ABSTRACT

Background: Over the past 20 years, hospitalists have assumed a greater portion of healthcare service for hospitalized patients. This was mainly due to reducing the length of stay (LOS) and hospital costs shown by many studies. In contrast, other studies suggested increased cost and resources utilization associated with hospitalist-run care models.

Aim: We aimed to provide class 1 evidence regarding the effect of hospitalist-run care models on the efficiency of care and patient satisfaction.

Design: Meta-analysis.

Methods: Four electronic medical databases were searched to retrieve all relevant studies. Two authors screened titles and abstracts of search results for eligibility according to predefined criteria. Initially eligible studies were screened for full text inclusion. Included studies were reviewed for data on LOS, hospital cost, readmission, mortality, and patient satisfaction. Available data were abstracted and analyzed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis.

Results: Sixty-one studies were included for analysis. The overall effect size favored hospitalist-run care models in terms of LOS (MD = −0.67 day, 95% CI [−0.78, −0.56], p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in terms of hospital cost (MD = $92.1, 95% CI [−910.4, 1094.6], p = 0.86) whereas patient satisfaction was similar or even better in hospitalist compared to non-hospitalist (NH) service.

Conclusion: Our analysis showed that hospitalist care is associated with decreased LOS and increased patient satisfaction compared to NH. This indicates an increase in the efficiency of care that does not come at the expense of care quality.

KEYWORDS: Hospital medicine, hospitalists, inpatient care, quality of life

1. Introduction

Hospital medicine is one of the fastest growing medical specialties in the USA [1,2]. A major cause of this growth has been empirical evidence that hospitalists provide more efficient, less costly inpatient care with equal or higher quality [3]. Several studies have investigated the impact of hospitalists on the efficiency and quality of patients’ care. Results from these studies have been conflicting; with many of them suggesting shorter hospital stay and reduced cost for patients cared for by hospitalists [3–9]. However, other investigators failed to recognize significant advantages from implementing hospitalist care models compared to traditional care by non-hospitalists (NH) [10,11].

Given the non-conclusive results from different hospitalist programs in various clinical settings regarding the effect of hospitalist-based care model on the length of stay (LOS) and hospital costs, Rachoin et al. published a meta-analysis in 2012 to summarize the conflicting evidence [12]. However, they used a limited search strategy that was restricted to only one database so it is possible that potentially eligible articles might be missed. Authors reported data for LOS and hospital costs only. To further, several studies that compared hospitalist and NH care models have been published thereafter [13–16] adding more to the farrago of existing literature.

This prompted us to a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to generate clear-cut evidence regarding the impact of hospitalists on LOS, costs, in-hospital mortality, readmission within 30 days, and patient satisfaction.

2. Experimental section

We followed the recommendation of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement [17] during the preparation of this manuscript (Supplementary file 1). Moreover, all steps were done according to Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews of interventions [18].

2.1. Data sources and searches

We searched Medline via PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials (CENTRAL), Scopus, and ISI web of knowledge. A combination of these keywords was tailored for each database: (‘hospitalists’ OR ‘hospitalist system’ OR ‘non-hospitalists’) AND (‘length of hospital stay’ OR ‘length of stay’ OR ‘cost’ OR ‘Hospital Costs’ OR ‘economics’ OR ‘outcomes’ OR ‘outcome’ OR ‘mortality’ OR ‘death’ OR ‘readmission’ OR ‘satisfaction’). Results were imported to the reference manager Endnote X7 for screening.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they used experimental (randomized clinical trial) or observational, retrospective or follow-up designs that compared hospitalists to non-hospitalists in terms of LOS, costs, in-hospital mortality, readmission within 30 days, or patient satisfaction. Pre-post designs were also included. We excluded review articles, editorials, case series and case reports. The corresponding authors of studies that did not report enough data were contacted for providing the missing data. Otherwise, studies with no sufficient data for meta-analysis were included for narrative review.

2.3. Study selection

Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles against our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Initially eligible articles were considered for a second round of full-text screening. Conflicts were resolved by consensus and discussion with a third senior reviewer.

2.4. Data extraction

Data were extracted to a standard excel sheet that was designed specifically for this study. The following data were extracted from each study whenever available: (1) Demographics and baseline characteristics of the study’s participants; (2) Summary of the study design, setting, year, timeline, and type of the hospitalist and comparison groups; (3) the studied outcomes including LOS, hospital costs, mortality or readmission, and patients’ satisfaction. We extracted mean and standard deviation (SD) [or median, range/inter quartile range (IQR) or median and confidence interval (CI)] and number per group for numerical data, whereas number of events and total number of participants were extracted for dichotomous and categorical variables. Data were abstracted and reviewed twice for integrity and validity.

2.5. Data synthesis and analysis

Numerical data were pooled as mean and CI, and dichotomous data were pooled as odds ratio (OR) and CI. Whenever median and range/IQR were reported, we used equations of Cochrane handbook and Wan et al. [19] to get the approximate mean and SD. Due to substantial variation in studies design and setting, the Der-Simonian random effects model was adopted for all analyses. We performed sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of omitting single studies on the overall effect size. Also, cumulative meta-analysis was conducted to display the trend of LOS and cost over time. Our study was eligible for such analysis due to the high number of included studies that allows for clear display of trends. This analysis helps direct health care policy makers by showing how hospitalists’ efficiency rise or decline over time. Breakpoints were selected when there was a major change in the mean difference between the hospitalist and non-hospitalist group (shift from significant difference to no difference or vice versa). Heterogeneity was quantified and assessed using the I-square test and publication bias was explored according to Egger’s regression test. P value< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Search results and characteristics of the included studies

