Abstract

How vascular tubes build, maintain and adapt continuously perfused lumens to meet local metabolic needs remains poorly understood. Recent studies showed that blood flow itself plays a critical role in the remodelling of vascular networks1,2, and suggested it is also required for lumenisation of new vascular connections3,4. However, it is still unknown how haemodynamic forces contribute to the formation of new vascular lumens during blood vessel morphogenesis.

Here we report that blood flow drives lumen expansion during sprouting angiogenesis in vivo by inducing spherical deformations of the apical membrane of endothelial cells, in a process that we termed inverse blebbing. We show that endothelial cells react to these membrane intrusions by local and transient recruitment and contraction of actomyosin, and that this mechanism is required for single, unidirectional lumen expansion in angiogenic sprouts.

Our work identifies inverse membrane blebbing as a cellular response to high external pressure. We show that in the case of blood vessels such membrane dynamics can drive local cell shape changes required for global tissue morphogenesis, shedding light on a pressure-driven mechanism of lumen formation in vertebrates.

Blood vessels form a vast but highly structured network that pervades all organs in vertebrates. During development as well as in pathological settings in adults, vascular networks expand through a process known as sprouting angiogenesis. New blood vessels form from the coordinated migration and proliferation of endothelial cells into vascular sprouts. Subsequent fusion of neighbouring sprouts, defined as anastomosis, then leads to the formation of new vascular loops, whose functionality relies on their successful lumenisation and perfusion5. During anastomosis, endothelial lumens form both through apical membrane invagination into single anastomosing cells (unicellular lumen formation), and through de novo apical membrane formation at their nascent junction (multicellular lumen formation)3,4. Since the tip of endothelial sprouts can be occupied by either one or several cells as they compete for the tip position6,7, we asked whether similar mechanisms of lumen formation apply to unicellular and multicellular endothelial sprouts prior to anastomosis.

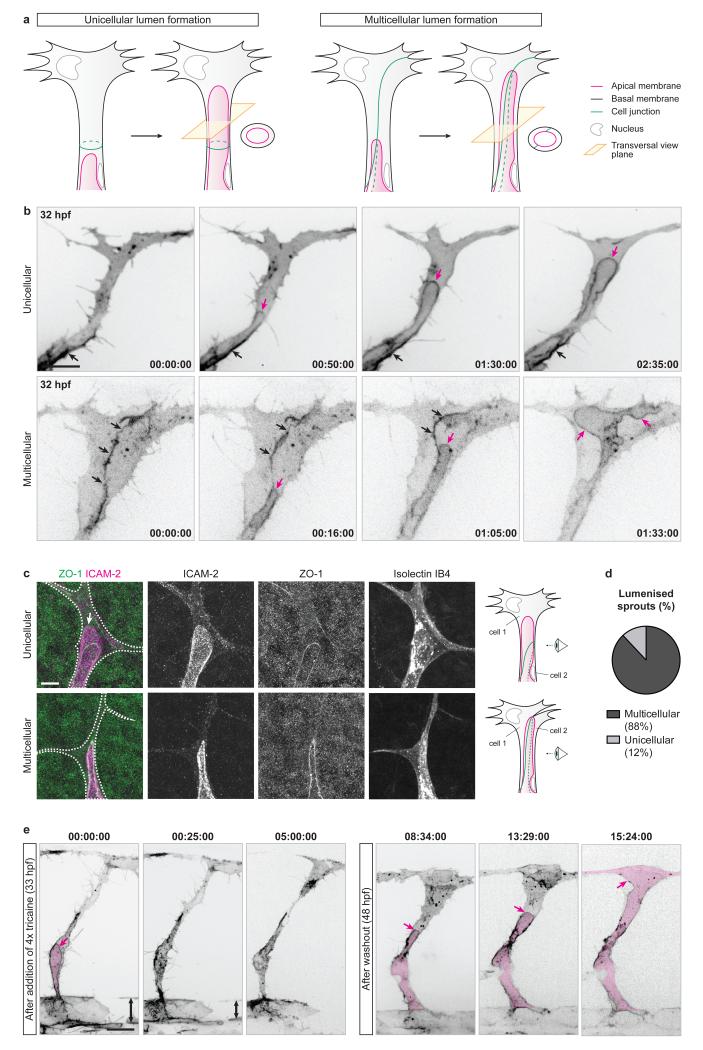

Using a zebrafish transgenic line expressing an mCherry-CAAX reporter for endothelial plasma membrane (Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916), we imaged lumen formation in tip cells as they sprout from the dorsal aorta (DA) to form the intersegmental vessels (ISVs) from 30 hours post-fertilisation (hpf). We found that lumens expand in sprouting ISVs prior to anastomosis, and do so by invagination of the apical membrane either into single tip cells, or along cell junctions when the tip of a sprouting ISV is shared between several cells (Fig. 1a,b).

Figure 1. Blood pressure drives unicellular and multicellular lumen expansion in angiogenic sprouts.

a) Schematic illustration of unicellular and multicellular lumen formation in angiogenic sprouts.

b) Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 embryos were imaged from 32 hpf. Black arrows, cell junction. Magenta arrows, apical membrane. Time is in hours:minutes:seconds. Scale bar is 10 μm. Images are representative of 10 embryos analysed.

c) Mouse retinas were harvested at P6 and stained for ICAM-2, ZO-1 and Isolectin IB4. Isolectin IB4 staining was used to draw the cell outline (white dotted line). White arrow, unicellular membrane invagination. Scale bar is 10 μm.

d) The number of endothelial sprouts with unicellular or multicellular lumens were quantified in P6 mouse retinas stained for ICAM-2 and ZO-1 (n=487 sprouts from 9 retinas).

e) Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 embryos were imaged from 33 hpf after the addition of 4x tricaine. Blood flow stopped after 20-25 minutes of treatment, leading to a decrease in blood pressure noticeable through the decrease in diameter of the dorsal aorta (double-headed arrow). At 48 hpf, embryos were returned to 1x tricaine and imaged further. Magenta arrows, apical membrane. Magenta filling, lumen. Times are in hours:minutes:seconds and correspond to the times after addition of 4x tricaine (left panels) and after washout (right panels). Scale bar is 20 μm. Images are representative of 7 embryos analysed.

