Abstract

Animal models play an important role in understanding the mechanisms of bacterial pathogenesis. Here we review recent studies of Salmonella infection in various animal models. Although mice are a classic animal model for Salmonella, mice do not normally get diarrhea, raising the question of how well the model represents normal human infection. However, pretreatment of mice with oral streptomycin, which apparently reduces the normal microbiota, leads to an inflammatory diarrheal response upon oral infection with Salmonella. This has led to a re-evaluation of the role of various Salmonella virulence factors in colonization of the intestine and induction of diarrhea. Indeed, it is now clear that Salmonella purposefully induces inflammation, which leads to the production of both carbon sources and terminal electron acceptors by the host that allow Salmonella to outgrow the normal intestinal microbiota. Overall use of this modified mouse model provides a more nuanced understanding of Salmonella intestinal infection in the context of the microbiota with implications for the ability to predict human risk.

Keywords: virulence, microbiota, antibiotic-induced dysbiosis, inflammation, Altered Schaedler Flora

INTRODUCTION

Our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of Salmonella infection and pathogenesis has been dependent on good animal models. Here we focus on the mechanisms of Salmonella infection gleaned from using the traditional mouse model versus the streptomycin-treated mouse model and other animal systems, and compare these findings with what is known about human infections.

Salmonellosis in humans.

Non-typhoidal Salmonella serovars are some of the most common bacterial pathogens in the world, estimated to cause over one million foodborne illnesses per year in the US (Scallan et al. 2011) and 94 million cases per year worldwide (Majowicz et al. 2010). Typically, Salmonella causes self-limiting gastroenteritis, but in the very young, elderly or otherwise immunocompromised patients can cause a disseminated systemic infection, septicemia, and death. Certain strains of Salmonella, so-called invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella (iNTS), are adept at causing systemic disease and are of particular concern in HIV-infected adults and in HIV- or Malaria-infected and malnourished children in sub-Saharan Africa (Feasey et al. 2012).

Most cases of salmonellosis are caused by consumption of contaminated food, including chicken, pork, or eggs, but infections are increasing occurring from contaminated fruits, nuts, or vegetables (Painter et al. 2013). Of the confirmed cases, only 6% are associated with outbreaks (CDC 2014). Dose response modeling of Salmonella outbreaks suggests an illness ID50 of 36 colony forming units (Blaser and Newman 1982, Boring et al. 1971, D’Aoust 1985, Hennessy et al. 1996, Teunis et al. 2010; Coleman et al., Marks and Coleman, companion papers in this collection). The dose-response relationship depends on multiple factors, including the mode of inoculation, the immune competency of the host, and, as is increasingly appreciated, the intestinal microbiota at the time of infection. Dietert has termed this human/microbiota consortium as the “superorganism” (Dietart, companion paper in this collection).

The first bottleneck that affects Salmonella infectivity is the stomach, which has digestive enzymes and a pH as low as 1.5 (Smith 2003). The stomach also contains high concentrations of weak acids which can act as uncouplers of proton motive force. Increasing the pH of the gastric juice using antacids or proton pump inhibitors increases the susceptibility to infection from a variety of oral pathogens, including Salmonella (Bavishi and Dupont 2011). Food also protects pathogens in complex ways as they pass through the stomach (Blaser and Newman 1982), either by directly blocking or shielding the organisms from acid, or perhaps by affecting virulence gene expression in the bacteria.

In otherwise healthy individuals, non-typhoid Salmonella strains cause what is termed self-limiting gastroenteritis with symptoms of watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, and fever. The extent of diarrhea is variable; a limited number of patients will experience profuse “cholera-like” diarrhea, while in other cases the stools can be more dysentery-like with blood and mucus. Headache, myalgia and fever are also common. Although clearly invasive, the infection is usually limited to the intestine and underlying tissue. Indeed, most people with acute salmonellosis never go to the doctor and are not formally diagnosed or examined and data on the intestinal pathology of otherwise healthy individuals is extremely limited. Rather, pathological examinations have been primarily restricted to biopsies in patients with prolonged diarrhea or excised tissue taken on autopsy from patients who died from Salmonella infection (Boyd 1985, Coburn et al. 2007a, Lamps 2007, McGovern and Slavutin 1979). These data suggest that non-typhoid Salmonella infection induces primarily colitis, with neutrophil infiltration in the crypt epithelium and the lamina propriae. There is some involvement of the appendix, whereas the distal ilium seems to be involved in only some patients. Experimental infections in rhesus monkeys showed very similar histological appearance (Kent et al. 1966). Thus, acute self-limiting infectious colitis is a better term to describe salmonellosis (Lamps 2007).

Infection in the traditional mouse model.

There are over 2000 serovars of Salmonella enterica that differ in their surface antigen structures, their host range, and their disease causing abilities (Ellermeier and Slauch 2006). The term “Typhimurium” literally means “Typhi of mice” and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (abbreviated Salmonella Typhimurium) can be naturally found and isolated from rodents (Hardy 2015). While Salmonella Typhi, for example, is a human specific pathogen, Salmonella Typhimurium is a generalist, capable of infecting a wide range of animals. Strains of Salmonella Typhimurium are one of the leading causes of salmonellosis worldwide (Ao et al. 2015) and Salmonella Typhimurium strain LT2 is considered the “type strain” for the species (Ellermeier and Slauch 2006). The use of mice as a natural host and the ability to genetically manipulate both the bacterium and the mouse has provided tremendous insight into the molecular pathogenesis of Salmonella Typhimurium. The only limitation is that this is a model for typhoid-like enteric fever and not gastrointestinal disease, as discussed below.

As outlined above, the stomach serves as an important barrier to infection. Enteric bacteria, including Salmonella, can activate what is termed the Acid Tolerance Response (ATR); treatment at moderately low pH induces systems that allow survival at yet lower pH. The ATR is composed of acid shock proteins, which are synthesized to prevent and repair damage to proteins (Audia et al. 2001), proton-sodium and potassium-proton anti-porters to export excess protons in the cytoplasm, as well as lysine and arginine decarboxylases, which, upon significant overexpression, can apparently consume protons and regulate intracellular pH (Ryan et al. 2015). The phenomenon has been extensively studied in vitro. Higher levels of acid tolerance have been associated with more highly virulent S. Typhimurium DT104 strains (Berk et al. 2005) and acid adaptation helped S. Typhimurium survive in pH 1.5 simulated gastric fluid in vitro (Perez et al. 2010). Stress and pathogenicity-related regulatory systems assist in coping with acid stress. The RpoS and Fur regulons protect against organic acid stress induced by weak acids (Baik et al. 1996), while the PhoP and RpoS regulons protect against inorganic acid stress or low pH (Bearson et al. 1998). Despite extensive in vitro analyses of these phenomena, the role of these systems in vivo is not well understood. The identified regulatory systems control multiple virulence genes in addition to those involved in acid tolerance. Thus, it is difficult to determine the specific role of acid tolerance in pathogenesis. Indeed, there is no definitive evidence that this response of Salmonella aids passage through the stomach. There are likely multiple systems that have been identified. For example, the PhoP-mediated response is far more likely to be critical in the macrophage phagosome than in the lumen of the stomach (Kato and Groisman 2008). It might also be that passage through the stomach induces some of these systems, which then facilitate survival lower in the intestine (Angelichio et al. 2004). It is important to note that most animal experiments and many human volunteer studies (Kothary and Babu 2001) involve buffering the stomach contents during oral inoculation. Although buffering the stomach acid increases susceptibility to infection, it does not immediately follow that the in vitro identified systems are critical under normal conditions.

