Abstract

Chronic exposure of human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cells to hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] causes malignant cell transformation. Sirtuin-3 (SIRT3) regulates mitochondrial adaptive response to stress, such as metabolic reprogramming and antioxidant defense mechanisms. In Cr(VI)-transformed cells, SIRT3 was upregulated and mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production and proton leak were reduced. Knockdown of SIRT3 by its shRNA further decreased mitochondrial ATP production, proton leak, mitochondrial mass, and mitochondrial membrane potential, indicating that SIRT3 positively regulates mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and maintenance of mitochondrial integrity. Mitophagy is critical to maintain proper cellular functions. In Cr(VI)-transformed cells expressions of Pink 1 and Parkin, two mitophagy proteins, were elevated, and mitophagy remained similar as that in passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells, indicating that in -Cr(VI)-transformed cells mitophagy is suppressed. Knockdown of SIRT3 induced mitophagy, suggesting that SIRT3 plays an important role in mitophagy suppression of Cr(VI)-transformed cells. In Cr(VI)-transformed cells, nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) was constitutively activated, and protein levels of p62 and p-p62Ser349 were elevated. Knockdown of SIRT3 or treatment with carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) decreased the binding of p-p62Ser349 to Keap1, resulting in increased binding of Keap1 to Nrf2 and consequently reduced Nrf2 activation. The results from CHIP assay showed that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells binding of Nrf2 to antioxidant response element (ARE) of SIRT3 gene promoter was dramatically increased. Knockdown of SIRT3 suppressed cell proliferation and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Overexpression of SIRT3 in normal BEAS-2B cells exhibited mitophagy suppression phenotype and increased cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. The present study demonstrated that upregulation of SIRT3 causes mitophagy suppression and plays an important role in cell survival and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells.

Keywords: chromium(VI), carcinogenesis, oxidative stress, mitophagy, SIRT3

Hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] has been classified as a Group 1 human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research in Cancer (IARC). Environmental exposure to Cr(VI) has increased in the past decades due to usage of this metal in industry, agriculture, and technology endeavors (He et al., 2005; Shallari et al., 1998; Tchounwou et al., 2012). Our previous study has shown that chronic exposure of human bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B) cells to Cr(VI) caused malignant cell transformation (Kim et al., 2015). These transformed cells exhibited reduced capacity of generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), development of apoptosis resistance, and increase in angiogenesis, leading to cell survival and tumorigenesis (Kim et al., 2015, 2016; Pratheeshkumar et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2011).

Mitochondria regulate energy homeostasis and cell death. Mitophagy, a selective form of autophagy for elimination of damaged mitochondria, is essential to reduce insufficient supply of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and excessive production of ROS. Defective mitophagy has been demonstrated to contribute to various diseases, including cancer (Bernardini et al., 2017; Chourasia et al., 2015; Kulikov et al., 2017). Mitophagy is regulated by two key mediators, the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin (encoded by Park2 gene) and the Pten-induced putative kinase 1 (Pink1; Durcan and Fon 2015; Eiyama and Okamoto 2015; Wei et al., 2015). Depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) causes translocation of Pink1 to the outer membrane, where it phosphorylates Parkin. Phosphorylated Parkin then ubiquitinates outer mithochondrial membrane proteins, targeting the organelle to undergo lysosomal autophagical degradation (Wei et al., 2015).

NAD-dependent sirtuin 3 (SIRT3), a major mitochondrial deacetylation enzyme, regulates metabolic homeostasis via mitochondria protein deacetylation (Finley and Haigis 2012; Giralt and Villarroya 2012). It was reported that SIRT3-deficient mice are below basal metabolic condition concomitant with increased mitochondrial hyper-acetylation (Lombard et al., 2007). SIRT3 was found to be associated with antioxidant response (Bell and Guarente 2011; Park et al., 2011), regulation of oxidative metabolism, glycolytic pathway (Finley and Haigis 2012), and suppression of mitophagy (Liang et al., 2013; Pi et al., 2015).

In cancer cells energy production relies on glycolysis, instead of mitochondria oxidative phosphorylation. It has been reported that mitochondrial function is essential to produce key biosynthetic intermediates instead of ATP, directly contributing to cancer cell survival and tumorigenesis (Finley and Haigis 2012). The present study investigated the roles of SIRT3 in suppressing mitophagy, cell survival and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Sodium dichromate dehydrate (Na2Cr2O7) was obtained from Sigma (St Louis, Missouri). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and pen-strep-glutamine solution were obtained from Gibco (Grand Island, NY). The shRNAs and overexpressing vectors of SIRT3 and Nrf2 and primers for real-time PCR were obtained from Origene (Rockville, Maryland). mKeima-Red-Mito-7 plasmid and PCD FL0X luciferase reporter were from Addgene. The RNAeasy mini kit and plasmid prep kit were obtained from Qiagen (Valencia, California). M-MLV reverse transcriptase and luciferase assay reagents were obtained from Promega (Madison, Wisconsin). AccuPrime TaqDNA polymerase high fidelity, antibodies against Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG1 and Alexa Fluor 649 goat anti-rabbit IgG1, Lipofectamine 2000, and 10-N-Acridine Orange (NAO) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, California). The iQ SyBr green supermix was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, California). Antibodies against SIRT3, p62, p-p62 (ser349), Parkin, Pink1, and cytochrome c were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, Massachusetts). Antibodies against Nrf2, GAPDH, and Keap-1 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas). Mitochondrial isolation kit and Pierce agarose chip kit were obtained from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts). The JC-1 MMP assay kit was obtained from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, Michigan). Matrigel was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, California). Chemiluminescence reagent was obtained from Amershan Biosciences (Little Chalfont, UK).

Cell culture and generation of Cr(VI)-transformed cells

Human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Maryland). Malignantly transformed cells induced by chronic exposure to Cr(VI) were generated as previously described (Kim et al., 2015). Passage-matched normal BEAS-2B and Cr(VI)-transformed cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% pen-strep-glutamine solution at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Detection of mitochondria ATP production and proton leak

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates for overnight. Mitochondrial ATP production and proton leak were detected using Seahorse FX mitochondria stress test.

Immunoblotting assay

Cells were harvested, and pellets were lysed in RIPA buffer. Protein concentration was measured using Bradford assay. Thirty micrograms of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies. Chemiluminescence reagent was used to detect protein levels.

Plasmid transfection and establishment of stable knockdown or expressing cells

Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 as described by the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, 1.5 × 106 cells were seeded and grown for overnight. The cells were transfected with 4 µg of plasmid, and selected using DMEM medium containing 2 µg/ml of puromycin for 2 months. Expressions of those proteins were detected using immunoblotting analysis.

Real-time PCR

The RNeasy mini kit was used to extract and to purify RNA from cultured cells. 0.5 µg of purified RNA was reversed transcribed using qScript cDNA synthesis kit. Following primers were used: SIRT3, 5′-ACCCAGTGGCATTCCAGAC-3′ and 5′-GGCTTGGGGTTGTGAAAGAA-3′; NQO1, 5′-TGGAAGTCGTC CCAAGAGA-3′ and 5′-TGTCTCCCCAGGACTCTCTCAG-3′; and GAPDH, 5′-GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT-3′ and 5′-GACAAGCTT CCCGTTCTCAG-3′. The qPCR was performed using Sybr Green mixture in CFX96 Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) and data were analyzed using CFX manager software (Bio-Rad).

