Abstract

Inspired by the period-four oscillation in flash-induced oxygen evolution of photosystem II discovered by Joliot in 1969, Kok performed additional experiments and proposed a five-state kinetic model for photosynthetic oxygen evolution, known as Kok’s S-state clock or cycle1,2. The model comprises four (meta)stable intermediates (S0, S1, S2 and S3) and one transient S4 state, which precedes dioxygen formation occurring in a concerted reaction from two water-derived oxygens bound at an oxo-bridged tetra manganese calcium (Mn4CaO5) cluster in the oxygen-evolving complex3–7. This reaction is coupled to the two-step reduction and protonation of the mobile plastoquinone QB at the acceptor side of PSII. Here, using serial femtosecond X-ray crystallography and simultaneous X-ray emission spectroscopy with multi-flash visible laser excitation at room temperature, we visualize all (meta)stable states of Kok’s cycle as high-resolution structures (2.04–2.08 Å). In addition, we report structures of two transient states at 150 and 400 μs, revealing notable structural changes including the binding of one additional ‘water’, Ox, during the S2→S3 state transition. Our results suggest that one water ligand to calcium (W3) is directly involved in substrate delivery. The binding of the additional oxygen Ox in the S3 state between Ca and Mn1 supports O–O bond formation mechanisms involving O5 as one substrate, where Ox is either the other substrate oxygen or is perfectly positioned to refill the O5 position during O2 release. Thus, our results exclude peroxo-bond formation in the S3 state, and the nucleophilic attack of W3 onto W2 is unlikely.

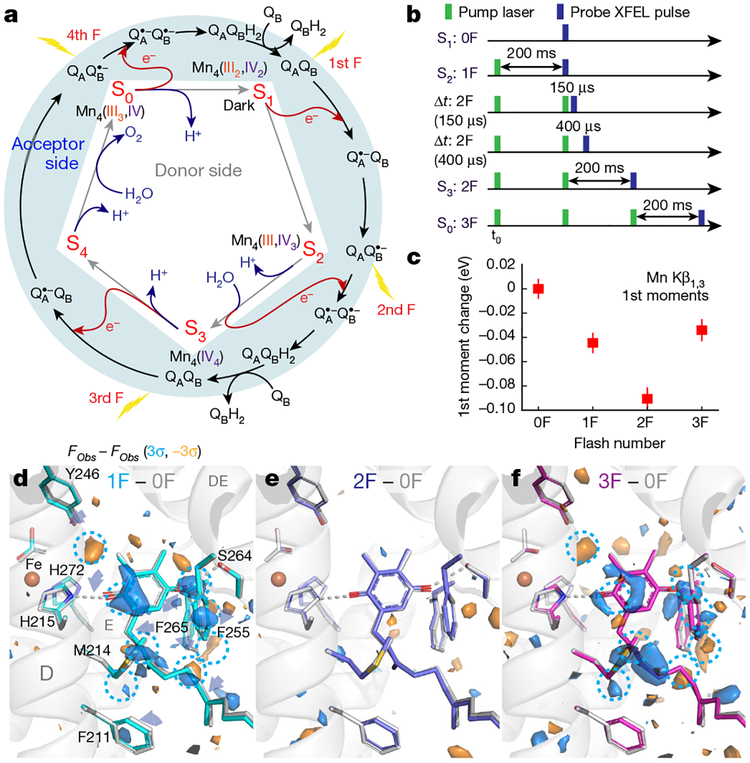

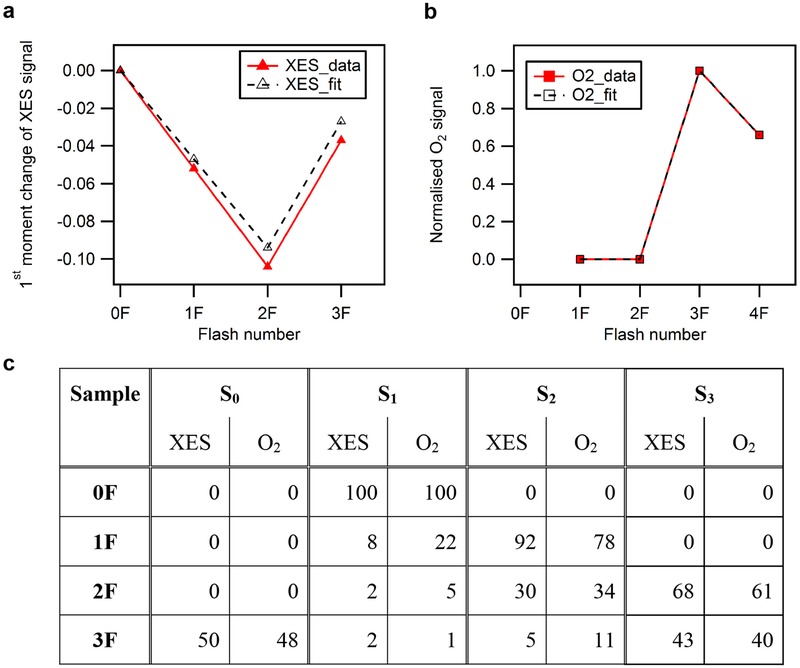

All four (meta)stable S-states of photosystem II (PSII) (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1a) were populated by illumination of dark-adapted PSII crystals with 0, 1, 2 or 3 flashes (0F–3F; Fig. 1b). The approximately 2 Å resolution (Extended Data Fig. 1b–e, Extended Data Table 1) was sufficient for determining the positions of the oxygens bridging the metal atoms, in addition to the terminal water positions of the Mn4CaO5 cluster; the former are critical for discriminating between proposed structures of the S-states, which was not possible in previous structures8,9. Reliable determination of the S-state composition of the PSII crystals obtained by each flash is essential for correct analysis of higher S-state structures. We therefore collected the Mn Kβ1,3 emission spectra in situ (see Methods)10, simultaneously with diffraction data. The first moment of the Kβl,3 peak shifts towards lower energy in response to the first two flashes (0F→1F→2F) and to higher energy in the 3F sample (Fig. 1c), as expected from reported Mn redox states4,11–14 (Fig. 1a). These data, in combination with ex situ O2 evolution measurements, were used to determine the S-state distribution in each illuminated state (see Methods, Extended Data Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 |. The oxygen-evolving cycle in photosystem II.

a, Relationship between the redox chemistry at the donor (Kok’s clock) and acceptor sides throughout the oxygen-evolving cycle. b, Relative timing of the visible laser (527 nm) pump and X-ray laser for the different illuminated states. c, First moment change of the Mn Kβ1,3 XES spectra from PSII crystals obtained in situ simultaneously with XRD. Data shown as mean ± s.d. (see Methods). D–f, Fobs − Fobs isomorphous difference maps around plastoquinone QB contoured at +3σ (blue) and −3σ (orange) for the 1F, 2Fand 3F states relative to 0F. The 0F stick model is shown in light grey; other models have carbons coloured cyan (1F), blue (2F) and magenta (3F).

Isomorphous difference maps (Fobs − Fobs) between the dark and flash-illuminated states at the acceptor side (Fig. 1d–f) indicate a clear period-two oscillation of QB between its fully oxidized (0F, 2F) and semiquinone QB•− (1F) forms. A decrease in the B-factor of the QB site after 1F suggests that the quinone in the 1F sample is more tightly bound, owing to the formation of the semiquinone QB•−. The observation of QB•− in the 3F data implies that three electrons were successfully transferred from the Mn4CaO5 cluster to the acceptor side, confirming S-state advancement in both PSII monomers (A and a; Fig. 1d–f, Extended Data Fig. 3).

In the S1 state, the cluster is in a distinct ‘right-open’ structure with no bond between Mn1 and O5; the Mn4–O5 distance is about 2.2 Å, whereas the Mn1–O5 distance is about 2.7 Å (Fig. 2; Extended Data Table 2), with Mn1 clearly pentacoordinate, and likely to be in the +3 oxidation state4,11,13–17. Open, non-cubane structures have been suggested by solution and single-crystal polarized extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) data4,11,15,18.

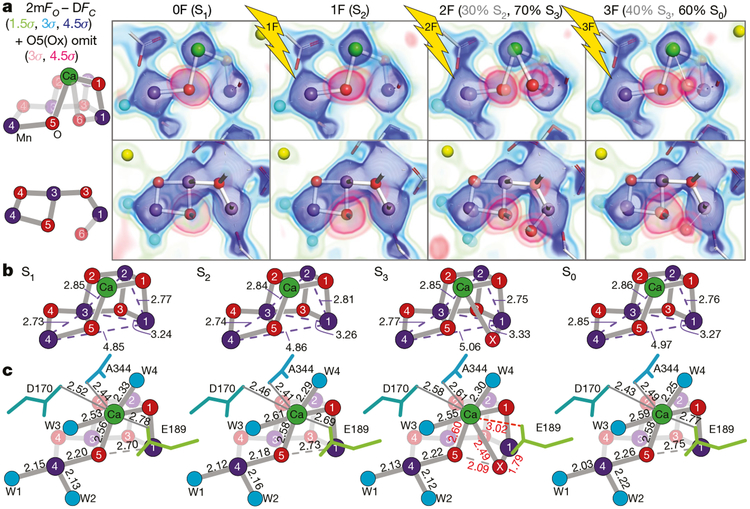

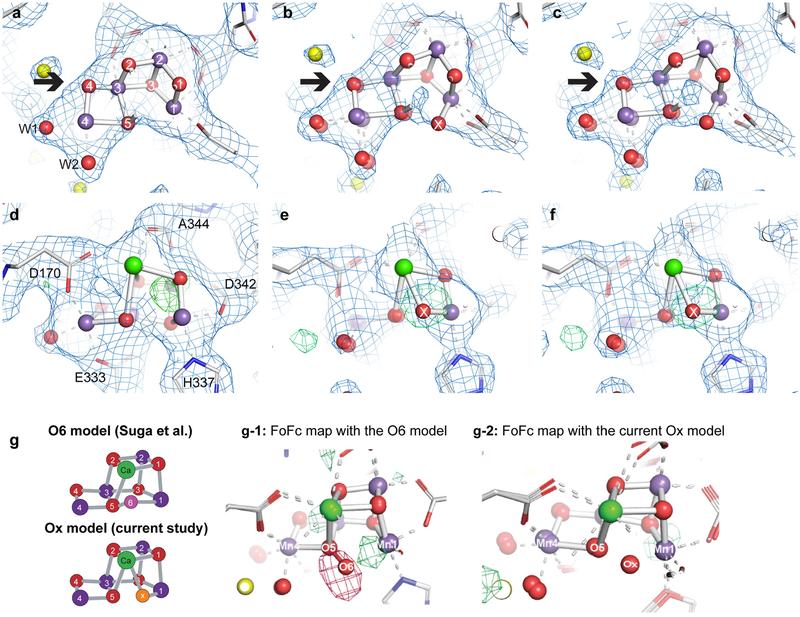

Fig. 2 |. Stepwise changes at the OEC during the oxygen-evolving Kok cycle.

a, Left, labelled diagrams of the OEC atoms in two views. Right, 2mFobs − DFcalc density (green to blue) and O5/Ox omit map density (pink) shown as the overlay of several contour levels for the two views of the OEC in the 0F-3F states. The contributions of the S states to each data set for the two-component analysis are indicated in parentheses. b, c, Atomic distances in the OEC in each S state in ångström, averaged across both monomers. Standard deviations for metal-metal, metal-bridging oxygen and metal-ligand distances are 0.1, 0.15 and 0.17 Å, respectively (see Methods). Ca remains 8-coordinate upon insertion of Ox by detaching D1-Glu189.