In the traditional mouse model, the primary site of intestinal invasion is the most distal Peyer’s patch in the terminal ileum (Carter and Collins 1974, Jones et al. 1994). Specifically, the bacteria target the M-cells, specially differentiated epithelial cells that overly the dome of these lymphoid follicles. M cells have several properties that presumably make them particularly good targets for initial intestinal invasion. They have reduced microvilli as well as different glycocalyx and reduced mucus covering, owing to limited goblet cells in the area. Salmonella interact with M cells via long polar fimbriae (lpf), one of 14 different fimbriae encoded in the S. Typhimurium chromosome (Baumler et al. 1996). This also provides some specificity for attachment. Salmonella cells can be seen specifically interacting with M cells within 90 mins of oral infection of mice (unpublished).

Salmonella induces invasion of the M cells using a Type Three Secretion System (T3SS) encoded on the Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 1 (SPI-1). This needle-like complex allows the direct injection of bacteria proteins, termed effectors, into the epithelial cell cytoplasm. Greater than 10 different bacterial proteins are injected. These effectors cause actin rearrangement, which leads to engulfment of the bacteria and, independently, induction of the NF-kB pathway leading to an inflammatory response. The mechanisms of action for specific effectors is reviewed elsewhere (Coburn et al. 2007b, Haraga et al. 2008, LaRock et al. 2015, McGhie et al. 2009).

There are likely several mechanisms by which Salmonella cells target the most distal Peyer’ patch as the primary site of infection. First, flow through the small intestine is apparently rapid, making it difficult for bacteria to colonize the upper intestine. This flow slows considerably at the distal small intestine prior to ileocecal valve. Second, the M cells themselves are more accessible to the bacteria and the initial attachment is likely somewhat specific for these cells, as mentioned above. Third, the SPI1 T3SS is regulated in response to specific location-dependent signals.

The SPI1 T3SS is tightly regulated in response to a wide array of environmental parameters. Expression of the T3SS causes a growth defect to Salmonella cells (Sturm et al. 2011). Therefore, it is thought that the system is expressed only at the appropriate time and place for invasion, presumably the distal small intestine. Numerous environmental cues are integrated to control expression of the system (Golubeva et al. 2012). Examples include both short- and long-chain fatty acids. Long-chain dietary free fatty acids are transported into the bacterial cell where they directly bind to a primary transcriptional regulator of SPI1 to block activation of the system (Golubeva et al. 2016). Importantly, this regulatory effect is independent of the ability of Salmonella to use long chain fatty acids as a carbon and energy source. The concentration of dietary fatty acids should decrease along the small intestine as they are absorbed into the body (Carey et al. 1983, Stahl et al. 1999). The short chain fatty acids acetate, formate, propionate, and butyrate, also affect SPI1 expression, but each do so by very different mechanisms. Acetate and formate, which activate expression of the system (Golubeva et al. 2012, Huang et al. 2008, Lawhon et al. 2002, Martinez et al. 2011), are at their highest concentration in the distal ileum (Garner et al. 2009). Propionate and butyrate, which negatively affect expression (Gantois et al. 2006, Golubeva et al. 2016, Hung et al. 2013), are produced as fermentation products by the bacteria in the large intestine. Butyrate, like long chain fatty acids, seems to act solely as a signal; Salmonella cannot use butyrate as a carbon source (Gutnick et al. 1969). Thus it is in the distal ileum where the negative acting fatty acids are at their lowest concentration, while the positive acting fatty acids are at their highest concentration. Integration of these signals presumably helps to define the optimal location for expression of the SPI1system. Although these are just some of the signals being sensed by the bacteria, they have real significance when thinking about infection. The long-chain fatty acids are clearly coming from food (Golubeva et al. 2016), and this would apparently have implications dependent on the source of Salmonella contamination. Moreover, the short-chain fatty acid signals are coming from other intestinal bacteria, implying that one way in which the status of the intestinal microbiota could affect Salmonella infection is by altering regulation of virulence gene expression (see below). It follows that variation in the microbiota between individuals could also affect the infectivity of an incoming Salmonella cell.

Systemic infection

The bacterial cells traverse the M cells and are taken up by macrophages and/or dendritic cells that are found in the upper dome of the Peyer’s patch, underlying the M cells (Hopkins and Kraehenbuhl 1997, Hopkins et al. 2000). Although these cells are naturally phagocytic, engulfment of a Salmonella cell that is expressing the SPI1 T3SS leads to a Caspase-1- mediated cell death termed pyroptosis in these phagocytes (Brennan and Cookson 2000, Fink and Cookson 2007, Watson et al. 2000). This is an inflammatory signal and inflammation and destruction of some cells in the Peyer’s patch is a hallmark of infection in the mouse (Jones et al. 1994) as well as S. Typhi infection in humans (Kohbata et al. 1986, Kraus et al. 1999). This is apparently an important step in Salmonella pathogenesis as evidenced by the fact that caspase 1-deficient mice are significantly more resistant to infection (Monack et al. 2000).

