Abstract

International calls and frameworks for policies on ageing in sub-Saharan African countries, encapsulated in the UN Madrid Plan of Action on Ageing (2002) and the African Union Policy Framework and Plan of Action on Ageing (2003), have resulted in little concrete policy action. The lack of progress calls for critical reflection on the status of policy debates and arguments on ageing in the sub-region. In a context of acute development challenges and resource constraints, the paper links the impasse in policy action to a fundamental lack of clarity about how rationales and approaches for policy on ageing relate to core national development agendas. It then explicates four steps required to elucidate these connections, namely: (a) A full appreciation of key aspects of mainstream development agendas; (b) identification of ambiguities in calls for policy on ageing; (c) pinpointing of key perspectives, arguments and queries for redressing the ambiguities; and (d) addressing ensuing information needs. We argue that advocacy and research on ageing in sub-Saharan Africa need to consider the framework proposed in the paper urgently, in order to advance policy and debate on ageing in the region.

Keywords: Sub-Saharan Africa, Policy, Development, Poverty, Research

Introduction

The ageing of populations in sub-Saharan Africa, as in other developing world regions, is seen widely as marking a demographic triumph. If responded to appropriately, ageing population structures offer enormous potential for societies' advancement. To this end, numerous calls have been made internationally and Africa wide over the past decade, urging national governments to consider issues of ageing and older persons as part of broader plans and processes for social and economic development. However, little concrete action has ensued, suggesting that arguments underpinning the calls have been largely passed over. Rather than simply reassert such advocacy calls, we take a step back at this juncture, to reflect on: (a) How effective or appropriate the arguments may be, given the reality of current development policy contexts and agendas in most sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries; and (b) what approaches to link ageing to development agendas in SSA may be more constructive. We undertake such reflection in two parts: In ‘Context and Challenges’, we examine the context of ageing in the sub-region, and the current status and remaining challenges for the formation of policy on ageing. In ‘Steps and Approaches’ we explore and propose various steps and conceptual approaches for advocacy and research to consider, in order to redress the non-inclusion of ageing and older persons in the sub-regional development endeavour. In putting forward these ideas we seek to stimulate, and offer a basis for, subsequent debate, reflection and analysis.

Context and Challenges

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is the poorest and least developed sub-region in the world. All 22 of the world's countries with “low human development” (UNDP 2008) and two-thirds of its low income economies (World Bank classification) are in SSA. Of 42 major SSA countries, only six are lower middle income and only four are upper middle income economies (World Bank 2008a). Among major social ills that variously beset SSA nations are immense challenges of rural stagnation, urban slums (62% of the urban population live in slums)1, the HIV/AIDS crisis and armed conflict.2 The latter two crises affect SSA more gravely than any other world region and, in the worst affected countries, exacerbate the problems of poverty (see IFAD 2007; Luckham et al. 2001; Porteous 2005;UN 2007a;UNAIDS/WHO 2007; UN Habitat 2008). The scale and depth of the challenges in the sub-region are represented in a range of demographic and development indicators shown in Box 1.

Box 1: Demographic and development indicators in SSA.

41.1% of the population live in extreme poverty (on less than $1 a day). While this marks a decline from 45.9 % in 1999, the absolute number of people living under this poverty line remains unchanged at around 300 million. Proposed revisions to the extreme poverty line to $1.25 per day (based on new estimates of costs of living in developing countries) suggest that the number of poor individuals in SSA may even have risen. Recent years have seen widening inequalities, with the share of consumption by the poor falling between 1990 and 2004; UN 2007a.

Life expectancy at birth in SSA is only 50 years – the same as it was 20 years ago and the lowest in the world (69 years in Asia and 73.3 years in Latin America).

A third of the region's population is undernourished.

At least a quarter of children born today in all SSA countries (69% in Botswana) will not survive to age 40.

Less than half of births are attended by skilled personnel (only 6% in Ethiopia), leading to the world's highest maternal mortality rates.

One in ten babies dies before the age of one year and more than two in ten will die before the age of five years.

No country achieves full primary education enrolment. In several countries, less than 50% of children are enrolled in primary school. In many countries, only a few entering Grade 1 complete full primary education.

SSA is home to an estimated 22 million adults and children infected with HIV/AIDS – a third of the world total. Deaths from AIDS continue to rise in SSA. In 2007, 1.5 million adult and child deaths were due to the disease. While declines in HIV prevalence are now observed in some countries, prevalence is rising in others. Overall, the positive trends are neither strong nor widespread enough to diminish the epidemics' overall impact in the sub-region.

11.6 million African children living today are estimated to have lost one or both parents to AIDS.

Sources: UN 2007, 2008; UNAIDS 2008; UNAIDS/WHO 2007; UNDP 2008; UNPD 2008; World Bank 2008b.

In addition to being the world's poorest sub-region, SSA is also the youngest: 64% of the population are younger than 25 years (compared to 46% and 48% for Asia and Latin America, respectively). Only 4.8% of the population are age 60 years or older. Due to persisting high fertility (currently 5.13 children per woman) and high mortality rates, the population age structure will remain relatively unchanged until 2025 and only shift gradually thereafter (UNPD 2008).

Despite the youthfulness of the sub-continent, international concern with the challenges of ageing in African populations has been growing. The debate has been driven largely by a number of dedicated NGOs (e.g. HelpAge International) and UN agencies (e.g. UNFPA and WHO), and a small corps of international and African researchers. An international awareness of issues of ageing in the sub-region dates back 25 years, to the first UN World Assembly on Ageing (WAAI), held in Vienna in 1982, which effectively launched a discourse on ageing in the developing world (Apt 2005;UN 1982). However, at the time, the challenges of ageing in African countries were neither interpreted appropriately in the Vienna Plan of Action, nor responded to effectively by signatory governments. More recently, the debate on ageing in SSA has intensified again, particularly since the Second World Assembly on Ageing (WAA2), held in Madrid in 2002, which focused specifically on issues of ageing in the developing world (UN 2002).

Key Policy Challenges of Population Ageing in SSA

At the heart of the debate on ageing in sub-Saharan Africa lie two coupled concerns:

First, the implications of demographic projections for the sub-region.3 The proportion of persons age 60 years and over4 in national populations will remain lower than in other world regions—rising from 4.8% at present to only 8.8% by 2050, compared to projected rises from about 10% to 24% in Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean. However, the absolute number of older persons in SSA is projected to rise dramatically over the same period: from 37 million to 155 million—a more rapid increase than in any other world region and for any other age group (UNPD 2008).5 Contrary to misconceptions moreover, older people in SSA will on average live many years beyond age 60. Indeed, life expectancy at age 60 in SSA, currently 15 years for men and 17 years for women, does not differ markedly from that in other world regions (UNPD 2006).

Second, a concern about a specific vulnerability of older persons to detrimental health, economic and social outcomes as a result of three interacting influences:

A diminishing capacity to engage in sufficiently paid productive work and/or self-care, due to physical, mental and social attributes (e.g. very low literacy levels, or age-related chronic disease) associated with chronological ageing in the SSA context and a lack of employment and income generating opportunities.

- Effects of rapid socio-cultural change, economic stress, rural to urban migration of the young, and acute crises, such as the HIV/AIDS epidemics, armed conflict and other emergencies, which alone, or in combination, place:

- increasing strain on family-based support systems that customarily provided protection for older people unable to sustain themselves. Symptoms of the strain include apparent destitution, begging and “abandonment” of older persons in cities; as well as isolation and hardship among those left behind in rural areas (e.g. Aboderin 2006; Apt 1997; Mba 2004).