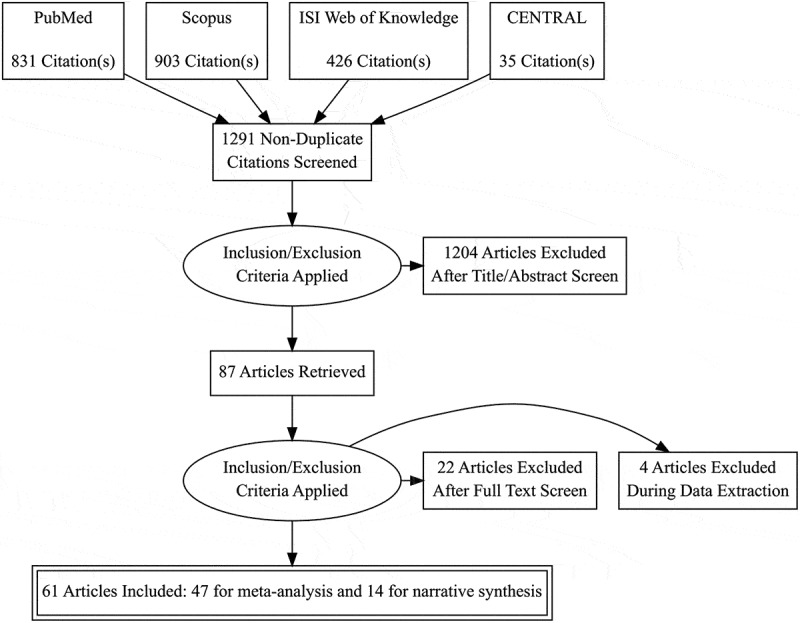

Database searching retrieved 2,195 results that were abstracted to 1,291 unique records after automatic duplicate removal by Endnote software. Titles and abstracts were reviewed against our eligibility criteria, and 87 articles were found initially eligible for our review. Further screening of the full-text articles resulted in 61 finally included studies [3–8,10,11,13–16,20–68]; of them 47 were eligible for meta-analysis and 14 articles were narratively summarized (Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram). Twenty-six studies were rejected during full text screening because they did not meet our eligibility criteria; 12 were single arm studies, 3 were expert opinions, 7 editorials, and 4 were book chapters. Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Summary of the included studies.

| Author | Year | Setting | Patients | Timeline | Comparison Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hackner | 2000 | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles (A university-affiliated, community medical center) |

Patients from the emergency department and from private offices or from the hospital clinic population who were admitted directly to the hospital wards | 12 months | Variety of private practitioners |

| Auerbach | 2002 | Mount Zion Hospital, a 280-bed community-based teaching hospital affiliated with University of California, San Francisco |

Patients 18 years of age or older | 24 months | Community-based physicians |

| Aplin | 2014 | Urban, academic, 600-bed teaching hospital in Camden, New Jersey |

Patients discharged from medical– surgical units. |

24 months | Medical-surgical |

| Burke | 2013 | Denver VA Medical Center | General inpatients | 7 years | Urgent care physician |

| Chadaga | 2012 | Academic hospital in Denver, Colorado | General inpatients | NA | Hospitalists |

| Chavey | 2014 | US teaching hospitals | Adult non-pregnancy-related inpatients | 9 years | Family physician |

| Chin | 2014 | Academic medical center | Internal medicine patients | 4 years | Academic preceptors |

| Ding | 2014 | General internal medicine department of an Acute-care hospital in Singapore |

Seniors aged 80 years and older with specific Focus on 2 subgroups with premorbid functional impairment and acute geriatric syndromes |

3 years | Other internists |

| Douglas | 2012 | Tertiary care academic medical center. | Neurologic inpatients | 48 months | Neuro-hospitalist |

| Shu | 2011 | National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH), a Tertiary-care referral center in northern Taiwan |

General inpatients | 2 months | Internist |

| Duplantier | 2016 | Single teaching institution | Joint Arthroplasty Patients | 4 years | Non-hospitalist |

| Desai | 2014 | University of Chicago Medical Center |

Chronic Liver Disease | 6 years | Conventional |

| Everett [1] | 2011 | Large, urban, Not-for-profit community teaching hospital in Florida. |

Cardiovascular diseases | 5 years | Cardiologist |

| Everett [2] | 2011 | Large, urban, Not-for-profit community teaching hospital in Florida. |

Cardiovascular diseases | 5 years | Internist |

| Fulton | 2011 | NA | General inpatients | NA | Non-hospitalist |

| Goldie | 2012 | Tertiary care hospital | Coronary artery bypass/valvular surgery | 9 months | ACNPs |

| Gonzalo | 2015 | Penn State Hershey Medical Center, central Pennsylvania. |

Internal medicine patients | 3 years | Pre-hospitalist |

| Lee | 2011 | Singapore General Hospital. | General inpatients. | 1 year | Specialists-based model |

| Hollier | 2015 | Tertiary Pediatric inpatient hospital in San Francisco, California. |

RSWS (Asthma, cellulitis inpatients) HMS/RSWS (IBD, DKA patients) |

2 years | RSWS |

| Howrey | 2011 | 5% Medicare sample USA | Stroke | 4 years | Non-hospitalist care |

| Huddleston | 2004 | Academic medical center. | Orthopedic | NA | Standard orthopedic |

| Iannuzzi | 2015 | Health institution. | Internal medicine inpatients. | 3 years | Midlevel practitioner |

| Iberti | 2016 | Urban tertiary care hospital in New York City. |

Vascular surgery | 2 years | Hospitalists |

| Kociol | 2013 | Data from the Get With the Guidelines-Heart Failure registry | Heart failure inpatients. | 3 years | Low hospitalist use |

| Koo | 2015 | a tertiary cancer center in New York | Oncology unit patients | 5 months | Oncologist–led |

| Kuo | 2011 | Hospital care of Medicare patients | General inpatients | 5 years | PCP |

| Okere | 2016 | Two medical units of a community Teaching hospital. |

General inpatients | 14 months | Post-PHC model |

| Singh | 2011 | Urban Academic medical center in the Midwestern USA |

General inpatients | 12 months | Traditional Resident-Based Model |

| Tadros | 2015 | Urban tertiary care hospital and medical school, Metropolitan New York |

High-risk surgical Patients. |

12 months | Vascular surgeons |

| Tadros | 2016 | Urban tertiary care hospital and medical school, Metropolitan New York |

High-risk surgical patients. |

10 months | Vascular surgeons |

| Wise | 2011 | Urban academic community hospital affiliated with a major regional academic university. |