The Salmonella cells can spread systemically from the Peyer’s patch, likely to the draining lymph nodes, and subsequently to all tissues. It is not clear if the bacteria can spread as free cells or are carried by phagocytic cells throughout the body. Evidence certainly suggests that the vast majority of viable Salmonella in systemic tissues are found within macrophages and these cells constitute the primary sites of Salmonella replication (Mastroeni et al. 2009). However, the data also show that the macrophages contain less than 10 bacterial cells, suggesting that bacteria replicate only a few times in a given cell. How those bacteria get out of one macrophage into new cells is not understood. It is also clear that not all phagocytes are equivalent. Neutrophils likely kill Salmonella efficiently via production of large concentrations of hydrogen peroxide and/or hypochlorite (Burton et al. 2014). Highly activated so-called Th1 macrophages also seem capable of killing Salmonella. Th2 macrophages, which play a role in tissue repair, are the more likely reservoir. The reservoir could be even narrower, as Detweiler and associates have data suggesting that a subset of macrophages, the hemophagocytic macrophages, which have phagocytized decrepit red blood cells, are the primary replicative niche for Salmonella, at least during persistent systemic infection (Nix et al. 2007). Of course replicating in these less lethal phagocytic cells protects the Salmonella from other more effective phagocytes, as well as complement and the humoral immune response. In susceptible mouse strains, the bacteria continue to replicate, infecting all tissues in the body, eventually leading to overwhelming septic shock and death.

Replication of Salmonella in macrophages has been well-studied. The Salmonella-containing vacuole initially acidifies to pH 4–5 (Rathman et al. 1996). This drop in pH and other environmental parameters in the vacuole signal the bacterium to alter gene expression and induce numerous key virulence systems. The PhoPQ two-component regulatory system in induced, leading to the production of numerous factors important for survival in this harsh environment (Alpuche-Aranda et al. 1994, Alpuche Aranda et al. 1992, Garvis et al. 2001). These include enzymes that modify the outer membrane lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to make it resistant the anti-microbial peptides produced by the macrophage (Groisman and Aspedon 1997, Gunn et al. 1998, Guo et al. 1997), as well as a periplasmic superoxide dismutase that counteracts the phagocytic superoxide produced at high concentrations in the phagosome (Golubeva and Slauch 2006). The SPI1 T3SS is shut down under these conditions and, and partially via PhoPQ, a completely separate second T3SS, encoded on Salmonella pathogenicity island 2, is induced. This complex injects proteins across the phagosomal membrane into the macrophage cytoplasm. At least 20 different effector proteins have a number of interesting functions that include alterations in vesicular trafficking to maturing phagosome (Bakowski et al. 2008, Haraga et al. 2008). These alterations in delivery result in the so-called “Salmonella containing vacuole”, which is somewhat unique with respect to the various cellular proteins present and, therefore, the vacuolar environment. The Salmonella then replicate in this altered vesicle.

A critical factor that affects macrophage survival is the NRAMP1 (SLC11A1) metal transport system. NRAMP1 is a phagosomal membrane protein that reportedly transports iron, although there is significantly controversy regarding even the direction of iron transport, let alone the ultimate role in innate immunity (Wessling-Resnick 2015). This factor has been genetically recognized for decades as affecting survival of intracellular pathogens and was previously designated ity, lsh, or bcg, because mice homozygous for this allele show increased sensitivity to Salmonella, Leishmania and the Mycobacterium Bcg vaccine strain, respectively (Vidal et al. 1995). NRAMP1−/− background mice, such as BALB/c or C57BL/6, die within days from an overwhelming systemic Salmonella infection, whereas NRAMP+/+ strains, such as 129 or C3H/HeJ, get “persistent” infections in which viable Salmonella can be recovered from tissues for up to 1 year, despite lack of any apparent disease (Monack et al. 2004). Genetic polymorphism in the NRAMP locus in humans also affects susceptibility to various infections (Blackwell et al. 2003).

The ability of Salmonella to survive in macrophages leads to a lethal infection in sensitive strains of mice. The seriousness of this systemic stage of disease is also reflected in human salmonellosis. The very young, old, or otherwise immunocompromised individuals are particularly sensitive to systemic infection and non-typhoid Salmonella is estimated to be a leading cause of death among the food-borne pathogens in the US because of this ability to cause systemic infection in some individuals (Scallan et al. 2011). Salmonella Typhi and Paratyphi strains are adapted to and more adept at surviving in human macrophages; the balance is shifted and these organisms cause enteric fever in otherwise healthy individuals.

Events in the intestine in normal and streptomycin-treated mice

There is no evidence that Salmonella must replicate prior to invasion of the intestinal epithelium or indeed, in the classic mouse model, that Salmonella replicates in the lumen of the intestine at all. First, initial interaction with the M cells of the distal Peyer’s patch is relatively rapid, with transit and binding within 90 minutes (unpublished). Although this does not preclude replication before invasion, it certainly limits it to one or two divisions at most. Second, the oral LD 50 in mice is ~10^5 cells. In contrast, if the intestine is bypassed by injected the bacteria intraperitoneally, the LD 50 is <10 organisms (Stocker et al. 1983). This suggests that most of bacteria acquired orally pass through the intestine without ever invading and certainly precludes a model in which a limited number of organisms can replicate to high numbers and then invade. Third, one of the most compelling arguments is the fact that a mutant Salmonella that is incapable of replicating in the absence of oxygen is fully virulent in the classic mouse model (Craig et al. 2013). Although this might not preclude one or two rounds of replication in the upper small intestine, the bacteria are certainly not replicating in the anaerobic large intestine. This does not mean that Salmonella is not viable in the large intestine, it is just not replicating. The simplest model to explain these data is that Salmonella simply traverses the small intestine. A limited number of the bacteria interact with and invade the M cells of the Peyer’s patch. Subsequent replication of the bacteria is within the intestinal tissue (which is oxygenated). In addition to spreading systemically, organisms are shed into the lumen of the intestine. They do not replicate in the lumen, but rather are simply excreted in the stool. Bacteria replicating in the liver are also shed into the intestine via the gall bladder. Although some of these organisms can reinvade, most likely pass through and are excreted.

Although much has been learned from the traditional mouse model of Salmonella infection, it is a model for typhoid/enteric fever rather than gastroenteritis. Mice do not normally get diarrhea, which has limited our understanding of the most common form of salmonellosis. More in-depth understanding of the gastrointestinal symptoms resulting from Salmonella infection has been investigated using cattle (Santos et al. 2001, Tsolis et al. 1999), but these experiments are limited by the need for specialized facilities and their expense. More recently, investigators have taken advantage of an old observation (Bohnhoff et al. 1954, 1955, Bohnhoff and Miller 1962, Miller et al. 1956) that treatment of mice with antibiotics, most commonly oral streptomycin, apparently affects the intestinal microbiota. Subsequent oral infection with Salmonella leads to an inflammatory diarrhea (Barthel et al. 2003, Que and Hentges 1985).

