Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of our study was to investigate the association of different socioeconomic and sociodemographic factors with dental caries in six-year-old children. Furthermore, we applied a district based approach to explore the distribution of dental caries among districts of low and high socioeconomic position (SEP).

Methods

In our cross-sectional study 5,189 six-year-olds were included. This study was embedded in a prospective population-based birth cohort study in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, the Generation R Study. Parental education level, parental employment status, net household income, single parenting, and teenage pregnancy were considered as indicators for SEP. Dental caries was scored on intraoral photographs by using the decayed, missing, and filled teeth (dmft) index. We compared children without caries (dmft=0) to children with mild caries (dmft=1–3) or severe caries (dmft>3). Multinomial logistic regression analyses and binary logistic regression analyses were performed to study the association between SEP and caries, and between district and caries, respectively.

Results

Only maternal education level remained significantly associated with mild caries after adjusting for all other SEP-indicators. Paternal educational level, parental employment status, and household income additionally served as independent indicators of SEP in children with severe caries. Furthermore, living in more disadvantaged districts was significantly associated with higher odds of dental caries.

Conclusion

Dental caries is more prevalent among six-year-old children with a low SEP, which is also visible at the district level. Maternal educational level is the most important indicator of SEP in the association with caries.

Clinical Significance

Our results should raise concerns about the existing social inequalities in dental caries and should encourage development of dental caries prevention strategies. New knowledge about the distribution of oral health inequalities between districts should be used to target the right audience for these strategies.

Keywords: pediatric dentistry, dental caries, ethnicity, socio-economic status, epidemiology, cross-sectional analysis

1. Introduction

Dental caries in children leads not only to tooth pain, but also leads to significant health losses in a population, affecting the quality of life of both children and their parents [1–3]. Moreover, it leads to considerable costs in the short and long term [4]. Identifying high-risk populations for developing dental caries can help to lower the incidence of these health issues by targeting the right audience with preventive strategies.

It is well known that a lower socioeconomic position (SEP) is related to poorer health outcomes [5]. This also seems to apply for oral health outcomes. For example, a recent meta-analysis by Schwendicke et al. [6] showed a low socioeconomic position (SEP) to be significantly associated with a higher risk of having dental caries in both children and adults. Various other studies in oral health research also presented a higher caries prevalence in children with a low SEP [7–9]. Possible mediating pathways for the association between SEP and caries, however, have been suggested but have not been studied well yet. Moreover, among these studies SEP was not measured in a uniform way. Often only one or two indicators for SEP are chosen, i.e. parental educational level, household income or parents’ employment status. In the Netherlands, maternal educational level or residential neighborhood are most commonly used as indicator for SEP [10–12]. However, different studies have advised using more than one or two indicators of SEP. This may increase comparability and may avoid residual confounding [6,13]. Therefore, we wanted to study all advised indicators for family SEP in relation to dental caries [13].

Recently, dental caries was found to be clustered in more deprived areas within a country and even within a city [14–16]. This could be associated with clustering of low SEP families within a particular district. Less access to dental care within a district due to a lower density of available (pediatric) dentists could also be an explanation. It is important to distinguish between these explanations, since this information could help to improve targeting of preventive strategies. Moreover, possible weaknesses within a living area, perpetuating health inequalities, could be identified. Therefore, we also wanted to study the distribution of caries in the city of Rotterdam, the Netherlands. With this information we hoped to answer the question whether possible differences could be only explained by differences in social background or also by characteristics of the district itself.

Summarizing, the purpose of our study was to investigate the association of different socioeconomic and sociodemographic factors on dental caries in six-year-old children. Furthermore, we applied a district approach to explore the distribution of dental caries within the city of Rotterdam, the Netherlands. With this information we also tried to identify possible explanations of the identified differences between districts.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional study, embedded in the Generation R Study, situated in the city of Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The Generation R Study is a prospective population-based cohort study and was designed to identify environmental and genetic determinants of growth, development and health. The design of this cohort is described in detail elsewhere. For this purpose, children have been followed from fetal life until adulthood in Rotterdam, the Netherlands [17]. The Medical Ethics Committee of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, approved this study (MEC-2007-413). All participants of this study gave written informed consent.