Mitochondrial isolation

Passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells and Cr(VI)-transformed cells were grown in cell culture medium. Mitochondrial and cytosolic isolation were performed using the mitochondrial isolation kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. Mitochondria lysis was performed using 2% CHAPS in tris-buffered saline. Thirty micrograms of protein from cytosolic and mitochondrial fraction were used for immunoblotting analysis.

Detection of mitochondria membrane potential

Mitochondria membrane potential was detected using JC-1 MMP assay kit as described by the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, 104 cells were seeded for overnight in a CO2 incubator. The cells were treated with 5 µM of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) for 4 h. J-aggregates fluorescent intensity was measured using Gemini XPS fluorescence microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices).

Mitochondria mass analysis

The NAO is a fluorescent probe that stains mitochondria independently of its energetic state (Ferlini and Scambia 2007; Lee et al., 2000; Maftah et al., 1989). Cells were seeded for overnight, and treated with 5 µM of CCCP for 4 h followed by incubation with 5 µM of NAO for 10 min. The NAO fluorescence intensity was measured using Gemini XPS fluorescence microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices).

Mito-Keima mitophagy assay

Mito-keima-Red-Mito-7 plasmid was stably transfected to the cells as described in previous section. Cells were seeded for overnight. Lysosomal mKeima fluorescence intensity was measured as described previously (Lazarou et al., 2015), using Gemini XPS fluorescence microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices).

Immunoprecipitation analysis

Cell lysates were incubated with precleaned beads and centrifuged. Supernatants were collected and incubated with 5 µg of primary antibody for overnight. After incubation with precleaned beads, the samples were washed with PBS and centrifuged followed by adding Laemmli sample buffer. The samples were centrifuged and supernatant was collected for immunoblotting analysis.

Fluorescence immunocytochemistry analysis

Cells were seeded on the chamber slides for overnight, washed with PBS, and fixed with 4% formaldehyde followed by incubation with 1% Triton-X100. The cells were then incubated with 10% horse serum. Primary antibodies were added and incubated for overnight followed by incubation with secondary antibodies. The slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium and visualized using Olympus BX53 fluorescence microscope (Center Valley, Pennsylvania). Relative colocalization was measured using CellSens Dimension software (Olympus Corporation).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed using Pierce™ agarose chip kit. The DNA and protein were cross-linked using 1% formaldehyde. The cells were lysed and nuclei were digested with micrococcal nuclease. Chromatin was diluted and immunoprecipitated with 2 µg of Nrf2 antibody or IgG antibody. The DNA-protein complexes were eluted from the protein A/G-agarose beads. Binding of Nrf2 to antioxidant response element (ARE) of SIRT3 promoter was analyzed by real-time PCR. Amplified DNA was separated on 2% agarose gel with Gel Red® followed by band visualization under ultraviolet transillumination.

Luciferase assay

Cells were transfected with 4 μg of SIRT3 luciferase reporter for 48 h. Luciferase activities were measured using Glomax luminometer (Promega). Data were normalized to total cell count.

Tumorigenesis assay

Female athymic nude mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) and housed in sterilized filter-topped cages in a pathogen free animal facility at the Chandler Medical Center, University of Kentucky. Animals were handled according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines. Cells in 100 µL mixture of DMEM and Matrigel (BD Biosciences) were subcutaneously injected on the flank of each mouse. After 3 weeks, mice were euthanized using CO2 and the tumors were isolated. Tumor weight was measured and volume was calculated using the formula: (length × width2)/2.

RESULTS

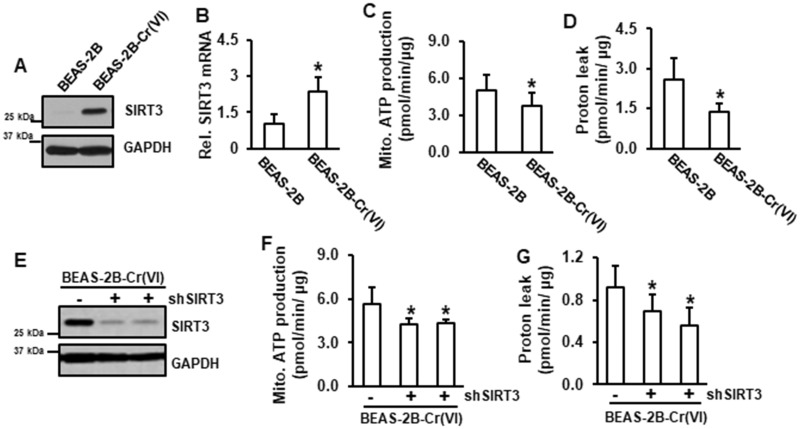

SIRT3 Positively Regulates Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation Pathway in Cr(VI)-Transformed Cells

In Cr(VI)-transformed cells both protein and mRNA levels of SIRT3 were elevated (Figures 1A and 1B). Our recent study using RNA sequencing analysis demonstrated that all five mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes were reduced in Cr(VI)-transformed cells compared to those in passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells (Clementino et al., 2018). Consistently, the results from mitochondrial stress test showed that mitochondrial ATP production and proton leak were reduced in Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figures 1C and 1D). These results suggest that mitochondrial ATP production is inhibited and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation pathway is defective in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. To investigate whether SIRT3 is involved in reduced mitochondrial ATP production in Cr(VI)-transformed cells, SIRT3 was inhibited using its shRNA (Figure 1E). The results showed that knockdown of SIRT3 further decreased both mitochondrial ATP production and proton leak in Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figures 1F and 1G), indicating that SIRT3 positively regulates mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation pathway in Cr(VI)-transformed cells.

Figure 1.

SIRT3 is a positive regulator of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation pathway in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. A, Whole protein lysates from Cr(VI)-transformed cells and passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells were used for immunoblotting analysis. B, RNA was isolated from Cr(VI)-transformed cells and passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells and subjected to RT-PCR analysis. C and D, Passage-matched normal BEAS-2B and Cr(VI)-transformed cells were seeded in 96-well plates for overnight. Mitochondrial stress test was conducted using Seahorse analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8). *p < .05 compared with those in passage-matched BEAS-2B cells. E, Cr(VI)-transformed cells were transfected with or without shSIRT3. Whole protein lysates were subjected to immunoblotting analysis. F and G, Cr(VI)-transformed cells transfected with or without shSIRT3 were seeded in 96-well plates for overnight followed by Seahorse analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8 or 16). *p < .05 compared with Cr(VI)-transformed cells without SIRT3 knockdown.