To test if this mechanism of lumen formation is conserved in other vertebrates, we performed immunolabelling of the apical membrane (ICAM-2, Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 2) and cell junctions (ZO-1, Zona Occludens 1) in developing mouse retinas at post-natal day 6 (P6). As in zebrafish ISVs, we observed that lumens are present either as membrane invaginations into single tip cells, or between cells when they share the tip position (Fig. 1c,d), suggesting that endothelial sprouts undergo both unicellular and multicellular lumen formation in the mouse retina.

Whereas lumens form independently of blood flow during dorsal aorta formation8-10, previous studies suggested both flow-independent and flow-dependent lumen formation in ISVs11 and during anastomosis3,4. To test whether lumen expansion in angiogenic sprouts requires blood perfusion, we treated Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 embryos with a four-fold higher dose of tricaine methanesulfonate (4x tricaine) than the dose normally used for anesthesia. Under these conditions, embryos show lower heart rate, loss of blood flow and decreased blood pressure4. Upon the addition of 4x tricaine mid-way through ISV lumenisation, lumens did not expand further and eventually collapsed (Fig. 1e). However, when placed back in 1x tricaine at 2 days post-fertilisation (dpf), the embryos recovered normal heartbeat, blood flow was reestablished (as assessed by the presence of circulating red blood cells) and lumens expanded within the ISVs (Fig. 1e). Together, these data show that lumen expansion in angiogenic sprouts in vivo is dependent on cardiac activity and thus on haemodynamics.

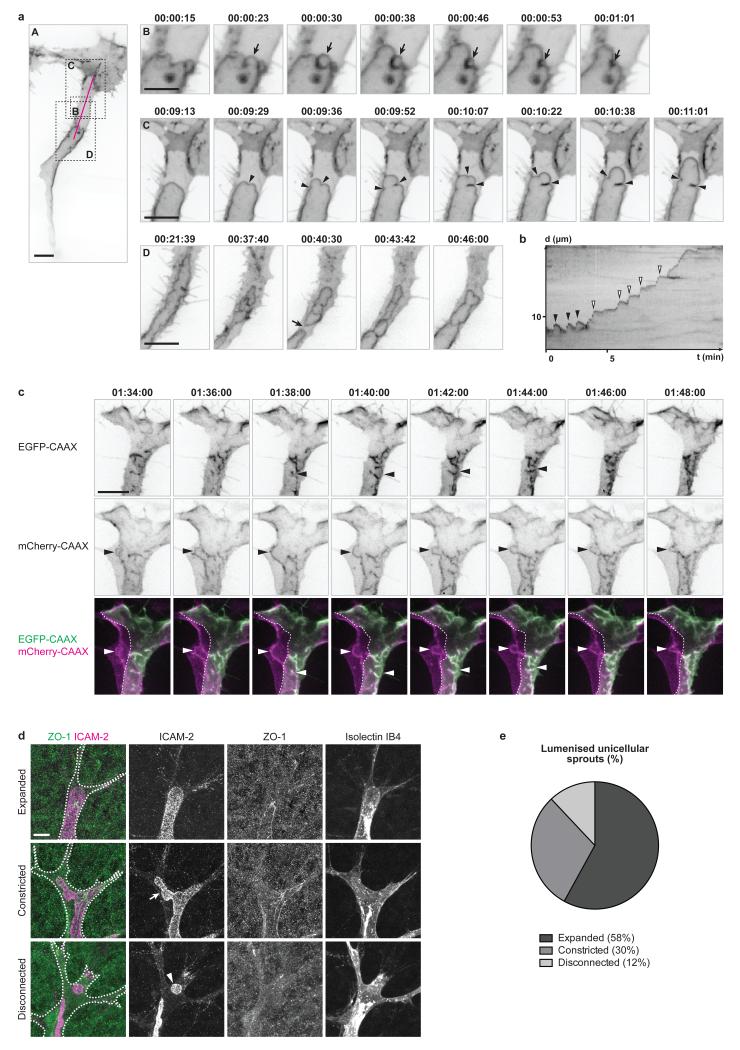

Using mosaic expression of an endothelial-specific EGFP-CAAX reporter for plasma membrane (fli1ep:EGFP-CAAX) and high spatial and temporal resolution imaging, we discovered that apical membranes undergo rapid expansion through a process reminiscent of membrane blebbing (Fig. 2a, panels B,C). Membrane blebs are plasma membrane protrusions caused by local disruption of the actomyosin cortex or its detachment from the plasma membrane12-16. Under cytoplasmic pressure, the membrane in such actomyosin-free regions inflates from a neck into a spherical protrusion. Depending on the context, blebs are either resolved by detachment (as seen in apoptosis), forward movement of the cell (during cell migration), or through recruitment and contraction of the actomyosin cortex on the inner side of the bleb (bleb retraction, as seen in cell division)16. In endothelial cells, we observed blebbing of the apical membrane during lumen expansion (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Video 1). These blebs however showed inverted polarity compared to previously described blebs, with the apical membrane protruding into the cell body. Hence, we propose to name this process “inverse membrane blebbing”. Following expansion, the inverse blebs either retracted (Fig. 2a, panel B and black arrowheads in Fig. 2b) or persisted, in particular as larger structures, leading to an expansion of the luminal compartment (Fig. 2a, panel C and white arrowheads in Fig. 2b). Interestingly, persisting blebs were only found at the tip of the growing lumen, therefore restricting lumen expansion to this region of the cell. In contrast, the blebs arising on the lateral sides of the lumen always retracted (Supplementary Video 1). Quantitative morphometric analysis of inverse blebs showed that their size, expansion time and speed, as well as retraction time and speed, are of the same order of magnitude than those of classical blebs12,15 (Supplementary Fig. 1a-e). Similar membrane dynamics were observed using a PLCδ-PH-RFP reporter for phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate (PIP2), an early apical determinant in epithelia17, confirming that inverse blebbing occurs specifically at the apical membrane of endothelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 1f and Supplementary Video 2).

