Abstract

Background

While most guidance recommends the use of insulin in women whose pregnancies are affected by pre‐existing diabetes, oral anti‐diabetic agents may be more acceptable to women. The effects of these oral anti‐diabetic agents on maternal and infant health outcomes need to be established in pregnant women with pre‐existing diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance, as well as in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus preconceptionally or during a subsequent pregnancy. This review is an update of a review that was first published in 2010.

Objectives

To investigate the effects of oral anti‐diabetic agents in women with established diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes who are planning a pregnancy, or pregnant women with pre‐existing diabetes, on maternal and infant health. The use of oral anti‐diabetic agents for the management of gestational diabetes in a current pregnancy is evaluated in a separate Cochrane Review.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 October 2016) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs assessing the effects of oral anti‐diabetic agents in women with established diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes who were planning a pregnancy, or pregnant women with pre‐existing diabetes. Cluster‐RCTs were eligible for inclusion, but none were identified.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed study eligibility, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias of the included RCTs. Review authors checked the data for accuracy, and assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We identified six RCTs (707 women), eligible for inclusion in this updated review, however, three RCTs had mixed populations (that is, they included pregnant women with gestational diabetes) and did not report data separately for the relevant subset of women for this review. Therefore we have only included outcome data from three RCTs; data were available for 241 women and their infants. The three RCTs all compared an oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) with insulin. The women in the RCTs that contributed data had type 2 diabetes diagnosed before or during their pregnancy. Overall, the RCTs were judged to be at varying risk of bias. We assessed the quality of the evidence for selected important outcomes using GRADE; the evidence was low‐ or very low‐quality, due to downgrading because of design limitations (risk of bias) and imprecise effect estimates (for many outcomes only one or two RCTs contributed data).

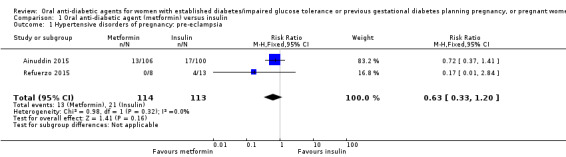

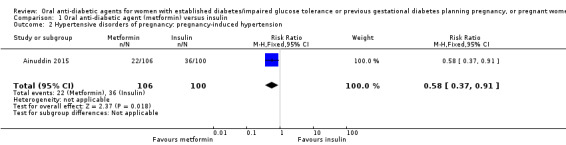

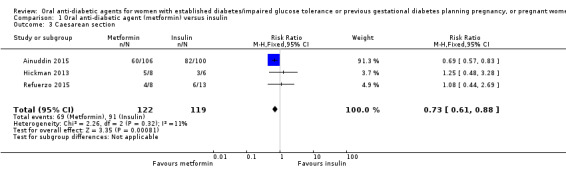

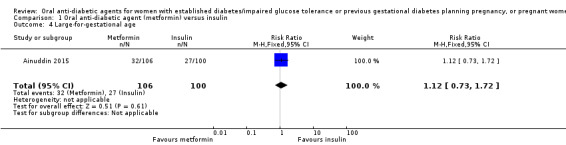

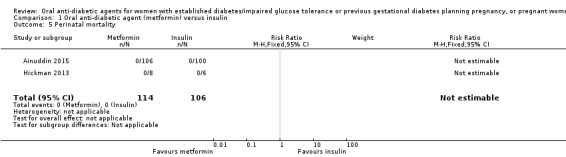

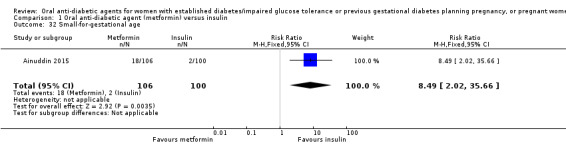

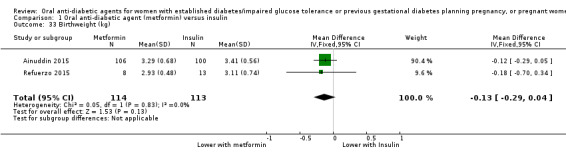

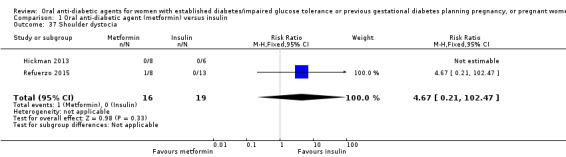

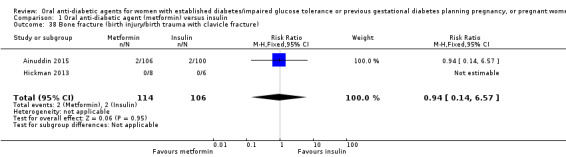

For our primary outcomes there was no clear difference between metformin and insulin groups for pre‐eclampsia (risk ratio (RR) 0.63, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.33 to 1.20; RCTs = 2; participants = 227; very low‐quality evidence) although in one RCT women receiving metformin were less likely to have pregnancy‐induced hypertension (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.91; RCTs = 1; participants = 206; low‐quality evidence). Women receiving metformin were less likely to have a caesarean section compared with those receiving insulin (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.88; RCTs = 3; participants = 241; low‐quality evidence). In one RCT there was no clear difference between groups for large‐for‐gestational‐age infants (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.72; RCTs = 1; participants = 206; very low‐quality evidence). There were no perinatal deaths in two RCTs (very low‐quality evidence). Neonatal mortality or morbidity composite outcome and childhood/adulthood neurosensory disability were not reported.

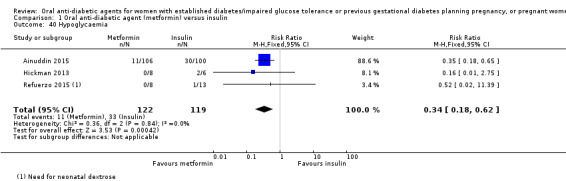

For other secondary outcomes we assessed using GRADE, there were no clear differences between metformin and insulin groups for induction of labour (RR 1.42, 95% CI 0.62 to 3.28; RCTs = 2; participants = 35; very low‐quality evidence), though infant hypoglycaemia was reduced in the metformin group (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.62; RCTs = 3; infants = 241; very low‐quality evidence). Perineal trauma, maternal postnatal depression and postnatal weight retention, and childhood/adulthood adiposity and diabetes were not reported.

Authors' conclusions

There are insufficient RCT data to evaluate the use of oral anti‐diabetic agents in women with established diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes who are planning a pregnancy, or in pregnant women with pre‐existing diabetes. Low to very low‐quality evidence suggests possible reductions in pregnancy‐induced hypertension, caesarean section birth and neonatal hypoglycaemia with metformin compared with insulin for women with type 2 diabetes diagnosed before or during their pregnancy, and no clear differences in pre‐eclampsia, induction of labour and babies that are large‐for‐gestational age. Further high‐quality RCTs that compare any combination of oral anti‐diabetic agent, insulin and dietary and lifestyle advice for these women are needed. Future RCTs could be powered to evaluate effects on short‐ and long‐term clinical outcomes; such RCTs could attempt to collect and report on the standard outcomes suggested in this review. We have identified three ongoing studies and four are awaiting classification. We will consider these when this review is updated.

Plain language summary

Oral anti‐diabetic agents for women with diabetes or previous diabetes planning a pregnancy, or pregnant women with pre‐existing diabetes

What is the issue?

Pre‐existing diabetes and gestational diabetes can increase the risks of a number of poor outcomes for both mothers and their babies. For the mother, these include pregnancy‐induced high blood pressure (pre‐eclampsia) with additional fluid retention and protein in the urine; and giving birth by caesarean. For the infant, these can include preterm birth; as well as an increased risk of the presence of physical defects at birth such as heart defects, brain, spine, and spinal cord defects, Down syndrome; and spontaneous abortion. Other complications at birth include babies that are large for their gestational age, and obstructed labour (shoulder dystocia) caused by one of the shoulders becoming stuck in the birth canal once the baby's head has been born.

Why is this important?

Being pregnant can trigger diabetes (gestational diabetes) in women with impaired glucose tolerance. Women who have had gestational diabetes are at risk of developing diabetes later in life. This means that management is important for women with impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes, as well as for women with established diabetes. Women with established diabetes need good blood sugar control before they become pregnant. Insulin gives good blood sugar control and does not affect the development of the baby, but women may find oral anti‐diabetic agents more convenient and acceptable than insulin injections. However little is known about the effects of these oral agents.