- new support burdens on older people, particularly caregiving to younger kin affected or orphaned by HIV/AIDS, or maintenance of kin who are unemployed or otherwise unable to earn a livelihood. The additional support burdens may affect older persons' material, physical and emotional well-being negatively (see Ferreira 2006a).

A lack of social service provision for older people in most SSA countries. Existing social services, health care in particular, largely do not cater explicitly for the needs of older persons (Aboderin 2008a; McIntyre 2004; WHO 2006), and only a handful of countries operate a formal old age social security system (Botswana, Lesotho, Mauritius, Namibia, Senegal and South Africa). A poignant example of a lack of social provision is the widespread exclusion of older persons from humanitarian responses in emergency situations, such as Darfur (Bramucci and Erb 2007).

Taken together, the concerns point to what is widely viewed as a major challenge for policy on ageing in SSA: namely, to ensure the security and well-being of a rapidly increasing number of older people in the coming decades. This challenge differs somewhat from principal ageing-related concerns in industrialised and rapidly maturing Asian societies, which focuse on implications of changing (i.e. ageing) population age structures for workforce productivity, sustainability of social security systems and economic growth (Aboderin 2007; Börsch-Supan 2001; Harper 2006; Marshall et al. 2001; UNPD 2007).

The Policy Agenda on Ageing in SSA: Frameworks and Arguments

Two key recent international instruments are available to guide African governments in designing and implementing comprehensive strategies on older persons: (a) The UN Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (MIPAA) which emanated from WAA2, and (b) the African Union (AU) Policy Framework and Plan of Action on Ageing (AU Plan), adopted in 2003 (AU/HAI 2003; UN 2002). The plans, to which all African member states are signatory, are largely comparable. They urge signatory countries to implement relevant recommendations in them, and call on the governments to develop policies across social and other sectors. A principal goal of such policies, as both plans note, is to enhance the quality of life of present and future cohorts of older citizens. As a central approach both the MIPAA and the AU Plan assert a need to “mainstream” policies on ageing within core national development plans. Such mainstreaming is intended to effect a shift away from targeting older persons as a separate, marginalised group, towards an integration of the concerns of older persons in policies across all sectors (UN 2003a,b).

Two major arguments underpin the plans' and subsequent advocacy calls for such policy on ageing. First, that governments have an obligation, under major international covenants6, to realise the fundamental rights of older people who are among the most vulnerable population groups—if not the most vulnerable—in SSA. Second, that governments must acknowledge, encourage and build on the valuable contributions that older persons make to their families and communities (the MIPAA specifically mentions “financial support and the care and education of grandchildren and other kin” (paragraph 34))—and thus to development in general.

National Policy Action on Ageing: Situation and Progress

The MIPAA and the AU Plan, together with ensuing NGO and UN advocacy work, have clearly heightened an awareness of issues of ageing among national governments and have prompted a readiness, at least rhetorically, to develop national policy responses. Thus, in 2005, the government of 13 of 42 SSA countries regarded population ageing as a “major concern,” while another 22 viewed it as a “minor concern” (UNPD 2005). Moreover, 16 SSA countries already have formulated—or are in the process of formulating—a national policy framework on older persons. However, only one country (South Africa) has comprehensive legislation on older persons, and only nine countries (Botswana, Ghana, Lesotho, Mauritius, Namibia, Senegal, Seychelles, South Africa and Zambia) have implemented concrete, national-level strategies targeted at older people (Aboderin 2008a; Nhongo 2006, 2008). The crucial question of what features have driven policy action in these countries, compared to other SSA nations, has not been illuminated. However, one may speculate on at least two possible driving factors. First, most of the above countries (with the exception of Ghana, Senegal and Zambia) are among the ten middle income economies in SSA, suggesting that larger national wealth may reduce impediments to policy action. Second, in the low income nations Ghana and Senegal one can discern effects of personal initiatives by national leaders7, or strong advocacy by high profile nationals.

The overall dearth of policy action in SSA, 7 years after member states committed themselves to implementing recommendations in MIPAA and the AU Plan, is conspicuous, and has been underscored by the UN's recent MIPAA review and appraisal process (UN/DESA 2008; UNECA 2007)8. Regrettably, the review failed to shed light on the precise nature and extent of ageing policy across SSA countries. What is nonetheless evident is that the policy steps that have been taken have been narrow. In Botswana, Lesotho, Mauritius, Namibia, Senegal, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia, efforts have concentrated on the expansion or introduction of a non-contributory social pension programme. In addition, some of these countries, together with Ghana, offer free or discounted health care as another form of social protection to older persons. The predominant focus on pensions follows successful NGO advocacy in recent years, which has foregrounded arguments that payment of regular cash transfers to vulnerable older persons (a) can help to reduce their poverty and thus meet some of their fundamental human rights; and (b) has significant redistributive effects, as beneficiaries often share their pension income with younger generation kin—in particular, children and grandchildren,9 thus contributing to a reduction of poverty in households, families and communities broadly (HAI 2004, 2007). Yet, both MIPAA and the AU Plan call for multifaceted, cross-sectoral strategies to enhance older persons' situation holistically, and policy action is thus needed that goes beyond mere steps to expand social protection.

Reasons for the Policy Impasse

Broad reasons for the general lack of comprehensive policy formation and/or policy action on ageing in most SSA countries include (a) persisting assumptions that families continue to care for elders adequately; (b) an insufficient awareness of, or interest in policy needs of older people; and/or (c) a focus on other priorities for “development” spending, with older persons largely excluded from development agendas (Aboderin 2008a; Aboderin and Gachuhi 2007; Asagba 2005). What these reasons suggest essentially is that policy makers—despite formal expression of commitment to, and guidance from, international frameworks—ultimately remain:

insufficiently persuaded that the realisation of policies for older people will concur with the pursuit of core national development goals and/or

insufficiently clear which policies to pursue as a priority and/or through which approaches (see also Aboderin and Gachuhi 2007).

Challenges for Research and Advocacy on Ageing in SSA

The present deficits and apparent obstacles to policy action pose a critical challenge for research and advocacy on ageing in SSA; namely to explicate clearly the rationales and required approaches for policy on ageing as they relate to mainstream development endeavours in the region. Clarification is needed specifically (a) on where, why and how addressing issues of ageing and older persons could concur with core development plans, but also (b) vice versa, on where and how present mainstream agendas in fact correspond with key objectives of the ageing agenda. In the remainder of this paper, we propose a framework of four successive steps to address this challenge.

Steps and Approaches

Step 1: Appreciating Key Aspects of Mainstream Development Agendas

A first vital step is to fully appreciate the key aspects of core SSA development agendas that policy initiatives on ageing need to take into account.We discern three such aspects.

Resource Constraints

First are severe constraints on resources available to finance development and social efforts in SSA. The constraints reflect, among others, unfair terms of global trade and persistent shortfalls in North/South development aid (that may worsen in the present global financial crisis), and oblige governments to set stark priorities among development needs.

