Abstract

The fossil record provides good evidence for the minimum ages of important events in the diversification and geographic spread of Asteridae, with earliest examples extending back to the Turonian stage of the Late Cretaceous (~89 Ma). Some of the fossil identifications accepted in previous considerations of asterid phylogeny do not stand up to careful scrutiny. Nevertheless, among major clades of asterids, there is good evidence for a range of useful anchor points. Here we provide a synopsis of fossil occurrences that we consider as reliable representatives of modern Asterid families and genera. In addition, we provide new examples documented by fossil dispersed pollen investigated by both light and scanning electron microscopy studies including representatives of Loranthaceae, Amaranthaceae, Cornaceae (incl. Nyssa L., Mastixia Blume, Diplopanax Hand.-Mazz.), Sapotaceae, Ebenaceae, Ericaceae, Icacinaceae, Oleaceae, Asteraceae, Araliaceae, Adoxaceae and Caprifoliaceae from Paleogene sites in Greenland, western North America, and central Europe, and of Lamiaceae and Asteraceae from the middle to late Miocene northeastern China. We emphasize that dispersed pollen, taken along with megafossil and mesofossil data, continue to fill gaps in our knowledge of the paleobotanical record.

Keywords: Angiosperms, Asteridae, Cenozoic, Cretaceous, paleobotany, palynology

In the past few decades our concept of what constitutes the Asteridae and the phylogenetic relationships among its constituents have evolved faster than the plants themselves. With the aid of abundant molecular sequence data, the relationships, both within and outside this major clade of angiosperms, have become increasingly well resolved (e.g., Soltis et al., 2011). The fossil record of Asterids is not as dense as that for other major groups, e.g., the Rosids, but there are many significant Cretaceous and Cenozoic fossils representing a range of Asterid clades.

The ages of Asterid clades have been inferred previously by fossil-calibrated molecular clock approaches (Bremer et al., 2004), and by direct inference from the position of the oldest fossils of component clades (Magallón et al., 1999; Crepet et al., 2004; Martínez-Millán, 2010). Martínez-Millán (2010) compared numerical estimates for the ages of Asterids and their major clades derived from molecular approaches with those derived directly from fossils, and commented on the rather large discrepancies. The minimum age molecular estimates inferred by modified molecular clock approaches calibrated with selected points from the fossil record generally exceeded by many millions of years (13 to 58.5 million years depending on the clade; Table 1 in Martínez-Millán, 2010) those inferred by direct observation of available fossils in relation to currently held phylogenetic topologies. Based on available fossils, she concluded that the Asteridae date back at least to the Turonian stage of the Late Cretaceous (89.3 Ma) and that its four main clades were already represented in the fossil record by the late Santonian-early Campanian (83.5 Ma). It remains debatable whether the substantial gap between the still older origination times of these clades inferred from molecular estimates, and their appearances in the fossil record are due to analytical problems or failure to recover and recognize older fossils. Of course, the quality of these estimates depends in part on the reliability of fossils used in analyses, both the age of the fossils, and their proper systematic placement.

In assessing the published fossil record of asterids and choosing which fossils to use from the literature for assessing the minimum age of specific asterid clades, Martínez-Millán (2010) applied a “filtering system” that led her to accept or reject published records based on completeness of the original author's presentation of the paleobotanical species. Three primary criteria were used to assess the acceptability of each fossil: 1) inclusion of the fossil in a phylogenetic analysis, 2) discussion of key characters that place the fossil in a group, 3) list of key characters that place the fossil in the group. Reports that fulfilled one or more of these were accepted as representing reliable records, while those that did not meet these standards were provisionally rejected (Martínez-Millán, 2010: 88). We agree in part with this method, yet it does not deal explicitly with the fossils and their characteristics, but rather with the presentation style of the authors who identified those fossils.

Martínez-Millán (2010) tabulated fossil reports of various asterid clades, emphasizing the geologically earlier records for each clade, indicating the organ represented, the age and geography of the fossil and whether or not the report was accepted for calibrating nodes of the asterid phylogeny. These tables, including 261 records, are a helpful guide to relevant literature. Use of the strict filter criteria mentioned above resulted in some decisions with which we cannot agree, however. For example, Marcgravia L. and Norantea Aubl. pollen from the mid Oligocene of Puerto Rico (Graham & Jarzen, 1969), and various reports of the paleoecologically important pollen records of the mangrove, Pelliciera Planch. & Triana (e.g., Graham & Jarzen, 1969; Graham, 1977, 1999) were blanketly rejected. It is true that the authors did not include these fossils in a phylogenetic analysis, and did not provide a thorough discussion of key characters that support identification to the indicated genera. The morphology of these grains (illustrated for example in Graham, 1977) is sufficiently distinctive, however, that the authors apparently did not deem it necessary to defend their assignment of the fossils which they documented by light microscopy. On the other hand, some of the records accepted in the same treatment by Martínez-Millán (2010) strain credulity.

“Symmetrical, narrow ovate to elliptic shape, acute apex, entire and slightly undulated margin, brochidodromous venation, presence of intersecondary veins and percurrent tertiaries are the diagnostic features of the present fossil which are commonly seen in the modern leaves of Diospyros Linn. of the family Ebenaceae.” (Prasad & Pradhan, 1998: 107). Presentation of this list of similarities resulted in an automatic decision of “acceptable,” in Martínez-Millán's assessment; however, the single fragmentary specimen illustrated by the authors shows no characters unique to Diospyros L.; indeed the above-quoted list of “diagnostic” characters for this entire-margined, pinnately veined leaf lacking its petiole and unknown in epidermal anatomy, could apply equally well to numerous other genera in a wide array of angiosperm families not even confined to Asteridae.

The same can be said of the record of Ardisia Sw.: “the important morphological features of the present [fragmentary, entire-margined] fossil such as attenuate apex, entire margin, eucamptodromous venation, presence of intersecondary veins and the curvature of secondary veins near the margin strongly indicate its close affinity with the extant leaves of Ardisia simplicifolia” (Prasad & Pradhan, 1998: 106). Similarly, an entire-margined pinnately veined leaf lacking its petiole was accepted as Sapotaceae by Martínez-Millán (2010) based on the claim by Mehrotra (2000, p 234): “The diagnostic characters of the fossil are: elliptic shape, rounded base, entire margin, eucamptodromous venation, moderate to wide acute angle of divergence of secondary veins, stout primary vein and presence of intersecondary veins. These features indicate the affinities of the fossil leaf with that of Chrysophyllum L. of Sapotaceae.” We do not feel that these particular records are convincing because the identifications are based only on similarities, without indicating that these similarities are unique, and/or whether they include any synapomorphies. Despite some of these disagreements over some of the records accepted and rejected, the timing and appearance of major asterid clades inferred by Martínez-Millán (2010) remain as reasonable estimates.

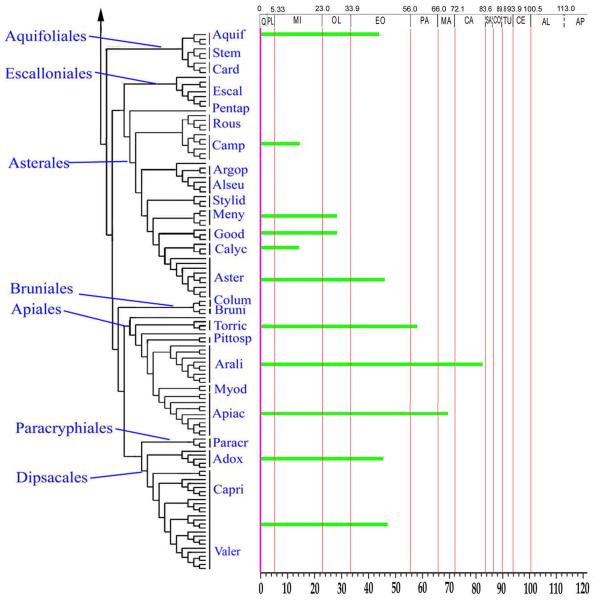

In their book reviewing the fossil record of all angiosperm orders, Friis et al. (2011) devoted a chapter to Asteridae--a review that had been conducted independently from that by Martínez-Millán (2010). Together, these references provide a good overview of our current understanding of the fossil record of Asterids. Here, we augment these reviews with additional informative examples, and point out some prior misinterpretations. As a frame of reference, we use the phylogenetic topology provided by Soltis et al. (2011) in their study of angiosperm phylogeny based on 17 genes and 640 species. That phylogeny, abridged with emphasis on Asterids, is shown here in Fig. 1. We consider examples from the fossil record in the sequence of Ericales, Cornales, Lamiids and Campanulids. It would be desirable if fossil occurrences were preserved as whole plants with characters of all organs intact. This is never the case, however, so we rely on the disaggregated remains that happen to be preserved as fossils. In some instances, whole flowers are preserved in excellent detail including the perianth, gynoecium with ovules and placentation intact and stamens with in situ pollen preserved, yet we do not know the corresponding leaves or wood. In other cases we may have only leaves, only dispersed pollen, or just the wood. In some cases these individual organs or tissues are highly distinctive, with character combinations that appear to be unique to particular clades. The record of fossil flowers and fruits (Friis et al., 2011) is particularly important, especially for recognizing some of the earliest members of the asterids. The dispersed pollen record is also very useful, and deserves more attention than it has received in previous reviews. In this article we review fossil examples, including pollen, flowers, leaves, wood, fruits and seeds, and show how they are spread across the phylogeny as we currently understand it. Most are gleaned from the literature, but we also introduce new examples, especially of dispersed fossil pollen.

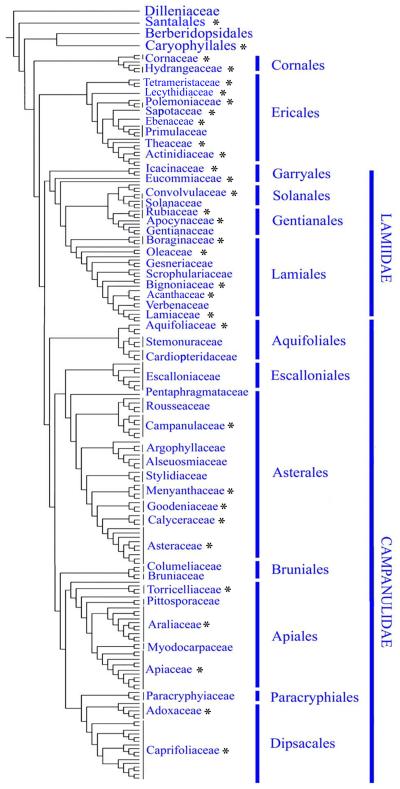

Figure 1.

Phylogeny of asterids excerpted from the 17-gene analysis of angiosperms (Soltis et al., 2011). Asterisks indicate those families for which fossil remains are known.

The identifications of fossil pollen grains to modern genera commonly found in the literature are often based exclusively on transmitted light microscopy (LM), without the resolution of informative fine details that can be provided by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). In some instances, the morphological characters resolvable by light microscopy are sufficient to provide confident identification, e.g., Alnus Mill., Carya Nutt., Fagus L., Liquidambar L., Quercus L., Ulmus L. and other highly distinctive grains. But in many cases, pollen grains of unrelated taxa can be nearly indistinguishable unless SEM details are available. In the present work, we rely on the combined information provided by both light and scanning electron microscopy of the same grains.