Upon the transition from S1 to S2 (1F), one Mn is oxidized from +3 to +4. Figure 2a shows the electron density map (2mFobs − DFcalc) of the dark (S1) and 1F (predominantly S2) states. The structure of the cluster in the S2 state remains fundamentally unchanged, with the coordination numbers of all the metals preserved and in accordance with the similarity of the S1 and S2 EXAFS spectra4. This ‘right-open’ geometry is consistent with models of the S2 low spin (Stotal = 1/2) configuration19, in which Mn4 is +4. There is no indication of a ‘left-open’ structure with an O5-Mn1 bond20. Only small structural changes are observed in the Fobs − Fobs difference map in the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) region, with shifts of Ca, Mn3 and Mn2 and of residues Asp170 from subunit D1 and Glu354 from subunit CP43 of PS II (Extended Data Fig. 4). Notably, the strongest difference is observed in the secondary coordination environment: a large negative peak at the location of water W20 (see below).

In Fig. 2a we evaluated the O5 position by overlaying the omit map on the 2mFobs − DFcalc map. In the 0F and 1F data, only one envelope of density is observed. Upon transition from S2 to S3 (2F), an additional feature appears near Mn1 that can be assigned to an inserted O atom (hydroxo or oxo). In the 2mFobs − DFcalc map of the 2F data, this additional density is visible as a small but distinct bulge that overlaps with the dominant Mn1 density (Extended Data Fig. 5). The presence of this additional density is distinguishable only in the omit map and in the 2mFobs − DFcalc map at high resolution, and not in the earlier 2.25 Å resolution map8 (Extended Data Fig. 5).

We refined the 2F data against two partial-occupancy models at the catalytic site based on the S-state populations (see Methods). The S2-state structure, which is the refined structure for 1F, was fixed at 30% in the 2F state. The 2F data were then used to refine the S3-state structure at 70% occupancy. In the refined S3 structure, the Mn1-Mn4 and Mn1-Mn3 distances are elongated by about 0.2 and 0.07 Å, respectively, relative to the S2 structure, and the newly inserted hydroxide or oxo (Ox in Fig. 2a, b), located about 1.8 Å from Mn1, occupies its sixth coordination site. This change in coordination of Mn1 from 5- to 6-coordinate is in line with the proposed oxidation of Mn1 from +3 to +4 in the S2→S3 transition21–23. Ox is also bound to Ca (2.50 Å) and it is closer to Ca than is O5 (2.60 Å). The Ca coordination number, however, remains eight, as D1-Glu189, which was ligated to Ca in the S1 and S2 states (at 2.78 and 2.69 Å, respectively), moves away from Ca in the S3 state (3.01 Å), making space for Ox (Fig. 2c). These movements are accompanied by changes in the positions of nearby residues (His332, Glu333, His337, Asp342, Ala344, Asp170 of D1, and Glu354, Arg357 of CP43; Extended Data Fig. 4). We note that the current data cannot tell us whether Ox is oxo or hydroxo. However, the position of Ox is compatible with a deprotonated oxo bridge17.

Suga et al.9 recently reported insertion of an O6 atom at 1.5 Å from O5 in their 2F sample (ex situ estimation 46% S3 state) based on a 2F − 0F difference map at 2.35 Å resolution and proposed formation of a peroxide bond between O5 and O6 in the S3 state. The O5-Ox distance of 2.1 Å in our data is about 0.6 Å longer than the O5-O6 bond modelled by Suga et al.9, and the location of Ox is 0.9–1.0 Å away from O6. Thus, our data do not agree with the formation of a peroxide-like bond in the S3 state. We also note that if a peroxide-like bond were to form in the S3 state, it would have to be accompanied by reduction of Mn, which conflicts with various spectroscopic observations4,15,21 including our current in situ X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) data (Fig. 1c), which show oxidation of Mn upon the S2→S3 transition. We conclude that the differences in interpretation of the data between Suga et al.9 and Young et al.8 arose from uncertainty when determining oxygen positions at approximately 2.3 Å resolution, whereas our current data clearly show that Ox is bound to Mn1 and Ca, and that there is no peroxo-bond formation with O5 in the S3 state.

The third laser flash (3F) advances the highest-oxidized metastable S3 state to the most reduced S0 state by releasing O2 and acquiring one water molecule, resetting the catalytic cycle of Kok’s clock. The S0 structure shows the loss of Ox and the return to a motif similar to the dark stable S1 state (Fig. 2b, c). The decrease in density for Ox in the 3F state (Fig. 2a) is in line with the 60% S0 population (see Methods).

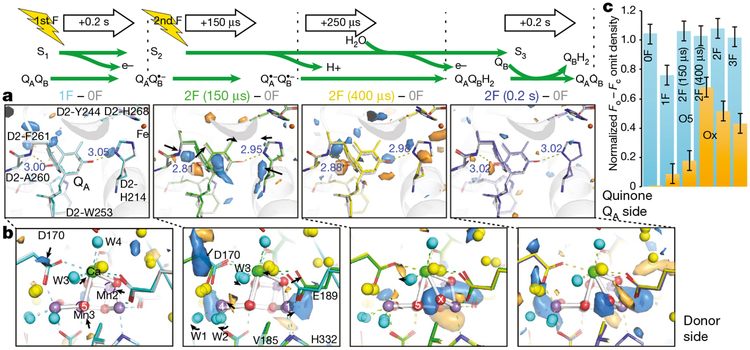

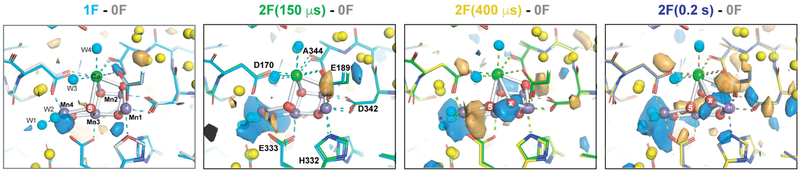

We collected data sets from two transient states at time points during the S2→S3 transition, 150 and 400 μs after the second flash (Fig. 1b), with resolutions of 2.5 and 2.2 Å, respectively, and computed Fobs − Fobs maps with the 0F data (Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 6, Supplementary Video 1). At the acceptor side, prominent difference peaks are visible in the vicinity of the primary quinone acceptor, QA (Fig. 3a), resembling the differences observed at the QB site upon formation of QB•− 0.2 s after the first flash (Fig. 1d) and indicating formation of the reduced QA•− semiquinone. The same features are visible 250 μs later in the 2F(400 μs) − 0F difference map, but at reduced intensity. By contrast, the corresponding Fobs − Fobs difference maps for the data sets collected 0.2 s after the first and second flashes do not show any indication of QA•− formation, following known kinetics for QA•− formation (submicrosecond) and decay (on the order of hundreds of microseconds)24.

Fig. 3 |. The S2→S3 transition in PSII.

a, b, Isomorphous difference density at quinone QA (a) and donor side (b) with the expected reduced state of QA at 2F (150 μs) and less pronounced at 2F (400 μs), and the oxidation of the OEC and insertion of Ox by 400 μs after the second flash. Fobs − Fobs difference densities between the various illuminated states and the 0F data are contoured at +3σ (blue) and −3σ (orange). The model for the 0F data is shown in light grey whereas carbons are coloured in the models as follows: 1F (cyan), 2F (150 μs) (green), 2F (400 μs) (yellow) and 2F (0.2 s) (blue). c, Estimates of occupancies of O5 and Ox based on omit map peak heights normalized against the average electron density maximum at the O2 position in the omit maps. These match full occupancy of O5 throughout and Ox insertion by 400 μs after the second flash. Data shown as mean ± s.d. based on the electron density value at the O2 position (n = 12 observations, see Methods).

At the OEC, the 2F (150 μs) − 0F Fobs − Fobs map shows that the first event after the absorption of the second photon is a movement of Mn4 and Mn1 away from each other by about 0.2 Å (Fig. 3b). Density at the Ox site becomes visible in the 2F (400 μs) − 0F Fobs − Fobs map as well as in the 2mFobs − DFcalc map, indicating the ligation of Ox to the Mn1 open coordination site. The Ox density (shown in Fig. 3c with the O5 density) increases substantially at 400 μs, and decreases in the 3F data. The remaining Ox density in the 3F data is explained by the approximately 40% S3 fraction.

It has been suggested that the S2→S3 transition involves a proton transfer followed by an electron transfer7,25. We hypothesize that the proton transfer triggers the shifts of the Mn4 and Mn1 positions in the early stage of the S2→S3 transition, including shifts of water positions (see below). One option is that W1 deprotonates, while W3 transfers a proton to O5, weakening the O–Mn interaction and allowing the elongation of Mn1 and Mn426 that is necessary for subsequent oxygen insertion at Mn1, which is coupled to a proton transfer from O5 to W1. D1-Tyr161 (YZ) is located about 4 Å from D1-Glu189. The formation of the positive charge at Yz/His189 that precedes oxidation of the OEC could trigger these structural changes in its surrounding, inducing a shift of D1-Glu189 away from Ca as observed in the 2F (150 μs) data. The subsequent oxidation of Mn1 appears to be directly coupled to the insertion of Ox at the Mn1 open-coordination site observed in the 2F (400 μs) data (Fig. 3b, c). We do not observe the formation of a ‘left-open’ structure that has been proposed on the basis of DFT-based studies for the early stage of the S2→S3 transition20.

