Abstract

In the present era of modern surgical practice, the incidence of intra-abdominal suture granuloma is extremely rare with reduced use of non-absorbable silk sutures and even rarer following laparoscopic procedures. We report herein a case of silk granuloma presenting as large submucosal polypoidal lesion in a recently operated case of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of stomach. Though endoscopic biopsy showed chronic non-specific gastritis with no evidence of malignancy, our patient underwent excision of lesion due to high likelihood of neoplastic lesion suggested by radiological evaluation and recent history of surgery for GIST but histopathology surprisingly showed Giant cell silk granuloma. In summary, the possibility of suture granulomas should always be considered while evaluating postoperative CT scan/PET scan for a mass lesion at operated site, particularly in patients who have undergone surgery with non-absorbable silk sutures.

Keywords: GIST, Giant cell silk granuloma, Suture granuloma

Introduction

Suture granulomas are persistent foreign body reactions to suture material due to their antigenicity and/or presence of bacterial infection. While any suture material can cause reaction, braided silk and Dacron are the most reactive [1]. Histopathology usually shows distinct aggregates of suture material surrounded by and contained within multinucleated foreign body giant cells. While radiological investigations have been reported as effective modalities in identifying suture granulomas, the diagnosis often rests on the history and histologic findings.

We report herein a case of silk granuloma closely mimicking intramural gastric neoplasm following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for GIST of stomach. Suture granuloma can rarely occur after gastric surgery, especially if non-absorbable suture material is used and may produce a great diagnostic dilemma simulating intramural gastric neoplasm. In the present era of modern surgical practice, the incidence of intra-abdominal suture granuloma is extremely rare with reduced use of non-absorbable silk sutures and even rarer following laparoscopic procedures.

Case report

A 26-year-old male presented to a peripheral hospital with progressive anemia, malena and few episodes of hematemesis over a period of 6 months. Endoscopic evaluation showed large, submucosal polypoidal growth along the greater curvature of stomach with a tiny ulcer at its tip, suggestive of GIST of stomach. With the classical presentation, endoscopic picture and young age of patient, the provisional diagnosis of GIST was made. Laparoscopic-assisted excision of intramural mass was done in Feb 2013. Posterior gastrotomy was done and a 7 × 7 cm submucosal pedunculated mass was found along greater curvature of stomach. Mass was excised by applying endo-GIA staplers. Stay sutures with silk were taken at the ends of gastrotomy and the same was closed by firing three endo-GIA staplers. Histopathology report showed GIST (size-6.0 × 4.0 cm) with low mitotic rate (2/HPF) and CD117 and DOG 1 positivity (Fig. 1). All margins of resection were free of tumor cells.

Fig. 1.

Photomicrograph of GIST stained with H&E showing whorls of spindle cells. Individual cells have elongated nuclei with blunt ends and eosinophilic cytoplasm with mitosis <5/HPF (lower inset picture). Strong positive staining of tumor cells for CD 117 is diagnostic of GIST (upper inset picture)

Six weeks following surgery he presented to us with one episode of hematemesis. Upper GI Endoscopy revealed 5 × 5 cm submucosal polypoidal lesion with congested and edematous overlying mucosa near staple line of previous surgery (Fig. 2a). CECT abdomen showed diffuse irregular polypoidal wall thickening along the anterior wall with patchy intralesional calcification consistent with residual/recurrent GIST (Fig. 2b). WB-PET scan showed metabolically active lesion (SUVmax-7.10) distally along greater curve of stomach (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Evaluation and intraoperative finding of suspected residual gastric lesion in an operated case of gastrointestinal tumor: a endoscopic picture showing 5 × 5 cm polyp-like lesion with severely congested and edematous mucosa, b computed photographic picture showing irregular homogenous mass lesion in anterior wall distally along the greater curvature, c FDG-PET scan—intense focal FDG-avid lesion (SUVmax 7.10) in the stomach wall, d operative picture showing 5 × 4 cm firm polypoidal mass along greater curvature at the lower end of staple line

Though endoscopic biopsy showed chronic non-specific gastritis with no evidence of malignancy, our patient was re-explored due to high likelihood of neoplastic lesion suggested by above mentioned evaluations and recent history of laparoscopic surgery for GIST of stomach with doubtful adequacy of procedure performed at a peripheral centre. Intraoperative findings corroborated with endoscopic picture showing 5 × 4 cm firm polypoidal mass along greater curvature at the lower end of staple line. Wide local excision of gastric lesion was done (Fig. 2d) and histopathology surprisingly did not show any evidence of malignancy, rather showed Giant cell silk granuloma containing multinucleated giant cells with haphazardly arranged nuclei (Fig. 3).