2.2. Study population

All pregnant women with a delivery date between April 2002 and January 2006 and who lived in the study area of Rotterdam, the Netherlands, were eligible for participation in the Generation R Study. From all included children, 8,305 mothers gave consent to participate in the school aged period (5 years onwards) of the Generation R Study. Ultimately, 6,690 children had actually visited the research center. From these, we excluded all participants with incomplete information on dental caries (n = 1,367) and all twin participants (n = 134), leaving a total study population of 5,189 children.

2.3. Socioeconomic position

Since young children cannot have yet established their own socioeconomic level, they were classified according to their parents’ socioeconomic position. We named this family SEP. We considered the following socioeconomic and sociodemographic factors as indicators for family SEP: parental education level, parental employment status (paid job vs. unpaid job), net household income, parenting, and teenage pregnancy. Educational level was categorized based on the Dutch Standard Classification of Education [18]. We defined four educational levels that could be obtained by a parent: low (no education, primary school, lower vocational training, intermediate general school, or three years or less general secondary school), mid-low (more than three years general secondary school, intermediate vocational training, or first year of higher vocational training), mid-high (higher vocational training), and high (university or PhD degree). Paternal and maternal employment status was defined as paid job or no paid job. Net household income was divided into three categories; <2000 euro/month, 2000 – 3200 euro/month and >3200 euro/month. Teenage pregnancy was defined as pregnancy in girls aged 19 years or younger and was based on maternal age at enrolment. All information on socioeconomic and sociodemographic factors were obtained by questionnaires [17].

2.4. Dental caries

We scored the presence of dental caries on intraoral photographs by using the decayed, missing, and filled teeth index (dmft index). We took these pictures with either the Poscam USB intraoral (Digital Leader PointNix) or Sopro 717 (Acteon) autofocus camera. Both cameras had a resolution of 640x480 pixels and a minimal scene illumination of 1.4 and 30 lx. The usage of intraoral photographs, compared to ordinary oral examination, in scoring dental caries with a dmft index has been described elsewhere and showed to have high sensitivity and specificity (85.5% and 83.6% respectively) [19]. Furthermore, we evaluated intra-observer reliability (K = 0.98) and inter-observer reliability (K = 0.89), both indicating an almost perfect agreement [20].

For the analyses, we categorized the children as having no dental caries (dmft = 0), having mild caries (dmft = 1 - 3), or having severe caries (dmft > 3). The cut-off values for mild and severe caries were based on the mean dmft index of five-year-old Dutch children obtained from a recent report by Schuller et al. [21].

2.5. Covariates

We considered children’s age, sex, ethnicity, and oral health behavior as potential confounders in the relationship between dental caries and SEP. Children’s ethnicity was based on the birth country of both parents [22]. If one of the parents was born in another country than the Netherlands, the child’s ethnicity was defined as the birth country of that parent. Birth country of the mother was conclusive if both parents were born in another country. For this study we categorized children into two different groups; Dutch/Western and non-Western. Mothers had to fill in questionnaires on oral health behavior of their children at age six. Oral health related behavior was measured by age at first dental visit (0–3 years, > 3 years, or never), dental visits in the past year (yes or no), and tooth brushing frequency (once a day, twice a day, or more than twice a day).

2.6. District approach

To compare caries prevalence between districts with different levels of SEP, the four-digit postal codes were collected from the mothers when the the children were six years of age. The postal code had to be their current living area at the moment of dental caries measurement. We only considered children living in the city of Rotterdam, the Netherlands, for analysis (n = 3,942). In general, Rotterdam has fourteen different districts (Centrum, Prins Alexander, Pernis, Overschie, Noord, Kralingen-Crooswijk, IJsselmonde, Hoogvliet, Hoek van Holland, Hillegersberg-Schiebroek, Feijenoord, Delfshaven, Charlois, and Rozenburg), however we excluded Pernis, Hoek van Holland, and Rozenburg due to low sample sizes within these districts (n < 20). We ranked the districts from socioeconomically weakest to strongest district, using individual based indicators of SEP. For this, we calculated the prevalence of low SEP, for each SEP indicator, within a district. Afterwards, we took the sum of these to calculate a total prevalence of low SEP indicators per district. By using these numbers, each district could be ranked from lowest to highest total prevalence. We used this ranking to compare our data to the municipality of Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and to visually depict the districts from weakest to strongest. Moreover, the ranking was used to assess the reference district for regression analysis (socioeconomically strongest district). Caries prevalence was calculated for each district by dividing the total number of children with a dmft > 0 by the total number of children living in that district. We used the open-source desktop Geographic Information System (GIS), QGIS 2.8.4-Wien, for Mac, for geo-mapping our ranking of the districts and caries prevalence per district. The difference between the highest and lowest total prevalence of low SEP indicators was divided by four to construct four even quartiles. We applied the same method for caries prevalence.