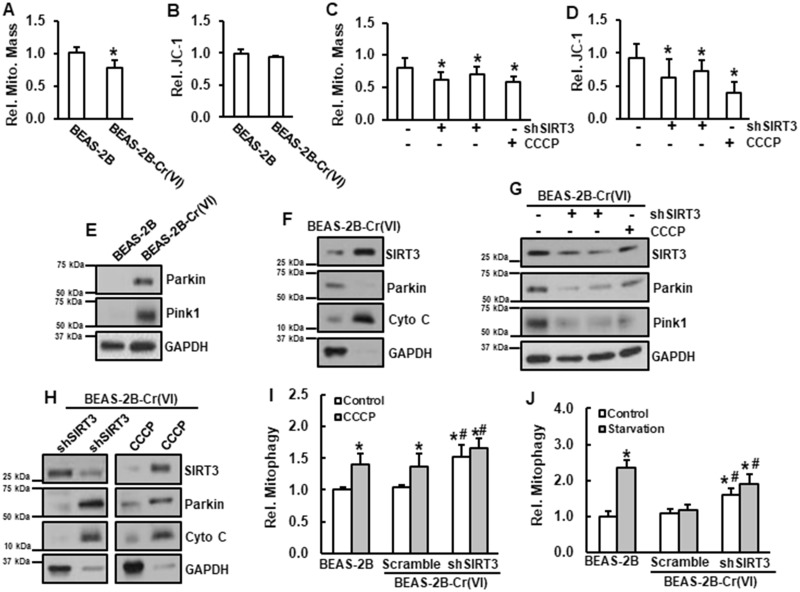

SIRT3 Is a Negative Regulator of Mitophagy in Cr(VI)-Transformed Cells

Mitochondria mass was reduced in Cr(VI)-transformed cells compared to that in passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells (Figure 2A). There was no observable difference in MMP between passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells and Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figure 2B), leading to hypothesize that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells mitophagy is suppressed and that upregulation of SIRT3 is responsible for the mitophagy suppression. Our results showed that knockdown of SIRT3 by its shRNA decreased MMP (Figure 2D) and mitochondrial mass (Figure 2C). Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), a mitochondrial depolarizing agent known to induce mitophagy (Ni et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2015), was used as a positive control. These results suggest that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells, upregulation of SIRT3 prevents mitochondria membrane potential from reduction.

Figure 2.

SIRT3 is a negative regulator of mitophagy in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. A and B, Passage-matched normal BEAS-2B and Cr(VI)-transformed cells were seeded in 96-well plate for overnight. A, Mitochondrial mass was measured and B, JC-1 fluorescence intensity was measured. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8). *p < .05 compared with that in BEAS-2B cells. C and D, Cr(VI)-transformed cells transfected with or without shSIRT3, or treatment with 5 µM of CCCP for 4 h were seeded in 96-well plate for overnight. C, Mitochondrial mass was measured and D, JC-1 fluorescence intensity was measured. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8). *p < .05 compared with that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells without treatment. E, Whole protein lysates from Cr(VI)-transformed cells and passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells were subjected to immunoblotting analysis. F, Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions from Cr(VI)-transformed cells were isolated and subjected to immunoblotting analysis. G, Whole protein lysates from Cr(VI)-transformed cells transfected with or without shSIRT3, or treated with 5 µM of CCCP for 4 h were subjected to immunoblotting analysis. H, Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions from Cr(VI)-transformed cells transfected with or without shSIRT3, or treated with 5 µM of CCCP for 4 h were subjected to immunoblotting analysis. I, BEAS-2B cells or Cr(VI)-transformed cells transfected with or without shSIRT3, or treated with 5 µM of CCCP for 4 h were seeded in 96-well plate for overnight. mKeima fluorescence intensity was measured. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8). * and #, p < .05 compared with that in BEAS-2B cells without treatment or Cr(VI)-transformed cells without treatment, respectively. J, BEAS-2B cells and Cr(VI)-transformed cells transfected with or without shSIRT3 were seeded in 96-well plate for overnight. Cells were starved for 24 h. mKeima fluorescence intensity was measured. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8). * and #, p < .05 compared with Controls in BEAS-2B cells and Cr(VI)-transformed cells, respectively.

In Cr(VI)-transformed cells, both Pink1 and Parkin were upregulated (Figure 2E). SIRT3 was mainly localized in the mitochondria and Parkin was in the cytosol (Figure 2F), which ascertains that mitophagy was suppressed in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Additionally, we observed that knockdown of SIRT3 by its shRNA reduced protein levels of Parkin and Pink1 (Figure 2G) and translocated Parkin to the mitochondria (Figure 2H). The results from Mito-keima analysis showed no difference in mitophagy between Cr(VI)-transformed cells and their passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells, whereas knockdown of SIRT3 induced mitophagy in Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figure 2I). Without surprising, treatment with CCCP induced mitophagy in both normal BEAS-2B and Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figure 2I). Next, mitophagy was measured under starvation condition. The results showed that under starvation mitophagy was induced in passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells, but not in Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figure 2J). These results indicate that SIRT3 suppresses mitophagy in Cr(VI)-transformed cells via stabilization of MMP.

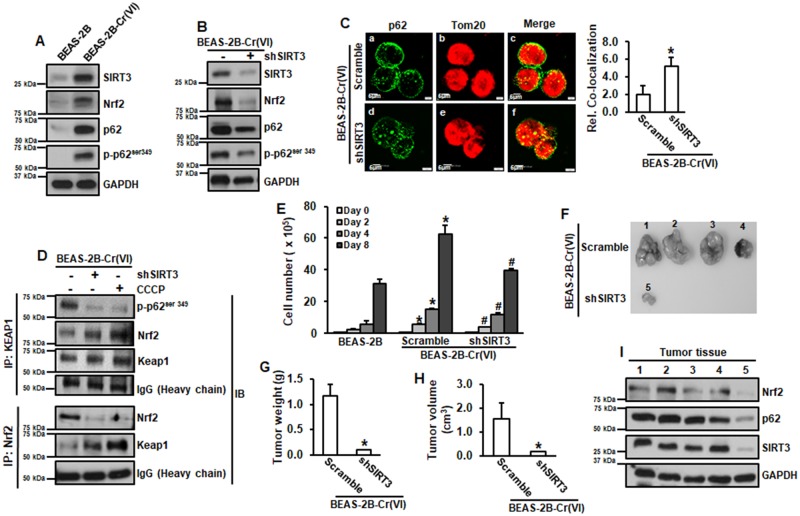

Upregulation of SIRT3 Elevates p62 and Nrf2, Leading to Increased Cell Proliferation and Tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-Transformed Cells

Levels of Nrf2, p62 and p-p62ser349 were all increased in Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figure 3A). Knockdown of SIRT3 by its shRNA decreased levels of Nrf2, p62, and p-p62ser349 (Figure 3B) and caused more p62 translocated to mitochondria (Figure 3C). The results from Figure 2I showed that knockdown of SIRT3 increased mitophagy in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. These results suggest that upregulation of SIRT3 prevents p62 from mitophagic degradation through stabilization of MMP.

Figure 3.

