Abstract

Rationale: Distant metastasis and chemoresistance are the major causes of short survival after initial chemotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma patients. However, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Our pilot study identified high expression of the homeodomain transcription factor HOXB13 in chemoresistant lung adenocarcinomas. We aimed to investigate the role of HOXB13 in mediating lung adenocarcinoma chemoresistance.

Methods: Immunohistochemistry assays were employed to assess HOXB13 protein levels in 148 non-small cell lung cancer patients. The role of HOXB13 in lung adenocarcinoma progression and resistance to cisplatin therapy was analyzed in cells, xenografted mice, and patient-derived xenografts. Needle biopsies from 15 lung adenocarcinoma patients who were resistant to cisplatin and paclitaxel therapies were analyzed for HOXB13 and EZH2 protein levels using immunohistochemistry.

Results: High expression of HOXB13 observed in 17.8% of the lung adenocarcinoma patients in this study promoted cancer progression and predicted poor prognosis. HOXB13 upregulated an array of metastasis- and drug-resistance-related genes, including ABCG1, EZH2, and Slug, by directly binding to their promoters. Cisplatin induced HOXB13 expression in lung adenocarcinoma cells, and patient-derived xenografts and depletion of ABCG1 enhanced the sensitivity of lung adenocarcinoma cells to cisplatin therapy. Our results suggest that determining the combined expression of HOXB13 and its target genes can predict patient outcomes.

Conclusions: A cisplatin-HOXB13-ABCG1/EZH2/Slug network may account for a novel mechanism underlying cisplatin resistance and metastasis after chemotherapy. Determining the levels of HOXB13 and its target genes from needle biopsy specimens may help predict the sensitivity of lung adenocarcinoma patients to platinum-based chemotherapy and patient outcomes.

Keywords: HOXB13, metastasis, cisplatin resistance, prognosis, lung adenocarcinoma

Introduction

Metastasis and drug resistance are the major causes of chemotherapeutic failure and death in lung adenocarcinoma patients. After five years, chemotherapy decreased lung cancer patient death by only 4% when compared to an untreated control group 1. Thus, identifying new biomarkers that predict lung cancer metastasis and chemoresistance would improve the outcome in lung adenocarcinoma patients.

HOXB13, mainly expressed in the tail bud during human embryonic development 2, is known to be a prostate-lineage-specific transcription factor, with key roles in prostate cancer progression. It downregulates intracellular zinc and increases NF-κB signaling to promote prostate cancer metastasis, and regulates the cellular response to androgens 3, 4. HOXB13 was found to be localized with FOXA1 at reprogrammed AR sites in human tumor tissues and was also shown to reprogram the AR cistrome in an immortalized prostate cell line that resembles prostate tumors 5. A decisive role for HOXB13 was also reported in susceptibility to prostate cancer 6. The protein functionally promotes CIP2A transcription by binding to the CIP2A gene, and the presence of both the HOXB13 T and CIP2A T alleles confers a high risk of PrCa and aggressiveness of the disease 7.

HOXB13 was shown to function as a tumor suppressor in colorectal and renal cancers 8 but was oncogenic with high expression in breast 9, hepatocellular 10, ovarian, and bladder carcinomas 11. However, the role of HOXB13 in lung cancer is still unknown.

Recently, the ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 (ABCG1) was implicated as a potential oncogene in lung cancer. ABCG1 is a member of the ABC transporter family that regulates cellular cholesterol transport and homeostasis 12-17, and has also been shown to promote proliferation, migration, and invasion in HKULC4 lung cancer cells 18. Furthermore, genetic variants of ABCG1 were linked to the survival of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients 19. These finding suggested that ABCG1 may play a role in NSCLC progression. However, ABCG1 was not shown to be involved in chemoresistance in these patients.

EZH2, a component of the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), is a histone methyltransferase that trimethylates histone 3 at lysine 27. EZH2 promotes tumor progression by increasing DNA methylation and inactivating tumor suppressor genes 20, 21. It is well established that EZH2 promotes cell proliferation by enhancing cell cycle progression 22 and promotes migration and metastasis by activating VEGF/Akt signaling in NSCLC cells 23. Recently, enhanced EZH2 was detected in lung cancer cells that were resistant to cisplatin, the first-line treatment regimen for advanced NSCLC 24. EZH2 also confers drug resistance in docetaxel-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cells 25. Low expression of EZH2 is associated with better responses to chemotherapy and improved survival rates 26.

In this study, we described the relationship between HOXB13 and the clinical stage, invasion, metastasis, drug resistance, and patient prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. A series of genes targeted by HOXB13 were analyzed, including the ABCG1, EZH2, and Slug genes. Most importantly, we found that the expression of HOXB13 was induced by cisplatin therapy. These findings provide a method for evaluating HOXB13 and its target genes to predict drug resistance and patient prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Our study has identified an important molecular mechanism that underlies metastasis and drug resistance in NSCLC induced by chemotherapy.

Methods

Ethics

The Ethics Committee of Peking University Health Science Center has approved the mouse experiments (Permit Number: LA2017-008) and the use of tissue from human lung adenocarcinoma patient tumors (Permit Number: ZRLW-5) for this study. The handling of mice and human tumor specimens was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and the revised version in 1983. We also referred to the procedures by Workman et al. 27.

Patient tumor samples

To study the role of HOXB13 in NSCLC, we obtained samples from 73 lung adenocarcinoma patients and 75 squamous cell lung cancer patients who had not been treated with neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies before surgery and had undergone surgery at Peking University Health Science Center between July 2006 and September 2007. The "normal lung tissue samples” (n = 148) were obtained from the same patients and were at least 3 cm away from the tumor tissue. The detailed clinicopathological characteristics of lung adenocarcinoma patients are summarized in Table 1. Survival was measured for patients from the time of surgery, with death as the endpoint. Overall survival was analyzed until August 2013. The median observation time for overall survival was 40 months (range, 2-89 months). At the follow-up, 24 patients had died, 32 patients were still alive and censored, and the statuses of the remaining patients were unknown.

Table 1.

Relationship between HOXB13 Expression and Various Clinicopathological Factors in Lung Adenocarcinoma Patients (n=73).

| Expression of HOXB13 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | P value | |||||

| 28 | 38.36% | 32 | 43.84% | 12 | 16.44% | 1 | 1.37% | ||||

| Age, yrs 61(37-84) | 0.3214 | ||||||||||

| <=60 | 34 | 46.58% | 12 | 16.44% | 14 | 19.18% | 7 | 9.59% | 1 | 1.37% | |

| >60 | 39 | 53.42% | 16 | 21.92% | 18 | 24.66% | 5 | 6.85% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Sex | 0.7462 | ||||||||||

| Male | 39 | 53.42% | 12 | 16.44% | 21 | 28.77% | 5 | 6.85% | 1 | 1.37% | |

| Female | 34 | 46.58% | 13 | 17.81% | 16 | 21.92% | 5 | 6.85% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| TNM category | |||||||||||

| T1 | 19 | 26.03% | 8 | 10.96% | 1 | 1.37% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.0022 |

| T2a | 41 | 56.16% | 16 | 21.92% | 20 | 27.40% | 5 | 6.85% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| T2b | 5 | 6.85% | 2 | 2.74% | 1 | 1.37% | 2 | 2.74% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| T3 | 13 | 17.81% | 2 | 2.74% | 7 | 9.59% | 3 | 4.11% | 1 | 1.37% | |

| T4 | 5 | 6.85% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 4.11% | 2 | 2.74% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| N0 | 36 | 49.32% | 20 | 27.40% | 13 | 17.81% | 2 | 2.74% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.0019 |

| N1 | 17 | 23.29% | 5 | 6.85% | 8 | 10.96% | 4 | 5.48% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| N2 | 16 | 21.92% | 3 | 4.11% | 8 | 10.96% | 4 | 5.48% | 1 | 1.37% | |

| N3 | 5 | 6.85% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 4.11% | 2 | 2.74% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| M0 | 68 | 93.15% | 28 | 38.36% | 29 | 39.73% | 10 | 13.70% | 1 | 1.37% | 0.6631 |

| M1 | 5 | 6.85% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 4.11% | 2 | 2.74% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| AJCC | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| I | 27 | 36.99% | 18 | 24.66% | 9 | 12.33% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| II | 16 | 21.92% | 6 | 8.22% | 8 | 10.96% | 2 | 2.74% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| III | 25 | 34.25% | 4 | 5.48% | 12 | 16.44% | 8 | 10.96% | 1 | 1.37% | |

| IV | 5 | 6.85% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 4.11% | 2 | 2.74% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Differentiation | 5 | 6.85% | 9 | 12.33% | 2 | 2.74% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.2507 | ||

| Low differentiation | 17 | 23.29% | 5 | 6.85% | 9 | 12.33% | 3 | 4.11% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Low-Moderate differentiation | 19 | 26.03% | 7 | 9.59% | 9 | 12.33% | 3 | 4.11% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Moderate differentiation | 26 | 35.62% | 11 | 15.07% | 11 | 15.07% | 4 | 5.48% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Moderate-high differentiation | 7 | 9.59% | 2 | 2.74% | 2 | 2.74% | 2 | 2.74% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| High differentiation | 4 | 5.48% | 3 | 4.11% | 1 | 1.37% | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| Vascular invasion | 0.8441 | ||||||||||

