Abstract

Background:

Chronic pain is common among older adults and is associated with cognitive dysfunction based on cross-sectional studies. However, the longitudinal association between chronic pain and incident dementia in community-based samples is unknown.

Objective:

We aimed to evaluate the association of pain intensity and pain interference with incident dementia in a community-based sample of older adults.

Methods:

Participants were 1,114 individuals 70 years of age or older from Einstein Aging Study (EAS), a longitudinal cohort study of community-dwelling older adults in the Bronx County, NY. The primary outcome measure was incident dementia, diagnosed using DSM-IV criteria. Pain intensity and interference in the month prior to first annual visit were measured using items from the SF-36 questionnaire. Pain intensity and pain interference were assessed as predictors of time to incident dementia using Cox proportionate hazards models while controlling for potential confounders.

Results:

Among participants, 114 individuals developed dementia over an average 4.4 years (SD=3.1) of follow-up. Models showed that pain intensity had no significant effect on time to developing dementia, whereas higher levels of pain interference were associated with a higher risk of dementia. In the model that included both pain intensity and interference as predictors of incident dementia, pain interference had a significant effect on incident dementia, and pain intensity remained non-significant.

Conclusion:

As a potential remediable risk factor, the mechanisms linking pain interference to cognitive decline merit further exploration.

Keywords: Pain intensity, pain interference, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, remediable risk factor

1. INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of Alzheimer’s Dementia (AD) in the U.S. is projected to reach 13.5 million by 2050 [1], and direct costs of long-term care and medical care for people living with AD and other dementias make it a substantial financial burden [2]. As therapeutic options are limited, identifying remediable risk factors is an important approach to prevention [3]. Chronic pain, a potentially remediable risk factor, is associated with adverse quality of life and health outcomes including cognitive dysfunction [4, 5]. One recent study indicated that persistent pain is associated with accelerated memory decline and increased probability of dementia [6]. Pain-related impairments in various domains of cognitive function including attention, learning and memory, ex ecutive function, processing speed, and psychomotor ability have been reported in many observational studies [7, 8]. However, most of these studies have been either cross-sectional [7], limiting the ability to ascertain a causal relationship, or have been conducted in pain or memory clinic patient populations [9], limiting generalizability to community-based populations.

One of the major issues in studies focusing on pain is that of dimensionality. While pain is universally acknowledged to be multidimensional [10], most studies of pain and cognitive function have focused only on the severity (intensity) dimension of pain [11, 12]. However, other dimensions of pain such as pain interference, i.e. the degree that pain interferes with individual’s daily activities, or affective domain of pain are of equal, if not greater, importance [10, 13]. A few cross-sectional studies have suggested that prevalence of clinically relevant cognitive impairment is higher in chronic pain patients in comparison with the general population [14, 15]. Both pain intensity and pain interference are associated with a variety of adverse neurocognitive effects [16, 17]. However, some other studies do not support this relationship [11, 12]. Many of these negative studies focus on pain intensity and other dimensions of pain are overlooked. Epidemiological studies of chronic pain suggest considerable heterogeneity in pain interference in persons with comparable levels of pain intensity [18]. These studies suggest that characterizing pain separately based on pain intensity and interference may be useful in predicting outcomes.

The Einstein Aging Study (EAS), with many years of prospective data on pain and cognitive function in a community-based sample of older adults, provides an opportunity to examine the role of pain intensity and interference as risk factors for development of dementia. Our goal was to determine the individual and joint effects of pain intensity and pain interference on dementia incidence.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Population

The Einstein Aging Study (EAS) is a community-based longitudinal study of cognitive aging and dementia located in Bronx, NY. The EAS started systematic recruitment of adults aged 70 years older in 1993. From 1993 to 2004, Health Care Financing Administration/Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (HCFA/CMS) rosters of Medicare-eligible persons 70 years or older were used by the EAS to develop sampling frames of community residing individuals in Bronx County. Since 2004, New York City Board of Elections registered voter lists for Bronx County have been used because of changes in HCFA/CMS policies. Individuals were mailed introductory letters, which were followed by a brief telephone screening interview. We estimate that the voter lists provide a sampling frame that includes over 90% of community residing individuals over 65 using U.S. Census data as a reference, and therefore it is considered a good representation of the Bronx County community. Final screening and enrollment were completed at the EAS clinic. The demographic characteristics of participants enrolled using either list were similar. Consistent methods for recruitment, telephone screening procedures, and consenting protocols have been used since the beginning of the study in 1993, and retention rates and duration of follow-up have also remained similar. Eligibility criteria for being enrolled in EAS study were age of 70 years or older, English speaking, and being non-demented at initial study visit. Participants all undergo annual assessments including clinical evaluations, a neuropsychological battery, psychosocial measures, medical histories, demographics, standardized assessments of activities of daily living, and self- and informant reports of memory and cognitive complaints. Additional study details are described elsewhere [19].

