Key Points

Question

Is postoperative delirium associated with decreased long-term cognition in a heterogeneous adult population?

Findings

In this cohort study of 191 adults undergoing major surgery, patients with delirium had a 0.70-point greater decrease in 90-day telephone-administered Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores than those without delirium after adjustment for preoperative cognitive impairment. Compared with their respective baseline scores, this result was statistically nonsignificant.

Meaning

Although no statistically significant association between 90-day cognition and postoperative delirium was identified, patients with preoperative cognitive impairment appear to have improvements in cognition 90 days after surgery, but this improvement may be attenuated if they become delirious.

Abstract

Importance

Postoperative delirium is associated with decreases in long-term cognitive function in elderly populations.

Objective

To determine whether postoperative delirium is associated with decreased long-term cognition in a younger, more heterogeneous population.

Design, Setting, and Participants

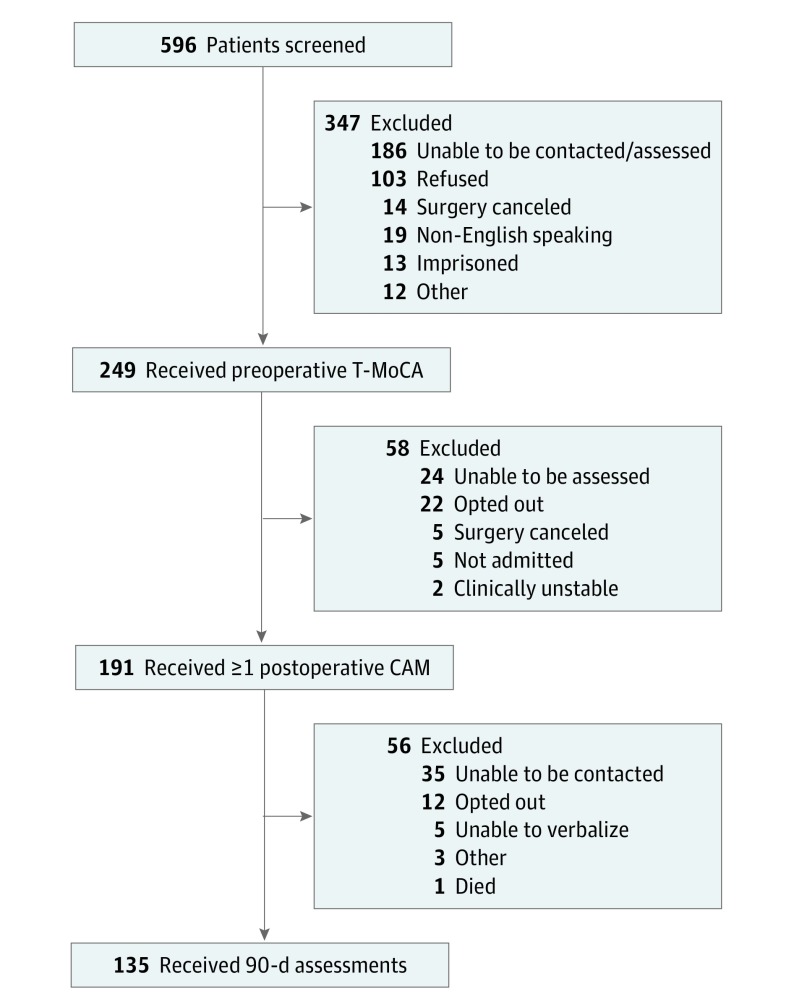

A prospective cohort study was conducted at a single academic medical center (≥800 beds) in the southeastern United States from September 5, 2017, through January 15, 2018. A total of 191 patients aged 18 years or older who were English-speaking and were anticipated to require at least 1 night of hospital admission after a scheduled major nonemergent surgery were included. Prisoners, individuals without baseline cognitive assessments, and those who could not provide informed consent were excluded. Ninety-day follow-up assessments were performed on 135 patients (70.7%).

