The ability to respond flexibly in a dynamic and ever-changing world is critical for adaptive functioning. Switching from one activity to another, changing strategies when an initial strategy is no longer effective, alternating between languages, or taking multiple peoples’ perspectives all require flexibility. As a core component of executive functions, cognitive flexibility allows for such flexibility in switching across tasks, rules, operations, and perspectives based on changes in goals and environmental demands (Carroll, Blakey, & FitzGibbon, 2016; Diamond, 2013). Consistent with theoretical work underscoring the key role of flexibility for academic and social competencies (e.g., Bull & Lee, 2014; Jacques & Zelazo, 2005), cognitive flexibility has been shown to predict math and reading performance (Cartswright, 2015; Colé, Duncan, & Blaye, 2014; Yeniad, Malda, Mesman, Van Ijzendoorn, & Pieper, 2013), theory of mind (Carlson & Moses, 2001; Müller, Zelazo, & Imrisek, 2005), and social understanding (Bock, Gallaway, & Hund, 2015). These findings suggest that understanding the key contributing factors to the development of cognitive flexibility can help guide prevention and intervention strategies aimed towards enhancing adaptive functioning.

Early childhood is a period of rapid transformation in cognitive flexibility, particularly with respect to the ability to adjust responses based on changes in explicit rules (Bunge & Zelazo, 2006). For example, young children quickly learn how to sort cards based on one rule (e.g., color) but fail at changing their responses if asked to switch to another rule (e.g., shape, Kirkham, Cruess, & Diamond, 2003; Zelazo, Frye, & Rapus, 1996). However, from around 4 to 6 years of age, children not only show improvements in adjusting their responses based on a new rule but also demonstrate increased competence in alternating back and forth between two different rules (Carlson, 2005; Clark et al., 2013; Hongwanishkul, Happaney, Lee, & Zelazo, 2010). Although an important body of work has identified specific cognitive processes that support children’s cognitive flexibility (e.g., Cragg & Chevalier, 2012), less is known about whether and how contextual factors such as caregiving behaviors contribute to the development of cognitive flexibility during early childhood. The goal of this study was to examine whether caregivers’ emotional and cognitive support during a problem-solving context predict improvements in children’s cognitive flexibility from preschool to first grade. An additional goal was to examine whether children’s cognitive flexibility leads to changes in caregivers’ supportive behaviors during early childhood.

Cognitive flexibility is a complex form of executive functions, which together refer to volitional attentional and cognitive processes supported largely by the prefrontal cortex that serve to manage goal-directed behaviors (Best & Miller, 2010; Diamond, 2013). Improvements in cognitive flexibility during early childhood may depend partially on the growth of the lateral regions of the prefrontal cortex that support the ability to represent complex rules (Bunge & Zelazo, 2006) and increases in other executive functions such as working memory and inhibitory control (Kirkham & Diamond, 2003; Munakata, Snyder, & Chatham, 2012). Specifically, inhibitory control may support cognitive flexibility by allowing children to inhibit distracting information whereas working memory may help resolve conflict, particularly by strengthening goal representations (Blakey, Visser, & Carroll, 2016; Munakata et al., 2012). Given these underpinnings of cognitive flexibility, understanding the influences of caregiving on cognitive flexibility requires adopting a broader theoretical perspective on the impact of caregiving on the growth of the prefrontal cortex and executive functions in early childhood.

Caregiving experiences constitute one of the most critical and enduring components of proximal experiences during early childhood. Given that the prefrontal cortex as well as its functions are relatively plastic and therefore highly modifiable by repeated proximal experiences in early childhood (Huttenlocher, 2002; Loman & Gunnar, 2010; Zelazo, 2015), variations in caregiving experiences likely lead to individual differences in cognitive flexibility during this time. However, because caregiving is multidimensional and involves a range of behaviors that may differentially promote or hinder different aspects of development (Grusec & Davidov, 2010; Hughes & Ensor, 2009), it is important to understand which dimensions of caregiving contribute to the development of cognitive flexibility during early childhood. In this study, we examined the roles of two aspects of caregiving in the development of cognitive flexibility: emotional support and cognitive support. Consistent with theoretical work highlighting the importance of collaborative problem-solving for cognitive development (e.g., Gauvain, 2001, Vygotsky, 1978), we examined these caregiving behaviors in problem-solving contexts.

Caregiver emotional support refers to caregivers’ ability to respond to children’s needs in a positive and warm manner, encourage children’s autonomous behaviors, and refrain from using negative responses (e.g., Leerkes, Blankson, O’Brien, Calkins, & Marcovitch, 2011). By responding to children’s emotions and needs in a timely and warm manner, emotionally supportive caregivers likely externally regulate the intensity of children’s physiological arousal and emotions (Calkins, 2011; Calkins & Leerkes, 2011; Kopp, 1982; Sroufe, 1996), allowing them to sustain moderate levels of arousal conducive to effective use and coordination of executive functions (Arnsten, 2009; Blair, 2010; Marcovitch et al., 2010). As such, children who are emotionally supported may not only have greater opportunities to use and strengthen their executive functioning skills during problem-solving, but may practice and gradually internalize strategies for regulating their own arousal, attention, and emotions, which, in turn, may support the use and growth of executive functions including cognitive flexibility (Bernier, Carlson, Deschênes, & Matte-Gagné, 2012; Fox & Calkins, 2003; Ursache, Blair, Stifter, & Voegtline, 2013). Moreover, by encouraging children’s self-directed and autonomous behaviors (rather than constraining them), emotionally supportive caregivers likely support children’s ability to flexibly generate and execute novel strategies and plans for achieving a goal, which may facilitate growth in cognitive flexibility. Children who are emotionally supported during problem-solving activities may also develop a positive attitude towards cognitively challenging tasks and engage in such activities more frequently, which may be critical for the development of cognitive flexibility as well as other executive functions.

Previous empirical work provided some support for the proposed associations between caregiver emotional support and child cognitive flexibility in early childhood. Mothers’ emotional support at age 4 was associated positively with children’s cognitive flexibility and executive functioning one year later (Zeytinoglu, Calkins, Swingler, & Leerkes, 2017). Likewise, parental sensitivity and responsiveness at age 3 were associated positively with overall executive functioning at age 6, accounting for executive functioning at age 3 (Blair, Raver, & Berry, & the Family Life Project Investigators 2014), whereas negative behaviors were associated with lower executive functioning (Cuevas et al., 2014). Finally, a latent construct of parenting composed of both emotional (i.e., warm acceptance, contingent responsiveness) and cognitive (i.e., verbal scaffolding) aspects of support predicted conflict executive functions 6.5 months later; despite the low or statistically non-significant concurrent associations between parenting behaviors and executive functions (Merz, Landry, Montroy, & Williams, 2017).