Poverty Reduction Strategies

Second are national Poverty Reduction Strategies (PRS), which in most SSA countries now encapsulate governments' central development and budgeting plans. Moreover, PRS increasingly form a basis for the co-ordination of major international development assistance—upon which African states are heavily and increasingly reliant (ADB 2006; Deacon 2007). As such, the strategies reflect the international community's dominant agenda—including underlying neo-liberal perspectives—on development in Africa (IMF 2008;UNFPA 2005). This agenda took centre stage in 2005, the proclaimed “year for Africa,”, when unprecedented levels of dedicated international policy attention were reached, specifically at the Gleneagles G8 summit. More recently, the agenda was reaffirmed at the G8 summits in Heiligendamm (2007) and Toyako (2008), amid strident criticism of non-delivery on commitments. The principal goals of PRS are to reduce poverty and, specifically, to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and their associated specific targets by 2015.10 Thus far, most SSA countries are unlikely to achieve any of the goals. In some cases there has been no progress at all or even a deterioration of the situation (UN 2007a,b, 2008). To address this impasse, PRS and major international frameworks prioritise three areas for development policy action:

Development of infrastructure, reform of public governance institutions, enhancement of the investment climate, and establishment of efficient markets so as to promote private enterprise, employment opportunities and economic growth (e.g. NNPC 2004).

- Direct social sector investment in the MDG areas of primary education, maternal and child health, HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases; and, for the longer term, measures to address unemployment and lack of education or training of youth—i.e. those aged 15-35 years. An aim is to enable the young to become “productive workers, family heads, citizens and community leaders” (AU 2006a; NNPC 2004; World Bank 2006). The social sector focus on younger age-groups is intended to alleviate their deprivation and suffering, but also, crucially, to develop human capital, in order to raise societies' productivity and, ultimately, economic growth. Indeed, investment in (future) worker capacity is seen as the key to achieving lasting economic and social development in SSA in coming decades (AU 2006a; Schäfer 2006;UN 2005; UNECA 2006):

- “Political stability, social solidification, and economic prosperity [in Africa] lie in harnessing the capacities of the youth (UNECA 2006).”

This view rests squarely on assumptions about a greater productivity and dynamism of the young compared to older age groups (Barrientos 2002; UNECA 2006), and on considerations of broader demographic dynamics. African governments are urged to invest in their large young populations, in order to harness the first demographic dividend for accelerating economic growth from about 2020 onwards—as fertility begins to fall and before the older population increases significantly, and where there is a surplus share of the population in the “productive” ages (World Bank 2006)11. To this end, the recently adopted African Union Youth Charter (2006)12 obliges member states to enact and implement coherent strategies to improve the social and economic situation of youth within national development frameworks13 (AU 2006a). Significantly, and in contrast to the AU Plan on Ageing, the AU Youth Charter is a political and legal document, which, once ratified by at least 15 member states, will bind signatory governments to act. Seven countries have thus far ratified the document, with more expected to do so before the end of 2008, the declared “Year of the African Youth” (AU 2008).

3. In addition to the two primary priorities above, PRS explicitly recognise a need for measures, especially in areas of poverty and health, to safeguard the welfare of the poorest and most vulnerable groups in society. The importance of such social protection measures is increasingly emphasised moreover by some major donor countries—such as the UK (CfA 2005; DFID 2006; HAI 2007). Yet, there is little agreement on who the main vulnerable target groups are and what criteria should be used to assess their vulnerability. PRS and other frameworks typically mention a range of (often overlapping) groups, which include persons of all ages, namely, “the unemployed, children, young people, families, people with disabilities, HIV/AIDS affected households, older people and women” (Aboderin and Gachuhi 2007;HAI 2007).

Promotion of African Cultural Values

In tandem with a focus on PRS has been an intensification of a quest for “home-grown” development solutions, as part of a pursuit of an African “rebirth,” or Renaissance. The quest is encapsulated in the African Union's Horizon Strategy 2004–2007 and is fuelled by a longstanding scepticism regarding the benefit or appropriateness of western development models for Africa (AU 2004a,b,c). On one level, African critiques have highlighted the adverse impacts and clear failure of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), as “prescribed” by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) and adopted by most SSA countries during the 1980s and 1990s, to foster economic growth and social development in the sub-region14 (AU 2004a; Soludo and Mkandawire 1999). On a more fundamental level, critiques have exposed modernisation theory inspired thinking15, which “consciously or unconsciously and in different measure” continues to underpin international agendas for development in Africa. Such thinking essentially views development as a unilinear process and, at its crudest, considers “how African countries could… be made to become more like Europe and the United States” (Olukoshi and Nyamnjoh 2005).

In the pursuit of home-grown development, African states have asserted a central need to promote and “infrastructure” African cultural values, as the “bedrock” of such development (AU 2004a; OAU 1999).16 They have moreover emphasised the particular import of advancing traditional values among the young, given that “the continuous cultural development of Africa rests with its youth” (AU 2006a). In this context, AU frameworks specifically mention a need to instil customary values of family and intergenerational filial support in the young. Thus, the African Youth Charter asserts the responsibility of youth to “have full respect for parents and elders and assist them anytime in cases of need in the context of positive African values” (p. 19). This assertion directly echoes recommendations in the AU Plan, which call for the introduction of legislation that makes it “an offence for family members… to abuse older persons”; requires “adult children to provide support for their parents” (p. 8); and builds on “traditional values and norms regarding family values and the care of older persons” (p. 16).

Step 2: Identifying Ambiguities in Calls for Policy on Ageing

Appreciation of the above features of mainstream development efforts in SSA provides a basis for a second step needed to clarify their connections with ageing agendas: this step is to recognise, and critically assess, ambiguities in present calls for policy on ageing. The calls, as noted earlier, comprise appeals to governments to (a) recognise older people's vulnerability and realise their fundamental rights; (b) acknowledge and support their contributions, especially to family and community and (c) to mainstream measures on ageing across core sectoral policies. Espousing a notion of positive ageing and drawing on international human rights covenants, the case for policies on older persons is outwardly powerful. Yet, as we have seen, advocacy arguments appear to be easily passed over. Indeed, closer inspection reveals key limitations in their ability to sufficiently clarify rationales and approaches for policy on ageing in the context of mainstream development agendas. Four areas of ambiguity in particular emerge.

Ambiguities over cohorts and time horizons. Policy frameworks assert a need to ensure the well-being of the expanding older population in the coming decades. In practice, however, advocacy calls focus almost exclusively on present cohorts of older persons. In addition, policy frameworks assume implicitly that future cohorts will suffer the same vulnerability as those today. However, a likely expectation among policy makers is that present youth and MDG-related investments in the young will avert such vulnerability in their old age.

Ambiguities over rights and priorities of age groups. Both old and young citizens already do, or have the potential to contribute to development. Both are recognised as vulnerable and as having fundamental economic and social rights. But are rights something that must be provided actively, or is it enough to not withhold them? And, given resource constraints, whose needs and rights are to be met as a priority? The emphasis of mainstream agendas suggests that the rights of the young are likely to be prioritised. Moreover, the suggestion, implicit in policy calls, that older persons are more vulnerable to poverty and exclusion than younger age-groups in fact lacks substantial corroborating evidence. Evidence of such age-related disparities remains inconclusive, limited in scope and/or hampered by the use of “problematic” methodologies (to be discussed below).

