Abstract

Objective:

The management of diabetic patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery continues to be unsystematic, despite evidence that standardized perioperative glycemic control is associated with fewer postoperative surgical complications. We examined the efficacy of a pre-operative diabetes optimization protocol implemented at a single institution in improving perioperative glycemic control with a target blood glucose of 80 to 180 mg/dL.

Methods:

Patients with established and newly diagnosed diabetes who underwent elective colorectal surgery were included. The control group comprised 103 patients from January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2013, before protocol implementation. The glycemic-optimized group included 96 patients following protocol implementation from January 1, 2014, through July 31, 2016. Data included demographic information, blood glucose levels, insulin doses, hypoglycemic events, and clinical outcomes (length of stay, re-admissions, complications, and mortality).

Results:

Patients enrolled in the glycemic optimization protocol had significantly lower glucose levels intra-operatively (145.0 mg/dL vs. 158.1 mg/dL; P = .03) and postoperatively (135.6 mg/dL vs. 145.2 mg/dL; P = .005). A higher proportion of patients enrolled in the protocol received insulin than patients in the control group (0.63 vs. 0.48; P = .01), but the insulin was administered less frequently (median [interquartile range] number of times, 6.0 [2.0 to 11.0] vs. 7.0 [5.0 to 11.0]; P = .04). Two episodes of symptomatic hypoglycemia occurred in the control group. There was no difference in clinical outcomes.

Conclusion:

Improved peri-operative glycemic control was observed following implementation of a standardized institutional protocol for managing diabetic patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus affects an estimated 12.2% of U.S. adults, and approximately 25% of patients with diabetes mellitus will undergo surgery during their lifetime (1–5). Poor glycemic control manifested as an elevated level of pre-operative glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) or hyperglycemia in the immediate peri-operative period of patients with and without a diagnosis of diabetes is strongly associated with postoperative complications (6). Efforts to reduce postoperative hyperglycemia with intensive glucose inpatient management protocols and restrictive blood glucose targets have often resulted in increased all-cause mortality rates and worse clinical outcomes (7–11), though some studies have documented improved outcomes (12,13). The American Diabetes Association recommends moderate glycemic control in the postoperative periods, targeting blood glucose values of 80 to 180 mg/dL. Currently, data are limited regarding the effect of peri-operative management protocols designed to achieve moderate glycemic control for surgical patients with known or previously undiagnosed diabetes mellitus (4,14). Also unclear is whether short-term optimization of blood glucose levels among patients with poorly controlled glucose levels—feasible in the immediate pre-operative setting for elective surgical procedures—can reverse some of the detrimental effects of chronic hyperglycemia peri-operatively.

To address this critical knowledge gap, we examined the efficacy of a pre-operative diabetes optimization protocol implemented at a single institution in improving pre-, intra-, and postoperative glycemic control among patients with established and newly diagnosed diabetes who underwent elective colorectal surgery. Our investigation focused on colorectal surgery patients because the operations are relatively common and strongly affect a patient’s nutrition status—and subsequently, blood glucose control—both before and after surgery. Further, we identified the specific patient and protocol characteristics that most influence successful diabetes management and thereby are crucial for informing a broader program implementation.

METHODS

Study Design

A retrospective review was conducted of a prospectively maintained clinical database that includes adults (age ≥18 years) with diabetes mellitus who underwent elective colorectal surgery at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, between January 1, 2011, and July 31, 2016. This Mayo Clinic campus in northeast Florida includes a multispecialty hospital with 306 beds and more than 14,000 surgical cases per year. It is an integrated health care delivery system specializing in providing tertiary and quaternary care in the Southeast region of the United States.

Study participants were patients who had a known diagnosis of diabetes at presentation or received the diagnosis during pre-operative evaluations and who were scheduled for elective colorectal surgery. The diabetes diagnosis was established from one or more of the following criteria: adult onset of diabetes mellitus included in the patient’s past medical history; any glucose-lowering medication (including metformin) in the home medication list; and an HbA1c level of ≥6.5% (48 mmol/mol) within 3 months before surgery, including the pre-operative evaluation visit. Patients who were enrolled in the glycemic optimization protocol were compared with historical controls from 2011 through 2013 (n = 94, before program rollout), as well as patients who were inadvertently not enrolled in the program (n = 9) (<10% of eligible patients were not enrolled because of program error). The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Glycemic Optimization Protocol