Materials and Methods

In addition to citing from the literature in this review, we include in this article new documentation of fossil pollen grains from selected Late Cretaceous, Paleocene, Eocene and Miocene localities in the northern hemisphere. Sedimentary rock samples were processed and pollen grains were isolated from the residue using standard techniques (e.g., Grímsson et al., 2008, 2011), and individual grains were removed and manipulated for imaging first by light microscopy (LM) and then by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), using the single grain technique (e.g., Zetter, 1989; Ferguson et al., 2007). This method documents more characters than would be available from light microscopy or SEM alone, and insures that the observed morphological features are from the same individual fossil pollen grain. For investigating the likely affinities of these pollen relative to extant taxa, it has been important to compare with as many modern genera as possible. Broad systematic treatments of the palynology of particular regions (e.g., Li et al., 2009, Miyoshi et al., 2011), as well as the specialty literature on pollen of particular families or genera, cited later in this article, have been very useful.

There are eight sources for the fossil pollen grains presented herein by combined SEM and LM: the Cretaceous (early Campanian) of Elk Basin, Wyoming, the early Paleocene of Agatdalen, West Greenland, the late Paleocene of Almont, North Dakota, the middle Eocene of Hareøen, West Greenland, and Princeton, British Columbia, and Stolzenbach, Germany, the late Eocene of Profen, Germany, and the Miocene of Heilongjiang Province, China. The geographic and geologic source information for these sites are provided below:

Elk Basin, Wyoming, USA (early Campanian)

The sedimentary samples originate from the Eagle Formation of Elk Basin, a valley bordering the Wyoming and Montana state line. Elk Basin comprises several outcrops with both marine and terrestrial, Upper Cretaceous to lower Cenozoic, sedimentary sequences. The Eagle Formation is locally divided into two units: The lower Virgelle Sandstone Member and the Upper Eagle Beds. The upper beds are composed of alternating sandstones, carbonaceous mudstones, siltstones, shales, clays, and lignites (Hicks, 1993; Van Boskirk, 1998). All of the plant macrofossils described by Van Boskirk (1998) and the sediment samples used for this palynological study originate from the upper part of the Upper Eagle Beds, from below the 1 m-thick bentonite layer positioned ca 10 m below the top of the formation. The Eagle Formation is succeeded by a regionally extensive ashfall bed, named the Ardmore Bentonite, which comprises the basal unit of the Claggett Shale Formation (cf. Hicks, 1993). Biostratigraphic and magnetostratigraphic studies of the Elk Basin by Hicks (1993) suggest that the lowest part of the Upper Eagle Beds coincides with the Scaphites hippocrepis III ammonite zone, and the ca. upper two thirds (composing the fossilized plant material) of the beds lie within the Baculites sp. (smooth; early) zone. According to Obradovich (1993) and Gradstein et al. (1995) the base of the Baculites sp. (smooth; early) zone starts at ca. 81 Ma and continued for a period of ca 0.5 million years. A similar, but slightly older, age for the plant fossiliferous sediments was obtained by isotopic data from the previously mentioned bentonite layer positioned close to the top of the Eagle Formation, dated to 81.13 ± 0.5 Ma (Hicks, 1993). This suggests that the plant bearing unit of the Eagle Formation is early Campanian in age and approx. 82--81 Ma.

Agatdalen, West Greenland (early Paleocene)

The fossil pollen from this locality originate from phosphoritic nodules of Agatdalen Valley in the central part of the Nuussuaq Peninsula, West Greenland. Early Paleocene sedimentary rocks in the northern part of the valley have been partly assigned to the Agatdal Formation (Koch, 1963; Dam et al., 2009). The type locality/section of the Agatdal Formation is the Store Profil or the Big Section in Turritellakløft Gorge (see Dam et al., 2009). The phosphoritic nodules containing the fossil pollen were collected between the years 1948--1964 at the Store Profil type section from sediments of the Agatdal Formation. The stratigraphic position of the Agatdal Formation (Koch, 1963; Dam et al., 2009), its exceptionally rich fossil marine fauna (e.g., Bendix-Almgreen, 1969; Hansen, 1970; Rosenkrantz, 1970; Szczechura, 1971; Floris, 1972; Perch-Nielsen, 1973; Hansen, 1976; Kollmann & Peel, 1983; Collins & Wienberg Rasmussen, 1992; Petersen & Vedelsby, 2000), as well as correlations with radiometric dates of overlying formations (see Storey et al., 1998; Dam et al., 2009) show that the Agatdal Formation is upper Danian, between 64--62 Ma.

Almont, North Dakota (late Paleocene)

Silicified shales of the Sentinel Butte Formation, exposed about 9.5 km northwest of New Salem, North Dakota, USA, have yielded well preserved leaves, fruits, seeds, flowers (Crane et al., 1990) and dispersed pollen (Zetter et al., 2011). The lacustrine deposit is considered to be late Paleocene (Tiffanian 3) based on pollen and regional stratigraphic correlations (Kihm & Hartman, 1991).

Princeton Chert (middle Eocene, early to middle Lutetian)

The outcrop is located along the east bank of the Similkameen River, ca 8.4 km south of the town Princeton, British Columbia, Canada. The silicified and fossil rich sedimentary rocks that comprise the Princeton Chert beds belong to the uppermost part of the Allenby Formation that is part of the Princeton Basin. The basin is a northerly trending trough comprising various volcanic and sedimentary rock units of Eocene age that form the Princeton Group. Jurassic and Triassic rocks make up most of the basement and outline/margins for the basin (McMechan, 1983; Read, 1987, 2000). The Princeton Group is divided into two formations. The lower Cedar Formation is mostly of volcanic origin, and the upper Allenby Formation is constructed of various sedimentary rock units. The lowest two major units of the Allenby Formation are the Sunday Creek Conglomerate and the Hardwick Sandstone. These units are overlain by the Vermilion Bluffs Shale, the Summer Creek Sandstone, and the Ashnola Shale (McMechan, 1983; Read, 1987, 2000). The Ashnola Shale includes in its uppermost part the Princeton Chert beds (Read, 2000; Mustoe, 2011). The samples used for this study originate from chert-bed 43, from the uppermost quarter of the Princeton Chert sequence. The exact age of the Princeton Chert beds is difficult to pinpoint, but studies based on fossil mammals, fish and plants (e.g., Russell, 1935; Gazin, 1953; Rouse & Srivastava, 1970; Wilson, 1977, 1982; Cevallos-Ferriz et al., 1991; Pigg & Stockey, 1996) suggest an Eocene age. Radiometric dating indicate that most of the volcanic rocks of the Cedar Formation and the sedimentary rocks of the lower to middle part of the Allenby Formation are 53--48 Ma, and are therefore early Eocene in age. The uppermost part of the Allenby Formation is dated to ca 46 Ma, suggesting that the Princeton Chert beds are of middle Eocene age (early to middle Lutetian).

HAreøen, West Greenland (middle Eocene, late Lutetian to early Bartonian)

Fossil pollen from Hareøen originate from sediments of the middle Eocene Aamaruutissaa Member of the Hareøen Formation, on the island of Hareøen, West Greenland (Grímsson et al., 2014, 2015). Plant macrofossils from Hareøen described by Heer (1868--1883) and Nathorst (1885) originate from the same member. The fossil pollen derived from a resinite-rich coal bed in the intrabasaltic Aamaruutissaa Member, which forms the lower part of the Hareøen Formation (Hald, 1976, 1977). The Aamaruutissaa Member overlies the early Eocene Kanissut Member. The Kanissut Member belongs to the Naqerloq Formation, which is dated to 56--54 Ma (Storey et al., 1998; Dam et al., 2009). The Aamaruutissaa Member is overlain by the late Eocene Talerua Member (Hald, 1976, 1977). The Talerua Member lava flows have been dated radiometrically to 38.8 ±0.5 Ma (Schmidt et al., 2005) suggesting that the underlying plant fossil bearing sediments of the Aamaruutissaa Member are slightly older. Pollen analyses suggest a late Lutetian to early Bartonian (42--40 Ma) age for the plant bearing sediments (Grímsson et al., 2014, 2015).

Profen, Sachsen, Germany (middle Eocene)

The Profen locality is an open-cast coalmine in Sachsen-Anhalt State of central Germany. The sediments are part of the Weißelster Basin that composes middle Eocene to Pliocene strata. The geology of the Profen locality has been outlined by Pälchen and Walter (2011), indicating that the oldest part of the Profen sediments, from which our palynological samples originate, are of middle Eocene (Bartonian) age. The palynoflora from the Eocene sediments of Profen was described using light microscopy by Krutzsch and Lenk (1973). The palynoflora is clearly of Eocene age, with most palynomorphs indicative of middle Eocene, but also some elements normally suggesting an early late Eocene age (Krutzsch & Lenk, 1973; R. Zetter, pers. obs.).

Stolzenbach, Hessen, Germany (middle Eocene)

The Stolzenbach locality is an underground coal mine positioned just south of Kassel in the Borkener brown-coal area. The geological settings and the plant macrofossil content of the sedimentary succession within the coalmine was originally described by Oschkinis and Gregor (1992). The Eocene sediments have yielded numerous plant macrofossils, fossil insects and vertebrate remains, as well as an extremely rich palynoflora (e.g., Tobien, 1961; Hottenrott et al., 2010; Gregor & Oschkinis, 2013; Gregor et al., 2013). The palynological samples were taken from thin clay units within the lignites of the underground coal mine (Hottenrott et al., 2010). The vertebrate fauna described from the succession (Tobien, 1961; Gregor et al., 2013) and the composition of the microflora (R. Zetter, pers. obs.) suggest a middle Eocene age for the sediments containing the fossils.

Beipaizi, northeast China (middle to late Miocene)

This pollen sample was collected from the Daotaiqiao Formation located at Beipaizi, about 4 km north of Sifangtai Village, Huanan County of the Heilongjiang Province, northeast China (Grímsson et al., 2012). The geological settings and sedimentary succession from where the sample was collected have been described in detail by Liu et al. (1995, 1996) and Leng (1997, 2000a, 2000b). The sample originates from finely laminated dark-gray claystone, which is rich in fossil plants and skeletons of freshwater fish and insects. The claystone belongs to the lower part of a sedimentary succession composing the Daotiaqiao Formation. The age of the Daotaiqiao Formation has been assigned to the late middle Miocene to early late Miocene (approximately 12--11 Ma), by correlating well-dated fossil macro- and microfloras in East Asia (Liu et al., 1995, 1996; Liu, 1998; Leng, 1997, 2000a, 2000b), and by the correlation of vertebrate faunas, including various fossil freshwater fish (Chang et al., 1996) and fossils of terrestrial mammals (Qi, 1992).

Results

Lower Asteridae

The Dilleniales are poorly documented in the fossil record. We are not aware of any substantiated records of this order. Leaves attributed to Tetracera L. and Dillenia L. from the late Eocene of Oregon (Chaney & Sanborn, 1933) do resemble leaves of some extant species of those genera, but are also difficult to distinguish from those of Fagaceae and Ticodendraceae.

Santalales

This order is relatively well represented in the fossil record, based on pollen of Loranthaceae, with examples of extant genera recognizable back to the early Eocene in the Southern Hemisphere (Macphail et al., 2012) and middle Eocene of the Northern Hemisphere (Zetter et al., 2014). Loranthaceous pollen has distinctive triangular oblate grains that are typically concave sided and syncolpate, with distinctive variation in ornamentation and aperture configuration among genera (e.g., Feuer & Kuijt, 1980, 1985). Combined LM and SEM study of dispersed fossil grains indicate that the family was widespread by the middle Eocene, with examples conforming to modern genera known from the middle Eocene of West Greenland (Fig. 2 A--C) and central Europe (Fig. 2 D--F).