2.7. Statistical analyses

Characteristics of the study population were calculated and presented as absolute numbers with percentages for categorical variables and median values, with 90% range, for continuous variables.

A multinomial regression analysis was performed to analyze the association between all SEP indicators and dental caries, expressed in odds ratio’s (OR’s) with 95% confidence intervals (CI’s). Children were categorized into three groups based on their dental caries experience (dmft = 0 versus dmft = 1-3 or dmft > 3). Three different regression models were constructed. The first model, was adjusted for children’s age, sex and ethnicity only. The second model was additionally adjusted for children’s oral health behavior. The third model was additionally adjusted for all other SEP indicators, to investigate their mediating effects on the association between every single SEP indicator and caries. Moreover, we checked whether the presence of Hypomineralized Second Primary Molars (HSPMs) altered the association between SEP and dental caries [23]. This was not the case and therefore the presence of HSPM was not included in the third model.

Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the association between the social ranking of a district and dental caries. In this analysis, the district with the highest social ranking (Hillegersberg-Schiebroek, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) was used as the reference category. First, a crude model, including only the districts as independent variables was built. Second, this model was adjusted for child’s age, sex, and ethnicity. Third, this model was additionally adjusted for all SEP indicators.

Children with complete data on all SEP indicators were compared with children with missing data on at least one SEP indicator by using a Pearson Chi-Square test (Table S1). Parents of children with missing information on at least one indicator of SEP were lower educated (p < 0.001), were more often unemployed (p < 0.005), had a lower household income (p < 0.001), were more often single (p < 0.001), and had more often a teenage pregnancy (p < 0.001). To handle the missing data, we performed multiple imputation by using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method [24]. Ten independent datasets were generated by this method after which the pooled effect estimates were calculated [25]. The relationship between all variables, that have been used in this study, served as a predictor in the multiple imputation models. We used the Statistical Package of Social Sciences version 22.0 for Mac (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) for our statistical analyses. A p-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

2.8. Non-response analysis and stratified analysis

We compared the children which were excluded from analysis (incomplete information on caries, n = 1,334) with the children that were included in the study (n = 5,189) on all indicators of SEP (Table S2). There were no significant differences of all indicators between participants with incomplete information on dental caries and participants with complete information (p > 0.05). Moreover, since ethnicity is related to SEP, we performed a stratified analysis under Dutch children only for the association between SEP and dental caries [26,27].

3. Results

3.1. Population characteristics

In table 1 the characteristics of the study population are presented. The children had a median age (90% range) of 6.03 years (5.68 to 7.83). The prevalence of caries in our study population was 31.7%. About 28.6% of the mothers and 33.7% of the fathers had a high level of education. The majority of mothers and fathers had a paid job (75.4% and 93.9%, respectively) and almost half of the parents reported a household income of more than 3,200 euros per month (49.7%). The household was run by a single parent in 21.0% of the families.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (n = 5,189)

| Total | Missing | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Maternal educational level | High | 1,260 (28.6) | 784 (15.1) |

