Abstract

Elevated levels of plasma free fatty acid (FFA) and disturbed mitochondrial dynamics play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease (DKD). However, the mechanisms by which FFA leads to mitochondrial damage in glomerular podocytes of DKD and the effects of Berberine (BBR) on podocytes are not fully understood.

Methods: Using the db/db diabetic mice model and cultured mouse podocytes, we investigated the molecular mechanism of FFA-induced disturbance of mitochondrial dynamics in podocytes and testified the effects of BBR on regulating mitochondrial dysfunction, podocyte apoptosis and glomerulopathy in the progression of DKD.

Results: Intragastric administration of BBR for 8 weeks in db/db mice significantly reversed glucose and lipid metabolism disorders, podocyte damage, basement membrane thickening, mesangial expansion and glomerulosclerosis. BBR strongly inhibited podocyte apoptosis, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction both in vivo and in vitro. Mechanistically, BBR could stabilize mitochondrial morphology in podocytes via abolishing palmitic acid (PA)-induced activation of dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1).

Conclusions: Our study demonstrated for the first time that BBR may have a previously unrecognized role in protecting glomerulus and podocytes via positively regulating Drp1-mediated mitochondrial dynamics. It might serve as a novel therapeutic drug for the treatment of DKD.

Keywords: diabetic kidney disease, podocyte, mitochondrial fission, dynamin-related protein 1, Berberine

Introduction

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that consistently undergo fusion and fission, frequently changing their number and shape to adapt to variations in metabolic demands. Mitochondrial fission regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy, whereas mitochondrial fusion controls proper distribution of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and metabolic substance across all mitochondria1, 2. Under physiological conditions, the harmonization of mitochondrial dynamics guarantee efficient oxidative phosphorylation (OXOHOS) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production in cells with elongated and filamentous mitochondria3. However, the mitochondrial dynamic balance will shift to fission when cells are under metabolic or environmental stresses. This is accompanied by a fragmented morphology, compromised energy metabolism, increased content of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). Excessive mitochondrial ROS can in return lead to mitochondrial disruption including mtDNA damage and mutations and the release of pro-apoptotic proteins4.

Mitochondrial fission is typically regulated by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), a dynamin family member that binds to its receptors on mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) and assembles a larger oligomer, which finally splits mitochondrial tubules into fragments2, 5. Mediators that promote Drp1 translocating to the MOM, increase Drp1 expression, or regulate the post-translational modification of Drp1 all contribute to mitochondrial fission6, 7. Drp1 may interact with Bax to promote the permeability of MOM, resulting in the release of mitochondrial apoptotic proteins (for example, cytochrome c) to the cytoplasm. These proapoptotic proteins then activate signaling cascade of caspases, eventually resulting in cell apoptosis8. Drp1 knockdown or pharmacologic inhibition by Mdivi1 could be sufficient to block these signaling cascades, thereby preventing mitochondrial fission-induced cell apoptosis9.

Recent advances focusing on mitochondrial biology have proposed that excessive mitochondrial fission and mitochondrial dysfunction in podocytes are typical features of kidney injury, but preceding the clinical manifestations of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) 10. Podocytes are terminally differentiated epithelial cells that form interdigitated foot processes (FPs) constituting the crucial component of the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) to protein leakage 11. Podocyte injury, dedifferentiation and loss are pathological hallmarks of DKD, preceding albuminuria and then exacerbating proteinuria and glomerular sclerosis12. Given that kidney cells need continuous high levels of energy consumption and the mitochondrial OXPHOS is the primary source of ATP production, there exist abundant mitochondria in glomerular cells13. However, persistent hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia in DKD condition can induce podocyte mitochondrial dysfunction as well as excessive mitochondrial fission followed by a range of alterations, including elevated ROS production, cell apoptosis and detachment, which ultimately induce GFB destruction and proteinuria14, 15. Remarkably, increased mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) in podocytes is considered as the critical links for certain pivotal pathogenic mechanisms involving in the glomerulusclerosis and progression of DKD16, 17.

Deregulated lipid metabolism with abnormal FFA metabolism is the typical complication of T2DM 18. Palmitic acid (PA) is the most abundant FFA in humans and rodents plasma that accounts for 25 percent of total content19. The total plasma FFA level can increase up to fourfold in T2DM20. Increased FFA content could cause damage to target organs in DM patients, inducing ROS overproduction, mitochondrial dysfunction and MOM permeability- mediated cytochrome c release followed by cell apoptosis21. Glomerular podocytes are highly sensitive to FFA. Enhanced FFA uptake by podocytes could lead to intracellular lipid accumulation and peroxidation22. The excess cellular ROS in response to high concentrations of FFA is the main culprit for podocyte injury in DKD23.

Berberine (BBR) is a kind of isoquinoline alkaloid present in Chinese herbal medicines and widely used for treating diarrhea and diabetes mellitus (DM)24. BBR has been demonstrated to have various of metabolic benefits, including hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic roles25, improvement of insulin resistance26 and oxidative damage27. Combining the therapeutic effects of BBR with recent observations suggesting Drp1-mediated mitochondrial dynamics as new potential targets against DKD, we hypothesized that BBR might prevent the progression of DKD through regulating Drp1 in podocytes. Our findings clearly showed that podocytes are highly susceptible to PA, which induced cell damage and apoptosis via disturbing mitochondrial morphology and function. Further we demonstrated that BBR significantly attenuated excessive mitochondrial fission, mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS overproduction, which protected podocytes from apoptosis and detachment, thus dramatically preventing the pathological progress of DKD.

Methods

Cell culture

Conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte established and distributed by Professor Peter Mundel of the Medical College of Harvard University (Boston, MA, USA) was provided by First Affiliated Hospital of Peking University (Beijing, China). Cultivation of podocytes was performed as previously reported 28. To induce differentiation (non- permissive condition), podocytes were cultivated without IFN-γ at 37 °C for 10 days. For subsequent experiments, differentiated podocytes were pretreated with 0.4 μmol/L BBR (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) or 10 μmol/L Mdivi1 (MCE, NJ, USA) or basic medium for 12 h. The next day, cells were cultured in medium containing 100μmol/L PA for 12 h.

Palmitate

First, palmitate (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was dissolved in sodium hydroxide solution (0.1 M) at 70 °C for 30 min to form sodium palmitate (40 mM). Palmitate was then combined with fatty-acid-free BSA (Solarbio, Beijing, China). BSA (40%) was dissolved in PBS and added dropwise into the palmitate solution. Then the mixed solution was maintained at 55°C for 30 min. Finally, the PA stock (20 mmol/L) was filtered and stored at - 20 °C until use.

Cell apoptosis assay

For annexin V/PI labeling, cells were incubated with annexin V followed by PI staining (BD Biosciences, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. After adding 400μl 1X Binding Buffer, samples were analyzed immediately by flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur, USA).

Assessment of ROS generation

ROS content was measured with the ROS-sensitive fluorescent probe, 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). After the treatment, podocytes were incubated with 20 μM DCFH-DA at 37°C in the dark for 30 min. Green fluorescence derived from cellular ROS generation was detected by flow cytometry with 525 nm for emission (FACS Aria) or observed by the fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). More than 10,000 cells were acquired for each sample, and the ROS level was quantified by mean fluorescence intensity.

The lipid peroxidation products malondialdehyde (MDA) in podocytes was measured according to procedures of manufacturer (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China) as reported previously29.

To assess production of superoxide in kidney glomerular, dihydroethidium (DHE), the O2—sensitive fluorescent dye, was used as previously described 30. Unfixed frozen kidney sections were incubated with 1 μmol/L DHE at 37°C in dark for 30 minutes and then coverslipped. Tissue sections were then observed with a fluorescence microscope.

Measurement of ATP levels

Contents of ATP were assessed with a bioluminescence assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The measurement was conducted as previously described 31. After the treatment, supernatants were removed and podocytes were lysed in the ATP assay buffer for 5 min. Cells from each well were then collected for centrifugation. The supernatant fraction was put into a 96-well clear bottom, black-walled microplate (Corning Incorporated, NY, USA) and then luciferase reagent was added. The luminescence was detected by a luminometer (Synergy, BioTek Instruments, USA).

MMP measurement

MMP was determined using the lipophilic cationic dye JC-1 (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) as described previously31. The ratio of red to green (590/520) fluorescence reflects the MMP. In this experiment, podocytes were loaded with JC-1 in the dark for 20 min and fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. For imaging, cells were observed by the fluorescence microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

To analyze ultrastructure changes in the glomerulus and podocyte mitochondria, Kidney tissues and podocytes were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde for 12 h at 4℃, then post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide. Fixed sections were dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol, then infiltrated, embedded and sliced with ultramicrotome. Uranyl acetate and lead citrate were used to stain the sections. Finally, the transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) was used for examining and photographing these sections.