Ambiguity over policy priorities. Where governments, within constrained resources, are prepared to realise policies for older persons, they are uncertain as to which issues to address as a priority. They are confronted with the multifaceted nature of older person's vulnerability and contributions amid an almost complete lack of understanding of the priorities that older persons themselves would set in pursuit of a better life. Which facets should policy therefore focus upon and why? The ambiguity is heightened by a tendency of policy calls to conflate appeals for policy to support older people's contributions with calls to enhance their quality of life. The two, seemingly, are presumed to be congruent. This reflects a questionable assumption that older persons' present contributions to family and community are a) valued by older persons and young recipients alike; and b) are contributions that older persons, if given the choice, would wish to continue to make (to this extent). It is inferred, in other words, that existing patterns of intergenerational support, from old to young, are beneficial to, and desired by both parties, and thus should be strengthened (e.g. Temple 2007). Perplexingly, this assumption appears to hold even with respect to older persons' care burdens in the context of HIV/AIDS.17 Thus far, policy arguments have failed to consider (a) whether current intergenerational support from old to young (which is often necessitated precisely by social and/or economic deprivation) is, in fact, not desirable or beneficial for old and/or young; and (b) whether a need or demand, therefore, exists for formal mechanisms to assume these support functions.18

Ambiguity over policy approaches. Where governments have identified priority issues, or areas on which they wish to forge policies, they typically lack clarity on what approaches to take—on two fundamental levels. The first concerns the relative need for “age-segregated” measures targeted specifically at older persons versus “age-integrated” programmes aimed across adult age-groups. This ambiguity in part reflects a semantic confusion created by the emphasis on “mainstreaming,” which, as noted earlier, seeks to signal a shift away from policies targeting older persons as a separate group. Second, governments face uncertainty about the extent to which policy goals should be realised through strategies aimed at strengthening customary family support mechanisms (as envisioned in mainstream perspectives on home-grown African development), or through measures targeted at older individuals.

Step 3: Redressing the Ambiguities: Perspectives, Arguments and Queries

Building on a recognition of the ambiguities in current calls for policy on ageing, the third step needed to connect ageing with core development agendas is to identify guiding perspectives and consequent arguments and queries that can help to redress the uncertainties. We identify two major perspectives that should guide the effort to redress ambiguities in present calls for policy on ageing in SSA. First, a life course perspective19, and second an “intergenerational approach,” which emphasises the attainment of intergenerational equity20 and solidarity as a prerequisite for a “society for all ages” and, more broadly, for societal cohesion and development. Both perspectives are core principles underpinning the MIPAA (UN 2003a).21 Yet, neither the MIPAA nor subsequent advocacy efforts have systematically and critically applied them.

Redressing Ambiguities Over Cohorts and Time Horizons

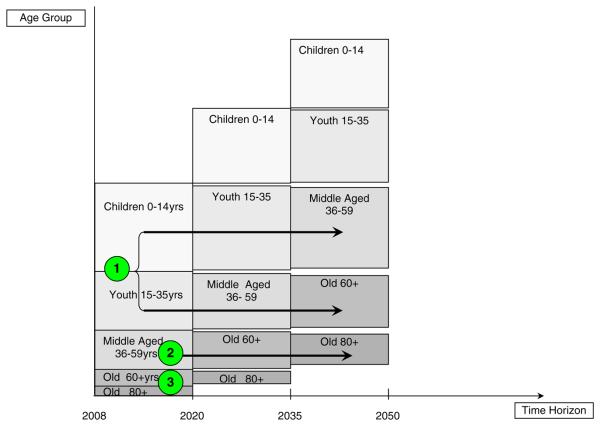

Application of a life course perspective locates three principal cohorts and time horizons for which a need for policy on ageing arises today. As Fig. 1 illustrates, these are (1) present cohorts of youth and children, who will begin to reach old age 25 years from now; (2) today's middle-aged cohorts who will successively enter old age over the coming two decades; and (3) current cohorts of older persons.

Fig. 1.

Principal cohorts and time horizons for policy on ageing

These time horizons deserve emphasis as research and advocacy on ageing in SSA have thus far largely overlooked the first two cohorts. The focus has been almost entirely on today's older persons. Yet, consideration of present child, youth, and middle aged cohorts is critical to the ageing agenda. It is important to recognise that current mainstream foci on health and education of the young, and employment promotion among those of working age essentially concur with the ageing agenda. To fully link the agendas on old and young, research and advocacy must address three major queries:

First, what strategies can be conceived to extend, complement or modify mainstream health and education policies for children and youth so as to optimise long-term life course effects on their capacity and well-being in old age? In this regard one may for example consider measures to redress the perplexing failure of current child and youth policies (not least the AU Youth Charter) to recognise a critical need for primordial and primary prevention efforts to avert the emergence of age-related chronic disease among these cohorts (Aboderin et al. 2001;WHO 2002, 2006).

Second, in what contexts and ways (if any) are present cohorts of older persons in a position to effectively contribute to child/youth-focused strategies at family, community or societal level? How desired are such contributions by older persons and the young; and what forms could potential intergenerational mechanisms take? (Consideration of the latter question may draw on the body of international literature on intergenerational programming (e.g. Newman 1998; Thang et al. 2003).

Third, what strategies can be forged to complement mainstream private enterprise and employment promotion policies, in order to lay foundations for old age income security for today's youth and middle aged? A critical, allied question is what old age income security systems—“customary” family based intergenerational transfers, public provision or individually based—will be most effective and desirable for these next generations of older persons?

Redressing Ambiguities Over Rights and Priorities of Age Groups

Application of an intergenerational approach points to a potentially more persuasive line of reasoning than advocacy's current emphasis on the rights of older persons. This, we suggest, is to assert a need for equity between old and young. To be sure, SSA countries' PRS agendas typically do not espouse attainment of equity as an explicit goal. However, individual sector policies (for example on health) often do (e.g. Ogunniyi and Aboderin 2007; Kenya Ministry of Health 2004; NFMOH 2005).22 Moreover, major donors increasingly advocate equity both as a value in itself and, significantly, as instrumental for economic growth. The World Bank (2005) for example, urges a need to ensure equality in individuals' opportunities to pursue a life of their choosing, and to avoid “deprivation in outcomes, particularly in health, education, and consumption” (p. xi). Of course, such mainstream considerations focus mainly on inequities among younger people on the basis of race, class, gender or caste. However, extending this focus to assert a need for equity between old and young is an avenue that advocacy and research on ageing in SSA need to pursue. Doing so effectively will hinge on a robust and objective illumination of two critical, inextricably linked queries. The first query concerns the relative extent of deprivation (in health, economic and social outcomes) of older persons compared to younger age groups. While some indicative evidence exists, for example, of age-related inequities in access to health care (e.g. McIntyre 2004), it is far from comprehensive and relies on rather unspecific household information. Similarly, the little evidence available on relative poverty risks among older and younger people remains inconclusive. The evidence is acutely limited, moreover, through its use of aggregate household (rather than individual-based) indicators, which fail to capture the critical factor of how resources are allocated between old and young in households and families (Aboderin 2008b; Barrientos 2002; Kakwani and Subbarao 2005). The second query regards the scope of health, economic or social inequalities within the older population. Accumulated evidence shows clear disparities in experiences of old age in SSA, with different levels of well-being between population groups. While sizeable proportions of older persons may be extremely vulnerable to poverty, ill-health or exclusion, this is certainly not the case for all (e.g. Aboderin 2008d). Yet—and despite routine mention of a need to consider the heterogeneity of older people—research and advocacy on ageing in SSA have not so far made old age inequalities a key focus of analysis.

Redressing Ambiguities Over Policy Priorities

Efforts to tackle uncertainties over policy priorities will need to hinge on systematic consideration and appreciation of the priorities that vulnerable older persons themselves perceive and set in the pursuit of a better life. A key query to be addressed in this regard is whether cash transfers—in the form of social pensions—are, indeed, the best way to enhance vulnerable older persons' quality of life? Or may there be other forms of social protection, such as access to specialist services, that are more fundamental to older people's quality of life and should be considered as a priority? For example, some tentative evidence suggests that good health and access to effective health care may be of overriding importance to older persons (Aboderin 2000;Marin 2008).