Upregulation of SIRT3 elevates p62 and Nrf2, leading to increased cell proliferation and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells. A and B, Whole protein lysates from passage-matched normal BEAS-2B and Cr(VI)-transformed cells transfected with or without shSIRT3 were subjected to immunoblotting analysis. C, Cr(VI)-transformed cells transfected with or without shSIRT3 were subjected to fluorescence immunohistochemistry analysis. Relative colocalization was measured. Images were represented 1 sample in each treatment group (Left). Fluorescence intensities were quantitated (Right). Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < .05 compared with that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Scramble). D, Whole protein lysates from Cr(VI)-transformed cells transfected with or without shSIRT3, or treated with 5 µM of CCCP for 4 h were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation analysis. E, Passage-matched normal BEAS-2B and Cr(VI)-transformed cells with or without shSIRT3 were seeded in 6-well plates for 2, 4, and 8 days and total cell number was counted. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). * and #, p < .05 compared with that in BEAS-2B cells or Cr(VI)-transformed cells, respectively at the same day. F–H, 6–8 weeks old female immuno-deficient mice were subcutaneously injected with Cr(VI)-transformed cells with or without shSIRT3. After 3 weeks, tumor volumes were measured (H). Tumor tissues were isolated. Tumors were pictured (F) and weighted (G). Protein lysates were extracted from tumor tissues for immunoblotting analysis (I). G and H, Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4). *p < .05 compared with that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells.

Keap1 binds and ubiquitinates Nrf2, targeting to proteasomal degradation of Nrf2 (Suzuki et al., 2016). Keap1 has higher affinity to bind to p-p62ser349 than Nrf2 (Ichimura et al., 2013; Katsuragi et al., 2016b). Knockdown of SIRT3 or treatment with CCCP reduced binding between Keap1 and p-p62ser349 and increased binding between Keap1 and Nrf2, resulting in decreased level of Nrf2 in Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figure 3D), demonstrating that SIRT3 regulates Nrf2 through increased binding of p62 to Keap1.

We investigated whether upregulation of SIRT3 is essential for increased cell proliferation and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells. The results showed that knockdown of SIRT3 reduced cell proliferation of Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figure 3E). The results from in vivo xenograft tumor growth assay showed that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells 4 out 4 animals (100%) grew tumors and in SIRT3 knockdown cells 1 out of 4 animals (25%) grew tumor (Figure 3F). Moreover, tumors isolated from Cr(VI)-transformed cells were bigger (Figure 3H) and heavier (Figure 3G) than those isolated from SIRT3 knockdown cells. The results from immunoblotting analysis showed the protein levels of Nrf2, p62, and SIRT3 were all markedly reduced in the tumor tissues from SIRT3 knockdown cells compared with those from Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figure 3I). These results demonstrated that SIRT3 plays an important role in the cell proliferation and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells.

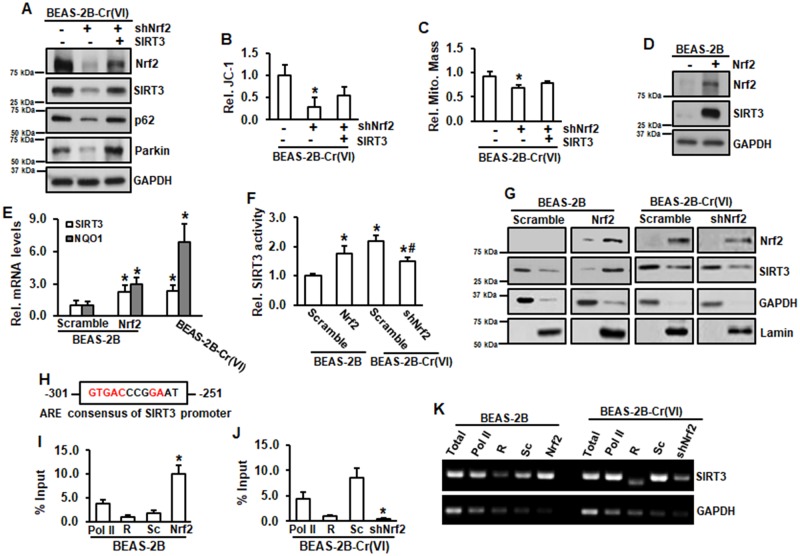

Nrf2 Regulates SIRT3 through Direct Binding to the ARE of SIRT3 Gene Promoter

Knockdown of Nrf2 by its shRNA decreased levels of SIRT3, p62, and Parkin in Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figure 4A). Overexpression of SIRT3 restored these reductions by Nrf2 knockdown, indicating that Nrf2 is an upstream regulator of SIRT3. Knockdown of Nrf2 also reduced MMP (Figure 4B) and mitochondrial mass (Figure 4C). Overexpression of SIRT3 was able to partially restore MMP and mitochondrial mass reduced by Nrf2 knockdown (Figures 4B and 4C). Stably expressing Nrf2 in normal BEAS-2B cells was established and the results showed that SIRT3 level was elevated in Nrf2-expressing BEAS-2B cells (Figure 4D), suggesting that regulation of Nrf2 on SIRT3 is not specific for Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Next, we explored the mechanism of regulation of Nrf2 on SIRT3. Both SIRT3 mRNA level and promoter activities were elevated in Nrf2-expressing normal BEAS-2B cells and Cr(VI)-transformed cells compared with those in normal BEAS-2B cells (Figures 4E and 4F). Overexpression of Nrf2 in normal BEAS-2B cells increased SIRT3 in nucleus (Figure 4G). We analyzed human promoter sequence of SIRT3 gene using the transcriptional regulatory element database and identified the antioxidant response element (ARE) of SIRT3 gene promoter (Figure 4H). Next, we conducted DNA CHIP assay. The results showed that in normal BEAS-2B cells, overexpression of Nrf2 markedly increased the binding of Nrf2 to ARE of SIRT3 promoter (Figures 4I and 4K). In Cr(VI)-transformed cells, knockdown of Nrf2 by its shRNA reduced the binding of Nrf2 to ARE of SIRT3 gene promoter (Figures 4J and 4K), demonstrating that Nrf2 regulates SIRT3 through direct binding to the ARE of SIRT3 promoter.

Figure 4.

Nrf2 positively regulates SIRT3. A–C, Cr(VI)-transformed cells transfected with or without shNrf2, or in combination with SIRT3 expression were submitted for immunoblotting analysis (A), JC-1 analysis (B), and mitochondria mass measurement (C). B and C, Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8). *p < .05 compared with those in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. D, Whole lysates from BEAS-2B with or without stable Nrf2 expression were subjected to immunoblotting analysis. E, RNA was isolated from BEAS-2B with or without stable Nrf2 expression or Cr(VI)-transformed cells. mRNA level was measured using RT-PCR analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < .05 compared with that in BEAS-2B cells (Scramble). F, BEAS-2B with or without stable Nrf2 expression and Cr(VI)-transformed cells with or without shNrf2 were transfected with SIRT3 luciferase reporter. After 48 h of transfection, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates for overnight, followed by luciferase measurement. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8). * and #, p < .05 compared with that in BEAS-2B cells and Cr(VI)-transformed cells, respectively. G, Nuclear and cytosolic fractions from BEAS-2B with or without stable Nrf2 expression and Cr(VI)-transformed cells with or without shNrf2 were isolated and subjected to immunoblotting analysis. H, Consensus of ARE of human SIRT3 gene promoter. I–K, BEAS-2B with or without stable Nrf2 expression and Cr(VI)-transformed cells with or without shNrf2 were submitted to ChIP with anti-Nrf2 antibody or control Rabbit IgG (R). Binding of Nrf2 to SIRT3 promoters was analyzed by PCR using specific primers. GAPDH was used as a control. I and J, ChIP and quantitative RT-PCR. The amounts of immunoprecipitated DNA were normalized to the inputs and plotted. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < .05 compared with Scramble cells (Sc). K, Amplified DNA was separated on agarose gel followed by band visualization under ultraviolet transillumination. ARE, antioxidant response element; ChIP, Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