Medical ICU patients | 12 months | Intensivist-led team. |

| Diamond | 1998 | CTH, Northeast US | General inpatients | 12 months | PCP |

| Craig | 1999 | Kaiser Permanente, CA | General inpatients | 36 months | Internist |

| Davis | 2000 | Tertiary care center, Rural health care system, MI |

General inpatients | 12 months | Internist |

| Rifkin | 2002 | Tertiary care center, NY | CAP | 12 months | PCP |

| Tingle | 2001 | CTH, TX | General inpatients | 15 months | FMT |

| Meltzer | 2002 | Academic center, Chicago | General inpatients | 24 months | NH |

| Scheurer | 2005 | All SC hospitals | Pneumonia | 12 months | NH |

| Phy | 2005 | Academic medical center, MN | Hip fracture | 24 months | NH |

| Rifkin | 2007 | CTH | Pneumonia | 5 months | NH |

| Southern | 2007 | Teaching hospital, NY | General inpatients | 24 months | NH |

| Lindenauer | 2007 | 45 Hospitals across US | General inpatients | 33 months | NH |

| Carek | 2008 | CTH | General inpatients | 12 months | 1. Private 2. FMT |

| Vasilevskis | 2008 | 6 Academic medical centers | CHF | 24 months | NH teaching |

| Roy | 2008 | CTH, FL | General inpatients | 12 months | NH teaching |

| Dynan | 2009 | Academic medical center, OH | General inpatients | 12 months | NH teaching |

| Go | 2010 | 6 Academic medical centers GI bleed |

NA | 24 months | NH |

Note: CAP: community-acquired pneumonia; CHF: congestive heart failure; CTH: Community Teaching Hospital; FMT: family medicine teaching; GI: gastrointestinal; LOS: length of stay; NH: non-hospitalist; PCP: primary care physician; RSWS: resident shift work schedule; HMS: hospitalist-led model system; ACNPs: Acute Care Nurse Practitioners.

3.2. Outcomes

3.2.1. Hospital length of stay (LOS)

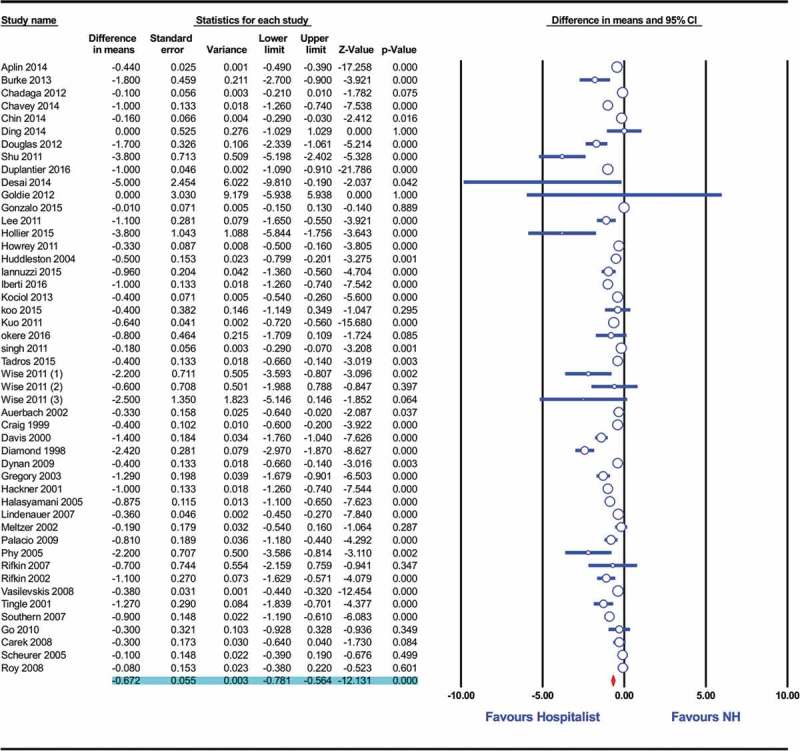

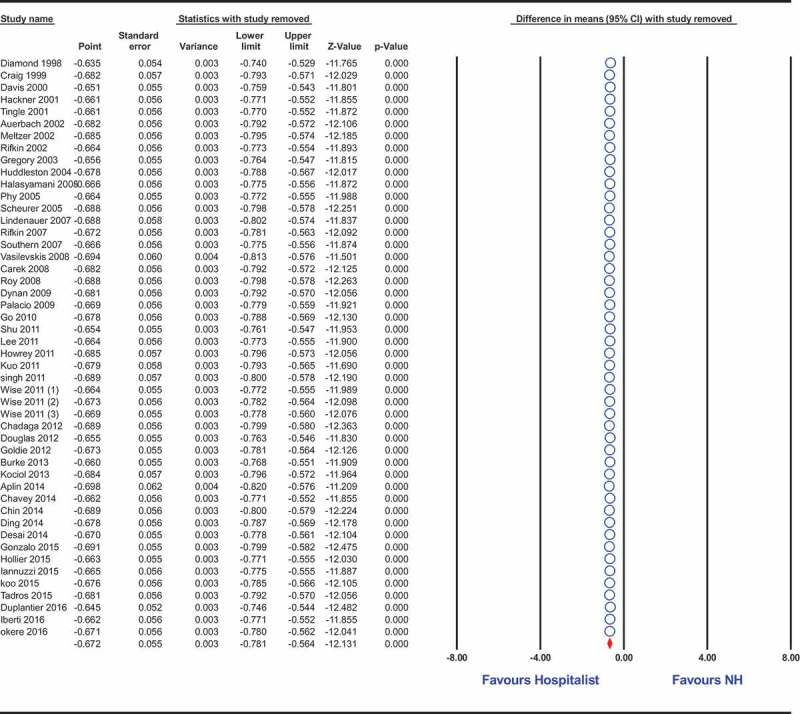

Data of hospital LOS in the hospitalist and NH groups were provided by 46 studies that enrolled 563,268 patients. Significant heterogeneity was identified among these studies (I2 = 92%, p < 0.001), hence the random effects model was employed. Overall mean difference favored the hospitalist versus non-hospitalist healthcare models in terms of LOS (MD = −0.67 day, 95% CI [−0.78, −0.56], p < 0.001); Figure 2. This effect size persisted on a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis that was performed to explore the effect of single studies on the overall effect estimate (Figure A1).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of LOS in hospitalist- and non-hospitalist-based care models.

Figure A1.