Experimentally, mice are given a single 20 mg dose of streptomycin orally 24 hours before oral infection with Salmonella. This lowers the ID50 at least 5 logs to less than 10 bacteria (Bohnhoff and Miller 1962), although much higher doses are used in the recent studies. Salmonella infection in the treated mice induces significant inflammation of the cecum, slightly less inflammation in the colon, and mild inflammation in the distal ileum, as determined by histological analyses, which showed edema of the submucosa and lamina propria, and infiltration of neutrophils into the tissue of intestinal lumen (Barthel et al. 2003). This inflammatory response is dependent on the SPI1 T3SS, but is apparently independent of the organized intestinal lymphoid tissue, such as Peyer’s patches, since mice that genetically lack these structures gets colitis upon infection (Barthel et al. 2003). The second Salmonella T3SS, encoded on SPI2 is also involved in intestinal inflammation and survival (Coburn et al. 2005, Coombes et al. 2005, Hapfelmeier et al. 2005) and the SPI1 and SPI2 systems are coordinately regulated under certain conditions (Bustamante et al. 2008)

Studies using this infection model have led to a re-evaluation of the inflammatory diarrhea induced upon infection. Simplistically, it was assumed that the immune system somehow knew that Salmonella was a pathogen, distinct from the normal intestinal microflora, and that the inflammatory response was induced by the host to fight the infection. It is now clear that Salmonella is purposefully inducing inflammation, via injection of proteins by the T3SS. These include specific effectors that lead to induction of the NfkB pathway (Keestra et al. 2011), as well as immune detection of both flagellin and the T3SS per se (Crowley et al. 2016, Sellin et al. 2015, Winter et al. 2009).

Salmonella benefits from the inflammatory response by taking advantage of newly available carbon sources and terminal electron acceptors. Inflammation results in increased production of mucin, which contains high-energy glyco-conjugates and amino acids that can be used as carbon sources for Salmonella (Stecher and Hardt 2008). Additionally, there is an influx of neutrophils into the lumen of the intestine that produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which react with available thiosulfate to generate tetrathionate (S4O62-), a terminal electron acceptor that can be utilized by only a limited group of bacteria including Salmonella. (Winter et al. 2010). Salmonella can also use nitrate, a byproduct of the inflammatory response, for respiration (Winter et al. 2013). These new electron acceptors presumably allow Salmonella to metabolize ethanolamine and propanediol, non-fermentable compounds present in the intestine, as carbon and energy sources (Faber et al. 2017, Thiennimitr et al. 2011). Thus, during intestinal inflammation, Salmonella can respire using tetrathionate and nitrate, it has access to increased carbon sources including non-fermentable ethanolamine and propanediol and can, therefore, out-compete fermenting bacteria (Clark and Barrett 1987, Lopez et al. 2012).

Chemotaxis is a known virulence factor in a wide range of pathogens, allowing the bacteria to optimize the acquisition of nutrients, avoid toxic substances, and/or move to ideal sites of infection (Ottemann and Miller 1997). For Salmonella, chemotaxis is required for full virulence during oral infection. Originally thought to increase the number of encounters between host and bacterial cells (Khoramian-Falsafi et al. 1990), recent work has suggested chemotaxis plays a role in moving towards a more ideal metabolic niche. Salmonella lacking a functional cheY (chemotaxis) or fla (flagellar assembly) are attenuated in the streptomycin pretreated mouse, but only in the presence of inflammation (Stecher et al. 2008) supporting the concept that inflammation provides favorable niche for Salmonella replication. The three methyl accepting chemotaxis proteins, Trg, Tsr, and Aer appear to be relevant chemotaxis sensors in the host, sensing galactose and ribose, nitrate, and tetrathionate respectively (Rivera-Chavez et al. 2013). Data suggest that Salmonella utilizes chemotaxis in the gut to situate itself near high energy compounds provided by mucin, as well as electron acceptors that allow for anaerobic growth and a growth benefit.

In the streptomycin-treated mice, the primary site of Salmonella replication is apparently in intestinal epithelial cells. Sellin et al. (2014) have shown that, after oral infection with >107 colony forming units, the cecum is colonized by 2–6 hrs with inflammation evident by 8 hrs. The data suggest that bacteria invade the intestinal epithelial cells and replicate primarily within membrane-bound vacuoles. Consistent results are seen in a calf ileal loop model of infection (Laughlin et al. 2014). Infection of the epithelial cells apparently leads to activation of the NLRC4 inflammasome and caspase 1 via detection of flagella and/or the T3SS needle complex (Sellin et al. 2015). In response, the epithelial cells are extruded into the lumen and undergo pyroptosis, a pro-inflammatory cell death (Knodler et al. 2014a, Knodler et al. 2010). This establishes a situation where Salmonella are invading and replicating but the epithelial cells extrude, tempering the bacterial replication (Sellin et al. 2014). In mice lacking components of the inflammasome, mucosal pathogen loads are increased 100–1000 fold (Nordlander et al. 2014, Sellin et al. 2014). Evidence also suggests that in a small fraction of epithelial cells, the Salmonella break out of the vacuole and replicate to high numbers within the host cell cytoplasm (Knodler et al. 2014b, Knodler et al. 2010). Although this apparently occurs in only a small fraction of the cells, because of the increased proliferation, these bacteria could represent the majority of total Salmonella cells (Knodler et al. 2014b). Moreover, these cytoplasmic bacteria are expressing flagella and the SPI1 T3SS, so they primed for re-invasion (Knodler 2015).

Oral streptomycin clearly affects the normal microbiota of the intestine (Garner et al. 2009). But how does this actually increase susceptibility to infection by Salmonella or other intestinal pathogens? Several non-mutually exclusive mechanisms have been proposed to explain this “colonization resistance”. These include direct effects of the commensal organisms. The intestinal microbiota can compete for nutrients, e.g. carbohydrates and vitamin B12, thereby blocking replication of pathogens. Metabolic byproducts include short-chain fatty acids, which can directly inhibit growth of some organisms as well as, in the case of Salmonella, affect expression of the SPI1 T3SS. Some bacteria produce factors like bacteriocins that can directly kill or inhibit other bacteria. It is also likely that some commensal bacteria use type six secretion systems to kill other bacteria with which they come into contact (Schwarz et al. 2010).

Intestinal bacteria can also indirectly affect the ability of pathogens to successfully infect by stimulating both development and function of the mucosal immune system (Buffie and Pamer 2013, Kaiser et al. 2012, Stecher and Hardt 2011). For example, intestinal bacteria promote the production of antimicrobial defensins and REGIIIgamma, both of which can directly kill bacteria, or calprotectin, which chelates manganese and zinc. Commensal bacteria also stimulate the differentiation of Th17 T cells, which help to maintain mucosal barrier function. The fact that the effects of antibiotic treatment are relatively rapid suggests that the mechanism is not via changes in immune system development, but rather a direct result of decreased normal microbiota per se or effects on the relative concentration of antimicrobial factors or changes in barrier function, which could respond rapidly. Supporting this concept is the fact that recovery of the normal flora clears the infection (Endt et al. 2010).