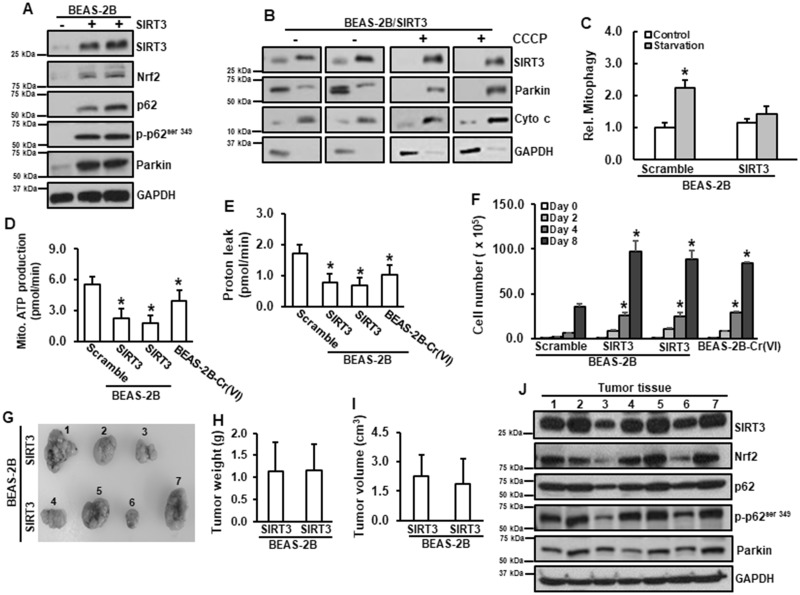

Constitutive Activation of SIRT3 Is Tumorigenic

The above results lead us to speculate that constitutive activation of SIRT3 is tumorigenic. Stably expressing SIRT3 in normal BEAS-2B cells was established. Two clones from these cells were picked up and continued to grow. Overexpression of SIRT3 in normal BEAS-2B cells increased protein levels of Nrf2, p62, p-p62ser349, and Parkin (Figure 5A). SIRT3 was mainly located in mitochondria and Parkin was in the cytosol (Figure 5B). As expected, overexpression of SIRT3 suppressed mitophagy under starvation (Figure 5C). Similar to those in Cr(VI)-transformed cells, overexpression of SIRT3 in normal BEAS-2B cells reduced both mitochondrial ATP production and proton leak (Figures 5D and 5E). Moreover, overexpression of SIRT3 in normal BEAS-2B cells promoted cell growth, similar as that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells (Figure 5F). The results from in vivo tumor growth showed that the animals injected with normal BEAS-2B cells with SIRT3 expression grew tumors (3 out of 4 animals in one clone of SIRT3 cells and 4 out 4 animals in another clone of SIRT3 cells; Figures. 5G–I). The results from immunoblotting analysis showed that these tumor tissues have high levels of Nrf2, p62, p-p62ser349, and Parkin (Figure 5J), which are similar as those in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. The above observations demonstrated that constitutive activation of SIRT3 is tumorigenic.

Figure 5.

Constitutive activation of SIRT3 is tumorigenic. A, Normal BEAS-2B was transfected with SIRT3 expression vector. Whole lysates were harvested for immunoblotting analysis. B, BEAS-2B with or without stable expression of SIRT3 were treated with 5 µM of CCCP for 4 h. Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were isolated for immunoblotting analysis. (C) BEAS-2B with or without stable expression of SIRT3 were seeded in 96-well plate for overnight. Cells were starved for 24 h. mKeima fluorescence intensity was measured. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8). *p < .05 compared with control. D and E, BEAS-2B cells with or without stable expression of SIRT3 and Cr(VI)-transformed cells were seeded in 96-well plates for overnight. Mitochondrial stress test was conducted using Seahorse analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8). *p < .05 compared with those in BEAS-2B cells. F, BEAS-2B cells with or without stable expression of SIRT3 and Cr(VI)-transformed cells were seeded in 6-well plates for 2, 4, and 8 days and total cell number was counted. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < .05 compared with that in BEAS-2B cells (Scramble) at the same day. G–I, 6–8 weeks old female immuno-deficient mice were subcutaneously injected with BEAS-2B with or without SIRT3 stable expression. After 3 weeks, tumor volumes were measured (I). Tumor tissues were isolated. Tumors were pictured (G) and weighted (H). Protein lysates were extracted from tumor tissues for immunoblotting analysis (J).

DISCUSSION

Mitochondrial quality control is required for the maintenance of a functioning mitochondrial network and cellular metabolism, and for the prevention of accumulation of ROS. Given the pivotal role of mitochondria in cellular homeostasis, defective mitophagy is known to contribute to various diseases. Our previous study has demonstrated that Cr(VI)-transformed cells undergo metabolic reprogramming (Clementino et al., 2018). Cancer cells shift ATP synthesis from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis to produce key biosynthetic intermediates in the mitochondria instead of ATP (Finley and Haigis 2012). Therefore, mitochondrial function is essential for cancer cell proliferation and survival. SIRT3 regulates metabolic homeostasis via deacetylation of mitochondrial proteins (Finley and Haigis 2012; Giralt and Villarroya 2012). In human cancer cells, mutant SIRT3 reduces MMP and mitochondrial ATP generation (Liu et al., 2015). SIRT3 regulates oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) at different levels. SIRT3 regulates activities of complexes I and III via deacetylation of these complexes’ subunits (Ahn et al., 2008; Cimen et al., 2010). Once complexes I and III are deacetylated, they produce less ROS (Ahn et al., 2008; Cimen et al., 2010; Finley and Haigis 2012). SIRT3 also regulates enzymes involved in The Citric Acid (TCA) cycle. It has been reported that SIRT3 deacetylates succinate dehydrogenase (SDH; Finley et al., 2011) and isocytrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2; Someya et al., 2010). Succinate dehydrogenase participates in both the TCA cycle and electron transport chain, therefore it is well situated to coordinate flux through both pathways (Finley et al., 2011). Isocytrate dehydrogenase 2 provides reducing equivalents to combat oxidative stress or to promote anabolic reactions by reducing NADP to NADPH (Someya et al., 2010). Deacetylation of SDH and IDH2 by SIRT3 could potentially stimulate mitochondria oxidative capacity and protect cells against oxidative stress. Thus, SIRT3 is expected to play decisive role in cell survival and cell response to stress. Tumors harboring mutant SIRT3 exhibit inhibited tumor growth and increased sensitivity to local radiation in vivo (Liu et al., 2015). The present study has observed that SIRT3 is constitutively activated in Cr(VI)-transformed cells; that the constitutively activated SIRT3 is essential to maintain mitochondrial function; that the activation of SIRT3 contributes to cell survival and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells; and that the constitutive activation of SIRT3 is tumorigenic.

Mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondria mass are two indicators of mitochondrial integrity. Damaged mitochondria accumulate Pink1, which in turn recruits Parkin, resulting in ubiquitination of mitochondrial proteins (Ivankovic et al., 2016). Previous studies have shown that upregulation of SIRT3 stabilized MMP and maintained mitochondrial mass (Pellegrini et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). Our results showed that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells SIRT3 was constitutively activated, MMP remained unchanged, and mitochondrial mass was reduced compared with those in passage-matched normal BEAS-2B cells. Knockdown of SIRT3 by its shRNA decreased MMP and further reduced mitochondria mass. Thus we speculated that constitutive activation of SIRT3 is essential to maintain MMP and mitochondrial function in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Under normal condition, mitophagy remained similar between normal BEAS-2B cells and Cr(VI)-transformed cells. However, starvation was able to induce mitophagy in normal BEAS-2B cells, but not in Cr(VI)-transformed cells, indicating that mitophagy is suppressed in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Mitochondria membrane depolarization is the first step to induce mitophagy. Once MMP is reduced, Pink1 recruits Parkin to the mitochondria. Under the conditions which mitochondria are undamaged, Pink1 is imported into the mitochondrial inner membrane, where Pink1 is cleaved. Aberration in MMP impairs import of Pink1 to the mitochondrial inner membrane, leading to the stabilization of Pink1 on the mitochondrial outer membrane (Bernardini et al., 2017). Parkin is responsible to target this organelle to autophagosomal destruction (Durcan and Fon 2015; Eiyama and Okamoto 2015; Lazarou et al., 2015; Ni et al., 2015). We have observed that both Pink1 and Parkin levels were elevated in Cr(VI)-transformed cells and Parkin was mainly located in the cytoplasm, providing the explanations of mitophagy suppression in Cr(VI)-transformed cells.

It has been reported that SIRT3 regulates mitophagy machinery proteins Parkin and Pink1 (Das et al., 2014; Liang et al., 2013; Pi et al., 2015; Qiao et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016). We speculated that constitutively activated SIRT3 contributes to the suppressed mitophagy in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. The results showed that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells knockdown of SIRT3 increased mitochondria membrane depolarization, translocated Parkin from cytosol to the mitochondria, and induced mitophagy. Thus we conclude that constitutively activated SIRT3 contributes to mitophagy suppression of Cr(VI)-transformed cells.

It has been reported that recruitment of autophagic adaptor p62/SQSTM1 to the mitochondrial clusters is essential for the clearance of mitochondria (Geisler et al., 2010). p62 interacts with the autophagosome membrane to target the mitochondria to undergo autophagosomal destruction (Chourasia et al., 2015; Ding and Yin 2012; Kulikov et al., 2017; Ni et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2015). We observed that p62 was upregulated in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. p62 was mainly located in the surrounding area of mitochondria, thus blocking the degradation of damaged mitochondria in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Knockdown of SIRT3 caused translocation of p62 to the mitochondria, promoting mitochondrial degradation through mitophagy induction.

Nrf2 is a key transcription factor that regulates antioxidant proteins to neutralize ROS and to restore cellular redox balance (Lee et al., 2012; Niture et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2015a). ROS play a major role in metal-induced carcinogenesis (Kim et al., 2015, 2016; Lee and Yu 2016; Lee et al., 2012; Pratheeshkumar et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2015b). Inducible Nrf2 decreases carcinogenesis in the early stage via decrease of oxidative stress (Sporn and Liby 2012), constitutively activated Nrf2 exerts oncogenic effects by protecting cancer cells from oxidative stress and chemotherapeutics (Kansanen et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2008). Recent studies have highlighted its role in mitochondrial function, including regulation of mitophagy via interaction with p62 and Keap1 (Dinkova-Kostova and Abramov 2015; Holmström et al., 2016). Our results showed that Nrf2 is constitutive activated in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Knockdown of Nrf2 reduced SIRT3 protein level, mitochondria mass, and MMP. Overexpression of SIRT3 partially restored reductions of both mitochondria mass and MMP by Nrf2 knockdown. These results demonstrate that SIRT3 is downstream target of Nrf2 signaling in regulation of mitophagy in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Previous study showed that Nrf2 induced SIRT3 expression in 293 T cells (Satterstrom et al., 2015). The present study has demonstrated that Nrf2 positively regulates SIRT3 in Cr(VI)-transformed cells via directly binding to the ARE of SIRT3 gene promoter. Cr(VI) induces ROS generation, activating a cellular response to prevent the generation of ROS or detoxify ROS. The activation of Nrf2 pathway is considered to be the most important for cell survival during oxidative stress (Niture et al., 2010). Nrf2 activates the expression of several antioxidant enzymes by directly biding to the ARE of their gene promoters (Niture et al., 2010). Our results showed that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells activation of Nrf2 causes upregulation of SIRT3, promoting cancer cell survival and tumorigenesis. It has been reported that Nrf2 regulates p62 via its direct binding to the ARE of p62 gene promoter (Katsuragi et al., 2016a). p62 feedbacks to Nrf2 via competitive binding of Keap1 to Nrf2 (Jain et al., 2010). In the agreement of these findings, the present study has demonstrated that upregulation of p-p62Ser349 in Cr(VI)-transformed cells competitively binds to Keap1, resulting in reduced binding of Keap1 to Nrf2 and subsequently elevated Nrf2. Knockdown of SIRT3 decreased p-p62Ser349, leading to increased binding of Keap1 to Nrf2, subsequently decreased Nrf2. Human adenocarcinomic epithelial A549 cells were also used to examine the effects of SIRT3 on Nrf2/p62, Pink1/Parkin, and mitochondrial functions. The similar results as those in Cr(VI)-transformed cells were obtained (Supplementary Figure 1). In summary, our results suggest that in Cr(VI)-transformed cells (1) Nrf2 positively regulates SIRT3 via its direct binding to ARE of SIRT3 promoter; (2) p62Ser349 binds to Keap1, resulting in upregulation of Nrf2; and (3) SIRT3 feedbacks to Nrf2 via interacting with Keap1-Nrf2/p62 pathway.

In Cr(VI)-transformed cells SIRT3 is upregulated. Inhibition of SIRT3 reduced cell proliferation and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells, suggesting that SIRT3 maybe tumorigenic. Previous studies reported that SIRT3 had oncogenic properties (Chen et al., 2014; Giralt and Villarroya 2012; Morris et al., 2011; Pillai et al., 2010). Our results showed that overexpression of SIRT3 in normal BEAS-2B cells increased levels of Nrf2, p62, p-p62Ser349, and Parkin. Our result also showed that overexpression of SIRT3 reduced mitochondrial ATP production and proton leak and suppressed mitophagy, which are similar as those in Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Importantly, overexpression of SIRT3 in normal BEAS-2B cells increased cell proliferation in vitro and caused tumor growth in vivo.