| Negative | 69 | 94.52% | 26 | 35.62% | 31 | 42.47% | 11 | 15.07% | 1 | 1.37% | |

| Positive | 4 | 5.48% | 2 | 2.74% | 1 | 1.37% | 1 | 1.37% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Lymphatic | 0.3396 | ||||||||||

| Negative | 64 | 87.67% | 26 | 35.62% | 28 | 38.36% | 11 | 15.07% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Positive | 9 | 12.33% | 2 | 2.74% | 4 | 5.48% | 1 | 1.37% | 1 | 1.37% | |

| Alive | 32 | 43.84% | 14 | 19.18% | 15 | 20.55% | 3 | 4.11% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Dead | 24 | 32.88% | 8 | 10.96% | 9 | 12.33% | 6 | 8.22% | 1 | 1.37% | |

| Not known | 17 | 23.29% | 6 | 8.22% | 8 | 10.96% | 3 | 4.11% | 0.00% | ||

Lung adenocarcinoma tumor tissue samples were also obtained from 15 patients of the Cancer Hospital Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences between July 2004 and April 2006. The samples were taken by needle biopsy before chemotherapy. These 15 patients were then accepted for cisplatin and paclitaxel combination treatment. Recurrence for the patients was measured from the time of chemotherapy, and the recurrence and/or metastasis occurring within 6 months was considered a sign of drug resistance. Among these patients, 9 exhibited drug resistance and 6 exhibited chemotherapy drug sensitivity.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and assessment

Tissue sections from lung adenocarcinoma tumors were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. IHC and assessments were performed as previously described 28. Briefly, deparaffinization and hydration were performed followed by abolishing endogenous peroxidase activity using 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min, and then microwaved for antigen retrieval in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min. HOXB13 antibody (Santa Cruz, SC-28333, USA) and EZH2 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 30233s, USA) were used at 2 µg/ml in all experiments, and incubated at 4 °C overnight followed by the PV-9000 2-step plus Poly-HRP anti-Mouse/Rabbit IgG Detection system (Zhong Shan Jin Qiao, China). The streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method was used for detection with 3'3'-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride as the substrate (D0430, Amresco, USA). Counterstaining was performed using hematoxylin. Negative controls were prepared by replacing the primary antibody with normal rabbit serum.

Pathologists Huiying He and Peng Wang evaluated all immunostainings independently; the discussions leading to consensus and justification of the decisions were recorded. The results were classified into four grades: no reactivity marked as 0, faint reactivity as 1+, moderate reactivity as 2+, and strong reactivity as 3+, with 0 representing no expression. Student t-test analyses were performed to compare the HOXB13 level between different lung adenocarcinoma clinical pathological groups.

Expression vectors, cell culture, and gene transfections

The full-length cDNA of HOXB13 was cloned from human placenta cDNA library using primers ATGGAGCCCGGCAATTATGCCACC (forward primer) and TTAAGGGGTAGCGCTGTTCTT (reverse primer). The PCR product was cloned into the PCRII vector, and then further cloned into the pCMV10-3×Flag vector (Sigma) using EcoRI-XhoI sites. The H1299, A549, and A549DDP cell lines were purchased from the Research Facilities of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (http://www.crcpumc.com/). All cell lines were tested and authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling (DNA fingerprinting) 29 within 6 months of the study and routinely tested for Mycoplasma species before any experiments were performed. Details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared, and the equivalent amounts of protein were detected using the appropriate primary antibodies. Details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Cell motility and cell invasion assays

Transwell chambers (Costar) with 8 µm pore size were used to perform the cell migration assay. H1299 and A549 cells stably transfected with Flag-BAP (bacterial alkaline phosphatase, Flag-HOXB13, or HOXB13 siRNA were seeded on the upper surface of the Transwell. After 6 h incubation in migration buffer (RPMI1640, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM MnCl2, and 0.5% BSA) at 37 °C in humidified 5% CO2, the Transwell membranes were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min and stained with crystal violet for 10 min. Six microscopic fields were then randomly chosen for counting the migrated cells. The invasion assay was performed by adding Matrigel to the upper surface of the Transwell membrane before adding cells followed by 12 h incubation. Sequences of RNA interference (RNAi) oligonucleotides used for knockdown of endogenous proteins are presented in the Supplementary Methods.

In vivo xenograft tumor growth and metastasis experiments

In Balb/c nude mice, 1×106 cells, with stable and separate overexpression of HOXB13 and the control vector, were implanted subcutaneously into the flank. The size of the tumors was measured every 3 days and at additional times as indicated. Tumors were sectioned, removed, and weighted at day 28 when they were approximately 1 cm in diameter and the mice were kept alive until they were euthanized at day 56. At that time, in situ recurrences and metastasis were measured.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Trizol was used to isolate total cellular mRNAs and M-MLV reverse transcriptase was used to transcribe 2 µg of total RNA (Promega, CA, USA), which was then examined by PCR. The details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

ChIP assay

To test the direct targeting role of HOXB13 on the candidate genes, ChIP assays were performed as described in the Supplementary Methods.

Luciferase assay

The EZH2 promoter plasmid was a generous gift from Professor Gerhard Christofori. Genomic DNA was extracted from 293T cells. The genomic DNA and the EZH2 promoter plasmid were used as templates to clone the ABCG1, EZH2, and HOXB13 promoters. The promoters were then cloned into the pGL4.21 luciferase vector (Promega). The design of the corresponding primer is described in the Supplementary Methods.

H1299 cells were seeded in 24-well plates 1 day before transfection. The cells were co-transfected with 200 ng of the pGL promoter plasmid, 5 ng of the Renilla plasmid and 200 ng of either the Flag plasmid, Flag-HOXB13 plasmid, or siRNA using either the Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) or Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were harvested 48 h or 72 h after transfection. The reporter activity was measured using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) with a GloMax 20/20 Luminometer.

Drug resistance test in vivo

Male Balb/c nude mice were randomly divided into four groups (n = 6 per group). In two groups, 2 × 106 cells stably overexpressing Flag-HOXB13 were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of the mice and cells overexpressing the control Flag vector were implanted in the other two groups. Drugs were administered to the mice on the 28th day of tumor growth. One Flag control group and one Flag-HOXB13 group were intraperitoneally injected with cisplatin (5 mg/kg) or paclitaxel (15 mg/kg) three times a week. PBS was used as a control for the remaining two groups. Tumors were measured every 3 days for the indicated time. Tumor volumes were determined using the following formula: tumor volume = a2 * b/2, where a = short diameter (cm) and b = long diameter (cm). The tumors were sectioned after the mice were sacrificed.

PDX model and cisplatin resistance assay

Human lung adenocarcinoma specimens for the (patient-derived xenograft) PDX model were kind gifts from Dr. Wei Guo of Tsinghua University. Subcutaneous xenograft tumors of about 400 mm3 were treated intraperitoneally with 3 mg/kg cisplatin every other day 30. After 10 days of treatment, tumors were fixed with 4% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned.

Statistical analysis

Student t-test, Chi-square, Fisher's exact test, and Spearman's correlation coefficient were used to analyze the correlation between HOXB13 expression and clinical pathology of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS14.0. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier analysis and curves were compared using the log-rank test. The K-M plot survival analysis tool used in this study was accessed online at http://kmplot.com/analysis/. Results with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