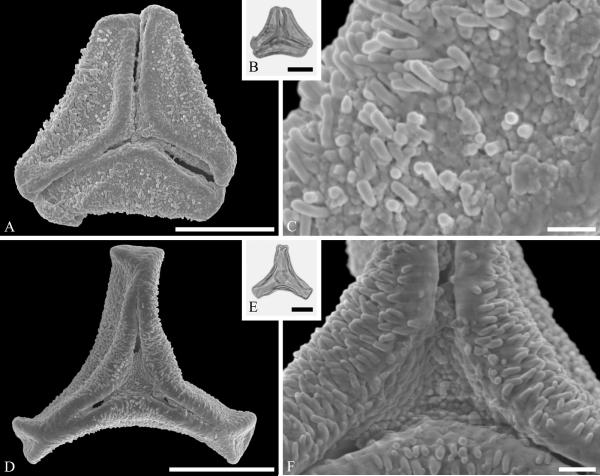

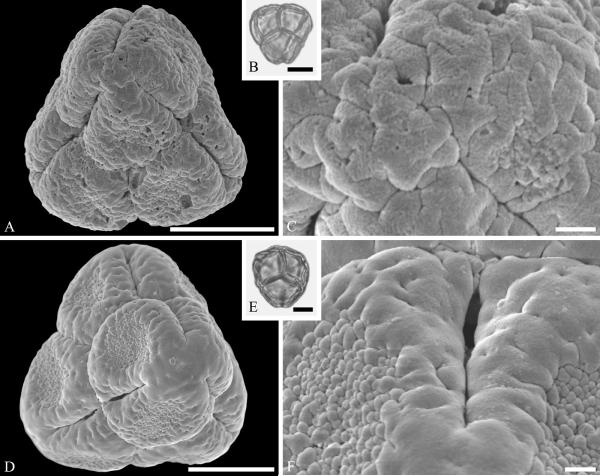

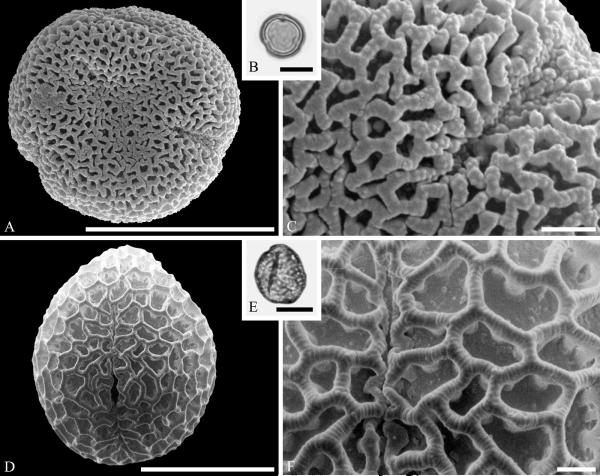

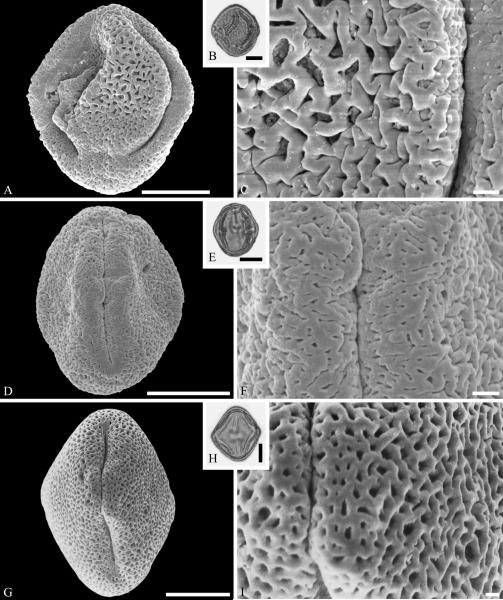

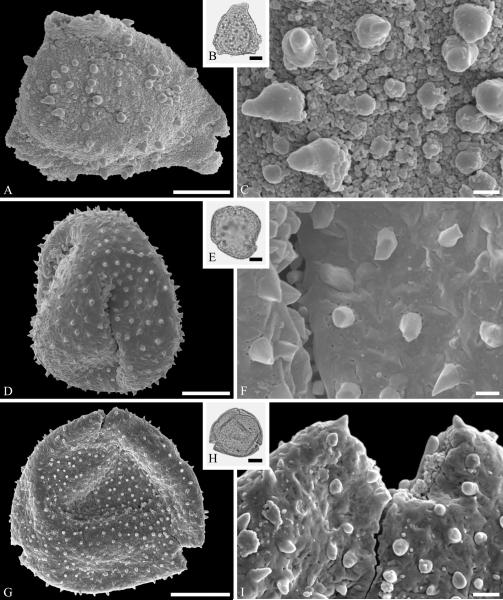

Figure 2.

Pollen of Loranthaceae pollen from the middle Eocene of Greenland and Germany. A--C. Hareøen, central West Greenland, gen. et spec. indet. showing prominent triradiate syncolpus. ---A. SEM micrograph, polar view. ---B. LM micrograph of same grain, polar view. ---C. Closeup showing verrucate and bacculate ornamentation in area of mesocolpium. D--F. Profen, central Germany, gen. et spec. indet. ---D. SEM micrograph, polar view. ---E. LM micrograph, polar view. ---F. Close-up showing sculpturing elements in polar area and mesocolpium. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B, D, E and 1 μm in C and F.

Caryophyllales

This order is represented mainly by fossils in the Amaranthaceae and Polygonaceae. The Amaranthaceae lack much of a megafossil record but are well represented by dispersed fossil pollen. Pollen of Amaranthaceae (incl. Chenopodiaceae) are distinctive nearly spheroidal, pantoporate grains with numerous annulate pores. Although nearly psilate by light microscopy, SEM reveals an echinate to microechinate and perforate sculpturing (Nowicke, 1994). Fossil grains of this kind, commonly referred to the genus Chenopodipollis Krutzsch, among other names, is known from the Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation (Nichols, 2002) and from the Paleocene of North Dakota North America (Fig. 3A--C) (Zetter et al., 2011), the late Eocene of North America (Bouchal, 2013) and commonly known in the fossil record through the Miocene (reviewed for example by Muller, 1981), but the assignment to individual extant genera is not possible because they overlap in morphology. Caryophylloflora paleogenica G. J. Jord. & Macphail, an inflorescence containing periporate pollen in situ was recovered from the middle to late Eocene of northeastern Tasmania (Jordan & Macphail, 2003). In general, however, the megafossil record of Caryophyllales remains poorly documented.

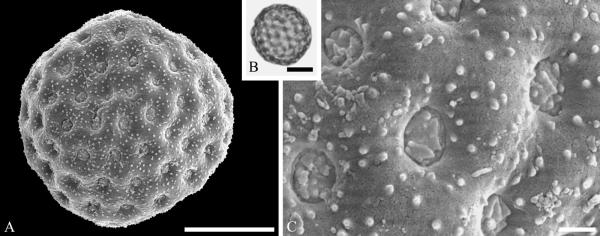

Figure 3.

Pollen of Amaranthaceae from the late Paleocene of Almont, North Dakota, USA. A--C. Amaranthaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---A. SEM micrograph of globose, multiforate grain. ---B. LM micrograph of same grain. ---C. Close-up showing surface sculpture of pollen and apertures with membrane. Scale bars 10 μm in A and B, 1 μm in C.

Winged fruits of Polygonaceae have been identified from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian: Polygonocarpum johnsonii Manch. & O’Leary) and late Paleocene (Polygonocarpum curtisii Manch. & O’leary and Podopteris antiqua Manch. & O’Leary) of North Dakota (Manchester & O'Leary, 2010). McIver and Basinger (1993) also identified as Polygonaceae the distinctive leaves of Paranymphaea crassifolia (Newberry) Berry, common in the lower Paleocene of North America.

Friis et al. (2011) consider the pollen resembling Bougainvillea Comm. ex Juss. of the Nyctaginaceae from the late Campanian of Sakhalin, Russia (Takahashi, 1997) to be a significant early record for this clade. Pollen of Nyctaginaceae is also reported with SEM as well as light microscopy from the “Eocene” of Argentina (Zetter et al., 1999), but the correct age (?Eocene to ?Miocene) of these sediments has been questioned (e.g., Zamaloa, 2000; García-Massini et al., 2004). The tricolpate grains are distinctive by their aperture membranes consisting of masses of partly fused angular microechini and having a nexine that is much thinner than the sexine, and a tectum with spaced microechini (Zetter et al., 1999).

Cornales

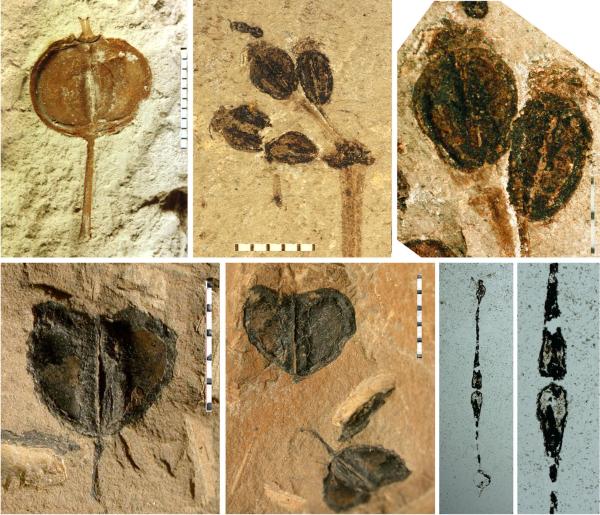

The Cornales are well represented in the fossil record, with Hydrangeaceae, Cornaceae (incl. Nyssa L., Mastixia Blume), and Davidiaceae all extending back at least to the Campanian (~72 Ma) based on well-preserved character-rich fruits. The oldest example of Hydrangeaceae is the charcoalified flower (and fruit?) known as Tylerianthus crossmanensis Gandolfo, Nixon & Crepet (1998) from the Turonian of New Jersey. The extant genus Hydrangea L. is readily recognized in the fossil record based on compressed showy sterile flowers and fruits from the early to middle Eocene (Fig. 4A, B) (Manchester, 1994; Mustoe, 2002) and Oligocene (Meyer & Manchester, 1997). Permineralized Eocene Hydrangea fruits from Oregon were shown to contain winged seeds, a feature found in this genus today only in the Asian species, H. anomala D. Don (Manchester, 1994).

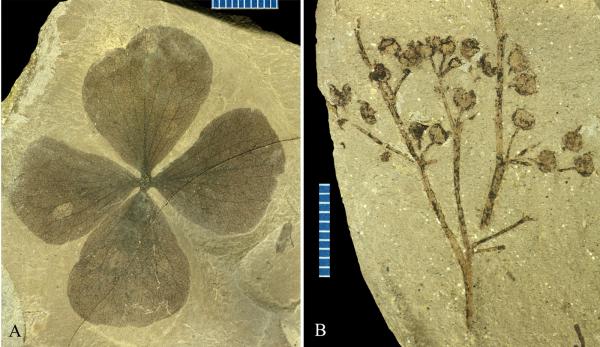

Figure 4.

Hydrangea knowltonii flower and fruiting remains from the middle Eocene Clarno Formation of West Branch Creek Oregon. ---A. Sterile showy perianth, UF 230-19187. ---B. Paniculate infructescence showing fruits with persistent apically divergent styles, UF230-18155.