Exposures

The primary exposure was postoperative delirium defined as any instance of delirium occurring 24 to 72 hours after an operation. Delirium was diagnosed by the research team using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was change in cognition at 90 days after surgery compared with baseline, preoperative cognition. Cognition was measured using a telephone version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (T-MoCA) with cognitive impairment defined as a score less than 18 on a scale of 0 to 22.

Results

Of the 191 patients included in the study, 110 (57.6%) were women; the mean (SD) age was 56.8 (16.7) years. For the primary outcome of interest, patients with and without delirium had a small increase in T-MoCA scores at 90 days compared with baseline on unadjusted analysis (with delirium, 0.69; 95% CI, −0.34 to 1.73 vs without delirium, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.17-1.16). The initial multivariate linear regression model included age, preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System score, preoperative cognitive impairment, and duration of anesthesia. Preoperative cognitive impairment proved to be the only notable confounder: when adjusted for preoperative cognitive impairment, patients with delirium had a 0.70-point greater decrease in 90-day T-MoCA scores than those without delirium compared with their respective baseline scores (with delirium, 0.16; 95% CI, −0.63 to 0.94 vs without delirium, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.40-1.33).

Conclusions and Relevance

Although a statistically significant association between 90-day cognition and postoperative delirium was not noted, patients with preoperative cognitive impairment appeared to have improvements in cognition 90 days after surgery; however, this finding was attenuated if they became delirious. Preoperative cognitive impairment alone should not preclude patients from undergoing indicated surgical procedures.

This cohort study compares the association between preoperative cognitive status and postoperative delirium in adults undergoing major nonemergent surgery.

Introduction

Postoperative delirium, defined as delirium occurring 24 to 72 hours after surgery, is a commonly encountered condition. The incidence varies between 4% and 61%, depending on the type of surgery.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 This variation in incidence largely owes to differences in the surgical populations sampled in different studies. Less-invasive, shorter operations tend to have a lower incidence of postoperative delirium compared with longer, more-invasive procedures. For example, the incidence of postoperative delirium has been reported as 4.4% in patients who have had cataract surgery, whereas the incidence in patients who have had a hip fracture repair has been reported as 61%.1,2 Despite the known prevalence of this condition, postoperative delirium is frequently not recognized in clinical practice.8

Patients who develop delirium in the postoperative period have an increased risk of numerous poor outcomes. Patients with postoperative delirium have an 11% increase in the risk of death at 3 months, compared with those who do not develop delirium, and have up to a 17% increased risk of death at 1 year.9 Postoperative delirium is associated with increased duration of hospitalization as well as 3 times the odds of being discharged to a skilled nursing facility at hospital discharge.9,10 Other research has demonstrated that, in addition to an increased risk of mortality and hospital length of stay, delirium correlates with an increased risk of long-term cognitive impairment.

This decrease in long-term cognition has been demonstrated in elderly patients undergoing cardiac and orthopedic surgery.11,12 However, to our knowledge, these changes have not been prospectively explored in a younger, more-heterogeneous surgical population. We hypothesized that the negative outcomes of postoperative delirium on postoperative cognitive recovery would be present in a younger, more-heterogeneous population and conducted a prospective cohort study to investigate this association.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study at a single academic medical center (≥800 beds) in the southeastern United States from September 5, 2017, through January 15, 2018. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved our study protocol. Participants provided verbal informed consent; surrogate consent was obtained if the patients had cognitive impairment. Patients did not receive financial compensation.

We included all patients aged 18 years or older who spoke English and were anticipated to require at least 1 night of hospital admission after a scheduled major nonemergent surgery. Major surgical procedures were defined as those requiring at least 1 night of hospitalization after the scheduled operation. Emergent surgery was defined as an unscheduled outpatient procedure. We excluded prisoners, persons from whom we could not obtain baseline cognitive assessments, and those from whom we could not obtain informed consent. Hospitalized patients who required elective surgery were excluded as well.