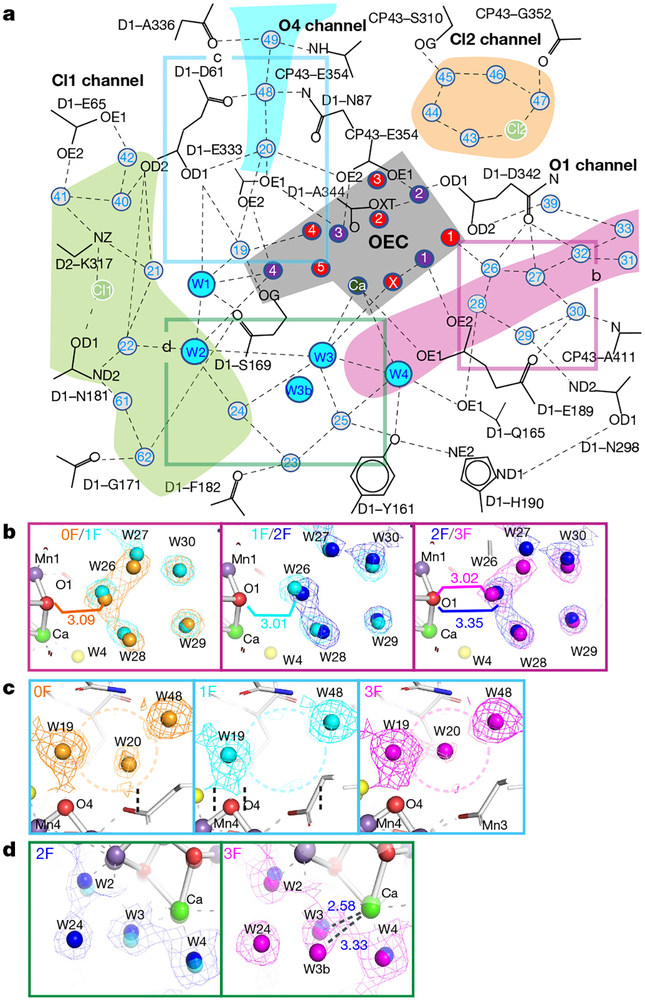

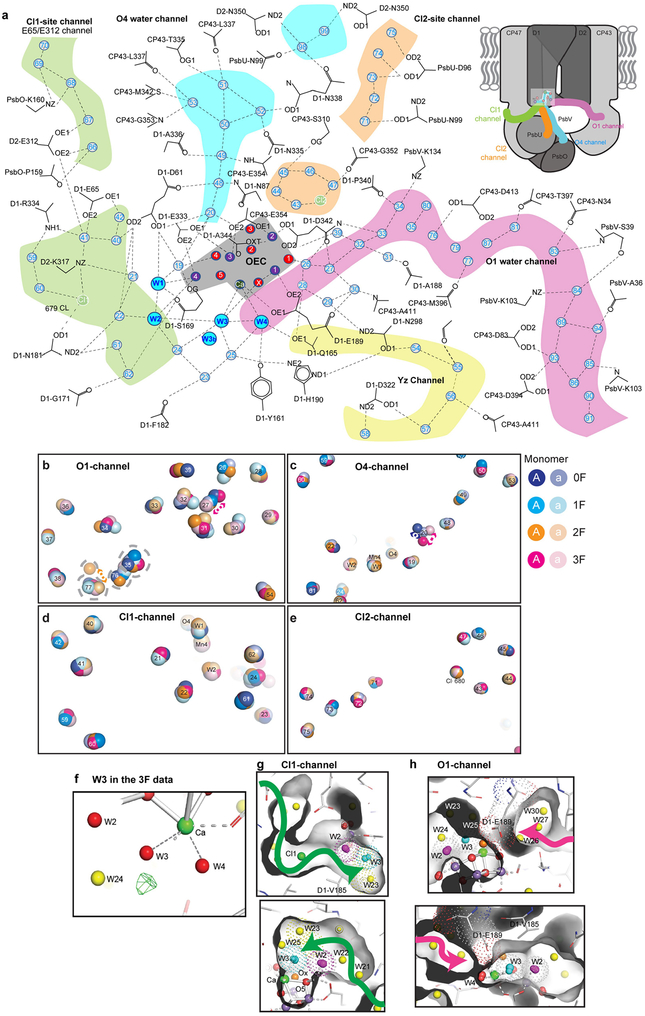

The OEC is embedded in an extended network of H bonds between amino acid residues and waters, which connects it to bulk water and is essential for its function (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 7, Extended Data Table 3). We observe several substantial changes in this network during the S-state cycle. Movements of the H-bonded water molecules W26–30 (Fig. 4b), of which W26 is located close to O1, indicate that these may be part of a H2O/H+ transfer pathway or take part in charge redistributions within the Mn4CaO5 cluster during the S-state cycle. W20 is lost in the S1→S2 transition and reappears during the S3→S0 transition (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 7, Supplementary Video 2), suggesting that the O4 channel may be used for proton release in the S0→S1 transition but not in the S2→S3 and S3→S0 transitions. Suga et al.9 did not report S2-state data, but observed the loss of this water in the 2F data and related it to water insertion during S3-state formation, which was further reinforced by the proposed computational ‘pivot’ or ‘carousel’ mechanisms involving the Mn4 site20,27. However, as this water is already absent in S2, its loss may not have a direct relationship to the formation of S3.

Fig. 4 |. Water network around the OEC.

a, Schematic of the H-bonding network surrounding the OEC indicating starting points of channels connecting the OEC to the solvent-exposed surface of PSII for possible water movement and proton transfer. b–d, Changes in selected water positions between the 0F and 3F states overlaid with 2mFobs − DFcalc maps in those states contoured at 1.5σ. Positions in the schematic view are indicated by boxes of the same colour. Selected distances are given in ångström. b, Oscillation of the cluster of five waters next to O1 with the O1-O26 distance alternating long-short-long-short from 0F – 3F. c, W20 and its direct surroundings, indicating disappearance of W20 in the 1F (S2) data and reappearance in 3F (S0). d, Environment of Ca-bound W3, indicating the presence of a second water position for W3 in the S0 state (3F).

Additional water positions are observed near the Ca-bound W3 in the S0 structure: W3b at 3.25 Å to Ca has approximately 60% occupancy in monomer A (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 7), while the Ca-bound W3 is at 2.59 Å (approximately 40%). In monomer a, a smaller but similar positive peak is observed in the mFobs − DFcalc map. Therefore, we hypothesize that W3 is the entrance site for the water, which is incorporated into the OEC during the S3→S0 transition. As indicated by the changes in the Ca ligation environment, W3 may play a similar role in the S2→S3 transition. We therefore suggest that water at the W3 position may act as the entrance site or ‘parking place’ for either the substrate or the next substrate water in the S2→S3 and S3→S0 transitions, in agreement with earlier suggestions5,25,28–30. Possible access routes of water molecules to W3 are shown in Extended Data Fig. 7 (see also Fig. 4a).

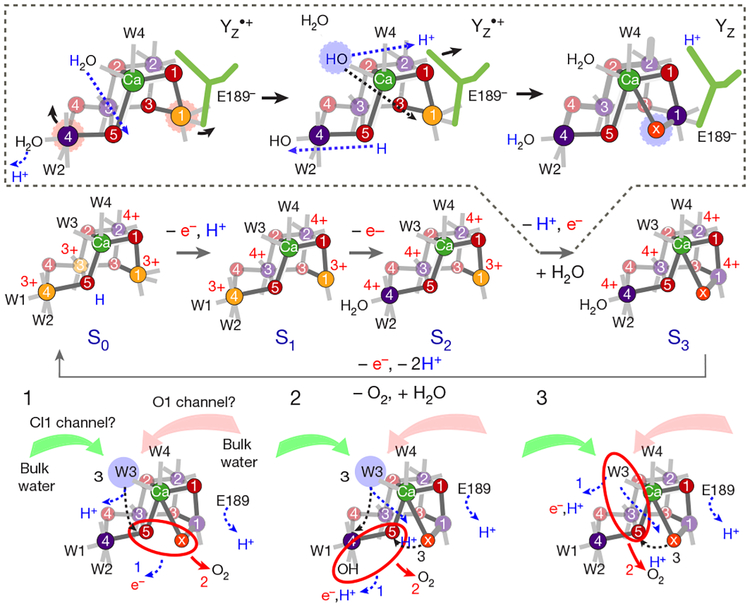

Figure 5 summarizes the structures we determined for all of Kok’s S-states and our interpretation of the S-state-dependent changes with regard to the mechanism of water oxidation. As outlined above, we propose that the Ox site is filled by W3 during the S2→S3 transition. The presence of Ox at Mn1, 2.1 Å from O5, suggests that Ox either forms the O–O bond with O5 in the S3→S0 transition (case 1 in Fig. 5), or that Ox is placed between Ca and Mn1 to replace O5 during O2 formation or release. In the latter case, O–O bond formation may occur between O5 and W2 (2) or O5 and W3 (3). We exclude a nucleophilic attack mechanism of W3 or a protein-bound water molecule on W2 or W1, as the basis for these suggestions was that the Mn3CaO4 cubane of the Mn4CaO5 cluster acts as a ‘battery’ by storing oxidizing equivalents, but remains structurally unmodified in a closed cubane geometry31. This is in contrast to our data that show intricate structural changes in an open cubane involving ligand detachment and the formation of a new Ca-Ox-Mn1 bridge.

Fig. 5 |. Schematic structures of the S states in the Kok cycle of PSII and proposed reaction sequences for O–O bond formation in the S4 state.

The likely position of Mn oxidation states (Mn3+ is depicted in orange, Mn4+ in purple) as well as protonation and deprotonation reactions are indicated for each S state; the proposed steps in the S2→S3 transition, including Ox insertion, are indicated in the dashed box with blue dashed arrows signifying atom movements. Three likely options (1, 2 and 3) for the final S3→S0 transition are given in the bottom part, including possible order of 1) electron and proton release; 2) O–O bond formation and O2 release; and 3) refilling of the empty substrate site.

