Abstract

The intestinal nematode parasite Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri exerts widespread immunomodulatory effects on both the innate and adaptive immune system of the host. Infected mice adopt an immunoregulated phenotype, with abated allergic and autoimmune reactions. At the cellular level, infection is accompanied by expanded regulatory T cell populations, skewed dendritic cell and macrophage phenotypes, B cell hyperstimulation and multiple localised changes within the intestinal environment. In most mouse strains, these act to block protective Th2 immunity. The molecular basis of parasite interactions with the host immune system centres upon secreted products termed HES (H. polygyrus excretory-secretory antigen), which include a TGF-β-like ligand that induces de novo regulatory T cells, factors that modify innate inflammatory responses, and molecules that block allergy in vivo. Proteomic and transcriptomic definition of parasite proteins, combined with biochemical identification of immunogenic molecules in resistant mice, will provide new candidate immunomodulators and vaccine antigens for future research.

Keywords: Alternatively activated macrophages, antibody isotype, cytokine, dendritic cell, immunosuppression, mucosal immunity, secreted immunomodulators, T cell subsets

Helminth parasites are widely recognised as masterful regulators of their host's immune response (Maizels, et al., 2004, Elliott, et al., 2007). In general, effective anti-helminth immunity depends on a strong Th2-type immune response (Anthony, et al., 2007, Allen and Maizels, 2011), but parasites divert or even suppress this pathway to ensure their survival. Defining the cellular and molecular basis for helminth immunomodulation will provide both new strategies for eradicating parasite infections (Hewitson, et al., 2009), and new understanding of the intimate co-evolution between helminths and the mammalian immune system (Maizels, 2009, Allen and Maizels, 2011).

Among the many immunomodulatory helminth species, one of the most potent examples is the murine intestinal nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus (Monroy and Enriquez, 1992), with a remarkable record of modifying a wide spectrum of host immune responses (Table 1). As well as notable effects on specific anti-parasite responses, modulation of systemic immune pathologies have been reported including intestinal food allergy (Bashir, et al., 2002), airway hyperresponsiveness (Wilson, et al., 2005, Kitagaki, et al., 2006), and bystander inflammatory responses to bacterial pathogens (Fox, et al., 2000). The particular value of the H. polygyrus model, compared to acute intestinal nematode infections such as Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, is that most strains of mice are unable to expel primary infections. This not only illustrates the parasite's immunosuppressive abilities, but provides a relatively stable system to analyse mechanisms of immune regulation in chronic infection. The parasitological basis of the model, and its value in exploring genetic variation in host susceptibility have recently been comprehensively reviewed (Behnke, et al., 2009); we will therefore focus primarily on the immunological aspects of this fascinating organism.

Table 1. Examples of immunomodulatory effects of H. polygyrus.

| Antigen-specific responses | |

| Antibody to SRBC inhibited in infection | (Shimp, et al., 1975, Ali and Behnke, 1983, Ali and Behnke, 1984) |

| Antibody to SRBC inhibited by adult worm homogenate, and by cells from mice given adult worm homogenate | (Pritchard, et al., 1984a) |

| Antibody to ovalbumin | (Boitelle, et al., 2005) |

| Immune cell functions | |

| Inhibition of DC responses to TLR ligation, and reduction of IL-12 secretion | (Segura, et al., 2007, Massacand, et al., 2009) |

| Expansion of Foxp3+ CD103+ Tregs | (Finney, et al., 2007, Rausch, et al., 2008) |

| Induction of bystander (OVA-specific) Foxp3+ Tregs | (Grainger, et al., 2010) |

| Autoimmunity | |

| Inhibits colitis in IL-10-deficient mice | (Elliott, et al., 2004, Hang, et al., 2010) |

| Inhibits TNBS-induced colitis | (Sutton, et al., 2008) |

| Inhibits Type I diabetes | (Saunders, et al., 2006, Liu, et al., 2009) |

| Allergy | |

| Inhibits airway allergic inflammation | (Wilson, et al., 2005, Kitagaki, et al., 2006) |

| Inhibits food allergy | (Bashir, et al., 2002) |

| Co-infections | |

| Reduces liver immunopathological reactions to schistosome eggs | (Bazzone, et al., 2008) |

| Exacerbates Plasmodium chabaudi and P. yoelii infections, suppressing IFN-γ responses | (Su, et al., 2005, Noland, et al., 2008, Helmby, 2009, Tetsutani, et al., 2009b) |

| Aggravates Citrobacter rodentium infection and colitis | (Chen, et al., 2005, Weng, et al., 2007) |

| Extends Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, Trichuris muris and Trichinella spiralis infections, suppresses IL-9 and mast cell response | (Colwell and Wescott, 1973, Jenkins and Behnke, 1977, Behnke, et al., 1978, Dehlawi, et al., 1987, Behnke, et al., 1993) |

| Modulates Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation | (Fox, et al., 2000) |

| Results in greater Eimeria facliformis proliferation | (Rausch, et al., 2010) |

| Inhibits protective CD8+ T cell responses to Toxoplasma gondii | (Khan, et al., 2008) |

| Reduced antibody responses to haemagglutinin in influenza A infections | (Chowaniec, et al., 1972) |

| Reduces response to malaria and Salmonella vaccination | (Druilhe, et al., 2006, Su, et al., 2006, Urban, et al., 2007) |

H. polygyrus : the parasite

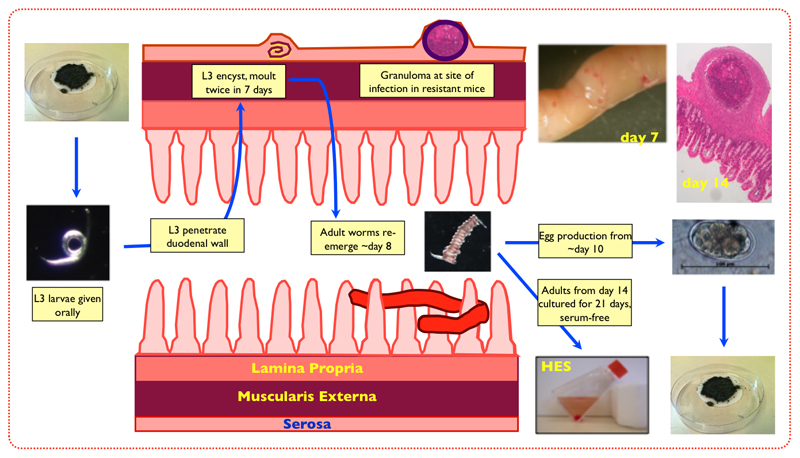

H. polygyrus occurs naturally in wild mouse populations and has clearly evolved a high level of adaptation to the murine immune system. It has a direct life cycle (Figure 1) in which infective larvae enter by the oral route and invade the duodenal mucosa, penetrating the entire muscular layer to reside beneath the serosal membrane. Around 8 days later, they return as adult worms into lumen, and following mating, egg production commences. Adult worms coil around villi and remain closely apposed to the proximal intestinal epithelium (Telford, et al., 1998). They are thought to feed on the epithelial cell layer (Bansemir and Sukhdeo, 1994) rather than penetrating it to access blood (unlike their near relatives, the hookworms).

Figure 1. Life cycle of H. polygyrus.

The laboratory isolate used in these studies is one which, reportedly, derives from a Californian source and while previously known as Nematospiroides dubius, was more recently designated H. polygyrus bakeri (Behnke, et al., 1991) to distinguish it from the type designated as H polygyrus polygyrus found in wild European mice. There are no diagnostic molecular or anatomical markers for either subspecies, and sequence comparisons remain preliminary (Cable, et al., 2006); hence the recent suggestion that the laboratory parasite should again be renamed (to H. bakeri (Behnke and Harris, 2010)) has not met with universal support (Tetsutani, et al., 2009a, Maizels, et al., 2011). For consistency with the established literature, we retain the name H. polygyrus in this article.

Immunity to H. polygyrus

H. polygyrus has been an invaluable model for understanding mechanisms of intestinal immunity in the submucosal tissue and luminal environments. The essential pre-requisites of immunity have been dissected using various immune gene-deficient mice, in the context either of primary exposure, or of immunity to challenge infection in mice drug-cured after 14 days of first infection (Table 2). In primary (Urban, et al., 1995) and secondary (Urban, et al., 1991, Liu, et al., 2004, Anthony, et al., 2007) settings, protective immunity is wholly dependent on CD4+ Th2-type components, although the precise mechanism for parasite elimination has yet to be defined.