We performed daily screens of the scheduled upcoming surgical procedures listed in our electronic medical records to identify patients of interest. All potential participants were contacted via telephone 24 to 72 hours before their scheduled operations. All participants were assessed for baseline cognitive function via the telephone version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (T-MoCA).13 The T-MoCA is scored on a scale of 0 to 22, with higher scores indicating better cognitive function. This validated tool provides a quick global assessment of cognition and can be readily performed via telephone. On postoperative days 1, 2, and 3, a trained researcher (C.A.A., T.O., E.S., or D.E.) assessed all patients for the presence of delirium via a form of the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), the current standard delirium clinical assessment tool.14 A structured version of the CAM that can be performed in less than 3 minutes (3D-CAM) was used for patients with verbal ability and the CAM-Intensive Care Unit tool was used for patients who were receiving mechanical ventilation or were otherwise nonverbal.15,16

We performed postoperative follow-up cognitive assessments via telephone at 30 and 90 days after discharge. We used the T-MoCA tool for these assessments to allow us to conduct comparisons with preoperative baselines. The researchers performing the T-MoCA assessments were blinded to the results of the postoperative CAM evaluation. Cognitive impairment was defined as a T-MoCA score less than 18.

Medical record reviews were conducted for all patients to record demographics, surgery type, duration of anesthesia, and preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System (ASA) scores. The ASA scores range from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating an overall healthy patient with low mortality risk and 5 indicating a moribund patient who is unlikely to survive.17 Data were collected on participant self-reported race and ethnicity because we believed there may be racial and ethnic differences in the incidence of cognitive impairment. All data were deidentified immediately and entered into a secured data management system (REDCap).

Statistical Analysis

The predetermined primary exposure variable was any delirium on postoperative days 1 to 3, and the outcome variable was change in the T-MoCA score from baseline. We conservatively estimated a postoperative delirium (exposure) prevalence of 16%. Based on this assumption, a total sample size of 132 patients (22 delirium, 110 nondelirium) would have 80% power to detect a 2-point difference in the T-MoCA score from baseline between the 2 groups assuming the common SD is 3 points, using a 2-group t test with a P < .05, 2-sided significance level. Because we anticipated some degree of participant loss to follow-up, we targeted a total of 185 patients, which would account for up to 40% loss to follow-up. Other outcome variables were analyzed as secondary outcomes.

Descriptive data were summarized using means with SD or medians with ranges for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables expressed as percentages. A χ2 analysis was used for comparison of binary variables and the t test was used for comparison of means. We applied multivariate linear regression to adjust for potential effect modifiers for our primary outcome. Our initial model included age, preoperative ASA physical status, preoperative cognitive impairment, and duration of anesthesia. We used β estimates from the final model to calculate adjusted mean change in the 90-day T-MoCA score for each delirium group. Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp), was used for all analyses.

Results

We enrolled 191 patients (110 [57.6%] women) from September 5, 2017, to January 15, 2018. The mean (SD) age was 56.8 (16.7) years. The median length of surgery was 258 minutes (range, 30-635 minutes) and mean (SD) preoperative ASA score was 2.7 (0.6). Patients with postoperative delirium were more likely to have preoperative cognitive impairment than were those without delirium (27 [45.8%] vs 27 [20.7%]), and there were more white than African American patients with delirium (41 of 59 [69.5%] vs 15 of 59 [25.4%]). Otherwise, there were minimal differences between groups, such as mean (SD) preoperative ASA score (with delirium, 2.8 [0.6] vs without delirium, 2.7 [0.6]) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 191) | Postoperative Delirium | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n = 59) | Absent (n = 132) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56.8 (16.7) | 57.9 (17.0) | 56.4 (16.6) | |

| Women, No. (%) | 110 (57.6) | 33 (55.9) | 77 (58.3) | .75 |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||

| African American | 34 (17.8) | 15 (25.4) | 19 (14.4) | .06 |

| White | 149 (78.0) | 41 (69.5) | 108 (81.8) | .11 |

| Other | 8 (4.2) | 3 (5.1) | 5 (3.8) | .92 |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 2 (1.0) | 2 (3.4) | 0 | .03 |