METHODS

Sample preparation.

PSII dimers were extracted and purified from Thermosynechococcus elongatus as reported previously32. PSII crystals ranging in size from 20 to 60 μm were then prepared using a modified seeding protocol33 The crystals were dehydrated by treatment with high concentrations of PEG 5000. The final crystal suspension used for XRD measurements was in 0.1 M MES pH 6.5, 0.1 M ammonium chloride and 35% (w/v) PEG 5000, with ~0.5–0.8 mM chlorophyll concentration. After loading into the sample delivery syringe (Hamilton gastight syringe, 1,000 μl), each sample syringe was given a preflash using green LED diodes (525 nm, Thorlabs, USA) to synchronize the samples, ensure that all centres have an oxidized tyrosine D and maximize yield of the higher S states upon subsequent flashing. The photon flux used at the sample for the preflash was 2 μmol m−2 s−1. The samples were exposed for ten seconds while rotating the syringe, and dark-adapted for 30 min to 2 h after the preflash. We note that the PSII core complexes in our sample preparation contain a sufficient number of natural quinones to drive the catalytic reaction through the cycle8,34,35.

Characterization.

O2 activity.

Measurement of the O2 yield by means of a Clark-type electrode under continuous illumination showed that the O2 evolution rate of PSII solution before crystallization was 2,300 ± 100 μmol O2/(mg(Chl) × h) and after crystallization in the final buffer comprising 0.1 M MES pH 6.5, 0.1 M ammonium chloride it was 2,100 ± 80 μmol O2/(mg(Chl) × h) with 0.4 mM PPBQ. Approximately 90% activity was retained after crystallization

EPR measurements.

All sample batches used at the LCLS were checked with EPR for S-state turnover and Mn(II) content. The low-temperature X-band EPR spectra were measured using a Varian E109 EPR spectrometer equipped with a Model 102 Microwave bridge. For the turnover measurements, sample temperature was maintained at 8 K using an Air Products LTR liquid helium cryostat. The following spectrometer conditions were used: microwave frequency, 9.22 GHz; field modulation amplitude, 32 G at 100 kHz; microwave power, 20 mW. The turnover in the crystals was characterized using EPR spectroscopy. The turnover of the samples was measured as a function of the multiline EPR signal of the S2 state, which oscillates with a period of four as a function of flash number. We observed the EPR signal for samples after a single turnover flash (1F) and monitored turnover by following decreases in amplitude of the multiline signal by subsequent flashes. In order to check the Mn(II) content, sample temperature was maintained at 20 K and the sensitivity of the measurement allowed to detect the presence of as low as 2% Mn(II) (compared to total Mn content) in the sample. The following spectrometer conditions were used: microwave frequency, 9.22 GHz; field modulation amplitude, 32 G at 100 kHz; microwave power, 1 mW The Mn (II) content estimated by EPR agreed with that determined by in situ XES measurements36.

Membrane inlet mass spectroscopy measurements.

The S-state advancement of crystals was also evaluated by membrane inlet mass spectroscopy (MIMS). A crystal suspension with approximately 10% 18O-labelled water was placed in the thin-layer MIMS setup and subjected to a laser preflash before dark adaptation for 40 min at room temperature. The sample was then subjected to 2F at 5 Hz frequency and the O2 yield was detected as a peak at m/z=34. The procedure was repeated for 3F and 4F using new crystal suspensions each time. The O2 yield pattern as function of flash number was calculated by subtracting the normalized O2 yield of a flash number with the yield from the preceding flash number and normalized to 3F. The O2 pattern can be fitted satisfactorily with an average miss parameter of 22%. The estimated S-state population is presented in Extended Data Fig. 2.

Determination of the S-state population.

We evaluated the S-state advancement of PSII crystal suspension by two methods, in situ and ex situ. X-ray emission spectroscopy, which monitors the oxidation state of Mn, was collected simultaneously with the XRD data (Fig. 1c) as described previously10,36,37. The obtained single crystal XES spectra and details about XES data evaluation have been published recently36. Standard deviations for the first moments of the XES data shown as error bars in Fig. 1c were determined by random sampling of each of the data sets 1,000 times (each time randomly splitting the data into two subsets) and then calculating the standard deviation from the resulting 2,000 spectra for each flash state38.

Flash-induced oxygen measurements using MIMS for O2 detection38–40 were carried out before the XFEL experiment. We estimated the S-state population from both methods and these are presented in Extended Data Fig. 2. For the purpose of refinement of the structural models in the 2F data, we fixed the S3 populations to 70% and S2 to 30%. For the 3F data, we fixed the S3 populations to 40%, and fit the remaining 60% as S0, because S0 is the major population within the 60%. Further details regarding the refinement of the mixed models in the 2F and 3F data are given below (Model building and map calculation).

Sample injection and illumination.

The crystallography data were collected at the MFX instrument of LCLS41,42 during experiments LN84 and LQ39. The drop-on-tape (DOT) sample delivery method was used in combination with acoustic droplet ejection (ADE)37. For capturing the stable intermediates S2, S3, and S0, each droplet of the crystal suspension was illuminated by 120-ns laser pulses at 527 nm using a Nd:YLF laser (Evolution, Coherent) via fibre-coupled outputs 1, 2 and/or 3 resulting in a delay time of 0.2 s between each illumination, and of 0.2 s between the last illumination and the X-ray probe37. We implemented a feedback control system of the belt speed and deposition delay, and the flashing delay and droplet phase were adjusted accordingly37.

For ex situ testing of light saturation for the DOT system, a 100–150 μm thick sample film was established with the help of a washer between the silicon membrane of the mass spectrometer inlet and a thin microscope glass plate (thin layer MIMS setup). In this experiment, the samples were saturated at 70 mJ/cm2. The details have been described8. At the XFEL, a light intensity of 120 ± 10 mJ/cm2 was applied.

X-ray diffraction setup and data processing.

PSII crystals were measured using X-ray pulses of ~40 fs length at 9.5 keV and with an X-ray spot size at the sample of ~3 μm in diameter. XRD data were collected on a Rayonix MX170 HS detector operating in the 2-by-2 binning mode at its maximum frame rate of 10 Hz. This mode provided the optimal trade-off of resolving power between adjacent Bragg reflections and quantity of images collected.

We developed the cctbx.xfel graphical user interface to track diffraction data acquisition, provide real-time feedback, and submit processing jobs. Processing jobs used dials.stills_process, a program within the cctbx.xfel framework that carries out lattice indexing, crystal model refinement, and integration and adopts a variety of defaults suited to XFEL still images43–48. For each image, strong spots are first selected. Next, candidate basis vectors describing the lattice of strong spots are identified, and an optional target cell is used to filter these candidates. A crystal model (composed of a unit cell and crystal orientation) is then refined to minimize differences between observed spot centroids and predicted positions, and this model is used to generate a complete set of indexed positions on the frame. Finally, signal at these positions is integrated and any corrections or uncertainties are taken into account. We found that with the stills-specific defaults and very few non-default parameters, 20–50% of shots (which we estimate to be the majority of the shots containing crystals) could be successfully indexed.

The powder diffraction pattern of a silver(I) behenate sample (Alfa Aesar) in a quartz capillary (Hampton Research, 10 μm wall thickness) was used to obtain an initial estimate of detector distance. Initial indexing results were used to refine a detector distance and position for each interval between adjustments to the sample delivery system or detector position. These higher-precision detector positions were used in subsequent indexing and integration trials, resulting in a maximum of four distinct lattices indexed on a single shot.

Cluster.unit_cell, a command line tool in cctbx that clusters similar unit cells according to the Andrews-Bernstein distance metric49,50, was used to obtain the average unit cell. This unit cell was used as the target unit cell when reprocessing all experimental data with dials.stills_process.

A total of 1,565,863 integrated lattices were obtained using dials.stills_process with a target unit cell of a = 117.5 Å, b = 222.8 Å, c = 309.6 Å, α = β = γ = 90° and the space group P212121. Signal was integrated to the edges of the detector in anticipation of a per-image resolution cutoff during the merging step. Integrated intensities were corrected for absorption by the Kapton conveyor belt to match the position of the belt and crystals relative to the X-ray beam37.

Finally, XES data collected simultaneously with the diffraction images were used to sort out and exclude any sample batches that indicated the presence of Mn(II) released during the on-site crystallization36. It was also used to confirm the advancement of S states by fibre-coupled lasers and a free space laser.

Image sets were also culled to include only images diffracting beyond 6 Å (for small data sets) or beyond 3 Å (all others), similar to a procedure that has been used previously51 to improve statistics in large data sets suffering from contamination by low-quality images. Until the experiments described here, we were typically data-limited and have focused data processing methods development on discovering how to extract the most signal from low-multiplicity data sets52,53. Several data visualization tools we implemented in the cctbx.xfel graphical user interface have made it possible to tune crystallization conditions and the sample delivery system to optimize diffraction quality early in an XFEL diffraction experiment, resulting in collection of much larger quantities of data. Although post-refinement and the per-image resolution cut-offs used in cxi.merge downweigh or remove most spot predictions without signal, we still observed improvement in merging statistics and map quality when excluding lattices diffracting to a resolution poorer than 3 Å from these larger data sets, probably because of the limitation in orientational precision when indexing the small number of reflections visible on low-resolution stills.

The remaining integrated images were merged using cxi.merge as described previously8, with a couple of modifications. The default unit cell outlier rejection mechanism in cxi.merge was sufficiently selective on the image set curated as described above, so a pre-filtering step was not necessary. Also, a reference model and data set with a compatible unit cell—used by cxi.merge during scaling—were available from previous beam times, so a preliminary merging step with PRIME was not necessary.

Final merged data sets were acquired for the 0F, 1F, 2F (150 μs,) 2F (400 μs), 2F, and 3F states to resolutions between 2.50 and 2.04 Å, containing between 4,231 and 30,366 images (Extended Data Table 1). Additionally, data from all illuminated states were aggregated, culled to the subset of images extending past 2.2 Å, and merged as a separate ‘combined’ data set to 1.98 Å (results not shown).

Model building and map calculation.