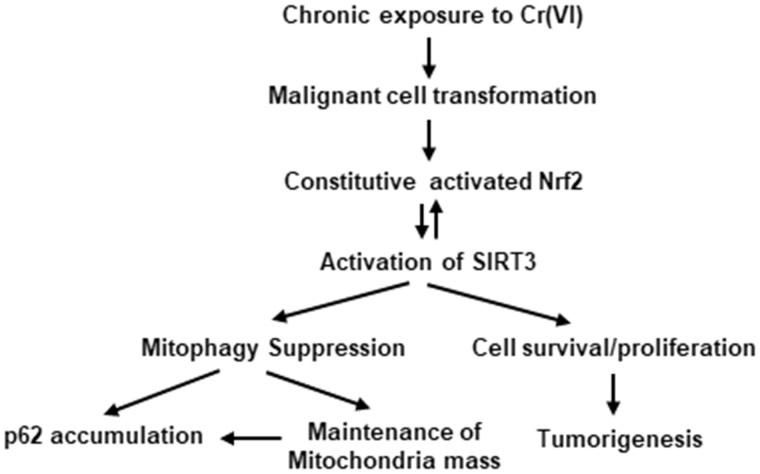

In summary, the present study demonstrated that SIRT3 is important to maintain mitochondrial basal oxidative phosphorylation of Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Cr(VI)-transformed cells are mitophagy suppressed. Knockdown of SIRT3 induces mitophagy and decreases proliferation and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Constitutively activated Nrf2 upregulates SIRT3 via its direct binding to ARE of SIRT3 promoter. SIRT3 feedbacks to Nrf2 via interacting Keap1-Nrf2 axis. High level of SIRT3 in normal cells induces tumor growth in xenograft animal model, indicating that SIRT3 is tumorigenic. The mechanism of SIRT3 in mitophagy and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells is summarized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The scheme of mechanism of SIRT3 in mitophagy and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Chronic exposure of the cells to Cr(VI) at low dose causes malignant cell transformation. The malignantly transformed cells exhibit constitutive activated Nrf2 and SIRT3, leading to mitophagy suppression, cell survival and tumorigenesis of Cr(VI)-transformed cells.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH/NIEHS/R01ES021771, P30 ES026529, and the Redox Metabolism Shared Resource of the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center (P30CA177558).