| Non-Hispanic | 183 (95.8) | 55 (93.2) | 128 (97.0) | .66 |

| Unknown/chose not to answer | 6 (3.1) | 2 (3.4) | 4 (3.0) | .87 |

| Preoperative cognitive impairment, No. (%) | 54 (28.3) | 27 (45.8) | 27 (20.5) | <.001 |

| Duration of anesthesia, min | Median (range), 258 (30-635) | Mean (SD), 285 (144) | Mean (SD), 256 (133) | .18 |

| Preoperative ASA score, mean (SD) | 2.7 (0.6) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.7(0.6) | .29 |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System.

The patients underwent different types of surgery; abdominal and urologic were the most common (Table 2). Most patients (144 [75.4%]) were discharged home without services. A higher proportion of patients with delirium required admission to a skilled nursing facility after discharge (6 [10.1%] vs 1 [0.8%]). Mean overall hospital length of stay was 4.4 (7.4) days. Patients with delirium had a mean 3.3-day longer duration of hospitalization (6.7 [12.0] vs 3.4 [3.6]) (Table 2). Twenty-seven patients (14.1%) required hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge.

Table 2. Surgery Information.

| Variable | No. (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 191) | Postoperative Delirium | |||

| Present (n = 59) | Absent (n = 132) | |||

| Surgery class | ||||

| Abdominal | 42 (22.0) | 9 (15.3) | 33 (25.0) | .15 |

| Cardiac | 9 (4.7) | 5 (8.5) | 4 (3.0) | .09 |

| Ear, nose, and throat | 14 (7.3) | 2 (3.4) | 12 (9.1) | .17 |

| Gynecology | 13 (6.8) | 1 (1.7) | 12 (9.1) | .07 |

| Neurosurgery | 20 (10.5) | 9 (15.3) | 11 (8.3) | .13 |

| Orthopedics | 20 (10.5) | 9 (15.3) | 11 (8.3) | .13 |

| Plastics | 9 (4.7) | 2 (3.4) | 7 (5.3) | .58 |

| Surgical oncology | 8 (4.2) | 4 (6.8) | 4 (3.0) | .22 |

| Thoracic | 11 (5.8) | 2 (3.4) | 9 (6.8) | .36 |

| Oral and maxillofacial surgery | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | .35 |

| Urology | 35 (18.3) | 11 (18.6) | 24 (18.2) | .89 |

| Vascular | 8 (4.2) | 5 (8.5) | 3 (2.3) | .04 |

| Hospital length of stay, mean (SD), d | 4.4 (7.4) | 6.7 (12.0) | 3.4 (3.6) | |

| Discharge disposition, No. (%) | ||||

| Home without services | 144 (75.2) | 38 (64.4) | 106 (80.3) | .003 |

| Home with physical therapy and/or home health | 38 (19.9) | 14 (23.7) | 24 (18.2) | .49 |

| Skilled nursing facility | 7 (3.8) | 6 (10.1) | 1 (0.8) | .001 |

| Long-term acute care or hospice | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (0.8) | .55 |

Thirty-five patients (18.3%) were delirious on postoperative day (POD) 1. Of these, 5 patients (14.3%) were discharged at that time. Thirty-one (21.4% of the remaining 145 patients) were delirious on POD 2, and 6 of these patients (19.4%) were discharged while delirious. Of the 31 cases observed on POD 2, 13 patients (41.9%) also had been delirious on POD 1 and 18 of the cases (58.1%) were new.

Twenty-one (19.3% of the remaining 109 patients) were delirious on POD 3, and 4 of them (19.0%) were discharged with active delirium. Of these 21 cases, 7 patients (33.3%) were delirious on POD 1 or 2 and 14 patients (66.7%) represented new cases. All patients discharged while delirious on POD 1, 2, or 3 were discharged home. Fifty-nine (30.9% of all participants) were delirious on POD 1, 2, or 3 (Table 3).