Initial structure refinement against the ‘combined’ data set at 1.98 Å was carried out starting from a previously acquired high-resolution PSII structure in the same unit cell (PDB ID: 5TIS) using phenix. refine54,55. After an initial rigid body refinement step, xyz coordinates and isotropic B-factors were refined for tens of cycles with automatic water placement enabled. Custom bonding restraints were used for the OEC (with large sigma values, to reduce the effect of the strain at the OEC on the coordinate refinement), chlorophyll-a (CLA, to allow correct placement of the Mg relative to the plane of the porphyrin ring), and unknown lipid-like ligands (STE). Custom coordination restraints overrode van der Waals repulsion for coordinated chlorophyll Mg atoms, the non-haem iron, and the OEC. Following real space refinement in Coot56 of selected individual sidechains and the PsbO loop region and placement of additional water molecules, the model was refined for several additional cycles with occupancy refinement enabled, then as before without automatic water placement, and then as before with hydrogen atoms. NHQ flips and automatic linking were disabled throughout. A final ‘combined’ data set model was obtained with Rwork/Rfree of 17.92%/22.01%.

The above model was subsequently refined against the illuminated data sets to produce models that differed primarily at the OEC and plastoquinone, as confirmed by isomorphous difference maps, with the lattermost refinement settings and different OEC bonding restraints. OEC bonding restraints for the 0F data set prevented large deviations from the high-resolution dark state OEC structure reported by Suga et al. (PDB ID: 4UB6)53. Bonding restraints for the other data sets loosely restrained the models to metal-metal distances matching spectroscopic data and metal-oxygen distances matching the most likely proposed models57–61.

A number of ordered water positions were excluded from subsequent automatic water placement rounds by renaming the residue names to OOO and supplying Phenix with a bonding restraint CIF dictionary for OOO identical to that for HOH, and the waters coordinating the OEC were incorporated into the OEC restraint CIF file directly. After 12–15 of cycles of refinement in this manner, individual illuminated states at various resolutions were obtained ranging in Rwork/Rfree from 16.69%/24.60% to 19.33%/26.39% (Extended Data Table 1).

After the first cycles of refinement for the 2F data using the initial OEC model from the 0F data as starting point, a positive peak in the mFobs − DFcalc density close to Mn1 became visible (see also Extended Data Fig. 5) and the automatic water placement step in refinement placed a water at the OEC between O5 and Mn1. We designated this new water as a potential Ox and added it to the OEC. We tested several starting positions for this Ox, including a position similar to O6 (Suga et al.)9 at 1.5 Å from O5, but refinement resulted in shifts of the Ox away from O5 and close to Mn1. mFobs − DFcalc difference maps calculated for different positions of this additional oxygen also confirmed a placement at about 1.8 Å from Mn1 and 2.1 Å from O5. For the final refinement, Ox was included in the CIF restraints for the OEC in the S3 state.

To best approximate the contributions of dimers that did not advance to the next S state owing to illumination misses, for the 2F and 3F data sets, the 2F and 3F models were split into A and B alternate conformers in regions of chains A/a, C/c and D/d surrounding (and including) the OEC. These residues are A55–65, A160–190, A328–344, C328, C354–358 and D352. Population of the S3 and S0 states in the 2F and 3F data was estimated on the basis of oxygen evolution and XES measurements (Extended Data Fig. 2) and rounded to the nearest 10%, yielding 70% S3 state population in the 2F data set and 60% S0 state population in the 3F data set. Accordingly, for the 2F data set, the main conformer across this entire region was set at 0.7 occupancy, and the minor conformer was set at 0.3 occupancy. Analogously, for the 3F data set, conformers were set at 0.6 and 0.4 to match an estimated 40% contribution from the S3 state and modelling the remaining 60% as the S0 state. The major conformer was allowed to refine as usual, while the minor conformer was fixed during refinement and set to match the major conformer of the previous S state (for example, fixed coordinates for S2 at 30% for the 2F, S3-enriched state). This was achieved by least-squares fitting the refined model of the previous S state onto the new model at the split region in PyMol62 and replacing the minor conformer atomic coordinates with the fitted model coordinates, then excluding the newly placed atoms from refinement in phenix.

Although phenix.refine supports modelling of three or more conformers, we limited our analysis to two conformers in consideration of both the limits of the resolution and the precision of the S-state contribution estimates, and we did not model a ~10% contribution of the S1 state in the 1F data set. When placing the refined S3 state model into the 3F model at 0.4 occupancy, we used the 0.7 occupancy model refined as described above, not the combination of both conformers. This analysis was not possible for the 2F (150 μs) and 2F (400 μs) models because the complementary components would be time points 150 μs and 400 μs after the S1 state, structures we have not probed.

Estimated positional precision.

The maximum-likelihood coordinate error calculated during refinement is a general-purpose metric for positional error but is subject to several limitations, including the impact of bonding, angle, coordination and other restraints on the refined model. Previously, we have generated ballpark estimates of positional error for various sections of the model by setting them to zero occupancy, conducting simulated annealing followed by refinement, placing the same components into omit density, and reporting the final magnitude of the shift between the centres of mass of the original and omit density-fitted components8. This is impractical for more than a handful of representative cofactors or segments of the main chain and is difficult for much smaller groups of atoms or individual atoms whose environments easily fill the missing density region if it is not artificially held open. We also tried multi-start kicked model refinement and found that the OEC refined back to nearly the same position in all trials. We therefore shifted our focus to a tool that perturbs the structure factors directly. By perturbing structure factors by ± |Fobs − Fmodel| in 100 trials using the END/RAPID command line tools, we added noise proportional to the error in the model to generate 100 perturbed data sets for each illumination state, re-refined kicked models against each new data set, and calculated the mean and s.d. of selected bond distances across the re-refined models63. Metal-metal distancesat the OEC had standard deviations between 0.08 and 0.12 Å across these trials, while distances between OEC metals and bridging oxygen atoms had standard deviations varying between 0.10 and 0.23 Å and distances between OEC metals and coordinating ligands were found to have standard deviations between 0.13 and 0.20 Å.

Estimating the uncertainty of the omit densities.

Changes in the electron density at the positions of Ox and O5 were obtained from O5 and Ox omit maps and normalized against the average electron density maximum at the O2 position in O2 omit maps, assuming that O2 is always fully occupied in the different flash states. The standard deviation of the electron density value at O2 over all data sets and both monomers was also used to estimate the uncertainty of the normalized omit density. The omit densities of a particular data set were divided by the average omit densities of the chloride ions of the same data set to equate the densities from different data sets.

Isomorphous difference maps.

Slight, nonphysical differences in merged unit cells were modelled across the illumination states in this sequence of data sets. Large distributions of unit cells derived from indexing with dials.stills_processare known to reflect uncertainty in the crystal model, not variation among actual crystals64, and the distributions also shifted as sample-to-detector distance changed over the course of an LCLS shift. Because it was not possible to cycle through all illumination conditions throughout each of the experiments, the average unit cell dimensions varied across data sets as well, resulting in the aforementioned nonphysical differences in merged unit cells. To obtain isomorphous difference maps without artefacts from these apparent unit cell variations we computed a second set of data, selecting only lattices with unit cells within 1% of the target unit cell. The resulting smaller data sets were at slightly reduced resolution (Extended Data Table 1b). However, because the merged unit cell differences were small, artifact free isomorphous difference maps could be calculated between pairs of these data sets. The corresponding .mtz and .pdb files for these smaller data sets are available from the authors upon request.

Code availability.

The open source programs dials.stills_process, the cctbx.xfel GUI and cxi.merge are distributed with DIALS packages available at http://dials. github.io, with further documentation available at http://cci.lbl.gov/xfel.

Reporting summary.

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the following accession codes: 6DHE for the 0F, 6DHF for the 1F, 6DHO for the 2F, 6DHG for the 2F(150μs), 6DHH for the 2F(400μs) and 6DHP for the 3F data.

Extended Data

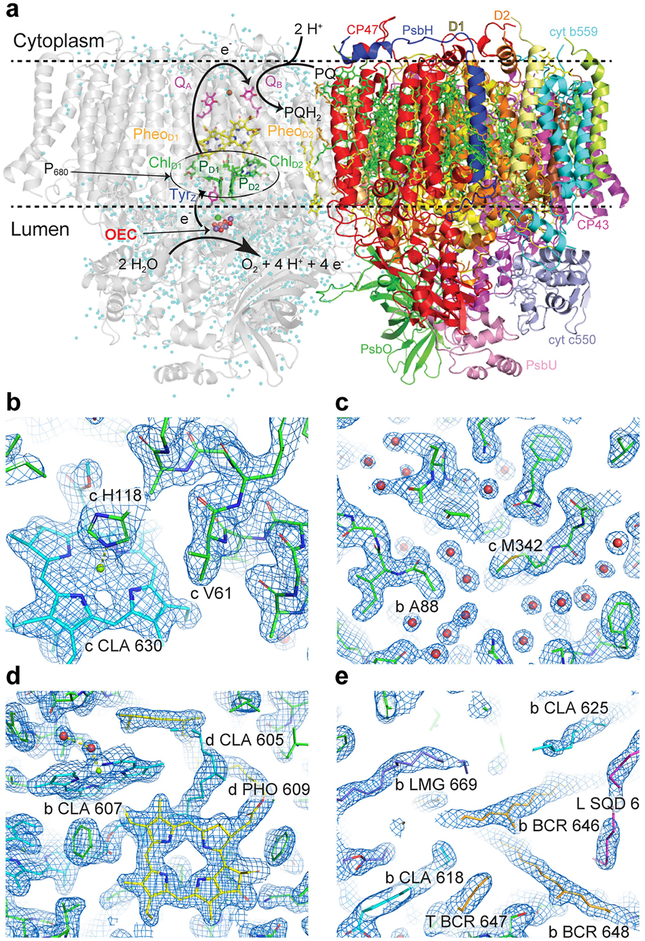

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Overview of the PSII structure and electron density maps of the 3F state.

a, Structure of the native PSII homodimer. In the left monomer the location of cofactors for the initial charge separation (P680, PheoD1), and for the electron transfer leading to the reduction of the plastoquinone (QA, QB) at the acceptor side and to the oxidation of the OEC at the donor side by P680+ are indicated. In the right monomer, the locations of the protein subunits are displayed. b–d, 2mFobs − DFcalc map (blue, 1.5σ contour) obtained from the room temperature 3F data set.b, Density around the main chain and a chlorophyll. c, Well-resolved ordered water molecules. d, Chlorophyll and pheophytin molecules with well-resolved tails. e, Clear density in hydrophobic regions and along cofactor hydrocarbon tails.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Flash-induced S-state turnover of PSII micro crystals.