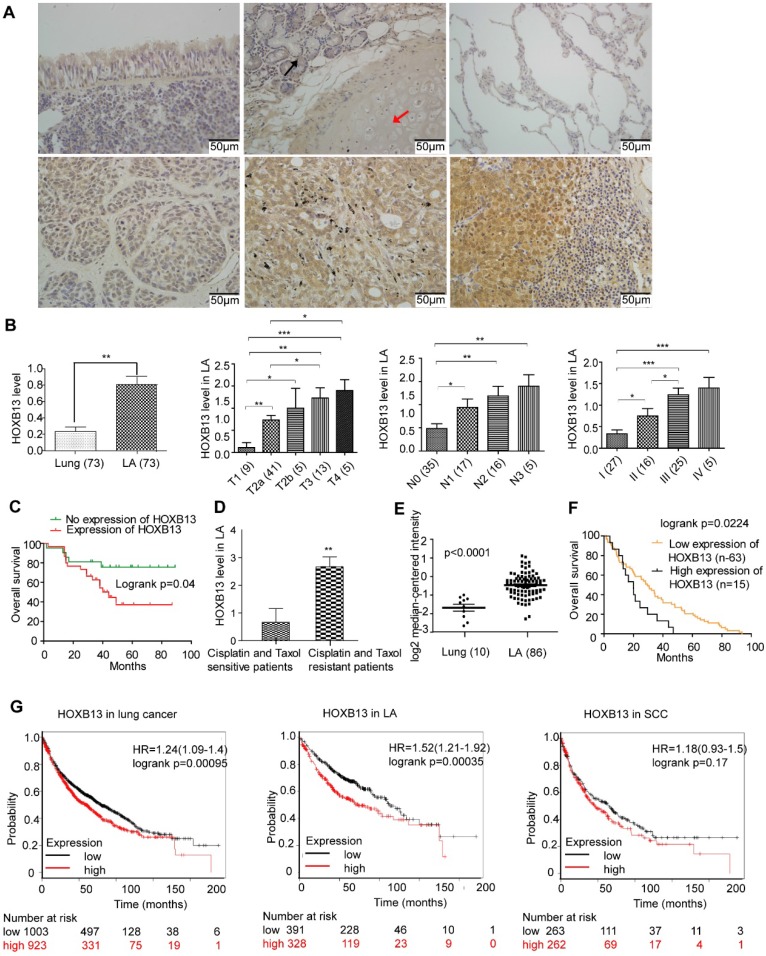

HOXB13 is involved in lung adenocarcinoma but not in SCC progression

HOXB13 has been implicated in the progression of prostate cancers 31. However, no report has yet linked HOXB13 with lung cancer progression. We first examined the expression of HOXB13 in tumor samples from lung cancer patients using IHC analysis. Normal lung tissues expressed very little or no HOXB13, but its expression was significantly increased in lung adenocarcinomas (Figure 1A) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) (Figure. S1A and B). Semi-quantitative analysis of HOXB13 expression showed a positive correlation with the T grade, N grade, AJCC grade (Figure 1B; Table 1) and survival (Figure 1C) in lung adenocarcinoma patients but not in SCC patients (Figure S1B). Intriguingly, we found that HOXB13 was highly expressed in lung adenocarcinoma patients who were resistant to cisplatin or paclitaxel therapy (Figure 1D). Furthermore, the Oncomine lung cancer and Beer Lung datasets also showed that HOXB13 gene expression was increased in lung adenocarcinoma tumor tissues compared with normal lung tissues (Figure 1E) and predicted poor patient survival (Figure 1F) 32. Also, the K-M plot analysis showed a correlation between increased HOXB13 expression and a poor patient outcome in lung adenocarcinoma but not in SCC (Figure 1G). Results from GSE14814 and GSE17710 datasets also supported a strong correlation between elevated levels of HOXB13 and clinical outcomes in patients with lung cancer (Figure S1C). These findings indicated that HOXB13 is overexpressed in lung adenocarcinoma and may regulate its progression.

Figure 1.

HOXB13 is overexpressed in high clinical grade and associated with chemoresistance and patient outcome in lung adenocarcinoma. (A) Expression of HOXB13 in tumor tissues from lung cancer patients by IHC analysis. Upper panel left: Low level of HOXB13 expressed in the pseudo-stratified epithelium. Upper panel middle: Low HOXB13 expression in tracheal gland (black arrow) and transparent cartilage (red arrow). Upper panel right: No HOXB13 expression in normal lung tissue. Lower panel left: Low HOXB13 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. Lower panel middle: High HOXB13 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. Lower panel right: High HOXB13 expression in lymph node metastasized tumor tissue of lung adenocarcinoma. (B) Semi-quantitative analysis of HOXB13 levels in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Unpaired Student's t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) analyses were performed to compare the HOXB13 level between different lung adenocarcinoma clinical pathological groups. Increased HOXB13 positively correlated with lung adenocarcinoma patients' progression. (C) Increased HOXB13 expression correlates with poor overall survival in lung adenocarcinoma patients as determined by K-M analysis (p < 0.05, log-rank). (D) HOXB13 is high in cisplatin- and paclitaxel-resistant patients (n=6) compared with that in the sensitive patients (n=9) (Lower panel the second). (E) HOXB13 expression is increased in lung adenocarcinoma in an Oncomine Beer Lung cancer dataset (Unpaired Student's t-test, p < 0.0001) (F) Elevated mRNA expression of HOXB13 correlates with poor overall survival in patients from the Oncomine Beer lung dataset determined by K-M plot analysis (p < 0.05, log-rank). (G) High expression of HOXB13 predicts poor outcome in lung adenocarcinoma patients by K-M plot analysis.

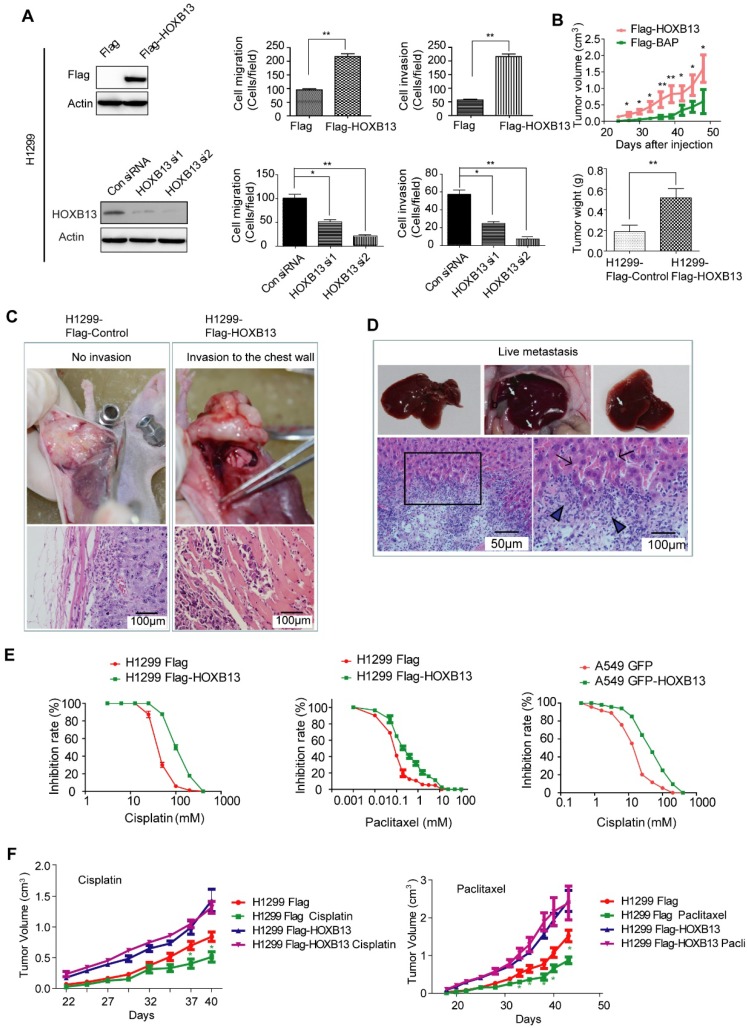

HOXB13 promotes lung adenocarcinoma cell migration, invasion, growth and confers chemoresistance both in vitro and in vivo

Given that HOXB13 is highly expressed in patients resistant to chemotherapy, we next investigated the role of HOXB13 in drug resistance of lung adenocarcinoma cells. In a gain-of-function experiment, the overexpression of HOXB13 promoted cell migration and invasion. In contrast, a loss-of-function experiment performed by knocking down the endogenous expression of HOXB13 in lung adenocarcinoma cells using small interference RNAs (siRNAs) showed inhibition of cell migration and invasion (Figure 2A and S2A and B). Furthermore, the effect of HOXB13 on lung adenocarcinoma cell growth was examined by plate colony formation and WST-1 cell proliferation assays in both H1299 and A549 cells (Figure S2C). The results showed that HOXB13 promotes lung adenocarcinoma cell growth.

Figure 2.

HOXB13 promotes lung adenocarcinoma cell migration, invasion, and chemoresistance in vitro and in vivo. (A) HOXB13 promoted migration and invasion in H1299 cells. Upper panel: H1299 cells were stably transfected with Flag-HOXB13 and Flag empty vector as a control. Expression of Flag-HOXB13 was confirmed by Western blot analysis using the Flag antibody. HOXB13 effect on cell migration and invasion was determined in the Transwell assay by comparing H1299 cells stably expressing HOXB13 with the Flag control. Lower panel: Western blot analysis showed that HOXB13 was knocked down by two HOXB13 siRNAs in H1299 cells. H1299 cell migration and invasion was measured in the Transwell assay after HOXB13 depletion (Unpaired Student's t-test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (B) HOXB13 promotes tumor formation in nude mice. 1×106 H1299 cells stably expressing Flag-HOXB13 or control vector were inoculated into the flank of nude mice. At day 28, tumors were dissected and photographed. The mice were then maintained for 28 days. Tumor growth curve for Flag-HOXB13 cells and the control cells. The average of tumor weights at the endpoint. (Unpaired Student's t-test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). (C) HOXB13 promotes local invasion of the tumor in vivo. No obvious chest invasion for the control-H1299 cells (invasion: 0/6). Chest invasion was observed for HOXB13-H1299 cells. Local invasion into the adjacent muscle was observed by histological analysis for HOXB13-H1299 cells (invasion: 2/6). (D) HOXB13 promotes lung adenocarcinoma cell liver metastasis. Upper panel left: Liver with no observed metastasized tumor. Upper panel middle and right: Liver with obviously metastasized tumors. Arrows: metastasized tumor foci. Lower panel left: Metastasized lung adenocarcinoma cells observed by histological analysis. Lower panel right: Enlarged area of the boxed region. This region is the boundary between the normal liver tissue (arrowed) and the metastasized lung adenocarcinoma cells (Arrowhead). (E) High expression of HOXB13 induced drug resistance in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Left: Drug resistance curve for enhanced expression of HOXB13 promotes A549 cell resistance to cisplatin in a WST-1 cell viability assay. Middle: Drug resistance curve for enhanced expression of HOXB13 promotes H1299 cell resistance to cisplatin. Right: Drug resistance curve for enhanced expression of HOXB13 promotes H1299 cell resistance to Paclitaxel. (F) HOXB13 promotes drug resistance to cisplatin and paclitaxel in nude mice. Left: Tumor growth curves of H1299 Flag and H1299 Flag-HOXB13 groups with or without cisplatin treatment. Cisplatin (5 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally injected three times a week from day 28 after cell inoculation. Right: Tumor growth curve of H1299 Flag and H1299 Flag-HOXB13 cells with or without paclitaxel therapy. Paclitaxel (15 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally injected three times a week from day 28 after cell inoculation. Green stars indicate H1299 Flag cell-derived tumor sensitivity to therapy and volume decrease at the indicated time after treatment. Treatment had no effect on the growth of tumors from H1299 Flag-HOXB13 cells (Unpaired Student's t-test,*p < 0.05).