Extraction of podocytes and glomerular mitochondria

Mitochondria from podocytes were isolated using a mitochondria isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Isolated mitochondria were lysed in buffer and the protein concentration were measured by the Bradford method.

Western blot analyses

Western blotting was performed according to the standard methods. Briefly, samples were lysed in buffer on ice and then centrifuged. Protein concentrations were measured with a BCA Protein Assay Kit. The lysates were mixed with loading buffer and boiled for 10 min. Protein samples (60µg each group) were loaded on SDS-PAGE, separated and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane using standard procedures. Membranes were then probed with appropriate antibodies. The detection of signal was pictured with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Anti-COX Ⅳ and β-actin antibody were used as loading controls for mitochondria and cytoplasm respectively. The antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry

For mitochondria staining in cultured podocytes, cells were grown on glass coverslips and mitochondrial morphology was visualized by labeling the cells with 50 nmol/L MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in the dark for 30 min at 37°C. Images were then acquired by laser scanning confocal microscopy (Leica Microsystems, 100X oil objective).

For mitochondria colocalization with Drp1, podocytes were pretreated with 50 nM MitoTracker Red first. They were then fixed paraformaldehyde, blocked with certain serum and incubated with appropriate primary antibodies and FITC-labeled secondary antibody. Nuclei was counterstained with DAPI for 5 min. Staining was observed by a fluorescence microscope or the confocal microscopy.

For kidney paraffin sections, after dewaxing, rehydration, antigen retrieval, reducing endogenous peroxidase activity and blocking, sections were then incubated with primary antibodies and HRP or FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit/anti-mouse secondary antibodies and then observed with fluorescence microscope. Glomerular podocytes in kidney tissues were specially labeled with podocin.

Analyses of mitochondrial morphology

Mitochondrial shape and size were measured and quantified using Image J (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) as previously described 32-34. For immunofluorescence images, computer-assisted quantitative analyses were used for tracing the mitochondrial branches. Punctate was defined as cells with spherical shape (no clear length or width). Rod indicated individual mitochondria with a tubular structure, and network was defined as cells with highly interconnected mitochondria.

For TEM micrographs, we manually traced only clearly discernible outlines of mitochondria. Morphological parameters including surface area, perimeter, the longitudinal length (major axis) and equatorial length (minor axis) were measured automatically by the Image J software. The aspect ratio [AR, (major axis)/(minor axis)] and form factor [FF, (perimeter2)/(4π·surface area)] which reflect the branching aspect of mitochondria were calculated. Both AR and FF have a minimal value of 1 that indicates a small perfect spheroid. Increase of the values represents the shape becoming elongated and branched. Circularity [4π·(surface area/perimeter2)] and roundness [4·(surface area)/(π·major axis2)] were calculated as indexes of sphericity with a maximum value of 1 indicating a perfect circle.

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was extracted from samples using the Trizol reagent (Takara, Japan). The Thermo Scientific NanoDrop spectrophotometer was used to detect the purity and concentration of RNA. Then, cDNA was synthesized using the reverse transcriptase kit (Takara, Japan). Quantitative analysis of mRNA expression was conducted with a SYBR premix EX TaqTM kit (Takara, Japan) with StepOne PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA). The relative quantity of mRNA was expressed as 2-△△CT. Sequences of the primers are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

mtDNA content quantification

To evaluate mtDNA copy number, NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (ND1) encoded on the mitochondrial genome were used as mtDNA marker. 18S ribosomal RNA served as an endogenous control. Quantitative Real-Time PCR was conducted according to the standard methods described previously 35.

Lentiviral infection

For preparation of Drp1 overexpression podocytes, mouse Drp1 overexpressing lentiviral particles were used with the scramble lentiviral particles (Gene, Shanghai, China) as control. Cells were first seeded in plates. Then they were infected with lentivirus stock and 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA) and incubated for 12 h. Cells were then switched to normal culture medium and selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin (TOCRIS). The expression of Drp1 was examined by western blotting and quantitative-RT PCR. After lentiviral transfection, the cells were treated with BBR or PA for subsequent experiments.

siRNA-mediated gene silencing

Podocytes were grown to 40% confluent in six-well plates. Drp1 siRNA and control siRNA (Ruibobio, Guangzhou, China) were transfected into cells using GenMute transfection reagent (SignaGen, USA) at 50 nmol/L of siRNA according to manufacturer's protocol. More than 90% of cells were successfully infected as indicated by GFP expression after 36 h. After siRNA transfection, the cells were treated with BBR or PA for subsequent experiments.

Animal experiments

Animal maintenance and all experimental procedures were conducted according to the NIH guidelines for use of laboratory animals with approval of the Animal Care Committee of Huazhong University of Science and technology (Wuhan, China). Male db/db diabetic mice and the nondiabetic littermates (7 weeks old) were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University and socially housed at a constant temperature of 22°C ± 2°C with a 12:12 h light/dark cycle. Diabetic db/db mice were randomly separated into different groups (db/db and db/db + BBR; n = 10 in each subgroup) and treated with either BBR (300 mg/kg/d) or vehicle by gavage for the next 8 weeks. BBR dosage used in our experiment was chosen according to animal studies and clinical trials previously reported36-38. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) and body weight were monitored at 11 and 15 weeks of age. After intervention, urinary albumin and creatinine concentration were also measured by the ELISA kit. Then all experimental subjects were killed under anesthesia. The distal parts of each kidney were either fixed overnight with 4% formaldehyde or preserved at -80°C. Mouse glomeruli and podocytes were isolated according to the methods previously reported before conducting western blotting and PCR9, 39. For outcome assessments, a minimum of five mice per group were examined by investigators.

Kidney Histopathology

After mouse was anesthetized, kidneys were taken out immediately and cut in half. The distal parts of each kidney were fixed overnight with 4% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and then sliced at a thickness of 5 μm. For morphometric lesion analysis, hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and periodic acid-schiff (PAS) were conducted. The general histologic changes in mouse glomeruli including glomerular volume, the mesangial area and glomerular basement membrane were determined. Five mice per group and a minimum of 50 glomeruli in three sections per animal were examined.

Tissue FFA analyses

FFA content in kidney podocytes were measured using the FFA quantification kit (Abcam) following the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, the samples were homogenized in buffer and protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay. The homogenate was mixed with chloroform and centrifuged. Then the organic phase was collected and the lipids in which were dried and dissolved in Free Acid Assay Buffer for measurement. The FFA content were normalized to protein concentration.

Statistical Analyses

All the data were expressed as mean ± SEM, except morphological parameters of mitochondria shown as the median (interquartile range). Multiple groups were compared by performing one-way ANOVA following Tukey multiple comparisons tests. P-values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant and all tests were two tailed. GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for performing the tests.