a, Change of the first moment of the in situ-measured Mn Kβ XES as a function of flashes and fit to the data. b, Flash-induced O2 yield as measured by MIMS as a function of flash number and fit to the data. c, The estimated S-state population (%) for each of the flash states from fitting of the XES data and of the flash-induced O2 evolution pattern of a suspension of PSII crystals at pH 6.5. Two different fits were performed: a global fit of both O2 and XES data using an equal miss parameter of 22% and 100% Si population in the 0F sample (black traces in a, b; S-state distribution listed in the columns headed O2), and a direct fit of the XES data using a 8% miss parameter in the S1→S2 and a 27% miss parameter for the S2→S3 and S3→S0 transitions (XES in c). For the XES fit, shifts of −0.06 eV per oxidation state increase for all S states were assumed. The XES raw spectra are published elsewhere36.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Isomorphous difference maps in the second monomer at the QB site.

a–c, Fobs − Fobs maps contoured at 3σ at plastoquinone QB in monomer a. a, 1F − 0F difference map matching reduction of the plastoquinone to a semiquinone and concomitant slight geometry change. b, 2F − 0F difference map matching replacement of the fully reduced quinol with another quinone at the original position. c, 3F − 0F difference map, showing again structural changes similar to the 1F − 0F map, indicating formation of the semiquinone. Similar views are shown for monomer A in Fig. 1d–f and comparison of both monomers indicates similar flash-induced changes in both monomers.

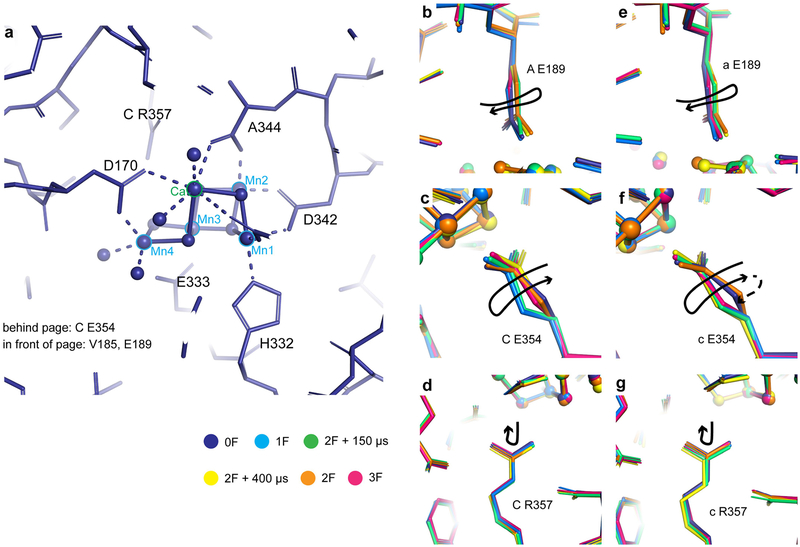

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Movement of ligands around the OEC in the different S states.

a, Overview of the ligand environment of the OEC, showing the dark state (0F) structure. Coordination of the OEC by nearby side chains and water molecules is indicated by dashed lines. b–g, Trends for selected individual side chains in both monomers (b–d, monomer A; e–g, monomer a). Overlays of the refined models at the OEC following least-squares fitting of subunit D1 residues 55–65, 160–190 and 328, subunit CP43 residues 328 and 354–358, and chain D residue 352 of each other model to the 0F model. The largest and most consistent motions of side chains near the OEC through the sequence of illuminated state models are annotated with arrows indicating the trend. A motion observed in only one monomer is indicated by a dashed line.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Impact of the data quality on the resolving power of the maps.

a–f, The data quality evidenced by 2F state models and 2mFobs − DFcalc maps contoured at 1.5σ. a, 5TIS (2F, 2.25 Å) model and map. Overlays indicate atom numbering in the OEC and the identities of selected coordinating sidechains. b, Current 2F model and map cutto 2.25 Å. c, Current 2F model and map at the full 2.07 Å resolution. Emergence of locations of O4 with improved data quality is indicatedby bold arrow. d, As in a from a different angle and with mFobs − DFcalc density at 3σ indicating the lack of sufficient evidence for inserting an additional O atom at a chemically reasonable position. e, f, As in b, c from the same direction as d and with mFobs − DFcalc density at 3σ shown to 2.25 and 2.05 Å, respectively, after omitting the inserted Ox atom. Centring of the refined Ox position within the omit density gives a clear indication of the position of the inserted water in the S3 state with the current, higher-quality data, even when artificially cut to the same resolution as the previous data set. g, mFobs − DFcalc maps of the 2F data that compare the O6 model from Suga et al.9 and the Ox model from the current study. Map shows the mFobs − DFcalc density calculated with our current 2F data and our model adding the O6 position of Suga et al.9 (with the occupancy of 0.7 and B-factor of 30) (g-1), and with our Ox model (g-2). We see clearly a positive density for the missing Ox and a negative density at the O6 position in g-1. Schematics of the O6 and Ox S3 models are shown on the left.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Isomorphous difference maps in the second monomer at the OEC.

Isomorphous difference density OEC sites in monomer a. Fobs − Fobs difference densities between the various illuminated states and the 0F data are contoured at +3σ (blue) and −3σ (orange). The model for the 0F data is shown in light grey whereas carbons are coloured as follows: 1F (cyan), 2F (150 μs) (green), 2F (400 μs) (yellow) and 2F (0.2 s) (blue).

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Water environment of the OEC.

a, Extended schematic of the hydrogen bonding network connecting the OEC to the solvent-exposed surface of PSII and identification of several channels for either possible water movement or proton transfer. Top right, locations of four selected channels in the PSII monomer. b–e, Movements within the water networks across monomers. Coloured spheres are shown for each ordered water or chloride ion across the four metastable states, 0F through 3F, and for both monomers, with the stronger colour matching the first (A) monomer and the lighter colour matching the second (a) monomer. For ordered solvent, residue number is shown; for OEC atoms, the atom identifier is shown; and for the Cl2 site, the Cl− 680 label is shown. b, The O1 water chain. Positional disagreement between monomers is visible especially near waters 77 (2F) and 27 (3F) and is on the same scale as changes between illuminated states, both of which may indicate a more dynamic water channel. c, The O4 water chain. With the notable exception of water 20, most water positions are stable across monomers and illuminated states. Water 20 is highly unstable in position in the two states (0F, 3F) in which it is modelled, and there is not sufficient density in the remaining states to model a water 20 position. d, The Cl1 site water channel with no notable movements. e, The Cl2 site water channel with no notable movements. f, Indication of a split position of W3 in the S0 state. mFobs − DFcalc difference density (green mesh) in the 3F state suggests an alternate position near W3 (W3b in Fig. 4d). g, h, Possible access to W3/Ox side from the Cl1 or the O1 channel. The surface of the protein is shown in grey to visualize the extent of the cavities around the OEC, and Van der Waals radii are indicated for selected residues or atoms by dotted spheres. Shown are two different views for each channel. The direction of the Cl1 channel is indicated by a green arrow and the O1 channel by a pink arrow. Water W2 is shown in purple, W3 in cyan and Ox in orange. Yellow spheres indicate other waters. Mn are shown in magenta, other bridging oxygens as red spheres.

Extended Data Table 1 |.

Merging and refinement statistics for (a) the refined data sets including all lattices or (b) for the additional data sets containing only lattices with unit cells within 1% of the target unit cell

| a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0F | 1F | 2F (150 us) | 2F (400 us) | 2F‡ | 3F‡ | |

| Resolution range refined (Å) | 30.552 – 2.05 | 30.427 – 2.08 | 30.783 – 2.5 | 30.851 – 2.2 | 30.578 – 2.07 | 31.005–2.04 |

| Resolution range upper | 2.085 – 2.05 | 2.116–2.08 | 2.543 – 2.5 | 2.238 – 2.2 | 2.106–2.07 | 2.075 – 2.04 |

| bin (Å) | ||||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.303 | 1.303 | 1.301 | 1.301 | 1.303 | 1.303 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å) | a=116.9 | a=116.8 | a=117.6 | a=117.7 | a=117.0 | a=116.7 |

| b=221.4 | b=220.9 | b=222.7 | b=222.6 | b=221.5 | b=221.2 | |

| c=308.7 | c=307.0 | c=309.1 | c=308.5 | c=308.3 | c=307.6 | |

| Images merged | 30366 | 23744 | 4231 | 13072 | 24481 | 25134 |

| Unique reflections (upper bin) |

508701 (25202) |

487161 (24128) |

281837 (13902) |

412258 (20410) |

494189 (24482) |

516201 (25594) |

| Completeness (upper bin) |

99.95% (99.81%) |

99.95% (99.78%) |

99.92% (99.96%) |

99.94% (99.91%) |

99.95% (99.87%) |

99.95% (99.86%) |

| CC1/2 (upper bin) |

98.7% (1.8%) |

97.5% (1.3%) |

93.8% (6.8%) |

96.0% (0.6%) |

98.2% (2.1%) |

98.6% (0.8%) |

| Multiplicity (upper bin) |

186.8 (9.0) |

160.1 (8.4) |

45.4 (9.2) |

98.4 (9.8) |

156.8 (9.6) |

170.7 (9.3) |

| Pred. multiplicity* (upper bin) |

458.3 (360.4) |

383.1 (301.8) |

88.2 (66.6) |

272.3 (209.9) |

375.1 (291.9) |

413.0 (318.6) |

| l/σHa14(l)† (upper bin) |

16.6 (0.5) |

15.0 (0.5) |

11.1 (1.0) |

10.6 (0.7) |

15.5 (0.6) |

17.0 (0.6) |

| Wilson B-factor | 26.8 | 27.1 | 35.5 | 27.4 | 27.3 | 27.1 |

| R-factor | 18.48% | 18.90% | 16.69% | 19.33% | 18.44% | 18.64% |

| R-free | 23.99% | 24.56% | 24.60% | 26.39% | 24.75% | 24.85% |

| Number of atoms | 103732 | 103728 | 103713 | 103719 | 105764 | 105761 |

| Number non-hydrogen | ||||||

| atoms | 52203 | 52199 | 52188 | 52194 | 53286 | 53283 |

| Ligands | 186 | 186 | 186 | 186 | 188 | 188 |

| Waters | 2021 | 2017 | 2012 | 2016 | 2015 | 2010 |

| Protein residues | 5306 | 5306 | 5306 | 5306 | 5306 | 5306 |

| RMS (bonds) | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| RMS (angles) | 1.51 | 1.53 | 1.57 | 1.61 | 1.52 | 1.50 |