Table 2. Immunity to H. polygyrus in genetically defined mice.

| Genotype (and background strain) | Primary Infection Phenotype | Challenge (Memory) Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inbred strains | |||

| A/J, CBA, C3H | Highly susceptible | Poorly resistant | (Prowse and Mitchell, 1980) (Behnke and Robinson, 1985) (Zhong and Dobson, 1996) (Behnke, et al., 2006) |

| C57BL/6 and C57BL/10 | Susceptible | Resistant | |

| BALB/c, DBA/2, 129/J | Intermediate | Resistant | |

| NIH, SJL, SWR | Low susceptibility | Resistant | |

| Cytokines and cytokine receptors | |||

| IL-2Rb Transgenic (C57BL/6) | Resistant | (Morimoto and Utsumiya, 2011) | |

| IL-6–/– (BALB/c or C57BL/6) | Resistant | Smith, K.A. et al, unpublished | |

| IL-9 Transgenic (FVB) | Resistant | (Hayes, et al., 2004) | |

| IL-10–/– (C57BL/6) | Decreased colitis | (Elliott, et al., 2004) | |

| IL-21R –/– (C57BL/6) | Deficient Th2, reduced granuloma numbers | Susceptible | (Fröhlich, et al., 2007) (King, et al., 2010) |

| IL-23p19 (C57BL/6) | Resistant | Grainger, J.R. et al, unpublished | |

| TGFbRIIdn (C57BL/6) | High Th1, Increased susceptibility | (Ince, et al., 2009) | |

| Humoral Immunity | |||

| µMT (fully B cell deficient) (C57BL/6) | Susceptible | (Perona-Wright, et al., 2008) (Wojciechowski, et al., 2009) |

|

| Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)–/– (C57BL/6) | Susceptible | (McCoy, et al., 2008) (Wojciechowski, et al., 2009) |

|

| JHD (B cell-deficient) (BALB/c) | Susceptible (but anti-fecundity intact) | (Liu, et al., 2010) | |

| JH–/– (C57BL/6) | Susceptible | (McCoy, et al., 2008) | |

| µS (lack exon required for secreted IgM) (C57BL/6) | Resistant | (Wojciechowski, et al., 2009) | |

| IgA–/– (C57BL/6) | Resistant (slightly less so than WT) | (McCoy, et al., 2008) | |

| IgE–/–(C57BL/6) | Resistant (weaker than WT) | (McCoy, et al., 2008) | |

| FcgR–/–(C57BL/6) | Resistant (weaker than WT) | (McCoy, et al., 2008) | |

| C3–/–(C57BL/6) | Resistant | (McCoy, et al., 2008) | |

| T cells and T cell signalling | |||

| CD28–/– (BALB/c) | Marginally higher fecundity | Diminished resistance | (Ekkens, et al., 2002) |

| CD80/CD86 –/– (BALB/c) | Higher fecundity | (Ekkens, et al., 2002) | |

| CD86 (B7-2)–/– (BALB/c) | Higher fecundity | (Greenwald, et al., 1999) | |

| OX40L–/– (BALB/c) | Higher fecundity | Diminished resistance | (Ekkens, et al., 2003) |

| Innate Immunity | |||

| MIF–/– (BALB/c) | More susceptible, do not expel | Filbey, K.J. et al, unpublished | |

| MyD88–/– (C57BL/6) | More resistant, more granulomas | Reynolds, L.A. et al, unpublished | |

| W/Wv (WBB6) | Higher fecundity | (Hashimoto, et al., 2010) | |

While primary infection is normally non-resolving, immunity can be induced by supply of exogenous IL-4 (given as a complex with IL-4R to prolong bioactive life), while antibody depletion of IL-4 partially compromises immunity to secondary reinfection (Urban, et al., 1991, Urban, et al., 1995). If anti-IL-4 is combined with anti-IL-4R antibody, protection is completely abolished, indicating that IL-13 acts redundantly with, but in a less effective manner than, IL-4 (Urban, et al., 1991). Epithelial cells are responsive to IL-4R signalling in infection (Shea-Donohue, et al., 2001), as are alternatively activated macrophages as discussed below (Anthony, et al., 2006), and hence protective immunity is likely to involve products of both these cell types as discussed below. In contrast, antibody-mediated depletion of IL-5 and consequent ablation of eosinophilia, has no effect on worm explusion following secondary infection (Urban, et al., 1991). A role for mast cells in primary immunity was suggested as IL-9 overexpressing transgenic mice are able to clear the infection, and this was associated with their high levels of mucosal mast cells (Hayes, et al., 2004, Morimoto and Utsumiya, 2011).

Following secondary infection, granulomatous reactions develop at the sites of larval tissue encystment, and these have long been associated with parasite killing (Chaicumpa, et al., 1977, Prowse, et al., 1979), although they have also been regarded as sites of tissue remodelling that may follow parasite exit (Sugawara, et al., 2011) and can persist long after worm expulsion (Cywinska, et al., 2004). More recent studies have shown that intestinal granulomas are foci of alternatively activated macrophages (Anthony, et al., 2006, Sugawara, et al., 2011), as well as granulocytes (Morimoto, et al., 2004) induced by IL-4 and/or IL-13-dependent IL-4Rα signalling. It is possible that differing cellular compositions within the intestinal granulomas, and/or the rate at which cell infiltration proceeds relative to maturation of the larva, are critical factors in whether parasite killing can occur within the tissue.

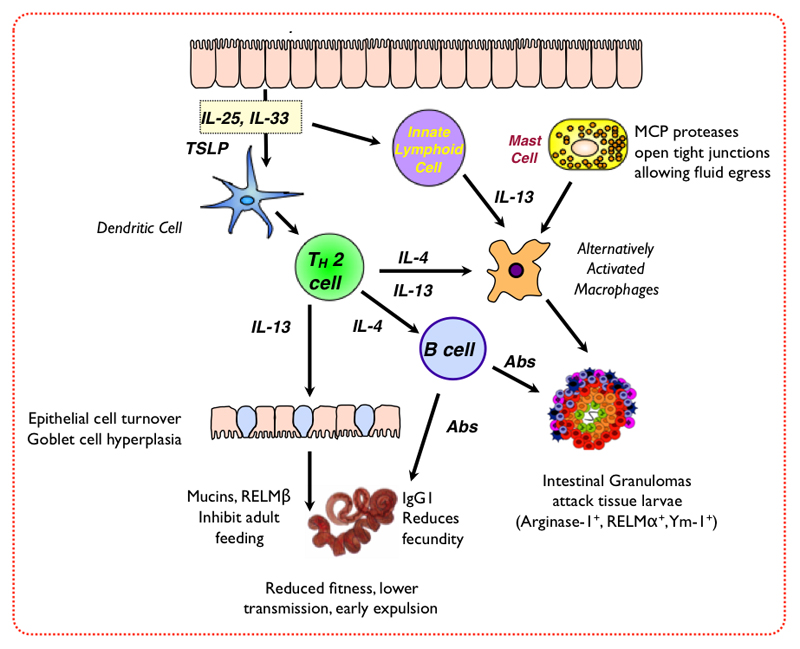

Intestinal granuloma macrophages expressing alternatively activated macrophage products Arginase-1, RELM-α and Ym1, also develop following primary infection of genetically resistant SJL mice (Filbey, K.J. et al., manuscript in preparation), while in more susceptible BALB/c animals granuloma numbers inversely correlate with worm burdens (Reynolds, L. A. et al., unpublished data). In fact, clodronate-mediated depletion of macrophages reduces this granulomatous inflammation and protective immunity in response to both primary and secondary infection (Anthony, et al., 2006 and Filbey, K. J. et al, manuscript in preparation). Even if larvae are not killed within granulomas, however, they may incur immune damage that compromises their subsequent growth and reproduction following emergence into the lumen. Although CD4+ T cells mediate helminth immunity during primary infection, there is also an essential role of antibodies, particularly during recurrent infection. Thus, passive transfer of immune antibodies can reduce worm length and fecundity, even if numbers of live worms are little altered (McCoy, et al., 2008, Liu, et al., 2010). Innate effector cells also participate, as IL-4/-13-stimulated intestinal epithelial cells differentiate into goblet cells, increase mucin production (Hasnain, et al., 2011) and release RELM-β, a natural defence molecule with directly inhibitory effects on adult H. polygurus worms (Herbert, et al., 2009). A summary of these mechanisms is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Pathways of immunity to H. polygyrus.

Immune regulation in vivo

The primary immune response to H. polygyrus infection has a predominant Th2 response phenotype (Wahid, et al., 1994, Mohrs, et al., 2005), but is accompanied by regulatory T cell activation (Metwali, et al., 2006, Finney, et al., 2007, Setiawan, et al., 2007, Rausch, et al., 2008) and fails to achieve parasite expulsion in all but the most genetically-resistant strains (Prowse, et al., 1979). However, susceptible mice are able to mount highly effective immunity if exposed to a short-term (14-day) infection curtailed by curative drug-treatment (Behnke and Wakelin, 1977, Anthony, et al., 2007). As protective mechanisms exist but are not stimulated or deployed during the primary infection, we hypothesize that they are blocked by the same immuno-regulatory and pathways that are responsible for suppression of immune responsiveness to bystander antigens discussed above (see Table 1). Presumably, sufficient priming of the effector T cell response occurs in the drug-cured mice to permit protective immunity to develop rapidly on re-infection, suggesting that antigen-specific memory is stronger within the effector compartment than in the regulatory population. The successful expression of immunity in mice cleared of infection within 14 days also suggests that mature adult parasites are the most effective immunoregulators.