Redressing Ambiguities Over Policy Approaches

Addressing present ambiguities on the relative need for “age-segregated” versus “age-integrated” policy measures requires clarification of the semantic uncertainty inherent in the “mainstreaming” argument. Specifically, advocacy needs to assert that while mainstreaming is meant to deter targeting the aged as a separate group, it can nonetheless involve a need—within or across individual sectors—for special measures or programmes aimed only at older people. Establishing whether such a need exists must be based on efforts, within each sector, to illuminate the specific nature and causes of older person's vulnerability and to analyse what responses can effectively remedy these. In the health sector, for example, consideration would be given to whether older persons' lack of access to health care can be adequately remedied through a general expansion of services for age-related disease, or whether specific measures to target older persons' access barriers are indicated (Aboderin 2008a).

Uncertainties on whether policies on ageing should be targeted at older individuals or at families (with a view to promoting customary support mechanisms), can be redressed by applying an intergenerational perspective. Such a perspective demands that judgements on the above be based on (a) a comprehension of the kinds of intergenerational support flows and dependencies older and younger people actually desire, and (b) a sound assessment of how family or individual based policy measures (would) shape such flows, and consequently intergenerational cohesion or conflict within families. Such an approach is needed, among others, to assess the current practice (in the few countries with social pensions) of allocating cash transfers directly to older persons. An argument for this approach in the context of pervasive poverty, as we have seen, centres on its redistributive benefits: money given to older people is shared with their children and grandchildren. It is important to recognise that such allocation effectively establishes a particular “moral” order and direction of intergenerational material support flows in families (Finch 1989). Moreover—in contexts of massive un- and underemployment and lacking social security provision for the unemployed—social pensions (which are often the only secure income for poor households) can create dependencies of youth and middle aged persons on older pension recipients (Ferreira 2006b; Gwebu 2008; Møller 2008; Møller and Ferreira 2003). An important query, then, is to what extent (and in what circumstances) such an order of intergenerational dependencies and support flows is desired by old and young, as opposed to allocation of cash transfers to the young to share with the old?

Step 4: Addressing Major Information Needs

The above queries and arguments point clearly to a number of fundamental information needs. The fourth step required to effectively connect ageing and mainstream development agendas is to develop and conduct incisive research, across SSA countries, to address these evidence gaps. We discern five major areas for research, which, interestingly, are not fully captured by existing research agendas on ageing for Africa (Aboderin 2005; Cohen and Menken 2006; UN/IAGG 2008)

Age-related Disparities in Health and Poverty

Research is needed to elucidate (a) the relative vulnerability of older persons to detrimental health and economic outcomes, as compared to younger age-groups, and (b) the individual, family or structural factors that give rise to age-related disparities. Such research must develop and use more sensitive survey measures than are hitherto available, for capturing older individuals' health and economic well-being. Current measures such as self-reports of health or disease conditions, as well as diagnoses of cognitive or mental disease, are problematic in the SSA setting. Similarly, as indicated earlier, routine household-based poverty indicators are limited by their failure to capture intra-household (or family) resource allocation between old and young (see Aboderin 2008b; Cohen and Menken 2006; Kuhn et al. 2006).

Inequalities in Old Age

Allied to research on age-related disparities is a need for investigations to illuminate health and economic inequalities within the older population itself. Studies are needed in particular to document the precise scope and patterns of such old age inequalities in SSA societies and the life course or contemporary factors that give rise to them. As above, such research must build on improved measures of older individuals' health and poverty status.

Intergenerational Connections

Research is required to explore older and younger generations' experiences of, and perspectives on, intergenerational support and solidarity in their families. Specifically, investigations are needed to (a) examine the benefits and potentially detrimental impacts on young and old of existing intergenerational family support relationships (e.g. Lloyd-Sherlock and Locke 2008), and (b) generate understanding of the forms of intergenerational support (at family or societal level) that old and young aspire to at present and for the future. To underscore the relevance of giving voice to such aspirations (in the context of mainstream development debates), we suggest that inquiries draw broadly on the capability approach (Sen 1989, 1999) and its central notion of development as “expanding the freedom of individuals to pursue the life they have reason to value”. Given its intellectual and ethical force, the approach is emerging as a salient alternative to dominant neo-liberal perspectives of development and underpins, among others, the United Nations “human development” paradigm (Clark 2006; Jolly 2003; Kuonqui 2006; UNDP 2006).

Quality of Life in Old Age

A fourth research need arises in the area of quality of life (QOL) in old age. The MIPAA and AU Plan, as noted earlier, both assert enhancement of older persons' QOL as an ultimate policy goal. Yet, neither plan clarifies—and we have very little information on—what “quality of life” in fact entails for older persons in the SSA setting. This gap in understanding contrasts with the burgeoning evidence on this subject in Europe and North America and nascent research in Asia (Daatland 2005; Mollenkopf and Walker 2007; Nilsson et al. 2005). A salient strand of recent western evidence underscores the importance of considering older persons' own conceptions or “lay theories” of QOL as a basis for meaningfully assessing QOL in different cultural settings, highlighting limitations in existing standardised instruments (Bowling 2007; Bowling and Gabriel 2007; Mollenkopf and Walker 2007). Critical European contributions, moreover, emphasise a need to understand and pursue older people's well-being, or “social quality”, within the context of their communities Walker (2006). Both principles are highly instructive for research on old age QOL in SSA, which is needed to pinpoint priorities for ageing policy. To do so, research must capture the values and priorities that older persons hold in their pursuit of a good old age and the obstacles they face in realising them. We suggest that these values and priorities can be usefully explored by drawing on the capability approach (Sen 1989, 1999) and an insightful application of it by Grewal et al. (2006).23 Their application makes important conceptual distinctions between: (a) The attributes, circumstances or activities (‘doings’ or beings') that older people aspire to as essential to the quality of their daily lives (i.e. their essential valued functionings); (b) the abilities they need to achieve these (i.e. their essential capabilities); and (c) the key factors that might obstruct their gaining access to these abilities (i.e. key constraints on capabilities).

Such a focus on valued “doings” or “beings” reverberates with recent developments in psychological debates on subjective well-being (Kahneman et al. 2006), which posit that happiness is related to how people spend their time, rather than to consumption or possession of material goods or income. To further conceptualise how policy targeted at older persons or younger age-groups may foster valued functionings in old age, one may consider two principal influences on an older individual's capabilities, as pinpointed by Lloyd-Sherlock (2002), namely:

Their internal capabilities (e.g. work skills they developed during the life course), which are shaped by the functionings they were able, and chose, to pursue earlier in their life (e.g. whether they received education or worked).

Present structural constraints or opportunities imposed by their external environment (e.g. whether employment opportunities exist for them).

Policy Audit

A final research need—required to provide an effective backdrop for emergent evidence in the above four areas—is the conduct of a systematic “policy audit” across SSA countries. An audit is needed to establish the precise extent and nature of existing policy on ageing, and to illuminate key factors that have shaped them. Ideally, such an audit would form part of a forthcoming process of review and appraisal of implementation of the AU Plan on Ageing.