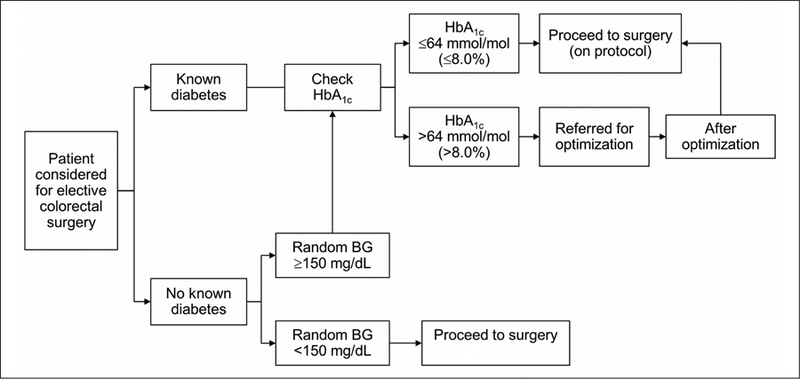

In 2012, a multisite task force was formed to standardize the care of all adult diabetic patients undergoing surgery within the Mayo Clinic Enterprise. This multidisciplinary team established the practice guidelines for the glycemic optimization of surgical patients at all Mayo Clinic sites. The institutional protocol (see Appendix A) is based on adaptations of clinical practice guidelines from the Endocrine Society (15) and has been previously described in a detailed review by Dortch and colleagues pertaining to plastic surgery patients (16). These practice guidelines have been implemented within the surgery department of Mayo Clinic Florida. The key steps are summarized in Figure 1. Briefly, at Mayo Clinic in Florida, all patients age 18 years and older who are scheduled to undergo an elective operation in the inpatient or outpatient setting are evaluated in a pre-operative clinic, staffed by anesthesiologists and advanced registered nurse practitioners, for medical optimization and clearance. All patients with known diabetes have an HbA1c check. Patients without a diabetes diagnosis are screened for the condition with an HbA1c check if their random blood glucose is greater than 150 mg/ dL at the pre-operative visit. Those patients with an HbA1c of 8.0% (64 mmol/mol) or greater are referred for glycemic optimization, which is managed by their established primary medical provider or an endocrinology consult for patients receiving a new diagnosis of diabetes. Patients referred for glycemic optimization receive individualized regimens to improve their glycemic control based on a review of their glycemic status by these providers.

Fig. 1.

Pre-operative optimization algorithm. BG = blood glucose; HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin A1c.

The goal of the glycemic optimization protocol is to achieve and maintain fasting glucose levels less than 180 mg/dL for 2 weeks before a patient’s elective surgery; if this glucose level is not achieved, the operation is delayed until the level is obtained. This delay in virtually all cases did not exceed 2 weeks, and no patients were lost due to the delay. The protocol also includes close glucose management in the pre-operative care unit and intra-operatively by the anesthesia team. Postoperatively, the patient’s glucose level is managed by the primary surgical service. With help from a diabetes management team, subcutaneous insulin is administered before meals and at bedtime to target fasting blood glucose levels between 100 and 140 mg/dL. Patients with an anticipated length of stay less than 48 hours may continue to receive home noninsulin medications if preferred by the surgical service and the patient, but the transition to insulin is strongly encouraged. On discharge, a patient’s diabetes management reverts to the patient’s established primary medical provider.

Care for surgical diabetes patients before protocol implementation was not standardized. Patients usually received a single point-of-care blood glucose check immediately before surgery and on conclusion of surgery, and glucose level was typically managed intraoperatively with intravenous insulin at the discretion of the anesthesia provider.

Study Outcomes

The primary study outcome was the extent of blood glucose control among patients enrolled versus those not enrolled in the glycemic optimization protocol. To determine control, we measured blood glucose levels on admission (pre-operative level), during surgery (intra-operative level), and after surgery (postoperative level). The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare median results for each time period because glucose values were skewed. Both venous and capillary glucose readings were used (StatStrip glucometer; Nova Biomedical). Secondary outcomes were mean total daily insulin doses, frequency of hypoglycemic events (blood glucose <71 mg/dL) before, during, and after surgery, length of stay, re-admissions, postoperative complications, and mortality. Postoperative complications assessed include surgical site infection, bleeding, renal insufficiency, stroke, acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and septicemia.

Independent Variables

Type of colorectal operation and patient demographic characteristics and comorbidities were identified from electronic health records.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive variables, counts of hyperglycemic and hypoglycemic events, and clinical outcomes were compared with the Wilcoxon rank sum and χ2 tests. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc).

RESULTS

A total of 199 adults with a diabetes diagnosis underwent elective colorectal surgery at Mayo Clinic in Florida between 2011 and 2016. Of these patients, 96 were enrolled in the glycemic optimization protocol (implemented in January 2014) and 103 comprised the control group. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were found between the two groups with respect to age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, body mass index, baseline HbA1c percent (6.7% in both groups), and surgical type.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Surgical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Groupa | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 103) | Optimized (n = 96) | ||

| Age, years | .26b | ||

| Mean (SD) | 60.7 (13.6) | 62.3 (12.0) | |

| Median (IQR) | 60.0 (51.0–70.0) | 65.0 (56.0–71.0) | |

| Range | 24.0–86.0 | 22.0–82.0 | |

| Sex | .27c | ||

| Female | 41 (39.8) | 31 (32.3) | |

| Male | 62 (60.2) | 65 (67.7) | |

| ASA class | .73c | ||

| Missing, no. of patients | 1 | 0 | |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | |

| 2 | 18 (17.6) | 19 (19.8) | |

| 3 | 80 (78.4) | 73 (76.0) | |

| 4 | 4 (3.9) | 3 (3.1) | |

| BMI | .20b | ||

| Mean (SD) | 30.4 (5.6) | 29.3 (5.7) | |

| Median (IQR) | 30.0 (26.1–33.5) | 28.9 (25.5–32.5) | |

| Range | 19.8–48.3 | 17.5–45.4 | |

| Surgery type | .26c | ||

| Colorectal resection | 38 (36.9) | 41 (42.7) | |

| Hemorrhoid procedures | 13 (12.6) | 10 (10.4) | |

| Stoma surgery (colostomy, ileostomy, stoma closure) | 8 (7.8) | 8 (8.3) | |

| Small-bowel resection | 6 (5.8) | 11 (11.5) | |

| Rectal dilation/proctopexy | 4 (3.9) | 4 (4.2) | |

| Fistulectomy/fissurectomy/sphincterotomy | 16 (15.5) | 7 (7.3) | |

| Incision and drainage of anorectal abscess | 9 (8.7) | 3 (3.1) | |

| Appendectomy | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other procedures (adhesiolysis, hernia repair, debridement, etc.) | 8 (7.8) | 12 (12.5) | |

Abbreviations: ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI = body mass index; IQR = interquartile range; LOS = length of stay.

Values are presented as number and percentage of patients unless specified otherwise.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

χ2 test.

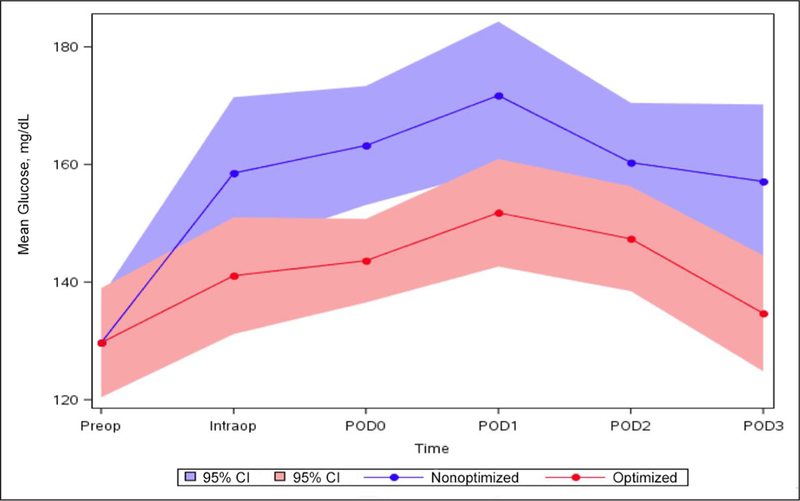

Pre-operative mean glucose levels among the enrolled and control patients were not significantly different (Table 2). However, glucose levels during and after the surgical procedure were significantly lower among patients enrolled in the glycemic optimization protocol. Specifically, intra-operative median glucose level was 145.0 (interquartile range [IQR], 114.0 to 167.9) mg/dL among enrolled patients and 158.1 (IQR, 137.5 to 182.0) mg/dL among controls (P = .03). Postoperatively, median glucose levels were 135.6 (IQR, 117.0 to 162.3) mg/dL among enrolled patients and 145.2 (IQR, 131.0 to 181.2) mg/dL among controls (P = .005) (Fig. 2). Six episodes of hypoglycemia (blood glucose, <70 mg/dL) occurred in each group. Of those, two episodes (both in the control group) were symptomatic but resolved with oral glucose administration (45 mg/dL and 52 mg/dL); neither resulted in loss of consciousness. A similar number of glucose measurements per hospital stay per patient was obtained in both groups (mean, 12.3 measurements vs. 14.9 measurements; P = .14).

Table 2.

Glucose Control and Insulin Administration

| Characteristic | Group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 103) | Optimized (n = 96) | ||

| HbA1c within 90 days pre-operatively | (n = 74) | (n = 86) | .77a |

| Mean (SD) | 6.7 (1.2) | 6.7 (1.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 6.5 (5.9–7.3) | 6.4 (5.9–7.2) | |

| Range | 4.4–11.6 | 5.0–13.2 | |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL | |||

| Pre-operative | (n = 75) | (n = 79) | .93a |

| Mean (SD) | 129.7 (33.9) | 129.4 (42.2) | |

| Median (IQR) | 123.0 (104.0–148.0) | 125.0 (105.0–143.5) | |

| Range | 65.0–231.0 | 55.5–325.0 | |

| Intra-operative | (n = 30) | (n = 52) | .03a |

| Mean (SD) | 159.8 (34.0) | 140.1 (35.6) | |

| Median (IQR) | 158.1 (137.5–182.0) | 145.0 (114.0–167.9) | |

| Range | 95.5–240.0 | 73.0–205.0 | |

| Postoperative | (n = 87) | (n = 88) | .005a |

| Mean (SD) | 155.9 (39.2) | 139.7 (30.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 145.2 (131.0–181.2) | 135.6 (117.0–162.3) | |

| Range | 71.0–261.8 | 78.5–208.7 | |

| No. of blood glucose measurements | |||

| Pre-operative | (n = 75) | (n = 79) | .31a |

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | |

| Range | 1.0–2.0 | 1.0–2.0 | |

| Intra-operative | (n = 30) | (n = 52) | .62a |

| Mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.8) | 2.1 (1.4) | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | |

| ange | 1.0–9.0 | 1.0–6.0 | |

| Postoperative | (n = 87) | (n = 88) | .11a |

| Mean (SD) | 13.8 (13.2) | 10.9 (11.2) | |

| Median (IQR) | 12.0 (2.0–20.0) | 10.0 (1.0–15.0) | |

| Range | 1.0–55.0 | 1.0–57.0 | |

| Insulin | |||

| No. of doses | (n = 49) | (n = 61) | .04a |

| Mean (SD) | 9.9 (9.1) | 7.3 (7.1) | |

| Median (IQR) | 7.0 (5.0–11.0) | 6.0 (2.0–11.0) | |

| Range | 1.0–51.0 | 1.0–38.0 | |

| Total units | (n = 49) | (n = 61) | .006a |

| Mean (SD) | 62.2 (104.7) | 36.0 (70.2) | |

| Median (IQR) | 28.0 (18.0–64.0) | 20.0 (4.0–40.0) | |

| Range | 2.0–657.0 | 2.0–520.0 | |

| No. of hypoglycemic events | 6 (5.8) | 6 (6.3) | .90b |

Abbreviations: HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin; IQR = interquartile range.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

χ2 test.

Fig. 2.

Mean glucose and time interval by study group. Intraop = intra-operative; POD0 = day of elective surgical procedure; POD1 = postoperative day 1; POD2 = postoperative day 2; POD3 = postoperative day 3; Preop = pre-operative.

A higher proportion of patients enrolled in the protocol received insulin than patients in the control group (0.63 vs. 0.48; P = .01), but the insulin was administered less frequently (median [IQR] number of times, 6.0 [2.0 to 11.0] vs. 7.0 [5.0 to 11.0]; P = .04). The optimized group also received less insulin overall (median [IQR], 20.0 [4.0 to 40.0] U vs. 28.0 [18.0 to 64.0] U; P = .006) (Table 2). Table 3 shows the insulin types and oral hypoglycemic agents used during hospitalization.

Table 3.

Types of Insulin and Oral Hypoglycemic Agents Used During Hospitalization

| Medication | Group | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 103) | Optimized (n = 96) | ||

| Insulin | (n = 49) | (n = 61) | |

| Insulin aspart, total unitsb | |||

| Pre-operative | (n = 49) | (n = 61) | <.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (1.8) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | |

| Range | 0.0–0.0 | 0.0–10.0 | |

| Intra-operative | (n = 49) | (n = 61) | <.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.6 (2.5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | |

| Range | 0.0–0.0 | 0.0–10.0 | |

| Postoperative | (n = 49) | (n = 61) | <.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 38.8 (33.8) | 23.7 (57.9) | |

| Median (IQR) | 24.0 (18.0–52.0) | 10.0 (4.0–24.0) | |

| Range | 2.0–172.0 | 0.0–438.0 | |

| Insulin determir, total unitsc | (n = 6) | (n = 11) | .55 |

| Mean (SD) | 159.0 (225.2) | 51.3 (25.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 64.0 (30.0–171.0) | 58.0 (30.0–72.0) | |

| Range | 20.0–605.0 | 10.0–90.0 | |

| Regular insulin (1 unit/mL -NS 100 mL IV), total unitsc | (n = 3) | (n = 1) | .37 |

| Mean (SD) | 25.0 (7.4) | 14.4 (0.0) | |

| Median (IQR) | 24.9 (17.6–32.5) | 14.4 (14.4–14.4) | |

| Range | 17.6–32.5 | 14.4–14.4 | |

| Regular insulin (IV push), total unitsc | (n = 4) | (n = 0) | <.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Median (IQR) | 7.0 (3.5–11.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | |

| Range | 3.0–12.0 | 0.0–0.0 | |

| Oral agents | (n = 8) | (n = 3) | |

| Metformin, total dose (mg)c | (n = 6) | (n = 2) | .24 |

| Mean (SD) | 1,916.7 (1,114.3) | 3,200.0 (282.8) | |

| Median (IQR) | 1,750.0 (1,000.0–2,000.0) | 3,200.0 (3,000.0–3,400.0) | |

| Range | 1,000.0–4,000.0 | 3,000.0–3,400.0 | |

| Glipizide, total dose (mg)c | (n = 2) | (n = 1) | .54 |

| Mean (SD) | 17.5 (3.5) | 10.0 (0) | |

| Median (IQR) | 17.5 (15.0–20.0) | 10.0 (10.0–10.0) | |

| Range | 15.0–20.0 | 10.0–10.0 | |

| Glimepiride, total dose (mg)c | (n = 2) | (n = 0) | <.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | |

| Range | 2.0–2.0 | 0.0–0.0 | |

Abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range; IV = intravenous; NS = normal saline.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Administered pre-, intra-, and postoperatively.

Administered postoperatively only.