Results

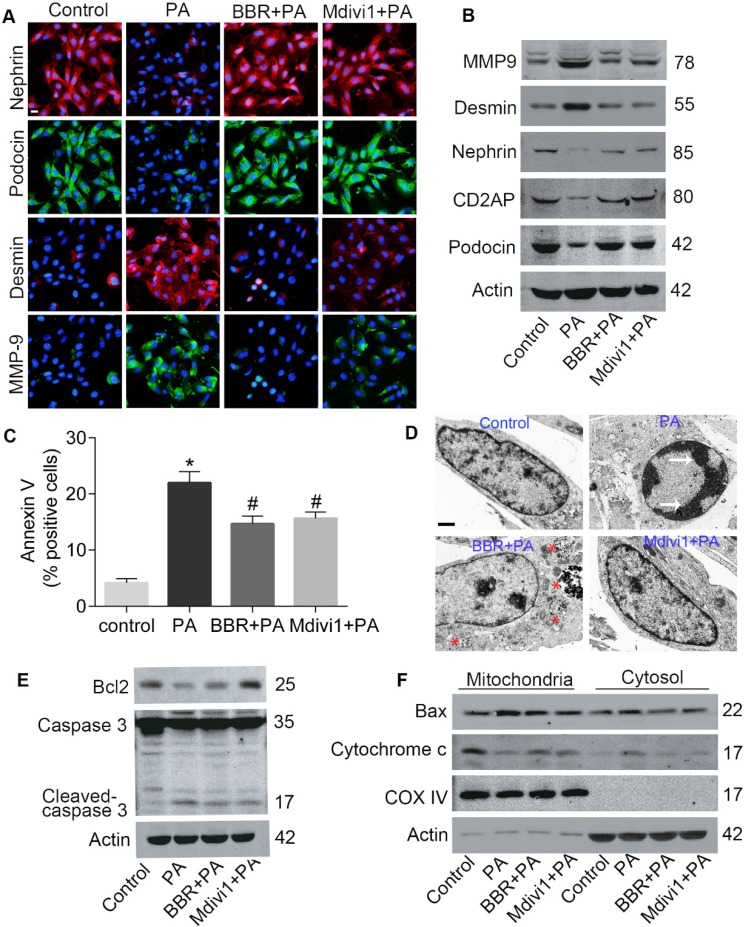

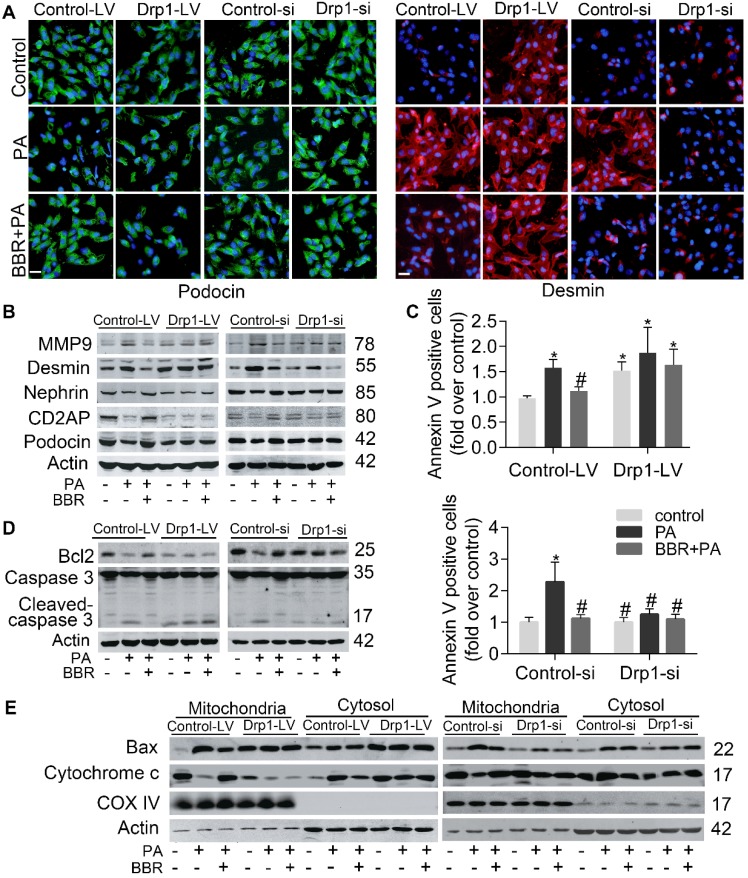

Effects of BBR on PA-induced podocyte damage and apoptosis

The protective effects of BBR on podocytes were tested using cultured mouse podocyte (MPC-5). We first examined those important slit diaphragm proteins (SDs) forming between adjacent interdigitating podocyte FPs12. As shown in Figure 1A-B, the protein expressions of nephrin, podocin and CD2AP in podocytes cultured with PA markedly decreased. However, the SDs levels increased with the treatment of BBR as well as Mdivi1. Besides, BBR and Mdivi1 greatly repressed the protein expressions of desmin and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) which are the markers of podocyte injury and dedifferentiation 40, 41.

Figure 1.

Effects of BBR on PA-induced podocyte injury and apoptosis. (A) SDs and markers of podocyte dedifferentiation were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Nephrin, red; Podocin, green; Desmin, red; MMP-9, green. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Western blotting of SDs and markers of podocyte dedifferentiation. (C) Cell apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry after annexin V/PI staining. Annexin Ⅴ positive cells indicate early apoptosis. (D) Cell apoptosis related condensation of chromatin in nucleus and autophage were observed using TEM. Arrows indicate the condensation of chromatin; * indicates autophagosomes. Scale bars, 1 μm. (E) Levels of apoptotic protein caspase 3 and antiapoptotic protein Bcl2 in podocytes by western blotting. (F) Western blots of Bax and cytochrome c in mitochondria and cytosol. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. Control; #P < 0.05 vs. PA. BBR, Berberine; PA, palmitate; SDs, slit diaphragm proteins; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; TEM, transmission electron microscope.

We next detected the role of BBR on PA-induced cell apoptosis and caspase 3 activation. As shown in Figure 1C, BBR treatment strongly suppressed podocyte apoptosis assessed by annexin V/PI staining. Through the TEM we observed PA-induced condensation of chromatin which is the essential step and hallmark of morphologic changes in the nucleus during apoptosis42. The abnormal changes were restored with the treatment of BBR (Figure 1D). The results also showed that BBR could promote autophagy in cells under stress conditions, in accordance with previous findings43. Besides, BBR lowered the level of activated caspase 3 and elevated the expression of antiapoptotic protein Bcl2 (Figure 1E).

Previous studies have shown that under stress conditions, Bax can be activated and translocate from the cytosol to the mitochondria, promoting the release of cytochrome c and cell apoptosis8. Accordantly, we found that mitochondria Bax (mtBax) and cytosolic cytochrome c increased in cells upon their exposure to PA (Figure 1F). However, both were strongly abolished by BBR treatment. These data indicated that BBR could protect podocytes from PA-induced damage and apoptosis.

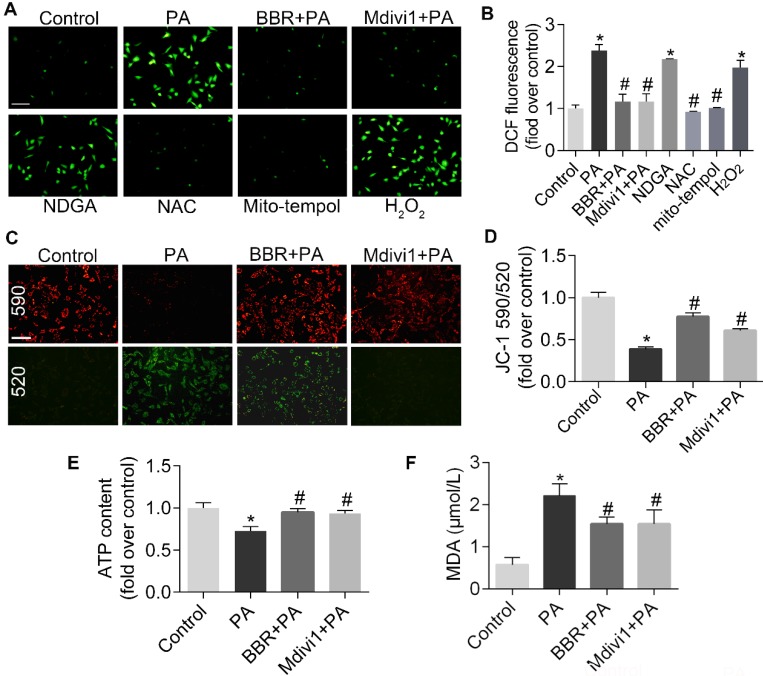

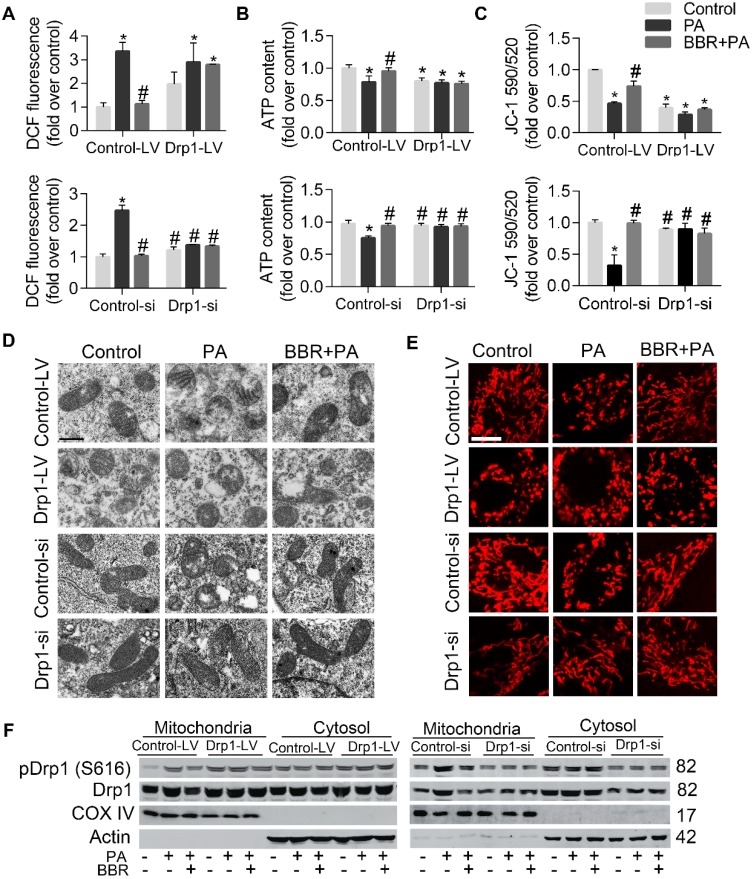

BBR inhibits PA-induced mtROS production, mitochondrial dysfunction and fragmentation in podocytes

As byproduct of electron transport, ROS generated in the mitochondria can take up about 80% of superoxide produced in the basal state. Under stress conditions, mtROS production induces mtDNA damage and mutations followed by cell apoptosis. Thus, ROS is both the marker and chief culprit of mitochondrial dysfunction and damage4. As shown in Figure 2A-B, PA-induced intracellular ROS generation, measured by staining DCFH-DA fluorescence dye using fluorescence microscope and flow cytometry, was significantly increased. It was similar to that of pro-oxidants H2O2 (1 μmol/L). BBR, Mdivi1, as well as total antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC)44 and mitochondrial antioxidant mito-tempol45, blocked ROS production in podocytes, except for cytosol antioxidant nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA)46.