| Mid-high | 1,215 (27.6) | ||

| Mid-low | 1,386 (31.5) | ||

| Low | 544 (12.3) | ||

| Paternal educational level | High | 1,348 (33.7) | 1,192 (23.0) |

| Mid-high | 913 (22.8) | ||

| Mid-low | 1,085 (27.1) | ||

| Low | 651 (16.3) | ||

| Maternal employment status | Paid job | 3,143 (75.3) | 1,015 (19.6) |

| No paid job | 1,031 (24.7) | ||

| Paternal employment status | Paid job | 3,644 (93.8) | 1,305 (25.1) |

| No paid job | 240 (6.20) | ||

| Household income | > €3200 | 2,075 (49.7) | 1,016 (19.6) |

| €2000-<€3200 | 1,081 (25.9) | ||

| <€2000 | 1,017 (24.4) | ||

| Single parenting | No | 3,518 (79.0) | 738 (14.2) |

| Yes | 933 (21.0) | ||

| Teenage pregnancy | No | 5,044 (97.2) | - |

| Yes | 145 (2.80) | ||

| Ethnic background | Dutch/Western | 3,446 (68.0) | 125 (2.41) |

| Non-Western | 1,618 (32.0) | ||

| Child’s sex | Boy | 2,601 (50.1) | - |

| Girl | 2,588 (49.9) | ||

| Child’s age | Median (90% range) | 6.03 (5.68 - 7.83) | - |

| Tooth brushing | Once a day | 884 (20.7) | 920 (17.7) |

| Twice or more a day | 3,385 (79.3) | ||

| Age first dental visit | 0 - 3 years | 2,389 (54.1) | 770 (14.8) |

| Older than 3 years | 1,863 (42.2) | ||

| Never been | 167 (3.70) | ||

| Dental visit in past year | Yes | 3,967 (92.4) | 897 (17.3) |

| No | 325 (7.60) | ||

| Index dmft | 0 | 3,524 (68.3) | - |

| 1-3 | 995 (19.2) | ||

| > 3 | 652 (12.6) | ||

Table is based on non-imputed data set. Percentages are based on the number of valid cases.

3.2. SEP and caries

Table 2 shows the results of the multinomial logistic regression models. Maternal mid-low or low, as well as paternal low educational level were significantly associated with mild caries (OR 1.55, 95%CI 1.22 to 1.96; OR 2.13, 95%CI 1.64 to 2.77; OR 1.59, 95%CI 1.28 to 1.98 respectively). Also, both maternal and paternal unemployment were significantly associated with mild caries (OR 1.40, 95%CI 1.18 to 1.65; OR 1.48, 95%CI 1.04 to 2.12 respectively). No other indicators were associated with mild caries. However, all SEP indicators were significantly associated with severe caries. After adjusting for the other indicators, only maternal education remained significantly associated with mild caries. For the association with severe caries, however, paternal educational level, parental employment status, and household income additionally served as independent indicators of SEP. No different associations between SEP indicators and dental caries were observed in the stratified analysis under 2,863 Dutch children (Table S3).

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic regression models for the association between Socioeconomic Position (SEP) indicators and dmft indices

| dmft |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | ||||||

| (n = 5,189) | Index 0 | Index 1-3 | Index > 3 | Index 1-3 | Index > 3 | Index 1-3 | Index > 3 | |

| Maternal educational level | High | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| Mid-high | reference | 1.20 [0.95 - 1.52] |

1.37 [0.74 - 2.56] |

1.21 [0.96 - 1.53] |

1.40 [0.74 - 2.65] |

1.18 [0.92 - 1.50] |

1.13 [0.64 - 2.00] |

|

| Mid-low | reference |

1.55 [1.22 - 1.96] |

2.83 [1.55 - 5.15] |

1.56 [1.23 - 1.98] |

2.91 [1.56 - 5.43] |

1.46 [1.10 - 1.93] |

1.83 [1.00 - 3.36] |

|

| Low | reference |

2.13 [1.64 - 2.77] |

6.05 [3.36 - 10.9] |

2.16 [1.62 - 2.87] |

6.38 [3.33 - 12.2] |

1.85 [1.31 - 2.62] |

3.10 [1.60 - 6.02] |

|

| Paternal educational level | High | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| Mid-high | reference | 1.14 [0.90 - 1.46] |

1.39 [0.72 - 2.70] |

1.15 [0.91 - 1.45] |

1.42 [0.74 - 2.69] |

1.03 [0.82 - 1.31] |

1.12 [0.75 - 1.67] |

|

| Mid-low | reference | 1.20 [0.95 - 1.50] |

2.07 [1.28 - 3.37] |

1.20 [0.96 - 1.51] |

2.11 [1.30 - 3.42] |

0.96 [0.75 - 1.23] |

1.30 [0.84 - 2.00] |

|

| Low | reference |

1.59 [1.28 - 1.98] |

4.04 [2.67 - 6.12] |

1.60 [1.28 - 2.04] |

4.18 [2.59 - 6.74] |

1.09 [0.83 - 1.43] |

1.83 [1.13 - 2.96] |

|

| Maternal employment status | Paid job | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| No paid job | reference |