In addition to supporting children’s emotional needs, caregivers also provide support and scaffolding of children that is more targeted to their cognitive processing and problem solving. Caregiver cognitive support is conceptualized as provision of appropriate information about the task at hand through explanations and demonstrations (e.g., how to use a die), supporting children’s ability to count or read, and describing the use or relevance of the components of the task (e.g., cash register) in daily life (Fagot & Gauvain, 1997). By helping children understand and comply with the rules of a game, for example, caregivers who provide cognitive support may support children’s ability to focus and engage in the task more competently (Eisenberg et al., 2010), thereby allowing them to use executive functions such as remembering the rules or thinking more flexibly during the task. Although limited work has examined the role of cognitive assistance in children’s cognitive development, Fagot and Gauvain (1997) found that mothers’ cognitive assistance in toddlerhood predicted children’s cognitive task performance at age 5. Likewise, Eisenberg et al. (2010) reported concurrent positive associations between mothers’ cognitive assistance and children’s attention and persistence; however, did not find longitudinal effects from cognitive assistance to children’s effortful control.

Importantly, a large body of work examining the influence caregivers’ cognitive support on executive functioning focuses on scaffolding, which is defined as a process that involves both the external regulation of children’s emotions (i.e., “frustration control”) and provision of cognitive support (i.e., “marking critical features,” Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976). As such, caregiver scaffolding, measured both as an emotional and cognitive support process, has been shown to predict children’s executive functioning (e.g., Hammond, Müller, Carpendale, Bibok, & Liebermann-Finestone, 2012; Hughes & Ensor, 2009). However, these findings cannot elucidate the relative contributions of caregivers’ emotional versus cognitive support on the development of children’s cognitive flexibility. Thus, examining the influence of emotional and cognitive support on cognitive flexibility across the period of childhood is important.

Finally, although most research focuses on understanding the influence of caregiving on the development of children’s executive functions, an important body of work in the parenting literature suggests that children’s own characteristics such as self-regulatory competencies may influence the caregiving behaviors that they receive from their caregivers (e.g., Bridgett et al., 2009; Perry, Mackler, Calkins, & Keane, 2013). Thus, understanding whether children’s cognitive flexibility may influence the type of caregiving they receive is critical. Given that children with greater cognitive flexibility may respond to their caregivers’ behaviors in more competent and flexible ways, they may evoke more emotionally and cognitively supportive behaviors. Alternatively, children with lower cognitive flexibility may elicit greater cognitive support given that they may need more support with problem-solving.

Few studies have examined the influence of children’s executive functioning on caregiver behaviors. Blair et al. (2014) found that greater child executive functioning at age 3 predicted lower declines in parenting quality from age 3 to 6, providing support for the idea that child executive functioning may influence parenting over time. Likewise, Eisenberg et al. (2010) showed that greater child effortful control – a construct similar to executive functions (Bridgett, Oddi, Laake, Murdock, & Bachmann, 2013) – predicted greater cognitive assistance and lower directiveness from mothers over time. In another study, child conflict executive functioning did not predict later parenting (Merz, Landry, Montroy, et al., 2017). Given the mixed findings, more research is needed to understand whether child cognitive flexibility influences caregiving.

Given that most research examining the relations between caregiving and children’s executive functions assessed only one aspect of caregiving, it is important to examine the roles of specific aspects of caregiving in relation to the changes in cognitive flexibility across early childhood. Moreover, the vast majority of studies examining the links between caregiving and children’s executive functioning relied on concurrent associations or utilized only two time-points, and therefore less is known about the specific timing of caregiver or child influences during childhood. Examining the influences of mothers’ supportive behaviors on children’s cognitive flexibility over a three-year study can elucidate on whether maternal support contributes to the development of cognitive flexibility earlier in development or across the three-year period. Understanding when during development maternal support exerts influence on children’s cognitive flexibility can highlight specific periods during which parenting-focused intervention work may have stronger effects on children’s functioning.

The main goal of the current study was to examine the bidirectional associations between mothers’ emotional and cognitive support during problem-solving and child cognitive flexibility from preschool to first grade utilizing a three-wave design. We addressed three main questions. First, we examined whether maternal emotional support predicts children’s cognitive flexibility in subsequent years. We hypothesized that maternal emotional support would predict child cognitive flexibility from preschool to kindergarten, and kindergarten to the first grade, such that greater maternal emotional support would relate to greater cognitive flexibility in the following year. Second, we examined whether maternal cognitive support predicts children’s cognitive flexibility. Given the mixed findings on the influence of mothers’ cognitive support on children’s effortful and executive control (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2010), our analyses regarding the influence of cognitive support on child cognitive flexibility was exploratory. Third, we examined whether child cognitive flexibility predicts maternal behaviors. Based on previous findings showing that child effortful control and executive functions predict later parenting (e.g., Blair et al., 2014; Eisenberg et al., 2010), we expected child cognitive flexibility to predict more supportive behaviors.

We examined these questions systematically using a series of structural equation modeling analyses. First, using confirmatory factor analysis, we constructed latent variables for mothers’ emotional support using indicators of emotional responsiveness, reversed intrusiveness, and reversed negativity at each time point. Given the importance of measuring the same construct consistently across time, we tested the measurement invariance of emotional support to assess whether this construct was manifested the same way at each time point. Following this preliminary step, we conducted auto-regressive cross-lagged panel models to examine the bidirectional associations between mothers’ emotional and cognitive support, and children’s cognitive flexibility, controlling for the stability in these constructs over time as well as the effects of potential covariates in the model.

Method

Participants

The sample for this study was 278 children (55% girls) and their primary caregivers (96% mothers) who participated in a longitudinal study examining physiological, cognitive, and emotional precursors of early academic readiness. Children’s mean age at the preschool, kindergarten, and first grade visits were 56.37 (SD=4.68), 70.80 (SD = 3.86), and 82.76 (SD=4.02) months, respectively. At the preschool visit, mothers’ ages ranged from 19 to 58 (M=35) and approximately 61% of mothers had a 4-year college degree or had completed higher levels of education. Average income-to-needs ratio, calculated by dividing the total family income by the poverty threshold for that family size, was 2.11 (SD=1.41). In terms of race and ethnicity, the sample was considerably diverse with 59% of the children reported as European American, 30% as African American, and 11% as other races; 6.5% of the sample identified as Hispanic. Of the 278 participants in the original sample, 249 returned for the kindergarten visit and 240 returned for the first grade visit. Participants who did not return for the last visit did not differ from the remaining participants with respect to gender, minority status, maternal education, observed caregiver behaviors, or child cognitive flexibility.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from daycare centers, local establishments (e.g., children’s museum) or via participant referral in a midsized Southeastern city in the United States. Laboratory visits were scheduled with caregivers who either called the research center or returned their contact information to be contacted by the researchers. Data were collected from participants at preschool, kindergarten and first grade. The mean of the first time interval (between the preschool and the kindergarten visits) was 440 days (SD=62) and the second time interval (between the kindergarten and the first grade visits) was 364 days (SD=32 days). Mothers provided written consent before each visit, which lasted for approximately 2 hours. During each visit, mothers filled in questionnaires and participated in a mother-child interaction task, and children participated in a battery of tasks designed to assess their cognitive and emotional development. Mothers received monetary compensation for their participation, and children selected a small toy at the completion of the visit. All procedures were approved by the university institutional review board.