Figure 2.

BBR inhibited PA-induced mtROS production and mitochondrial dysfunction in podocytes. (A, B) Cellular ROS production was detected by fluorescence microscopy (A) and flow cytometry (B) after DCFH-DA staining. Scale bar, 200 μm. (C, D) MMP was detected by fluorescence microscopy (C) and flow cytometry (D) after JC-1 staining. Scale bar, 200 μm. (E) ATP content were assayed in cells of different conditions. (F) MDA content was measured in podocytes. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. Control; #P < 0.05 vs. PA. BBR, Berberine; PA, palmitate; ROS, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species; NDGA, nordihydroguaiaretic acid; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; DCF, dichlorofluorescein; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; MDA, malondialdehyde.

Mitochondrial oxidative stress can disturb the MMP and ATP synthesis which reflect mitochondrial function47. In the present study, we observed PA-induced disruption of MMP and ATP production, and both were reversed with the treatment of BBR or Mdivi1(Figure 2C-E). BBR also reduced lipid peroxidation products-MDA, as shown in Figure 2F.

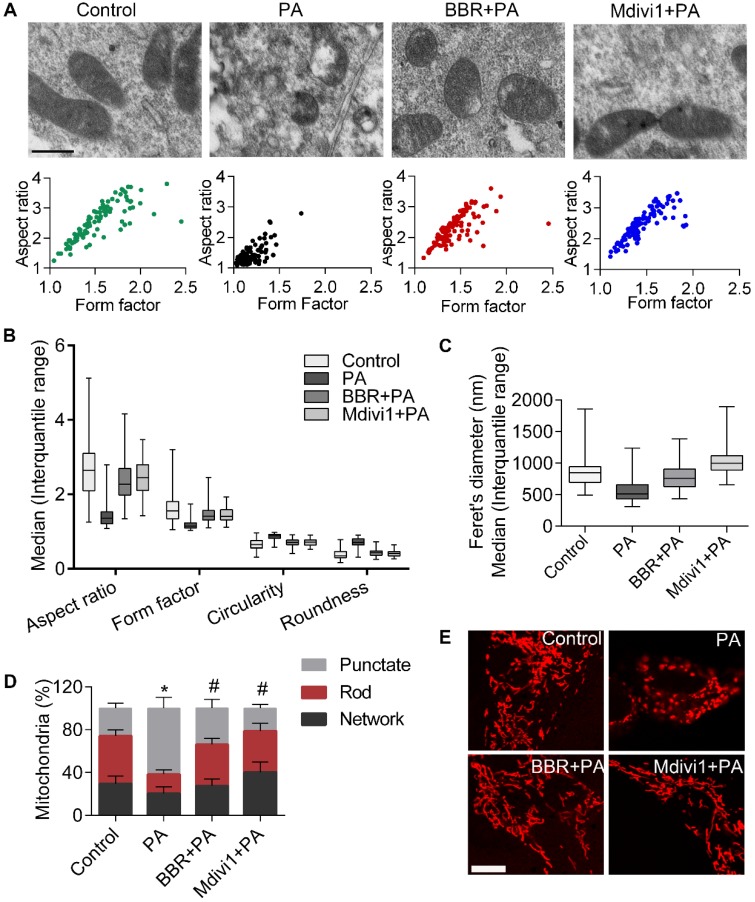

We next examined alterations of mitochondrial ultrastructure by using TEM. As shown in Figure 3A, cells treated with PA showed small punctate and rounded mitochondria when compared with controls. However, mitochondria from BBR-treated cells phenocopied those from Mdivi1 treatment, displaying interconnected, filamentous and tubular shape. For quantitative analysis of mitochondrial morphology, a series of parameters were used, including aspect ratio and form factor with bigger values indicating more elongated mitochondria (Figure 3A-B) and circularity and roundness with bigger values indicating more rounded mitochondria (Figure 3B). Besides, mitochondrial length was measured, as shown in Figure 3C. Mitochondrial morphology visualized by mitochondrial fluorescent probe (MitoTracker Red CMXRos) also showed the similar change (Figure 3D-E). Collectively, these results suggested that the protective roles of BBR in podocytes were possibly through eliminating mitochondrial ROS and modulating mitochondria morphology and function.

Figure 3.

BBR inhibited PA-induced mitochondrial fragmentation in podocytes. (A) Mitochondrial morphology was observed by TEM and assessed by aspect ratio and form factor using Image J from three independent experiments (>100 mitochondria). Scale bars, 500 nm. (B) Aspect ratio, form factor, circularity, and roundness were quantified for each condition (>100 mitochondria). (C) Feret's diameter that reflects the longitudinal mitochondrial length was measured by Image J analysis (>100 mitochondria). (D) Quantification of the mitochondrial morphology shown in (E) by Image J analysis from three independent experiments (>500 mitochondria). (E) Mitochondria were stained by MitoTracker Red and imaged by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm. Error bars represent mean ± SEM, except morphological parameters of mitochondria shown as the median (interquartile range). *P < 0.05 vs. Control; #P < 0.05 vs. PA. BBR, Berberine; PA, palmitate; TEM, transmission electron microscope.

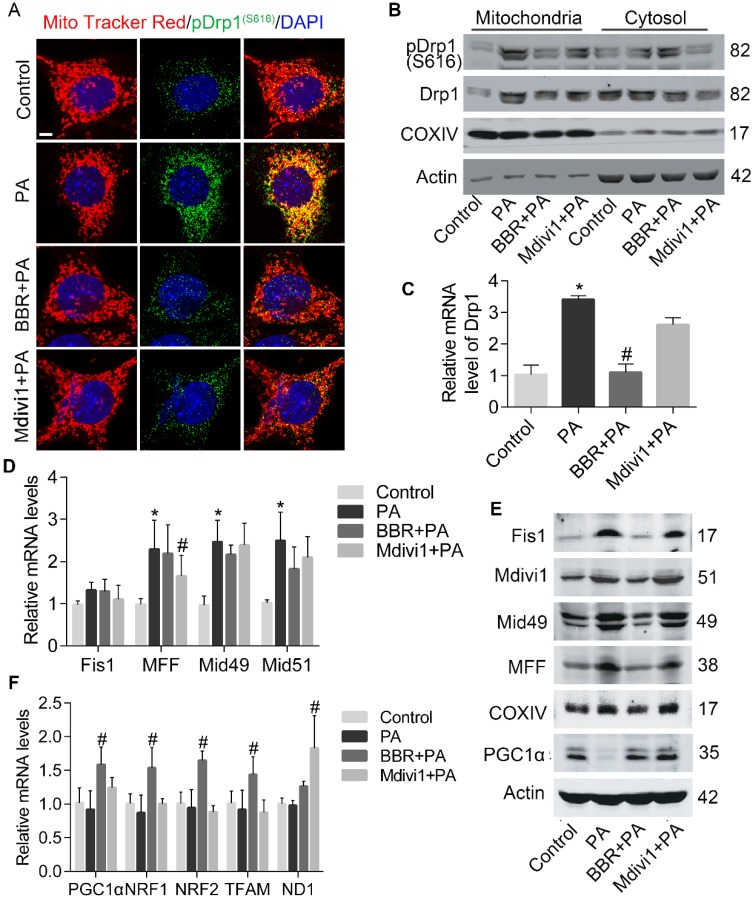

BBR blocks Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in podocytes cultured with PA

Since Drp1 is the critical mediator of mitochondrial fission, we next examined whether Drp1 activity in podocyte was influenced after PA and BBR intervention. As shown in Figure 4A-C, PA-induced overexpression of Drp1 in mRNA and protein were both abolished by BBR treatment. Besides, BBR could suppress Drp1 translocation to the mitochondria and suppress its phosphorylation at Serine 616 site. To further investigate the possible mechanism, we tested the expression of Drp1 receptors that may help recruit Drp1 to the MOM48. Our results showed that levels of mitochondrial fission protein (MFF), mitochondrial fission protein 1 (Fis1), mitochondrial dynamics proteins (Mid49, Mid51) were simultaneously down-regulated by BBR administration, but BBR failed to inhibit the gene transcription of these receptors (Figure 4D-E).