Table 3. Cognitive Assessment Results.

| Variable | Overall Sample (N = 191) | Preoperative Cognitive Impairment | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n = 55) | Absent (n = 136) | |||

| CAM positive, No. (%) | ||||

| POD 1 | 35 (18.3) | 18/55 (32.7) | 17 (12.5) | .001 |

| POD 2 | 31 (21.2) | 12/44 (27.3) | 19/102 (18.6) | .24 |

| POD 3 | 21 (19.3) | 10/35 (28.6) | 11/74 (14.9) | .09 |

| POD 1, 2, or 3 | 59 (30.9) | 27 (49.1) | 32 (23.5) | <.001 |

| T-MoCA score, mean (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | 18.2 (3.1) | 16.8 (3.8) | 18.8 (2.6) | <.001 |

| 30 d | 18.6 (2.8) | 17.3 (3.4) | 19.1 (2.4) | <.001 |

| 90 d | 18.8 (3.1) | 17.1 (3.5) | 19.3 (2.7) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; POD, postoperative day; T-MoCA, telephone version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

The mean (SD) baseline preoperative T-MoCA score was 18.2 (3.1). We completed 30-day T-MoCA assessments on 131 of all patients (68.6%). Of the other patients, we were unable to contact 51 (26.7%), 6 (3.1%) declined further assessment, 3 (1.6%) were unable to verbalize and therefore not assessable, and 1 (0.5%) was not assessable for other reasons. The mean 30-day postoperative T-MoCA score was 18.6 (2.8) (Table 3).

We completed 90-day T-MoCA assessments on 135 of all patients (70.7%). Of the other patients, we were unable to contact 35 (18.3%), 12 (6.3%) refused assessment, 5 (2.6%) were unable to verbalize, 3 (1.6%) were not assessable for other reasons, and 1 (0.5%) had died (Figure). The mean 90-day postoperative T-MoCA score was 18.8 (3.1) (Table 3).

Figure. Enrollment and Follow-up.

CAM indicates Confusion Assessment Method; T-MoCA, telephone-administered Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

30-Day Follow-up Assessments

Patients with and without delirium had a small increase in T-MoCA scores at 30 days compared with baseline on unadjusted analysis (without delirium, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.18-1.10 vs with delirium, 0.33; 95% CI, −0.64 to 1.31) (Table 4). When stratifying by preoperative cognitive impairment, we found that patients without baseline cognitive impairment who developed delirium had a 0.87-point decrease in 30-day T-MoCA scores (without delirium, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.36-1.23 vs with delirium, −0.07; 95% CI, −0.78 to 0.64). We found that patients with preoperative cognitive impairment had an increase in cognitive performance at 30 days, but this increase was attenuated if the patient was delirious in the postoperative period (without delirium, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.36-1.23 vs with delirium, −0.07; 95% CI, −0.78 to 0.64) (Table 4).

Table 4. Change in T-MoCA Scores.

| Postoperative Delirium | 30-d Change in T-MoCA | 90-d Change in T-MoCA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted (95% CI) | Adjusted (95% CI)a | Unadjusted (95% CI) | Adjusted (95% CI)a | |

| Present (n = 36) | 0.33 (−0.64 to 1.31) | −0.07 (−0.78 to 0.64) | 0.69 (−0.34 to 1.73) | 0.16 (−0.63 to 0.94) |

| Absent (n = 95) | 0.64 (0.18-1.10) | 0.79 (0.36-1.23) | 0.67 (0.17-1.16) | 0.86 (0.40-1.33) |

Abbreviation: T-MoCA, telephone version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

Adjusted for preoperative cognitive impairment via linear regression.

Primary Outcome

For our primary outcome of interest, both patients with and without delirium had a small increase in T-MoCA scores at 90 days compared with baseline on unadjusted analysis (with delirium, 0.69; 95% CI, −0.34 to 1.73 vs without delirium, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.17-1.16) (Table 4).