We then examined the in vivo role of HOXB13. To this end, H1299 cells stably overexpressing Flag-HOXB13 or A549 cells stably overexpressing GFP-HOXB13 were inoculated into nude mice as previously described 33. Tumor xenografts grew faster and larger (Fig. 2B; Fig. S2D) in the groups that were overexpressing HOXB13 compared to the control groups. Tumors with high HOXB13 expression displayed greater potential for local invasion (increasing from 0/6 to 2/6) (Figure 2C), and liver metastasis (increasing from 2/6 to 6/6) (Figure 2D). Furthermore, A549 cells stably transfected with HOXB13 showed an increase in the expression of the cell proliferation marker Ki67 (Figure S2E) and exhibited poor survival rates in mice (Figure S2F). Thus, we concluded that HOXB13 promotes lung adenocarcinoma cell growth, local invasion, and metastasis to the liver in nude mice.

As HOXB13 is highly expressed in patients who are resistant to chemotherapy, we next investigated the role of HOXB13 in drug resistance of lung adenocarcinoma cells. To this end, H1299 and A549 cells were examined for their sensitivity to cisplatin and paclitaxel, which are front line chemotherapeutic drugs for a variety of cancers. H1299 cells stably overexpressing Flag-HOXB13 exhibited resistance to cisplatin at a higher half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50 = 102.7 µM) than the control cells (IC50 = 40.57 µM) and resistance to paclitaxel with the IC50 increasing from 0.08 µM to 0.2668 µM. Similar results were obtained in A549 cells with the IC50 increasing from 12.7 µM to 40.47 µM (Figure 2E). The dose and time curves by WST-1 assay are shown in Figure S3A.

Lung adenocarcinoma resistance to chemotherapy was also found in xenograft tumors. Cisplatin and paclitaxel inhibited the growth of H1299 cells in vivo, whereas HOXB13-overexpressing H1299 cells were resistant to cisplatin and paclitaxel treatments (Figure 2F). These findings indicated that HOXB13 confers chemoresistance to lung adenocarcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo.

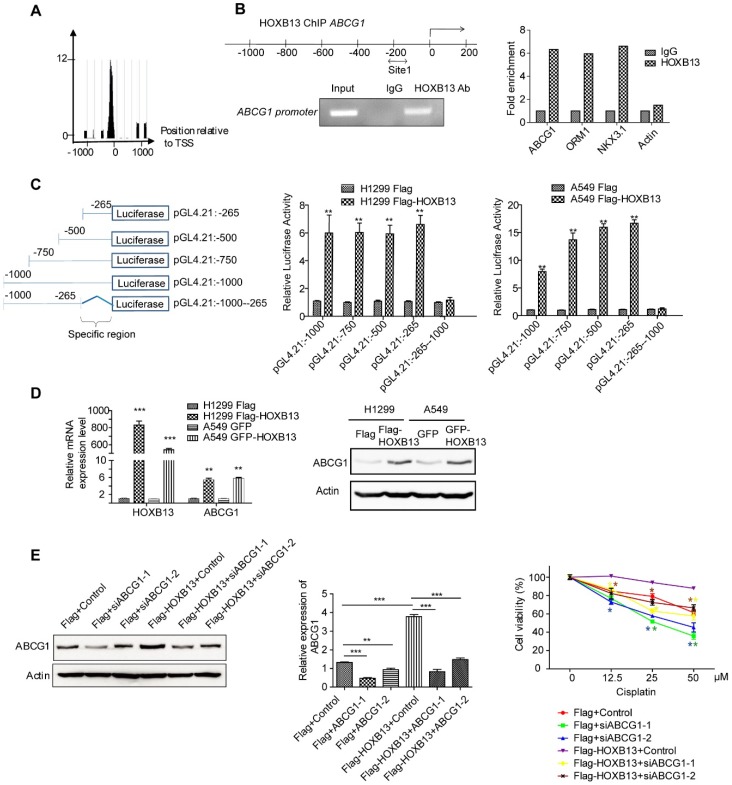

HOXB13 induces chemoresistance by upregulation of ABCG1 via direct binding to its promoter

ABCG1 has been linked to non-small cell lung cancer survival 19. Therefore, we examined whether ABCG1 was regulated by HOXB13 and involved in chemoresistance in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Using ChIP-seq analysis, we examined the binding of HOXB13 to the ABCG1 promoter and its effect on ABCG1 expression (Figure 3A). The presence of HOXB13 was confirmed using an anti-HOXB13 antibody; ORM1 and NKX3.1 were used as positive controls (Figure S3B) and actin as a negative control (Figure 3B). The results showed that HOXB13 was specifically enriched on the ABCG1 promoter. To assess whether HOXB13 can transcriptionally activate ABCG1 gene expression, a series of ABCG1 promoter regions were amplified by PCR and fused with the pGL4.21 luciferase reporter vector. Co-transfection experiments showed that HOXB13 significantly increased the activity of the ABCG1 promoter-luciferase reporter and that constructs of different promoter regions induced reporter activation compared with the empty vector (Figure 3C) indicating 0∼-265 region from TSS to be the specific binding site of ABCG1 promoter for HOXB13. Furthermore, in lung adenocarcinoma cells, HOXB13 expression correlated with the upregulation of ABCG1 at both mRNA and protein levels (Figure 3D). These findings indicated HOXB13 directly binds to the ABCG1 promoter and upregulates its expression in lung adenocarcinoma cells.

Figure 3.

HOXB13 induces chemoresistance by targeting and upregulating ABCG1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma cells. (A) Enrichment of HOXB13 on the ABCG1 promoter analyzed by the ChIP-seq database from prostate cancer 37. (B) Left: Diagram of regions in the ABCG1 promoter with HOXB13 binding sites (double arrow). Gel image of ChIP analysis for HOXB13 occupancy on the ABCG1 promoter. Right: ChIP analysis was performed using either an anti-HOXB13 ChIP-grade antibody or control IgG in Flag-HOXB13 H1299 cells. Enrichment of Site 1 in the ABCG1 promoter was analyzed by qPCR with known target genes of HOXB13 (ORM1 and NKX3.1) as positive controls and actin as a negative control. (C) Left: Construct maps of ABCG1 promoter-luciferase reporter. Middle: Luciferase reporter activity of each construct co-transfected with vector or HOXB13, towards the identification of a 265bp upstream region critical for HOXB13-directed enhancement (Unpaired Student's t-test, **p < 0.01) in H1299. Right: Luciferase reporter activity of each construct cotransfected with vector or HOXB13 in A549 cells. (D) HOXB13 upregulates ABCG1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma cells. H1299 and A549 cells were transiently transfected by Flag-HOXB13 or GFP-HOBX13 separately and transiently transfected Flag and GFP were used as controls, respectively. Left: Quantitative PCR was performed to identify that HOXB13 upregulates ABCG1 transcriptionally. Right: Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analyses using an anti-ABCG1 antibody to identify that HOXB13 upregulates ABCG1 expression level. (E) Depletion of ABCG1 enhances the drug sensitivity of lung adenocarcinoma cells. Left: Depletion of ABCG1 by siRNAs in H1299 Flag and H1299 Flag-HOXB13 cells. Middle: Quantification the bands to show the knockdown significant of ABCG1 by specific siRNA (Unpaired Student's t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, *** p<0.001). Right: Depletion of ABCG1 enhanced cisplatin sensitivity in H1299 cells with or without HOXB13 overexpression. Cells were treated with various doses of cisplatin for 48 h. The stars in different colors represent a significant difference in the corresponding curve of this color compared with the according control cells (Unpaired Student's t-test, *p<0.05, ** p <0.01, *** p < 0.001).

When ABCG1 was depleted in HOXB13-overexpressing H1299 cells using ABCG1 siRNAs, the cell viability significantly decreased in the presence of cisplatin (p < 0.05) (Figure 3E and Figure S3C). These results indicated that the HOXB13-ABCG1 axis regulated chemoresistance in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Also, K-M plot survival analysis showed that the increased ABCG1 mRNA predicted poor survival in lung adenocarcinoma patients but not in SCC patients (Figure S4A). These findings indicated that ABCG1 mediates chemoresistance of lung adenocarcinoma cells to cisplatin.