This review sought to investigate the effects of oral anti‐diabetic agents in women with established diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes who were planning a pregnancy, or pregnant women with pre‐existing diabetes, on maternal and infant health. This review is an update of a review that was first published in 2010.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on 31 October 2016 and included six RCTs (707 women). Three RCTs included women with current gestational diabetes and did not report data separately for the population of women relevant to this review. Therefore we have only included outcome data from three RCTs, involving 241 pregnant women and their infants. The quality of the evidence was assessed as being low or very low and the overall risk of bias of the RCTs was varied. The three RCTs all compared an oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) with insulin in pregnant women with pre‐existing (type 2) diabetes.

There was no clear difference in the development of pre‐eclampsia (high blood pressure and protein in the urine) for women who received metformin compared with insulin (2 RCTs; 227 women; very low‐quality evidence), though women receiving metformin were less likely to have pregnancy‐induced high blood pressure in one RCT (206 women; low‐quality evidence). Women who received metformin were less likely to have a caesarean section birth (3 RCTs; 241 women; low‐quality evidence), though no difference was observed in induction of labour (2 RCTs; 35 women; very low‐quality evidence). There was no clear difference between groups of infants born to mothers who received metformin or insulin for being large‐for‐gestational age (1 RCT; 206 infants; very low‐quality evidence), though infants born to mothers who received metformin were less likely to have low blood sugar (hypoglycaemia) (3 RCTs; 241 infants; very low‐quality evidence). There were no infant deaths (before birth or shortly afterwards) (2 RCTs; very low‐quality evidence). The RCTs did not report on many important short‐ and long‐term outcomes, including perineal trauma and a combined outcome of infant death or morbidity, postnatal depression and weight retention for mothers, and adiposity or disability in childhood or adulthood for infants.

What does this mean?

There is not enough evidence to guide us on the effects of oral anti‐diabetic agents in women with established diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes who are planning a pregnancy, or pregnant women with pre‐existing diabetes. Further large, well‐designed, RCTs are required and could assess and report on the outcomes suggested in this review, including both short‐ and long‐term outcomes for mothers and their infants.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Maternal outcomes: oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) compared with insulin for women with established type 2 diabetes mellitus.

| Maternal outcomes: oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) compared with insulin for women with established type 2 diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with type 2 diabetes Setting: USA (2 RCTs), Pakistan (1 RCT) Intervention: oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) Comparison: insulin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with insulin | Risk with oral anti‐diabetic (metformin) | |||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: pre‐eclampsia | Study population | RR 0.63 (0.33 to 1.20) | 227 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1,2 | ||

| 186 per 1000 | 117 per 1000 (61 to 223) | |||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: pregnancy‐induced hypertension | Study population | RR 0.58 (0.37 to 0.91) | 206 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 | ||

| 360 per 1000 | 209 per 1000 (133 to 328) | |||||

| Caesarean section | Study population | RR 0.73 (0.61 to 0.88) | 241 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 765 per 1000 | 558 per 1000 (466 to 673) | |||||

| Induction of labour | Study population | RR 1.42 (0.62 to 3.28) | 35 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2,4 | ||

| 316 per 1000 | 448 per 1000 (196 to 1000) | |||||

| Perineal trauma | Study population | ‐ | (0 RCTs) | ‐ | None of the included RCTs reported this outcome | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Postnatal depression | Study population | ‐ | (0 RCTs) | ‐ | None of the included RCTs reported these outcomes | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Postnatal weight retention | Study population | ‐ | (0 RCTs) | ‐ | None of the included RCTs reported these outcomes | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Study limitations (‐2): most of the weight in this analysis was from 1 RCT with very serious design limitations

2 Imprecision (‐2): wide 95% CI crossing the line of no effect and small sample sizes of RCTs

3 Study limitations (‐2): 1 RCT with very serious design limitations contributed data

4 Study limitations (‐1): 2 RCTs with design limitations contributed data

Summary of findings 2. Infant outcomes: oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) compared with insulin for women with established type 2 diabetes mellitus.

| Infant outcomes: oral anti‐diabetic (metformin) compared with insulin for women with established diabetes | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with type 2 diabetes mellitus Setting: USA (2 RCTs) and Pakistan (1 RCT) Intervention: oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) Comparison: insulin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with insulin | Risk with oral anti‐diabetic (metformin) | |||||

| Large‐for‐gestational age | Study population | RR 1.12 (0.73 to 1.72) | 206 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1,2 | ||

| 270 per 1000 | 302 per 1000 (197 to 464) | |||||

| Perinatal mortality | Study population | ‐ | 220 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3,4 | No perinatal mortality in the 2 RCTs | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Hypoglycaemia | Study population | RR 0.34 (0.18 to 0.62) | 241 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 5,6 | ||

| 277 per 1000 | 94 per 1000 (50 to 172) | |||||

| Neonatal mortality or morbidity composite | Study population | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | None of the included RCTs reported this outcome | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Childhood/adulthood neurosensory disability | Study population | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | None of the included RCTs reported this outcome | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Childhood/adulthood adiposity | Study population | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | None of the included RCTs reported this outcome | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Childhood/adulthood diabetes | Study population | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | None of the included RCTs reported this outcome | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Study limitations (‐2): 1 RCT with very serious design limitations contributed data

2 Imprecision (‐2): wide 95% CI crossing the line of no effect and small sample size of RCT

3 Study limitations (‐1): 2 RCTs with design limitations contributed data

4 Imprecision (‐2): no events

5 Study limitations (‐2): most of the weight in this analysis was from 1 RCT with very serious design limitations

6 Imprecision (‐1): small sample sizes of RCTs

Background

Description of the condition

Established diabetes prior to pregnancy and pre‐existing diabetes in pregnancy

Pre‐existing (pregestational) diabetes affects pregnant women who have been diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes ‐ or, in rare cases, other forms of diabetes mellitus ‐ prior to becoming pregnant. While some parts of the world have a significantly higher prevalence of established diabetes than others, in 2015 it was estimated that globally one in 11 (9%) adults aged 20 to 79 years ‐ that is 415 million ‐ had diabetes; this is projected to reach one in 10 (10%) ‐ or 642 million ‐ by 2040 (IDF 2015). An additional 193 million adults are estimated to have undiagnosed diabetes, and a further 318 million, are estimated to have impaired glucose tolerance, which puts them at high risk of developing the disease (IDF 2015). In 2015, it was estimated that 20.9 million, or 16.2% of live births globally were affected by some form of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy ‐ 14.9% (or approximately 3.1 million) of these pregnancies were affected by type 1 or 2 diabetes first detected in pregnancy, or detected prior to pregnancy (established diabetes) (IDF 2015). Prevalence estimates of pre‐existing diabetes in pregnancy have previously been reported as approximately 1% (Bell 2008; Correa 2015; Lawrence 2008), but prevalence is known to be increasing rapidly, with concurrent rises in obesity and type 2 diabetes.

In addition to the impact of diabetes on health, pre‐existing diabetes in pregnancy is commonly associated with a number of adverse health outcomes for mothers and their infants. For pregnant women, pre‐existing diabetes has been associated with caesarean section, pregnancy‐induced hypertension or pre‐eclampsia, and preterm birth (Langer 2000a; Ray 2001; Walkinshaw 2005). Pregnancy in women with pre‐existing diabetes may also exacerbate the effects of diabetes on renal function and retinopathy (Leguizamon 2007; Sheth 2002). Pre‐existing diabetes in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of fetal congenital anomaly and spontaneous abortion (Kitzmiller 1996). Fetal hyperinsulinaemia associated with pre‐existing diabetes may affect infants by increasing the incidence of: macrosomia (birthweight exceeding 4000 g); large‐for‐gestational age (birthweight greater than 90th centile for age); shoulder dystocia; neonatal hypoglycaemia; preterm birth; hyperbilirubinaemia; hypocalcaemia, and neonatal intensive care admission (Jensen 2004; Macintosh 2006; Ray 2001; Walkinshaw 2005; Weintrob 1996). Furthermore, long‐term follow‐up of infants of diabetic mothers suggests that exposure to maternal diabetes in utero increases the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes for these children in the future (Dabelea 2000).