Our initial multivariate linear regression model included age, preoperative ASA score, preoperative cognitive impairment, and duration of anesthesia. There was no significant difference in our outcome of interest when stratified by age; patients aged 65 years and older had a 0.15-point increase in T-MOCA from baseline compared with those younger than 65 years (95% CI, −0.65 to 0.96). Preoperative cognitive impairment proved to be the only notable confounder. When adjusted for preoperative cognitive impairment, patients with delirium had a 0.70-point greater decrease in 90-day T-MoCA scores than those without delirium compared with their respective baseline scores (with delirium, 0.16; 95% CI, −0.63 to 0.94 vs without delirium, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.40-1.33) (Table 4).

Patients with baseline cognitive impairment had an increase in cognition at 90 days, but this increase was attenuated if they were delirious in the postoperative period. Patients with preoperative cognitive impairment who were not delirious had an increase in their T-MoCA score from baseline of 2.77 points, whereas those who were delirious had an increase of 2.07 points (difference, 0.7 points; 95% CI, −1.64 to 0.23).

We performed secondary analyses assessing the association of longer duration of delirium (ie, delirium present on POD 1, 2, and 3) and change in cognitive function at 90 days after surgery. Patients who were delirious on only 1 day had an unadjusted decrease in their T-MoCA score of 0.15 points (95% CI, CI, −1.34 to 1.05; P = .81). If patients had delirium on 2 of the 3 days observed, the decrease in T-MoCA increased to 0.23 points (95% CI, −1.72 to 1.26; P = .76). Those who were delirious on all 3 days had a decrease of 0.96 points (95% CI, −3.08 to 1.17; P = .37).

Discussion

This prospective cohort study reveals multiple observations. Postoperative delirium had a negative association with 30- and 90-day cognition in all participants. Those with preoperative cognitive impairment appeared to have an improvement in cognition at 30 and 90 days after major nonemergent surgery. However, this increase was attenuated if the patient experienced postoperative delirium. Those with delirium on multiple days had a greater decrease in cognition at 90 days compared with those with delirium only for 1 day. There was no difference in our outcome of interest when stratified by age indicating that this is an age-independent process. Furthermore, a considerable number of patients were discharged home while delirious.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the association between postoperative delirium and change in cognitive function from baseline in a broad, heterogeneous surgical population. Prior research has evaluated select surgical populations and demonstrated that patients are at increased risk of long-term cognitive decline if they are delirious after surgery. Saczynski et al11 studied elderly patients undergoing major cardiac surgery and found that, compared with those who did not develop delirium, patients with delirium had a 2-point decrease in mean Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores at 1 year after surgery. Witlox et al12 studied elderly patients undergoing surgical hip fracture repair. They noted an increase in Mini-Mental State Examination scores at 3 months if patients did not have postoperative delirium, but found no change in those who were delirious. Inouye et al18 examined patients aged 70 years or older undergoing major surgery and found that postoperative delirium was associated with cognitive decline that persisted up to 36 months after surgery.

Our findings suggest that postoperative delirium has a negative association with the cognitive function of all adult patients that may persist up to 3 months after surgery. This finding agrees with the results seen in other, more elderly surgical samples. Our findings indicate that delirium has a negative association with cognition that is independent of age. We also observed that patients were discharged home while delirious. Given the negative cognitive effects of delirium, evaluation of the result of this condition on day-to-day function after discharge home (eg, driving, returning to work) would be valuable in guiding clinicians and formulating safe discharge plans. However, to our knowledge, this aspect has not been evaluated to date and warrants future exploration.

Our data indicate that patients with preoperative cognitive impairment are more likely to become delirious. This finding aligns with the results of prior research.19 In addition, our data suggest that patients with preoperative cognitive impairment have an improvement in cognition after surgery, but this improvement was not as great if the patient developed postoperative delirium. This observed improvement can be partly be explained by regression to the mean or by a component of learning effects with repeat T-MoCA assessments.20 Alternatively, the improvement suggests that, in some patients, the acute condition that required surgery had a negative effect on preoperative cognitive function likely owing to associated pain or narcotic medications, and those with cognitive impairment may derive additional benefits beyond the immediate expected surgical benefits.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include some degree of loss to follow-up despite our efforts to assess all participants. It is likely that some of the patients that we were unable to reach had decreased cognition that may have precluded them from being assessed via telephone. Assuming nondifferential misclassification, this lack of assessment would tend to bias our results toward observing no difference and, therefore, the association between postoperative delirium and cognition may be greater than what we observed.

