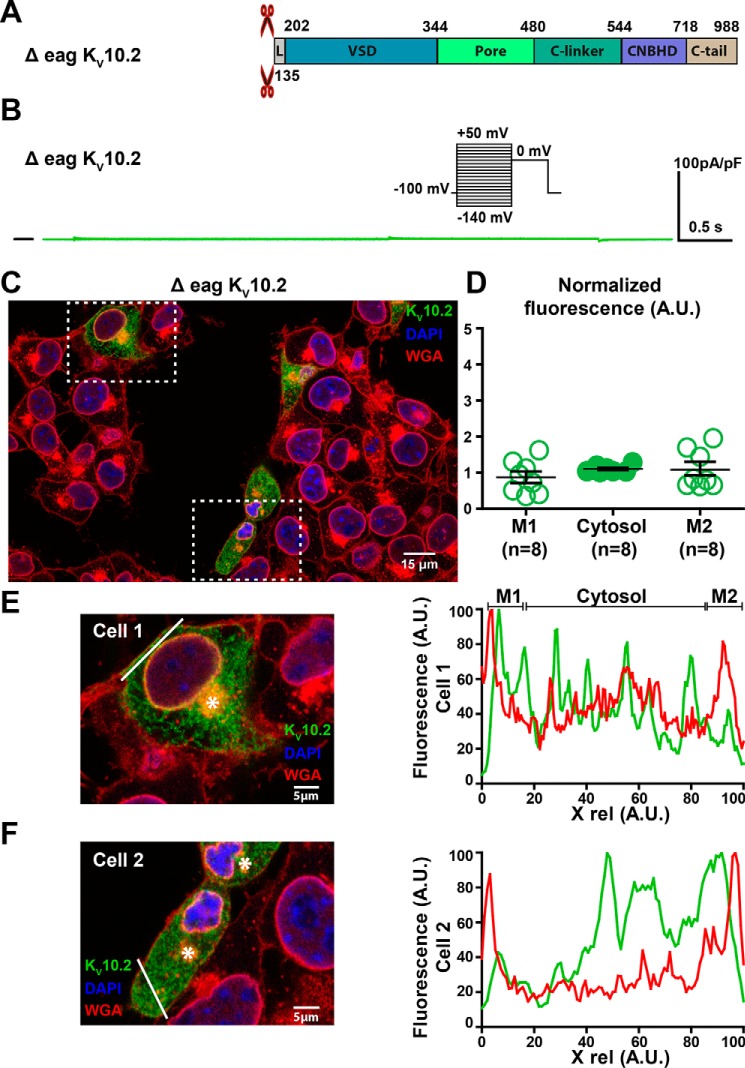

Figure 9.

Δeag KV10.2 characterization in transfected COS-7 cells. A, domains organization of the channel, showing the eag domain deletion. B, representative, superimposed recordings of the Δeag KV10.2–1D4 current. Inset: voltage protocol used (one sweep every 8 s). C, representative confocal immunostainings of Δeag KV10.2–1D4 in transfected COS-7 cells (in green). WGA is used as a membrane marker (in red). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (in blue). Scale bar = 15 μm. D, mean ± S.E. fluorescence of KV10.2 signal in plasma membrane (M1 and M2) and cytosol, as measured in E and F, normalized by the average KV10.2 fluorescence. E and F, left: expanded view of two selected cells, showing the Golgi (stars) and the line used for the line plots shown at the right. Lines have been placed as far as possible from the Golgi to generate accurate plasma membrane plots. Right: line plots of WGA (red) and KV10.2 (green) at the level of the drawn lines at the left. Higher KV10.2 fluorescence densities are not observed in the region of the plasma membrane, as opposed to the WT condition.