Figure 2. Apical membrane undergoes inverse blebbing during lumen expansion.

a) Embryos with mosaic expression of EGFP-CAAX were imaged from 36 hpf. Arrow in B, retracting bleb. Arrowheads in C, bleb necks. Arrow in D, lumen collapse. Time is in hours:minutes:seconds. Scale bars are 10 μm (A,C,D) and 5 μm (B). Images are representative of 7 embryos analysed.

b) A kymograph was generated along the magenta line in a, panel A. X axis, time (t) in minutes. Y axis, distance (d) in μm. Black arrowheads, retracting blebs. White arrowheads, non-retracting blebs.

c) Multicellular sprouts were imaged in Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 embryos with mosaic expression of EGFP-CAAX from 32 hpf. Arrowheads, inverse blebs. Time is in hours:minutes:seconds. Scale bar is 10 μm. Images are representative of 4 embryos analysed.

d) Mouse retinas were collected at P6 and stained for ICAM-2, ZO-1 and Isolectin IB4. Isolectin IB4 staining was used to draw the cell outline (white dotted line). Arrow, constricted apical membrane. Arrowhead, lumen fragment. Scale bar is 10 μm.

e) The number of lumenised unicellular sprouts showing expanded, constricted or disconnected apical membrane was quantified in P6 mouse retinas stained for ICAM-2 and ZO-1 (n=57 sprouts from 9 retinas).

Inverse blebs were observed at the apical membrane of both unicellular (Fig. 2a) and multicellular (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Video 3) sprouts during lumen expansion. However, because endothelial cell junctions are highly dynamic6,18,19 and accumulate apical markers during lumenisation3 (Supplementary Video 2), we chose for clarity to focus our subsequent analysis on unicellular lumens where non-junctional apical membrane can clearly be distinguished.

In the mouse retina, stainings for ICAM-2 revealed the presence of two major lumen configurations in angiogenic sprouts where the apical membrane appeared either expanded (Fig. 2d, top panels, and Fig. 2e) or constricted (Fig. 2d, middle panels, and Fig. 2e), suggesting that a similar mechanism of apical membrane blebbing might take place during sprouting angiogenesis in mice.

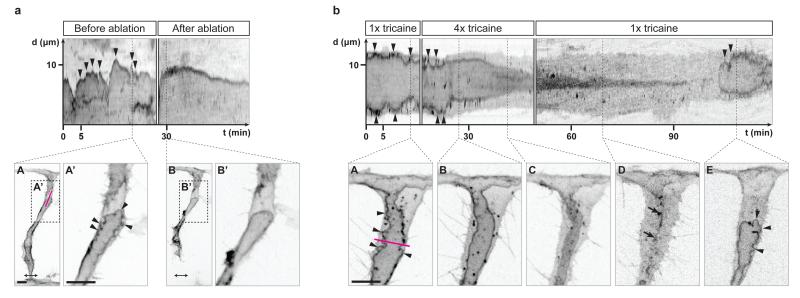

In order to assess whether inverse blebbing is driven by blood pressure, blood flow was stopped in single ISVs by laser ablating the connection of the sprouts to the dorsal aorta (Fig. 3a). The loss of blood flow resulted in an immediate stop of apical membrane blebbing and a gradual regression of the lumen (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Video 4). Similar results were obtained by treating embryos with 4x tricaine (Fig. 3b). Following 15-20 minutes of treatment, blood flow stopped (as assessed by the absence of circulating red blood cells) and blebs could no longer be observed at the apical membrane of lumenising cells (Fig. 3b, kymograph and panel B, and Supplementary Video 5). When returned to 1x tricaine, embryos recovered blood flow and re-expanded lumens by inverse blebbing (Fig. 3b, kymograph and panel E, and Supplementary Video 5). Together, these experiments suggest that the generation of inverse blebs depends on the positive pressure difference existing between the luminal and the cytoplasmic sides of the apical membrane.

Figure 3. Blood pressure drives inverse blebbing at the apical membrane of angiogenic sprouts.

a) Tg(fli1ep:EGFP-CAAX) embryos were imaged from 33 hpf. Ablation was performed at the base of the ISV to stop blood flow in the sprout (double-headed arrow, ablated region). A kymograph was generated along the magenta line in A to follow apical membrane dynamics before and after ablation. X axis, time (t) in minutes. Y axis, distance (d) in μm. Arrowheads, inverse blebs. Scale bars are 10 μm. Images are representative of 6 embryos analysed.

b) Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 embryos were imaged from 32 hpf in 1x tricaine, and then treated with 4x tricaine. Blood flow stopped approximately 15 minutes after the start of the treatment. After 30 minutes of treatment, embryos were washed with E3 buffer and placed back in 1x tricaine. A kymograph was generated along the magenta line in A to follow apical membrane dynamics. X axis, time (t) in minutes. Y axis, distance (d) in μm. Arrowheads, inverse blebs. Arrows, remnants of apical membrane. Scale bar is 10 μm. Images are representative of 5 embryos analysed.