| Ramachandran favored | 96.5% | 95.8% | 94.8% | 95.3% | 96.2% | 96.3% |

| Ramachandran outliers | 0.31% | 0.38% | 0.56% | 0.38% | 0.34% | 0.31% |

| Clashscore | 5.4 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 6.8 |

| Average B-factor | 42.8 | 44.4 | 50.3 | 46.5 | 43.4 | 42.3 |

| b | ||||||

| 0F | 1F | 2F (150 us) | 2F (400 us) | 2F‡ | 3F‡ | |

| Resolution range refined (Å) | 30.05 – 2.07 | 30.04–2.13 | 29.70 – 2.60 | 29.85 – 2.30 | 30.18–2.09 | 30.05 – 2.05 |

| Resolution range upper bin (Å) | 2.11 −2.07 | 2.17–2.13 | 2.65 – 2.60 | 2.34 – 2.30 | 2.13–2.09 | 2.09 – 2.05 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.301 | 1.301 | 1.301 | 1.301 | 1.301 | 1.301 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| a=117.6 | a=117.6 | a=117.6 | a=117.6 | a=117.6 | a=117.6 | |

| b=222.8 | b=222.8 | b=222.8 | b=222.8 | b=222.8 | b=222.8 | |

| Unit cell parameters (Å) | c=309.7 | c=309.7 | c=309.7 | c=309.7 | c=309.7 | c=309.7 |

| Images merged | 15669 | 10757 | 2087 | 4576 | 13603 | 14019 |

| Unique reflections (upper bin) |

490658 (24364) |

450643 (22354) |

249070 (12358) |

358519 (17699) |

476797 (23606) |

505050 (25047) |

| Completeness (upper bin) |

99.96% (99.98%) |

99.95% (99.96%) |

99.91% (99.93%) |

99.93% (99.93%) |

99.96% (99.96%) |

99.95% (99.92%) |

| CC1/2 (upper bin) |

98.2% (2.1%) |

95.6% (2.8%) |

92.4% (6.8%) |

96.1% (2.9%) |

97.7% (0.9%) |

98.0% (0.4%) |

| Multiplicity (upper bin) |

98.5 (11.1) |

71.7 (10.6) |

28.3 (9.8) |

48.3 (10.4) |

89.9 (11.0) |

101.2 (10.6) |

| Pred. multiplicity* (upper bin) |

204.8 (153.1) |

144.2 (107.2) |

41.3 (29.81) |

86.3 (62.32) |

187.6 (139.22) |

210.1 (154.24) |

| l/σHa14(l)† (upper bin) |

13.3 (0.7) |

11.1 (0.7) |

11.5 (1.1) |

10.6 (0.8) |

12.7 (0.7) |

14.3 (0.6) |

| Wilson B-factor | 24.4 | 24.4 | 31.8 | 24.0 | 24.8 | 24.9 |

| R-factor | 19.18% | 19.75% | 17.99% | 19.82% | 19.48% | 19.44% |

| R-free | 23.20% | 24.43% | 23.97% | 24.94% | 23.93% | 23.62% |

| Number of atoms | 52325 | 52154 | 50943 | 51500 | 52251 | 52319 |

| Number non-hydrogen | ||||||

| atoms | 52325 | 52154 | 50943 | 51500 | 52251 | 52319 |

| Ligands | 187 | 187 | 187 | 187 | 187 | 187 |

| Waters | 2226 | 2054 | 843 | 1400 | 2151 | 2219 |

| Protein residues | 5300 | 5300 | 5300 | 5300 | 5300 | 5300 |

| RMS (bonds) | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| RMS (angles) | 0.98 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Ramachandran favored | 97.3% | 97.1% | 96.5% | 96.8% | 97.6% | 97.5% |

| Ramachandran outliers | 0.36% | 0.31% | 0.38% | 0.27% | 0.35% | 0.27% |

| Clashscore | 5.7 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 7.3 | 6.0 | 5.9 |

| Average B-factor | 37.6 | 39.9 | 44.2 | 44.4 | 38.9 | 38.6 |

*Predictions multiplicity is the multiplicity of all spot predictions matching the indexing solution on a given image, before a per-image resolution cutoff. Multiplicities for data sets merged by the Monte Carlo method (for example, Kupitz et al.65, and Suga et al.9) without per-image resolution cutoffs are best compared with this metric.

‡For the 2F and 3F data sets, a region of 66 amino acids around the OEC was modelled as double conformers to reflect the contribution from the two main S-state species in each of the data sets with contributions of 30% and 70% for S2 and S3 in the 2F and 40% and 60% for S3 and S0, respectively, in the 3F data sets.

Extended Data Table 2 |.

Interatomic distances at the OEC in each merged data set, in each monomer (A/a), in Å

| OF | 1F | 2F (150 μs) | 2F (400 μs) | 2F OEI (S3) | 3F OEC (S0) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distances (Å) | A | a | A | a | A | a | A | a | A | a | A | a | |

| CA1- | MN1 | 3.41 | 3.45 | 3.46 | 3.38 | 3.49 | 3.45 | 3.47 | 3.58 | 3.37 | 3.37 | 3.44 | 3.31 |

| MN2 | 3.38 | 3.38 | 3.40 | 3.42 | 3.40 | 3.44 | 3.41 | 3.39 | 3.27 | 3.38 | 3.45 | 3.41 | |

| MN3 | 3.52 | 3.49 | 3.54 | 3.50 | 3.42 | 3.53 | 3.49 | 3.57 | 3.52 | 3.61 | 3.55 | 3.52 | |

| MN4 | 3.77 | 3.88 | 3.90 | 3.90 | 3.72 | 3.96 | 3.84 | 4.07 | 3.90 | 4.11 | 3.94 | 4.07 | |

| MN1- | MN2 | 2.77 | 2.77 | 2.85 | 2.77 | 2.89 | 2.78 | 2.86 | 2.72 | 2.77 | 2.73 | 2.81 | 2.71 |

| MN3 | 3.22 | 3.26 | 3.29 | 3.22 | 3.38 | 3.32 | 3.39 | 3.35 | 3.34 | 3.32 | 3.30 | 3.24 | |

| MN4 | 4.80 | 4.91 | 4.84 | 4.88 | 5.01 | 5.05 | 5.05 | 5.16 | 5.01 | 5.11 | 4.97 | 4.98 | |

| MN2- | MN3 | 2.87 | 2.83 | 2.86 | 2.82 | 2.85 | 2.83 | 2.88 | 2.82 | 2.85 | 2.86 | 2.90 | 2.82 |

| MN3- | MN4 | 2.70 | 2.77 | 2.70 | 2.79 | 2.70 | 2.84 | 2.74 | 2.90 | 2.70 | 2.84 | 2.79 | 2.91 |

| MN1- | Ox | 1.82 | 1.67 | 1.78 | 1.80 | ||||||||

| MN4- | O5 | 2.23 | 2.28 | 2.17 | 2.27 | ||||||||

| O5- | Ox | 1.84* | 1.87* | 2.10 | 2.07 | ||||||||

| MN4- | W1 | 2.18 | 2.13 | 2.06 | 2.17 | 2.03 | 1.97 | 2.37 | 2.23 | 2.16 | 2.10 | 2.04 | 2.01 |

| W2 | 2.12 | 2.14 | 2.13 | 2.19 | 2.09 | 2.37 | 2.20 | 2.43 | 2.11 | 2.13 | 2.22 | 2.22 | |

| CA1- | W3 | 2.53 | 2.53 | 2.58 | 2.63 | 2.58 | 2.59 | 2.52 | 2.57 | 2.51 | 2.58 | 2.61 | 2.56 |

| W3B/C | 3.25 | 4.26 | |||||||||||

| W4 | 2.36 | 2.30 | 2.37 | 2.22 | 2.57 | 2.37 | 2.37 | 2.43 | 2.30 | 2.30 | 2.20 | 2.29 | |

*The O5-Ox distance in the 2F (400 μs) data set is shorter than in the 2F data set as for this data set we did not model two configurations for the OEC. Hence, the O5 position that is used to measure the O5–Ox distance is definitely influenced by the contribution of O5 in the S2 state (closer to Mn1) and only partly by O5 in the S3 state (longer Mn1–O5 distance).

Extended Data Table 3 |.

Channel nomenclature in the literature

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (OBES), Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences (CSGB), Department of Energy (DOE) (J.Y., V.K.Y.), by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants GM055302 (V.K.Y.), GM110501 (J.Y.) GM126289 (J.K.), GM117126 (N.K.S.), GM124149 and GM124169 (J.M.H.), the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (GM116423–02, F.D.F.), and Human Frontiers Science Project RGP0063/2013 (J.Y., U.B., A.Z.). We acknowledge the DFG-Cluster of Excellence “UniCat” coordinated by TU. Berlin and Sfb1078, TP A5 (A.Z., H.D.); the Artificial Leaf Project (K&A Wallenberg Foundation 2011.0055) and Vetenskapsrådet (2016–05183) (J.M.); Diamond Light Source, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant 102593) and a Strategic Award from the Wellcome Trust (A.M.O.). This research used NERSC, supported by DOE, under Contract No. DE-AC02–05CH11231. Synchrotron facilities at the ALS, Berkeley and SSRL, Stanford, were funded by DOE OBES. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE OBER, and NIH (P41GM103393). LCLS and SSRL, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, are supported by DOE, OBES under Contract No. DE-AC02–76SF00515. We thank the staff at LCLS/SLAC and SSRL (BL 6–2, 7–3) and ALS (BL 5.01, 5.0.2, 8.2.1, 8.3.1).

Footnotes

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, statements of data availability and associated accession codes are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0681-2.

Competing interests The authors declare no competing interests.