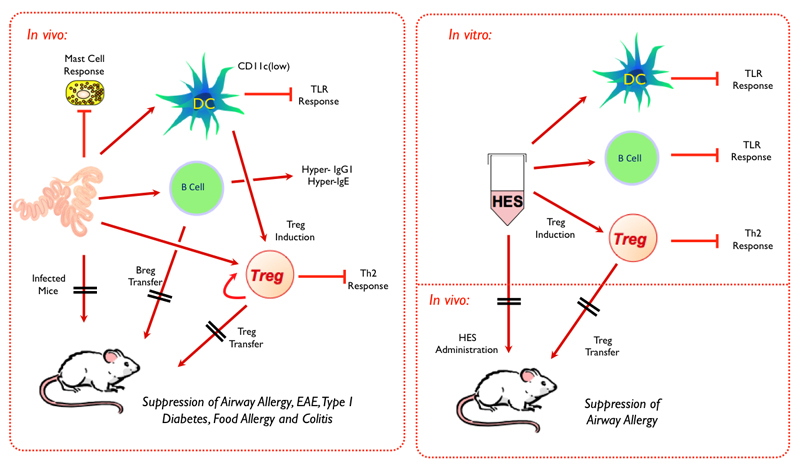

Although H. polygyrus is able to establish a primary infection in all strains of laboratory mice, its subsequent survival varies between mouse strains. Thus, SJL mice are relatively resistant, clearing the infection over a 2-4 week time period, while CBA mice are particularly susceptible; other strains show graded intermediate levels of susceptibility that affect length of infection and egg output (Prowse, et al., 1979, Enriquez, et al., 1988, Behnke, et al., 2006) (Table 2). The BALB/c strain has a degree of resistance, with female mice able to clear a large proportion of the worm load by day 28 (Hurley, et al., 1980), consistent with a general trend for male mice to be more susceptible than females to H. polygyrus (Dobson, 1961, Van Zandt, et al., 1973, Prowse and Mitchell, 1980). Resistance is closely correlated with the intensity and speed of the parasite-specific Th2 response, which may be inhibited or retarded by competing cell types. For example, in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice, the Th2 response is primarily counterbalanced by Th17 and Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, while the most susceptible CBA mice show high levels of CD8+ cell IFNγ production (Filbey, K.J., Granger, J.R. et al, manuscript in preparation). While resistant SJL mice have normal numbers of Foxp3+ Tregs, they do not appear activated by infection (as measured by upregulation of CD103 expression) and a much prompter and stronger Th2 response is mounted. A summary of possible regulatory interactions during infection in mice is presented in Figure 3 A.

Figure 3. Immunoregulatory effects of (A) H. polygyrus and (B) HES.

Tregs in H. polygyrus

Over recent years, a compelling picture has emerged of the expansion and activation of host regulatory cell populations during H. polygyrus infection. For example, in the susceptible C57BL/6 and BALB/c strains of mice there is an activation and expansion of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the mesenteric lymph nodes (Finney, et al., 2007, Rausch, et al., 2008), particularly in the early phase of infection, while in the lamina propria a CD8+ regulatory population has been reported (Metwali, et al., 2006). While Tregs appear to outpace proliferation of effector T cells early in infection, by day 28 the numerical ratio of Foxp3+ Tregs to Foxp3 effectors has returned to normal. However, Tregs at this stage are more suppressive on a per-cell basis (Finney, et al., 2007) and play an important role in chronic infection as inhibition of TGF-β signalling, an important factor in the induction of regulatory T cells, reduces adult worm burden and results in an increase in the Th2 response following H. polygyrus infection (Grainger, et al., 2010). Transfer of Tregs (sorted on surface CD25 expression) from H. polygyrus-infected mice conferred protection from airway allergy to sensitized mice, reproducing the effects of live infection (Wilson, et al., 2005).

The mechanism(s) through which host regulatory cells exert suppression in infected mice remain to be fully established. Significantly, IL-10 does not appear to be a key player, as airway allergy can be suppressed by transfer of IL-10-deficient cells from infected mice (Wilson, et al., 2005); experiments in globally IL-10 deficient mice indicated loss of protection against allergy (Kitagaki, et al., 2006), but in these settings there a major changes in baseline inflammatory levels which complicate interpretation. However, since H. polygyrus can avert colitis in IL-10-deficient mice (Elliott, et al., 2004), it is clear that the parasite's ability to dampen immunopathology is not entirely dependent upon this cytokine. In contrast to any suppressive role, IL-10 may well be acting to promote Th2 immunity, as antigen-specific IL-10 recall responses track the production of the Th2 effector cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13 (Finney, et al., 2007). IL-4 dependent IL-10 may promote Th2 immunity through specific downregulation of Th1 cells, whilst permitting outgrowth of Th2 cells, as has previously been demonstrated to occur in response to N. brasiliensis excretory-secretory (NES) antigens (Balic, et al., 2006).

Another prominent immunoregulatory cytokine is TGF-β (Li, et al., 2006), with particular significance for H. polygyrus. In chronic infection of C57BL/6 mice, plasma TGF-β levels rise threefold over 30 days, but return to baseline within a week of curative drug treatment (Su, et al., 2005). Interestingly, as discussed below, the parasite produces a functional TGF-β mimic, which may further increase the high plasma levels during active infection. Although TGF-β-deficient mice do not survive to adulthood, animals bearing a genetic construct in which T cells alone express a dominant negative TGF-β receptor (TGF-βRIIdn) are viable. While TGF-βRIIdn mice develop colitis like IL-10-/- animals, infection fails to ameliorate pathology, indicating an essential function for TGF-β in parasite immunomodulation (Ince, et al., 2009).

Surprisingly in view of the indicated role for TGF-β, TGF-βRIIdn mice are fully susceptible to H. polygyrus infection (Ince, et al., 2009); while this result could indicate that TGF-β is not required for parasite establishment, an alternative interpretation is that the excessively high Th1 bias of these mice (as evidenced by up to 25-fold higher IFN-γ levels) prevents a protective Th2 response from being engaged. In support of the latter argument, we have found that TGF-βRIIdnxIFNγ-/- double transgenic mice are more resistant to infection (Reynolds, L. et al., preliminary data). In keeping with the hypothesis that host TGF-β favours parasite survival, anti-TGF-β antibody administration to BALB/c mice was reported to reduce (but not eliminate) egg production and adult worm numbers, although the latter effect was not evident until 6 weeks of infection (Doligalska, et al., 2006). Further, while monoclonal antibodies to mammalian TGF-β did not induce a significant loss of worm numbers in the first 4 weeks of infection, a pharmaceutical inhibitor of TGF-β signalling (SB431542) administered from day 28 resulted in a rapid reduction in adult worm numbers accompanied by a sharply increased parasite-specific Th2 response (Grainger, et al., 2010). As the inhibitor blocks both host and parasite TGF-β activities, it was concluded that the parasite ligand is a significant influence on the outcome of infection in vivo.

A central question is whether the Treg expansion occurs within induced (adaptive) or natural (thymic) types (Sakaguchi, et al., 2008). Evidence exists for both in H. polygyrus infection. Pre-existing natural Tregs expressing the marker Helios (Thornton, et al., 2010) are the first to expand following infection, with Helios-negative (ie adaptive) populations only appearing at the end of the first week and remaining a numerical minority of the total Treg compartment (Smith, K.A. et al., manuscript in preparation). However, an increased number of induced Tregs are observed in infected mice challenged with ovalbumin (OVA) following transfer of OVA-specific Foxp3-negative naive T cells (Grainger, et al., 2010). If it is correct that natural Tregs bind self-epitopes (Lio and Hsieh, 2011), only adaptive Tregs are likely to recognise parasite specificities, so an important future issue will be to determine if H. polygyrus antigen-specific Tregs evolve during infection. As Tregs are able to suppress bystander responses (as in the case of cells from helminth-infected mice which suppress allergen responses in uninfected recipients), their TCR specificity does not necessarily correspond to the target of their suppressive effect. Nevertheless, increases in the frequency of Foxp3 expression among CD4+ T cells are seen across wide range of TCR Vβ subsets, alongside an increase in CD103 in these populations, indicating that H. polygyrus-induced Treg expansion is widespread and seems likely to include both parasite and non-parasite specificities (Hewitson, J.P. et al., unpublished data).

Expansion of pro-regulatory DCs in vivo

T cell responses are initiated by antigen-presenting cells, principally dendritic cells (DCs), which have been demonstrated to be powerful and essential stimulators of the Th2 response to helminth infections (MacDonald and Maizels, 2008, Phythian-Adams, et al., 2010). Their potency was first shown in experimental systems in which in vitro differentiated bone marrow-derived DCs, pulsed with helminth products and subsequently adoptively transferred to naïve mice, induce Th2 responses in the recipient animals (MacDonald, et al., 2002, Balic, et al., 2004). The necessity of DCs for Th2 induction has further been established by specific ablation of CD11c+ populations co-expressing the human diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) in a transgenic mouse model (Hochweller, et al., 2008). In this setting, we have shown that depletion of DCs following primary infection with H. polygyrus (as well as Nippostrongylus brasiliensis and Schistosoma mansoni) results in diminished intracellular cytokine Th2 responses as well as ablated antigen-specific Th2 responses to these helminths (Phythian-Adams, et al., 2010). In contrast, depletion of basophils during the acute phase of infection with MAR-1 antibody did not affect the Th2 response (Smith, K.A. et al, manuscript in preparation).