This analysis includes data from participants enrolled between February 1994 and May 2015 with additional inclusion criteria including completion of measurements of pain intensity and pain interference, and having at least one subsequent annual follow-up.

2.2. Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at study entry. Study protocols were approved by the Einstein institutional review board.

2.3. Clinical Information and Measurement of Risk Factors

Trained research assistants administered structured questionnaires to obtain demographic information (age, sex, race/ethnicity and years of education) as well as medical history and use of pain medications at each annual visit. Using baseline medical history, we calculated a medical comorbidity index score (ranging from 0 to 9) from dichotomous self-report (present vs absent) of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure, Parkinson’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as previously described [20].

Pain intensity and pain interference were measured using the bodily pain subscale from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (MOS SF-36) [21], which is a reliable, valid and widely used measure of health related quality of life questionnaire [22]. The pain intensity question asked: ‘How much bodily pain have you had during the past 4 weeks?’ Scores ranged from 1 to 6 with 1 = ‘none’ and 6 = ‘very severe’. The pain interference question asked: ‘During the past 4 weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work, including both work outside the home and housework?’ Scores ranged from 1 to 5 with 1 = ‘not at all’ and 5 = ‘extremely’. Pain intensity and interference were entered into statistical models as continuous variables.

The 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used to evaluate presence of depressive symptoms [23]. GDS scores range from 0 to15, A cut-score of 5 or greater was used to identify individuals with clinically significant depressive symptoms [24].

3. DEMENTIA DIAGNOSIS

Dementia was diagnosed according standardized criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and required impairment in memory plus at least one additional cognitive domain, accompanied by evidence of decline from a previous level of functioning [31]. A licensed neuropsychologist used normative data to determine whether impairment existed in any of the five cognitive domains [32]. A physician independently interviewed and examined each participant, completed a Clinical Dementia Rating scale, and documented a clinical impression of whether dementia was present [33–35]. Final diagnostic determination was made at consensus case conferences attended by the neuropsychologist and a board-certified neurologist. Diagnosis of Alzheimer disease was made in individuals with dementia who met clinical criteria for probable or possible disease established by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association [25].

4. STATISTICAL METHODS

The effect of baseline pain intensity and interference on the risk of dementia incidence was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, and estimated hazard ratios (HR) with 95 percent confidence intervals were reported. The time to event was defined as the time from the baseline visit, to the visit at which dementia was first diagnosed. In persons who did not develop dementia data was censored at the data of last follow-up. All models include age at enrollment, sex, race, educational level, and chronic medical comorbidities as covariates. In primary models we examined the effect of baseline pain intensity and interference on incident dementia separately. Subsequently, we assessed joint effects of pain intensity and interference on incident dementia while adjusting for other covariates. Analogous models were used to examine the effects of pain intensity and interference on incident Alzheimer’s disease.

In supplementary analyses, we adjusted for clinically significant depressive symptoms (GDS<5 vs GDS≥5) and pain medication use as other potential confounders in separate models. The pain medications entered in the models were nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Less than 0.5% of the sample reported use of opioids for pain control and therefore opioid use was not included in the models. Additionally, in a sensitivity analysis, we repeated Cox proportional hazards models separately for short-term (<3years) and long term (≥3years) follow-up groups. This analysis was performed to study the timing of incident dementia in relation to pain symptoms. The proportional hazards assumptions for all models were adequately met according to methods based on scaled Schoenfeld residuals [26].