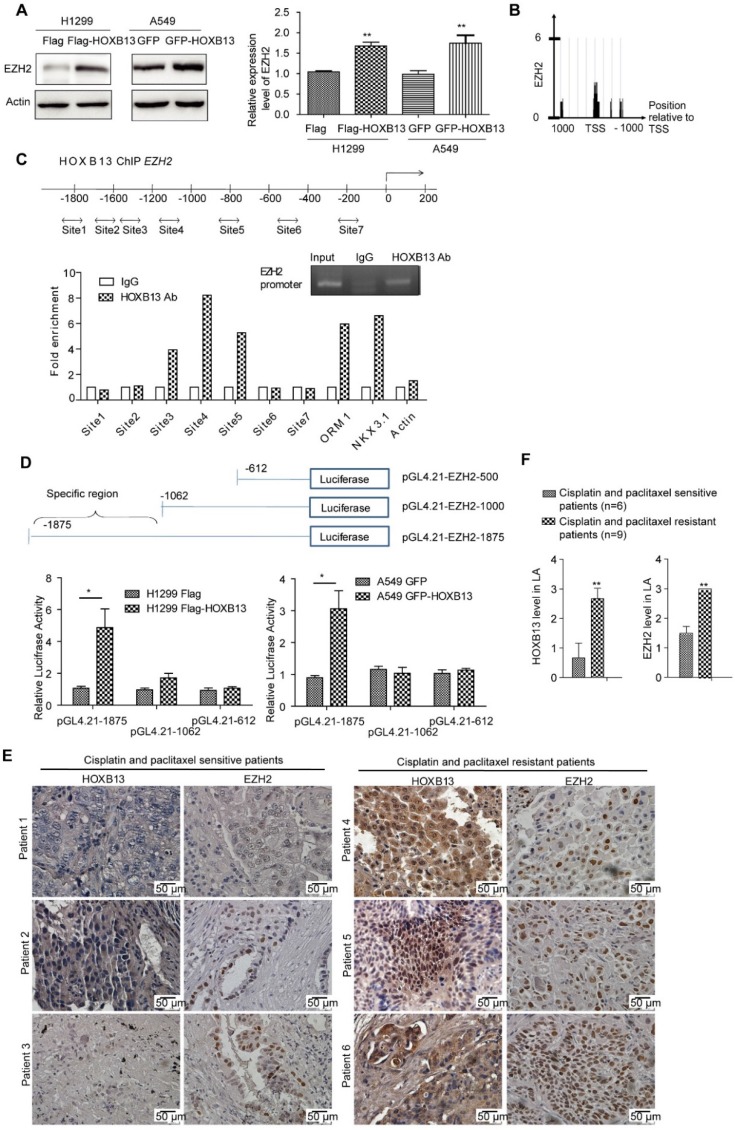

HOXB13 upregulates EZH2 expression via direct binding to the EZH2 promoter

EZH2, a key epigenetic regulator that catalyzes the trimethylation of H3K27, is frequently overexpressed in cancer patients and correlates with poor patient prognosis when expressed at high levels 34. EZH2 is also known to be tightly correlated with lung cancer progression 35 and drug resistance 36. We, therefore, examined whether EZH2 was involved in HOXB13-regulated progression of lung adenocarcinoma. The results showed that the transient expression of Flag-HOXB13 or GFP-HOXB13 increased the expression of EZH2 and EZH2 gene was also transcriptionally upregulated by HOXB13 (Figure 4A). Furthermore, since the enrichment of HOXB13 on the EZH2 promoter in prostate cancer was evident by ChIP-seq analysis 37 (Figure 4B), we selected various regions of the EZH2 promoter for ChIP analysis. The results showed that three regions of the EZH2 promoter contained the putative HOXB13-binding sequences (Figure 4C). The luciferase report assay further showed specific binding of HOXB13 to a region from -1000 to -1875 bp (Figure 4D). EZH2 was also known to promote migration and metastasis in NSCLC cells 23. The migration rescue assay indicated that HOXB13-promoted lung adenocarcinoma cell migration could be inhibited by the depletion of EZH2, suggesting that EZH2 was required for the HOXB13 promotion of cell migration (Figure S5).

Figure 4.

HOXB13 targets to and upregulates EZH2. (A) Upregulation of EZH2 by HOXB13 in lung adenocarcinoma cells. H1299 and A549 cells were transiently transfected by Flag-HOXB13 or GFP-HOBX13 separately, controlled by Flag or GFP. Left panel: Cell lysates were prepared and were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-EZH2 antibody. Right panel: Transcriptional detection of HOXB13-upregulated EZH2 by qPCR. (B) Enrichment of HOXB13 on the EZH2 promoter analyzed by ChIP-seq database from prostate cancer 37. (C) HOXB13 targets EZH2 in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Upper panel: Diagram of the EZH2 promoter with potential HOXB13 binding sites (double arrow). Lower panel: ChIP analysis was performed using either an anti-HOXB13 ChIP-grade antibody or control IgG in H1299 Flag-HOXB13 cells. Sites 3, 4, and 5 in EZH2 promoter are enriched in a qPCR analysis with known target genes of HOXB13 including ORM1, NKX3.1 as positive controls, and actin as a negative control. Insert is the gel picture of ChIP analysis for HOXB13 targeting on EZH2 promoter. (D) EZH2 promoter-luciferase reporter construct map. Lower panel: Luciferase reporter constructs were co-transfected with vector or HOXB13, towards the identification of 1062-1875bp upstream region critical for HOXB13-directed enhancement (Unpaired Student's t-test, **p < 0.01) in H1299 (left panel) and in A549 cells (right panel). (E) Levels of HOXB13 and EZH2 in patients' tumor specimens were detected by immunohistochemical analyses using HOXB13 and EZH2 antibodies separately. Patients 1-3: HOXB13 and EZH2 were low in cisplatin- and paclitaxel-sensitive lung adenocarcinoma patients. Patients 4-6: HOXB13 and EZH2 were high in cisplatin- and paclitaxel-resistant lung adenocarcinoma patients. (F) Quantification for the levels of HOXB13 and EZH2 in cisplatin- and paclitaxel-sensitive (n=6) or resistant (n=9) lung adenocarcinoma patients (Unpaired Student's t-test, ** p<0.01).

To assess the relationship between EZH2 and lung adenocarcinoma progression, we examined EZH2 gene expression levels and lung adenocarcinoma patient outcomes. As per K-M plot survival analysis, the level of EZH2 expression predicted poor outcome in lung adenocarcinoma patients, but not in SCC patients (Figure S4B). Further, in a proof-of-concept experiment, we compared HOXB13 and EZH2 levels between nine patients who were resistant to cisplatin and paclitaxel therapies and those who were sensitive to the two drugs. The drug-resistant group exhibited significantly higher levels of both HOXB13 and EZH2 compared with the drug-sensitive group (Figure 4E and F). Taken together, these findings indicated that EZH2 is a direct target of HOXB13 and mediates HOXB13-induced drug resistance in lung adenocarcinomas. Thus, HOXB13 and its target gene products may be used to evaluate the effectiveness of chemotherapy and predict drug resistance in lung adenocarcinoma patients.

