Abstract

Nocardia can cause isolated disease in many parts of the body including the brain, skin, and lungs. It is also capable of causing disseminated disease. In almost all cases, Nocardia infections occur in immunocompromised hosts with depressed cell-mediated functions. We present a case of disseminated Nocardia farcinica leading to pericardial effusion and tamponade in an immunocompetent host with the only risk factor being heavy alcohol intake. Treatment relies on an accurate diagnosis. This case presentation highlights the importance of considering Nocardia infections in an alcoholic patient with a worsening clinical picture.

Keywords: cardiac tamponade, alcohol abuse, pericardial effusion, immunocompetent patient, nocardia farcinica

Introduction

Nocardia species are gram-positive, filamentous, environmental saprophytic rod-shaped bacteria [1-3]. Nocardiosis is rare and can present as acute bronchopneumonia, cutaneous pustules, or disseminated disease [2-3]. Nocardia pericarditis is very uncommon, with only a few documented cases due to Nocardia farcinica (N. farcinica) [4-5]. The majority of N. farcinica infections occur in immunocompromised patients [6-8]. We describe a case of N. farcinica pericarditis, leading to pericardial tamponade in an immunocompetent host with alcohol use disorder as the only predisposing risk factor. Because diagnosis requires specially ordered microbiologic mediums and delay in diagnosis and treatment can result in significant morbidity and mortality, consideration of N. farcinica early in the presentation is crucial.

Case presentation

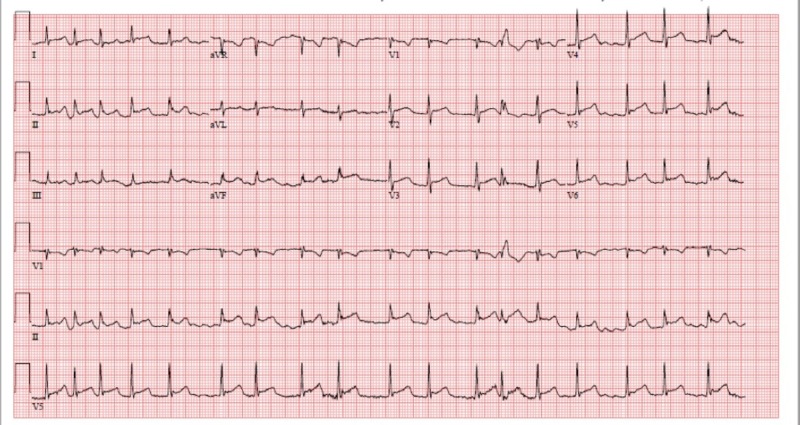

A 60-year-old man with a history of heavy ethanol abuse presented with three weeks of worsening shortness of breath associated with positional chest pressure improved by sitting forward. He denied other upper respiratory symptoms including nasal congestion, sore throat, or cough. An electrocardiogram (EKG) showed new-onset atrial fibrillation and diffuse ST segment elevations (Figure 1).

Figure 1. EKG showing atrial fibrillation and diffuse ST elevations.

EKG: electrocardiogram

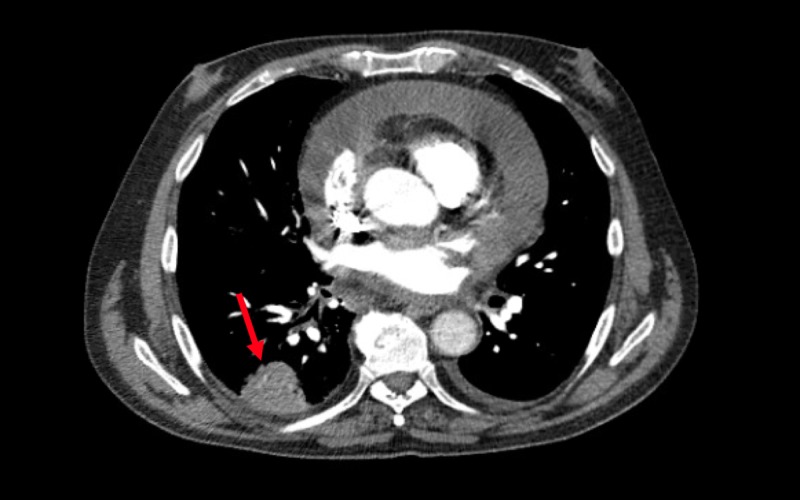

Subsequently, a transthoracic echocardiogram was done revealing a large, greater than 2 cm, pericardial effusion with greater than 30% variation of mitral inflow velocity with impairment of the right ventricular filling consistent with tamponade physiology. The patient underwent a pericardial window which yielded 300 mL of serous fluid with evidence of epicardial and pericardial inflammation. Pericardial fluid studies were significant for inflammation without an infectious or malignant source at that time. Other studies including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), hepatitis panel, Ehrlichia chaffeensis titers, and Lyme titers were all negative. Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest ruled out pulmonary embolism but revealed a right lower lobe pulmonary nodule. For the nodule, he underwent a CT-guided lung biopsy demonstrating organizing pneumonia (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Computed tomography of the chest with the arrow pointing towards a right basilar pulmonary nodule.