5. RESULTS

5.1. Demographic Characteristics

Pain measures were completed by 1114 participants who were free of dementia at the time of the initial assessment, and who had completed at least one annual follow-up. Overall, 114 participants (10.2%) developed dementia during follow up. Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics at baseline stratified by individuals who at final assessment developed dementia or remained dementia free. Average follow-up time was 4.4 years (SD=3.1; Range 1–16.5 years). The group who developed dementia were on average older (P<0.001), but did not differ in sex (p=0.656), race/ethnicity (p=0.304), education or GDS score (p=0.091). There was a significant association between higher pain intensity and interference and NSAIDs use in the entire sample (P<0.001 for both).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic variables in the entire sample and by dementia status at follow-up.

| Total Sample (N=1114) | Remained Free of Dementia (N=1000) | Developed Dementia (N=114) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women, N (%) | 692 (62) | 619 (62) | 73 (64) | 0.656 |

| Race, White, N (%) | 436 (66) | 665 (66) | 71 (62) | 0.304 |

| Age, years (SD) | 78.1 (5.0) | 77.9 (5.2) | 80.4 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Education, y, mean (SD) | 13.9 (3.5) | 14.0 (3.5) | 13.8 (3.5) | 0.540 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.2(5.4) | 28.3 (5.4) | 26.2(4.9) | 0.025 |

| BIMC, mean (SD) | 2.4(2.3) | 2.2(2.1) | 4.2(3.0) | <0.001 |

| IADLs, mean (SD) | 6.6 (1.5) | 6.6 (1.5) | 6.5 (1.5) | 0.455 |

| GDS, mean (SD) | 2.3 (2.3) | 2.3 (2.3) | 2.6 (2.4) | 0.091 |

| Pain intensity, mean (SD) | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.6 (1.5) | 0.640 |

| Pain interference, mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.1) | 0.611 |

| NSAIDs use, N (%) | 110(10) | 95(9.5) | 15(13.2) | 0.263 |

| Follow-up time, y, mean (SD) | 4.4 (3.1) | 4.4 (3.2) | 4.4 (3.0) | 0.977 |

P-values represent difference between participants who developed dementia vs participants who remained dementia free. BMI data was available only for 537 participants. GDS= geriatric depression scale; NSAIDs =Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; BIMC= Blessed Information-Memory-Concentration Score; IADLs: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; BMI: Body Mass Index.