Figure 4.

BBR prohibited PA-induced mitochondrial fission via regulating Drp1 in podocytes. (A) Immunofluorescence of MitoTracker and pDrp1 (S616). MitoTracker, red; pDrp1 (S616), green; DAPI, blue; merge, yellow. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) Western blotting of Drp1 and pDrp1 (S616) protein expression in mitochondria and cytosol. (C) Gene expression of Drp1 was determined by RT-PCR. (D) Mitochondrial fission-related gene expression profile in podocytes. (E) Western blots showing the levels of mitochondrial fission-related proteins. (F) Mitochondrial biogenesis-related gene expression in podocytes. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. Control; #P < 0.05 vs. PA. BBR, Berberine; PA, palmitate; Drp1, dynamin-related protein 1; RT-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR; Mid51 and Mid49, mitochondrial dynamics proteins of 51 and 49 kDa; Fis1, mitochondrial fission protein 1; MFF, mitochondrial fission protein; PGC1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ co-activator 1α; TFAM, transcription factor A, mitochondrial; NRF1 and NRF2, nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2.

Given that oxidative stress can affect mitochondrial biogenesis and damage mtDNA4, and BBR could significantly reverse mitochondria number decrease induced by PA as demonstrated above (Figure 3E), we thus evaluated several transcription factors that regulate mitochondrial biogenesis 49. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ co- activator 1α (PGC-1α) is the primary regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and energy metabolic homeostasis50. We found that the expression levels of PGC-1α were upregulated by BBR (Figure 4E-F). Other markers of mitochondrial biogenesis were also checked and significantly increased in BBR group, including transcription factor A of mitochondria (TFAM), nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (NRF1, NRF2). However, BBR failed to increase mtDNA copy number reflected by gene expression of ND1 (Figure 4F).

To further elucidate whether podocyte damage and mitochondria dysfunction could be induced by directly increasing Drp1 level but prevented by Drp1 downregulation, we upregulated Drp1 expression by infecting podocytes with lentivirus expressing Drp1 and downregulated its level with Drp1-specific siRNA (with empty lentivirus and scramble oligonucleotide acting as controls, respectively). The role of Drp1 was confirmed in promoting cell injury and apoptosis (Figure 5A-E), mitochondrial dysfunction (Figure 6A-C), mitochondria fragmentation (Figure 5D-E). The protective effects of BBR on PA-induced cell damage were largely abolished by Drp1 overexpression and enhanced by Drp1 downregulation (Figure 5A-E, Figure 6A-F). These results demonstrated that BBR might protect podocytes from PA-induced cell damage and mitochondrial dysfunction mainly through inhibiting mitochondria Drp1 activity.

Figure 5.

Upregulation and downregulation of Drp1 blunted and enhanced the effects of BBR on cell injury and apoptosis in PA-treated podocytes respectively. (A) Effects of Drp1 upregulation and downregulation on PA-induced podocyte injury in the presence or absence of BBR. Podocin (left panel) and desmin (right panel) protein expression were detected by fluorescence microscopy. Podocin, green; Desmin, red. Scale bars, 200 μm. (B) Western blots indicating Drp1 upregulation (right panel) and downregulation (right panel) blunted and enhanced the effects of BBR on PA-induced podocyte injury respectively. (C) Effects of Drp1 upregulation (upper panel) and downregulation (lower panel) on PA-induced apoptosis in the presence or absence of BBR were measured by flow cytometry. (D) Effects of Drp1 upregulation (left panel) and downregulation (right panel) on podocyte apoptosis. Protein expression of apoptotic family members were detected by western blotting. (E) Cell apoptosis-associated Bax and cytochrome c levels in mitochondria and cytosol were assessed by western blotting after Drp1 upregulation (left panel) and downregulation (right panel). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. Control; #P < 0.05 vs. PA. BBR, Berberine; PA, palmitate; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; Drp1, dynamin-related protein 1; LV, lentivirus; si, si RNA.

Figure 6.

The effects of BBR on mitochondrial fission in PA-treated podocytes were blunted and enhanced by Drp1 upregulation and downregulation respectively. (A) Upregulation and downregulation of Drp1 blunted and enhanced the effects of BBR on cellular ROS production in PA-treated podocytes respectively, assessed by flow cytometry. (B) The effects of BBR on ATP production in PA-treated podocytes was blunted and enhanced by upregulation and downregulation of Drp1 respectively. (C) The effects of BBR on mitochondrial membrane potential in PA-treated podocytes were blunted and enhanced by upregulation and downregulation of Drp1 respectively, measured by flow cytometry. (D) The effects of BBR on mitochondrial morphology after upregulation and downregulation of Drp1 was observed by TEM. Scale bars, 500 nm. (E) The effects of BBR on mitochondrial morphology after upregulation and downregulation of Drp1 was visualized by MitoTracker Red. Scale bars, 10 μm (F) Western blotting of Drp1 and pDrp1 (S616) protein expression in cytosol and mitochondria after upregulation and downregulation of Drp1. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. Control; #P < 0.05 vs. PA. BBR, Berberine; PA, palmitate; Drp1, dynamin-related protein 1; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DCF, dichlorofluorescein; LV, lentivirus; si, si RNA; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; TEM, transmission electron microscope.

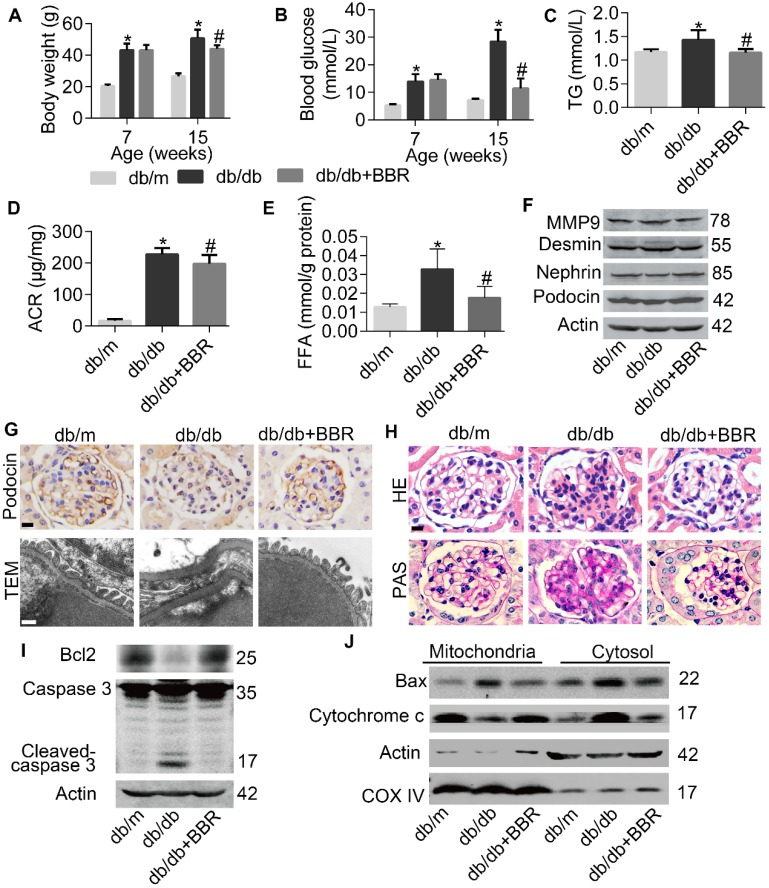

BBR ameliorates DKD symptoms and protects glomerular podocytes in db/db mice

Then we evaluated whether BBR treatment in mouse models of DKD has analogous results found in cultured podocytes. As shown in Figure 7A-7E, body weight, FBG, plasma triglyceride (TG), microalbumin- to-creatinine ratios (ACR) and kidney FFA in db/db mice were all decreased with the treatment of BBR. And consistent with in vitro results that BBR could prevent excessive FFA-induced podocyte injury, decreased expression of SDs and elevated protein level of desmin in glomerular podocytes from db/db mice were detected and reversed by BBR treatment (Figure 7F). We also observed that glomeruli from db/db mice exhibited decreased numbers of podocytes quantified by staining podocin (a podocyte-specific cytoplasmic protein) (Figure 7G, row 1), effacement of foot processes (Figure 7G, row 2), increased mesangial matrix accumulation (Figure 7H, row 1) and incrassation of glomerular basement membrane (Figure 7H, row 2). These pathological changes in diabetic mice were attenuated in different degrees with the treatment of BBR, similar to the histomorphology observed in nondiabetic controls. Through measuring the expression of apoptotic family members, we found that podocyte apoptosis in db/db mice was significantly increased when compared with nondiabetic controls, and this was markedly improved with the administration of BBR (Figure 7I-J). Taken together, our data demonstrated the beneficial effect of BBR on the key symptoms of DKD.