Importantly, unlike previous reports suggesting that lumens form in sprouting ISVs through the fusion of intracellular vacuoles11,20,21, we could not observe the formation of any vacuolar structure in the cytoplasm of endothelial cells during phases of lumen expansion (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Video 1). Isolated lumen fragments were only seen arising from the local collapse of the lumen, and rapidly reconnected to the growing lumen (Fig. 2a, panel D and Supplementary Video 1). The fact that such collapse and regrowth events can be reproduced experimentally by stopping then restarting blood flow (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Video 5) suggests that these events occur during normal development following local variations in blood pressure. The observation of a low number of large disconnected lumen fragments in angiogenic sprouts in mouse retinas (Fig. 2d, bottom panels, and Fig. 2e) suggests that the apical membrane undergoes similar dynamics during mouse retina development.

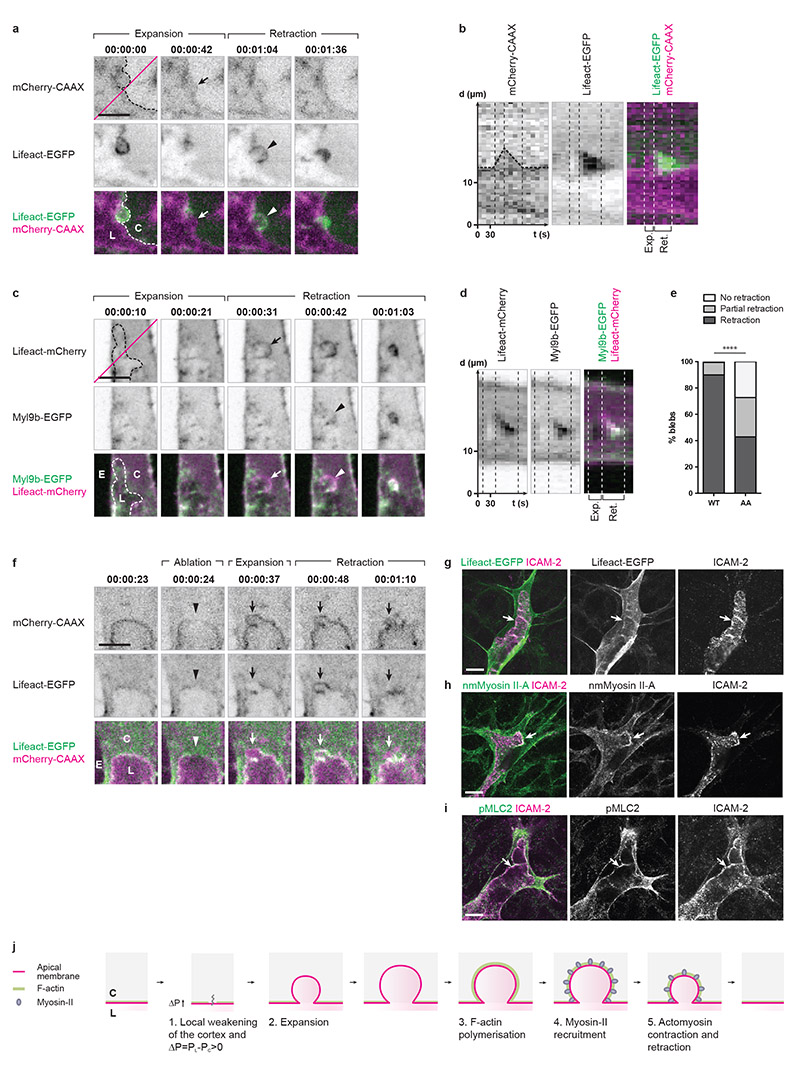

In order to identify the molecular mechanism underlying bleb retraction, fluorescent reporters for F-actin (Lifeact-EGFP and Lifeact-mCherry) and for the regulatory light chain of non-muscle Myosin-II (Myl9b-EGFP) were expressed in wild-type or Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 embryos. At 2 dpf, both reporters co-localised at the apical membrane in perfused ISVs (Supplementary Fig. 2a, panel B), indicating that an actomyosin cortex supports the apical membrane in small vessels. During lumen formation, blebs expanded devoid of any F-actin or Myosin-II (Fig. 4a-d, Supplementary Fig. 2b,c). In the event of retraction, F-actin polymerisation was observed at the apical membrane all around the bleb surface, from the initiation of retraction until its completion (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Video 6). Similarly, Myosin-II was recruited to the cytoplasmic surface of the bleb during retraction (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Fig. 2b,c). Co-expression of F-actin and Myosin-II reporters showed that Myosin-II is recruited to the apical membrane shortly after the initiation of F-actin polymerisation (Fig. 4c,d). Together, these data suggest that the recruitment and contraction of an actomyosin cortex at the apical membrane drives bleb retraction during lumen expansion (Fig. 4j).

Figure 4. Endothelial cells retract inverse blebs by recruiting and contracting actomyosin at the apical membrane.

a) Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 embryos with mosaic expression of Lifeact-EGFP were imaged from 35 hpf. Dotted line, apical membrane. Arrow, expanding apical membrane. Arrowhead, onset of F-actin polymerisation. C, cytoplasm. L, lumen. Time is in hours:minutes:seconds. Scale bar is 5 μm. Images are representative of 5 embryos analysed.

b) Kymograph generated along the magenta line in a. X axis, time (t) in seconds. Y axis, distance (d) in μm. Dotted line, apical membrane.

c) Embryos with mosaic expression of Myl9b-EGFP and Lifeact-mCherry were imaged from 35 hpf. Arrow, onset of F-actin polymerisation. Arrowhead, onset of Myosin-II recruitment. C, cytoplasm. E, extracellular space. L, lumen. Time is in hours:minutes:seconds. Scale bar is 5 μm. Images are representative of 5 embryos analysed.

d) Kymograph generated along the magenta line in c. X axis, time (t) in seconds. Y axis, distance (d) in μm.