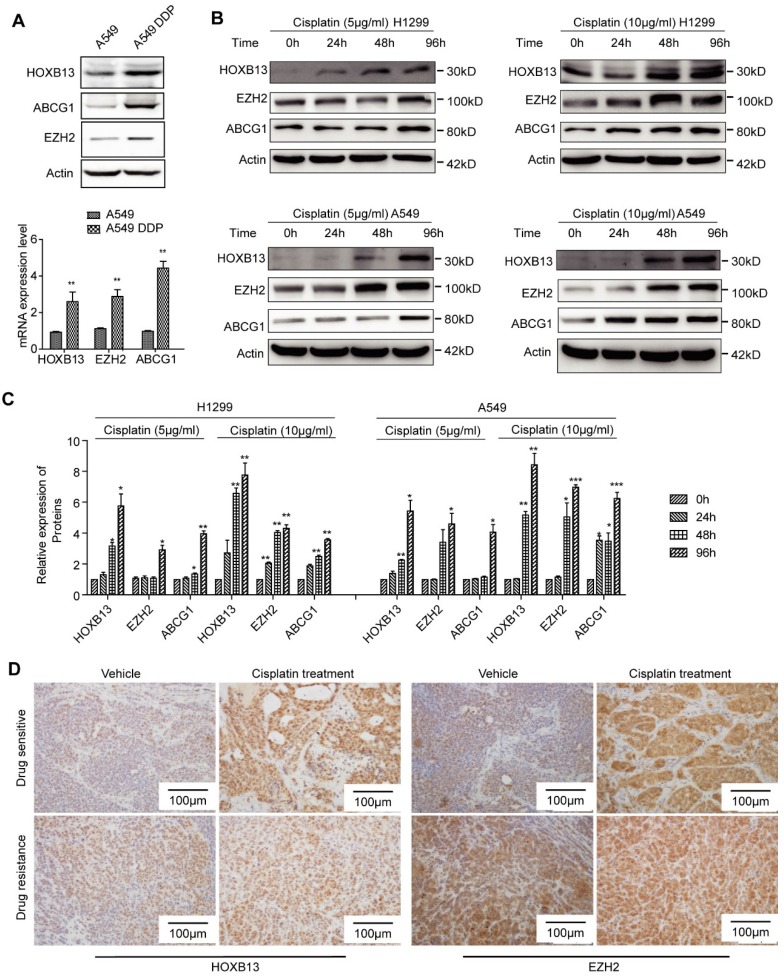

HOXB13 expression is induced by cisplatin therapy

In this study, 17.81% of the lung adenocarcinoma patients, who had not experienced chemotherapy, expressed high levels of HOXB13 (Table 1) which may explain the inherent resistance to chemotherapy observed in some patients. For the patients exhibiting secondary resistance, we determined that cisplatin could induce HOXB13 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. The observations that support the cisplatin-induced expression of HOXB13 include, increased expression of HOXB13 and its target gene products ABCG1 and EZH2 in the established cisplatin-resistant cell lines (A549 and DDP) in a time-dependent manner (Figure 5A, B and C). Also, an ex vivo PDX model experiment showed that drug-resistant PDX samples displayed an intrinsic increase in HOXB13 and EZH2 levels that could not be further induced by cisplatin therapy (Figure 5D). In contrast, HOXB13 and EZH2 levels in drug-sensitive PDX samples could be induced by cisplatin therapy (Figure 5D). These findings strongly supported the notion that drug resistance is induced in PDX by enhanced levels of the HOXB13-EZH2 axis after cisplatin therapy. We have therefore proposed a cisplatin-HOXB13-ABCG1/EZH2 network that mediates chemotherapy-induced secondary drug resistance in lung adenocarcinomas.

Figure 5.

Cisplatin induces expression of HOXB13. (A) HOXB13 and its target genes ABCG1and EZH2 were induced in cisplatin-resistant A549 cells (A549 DDP) at the protein (Upper) and transcriptional levels (Lower) determined by Western blot or qPCR analyses. All these drug resistance genes were significantly upregulated by cisplatin induction (**p<0.01). (B) HOXB13, EZH2, and ABCG1 were transiently induced in the presence of 5 μM or 10 μM cisplatin treatment at indicated time points in A549 and H1299 cells, as detected by Western blot analysis. (C) Quantification of the bands to show that cisplatin upregulates HOXB13 and its target protein expression. (Unpaired Student's t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001) (D) HOXB13 and EZH2 levels were detected in drug-sensitive and drug-resistant PDX samples with or without cisplatin treatment by IHC. Left were detected by HOXB13 antibody and right were detected by EZH2 antibody.

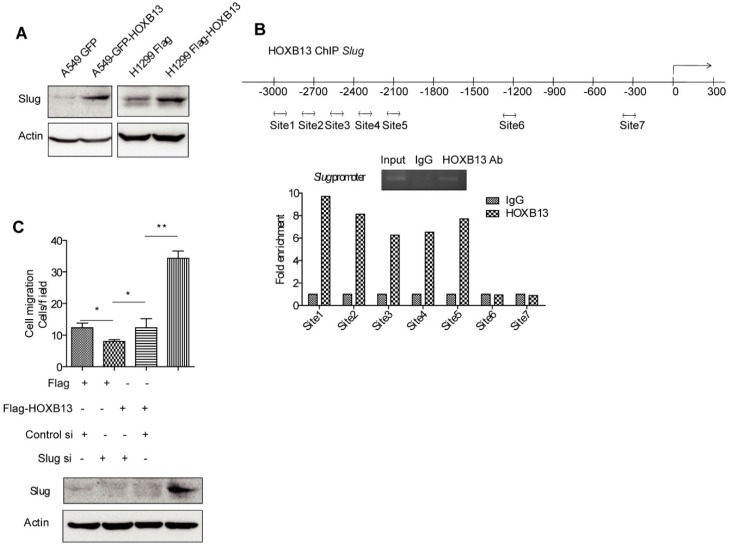

HOXB13 induces lung cancer cell migration by upregulation of Slug via direct binding to the Slug gene promoter

As an important EMT regulator, Slug has been known to regulate lung cancer migration, invasion, and resistance to targeted therapy 38. It was recently reported that HOXB13 induced Slug expression by regulating the Slug promoter activity in ovarian cancer 39. It was of interest to investigate whether HOXB13 also regulated Slug in lung cancer cells. The results from Western blot analysis showed that the Slug protein level was elevated upon transient expression of Flag-HOXB13 or GFP-HOXB13 (Figure 6A), suggesting that HOXB13 was able to upregulate Slug expression in lung adenocarcinoma cells. We performed a ChIP assay to examine whether HOXB13 could directly bind to the Slug promoter. As shown in Figure 6B, HOXB13 bound specifically to a region extending from -2000 to -3000 bp (Figure 6B). It was also of interest to know whether Slug mediated HOXB13-regulated cellular functions. We, therefore, transiently co-expressed Flag-HOXB13 and Slug siRNA in H1299 cells. Figure 6C shows that the Flag-HOXB13-promoted lung adenocarcinoma cell migration could be inhibited by depletion of Slug, suggesting that Slug is required for the HOXB13 effect on cell migration.

Figure 6.

HOXB13 targets to the promoter of Slug and upregulates Slug gene expression. (A) H1299 and A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells were transiently transfected by Flag-HOXB13 or GFP-HOXB13 separately, controlled by Flag or GFP. Cell lysates were prepared and were subjected to Western blot analyses using the anti-Slug antibody. (B) HOXB13 occupies Slug promoter. Potential regions of the Slug promoter with HOXB13 binding sites (double arrow). ChIP analysis was performed using either an anti-HOXB13 ChIP-grade antibody or control IgG in H1299 Flag-HOXB13 cells. Gel picture of ChIP analysis for HOXB13 occupancy on Slug promoter was given. Sites 1 to 5 are enriched on Slug promoter under HOXB13 expression determined by qPCR analysis. (C) Slug is required for HOXB13-promoted lung adenocarcinoma cell migration. Upper panel: H1299 cells were transfected by Flag-HOXB13 controlled by Flag vector, simultaneously cells were transfected with Slug siRNA controlled by scramble RNA. Cell migration was determined and results were analyzed from three independent experiments (Unpaired Student's t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). Lower panel: Western blot analysis was subjected to determine the upregulation of Slug by HOXB13 overexpression and Slug knockdown by siRNA using an anti-Slug antibody.

HOXB13 directly targets its own gene promoter and forms a positive feedback regulatory loop

Interestingly, we observed that when exogenous HOXB13 was transfected into lung cancer cells, the endogenous HOXB13 was induced to high levels in both H1299 and A549 cells (Figure S6A). These findings suggested the self-upregulation ability of HOXB13. To identify the HOXB13 binding sites within its own promoter, primers for ChIP analysis were designed. Specific enrichment for binding to the HOXB13 promoter was detected in site 1 (Figure S6B). Furthermore, a genome-wide ChIP-seq analysis also confirmed the existence of several HOXB13 binding sites on the HOXB13 gene promoter, which were located at -500∼0 bp from the TSS (Figure S6C). A luciferase reporter assay further determined that HOXB13 specifically bound to a region - 200 to - 600 bp from the TSS of HOXB13 gene promoter (Figure S6D). These findings indicated that HOXB13 is regulated through a positive feedback loop by binding to its own promoter.

We also observed that the HOXB13 overexpression in xenografted tumors correlated with the increased expression of the HOXB13 target proteins (Figure S6E). These data suggested that HOXB13 could self-upregulate in vivo as well as other targeted genes important for tumor progression and/or drug resistance. Taken together, HOXB13 may form a positive feedback regulatory loop by binding to its own gene promoter important for continuous cancer progression.

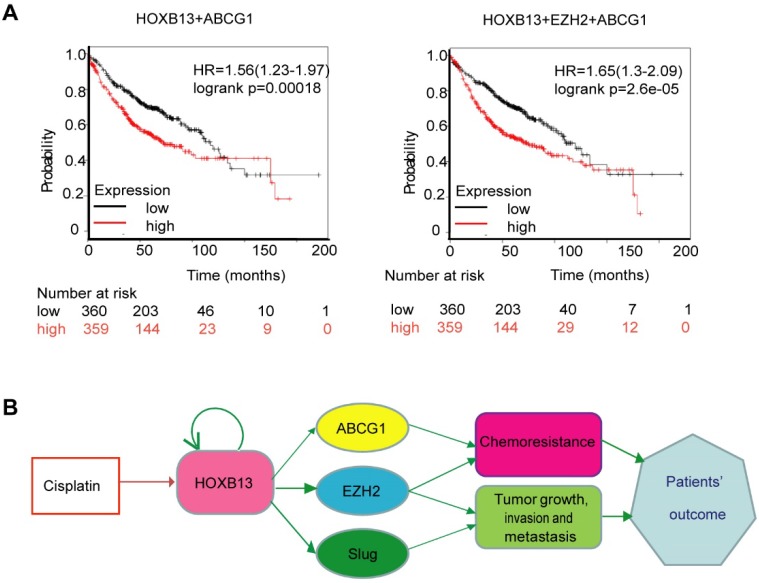

HOXB13 in combination with ABCG1 and EZH2 improves prediction of lung adenocarcinoma patients' outcome

We hypothesized that a combination of HOXB13 target genes might predict patients' response to chemotherapy. To test this hypothesis, different combinations of HOXB13 with its target genes were used to predict lung adenocarcinoma survival in 719 patients. As is evident from Figure 7A, the combined expression of HOXB13, EZH2, and ABCG1 was the best prognosticator in lung adenocarcinoma patients (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Combination use of HOXB13 with ABCG1 and EZH2 gives high precision in predicting lung adenocarcinoma patients' outcome. (A) Combination of HOXB13 with its target gene expressions to predict lung adenocarcinoma prognosis. (B) Working model: HOXB13 induced by cisplatin confers lung adenocarcinoma patients' drug resistance by direct targeting to the newly identified drug resistance gene ABCG1 and also known drug resistance gene EZH2. Further, HOXB13 mediates metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma patients by direct targeting to EZH2 and Slug. Combination of HOXB13, ABCG1, EZH2 presents a better strategy to predict outcome or resistance to chemotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma patients.