DCs from the lamina propria of H. polygyrus-infected mice have been reported to have poorer responses to TLR ligation and induce weaker Th1 responses in naive T cells (Hang, et al., 2010). In parallel, we investigated whether the activation of Tregs in H. polygyrus infection was dependent on DCs, and if a specialised DC subset could be defined that preferentially induces Tregs in this setting. Conventional (CD11c+) and plasmacytoid (B220+PDCA-1+) DCs were analysed for a suite of surface markers, in particular examining subsets varying in expression of CD8α and CD11c itself. In infected mice we first noted the loss of a MLN-specific CD11c+CD8αintermediate subset (Balic, et al., 2009), which are thought to migrate to the lymph node from the lamina propria of the gut (Anjuère, et al., 2004). Hence, in chronic infection the transport and presentation of antigen from the gut may be compromised. Furthermore, the remaining CD11c+ DCs, purified from MLN by magnetic bead sorting with anti-CD11 antibody, did not induce Foxp3 expression in naive T cells, and are unlikely to underpin the selective induction of Tregs in infection (Balic, et al., 2009).

We then examined a broader range of CD11c-expressing cells, including CD11clow DCs which often escape purification by magnetic bead techniques. A very substantial change was found, again in the infected MLN, in which CD11clow DCs became the major subset; although expressing B220, these were PDCA-1-negative (and hence not plasmacytoid DCs) and they lacked markers of other cell types such as macrophages and granulocytes. When purified by flow sorting, the CD11clow DCs were found to be much more effective at induction of Foxp3 expression than the conventional CD11chigh population (Smith, et al., 2011). In CD11c-DTR mice, in which CD11clow DCs are spared deletion, we also found that while the Th2 effector response was lost in the absence of CD11chigh DCs, the ability to induce de novo Treg differentiation was intact, again arguing that the regulatory DC population is within the CD11clow compartment.

In vivo, the effect of "regulatory DC" expansion may be continued stimulation of Tregs and/or conversion of naive T cells into the regulatory phenotype. However, the consequences may depend on the setting: for example, when H. polygyrus mice are co-infected with Citrobacter rodentium bacteria, colitis is exacerabated, a phenotype that can be reproduced by transfer of DC from helminth infected mice into bacterial-infected animals (Chen, et al., 2006).

Innate Type 2 Populations modulated by H. polygyrus

DCs are not the only innate cell population to show dramatic modulation during H. polygyrus infection. Perhaps the most significant is the alternative activation of macrophages associated with intestinal granulomas and protective immunity, as discussed above (Weng, et al., 2007). Despite being linked to parasite killing, alternatively activated macrophages are also strongly anti-proliferative, suppressing the responses of target cells in vitro (Loke, et al., 2000) and in vivo (Taylor, et al., 2006). As one mechanism of macrophage suppression is local deprivation of amino acids, it is possible that the same pathway blocks both host cell proliferation and parasite growth. Interestingly, alternatively activated macrophages are unaffected by depletion of CD11c+ DCs in DTR mice (Smith, K.A. et al, manuscript in preparation), suggesting that they can differentiate in response to innate IL-4/IL-13 production (Loke, et al., 2007), although their continued expansion requires stimulation by T-cell derived type 2 cytokines (Jenkins, et al., 2011).

There is accordingly great interest in innate sources of type 2 cytokines in helminth infection. In N. brasiliensis, a major population of lineage-negative non-B non-T cells is observed producing IL-5 and IL-13, which is stimulated by IL-25 and IL-33 from epithelial cells (Moro, et al., 2010, Neill, et al., 2010, Price, et al., 2010). Interestingly, it had earlier been reported that T cell-deficient (nude) mice mounted a rapid local IL-3, IL-5 and IL-9 response to H. polygyrus infection (Sveti´c, et al., 1993). However, by day 7 the IL-25-responsive innate lymphoid cell (or 'nuocyte') population is subdued in H. polygyrus (Smith, K.A. et al., unpublished data), and in particular IL-13 is much less prominent than in N. brasiliensis infection in which it is a key player in protective immunity (Urban, et al., 1998). It will be interesting therefore to determine whether H. polygyrus directly suppresses innate type 2 populations, or if the host response to infection selectively prioritises IL-4-producing pathways over those favouring IL-13.

H. polygyrus is also a potent inhibitor of mast cell responses, as the mastocytosis observed in T. spiralis infection is suppressed in mice co-infected with H. polygyrus (Dehlawi, et al., 1987), or even when adult worms are transferred to naive mice immediately before T. spiralis infection (Dehlawi and Wakelin, 1988). Co-infected mice show significantly lower IL-9 (and IL-10) responses compared to those infected with T. spiralis alone (Behnke, et al., 1993). Conversely, Tg54 transgenic mice over-expressing IL-9 generate very high levels of mucosal mast cells and are able to expel a primary H. polygyrus infection in 14-21 days (Hayes, et al., 2004). IL-2Rβ-over-expressing mice with constitutive intestinal mastocytosis are also relatively resistant with suppressed worm fecundity throughout infection (Morimoto and Utsumiya, 2011), although this receptor expression may influence other cell types through association with IL-2Rγ and response to IL-15 (Giri, et al., 1994). Likewise, mast-cell deficient mice (W/Wv, carrying mutations in the c-kit receptor for stem cell factor) harbour more fecund adult worms than wild-type controls (Hashimoto, et al., 2010). However, the recent finding that innate lymphoid cell populations (eg 'nuocytes') express c-kit calls into question whether these mutations only affect the mast cell compartment. Currently then, it is likely but not certain that mast cells can play a role in immune attack against H. polygyrus; in any case the parasite is able to repress the full expression of mast cell-mediated responsiveness.

A further mucosal response to Th2 cytokines is hyperplasia of Paneth cells, located at the base of each villous crypt; in H. polygyrus infection there is a short-lived expansion of Paneth cell numbers which declines following day 8, in contrast to greater and continued hyperplasia in mice infected with other nematodes such as N. brasiliensis and T. spiralis (Kamal, et al., 2002), suggesting the possibility of parasite down-modulation of this cell type. Perhaps surprisingly in view of recent emphasis on the role of basophils in Th2 induction (Perrigoue, et al., 2009), we found that MAR-1 antibody depletion of this cell type did not compromise levels of Th2 cytokines in the intestinal draining lymph nodes, nor other innate type 2 responses such as alternatively activated macrophages following H. polygyrus infection (Smith, K.A. et al, manuscript in preparation). Finally, intestinal goblet cell numbers expand dramatically over the course of infection, and their production of RELM-β is associated with successful elimination of the adult worm (Herbert, et al., 2009). It is interesting however, that while goblet cells switch to production of mucin Muc5ac which promotes expulsion of other nematode species (N. brasiliensis, T. muris and T. spiralis), this switch does not occur in H. polygyrus infection (Hasnain, et al., 2011) indicating either that the parasite fails to trigger a key stimulus, or is also able to interfere with goblet cell function.

B cells as targets and effectors of regulation

B cells are both activated by, and influential in, the course of H. polygyrus infection (Harris and Gause, 2011). Soon after parasite entry, polyclonal B cell stimulation results in a hypergammaglobulinaemia, restricted to IgG1 and IgE (Chapman, et al., 1979). While primary infections cause 2-3-fold rises in serum IgG1 concentrations, following repeated infection IgG1 levels can rise to as high as 20-45 mg/ml compared to an uninfected level of <1 mg/ml (Prowse, et al., 1979, Williams and Behnke, 1983). The induction of bystander specificity, class-switched antibodies was recently demonstrated H. polygyrus infection of mice containing a virus-specific variable immunoglobulin VDJ segment 'knocked in' to the heavy chain locus; in these mice infection generated high titres of virus-specific IgG1 and IgE antibodies (McCoy, et al., 2008). Likewise, ovalbumin (OVA)-specific IgE is boosted in infected mice exposed to OVA by priming and airway challenge (Kitagaki, et al., 2006). The mechanistic basis for this hypergammaglobulinaemia has yet to be investigated, although it requires T cell involvement as IgG1 levels are normal in infected mice in which CD80/86 interactions are blocked (Greenwald, et al., 1997), and significantly abated in IL-21R-deficient mice (King, et al., 2010) reflecting the importance of T follicular helper cell-derived IL-21 in plasma cell differentiation (King and Mohrs, 2009). However, CD28-deficient mice develop normal hypergammaglobulinaemia following infection (Gause, et al., 1997). Over-production of seemingly irrelevant antibodies might be thought to aid parasite survival, but it should be noted that naive mouse serum can exert an anti-fecundity effect in B cell-deficient mice (McCoy, et al., 2008).

Polyclonal B cell activation, and immunoglobulin production, is also accompanied by the emergence of regulatory functions within the B cell population. Following H. polygyrus infection there is an expansion of B cells expressing the low affinity IgE receptor (CD23), and when transferred to uninfected hosts, these B cells can suppress both autoimmune disease (experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis) and airway allergic reactivity (Wilson, et al., 2010). B-cell deficient mice are more susceptible to infection, when judged by egg counts for example, indicating that regulatory B cells are not critical to parasite survival, although they may be required to dampen specific B cell effects such as antibody production in the wild-type setting.

Recently, it has been suggested that B cell cytokine production contributes an essential component to the Th2 response (Wojciechowski, et al., 2009), as shown by chimeric mouse experiments, and that the key B cell products are IL-2 and TNF-α. Consistent with this, B cell deficient mice (µMT or JHD) fail to express protective immunity when challenged following the drug-abbreviated infection regimen that successfully primes wild-type mice (Wojciechowski, et al., 2009, Liu, et al., 2010). However, in JHD mice, both the adaptive Th2 and Foxp3+ Tregs responses, as well as the innate Type 2 development of alternatively activated macrophages in granulomas around encysted H. polygyrus larvae, are comparable to wild-type mice (Liu, et al., 2010). Hence, the extent to which B cells are a determining factor in the response phenotype depends on the model, with a more critical role only operative in the particular context of the chimeric mouse constructs.