1.40 [1.18 - 1.65] |

2.51 [2.01 - 3.13] |

1.38 [1.17 - 1.63] |

2.52 [1.97 - 3.22] |

1.12 [0.92 - 1.35] |

1.60 [1.25 - 2.04] |

|

| Paternal employment status | Paid job | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| No paid job | reference |

1.48 [1.04 - 2.12] |

2.08 [1.39 - 3.10] |

1.46 [1.01 - 2.11] |

2.05 [1.39 - 3.03] |

1.30 [0.89 - 1.89] |

1.57 [1.04 - 2.37] |

|

| Household income | > €3200 | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| €2000-<€3200 | reference | 1.22 [0.97 - 1.54] |

2.28 [1.39 - 3.74] |

1.22 [0.98 - 1.52] |

2.28 [1.42 - 3.67] |

1.06 [0.86 - 1.32] |

1.66 [1.18 - 2.33] |

|

| <€2000 | reference |

1.55 [1.21 - 1.99] |

3.16 [1.92 - 5.19] |

1.55 [1.22 - 1.97] |

3.19 [1.91 - 5.32] |

1.20 [0.91 - 1.59] |

1.42 [0.88 - 2.29] |

|

| Single parenting | No | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| Yes | reference | 1.17 [0.98 - 1.40] |

1.56 [1.24 - 1.97] |

1.16 [0.97 - 1.39] |

1.56 [1.23 - 1.99] |

0.93 [0.76 - 1.13] |

1.00 [0.76 - 1.33] |

|

| Teenage pregnancy | No | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| Yes | reference | 1.04 [0.67 - 1.61] |

1.85 [1.20 - 2.84] |

1.02 [0.66 - 1.60] |

1.85 [1.18 - 2.88] |

0.80 [0.51 - 1.25] |

1.12 [0.72 - 1.73] |

|

Model 1 = basic model, adjusted for age, sex and child’s ethnicity only;

Model 2 = additionally adjusted oral health related behaviour (Tooth brushing frequency, age at first dental visit, dental visit in past year);

Model 3 = additionally adjusted for all other SEP indicators;

Significant associations are bold.