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Ahn B. H., Kim H. S., Song S., Lee I. H., Liu J., Vassilopoulos A., Deng C. X., Finkel T. (2008). A role for the mitochondrial deacetylase sirt3 in regulating energy homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14447–14452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E. L., Guarente L. (2011). The sirt3 divining rod points to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell 42, 561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini J. P., Lazarou M., Dewson G. (2017). Parkin and mitophagy in cancer. Oncogene 36, 1315–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Fu L. L., Wen X., Wang X. Y., Liu J., Cheng Y., Huang J. (2014). Sirtuin-3 (sirt3), a therapeutic target with oncogenic and tumor-suppressive function in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1047.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chourasia A. H., Boland M. L., Macleod K. F. (2015). Mitophagy and cancer. Cancer Metab. 3, 4.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimen H., Han M. J., Yang Y., Tong Q., Koc H., Koc E. C. (2010). Regulation of succinate dehydrogenase activity by sirt3 in mammalian mitochondria. Biochemistry 49, 304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementino M., Shi X., Zhang Z. (2018). Oxidative stress and metabolic reprogramming in Cr(vi) carcinogenesis. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 8, 20–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S., Mitrovsky G., Vasanthi H. R., Das D. K. (2014). Antiaging properties of a grape-derived antioxidant are regulated by mitochondrial balance of fusion and fission leading to mitophagy triggered by a signaling network of sirt1-sirt3-foxo3-pink1-parkin. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2014, 345105.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Ding W. X., Yin X. M. (2012). Mitophagy: Mechanisms, pathophysiological roles, and analysis. Biol. Chem. 393, 547–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova A. T., Abramov A. Y. (2015). The emerging role of nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88, 179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durcan T. M., Fon E. A. (2015). The three ‘p’s of mitophagy: Parkin, pink1, and post-translational modifications. Genes Dev. 29, 989–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiyama A., Okamoto K. (2015). Pink1/parkin-mediated mitophagy in mammalian cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 33, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlini C., Scambia G. (2007). Assay for apoptosis using the mitochondrial probes, rhodamine123 and 10-n-nonyl acridine orange. Nat. Protoc. 2, 3111–3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley L. W., Haas W., Desquiret-Dumas V., Wallace D. C., Procaccio V., Gygi S. P., Haigis M. C. (2011). Succinate dehydrogenase is a direct target of sirtuin 3 deacetylase activity. PLoS One 6, e23295.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley L. W., Haigis M. C. (2012). Metabolic regulation by sirt3: Implications for tumorigenesis. Trends Mol. Med. 18, 516–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S., Holmstrom K. M., Skujat D., Fiesel F. C., Rothfuss O. C., Kahle P. J., Springer W. (2010). Pink1/parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on vdac1 and p62/sqstm1. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giralt A., Villarroya F. (2012). Sirt3, a pivotal actor in mitochondrial functions: Metabolism, cell death and aging. Biochem. J. 444, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z. L., Yang X. E., Stoffella P. J. (2005). Trace elements in agroecosystems and impacts on the environment. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 19, 125–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmström K. M., Kostov R. V., Dinkova-Kostova A. T. (2016). The multifaceted role of nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 1, 80–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura Y., Waguri S., Sou Y-s., Kageyama S., Hasegawa J., Ishimura R., Saito T., Yang Y., Kouno T., Fukutomi T., et al. (2013). Phosphorylation of p62 activates the keap1-nrf2 pathway during selective autophagy. Mol. Cell 51, 618–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivankovic D., Chau K. Y., Schapira A. H., Gegg M. E. (2016). Mitochondrial and lysosomal biogenesis are activated following pink1/parkin-mediated mitophagy. J. Neurochem. 136, 388–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A., Lamark T., Sjottem E., Larsen K. B., Awuh J. A., Overvatn A., McMahon M., Hayes J. D., Johansen T. (2010). P62/sqstm1 is a target gene for transcription factor nrf2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22576–22591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansanen E., Kuosmanen S. M., Leinonen H., Levonen A.-L. (2013). The keap1-nrf2 pathway: Mechanisms of activation and dysregulation in cancer. Redox Biol. 1, 45–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuragi Y., Ichimura Y., Komatsu M. (2016a). Regulation of the keap1–nrf2 pathway by p62/sqstm1. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 1, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Katsuragi Y., Ichimura Y., Komatsu M. (2016b). Regulation of the keap1–nrf2 pathway by p62/sqstm1. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 1(Suppl. C), 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Dai J., Fai L. Y., Yao H., Son Y. O., Wang L., Pratheeshkumar P., Kondo K., Shi X., Zhang Z. (2015). Constitutive activation of epidermal growth factor receptor promotes tumorigenesis of cr(vi)-transformed cells through decreased reactive oxygen species and apoptosis resistance development. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 2213–2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Dai J., Park Y. H., Fai L. Y., Wang L., Pratheeshkumar P., Son Y. O., Kondo K., Xu M., Luo J., et al. (2016). Activation of epidermal growth factor receptor/p38/hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is pivotal for angiogenesis and tumorigenesis of malignantly transformed cells induced by hexavalent chromium. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 16271–16281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Kulikov A. V., Luchkina E. A., Gogvadze V., Zhivotovsky B. (2017). Mitophagy: Link to cancer development and therapy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 482, 432–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarou M., Sliter D. A., Kane L. A., Sarraf S. A., Wang C., Burman J. L., Sideris D. P., Fogel A. I., Youle R. J. (2015). The ubiquitin kinase pink1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature 524, 309–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. H., Yu H. S. (2016). Role of mitochondria, ros, and DNA damage in arsenic induced carcinogenesis. Front. Biosci. 8, 312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. C., Yin P. H., Lu C. Y., Chi C. W., Wei Y. H. (2000). Increase of mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA in response to oxidative stress in human cells. Biochem. J. 348(Pt 2), 425–432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. C., Son Y. O., Pratheeshkumar P., Shi X. (2012). Oxidative stress and metal carcinogenesis. Free Radical Biol. Med. 53, 742–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Q., Benavides G. A., Vassilopoulos A., Gius D., Darley-Usmar V., Zhang J. (2013). Bioenergetic and autophagic control by sirt3 in response to nutrient deprivation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Biochem. J. 454, 249–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Fan M., Candas D., Qin L., Zhang X., Eldridge A., Zou J. X., Zhang T., Juma S., Jin C., et al. (2015). Cdk1-mediated sirt3 activation enhances mitochondrial function and tumor radioresistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 14, 2090–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard D. B., Alt F. W., Cheng H. L., Bunkenborg J., Streeper R. S., Mostoslavsky R., Kim J., Yancopoulos G., Valenzuela D., Murphy A., et al. (2007). Mammalian sir2 homolog sirt3 regulates global mitochondrial lysine acetylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 8807–8814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maftah A., Petit J. M., Ratinaud M. H., Julien R. (1989). 10-n nonyl-acridine orange: A fluorescent probe which stains mitochondria independently of their energetic state. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 164, 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris K. C., Lin H. W., Thompson J. W., Perez-Pinzon M. A. (2011). Pathways for ischemic cytoprotection: Role of sirtuins in caloric restriction, resveratrol, and ischemic preconditioning. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 1003–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H.-M., Williams J. A., Ding W.-X. (2015). Mitochondrial dynamics and mitochondrial quality control. Redox Biol. 4, 6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niture S. K., Kaspar J. W., Shen J., Jaiswal A. K. (2010). Nrf2 signaling and cell survival. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 244, 37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. H., Ozden O., Jiang H., Cha Y. I., Pennington J. D., Aykin-Burns N., Spitz D. R., Gius D., Kim H. S. (2011). Sirt3, mitochondrial ros, ageing, and carcinogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12, 6226–6239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini L., Pucci B., Villanova L., Marino M. L., Marfe G., Sansone L., Vernucci E., Bellizzi D., Reali V., Fini M., et al. (2012). Sirt3 protects from hypoxia and staurosporine-mediated cell death by maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential and intracellular ph. Cell Death Differ. 19, 1815–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi H., Xu S., Reiter R. J., Guo P., Zhang L., Li Y., Li M., Cao Z., Tian L., Xie J., et al. (2015). Sirt3-sod2-mros-dependent autophagy in cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity and salvage by melatonin. Autophagy 11, 1037–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai V. B., Sundaresan N. R., Jeevanandam V., Gupta M. P.. 2010. Mitochondrial sirt3 and heart disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 88, 250–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratheeshkumar P., Son Y.-O., Divya S. P., Turcios L., Roy R. V., Hitron J. A., Wang L., Kim D., Dai J., Asha P., et al. (2016). Hexavalent chromium induces malignant transformation of human lung bronchial epithelial cells via ros-dependent activation of mir-21-pdcd4 signaling. Oncotarget 7, 51193–51210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao A., Wang K., Yuan Y., Guan Y., Ren X., Li L., Chen X., Li F., Chen A. F., Zhou J., et al. (2016). Sirt3-mediated mitophagy protects tumor cells against apoptosis under hypoxia. Oncotarget 7, 43390–43400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterstrom F. K., Swindell W. R., Laurent G., Vyas S., Bulyk M. L., Haigis M. C. (2015). Nuclear respiratory factor 2 induces sirt3 expression. Aging Cell 14, 818–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shallari S., Schwartz C., Hasko A., Morel J. L. (1998). Heavy metals in soils and plants of serpentine and industrial sites of albania. Sci. Total Environ. 209, 133–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Someya S., Yu W., Hallows W. C., Xu J., Vann J. M., Leeuwenburgh C., Tanokura M., Denu J. M., Prolla T. A. (2010). Sirt3 mediates reduction of oxidative damage and prevention of age-related hearing loss under caloric restriction. Cell 143, 802–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn M. B., Liby K. T. (2012). Nrf2 and cancer: the good, the bad and the importance of context. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 564–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M., Otsuki A., Keleku-Lukwete N., Yamamoto M. (2016). Overview of redox regulation by keap1–nrf2 system in toxicology and cancer. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 1, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tchounwou P. B., Yedjou C. G., Patlolla A. K., Sutton D. J. (2012). Heavy metals toxicity and the environment. EXS 101, 133–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Son Y. O., Chang Q., Sun L., Hitron J. A., Budhraja A., Zhang Z., Ke Z., Chen F., Luo J., et al. (2011). Nadph oxidase activation is required in reactive oxygen species generation and cell transformation induced by hexavalent chromium. Toxicol. Sci. 123, 399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. J., Sun Z., Villeneuve N. F., Zhang S., Zhao F., Li Y., Chen W., Yi X., Zheng W., Wondrak G. T., et al. (2008). Nrf2 enhances resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs, the dark side of nrf2. Carcinogenesis 29, 1235–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H., Liu L., Chen Q. (2015). Selective removal of mitochondria via mitophagy: Distinct pathways for different mitochondrial stresses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1853(10 Pt B), 2784–2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Nagasawa K., Munch C., Xu Y., Satterstrom K., Jeong S., Hayes S. D., Jedrychowski M. P., Vyas F. S., Zaganjor E., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial sirtuin network reveals dynamic sirt3-dependent deacetylation in response to membrane depolarization. Cell 167, 985–1000.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W., Gao B., Li N., Wang J., Qiu C., Zhang G., Liu M., Zhang R., Li C., Ji G., et al. 2016. Sirt3 deficiency exacerbates diabetic cardiac dysfunction: Role of foxo3a-parkin-mediated mitophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863, 1973–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Davies K. J. A., Forman H. J. (2015a). Oxidative stress response and nrf2 signaling in aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88, 314–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Y., Deng Y. N., Zhang M., Su H., Qu Q. M. (2016). Sirt3 acts as a neuroprotective agent in rotenone-induced parkinson cell model. Neurochem. Res. 41, 1761–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Pratheeshkumar P., Budhraja A., Son Y. O., Kim D., Shi X. (2015b). Role of reactive oxygen species in arsenic-induced transformation of human lung bronchial epithelial (beas-2b) cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 456, 643–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.