Forest plot of sensitivity analysis of LOS in Hospitalist- and Non-hospitalist-based care models.

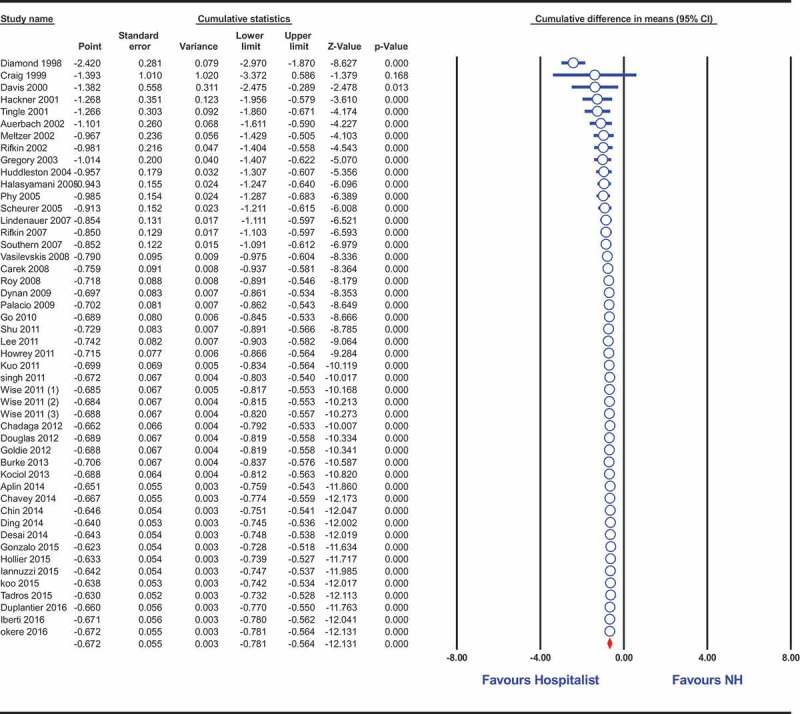

Interestingly, cumulative meta-analysis showed decreasing trend of the MD in LOS between the hospitalist and NH groups. From 1998 to 2003, there was a cumulative MD of 2.4 days to 1 day that declined to less than 1 day (0.95 to 0.67) afterwards (Figure A2). Egger’s regression test showed evidence of publication bias towards studies that favored the hospitalist group (p = 0.01).

Figure A2.

Forest plot of cumulative LOS in Hospitalist- and Non-hospitalist-based care models.

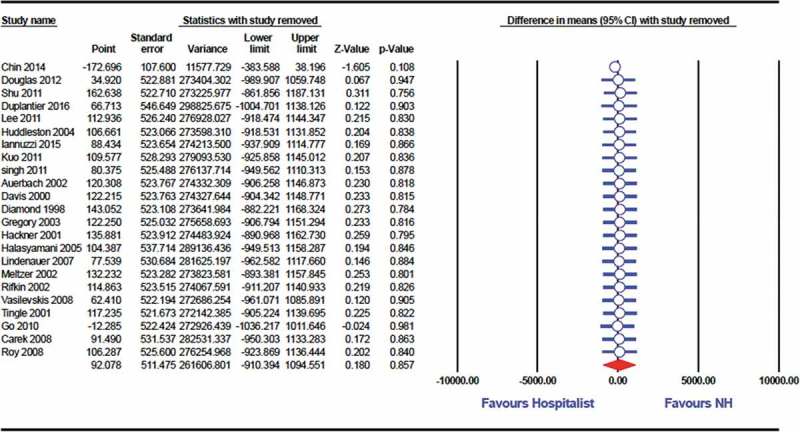

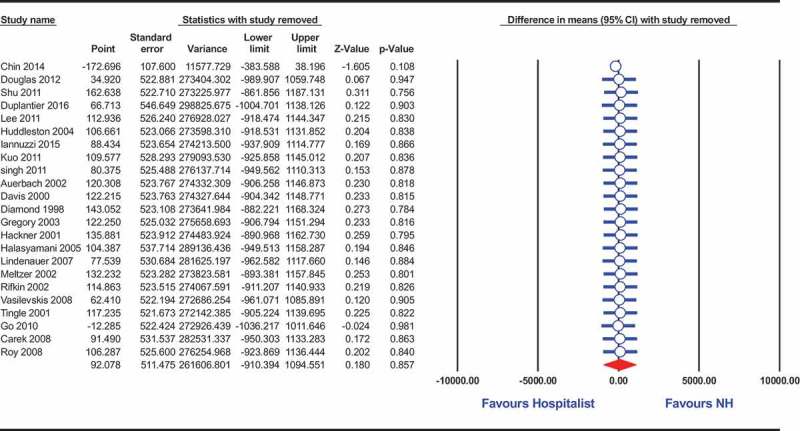

3.2.2. Costs

Twenty-four studies (227,372 participants) reported data on the hospital costs for hospitalist- and NH-based service. Data from these studies were substantially heterogenous (I2 = 99%, p < 0.001) and the random effects model was used for meta-analysis. The pooled analysis showed no significant difference in the cost of health care provided by hospitalists and NH (MD = $92.1, 95% CI [−910.4, 1094.6], p = 0.86); Figure 3. This result held true on sensitivity analysis by removing each study data at a time (Figure A3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of cost of service in Hospitalist- and Non-hospitalist-based care models.

Figure A3.

Forest plot of cost of service in Hospitalist- and Non-hospitalist-based care models.

Cumulative analysis showed that till 2008, the cost of service was markedly decreased with hospitalists compared to NH. After 2008, there was no significant difference between hospitalist and NH groups (Figure A4). There was no dissemination bias as indicated by Egger’s regression test (p = 0.79).

Figure A4.

Forest plot of cumulative cost in Hospitalist- and Non-hospitalist-based care models.