e) Embryos with mosaic expression of Myl9b-EGFP or Myl9bAA-EGFP and LifeactmCherry were imaged from 34 hpf. Blebs growing on the lateral sides of expanding lumens were assessed for their ability to retract within the maximum time necessary for expansion and retraction (approximately 10 minutes, see Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). A multinomial log-linear model was used to test for association of bleb count in the different categories with the mutation status (WT: n=102 blebs from 5 cells; AA: n=161 blebs from 5 cells; data pooled from three independent experiments; p=2.1e-13; ****, p<0.0001).

f) Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherrys916;fli1ep:Lifeact-EGFP) embryos were imaged from 33 hpf. Laser ablation was performed along a line spanning the entire thickness of the apical membrane and its underlying cortex, at the tip of the growing lumen. Arrowhead, site of ablation. Arrow, inverse bleb. C, cytoplasm. E, extracellular space. L, lumen. Scale bar is 5 μm. Images are representative of 5 embryos analysed.

g-i) Lifeact-EGFP+/wt (g) and wild-type (h,i) mouse retinas were collected at P6 and stained for ICAM-2 (g-i), non muscle (nm) Myosin II-A (h), and phospho Myosin Light Chain 2 (pMLC2; i). Arrows show localisation of F-actin, nmMyosin II-A and pMLC2 at the apical membrane. Images correspond to single confocal planes. Scale bars are 10 μm.

j) Schematic illustration of inverse membrane blebbing. C, cytoplasm. L, lumen.

In order to test this hypothesis, we generated a non-phosphorylatable form of the Myosin-II regulatory light chain (Myl9bAA) previously shown to act as a dominant-negative22. In order to avoid any general and potentially deleterious effects during earlier development, the expression of Myl9bAA-EGFP was restricted to single endothelial cells and induced at the onset of lumen formation using the LexPR expression system23. Upon expression of Myl9bAA, we observed a significant difference in the frequency of bleb retraction compared to control cells expressing the wild-type form of Myl9b (Myl9b-EGFP), with a larger proportion of blebs showing no or partial retraction (Fig. 4e). These data therefore confirm that actomyosin contraction drives bleb retraction during lumen formation.

In order to test whether inverse membrane blebbing is, similarly to classical blebbing, the result of the local detachment of the membrane from its underlying cortex24, we performed local laser ablation of the cortex at the apical membrane of lumenising sprouts in Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherrys916;fli1ep:Lifeact-EGFP) embryos. By doing so, we could induce the expansion of inverse blebs at the apical membrane of lumenising vessels (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Video 7). This result suggests that local detachment of the cortex from the apical membrane, in conjunction with blood pressure, could be the trigger of inverse blebbing (Fig. 4j).

In mice, the imaging of retinas from Lifeact-EGFP+/wt pups and of wild-type retinas stained for non-muscle Myosin-IIA or phosphorylated Myosin Light Chain 2 (pMLC2) showed accumulation of actomyosin at the apical membrane in sprouting cells (Fig. 4g-i), suggesting that a similar recruitment and contraction of actomyosin could take place during lumen formation in angiogenic vessels in mice.

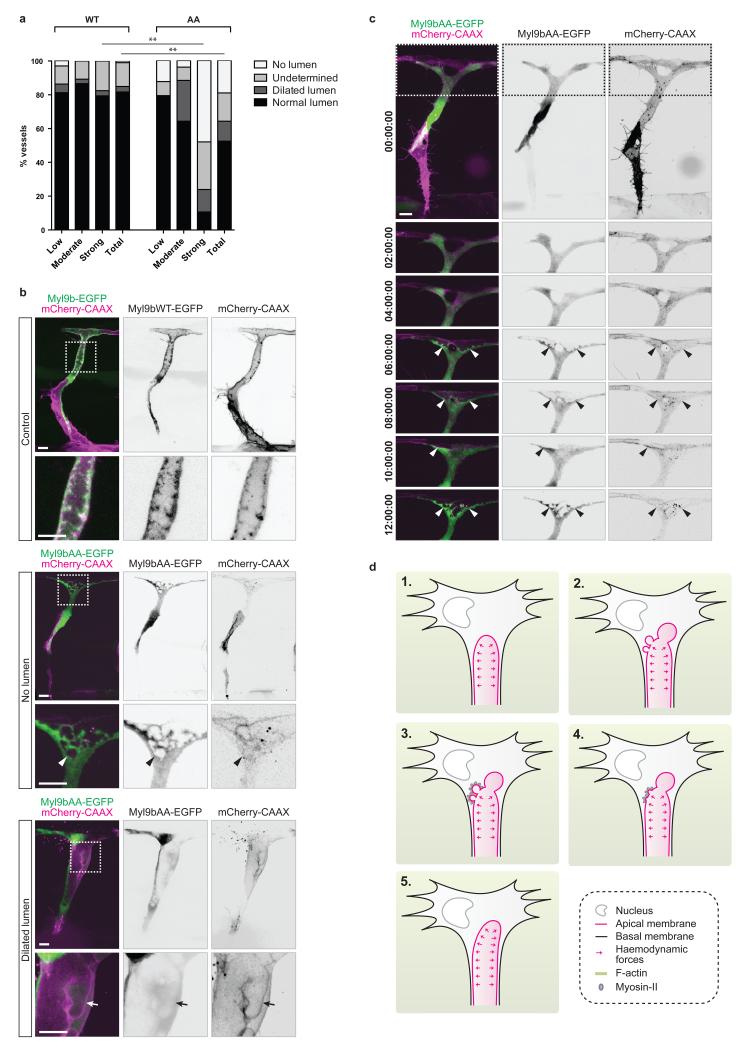

In order to assess whether apical membrane contractility is required for proper lumenisation, we inhibited actomyosin contraction by expressing Myl9bAA from 30 hpf and checked ISVs for the presence of a lumen at 2 dpf. Quantification of ISVs with Myl9bAA expression revealed a significant difference compared to control embryos (Fig. 5a), with a decrease in the proportion of cells showing normal lumens. Depending on their level of Myl9bAA expression, abnormal ISVs were either found to be unlumenised or displayed dilated lumens (Fig. 5a,b). Live imaging from 30 hpf showed that the absence of lumen was due to an inability of Myl9bAA-expressing cells to expand lumens (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Video 8).