3.3. Districts and caries

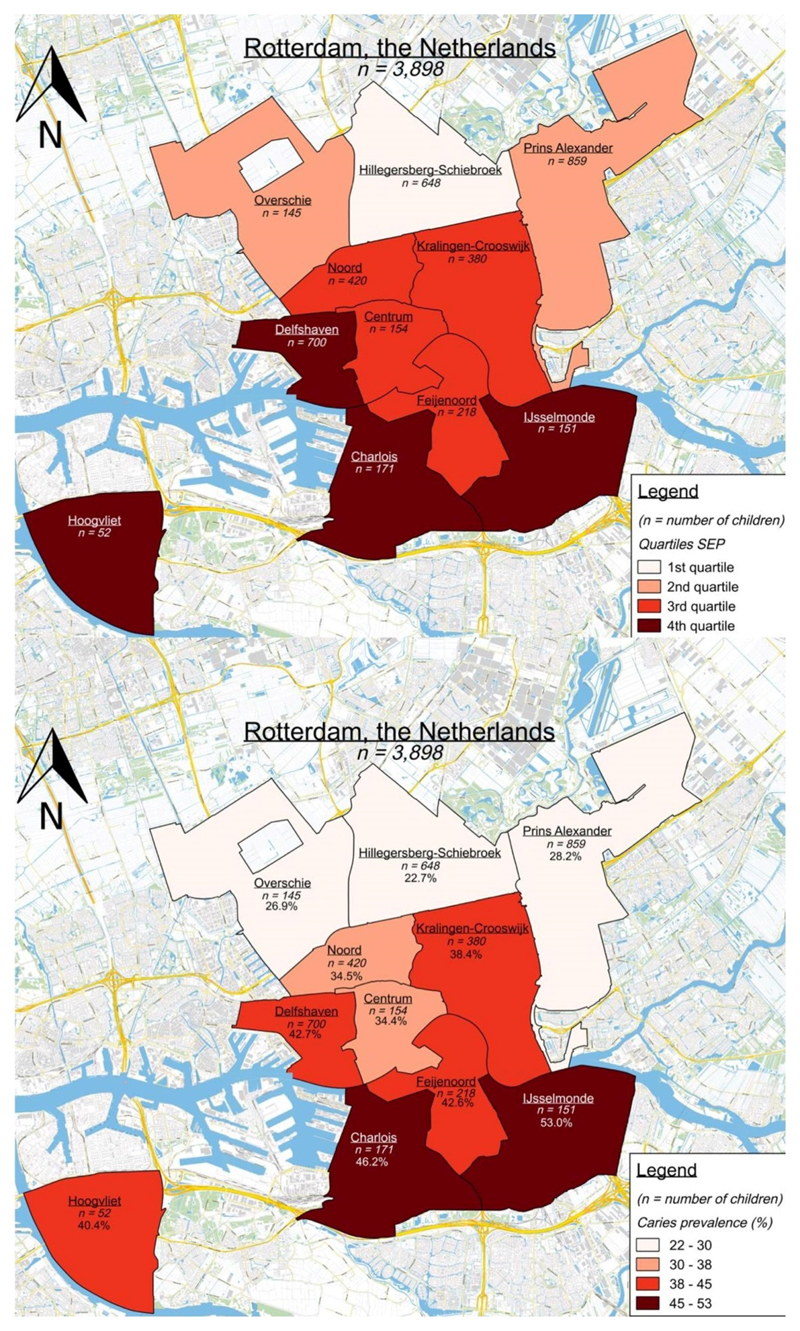

The greatest differences between districts were seen in the prevalence of low parental educational levels. Based on the crude model, all odds for having a higher caries prevalence were significantly higher in socially lower ranked districts compared to Hillegersberg-Schiebroek (reference). However, significance of the associations between districts and caries disappeared after adjusting for child characteristics and all SEP indicators in the third model for almost all districts (Table 3). To visually support these findings, the social ranking and the caries prevalence of each district in the city of Rotterdam, the Netherlands are shown in figure 1.

Table 3.

Binary logistic regression for the association between districts and dental caries*

| Crude model |

Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | |

| District (n = 3,898) (n with caries / n without caries) |

dmft-index > 0 | dmft-index > 0 | dmft-index > 0 |

| 1. Hillegersberg/Schiebroek (147 / 501) |

reference | reference | reference |

| 2. Prins Alexander (242 / 617) |

1.34 [1.06 - 1.69] |

1.23 [0.97 - 1.57] |

1.03 [0.80 - 1.32] |

| 3. Overschie (39 / 106) |

1.25 [0.83 - 1.89] |

1.13 [0.74 - 1.71] |

0.90 [0.58 - 1.39] |

| 4. Kralingen-Crooswijk (146 / 234) |

2.13 [1.61 - 2.80] |

1.62 [1.22 - 2.16] |

1.33 [0.99 - 1.79] |

| 5. Noord (145 / 275) |

1.80 [1.37 - 2.36] |

1.37 [1.04 - 1.82] |

1.06 [0.79 - 1.42] |

| 6. Centrum (53 / 101) |

1.79 [1.22 - 2.62] |

1.32 [0.89 - 1.96] |

0.98 [0.65 - 1.48] |

| 7. Feijenoord (92 / 126) |

2.49 [1.80 - 3.45] |

1.46 [1.03 - 2.07] |

1.12 [0.78 - 1.61] |

| 8. Delfshaven (299 / 401) |

2.54 [2.01 - 3.22] |

1.62 [1.25 - 2.10] |

1.19 [0.91 - 1.56] |

| 9. Hoogvliet (21 / 31) |

2.31 [1.29 - 4.14] |

1.43 [0.78 - 2.62] |

1.08 [0.58 - 2.02] |

| 10. IJsselmonde (80 / 71) |

3.84 [2.66 - 5.55] |

2.45 [1.67 - 3.60] |

1.85 [1.24 - 2.76] |

| 11. Charlois (79 / 92) |

2.93 [2.06 - 4.16] |

1.66 [1.37 - 2.01] |

1.21 [0.83 - 1.79] |

Districts were ranked from lowest prevalence of SEP indicators, that are associated with dental caries, to highest prevalence.