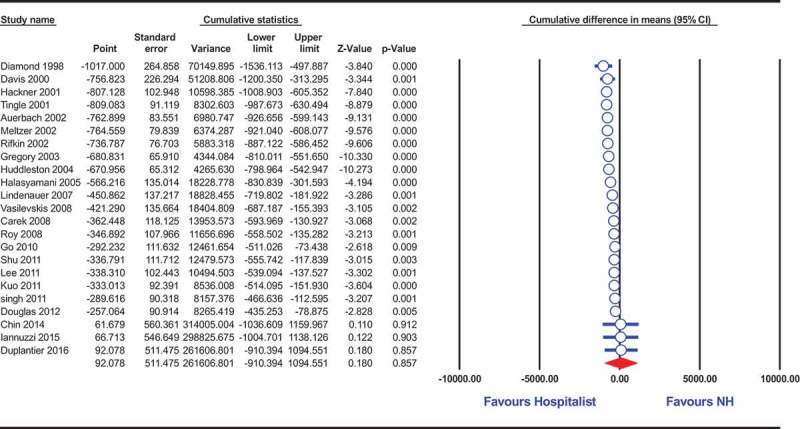

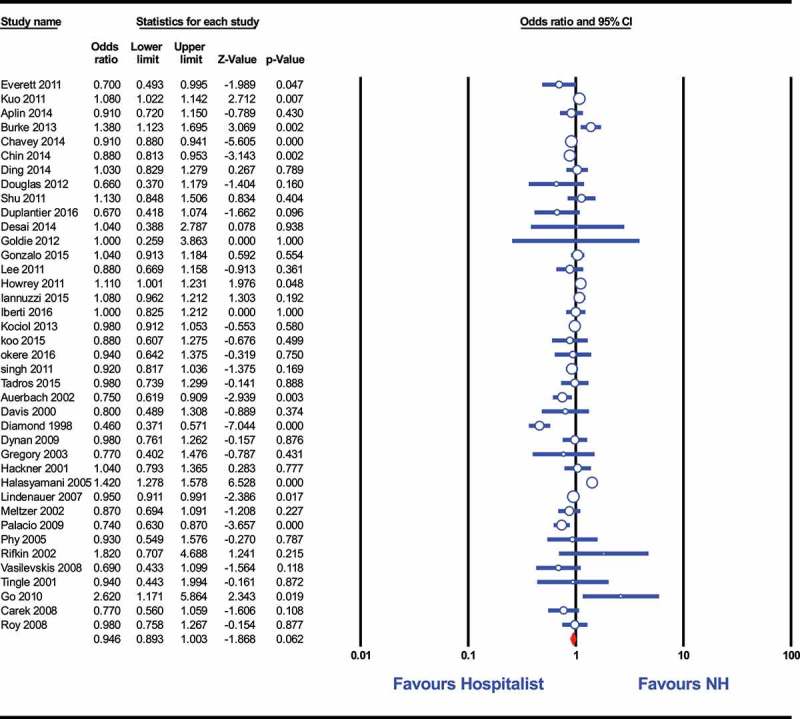

3.2.3. 30-day readmission or in-hospital mortality

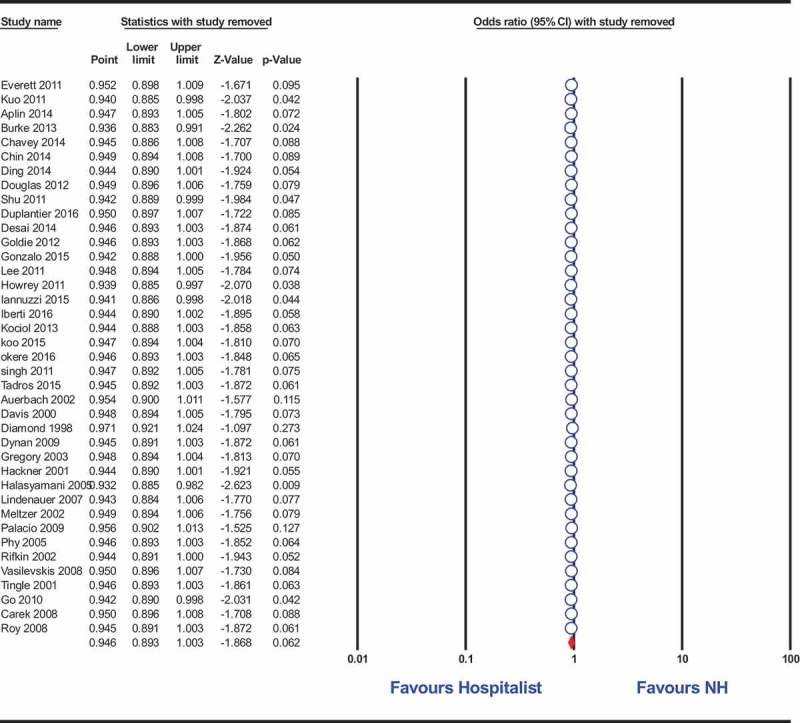

Data from 39 heterogeneous studies (I2 = 80%, p < 0.001) that included 375,570 participants contributed to the calculation of the summary effect estimate for readmission/mortality. Under the random effects model, the overall odds ratio showed marginal superiority of hospitalist over NH in terms of readmission/mortality (OR = 0.95, 95% CI [0.89 to 1], p = 0.06); Figure 4. However, this effect was sensitive to the removal of single studies in sensitivity analysis, taking the effect size towards significant superiority of hospitalist over NH (Figure A5).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of readmission or mortality for Hospitalist- and Non-hospitalist-based care models.

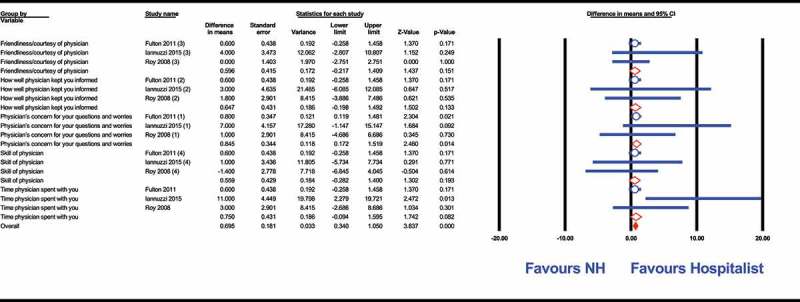

Figure 5.

Forest plot of patient satisfaction for Hospitalist- and Non-hospitalist-based care models.

Figure A5.

Forest plot of readmission/mortality in Hospitalist- and Non-hospitalist-based care models.