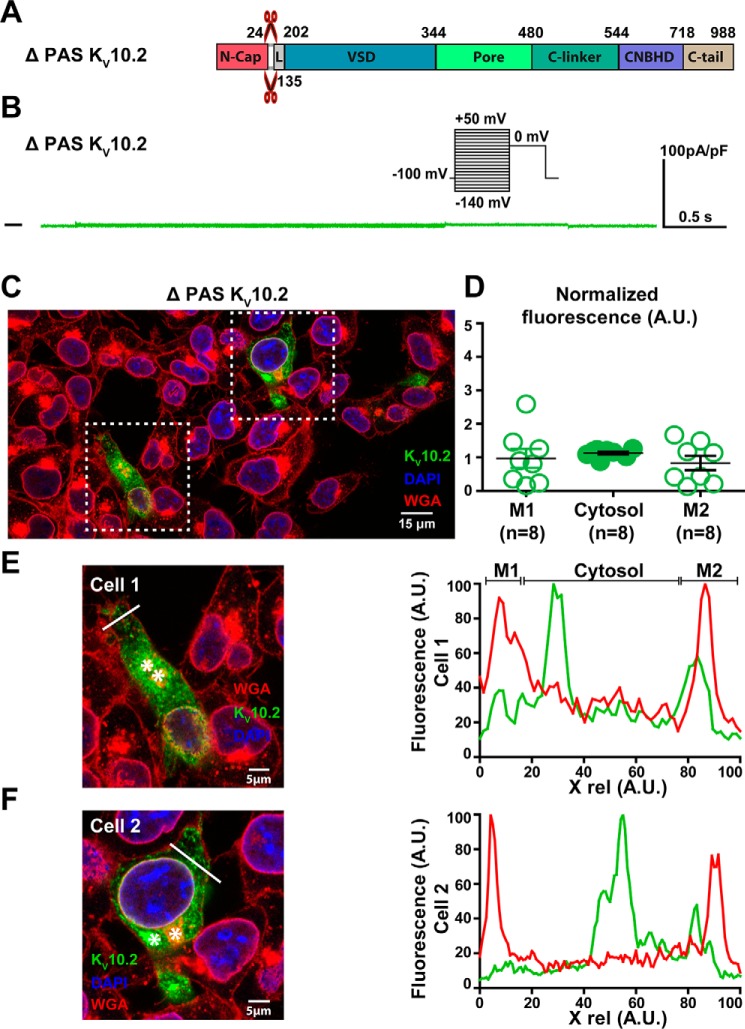

Figure 10.

ΔPAS KV10.2 characterization in transfected COS-7 cells. A, domains organization of the channel, showing the PAS domain deletion. B, representative, superimposed recordings of the ΔPAS KV10.2–1D4 current. Inset: voltage protocol used (one sweep every 8 s). C, representative confocal immunostainings of ΔPAS KV10.2–1D4 in transfected COS-7 cells (in green). WGA is used as a membrane marker (in red). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (in blue). Scale bar = 15 μm. D, mean ± S.E. fluorescence of KV10.2 signal in plasma membrane (M1 and M2) and cytosol, as measured in E and F, normalized by the average KV10.2 fluorescence. E and F, left: expanded view of two selected cells, showing the Golgi (stars) and the line used for the line plots shown at the right. Lines have been placed as far as possible from the Golgi to generate accurate plasma membrane plots. Right: line plots of WGA (red) and KV10.2 (green) at the level of the drawn lines at the left. Higher KV10.2 fluorescence densities are not observed in the region of the plasma membrane, as opposed to the WT condition.

As opposed to hERG, coexpressing a KV10.2 N-Cap mimicking peptide with truncated KV10.2 does not counteract the effect of channel truncation

For the hERG channel, it has been shown that a peptide corresponding to the first 16 amino acids of the channel is sufficient to reconstitute slow deactivation to hERG lacking this region (19). Similarly, another study has shown that injection of the purified eag domain, corresponding to the first 135 amino acids of hERG, into oocytes expressing eag-truncated hERG, restores the deactivation kinetics to WT-like in more than 24 h (17). Based on these previous observations on hERG, we proposed that co-expression of specific KV10.2 N-Cap mimicking peptides with the N-Cap–truncated KV10.2 channel should recover its expression and activity at the plasma membrane. Surprisingly again, KV10.2 channel activity was not recovered in the presence of N-Cap mimicking peptide (n = 8). This observation further suggests that N-Cap and PAS domains play distinct roles in hERG and KV10.2 function.

Co-expression of WT and truncated KV10.2 channels gives rise to a right shift in the activation curve as compared with homomeric WT channels, but no change in deactivation kinetics

To evaluate the potential effects of N-Cap truncation on channel activity, we co-expressed KV10.2 missing the N-Cap with the WT channel, in an attempt to generate heteromers. We observed robust voltage-dependent currents, showing a ∼30-mV shift in the activation curve toward depolarized potential, demonstrating the generation of such heteromers (Fig. 11, C–F). This shift in the activation curve suggests that N-Cap deletion leads not only to a KV10.2 trafficking defect but also to a gating defect. In the hERG channel, deletion of N-Cap did not lead to a shift of the activation curve, but an acceleration of deactivation (26). In the present experiments on KV10.2, no change in deactivation kinetics was observed when the N-Cap–truncated channel was co-expressed with the WT channel (Fig. 12). We also co-expressed the KV10.2 channel construct lacking both the N-Cap and PAS domains, with the WT channel. Again, we observed a ∼30-mV shift in the activation curve toward depolarized potentials, but no modification in deactivation (Figs. 11 and 12). Thus, although we are likely recording the combined activities of tetrameric channels containing different ratios of the WT and truncated subunits, it appears that N-terminal deletion of KV10.2 impacts the steady-state activation curve rather than deactivation kinetics.