Figure 7.

BBR prevented progression of DKD in db/db mice. (A) Body weight of mice before and after intervention. (B) Fasting blood glucose at two points. (C) Blood TG in different groups. (D) Microalbumin-to-creatinine ratios (ACR) in different groups. (E) FFA levels in kidney glomeruli from different groups. (F) SDs and markers of podocyte injury in kidney glomeruli were detected by western blotting. (G) Podocin staining of podocytes (row 1) and TEM of podocyte foot processes and glomerular basement membrane (row 2). Scale bars, 10μm for row 1, 500 nm for row 2. (H) Representative micrographs of HE (row 1) and PAS (row 2)-stained kidney sections from different groups treated with or without BBR. Scale bars, 10 μm for row 1 and 2; (I) Levels of apoptotic family members in glomerular podocytes were detected by western blotting. (J) Western blotting reflected the levels of Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic Bax and cytochrome c in glomerular podocytes. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. db/m; #P < 0.05 vs. db/db. BBR, berberine; TG, triglyceride; ACR, microalbumin-to-creatinine ratios; FFA, free fatty acids; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; HE, hematoxylin-eosin; PAS, periodic acid-schiff. SDs, slit diaphragm proteins; TEM, transmission electron micrographs.

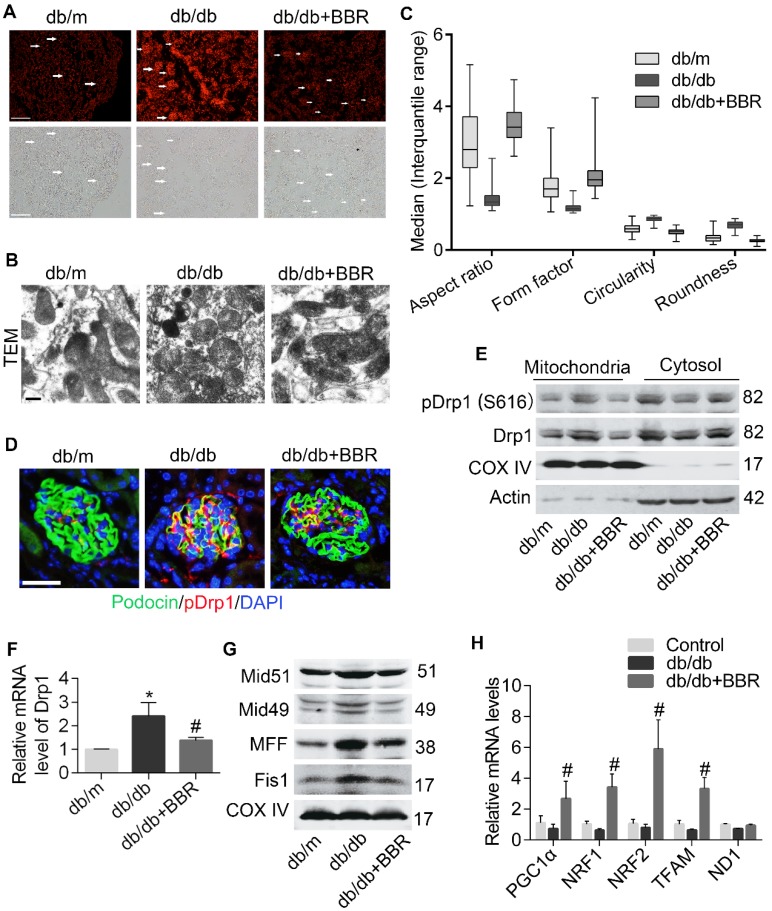

BBR prevents mitochondrial dysfunction of podocytes in DKD mice

We next tested the effect of BBR on podocyte mitochondria in DKD mice. Because increased FFA could induce excessive ROS which causes damage to mitochondria, we measured levels of oxidative stress in kidney tissue via DHE staining and found that these were markedly alleviated by BBR, both in kidney glomeruli and tubules of diabetic mice (Figure 8A). Mitochondrial ultrastructure in diabetic glomerular podocytes showed punctate and round shape, whereas samples from BBR-treated mice had marked improvement in morphology with clearly elongated mitochondria (Figure 8B-C). Therefore, BBR treatment significantly prevented the mitochondrial fragmentation of podocytes in db/db mice.

Figure 8.

BBR attenuated Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in db/db mice. (A) The ROS content in glomeruli were measured by DHE staining. Arrows indicate the glomeruli. Scale bars, 200 μm. (B, C) Mitochondrial morphology in glomerular podocytes was observed by TEM (B) and quantified by image j (C), as reflected by aspect ratio, form factor, circularity, and roundness. A minimum of 50 glomeruli in three sections per animal were assessed (n = 5-8/group, >100 mitochondria). Scale bars, 500 nm. (D) Immunofluorescence of kidney sections stained with podocin (green) and pDrp1 (S616) (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 50 μm. (E) Western blotting of Drp1 and pDrp1 (S616) protein expression in glomerular podocytes. (F) Gene expression of Drp1 was determined in kidney glomeruli. (G) The changes of mitochondrial fission-related proteins in kidney glomeruli were assessed by western blotting. (H) Mitochondrial biogenesis-related gene expression in kidney glomeruli. Error bars represent mean ± SEM, except morphological parameters of mitochondria shown as the median (interquartile range). *P < 0.05 vs. db/m; #P < 0.05 vs. db/db. BBR, berberine; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DHE, dihydroethidium; Drp1, dynamin-related protein 1; TEM, transmission electron micrograph; Mid51 and Mid49, mitochondrial dynamics proteins of 51 and 49 kDa; Fis1, mitochondrial fission protein 1; MFF, mitochondrial fission protein; PGC1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ co-activator 1α; TFAM, transcription factor A, mitochondrial; NRF1 and NRF2, nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2.

Then we clarified the contribution of BBR in blocking Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation in DKD mice. The results showed that BBR markedly prevented Drp1 translocation to the mitochondria in podocytes from DKD (Figure 8D-8E), as reflected by western blotting and immunofluorescence analysis. BBR also inhibited the gene transcription of Drp1 (Figure 8F). To further certify the role of BBR on mitochondrial fission, we detected Drp1 receptors (MFF, Fis1, Mid49 and Mid51) in DKD mice. Our data indicated that these protein levels were increased under DKD conditions and were reversed by BBR treatment (Figure 8G). Whereas the gene levels related to mitochondria biogenesis did not show a significant decline in db/db mice, there exhibited a marked increase by BBR treatment (Figure 8H). Collectively, these results suggested that BBR could modulate mitochondrial dynamics through preventing Drp1 expression and translocation to the mitochondria and promoting mitochondria biogenesis.

Taken together, our findings revealed that Drp1 translocation from cytoplasm to mitochondria is a key event in the pathogenesis of DKD. The inhibition of Drp1 activity by BBR may be beneficial to enhancing mitochondrial fitness and slowing the progression of DKD.

Discussion

In the current study, the renoprotective role of BBR associated with podocyte mitochondria and the underlying mechanism were explored. Our findings indicated that BBR could regulate the metabolic abnormalities including hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia in db/db mice. BBR also ameliorated the symptoms of DKD by relieving glomerular sclerosis, albuminuria and podocyte damage in vivo. The possible mechanism is that BBR could alleviate FFA-induced podocyte injury through suppressing Drp1-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction.