Cornus L. is recognized by its distinctive leaves with eucamptodromous secondary veins and calcified T-shaped trichomes. Leaves showing these diagnostic characters have been confirmed from the Paleocene of Russia and western North America (Manchester et al., 2009b). Fruits of Cornus are also readily recognizable by a combination of characters including epigyny, two or more locules with dorsal germination valves, endocarp composed mostly of isodiametric cells, and transeptal placental bundles (Eyde, 1988). Those with internal cavities, distinctive of Cornus subg. Cornus, have been described in detail from the Paleocene of North America, and early Eocene of England (Manchester et al., 2010). Dispersed pollen of Cornus is also distinctive, being echinate, tricolporate with H-shaped endoapertures (thinning of the endexine with lamellation) (Ferguson, 1977, 1978). Such pollen is confirmed based on SEM studies from Paleocene (Zetter et al., 2011) and younger strata, and has the potential to be traced back to the Cretaceous.

The oldest evidence for Nyssoideae is Hironoia fusiformis Takahashi, Crane & Manchester (2002), a fruit from the early Coniacian of Japan. The fruits were thick-walled, and composed mainly of fibers, with three or four locules, each containing one pendulous seed and opening by a single dorsal valve fruit, and preserved persistent epigynous tepals, and a single narrow style. Absence of an axial vascular strand is a distinctive feature that it shares with most extant Cornaceae. The presence of fibers, rather than isodiametric sclereids, is a feature distinguishing this from Cornus, and indicating similarity with Nyssoideae and Mastixioideae (Takahashi et al., 2002).

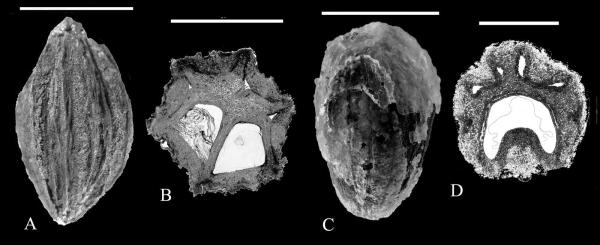

Subsequent records of Cornales include Davidia Baill. from the late Campanian of Alberta, Canada, based on permineralized fruits (Fig. 5A, B) (Serbet et al., 2004). These early fruits of Davidia conform to the modern genus in having multiple, radially arranged single-seeded locules, fibrous endocarp construction, and elongate dorsal germination valves. They closely resemble the modern genus morphologically and anatomically, but differ from the modern species of Davidia by their smaller size and fewer locules (5--6 vs 6--9). Other features of the plant, e.g., the leaves and inflorescence structure, remain unknown, so it is not proven whether this represents the stem or crown of Davidia. By the Paleocene, however, Davidia is clearly recognizable on the basis of well preserved infructescences, showing the scars of showy bracts, plus fruits and foliage fitting well to the modern genus. Only the smaller size of the fruit, and lack of a median rib over each locule, distinguishes the Paleocene species D. antiqua (Newberry) Manchester, from the modern D. involucrata Baill. (Manchester, 2002). Although Davidia is endemic to China today, it was present in the Paleocene of Asia, and in the Paleocene to late Eocene (Manchester & McIntosh, 2007) of western North America.

Figure 5.

Cornalean fruits from the Late Cretaceous (late Campanian) of Drumheller, Alberta. ---A, B. Davidia Baill. sp. ---C, D. Nyssa L. sp. Tyrrell Museum. Scale bars are 5 mm in A, C, and 3 mm in B, D.

Fruits conforming morphologically and anatomically to Nyssa have also been identified from the Campanian of Alberta, Canada, the same locality yielding the oldest Davidia fruits mentioned above. They are trilocular with single-seeded locules that are c-shaped in cross section, having dorsal, apically positioned germination valves (Fig. 5C, D). Although not formally named yet (Serbet & Manchester, in progress), the fruits conform to a kind that is common in the Paleogene, formerly called Palaeonyssa Reid & Chandler. Eyde (1997: 105) noted that the distinction between Palaeonyssa, having 3--4 locules, from Nyssa, “is probably not justified because plurilocular fruits also occur in extant species of Nyssa, particularly in N. talamancana of Costa Rica and Panama.”

Extinct members of Nyssoideae include the widespread North American Paleocene plant, known by its infructescences and fruits as Amersinia Manch., Crane & Golovn. This plant bore trilocular (occasionally tetralocular) fruits in heads with epigynous disk, and lacked a central vascular strand (strands are scattered through the septa, as in Davidia). Each locule bore a single seed, and had a dorsal germination valve in the apical half. The associated leaves, Beringiaphyllum cupanioides (Newberry) Manch., Crane & Golovn., had long petioles and laminae somewhat similar to Davidia, but with teeth more rounded and usually confined to the upper portion of the lamina. The small number of locules (3 and rarely 4), however, is more similar to Camptotheca Decne. and Nyssa. The epigynous disk of Amersinia relates it to other modern Cornales, except Davidia, which in modern species (and apparently in fossils) lacks this feature. Amersinia Manch., Crane & Golovn and Beringiaphyllum Manch., Crane & Golovn are found in the Paleocene of eastern Asia as well as North America (Manchester et al., 1999). Browniea serrata (Newberry) Manch. & Hickey represents another extinct genus of the Paleocene, in western North America that was apparently closely related to modern Camptotheca. It is known from associated infructescences, fruits, flowers with pollen in situ, and leaves (Manchester & Hickey, 2007).

Curtisia Aiton, the sole member of Curtisiaceae, also belongs to the Cornales and conforms to the Cornales in the presence of single seeded locules with dorsal germination valves, but is unusual in having a central vascular bundle between its four locules (Eyde, 1988). Although it lives today in southern Africa, the genus is known based on well-preserved fruits from the early Eocene London Clay flora (Manchester et al., 2007).

Noferinia fusicarpa Lupia, Herendeen & Keller, from the Santonian of Georgia, USA, bore dense headlike infructescences of numerous fusiform fruits, each with an epigynous, perianth, and 3 to rarely 4 connate carpels, with recurved style arms (Lupia et al., 2002). The fruits lack an axial bundle and are more slender than those of Amersinia; the presence/absence of germination valves was not documented. Pollen from the stamens is similar to that of Nyssa, but with a more coarsely reticulate tectum.

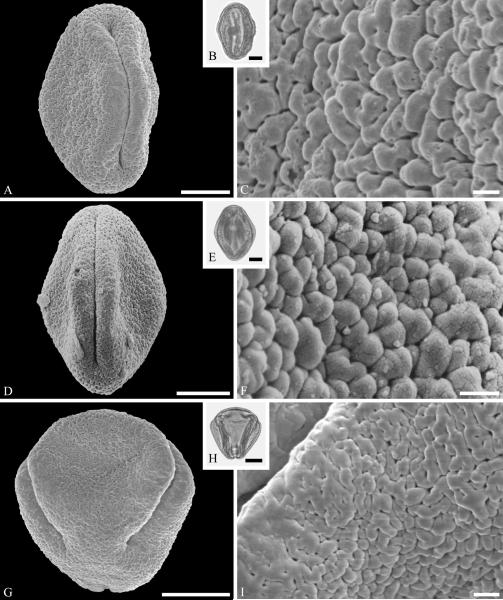

Although Mastixioideae contain only two genera today, Mastixia (now distributed from East Asia to Malesia) and Diplopanax Hand.-Mazz. (SW China and Vietnam), this subfamily was diverse and common in western North America and Europe based on fossil fruits. Knobloch and Mai (1986) recognized five species of extinct mastixioids from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Walbeck and Eisleben, Germany. These show full-length dorsal germination valves, one of the diagnostic features of Mastixioideae, distinct from Nyssoideae. Detailed anatomical data are not yet documented for these species, but they do appear, on the basis of available characters, to be appropriately assigned to Mastixioideae. Mastixioid fruits are also known in the Paleocene of North Dakota (Manchester & Pigg, in progress), and in the Eocene of western North America (Tiffney & Haggard, 1996; Stockey et al.,1998), England and Germany (Mai, 1993). These include the two modern genera, as well as extinct genera with novel combinations of fruit characters. Dispersed pollen of Mastixioideae are recognizable by the combination of H-shaped thinnings of endoaperture, shared with Cornus, in combination with a non-echinate, microverrucate and perforate tectum. Examples are illustrated here from the early Paleocene of Agatdalen, central West Greenland (Fig. 6A--C) and the middle Eocene of Stolzenbach, Germany (Fig. 6D--F).

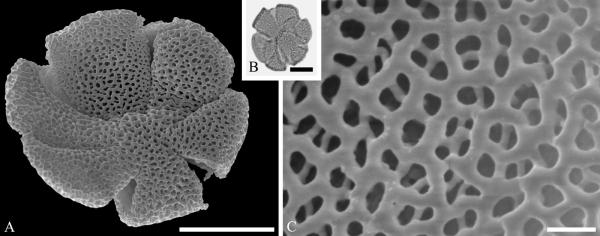

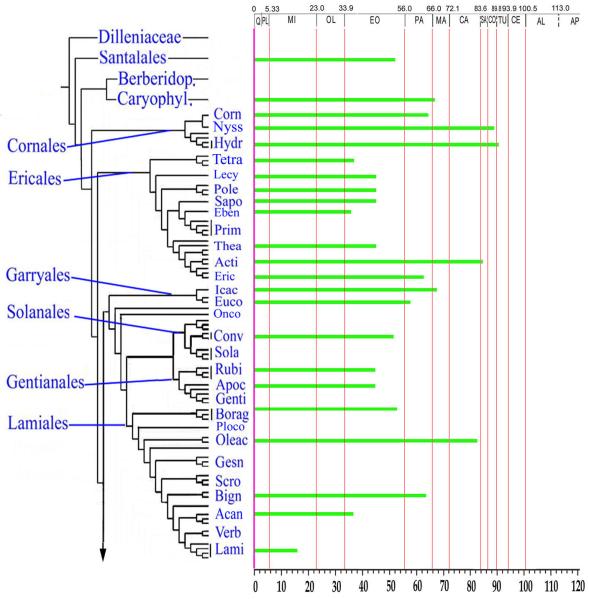

Figure 6.

Cornalean pollen from the early Paleocene of Greenland (A--C) and the middle Eocene of Germany (D--F) and middle Eocene of Greenland (G--I). A--C. Mastixia Blume sp. from Agatdalen, central West Greenland. ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph of the same grain showing tricolporate morphology, equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing sculpturing in area of mesocolpium. D--F. Mastixia sp. from Stolzenbach, Germany. ---D. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---E. LM micrograph of same grain showing tricolporate morphology, equatorial view. ---F. Close-up showing sculpturing in area of mesocolpium. G--I. Nyssa L. sp. oblate pollen grain from Hareøen, central West Greenland. ---G. SEM micrograph, oblique view. ---H. LM micrograph of same grain, oblique view. ---I. Close-up showing sculpturing along colpus and in area of mesocolpium. Scale bars are 10 μm in A, B, D, E, G, H and 1 μm in C, F, I.

Alangium Lam. is well recognizable on the basis of fossil fruits (Eyde et al., 1969; Manchester, 1994) and wood (Scott & Wheeler, 1982) back to the Eocene. The oldest examples are fruits are from the Early Eocene London Clay (Reid & Chandler, 1933). Fossil pollen also has been widely recognized (Morley, 1982; Martin et al., 1996).