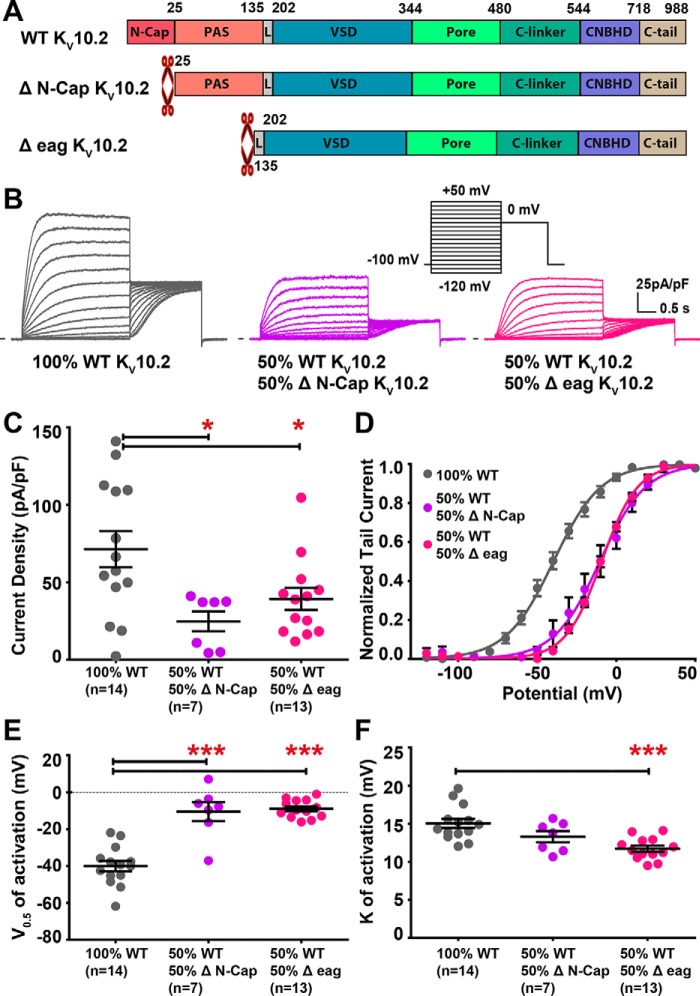

Figure 11.

Co-expression of WT and truncated KV10.2 channels uncovers a right shift in the activation curve, as compared with WT channel. A, domain organization of WT and truncated channels. B, representative, superimposed recordings of COS-7 cells transfected with WT KV10.2 channel (left), WT and ΔN-Cap KV10.2 (middle), and WT and Δeag KV10.2 (right). Inset, activation voltage protocol used (one sweep every 8 s). C, mean ± S.E. KV10.2 maximum tail-current density, in the indicated conditions. *, p < 0.05 versus WT, Mann-Whitney test. D, activation curve in the indicated conditions. E, mean ± S.E. half-activation potential (V0.5). ***, p < 0.001 versus WT, Student's t test. F, mean ± S.E. activation slope (k). ***, p < 0.001 versus WT, Student's t test.

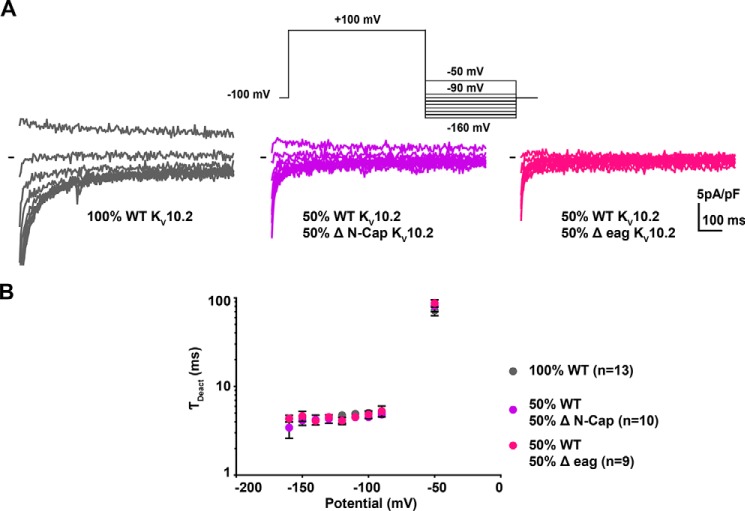

Figure 12.

Co-expression of WT and truncated KV10.2 channels is not associated with changes in deactivation kinetics, as compared with WT channel. A, representative, superimposed recordings of COS-7 cells transfected with WT KV10.2 channel (left), WT and ΔN-Cap KV10.2 (middle), and WT and Δeag KV10.2 (right). Upper inset: deactivation tail voltage protocol used (prepulse duration, 3 s, one sweep every 7 s). B, mean ± S.E. KV10.2 deactivation time constant, obtained from a monoexponential fit of the deactivating current.