Measures

Demographics

Mothers reported their age and education, children’s birth date and minority status (0=non-Hispanic White, 1=other).

Maternal behaviors

Maternal behaviors were observed during a 7-minute long semi-structured planning and problem-solving mother-child interaction task. The interactive task was a board game that required mother–child dyads to follow multiple steps to get a bear figurine to accomplish a goal. At preschool, the goal was to get to a treasure chest, which required getting a key to unlock a boat and take the boat across the river to the chest (Leerkes et al., 2011). At kindergarten, the goal was to complete a series of chores before going to a birthday party (Neitzel & Stright, 2003). At first grade, the goal was to collect only the groceries on a list in a grocery store before checking out (Leerkes et al., 2011). The experimenter explained the game and then left the room. The interactions were recorded and later coded by trained coders.

The quality of mother–child interactions were rated on 5-point global rating scales ranging from 1 (low) to 5 (high) for cognitive support and the indicators of emotional support: emotional responsiveness, intrusiveness, and negativity. Cognitive support indicated the extent to which mothers provided appropriate information about the task (e.g., move the figurine based on the number on the die), used demonstrations (e.g., how to count), linked the task to daily life (e.g., how to pay at cash registry), and provided opportunities for learning (e.g., help count or read). Emotional responsiveness reflected the extent to which mothers appropriately responded to their children’s needs and emotions, appeared to enjoy being with their children, provided positive reinforcement, and minimized potential problems that could disrupt the game. Intrusiveness indicated the extent to which the mother took over the game without allowing the child to explore and experience it on his or her own. Negativity indicated the extent to which the mother displayed negative verbal or nonverbal emotions toward the child, such as irritability, impatience, or direct criticism. At each time point, interrater reliability was calculated based on approximately 15% double coded cases. Intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from .71 to .91 (p<.01) as reported in Table 1. Observed parenting measures have been shown to have better predictive validity over other measures including self-report measures of parenting (e.g., Zaslow et al., 2006) and have good predictive validity in different ethnic groups (e.g., Merz et al., 2017; Zaslow et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Descriptive information for the cognitive flexibility variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Post-switch, preschool | – | ||||

| 2. Post-switch, kindergarten | .31** | – | |||

| 3. Post-switch, grade 1 | .18* | .36** | – | ||

| 4. Borders, kindergarten | .24** | .28** | .18** | – | |

| 5. Borders, grade 1 | .21** | .30** | .22** | .43** | – |

|

| |||||

| Min | .00 | .00 | .00 | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Max | 30.00 | 30.00 | 30.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 |

| Mean | 20.14 | 25.11 | 28.04 | 7.48 | 8.48 |

| SD | 9.94 | 7.96 | 4.78 | 2.25 | 2.49 |

| N | 274 | 249 | 240 | 248 | 240 |

Note. Post-switch (30 trials) and Borders (12 trials) conditions of the Dimensional Change Card Sort (DCCS) task.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Cognitive flexibility

Cognitive flexibility was measured using a computerized version of The Dimensional Change Card Sort task (DCCS; Espinet, Anderson, & Zelazo, 2012). Children were presented with stimuli that varied across two dimensions: color and shape (e.g., red rabbit and blue boat). In the pre-switch block, which included 15 trials, children were asked to sort the stimuli according to one dimension (i.e., shape). Children who performed at or below chance (7 or fewer correct trials out of 15) during pre-switch were considered to fail this task and were given a score of 0 for their post-switch score. This strategy allowed us to ensure that all children who received a post-switch score understood the basic rule of the game. At preschool, 4 children and at kindergarten 2 children failed this block; however, at first grade, all children passed this block. In the post-switch block, which included 30 trials, children were asked to sort the stimuli according to the other dimension (i.e., color). Children sorted stimuli by pressing the appropriate buttons. In the borders block (also referred to as advanced DCCS), which included 12 trials, children were instructed to sort stimuli on one dimension (i.e., color) if the picture had a border around it but the other dimension (i.e., shape) if the picture did not have a border (Zelazo, 2006). Post-switch performance was scored as the number of correct responses out of 30 trials, whereas borders performance was scored as the number of correct responses out of 12. At the preschool visit, the post-switch block was used, and at the kindergarten and first grade visits, both post-switch and the more advanced borders blocks were used to increase task difficulty to match children’s developmental level. For the primary analyses of the study, post-switch and borders scores were converted into percent accuracy scores. At kindergarten and first grade, post-switch and borders percent accuracy scores were correlated (see Table 1) and thus these scores were averaged to create an overall cognitive flexibility composite score. Higher scores indicated greater cognitive flexibility. The DCCS has been shown to have good concurrent (e.g., Caughy, Mills, Owen, & Hurst, 2013; Masten et al., 2012) and predictive (e.g., Obradović, 2010) validity across different racial/ethnic and SES groups.

Data Analytic Plan

Data was examined for missing values, outliers, and normality of distributions. For the primary analyses, we conducted a series of structural equation modeling analyses in Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). A maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR) was used to adjust the standard errors for non-normality. Missing data was handled using full information maximum likelihood. Model fit was evaluated using the comparative fit index (CFI; values greater than .90 indicate acceptable model fit), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; upper confidence interval values lower than .08 indicates that “not close/acceptable fit” hypothesis can be rejected), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR; estimates lower than .08 are considered good fit; Little, 2013). Consistent with the MLR approach, Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference tests were used to evaluate relative fit across nested models. A significant result from the chi-square difference test indicates that the inclusion of the new paths improved the model fit (Satorra & Bentler, 2001).

First, we used confirmatory factor analyses to establish latent factors of maternal emotional support at each time point and tested their invariance across time. Measurement invariance analyses can help determine whether the same latent construct, in this case emotional support, was measured in a consistent way across time. Evidence of metric invariance or equal factor loadings suggests that the construct was manifested the same way across time (Kline, 2011). After establishing our measurement model, we conducted a series of longitudinal panel models to test our main hypotheses. This approach was selected because cross-lagged models can provide strong tests for the effect of one construct on another construct by controlling for the stability of constructs over time, covariation among independent variables, and within-time covariation among constructs’ residual errors (Little, 2013).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

The percentage of missing data was small, ranging from 0% to 14%. Grubbs’ (1969) test was used to evaluate whether extreme values were outliers at the 95% significance level. At first grade, five children’s overall cognitive flexibility percentage scores (i.e., all below 3.29 SD) were detected as outliers, and therefore were replaced with the next lowest value (Grubbs, 1969; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Descriptive information and correlations for the raw cognitive flexibility scores are presented in Table 1. Descriptive information and correlations among the variables used in the primary analyses are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The mean of cognitive flexibility scores increased from preschool to subsequent visits, suggesting that, on average, children’s cognitive flexibility improved over time.