Antibody responses in infection

In H. polygyrus infections, several lines of evidence argue for a key role for antibodies in immunity to H. polygyrus, even though expulsion of other gut helminths such as N. brasiliensis is clearly antibody-independent (Liu, et al., 2010). Antibody responses correlate with reduced worm numbers across different mouse strains (Zhong and Dobson, 1996) as well as within mouse strains (Ben-Smith, et al., 1999). Importantly, a causal link has been established by passive transfer experiments. Hyperimmune serum (from multiple rounds of infection) (Williams and Behnke, 1983), and the IgG1 fraction in particular (Pritchard, et al., 1983), could transfer a degree of immunity, with reduced worm survival and stunting of parasites that remained. Importantly, serum transfer was found to be effective only if administered during the encysted stage of infection (Behnke and Parish, 1979), and anti-larval immune effects such as growth retardation that are absent in JHD mice were restored by transfer of immune serum (Liu, et al., 2010). While another study was unable to restore immunity in μMT mice, this employed a more limited regimen of immune serum transfer, perhaps suggesting that antibody-mediated anti-fecundity requires relatively high titres in vivo (Wojciechowski, et al., 2009).

IgG1, despite its reported high potential to trigger inhibitory FcR signalling (Pleass and Behnke, 2009), remains the most likely protetive isotype, as experiments with IgE- (McCoy, et al., 2008) and high-affinity IgE receptor-deficient (Finkelman, et al., 1997) mice argue against a role for IgE in immunity. In addition, µS mice which lack the ability to secrete IgM are fully protected from challenge infection (Wojciechowski, et al., 2009), as are IgA-/- mice (McCoy, et al., 2008). Maternal IgG was also demonstrated to confer protection against H. polygyrus in newborn mice (Harris, et al., 2006).

An important issue that remains to be resolved is the role of antibodies in anti-fecundity immunity which limits or pre-empts egg production without removing the mature parasites. There is clearly a graded level of anti-fecundity immunity as highly susceptible strains (eg CBA) sustain much higher egg counts than those which eventually expel parasites, and we have frequently observed that reduced egg production precedes adult expulsion (Filbey, K.J. et al, manuscript in preparation). In this context, it is interesting to note B cell-deficient (JH-/-) mice do not control egg counts in primary infection unless given naive IgG1 (McCoy, et al., 2008), while the same strain was reported to express full anti-fecundity immunity in secondary infection following drug clearance (Liu, et al., 2010). Since similar (µMT) mice show delayed emergence of secondary adult worms into the lumen (Wojciechowski, et al., 2009) it is possible that only in the setting of a previous exposure, antibody-independent immune reactions in the tissues can sufficiently damage the parasites to heavily compromise their ability to produce eggs.

HES - the secreted proteins of H. polygyrus

The many facets of immune modulation by H. polygyrus are most likely to be mediated by excretory-secretory (ES) products released by live worms in vivo and in vitro (Hewitson, et al., 2009). In the case of H. polygyrus, the older literature has established many intriguing effects of ES materials, albeit collected under different protocols with only preliminary characterization at the molecular level (Monroy, et al., 1989c, Pritchard, et al., 1994, Telford, et al., 1998). As discussed below, modern proteomics have now allowed us to identify at the sequence level all the major components of the adult worm secretome (Hewitson, et al., 2011b). While the established immunomodulatory functions of HES are not unique amongst helminth ES products (for example ES-62 (Harnett and Harnett, 2009)) they are certainly among the broadest suite of reported effects (Figure 3 B), including modulation of DCs (Segura, et al., 2007), the induction of Tregs (Grainger, et al., 2010), and the ability to block airway allergy in vivo (O'Gorman, M.O, McSorley, H.J. et al, manuscript in preparation).

Studies on murine bone marrow-derived DCs have defined a potent inhibitory effect of HES that blocks the normal inflammatory response to TLR ligation by stimuli such as LPS (Segura, et al., 2007), in a manner similar to that reported for the closely related N. brasiliensis (Balic, et al., 2004). HES acts on murine BM-DC s not only to directly suppress a broad range of cytokine responses (most markedly IL-12p70) following TLR ligation (Grainger, J.R, Dayer, B. et al, unpublished data), but also in trans to block the response of co-cultured DCs which have not themselves been exposed to HES (Massacand, et al., 2009). Since the ablation of IL-12 production by DCs replicates the biological effect of TSLP, it is interesting to note that the Th2 bias in H. polygyrus infection occurs in the absence of TSLP (Massacand, et al., 2009) in contrast to reports of Th1 responses in TSLP-/- mice infected with Trichuris muris (Taylor, et al., 2009). HES can similarly inhibit the TLR responsiveness of murine B cells and macrophages, most markedly with respect to IL-6 secretion (Hewitson, J.P. et al, unpublished data).

HES is also able to reproduce in vitro the induction of Foxp3+ Tregs which occurs in vivo following infection. By exposing naive peripheral non-regulatory T cells to a TCR ligand (anti-CD3 or Con A lectin) together with HES, conversion to Foxp3+ Tregs occurs in a very similar manner to that induced by host TGF-β, through the TGF-β signalling pathway: induction of Foxp3 is abolished by an inhibitor of the TGF-β receptor kinase, and is absent in cells which express a dominant negative TGF-βRII (Grainger, et al., 2010). The TGF-β mimic in HES is not inhibited by monoclonal antibodies to mammalian TGF-β, but can be blocked by antisera from chronically-infected mice, and therefore is a parasite rather than a host product. Functionally, Tregs generated in vitro by HES were shown, on transfer to allergic mice, to suppress airway allergy in the same model used for Tregs from in vivo parasite infections.

Under appropriate conditions, TGF-β can also induce functional differentiation of other T cell subsets, including Th9 (in the presence of IL-4) and Th17 (in the presence of IL-1 and IL-6). In keeping with this, HES will drive Th17 commitment in naive T cells co-cultured with IL-6 (Grainger, et al., 2010). Interestingly, it has been suggested that H. polygyrus suppresses IL-9 production in vivo (Behnke, et al., 1993), which would account for the inhibition of mast cell numbers observed in co-infections. We discuss below the stimulation and potential regulatory importance of the Th17 response in this infection.

Molecular Analysis of HES

The remarkable immunomodulatory abilities of HES prompted us to dissect the molecular composition of H. polygyrus, by combining a systematic proteomic analysis of parasite Excretory-Secretory (HES) products, coupled with a deep transcriptomic analysis of parasite mRNAs. The transcriptomic work provides a dataset against which proteomics can be matched, and gives insights into the relative abundance and stage-specificity of individual gene products. Currently, between 200,000 and 450,000 mRNAs from each of 5 life cycle stages (Eggs, infective L3, day 3 L3, day 5 L4 and adult worms) have been sequenced (Harcus, Y., Bridgett, S., Blaxter, M. et al, manuscript in preparation). These sequences have been assembled into a smaller number of 'isotigs' which represent individual mRNA species which may correspond to either a primary gene product, a splice variant, or an allelic form. For the purposes of identifying the HES constituents, a deeper adult transcriptomic set was obtained by combining analyses of total mRNA with a normalised library from which more abundant transcripts are removed. In total, the adult transcriptome now contains ~20,700 candidate isotigs that represent some 17 Mb of unique sequence (available through http://genepool.bio.ed.ac.uk/blast/hpoly.html). In parallel, genomic DNA from H. polygyrus has been sequenced and an assembly of 294 Mb (in 714,000 contigs) can be searched at http://www.nembase.org.

On the basis of the adult transcriptomic dataset, we analysed ~50 spots from 2D SDS-PAGE of HES, and subjected total tryptic digests of HES to tandem mass spectrometry (Hewitson, et al., 2011b). In this manner we identified 374 individual proteins, of which a small number are relatively abundant (Table 3). An important comparison made in our study was with the soluble somatic proteome: most HES proteins were not highly represented in the somatic extract, and conversely, most abundant somatic proteins (including many ribosomal proteins and other products involved in biosynthesis) were not detectable in HES. Further, while most HES proteins corresponded to gene products with predicted signal peptides, these were in a minority in the somatic extract. The identification within HES of multiple proteases and acetylcholinesterases confirms previous biochemical work reporting these enzymes to be secreted by H. polygyrus (Monroy, et al., 1989b, Lawrence and Pritchard, 1993).

Table 3. Prominent protein components of HES.

| Gene family | HES proteins | Extract Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase | 3 | 0 |

| Apyrase | 6 | 0 |

| Aspartyl protease (necepsin) | 5 | 1 |

| Astacin protease family member | 20 | 3 |

| C-type lectin | 3 | 2 |

| Cystatin | 1 | 1 |

| Fatty acid and retinol binding protein | 2 | 3 |

| Galectin | 5 | 2 |

| Lysozyme | 8 | 0 |

| Serine carboxypeptidase | 3 | 0 |

| Serpin | 3 | 0 |

| Venom allergen | 25 | 8 |

| Zinc metalloprotease | 5 | 0 |

| Predominant in Extract | ||

| Proteosome subunit | 0 | 8 |

| Ribosomal proteins | 2 | 54 |

The most remarkable feature of HES, however, is the presence of 25 members of the Venom Allergen-Like (VAL) family, which are homologues of the Ancylostoma secreted protein (ASP) vaccine candidate (Hawdon, et al., 1996) as well as prominent antigens from most other helminth species studied (Murray, et al., 2001, Chalmers, et al., 2008, Cantacessi, et al., 2009). Despite their ubiquity, the function of this gene family remains to be determined, and we are adopting transgenic expression strategies to address this important question. The VAL/ASP proteins are also strongly represented on the surface of the adult parasite, as first indicated by surface labelling studies (Pritchard, et al., 1984b) and confirmed with new monoclonal antibodies (Hewitson, et al., 2011a).