Discussion

From the present and previous works, we suggest that among voltage-gated channels, coupling between voltage sensor movement and pore gating falls into two categories: (i) the mechanical-lever model: an obligatory coupling in which the S4 resting state directly translates into S6 gate-closed state. This mechanical-lever model, inferred from structural data in Shaker-like channels (27), also applies to eukaryotic sodium channels, as suggested by recent structural studies (28, 29); (ii) the ligand/receptor model: the obligatory coupling cannot hold if the S6T gate is able to open, even if S4 segments are in the resting state, as shown for hERG and KCNQ1 channels (30–32), and, vice versa, if the S6T gate is able to close, even if S4 segments are in the activated state (33). We recently demonstrated this ligand/receptor model in hERG channels by using several approaches. Here, we obtained similar results on KV10.2 using similar approaches.

First, introduction of cysteines in S4-S5L and S6T lock the channel in a closed state in oxidative conditions, suggesting the formation of a disulfide bridge, as in hERG. This suggests that the same gating mechanism applies to KV10.2. Introduction of cysteines in both S4-S5L and S6T may lead to a nonnative conformation that favor an S4-S5L interaction with S6T, which would not be met in the WT channel. But in the second set of experiments, a S4-S5L mimicking peptide, without any introduced cysteine, inhibits KV10.2 channel, also without any introduced cysteine, further suggesting the capability of S4-S5L to stabilize the channel closed state. Noteworthy, similar channel-specific peptides have the same effect in KCNQ1 and hERG channels (15, 23). Complementary experiments in hERG revealed that S4-S5L peptide effects was on channel gating, and not channel trafficking (15).

Altogether these experiments suggest that KV10.2 follows the ligand/receptor mechanism observed in hERG. In both channels, S4-S5 linkers are short (12, 13), thus it is likely that the part of S5 that is present in the peptide also plays a role in closed channel stabilization. Further structural data of hERG and KV10.2 channels in the closed state should clarify the residues involved in the S4-S5L and S6T interaction. Noteworthy, this ligand/receptor model is consistent with the observation that the voltage-dependent closure of the related KV10.1 channel, but also of the hERG channel, requires at least a part of the inhibiting S4-S5L to be covalently linked to the voltage sensor S4 (34, 35).

As opposed to similar ligand/receptor gating mechanisms in the two channels, the role of the eag domain (N-Cap + PAS) is quite different between hERG and KV10.2. In hERG channels, the eag domain (N-Cap + PAS) is not necessary for channel activity and mainly modulates the current deactivation rate (17–19). Here, we observed that truncation of the KV10.2 eag domain renders the channel nonfunctional, at least partly due to trafficking defects. In rescue experiments with the WT channel, we observed that eag domain deletion or even only N-Cap deletion are associated with a shift in the activation curve, but no change in channel deactivation. The contrary is observed in hERG channel: an altered deactivation, no shift in the activation curve (26, 36). Our results suggest major differences in functional roles for the N-Cap and PAS domains between KV10.2 and hERG. Altogether, this work suggests a conserved ligand/receptor (allosteric) model of voltage gating, but divergent roles in eag domains among channels of the EAG family.

In combination with previous work on hERG, this study highlights the voltage-gated channels superfamily, divergent gating mechanisms (obligatory versus allosteric) that matches divergent structures (swapped versus nonswapped domain, respectively) and divergent kinetics (fast versus slow activating channels, respectively). Nonswapped domains (hERG, KV10) may provide less contact between S4-S5L and S6T (12, 13). We propose that this weak coupling between S4-S5L and S6T provides a framework for a two-step channel activation: first, the fast S4 movement drags the ligand S4-S5L out of its receptor on the S6T gate, followed by slow gate opening. This allosteric regulation of the S6T gate by S4-S5L may explain how in slowly activating channels, movement of S4 is not concomitant to pore opening (37).