Previous gestational diabetes

Gestational diabetes mellitus is defined as "carbohydrate intolerance resulting in hyperglycaemia of variable severity with onset or first recognition during pregnancy" (WHO 1999). The reported incidence of gestational diabetes varies between different populations and the method and criteria by which the diagnosis is made, with studies estimating incidence rates that range between 1% and 28% (Jiwani 2012). Gestational diabetes is associated with an increased risk of a number of adverse perinatal outcomes including macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, perineal trauma, pre‐eclampsia, and neonatal hypoglycaemia (Reece 2010). Although gestational diabetes resolves in 90% of cases, women with a history of gestational diabetes represent a unique group of women who are at significant risk for developing recurrent gestational diabetes and later established diabetes (Kim 2002; Kim 2007). It has been estimated that there is a 2% risk of progression to established diabetes in the subsequent pregnancy for women with gestational diabetes (Khambalia 2013).

Despite the potential need for intervention for these groups of women, there is limited evidence about the use of oral anti‐diabetic agents preconceptionally or during pregnancy.

Description of the intervention

Management of established diabetes before pregnancy, and pre‐existing diabetes during pregnancy

The occurrence of adverse outcomes in women with pre‐existing diabetes and their infants is inversely related to the level of glycaemic control achieved during pregnancy. Therefore, there is a strong focus on the management of maternal glucose concentrations in preconception and antenatal care of women with established diabetes.

Prior to conception, it is recommended that women with established diabetes receive multidisciplinary care including an assessment of diabetes complications, advice on glycaemic control, diet, the importance of family planning, maternal diabetes complications and fetal risks (ADA 2015; ADIPS 2005; CDA 2013; NICE 2015). Oral anti‐diabetic agents are more commonly used by people with type 2 diabetes than people with type 1 diabetes, who commonly will not achieve adequate glycaemic control on oral anti‐diabetics alone. Currently, it is recommended that oral anti‐diabetic agents be substituted for insulin in women planning pregnancy and during pregnancy (ADA 2015; ADIPS 2005; CDA 2013; NICE 2015).

Oral anti‐diabetic agents, also referred to as oral hypoglycaemic agents or oral antihyperglycaemic agents, act in a variety of ways. While widely used in men and women with type 2 diabetes, their use in women with established diabetes who are planning a pregnancy or are pregnant has been controversial, with conflicting reports about their safety. As a result of these concerns, insulin has been the preferred agent for glycaemic management in women with pre‐existing diabetes during pregnancy (ADA 2015; ADIPS 2005; CDA 2013; NICE 2015). Current recommendations suggest that women planning or continuing a pregnancy use insulin, although oral anti‐diabetic agents may be considered on an individual basis, since the harm from uncontrolled diabetes may outweigh any potential harm from the oral agents.

Lack of safety data for the use of oral anti‐diabetic agents in pregnancy has prevented them from being routinely recommended for use during pregnancy. It has also been argued that the use of oral anti‐diabetic agents alone, including glyburide (glibenclamide) and metformin, may be inadequate to manage the post‐prandial glycaemic peaks associated with type 2 diabetes successfully (Jovanovic 2007). However, oral anti‐diabetic agents are convenient, may be preferable to insulin injections, and may not require the intensive education associated with insulin therapy. Where oral agents alone are not sufficient to achieve glycaemic control, they may be used in combination to reduce the frequency or dose of insulin.

A retrospective study of women in South Africa with established diabetes, who remained on oral anti‐diabetic agents, transferred from oral agents to insulin, or transferred from diet alone to insulin, reported no difference in fetal anomaly rates (Ekpebegh 2007). This study, however, did report a significantly higher perinatal mortality rate for women continuing on oral anti‐diabetic agents alone compared with women who received insulin. Meta‐analyses and reviews of observational studies have been unable to provide definitive conclusions about the effects of oral anti‐diabetic agents in pregnancy (Gutzin 2003; Ho 2007).

The Tieu 2017 Cochrane Review found no evidence of benefit for preconception care compared with no preconception care, or any protocol of preconception care over another, for women with established diabetes. Cochrane Reviews have also assessed various management strategies during pregnancy for women with pre‐existing diabetes. The O'Neill 2017 Cochrane Review, which assessed different insulin types and regimens, recently concluded that no firm conclusions could be drawn on the basis of current evidence. The Farrar 2016 Cochrane Review similarly concluded that there is currently no evidence to support the use of one particular form of insulin administration over another. Furthermore, reviews of different intensities of glycaemic control (Middleton 2016), and techniques of monitoring blood glucose for women with pre‐existing diabetes in pregnancy (Moy 2014), have not been able to reach firm conclusions about best practice either.

Management of previous gestational diabetes before and during pregnancy

While the importance of management for women with gestational diabetes has been recognised (Crowther 2005; Landon 2009), the most appropriate form of treatment is uncertain (Alwan 2009). The Cochrane Review 'Treatment for gestational diabetes' concluded that while women with gestational diabetes should be considered for specific treatment in addition to routine antenatal care, the decision about whether to offer dietary advice or more intensive treatment (including insulin or oral agents) was unclear (Alwan 2009), as were the effects on long‐term outcomes for the women and their infants (Alwan 2009). This review assessed a range of management options, including the use of oral anti‐diabetic agents such as metformin and glyburide (glibenclamide). The review found that women who received oral anti‐diabetic agents compared with insulin were less likely to have a caesarean section, and their infants were less likely to develop neonatal hypoglycaemia; there were however, no differences in other important outcomes such as induction of labour and shoulder dystocia (Alwan 2009).

The Alwan 2009 Cochrane Review has now been separated into reviews that address lifestyle interventions (Brown 2017a), dietary supplementation with myo‐inositol (Brown 2016a), different intensities of glycaemic control (Martis 2016), as well as insulin (Brown 2016b), and oral anti‐diabetic agents (Brown 2017b). The recent Brown 2017b review concluded that there are insufficient data from comparisons of oral anti‐diabetic agents versus placebo/standard care (lifestyle advice) in women with gestational diabetes to inform clinical practice, or to draw any meaningful conclusions regarding the benefits or harms of one oral anti‐diabetic agent over another (e.g. metformin versus glibenclamide; and glibenclamide versus acarbose) (Brown 2017b). The Brown 2016b review, which will include comparisons of oral anti‐diabetic agents with insulin is currently being prepared.

The Tieu 2013 Cochrane Review found no evidence to assess the role of interconception care for women with a history of gestational diabetes.

How the intervention might work

Oral anti‐diabetic agents

Common anti‐diabetic agents include sulfonylureas, biguanides, thiazolidinediones, alpha‐glucosidase inhibitors, meglitinides and peptide analogues. Biguanides, including metformin, reduce peripheral insulin resistance, inhibit gluconeogenesis and reduce plasma triglyceride concentrations (DeFronzo 1995; Stumvoll 1995; Yogev 2004). Since metformin does cross the placenta, there have been concerns about its use in pregnancy (Hellmuth 2000; Kovo 2007; Slocum 2002). Since the publication of the Alwan 2009 Cochrane Review, the use of metformin for the treatment of gestational diabetes has been evaluated in a large randomised controlled trial (Rowan 2008a). This trial found that compared with insulin, while metformin was not associated with increased perinatal complications, it was associated with a tendency for less severe neonatal hypoglycaemia, less maternal weight gain and greater maternal acceptability. In this study metformin was commenced in the latter half of pregnancy, between 20 and 34 weeks' gestation.

There is no definitive evidence of the safety of metformin in pregnancies complicated by pre‐existing diabetes (Ho 2007). However, since it has been suggested that metformin increases the incidence of pregnancy and reduces pregnancy loss in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), there are data available from babies born to mothers with PCOS who took metformin during pregnancy. Follow‐up at 18 months of age of 126 infants born to 109 mothers with PCOS, who conceived while taking metformin and continued to take it during pregnancy, reported that the metformin‐exposed infants were of similar size and had similar motor‐social development to infants of women not known to have PCOS (Brock 2005; Glueck 2004).

Sulfonylureas, for example glyburide (glibenclamide) and glimepiride, enhance insulin secretion and peripheral tissue sensitivity to insulin while also reducing hepatic clearance of insulin (DeFronzo 1984; Homko 2006; Simonson 1984; Yogev 2004). The main side effect of these agents is hypoglycaemia, and while first generation sulfonylureas cross the placenta, it is unclear whether second generation agents, including glyburide (glibenclamide), do, and what effect this might have on the developing fetus (Jovanovic 2007; Kraemer 2006; Sivan 1995; Slocum 2002). The ability of sulfonylureas to stimulate fetal hyperinsulinaemia is a major concern (Coetzee 2007). However, a randomised controlled trial of treatment of women with gestational diabetes, included in the Alwan 2009 Cochrane Review, which investigated glyburide (glibenclamide; a second generation sulfonylurea), or insulin, found that there were no differences in macrosomic or large‐for‐gestational‐age infants between the two groups (Langer 2000a).