No significant differences were found between the two groups with respect to surgical length of stay (P = .56), re-admissions (P = .33), postoperative complications (P = .88), and mortality (P = .30) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Glycemic Optimization and Clinical Outcomes

| Characteristic | Groupa | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 103) | Optimized (n = 96) | ||

| Hospital LOS | .56b | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.7 (2.7) | 2.6 (2.6) | |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.5) | |

| Range | 0.0–14.0 | 0.0–13.0 | |

| Re-admissions within 30 days postoperatively, % | 5 (4.9) | 3 (3.1) | .33c |

| Complications within 30 days postoperatively, % | 18 (17.5) | 16 (16.7) | .88c |

| Surgical site infections | 9 (8.7) | 5 (5.2) | |

| Bleeding | 4 (3.9) | 2 (2.1) | |

| Renal failure | 3 (2.9) | 7 (7.3) | |

| Othersd | 2 (1.9) | 2 (2.1) | |

| Mortality within 30 days postoperatively, % | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) | .30c |

Abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range; LOS = length of stay.

Values are presented as number and percentage of patients unless specified otherwise.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

χ2 test.

Others include stroke, acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and septicemia.

DISCUSSION

Despite the known importance of glycemic control in the peri-operative setting, no standard protocol or process exists for optimally managing poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, defined as HbA1c greater than 8.0% (64 mmol/mol), before a patient’s surgical hospital stay (17). Inadequate glycemic control before, during, and after surgery has been associated with worse surgical outcomes, including increased risk of infection, longer length of stay, poor wound healing, and death (18,19). Yet, the literature suggests that a large percentage of diabetic patients undergoing surgery do not receive optimal treatment of their diabetes in the peri-operative period, and many cases of poorly controlled diabetes are unrecognized pre-operatively (20,21). To improve the care delivered to patients with diabetes who are undergoing elective surgery, our institution developed and successfully implemented a peri-operative glycemic optimization protocol for all diabetic patients. This standardized protocol for managing diabetes mellitus among patients undergoing elective operation significantly improved intra-and postoperative blood glucose levels, decreased the amount of insulin needed to achieve euglycemia, and did not increase the incidence of hypoglycemia among our colorectal surgery patients. These findings are consistent with the literature, which indicates that pre-operative and inpatient diabetes management improves glycemic control peri-operatively, which may eventually improve clinical outcomes without increasing the incidence of hypoglycemia (22–24).

Our institutional protocol for managing diabetic patients before and during the hospital stay for surgery is notable for several factors, which likely contributed to its efficacy and safety. First, all patients were screened for diabetes at the pre-operative evaluation visit, thereby reducing the rate of newly diagnosed diabetes discovered during hospitalization. Diabetes management could be done proactively with a defined plan. Second, all patients with uncontrolled diabetes were required to achieve and maintain glycemic control for 2 weeks before surgery, with all elective procedures delayed until euglycemia was successfully achieved. The outpatient health care teams of all patients were actively engaged in this multidisciplinary process. We believe that early engagement of a patient’s medical care team can ultimately lead to better diabetes management subsequent to hospital discharge as well. The effect of the glycemic optimization protocol on postdischarge glycemic control is currently under investigation.

Of note, postoperative glycemic control was achieved preferentially with subcutaneous insulin rather than continuous intravenous infusion (25,26), a regimen associated with better management of hyperglycemia, fewer hypoglycemic events, and smaller doses of insulin overall. The latter two findings were previously noted in the medical patient population (27). Our study extends these observations to the elective-surgery patient population.

This study was conducted among patients undergoing colorectal surgery because they may be highly prone to large oscillations of glycemic control caused by anticipated and unanticipated changes in nutrition, appetite, and food absorption before and after their surgical procedures. Whether our findings are generalizable to other procedures is under exploration. Furthermore, this study needs to be considered in the context of its limitations, most of which stem from its retrospective design, with potential for confounding by patient-and practice-related factors stemming from comparison of patients enrolled in the glycemic optimization protocol with primarily historical control patients. Our study may be underpowered to show a difference in clinical outcomes due to the sample size. Thus, larger and prospective studies to investigate the effect of the protocol on surgical outcomes are warranted. In addition, this single-institution experience reflects the institution’s surgical mix and was reliant on its electronic clinical systems to capture complications and re-admissions. Glucose measurements accuracy is also limited by the method used. Further validation from other institutions and for other surgical procedures would be beneficial.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we found that systematic implementation of a comprehensive protocol of managing diabetes during a peri-operative episode was associated with improved glucose control. This study is distinctive in that it provides a comprehensive (pre-, intra-, and postoperative) protocol applied universally to all diabetic patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. The next step is to expand this protocol-based treatment to beyond the diabetes population with colorectal procedures and to all diabetic patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the Mayo Clinic Enterprise Surgical Glycemic Control Workgroup for exceptional work in developing and implementing the protocol on which this work is based. Author contributions: Dorin T. Colibaseanu, Rozalina G. McCoy, Osayande Osagiede, Aaron C. Spaulding, Michelle F. Perry, and Robert R. Cima designed and performed the study. Launia J. White, Osayande Osagiede, and Dorin T. Colibaseanu performed data collection; Elizabeth B. Habermann, James M. Naessens, and Launia J. White provided the statistical analysis. All authors were involved with manuscript writing, critical review, and approved the final version.

Abbreviations:

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin A1c

- IQR

interquartile range

APPENDIX

Mayo Clinic Enterprise Glycemic Control in Surgical Patients: Practice Guidelines

PRE-ANESTHESIA MEDICAL EXAM

- All patients with diabetes undergoing an elective procedure should have a Pre-anesthesia Medical Exam (PAME) or be evaluated in the Pre-operative Evaluation (POE) clinic prior to surgery.