We assessed patients for delirium only on PODs 1 to 3. It is possible that some individuals developed delirium after this period. However, we wished to limit the study to the outcome of postoperative delirium. Any delirium that developed after POD 3 was likely attributable to another cause and, although important, not fully pertinent to the present study. In addition, the study was conducted at a single academic, tertiary medical center, and results may not be generalizable to other settings. However, our results align with prior findings from other, more elderly patient populations.

Conclusions

Postoperative delirium has a persistent negative association with cognitive function 3 months after surgery in a heterogeneous population of patients undergoing major nonemergent surgery. Future preventions and/or treatments for postoperative delirium should therefore be directed toward all adult surgical patients. Given the prevalence and detrimental effects of delirium, all postoperative patients should have routine assessment for this condition. Those with preoperative cognitive impairment appear to have improvement in cognition after surgery, but this may be attenuated if they become delirious.

Cognitive impairment alone should not preclude patients from undergoing indicated surgery. Many patients with postoperative delirium are discharged from the hospital while delirious. Further research into the clinical effect of delirium persistent to time of discharge home is needed.

References

- 1.Milstein A, Pollack A, Kleinman G, Barak Y. Confusion/delirium following cataract surgery: an incidence study of 1-year duration. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(3):301-306. doi: 10.1017/S1041610202008499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gustafson Y, Berggren D, Brännström B, et al. Acute confusional states in elderly patients treated for femoral neck fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36(6):525-530. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04023.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scholz AF, Oldroyd C, McCarthy K, Quinn TJ, Hewitt J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for postoperative delirium among older patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. 2016;103(2):e21-e28. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider F, Böhner H, Habel U, et al. Risk factors for postoperative delirium in vascular surgery. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(1):28-34. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(01)00168-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Böhner H, Hummel TC, Habel U, et al. Predicting delirium after vascular surgery: a model based on pre- and intraoperative data. Ann Surg. 2003;238(1):149-156. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000077920.38307.5f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2):134-139. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510260066030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Levkoff SE, et al. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;119(2):229-236. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.795260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Cruz M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2610-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raats JW, van Eijsden WA, Crolla RM, Steyerberg EW, van der Laan L. Risk factors and outcomes for postoperative delirium after major surgery in elderly patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443-451. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, et al. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):30-39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witlox J, Slor CJ, Jansen RW, et al. The neuropsychological sequelae of delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture three months after hospital discharge. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(9):1521-1531. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zietemann V, Kopczak A, Müller C, Wollenweber FA, Dichgans M. Validation of the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status and Telephone Montreal Cognitive assessment against detailed cognitive testing and clinical diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment after stroke. Stroke. 2017;48(11):2952-2957. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method: a new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703-2710. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcantonio ER, Ngo LH, O’Connor M, et al. 3D-CAM: derivation and validation of a 3-minute diagnostic interview for CAM-defined delirium: a cross-sectional diagnostic test study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):554-561. doi: 10.7326/M14-0865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owens WD, Felts JA, Spitznagel EL Jr. ASA physical status classifications: a study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology. 1978;49(4):239-243. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197810000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inouye SK, Marcantonio ER, Kosar CM, et al. The short-term and long-term relationship between delirium and cognitive trajectory in older surgical patients. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(7):766-775. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Culley DJ, Flaherty D, Fahey MC, et al. Poor performance on a preoperative cognitive screening test predicts postoperative complications in older orthopedic surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(5):765-774. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heilbronner RL, Sweet JJ, Attix DK, Krull KR, Henry GK, Hart RP. Official position of the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology on serial neuropsychological assessments: the utility and challenges of repeat test administrations in clinical and forensic contexts. Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;24(8):1267-1278. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2010.526785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]