Alpha‐glucosidase inhibitors such as acarbose and miglitol reduce postprandial glucose concentrations by decreasing the breakdown and absorption of carbohydrates in the intestine (Slocum 2002; Yogev 2004). There is little evidence of the use of these agents in pregnancy (Ho 2007). Alpha‐glucosidase inhibitors are typically used in combination with other oral anti‐diabetic agents or insulin (Yogev 2004).

Thiazolidinediones, including rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, result in increased insulin sensitivity and decreased lipid availability (Slocum 2002; Yogev 2004). There is little evidence about the use of thiazolidinediones in pregnancy (Ho 2007), although, placental transfer of thiazolidinediones has been reported (Chan 2005). Furthermore, concerns have been expressed about the use of rosiglitazone in type 2 diabetes due to an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes (Nissen 2007).

Meglitinides increase pancreatic insulin secretion. There is little evidence of their use in pregnancy (Slocum 2002), and a similar absence of evidence for the use of peptide analogues such as incretin mimetics and dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors.

Why it is important to do this review

With the rising prevalence of type 1, type 2 and gestational diabetes, there is an increasing need for evidence‐based management of women with established diabetes or a history of gestational diabetes both preconceptionally and during pregnancy. While most guidelines recommend the use of insulin in place of oral anti‐diabetic agents, oral agents may have benefits, particularly in terms of acceptability and adherence. However, there is little evidence about the effects of these agents on maternal and infant health. It is necessary, therefore, to assess the benefits and harms of anti‐diabetic agents in women with established diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes who are planning a pregnancy, and pregnant women with pre‐existing diabetes mellitus. The use of oral anti‐diabetic agents for the management of gestational diabetes in a current pregnancy was previously evaluated in the Cochrane Review 'Treatment of gestational diabetes' (Alwan 2009); specific assessments of oral anti‐diabetic agents (Brown 2017b), and comparisons of these agents with insulin for women with gestational diabetes (Brown 2016b), are made in two new Cochrane Reviews.

Objectives

To investigate the effect of oral anti‐diabetic agents in women with established diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes who are planning a pregnancy, or pregnant women with pre‐existing diabetes, on maternal and infant health. The use of oral anti‐diabetic agents for the management of gestational diabetes in a current pregnancy is evaluated in a separate Cochrane Review.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We planned to include randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials, and cluster‐randomised trials, and to exclude cross‐over trials. We planned to include trials published in abstract form only where there was sufficient information available to assess study eligibility and risk of bias.

Types of participants

Women with established type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus, impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes mellitus planning a pregnancy or pregnant women with pre‐existing type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus. Trials involving women with gestational diabetes in a current pregnancy were excluded from this review.

Types of interventions

Oral anti‐diabetic agent versus no medication

Oral anti‐diabetic agent versus another oral anti‐diabetic agent

Oral anti‐diabetic agent versus insulin

Oral anti‐diabetic agent versus insulin plus an oral anti‐diabetic agent

Oral anti‐diabetic agent plus insulin versus insulin

Different regimens of any of the above

Types of outcome measures

For this update, we used the standard outcome set agreed by consensus between review authors of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth systematic reviews for prevention and treatment of gestational diabetes and pre‐existing diabetes.

Primary outcomes

Mother

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (including pre‐eclampsia, pregnancy‐induced hypertension, eclampsia)

Caesarean section

Infant/child/adult

Large‐for‐gestational age

Perinatal mortality (stillbirth and neonatal mortality)

Neonatal mortality or morbidity composite (e.g. perinatal mortality, shoulder dystocia, bone fracture, and admission to the neonatal unit)

Childhood/adulthood neurosensory disability

Secondary outcomes

Mother: short‐term

Spontaneous abortion/miscarriage

Gestational diabetes mellitus

Induction of labour

Perineal trauma

Placental abruption

Postpartum haemorrhage

Postpartum infection

Weight gain during pregnancy

Adherence to the intervention

Sense of well‐being and quality of life

Views of the intervention

Adverse effects of the intervention

Breastfeeding at discharge, six weeks postpartum, six months or longer

Use of additional pharmacotherapy for glycaemic control

Glycaemic control during/end of treatment (e.g. blood glucose or haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c))

Hypoglycaemia

Mortality

Complications of diabetes (retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease)

Mother: long‐term

Postnatal depression

Postnatal weight retention or return to prepregnancy weight

Body mass index (BMI)

Gestational diabetes mellitus in a subsequent pregnancy

Type 1 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes

Impaired glucose tolerance

Cardiovascular health (as defined by trialists, including blood pressure, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome)

Infant

Congenital anomaly

Stillbirth

Neonatal mortality

Gestational age at birth

Preterm birth (less than 37 weeks' gestation and less than 32 weeks' gestation)

Apgar score (less than seven at five minutes)

Macrosomia (birthweight greater than 4000 g and birthweight greater than 4500 g)

Small‐for‐gestational age

Birthweight and Z score

Head circumference and Z score

Length and Z score

Ponderal index

Adiposity

Shoulder dystocia

Bone fracture

Nerve palsy

Respiratory distress syndrome

Hypoglycaemia

Hyperbilirubinaemia

Hypocalcaemia

Polycythaemia

Infection

Relevant biomarker changes associated with the intervention (e.g. cord C peptide, cord insulin)

Child/adult

Weight and Z scores

Height and Z scores

Head circumference and Z scores

Adiposity (e.g. as measured by BMI, skinfold thickness)

Cardiovascular health (as defined by trialists including blood pressure, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome)

Type 1 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes

Impaired glucose tolerance

Employment, education and social status/achievement

Health service

Number of hospital or health professional visits (e.g. midwife, obstetrician, physician, dietitian, diabetic nurse)

Number of antenatal visits or admissions

Length of antenatal stay

Neonatal intensive care unit/nursery admission

Duration of stay in neonatal intensive care unit/nursery

Length of postnatal stay (mother)

Length of postnatal stay (baby)

Costs to families associated with the management provided

Costs associated with the intervention

Cost of maternal care

Cost of offspring care

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (31 October 2016).

The Register is a database containing over 23,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set that has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification; Ongoing studies).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeTieu 2010.

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the 29 new reports that were identified as a result of the updated search, and four reports that were reassessed from the previous version of this review.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy for inclusion. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014), and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding eligibility or data was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

For each included study we assessed the method as being at:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study we described the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as being at:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

For each included study we described the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding was unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as being at:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

For each included study we described the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as being at:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

For each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, we described the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses that we undertook.

We assessed methods as being at:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

For each included study we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as being at:

low risk of bias (where it was clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes were reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

For each included study we described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to have an impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses (Sensitivity analysis).

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update the quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook for the following outcomes.

Mother

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (including pre‐eclampsia, pregnancy‐induced hypertension, eclampsia)

Caesarean section

Gestational diabetes mellitus or type 2 diabetes (if applicable)

Induction of labour

Perineal trauma

Postnatal depression

Postnatal weight retention or return to prepregnancy weight

Infant/child/adult

Large‐for‐gestational age

Perinatal mortality (stillbirth and neonatal mortality)

Neonatal mortality or morbidity composite (e.g. perinatal mortality, shoulder dystocia, bone fracture, and admission to the neonatal unit)

Hypoglycaemia

Childhood/adulthood neurosensory disability

Childhood/adulthood adiposity

Childhood/adulthood diabetes

We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager 5 in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach, which uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates, or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

We used the mean difference where outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome through different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials. In future updates of the review, if cluster‐randomised trials are included, we will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs, and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and we will perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials are an inappropriate design for this intervention.

Cross over trials are not a suitable design for trials looking at interventions in labour and have been excluded.

Studies with more than two groups

In Ainuddin 2015, results for the group randomised to metformin were reported separately for those women who remained on metformin alone and those women who subsequently received insulin in addition to metformin. We combined the metformin groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Chapter 16, section.5.4), by considering the metformin alone and the metformin plus insulin groups together.