Among the newly identified H. polygyrus genes encoded in the transcriptomic data are those encoding homologues of TGF-β, which are currently under investigation as likely mediators of the TGF-β-like activity of HES (Grainger, et al., 2010, McSorley, et al., 2010), and members of the C-type lectin family as previously described in H. polygyrus (Harcus, et al., 2009) and other nematodes (Loukas and Maizels, 2000). These studies also provide defined antigenic species for antibody assays as described below.

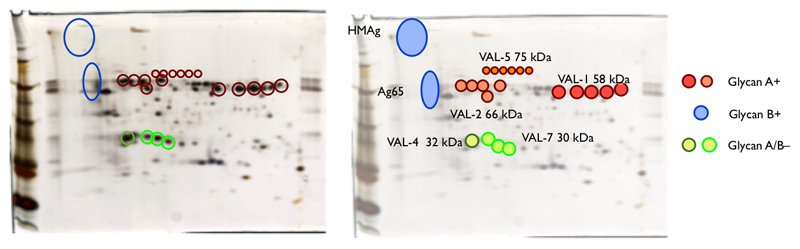

Antibody Targets

The molecular identification of individual HES components has now provided the opportunity to define the immunogenic components of H. polygyrus. Questions of antibody specificity are difficult to judge from the earlier studies, which relied on complex antigen mixtures, and did not extend to the use of monoclonal antibodies. More recently, we have analyzed the serum antibody profile of infected mice, and found that reactivity is predominantly to HES, rather than somatic extract (Hewitson, et al., 2011a). From this study, and by analysing monoclonal antibodies derived from infected mice, we showed that the major antigens in both primary and secondary infection are members of the VAL family, and the epitopes are both glycan and peptide in nature, which we have defined as follows (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Summary of the antigenic profile of HES defined by antibody reactivities.

Glycan A is an immunodominant O-linked epitope carried on VAL-1, -2 and -5, which stimulates an early IgM response that does not class switch. Monoclonal antibodies to glycan A bind to the adult worm surface but do not react strongly with somatic components. In contrast, glycan B is present on diffusely migrating non-protein staining components of 60-70 kDa (Ag65), and of very high mol.wt (Ag-HM). Monoclonal antibodies to the glycan B epitope bind adult somatic tissues rather than the cuticle, and the response class switches to IgG1 and IgA in vivo. HM-65 bears phosphorylcholine (PC), but the glycan B epitope itself is not PC (Hewitson, et al., 2011a).

Class-switched IgG1 antibodies also develop to the polypeptide backbone of VAL proteins, including additional members VAL-4 and VAL-7. While vaccination with HES can induce complete immunity to challenge infection, it was not possible to confer passive protection with monoclonal antibodies against either the glycan epitopes, or VAL-1, -2 and -4 proteins. Thus, it appears that the murine immune response generates nonprotective antibodies, perhaps due to the dominance of a small subset of antigenic epitopes (Hewitson, et al., 2011a). One possibility is that the glycan determinants act as decoy specificities, stimulating the primary immune response to produce only non-protective antibodies.

Another unanswered question is the mechanism of action of protective antibodies: the effect of passive immunisation requires early serum transfer, implying a tissue phase target (compromising the growth or fitness of larval parasites for example), but the ability to reduce adult worm fecundity could also indicate activity against parasites in the lumen. If antibodies are effective in the latter setting, it may then be significant that high levels of intestinal IgG1 are observed in mucosal washings of infected, but not naïve, mice ((Ben-Smith, et al., 1999) and Filbey, K.J. unpublished). It remains to be established whether there is a specific transport mechanism for IgG1 contigent upon infection, or if its release is a physiological consequence of epithelial barrier breakdown, due either to damage from migrating parasites, or the physiological changes in tight junctions as seen in the colon during H. polygyrus infection (Su, et al., 2011).

T cell subset competition

The finding of a TGF-β-like activity in HES raised the important questions of whether in vivo this cytokine combined with IL-6 to generate a Th17 response to H. polygyrus, and if so what the impact of such a response might be. Reports of Th17 induction by helminths remain scarce, with the best examples being those of Schistosoma mansoni in CBA mice that develop intense pathology (Rutitzky, et al., 2008) and in C57BL/6 mice primed with schistosome egg antigen (SEA) in CFA (Rutitzky and Stadecker, 2011). Indeed, in H. polygyrus, there is little detectable Th17 response in the draining MLN, and IL-17 mRNA in the gut itself is diminished following H. polygyrus infection in an IL-4 dependent manner at day 14 (Elliott, et al., 2008). Similarly, the parasite-specific Th17 response to the protozoa Eimeria falciformis is significantly inhibited in mice co-infected with H. polygyrus (Rausch, et al., 2010). We determined however that, in C57BL/6 mice, a transient expansion of Th17 occurs only in the local environment (Peyer's patches and intestinal epithelium), detectable at day 7 of H. polygyrus infection (Grainger, J.R, Hewitson, J.P. et al. manuscript in preparation). Interfering with the Th17 response, through deletion of the IL-23p19 subunit, renders mice more resistant, and leads to development of more intestinal granulomas (Grainger, J.R, Hewitson, J.P. et al. manuscript in preparation). Similarly, IL-6-deficient mice are more resistant to infection, developing stronger Th2 responses and higher numbers of intestinal granulomas (Smith, K.A. et al, manuscript in preparation).

A role for commensal bacteria

The occurrence of a short-lived Th17 response in early infection prompted the suggestion that it is stimulated not by H. polygyrus per se, but by commensal microorganisms that may translocate during the larval tissue invasion. H. polygyrus inhabits the proximal small intestine which contains a small but significant microbial population. We used a range of approaches to test whether commensal bacteria influenced the outcome of helminth infection. First, treatment of mice with certain antibiotic combinations was found to reduce susceptibility to infection measured by egg output and adult worm burdens (Reynolds, L.A., unpublished data). However, long-term antibiotic administration may exert many other physiological changes, and this approach does not define which immunological pathways may be involved.

We therefore reasoned that if commensals modify host reponses to H. polygyrus, they are likely to do so through the established pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Despite TLR9 playing a role in the recognition of commensal gut flora DNA (Hall, et al., 2008), TLR9–/– show little difference in susceptibility following H. polygyrus infection, as was also found in mice with TLR2 deficiency. However, MyD88-deficient animals showed a consistently higher degree of resistance and greater level of granuloma formation (Reynolds, L.A., unpublished data). Hence, we currently postulate that different commensal species may promote or hinder development of immunity to H. polygyrus, but that the negative impact of the microbiota is mediated through MyD88 signalling, possibly through redundant toll-like receptors.

This hypothesis is supported by early studies, which found germ-free mice to be significantly more resistant to H. polygyrus infection than those harboring a conventional microflora (Wescott, 1968). Germ-free mice developed more numerous intestinal granulomas (Chang and Wescott, 1972) although no other immunological corrolates are available. Interestingly, the latter authors also reported that gnotobiotic mice, monocolonised with Lactobacillus bacteria, sustained longer-lasting infections than germ-free animals (Chang and Wescott, 1972), consistent with the notion that these micro-organisms may favour H. polygyrus survival. Moreover, the proportion of Lactobacillus/Lactococcus bacteria increase in the intestine of H. polygyrus-infected mice (Walk, et al., 2010) in a manner that shows a statistically significant positive correlation with worm burden (Reynolds, L.A., unpublished data).

Parallels with human and animal gastrointestinal nematodes

H. polygyrus is a Trichostrongyloid nematode, a member of the same taxonomic subfamily as major ruminant parasites (eg Haemonchus contortus, Teladorsagia circumcincta) that cause extensive pathology in livestock. They are also one step removed from the human hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus), which differ from H. polygyrus in that they are blood feeders. The degree to which H. polygyrus can serve as an authentic model for these veterinary and medical scourges is therefore of central importance.

The close phylogenetic relationship between H. polygyrus and the ruminant Trichostrongylids appears to be upheld at the molecular level. For example, T. circumcincta also secretes a TGFβ-like molecule that induces regulatory T cells (Grainger, et al., 2010). More broadly, proteomic analyses of ES products from these species, as well as from the more divergent hookworms, show many similarities, including the abundance of VAL family members and the presence of other common products such as apyrases, acetylcholinesterases and proteases (Yatsuda, et al., 2003, Mulvenna, et al., 2009, Nisbet, et al., 2010, Hewitson, et al., 2011b). In terms of host immunity, while there is relatively little data on T cell subsets and antibody target specificities in the ruminant parasites, it is notable that as in H. polygyrus, an expansion of Tregs has recently been discovered in T. circumcincta infected sheep (McNeilly,T and Matthews, J., personal communication). In humans, T cells from children infected with geohelminths (hookworms, Ascaris and Trichuris) had depressed in vitro immunoreactivity which was restored by removal of CD4+CD25high Tregs (Wammes, et al., 2010). In addition, the nature of human protective immunity has also been explored in hookworm and found to correlate, as in H. polygyrus, with the level of Th2 responsiveness, with the distinction that in humans a significant role has emerged for the IgE isotype (Pritchard, et al., 1995).