Experimental procedures

Plasmid constructs

pCDNA6 hKV10.2 was subcloned into pMT3 vector using the standard PCR overlap extension method (38). A 1D4 immunoaffinity tag (derived from the C terminus of bovine rhodopsin) was added to the C terminus of all constructs (39). The D339C, E343C, M474C, E343C/M474C, and D339C/M474C mutations were inserted into the pMT3-KV10.2 construct using the QuikChangeTM site-directed mutagenesis-based technique using Accuprime Pfx polymerase (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the standard protocol recommended by the manufacturer. Truncation mutants were constructed by deleting residues 2 to 24 (ΔN-CAP), 2 to 134 (Δeag), and 25 to 134 (ΔPAS) using the standard PCR overlap extension method. PCR products were digested with HindIII and XbaI and ligated into pCDNA6 and PMT3 vectors. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Oligonucleotides encoding KV10.2 peptides were synthesized by TOP Gene Technologies and contained a XhoI restriction enzyme, followed by a methionine (ATG) for translation initiation, a glycine (GGA) to protect the ribosome-binding site during translation, and the nascent peptide against proteolytic degradation (40). A BamHI restriction enzyme site was synthesized at the 3′ end immediately following the translational stop codon (TGA). These oligonucleotides were then ligated into pIRES2-EGFP (Clontech) and sequenced.

Cell culture and transfection

The African green monkey kidney-derived cell line COS-7 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (CRL-1651) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics (100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin) at 5% CO2 and 95% air, maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator. Cells were transfected in 35-mm Petri dishes when the culture reached 50–60% confluence, with 4 μg of total DNA complexed with 12 μl of FuGENE-6 (Roche Molecular Biochemical) according to the standard protocol recommended by the manufacturer. In different experiments, plasmid quantities were optimized to keep current amplitudes in a range that undetectable currents were rare, and large currents inducing incorrect voltage-clamp were also rare. Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy experiments were done with pCDNA6-KV10.2 for which channel expression was lower than with pMT3-KV10.2, to limit intracellular accumulation of the protein. For disulfide bridge experiments, COS-7 cells were co-transfected with 3.6 μg of pMT3-WT, D339C/M474C, E343C/M474C, D339C, E343C, M474C KV10.2, and 0.4 μg of pEGFP. For S4-S5L peptide experiments, COS-7 cells were co-transfected with 2 μg of pMT3-WT KV10.2 and 2 μg of pIRES2-EGFP plasmids encoding or not the S4-S5L peptide. As an additional control, a pIRES2-EGFP plasmid encoding a scramble S4-S5L peptide was used. In pIRES2-EGFP plasmids, the second cassette (EGFP) is less expressed than the first cassette, guaranteeing high levels of peptide expression in fluorescent cells (23). For N-terminal deletion experiments, COS-7 cells were co-transfected with 2 μg of pCDNA6-N-Cap truncated KV10.2 and 2 μg of pIRES2-EGFP plasmids encoding or not the N-Cap mimicking peptide. For immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy experiments, COS-7 cells were transfected with 4 μg of pCDNA6-WT/truncated KV10.2. For WT/truncated heteromeric KV10.2 experiments, COS-7 cells were co-transfected with 1.8 μg of pMT3-WT KV10.2, 1.8 μg of pMT3-truncated KV10.2, and 0.4 μg of pEGFP. Cells were re-plated onto 35-mm Petri dishes the day after transfection for patch clamp experiments.

Electrophysiology

One day after splitting, COS-7 cells were mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope and constantly perfused by a Tyrode solution (cf. below) at a rate of 1–3 ml/min. The bath temperature was maintained at 22.0 ± 2.0 °C. Stimulation and data recording were performed with Axon pClamp 10, an A/D converter (Digidata 1440A), and an Axopatch 200B amplifier (all Molecular Devices). Patch pipettes (tip resistance: 2–3 megohms) were pulled from soda lime glass capillaries (Kimble-Chase) and coated with wax. Currents were recorded in the whole-cell configuration, pipette capacitance and series resistance were electronically compensated (by around 75%). Activation protocols were adjusted to the voltage-dependence of the construct as in the previous study on hERG (15). Activation curves were obtained from the tail currents and fitted by Boltzmann equations.

Confocal microscopy

Immunohistological analyses were performed to study cell localization of transfected WT/truncated KV10.2–1D4 in COS-7 cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were plated on IBIDI plates for 24 h. Cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde, stained for 10 min at room temperature with Alexa FluorTM 647 conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; ThermoFisher), a plasma membrane marker, permeabilized with 0.5% saponin and blocked with 1% PBS/BSA. Cells were then incubated with a mouse mAb directed against the 1D4 tag diluted in PBS (Abcam). Secondary antibody staining was performed using Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse antibody. DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Conventional imaging was performed using a LSM710-Confocor3 (Zeiss) and a Nikon Confocal A1RSi microscope system equipped with a SR Apo 100 × 1.49 N.A objective. Images were analyzed with ImageJ software. In figures, but not for analyses, Enhance Local Contrast adjustment was performed on WGA staining to highlight plasma membrane staining. To quantify fluorescence, the line plot was arbitrarily segmented in 3 different regions: the first and last 5–15% of the line plot, corresponding to plasma membrane (M1 and M2), and the remaining intermediate 70% of the line plot, corresponding to the intracellular compartment. For each of these regions in each cell, KV10.2 fluorescence intensity values were normalized by the average cell KV10.2 fluorescence intensity signal (41).