Ericales

Among Ericales, the Actinidiaceae, Ericaceae, Polemoniaceae, Sapotaceae, Styracaceae, Symplocaceae and Theaceae are well established on the basis of middle Eocene (~47 Ma) reproductive structures, including fruits, seeds and/or pollen. Flowers of several extinct genera, e.g., Palaeoenkianthus Nixon & Crepet (1993) and Raritaniflora Crepet, Nixon & Daghlian (2013) from New Jersey extend this clade back to Turonian (~92 Ma). To the extensive listing of ericalean fruits, seeds, wood, etc. in table 4 of Martínez-Millán (2010) we can add some significant records.

The Marcgraviaceae, together with Tetrameristaceae and Balsaminaceae, are currently seen to form a clade that is as sister to the rest of the Ericales (Soltis et al., 2011). Fossil records for Marcgravia have been reported based on pollen but by light microscopy alone, and it is not clear that their morphology is unique to the family. In the Tetrameristaceae (currently circumscribed to include Pellicieraceae), the mangrove genus, Pelliciera, has been identified in the Neotropical fossil record from the middle Eocene onward (Graham, 1977), based on rather distinctive dispersed pollen grains named Lanagiopollis crassa (Van der Hammen & Wymstra) Frederiksen. Frederiksen (1988) recognized L. crassa from the middle Eocene Tallahatta Formation of the southeastern US, and considered it likely to be Pelliciera, but commented on the difficulty of distinguishing pollen of this genus from the unrelated extant genus, Alangium: “Although fossil pollen of Alangium and Pelliceria can probably be distinguished, it does not seem worthwhile to have separate form-genera for the two types” (Frederiksen, 1988: 56). It would be desirable to investigate these grains by SEM as well as light microscopy, but most records were deemed acceptable by Muller (1981) and Graham (1977).

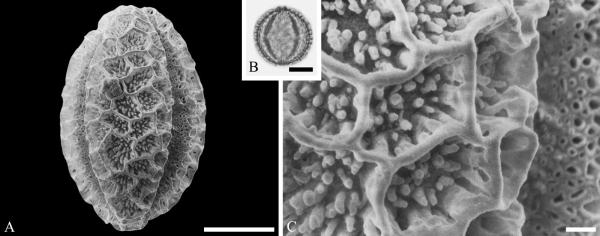

The fossil record of Lecythidiaceae includes species related to Barringtonia J. R. Forst. & G. Forst. In addition to records based on woods from the latest Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) Deccan Traps of India accepted by Martínez-Millán (2010), we recognize pollen of Barringtonia morphology from the middle Eocene of Stolzenbach, Germany (Fig. 7A--C). Pollen of this genus is distinctive and readily identifiable because of a unique reticulate type of sculpturing around the apertures (e.g., Muller, 1973). The Polemoniaceae are known from a single quite complete fossil specimen of a plant with the roots, leaves and fruits intact from the middle Eocene of Utah (Lott et al., 1998). The small stature and divided leaves of the single available specimen suggest that it was a small shrub perhaps adapted to subarid conditions.

Figure 7.

Lecythidiaceae pollen from the middle Eocene of Stolzenbach, Germany. A--C. Barringtonia J. R. Forst. & G. Forst. sp. ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing microreticulate, perforate sculpturing around colpus. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B, and 1 μm in C.

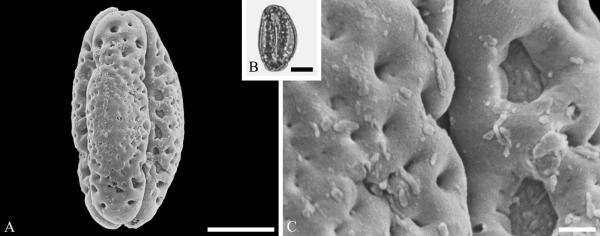

Pollen of Sapotaceae is sufficiently distinctive (e.g., Harley, 1991) to be recognized as dispersed fossil grains. Examples of the tri-, tetra-, and sometimes stephano(5)-colporate grains are known from the Paleocene to the Miocene (e.g., Muller, 1981). However, the distinctive microornamentation necessary to confirm the fossil pollen identifications requires SEM as well as light microscopy (e.g., Kmenta & Zetter, 2013). We document an example from the Eocene of Stolzenbach, Germany (Fig. 8A—F). In addition, twigs with attached leaves and fruits exhibiting caulofructy, a common feature of the family, are known the late Oligocene of Rott, Germany: Sideroxylon salicites (Weber) Weyland (Weyland, 1937; Winterscheid, 2006). Identification of the leaf attributed to Chrysophyllum by Mehrotra (2000), from the Paleocene of India, already discussed above, does not seem convincing. Sapotaceae have seeds with a broad and distinctive hilar scar, that would be easy to recognize in the fossil record, but there are very few records of them. The fossil genus Saportispermum Reid & Chandler, accommodating seeds with morphology characteristic of the family, has been recognized from the early Eocene London Clay (Reid & Chandler, 1933) and middle Eocene of Germany (Collinson et al., 2012). One of the fossil seed types attributed to this family by Manchester (1994), as “Bumelia? globosa” from the middle Eocene of Oregon, was later transferred to the unrelated genus Sargentodoxa Rehder & E. H. Wilson (Manchester, 1999).

Figure 8.

Ericales. Sapotaceae and Ebenaceae pollen. A--F. Sapotaceae pollen from the middle Eocene of Stolzenbach, Germany. A--C. Sapotaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph of the same grain showing tricolporate morphology, equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing microverrucate and perforate sculpturing of mesocolpium, and microverrucate and microechinate colpus membrane. D--F. Another sapotaceous grain. ---D. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---E. LM micrograph of the same grain, equatorial view. ---F. Close-up showing fossulate and granulate sculpturing of mesocolpium. G--I. Diospyros pollen from the late Eocene of Florissant, Colorado, USA. ---G. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---H. LM micrograph of the same grain showing apparently psilate exine and elongate colpi. ---I. Close-up showing fine ornamentation pattern. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B, D, E, G, H and 1 μm in C, F, I.

Ebenaceae are difficult to confirm in the fossil record from leaves because they lack distinctive features, but the pollen has a distinctively organized microrugulate sculpturing, visible by SEM, that facilitate recognition of the genus Diospyros, e.g., from the late Eocene of Florissant, Colorado (Fig. 8G--I). Austrodiospyros cryptostoma Basinger & Christophel (1985) was founded on flowers with in situ pollen from late Eocene of Anglesea, Victoria, Australia.

Actinidiaceae are a small family today but well represented in the fossil record, with flowers and fruits of Parasaurauia allonensis Keller, Herendeen & Crane (1996), and Glandulocalyx Schönenberger, Balthazar, Takahashi, Xiao, Crane & Herendeen (2012) from the Late Cretaceous (late Santonian) of Georgia and seeds of Actinidia Lindl. from the Eocene of Oregon (Manchester, 1994) and Miocene sites of Europe (reviewed by Martínez-Millán, 2010). Paradinandra suecica Schönenberger & Friis is a flower from the late Santonian--early Campanian Åsen, Scania, North Sweden with affinities to Actinidiaceae/Theaceae (Schönenberger & Friis, 2001). A seed named Saurauia antiqua Knobloch & Mai (1986) from the late Turonian to Maastrichtian, Germany has also been accepted as a representative of this family (Friis et al, 2011).

Diapensiaceae are rare in the fossil record. Actinocalyx bohrii Friis (1985) is a flower of Late Cretaceous (late Santonian--early Campanian) age from Åsen, Scania, southern Sweden that has been accepted as Diapensiaceae (Martínez-Millán, 2010).

The Theaceae are exemplified by fruits, winged seeds and associated leaves from the Eocene of Tennessee (Grote, 1989, 1992). Fossil leaves called Ternstroemites E. W. Berry, from the same strata, show the theoid tooth type characteristic for Ericales; because these leaves are found in the same sediments as unequivocal fruits and seeds of Theaceae, we think their assignment to Theaceae is probably correct.

Styracaceae

Although Rehderodendron Hu is restricted to Southeast Asia today, it was common in the Eocene to Miocene of Europe. Especially well preserved examples are known from the Tertiary of Europe (Mai, 1970; Manchester et al., 2009a) including fruits of R. stonei (Reid & Chandler) Mai from the London Clay (Mai, 1970; Manchester et al., 2009a) and Sabals d' Anjou, France (Vaudois-Mieja, 1983), and R. ehrenbergii (Kirchheimer) Mai in the Miocene of Germany (Mai, 1970; Manchester et al., 2009a). The fruits are distinctive by the presence of three central locules surrounded by lacunose endocarp. Epigynous winged fruits with the intramarginal vein diagnostic of Halesia J. Ellis ex L. are known from Pliocene of Europe (Tralau, 1965b) but have not been confirmed yet from older strata. Styrax L. is well represented by distinctive seeds especially in the European Miocene (Kirchheimer, 1957).

Symplocaceae have an excellent fossil record of endocarps, reviewed by Mai and Martinetto (2006), Manchester and Fritsch (2014) and Fritsch et al. (2015). The oldest known occurrences are from the early Eocene of London Clay.

Ericaceae

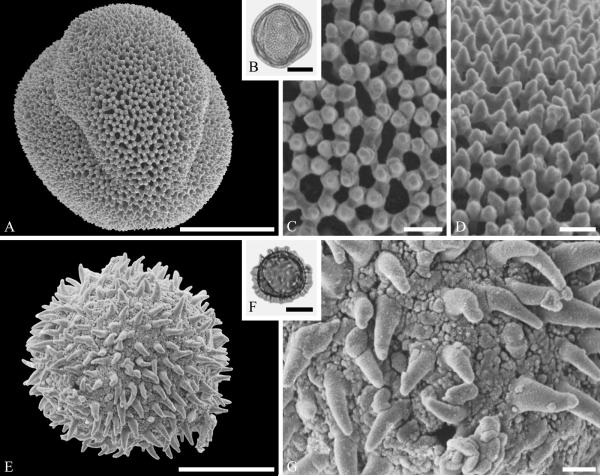

Pollen of Ericaceae in permanent tetrads is easily recognized from localities in Paleocene and younger strata. Here we illustrate examples from the early Paleocene of Agatdalen, central West Greenland (Fig. 9A--C), and the middle Eocene of Profen, central Germany (Fig. 9D--F). Similar tetrads, as old as middle Eocene (Geiseltal, Germany) can be identified to Rhododendron L. based on the presence of viscin threads (Zetter & Hesse, 1996). These pollen records augment the reports of dispersed seeds of Rhododendron from the Paleocene of England (Collinson & Crane, 1978) and late Eocene of California (Wang & Tiffney, 2001).

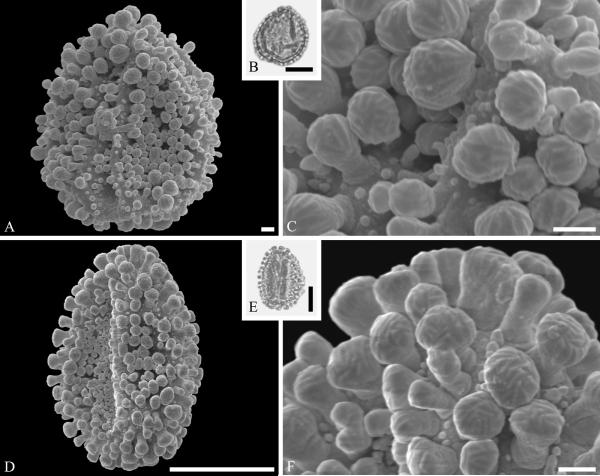

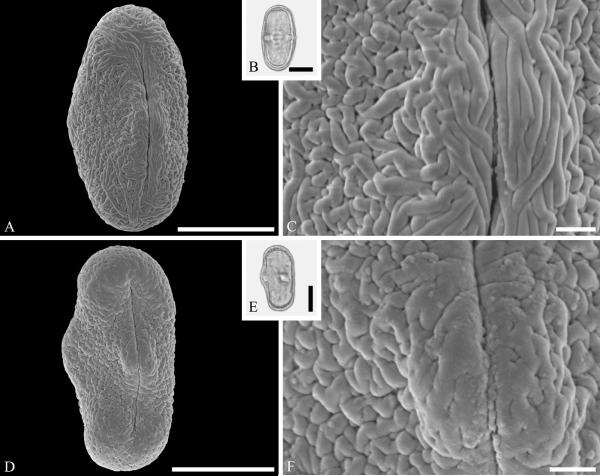

Figure 9.