In Notelovitz 1971, we were unable to report any results from this four‐armed RCT (chlorpropamide, tolbutamide, insulin and diet therapy) as women with type 2 diabetes or gestational diabetes mellitus were not reported separately. However, if we had been able to obtain these data separately, we would have created three single pair‐wise comparisons (by combining both oral anti‐diabetic agents compared with insulin, both oral anti‐diabetic agents compared with diet therapy and one oral anti‐diabetic agent compared with the other anti‐diabetic agent).

Dealing with missing data

We noted levels of attrition for included studies. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, that is, we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I² was greater than 30% and either Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by prespecified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

As there were fewer than 10 trials included in the analyses, we were unable to investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. In future updates, as more data become available, we will investigate reporting biases using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by visual assessment, we will investigate further.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: that is, where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged to be sufficiently similar.

In future updates, with more included studies, if there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity is detected, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials. Where we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses but there were insufficient data to do so.

Type of diabetes (e.g. established type 1 diabetes mellitus versus established type 2 diabetes mellitus versus impaired glucose tolerance versus previous gestational diabetes mellitus).

Gestational age of women at randomisation (e.g. preconception versus first trimester versus second trimester versus third trimester).

Glycaemic control prior to pregnancy/randomisation (e.g. glycaemic targets achieved versus not achieved).

We planned to use only primary outcomes in subgroup analyses. In future updates, we plan to assess differences between subgroups by interaction tests available in RevMan 2014. We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor‐quality studies (rated at unclear or high risk of bias for these components) being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this made any difference to the overall result, however there were insufficient data to do this.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In the previous version on this review we identified no trials eligible for inclusion (Tieu 2010).

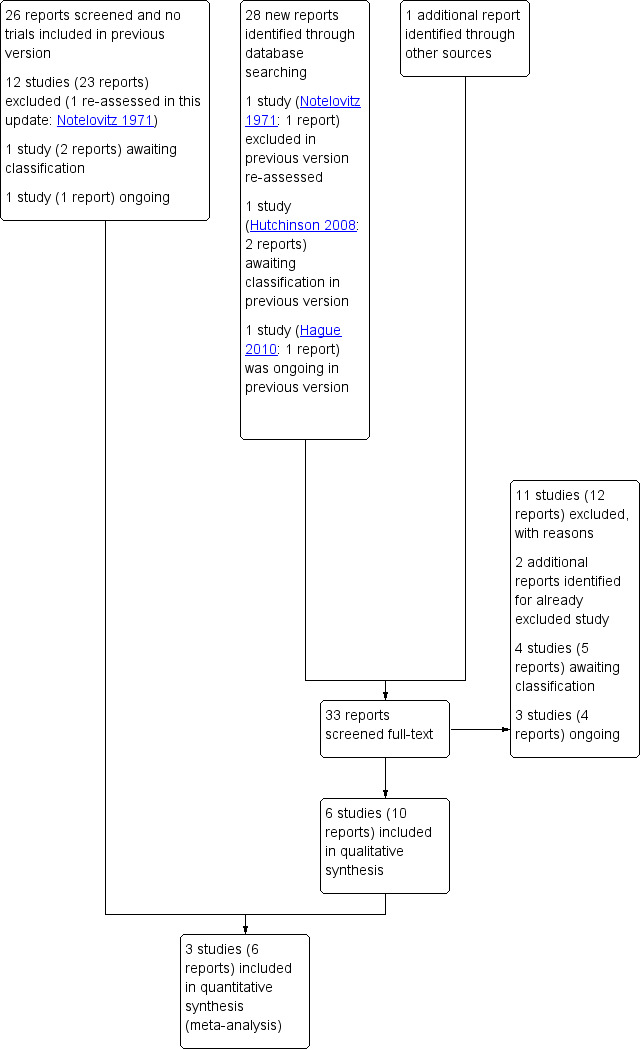

An updated search was carried out in October 2016; 29 new reports were identified. We reassessed three studies (four reports) which were either excluded (Notelovitz 1971), ongoing (Hague 2010), or awaiting assessment (Hutchinson 2008) in the previous version. Some studies were published in multiple reports. In total, we have now included six studies and excluded 22. Four studies are awaiting further classification, and three studies are ongoing. See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

To date, three of the four studies awaiting further classification have been published as abstracts only (Coiner 2014; Hutchinson 2008; Reyes‐Munoz 2014); we have contacted the trial authors regarding availability of full reports in order to assess study eligibility and risk of bias further. The fourth study provided insufficient detail for us to determine study eligibility (specifically regarding whether women with established diabetes were included) (Waheed 2013). For further details see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

The three ongoing trials are all assessing metformin in pregnant women with type 2 diabetes (Feig 2011), gestational diabetes or type 2 diabetes (Sheizaf 2006), or at high risk for gestational diabetes (Van der Linden 2014). For further details see Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Included studies

We included six trials in this review (Ainuddin 2015; Beyuo 2015; Hickman 2013; Ibrahim 2014; Notelovitz 1971; Refuerzo 2015). However, as three of the trials had mixed populations (women with gestational diabetes and women with established diabetes) (Beyuo 2015; Ibrahim 2014; Notelovitz 1971), and did not report data separately for the relevant subset of women for this review, we have only included outcome data from three of the included trials (Ainuddin 2015; Hickman 2013; Refuerzo 2015). The Hickman 2013 trial also had a mixed population, but the trial authors provided data for the group of women with established diabetes separately for inclusion in this review. We have contacted the authors of the three trials with mixed populations to ask about the availability of data for women with established diabetes, and await responses. We describe the characteristics of the six included trials below.

Settings

The included trials were conducted in Pakistan (Ainuddin 2015), Ghana (Beyuo 2015), Egypt (Ibrahim 2014), South Africa (Notelovitz 1971) and the USA (Hickman 2013; Refuerzo 2015).

Dates when study conducted

Ainuddin 2015 was conducted from January 2009 to January 2014, Beyuo 2015 from January 2013 to October 2015, Hickman 2013 from July 2008 to December 2009, Ibrahim 2014 from August 2011 to April 2012, and Refuerzo 2015 from September 2009 to August 2011. Notelovitz 1971 did not report when the study was conducted.

Funding

Funding sources were reported by four of the trials; Hickman 2013 and Refuerzo 2015 were funded by non‐commercial organisations; Notelovitz 1971 was funded by a commercial organisation (Pfizer Laboratories Ltd); and Ibrahim 2014 identified the trialists as the source of funding. Ainuddin 2015 did not describe source of funding and Beyuo 2015 reported “no source of funding”.

Declarations of interest

Three of the trials reported that there were no conflicts of interests for any of the authors (Ainuddin 2015; Beyuo 2015; Ibrahim 2014). The remaining three trials did not report any information regarding declarations of interest (Hickman 2013; Notelovitz 1971; Refuerzo 2015).

Participants

Overall, the six trials randomised 707 women and their babies, with sample sizes ranging from 25 women in Refuerzo 2015 to 250 women in Ainuddin 2015.

Two trials included only women with established diabetes; both included women with singleton pregnancies, with type 2 diabetes diagnosed prior to pregnancy, and cases of newly diagnosed overt diabetes in pregnancy beyond the first trimester (Ainuddin 2015), or a self‐reported history of type 2 diabetes for less than 10 years prior to 20 weeks' gestation (Refuerzo 2015).

Four trials included mixed populations of women with gestational diabetes and established type 2 diabetes, prior to 20 weeks' gestation (Hickman 2013), from 20 to 30 weeks' gestation (Beyuo 2015), between 20 and 34 weeks' gestation (Ibrahim 2014), or whose duration of pregnancy would allow at least six consecutive weeks of treatment (Notelovitz 1971).

Interventions

While five of the six included trials compared metformin with insulin (Ainuddin 2015; Beyuo 2015; Hickman 2013; Ibrahim 2014; Refuerzo 2015), their intervention and control regimens varied. Four of the trials assessed 500 mg metformin daily (Ainuddin 2015; Beyuo 2015; Hickman 2013; Refuerzo 2015), which was increased, as required, up to a maximum of 2500 mg daily in the intervention group. In these four trials, if glycaemic control (variously defined) was not achieved with the maximum dose of metformin, insulin was added as supplementary therapy. In the fifth trial (Ibrahim 2014), women commenced on 1500 mg metformin daily, which was raised to 2000 mg daily. In this trial, if glycaemic control was not achieved women were switched to a conventional insulin dose‐raising regimen (Ibrahim 2014). Insulin regimens in the comparison groups were broadly similar; it was commonly given in two doses, with the total daily dose titrated to achieve glycaemic control. Total daily doses were calculated as follows: in Ainuddin 2015 0.6 IU/kg body weight in first trimester, 0.7 IU/kg in second trimester, 0.8 IU/kg from 28 to 32 weeks, 0.9 IU/kg from 32 to 36 weeks, 1 IU/kg from 36 weeks onwards; in Beyuo 2015 0.3 IU/kg body weight at initiation (20 to 30 weeks' gestation); in Hickman 2013 0.7 IU/kg bodyweight at initiation (prior to 20 weeks' gestation); and in Refuerzo 2015: 0.7 IU/kg bodyweight in the first trimester, 0.8 IU/kg in the second trimester, and 0.9 to 1.0 IU/kg/day in the third trimester. Ibrahim 2014 treated women with poor glycaemic control with a daily dose of at least 1.12 IU/kg bodyweight.