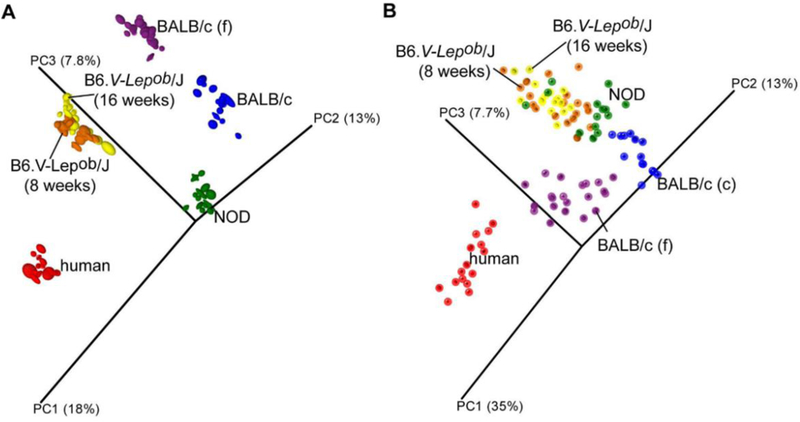

It is also clear that normal or experimental variation of the microbiota, independent of antibiotic treatment, can have profound effects on colonization resistance and susceptibility to Salmonella. Different mouse strains clearly have different microbiota (Fig. 1; (Krych et al. 2013), but the same mouse strain from different vendors can also differ in microbiota and hence colonization resistance (Stecher et al. 2010, Stecher and Hardt 2011). Some investigators have developed mice with “humanized” microbiota – transplanting a human intestinal mixture into gnotobiotic mice (Turnbaugh et al. 2009). It is not clear if such an approach will help understand colonization resistance in that a given human microbiota is no better defined than a given mouse microbiota, and this model does not account for evolved and specific genetic interactions between host and respective microbiota, which could be critical to protection against infection.

Figure 1.

Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) plot based on (A) unweighted and (B) weighted distance matrices, each calculated from 10 rarefied (4500 reads per sample) operational taxonomic unit (OTU) tables. A) Qualitative information used to generate principal coordinates enables for clear clustering according to host that samples were collected from. B) Quantitative information used to generate principal coordinates enables for clear separation of human and both BALB/c samples and less distinct but significant separation of the NOD and two B6 mice gut microbiota profiles. Labels “BALB/c (f)” and “BALB/c (c)” stand for the gut microbiota of BALB/c mice determined using fecal and caecal samples respectively. The degree of variation between 10 jackknifed replicates of PCoA is displayed with confidence ellipsoids around each sample. Reprinted from Krych et al. 2013, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062578.g002.

Stecher and colleagues have taken several approaches to define further the microbiota components that confer colonization protection. In one study (Stecher et al. 2010), they started with mice colonized with the Altered Schaedler Flora, a mixture of eight mouse intestinal bacterial strains. This mixture is routinely used by breeders to provide microbiota to caesarian born mice (Norin and Midtvedt 2010). Mice with this reduced so-called low complexity microbiota are susceptible to inflammatory diarrhea upon oral infection with Salmonella. They then housed some of these mice with conventional mice, allowing them to be colonized by additional intestinal organisms and then correlated the acquired microflora with the level of colonization resistance. In general, they found that the mice that had relatively high levels of E. coli were susceptible to Salmonella induced inflammatory diarrhea.

In a separate study (Brugiroux et al. 2016), Stecher and colleagues colonized mice with a microbiota consisting of 12 cultured and defined bacterial strains isolated from mice. This microbiota stably colonized mice and conferred partial colonization resistance. By performing metagenomic analysis, they compared the metabolic capabilities of this defined microbiota with that of a conventional microbiota and inferred that the defined microbiota lacked certain respiratory pathways. They attempted to compensate by supplementing this defined microbiota with three facultative anaerobes, including an E. coli strain. This apparently more metabolically complete microbiota conferred more complete colonization resistance. Interestingly, the two studies could be interpreted as coming to opposite conclusions. In the first case, the levels of other Enterobacteriaceae correlated with susceptibility to Salmonella and this was interpreted as indicating that the conditions were ripe for colonization by this group of organisms. In the second case, it was the intentional addition of facultative anaerobes that conferred protection against Salmonella, presumably because these organisms effectively compete for nutrients. Obviously more work is required, but it is likely that the overall consortium contributes to colonization protection, rather than the presence or absence of a given class of organism, and different consortia might be equally effective. Tese reductionist approaches provide important experimental tractability to address these fundamental questions.

Remaining questions

The streptomycin mouse model seems to mimic many aspects of human salmonellosis and provides a critical tool to further understand Salmonella infection. But important questions remain. First, how does it work? What does reducing the microbiota do at the molecular level? What is the similarity between the streptomycin-treated mouse intestine and the normal intestine of humans, which are naturally susceptible to Salmonella induced inflammatory diarrhea? Second, where is the initial interaction/invasion of Salmonella within the intestine? In the normal mouse model and Typhi in humans, it is clearly the Peyer’s patch in the distal small intestine. In the streptomycin-treated mouse, the cecum and colon are apparently the primary infection sites, with Salmonella invading and replicating in intestinal epithelial cells. Is this correct? Is this what happens in the normal human intestine? Third, how do the differences in mouse and human anatomy affect the interpretation of these results. The differences in cecum/appendix architecture and function are striking examples (Nguyen et al. 2015). Fourth, how do differences in microbiota affect the outcome? There are differences noted between mice from different sources because of their unmatched microflora and mouse microbiota and human microbiota are obviously different (Krych et al. 2013, Stecher and Hardt 2011); Fig. 1. Of course humans also have “unmatched” microflora. Fourth, is there any bacterial replication prior to intestinal invasion? This has a significant impact on understanding risk of infection at low doses. Fifth, after inflammation is initiated, what is the relative replication rate of intracellular bacteria versus Salmonella in the lumen? Answers to these questions and further refinement of the mouse model with full appreciation of the role of microbiota in the “superorganism” will certainly provide important insight into human disease.