Previous studies suggested podocytes are highly sensitive to FFA. Enhanced FFA uptake by podocytes could lead to intracellular lipid accumulation and peroxidation, insulin resistance, endoplasmic reticulum stress and excessive ROS generation 22. However, the specific molecular mechanism that couple FFA-induced ROS with podocytes apoptosis and the role of BBR remain unknown. Our results showed that elevated FFA could induce podocyte damage and excessive mtROS production, which could be abolished by BBR treatment via modulating Drp1-mediated mitochondrial dynamics. This was consistent with a recent research that podocyte- specific deletion of Drp1 in mouse model significantly reduced albuminuria and mitochondria fragmentation, accompanied by better mitochondrial fitness, increased oxygen consumption and ATP generation 9. Another study found phosphorylating Drp1 at ser600 residue could promote its recruitment to the mitochondria, thus triggering hyperglycemia-induced mitochondrial fission in podocytes51. However, the two phosphorylation sites of Drp1 (ser616 and ser637) in mitochondrial fission have remained controversial 6, 7, 52. Therefore, we examined both Drp1 ser616 and ser 637. Then we found only the protein levels of Drp1 ser616 were markedly different between groups both in vivo and in vitro. Our interpretation is that the effect of phosphorylation of Drp1 may be cell-type/ tissue/stimulus dependent. Specifically, podocytes in our experimental models were pretreated with BBR/Mdivi1 before being exposed to PA. How the phosphorylation of Drp1 might regulate mitochondrial dynamics deserve further exploration in future research.

Recent Studies suggest excessive mitochondrial fission in human and mouse podocytes is closely linked to key features of DKD 10, 17. Considering the pivotal role of mitochondrial dynamics disorder and ROS damage in the development of DKD, one study demonstrated that metformin, which is a well-known hypoglycemic drug, could markedly alleviate renal interstitial fibrosis and glomerular damage via regulation of oxidative stress-related gene expression53. Other research also found antioxidant agents could selectively accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix, thus reduce proteinuria and glomerular damage in diabetic mice54-56. For example, specific targeting of mitochondrial ROS with antioxidants could bring benefits to DKD rodent models by improving mitochondrial bioenergetics57. However, some limitations exist for current therapy targeting at mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. For example, since these are various cell biology, it can be very difficult to achieve the desired effect on cell type and tissue specific without disturbing organs other than the kidney 58.

Our attempts to define the effects of BBR on mitochondria dysfunction indicated that BBR treatment could block Drp1-mediated mitochondrial damage and excessive ROS generation in podocytes. These results were consistent with previous findings that BBR could relieve endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in aldosterone or high glucose-induced podocytes27, 59. The mechanism involved might be that BBR could ameliorate podocyte apoptosis and symptoms of DKD through regulating TLR4/NF-κB pathway or TGFβ1/PI3K/ AKT pathway60-62. Interestingly, researchers have recently demonstrated mitochondrial dysfunction in glomerular endothelial cells is the critical characteristic of DKD, which precedes podocyte apoptosis57. These findings not only provide new insights into how mitochondrial dysfunction in glomerular cells might exert great influence in the development of DKD, but also identified possible therapeutic targets for DKD treatments. BBR has also been tested to alleviate renal fibrosis via multiple signaling pathways, including regulation of NRF2 pathway, TGF-β/Smad pathway and Notch/snail pathway in renal tubular cells, and the AGEs-RAGE pathway in mesangial cells63-66. Further comprehensive investigation is needed to assess the multiple effects of BBR on renal cells in DKD, which could promote the clinical application of BBR and provide alternative therapy for DKD patients.

The investigation of renoprotective role of BBR was still limited to animal research. Although numerous clinical studies have demonstrated its strong effects in the treatment of DM67-69, there was few studies at this stage about the usage of BBR in DKD patients. These previous results strongly suggested the efficacy and safety of BBR in treatment of patients with DM and dyslipidemia, with little side effects38. It is worth noting that functions of the liver and kidney were improved greatly with BBR treatment by regulating liver enzymes and improving renal function38. The mechanism of BBR in glucose- lowering action in target organs may be different, but there still exist similarities. Therefore, BBR might be a suitable substitute for DKD treatment in regulating metabolic abnormalities and relieving renal injury over long-term therapy, considering less cost and adverse effects. Large controlled clinical trials with high quality are needed to further assess the efficacy and safety of berberine in the treatment of DKD.

Previous discoveries have illuminated the novel correlation between mitochondrial fission and the progression of DKD and indicated Drp1 may be a potential therapeutic target in DKD. In the present study, we found that through inhibiting the expression and translocation of Drp1, BBR potently improved the fragmentation and dysfunction of mitochondria in podocytes, reduced mesangial matrix expansion, GBM thickening, podocyte damage, albuminuria and metabolic abnormalities of DKD. In summary, our study provided the first evidence that inhibiting Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission and cell apoptosis might be one of the possible mechanisms of BBR in preventing FFA-induced podocytes damage, which shed insights into the role of BBR as a new prospective agent against DKD. However, there still exist great challenges for future research in protecting podocytes for the treatment of DKD.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81473637, 81673928, 81874382, 81703869); the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant number JDZX2015214).

Author contributions

Xin Qin conceived the experiments, contributed to research data and wrote the manuscript; Yan Zhao, Jing Gong, Wenya Huang and Fen Yuan contributed to mouse experiments; Xin Qin and Hao Su contributed to cell experiments; Hui Dong and Fuer Lu reviewed the manuscript. Hui Dong, Fuer Lu, Ke Fang, Dingkun Wang, Jingbin Li, Lijun Xu and Xin Zou discussed the experiments and manuscript.

Abbreviations

- FFA

free fatty acid

- DKD

diabetic kidney disease

- BBR

berberine

- PA

palmitic acid

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Drp1

dynamin-related protein 1

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- MMP

mitochondrial membrane potential

- MOM

mitochondrial outer membrane

- GFB

glomerular filtration barrie

- mtROS

mitochondrial ROS

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- SDs

slit diaphragm proteins

- MMP-9

matrix metalloproteinase-9

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

- mtBax

mitochondria Bax

- DCFH-DA

2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- NAC

antioxidant N-acetylcysteine

- NDGA

nordihydroguaiaretic acid

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- MID51 and MID49

mitochondrial dynamics proteins of 51 and 49 kDa

- FIS1

mitochondrial fission protein 1

- MFF

mitochondrial fission protein

- PGC1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ co-activator 1α

- TFAM

mitochondrial transcription factor A

- NRF1 and NRF2

nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2

- ND1

NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1

- GBM

glomerular basement membrane

- DHE

dihydroethidium

- HE

hematoxylin-eosin

- PAS

periodic acid-schiff

- FBG

fasting blood glucose

- TG

triglyceride

- ACR

microalbumin-to-creatinine ratios

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- TLR4

toll-like receptor 4

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

- AKT

protein kinase B

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor-β

- AGEs

advanced glycation end products

- RAGE

receptor of advanced glycation end products.