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0681-2.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0681-2.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kok B, Forbush B & McGloin M Cooperation of charges in photosynthetic O2 evolution—I. A linear four step mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol 11, 457–475 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joliot P, Barbieri G & Chabaud R A new model of photochemical centers in system-2. Photochem. Photobiol 10, 309–329 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillier W & Wydrzynski T 18O-water exchange in photosystem II: substrate binding and intermediates of the water splitting cycle. Coord. Chem. Rev 252, 306–317 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yano J & Yachandra V Mn4Ca cluster in photosynthesis: where and how water is oxidized to dioxygen. Chem. Rev 114, 4175–4205 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox N & Messinger J Reflections on substrate water and dioxygen formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 1020–1030 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debus RJ FTIR studies of metal ligands, networks of hydrogen bonds, and water molecules near the active site Mn4CaO5 cluster in photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847, 19–34 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klauss A, Haumann M & Dau H Seven steps of alternating electron and proton transfer in photosystem II water oxidation traced by time-resolved photothermal beam deflection at improved sensitivity. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 2677–2689 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young ID et al. Structure of photosystem II and substrate binding at room temperature. Nature 540, 453–457 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suga M et al. Light-induced structural changes and the site of O=O bond formation in PSII caught by XFEL. Nature 543, 131–135 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kern J et al. Simultaneous femtosecond X-ray spectroscopy and diffraction of photosystem II at room temperature. Science 340, 491–495 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kulik LV, Epel B, Lubitz W & Messinger J Electronic structure of the Mn4OxCa cluster in the S0 and S2 states of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II based on pulse 55Mn-ENDOR and EPR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 129, 13421–13435 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dau H & Haumann M The manganese complex of photosystem II in its reaction cycle—basic framework and possible realization at the atomic level. Coord. Chem. Rev 252, 273–295 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peloquin JM et al. 55Mn ENDOR of the S2-state multiline EPR signal of photosystem II: Implications on the structure of the tetranuclear cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc 122, 10926–10942 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krewald V et al. Metal oxidation states in biological water splitting. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 6, 1676–1695 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chernev P et al. Merging structural information from X-ray crystallography, quantum chemistry, and EXAFS spectra: The oxygen-evolving complex in PSII. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 10899–10922 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka A, Fukushima Y & Kamiya N Two different structures of the oxygen-evolving complex in the same polypeptide frameworks of photosystem II. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 1718–1721 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaguchi K et al. Theory of chemical bonds in metalloenzymes XXI. Possible mechanisms of water oxidation in oxygen evolving complex of photosystem II. Mol. Phys 116, 717–745 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yano J et al. Where water is oxidized to dioxygen: structure of the photosynthetic Mn4Ca cluster. Science 314, 821–825 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pantazis DA, Ames W, Cox N, Lubitz W & Neese F Two interconvertible structures that explain the spectroscopic properties of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II in the S2 state. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 51, 9935–9940 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Retegan M et al. A five-coordinate Mn(IV) intermediate in biological water oxidation: spectroscopic signature and a pivot mechanism for water binding. Chem. Sci 7, 72–84 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dau H & Haumann M Considerations on the mechanism of photosynthetic water oxidation — dual role of oxo-bridges between Mn ions in (i) redox-potential maintenance and (ii) proton abstraction from substrate water. Photosynth. Res 84, 325–331 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox N et al. Photosynthesis. Electronic structure of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II prior to O–O bond formation. Science 345, 804–808 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegbahn P E. M. Structures and energetics for O2 formation in photosystem II. Acc. Chem. Res 42, 1871–1880 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Wijn R & van Gorkom HJ Kinetics of electron transfer from QA to QB in photosystem II. Biochemistry 40, 11912–11922 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakamoto H, Shimizu T, Nagao R & Noguchi T Monitoring the reaction process during the S2→S3 transition in photosynthetic water oxidation using time-resolved infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 2022–2029 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossini E & Knapp E-W Protonation equilibria of transition metal complexes: from model systems toward the Mn-complex in photosystem II. Coord. Chem. Rev 345, 16–30 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Askerka M, Wang J, Vinyard DJ, Brudvig GW & Batista VS S3 O2-evolving complex of photosystem II: insights from QM/MM, EXAFS, and femtosecond X-ray diffraction. Biochemistry 55, 981–984 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boussac A & Rutherford AW Nature of the inhibition of the oxygen-evolving enzyme of photosystem II induced by NaCl washing and reversed by the addition of Ca2+ or Sr2+. Biochemistry 27, 3476–3483 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tso J, Sivaraja M & Dismukes GC Calcium limits substrate accessibility or reactivity at the manganese cluster in photosynthetic water oxidation. Biochemistry 30, 4734–4739 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki H, Sugiura M & Noguchi T Monitoring water reactions during the S-state cycle of the photosynthetic water-oxidazing center: detection of the DOD bending vibration by means of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry 47, 11024–11030 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barber J A mechanism for water splitting and oxygen production in photosynthesis. Nat. Plants 3, 17041 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hellmich J et al. Native-like photosystem II superstructure at 2.44 Å resolution through detergent extraction from the protein crystal. Structure 22, 1607–1615 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibrahim M et al. Improvements in serial femtosecond crystallography of photosystem II by optimizing crystal uniformity using microseeding procedures. Struct. Dyn 2, 041705 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guskov A et al. Cyanobacterial photosystem II at 2.9-Å resolution and the role of quinones, lipids, channels and chloride. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 16, 334–342 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krivanek R, Kern J, Zouni A, Dau H & Haumann M Spare quinones in the QB cavity of crystallized photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus elongatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 520–527 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fransson T et al. X-ray emission spectroscopy as an in situ diagnostic tool for X-ray crystallography of metalloproteins using an X-ray free-electron laser. Biochemistry 57, 4629–4637 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuller FD et al. Drop-on-demand sample delivery for studying biocatalysts in action at X-ray free-electron lasers. Nat. Methods 14, 443–449 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kern J et al. Taking snapshots of photosynthetic water oxidation using femtosecond X-ray diffraction and spectroscopy. Nat. Commun 5, 4371 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yano J et al. in Sustaining Life on Planet Earth: Metalloenzymes Mastering Dioxygen and Other Chewy Gases, Metal Ions in Life Sciences (eds Kroneck PMH & Sosa Torres ME) 13–43 (Springer International Publishing, 2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beckmann K, Messinger J, Badger MR, Wydrzynski T & Hillier W On-line mass spectrometry: membrane inlet sampling. Photosynth. Res 102, 511–522 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emma P et al. First lasing and operation of an Ångström-wavelength free-electron laser. Nat. Photon 4, 641–647 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boutet S, Cohen A & Wakatsuki S The new macromolecular femtosecond crystallography (MFX) instrument at LCLS. Synchr. Radiat. News 29, 23–28 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sauter NK XFEL diffraction: developing processing methods to optimize data quality. J. Synchr. Radiat 22, 239–248 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winter G et al. DIALS: implementation and evaluation of a new integration package. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol 74, 85–97 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sauter NK, Hattne J, Grosse-Kunstleve RW & Echols N New Python-based methods for data processing. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 69, 1274–1282 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hattne J et al. Accurate macromolecular structures using minimal measurements from X-ray free-electron lasers. Nat. Methods 11, 545–548 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sauter NK et al. Improved crystal orientation and physical properties from single-shot XFEL stills. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 70, 3299–3309 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waterman DG et al. Diffraction-geometry refinement in the DIALS framework. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol 72, 558–575 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeldin OB et al. Data Exploration Toolkit for serial diffraction experiments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 71, 352–356 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andrews LC & Bernstein HJ The geometry of Niggli reduction: BGAOL - embedding Niggli reduction and analysis of boundaries. 47, 346–359 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suga M et al. Native structure of photosystem II at 1.95 Å resolution viewed by femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature 517, 99–103 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uervirojnangkoorn M et al. Enabling X-ray free electron laser crystallography for challenging biological systems from a limited number of crystals. eLife 4, e05421 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lyubimov AY et al. Advances in X-ray free electron laser (XFEL) diffraction data processing applied to the crystal structure of the synaptotagmin-1/SNARE complex. eLife 5, e18740 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams PD et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Afonine PV et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 68, 352–367 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wieghardt K The active-sites in manganese-containing metalloproteins and inorganic model complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn Engl 28, 1153–1172 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cinco RM et al. Comparison of the manganese cluster in oxygen-evolving photosystem II with distorted cubane manganese compounds through X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Inorg. Chem 38, 5988–5998 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mukhopadhyay S, Mandal SK, Bhaduri S & Armstrong WH Manganese clusters with relevance to photosystem II. Chem. Rev 104, 3981–4026 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Law NA, Caudle MT & Pecoraro VL Manganese redox enzymes and model systems: Properties, structures, and reactivity. Adv. Inorg. Chem 46, 305–440 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsui EY, Kanady JS & Agapie T Synthetic cluster models of biological and heterogeneous manganese catalysts for O2 evolution. Inorg. Chem 52, 13833–13848 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schrödinger LLC. The pymol molecular graphics system, version 1.8 (2015).

- 63.Lang PT, Holton JM, Fraser JS & Alber T Protein structural ensembles are revealed by redefining X-ray electron density noise. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 237–242 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brewster AS et al. Improving signal strength in serial crystallography with DIALS geometry refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol 74, 877–894 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kupitz C et al. Serial time-resolved crystallography of photosystem II using a femtosecond X-ray laser. Nature 513, 261–265 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ho FM & Styring S Access channels and methanol binding site to the CaMn4 cluster in Photosystem II based on solvent accessibility simulations, with implications for substrate water access. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 140–153 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vassiliev S, Zaraiskaya T & Bruce D Exploring the energetics of water permeation in photosystem II by multiple steered molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 1671–1678 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murray JW & Barber J Structural characteristics of channels and pathways in photosystem II including the identification of an oxygen channel. J. Struct. Biol 159, 228–237 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gabdulkhakov A et al. Probing the accessibility of the Mn4Ca cluster in photosystem II: channels calculation, noble gas derivatization, and cocrystallization with DMSO. Structure 17, 1223–1234 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen J-R & Kamiya N Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å. Nature 473, 55–60 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sakashita N, Watanabe HC, Ikeda T & Ishikita H Structurally conserved channels in cyanobacterial and plant photosystem II. Photosynth. Res 133, 75–85 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the following accession codes: 6DHE for the 0F, 6DHF for the 1F, 6DHO for the 2F, 6DHG for the 2F(150μs), 6DHH for the 2F(400μs) and 6DHP for the 3F data.