Repeat EKG was performed for worsening respiratory distress and demonstrated a moderate pericardial effusion and constrictive pericarditis with severe right ventricular dysfunction. The patient decompensated requiring intubation, Swan-Ganz catheter placement, and vasopressor and inotropic support. At this time, pericardial fluid studies, bronchoalveolar lavage, and respiratory cultures were done earlier started to grow N. farcinica, prompting consultation of the infectious disease team and initiation of antibiotics including imipenem/cilastatin, linezolid, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim for disseminated nocardiosis. In this case, the only predisposing factor for disseminated nocardiosis was his chronic alcohol abuse.

Discussion

Nocardia can hematogenously spread to infect many organ systems and can be very difficult to diagnose due to slow growth requiring selective mediums [2,9]. Lung-limited infection occurs in approximately 39% of cases, central nervous system-limited infection in 9% of cases, cutaneous-limited infection in 8%, and disseminated infection occurs in 32% of cases [2]. Very rarely, Nocardia can lead to purulent pericarditis requiring surgical drainage [9]. There are several subspecies of Nocardia known to cause disease in humans; around 80% of respiratory infections and disseminated infections are caused by N. asteroides [5,8,10]. However, N. farcinica has a higher propensity for dissemination due to its higher virulence and proneness to antibiotic resistance [7,10].

There are approximately 500 to 1,000 newly diagnosed significant infections due to Nocardia species per year in the United States and around two-thirds are in immunocompromised hosts [8,11]. In a review of 52 cases of N. farcinica infections, 85% of patients had a predisposing condition for acquiring the infection [6-7]. Cell-mediated impairments predispose patients for Nocardia infections such as organ transplants, human immunodeficiency virus, immune suppression, and systemic lupus erythematosus [2-3,9,12-13]. Alcoholism is not one of the frequently cited predisposing conditions; however, alcohol is known to be an immunosuppressant, especially with respiratory infections [14].

We present a rare case of N. farcinica leading to pericardial effusion and subsequent tamponade in an otherwise immunocompetent host other than heavy alcohol use. This underscores the importance of identifying alcohol use disorder as a strong risk factor for Nocardia infections and screening for it in patients with a worsening clinical picture.

Conclusions

Early identification of Nocardia is essential to provide appropriate treatment. However, because special media is required for identifying Nocardia, a high clinical suspicion for the diagnosis is required. Nocardia should be considered in patients with worsening clinical status even in immunocompetent patients if they have risk factors such as alcoholism.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study

References

- 1.McAdam AJ, Milner DA, Sharpe AH. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015. Infectious diseases; pp. 341–402. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nocardia and actinomyces. Henderson NM, Sutherland RK. Medicine. 2017;45:753–756. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan KJ. Sherris Medical Microbiology, 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2018. Actinomyces and Nocardia; pp. 537–544. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nocardia farcinica pericarditis after kidney transplantation despite prophylaxis. McPhee L, Stogsdill P, Vella JP. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009;11:448–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2009.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purulent pericarditis and cardiac tamponade caused by Nocardia farcinica in a nephrotic syndrome patient. Sirijatuphat R, Niltwat S, Tiangtam O, Tungsubutra W. Intern Med. 2013;52:2231–2235. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Infection caused by Nocardia farcinica: case report and review. Torres OH, Domingo P, Pericas R, Boiron P, Montiel JA, Vázquez G. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10795594. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s100960050460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fatal pulmonary Nocardia farcinica infection. De La Iglesia P, Viejo G, Gomez B, De Miguel D, Del Valle A, Otero L. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1098–1099. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.3.1098-1099.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torres A, Menendez R, Wunderink RG. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016. Bacterial pneumonia and lung abscess; pp. 557–582. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purulent pericarditis accompanying pericardial abscess induced by Nocardia in an immunocompromised patient. Takashima A, Yagi S, Yamaguchi K, et al. Circ J. 2016;80:2409–2411. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Case of the season: disseminated nocardiosis. Daniel JH, Ravenel JG. Semin Roentgenol. 2007;42:4–6. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nocardiosis. [Jan;2019 ];Rawat D, Sharma S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526075/ StatPearls. 2018

- 12.Nocardia bacteremia and endocarditis in a patient with a sulfa allergy. Kuretski J, Dahya V, Cason L, Cason L, Chalasani P, Ramgopal M. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352:542–543. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Special clinical manifestations of Nocardia: two cases and a literature review. Songsong Y, Jing W, Qiuhong F. Chest. 2016;149:127. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alcohol and the immune system. Sarkar D, Jung MK, Wang HJ. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4590612/ Alcohol Res. 2015;37:153–155. [Google Scholar]