Ericaceae pollen from the early Paleocene of Agatdalen, central West Greenland (A--C), and the middle Eocene of Profen, central Germany (D--F). A--C. Ericaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---A. SEM micrograph, tetrad in oblique view. ---B. LM micrograph of the same tetrad in equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing fossulate and microstriate sculpturing in polar area. D--F. Ericaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---D. SEM micrograph, tetrad in polar view. ---E. LM micrograph of the same tetrad in equatorial view. ---F. Close-up showing microverrucate sculpturing in central mesocolpium, and fossulate, perforate and granulate sculpturing around colpi. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B, D, E, and 1 μm C, F.

Clethraceae

Pollen of Clethraceae have often been described from the palynological record using LM only (e.g., Muller, 1981), and therefore many of the so-called Clethraceae pollen really belong to other families, e.g., Rosaceae, Cyrillaceae, and Actinidiaceae. Until now no convincing evidence based on combined LM and SEM studies exists showing the presence of “true” Clethraceae pollen.

Basal Lamiids and Garryales

Among basal Lamiids, the Icacinaceae are particularly well represented in the fossil record. Early records based on endocarps extend back to the Late Cretaceous (e.g., Knobloch & Mai, 1986) but these have not been fully confirmed with anatomical details. Endocarps placed in the modern genus Phytocrene Wall. by Scott and Barghoorn (1957) from the Turonian of New York are anatomically distinct from that modern genus, and probably are not Icacinaceae (Stull et al., 2012). By the Paleocene (~58 Ma), the family is known from a diversity of well preserved and distinctive fruits resembling extant Icacinaceae (Pigg et al., 2008) and even the extant tribe Phytocreneae (Stull et al., 2012). Both extinct and extant genera of Icacinaceae are recognizable on the basis of fruits in the middle Eocene (Manchester, 1999; Rankin et al., 2008; Collinson et al., 2012).

Pollen unique to Platea Blume, distinguished by tricolporate grains with a distinctive geometric pattern of crotonoid clavate (reticulum cristatum) ornamentation (Fig. 7A--C) is known from the Paleocene of North America (Lobreau-Callen & Srivastava, 1974) and Greenland (Fig. 10 A--D). Lobreau-Callen and Srivastava (1974) documented the similarity with extant grains with comparative electron microscopy. Grains of Platea are very distinctive, even in the context of other Icacinaceae, which mostly have echinate ornamentation and colpate to porate apertures. A widespread Paleogene echinate and triporate pollen type, referred to by the misleading generic name Compositoipollenites rhizophorus (R. Potonié) R. Potonié, is believed to represent Icacinaceae (detailed SEM illustrations here in Fig. 10 E-G), and in Hofmann et al., 2011). These resemble the echinate type of pollen characteristic today of tribe Phytocreneae and some other representatives of the family (Lobreau-Callen, 1973), although a comprehensive comparative investigation remains to be done with attention to other families that also share echinate pollen.

Figure 10.

Icacinaceae pollen from the early Paleocene of Agatdalen (A--D), central West Greenland, and middle Eocene of Stolzenbach, Germany (E-G). A--D. Platea Blume sp. ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph of same grain, equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing reticulum cristatum sculpture type in central mesocolpium. ---D. Close-up showing reticulum cristatum sculpture type in polar area. E--G. Icacinaceae gen. et spec. indet. (Compositoipollenites rhizophorus) ---E. SEM micrograph, polar view. ---F. LM micrograph, polar view. ---G. Close-up showing porus and surrounding echinate sculpturing. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B, E, F and 1 μm in C, D, G..

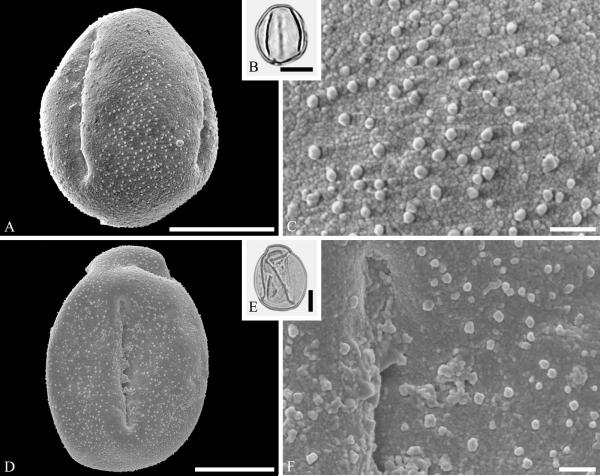

Eucommiaceae are confirmed by their diagnostic pollen in Paleocene (Fig. 11A--C) (Zetter et al., 2011) and younger strata, e.g., the middle Eocene of West Greenland (Fig. 11D--F). The tricolporate pollen is distinctive by its psilate surface (as seen in light microscopy) with evenly distributed microechini as seen by SEM. Fruits of Eucommia Oliv. occur in the early and middle Eocene in Asia and North America. The North American occurrences range from Oligocene of southern Mexico (Magallón-Puebla & Cevallos-Ferriz, 1994) to the middle latitudes, e.g., Tennessee, Montana, Oregon (Call & Dilcher, 1997), and in Miocene and younger strata of Europe and Asia (reviewed by Manchester et al., 2009a).

Figure 11.

Eucommia Oliv. pollen from the late Paleocene of Almont, North Dakota, USA (A--C), and from the middle Eocene of Hareøen, central West Greenland (D--F). A--C. Eucommia sp. ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph of the same grain, equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing granulate and microechinate sculpturing of mesocolpium. D--F. Eucommia sp. ---D. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---E. LM micrograph of the same grain, equatorial view. ---F. Close-up showing granulate and microechinate sculpturing of mesocolpium, and truncate polar end of colpus with microechinate colpus membrane. Scale bars 10 mm in A, B, D, E, and 1 μm in C, F.

Solanales

The Solanales are conspicuous in lacking well-documented fossils, but new evidence of a Physalis-like fruit from the Eocene of Argentina has emerged (Wilf, 2013). The fossil record of Solanaceae was reviewed recently and many fossils once attributed to this family have been discredited (Millán & Crepet, 2014).

Martin (2001) surveyed modern pollen of the Convolvulaceae as a basis for identifying fossil representatives based primarily on light microscopy. She considered that the large tricolpate pollen species known as Perfotricolpites digitatus González Guzmán is similar to extant Convolvulus L. and Operculina Silva Manso among other extant genera; and that a small tricolpate grain known as Tricolpites trioblatus Mildenh. & Pocknall may be related to extant Wilsonia R. Br. and possibly Cressa L. Both of these pollen types occur in the late Eocene of southern Australia. Other examples include the pantoporate species Calystegiapollis microechinatus Sal.-Cheb. (similar to Calystegia R. Br.) and Xenostegia tridentata (L.) D. F. Austin & Staples from the early Eocene of Africa, and Perfotricolpites digitatus from the middle-Eocene of Brazil. Wilsonia, now endemic to Australia, was in New Zealand in the mid to late Miocene (Martin, 2001).

In addition to the records mentioned above, we document the convolvulaceous genus Merremia Dennst. ex Endl., from the middle Eocene of Stolzenbach, Germany (Fig. 12 A--C). This genus, recognized previously from the middle Oligocene San Sebastián Puerto Rico (Graham & Jarzen, 1969), is readily recognized by its tricolpate pollen grains with markedly thick exine as seen in LM in combination with a microechinate and perforate sculpturing observed in SEM.

Figure 12.

Convolvulaceae pollen from the middle Eocene of Stolzenbach, Germany. A--C. Merrermia sp. ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing microechinate, perforate sculpturing of mesocolpium. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B, and 1 μm in C.

Gentianales

The report of a flower of Gentianaceae from the Eocene of Texas (Crepet & Daghlian, 1981) has not held up to close scrutiny. It was based on a single faintly preserved flower impression with seven well developed apically pointed tepals and a central area with remnants of stamens containing well preserved pollen of the extinct genus Pistillipollenites Rouse. Similar gemmate pollen occurs in some Gentianaceae, but is not limited to that family. Stockey and Manchester (1988) described another specimen, better preserved, but apparently of the same kind of flower, also bearing in situ Pistillipollenites pollen, from the middle Eocene of Horsefly, British Columbia. It is similar to the Texas flower in size and perianth configuration but shows 6 rather than 7 perianth lobes and a single anther opposite each lobe of the perianth (which they interpreted as calyx rather than corolla). The variability of 6 of 7 sepals and the configuration of separate anthers is unlike the flowers of Gentianaceae, which have the connate, basally attached stamens. As yet, the systematic affinities of these flowers, which are also present in the Paleocene and Eocene of Wyoming and North Dakota, referred to as Calycites polysepala Newberry (Manchester 2014), are undetermined.

Rubiaceae

Paleobotanical literature with reports of Rubiaceae fossils was comprehensively reviewed by Graham (2008). There is a substantial fossil pollen record, plus occasional megafossil reports. Graham indicated which records he considered acceptable, and diplomatically indicated those which require more study as “pending”. A relatively early megafossil record of Rubiaceae is that of permineralized fruiting capsules named Emmenopterys dilcheri Manchester (1994) from the middle Eocene of Oregon with intact winged seeds from the middle Eocene of Oregon. The fossil was attributed to the modern genus Emmenopterys Oliv., but broader comparative work with modern genera in the same tribe Condamineeae sensu Kainulainen et al. (2010) would be desirable.

The leaves called Paleorubiaceophyllum Roth & Dilcher have not held up as Rubiaceae. The peculiar feature of those leaves is a foliar appendage commonly persisting at the base of the petiole on shed leaves. Roth and Dilcher (1979) compared these with the adnate stipules of some extant Rubiaceae, but in that family, including the genera they cited as most similar, each pair of stipules is fused and remain on the twig when the leaves abscise. A subsequently recovered fossil twig with attached leaves of P. eocenicum (Berry) Roth & Dilcher with the intact stipules shows that the leaves were borne alternately rather than oppositely (UF-15738-27774), making it unlikely that this fossil is related to Rubiaceae. Roth and Dilcher (1979) successfully demonstrated that the species does not belong to Leitneria Chapm., or any of the other modern genera to which earlier investigators had assigned them; however, the true affinity of this plant, which was common at many sites in the Eocene of Tennessee and Mississippi, remains an interesting taxonomic puzzle.

Lamiales sl.