Figure 5. Apical membrane contractility regulates lumen formation during sprouting angiogenesis.

a) Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 embryos with mosaic expression of Myl9b-EGFP or Myl9bAA-EGFP were analysed at 2 dpf. EGFP-positive ISVs were classified by eye into three categories according to their level of EGFP expression (low, moderate, strong) and screened for the presence of a lumen. A multinomial log-linear model was used to test for association of cell count in the different categories with the mutation status (WT: n=55 ISVs from 24 embryos; AA: n=31 ISVs from 9 embryos; data pooled from three independent experiments; p=0.30 (low), p=0.11 (moderate), p=0.0002 (high), p=0.00024 (total); **, p<0.01). EGFP-positive cells where the presence or absence of a lumen could not be appreciated were referenced as undetermined.

b) Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 embryos with mosaic expression of Myl9b-EGFP or Myl9bAA-EGFP were imaged at 2 dpf. Arrowhead, disconnected lumen fragment. Arrow, side lumen branch. Scale bars are 10 μm. Images are representative of 6 embryos analysed.

c) Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 embryos with mosaic expression of Myl9bAA-EGFP were imaged from 35 hpf. Arrowheads, lumen. Time is in hours:minutes:seconds. Scale bar is 10 μm. Images are representative of 3 embryos analysed.

d) Schematic model of lumen formation by inverse membrane blebbing during sprouting angiogenesis in vivo. Haemodynamic forces generate a positive pressure difference between the luminal and the cytoplasmic sides of the apical membrane (1). Consequently, inverse blebs expand along the apical membrane at sites of weak attachment of the cortex to the membrane (2). Following bleb expansion, F-actin polymerises and myosin-II is recruited at the apical membrane of growing blebs (3). Actomyosin contraction leads to bleb retraction (4), and selective bleb retraction ensures unidirectional lumen expansion (5).

In order to gain a deeper mechanistic understanding of the effects of Myl9bAA expression on the apical membrane dynamics, we performed fast imaging of both unlumenised and dilated cells at 2 dpf (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Videos 9 and 10). In both cases, the membrane dynamics was visibly affected by the expression of Myl9bAA. In unlumenised ISVs, lumen initially expanded into Myl9bAA-expressing cells but the apical membrane showed excessive and uncoordinated blebbing with frequent disconnections of blebs from the membrane (Fig. 5b, arrowhead, and Supplementary Video 9), therefore preventing lumen expansion. On the other hand, dilated, partially lumenised cells were unable to fully retract blebs growing on the lateral sides of the lumen (Fig. 4e and 5b and Supplementary Video 10), leading to the formation of side lumen branches (Fig. 5b, arrow, and Supplementary Video 10). Together, these data show that sprouting cells require actomyosin contraction at the apical membrane to control membrane deformations and ensure single, unidirectional lumen expansion in response to blood pressure (Fig. 5d).

Our present results challenge the previous idea that sprouting cells expand lumens independently of blood flow during angiogenesis in vivo through the generation and fusion of intracellular vacuoles. Although endothelial cells are able to generate lumens independently of blood flow in vitro25 and during vasculogenesis8-10, we show here that haemodynamic forces dynamically shape the apical membrane of single or groups of endothelial cells during angiogenesis in vivo to form and expand new lumenised vascular tubes. We find that this process relies on a tight balance between the forces applied on the membrane and the local contractile responses from the endothelial cells, as impairing this balance either way leads to lumen defects.

Our finding of inverse blebbing suggests that the process of blebbing, best studied in cell migration and cytokinesis, does not require a specific polarity, but is likely generally applicable to situations in which external versus internal pressure differences challenge the stability and elasticity of the actin cortex. In the case of endothelial cells, we describe a role for inverse blebbing in expanding the apical membrane under pressure while ensuring unidirectional expansion of a single lumen in angiogenic sprouts.

Our work more generally raises the question of the role of apical membrane contractility in the adaptation to varying haemodynamic environments, both during blood vessel morphogenesis, as connections form or remodel, and in pathological settings. Our present work and previous studies26,27 highlight the importance of balanced endothelial cell contractility in allowing the expansion and maintenance of endothelial lumens during blood vessel development. Future work will need to elucidate how the contractile properties of the apical membrane evolve as vessels mature and are exposed to higher levels of blood pressure and shear stress. The transition towards a multicellular organisation of endothelial tubes, and the observed changes in cell shape and junction stability imply adaptations in the structure and dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton. Understanding whether and how this plasticity of the apical membrane and its underlying cortex is challenged in pathological conditions, where vessels display altered perfusion and lack organised structure, has the potential to provide deeper insight into mechanisms of vascular adaptation and maladaptation.

Methods

Mouse care and procedures

The following mouse (Mus musculus) strains were used in this study: C57BL/6 and Lifeact-EGFP28. Animal procedures were performed in accordance with the United Kingdom’s Home Office Animal Act 1986 under the authority of project license PPL 80/2391. Animals were analysed regardless of sex.

