This cohort study of mother-child pairs from Tennessee investigates whether variations in maternal social networks are associated with cognitive development in children.

Key Points

Question

How are social relationships and structures, such as dyads, families, and neighborhoods, associated with early cognitive development in children?

Findings

In this cohort study of 1082 mother-child pairs, the mother’s social networks were significantly positively associated with early childhood cognitive development. Being in a large family network was significantly associated with lower cognitive performance.

Meaning

The findings suggest that maternal social relationships are associated with cognitive development in children and that social relationships beyond the mother-child-father triad are significantly associated with cognitive development.

Abstract

Importance

This study examines how different types of social network structures are associated with early cognitive development in children.

Objectives

To assess how social relationships and structures are associated with early cognitive development and to elucidate whether variations in the mother’s social networks alter a child’s early cognitive development patterns.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study used data from 1082 mother-child pairs in the University of Tennessee Health Science Center–Conditions Affecting Neurocognitive Development and Learning and Early Childhood project to examine the association between networks of different levels of complexity (triad, family, and neighborhood) and child cognitive performance after adjustment for the mother’s IQ, birth weight, and age, and the father’s educational level. The final model was adjusted for the household poverty level. Data were collected from December 2006 through January 2014 and analyzed from October through November 2018.

Exposures

The child-mother relationship, child-mother-father triad, family setting, child’s dwelling network, mother’s social support network, and neighborhood networks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Measure of cognitive development of the child using Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) at 2 years of age.

Results

Of 1082 participants, 544 (50.3%) were males and 703 (65.1%) were African American; the mean (SD) age was 2.08 (0.12) years. Large family size had a negative association with early cognitive development, with a mean 2.21-point decrease in BSID coefficient score (95% CI, 0.40 to 4.02; P = .01). Mother’s social support network size was positively associated early cognitive development, with a mean 0.40-point increase in BSID coefficient score (95% CI, 0.001 to 0.80; P = .05). Knowing many neighbors was not statistically significantly associated with early cognitive development, with a mean 1.39-point increase in BSID coefficient score (95% CI, −0.04 to 2.83; P = .06).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that maternal social relationships are associated with cognitive development in children and that social relationships beyond the mother-child-father triad are significantly associated with children’s cognitive development. This study investigates the environmental influences on child health outcomes and, specifically, how early cognitive development is associated with social networks for the primary caregiver.

Introduction

Social networks, broadly defined as interconnectedness with other people, can influence behavioral and health outcomes.1,2,3 The importance of social and relational environments for cognitive development and emotional well-being is well known.4,5,6,7,8 Networks of social support can attenuate psychologic stress and provide support to people experiencing neurotic symptoms.9,10,11,12 The progress that children make when forming healthy relationships during the period from birth to 5 years can have long-lasting benefits throughout their entire lives.13 In early childhood development, relationships between children and caregivers are crucial and play an important role in socialization.14,15,16,17 The social environment and relationships early in life are critical for children’s emotional, intellectual, and social development into adulthood and can considerably influence the child’s life-long adaptation strategy.6,13,18,19,20,21 Social networks channel benefits and risks associated with social health determinants, such as health-related knowledge, attitudes, and capacity to cope with adversities associated with social disadvantage.1,4,6,22,23,24

The network microsystem has been regarded as a critical domain for child development.6,15 Children’s early experience of relationships can influence a wide range of developmental outcomes,7,15,25 and the child-mother relationship is important in shaping early childhood development.17,21,26,27 From the child’s perspective, these intimate bonds form the basis for solid attachments and provide prototypes for adulthood and the basis for social interaction.15,28,29,30,31 The child-mother relationship is not the only determinant but is nested within larger social contexts. The father plays a significant role in children’s development,17,25,32,33,34,35 as do the number of siblings and household size.36,37 Social support, along with other aspects of the social networks surrounding the child-mother bond, can influence the child-mother relationship.38,39 For mothers, social support is significantly associated with lower maternal stress, which is correlated with better child development.40,41,42,43

Little is known about how different types of relationships, especially the multiple social networks of the mother, are associated with children’s cognitive development. Only a few studies8,43 have characterized a range of maternal social networks and examined their association with early childhood cognitive development. In this study, we examined the associations of multiple types of social relationships and structures, including the child-mother-father triad, family setting, and larger neighborhood network conditions, with early cognitive development. Within a large group of white and African American families in Memphis and Shelby County, Tennessee, we examined how social relationships and networks were associated with children’s cognitive development.