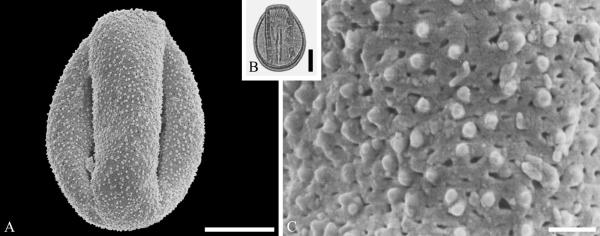

Within Lamiales sl., the Oleaceae are well represented by samaoid fruits of Fraxinus L. starting in the early and middle Eocene of Asia and North America as reviewed by Call & Dilcher (1992). Pollen of Oleaceae are here documented from the Late Cretaceous (early Campanian) of Elk Basin, of Wyoming (Fig. 13A--C) and middle Eocene Princeton chert of British Columbia (Fig. 13D--F). Oleaceae pollen grains are mostly tricolporate, with very small and indistinct pori (Punt et al., 1991). Many Oleaceae pollen grains are also distinguished by their reticulate sculpturing and microechinate suprasculpture or segmented muri as seen in Figure 13. Combined SEM and light microscopy have been used to identify grains as Fraxinus, Olea, and Phillyrea from upper Oligocene/lower Miocene sediments of Altmittweida, Saxony, Germany (Kmenta & Zetter, 2013). Wood of Oleaceae is traced to the latest Cretaceous Deccan Intertrappean Beds of India (Tivedi & Srivastava, 1982; Srivastava et al., in press).

Figure 13.

Oleaceae pollen from the Late Cretaceous of Wyoming, USA (A--C), and the middle Eocene of Princeton Chert, Canada (D--F). A--C. Oleaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---A. SEM micrograph, polar view. ---B. LM micrograph of the same grain, polar view. ---C. Close-up showing reticulate sculpturing with microechinate suprasculpture, and microechinate and microverrucate colpus membrane. D--F. Oleaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---D. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---E. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---F. Close-up showing segmented reticulate sculpturing. Scale bars 10 μm in B, E, and 1 μm in A, C, D, F.

Seeds of Bignoniaceae appear in the Paleocene (Horiuchi & Manchester, 2011; Manchester, 2014), with small seeds somewhat similar to Catalpa Scop. (but not that genus) from North America and Japan (~58 Ma). Large membranous seeds showing also the cordate outline of the cotyledons characteristic of Bignoniaceae from the middle Eocene of Tennessee were attributed to a fossil genus, Grotea Wang, Blanchard & Dilcher (2013).

Pedaliaceae

Trapella Oliv. has distinctive elongate, longitudinally ribbed fruits with a set of prominent laterally extended apical spines, and have been identified in the Miocene and Pliocene of Europe (Tralau, 1964, 1965a).

Acanthaceae

Tripp and McDade (2014) scrutinized the published fossil record of this family. They were aware of 51 published reports, and accepted several of them fossils as sufficiently convincing to use as basis for age-calibrating their phylogeny of the family. To assess the utility of fossils for divergence time estimates, Tripp and McDade (2014) tabulated the fossils according to their ranks of confidence in the taxonomic identifications and age estimates and then utilized only those that received high scores. Fossils that were recently accepted for this family include the seed of Acanthus rugatus Reid & Chandler (1926) from the early Oligocene Bembridge flora of England. Tripp and McDade (2014) expressed reservations about this though, noting that seed sculpture has not been exhaustively surveyed across tribe Acantheae. In addition, the seed is only known from its external characters, without other anatomical information, and it is not hard to imagine that this seed could represent an unrelated family.

Among the amazing diversity of pollen morphological types in extant Acanthaceae (Scotland & Vollesen, 2000), some are very distinctive and readily recognized in the fossil record. This allowed Tripp and McDade (2014) to support the published taxonomic placements of a fossil similar to Hulemacanthus S. Moore (Raj, 1961) from the Miocene of Nigeria, and Areolipollis insularis Mautino from the upper Miocene of Mexico. The latter fossil is dicolporate with distinctive areoles that surround the germinal apertures, traits known only from Justicieae (Graham, 1988).

Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae fossil records are not very good. Reid & Chandler (1926) recognized the lamiaceous genera Ajuginucula Reid & Chandler and Melissa L., but the external structures preserved are not sufficiently distinctive to be fully confident about these determinations. Stephano(6)-colpate and doubly reticulate pollen consistent with Lamiaceae is recognizable, for example, from the Miocene of China (Fig. 14A--C) and the middle Miocene of Austria (authors pers. observ.).

Figure 14.

Lamiaceae pollen from the middle to late Miocene of Beipaizi, northeast China. A--C. Lamiaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---A. SEM micrograph, polar view. ---B. LM micrograph, polar view. ---C. Close-up showing bireticulate sculpturing in mesocolpium. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B, and 1 μm in C.

Aquifoliales

Tricolporate pollen of Ilex L., with distinct clavate ornamentation, is readily recognizable in the fossil record, as exemplified by the specimens shown here from the Eocene of Profen, Germany (Fig. 15A--C) and Miocene of Beipaizi, northeastern China (Fig. 15D--F). In a review of the widespread fossil pollen record for Ilex, Martin (1977) accepted many Eocene and younger records throughout the world. She also noted reports from the Cretaceous, but these remain to be well documented with SEM. An example is Ilexpollenites F. Thiergart ex R. Potonié from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian to Maastrichtian) of California (Chmura, 1973).

Figure 15.

Aquifoliaceae. Ilex L. pollen from middle Eocene of Profen, central Germany (A--C), and the middle to late Miocene of Beipaizi, northeast China (D--F). A--C. Ilex sp. ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing clavate and microbacculate sculpturing in central mesocolpium. D--F. Ilex sp. ---D. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---E. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---F. Close-up showing clavate and microbacculate sculpturing in polar area. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B, D, E, and 1 μm in C, F.

Asterales

The fossil record of Campanulaceae is rather poor. In addition to the few seed records from Miocene reviewed and accepted by Martínez-Millán (2010), Campanula L. pollen, characterized by combined microrugulate and echinate ornamentation, has been documented by SEM and LM from the Pliocene of Iceland (Denk et al., 2011: pl. 10.14, fig. 1--3).

Menyanthaceae

In addition to the record of a Menyanthes L. seed from the Miocene Nowy Sacz Basin, Poland (Łańcucka-Środoniowa, 1979) accepted by Martinez-Millan, the family is recognized by pollen reviewed by Barreda et al. (2010). Striasyncolpites laxus Mildenh. & Pocknall pollen (illustrated by Barreda et al., 2010, Plate I, 1) is characterized by oblate, tricolporate, parasyncolpate grains with striate exine, and greatly resembles the pollen of extant herbaceous genera, Villarsia Vent. and Liparophyllum Hook. f. This pollen type occurs in the Oligocene and Miocene of New Zealand, Australia and Patagonia (Mildenhall & Pocknall, 1989; Macphail & Hill, 1994; Macphail, 1999; Zetter et al., 1999; Palamarczuk & Barreda, 2000; Barreda et al., 2010).

Goodeniaceae are also known best from dispersed pollen records extending back to the Oligocene. Grains of Poluspissusites Sal.-Cheb. are prolate to subprolate, tricolporate, with the exine thicker at poles, clearly stratified, with digitate infratectal columellae. They have general similarities to the Scaevola--Goodenia group and are known from the Oligocene of Cameroon (P. digitatus Sal.-Cheb.; Salard-Cheboldaeff, 1978) and late Oligocene and early Miocene of New Zealand (P. ramus Pocknall; Pocknall, 1982; Macphail, 1999) and Patagonia (P. puntensis Barreda; Barreda, 1997a,b; Barreda et al., 2010, pl. I, 2), and late Miocene--Pleistocene of Australia (P. ramus) (Macphail, 1999).

Calyceraceae pollen has been identified with studies employing both SEM and light microscopy from the early and late Miocene of Chubut province, Argentina (Palazzesi et al., 2010). The small, tricolporate, subspheroidal to suboblate pollen grains, rhombic in equatorial view and subtriangular in polar view, are relatively distinctive. In addition, Palazzesi et al. (2010) note that the fossil grains have tectate, columellate exine and the nexine is thickened toward endoapertures causing a distinctive wall protrusion on the external surface, similar to what is observed in modern pollen of the Gamocarpha DC. type of the Calyceraceae. According to Palezzesi et al. (2010), these fossils “establish the presence of related species in the Miocene of southern South America. The first major radiation of this family occurred during a period of significant shift to more arid conditions that caused extinction of numerous Gondwanan elements but had little effect on the Calyceraceae.”

Asteraceae

The fossil record of Asteraceae is best known from dispersed pollen records, and credible megafossil records have been few (Graham, 1996). However, the impression of a fossil capitulum, Raiguenrayun cura Barreda, Katinas, Passalia & Palazzesi, with multiseriate-imbricate involucral bracts and pappus-like hairs, recently described from the Eocene of Argentina (~47.5 Ma; Barreda et al., 2012), displays a set of morphological features today diagnostic of Asteraceae. The suite of characters seen in this fossil conform with those found in taxa considered phylogenetically close to the root of the family, “such as Stifftieae, Wunderlichioideae and Gochnatieae (Mutisioideae sensu lato) and Dicomeae and Oldenburgieae (Carduoideae), today endemic to or mainly distributed in South America and Africa” (Barreda et al., 2012: 127). Apart from the infructescence of R. cura, it seems strange that individual pappus-bearing achenes are not common in the fossil record, given their adaptation for wind dispersal, they should be preserved as impression fossils in lacustrine deposits.

The worldwide fossil record of the Asteraceae was reviewed by Graham (1996). Along with the literature review, he included images documenting pollen grains from Neogene sites in Panama, Mexico, and Haiti. Although most megafossil reports reviewed by Graham (1996) are dubious (including Baccharites G. Saporta leaves and Cypselites Heer fruits), many of the dispersed pollen records are convincing records for the family, and some can be assigned to specific clades based on pollen ornamentation, including representatives of Ambrosia L. type, Liguliflorae type, Lactuceae-Veronieae type, Mutisia L. f. type. The early pollen records in Europe, North America, and India were recorded as late Oligocene, and as early Miocene in Africa, Australia, and East Asia. Asteraceae include a number of readily recognized pollen types, some with highly distinctive ornamentation. Here we illustrate examples of asteraceous pollen from the Eocene Princeton Chert of British Columbia (Fig. 16A--C) and from the Miocene of China (Fig. 16D--I), documented by LM and SEM.

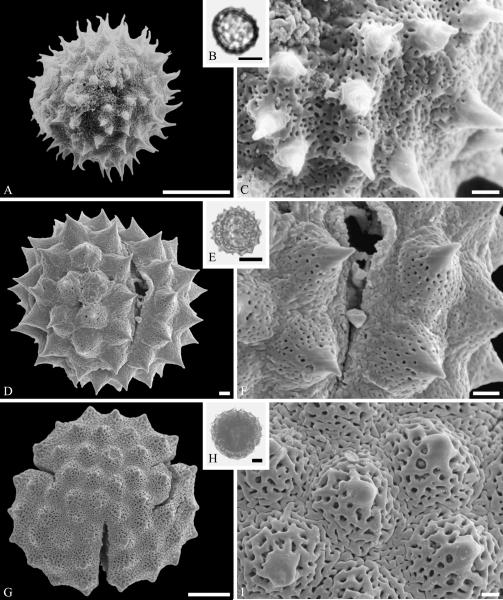

Figure 16.