The Notelovitz 1971 trial had four groups that compared chlorpropamide, tolbutamide, insulin and diet restriction alone; no further details were provided regarding specific regimens.

For detailed descriptions of the included studies, see Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 22 studies. Seventeen of the trials evaluated treatments for gestational diabetes (Anjalakshi 2007; Bertini 2005; Casey 2015; Corrado 2011; George 2015; Golladay 2005; Hague 2003; Langer 2000b; Martinez 2010; Moore 2005; Moore 2007; Mukhopadhyay 2012; Niromanesh 2012; Rowan 2008b; Singh 2011Wali 2012; Zanganeh 2010), and one assessed treatments for women with hyperglycaemia that did not meet the criteria for gestational diabetes (Myers 2013); these trials are, or will be, considered in the other relevant Cochrane Reviews. Three trials evaluated treatment specifically for women with polycystic ovary syndrome (Carlsen 2007; Vanky 2004; Vanky 2005). One potentially relevant trial was planned in women with previous gestational diabetes, but subsequently not conducted (Hague 2010). For further details see Characteristics of excluded studies.

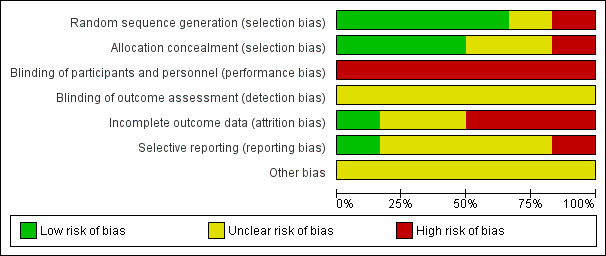

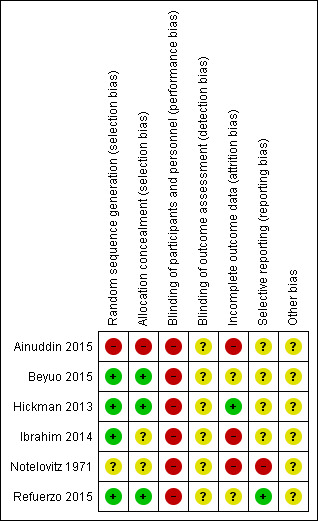

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall we judged the trials to be at varying risks of bias; see Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

We judged that three of the six trials used adequate methods for sequence generation and allocation concealment, and thus were at low risk of selection bias (Beyuo 2015; Hickman 2013; Refuerzo 2015). One trial reported an adequate method for sequence generation, but the method of allocation concealment was unclear (Ibrahim 2014). Another trial did not report the methods for sequence generation or allocation concealment (Notelovitz 1971), and so we judged this trial to be at an unclear risk of selection bias. The final trial used quasi‐randomisation, and we judged it to be at high risk of selection bias (Ainuddin 2015).

Blinding

We judged all of the six included trials to be at high risk of performance bias (blinding of women and study personnel was not possible due to the nature of the differing treatments received by the intervention and comparison groups) (Ainuddin 2015; Beyuo 2015; Hickman 2013; Ibrahim 2014; Notelovitz 1971; Refuerzo 2015). We judged all six trials to be at an unclear risk of detection bias; three trials were reported to be 'open label', but none of these trials specifically reported on whether it was possible to blind outcome assessment (Ainuddin 2015; Beyuo 2015; Refuerzo 2015), and the other three trials provided no details (Hickman 2013; Ibrahim 2014; Notelovitz 1971).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged only one trial to be at low risk of attrition bias (Hickman 2013), as over 90% of the women randomised were included in the analyses, and loss to follow‐up and exclusions occurred in similar numbers, and for similar reasons between groups. We judged two trials to be at an unclear risk of attrition bias; in Beyuo 2015 there appeared to be higher attrition in the insulin group, with 75% of women completing the study, compared with 90% in the metformin group; and in Refuerzo 2015 only 84% of the women randomised were analysed (21/25). We judged three trials to be at a high risk of attrition bias (Ainuddin 2015; Ibrahim 2014; Notelovitz 1971); in Ainuddin 2015 almost 20% of women were excluded from the analyses, and notably, in the analyses, the metformin group was separated into metformin alone, and metformin plus insulin; we combined these groups for the purpose of this review. Ibrahim 2014 reported that 'per‐protocol treatment analyses' were performed (with women who chose to switch from their allocated group excluded from the analyses); and for Notelovitz 1971 it also appeared that analyses were not intention‐to‐treat, as it was reported that, "In the final analysis" women were analysed in the group in which they "completed treatment" or "were treated with for the greater part of their pregnancy".

Selective reporting

We judged only one trial to be at a low risk of reporting bias, as the expected outcomes were reported as they were in the trial registration (Refuerzo 2015). We judged four of the trials to be at an unclear risk of reporting bias, due to the provision of limited detail regarding prespecified outcomes in the trial registrations available, or limited reporting of expected outcomes to date, or both (Ainuddin 2015; Beyuo 2015; Hickman 2013; Ibrahim 2014). We judged one trial to be at a high risk of reporting bias, as it did not prespecify outcomes, and provided incomplete reporting of some outcomes (Notelovitz 1971).

Other potential sources of bias

We judged all six trials to be at unclear risk of other bias. Four of the trials appeared to have imbalances in baseline characteristics despite randomisation (Ainuddin 2015; Beyuo 2015; Hickman 2013; Refuerzo 2015), while the other two provided very limited methodological details and information regarding the comparability of groups at baseline (Ibrahim 2014; Notelovitz 1971).

Effects of interventions

Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin

Mother: primary outcomes

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Both Ainuddin 2015 and Refuerzo 2015 reported on pre‐eclampsia and overall, there was no clear difference between the metformin and insulin groups (risk ratio (RR) RR 0.63, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.33 to 1.20; RCTs = 2; participants = 227; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1). In Ainuddin 2015, however, women receiving metformin, were less likely to have pregnancy‐induced hypertension (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.91; RCTs = 1; participants = 206; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.2).

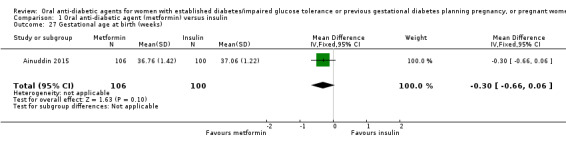

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 1 Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: pre‐eclampsia.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 2 Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: pregnancy‐induced hypertension.

Caesarean section

Pooling of data from Ainuddin 2015, Hickman 2013 and Refuerzo 2015 showed that women in the metformin group were less likely to have a caesarean section birth compared with those in the insulin group (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.88; RCTs = 3; participants = 241; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

Infant/child/adult

Large‐for‐gestational age

There was no clear difference between the metformin and insulin groups for large‐for‐gestational age infants in Ainuddin 2015 (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.72; RCTs = 1; participants = 206; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 4 Large‐for‐gestational age.

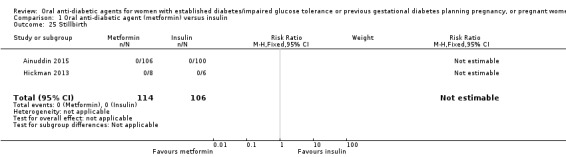

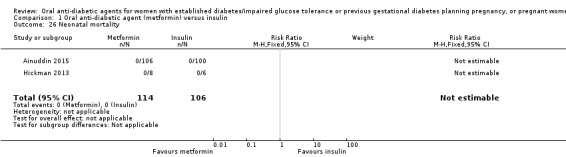

Perinatal mortality (stillbirth and neonatal mortality)

There were no perinatal deaths in Ainuddin 2015 or Hickman 2013 (RCTs = 2; participants = 220; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 5 Perinatal mortality.