Retina dissection, immunofluorescence staining and imaging

Eyes were collected at post-natal day 6 (P6) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for 1 hour at 4°C. Retinas were dissected, blocked in CBB buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 2% sheep serum, 0.01% sodium deoxycholate, 0.02% sodium azide) for 2 hours at 4°C and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies diluted in 1:1 PBS:CBB as indicated: ICAM-2 (1:400; BD Biosciences, Cat. #553326, lot #4213932), Phospho-Myosin Light Chain 2 (1:100; Cell Signalling, Cat. #3671), Non Muscle Myosin Heavy Chain II-A (1:100; Covance, Cat. #PRB-440P), ZO-1 (1:400; Life Technologies, Cat. #61-7300). Retinas were then washed three times for 10 minutes in PBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST), and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with secondary antibodies diluted in 1:1 PBS:CBB as indicated: goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor® 488 (1:1000: Life Technologies, Cat. #A-11008) and goat anti-rat Alexa Fluor® 555 (1:1000; Life Technologies, Cat. #A-21434). Retinas were finally washed three times for 10 minutes with PBST, fixed for 10 minutes at room temperature in 4% PFA, and mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, H-1000). When needed, Isolectin staining was performed by incubating the retinas overnight at 4°C with Isolectin GS-IB4 Alexa Fluor® 647 (Life Technologies, Cat. #I32450) diluted 1:400 in PBlec buffer (1% Tween-20, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM MnCl2 in PBS, pH 6.8). Samples were imaged with an upright Carl Zeiss LSM 780 microscope using an Alpha Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.46 NA oil objective.

Fish maintenance and stocks

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) were raised and staged as previously described29. The following transgenic lines were used: Tg(kdr-l:ras-Cherry)s916 30, Tg(fli1ep:EGFP)y1 31, Tg(fli1ep:PLCδ-PH-RFP), Tg(fli1ep:EGFP-CAAX) and Tg(fli1ep:Lifeact-EGFP)32.

Cloning, constructs and mosaic expression in zebrafish

All constructs were generated using the Tol2Kit33 and the Multisite Gateway system (Life Technologies). The coding sequence of EGFP-CAAX was provided in the Tol2Kit; the sequence coding for the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of PLC∂ was a gift from Banafshé Larijani (University of the Basque Country, Spain); Lifeact and Myl9b coding sequences were obtained from Riedl and colleagues28 and Source Bioscience (clone I0038156), respectively. Dominant-negative Myl9b (Myl9bAA) was generated by substituting Thr18 and Ser19 by Ala using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies). The fli1ep promoter (gift from Nathan Lawson, University of Massachusetts Medical School, USA) was used to drive endothelial expression of PLCδ-PH-RFP, EGFP-CAAX, Lifeact-EGFP and Lifeact-mCherry fusion constructs. For inducible expression of Myl9b-EGFP and Myl9bAA-EGFP, the coding sequence for the LexPR transactivator was placed under the fli1ep promoter, while Myl9b-EGFP and Myl9bAA-EGFP fusion constructs were placed under the LexA operator23. Tol2 transposase mRNA was transcribed from the pCS-TP plasmid34 using the SP6 mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kit (Life Technologies). Embryos were injected at the one-cell stage with 100 pg of Tol2 transposase mRNA and 40 pg of plasmid DNA. Embryos injected with the pTol2-fli1ep:LexPR and pTol2-lexOP:Myl9b-EGFP or pTol2-lexOP:Myl9bAA-EGFP plasmids were dechorionated and treated from 26 hpf with 20 μM Mifepristone (Sigma, M8046) in E3 buffer (5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl2, 0.33 mM MgSO4) to induce expression of the transgenes.

Live imaging

Embryos were dechorionated and anaesthetised with 0.16 mg/mL (1x) tricaine methanesulfonate (Sigma). Embryos were then mounted in 0.8% low melting point agarose (Life Technologies) and immersed in E3 buffer with 1x tricaine. When needed, heartbeat was inhibited by changing the medium for E3 buffer with 4x tricaine. Live imaging was performed on an inverted 3i Spinning Disk Confocal using a Zeiss C-Apochromat 63x/1.2 NA water immersion objective, on an upright 3i Spinning Disk Confocal using a Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.0 NA water dipping objective, and on an inverted Andor Revolution 500 Spinning Disk Confocal using a Nikon Plan Apo 60x/1.24 NA water immersion objective.

Laser ablation

Laser ablations were performed on an upright 3i Spinning Disk Confocal fitted with a Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.0 NA water dipping objective using an Ablate™ 532 nm pulse laser. Ablations were performed in single confocal planes along lines spanning the entire thickness of the structures to be ablated (cell body, or membrane and underlying cortex). Laser was applied for 10 ms at 10-20% laser power. Ablation of the structures of interest was obtained by performing sequential laser cuts using increasing laser power (starting from 10% with 1% increments, up to 20%) at 5 to 10-second intervals.

Image analysis

Images were analysed using the FiJi software35. Z-stacks were flattened by maximum intensity projection. XY drifts were corrected using the MultiStackReg plugin (B. Busse, NICHD). Fluorescence bleaching was corrected by Histogram Matching. Kymographs were generated using the MultipleKymograph plugin (J. Rietdorf and A. Seitz, EMBL). Contrast in all images was adjusted in Adobe Photoshop CS5.1 for visualisation purposes. All images are representative of the analysed data.

Statistical analysis

A multinomial log-linear model was used to test for association of bleb or cell count in different defined phenotypic categories with the cell mutation status (WT or AA). The null model was that count variation was only due to experimental batch.