H. polygyrus as a model for anti-nematode vaccines

As a model system, studies on vaccine-induced immunity (rather than immunity following drug-induced clearance of live infection) are surprisingly sparse. Early reports indicating that HES is a poor vaccine stimulator, used Freund's complete adjuvant (Hurley, et al., 1980). In retrospect, this may have compromised Th2 priming, because in our hands HES administered in alum induces complete sterilising immunity (Hewitson, et al., 2011a). Indeed, a separate study reported that alum was the most effective adjuvant to induce immunity to H. polygyrus after immunisation with immunoprecipitated proteins from multiply infected mice (Monroy, et al., 1989a). As with most other helminths, irradiated larval vaccines have been tested (Pleass and Bianco, 1996, Maizels, et al., 1999); interestingly, 25-kRad irradiated larvae effectively induce immunity to challenge, but not if co-administered with non-irradiated parasites: the unaffected organisms are thus able to suppress any protective effect engendered by the attenuated larvae (Behnke, et al., 1983), and support the contention that adult worms are able to negate the development of protective immunity. A further report showed that a 60-kDa adult ES component was able, when given with alum, to induce a degree of immunity manifest by reduced egg production by day 21 (Monroy, et al., 1989d); we consider the antigens tested most likely to represent VAL-1 and are repeating this analysis over a 28-day period.

Conclusion

Helminth parasites are accomplished manipulators of host immunity and H. polygyrus is no exception, being a fascinating and instructive model for parasite immunology at many levels (Behnke, et al., 2009). Most strikingly, the multiple immunomodulatory effects of this organism provide fine detail about the mechanisms of parasite immune evasion, allowing new strategies to be developed to enhance immune protection and achieve elimination of helminth infections. At the same time, the intensifying interest in the effects of some helminth species in counteracting immunopathologies such as allergies and autoimmunity (Wilson and Maizels, 2004, Elliott, et al., 2007) and the recognition of helminths as a rich source of new immunomodulatory molecules (Hewitson, et al., 2009, Johnston, et al., 2009) gives added impetus to the molecular studies of helminth secreted products as described above. Together, these new directions point towards new strategies for vaccination and therapeutic intervention to eliminate nematode parasitism, and to alleviate the diseases of immune hyper-reactivity, in both cases restoring the normal homestasis of the immune system.