Neonatal mortality or morbidity composite

Ainuddin 2015, Hickman 2013 and Refuerzo 2015 did not report on this outcome.

Childhood/adulthood neurosensory disability

Ainuddin 2015, Hickman 2013 and Refuerzo 2015 did not report on this outcome.

Mother: short‐term secondary outcomes

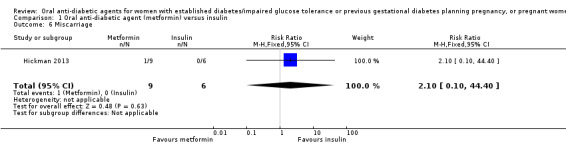

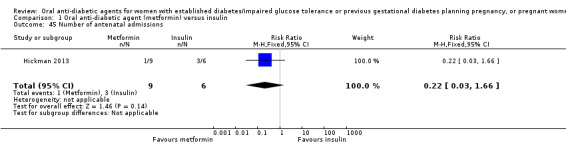

In the metformin group in Hickman 2013, one woman experienced a 13‐week intrauterine fetal death attributed to a large subchorionic haematoma noted on ultrasound at 12 weeks (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 6 Miscarriage.

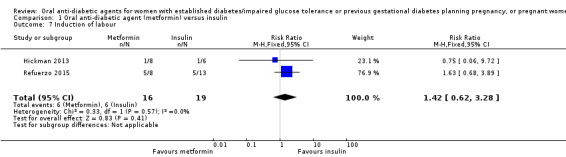

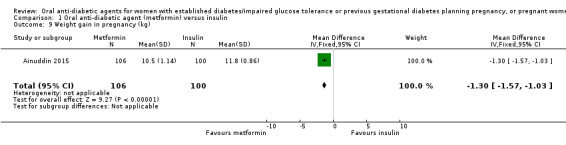

Meta‐analysis of data from Hickman 2013 and Refuerzo 2015 showed no clear difference between the metformin and insulin groups for induction of labour on (RR 1.42, 95% CI 0.62 to 3.28; RCTs = 2; participants = 35; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.7). In Hickman 2013, no women had postpartum haemorrhage that required treatment (Analysis 1.8). In Ainuddin 2015, on average, women in the metformin group gained less weight in pregnancy than those in the insulin group (mean difference (MD) ‐1.30 kg, 95% CI ‐1.57 to ‐1.03; RCTs = 1; participants = 206; Analysis 1.9). Hickman 2013 additionally reported on weight gain during pregnancy (this was presented as groups medians, with interquartile ranges in Analysis 1.10) with results also favouring the metformin group.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 7 Induction of labour.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 8 Postpartum haemorrhage.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 9 Weight gain in pregnancy (kg).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 10 Weight gain in pregnancy (kg).

| Weight gain in pregnancy (kg) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Metformin (N=9) | Insulin (N=6) |

| Hickman 2013 | Median (IQR): 3.16 (2.88, 4.50) | Median (IQR): 10.78 (8.15, 14.42) |

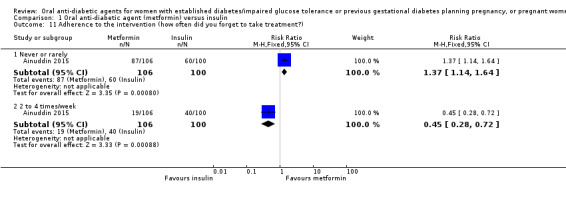

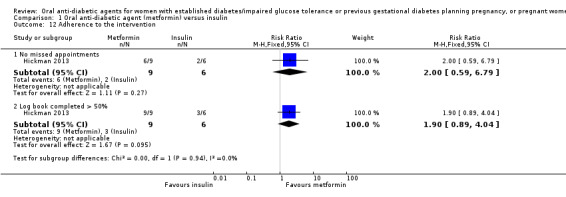

Adherence to the intervention was assessed in the Ainuddin 2015 trial. This showed that women in the metformin group were more likely to report 'never or rarely' forgetting to take their medication (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.64; RCTs = 1; participants = 206), and were less likely to report forgetting to take their medication two to four times per week (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.72; RCTs = 1; participants = 206; Analysis 1.11). In Hickman 2013, there was no clear difference between groups for the proportions of women who had missed appointments (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.59 to 6.79; RCTs = 1; participants = 15), or who completed more than 50% of their log book (RR 1.90, 95% CI 0.89 to 4.04; RCTs = 1; participants = 15; Analysis 1.12).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 11 Adherence to the intervention (how often did you forget to take treatment?).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 12 Adherence to the intervention.

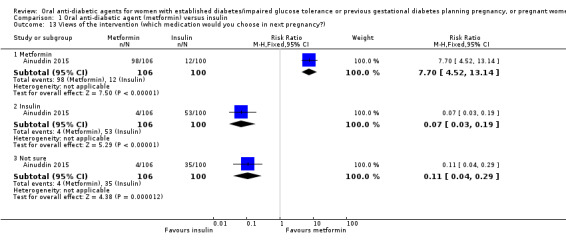

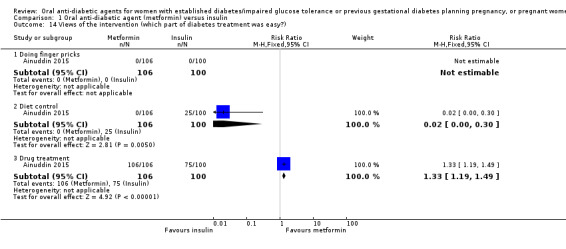

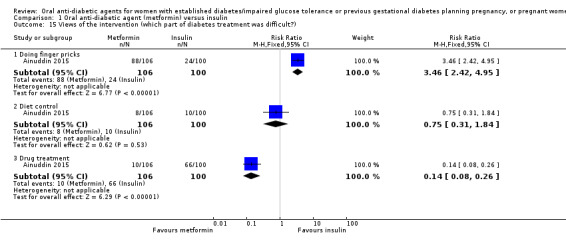

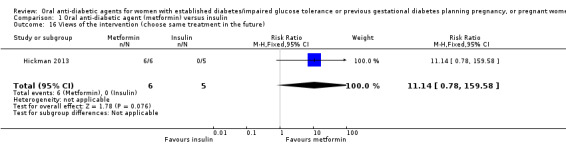

In Ainuddin 2015, women in the metformin group were more likely to report that they would choose metformin in their next pregnancy (RR 7.70, 95% CI 4.52 to 13.14; RCTs = 1; participants = 206), were less likely to report that they would choose insulin (RR 0.07, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.19; RCTs = 1; participants = 206), and were less likely to report that they were 'not sure' which medication they would choose (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.29; RCTs = 1; participants = 206) compared with women in the insulin group (Analysis 1.13). In the Ainuddin 2015 trial (Analysis 1.14), when asked what part of the diabetes treatment they found easy, no women in either the metformin or insulin groups reported that doing finger pricks was easy; no women in the metformin group, compared with 25/100 in the insulin group reported that dietary control was easy (RR 0.02, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.30; RCTs = 1; participants = 206), though more women in the metformin group reported that drug treatment was easy (RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.49; RCTs = 1; participants = 206; Analysis 1.14). In the Ainuddin 2015 trial (Analysis 1.15), when asked what part of the diabetes treatment they found difficult, women in the metformin group were more likely to report that doing finger pricks was difficult (RR 3.46, 95% CI 2.42 to 4.95; RCTs = 1; participants = 206), and were less likely to report that drug treatment was difficult (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.26; RCTs = 1; participants = 206) compared with women in the insulin group; there was no clear difference in the proportion of women finding diet control difficult in the metformin and insulin groups (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.84; RCTs = 1; participants = 206; Analysis 1.15). In Hickman 2013 women in the metformin group were more likely to report that they would choose the same treatment in the future (RR 11.14, 95% CI 0.78 to 159.58; RCTs = 1; participants = 11; P = 0.08; Analysis 1.16).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 13 Views of the intervention (which medication would you choose in next pregnancy?).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 14 Views of the intervention (which part of diabetes treatment was easy?).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 15 Views of the intervention (which part of diabetes treatment was difficult?).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 16 Views of the intervention (choose same treatment in the future).