5.2. Pain Intensity and Interference and Incidence of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease

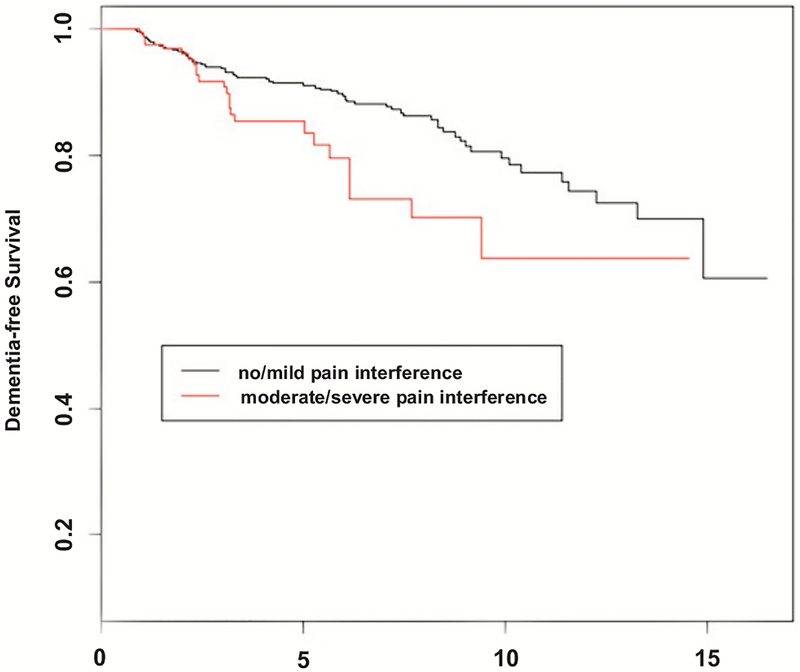

Table 2 presents a series of Cox proportional hazards models relating pain intensity and interference to incident dementia, while adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education and medical comorbidities. Model 1 shows that pain intensity had no significant influence on risk of developing dementia (HR=1.02; 95% CI, 0.89–1.18). Model 2 showed that each one-point increase in the level of pain interference at baseline was associated with higher incident dementia (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.03–1.49). In model 3, we evaluated the joint effects of pain intensity and interference on development of dementia. In this combined model, the effect of pain interference on incident dementia persisted (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.07–1.73) while pain intensity continued to show no effect (HR=0.90; 95% CI, 0.75–1.08). The Kaplan Meier curve comparing the risk of dementia for those with no/mild pain interference (scores = 1 or 2), and moderate/severe pain interference (scores = 3, 4, or 5) is shown in Fig. (1).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for incident dementia using baseline level of pain intensity and pain interference as predictors.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age at baseline | 1.13 | 1.09–1.17 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 1.09–1.17 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 1.09–1.17 | <.001 |

| Sex, Female | 0.98 | 0.66–1.46 | 0.938 | 0.97 | 0.65–1.45 | 0.909 | 1.01 | 0.68–1.50 | 0.967 |

| Education, years | 0.99 | 0.93–1.04 | 0.732 | 0.99 | 0.93–1.04 | 0.774 | 0.99 | 0.94–1.05 | 0.782 |

| Race, African-American | 1.45 | 0.96–2.18 | 0.073 | 1.42 | 0.94–2.14 | 0.091 | 1.42 | 0.94–2.14 | 0.092 |

| Medical comorbidity | 0.97 | 0.81–1.16 | 0.756 | 0.94 | 0.78–1.12 | 0.494 | 0.96 | 0.80–1.14 | 0.630 |

| Pain intensity | 1.02 | 0.89–1.18 | 0.693 | 0.90 | 0.75–1.08 | 0.264 | |||

| Pain interference | 1.24 | 1.03–1.49 | 0.021 | 1.36 | 1.07–1.73 | 0.013 | |||

Model 1: adjusted for demographics and pain intensity; Model 2: adjusted for demographics and pain interference Model 3: adjusted for demographics, pain intensity and pain interference.

Fig. (1).

Kaplan-Meir Survival Curves for three levels of pain interference (Black line: no/mild pain interference, Red line: moderate/severe pain interference).

Of the 114 individuals with incident dementia, 98 met criteria for probable or possible AD. Repeating Cox proportional hazards models for prediction of AD (Table 3) showed that pain intensity had no effect (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.93–1.25) while pain interference was a significant predictor of dementia due to AD (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.04–1.54). Similar to results for prediction of all-cause dementia, models including both pain intensity and interference showed that only pain interference predicted incident dementia due to AD with a hazard ratio of 1.30 (95% CI, 1.01–1.67).

Table 3.

Risk of development incident Alzheimer’s dementia based on level of pain intensity and pain interference at baseline.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age at baseline | 1.14 | 1.10–1.18 | <.001 | 1.15 | 1.10–1.19 | <.001 | 1.15 | 1.11–1.19 | <.001 |

| Sex, Female | 1.13 | 0.73–1.75 | 0.579 | 1.14 | 0.74–1.76 | 0.543 | 1.16 | 0.74–1.79 | 0.518 |

| Education, years | 0.97 | 0.91–1.03 | 0.392 | 0.97 | 0.92–1.03 | 0.421 | 0.98 | 0.92–1.04 | 0.424 |

| Race, African-American | 1.26 | 0.80–1.98 | 0.305 | 1.24 | 0.79–1.94 | 0.346 | 1.24 | 0.79–1.95 | 0.345 |

| Medical comorbidity | 0.89 | 0.73–1.08 | 0.242 | 0.87 | 0.71–1.05 | 0.165 | 0.88 | 0.72–1.07 | 0.188 |

| Pain intensity | 1.07 | 0.93–1.25 | 0.316 | 0.97 | 0.80–1.17 | 0.745 | |||

| Pain interference | 1.26 | 1.04–1.54 | 0.021 | 1.30 | 1.01–1.67 | 0.043 | |||

Model 1: adjusted for demographics and pain intensity; Model 2: adjusted for demographics and pain interference Model 3: adjusted for demographics, pain intensity and pain interference.

5.3. Influence of Depressive Symptoms, Medication Use and Time to Dementia

Depressive symptoms and frequent use of pain medications are both potential confounders of relationship between pain and incident dementia. Accordingly, we reran the last Cox-proportional hazards model (model 3, Table 2), adjusting for depression and NSAIDs use (the most frequent pain medication used in our sample). Similar to initial models, in this model pain interference remained a significant predictor of incident dementia (HR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.69). Neither depressive symptoms nor NSAIDs were significantly associated with incident dementia in this sample.