Footnotes

Manuscript for Submission to Human and Ecological Risk Assessment

References

- Alpuche-Aranda CM, Racoosin EL, Swanson JA, et al. 1994. Salmonella stimulate macrophage macropinocytosis and persist within spacious phagosomes. J Exp. Med 179: 601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpuche Aranda CM, Swanson JA, Loomis WP, et al. 1992. Salmonella typhimurium activates virulence gene transcription within acidified macrophage phagosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89: 10079–10083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelichio MJ, Merrell DS, and Camilli A. 2004. Spatiotemporal analysis of acid adaptation-mediated Vibrio cholerae hyperinfectivity. Infect. Immun 72: 2405–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao TT, Feasey NA, Gordon MA, et al. 2015. Global burden of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease, 2010(1). Emerg Infect Dis 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audia JP, Webb CC, and Foster JW. 2001. Breaking through the acid barrier: an orchestrated response to proton stress by enteric bacteria. Int J Med Microbiol 291: 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik HS, Bearson S, Dunbar S, et al. 1996. The acid tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium provides protection against organic acids. Microbiology 142 ( Pt 11): 3195–3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakowski MA, Braun V, and Brumell JH. 2008. Salmonella-containing vacuoles: directing traffic and nesting to grow. Traffic 9: 2022–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel M, Hapfelmeier S, Quintanilla-Martinez L, et al. 2003. Pretreatment of mice with streptomycin provides a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colitis model that allows analysis of both pathogen and host. Infect. Immun 71: 2839–2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumler AJ, Tsolis RM, and Heffron F. 1996. The lpf fimbrial operon mediates adhesion of Salmonella typhimurium to murine Peyer’s patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 93: 279–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavishi C, and Dupont HL. 2011. Systematic review: the use of proton pump inhibitors and increased susceptibility to enteric infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 34: 1269–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearson BL, Wilson L, and Foster JW. 1998. A low pH-inducible, PhoPQ-dependent acid tolerance response protects Salmonella typhimurium against inorganic acid stress. J Bacteriol 180: 2409–2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk PA, Jonge R, Zwietering MH, et al. 2005. Acid resistance variability among isolates of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104. J Appl Microbiol 99: 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell JM, Searle S, Mohamed H, et al. 2003. Divalent cation transport and susceptibility to infectious and autoimmune disease: continuation of the Ity/Lsh/Bcg/Nramp1/Slc11a1 gene story. Immunol Lett 85: 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ, and Newman LS. 1982. A review of human salmonellosis: I. Infective dose. Rev. Infect. Dis 4: 1096–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnhoff M, Drake BL, and Miller CP. 1954. Effect of streptomycin on susceptibility of intestinal tract to experimental Salmonella infection. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 86: 132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnhoff M, Drake BL, and Miller CP. 1955. The effect of an antibiotic on the susceptibility of the mouse’s intestinal tract to Salmonella infection. Antibiot Annu 3: 453–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnhoff M, and Miller CP. 1962. Enhanced susceptibility to Salmonella infection in streptomycin-treated mice. J Infect Dis 111: 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boring JR, Martin WT, and Elliott LM. 1971. Isolation of Salmonella Typhi-Murium from Municipal Water, Riverside, California, 1965. Am J Epidemiol 93: 49–&. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JF. 1985. Pathology of the alimentary tract in Salmonella typhimurium food poisoning. Gut 26: 935–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan MA, and Cookson BT. 2000. Salmonella induces macrophage death by caspase-1-dependent necrosis. Mol. Microbiol 38: 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugiroux S, Beutler M, Pfann C, et al. 2016. Genome-guided design of a defined mouse microbiota that confers colonization resistance against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Nat Microbiol 2: 16215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffie CG, and Pamer EG. 2013. Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance against intestinal pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 790–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton NA, Schurmann N, Casse O, et al. 2014. Disparate impact of oxidative host defenses determines the fate of Salmonella during systemic infection in mice. Cell Host. Microbe 15: 72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante VH, Martinez LC, Santana FJ, et al. 2008. HilD-mediated transcriptional cross-talk between SPI-1 and SPI-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105: 14591–14596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MC, Small DM, and Bliss CM. 1983. Lipid digestion and absorption. Annu Rev Physiol 45: 651–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter PB, and Collins FM. 1974. The route of enteric infection in normal mice. J. Exp. Med 139: 1189–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, (2014) Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet): FoodNet Surveillance Report for 2014 (Final Report). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, and Barrett EL. 1987. The phs gene and hydrogen sulfide production by Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 169: 2391–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn B, Grassl GA, and Finlay BB. 2007a. Salmonella, the host and disease: a brief review. Immunol Cell Biol 85: 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn B, Grassl GA, and Finlay BB. 2007b. Salmonella, the host and disease: a brief review. Immunol. Cell Biol 85: 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn B, Li Y, Owen D, et al. 2005. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium pathogenicity island 2 is necessary for complete virulence in a mouse model of infectious enterocolitis. Infect. Immun 73: 3219–3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes BK, Coburn BA, Potter AA, et al. 2005. Analysis of the contribution of Salmonella pathogenicity islands 1 and 2 to enteric disease progression using a novel bovine ileal loop model and a murine model of infectious enterocolitis. Infect. Immun 73: 7161–7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig M, Sadik AY, Golubeva YA, et al. 2013. Twin-arginine translocation system (tat) mutants of Salmonella are attenuated due to envelope defects, not respiratory defects. Mol. Microbiol 89: 887–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley SM, Knodler LA, and Vallance BA. 2016. Salmonella and the Inflammasome: Battle for Intracellular Dominance. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 397: 43–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aoust JY. 1985. Infective dose of Salmonella typhimurium in cheddar cheese. Am J Epidemiol 122: 717–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellermeier CD, and Slauch JM, (2006) The Genus Salmonella In: The Prokaryotes. Springer; New York, pp. 123–158. [Google Scholar]