Table 2.

Descriptive information for the study variables

| N | ICC | Min | Max | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive flexibility, preschool | 274 | .00 | 100.00 | 67.12 | 33.14 | |

| Cognitive flexibility, kindergarten | 249 | 18.33 | 100.00 | 72.93 | 18.41 | |

| Cognitive flexibility, grade 1 | 240 | 40.00 | 100.00 | 82.37 | 13.28 | |

| Emotional responsiveness, preschool | 276 | .90 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.84 | 1.03 |

| Emotional responsiveness, kindergarten | 249 | .85 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.86 | 1.00 |

| Emotional responsiveness, grade 1 | 238 | .90 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.87 | .89 |

| Intrusiveness, preschool | 276 | .89 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.01 | 1.18 |

| Intrusiveness, kindergarten | 249 | .76 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.56 | .90 |

| Intrusiveness, grade 1 | 239 | .76 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.80 | 1.19 |

| Negativity, preschool | 276 | .91 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.69 | .98 |

| Negativity, kindergarten | 249 | .94 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.22 | .60 |

| Negativity, grade 1 | 239 | .80 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.44 | .87 |

| Cognitive support, preschool | 276 | .76 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 | .95 |

| Cognitive support, kindergarten | 249 | .71 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.82 | .81 |

| Cognitive support, grade 1 | 236 | .86 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.38 | .82 |

Note. ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient. Cognitive flexibility (observed, percent scores). Maternal emotional responsiveness, intrusiveness, negativity, and cognitive support (observed, 1–5 scale).

Table 3.

Correlations among the study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal education | – | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Child age | −.02 | – | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Minority status | −.25** | −.08 | – | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Cognitive flexibility, preschool | .19** | .20** | −.24** | – | |||||||||||||

| 5. Cognitive flexibility, kindergarten | .24** | .05 | −.38** | .34** | – | ||||||||||||

| 6. Cognitive flexibility, grade 1 | .18** | .04 | −.31** | .23** | .51** | – | |||||||||||

| 7. Emotional responsivity, preschool | .29** | .00 | −.21** | .16** | .22** | .13* | – | ||||||||||

| 8. Emotional responsivity, kindergarten | .32** | .05 | −.20** | .09 | .12 | .06 | .48** | – | |||||||||

| 9. Emotional responsivity, grade 1 | .29** | .08 | −.23** | .12 | .17* | .12 | .46** | .51** | – | ||||||||

| 10. Intrusiveness, preschool | −.33** | −.27** | .43** | −.37** | −.33** | −.28** | −.48** | −.30** | −.38** | – | |||||||

| 11. Intrusiveness, kindergarten | −.29** | −.09 | .30** | −.22** | −.32** | −.28** | −.32** | −.39** | −.40** | .47** | – | ||||||

| 12. Intrusiveness, grade 1 | −.22** | −.14* | .26** | −.20** | −.22** | −.24** | −.29** | −.18** | −.54** | .52** | .45** | – | |||||

| 13. Negativity, preschool | −.33** | −.14* | .36** | −.32** | −.29** | −.26** | −.53** | −.35** | −.40** | .67** | .50** | .43** | – | ||||

| 14. Negativity, kindergarten | −.25** | −.12 | .26** | −.21** | −.19** | −.17** | −.27** | −.35** | −.35** | .37** | .52** | .36** | .55** | – | |||

| 15. Negativity, grade 1 | −.22** | −.06 | .24** | −.14* | −.19** | −.17** | −.27** | −.24** | −.54** | .40** | .40** | .69** | .42** | .45** | – | ||

| 16. Cognitive support, preschool | .11 | −.17** | .00 | −.12* | .02 | .08 | .39** | .30** | .25** | −.08 | −.15* | −.09 | −.06 | −.08 | −.12 | – | |

| 17. Cognitive support, kindergarten | .11 | −.04 | −.03 | −.16* | −.10 | −.13* | .08 | .27** | .06 | .09 | −.01 | .06 | .03 | −.03 | −.01 | .20** | – |

| 18. Cognitive support, grade 1 | .20** | −.09 | −.08 | −.11 | .01 | −.03 | .13* | .25** | .20** | −.01 | −.06 | .01 | −.02 | −.02 | −.01 | .24** | .17* |

Note. N = 236–276. Minority status is a categorical variable (0 = non-Hispanic White, 1 = minority). Maternal education (self-report, 1–7; 1 = some high school, 7 = graduate degree); cognitive flexibility (observed, percent scores); maternal emotional responsiveness, intrusiveness, negativity, and cognitive control (observed, 1–5 scale).

p < .05

p <.01.

Maternal education, child’s age, minority status, and gender were examined as potential covariates. Gender was not associated with cognitive flexibility at any time point (p >.05), and therefore was not included as a covariate. As shown in Table 3, higher maternal education was associated with greater levels of child cognitive flexibility (r= .18–.24, p <.05) and greater maternal emotional support (higher emotional responsiveness, lower intrusiveness & negativity) at each time point (r = −.33–.29, p <.01), and greater maternal cognitive support in the first grade (r =.20, p <.01). Children’s age at the preschool visit was associated positively with cognitive flexibility (r=.21, p <.01) and negatively with maternal cognitive support (r = −.17, p<.01), negativity (r = −.14, p <.05), and intrusiveness (r = −.27, p<.01), such that older children demonstrated greater cognitive flexibility and received more cognitive support and less negativity and intrusiveness from their mothers. Child minority status was associated with all study variables except for mothers’ cognitive support at each time point (see Table 3, column 3). Overall, children identified as White non-Hispanic demonstrated better cognitive flexibility than children from minority backgrounds (r = −.22– −.38, p<.01) and were exposed to greater levels of emotionally supportive caregiver behaviors (r = −.21–.36, p < .01). Based on these analyses, we included maternal education, and child age and minority status as covariates.

At each time point, several indicators of maternal emotional support were associated with cognitive flexibility in the expected directions, such that greater emotional support was linked with better child cognitive flexibility (see Table 3). Child cognitive flexibility in preschool was associated negatively with maternal cognitive support in preschool (r = −.13, p <.05). Maternal cognitive support and emotional responsiveness were correlated positively across all time points (r = .20–.39, p <.01), such that mothers who provided more cognitive support were emotionally more responsive.