While pain interference appears to be a risk factor for incident dementia, there is the possibility of reverse causality. That is, persons with subtle cognitive impairment may be more vulnerable to pain interference. Under this hypothesis, we would expect pain interference to more strongly predict incident dementia at times close to diagnosis. In order to test this hypothesis, we conducted sensitivity analyses by stratifying on time to dementia diagnosis (<3 years versus >=3 years). The results indicated that the hazard ratios of pain interference on incident dementia was 1.28 (95% CI, 0.69–1.83) for dementia onset over the first 3 years. The hazard ratio for pain interference for dementia incidence 3 or more years from baseline was 1.55 (95% CI, 1.11–2.2).

6. DISCUSSION

This prospective study demonstrated a significant association between higher levels of pain interference, and an increased incidence of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia. The association between pain interference and risk of dementia remained robust after adjusting for pain intensity and after adjusting for potential confounding variables such as age, sex, educational level, chronic medical comorbidities, and depressive symptoms.

We are not aware of community-based studies investigating the longitudinal effect of pain intensity and interference on dementia onset in older adults. Prior studies in persons with chronic pain have shown poor performance in various cognitive tests, including tests which assess executive processes, episodic memory, attention, and psychomotor speed [7]. These studies have indicated that among individuals with apparently similar levels of pain intensity and duration, the occurrence of cognitive impairment, impaired social relationships and reduced quality of life is variable [18, 27]. The heterogeneity in the manifestations and correlates of chronic pain might be in part due to multi-dimensional nature of pain. One factor which may contribute to inconsistent results across studies is that pain interference is a better predictor of cognitive performance than measures of pain intensity or chronicity.

There are a few possible explanations for the observed association between higher pain inter ference and increased incidence of dementia. First, results may be influenced by confounding variables like depression or use of pain medications. While the results survive adjustment for these measured confounders, we cannot exclude the possibility of un-measured confounders. Second, the presence of subtle cognitive impairment in preclinical dementia may increase pain interference (reverse causality hypothesis). Under this explanation, pain interference is a consequence of cognitive decline and not a risk factor for it. Third, pain interference may have a true causal effect on incident dementia.

Residual or unadjusted confounders (Hypothesis 1) are always possible in observational studies. Herein, we considered depression as a potential confounder on the relationship of pain to dementia onset. The association and bidirectional causal relationship between pain and depression is well documented in literature [28]. There is strong evidence that improved depression care leads to decreased pain [29], while it has been shown that optimizing the management of co-morbid pain that commonly coexists with depression may be important in improving outcome of interventions on depression [30]. Depression has been suggested as a risk factor for incident dementia by itself [31]. In the current study, we showed that inclusion of depression as a confounder does not affect the significance of effect of pain interference and dementia onset. Another potential confounder is use of pain medications including NSAIDs. Previous cohort studies report inconsistent findings about effect of NSAID use and risk of dementia [32, 33]. In our study, NSAIDs use did not affect association between pain interference and dementia. Potential confounders not addressed in this manuscript include genetic and inflammatory factors that could predispose to both pain interference and cognitive decline. These merit future exploration.

Under hypothesis 2, we would expect to see greater hazard ratio when pain interference was measured close to the time of dementia diagnosis. However, our results indicated that pain interference was not significantly associated with incident dementia in participants who were diagnosed with dementia over 3 years of follow-up. However, pain interference was a significant predictor of incident dementia beginning 3 or more years after the initial assessment of pain. This finding is more consistent with the hypothesis of direct causality.