Methods

Data Source

This study followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.44 We used data from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center’s Conditions Affecting Neurocognitive Development and Learning in Early Childhood (CANDLE) project.45 Recruitment for CANDLE started from December 2006 through July 2011. A total of 1503 mothers with a low-risk pregnancy were recruited at 16 to 28 weeks’ gestation from 5 participating health care settings in Shelby County, Tennessee. For 1082 mothers, a measure of cognitive development of the child at age 2 was available, representing the final sample for analysis. In this subset, the race/ethnicity of participants reflected the sociodemographic characteristics of Shelby County. This study was approved by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center institutional review board and participant written informed consent was obtained. Data were collected from December 2006 through January 2014 and analyzed from October through November 2018.

Variable Definitions

Table 1 summarizes the key variables used in the analysis and their descriptive distribution. Because our outcome variable was cognitive development at 2 years of age, we used the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID), which is designed to measure the developmental functioning of young children and to identify potential developmental delays.46,47 The BSID46 is composed of 5 scales: cognitive (score range, 55-145), language (47-153), motor (46-154), socio-emotional (55-145), and adaptive behavior (40-160).

Table 1. Characteristics of 1082 Study Participants in CANDLE.

| Variable | Valuea | BSID Score, Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| BSID categories | 1082 (100) | 97.74 (12.87) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 544 (50.3) | 96.25 (12.73) |

| Female | 538 (49.7) | 99.26 (12.85) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African American | 703 (65.1) | 105.09 (13.33) |

| White | 377 (34.9) | 93.81 (10.75) |

| Poverty level | ||

| Below FPL | 405 (40.9) | 93.51 (10.73) |

| At or above FPL | 586 (59.1) | 101.27 (13.44) |

| Father’s educational level | ||

| Some high school or graduated high school | 661 (63.0) | 95.31 (11.58) |

| Some college | 76 (7.2) | 99.28 (14.67) |

| College and graduate school | 312 (29.7) | 103.17 (13.50) |

| Father’s cohabitation | ||

| Father not living at home | 421 (42.0) | 94.53 (11.38) |

| Father living at home | 570 (58.0) | 100.61 (13.47) |

| Family size | ||

| <6 People | 813 (75.1) | 99.19 (13.23) |

| ≥6 People | 269 (24.9) | 93.36 (10.63) |

| Mother’s social network size, mean (SD) | 3.49 (1.82) | NA |

| Neighborhood embeddedness | ||

| Not knowing many people in the neighborhood | 408 (41.2) | 95.47 (11.46) |

| Knowing many people in the neighborhood | 582 (58.8) | 99.92 (13.65) |

| Mother’s WASI IQ, mean (SD) | 96.11 (16.25) | NA |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 3266.04 (537.10) | NA |

| Mother’s age at child’s birth, mean (SD), y | 26.55 (5.50) | NA |

Abbreviations: BSID, Bayley Scales of Infant Development; CANDLE, Conditions Affecting Neurocognitive Development and Learning in Early Childhood; FPL, federal poverty level; NA, not applicable; WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of participants unless otherwise indicated.

Because of the availability of extensive information about child-mother relationships and their contexts in the CANDLE study, we systematically examined multiple layers of networks and their association with cognitive development in early childhood.

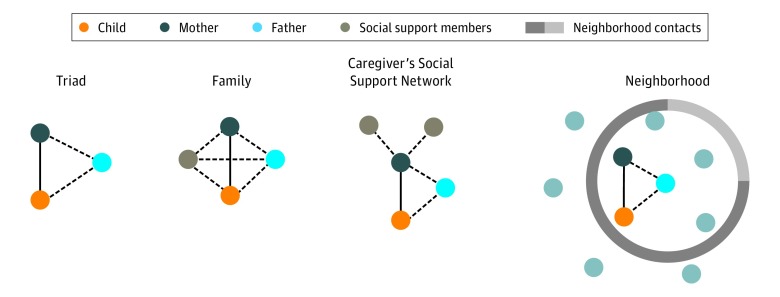

The framework of the stepwise network structures is presented in the Figure. We studied 4 network conditions: father’s cohabitation (triad), large family network (family), mother’s social support network (caregiver’s social support network), and neighborhood. Family network size was estimated using data on household size, including all adults and other children living with the child involved in the CANDLE study. The mean (SD) of the household size variable was 4.37 (1.51) people, and we defined a family of 6 or more as a large family network. The primary caregiver’s social network was defined by the mother’s self-reported social support network. The mothers participating in CANDLE reported 3 to 4 people they could rely on for help, with a mean (SD) of 3.49 (1.82) people. We also included an indicator variable that asked mothers if they knew many people in their neighborhood.