- Endt K, Stecher B, Chaffron S, et al. 2010. The microbiota mediates pathogen clearance from the gut lumen after non-typhoidal Salmonella diarrhea. PLoS. Pathog 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber F, Thiennimitr P, Spiga L, et al. 2017. Respiration of Microbiota-Derived 1,2-propanediol Drives Salmonella Expansion during Colitis. PLoS Pathog 13: e1006129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, et al. 2012. Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet 379: 2489–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink SL, and Cookson BT. 2007. Pyroptosis and host cell death responses during Salmonella infection. Cell Microbiol 9: 2562–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furne J, Springfield J, Koenig T, et al. 2001. Oxidation of hydrogen sulfide and methanethiol to thiosulfate by rat tissues: a specialized function of the colonic mucosa. Biochem Pharmacol 62: 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantois I, Ducatelle R, Pasmans F, et al. 2006. Butyrate specifically down-regulates salmonella pathogenicity island 1 gene expression. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 72: 946–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner CD, Antonopoulos DA, Wagner B, et al. 2009. Perturbation of the small intestine microbial ecology by streptomycin alters pathology in a Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium murine model of infection. Infect. Immun 77: 2691–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvis SG, Beuzon CR, and Holden DW. 2001. A role for the PhoP/Q regulon in inhibition of fusion between lysosomes and Salmonella-containing vacuoles in macrophages. Cell Microbiol 3: 731–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubeva YA, Ellermeier JR, Cott Chubiz JE, et al. 2016. Intestinal Long-Chain Fatty Acids Act as a Direct Signal To Modulate Expression of the Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 1 Type III Secretion System. MBio 7: e02170–02115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubeva YA, Sadik AY, Ellermeier JR, et al. 2012. Integrating global regulatory input into the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 type III secretion system. Genetics 190: 79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubeva YA, and Slauch JM. 2006. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium periplasmic superoxide dismutase SodCI is a member of the PhoPQ regulon and is induced in macrophages. J. Bacteriol 188: 7853–7861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groisman EA, and Aspedon A. 1997. The genetic basis of microbial resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Methods Mol. Biol 78: 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn JS, Lim KB, Krueger J, et al. 1998. PmrA-PmrB-regulated genes necessary for 4-aminoarabinose lipid A modification and polymyxin resistance. Mol. Microbiol 27: 1171–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Lim KB, Gunn JS, et al. 1997. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science 276: 250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutnick D, Calvo JM, Klopotowski T, et al. 1969. Compounds which serve as the sole source of carbon or nitrogen for Salmonella typhimurium LT-2. J Bacteriol 100: 215–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapfelmeier S, Stecher B, Barthel M, et al. 2005. The Salmonella pathogenicity island (SPI)-2 and SPI-1 type III secretion systems allow Salmonella serovar typhimurium to trigger colitis via MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent mechanisms. J Immunol 174: 1675–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraga A, Ohlson MB, and Miller SI. 2008. Salmonellae interplay with host cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 6: 53–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy A, (2015) Salmonella Infections, Networks of Knowledge, and Public Health in Britain, 1880–1975. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy TW, Hedberg CW, Slutsker L, et al. 1996. A National Outbreak of Salmonella enteritidis Infections from Ice Cream. N. Engl. J. Med 334: 1281–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins SA, and Kraehenbuhl JP. 1997. Dendritic cells of the murine Peyer’s patches colocalize with Salmonella typhimurium avirulent mutants in the subepithelial dome. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 417: 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins SA, Niedergang F, Corthesy-Theulaz IE, et al. 2000. A recombinant Salmonella typhimurium vaccine strain is taken up and survives within murine Peyer’s patch dendritic cells. Cell Microbiol 2: 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Suyemoto M, Garner CD, et al. 2008. Formate acts as a diffusible signal to induce Salmonella invasion. J Bacteriol 190: 4233–4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung CC, Garner CD, Slauch JM, et al. 2013. The intestinal fatty acid propionate inhibits Salmonella invasion through the post-translational control of HilD. Mol. Microbiol 87: 1045–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BD, Ghori N, and Falkow S. 1994. Salmonella typhimurium initiates murine infection by penetrating and destroying the specialized epithelial M cells of the Peyer’s patches. J. Exp. Med 180: 15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser P, Diard M, Stecher B, et al. 2012. The streptomycin mouse model for Salmonella diarrhea: functional analysis of the microbiota, the pathogen’s virulence factors, and the host’s mucosal immune response. Immunol Rev 245: 56–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato A, and Groisman EA. 2008. The PhoQ/PhoP regulatory network of Salmonella enterica. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 631: 7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keestra AM, Winter MG, Klein-Douwel D, et al. 2011. A Salmonella virulence factor activates the NOD1/NOD2 signaling pathway. MBio 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent TH, Formal SB, and Labrec EH. 1966. Salmonella gastroenteritis in rhesus monkeys. Arch Pathol 82: 272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoramian-Falsafi T, Harayama S, Kutsukake K, et al. 1990. Effect of motility and chemotaxis on the invasion of Salmonella typhimurium into HeLa cells. Microb Pathog 9: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodler LA. 2015. Salmonella enterica: living a double life in epithelial cells. Curr Opin Microbiol 23: 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodler LA, Crowley SM, Sham HP, et al. 2014a. Noncanonical inflammasome activation of caspase-4/caspase-11 mediates epithelial defenses against enteric bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 16: 249–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodler LA, Nair V, and Steele-Mortimer O. 2014b. Quantitative assessment of cytosolic Salmonella in epithelial cells. PLoS One 9: e84681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodler LA, Vallance BA, Celli J, et al. 2010. Dissemination of invasive Salmonella via bacterial-induced extrusion of mucosal epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 17733–17738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohbata S, Yokoyama H, and Yabuuchi E. 1986. Cytopathogenic effect of Salmonella typhi GIFU 10007 on M cells of murine ileal Peyer’s patches in ligated ileal loops: an ultrastructural study. Microbiol. Immunol 30: 1225–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothary MH, and Babu US. 2001. Infective dose of foodborne pathogens in volunteers: a review. J Food Safety 21: 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus MD, Amatya B, and Kimula Y. 1999. Histopathology of typhoid enteritis: morphologic and immunophenotypic findings. Mod Pathol 12: 949–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krych L, Hansen CH, Hansen AK, et al. 2013. Quantitatively different, yet qualitatively alike: a meta-analysis of the mouse core gut microbiome with a view towards the human gut microbiome. PLoS One 8: e62578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamps LW. 2007. Infective disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. Histopathology 50: 55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRock DL, Chaudhary A, and Miller SI. 2015. Salmonellae interactions with host processes. Nat Rev Microbiol 13: 191–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin RC, Knodler LA, Barhoumi R, et al. 2014. Spatial segregation of virulence gene expression during acute enteric infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. MBio 5: e00946–00913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawhon SD, Maurer R, Suyemoto M, et al. 2002. Intestinal short-chain fatty acids alter Salmonella typhimurium invasion gene expression and virulence through BarA/SirA. Mol. Microbiol 46: 1451–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez CA, Winter SE, Rivera-Chavez F, et al. 2012. Phage-mediated acquisition of a type III secreted effector protein boosts growth of salmonella by nitrate respiration. MBio 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majowicz SE, Musto J, Scallan E, et al. 2010. The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin. Infect. Dis 50: 882–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez LC, Yakhnin H, Camacho MI, et al. 2011. Integration of a complex regulatory cascade involving the SirA/BarA and Csr global regulatory systems that controls expression of the Salmonella SPI-1 and SPI-2 virulence regulons through HilD. Mol. Microbiol 80: 1637–1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroeni P, Grant A, Restif O, et al. 2009. A dynamic view of the spread and intracellular distribution of Salmonella enterica. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 7: 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhie EJ, Brawn LC, Hume PJ, et al. 2009. Salmonella takes control: effector-driven manipulation of the host. Curr Opin Microbiol 12: 117–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern VJ, and Slavutin LJ. 1979. Pathology of salmonella colitis. Am J Surg Pathol 3: 483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CP, Bohnhoff M, and Rifkind D. 1956. The effect of an antibiotic on the susceptibility of the mouse’s intestinal tract to Salmonella infection. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 68: 51–55; discussion 55–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monack DM, Bouley DM, and Falkow S. 2004. Salmonella typhimurium persists within macrophages in the mesenteric lymph nodes of chronically infected Nramp1+/+ mice and can be reactivated by IFNgamma neutralization. J. Exp. Med 199: 231–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monack DM, Hersh D, Ghori N, et al. 2000. Salmonella exploits caspase-1 to colonize Peyer’s patches in a murine typhoid model. J. Exp. Med 192: 249–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TL, Vieira-Silva S, Liston A, et al. 2015. How informative is the mouse for human gut microbiota research? Dis Model Mech 8: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nix RN, Altschuler SE, Henson PM, et al. 2007. Hemophagocytic macrophages harbor Salmonella enterica during persistent infection. PLoS. Pathog 3: e193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordlander S, Pott J, and Maloy KJ. 2014. NLRC4 expression in intestinal epithelial cells mediates protection against an enteric pathogen. Mucosal Immunol 7: 775–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norin E, and Midtvedt T. 2010. Intestinal microflora functions in laboratory mice claimed to harbor a “normal” intestinal microflora. Is the SPF concept running out of date? Anaerobe 16: 311–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottemann KM, and Miller JF. 1997. Roles for motility in bacterial-host interactions. Mol Microbiol 24: 1109–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter JA, Hoekstra RM, Ayers T, et al. 2013. Attribution of foodborne illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths to food commodities by using outbreak data, United States, 1998–2008. Emerg Infect Dis 19: 407–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez KJ, Ceccon RV, Malheiros PD, et al. 2010. Influence of Acid Adaptation on the Survival of Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Typhimurium in Simulated Gastric Fluid and in Rattus Norvegicus Intestine Infection. J Food Safety 30: 398–414. [Google Scholar]