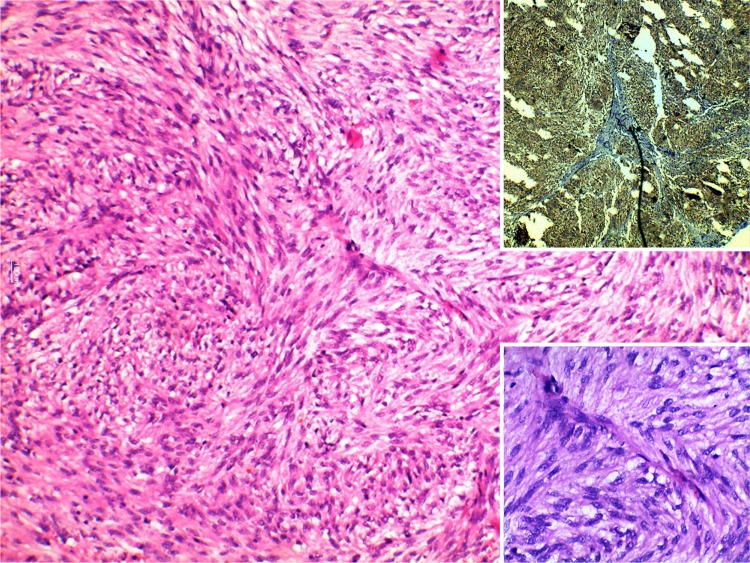

Fig. 3.

Photomicrograph of suspected residual gastric lesion in an operated case of GIST stained with H&E showing dense inflammation comprising lymphocytic cells and formation of giant cell granuloma with evidence of silk suture in the centre. This figure shows entire granulomatous reaction at 10x (low power). Upper inset silk sutures at higher magnification; lower inset multinucleated foreign body giant cells

Discussion

Silk sutures are non-absorbable yarn which has a particularly high incidence of granuloma formation of 0.6–7.1 % [2, 3]. In our knowledge, no case of suture granuloma following laparoscopic procedures has been reported in literature. Suture granulomas are more commonly seen with surface surgeries compared to visceral surgeries. While suture granuloma following surface surgery occurs early and is usually caused by infection, intra-abdominal suture granuloma is usually of late onset and the cause is not well understood [4]. If at risk group can be ascertained preoperatively, one can selectively use absorbable sutures in these patient and continue to use non-absorbable sutures in those without risk factors making it a cost-effective approach. But unfortunately, no definite risk factors for formation of suture granuloma with non-absorbable suture materials have yet been identified.

Literature review on PubMed with key words ‘intra-abdominal suture granuloma’ and ‘post gastrectomy suture granuloma’ revealed that most of the cases of intra-abdominal suture granuloma have been reported before 1990s [5, 6] with very occasional reports in modern practice, probably because of reduced use of silk sutures. Most of the reported cases of intra-abdominal granuloma were of late onset. This case is unique because of rapid development of submucosal gastric lesion following surgery, very closely simulating residual/recurrent lesion. Though endoscopy in this case showed severely congested and edematous mucosa overlying the lesion suggesting inflammatory polypoid lesion, computed tomography and even FDG-PET scan were highly suspicious of residual/recurrent lesion. Suspicion was further potentiated by a known setting of recently operated GIST at peripheral centre and minimal invasive approach of surgery.

Findings of CT scan, MRI and other morphologic examinations of suture granuloma are non-specific [7] and quite variable. Needle cytology/biopsy may be effective for diagnosis for suture granuloma but it is not sufficiently reliable and could lead to false-positive diagnosis of tumor recurrence or may be suggestive of chronic non-specific inflammation only, as in our case. Thus, many times, excisional biopsy is necessary for accurate differentiation from neoplastic lesion.

PET scan is nowadays commonly used to differentiate between non-neoplastic and neoplastic pathology but very often it is non-contributory. Suture granulomas with a high FDG accumulation as in our case (SUVmax-7.1) are often difficult to differentiate from neoplastic lesion. It has been found that FDG accumulation in suture granuloma presents a uniform pattern [8–11] while residual gauze [12] or surgical sponge [13] shows no FDG accumulation inside foreign body and presents a ring pattern.