References

- 1.Chan DC. Fusion and fission: interlinked processes critical for mitochondrial health. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:265–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilokani L, Nagashima S, Paupe V. et al. Mitochondrial dynamics: overview of molecular mechanisms. Essays Biochem. 2018;62:341–60. doi: 10.1042/EBC20170104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shirihai OS, Song M, Dorn GW 2nd. How mitochondrial dynamism orchestrates mitophagy. Circ Res. 2015;116:1835–49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.306374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youle RJ, van der Bliek AM. Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science. 2012;337:1062–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1219855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smirnova E, Griparic L, Shurland DL. et al. Dynamin-related protein Drp1 is required for mitochondrial division in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2245–56. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu C, Huang Y, Li L. Drp1-Dependent Mitochondrial Fission Plays Critical Roles in Physiological and Pathological Progresses in Mammals. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:18010144. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michalska B, Duszynski J, Szymanski J. [Mechanism of mitochondrial fission - structure and function of Drp1 protein] Postepy Biochem. 2016;62:127–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estaquier J, Arnoult D. Inhibiting Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission selectively prevents the release of cytochrome c during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1086–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayanga BA, Badal SS, Wang Y. et al. Dynamin-Related Protein 1 Deficiency Improves Mitochondrial Fitness and Protects against Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:2733–47. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015101096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galvan DL, Green NH, Danesh FR. The hallmarks of mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017;92:1051–7. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagata M. Podocyte injury and its consequences. Kidney Int. 2016;89:1221–30. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin JS, Susztak K. Podocytes: the Weakest Link in Diabetic Kidney Disease? Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16:45. doi: 10.1007/s11892-016-0735-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhargava P, Schnellmann RG. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:629–46. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fakhruddin S, Alanazi W, Jackson KE. Diabetes-Induced Reactive Oxygen Species: Mechanism of Their Generation and Role in Renal Injury. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:8379327. doi: 10.1155/2017/8379327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Susztak K, Raff AC, Schiffer M. et al. Glucose-induced reactive oxygen species cause apoptosis of podocytes and podocyte depletion at the onset of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2006;55:225–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forbes JM, Coughlan MT, Cooper ME. Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:1446–54. doi: 10.2337/db08-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindblom R, Higgins G, Coughlan M. et al. Targeting Mitochondria and Reactive Oxygen Species-Driven Pathogenesis in Diabetic Nephropathy. Rev Diabet Stud. 2015;12:134–56. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2015.12.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu L, Parhofer KG. Diabetic dyslipidemia. Metabolism. 2014;63:1469–79. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richieri GV, Kleinfeld AM. Unbound free fatty acid levels in human serum. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:229–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van der Vusse GJ, Roemen TH. Gradient of fatty acids from blood plasma to skeletal muscle in dogs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1995;78:1839–43. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.5.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuzefovych L, Wilson G, Rachek L. Different effects of oleate vs. palmitate on mitochondrial function, apoptosis, and insulin signaling in L6 skeletal muscle cells: role of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E1096–105. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00238.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sieber J, Jehle AW. Free Fatty acids and their metabolism affect function and survival of podocytes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:186. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badal SS, Danesh FR. New insights into molecular mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:S63–83. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pang B, Zhao LH, Zhou Q. et al. Application of berberine on treating type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:905749. doi: 10.1155/2015/905749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Tong Q, Shou JW. et al. Gut Microbiota-Mediated Personalized Treatment of Hyperlipidemia Using Berberine. Theranostics. 2017;7:2443–51. doi: 10.7150/thno.18290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pirillo A, Catapano AL. Berberine, a plant alkaloid with lipid- and glucose-lowering properties: From in vitro evidence to clinical studies. Atherosclerosis. 2015;243:449–61. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B, Xu X, He X. et al. Berberine Improved Aldo-Induced Podocyte Injury via Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Pathways both In Vivo and In Vitro. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39:217–28. doi: 10.1159/000445618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mundel P, Heid HW, Mundel TM. et al. Synaptopodin: an actin-associated protein in telencephalic dendrites and renal podocytes. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:193–204. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jentzsch AM, Bachmann H, Furst P. et al. Improved analysis of malondialdehyde in human body fluids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:251–6. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo JD, Wang YY, Fu WL. et al. Gene therapy of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and manganese superoxide dismutase restores delayed wound healing in type 1 diabetic mice. Circulation. 2004;110:2484–93. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137969.87365.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park KS, Wiederkehr A, Kirkpatrick C. et al. Selective actions of mitochondrial fission/fusion genes on metabolism-secretion coupling in insulin-releasing cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33347–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806251200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toyama EQ, Herzig S, Courchet J. et al. Metabolism. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates mitochondrial fission in response to energy stress. Science. 2016;351:275–81. doi: 10.1126/science.aab4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valente AJ, Maddalena LA, Robb EL. et al. A simple ImageJ macro tool for analyzing mitochondrial network morphology in mammalian cell culture. Acta Histochem. 2017;119:315–26. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Picard M, White K, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial morphology, topology, and membrane interactions in skeletal muscle: a quantitative three-dimensional electron microscopy study. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013;114:161–71. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01096.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He L, Chinnery PF, Durham SE. et al. Detection and quantification of mitochondrial DNA deletions in individual cells by real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e68. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong Y, Chen YT, Yang YX. et al. Metabolomics Study of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and the AntiDiabetic Effect of Berberine in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats Using Uplc-ESI-Hdms. Phytother Res. 2016;30:823–8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou J, Zhou S. Berberine regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and positive transcription elongation factor b expression in diabetic adipocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;649:390–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lan J, Zhao Y, Dong F. et al. Meta-analysis of the effect and safety of berberine in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipemia and hypertension. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;161:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katsuya K, Yaoita E, Yoshida Y. et al. An improved method for primary culture of rat podocytes. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2101–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu L, Fu W, Xu J. et al. Effect of BMP7 on podocyte transdifferentiation and Smad7 expression induced by hyperglycemia. Clin Nephrol. 2015;84:95–9. doi: 10.5414/CN108569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li SY, Huang PH, Yang AH. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 deficiency attenuates diabetic nephropathy by modulation of podocyte functions and dedifferentiation. Kidney Int. 2014;86:358–69. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prokhorova EA, Zamaraev AV, Kopeina GS. et al. Role of the nucleus in apoptosis: signaling and execution. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:4593–612. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2031-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin Y, Liu S, Ma Q. et al. Berberine enhances the AMPK activation and autophagy and mitigates high glucose-induced apoptosis of mouse podocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;794:106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rushworth GF, Megson IL. Existing and potential therapeutic uses for N-acetylcysteine: the need for conversion to intracellular glutathione for antioxidant benefits. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;141:150–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang SG, Park HJ, Kim JW. et al. Mito-TEMPO improves development competence by reducing superoxide in preimplantation porcine embryos. Sci Rep. 2018;8:10130. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28497-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arteaga S, Andrade-Cetto A, Cardenas R. Larrea tridentata (Creosote bush), an abundant plant of Mexican and US-American deserts and its metabolite nordihydroguaiaretic acid. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;98:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kong Y, Trabucco SE, Zhang H. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and the mitochondria theory of aging. Interdiscip Top Gerontol. 2014;39:86–107. doi: 10.1159/000358901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loson OC, Song Z, Chen H. et al. Fis1, Mff, MiD49, and MiD51 mediate Drp1 recruitment in mitochondrial fission. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:659–67. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gleyzer N, Vercauteren K, Scarpulla RC. Control of mitochondrial transcription specificity factors (TFB1M and TFB2M) by nuclear respiratory factors (NRF-1 and NRF-2) and PGC-1 family coactivators. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1354–66. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1354-1366.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villena JA. New insights into PGC-1 coactivators: redefining their role in the regulation of mitochondrial function and beyond. Febs j. 2015;282:647–72. doi: 10.1111/febs.13175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang W, Wang Y, Long J. et al. Mitochondrial fission triggered by hyperglycemia is mediated by ROCK1 activation in podocytes and endothelial cells. Cell Metab. 2012;15:186–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang CR, Blackstone C. Dynamic regulation of mitochondrial fission through modification of the dynamin-related protein Drp1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1201:34–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alhaider AA, Korashy HM, Sayed-Ahmed MM. et al. Metformin attenuates streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats through modulation of oxidative stress genes expression. Chem Biol Interact. 2011;192:233–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pedraza-Chaverri J, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Osorio-Alonso H. et al. New Pathogenic Concepts and Therapeutic Approaches to Oxidative Stress in Chronic Kidney Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:6043601. doi: 10.1155/2016/6043601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chacko BK, Reily C, Srivastava A. et al. Prevention of diabetic nephropathy in Ins2(+/)(-)(AkitaJ) mice by the mitochondria-targeted therapy MitoQ. Biochem J. 2010;432:9–19. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hou Y, Li S, Wu M. et al. Mitochondria-targeted peptide SS-31 attenuates renal injury via an antioxidant effect in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310:F547–59. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00574.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qi H, Casalena G, Shi S. et al. Glomerular Endothelial Mitochondrial Dysfunction Is Essential and Characteristic of Diabetic Kidney Disease Susceptibility. Diabetes. 2017;66:763–78. doi: 10.2337/db16-0695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang S, Han Y, Liu J. et al. Mitochondria: A Novel Therapeutic Target in Diabetic Nephropathy. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24:3185–202. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170509121003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ni WJ, Ding HH, Tang LQ. Berberine as a promising anti-diabetic nephropathy drug: An analysis of its effects and mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;760:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu L, Han J, Yuan R. et al. Berberine ameliorates diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway. Biol Res. 2018;51:9. doi: 10.1186/s40659-018-0157-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang YY, Tang LQ, Wei W. Berberine attenuates podocytes injury caused by exosomes derived from high glucose-induced mesangial cells through TGFbeta1-PI3K/AKT pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;824:185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu F, Yao DS, Lan TY. et al. Berberine prevents the apoptosis of mouse podocytes induced by TRAF5 overexpression by suppressing NF-kappaB activation. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:555–63. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li Z, Zhang W. Protective effect of berberine on renal fibrosis caused by diabetic nephropathy. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:1055–62. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qiu YY, Tang LQ, Wei W. Berberine exerts renoprotective effects by regulating the AGEs-RAGE signaling pathway in mesangial cells during diabetic nephropathy. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;443:89–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang X, He H, Liang D. et al. Protective Effects of Berberine on Renal Injury in Streptozotocin (STZ)-Induced Diabetic Mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1327. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang G, Zhao Z, Zhang X. et al. Effect of berberine on the renal tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by inhibition of the Notch/snail pathway in diabetic nephropathy model KKAy mice. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:1065–79. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S124971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Y, Li X, Zou D. et al. Treatment of type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia with the natural plant alkaloid berberine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2559–65. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang H, Wei J, Xue R. et al. Berberine lowers blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients through increasing insulin receptor expression. Metabolism. 2010;59:285–92. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gu Y, Zhang Y, Shi X. et al. Effect of traditional Chinese medicine berberine on type 2 diabetes based on comprehensive metabonomics. Talanta. 2010;81:766–72. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.