Figure. Stepwise Network Exposure Conditions.

The solid line between mother and child represents a tie that is always present, as in this study because children were recruited through their mother; dashed lines represent ties that may or may not exist.

Statistical Analysis

We used multivariate robust regression models to study the associations of multiple social networks and cognitive development of 2-year-old children. To minimize the influence of outliers, we used robust regression methods.48 This approach allowed us to investigate how multiple layers of social network conditions are associated with cognitive development in early childhood. A 2-sided P ≤ .05 was set a priori to represent a statistically significant difference. We used Stata, version 14 (StataCorp) for statistical analysis.

We adjusted for several maternal and socioeconomic characteristics in a stepwise fashion. The first step included network variables.32 We included the following factors as independent variables in the model because of potential confounding: mother’s IQ, child’s birth weight, mother’s age, and father’s educational level. We originally tested other possible confounders, such as child sex, gestational age at birth, breastfeeding, birth weight, maternal smoking, and mother’s educational level. However, they were not included in the model because they did not substantively influence the coefficient of the main variables. The second model was adjusted for the same variables as the main model, but family poverty level was added.49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57

Results

Of 1082 participants, 544 (50.3%) were males and 703 (65.1%) were African American; the mean (SD) age was 2.08 (0.12) years. The BSID score at 2 years of age ranged from 55 to 145 (mean [SD], 97.74 [12.87]). After adjustment for household poverty (Table 2), some social network characteristics were significantly associated with cognitive development. Mother’s social network was significantly associated with increased mean BSID coefficient scores (difference, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.001 to 0.80; P = .05), whereas living in a large family was associated with a 2.21-point decreased mean BSID coefficient score (95% CI, −4.02 to −0.40; P = .01). Father’s cohabitation (0.07; 95% CI, −1.58 to 1.73) and knowing many neighbors (1.39; 95% CI, −0.04 to 2.83; P = .06) were not significantly associated with an increased mean BSID coefficient score after controlling for poverty level.

Table 2. Stepwise Network Associations in Early Cognitive Development at 2 Years of Age.

| Characteristic | Model 1a | Model 2b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient Value (95% CI)c | P Value | Coefficient Value (95% CI)c | P Value | |

| Father’s cohabitation | 0.40 (−1.22 to 2.01) | NA | 0.07 (−1.58 to 1.73) | NA |

| Large family | −2.41 (−4.21 to −0.61) | .01 | −2.21 (−4.02 to −0.40) | .01 |

| Mother’s social network | 0.43 (0.03 to 0.83) | .04 | 0.40 (0.001 to 0.80) | .05 |

| Neighborhood | 1.44 (0.01 to 2.88) | .05 | 1.39 (−0.04 to 2.83) | .06 |

| Below poverty level | NA | NA | −1.59 (−3.33 to 0.15) | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

The following factors were induced as independent variables because of potential confounding: mother’s IQ, birth weight, mother’s age, and father’s educational level.

Same variables as model 1 plus household poverty level.

Coefficient values are defined as the difference in Bayley Scales of Infant Development scores.

Discussion

The importance of the mother-child bond for child development has long been recognized.17,21,26,27 However, to our knowledge, the multiple layers of a mother’s social relationships beyond mother and child have not been simultaneously examined. Social relationships do not exist in isolation, and mother-child relationships are intertwined with other relationships, such as spouses, family or dwelling settings, and friendships. Our empirical analysis simultaneously investigated the association of multiple layers of the mothers’ social networks with children’s early cognitive development. Most social contacts and contexts of young children were determined by their primary caregiver’s social networks, who were often mothers in the CANDLE cohort.

In this study, we showed that a primary caregiver’s network conditions were significantly associated with early cognitive development in children. Network variables were significantly associated with early cognitive development after controlling for a number of biological and social confounders. Specifically, the mother’s social network seemed to have a beneficial association with the cognitive development of children, whereas family size had a negative association. Although father’s cohabitation has been suggested to be an important factor for early childhood cognitive development,17,34,58 after controlling for other social network conditions of the mother and other possible confounders, we did not find evidence for this result in our study. This might be because of the local context—Memphis is an economically disadvantaged area of the United States, which might mitigate an otherwise positive association of father’s cohabitation.

Many of our findings are consistent with previous studies36,37,59 of early cognitive development and add important evidence that social networks across several levels may be significantly associated with cognitive development in early childhood. Being raised in a large family (≥6 people) was significantly associated with lower cognitive performance, a finding that is also in line with previous studies of large families.36,37 However, past studies have also shown that family size can have advantages (ie, positive socialization) and disadvantages (ie, resource competition or limitation).59 Our findings about the negative association of family size may have been attributable to the limited attention and resources that a child received from the primary caregiver when faced with competing demands. Further investigation is needed to identify the mechanisms of this disadvantage.