Primary Analyses

First, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses to establish latent factors of maternal emotional support at each time point and tested their equivalence over time. The baseline model, which did not include any parameter constraints, evidenced excellent fit to the data χ2(15) =10.62, p=.78, CFI =1.00, RMSEA =.00 (.00−.04), SRMR = .02. Constraining the factor loadings of the same indicators to be equal across all time points resulted in a good fitting model χ2(19) =29.20, p =.06, CFI = .99, RMSEA =.04 (.00-.07), SRMR=.07. However, the relative fit test suggested that compared to the baseline model there was a decrement in model fit ∆χ2(4) =17.13, p =.002. After allowing negativity in kindergarten to vary freely, model fit the data well χ2(18) = 16.49 p = .56, CFI=1.00, RMSEA=.00 (.00-.05), SRMR=.042 and did not fit worse than the baseline model, ∆χ2(3) = 5.52, p =.14, suggesting that there was partial metric invariance of the emotional support construct over time.

After establishing our measurement model, we conducted longitudinal cross-lagged panel models to test our main hypotheses. The first model with the stability and cross-lagged paths had acceptable model fit, χ2(64) = 136.92, CFI =.93, RMSEA =.06 (.05–.08), SRMR=.06. Next, we included the covariates (maternal education, child minority status and child age) into the model. Consistent with the parsimony principle, paths that did not reach significance and improve model fit were not included in the final model (Kline, 2005).

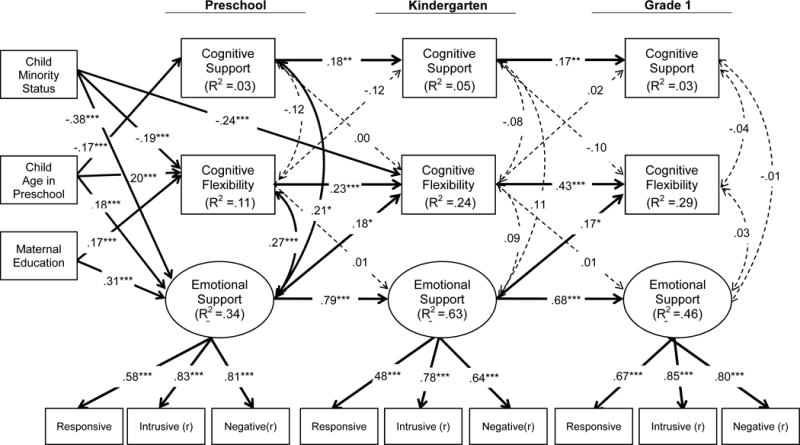

The final model including the covariates fit the data well, χ2(101) = 190.74, CFI =.93, RMSEA =.06 (.04-.07), SRMR=.07. Standardized path coefficients for this final model are presented in Figure 1 and unstandardized coefficients are presented in Table 4. The stability coefficients of all constructs were positive and statistically significant (cognitive flexibility: B = .13, B = .31, p < .001; emotional support: B = .64, B = .85, p < .001; cognitive support: B = .15 p = .006 and B = .17 p = .012, as reported chronologically). As predicted, greater maternal emotional support in preschool predicted greater child cognitive flexibility in kindergarten (B =5.64, 95% CI [.211–11.065], p =.04), and greater maternal emotional support in kindergarten predicted greater child cognitive flexibility in first grade (B =4.83, 95% CI [.381–9.274], p = .03). Mothers’ cognitive support did not predict children’s cognitive flexibility. Child cognitive flexibility did not predict maternal behaviors. The same paths remained statistically significant when the outliers on the cognitive flexibility task were removed from the sample.

Figure 1.

Standardized estimates from the structural autoregressive cross-lagged panel model testing the paths among maternal emotional and cognitive support, and child cognitive flexibility.

Note. N = 278. Dashed paths are statistically non-significant. *p < .05, **p <.01, ***p < .005. 95% confidence intervals are included in Table 4.

Table 4.

Unstandardized estimates of the paths from the cross-lagged autoregressive structural regression model.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | Confidence Intervals (95%) |

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Stability paths | |||||||

| Cognitive flexibility, preschool | → | Cognitive flexibility, kindergarten | .13 | .04 | .057 | .198 | .000 |

| Cognitive flexibility, kindergarten | → | Cognitive flexibility, grade 1 | .31 | .05 | .208 | .416 | .000 |

| Emotional support, preschool | → | Emotional support, kindergarten | .64 | .10 | .447 | .825 | .000 |

| Emotional support, kindergarten | → | Emotional support, grade 1 | .85 | .13 | .599 | 1.110 | .000 |

| Cognitive support, preschool | → | Cognitive support, kindergarten | .15 | .06 | .044 | .262 | .006 |

| Cognitive support, kindergarten | → | Cognitive support, grade 1 | .17 | .07 | .038 | .304 | .012 |

| Cross-lagged paths | |||||||

| Emotional support, preschool | → | Cognitive flexibility, kindergarten | 5.64 | 2.77 | .211 | 11.065 | .042 |

| Emotional support, kindergarten | → | Cognitive flexibility, grade 1 | 4.83 | 2.27 | .381 | 9.274 | .033 |

| Cognitive support, preschool | → | Cognitive flexibility, kindergarten | .01 | 1.08 | −2.100 | 2.128 | .990 |

| Cognitive support, kindergarten | → | Cognitive flexibility, grade 1 | −1.70 | .91 | −3.486 | .093 | .062 |

| Cognitive flexibility, preschool | → | Emotional support, kindergarten | .00 | .00 | −.001 | .002 | .839 |

| → | Cognitive support, kindergarten | −.00 | −.00 | −.006 | .000 | .064 | |

| Cognitive flexibility, kindergarten | → | Emotional support, grade 1 | .00 | .00 | −.005 | −.005 | .927 |

| → | Cognitive support, grade 1 | .00 | .07 | −.004 | .006 | .703 | |

| Paths from control variables | |||||||

| Maternal education | → | Emotional support, preschool | .11 | .02 | .060 | .154 | .000 |

| Cognitive flexibility, preschool | 3.23 | 1.18 | .925 | 5.535 | .006 | ||

| Minority status | → | Emotional support, preschool | −.45 | .08 | −.600 | −.303 | .000 |

| → | Cognitive flexibility, preschool | −11.32 | 4.04 | −19.234 | −3.395 | .005 | |

| Cognitive flexibility, kindergarten | −8.71 | 2.71 | −14.006 | −3.377 | .001 | ||

| Child age | → | Emotional support, preschool | .02 | .01 | .008 | .038 | .002 |

| → | Cognitive support, preschool | −.04 | .01 | −.058 | −.016 | .002 | |

| Cognitive flexibility, preschool | 1.41 | .40 | .617 | 2.196 | .000 | ||

Note. N = 278. Cognitive flexibility (observed, percent scores); maternal emotional responsiveness, intrusiveness, negativity, and cognitive control (observed, 1–5 scale); minority status (0 = non-Hispanic White, 1 = minority); and maternal education (self-report, 1–7; 1 = some high school, 7 = graduate degree).