Taken together, our findings revealed a novel mechanism underlying HOXB13-mediated drug resistance after chemotherapy in lung adenocarcinomas. Furthermore, HOXB13 increased lung adenocarcinoma invasion and metastasis after chemotherapy by regulating a panel of downstream targets (Figure 7B). Thus, targeting HOXB13 may represent a new strategy to overcome lung adenocarcinoma chemoresistance to platinum-based therapy.

Discussion

Platinum-based chemotherapy was shown to be effective for treating advanced NSCLC. However, in many patients, this initial response to cisplatin soon disappears and chemoresistance emerges, resulting in patient death and the poor 5-year survival rates 40. Resistance to cisplatin has become a major clinical challenge in the treatment of NSCLC. Cisplatin resistance is a complex phenomenon and uncovering the molecular mechanisms involved in inherent and acquired resistance is important to overcome drug resistance.

In this study, we found a panel of HOXB13 target genes that underlie the molecular mechanism of HOXB13-mediated metastasis and drug resistance in lung adenocarcinoma. Among them, ABCG1, a gene involved in cholesterol homeostasis, was found to confer chemoresistance upon lung adenocarcinoma cells. We demonstrated that the depletion of ABCG1 markedly decreased HOXB13-induced resistance to cisplatin, indicating that ABCG1 is required for HOXB13-induced drug resistance in lung adenocarcinoma. Therefore, targeting ABCG1 may increase the efficacy of cisplatin treatment in lung adenocarcinomas.

Mechanistically, we found that HOXB13 directly targets the EZH2 promoter, upregulating EZH2 expression in lung adenocarcinoma, and consequently drives chemoresistance and promotes metastasis. In lung, breast, and prostate cancers, EZH2 is a marker of poor prognosis with expression increasing at the most advanced stages 41-43. Targeting EZH2 has been widely known to be an antitumor strategy 44-47. Upon treatment with cisplatin, the levels of HOXB13 and EZH2 were upregulated in drug-sensitive PDX samples, supporting our notion that the expression of HOXB13 and EZH2 is induced by cisplatin. This is the first indication that therapeutic drugs can induce HOXB13. However, in the drug-resistant PDX samples, the levels of HOXB13 and EZH2 could not be further enhanced (Figure 5C). This finding may indicate that the levels of HOXB13 and EZH2 in the tumor tissues were already high and, therefore, cisplatin treatment would be ineffective.

Slug, a well-known EMT-regulating transcription factor, is overexpressed in numerous cancers 48. Elevated expression of Slug is associated with (i) reduced E-cadherin expression, (ii) high histologic grade, (iii) lymph node metastasis, (iv) postoperative relapse, and (v) shorter patient survival in a variety of cancers 38, 48-50. Slug expression is negatively regulated by thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) 51, 52 and positively regulated by Oct4/Nanog (51). Slug binds to the promoter of 15-HPG, an enzyme responsible for the degradation of prostaglandin E2, and suppresses 15-HPG expression 53. Prostaglandin E2 has been associated with increased tumor angiogenesis, metastasis, and cell cycle regulation. Slug suppresses the expression of 15-HPG resulting in an increased prostaglandin E2 level in NSCLC cells, thus promoting NSCLC progression 54. Our results indicate that HOXB13 mediates the invasion and metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma by directly targeting the Slug promoter and upregulating Slug expression.

ABCG1, EZH2, and Slug have important roles in regulating the fate of cancer stem cells. It is, therefore, likely that HOXB13-upregulated EZH2 expression may confer lung cancer cells with cancer stem cell properties resulting in drug resistance of lung cancer cells and increased metastatic potential. This hypothesis warrants future investigation.

In this report, for the first time, we have demonstrated that cisplatin induces HOXB13 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. Thus, we have elucidated a model depicting the induction of platinum-based drug resistance in lung adenocarcinoma patients (Figure 7B). Given that HOXB13 directly targets ABCG1 promoter and that the depletion of ABCG1 enhances lung adenocarcinoma sensitivity to cisplatin treatment, ABCG1 may function as a chemoresistance gene in lung adenocarcinoma. Since EZH2 is known to drive acquired resistance to chemotherapy 36, we propose that a cisplatin-HOXB13-ABCG1/EZH2 network controls acquired chemoresistance in lung adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, HOXB13 may be of value as a potential drug target for increasing the efficacy of cisplatin treatment in lung adenocarcinoma as depicted in the model (Figure 7B). It has also been shown that targeting EZH2 is a common antitumor strategy 44-47; combining the use of an EZH2 inhibitor with cisplatin or the depletion of ABCG1 combined with cisplatin may be important in improving cisplatin therapeutic efficacy and reducing the side effects for lung adenocarcinoma patients.

Drug resistance could occur naturally (inherent resistance) or be acquired during chemotherapy or upon cancer recurrence after successful chemotherapy (secondary resistance) 55. Platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the standard first-line treatment for metastatic NSCLC with response rates ranging only between 15-30%. In this study, 17.81% of the lung adenocarcinoma patients who had not experienced chemotherapy expressed elevated levels of HOXB13 (Table 1), which may explain the inherent resistance observed in the patients. However, the reason for HOXB13 overexpression in these patients is still unknown. Our study also uncovered the mechanism of acquired resistance. Cisplatin induces the expression of HOXB13 and leads to drug resistance. Cisplatin is known to crosslink with DNA and induce mitotic crisis and cell death 56. However, the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying cisplatin upregulation of HOXB13 level remain unknown and include various possibilities. First, DNA repair-related proteins including nucleotide excision repair (NER), homologous recombination (HR) and Fanconi anemia (FA) pathways may upregulate HOXB13 gene expression. Second, it is possible that there are cisplatin-binding elements within the promoter of the HOXB13 gene, which activate HOXB13 gene expression. And third, tumors acquire resistance to systemic treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy due to the dynamic intratumoral heterogeneity (ITH) and clonal repopulation 57, 58. It is possible that the inherently resistant cells are enriched in the tumor tissue by cisplatin therapy.

Recently, immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitor agents was effective in advanced NSCLC. Two immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1), nivolumab and pembrolizumab, were approved for second-line therapy of NSCLC. Recently, another checkpoint inhibitor that targets program death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), atezolizumab, was approved for NSCLC therapy 59. Another drug, pembrolizumab also received approval for first-line NSCLC treatment in patients with high PD-L1-expressing tumors. Immunotherapy for NSCLC has recently evolved into an important treatment modality with the acceptance of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as the new standard of care for second-line treatment 59. The sequential combination of definitive chemoradiotherapy followed by durvalumab maintenance in stage III NSCLC became the new therapeutic standard 60, while the addition of pembrolizumab to first-line chemotherapy in metastatic NSCLC significantly improved overall survival 61. We believe that understanding whether the NSCLC patients are sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy by measuring the gene expression levels of HOXB13-ABCG1/EZH2/Slug axis will help clinicians in deciding whether administration of platinum-based drugs prior to immunotherapy would be a more effective treatment modality for the lung adenocarcinoma patients.

In summary, we have identified a new network that mediates lung adenocarcinoma metastasis and cisplatin resistance. Analyzing the cisplatin- HOXB13-ABCG1/EZH2/Slug network will facilitate the evaluation of the potential therapeutic efficacy of cisplatin-based therapy and predict patient sensitivity to treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods, figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFC1302103, 2015CB553906), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773199, 81730071, 81230051, 81472734, and 31170711); the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (grants 7120002 and 7171005), the 111 Project of the Ministry of Education, grants from Peking University (BMU20120314 and BMU20130364); and a Leading Academic Discipline Project of Beijing Education Bureau to H.Z.

Abbreviations

- EZH2

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2

- HOXB13

homeobox-containing transcriptional factor B13

- ABCG1

ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 1

- PRC2

Component of the polycomb repressive complex 2

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- 15-HPG

15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- HR

homologous recombination

- FA

fanconi anemia

- ITH

intratumoral heterogeneity

- PD-1

programmed cell death-1.