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Zebrafish embryos were selected on the following pre-established criteria: normal morphology, beating heart, and presence of circulating red blood cells suggestive of blood flow. The experiments were not randomised. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiment and outcome assessment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Vascular Biology and Vascular Patterning Laboratories for helpful discussions. We thank the Cancer Research UK London Research Institute Animal and Fish Facilities, and the Aquatic Facilities at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine and Vesalius Research Center for animal care. We thank Thomas Surrey and Nicholas Cade for access to the inverted 3i Spinning Disk Confocal, and Pieter Vanden Berghe for access to the Andor Spinning Disk Confocal of the Cell Imaging Core facility at the Vesalius Research Center. We thank Gavin Kelly from the Francis Crick Institute (London, UK) for help with statistics. V.G. is funded by Cancer Research UK. L.-K.P. is funded by a HFSP Long-Term Fellowship. H.G. is funded by Cancer Research UK, the Lister Institute for Preventive Medicine, a European Research Council starting grant REshape [311719] and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH). Supported by the DZHK (German Center for Cardiovascular Research) and by the BMBF (German Ministry of Education and Research).

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Chen Q, et al. Haemodynamics-driven developmental pruning of brain vasculature in zebrafish. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochhan E, et al. Blood flow changes coincide with cellular rearrangements during blood vessel pruning in zebrafish embryos. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herwig L, et al. Distinct cellular mechanisms of blood vessel fusion in the zebrafish embryo. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1942–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenard A, et al. In vivo analysis reveals a highly stereotypic morphogenetic pathway of vascular anastomosis. Dev Cell. 2013;25:492–506. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell. 2011;146:873–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakobsson L, et al. Endothelial cells dynamically compete for the tip cell position during angiogenic sprouting. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:943–953. doi: 10.1038/ncb2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelton JC, Wright CE, Leitges M, Bautch VL. Multiple endothelial cells constitute the tip of developing blood vessels and polarize to promote lumen formation. Development. 2014;141:4121–4126. doi: 10.1242/dev.110296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin SW, Beis D, Mitchell T, Chen JN, Stainier DY. Cellular and molecular analyses of vascular tube and lumen formation in zebrafish. Development. 2005;132:5199–5209. doi: 10.1242/dev.02087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strilic B, et al. The molecular basis of vascular lumen formation in the developing mouse aorta. Dev Cell. 2009;17:505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charpentier MS, Tandon P, Trincot CE, Koutleva EK, Conlon FL. A distinct mechanism of vascular lumen formation in Xenopus requires EGFL7. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, et al. Moesin1 and Ve-cadherin are required in endothelial cells during in vivo tubulogenesis. Development. 2010;137:3119–3128. doi: 10.1242/dev.048785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham CC. Actin polymerization and intracellular solvent flow in cell surface blebbing. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1589–1599. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller H, Eggli P. Protrusive activity, cytoplasmic compartmentalization, and restriction rings in locomoting blebbing Walker carcinosarcoma cells are related to detachment of cortical actin from the plasma membrane. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1998;41:181–193. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)41:2<181::AID-CM8>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paluch E, Piel M, Prost J, Bornens M, Sykes C. Cortical actomyosin breakage triggers shape oscillations in cells and cell fragments. Biophys J. 2005;89:724–733. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.060590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charras GT, Coughlin M, Mitchison TJ, Mahadevan L. Life and times of a cellular bleb. Biophys J. 2008;94:1836–1853. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.113605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charras G, Paluch E. Blebs lead the way: how to migrate without lamellipodia. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:730–736. doi: 10.1038/nrm2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin-Belmonte F, et al. PTEN-mediated apical segregation of phosphoinositides controls epithelial morphogenesis through Cdc42. Cell. 2007;128:383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sauteur L, et al. Cdh5/VE-cadherin promotes endothelial cell interface elongation via cortical actin polymerization during angiogenic sprouting. Cell Rep. 2014;9:504–513. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phng LK, et al. Formin-mediated actin polymerization at endothelial junctions is required for vessel lumen formation and stabilization. Dev Cell. 2015;32:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamei M, et al. Endothelial tubes assemble from intracellular vacuoles in vivo. Nature. 2006;442:453–456. doi: 10.1038/nature04923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu JA, Castranova D, Pham VN, Weinstein BM. Single-cell analysis of endothelial morphogenesis in vivo. Development. 2015;142:2951–2961. doi: 10.1242/dev.123174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwasaki T, Murata-Hori M, Ishitobi S, Hosoya H. Diphosphorylated MRLC is required for organization of stress fibers in interphase cells and the contractile ring in dividing cells. Cell structure and function. 2001;26:677–683. doi: 10.1247/csf.26.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emelyanov A, Parinov S. Mifepristone-inducible LexPR system to drive and control gene expression in transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2008;320:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tinevez JY, et al. Role of cortical tension in bleb growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18581–18586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903353106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis GE, Camarillo CW. An alpha 2 beta 1 integrin-dependent pinocytic mechanism involving intracellular vacuole formation and coalescence regulates capillary lumen and tube formation in three-dimensional collagen matrix. Exp Cell Res. 1996;224:39–51. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu K, et al. Blood vessel tubulogenesis requires Rasip1 regulation of GTPase signaling. Dev Cell. 2011;20:526–539. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin M, et al. PP2A regulatory subunit Balpha controls endothelial contractility and vessel lumen integrity via regulation of HDAC7. EMBO J. 2013;32:2491–2503. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods References

- 28.Riedl J, et al. Lifeact mice for studying F-actin dynamics. Nat Methods. 2010;7:168–169. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0310-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hogan BM, et al. Ccbe1 is required for embryonic lymphangiogenesis and venous sprouting. Nat Genet. 2009;41:396–398. doi: 10.1038/ng.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawson ND, Weinstein BM. In vivo imaging of embryonic vascular development using transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2002;248:307–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phng LK, Stanchi F, Gerhardt H. Filopodia are dispensable for endothelial tip cell guidance. Development. 2013;140:4031–4040. doi: 10.1242/dev.097352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwan KM, et al. The Tol2kit: a multisite gateway-based construction kit for Tol2 transposon transgenesis constructs. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3088–3099. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawakami K, et al. A transposon-mediated gene trap approach identifies developmentally regulated genes in zebrafish. Dev Cell. 2004;7:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.