Methodological Approaches: Some Principles

Detailed methodological and conceptual approaches for research on the above areas will need to be developed according to individual projects' research questions, study populations and available resources. However, a number of bedrock principles exist that research design should embrace in a quest to produce policy—as well as scientifically relevant knowledge. To be germane to policy, investigations must, above all, seek to actively bridge the often lamented gap between research and policy making (UN/IAGG 2008). A basic, and crucial, step towards this end is to base their design and implementation—from inception to dissemination—on strategic consultative relationships with key policy- and decision makers. To ensure its scientific relevance, research needs to reflect critically on salient theoretical or conceptual approaches and debates in gerontology or other relevant disciplines, such as public health or development studies. An aim must be to advance these debates in light of African realities. To this end inquiries must develop understanding and theoretical ideas that are grounded in the meanings and motives of African actors—rather than derived from a reliance on a priori (mostly western) theories or concepts (Aboderin 2004; Ferreira 2005, 1999). In doing so, research needs to appreciate the great social, economic, geographical and cultural diversity that exists within and between SSA countries, and avoid generalisation from one SSA society to others. Finally, investigations must, as a matter of course (a) define (and where feasible, compare) successive cohorts over time in order to distinguish age and cohort effects (Riley et al. 1988); and (b) illuminate the interplay between micro-(individual), meso-(family, community) and macro-structural factors in shaping the phenomena under investigation (Baars et al. 2006; Giddens 1991; Guba and Lincoln 1994; Ryff and Marshall 1999). In order to achieve the above, and to generate statistically powerful evidence, mixed-method approaches employing a combination of interpretive qualitative and larger-scale quantitative data collection are essential (Creswell and Plano Clark 2006).

Concluding Remarks

We began this paper by reflecting on the contexts of, and key reasons for, a present impasse in policy action on ageing and older persons in sub-Saharan Africa. We argued that in order to overcome this deadlock, research and advocacy must explicate, far more clearly than hitherto, what the rationales and required approaches are for policy on ageing in the context of mainstream SSA development agendas. Or, put differently, where and how ageing and mainstream development agendas for the sub-region interconnect. Subsequently, we offered a set of systematic steps and approaches that could provide a framework for addressing this challenge. In concluding, we return to—and re-assert—a need for SSA countries to realise the specific commitment they made to both the MIPAA and the AU Plan, which is to ensure older persons' rights and participation as contributors to and beneficiaries of development. Such realisation of a commitment implies a need for research and advocacy efforts to consider the lines of reasoning we have proposed and to address, in particular, the key research challenges we have outlined. The MIPAA and AU Plan themselves emphasise a need for research to enable and support implementation of their recommendations. Indeed, review and appraisal of progress in the implementation of the MIPAA has highlighted a lack of research as a central drawback (UN/DESA 2008).

Acknowledgements

Research for this article was supported by The Wellcome Trust (Grant No. WT078866MA).

Footnotes

In some SSA countries up to 80% of the urban population live in slums. Globally, SSA is estimated to have the highest percentage of slum dwellers. Corresponding figures for Southern, Eastern and South-east Asia are 43%, 37% and 28%, respectively (UN 2007a; UN Habitat 2008).

Though the mentioned social ills are common to many SSA nations, countries vary in the spectrum, extent and depth of the challenges they face, which reflects differences in historical, geographical and governance contexts (Nugent 2004). As regards the HIV/AIDS crisis, the most affected countries are in Southern Africa, with prevalence rates typically exceeding 15% of the adult population. By contrast, all West African nations have estimated prevalence rates below 4%, many even below 2% (UNAIDS/WHO 2007). Armed conflict is most concentrated in countries in the greater Horn of Africa, including Darfur and Southern Sudan, Northern Uganda and the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

It is important to bear in mind the tenuousness of current demographic projections for SSA, which reflects the dearth of quality vital statistics data needed to furnish solid estimates. As Velkoff and Kowal (2007) discuss, fewer than ten SSA countries have vital registration systems that produce usable fertility and mortality data and only two systems (Mauritius and Seychelles) cover at least 80% of the population. Few SSA countries have recent census data, and for those that do, the quality of the data is uneven. Given the lack of robust vital statistics, population projections for SSA are typically derived from Demographic and Health Survey data, which are used to produce estimates of fertility and infant and child mortality. These projections are then matched to model life tables to produce adult mortality estimates.

The lower age cut-off for “older persons” used by the UN is 60 years. This definition of “old age” is becoming increasingly entrenched in the international discourse—intended, among other, for comparative analyses. However, use of a chronological definition of “old age” set at 60 years has severe limitations, and in truth is inappropriate in African settings (Apt 1997; HAI 2002).

Sub-regional differences exist within this broad picture: the rise in the number of older people will be greatest, around 300%, in East, West and Central Africa. Southern Africa, SSA's richest sub-region, will see a much lower (only two-fold) increase in the numbers of older people. However, the population share of older people in this sub-region, 6.6% at present and projected to rise to 13.3% by 2050, is higher and will be more rapid than in any of the other sub-regions.

- The UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).

- The African Charter of Human and People's Rights (1981).

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (1976).

- The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (1976).

- The UN Declaration on the Right to Development (1986). (See AU/HAI 2003; UN 2002.)

A prime example of such personal initiative is that of Senegalese president Abdoulaye Wade, which lead to the introduction of “Plan Sesame”'—a free health care policy for all Senegalese citizens aged 60 and above (see Aboderin 2008a).

A similar process of review and appraisal of implementation of the AU Plan is planned by the African Union (HAI, personal communication, August 2007).

In Lesotho, pension beneficiaries are estimated to share 65% of their pension income with their children and grandchildren (HAI, personal communication, August 2007).

- Halve the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day and the proportion that suffers from hunger.

- Attain universal primary education in all countries.

- Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education and at all levels of education.

- Reduce mortality by two-thirds among children younger than five years.

- Reduce the maternal mortality ratio by three-quarters.

- Halt and begin to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS, and the incidence of malaria and other major diseases.

- Halve the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water, and by 2020, achieve significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers.

- Develop a global partnership for development (UN 2000).

There is, of course, considerable debate on the question of whether the demographic dividend indeed affects economic growth and development (see Birdsall et al. 2003; Lee 2003).

The charter builds on the 2004 NEPAD (New Economic Partnership for African Development) Strategic Framework for Youth Programme (AU 2006a).

The charter requires governments to recognise not only the fundamental rights of youth, but a range of additional social and economic rights, namely to own and inherit property; to social, economic, political and cultural development; to participate in all spheres of society; to a good quality education; to a standard of living adequate for their holistic development; to be free from hunger; to benefit from social security, including social insurance; to gainful employment; and to enjoy the best attainable state of physical, mental and spiritual health (AU 2006a).

Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), with their emphasis on the instrumentality of the free market, in fact led to a deterioration of social conditions for the poor (AU 2004a; Soludo and Mkandawire 1999).

Modernisation theory perspectives, which have effectively been debunked in the scholarly literature, came to dominate thinking on development in the 1970s, fuelled by Rostow's influential notion of the “Stages of Economic Growth” (Rostow 1960).

To this end, the African Union ratified the African Cultural Charter in 1999 and planned a first pan-African cultural congress on the theme of “Culture, Integration and African Renaissance” (see AU 2006b; OAU 1999).

The MIPAA and the AU Plan acknowledge indirectly that these contributions are “unexpected” and “difficult” for older people.

The only place where MIPAA does consider the question of preference between informal/family and formal intergenerational support is in relation to caregiving to frail older persons —where consideration of formal support is directed primarily to industrialised countries.

A life course perspective recognises that outcomes at later stages of life (e.g. in old age) are shaped not only by present conditions, but exposures, contexts and relationships in earlier life phases (see Elder et al. 2003; Kuh et al. 2003).

Intergenerational equity is recognised as a key element of intergenerational solidarity. More generally, a lack of clarity remains on what “intergenerational solidarity” as a policy goal entails (Aboderin 2008c).

The AU Plan, oddly makes no reference to either perspective.

A focus on equity in health sector policies is part of a wider and intensifying international emphasis on the achievement of equity in health and a connected focus quest to address the social determinants of ill-health (WHO 2008).