3.2.4. Patients’ satisfaction

Out of the included studies, six investigated patients’ satisfaction with the healthcare service provided in both hospitalist- and non-hospitalist- based settings. The Press-Ganey survey was used in three of these studies. Pooled analysis of the commonly reported items of the Press-Ganey survey showed no significant difference in friendliness/courtesy of physician (p = 0.15), how well physician kept the patient informed (p = 0.13), skill of physician (p = 0.2), and time spent with his patient (p = 0.08). Physician’s concern for patients’ questions and worries (p = 0.01) and the overall score (p < 0.001) tended to favor the hospitalist over NH service (Figure 5).

The remaining three studies used self-designed questionnaires and Picker-Commonwealth patient satisfaction survey. Data provided by these studies showed no difference between hospitalist- and NH-treated cohorts in terms of physician ability to keep the patient and family informed (p = 0.67), physician courtesy and friendliness (p = 0.87), skill of the physician (p = 0.22), physician and staff ability to work together (p = 0.30), or likelihood of recommending the hospital (p = 0.13). Overall patient satisfaction was not different according to the results of the Picker-Commonwealth survey (p = 0.2).

3.2.5. Studies with incomplete published data

In 12 out of the 14 studies that reported incomplete data, LOS was shorter for the hospitalist service. Hospital cost was lower for the hospitalist model in seven studies, similar in six, and higher in one study.

4. Discussion

Our analysis showed that hospitalists reduce LOS, readmissions and in-hospital mortality. The overall summary estimate showed marginally significant result that was sensitive to the effect of few singles studies which removal draw the results towards favoring the hospitalist model. Hospitalists increased the efficiency of inpatient care without compromising the quality of service. Inversely, patients’ satisfaction was similar or even higher in patients cared for by hospitalists compared to NH. On the other hand, there was no difference in terms of hospital cost between hospitalist and NH services. Beyond these benefits, there is compelling evidence that hospitalists promoted clinical care development and integration [56,69,70]. Particularly, they supported the development of patient safety guidelines [71] and became more efficient in teaching [72]. Rifkin et al. reported that hospitalists are more likely to comply with national guidelines of care in pneumonia patients [56]. Another report by Hauer et al. showed that trainee satisfaction was higher in the case of hospitalist than non-hospitalist teachers [72]. In our meta-analysis of published studies to date, we found a significantly shorter LOS among hospitalists compared with NHs, which persisted on leave out one sensitivity analysis even though cumulative meta-analysis showed decreasing trend of the MD in LOS between the hospitalist and NH groups from 2.4 days in 1998 to 0.67 in 2016.

Our results describe for the first time interesting trends displayed by cumulative meta-analysis. Cumulative analysis for the cost of service over years revealed an interesting movement towards equality of cost in both groups. From the inception of studies that evaluated the hospitalist-based healthcare service till 2008, the cost of service was significantly decreased with hospitalists compared to the NH groups. After 2008, there was no significant difference between hospitalist and NH groups. Since last 10 years there is an increasing role of hospitalists been primary attending in higher risk patients with higher comorbidities including intensive care units (Due to the concept of Open ICU getting more popular with Intensivist and surgeons taking the role of consultants) which might explain change to overall cost after 2008.

The declined mean difference in hospital charges overtime might be attributed to the increased average case mix index (CMI) [73]. Despite being originally created for calculating hospital costs, CMI has been recently used as an indicator of disease severity and the large volume of comorbidities being treated. Tadros et al. argued that the increased cost of hospitalization is expected because of the increased resources required to treat patients with higher CMI [73,74].

Continuity of care for hospitalized patients was documented to be associated with favorable outcomes such as lower risk of hospitalization, fewer emergency department visits, and higher patient satisfaction [75–77]. In this regard, Turner and colleagues studied the effect of discontinuity of hospitalist care on costs and readmission. They showed that hospital physician discontinuity was associated modest rise in hospital charges [78]. On the contrary Hansen et al did a retrospective observational study, which concluded that hospitalist physician continuity does not appear to be associated with the incidence of adverse events [79]. From the conflicting studies we are unable to draw conclusions regarding whether continuity of care explained the declining mean differences in cost or LOS. Perhaps, team dynamics and intra-hospitalist variability should be indubitably researched.

Cross-Sectional study done by Kripalani et al from Emory university showed that hospitalists are considered highly effective educators by trainees in setting of academic center and were more effective than subspecialists [80]. There has been an increase in academic hospitalists serving as teaching faculty in academic centers. Chung et al studied the effectiveness of academic Hospitalists on clinical education and concurred not only more resident satisfaction among residents rotating under hospitalist teaching service but also cultivate awareness of cost effectiveness and systems-based improvements in the field of inpatient medicine [81]. As inpatient leaders hospitalists collaborate well with emergency physicians in discharging patients, which meet observation criteria but could be well managed as outpatient. Hospitalists are also used to managing complex patients themselves, minimizing use of subspecialists like nephrology and infectious diseases. Hospitalists are well aligned with health care system and collaborate well with primary care providers, case managers and other subspecialists decreasing length of stay and improving resource utilization and decreasing readmissions [82,83]. Most hospitalists are acquiesced taking care of immediate high acuity inpatient issues in hospital, often deescalate treatment at the earliest, delegating non-emergent tests to primary care and subspecialists to be done as outpatient and been physically onsite coordinating care in a timely manner all factors leads to fewer resources utilized [32,36]. Primary providers can focus their practice more on outpatient care avoiding complexities of hospital based medicine and the physical need to be in the hospital to dealing with inpatient emergencies.

Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are scarce on the discussion of hospitalist care model. The majority of the included studies were retrospective with the exception of few RCTs that included small number of participants [35,42]. The findings of an RCT conducted by Huddleston et al. is consistent with the results of the present study in terms of LOS and hospital charges [42]. However, another RCT with small sample size showed no difference in LOS and readmission rate [35].

Future studies should adopt a randomized prospective design to explore the effect of potential confounders that have not been controlled for so far. Moreover, data are still not available to answer the question raised by Rachion et al. [12] in 2012 regarding the time of LOS and cost reduction after implementation of a hospitalist program. Therefore, further study of the issue in longitudinal studies with extended follow-up periods would be of interest.