Solutions

Cells were continuously superfused with a HEPES-buffered Tyrode solution containing (in mmol/liter): NaCl 145, KCl 4, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 1, HEPES 5, glucose 5, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Patch pipettes were filled with the following solution (in mmol/liter): KCl 100, K-gluconate 45, MgCl2 1, EGTA 5, HEPES 10, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. For experiments in Fig. 3, 1 mm K2ATP was added to limit current rundown. The membrane-permeable oxidizing agent tbHO2 was obtained from Sigma. Incubation of COS-7 cells with 0.2 or 2 mm tbHO2 was realized at room temperature.

Kinetic model

The KV10.2 kinetic model (Fig. 6A, top) contains two voltage sensor transitions, and two open states, as in the model of IKs (42). This model was optimized using IChMASCOT (J.A. De Santiago-Castillo and M. Covarrubias) to fit traces of the representative control of Fig. 5. Optimized transition rates are presented in Table 1. Next, another model was designed (Fig. 6A, bottom), with an additional state in which S4-S5L mimicking peptide binds to the pre-open state and stabilizes it, as in Ref. 23. Various S4-S5L binding/unbinding transition rates were applied, and the effects on the biophysical parameters were studied.

Table 1.

Optimized transition rates used in the model presented in Fig. 6

The abbreviations use are: F = 96485 C. mol−1 (Faraday constant); R = 8.314 J. mol−1.K−1 (gas constant); T = 297 K; V (membrane potential) in V.

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± S.E. Statistical differences between current densities (data points are not normally distributed) were determined using nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Statistical differences between activation parameters, V0.5, K (data points are normally distributed) were determined using unpaired Student's t tests. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Author contributions

O. A. M., O. S. S., and G. L. data curation; O. A. M., G. S. G., A. V. G., and K. S. K. formal analysis; O. A. M., O. S. S., and G. L. validation; O. A. M., G. S. G., A. V. G., K. S. K., O. S. S., and G. L. investigation; O. A. M., G. S. G., A. V. G., K. S. K., O. S. S., and G. L. methodology; O. A. M., O. S. S., and G. L. writing-original draft; O. A. M., O. S. S., and G. L. writing-review and editing; O. S. S. and G. L. conceptualization; O. S. S. and G. L. supervision; O. S. S. and G. L. funding acquisition; O. S. S. and G. L. project administration; G. L. resources.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Isabelle Baró for careful reading of the manuscript. We thank the MicroPiCell facility of SFR Santé F. Bonamy for confocal microscopy experiments (Nantes). O. A. M. personally thanks Line Pomaret for her generous support. The LSM710-Confocor3 microscope was supported by the Moscow Lomonosov State University Program of Development.

This work was supported by Kolmogorov program of the Partenariat Hubert Curien Grant 35503SC (to G. L. and O. A. M.), Ministry of Education and Science of Russian Federation Grant RFMEFI61615X0044 (to O. S. S. and G. S. G.), a Fondation Genavie (to O. A. M.), Postdoctoral Fellowship 1.50.1038.2014 from St. Petersburg State University and a grant from the Dynasty Foundation (to A. G.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S3.

- EAG

- ether-a-go-go

- PAS

- Per-Arnt-Sim

- WGA

- wheat germ agglutinin

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- tbHO2

- tert-butylhydroperoxide

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein.