The capability approach considers two main dimensions: (1) What people have reason to value doing or being—their valued “functionings,” and (2) people's abilities, freedom or opportunities to pursue or achieve these functionings—their “capabilities” (see Alkire 2006; Clark 2006).

References

- Aboderin I. Social change and the decline in family support for older people in Ghana: an investigation of the nature and causes of shifts in support. University of Bristol; UK: 2000. PhD Thesis, School for Policy Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin I. Modernisation and ageing theory revisited: current explanations of recent developing world and historical western shifts in material family support for older people. Ageing and Society. 2004;24:29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin I. A strategic framework and plan for research. Oxford Institute of Ageing, University of Oxford; 2005. Understanding and responding to ageing, health, poverty and social change in subSaharan Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin I. Intergenerational support and old age in Africa. Transaction; Piscataway: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin I. Ageing. In: Desai V, Potter R, editors. The companion to development studies. Hodder Arnold; London: 2007. pp. 418–423. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin I, Gachuhi M. AFRAN Policy-Research Dialogue Series, Report 01-2007. Oxford Institute of Ageing, University of Oxford; 2007. First East African policy-research dialogue on ageing. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin I. AFRAN Policy-Research Dialogue Series, Report 01-2008. Oxford Institute of Ageing, University of Oxford; 2008a. Advancing health service provision for older persons and age-related noncommunicable disease in sub-Saharan Africa: identifying key information and training needs. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin I. West Africa. In: Uhlenberg P, editor. International handbook of the demography of ageing. Springer; New York: 2008b. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin I. Intergenerational solidarity and old age support in Africa and Asia: what roles for family and state?; Paper presented at the 4th Ageing & Generations Congress; St. Gallen, Switzerland. 28–30 August.2008c. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin I. Global ageing: perspectives from sub-Saharan Africa. In: Phillipson C, Dannefer D, editors. International handbook of social gerontology. Sage; Newbury Park: 2008d. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin I, Kalache A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch JW, Yajnik CS, Kuh D, et al. Life course perspectives on coronary heart disease, stroke and diabetes: the evidence and implications for policy and research. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- African Development Bank (ADB) African development report 2006. Aid, debt relief and development in Africa. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- African Union (AU) Africa: our common destiny. Guideline document. African Union; Addis Ababa: 2004a. [Google Scholar]

- African Union (AU) Strategic plan of the African Union commission. Volume 1: vision and mission of the African Union. African Union; Addis Ababa: 2004b. [Google Scholar]

- African Union (AU) Strategic plan of the African Union commission. Volume 2: 2004–2007 strategic framework of the commission of the African Union. African Union; Addis Ababa: 2004c. [Google Scholar]

- African Union (AU) African youth charter. African Union; 2006a. http://www.uneca.org/adf/docs/African_Youth_Charter.pdf. Accessed 8 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- African Union (AU) Pan African cultural congress. African Union; 2006b. http://www.africa-union.org/root/au/Conferences/Past/2006/November/sa/Pan_African/cultural_Congress.htm). Accessed 8 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- African Union (AU) Declaration of African Union ministers in charge of youth. African Union; 2008. http://www.africa-union.org/root/AU/index/archive1_february_2008.htm. Accessed 20 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- African Union/HelpAge International (AU/HAI) Policy framework and plan of action on ageing. HAI Africa Regional Development Centre; Nairobi: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire S. Valuing freedoms. Sen's capacity approach and poverty reduction. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Apt N. Ageing in Africa. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Apt N. 30 years of African research on ageing: history, achievements and challenges for the future. Generations Review. 2005;15:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Asagba A. Research and the formulation and implementation of ageing policy in Africa: the case of Nigeria. Generations Review. 2005;15:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baars J, Dannefer D, Phillipson C, Walker A, editors. Aging, globalization and inequality: the new critical gerontology. Baywood; Amityville: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos A. Old age, poverty and social investment. Journal of International Development. 2002;14:1133–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall N, Kelley AC, Sinding S. Population matters: demographic change, economic growth and poverty in the developing world. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan A. Labour market effects of population aging. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper no 8640. NBER; 2001. http://www.nber.org/papers/w8640. Accessed 3 January 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A. Quality of life in older age: what older people say. In: Mollenkopf H, Walker A, editors. Quality of life in old age. International and multidisciplinary perspectives. Springer; Dordrecht: 2007. pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A, Gabriel Z. Lay theories of quality of life in older age. Ageing and Society. 2007;27:827–848. [Google Scholar]

- Bramucci G, Erb S. An invisible population: displaced older people in West Darfur. Global Ageing. 2007;4(3):23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. Capability approach. In: Clark D, editor. The Elgar companion to development studies. Edward Elgar; Cheltenham: 2006. pp. 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B, Menken J. Report—aging in sub-Saharan Africa: recommendations for furthering research. In: Cohen B, Menken J, editors. Aging in sub-Saharan Africa: recommendations for furthering research. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 7–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Africa (CfA) Our common interest. Report of the Commission for Africa. Commission for Africa Secretariat; London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Daatland SO. Quality of life and ageing. In: Johnson ML, editor. The Cambridge handbook of age and ageing. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2005. pp. 371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon B. Global social policy and governance. Sage; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Department for International Development (UK) (DFID) Removing unfreedoms. The millennium development goals. DFID; 2006. http://www.removingfreedoms.org/development_goals.htm. Accessed 5 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Jr., Kirkpatrick Johnson M, Crosnoe R. The emergence and development of the life course theory. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the life course. Plenum; New York: 2003. pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M. Building and advancing African gerontology. Southern African Journal of Gerontology. 1999;8:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M. Research on ageing in Africa. What do we have, not have and should we have. Generations Review. 2005;15:32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M. HIV/AIDS and older people in sub-Saharan Africa: towards a policy framework. Global Ageing. 2006a;4(2):56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M. The differential impact of social-pension income on household poverty alleviation in three South African ethnic groups. Ageing and Society. 2006b;26:337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Finch J. Family obligations and social change. Polity; Cambridge: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. Modernity and self identity. Polity; Oxford: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal I, Lewis J, Flynn T, Brown J, Bond J, Coast J. Developing attributes for a generic quality of life measure for older people: preferences or capabilities. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:1891–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1994. pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Gwebu T. Intergenerational solidarity and old age support in Botswana: what roles for family and state?; Paper presented at the 4th Ageing & Generations Congress; St.Gallen, Switzerland. 28–30 August.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harper S. Ageing societies. Hodder Arnold; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- HelpAge International (HAI) Participatory research with older people: a sourcebook. HelpAge International; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- HelpAge International (HAI) Age and security. How social pensions can deliver effective aid to poor older people and their families. HelpAge International; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- HelpAge International (HAI) Social cash transfers for Africa. A transformative agenda for the 21st century. HelpAge International; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) Rural poverty in Africa. IFAD; 2007. http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org/english/regions/africa/index.htm. Accessed 4 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) Poverty reduction strategy papers. A factsheet. IMF; 2008. http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/prsp.htm. Accessed 3 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly R. Human development and neo-liberalism: paradigms compared. In: Fukuda-Parr S, Shiva Kumar AK, editors. Readings in human development. Oxford University Press; New Dehli: 2003. pp. 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade D, Schwarz N, Stone AA. Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science. 2006;312:1908–1910. doi: 10.1126/science.1129688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakwani N, Subbarao K. Ageing and poverty in Africa and the role of social pensions. United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) International Poverty Centre, Working Paper No.8. UNDP; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Ministry of Health . National health sector strategic plan II (NHSSP II) Ministry of Health; Nairobi: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J. Life course epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:778–783. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R, Rahman O, Menken J. Survey measures of health: how well do self-reported and observed indicators measure health and predict mortality. In: Cohen B, Menken J, editors. Aging in sub-Saharan Africa: recommendations for furthering research. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 314–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuonqui C. Is human development a new paradigm for development? Capabilities approach, neoliberalism and paradigm shifts; Paper presented at the Human Development and Capability Association (HDCA) International Conference on Freedom and Justice; Groningen, the Netherlands. August.2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. The demographic transition. Three centuries of fundamental change. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2003;17:176–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Sherlock P. Nussbaum, capabilities and older people. Journal of International Development. 2002;14:1163–1173. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Sherlock P, Locke C. Vulnerable relations: lifecourse, well-being and social exclusion in Buenos Aires. Ageing and Society. 2008;28(6):779–804. [Google Scholar]