This study has some limitations. First, we could not assess the risk of bias in the included studies due to heterogenous study design adopted in different settings. In addition, evidence from meta-analysis of RCTs was lacking due to the paucity of randomized data identified in the literature.

5. Conclusion

To recapitulate, the introduction of hospitalists to inpatient service translates to changes in LOS and readmission rates. Hospitalist model was beneficial in the reduction of LOS and in-hospital mortality/30-day readmission rates, yet not in the containment of hospital costs. We acquiesce that there has been an increase in academic hospitalists over time and the role they undertake in furthering medical education. Many questions still remain unanswered regarding post-discharge short term mortality (90 Day Mortality) for inpatients comparing programs using hospitalists or NH which needs further investigation.

Appendix

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1]. Kuo Y-F, Sharma G, Freeman JL, et al. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the USA. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Meltzer DO, Chung JW.. US trends in hospitalization and generalist physician workforce and the emergence of hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(5):453–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, et al. Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2589–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Southern WN, Berger MA, Bellin EY, et al. Hospitalist care and length of stay in patients requiring complex discharge planning and close clinical monitoring. Arch Internal Med. 2007;167(17):1869–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Roy A, Heckman MG, Roy V, editors. Associations between the hospitalist model of care and quality-of-care-related outcomes in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2006 Jan 1 (Vol. 81, No. 1, pp. 28-31). Elsevier.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Myers JS, Bellini LM, Rohrbach J, et al. Improving resource utilization in a teaching hospital: development of a nonteaching service for chest pain admissions. Acad Med. 2006;81(5):432–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Halasyamani LK, Valenstein PN, Friedlander MP, et al. A comparison of two hospitalist models with traditional care in a community teaching hospital. Am J Med. 2005;118(5):536–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Kaboli PJ, Barnett MJ, Rosenthal GE. Associations with reduced length of stay and costs on an academic hospitalist service. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(8):561–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Coffman J, Rundall TG. The impact of hospitalists on the cost and quality of inpatient care in the USA: a research synthesis. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(4):379–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Everett G, Uddin N, Rudloff B. Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay for community internists, hospitalists, and academicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(5):662–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Dynan L, Stein R, David G, et al. Determinants of hospitalist efficiency: a qualitative and quantitative study. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(6):682–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Rachoin J-S, Skaf J, Cerceo E, et al. The impact of hospitalists on length of stay and costs: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(1):e23–e30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Gonzalo JD, Kuperman EF, Chuang CH, et al. Impact of an overnight internal medicine academic hospitalist program on patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1795–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Chavey WE, Medvedev S, Hohmann S, et al. The status of adult inpatient care by family physicians at US academic medical centers and affiliated teaching hospitals 2003 to 2012: the impact of the hospitalist movement. Fam Med. 2014;46(2):94–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Burke RE, Whitfield E, Prochazka AV. Effect of a hospitalist-run postdischarge clinic on outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Aplin KS, Coutinho McAllister S, Kupersmith E, et al. Caring for patients in a hospitalist-run clinical decision unit is associated with decreased length of stay without increasing revisit rates. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(6):391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, et al. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Thakkar R, Wright SM, Alguire P, et al. Procedures performed by hospitalist and non-hospitalist general internists. J en Intern Med. 2010;25(5):448–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P, et al. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):859–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Carek PJ, Boggan H, Mainous A, et al. Inpatient care in a community hospital: comparing length of stay and costs among teaching, hospitalist, and community services. Family Medicine-Kansas City-. 2008;40(2):119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Chadaga SR, Shockley L, Keniston A, et al. Hospitalist-led medicine emergency department team: associations with throughput, timeliness of patient care, and satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):562–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Chin DL, Wilson MH, Bang H, et al. Comparing patient outcomes of academician-preceptors, hospitalist-preceptors, and hospitalists on internal medicine services in an academic medical center. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1672–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Craig DE, Hartka L, Likosky WH, et al. Implementation of a hospitalist system in a large health maintenance organization: the Kaiser Permanente experience. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(4_Part_2):355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Davis KM, Koch KE, Harvey JK, et al. Effects of hospitalists on cost, outcomes, and patient satisfaction in a rural health system. Am J Med. 2000;108(8):621–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Desai AP, Satoskar R, Appannagari A, et al. Co-management between hospitalist and hepatologist improves the quality of care of inpatients with chronic liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(4):e30–e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Diamond HS, Goldberg E, Janosky JE. The effect of full-time faculty hospitalists on the efficiency of care at a community teaching hospital. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(3):197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Ding YY, Sun Y, Tay JC, et al. Short-term outcomes of seniors aged 80 years and older with acute illness: hospitalist care by geriatricians and other internists compared. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Duplantier NL, Briski DC, Luce LT, et al. The effects of a hospitalist comanagement model for joint arthroplasty patients in a teaching facility. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(3):567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Everett G, Uddin N. Should a cardiologist be the principal attending physician or the consultant to a hospitalist or general internist for cardiovascular disease admissions?. Am Heart Hosp J. 2010;9(2):81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Everett GD, Anton MP, Jackson BK, et al. Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay associated with general internists and hospitalist physicians at a community hospital. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(9):626–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Fulton BR, Drevs KE, Ayala LJ, et al. Patient satisfaction with hospitalists: facility-level analyses. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2):95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Go JT, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Auerbach A, et al. Do hospitalists affect clinical outcomes and efficiency for patients with acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (UGIH)? J Hosp Med. 2010;5(3):133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Goldie CL, Prodan-Bhalla N, Mackay M. Nurse practitioners in postoperative cardiac surgery: are they effective? Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;22:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital Economics of the Hospitalist. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):905–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Hackner D, Tu G, Braunstein GD, et al. The value of a hospitalist service: efficient care for the aging population? Chest J. 2001;119(2):580–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Halpert AP, Pearson SD, LeWine HE, et al. The impact of an inpatient physician program on quality, utilization, and satisfaction. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6(5):549–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Hock Lee K, Yang Y, Soong Yang K, et al. Bringing generalists into the hospital: outcomes of a family medicine hospitalist model in Singapore. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Hollier JM, Wilson SD. No variation in patient care outcomes after implementation of resident shift work duty hour limitations and a hospitalist model system. Am J Med Qual. 2017;32(1):27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Howrey BT, Kuo Y-F, Goodwin JS. Association of care by hospitalists on discharge destination and 30-day outcomes after acute ischemic stroke. Med Care. 2011;49(8):701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplastya randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Iannuzzi MC, Iannuzzi JC, Holtsbery A, et al. Comparing hospitalist-resident to hospitalist-midlevel practitioner team performance on length of stay and direct patient care cost. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):65–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Iberti CT, Briones A, Gabriel E, et al. Hospitalist-vascular surgery comanagement: effects on complications and mortality. Hosp Pract (1995). 2016;44(5):233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Kociol RD, Hammill BG, Fonarow GC, et al. Associations between use of the hospitalist model and quality of care and outcomes of older patients hospitalized for heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1(5):445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Koo DJ, Goring TN, Saltz LB, et al. Hospitalists on an inpatient tertiary care oncology teaching service. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):e114–e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Kulaga ME, Charney P, O’mahony SP, et al. The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Kuo Y-F, Goodwin JS. Association of hospitalist care with medical utilization after discharge: evidence of cost shift from a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Lindenauer PK, Chehabeddine R, Pekow P, et al. Quality of care for patients hospitalized with heart failure: assessing the impact of hospitalists. Arch Internal Med. 2002;162(11):1251–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Lucas BP, Candotti C, Margeta B, et al. Hand-carried echocardiography by hospitalists: a randomized trial. Am J Med. 2011;124(8):766–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52]. Molinari C, Short R. Effects of an HMO hospitalist program on inpatient utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7(11):1051–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53]. Okere AN, Renier CM, Willemstein M. Comparison of a pharmacist-hospitalist collaborative model of inpatient care with multidisciplinary rounds in achieving quality measures. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54]. Palacio C, Alexandraki I, House J, et al. A comparative study of unscheduled hospital readmissions in a resident-staffed teaching service and a hospitalist-based service. South Med J. 2009;102(2):145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55]. Phy MP, Vanness DJ, Melton LJ, et al. Effects of a hospitalist model on elderly patients with hip fracture. Arch Internal Med. 2005;165(7):796–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56]. Rifkin WD, Burger A, Holmboe ES, et al. Comparison of hospitalists and nonhospitalists regarding core measures of pneumonia care. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(3):129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57]. Rifkin WD, Conner D, Silver A, et al. Comparison of processes and outcomes of pneumonia care between hospitalists and community-based primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(10):1053–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58]. Rifkin WD, Holmboe E, Scherer H, et al. Comparison of hospitalists and nonhospitalists in inpatient length of stay adjusting for patient and physician characteristics. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1127–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59]. Roy CL, Liang CL, Lund M, et al. Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60]. Roytman MM, Thomas SM, Jiang CS. Comparison of practice patterns of hospitalists and community physicians in the care of patients with congestive heart failure. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(1):35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61]. Scheurer DB, Miller JG, Blair DI, et al. Hospitalists and improved cost savings in patients with bacterial pneumonia at a state level. South Med J. 2005;98(6):607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62]. Shu CC, Lin JW, Lin YF, et al. Evaluating the performance of a hospitalist system in Taiwan: a pioneer study for nationwide health insurance in Asia. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63]. Singh S, Fletcher KE, Schapira MM, et al. A comparison of outcomes of general medical inpatient care provided by a hospitalist-physician assistant model vs a traditional resident-based model. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64]. Smith PC, Westfall JM, Nicholas RA. Primary care family physicians and 2 hospitalist models: comparison of outcomes, processes, and costs. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(12):1021–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65]. Tadros RO, Faries PL, Malik R, et al. The effect of a hospitalist comanagement service on vascular surgery inpatients. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(6):1550–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66]. Tingle LE, Lambert CT. Comparison of a family practice teaching service and a hospitalist model: costs, charges, length of stay, and mortality. Family Medicine-Kansas City-. 2001;33(7):511–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67]. Vasilevskis EE, Meltzer D, Schnipper J, et al. Quality of care for decompensated heart failure: comparable performance between academic hospitalists and non-hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1399–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68]. Wise KR, Akopov VA, Williams BR Jr., et al. Hospitalists and intensivists in the medical ICU: a prospective observational study comparing mortality and length of stay between two staffing models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69]. Pressel DM, Rappaport DI, RN C-B NW, et al. Nurses’ assessment of pediatric physicians: are hospitalists different? J Healthc Manag. 2008;53(1):14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70]. Meltzer D. Hospitalists and the doctor-patient relationship. J Leg Stud. 2001;30(S2):589–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71]. Pham HH, Devers KJ, Kuo S, et al. Health care market trends and the evolution of hospitalist use and roles. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):101–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72]. Hauer KE, Wachter RM, McCulloch CE, et al. Effects of hospitalist attending physicians on trainee satisfaction with teaching and with internal medicine rotations. Arch Internal Med. 2004;164(17):1866–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73]. Tadros RO, Tardiff ML, Faries PL, et al. Vascular surgeon-hospitalist comanagement improves in-hospital mortality at the expense of increased in-hospital cost. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65(3):819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74]. Mendez CM, Harrington DW, Christenson P, et al. Impact of hospital variables on case mix index as a marker of disease severity. Popul Health Manag. 2014;17(1):28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75]. Saultz JW, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Anna Family Med. 2004;2(5):445–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76]. Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Anna Family Med. 2005;3(2):159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77]. Van Walraven C, Oake N, Jennings A, et al. The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(5):947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78]. Turner J, Hansen L, Hinami K, et al. The impact of hospitalist discontinuity on hospital cost, readmissions, and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1004–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79]. O’leary KJ, Turner J, Christensen N, et al. The effect of hospitalist discontinuity on adverse events. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80]. Kripalani S, Pope AC, Rask K, et al. Hospitalists as teachers. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(1):8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81]. Chung P, Morrison J, Jin L, et al. Resident satisfaction on an academic hospitalist service: time to teach. Am J Med. 2002;112(7):597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82]. Jungerwirth R, Wheeler SB, Paul JE. Association of hospitalist presence and hospital-level outcome measures among medicare patients. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83]. Palabindala V, Abdul Salim S. Era of hospitalists. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2018;8(1):16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]