Under hypothesis 3, pain interference may contribute to the development of dementia. Although the precise mechanisms mediating cognitive impairment in individuals suffering from pain have yet to be elucidated, several hypotheses have been suggested. Cognitive impairment in patients with chronic pain has been associated with mood changes and emotional distress and with symptoms and clinical features such sleep disturbance, fatigue, and perceived interference with daily activities that are potential sources of chronic stress. Chronic pain, along with its accompanying stress, may lead to prolonged activation of HPA axis and glucocorticoid elevation. The neurotoxicity hypothesis [34] suggests that prolonged exposure to stress hormones reduces the ability of neurons to resist insults, thus increasing the rate at which they are damaged by other toxic challenges or ordinary attrition. According to this hypothesis cumulative exposure to high glucocorticoid levels and resultant neurotoxicity, might lead to alteration in regional brain structure and function, specifically in hippocampus [34] and prefrontal cortex [35]. These brain structures implicated in pain and stress have significant overlap with regions involved in neurocognitive function [36–40]. When coupled with the observation that pain predicts incident dementia, these overlapping imaging findings suggest that overlapping neural substrates might link pain to cognitive decline and ultimately dementia.

Although we used a large community-based sample of older adults with up to 21 years of follow-up, there remain limitations to the study. Our pain measures do not provide information about source, nature, or treatment of pain. In addition, our pain measures elicit retrospective reports of pain experienced over a 1-month period, and reporting questions about pain intensity and interference may have overlapping meanings to some research participants. One solution to this issue in future studies is prospectively collect information about daily pain intensity and interference over the course of weeks or months. An addition, due to the design of study, we did not have access to medical records of participants and therefore medical history and comorbidities were based on self-reports. Furthermore, the residual confounding due to unknown or unmeasured confounders such as physical activity, diet, or genetic factors that could predis-pose to both pain and cognitive function and effect of medications that are not intended for treatment of pain but affect its perception, were not assessed in this study. Future research is needed to isolate the specific psychological and biological elements of pain interference that drive the relationship between pain and cognitive impairment to better understand the underlying mechanistic pathways and identify intervention strategies.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study of community-based older adults demonstrates that pain interference is an independent predictor of dementia. Since pain is a potential remediable risk factor for dementia, the mechanisms that link pain interference to cognitive decline merit further exploration. Pain interference has huge potential for being targeted with a variety of interventions such as Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), mindfulness and yoga, group-based therapy, physical and occupational therapies, and pharmacologic treatments, which could in turn decrease incident dementia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants NIA 2 P01 AG03949, NIA 1R01AG039409–01, NIA R03 AG045474, NIH K01AG054700, the Leonard and Sylvia Marx Foundation, and the Czap Foundation.

Footnotes

ROLE OF THE SPONSOR

The National Institute on Aging and other sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Study protocols were approved by the Einstein institutional review board.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals were used for studies that are basis of this research. All humans research procedures followed were in accordance with the standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki principles of 1975, as revised in 2013 (http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/node/3931).

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at study entry.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- [1].Alzheimer’s A: 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dementia: J Alzheimer’s Association 11: 332 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. New Engl J Med 368: 1326–34 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol 10: 819–28 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jakobsson U, Klevsgard R, Westergren A, Hallberg IR. Old people in pain: a comparative study. J Pain Symp Managem 26: 625–36 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mantyselka PT, Turunen JH, Ahonen RS, Kumpusalo EA. Chronic pain and poor self-rated health. JAMA 290: 2435–42 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Whitlock EL, Diaz-Ramirez LG, Glymour MM, Boscardin WJ, Covinsky KE, Smith AK. Association between persistent pain and memory decline and dementia in a longitudinal cohort of elders. JAMA Intern Med 177(8): 1146–53 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Moriarty O, McGuire BE, Finn DP. The effect of pain on cognitive function: a review of clinical and preclinical research. Prog Neurobiol 93: 385–404 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Berryman C, Stanton TR, Bowering KJ, Tabor A, McFarlane A, Moseley GL. Evidence for working memory deficits in chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PAIN 154: 1181–96 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Poblador-Plou B, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Marta-Moreno J, Hancco-Saavedra J, Sicras-Mainar A, et al. Comorbidity of dementia: a cross-sectional study of primary care older patients. BMC Psychiatry 14: 84 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cleeland C, Ryan K. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore 23(2): 129–38 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Scherder EJ, Eggermont L, Plooij B, Oudshoorn J, Vuijk PJ, Pickering G, et al. Relationship between chronic pain and cognition in cognitively intact older persons and in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Gerontology 54: 50–58 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Suhr JA. Neuropsychological impairment in fibromyalgia: relation to depression, fatigue, and pain. J Psychosomatic Res 55: 321–29 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Morley S, Pallin V. Scaling the affective domain of pain: a study of the dimensionality of verbal descriptors. Pain 62: 39–49 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Povedano M, Gascón J, Gálvez R, Ruiz M, Rejas J. Cognitive function impairment in patients with neuropathic pain under standard conditions of care. J Pain Symp Managem 33: 78–89 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rodríguez-Andreu J, Ibáñez-Bosch R, Portero-Vázquez A, Masramon X, Rejas J, Gálvez R. Cognitive impairment in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome as assessed by the mini-mental state examination. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord 10: 1 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].van der Leeuw G, Eggermont LH, Shi L, Milberg WP, Gross AL, Hausdorff JM, et al. Pain and cognitive function among older adults living in the community. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 71(3): 398–405 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Iezzi T, Duckworth MP, Vuong LN, Archibald YM, Klinck A. Predictors of neurocognitive performance in chronic pain patients. Intern J Behav Med 11: 56–61 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, Le Resche L. Graded chronic pain status: an epidemiologic evaluation. Pain 40: 279–91 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Katz MJ, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Zimmerman ME, Sanders AE, Verghese J, et al. Age and sex specific prevalence and incidence of mild cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia in blacks and whites: a report from the Einstein Aging Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 26: 335 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sanders AE, Wang C, Katz M, Derby CA, Barzilai N, Ozelius L, et al. Association of a functional polymorphism in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) gene with memory decline and incidence of dementia. JAMA 303: 150–58 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Quality Metric Inc (2000). [Google Scholar]