In this case, several points need to be emphasized. CT scan in our case showed homogenous mass with patchy calcification, should it have been a GIST, it should have shown heterogeneity because of necrosis and hemorrhage with peripheral enhancement, though these typical findings are more consistent with larger size of GIST.

Upper GI endoscopy in GIST shows smooth mucosa-lined protrusion of stomach wall with endophytic growth causing inaccurate assessment of extent and can also make procurement of diagnostic tissue by endoscopy more difficult [14]. In our case, there were endoscopic signs of inflammatory lesion and subsequently biopsy also showed chronic non-specific gastritis. With this non-contributory endoscopy and biopsy, EUS-guided biopsy from lesion should have been tried before re-exploration but recent history of surgery for GIST and that too with minimal invasive approach at peripheral centre added the strong suspicion of residual/recurrent lesion and hence re-exploration was done.

Conclusion

This report emphasizes that although the appearance of lesion may be typical of malignancy, the possibility of suture granuloma should be born in mind especially if lesion appears shortly after surgery. The possibility of suture granulomas should always be considered when evaluating postoperative FDG-PET, particularly in patients who underwent surgery with non-absorbable sutures and unnecessary major surgery can thus be avoided. Judicious use of silk may help to decrease the occurrences of suture granulomas as well as other known complications related to non-absorbable sutures such as suture line ulcers, abscesses and adhesions.

Conflict of interest

The authors and co-authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Santosh Kumar Singh, Phone: +918826272421, Email: mlnsantosh@yahoo.co.in.

Narayan Kannan, Email: dr.n.kannan@hotmail.com.

Rajnish Talwar, Email: rajnish_onco@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Lo Cicero J, Robbins JA, Webb WR. Complications following abdominal fascial closures using various nonabsorbable sutures. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1983;157:25–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagar H. Stitch granulomas following inguinal herniotomy: a 10-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1505–1507. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(93)90442-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwase K, Higaki J, Tanaka Y, Kondoh H, Yoshikawa M, Kamiike W. Running closure of clean and contaminated abdominal wounds using a synthetic monofilament absorbable looped suture. Surg Today. 1999;29:874–879. doi: 10.1007/BF02482778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imamoglu M, Cay A, Sarihan H, Ahmetoglu A, Ozdemir O. Paravesical abscess as an unusual late complication of inguinal hernia repair in children. J Urol. 2004;171:1268–1270. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000113037.59758.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belleza NA, et al. Suture granuloma of stomach following total colectomy. Radiology. 1978;127:84. doi: 10.1148/127.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders I, Woesner ME, et al. ‘stitch’ granuloma: a consideration in the differential diagnosis of intramural gastric tumor. Am J Gastroenterol. 1972;57(6):558–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SW, Shin HC, Kim IY, Baek MJ, Cho HD. Foreign body granulomas simulating recurrent tumors in patients following colorectal surgery for carcinoma: a report of two cases. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:313–318. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2009.10.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu¨ksel M, Akgu¨l AG, Evman S, Batirel HF (2007) Suture and stapler granulomas: a word of caution. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 31:563–5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Chung YE, Kim EK, Kim MJ, Yun M, Hong SW. Suture granuloma mimicking recurrent thyroid carcinoma on ultrasonography. Yonsei Med J. 2006;47:748–751. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2006.47.5.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim JW, Tang CL, Keng GH. False positive F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose combined PET/CT scans from suture granuloma and chronic inflammation: report of two cases and review of literature. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:457–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SW, Shin HC, Kim IY, Baek MJ, Cho HD. Foreign body granulomas simulating recurrent tumors in patients following colorectal surgery for carcinoma: a report of two cases. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:313–318. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2009.10.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen MY, Ng KK, Ma SY, Wu TI, Chang TC, Lai CH. False positive fluorine-18 fluorodeoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography imaging caused by retained gauze in a woman with recurrent ovarian cancer: a case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2005;26:451–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakajo M, Jinnouchi S, Tateno R, Nakajo M. 18F-FDG PET/CT findings of a right subphrenic foreign-body granuloma. Ann Nucl Med. 2006;20:553–556. doi: 10.1007/BF03026820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pidhorecky I, Cheney RT, Kraybill WG, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: current diagnosis, biologic behavior, and management. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:705. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]