Asteraceae pollen from the middle Eocene of Princeton Chert, Canada (A--C) and from the middle to late Miocene of Beipaizi, northeast China (D--I). A--C. Asteraceae gen. et spec. indet. ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph. ---C. Close-up showing echinate and perforate sculpturing in mesocolpium. D--F. Asteraceae gen. et spec. indet. ---D. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---E. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---F. Close- up showing echinate and perforate sculpturing in mesocolpium, and microverrucate colpus membrane around colporus. G--I. Asteraceae gen. et spec. indet. ---G. SEM micrograph, polar view. ---H. LM micrograph, polar view. ---I. Close up showing echinate and perforate sculpturing in polar area. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B, D, E, G, H, and 1 μm in C, F, I.

Different clades of Asteraceae can be recognized based on pollen morphology. Pollen grains characteristic of tribe Mutiseae have been recognized from the late Paleocene-Eocene of South Africa, treated under the name, Tubulifloridites antipodica Cookson ex R. Potonié (Zavada & de Villiers, 2000), and from the early Oligocene of northwestern Tasmania, named Mutisiapollis patersonii Macphail & Hill (1994). Fossil pollen from these and other Southern Hemisphere sites have been used to recognize the Barnadesioideae and Nassauvieae, as well as Mutisieae (Barreda et al., 2008).

Apiales

Diversification times and biogeographic patterns have been reviewed recently for the Apiales (Nicolas & Plunkett, 2014). They estimated the origin of Apiales to have occurred in Australasia in the early Cretaceous (~117 Ma). In their assessment, most major clades also appear to have originated in Australasia, with the youngest family (Apiaceae) having originated in the Late Cretaceous, ~87 Ma.

Toricelliaceae

Fruits diagnostic of the extant genus Toricellia DC. are known from the late Paleocene (~58 Ma; Manchester et al., 2009a: figs. 53--56) as well as from the middle Eocene of Oregon (Manchester, 1999: 476, fig. 1) and middle Eocene of Germany (Collinson et al., 2012). Newly obtained micro-CT scan data on early Eocene London Clay fruits (courtesy M. Collinson, 2014) indicates that the fossil species Spondiaecarpon operculatum Reid & Chandler actually corresponds to the extant genus Toricellia and is similar to the species T. bonesii (Manch.) Manch. from Oregon. The distinctive morphological characters of these fruits (both modern and fossil) were well documented by Meller (2006) in a study of well preserved specimens from the Miocene of Germany.

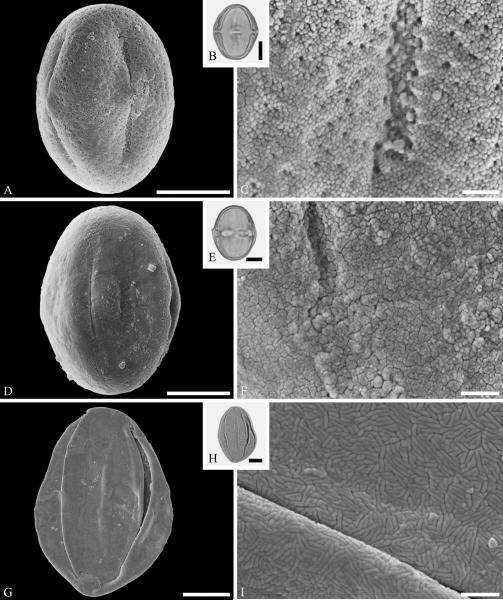

Araliaceae

Pollen of Araliaceae, with combined characteristic features including thick exine, especially thickened around the apertures, microreticulate to reticulate or rugulate (perforate, fossulate) sculpturing under SEM, and often lalongate endoapertures, are known from the Late Cretaceous (early Campanian) of Wyoming (Fig. 17A--C), Paleocene and Eocene of Greenland (Fig. 17D--F), and Eocene of Western North America (Fig. 17G--I) and Europe (Profen, Germany; authors pers. obs.). Pollen assignable to the genus Aralia L., distinguished by its thickened exine in polar areas in combination with other general features of Araliaceae is recognized from the Eocene Princeton chert of British Colombia (Fig. 17 G--I).

Figure 17.

Araliaceae pollen from the Late Cretaceous of Wyoming, USA (A--C), the early Paleocene of Agatdalen, central West Greenland (D--F), and the middle Eocene of Princeton Chert, Canada (G--I). A--C. Araliaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing reticulate to microreticulate sculpturing in mesocolpium. D--F. Araliaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---D. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---E. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---F. Close-up showing verrucate, fossulate and perforate sculpturing. G--I. Aralia L. sp. ---G. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---H. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---I. Close-up showing microreticulate to reticulate sculpturing in mesocolpium. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B, D, E, G, H, and 1 μm in C, G, I.

An Eocene fossil leaf species that was documented in anatomical detail and attributed to extant Dendropanax Decne. & Planch. (Dilcher & Dolph, 1970) and accepted as valid Araliaceae in some subsequent works (e.g., Martínez-Millán, 2010; Nicolas & Plunkett, 2014) needs to be reconsidered. The perfectly symmetrical and consistently lobed leaves do not match with Dendropanax which is inconsistently lobed even on the same twig, and tends to be longer than wide. We could not find a convincing match among any extant Araliaceae. Somewhat similarly lobed leaves are found in extant Acanthopanax (Decne. & Planch.) Miq., Eleutherococcus Maxim., and Kalopanax Miq., but those leaves are strongly serrate in contrast to the entire-margined leaves of the fossil. As Dilcher and Dolph (1970) pointed out, the fossil leaves differ significantly from modern Dendropanax by the consistently papillate lower epidermis with a single central papilla per cell in the fossil, that is not seen in any modern species of the genus. This feature has not been documented in any other modern Araliaceae either. Dilcher and Dolph (1970) were intrigued that the Tennessee fossils were consistently prominently lobed, whereas modern Dendropanax has lobe leaves mostly just in juvenile condition whereas mature leaves are unlobed. These are important differences that readily exclude the fossil from Dendropanax.

Despite the questionable Eocene leaf record of Araliaceae, there are fossil fruits from the Eocene that show the schizocarpic fruit type and persistent epigynous perianth, consistent with assignment to this family, such as Paleopanax Manch. from the Clarno Formation of Oregon (Manchester, 1994), and an unnamed specimen from the middle Eocene Claiborne Formation of Tennessee (Fig. 19A).

Figure 19.

Apiaceae pollen the middle to late Miocene of Beipaizi, northeast China. A--C. Apiaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing rugulate and striate sculpturing in mesocolpium. D--F. Apiaceae gen. et spec. indet. ---D. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---E. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---F. Close-up showing rugulate to verrucate and fossulate sculpturing in mesocolpium. Scale bars 10 mm in A, B, D, E, and 1 μm in C, F.

Apiaceae

Fruits of Apiaceae are confirmed from the Late Cretaceous based on Carpites ulmiformis Dorf (1942) from the Maastrichtian of Montana, and Wyoming (Manchester & O'Leary, 2010). This species is based on well preserved winged fruits with a persistent epigynous calyx of several equal, basally fused tepals; each disseminule has an elliptical fruit body with a pair of prominent lateral wings. Although C. ulmiformis does not conform precisely to a modern genus, the disseminules resemble mericarps of extant Thapsia polygama Desf. and Astrotricha cordata A. R. Bean as illustrated for comparison by Manchester and O'Leary (2010).

Apiaceous fruits have been recovered from the Eocene Green River Formation of Utah. These are schizocarps with a stylopodium and peristent epigynous perianth (Fig. 19B, C). Apiaceae pollen is also recognizable in the fossil record. We illustrate examples from the middle to late Miocene of Beipaizi, northeast China (Fig. 18). The prolate tricolporate grains show a distinctive rugulate and striate to verrucate and fossulate ornamentation.

Figure 18.

Araliales and cf Araliales. ---A. Fruit of Araliaceae from the middle Eocene Puryear clay pit of the Claiborne Formation, Tennessee. Note apical styles arising from an apical depression surrounded by perianth rim . UF15820-53151. ---B. Apiaceous umbel from early middle Eocene Green River Formation of Colorado, UF584-58340. ---C. Detail of fruit from B showing stylopodium and recurved styles. D--F. The oldest potential Araliales fossil, Araliaecarpum kolymensis Samylina, from the Early Cretaceous (Albian) Buor-Kemiusskaja locality of eastern Siberia. ---D, E. Pedicellate fruits in face view. Perianth position unclear. ---F. Fruit in transverse section showing what appear to be two mericarps. Scale bars 1 cm in A, 0.5 cm in B, D-F; 2 mm in C.

Araliaecarpum

The oldest potential Araliales fossil, and indeed the oldest potential Asterid, is the fruit called Araliaecarpum kolymensis Samylina from the early Cretaceous (Albian) Buor-Kemiusskaja locality near the Zyrianka River in eastern Siberia (Samylina, 1960). The fruit is about 6 mm long and is syncarpous with two carpels borne on a thin pedicel (Fig. 19D, E). It is possible that the fruits were schizocarpic as suggested by transverse section (Fig. 19F, G). An important question is whether this fruit developed from an epigynous flowers as expected in Apiales, or from a hypogynous. If hypogynous, then some Malvid families, e.g., Brassicaceae, Sapindaceae might come into consideration. There is no obvious swelling at the junction of the fruit and pedicel that would be interpreted as the position of hypogynous perianth. On the other hand, there is not any obvious perianth bulge or scar at the apical side of the fruit. More detailed anatomical comparative work is needed to assess whether the resemblance to Apicaceae is more than a superficial one.

Dipsacales

Adoxaceae

Pollen of Viburnum L. can be quite distinctive and sometimes readily recognizable down to particular sections/clades (e.g., Donoghue, 1985) when studied by both SEM and LM. Augmenting examples of Viburnum pollen are the clade Lentago, from the middle Miocene of Iceland (plate 4.9 in Denk et al., 2011). Another type of Viburnum pollen we document from the Eocene of the Princeton Chert of British Columbia (Fig. 20A--C), shows the high reticulum with numerous free-standing collumellae in the luminae, typical of, e.g., Solenotinus (DC.) Spach and Tinus Mill. clades and in V. clemensae J. Kern (pers. comm. M. J Donoghue, 2014).

Figure 20.

Viburnum L. (Caprifoliaceae) pollen from the middle Eocene of Princeton Chert, Canada (A--C). ---A. SEM micrograph, equatorial view. ---B. LM micrograph, equatorial view. ---C. Close-up showing reticulate sculpturing in mesocolpium, lumina with numerous freestanding columellae. Scale bars 10 μm in A, B and 1 μm in C.

Many of the published megafossil reports of Viburnum have not held up to close scrutiny. The Paleocene leaf and fruit records of formerly assigned to species of Viburnum have all been discredited, with reassignments to Cornales as Beringiaphyllum (Manchester et al., 1999), Davidia (Manchester, 2002), and Browniea (Manchester & Hickey, 2007) and to Cannabaceae with the transfer of V. asperum Newberry to Celtis L. (Manchester et al., 2002).

Dipsacales are also known from winged fruits of Linnaeoideae (Caprifoliaceae) from the late Eocene (~36 Ma), representing the extant genus Dipelta in the late Eocene of Southern England (Reid & Chandler, 1926) and Mississippi (Manchester et al., 2009a) and the extinct genus Diplodipelta Manchester & Donoghue (1995). Several pollen types present among extant of Dipsacales are distinctive (Donoghue, 1985) and readily recognizable in the fossil record. Here we provide examples of the distinctive echinate pollen of Linnaeoideae from the middle Eocene of Greenland (Fig. 21A--C) and Germany (Fig. 21 D--F) and Lonicera L. from the Late Eocene of Colorado, USA (Fig. 21G--I).

Figure 21.