- [22].Brazier J, Walters S, Nicholl J, Kohler B. Using the SF-36 and Euroqol on an elderly population. Qual Life Res 5: 195–204 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) recent evidence and development of a shorter violence. Clin Gerontologist 5: 165–73 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- [24].Marc LG, Raue PJ, Bruce ML. Screening performance of the 15-item geriatric depression scale in a diverse elderly home care population. Am J Geriatric Psychiat 16: 914–21 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease Report of the NINCDS‐ADRDA Work Group* under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34: 939–39 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 81: 515–26 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- [27].Scemes E, Zammit AR, Katz MJ, Lipton RB, Derby CA. Associations of cognitive function and pain in older adults. Intern J Geriatric Psychiat 32: 118 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kroenke K, Wu J, Bair MJ, Krebs EE, Damush TM, Tu W. Reciprocal relationship between pain and depression: a 12-month longitudinal analysis in primary care. J Pain 12: 964–73 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, Tang L, Williams JW Jr, Kroenke K, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290: 2428–29 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kroenke K, Shen J, Oxman TE, Williams JW, Dietrich AJ. Impact of pain on the outcomes of depression treatment: results from the RESPECT trial. Pain 134: 209–15 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jorm AF. History of depression as a risk factor for dementia: an updated review. Australian New Zealand J Psychiat 35: 776–81 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Szekely CA, Breitner JC, Fitzpatrick AL, Rea TD, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, et al. NSAID use and dementia risk in the Cardiovascular Health Study* Role of APOE and NSAID type. Neurology 70: 17 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dublin S, Walker RL, Gray SL, Hubbard RA, Anderson ML, Yu O, et al. Prescription opioids and risk of dementia or cognitive decline: a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc 63: 1519–26 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Ciszewski A, Kasai K, Lasko NB, Orr SP, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nat Neurosci 5: 1242–47 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dai J, Buijs R, Swaab D. Glucocorticoid hormone (cortisol) affects axonal transport in human cortex neurons but shows resistance in Alzheimer’s disease. Brit J Pharmacol 143: 606–10 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev 87: 873–904 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].May A Chronic pain may change the structure of the brain. PAIN 137: 7–15 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schroeter ML, Stein T, Maslowski N, Neumann J. Neural correlates of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: a systematic and quantitative meta-analysis involving 1351 patients. NeuroImage 47: 1196–1206 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dickerson BC, Bakkour A, Salat DH, Feczko E, Pacheco J, Greve DN, et al. The cortical signature of Alzheimer’s disease: regionally specific cortical thinning relates to symptom severity in very mild to mild AD dementia and is detectable in asymptomatic amyloid-positive individuals. Cerebral Cortex 19: 497–510 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dickerson BC, Wolk DA. MRI cortical thickness biomarker predicts AD-like CSF and cognitive decline in normal adults. Neurology 78: 84–90 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]