- If a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level has not been measured within 3 months prior to evaluation and the patient has not received a red cell transfusion within 120 days, it should be obtained, reviewed, and documented.

- Management of HbA1c >8.0%.

- For elective surgery:

- Consider referral back to the patient’s primary medical provider or obtain an Endocrinology consult to review and improve glycemic control prior to surgery.

- For urgent surgery or inpatients requiring surgery:

- An Endocrinology consult should be obtained while the patient is in hospital in order to optimize the medical regimen in the postoperative period and at dismissal.

All diabetic patients when scheduled for elective surgery should receive patient education material. The PAME or POE clinic will be responsible for educating the patient on pre-operative instructions that apply to the patient’s individual diabetes medical regimen (diet, oral diabetes medications, insulin type, or combination regimen).

All pregnant patients with gestational diabetes being prepared for nonobstetric surgery should have an Endocrinology consult pre-operatively.

PREPROCEDURAL AREA (MORNING OF SURGERY)

- Patients need to have a blood glucose checked upon admission and then every hour while nil per os (NPO).

- Point-of-care testing can be used, if available.

Assess and document diabetes medication taken prior to arrival.

- Management of blood glucose levels:

- For blood glucose levels ≤70 mg/dL, institute the treatment for hypoglycemia protocol

- For blood glucose levels ≥140 mg/dL:

- Use of corrective scale subcutaneous insulin is the preferred method of treatment according to institution protocols.

- For patients controlled by oral diabetes meds plus basal insulin if basal insulin not given in previous 24 hours, give ½ usual basal insulin dose only. Oral diabetes medications should not be given.

- For patients controlled by insulin only (prior to surgery) if on basal insulin and not given within previous 24 hours, give usual (full) basal insulin dose.

INTRA-OPERATIVE

- Patients with diabetes should have blood glucose levels checked at the start of the surgical procedure and at least hourly during the procedure. Frequent blood glucose checks allow a provider to monitor for hyperglycemia and minimize the risk of hypoglycemia. Treatment is not indicated every hour.

- Point-of-care testing can be used, if available.

- Patients with type 1 diabetes, including those on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy (insulin pumps) require a constant supply of insulin and should have some form of insulin therapy continued or started during any surgical procedure.

- Patients with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion pumps require insulin dosing based on individual needs which should be established pre-operatively. Follow appropriate institutional guidelines for ambulatory insulin infusion pumps.

- Management Recommendations

- For blood glucose levels ≤70 mg/dL, institute the treatment for hypoglycemia protocol.

- For blood glucose levels ≥140 mg/dL:

- In stable patients with good perfusion undergoing procedures <2 hours in duration, corrective scale subcutaneous insulin, when feasible, should be used according to institution protocols.

- In unstable patients, those with poor perfusion, procedures >2 hours, and those where subcutaneous insulin administrations is not possible due to surgical factors, insulin therapy should be instituted using continuous intravenous insulin infusions, according to institution protocols.

If more than one subcutaneous insulin dose is required within a 2-hour period, consider initiation of intravenous insulin infusion, as repeated subcutaneous insulin doses given in short timeframes may cause hypoglycemia.

Patients undergoing procedures which have specific glucose management protocol (e.g., cardiac surgery) should be treated according to those procedure specific protocols.

Intravenous bolus insulin is discouraged as the sole management of hyperglycemia due to the short half-life of intravenous insulin.

POSTANESTHESIA CARE UNIT (PACU)

- Patients with diabetes should have a blood glucose level checked upon arrival to the PACU and hourly thereafter.

- Point-of-care testing can be used, if available.

- Recommended management of blood sugars:

- For blood glucose levels ≤70 mg/dL, institute the treatment for hypoglycemia protocol.

- For blood glucose levels ≥140 mg/dL, corrective scale subcutaneous insulin or continuous intravenous insulin infusion according to institution protocols is recommended.

TRANSITION FROM INTRAVENOUS (IV) INSULIN INFUSION TO SUBCUTANEOUS INSULIN IN THE PACU

Patients on continuous IV insulin infusions require a transition plan prior to leaving the PACU.

- Options include:

- No subcutaneous basal insulin injection.

- Subcutaneous basal insulin injection.

- Continuation of IV insulin infusion with or without a subcutaneous basal insulin injection.

- Any patient leaving the PACU on a continuous IV insulin infusion must be transferred to a care setting with an appropriate level of monitoring to avoid hypoglycemia.

It is essential that the patient’s transition plan including medications, dose, and time of administration be communicated to the receiving care unit as part of the nursing care report.

PACU TO ICU: CONTINUATION OF IV INSULIN INFUSION

Continue IV insulin infusion.

Transition to ICU IV insulin protocol, if available.

- Initiate hourly blood glucose checks while the patient is on the continuous IV insulin infusion.

- Point-of-care testing can be used, if available.

PACU TO GENERAL CARE UNIT: TRANSITION FROM IV INSULIN INFUSION TO SUBCUTANEOUS INSULIN

- Patients with type 1 diabetes should not have a continuous IV insulin infusion discontinued without having a subcutaneous basal insulin injection. These patients need a specific plan for insulin at all times.