Discussion

In this study, we examined bidirectional longitudinal associations between mothers’ supportive behaviors during problem-solving and children’s cognitive flexibility in a 3-wave study spanning from preschool to first grade. Given the importance of understanding the specific caregiving behaviors that contribute to the improvements in cognitive flexibility in early childhood, we examined two aspects of mothers’ behaviors: emotional and cognitive support. Using cross-lagged autoregressive structural regression analyses, we examined the longitudinal relations between these two aspects of caregiving and children’s cognitive flexibility, accounting for the longitudinal stability of each construct, within-time covariation among the three constructs, as well as the influence of maternal education, and child age and minority status.

Consistent with our expectations, mothers’ emotional support predicted children’s cognitive flexibility from preschool to kindergarten, and kindergarten to first grade, such that greater maternal emotional support was associated with better child cognitive flexibility. Importantly, mothers’ emotional support predicted children’s cognitive flexibility over and above the influence of mothers’ cognitive support on children’s cognitive flexibility and the influence of children’s cognitive flexibility on mothers’ behaviors. Consistent with previous research (Valcan, Davis, & Pino-Pasternak, 2017), the effect sizes of the paths from emotional support to cognitive flexibility in subsequent time points were small but stable across time. Our findings provide additional support for the growing body of evidence linking indicators of caregiver emotional support with children’s executive functioning (Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, 2010; Blair et al., 2014; Cuevas et al., 2014; Merz, Landry, Johnson, Williams, & Jung, 2016). A plausible explanation for the current findings is that experiences with emotionally supportive caregivers during problem-solving may allow children use executive functions more frequently and efficiently. In particular, children who are emotionally supported during problem-solving may sustain optimal stress responses conducive to effective executive functioning (Blair, 2010), engage in the task while relying on volitional thinking strategies, and enjoy seeking cognitively challenging tasks and exerting control, which may ultimately promote the growth of cognitive flexibility. As such, more frequent use of executive functioning skills may strengthen the efficiency of the neural circuity underlying these skills and therefore increase the chances of activation of these skills in the future (Zelazo, Blair, & Willoughby, 2016).

Our findings are also consistent with recent research showing that ordinary variations in emotionally supportive caregiving predict children’s frontal brain functioning responsible for executive functions. In particular, the quality of caregiving behaviors during infancy have been shown to relate to concurrent resting frontal electroencephalography (EEG) power, and increases in resting frontal power over time, suggesting that caregiver behaviors may lead to variations in neural development in infants (Bernier, Calkins, & Bell, 2016). Likewise, caregiver intrusiveness has been shown to predict change in EEG power from baseline to task in left frontal cortex, a neural response linked with infants’ attention behavior (Swingler, Perry, Calkins, & Bell, 2017). Given that these studies were conducted with infants, it remains unclear whether caregiver emotional support contributes to children’s neural development and functioning after infancy. Future research can examine whether caregiving predicts children’s executive functioning through its influence on prefrontal neural functioning in early childhood.

In contrast to the findings on the effects of mothers’ emotional support on child cognitive flexibility, mothers’ cognitive support did not predict children’s later cognitive flexibility. Although we are not aware of any studies that examined the influence of caregivers’ emotional and cognitive support on children’s executive functioning within the same model, our findings are consistent with earlier findings showing that mothers’ emotional support but not cognitive support predicts children’s pre-academic skills from ages 3 to 4 (Leerkes et al., 2011). Notably, mothers provided more cognitive support to children who were younger. This finding may suggest that mothers provide greater cognitive support earlier in development when children may benefit from instructional support to a greater extent. Results from a recent metaanalysis showed that the association between cognitive aspects of parental support and child executive functions was stronger for younger compared to older children (Valcan, Davis, & Pino-Pasternak, 2017). As such, it is possible that cognitive support may contribute to improvements in children’s cognitive flexibility earlier than the period examined in this study.

Another explanation for the null associations between maternal cognitive support and child cognitive flexibility is that our global measure of cognitive support may not have captured the caregiver behaviors that are critical for the development of cognitive flexibility. Therefore, it would be important to identify more specific aspects of cognitive support that lead to improvements in children’s cognitive flexibility. For example, recent experimental studies identified two potential brief interventions that led to subsequent changes in children’s cognitive flexibility: contrastive language and reflection training (Doebel & Zelazo, 2016; Espinet, Anderson, & Zelazo, 2013, respectively). In light of these findings, it would important to examine whether ordinary variations in caregivers’ use of such specific forms of cognitive support (e.g., contrastive language) contribute to improvements in children’s cognitive flexibility. Notably, compared to the emotional support construct, the cognitive support construct was less stable over time. This may either be because caregivers’ cognitive support may be more volatile compared to their emotional support or our global measure of cognitive support may not have captured the stable aspects of cognitive support over time. Thus, it would be critical to examine the influence of caregiver cognitive support on children’s cognitive flexibility using constructs that demonstrate greater stability over time.

Children’s cognitive flexibility did not predict maternal supportive behaviors across time. This finding is consistent with Merz et al.’s (2017) finding that child conflict executive functions, a similar construct to cognitive flexibility assessed via the bear/dragon and DCCS tasks, did not predict parenting. However, there is also evidence showing that children’s executive functioning and effortful control do predict changes in parenting behaviors in early childhood (Blair et al., 2014; Eisenberg et al., 2010). Thus, one explanation for our null findings may be that processes related to children’s cognitive control, when assessed more globally, may be stronger predictors of caregiving than more specific aspects of cognitive control such as cognitive flexibility. Another explanation may be that given that emotional support was highly stable over time perhaps due to our strong measurement of this construct, there was not much variance left to explain after accounting its stability over time. Nevertheless, child executive functioning may predict changes in emotional support over several years when there is greater change in parenting. The inconsistencies in findings regarding the influence of child executive functions on caregiving behaviors, an important next step for future research to identify what aspects of child cognitive functioning may influence which caregiving behaviors during which periods of development.

It is important to note that emotional and cognitive support were associated only modestly in this study. Specifically, across all time points, cognitive support was associated modestly with responsiveness, but not with intrusiveness or negativity, suggesting that this aspect of caregiving is largely independent from overall emotional supportiveness and particularly negative aspects of caregiving. This finding suggests that it is possible for caregivers to provide high levels of cognitive support (e.g., use demonstrations and instructions) in an emotionally non-supportive way such as by using a negative tone of voice or by grasping the figurine from the child’s hand, or to provide low levels of cognitive support while demonstrating high levels of emotional support. Notably, this finding is contrary to findings from previous research that showed moderate levels of association between emotional and cognitive aspects of caregiving (e.g., NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005). For example, Merz et al. (2017) found that parental verbal scaffolding, conceptualized as language input aligned with the child’s developmental needs, was associated moderately with two positive aspects of parenting (i.e., warm acceptance and contingent responding) during free play. One explanation for this discrepancy in the findings may be that cognitive aspects of support may be associated more strongly with positive aspects of emotional support (e.g., responsiveness) than negative aspects (e.g., intrusiveness), as was the case in our study. Another explanation may be related to the conceptualization of cognitive support and in what context it was assessed. For example, it is possible that quality of language input during free play as assessed in Merz et al. may be more strongly associated with emotional aspects of caregiving if the verbal input takes place during conversations regarding children’s social-emotional needs such as likes/dislikes and/or emotions. On the other hand, more instructive forms of verbal and non-verbal cognitive support during more structured problem-solving contexts, as assessed in this study, may be associated only modestly with emotional support because this form of cognitive support less likely involves input regarding children’s social-emotional needs. Notably, previous research has also linked scaffolding with emotionally supportive aspects of caregiving such as warmth (Lengua, Honorado, & Bush, 2007; Zalewski, Lengua, Fisher, Trancik, Bush, & Meltzoff, 2012). This may be due to the fact that the conceptualization of scaffolding in these studies involved aspects of the responsiveness (e.g., interventions contingent on children’s needs) and/or low intrusiveness (i.e., autonomy support), which were considered to be components of emotional support in this study. These findings together underscore the fact that nuances in the conceptualization, assessment method, and the context in which caregiving is observed may have an important role in whether or not distinct aspects of caregiving are associated, and/or whether they predict certain aspects of child executive functions.