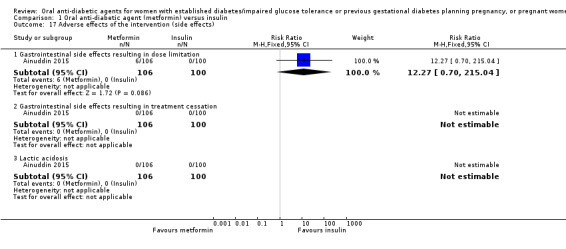

Regarding adverse effects of the intervention, in the Ainuddin 2015 trial, six women in the metformin group had gastrointestinal side effects resulting in dose limitation compared with none in the insulin group (RR 12.27, 95% CI 0.70 to 215.04; RCTs = 1; participants = 206). No women in either the metformin or insulin groups had gastrointestinal side effects that resulted in treatment cessation or lactic acidosis (Analysis 1.17).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 17 Adverse effects of the intervention (side effects).

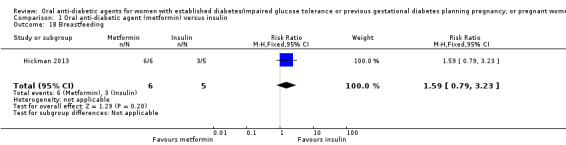

There was no clear difference between groups in Hickman 2013 for exclusive breastfeeding (time point not clear) (RR 1.59, 95% CI 0.79 to 3.23; RCTs = 1; participants = 11; Analysis 1.18).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 18 Breastfeeding.

With regard to the need for additional pharmacotherapy, Ainuddin 2015 reported that 105/125 women in the metformin group required supplemental insulin to maintain glycaemic control, while Refuerzo 2015 reported that none of the 25 women receiving metformin 'failed' with this therapy and needed insulin. Hickman 2013 reported that 3/9 women in the metformin group required supplemental insulin.

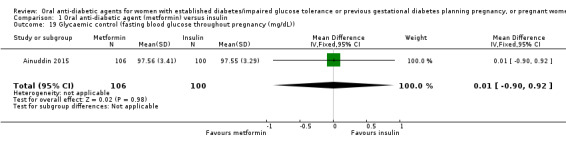

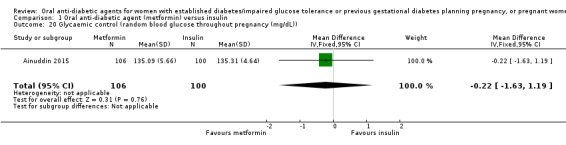

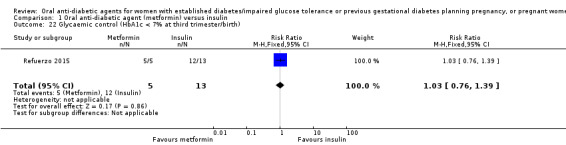

In Ainuddin 2015, with regard to glycaemic control, there was no clear difference in average fasting (MD 0.01 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.90 to 0.92; RCTs = 1; participants = 206; Analysis 1.19) or random blood glucose throughout pregnancy (MD ‐0.22 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐1.63 to 1.19; RCTs = 1; participants = 206; Analysis 1.20). Similarly, in Refuerzo 2015, there were no clear differences between groups in the average change in HbA1c from enrolment to the third trimester or birth (MD ‐0.48%, 95% CI ‐1.05 to 0.09; RCTs = 1; participants = 21; Analysis 1.21), or in the proportion of women with HbA1c less than 7% in the third trimester or at birth (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.39; RCTs = 1; participants = 18; Analysis 1.22). Hickman 2013 reported on glycaemic control (HbA1c in the second and third trimester, delivery glucose, and postpartum fasting glucose), which has been presented as group medians, with interquartile ranges in Analysis 1.23.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 19 Glycaemic control (fasting blood glucose throughout pregnancy (mg/dL)).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 20 Glycaemic control (random blood glucose throughout pregnancy (mg/dL)).

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 21 Glycaemic control (change in HbA1c from enrolment to third trimester/birth (%)).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 22 Glycaemic control (HbA1c < 7% at third trimester/birth).

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral anti‐diabetic agent (metformin) versus insulin, Outcome 23 Glycaemic control.

| Glycaemic control | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Metformin (N=8) | Insulin (N=6) |

| Hickman 2013 | HbA1c 2nd trimester (%) Median (IQR): 5.55 (5.54, 5.70) |

HbA1c 2nd trimester (%) Median (IQR): 5.70 (5.35, 6.28) |

| Hickman 2013 | HbA1c 3rd trimester (%) Median (IQR): 5.85 (5.73, 6.00) |

HbA1c 3rd trimester (%) Median (IQR): 5.85 (5.53, 6.55) |

| Hickman 2013 | Delivery glucose (mg/dL) Median (IQR): 96.00 (92.00, 113.00) |

Delivery glucose (mg/dL) Median (IQR): 127.50 (109.25, 122.00) |

| Hickman 2013 | Postpartum fasting glucose (mg/dL) Median (IQR): 97.50 (78.50, 108.75) |

Postpartum fasting glucose (mg/dL) Median (IQR): 125.50 (109.75, 136.75) |

Ainuddin 2015, Hickman 2013 and Refuerzo 2015 did not report on: gestational diabetes mellitus*; perinatal trauma; placental abruption; postpartum infection; sense of well‐being and quality of life; hypoglycaemia; mortality; or complications of diabetes.

*Outcome not relevant to trials involving women with established diabetes prior to pregnancy and pre‐existing diabetes in pregnancy

Mother: long‐term secondary outcomes

Ainuddin 2015, Hickman 2013 and Refuerzo 2015 did not report on: postnatal depression; postnatal weight retention or return to prepregnancy weight; body mass index; gestational diabetes in a subsequent pregnancy*; type 1 diabetes*; type 2 diabetes*; impaired glucose tolerance*; and cardiovascular health.

*Outcome not relevant to trials involving women with established diabetes prior to pregnancy and pre‐existing diabetes in pregnancy

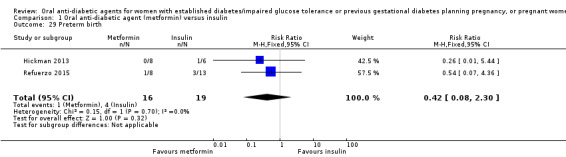

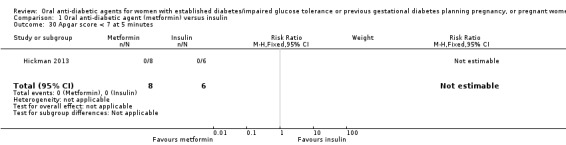

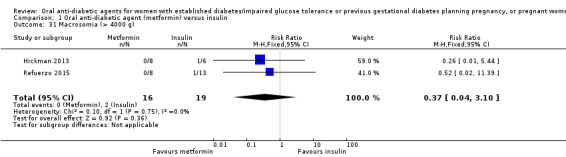

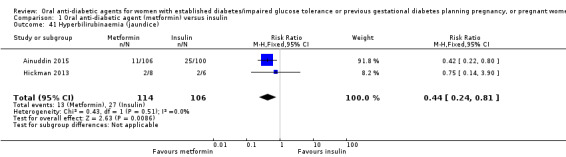

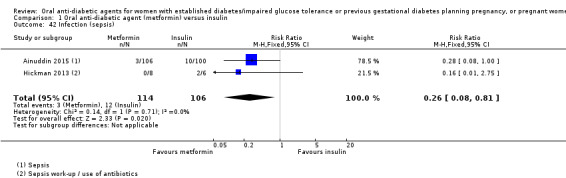

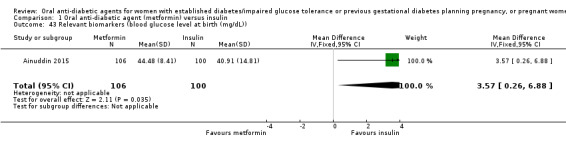

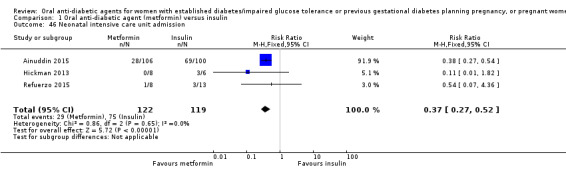

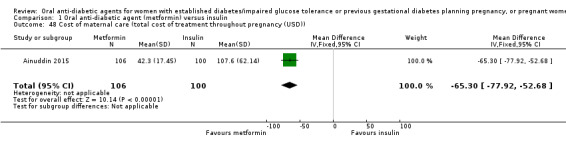

Infant: secondary outcomes