We also reported results that large maternal social networks were positively associated with the cognitive development of children. Children of mothers who knew many people in the neighborhood had better cognitive development. It is possible that mothers who socialized locally provided children with more opportunities for playdates with other children or stimulation through more social activities. In addition, the primary caregiver’s social networks within the neighborhood may have buffered the association between reduced economic resources and child outcomes.60 Our results captured the importance of a community-based social life.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. We did not have information on relationship quality. Our measure of neighborhood embeddedness was based on subjective perception self-report. In addition, we only looked at relational embeddedness, not the physical or built neighborhood environment. Further research is needed to examine the nature of the association between neighborhood embeddedness, both physical and relational, and cognitive development in early childhood.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that social relationships beyond the mother-child-father triad are significantly associated with children’s cognitive development and that maternal social relationships may be associated with the cognitive development of children.

References

- 1.Valente TW. Social Networks and Health: Models, Methods, and Applications. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195301014.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):-. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bearman PS, Moody J, Stovel K. Chains of affection: the structure of adolescent romantic and sexual networks. Am J Sociol. 2004;110(1):44-91. doi: 10.1086/386272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843-857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thoits PA. Multiple identities and psychological well-being: a reformulation and test of the social isolation hypothesis. Am Sociol Rev. 1983;48(2):174-187. doi: 10.2307/2095103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cochran MM, Brassard JA. Child development and personal social networks. Child Dev. 1979;50(3):601-616. doi: 10.2307/1128926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships. 2004. Working paper No. 1. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2004/04/Young-Children-Develop-in-an-Environment-of-Relationships.pdf. Accessed January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson S. The social network, support and neurosis: the function of attachment in adult life. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;131(2):185-191. doi: 10.1192/bjp.131.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson S, Byrne DG, Duncan-Jones P, Adcock S, Scott R, Steele GP. Social bonds in the epidemiology of neurosis: a preliminary communication. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132(5):463-466. doi: 10.1192/bjp.132.5.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamarck TW, Manuck SB, Jennings JR. Social support reduces cardiovascular reactivity to psychological challenge: a laboratory model. Psychosom Med. 1990;52(1):42-58. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199001000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458-467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA, eds; Institute of Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Integrating the Science of Early Childhood Development . From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.England M, Sroufe LA. Predicting peer competence and peer relationships in childhood from early parent-child relationships In: Parke RD, Ladd GW, eds. Family-Peer Relationships: Modes of Linkage. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992:77-106. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartup WW. Social relationships and their developmental significance. Am Psychol. 1989;44(2):120-126. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parke RD, Buriel R. Socialization in the family: ethnic and ecological perspectives: child and adolescent development In: Damon W, Lerner RM, eds. Child and Adolescent Development: An Advanced Course. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:95-138. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Main M, Weston DR. The quality of the toddler’s relationship to mother and to father: related to conflict behavior and the readiness to establish new relationships. Child Dev. 1981;52(3):932-940. doi: 10.2307/1129097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denham SA, Blair KA, DeMulder E, et al. Preschool emotional competence: pathway to social competence? Child Dev. 2003;74(1):238-256. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denham SA, Brown C. “Plays nice with others”: social–emotional learning and academic success. Early Educ Dev. 2010;21(5):652-680. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2010.497450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Soc Dev. 2007;16(2):361-388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaillant GE. Adaptation to Life. Boston, MA: Little Brown; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berkman LF, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, eds. Social Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000:137-173. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:381-398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bickart KC, Wright CI, Dautoff RJ, Dickerson BC, Barrett LF. Amygdala volume and social network size in humans. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(2):163-164. doi: 10.1038/nn.2724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belsky J. Early human experience: a family perspective. Dev Psychol. 1981;17(1):3-23. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.17.1.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ainsworth MS. Infant-mother attachment. Am Psychol. 1979;34(10):932-937. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ainsworth MDS. Object relations, dependency, and attachment: a theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship. Child Dev. 1969;40(4):969-1025. doi: 10.2307/1127008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fonagy P. Patterns of attachment, interpersonal relationships and health In: Blane D, Brunner E, Wilkinson R, eds. Health and Social Organization: Towards a Health Policy for the Twenty-first Century. New York, NY: Routledge; 1996:125-151. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waters E, Cummings EM. A secure base from which to explore close relationships. Child Dev. 2000;71(1):164-172. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowlby J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris JR. Where is the child’s environment? a group socialization theory of development. Psychol Rev. 1995;102(3):458-489. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.3.458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamis-LeMonda CS, Shannon JD, Cabrera NJ, Lamb ME. Fathers and mothers at play with their 2- and 3-year-olds: contributions to language and cognitive development. Child Dev. 2004;75(6):1806-1820. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00818.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grossmann K, Grossmann KE, Fremmer-Bombik E, Kindler H, Scheuerer-Englisch H, Zimmerman P. The uniqueness of the child-father attachment relationship: fathers’ sensitive and challenging play as a pivotal variable in a 16-year longitudinal study. Soc Dev. 2002;11(3):301-337. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedersen FA, Rubenstein JL, Yarrow LJ. Infant development in father-absent families. J Genet Psychol. 1979;135(1st Half):51-61. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1979.10533416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamb ME. The Role of the Father in Child Development. 4th Ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walberg HJ, Marjoribanks K. Family environment and cognitive development: twelve analytic models. Rev Educ Res. 1976;46(4):527-551. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JV, Reed EW, Reed SC. Intelligence and family size: a paradox resolved. Eugen Q. 1962;9(2):84-90. doi: 10.1080/19485565.1962.9987508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crockenberg SB. Infant irritability, mother responsiveness, and social support influences on the security of infant-mother attachment. Child Dev. 1981;52(3):857-865. doi: 10.2307/1129087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abernethy V. Social network and response to the maternal role. Int J Sociol Fam. 1973;3:86-92. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirschbaum C, Klauer T, Filipp SH, Hellhammer DH. Sex-specific effects of social support on cortisol and subjective responses to acute psychological stress. Psychosom Med. 1995;57(1):23-31. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199501000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guajardo NR, Snyder G, Petersen R. Relationships among parenting practices, parental stress, child behaviour, and children’s social-cognitive development. Infant Child Dev. 2009;18(1):37-60. doi: 10.1002/icd.578 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moss E, Rousseau D, Parent S, St-Laurent D, Saintonge J. Correlates of attachment at school age: maternal reported stress, mother-child interaction, and behavior problems. Child Dev. 1998;69(5):1390-1405. doi: 10.2307/1132273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinraub M, Wolf BM. Effects of stress and social supports on mother-child interactions in single- and two-parent families. Child Dev. 1983;54(5):1297-1311. doi: 10.2307/1129683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sontag-Padilla L, Burns RM, Shih RA, et al. The Urban Child Institute CANDLE Study. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albers CA, Grieve AJ. Test review: Bayley, N. (2006). Bayley scales of infant and toddler development—third edition. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment. J Psychoed Assess. 2007;25(2):180-190. doi: 10.1177/0734282906297199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. 3rd ed Technical Manual. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rousseeuw PJ, Leroy AM. Robust Regression and Outlier Detection. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmer FB, Anand KJ, Graff JC, et al. Early adversity, socioemotional development, and stress in urban 1-year-old children. J Pediatr. 2013;163(6):1733-1739.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gergely G, Watson JS. Early socio-emotional development: contingency perception and the social-biofeedback model In: Rochat P, ed. Early Social Cognition: Understanding Others in the First Months of Life. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999:101-136. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, eds. Consequences of Growing Up Poor. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eamon MK. The effects of poverty on childrens socioemotional development: an ecological systems analysis. Soc Work. 2001;46(3):256-266. doi: 10.1093/sw/46.3.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Dev. 1994;65(2 Spec No):296-318. doi: 10.2307/1131385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am Psychol. 1998;53(2):185-204. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caughy MOB, O’Campo PJ. Neighborhood poverty, social capital, and the cognitive development of African American preschoolers. Am J Community Psychol. 2006;37(1-2):141-154. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-9001-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Earls F. Beyond social capital: spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. Am Sociol Rev. 1999;64(5):633-660. doi: 10.2307/2657367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sampson RJ. How do communities undergird or undermine human development? relevant contexts and social mechanisms In: Booth A, Crouter AC, eds. Does It Take a Village?: Community Effects on Children, Adolescents, and Families. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2001:3-30. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Biller HB. Fathers and Families: Paternal Factors in Child Development. Westpoint, CT: Auburn House; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blake J. Family Size and Achievement (Studies in Demography). Vol 3. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cook TD, Shagle SC, Degirmencioglu SM. Capturing social process for testing mediational models of neighborhood effects In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, eds. Neighborhood Poverty: Context and Consequences for Children. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation Press; 1997:94-119. [Google Scholar]