This study had several important strengths. We followed our participants across three subsequent years and thus our longitudinal design allowed us to examine the timing of caregiving effects on cognitive flexibility. In addition, we used a large and diverse sample in terms of ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES); adopted strong analytical procedures that allowed us to control for stability in constructs over time and minimize measurement error; and controlled for several covariates including age, minority status, and maternal education. Moreover, we used a careful observational measure of mothers’ supportive behaviors during problem-solving. Notably, one of the challenges of conducting longitudinal research on children’s executive functions is choosing tasks that are developmentally appropriate across the window of time of the study (Carlson, 2005). For example, a task that may be highly challenging for preschool aged children may be too easy for first graders, posing challenges to observe individual differences in performance in older children. We attempted to address this problem via our task selection. In cognitive flexibility tasks such as the DCCS, having more opportunities to practice the initial rule strengthens children’s active mental representations of this rule and therefore makes shifting to a new rule more challenging (see Doebel & Zelazo, 2015). As such, greater number of pre-switch trials (playing the initial rule) has been associated with lower performance in post-switch trials (playing the new rule; Doebel & Zelazo, 2015). By adopting a version of DCCS task that included more pre-switch trials (N=15) than usual measures, we used a more challenging version of the task appropriate for studying change in cognitive flexibility over time. Likewise, we used more trials both in post-switch (N=30) and borders (N=12) blocks to help examine variations in task performance.

Despite these notable strengths, this study had several limitations. First, this study could be strengthened by using multiple measures of cognitive flexibility with respect to children’s rule use. This strategy could have improved the construct validity of cognitive flexibility. Second, although we measured children’s post-switch performance (playing according to a new rule) across all time points, we measured children’s borders performance (switching rules back and forth based on the border cue) at the kindergarten and first grade visits but not at the preschool visit. Therefore, not having the borders block at the preschool visit might have impacted our stability estimate of cognitive flexibility from preschool to kindergarten. Third, emotional support made up of three separate indicators was likely a more reliable construct than cognitive support, which was assessed via a single rating scale. Thus, this discrepancy may at least partially explain why emotional but not cognitive support predicted cognitive flexibility. As such, it is important for future research to examine the influence of emotional and cognitive support on cognitive flexibility or other child outcomes using more reliable cognitive support constructs, possibly with distinct indicators each assessed separately.

Our findings indicated that mothers’ emotional support in interactive problem-solving contexts predicts children’s cognitive flexibility from preschool to kindergarten, and from kindergarten to first grade, suggesting that mothers’ emotional support may be a driving force in the development of cognitive flexibility across early childhood. In contrast, mothers’ cognitive support did not predict changes in cognitive flexibility over time. By examining the roles of mothers’ emotional and cognitive support within the same model, we were able to identify a specific dimension of caregiving that leads to improvements in cognitive flexibility and perhaps executive functioning given that DCCS is considered a measure of executive function (Zelazo, 2006). Thus, prevention and intervention work aimed towards improving caregivers’ emotional responsiveness and reducing negative and intrusive behaviors may potentially lead to improvements in children’s cognitive flexibility and executive functioning in early childhood.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 5R01HD071957 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. The authors wish to express their thanks to the students and staff who assisted with data collection, the families who participated in the study, and Dr. Marion O’Brien who was instrumental in the planning and implementation of this project prior to her death.