- Que JU, and Hentges DJ. 1985. Effect of streptomycin administration on colonization resistance to Salmonella typhimurium in mice. Infect Immun 48: 169–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathman M, Sjaastad MD, and Falkow S. 1996. Acidification of phagosomes containing Salmonella typhimurium in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun 64: 2765–2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Chavez F, Winter SE, Lopez CA, et al. 2013. Salmonella uses energy taxis to benefit from intestinal inflammation. PLoS. Pathog 9: e1003267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan D, Pati NB, Ojha UK, et al. 2015. Global transcriptome and mutagenic analyses of the acid tolerance response of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Appl Environ Microbiol 81: 8054–8065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos RL, Zhang S, Tsolis RM, et al. 2001. Animal models of Salmonella infections: enteritis versus typhoid fever. Microbes. Infect 3: 1335–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, et al. 2011. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States--major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis 17: 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S, Hood RD, and Mougous JD. 2010. What is type VI secretion doing in all those bugs? Trends Microbiol 18: 531–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin ME, Maslowski KM, Maloy KJ, et al. 2015. Inflammasomes of the intestinal epithelium. Trends Immunol 36: 442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin ME, Muller AA, Felmy B, et al. 2014. Epithelium-intrinsic NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasome drives infected enterocyte expulsion to restrict Salmonella replication in the intestinal mucosa. Cell Host Microbe 16: 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL. 2003. The role of gastric acid in preventing foodborne disease and how bacteria overcome acid conditions. J Food Prot 66: 1292–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl A, Hirsch DJ, Gimeno RE, et al. 1999. Identification of the major intestinal fatty acid transport protein. Mol Cell 4: 299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B, Barthel M, Schlumberger MC, et al. 2008. Motility allows S. Typhimurium to benefit from the mucosal defence. Cell Microbiol 10: 1166–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B, Chaffron S, Kappeli R, et al. 2010. Like will to like: abundances of closely related species can predict susceptibility to intestinal colonization by pathogenic and commensal bacteria. PLoS. Pathog 6: e1000711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B, and Hardt WD. 2008. The role of microbiota in infectious disease. Trends Microbiol 16: 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B, and Hardt WD. 2011. Mechanisms controlling pathogen colonization of the gut. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 14: 82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker BA, Hoiseth SK, and Smith BP. 1983. Aromatic-dependent “Salmonella sp.” as live vaccine in mice and calves. Dev. Biol. Stand 53: 47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm A, Heinemann M, Arnoldini M, et al. 2011. The cost of virulence: retarded growth of Salmonella Typhimurium cells expressing type III secretion system 1. PLoS. Pathog 7: e1002143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunis PF, Kasuga F, Fazil A, et al. 2010. Dose-response modeling of Salmonella using outbreak data. Int J Food Microbiol 144: 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiennimitr P, Winter SE, Winter MG, et al. 2011. Intestinal inflammation allows Salmonella to use ethanolamine to compete with the microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108: 17480–17485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsolis RM, Kingsley RA, Townsend SM, et al. 1999. Of mice, calves, and men. Comparison of the mouse typhoid model with other Salmonella infections. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 473: 261–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, et al. 2009. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci Transl Med 1: 6ra14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal S, Gros P, and Skamene E. 1995. Natural resistance to infection with intracellular parasites: molecular genetics identifies Nramp1 as the Bcg/Ity/Lsh locus. J. Leukoc. Biol 58: 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PR, Gautier AV, Paulin SM, et al. 2000. Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium and Dublin can lyse macrophages by a mechanism distinct from apoptosis. Infect. Immun 68: 3744–3747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessling-Resnick M 2015. Nramp1 and Other Transporters Involved in Metal Withholding during Infection. J Biol Chem 290: 18984–18990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter SE, Thiennimitr P, Nuccio SP, et al. 2009. Contribution of flagellin pattern recognition to intestinal inflammation during Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium infection. Infect. Immun 77: 1904–1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter SE, Thiennimitr P, Winter MG, et al. 2010. Gut inflammation provides a respiratory electron acceptor for Salmonella. Nature 467: 426–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter SE, Winter MG, Xavier MN, et al. 2013. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science 339: 708–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]