- Luckham R, Ahmed L, Muggah R, White S. Conflict and poverty in SSA: an assessment of the issues and evidence. IDS Working Paper, 128. Institute for Development Studies; Sussex: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marin PP. Building capacity to implement the Madrid international plan of action on ageing; Paper presented at the 4th Ageing & Generations Congress; St. Gallen, Switzerland. 28–30 August.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall VW, Heinz W, Krueger H, Verma A, editors. Restructuring work and the life course. University of Toronto Press; Toronto: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mba CJ. Population ageing and survival challenges in rural Ghana. Journal of Social Development in Africa. 2004;19:90–112. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre D. Health policy and older people in Africa. In: Lloyd-Sherlock P, editor. Living longer. Ageing, development and social protection. Zed Books; London: 2004. pp. 160–183. [Google Scholar]

- Mollenkopf H, Walker A, editors. Quality of life in old age. International and multidisciplinary perspectives. Springer; Dordrecht: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Møller V. Strengthening intergenerational solidarity in South Africa in the time of HIV/AIDS; Paper presented at the 4th Ageing & Generations Congress; St. Gallen, Switzerland. 28–30 August.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Møller V, Ferreira M. Report, Institute of Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University and The Albertina and Walter Sisulu Institute of Ageing in Africa. University of Cape Town; 2003. Getting by… benefits of non-contributory pension income for older South African households. [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. Intergenerational programs: past, present, and future. Taylor and Francis; Washington DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nhongo T. Age discrimination in Africa; Paper presented at the 8th Global Congress of the International Federation on Ageing (IFA); Copenhagen, Denmark. 30 May–2 June 2006.2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nhongo T. Capacity building needs in Africa; Paper presented at the 4th Ageing & Generations Congress; St. Gallen, Switzerland. 28–30 August.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health (NFMOH) Revised national health policy. Federal Ministry of Health; Abuja: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nigeria National Planning Commission (NNPC) National economic empowerment and development strategy NEEDS. Federal Government of Nigeria; Abuja: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson J, Grafstroem M, Zaman S, Kabir ZN. Role and function: aspects of quality of life of older people in Bangladesh. Journal of Aging Studies. 2005;19:363–374. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent P. Africa since independence. Palgrave Macmillan; Basingstoke: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunniyi A, Aboderin I. Hospital-based care of patients with dementia in Ibadan, Nigeria: practice, policy contexts and challenges. Global Ageing. 2007;4(3):45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Olukoshi A, Nyamnjoh FB. Rethinking African development. CODESRIA Bulletin. 2005;3 & 4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation of African Unity (OAU) Cultural charter for Africa. Organisation for African Unity; Addis Ababa: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Porteous T. British Government policy in Sub-Saharan Africa under new Labour. International Affairs. 2005;81:281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Riley MW, Foner A, Waring J. Sociology of age. In: Smelser N, editor. Handbook of sociology. Sage; Beverly Hills: 1988. pp. 243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Rostow WW. The stages of economic growth. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C, Marshall VW, editors. The self and society in aging processes. Springer; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer U. Vertrauliches programm für den weltwirtschaftsgipfel 2007. Sueddeutsche Zeitung; 2006. http://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/artikel/758/88670. Accessed 19 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Development as capability expansion. Journal of Development Planning. 1989;19:41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Development as freedom. Random House; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Soludo CC, Mkandawire T. Our continent. Our future. African perspectives on structural adjustment. IDRC/CODESRIA/Africa World Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Temple L. Intergenerational approaches. Promoting solidarity. Ageways, 69. HelpAge International; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thang LL, Kaplan M, Henkin N. Intergenerational programming in Asia: converging diversities toward a common goal. Intergenerational Programming Quarterly. 2003;1(1):49–69. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) Report of the world assembly on aging, Vienna, 26 July to 6 August. United Nations; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (UN) Millennium declaration. United Nations; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- UnitedNations. (UN) Madridinternational planofactiononageing(MIPAA) United Nations; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) Mainstreaming ageing into national policy frameworks. An Introduction. United Nations; 2003a. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/documents/workshops/Vienna/issues.pdf. Accessed 20 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) Report of the interregional consultative meeting on national implementation of the Madrid international plan of action on ageing; Vienna, Austria. 9–11 December 2003; United Nations; 2003b. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/documents/workshops/Vienna/vienna_report.pdf. Accessed 20 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) The millennium development goals report 2007. United Nations; New York: 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) Millennium development goals. 2007 progress chart. UN; New York: 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) The millennium development goals report 2008. United Nations; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) Millennium Project . Investing in development. A practical plan to achieve the millennium development goals. United Nations; New York: 2005. http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/reports/index.htm. Accessed 12 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations/International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (UN/IAGG) Research agenda on ageing for the 21st century. United Nations; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . 2008 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) UNAIDS; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS/World Health Organization (UNAIDS/WHO) AIDS epidemic update: December 2007. A Report of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the WHO. UNAIDS and WHO; Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN/DESA) Regional dimensions of the ageing situation. United Nations; New York: 2008. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/documents/publications/cp-regional-dimension.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human development report 2006. Beyond scarcity: power, poverty and the global water crisis. Palgrave Macmillan; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human development report 2007/8. Fighting climate change: human solidarity in a divided world. Palgrave Macmillan; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) Concept paper. The Fifth African Development Forum (ADF-V) UNECA; 2006. Youth and leadership in the 21st century. http://www.uneca.org/ADF/Concept_Paper.htm. Accessed 12 April 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) The state of older persons in Africa—2007. Regional review and appraisal of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing. Draft report. UNECA; Addis Ababa: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA) Poverty reduction strategies: frameworks for development. UNFPA; 2005. http://www.unfpa.org/pds/poverty_reduction.htm. Accessed 3 January 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Habitat (UN HABITAT) State of the world's cities 2008/2009. Harmonious cities. UN HABITAT; Nairobi: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Division (UNPD) World population policies 2005. UNPD; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Division (UNPD) Population ageing 2006. UNPD; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Division (UNPD) World population ageing 2007. UNPD; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Division (UNPD) World population prospects: the 2006 revision. UNPD; 2008. http://esa.un.org/unpp/. Accessed 3 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Velkoff VA, Kowal PR. Current Population Reports, P 95/07-1. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2007. Population ageing in sub-Saharan Africa: demographic dimensions 2006 U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Walker A. Reexamining the political economy of ageing: understanding the structure/agency tension. In: Baars J, Dannefer D, Phillipson C, Walker A, editors. Aging, globalization and inequality. The new critical gerontology. Baywood; Amityville: 2006. pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World development report 2006: equity and development. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World development report 2007: development and the next generation. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . Country classification. World Bank; 2008a. http://go.worldbank.org/K2CKM78CC0. Accessed 4 July 2008. [Google Scholar]