- The subcutaneous basal insulin injection should be administered 2–3 hours before discontinuing the continuous IV infusion.

- Patient with diabetes using only an oral agent pre-operatively.

- Requiring 1 unit/hour or less from a continuous IV insulin infusion and has had blood glucose levels consistently <140 mg/dL.

- Consider discontinuing IV insulin infusion without subcutaneous transition dose.

- Check blood glucose level upon arrival to the general care unit.

- Point-of-care testing can be used, if available.

- Order blood glucose levels four times daily and corrective scale subcutaneous insulin.

- Requiring >1 unit/hour from a continuous IV insulin infusion and/or blood glucose levels that are consistently >140 mg/dL.

- Administer basal subcutaneous insulin injection based on IV insulin requirements over the previous 12–18 hours.

- Discontinue continuous IV insulin infusion 2–3 hours after administration of the basal subcutaneous insulin injection.

- Check blood glucose level upon arrival to the general care unit.

- Point-of-care testing can be used, if available.

- Order blood glucose levels four times daily and corrective scale subcutaneous insulin.

- Patients with diabetes using basal insulin therapy pre-operatively.

- Administer basal subcutaneous insulin dose.

- Use home regimen or weight-based calculation to determine total daily dose (TDD).

- For TDD, start at 0.3–0.5 units/kg/day. Typically 50% of TDD is given as basal insulin.

- Discontinue continuous IV insulin infusion 2–3 hours after administration of the subcutaneous dose.

- Order blood glucose level upon arrival to the general care unit.

- Point-of-care testing can be used, if available.

- Order blood glucose levels four times daily and corrective scale subcutaneous insulin.

- In very specific circumstances, it may be appropriate to discharge a patient on a continuous IV insulin infusion to a general care unit.

- An appropriate level of monitoring must exist on the receiving unit.

- A standard continuous IV insulin infusion protocol including hourly blood glucose levels should be ordered.

- Point-of-care testing can be used, if available.

GENERAL CARE AREAS

- For all patients

- The target blood glucose levels.

- Fasting and premeal blood glucose <140 mg/dL.

- Random blood glucose <180 mg/dL.

- Check blood glucose level upon arrival to unit, before meals, and at bedtime or four times per day if NPO.

- Use corrective-scale subcutaneous insulin.

- Give only if at least 2 hours since last subcutaneous PACU dose.

- No dextrose in maintenance IV fluid except for:

- Prolonged NPO status.

- Management of blood glucose level ≤70 mg/dL.

- Required for other medication administration.

- Initiate the treatment of hypoglycemia protocol for blood glucose ≤70 mg/dL or if the patient is symptomatic.

- For patients who are diet-controlled or on oral diabetes medications only:

- Day of surgery (postoperative day [POD]0)

- Order blood glucose level upon arrival to the general care unit.

- Point-of-care testing can be used, if available.

- Order blood glucose levels four times daily and corrective scale subcutaneous insulin upon admission.

- In very specific circumstances, it may be appropriate to discharge a patient on a continuous IV insulin infusion to a general care unit.

- An appropriate level of monitoring must exist on the receiving unit.

- A standard continuous IV insulin infusion protocol including hourly blood glucose levels should be ordered.

- Day after surgery (POD1)

-

Consider starting basal insulin if blood glucose is >180 mg/dL twice in a 24-hour period.

- Use weight-based regimen to calculate the TDD of insulin required.

- For TDD, start at 0.3–0.5 units/kg/day. Typically, 50% of TDD is given as basal insulin.

Introduce prandial insulin if nonfasting blood glucose >180 mg/dL (use weight-based calculation for initial doses).- Prandial insulin would be remaining 50% of TDD calculated above, divided amongst 3 meals.

- Example: type 2 diabetes, normal weight: multiply patient’s weight × 0.4 unit/kg.

- TDD = 80 kg × 0.4 units/kg = 32 units.

- Basal insulin: 16 units.

- Prandial insulin = 16 units/3 meals = 5 units per meal.

- Continue corrective-scale insulin.

- In general, avoid oral hyperglycemic medications in the inpatient setting.

- Oral agents may be considered for use if ALL of the following apply:

- If the patient is well controlled, as indicated by HbA1c <8% on an oral home therapy regimen.

- Eating a stable diabetic diet in the immediate postoperative period.

- Renal and liver function are stable and within acceptable parameters.

- Expected hospital stay is <48 hours.

- No significant source of infection.

- Good control is evident based on hospital blood glucose monitoring.

- If oral agents are utilized, continue corrective-scale subcutaneous insulin as supplemental therapy.

-

For patients pre-operatively on insulin with or without oral medications:

- Day of surgery (POD0)

- Consider administration of evening basal insulin if part of the patient’s home regimen.

- Consider starting prandial insulin regimen as appropriate.

- Use corrective-scale insulin as supplemental therapy.

- Day after surgery (POD1) and beyond

- Consider basal insulin if part of home regimen and not previously ordered or if blood glucose >180 mg/dL twice in a 24-hour period.

- Use weight-based regimen to calculate the TDD of insulin required.