References

- Arnsten AFT. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:410–422. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Calkins SD, Bell MA. Longitudinal associations between the quality of mother-infant interactions and brain development across infancy. Child Development. 2016;87:1159–1174. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, Deschênes M, Matte-Gagné C. Social factors in the development of early executive functioning: A closer look at the caregiving environment. Developmental Science. 2012;15:12–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, Whipple N. From external regulation to self-regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children’s executive functioning. Child Development. 2010;81:326–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best J, Miller P. A developmental perspective on executive function. Child Development. 2010;81:1641–1660. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. Stress and the development of self-regulation in context. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4:181–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Raver CC, Berry DJ, The Family Life Project Investigators Two approaches to estimating the effect of parenting on the development of executive function in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:554–565. doi: 10.1037/a0033647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakey E, Visser I, Carroll DJ. Different executive functions support different kinds of cognitive flexibility: Evidence from 2−, 3−, and 4−year–olds. Child Development. 2016;87:513–526. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock A, Gallaway K, Hund A. Specifying links between executive functioning and theory of mind during middle childhood: Cognitive flexibility predicts social understanding. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2015;16:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Gartstein MA, Putnam SP, McKay T, Iddins E, Robertson C, Rittmueller A. Maternal and contextual influences and the effect of temperament development during infancy on parenting in toddlerhood. Infant Behavior and Development. 2009;32:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Oddi KB, Laake LM, Murdock KW, Bachmann MN. Integrating and differentiating aspects of self-regulation: effortful control, executive functioning, and links to negative affectivity. Emotion. 2013;13:47–63. doi: 10.1037/a0029536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull R, Lee K. Executive functioning and mathematics achievement. Child Development Perspectives. 2014;8:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bunge SA, Zelazo PD. A brain-based account of the development of rule use in childhood. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:118–121. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Caregiving as coregulation: Psychobiological processes and child functioning. In: Booth A, McHale SM, Landale NS, editors. Biosocial foundations of family processes. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Leerkes EM. Early attachment processes and the development of emotional self-regulation. In: Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, editors. Handbook of self 1 regulation: Research, theory and applications. 2nd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 355–373. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM. Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28:595–616. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, Moses LJ. Individual differences in inhibitory control and children’s theory of mind. Child Development. 2001;72:1032–1053. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll DJ, Blakey E, FitzGibbon L. Cognitive flexibility in young children: Beyond perseveration. Child Development Perspectives. 2016;10:211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MOB, Mills B, Owen MT, Hurst JR. Emergent self-regulation skills among very young ethnic minority children: A confirmatory factor model. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2013;116:839–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CAC, Sheffield TD, Chevalier N, Nelson JM, Wiebe SA, Espy KA. Charting early trajectories of executive control with the shape school. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:1481–1493. doi: 10.1037/a0030578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colé P, Duncan LG, Blaye A. Cognitive flexibility predicts early reading skills. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:565. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg L, Chevalier N. The processes underlying flexibility in childhood. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2012;5:209–232. doi: 10.1080/17470210903204618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas K, Deater-Deckard K, Kim-Spoon J, Watson AJ, Morasch KC, Bell MA. What’s mom got to do with it? Contributions of maternal executive function and caregiving to the development of executive function across early childhood. Developmental Science. 2014;17:224–238. doi: 10.1111/desc.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A. Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology. 2013;64:135–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebel S, Zelazo PD. A meta-analysis of the Dimensional Change Card Sort: Implications for developmental theories and the measurement of executive function in children. Developmental Review. 2015;38:241–268. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebel S, Zelazo PD. Seeing conflict and engaging control: Experience with contrastive language benefits executive function in preschoolers. Cognition. 2016;157:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Vidmar M, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND, Edwards A, Gaertner B, Kupfer A. Mothers’ teaching strategies and children’s effortful control: a longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1294–1308. doi: 10.1037/a0020236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinet SD, Anderson JE, Zelazo PD. Reflection training improves executive function in preschool-age children: Behavioral and neural effects. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2013;4:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot BI, Gauvain M. Mother-child problem solving: continuity through the early childhood years. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:480–488. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Calkins SD. The development of self-control of emotion: Intrinsic and extrinsic influences. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27:7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gauvain M. The social context of cognitive development. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs FE. Procedures for detecting outlying observations in samples. Technometrics. 1969;11:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Davidov M. Integrating different perspectives on socialization theory and research: a domain-specific approach. Child Development. 2010;81:687–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SI, Müller U, Carpendale JIM, Bibok MB, Liebermann-Finestone DP. The effects of parental scaffolding on preschoolers’ executive function. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48:271–281. doi: 10.1037/a0025519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongwanishkul D, Happaney KR, Lee WSC, Zelazo PD. Assessment of hot and cool executive function in young children: Age-related changes and individual differences. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28:617–644. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CH, Ensor RA. How do families help or hinder the emergence of early executive function? New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2009;9:35–50. doi: 10.1002/cd.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR. Neural Plasticity: The Effects of Environment on the Development of the Cerebral Cortex. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques S, Zelazo PD. Language and the development of cognitive flexibility: Implications for theory of mind. In: Astington JW, Baird JA, editors. Why language matters for theory of mind. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 144–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham NZ, Cruess L, Diamond A. Helping children apply their knowledge to their behavior on a dimension-switching task. Developmental Science. 2003;6:449–467. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham NZ, Diamond A. Sorting between theories of perseveration: Performance in conflict tasks requires memory, attention and inhibition. Developmental Science. 2003;6:474–476. [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Blankson AN, O’Brien M, Calkins SD, Marcovitch S. The relation of maternal emotional and cognitive support during problem solving to pre- academic skills in preschoolers. Infant and Child Development. 2011;20:353–370. doi: 10.1002/icd.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Honorado E, Bush NR. Contextual risk and parenting as predictors of effortful control and social competence in preschool children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:40–55. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Loman MM, Gunnar MR. Early experience and the development of stress reactivity and regulation in children. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller U, Zelazo PD, Imrisek S. Executive function and children’s understanding of false belief: How specific is the relation? Cognitive Development. 2005;20:173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Marcovitch S, Leigh J, Calkins SD, Leerkes EM, O’Brien M, Blankson AN. Moderate vagal withdrawal in 3.5-year-old children is associated with optimal performance on executive function tasks. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52:603–608. doi: 10.1002/dev.20462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz EC, Landry SH, Montroy JJ, Williams JM. Bidirectional associations between parental responsiveness and executive function during early childhood. Social Development. 2017;26:591–609. doi: 10.1111/sode.12204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz EC, Landry SH, Johnson UY, Williams JM, Jung K. Effects of a responsiveness–focused intervention in family child care homes on children’s executive function. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2016;34:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Herbers JE, Desjardins CD, Cutuli JJ, McCormick CM, Sapienza JK, Zelazo PD. Executive function skills and school success in young children experiencing homelessness. Educational Researcher. 2012;41:375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Munakata Y, Snyder HR, Chatham CH. Developing cognitive control: Three key transitions. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2012;21:71–77. doi: 10.1177/0963721412436807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neitzel C, Stright AD. Relations between mothers’ scaffolding and children’s academic self-regulation: Establishing a foundation of self-regulatory competence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:147–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Predicting Individual Differences in Attention, Memory, and Planning in First Graders From Experiences at Home, Child Care, and School. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:99–114. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradović J. Effortful control and adaptive functioning of homeless children: Variable-focused and person-focused analyses. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry NB, Mackler JS, Calkins SD, Keane SP. A transactional analysis of the relation between maternal sensitivity and child vagal regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2013;50:784–793. doi: 10.1037/a0033819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe A. Emotional development: The organization of emotional life in the early years. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Swingler MM, Perry NB, Calkins SD, Bell MA. Maternal behavior predicts infant neurophysiological and behavioral attention processes in the first year. Developmental Psychology. 2017;53:13–27. doi: 10.1037/dev0000187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 6th. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ursache A, Blair C, Stifter C, Voegtline K. Emotional reactivity and regulation in infancy interact to predict executive functioning in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:127–37. doi: 10.1037/a0027728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. In: Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cole M, John-Steiner V, Scribner S, Souberman E, editors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wood D, Bruner JS, Ross G. The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1976;17:89–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeniad N, Malda M, Mesman J, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Pieper S. Shifting ability predicts math and reading performance in children: A meta-analytical study. Learning and Individual Differences. 2013;23:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zalewski M, Lengua LJ, Fisher PA, Trancik A, Bush NR, Meltzoff AN. Poverty and single parenting: Relations with preschoolers’ cortisol and effortful control. Infant and Child Development. 2012;21:537–554. [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD. The Dimensional Change Card Sort (DCCS): A method of assessing executive function in children. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:297–301. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD. Executive function: Reflection, iterative reprocessing, complexity, and the developing brain. Developmental Review. 2015;38:55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD, Frye D, Rapus T. An age-related dissociation between knowing rules and using them. Cognitive Development. 1996;11:37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zaslow MJ, Weinfield NS, Gallagher M, Hair EC, Ogawa JR, Egeland B, De Temple JM. Longitudinal prediction of child outcomes from differing measures of parenting in a low-income sample. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:27. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeytinoglu S, Calkins SD, Swingler MM, Leerkes EM. Pathways from maternal effortful control to child self-regulation: The role of maternal emotional support. Journal of Family Psychology. 2017;31:170–180. doi: 10.1037/fam0000271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]