References

- 1.JP Pignon, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV. et al. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3552–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.L Zeltser, Desplan C, Heintz N. Hoxb-13: a new Hox gene in a distant region of the HOXB cluster maintains colinearity. Development. 1996;122:2475–84. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.YR Kim, Kim IJ, Kang TW. et al. HOXB13 downregulates intracellular zinc and increases NF-kappaB signaling to promote prostate cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2014;33:4558–67. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.JD Norris, Chang CY, Wittmann BM. et al. The homeodomain protein HOXB13 regulates the cellular response to androgens. Mol Cell. 2009;36:405–16. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MM Pomerantz, Li F, Takeda DY. et al. The androgen receptor cistrome is extensively reprogrammed in human prostate tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1346–51. doi: 10.1038/ng.3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.T Whitington, Gao P, Song W. et al. Gene regulatory mechanisms underpinning prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2016;48:387–97. doi: 10.1038/ng.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.C Sipeky, Gao P, Zhang Q, Synergistic interaction of HOXB13 and CIP2A predispose to aggressive prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res; 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.K Ghoshal, Motiwala T, Claus R. et al. HOXB13, a target of DNMT3B, is methylated at an upstream CpG island, and functions as a tumor suppressor in primary colorectal tumors. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.N Shah, Jin K, Cruz LA. et al. HOXB13 mediates tamoxifen resistance and invasiveness in human breast cancer by suppressing ERalpha and inducing IL-6 expression. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5449–58. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.JY Zhu, Sun QK, Wang W. et al. High-level expression of HOXB13 is closely associated with tumor angiogenesis and poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:2925–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.L Marra, Cantile M, Scognamiglio G. et al. Deregulation of HOX B13 expression in urinary bladder cancer progression. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:833–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PT Tarr, Tarling EJ, Bojanic DD. et al. Emerging new paradigms for ABCG transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:584–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.E Ikonen. Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:125–38. doi: 10.1038/nrm2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MA Kennedy, Barrera GC, Nakamura K. et al. ABCG1 has a critical role in mediating cholesterol efflux to HDL and preventing cellular lipid accumulation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.N Wang, Lan D, Chen W. et al. ATP-binding cassette transporters G1 and G4 mediate cellular cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9774–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403506101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.JM Sturek, Castle JD, Trace AP. et al. An intracellular role for ABCG1-mediated cholesterol transport in the regulated secretory pathway of mouse pancreatic beta cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2575–89. doi: 10.1172/JCI41280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.EJ Tarling, Edwards PA. ATP binding cassette transporter G1 (ABCG1) is an intracellular sterol transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19719–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113021108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.C Tian, Huang D, Yu Y. et al. ABCG1 as a potential oncogene in lung cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2017;13:3189–94. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Y Wang, Liu H, Ready NE. et al. Genetic variants in ABCG1 are associated with survival of nonsmall-cell lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:2592–601. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WA Cooper, Lam DC, O'Toole SA. et al. Molecular biology of lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(Suppl 5):S479–90. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.08.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.M Jakopovic, Thomas A, Balasubramaniam S. et al. Targeting the epigenome in lung cancer: expanding approaches to epigenetic therapy. Front Oncol. 2013;3:261. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.H Xia, Zhang W, Li Y. et al. EZH2 silencing with RNA interference induces G2/M arrest in human lung cancer cells in vitro. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:348728. doi: 10.1155/2014/348728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.J Geng, Li X, Zhou Z. et al. EZH2 promotes tumor progression via regulating VEGF-A/AKT signaling in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015;359:275–87. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Y Lv, Yuan C, Xiao X. et al. The expression and significance of the enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:147–54. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.J Chen, Xu Y, Tao L. et al. MiRNA-26a Contributes to the Acquisition of Malignant Behaviors of Doctaxel-Resistant Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells through Targeting EZH2. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41:583–97. doi: 10.1159/000457879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.C Xu, Hao K, Hu H. et al. Expression of the enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in biopsy specimen predicts chemoresistance and survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer receiving first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2014;86:268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.P Workman, Aboagye EO, Balkwill F. et al. Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1555–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.J Zhan, Song J, Wang P. et al. Kindlin-2 induced by TGF-beta signaling promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression through downregulation of transcriptional factor HOXB9. Cancer Lett. 2015;361:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.JR Masters, Thomson JA, Daly-Burns B. et al. Short tandem repeat profiling provides an international reference standard for human cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8012–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121616198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Y Zhang, Xu W, Guo H. et al. NOTCH1 Signaling Regulates Self-Renewal and Platinum Chemoresistance of Cancer Stem-like Cells in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3082–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.A Ouhtit, Al-Kindi MN, Kumar PR. et al. Hoxb13, a potential prognostic biomarker for prostate cancer. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2016;8:40–5. doi: 10.2741/E749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DG Beer, Kardia SL, Huang CC. et al. Gene-expression profiles predict survival of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2002;8:816–24. doi: 10.1038/nm733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.J Zhan, Niu M, Wang P. et al. Elevated HOXB9 expression promotes differentiation and predicts a favourable outcome in colon adenocarcinoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:883–93. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.T Jiang, Wang Y, Zhou F. et al. Prognostic value of high EZH2 expression in patients with different types of cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:4584–97. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.H Xia, Yu C, Zhang W. et al. [Development of New Molecular EZH2 on Lung Cancer Invasion and Metastasis] Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2016;19:98–101. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2016.02.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.EE Gardner, Lok BH, Schneeberger VE. et al. Chemosensitive Relapse in Small Cell Lung Cancer Proceeds through an EZH2-SLFN11 Axis. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:286–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Q Huang, Whitington T, Gao P. et al. A prostate cancer susceptibility allele at 6q22 increases RFX6 expression by modulating HOXB13 chromatin binding. Nat Genet. 2014;46:126–35. doi: 10.1038/ng.2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.JY Shih, Yang PC. The EMT regulator slug and lung carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1299–304. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.H Yuan, Kajiyama H, Ito S. et al. HOXB13 and ALX4 induce SLUG expression for the promotion of EMT and cell invasion in ovarian cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:13359–70. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MS Altieri, Telem DA, Kim P. et al. Case review and consideration for imaging and work evaluation of the pregnant bariatric patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:667–71. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.SH Jang, Lee JE, Oh MH. et al. High EZH2 Protein Expression Is Associated with Poor Overall Survival in Patients with Luminal A Breast Cancer. J Breast Cancer. 2016;19:53–60. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2016.19.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.S Varambally, Dhanasekaran SM, Zhou M. et al. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature. 2002;419:624–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.C Behrens, Solis LM, Lin H. et al. EZH2 protein expression associates with the early pathogenesis, tumor progression, and prognosis of non-small cell lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6556–65. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.L Li, Wu J, Zheng F. et al. Inhibition of EZH2 via activation of SAPK/JNK and reduction of p65 and DNMT1 as a novel mechanism in inhibition of human lung cancer cells by polyphyllin I. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:112. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0388-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.H Zhang, Qi J, Reyes JM, Oncogenic deregulation of EZH2 as an opportunity for targeted therapy in lung cancer. Cancer Discov; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.A Italiano. Role of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol Ther; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.M Serresi, Gargiulo G, Proost N. et al. Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Is a Barrier to KRAS-Driven Inflammation and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.JY Shih, Tsai MF, Chang TH. et al. Transcription repressor slug promotes carcinoma invasion and predicts outcome of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8070–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.CC Alves, Carneiro F, Hoefler H. et al. Role of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulator Slug in primary human cancers. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009;14:3035–50. doi: 10.2741/3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.M Shioiri, Shida T, Koda K. et al. Slug expression is an independent prognostic parameter for poor survival in colorectal carcinoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1816–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.YL Chang, Lee YC, Liao WY. et al. The utility and limitation of thyroid transcription factor-1 protein in primary and metastatic pulmonary neoplasms. Lung Cancer. 2004;44:149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.RA Saito, Watabe T, Horiguchi K. et al. Thyroid transcription factor-1 inhibits transforming growth factor-beta-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2783–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.YC Chen, Hsu HS, Chen YW. et al. Oct-4 expression maintained cancer stem-like properties in lung cancer-derived CD133-positive cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.L Yang, Amann JM, Kikuchi T. et al. Inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling elevates 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5587–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.J Gong, Jaiswal R, Mathys JM. et al. Microparticles and their emerging role in cancer multidrug resistance. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:226–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.F Coste, Malinge JM, Serre L. et al. Crystal structure of a double-stranded DNA containing a cisplatin interstrand cross-link at 1.63 A resolution: hydration at the platinated site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1837–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.8.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.I Tirosh, Venteicher AS, Hebert C. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq supports a developmental hierarchy in human oligodendroglioma. Nature. 2016;539:309–13. doi: 10.1038/nature20123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.J Zhang, Fujimoto J, Zhang J. et al. Intratumor heterogeneity in localized lung adenocarcinomas delineated by multiregion sequencing. Science. 2014;346:256–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1256930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.J Malhotra, Jabbour SK, Aisner J. Current state of immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2017;6:196–211. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2017.03.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.SJ Antonia, Villegas A, Daniel D. et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1919–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.G Fuca, de Braud F, Di Nicola M. Immunotherapy-based combinations: an update. Curr Opin Oncol. 2018;30:345–51. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary methods, figures and tables.