References

- Ali NM, Behnke JM. Nematospiroides dubius: factors affecting the primary response to SRBC in infected mice. J Helminthol. 1983;57:343–353. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00011068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali NMH, Behnke JM. Non-specific immunodepression by larval and adult Nematospiroides dubius. Parasitology. 1984;88:153–162. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000054421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JE, Maizels RM. Diversity and dialogue in immunity to helminths. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:375–388. doi: 10.1038/nri2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjuère F, Luci C, Lebens M, Rousseau D, Hervouet C, Milon G, Holmgren J, Ardavin C, Czerkinsky C. In vivo adjuvant-induced mobilization and maturation of gut dendritic cells after oral administration of cholera toxin. J Immunol. 2004;173:5103–5111. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony RM, Rutitzky LI, Urban JF, Jr, Stadecker MJ, Gause WC. Protective immune mechanisms in helminth infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:975–987. doi: 10.1038/nri2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony RM, Urban JF, Jr, Alem F, Hamed HA, Rozo CT, Boucher JL, Van Rooijen N, Gause WC. Memory TH2 cells induce alternatively activated macrophages to mediate protection against nematode parasites. Nat Med. 2006;12:955–960. doi: 10.1038/nm1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balic A, Harcus Y, Holland MJ, Maizels RM. Selective maturation of dendritic cells by Nippostrongylus brasiliensis secreted proteins drives T helper type 2 immune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3047–3059. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balic A, Harcus YM, Taylor MD, Brombacher F, Maizels RM. IL-4R signaling is required to induce IL-10 for the establishment of Th2 dominance. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1421–1431. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balic A, Smith KA, Harcus Y, Maizels RM. Dynamics of CD11c+ dendritic cell subsets in lymph nodes draining the site of intestinal nematode infection. Immunol Lett. 2009;127:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansemir AD, Sukhdeo MVK. The food resource of adult Heligmosomoides polygyrus in the small intestine. J Parasitol. 1994;80:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir ME, Andersen P, Fuss IJ, Shi HN, Nagler-Anderson C. An enteric helminth infection protects against an allergic response to dietary antigen. J Immunol. 2002;169:3284–3292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzone LE, Smith PM, Rutitzky LI, Shainheit MG, Urban JF, Setiawan T, Blum AM, Weinstock JV, Stadecker MJ. Coinfection with the intestinal nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus markedly reduces hepatic egg-induced immunopathology and proinflammatory cytokines in mouse models of severe schistosomiasis. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5164–5172. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00673-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke J, Harris PD. Heligmosomoides bakeri: a new name for an old worm? Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Hannah J, Pritchard DI. Nematospiroides dubius in the mouse: evidence that adult worms depress the expression of homologous immunity. Parasite Immunol. 1983;5:397–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1983.tb00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Keymer AE, Lewis JW. Heligmosomoides polygyrus or Nematospiroides dubius ? Parasitol Today. 1991;7:177–179. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(91)90126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Menge DM, Noyes H. Heligmosomoides bakeri: a model for exploring the biology and genetics of restance to chronic gastrointestinal nematode infections. Parasitology. 2009;136:1565–1580. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009006003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Mugambi JM, Clifford S, Iraqi FA, Baker RL, Gibson JP, Wakelin D. Genetic variation in resistance to repeated infections with Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri, in inbred mouse strains selected for the mouse genome project. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28:85–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2005.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Parish HA. Nematospiroides dubius: arrested development of larvae in immune mice. Exp Parasitol. 1979;47:116–127. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(79)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Robinson M. Genetic control of immunity to Nematospiroides dubius: a 9-day anthelmintic abbreviated immunizing regime which separates weak and strong responder strains of mice. Parasite Immunol. 1985;7:235–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1985.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Wahid FN, Grencis RK, Else KJ, Ben-Smith AW, Goyal PK. Immunological relationships during primary infection with Heligmosomoides polygyrus (Nematospiroides dubius): downregulation of specific cytokine secretion (IL-9 and IL-10) correlates with poor mastocytosis and chronic survival of adult worms. Parasite Immunol. 1993;15:415–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1993.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Wakelin D. Nematospiroides dubius: stimulation of acquired immunity in inbred strains of mice. J Helminthol. 1977;51:167–176. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x0000746x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Wakelin D, Wilson MM. Trichinella spiralis: delayed rejection in mice concurrently infected with Nematospiroides dubius . Exp Parasitol. 1978;46:121–130. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(78)90162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Smith A, Wahid FN, Lammas DA, Behnke JM. The relationship between circulating and intestinal Heligmosomoides polygyrus-specific IgG1 and IgA and resistance to primary infection. Parasite Immunol. 1999;21:383–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1999.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitelle A, Di Lorenzo C, Scales HE, Devaney E, Kennedy MW, Garside P, Lawrence CE. Contrasting effects of acute and chronic gastro-intestinal helminth infections on a heterologous immune response in a transgenic adoptive transfer model. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:765–775. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable J, Harris PD, Lewis JW, Behnke JM. Molecular evidence that Heligmosomoides polygyrus from laboratory mice and wood mice are separate species. Parasitology. 2006;133:111–122. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantacessi C, Campbell BE, Visser A, Geldhof P, Nolan MJ, Nisbet AJ, Matthews JB, Loukas A, Hofmann A, Otranto D, Sternberg PW, et al. A portrait of the "SCP/TAPS" proteins of eukaryotes - Developing a framework for fundamental research and biotechnological outcomes. Biotechnology advances. 2009;27:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaicumpa V, Prowse SJ, Ey PL, Jenkin CR. Induction of immunity in mice to the nematode parasite, Nematospiroides dubius. Austral J Exp Biol Med. 1977;55:393–400. doi: 10.1038/icb.1977.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers IW, McArdle AJ, Coulson RM, Wagner MA, Schmid R, Hirai H, Hoffmann KF. Developmentally regulated expression, alternative splicing and distinct sub-groupings in members of the Schistosoma mansoni venom allergen-like (SmVAL) gene family. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Wescott RB. Infectivity, fecundity, and survival of Nematospiroides dubius in gnotobiotic mice. Exp Parasitol. 1972;32:327–334. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(72)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CB, Knopf PM, Hicks JD, Mitchell GF. IgG1 hypergammaglobulinaemia in chronic parasitic infections in mice: magnitude of the response in mice infected with various parasites. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1979;57:369–387. doi: 10.1038/icb.1979.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-C, Louie S, McCormick BA, Walker WA, Shi HN. Helminth-primed dendritic cells alter the host response to enteric bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2006;176:472–483. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Louie S, McCormick B, Walker WA, Shi HN. Concurrent infection with an intestinal helminth parasite impairs host resistance to enteric Citrobacter rodentium and enhances Citrobacter-induced colitis in mice. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5468–5481. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5468-5481.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowaniec W, Wescott RB, Congdon LL. Interaction of Nematospiroides dubius and influenza virus in mice. Exp Parasitol. 1972;32:33–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(72)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell DA, Wescott RB. Prolongation of egg production of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis in mice concurrently infected with Nematospiroides dubius . J Parasitol. 1973;59:216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cywinska A, Czuminska K, Schollenberger A. Granulomatous inflammation during Heligmosomoides polygyrus primary infections in FVB mice. J Helminthol. 2004;78:17–24. doi: 10.1079/joh2003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlawi MS, Wakelin D. Suppression of mucosal mastocytosis by Nematospiroides dubius results from an adult worm-mediated effect upon host lymphocytes. Parasite Immunol. 1988;10:85–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1988.tb00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlawi MS, Wakelin D, Behnke JM. Suppression of mucosal mastocytosis by infection with the intestinal nematode Nematospiroides dubius. Parasite Immunol. 1987;9:187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1987.tb00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson C. Certain aspects of the host-parasite relationship of Nematospiroides dubius (Baylis). I. Resistance of male and female mice to experimental infections. Parasitology. 1961;51:173–179. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000068578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doligalska M, Rzepecka J, Drela N, Donskow K, Gerwel-Wronka M. The role of TGF-β in mice infected with Heligmosomoides polygyrus. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28:387–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druilhe P, Sauzet JP, Sylla K, Roussilhon C. Worms can alter T cell responses and induce regulatory T cells to experimental malaria vaccines. Vaccine. 2006;24:4902–4904. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekkens MJ, Liu Z, Liu Q, Foster A, Whitmire J, Pesce J, Sharpe AH, Urban JF, Gause WC. Memory Th2 effector cells can develop in the absence of B7-1/B7-2, CD28 interactions, and effector Th cells after priming with an intestinal nematode parasite. J Immunol. 2002;168:6344–6351. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekkens MJ, Liu Z, Liu Q, Whitmire J, Xiao S, Foster A, Pesce J, VanNoy J, Sharpe AH, Urban JF, Gause WC. The role of OX40 ligand interactions in the development of the Th2 response to the gastrointestinal nematode parasite Heligmosomoides polygyrus. J Immunol. 2003;170:384–393. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DE, Metwali A, Leung J, Setiawan T, Blum AM, Ince MN, Bazzone LE, Stadecker MJ, Urban JF, Jr, Weinstock JV. Colonization with Heligmosomoides polygyrus suppresses mucosal IL-17 production. J Immunol. 2008;181:2414–2419. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DE, Setiawan T, Metwali A, Blum A, Urban JF, Jr, Weinstock JV. Heligmosomoides polygyrus inhibits established colitis in IL-10-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2690–2698. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DE, Summers RW, Weinstock JV. Helminths as governors of immune-mediated inflammation. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:457–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez FJ, Zidian JL, Cypess RH. Nematospiroides dubius: genetic control of immunity to infections of mice. Exp Parasitol. 1988;67:12–19. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(88)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelman FD, Shea-Donohue T, Goldhill J, Sullivan CA, Morris SC, Madden KB, Gause WC, Urban JF., Jr Cytokine regulation of host defense against parasitic gastrointestinal nematodes: lessons from studies with rodent models. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:505–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney CAM, Taylor MD, Wilson MS, Maizels RM. Expansion and activation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in Heligmosomoides polygyrus infection. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1874–1886. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JG, Beck P, Dangler CA, Whary MT, Wang TC, Shi HN, Nagler-Anderson C. Concurrent enteric helminth infection modulates inflammation and gastric immune responses and reduces Helicobacter-induced gastric atrophy. Nat Med. 2000;6:536–542. doi: 10.1038/75015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich A, Marsland BJ, Sonderegger I, Kurrer M, Hodge MR, Harris NL, Kopf M. IL-21 receptor signaling is integral to the development of Th2 effector responses in vivo. Blood. 2007;109:2023–2031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gause WC, Chen SJ, Greenwald RJ, Halvorson MJ, Lu P, Zhou XD, Morris SC, Lee KP, June CH, Finkelman FD, Urban JF, et al. CD28 dependence of T cell differentiation to IL-4 production varies with the particular type 2 immune response. J Immunol. 1997;158:4082–4087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri JG, Ahdieh M, Eisenman J, Shanebeck K, Grabstein K, Kumaki S, Namen A, Park LS, Cosman D, Anderson D. Utilization of the beta and gamma chains of the IL-2 receptor by the novel cytokine IL-15. EMBO J. 1994;13:2822–2830. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger JR, Smith KA, Hewitson JP, McSorley HJ, Harcus Y, Filbey KJ, Finney CAM, Greenwood EJD, Knox DP, Wilson MS, Belkaid Y, et al. Helminth secretions induce de novo T cell Foxp3 expression and regulatory function through the TGF-β pathway. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2331–2341. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald RJ, Lu P, Halvorson MJ, Zhou X, Chen S, Madden KB, Perrin PJ, Morris SC, Finkelman FD, Peach R, Linsley PS, et al. Effects of blocking B7-1 and B7-2 interactions during a type 2 in vivo immune response. J Immunol. 1997;158:4088–4096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald RJ, Urban JF, Ekkens MJ, Chen S, Nguyen D, Fang H, Finkelman FD, Sharpe AH, Gause WC. B7-2 is required for the progression but not the initiation of the type 2 immune response to a gastrointestinal nematode parasite. J Immunol. 1999;162:4133–4139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JA, Bouladoux N, Sun CM, Wohlfert EA, Blank RB, Zhu Q, Grigg ME, Berzofsky JA, Belkaid Y. Commensal DNA limits regulatory T cell conversion and is a natural adjuvant of intestinal immune responses. Immunity. 2008;29:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hang L, Setiawan T, Blum AM, Urban J, Stoyanoff K, Arihiro S, Reinecker HC, Weinstock JV. Heligmosomoides polygyrus infection can inhibit colitis through direct interaction with innate immunity. J Immunol. 2010;185:3184–3189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harcus Y, Nicoll G, Murray J, Filbey K, Gomez-Escobar N, Maizels RM. C-type lectins from the nematode parasites Heligmosomoides polygyrus and Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Parasitol Int. 2009;58:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnett W, Harnett MM. Immunomodulatory activity and therapeutic potential of the filarial nematode secreted product, ES-62. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;666:88–94. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1601-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris N, Gause WC. To B or not to B: B cells and the Th2-type response to helminths. Trends Parasitol. 2011;32:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris NL, Spoerri I, Schopfer JF, Nembrini C, Merky P, Massacand J, Urban JF, Jr, Lamarre A, Burki K, Odermatt B, Zinkernagel RM, et al. Mechanisms of neonatal mucosal antibody protection. J Immunol. 2006;177:6256–6262. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Uchikawa R, Tegoshi T, Takeda K, Yamada M, Arizono N. Immunity-mediated regulation of fecundity in the nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus--the potential role of mast cells. Parasitology. 2010;137:881–887. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009991673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasnain SZ, Evans CM, Roy M, Gallagher AL, Kindrachuk KN, Barron L, Dickey BF, Wilson MS, Wynn TA, Grencis RK, Thornton DJ. Muc5ac: a critical component mediating the rejection of enteric nematodes. J Exp Med. 2011;208:893–900. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawdon JM, Jones BF, Hoffman DR, Hotez PJ. Cloning and characterization of Ancylostoma-secreted protein. A novel protein associated with the transition to parasitism by infective hookworm larvae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6672–6678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes KS, Bancroft AJ, Grencis RK. Immune-mediated regulation of chronic intestinal nematode infection. Immunol Rev. 2004;201:75–88. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmby H. Gastrointestinal nematode infection exacerbates malaria-induced liver pathology. J Immunol. 2009;182:5663–5671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert DR, Yang J-Q, Hogan SP, Groschwitz K, Khodoun MV, Munitz A, Orekov T, Perkins C, Wang Q, Brombacher F, Urban JF, Jr, et al. Intestinal epithelial cell secretion of RELM-β protects against gastrointestinal worm infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2947–2957. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson JP, Filbey KJ, Grainger JR, Dowle AA, Pearson M, Murray J, Harcus Y, Maizels RM. Heligmosomoides polygyrus elicits a dominant nonprotective antibody response directed at restricted glycan and peptide epitopes. 2011a doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004140. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson JP, Grainger JR, Maizels RM. Helminth immunoregulation: the role of parasite secreted proteins in modulating host immunity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;167:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson JP, Harcus Y, Murray J, van Agtmaal M, Filbey KJ, Grainger JR, Bridgett S, Blaxter ML, Ashton PD, Ashford D, Curwen RS, et al. Proteomic analysis of secretory products from the model gastrointestinal nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus reveals dominance of Venom Allergen-Like (VAL) proteins. Journal of Proteomics. 2011b doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.06.002. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochweller K, Striegler J, Hammerling GJ, Garbi N. A novel CD11c.DTR transgenic mouse for depletion of dendritic cells reveals their requirement for homeostatic proliferation of natural killer cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2776–2783. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JC, Day KP, Mitchell GF. Accelerated rejection of Nematospiroides dubius intestinal worms in mice sensitized with adult worms. Austral J Exp Biol Med. 1980;58:231–240. doi: 10.1038/icb.1980.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]