References

- 1. Yellen G. (2002) The voltage-gated potassium channels and their relatives. Nature 419, 35–42 10.1038/nature00978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Charpentier F., Mérot J., Loussouarn G., and Baró I. (2010) Delayed rectifier K+ currents and cardiac repolarization. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 48, 37–44 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pal S., Hartnett K. A., Nerbonne J. M., Levitan E. S., and Aizenman E. (2003) Mediation of neuronal apoptosis by Kv2.1-encoded potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 23, 4798–4802 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04798.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jiménez-Perez L., Cidad P., Álvarez-Miguel I., Santos-Hipólito A., Torres-Merino R., Alonso E., de la Fuente M. Á., López-López J. R., and Pérez-García M. T. (2016) Molecular determinants of Kv1.3 potassium channels-induced proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 3569–3580 10.1074/jbc.M115.678995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Piron J., Choveau F. S., Amarouch M. Y., Rodriguez N., Charpentier F., Mérot J., Baró I., and Loussouarn G. (2010) KCNE1-KCNQ1 osmoregulation by interaction of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate with Mg2+ and polyamines. J. Physiol. 588, 3471–3483 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang Y., Vasylyev D. V., Dib-Hajj F., Veeramah K. R., Hammer M. F., Dib-Hajj S. D., and Waxman S. G. (2013) Multistate structural modeling and voltage-clamp analysis of epilepsy/autism mutation Kv10.2-R327H demonstrate the role of this residue in stabilizing the channel closed state. J. Neurosci. 33, 16586–16593 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2307-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Watanabe H., Nagata E., Kosakai A., Nakamura M., Yokoyama M., Tanaka K., and Sasai H. (2000) Disruption of the epilepsy KCNQ2 gene results in neural hyperexcitability. J. Neurochem. 75, 28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Judge S. I., and Bever C. T. Jr. (2006) Potassium channel blockers in multiple sclerosis: neuronal Kv channels and effects of symptomatic treatment. Pharmacol. Ther. 111, 224–259 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beekwilder J. P., O'Leary M. E., van den Broek L. P., van Kempen G. T., Ypey D. L., and van den Berg R. J. (2003) Kv1.1 channels of dorsal root ganglion neurons are inhibited by n-butyl-p-aminobenzoate, a promising anesthetic for the treatment of chronic pain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 304, 531–538 10.1124/jpet.102.042135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pardo L. A., and Stuhmer W. (2014) The roles of K+ channels in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 39–48 10.1038/nrc3635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ju M., and Wray D. (2002) Molecular identification and characterisation of the human eag2 potassium channel. FEBS Lett. 524, 204–210 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03055-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whicher J. R., and MacKinnon R. (2016) Structure of the voltage-gated K+ channel Eag1 reveals an alternative voltage sensing mechanism. Science 353, 664–669 10.1126/science.aaf8070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang W., and MacKinnon R. (2017) Cryo-EM structure of the open human ether-a-go-go-related K+ channel hERG. Cell 169, 422–430 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferrer T., Rupp J., Piper D. R., and Tristani-Firouzi M. (2006) The S4-S5 linker directly couples voltage sensor movement to the activation gate in the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) K+ channel. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12858–12864 10.1074/jbc.M513518200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malak O. A., Es-Salah-Lamoureux Z., and Loussouarn G. (2017) hERG S4-S5 linker acts as a voltage-dependent ligand that binds to the activation gate and locks it in a closed state. Sci. Rep. 7, 113 10.1038/s41598-017-00155-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de la Peña P., Machin A., Fernández-Trillo J., Domínguez P., and Barros F. (2013) Mapping of interactions between the N- and C-termini and the channel core in HERG K+ channels. Biochem. J. 451, 463–474 10.1042/BJ20121717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morais Cabral J. H., Lee A., Cohen S. L., Chait B. T., Li M., and Mackinnon R. (1998) Crystal structure and functional analysis of the HERG potassium channel N terminus: a eukaryotic PAS domain. Cell 95, 649–655 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81635-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang J., Trudeau M. C., Zappia A. M., and Robertson G. A. (1998) Regulation of deactivation by an amino terminal domain in human ether-a-go-go-related gene potassium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 112, 637–647 10.1085/jgp.112.5.637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang J., Myers C. D., and Robertson G. A. (2000) Dynamic control of deactivation gating by a soluble amino-terminal domain in HERG K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 115, 749–758 10.1085/jgp.115.6.749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de la Peña P., Alonso-Ron C., Machín A., Fernández-Trillo J., Carretero L., Domínguez P., and Barros F. (2011) Demonstration of physical proximity between the N terminus and the S4-S5 linker of the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 19065–19075 10.1074/jbc.M111.238899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barros F., Pardo L. A., Dominguez P., Sierra L. M., and de la Pena P. (2019) New structures and gating of voltage-dependent potassium (Kv) channels and their relatives: a multi-domain and dynamic question. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 248 10.3390/ijms20020248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tristani-Firouzi M., Chen J., and Sanguinetti M. C. (2002) Interactions between S4-S5 linker and S6 transmembrane domain modulate gating of HERG K+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18994–19000 10.1074/jbc.M200410200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choveau F. S., Rodriguez N., Abderemane Ali F., Labro A. J., Rose T., Dahimène S., Boudin H., Le Hènaff C., Escande D., Snyders D. J., Charpentier F., Mérot J., Baró I., and Loussouarn G. (2011) KCNQ1 channels voltage dependence through a voltage-dependent binding of the S4-S5 linker to the pore domain. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 707–716 10.1074/jbc.M110.146324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ke Y., Hunter M. J., Ng C. A., Perry M. D., and Vandenberg J. I. (2014) Role of the cytoplasmic N-terminal Cap and Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain in trafficking and stabilization of Kv11.1 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 13782–13791 10.1074/jbc.M113.531277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fernández-Trillo J., Barros F., Machín A., Carretero L., Domínguez P., and de la Peña P. (2011) Molecular determinants of interactions between the N-terminal domain and the transmembrane core that modulate hERG K+ channel gating. PLoS One 6, e24674 10.1371/journal.pone.0024674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ng C. A., Hunter M. J., Perry M. D., Mobli M., Ke Y., Kuchel P. W., King G. F., Stock D., and Vandenberg J. I. (2011) The N-terminal tail of hERG contains an amphipathic α-helix that regulates channel deactivation. PLoS One 6, e16191 10.1371/journal.pone.0016191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Long S. B., Campbell E. B., and Mackinnon R. (2005) Voltage sensor of Kv1.2: structural basis of electromechanical coupling. Science 309, 903–908 10.1126/science.1116270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shen H., Zhou Q., Pan X., Li Z., Wu J., and Yan N. (2017) Structure of a eukaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel at near-atomic resolution. Science 355, eaal4326 10.1126/science.aal4326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yan Z., Zhou Q., Wang L., Wu J., Zhao Y., Huang G., Peng W., Shen H., Lei J., and Yan N. (2017) Structure of the Nav1.4-β1 complex from electric eel. Cell 170, 470–482.e11 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ma L. J., Ohmert I., and Vardanyan V. (2011) Allosteric features of KCNQ1 gating revealed by alanine scanning mutagenesis. Biophys. J. 100, 885–894 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Osteen J. D., Barro-Soria R., Robey S., Sampson K. J., Kass R. S., and Larsson H. P. (2012) Allosteric gating mechanism underlies the flexible gating of KCNQ1 potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7103–7108 10.1073/pnas.1201582109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vardanyan V., and Pongs O. (2012) Coupling of voltage-sensors to the channel pore: a comparative view. Front. Pharmacol. 3, 145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun J., and MacKinnon R. (2017) Cryo-EM structure of a KCNQ1/CaM complex reveals insights into congenital long QT syndrome. Cell 169, 1042–1050.e9 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tomczak A. P., Fernández-Trillo J., Bharill S., Papp F., Panyi G., Stühmer W., Isacoff E. Y., and Pardo L. A. (2017) A new mechanism of voltage-dependent gating exposed by KV10.1 channels interrupted between voltage sensor and pore. J. Gen. Physiol. 149, 577–593 10.1085/jgp.201611742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. de la Pena P., Domínguez P., and Barros F. (2018) Gating mechanism of Kv11.1 (hERG) K(+) channels without covalent connection between voltage sensor and pore domains. Pflugers Arch. 470, 517–536 10.1007/s00424-017-2093-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sale H., Wang J., O'Hara T. J., Tester D. J., Phartiyal P., He J. Q., Rudy Y., Ackerman M. J., and Robertson G. A. (2008) Physiological properties of hERG 1a/1b heteromeric currents and a hERG 1b-specific mutation associated with Long-QT syndrome. Circ. Res. 103, e81–e95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goodchild S. J., and Fedida D. (2014) Gating charge movement precedes ionic current activation in hERG channels. Channels (Austin) 8, 84–89 10.4161/chan.26775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Horton R. M., Cai Z., Ho S. M., and Pease L. R. (2013) Gene splicing by overlap extension: tailor-made genes using the polymerase chain reaction. BioTechniques 54, 129–133 10.2144/000114017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sokolova O. S., Sha-breve]itan K. V., Grizel′ A. V., Popinako A. V., Karlova M. G., and Kirpichnikov M. P. (2012) Three-dimensional structure of human Kv10.2 ion channel studied by single particle electron microscopy and molecular modeling. Bioorg. Khim. 38, 177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gilchrist A., Li A., and Hamm H. E. (2002) Gα COOH-terminal minigene vectors dissect heterotrimeric G protein signaling. Sci. STKE 2002, pl1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jouni M., Si-Tayeb K., Es-Salah-Lamoureux Z., Latypova X., Champon B., Caillaud A., Rungoat A., Charpentier F., Loussouarn G., Baró I., Zibara K., Lemarchand P., and Gaborit N. (2015) Toward personalized medicine: using cardiomyocytes differentiated from urine-derived pluripotent stem cells to recapitulate electrophysiological characteristics of type 2 long QT syndrome. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 4, e002159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Silva J., and Rudy Y. (2005) Subunit interaction determines IKs participation in cardiac repolarization and repolarization reserve. Circulation 112, 1384–1391 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Papadopoulos J. S., and Agarwala R. (2007) COBALT: constraint-based alignment tool for multiple protein sequences. Bioinformatics 23, 1073–1079 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thouta S., Sokolov S., Abe Y., Clark S. J., Cheng Y. M., and Claydon T. W. (2014) Proline scan of the HERG channel S6 helix reveals the location of the intracellular pore gate. Biophys. J. 106, 1057–1069 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.