- For TDD, start at 0.3–0.5 units/kg/day. Typically, 50% of TDD is given as basal insulin.

- Consider starting prandial insulin regimen as appropriate.

- Prandial insulin would be remaining 50% of TDD calculated above but divided amongst 3 meals.

- Example: type 2 diabetes, normal weight: multiply patient’s weight × 0.4 unit/kg.

- TDD = 80 kg × 0.4 unit/kg = 32 units.

- Basal insulin: 16 units.

- Prandial insulin = 16 units/3 meals = 5 units per meal.

- Continue corrective-scale subcutaneous insulin as supplemental therapy.

DISCHARGE

- The patient should receive specific education regarding:

- Appropriate diabetic diet or adjustments to diet related to their surgery.

- Any adjustments in their insulin treatment regimen.

- Any adjustment to their oral diabetic medication regimen or interactions with other medications.

- Updated medical reconciliation.

- Frequency of required/recommended blood glucose testing.

- When to notify provider.

- Specific recommendations for diabetes care follow-up.

If patient was started on long-acting insulin (i.e., glargine, levemir, etc.) in the hospital as new therapy but will not continue upon discharge, instruct patient to resume pre-operative diabetic medications 24 hours after the last dose of long-acting insulin given in the hospital.

If patient regularly uses basal insulin as part of home regimen, resume the basal insulin with next scheduled dose or 1 day following discharge.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no multiplicity of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beckles GL, Chou CF. Disparities in the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes -United States, 1999–2002 and 2011–2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1265–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 2015;314:1021–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li C, Balluz LS, Okoro CA, et al. Surveillance of certain health behaviors and conditions among states and selected local areas --Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60:1–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacober SJ, Sowers JR. An update on perioperative management of diabetes. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2405–2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017 Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malone DL, Genuit T, Tracy JK, Gannon C, Napolitano LM. Surgical site infections: reanalysis of risk factors. J Surg Res 2002;103:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston LE, Kirby JL, Downs EA, et al. Postoperative hypoglycemia is associated with worse outcomes after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;103:526–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauruschkat AH, Arnrich B, Albert AA, et al. Prevalence and risks of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation 2005;112:2397–2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmeltz LR, DeSantis AJ, Thiyagarajan V, et al. Reduction of surgical mortality and morbidity in diabetic patients undergoing cardiac surgery with a combined intravenous and subcutaneous insulin glucose management strategy. Diabetes Care 2007;30: 823–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thourani VH, Weintraub WS, Stein B, et al. Influence of diabetes mellitus on early and late outcome after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:1045–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1283–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furnary AP, Zerr KJ, Grunkemeier GL, Starr A. Continuous intravenous insulin infusion reduces the incidence of deep sternal wound infection in diabetic patients after cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:352–360; discussion 360–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furnary AP, Gao G, Grunkemeier GL, et al. Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;125:1007–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroeder SM. Perioperative management of the patient with diabetes mellitus: update and overview. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 2014;31:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umpierrez GE, Hellman R, Korytkowski MT, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non-critical care setting: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:16–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dortch JD, Eck DL, Ladlie B, TerKonda SP. Perioperative glycemic control in plastic surgery: review and discussion of an institutional protocol. Aesthet Surg J 2016;36:821–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson MJ, Patvardhan C, Wallace F, et al. Perioperative management of diabetes in elective patients: a region-wide audit. Br J Anaesth 2016;116:501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boreland L, Scott-Hudson M, Hetherington K, Frussinetty A, Slyer JT. The effectiveness of tight glycemic control on decreasing surgical site infections and readmission rates in adult patients with diabetes undergoing cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Heart Lung 2015;44:430–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawford K Guidelines for care of the hospitalized patient with hyperglycemia and diabetes. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2013;25:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boord JB, Greevy RA, Braithwaite SS, et al. Evaluation of hospital glycemic control at US academic medical centers. J Hosp Med 2009;4:35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levetan CS, Passaro M, Jablonski K, Kass M, Ratner RE. Unrecognized diabetes among hospitalized patients. Diabetes Care 1998;21:246–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg R, Schuman B, Bader A, et al. Effect of preoperative diabetes management on glycemic control and clinical outcomes after elective surgery. Ann Surg 2018;267:858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valgardson JD, Merino M, Redgrave J, Hudson JI, Hudson MS. Effectiveness of inpatient insulin order sets using human insulins in noncritically ill patients in a rural hospital. Endocr Pract 2015;21:794–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Jacobs S, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing general surgery (RABBIT 2 Surgery). Diabetes Care 2011;34:256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold LM, Mahesri M, McDonnell ME, Alexanian SM. Glycemic outcomes 3 years after implementation of a peri-operative glycemic control algorithm in an academic institution. Endocr Pract 2017;23:123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pezzarossa A, Taddei F, Cimicchi MC, et al. Perioperative management of diabetic subjects. Subcutaneous versus intravenous insulin administration during glucose-potassium infusion. Diabetes Care 1988;11:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smiley D, Umpierrez GE, Hermayer K, et al. Differences in inpatient glycemic control and response to subcutaneous insulin therapy between medicine and surgery patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2013;27:637–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]