Model 2 = Adjusted for age, sex, and child’s ethnicity.

Model 3 = Additionally adjusted for all SEP indicators (parental educational level, parental employment status, household income, single parenting, and teenage pregnancy).

Significant associations are bold.

Figure 1.

Ranking of each district (upper) and caries prevalence per district (lower)

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrate a higher caries prevalence in children with a low family SEP. Maternal education level served as the most important indicator of family SEP in the association with dental caries. Furthermore, we observed major inequalities in caries prevalence between the districts with different socioeconomic levels. However, those inequalities were mostly explained by family SEP of the population.

In agreement with other studies, we have found a higher caries prevalence in children of parents with a low educational level, without a paid job, and with a low household income [6,28]. As mentioned before different studies used diverse indicators for SEP. This lowers the comparability and may increase the chance of residual confounding. Our study is one of the first that studied all recommended indicators of family SEP in relation to dental caries simultaneously.

Schwendicke et al. [6] already proposed possible mediating pathways for the association between caries and SEP. Parents with a low education level would have worse health literacy, worse dietary and oral health behavior and lower health service utilization [6]. We did not find oral health behavior to explain the association between SEP and dental caries. Although we did not take dietary habits into account, we do believe that this plays an important role in explaining high caries prevalence among children with a low SEP. Especially, since colleagues found an association between low SEP and a more frequent “Western” dietary pattern (containing high intake of sugar-containing beverages) at the age of 14 months in our population [29]. Adherence to this more cariogenic diet may track from this age to childhood and therefore cause more caries [29–31]. Furthermore, maternal educational level was the most influential on the odds of having mild or severe caries. Recently, van den Branden et al. [32] observed more desirable oral health behavior (brushing frequency and visits to the dentist) and lower consumption of in-between sugared drinks among five-year-old children from mothers with high educational backgrounds. This was in agreement with the results of Schwendicke et al. [6]. Hence, both differences in oral health behavior and the amount of sugar consumption can be reasonable explanations for the association between parental educational levels and caries.

Interestingly, lower household income was another strong predictor of severe caries prevalence in children of our population. Costs for basic dental care are reimbursed for all children until the age of 18 in The Netherlands, according to the basic health insurance. Therefore, financial reasons probably should not play a role in parents not providing their children with adequate dental care in the Netherlands. Unlike parents from other countries, where dental care is not or only partly insured [33]. Likewise, the Dutch Central Agency for Statistics (CBS) recently observed no disparities in dental visit frequency of children between different groups of income in the Netherlands [34]. Adults with a low income, however, do tend to visit a dentist less often than adults with a higher income [34]. As a result, we speculate that their children will not visit the dentist either. Partly because of financial reasons and partly due to disinterest or ignorance. Still, dental visit in the past year at the age of six did not explain the association between dental caries and SEP in our population. Our data, however, was parent-reported and the total number of cavities and fillings can develop in more than one year. Therefore, objectifying dental health service utilization frequency over a longer time period in future research is needed to make a more valid statement.

Furthermore, social participation, support, stability, and cohesion are also influenced by SEP and may affect health [6]. Duijster et al. [35] recently found that a lower SEP was significantly associated with lower dental self-efficacy, a more external locus of control and poorer parenting practices. It is thus likely that these factors, along with other possible unmeasured and unknown mediators, play a role in the complex interaction between SEP and caries. Future research should further explore this complex interaction, so that social disparities in caries prevalence can be tackled in the future.

We have not only measured SEP on a family level, but also studied the association between district and dental caries. In correspondence with the results of Truin et al. [36], we observed a higher caries prevalence in more disadvantaged districts. Disparities between the districts in our study were mostly explained by socioeconomic differences and not by district characteristics. This finding is new and can be used by policy makers to efficiently target prevention programs. In development of preventive methods, evidence suggests not only to provide easier access to health care, but also to intervene more upstream at risks, beliefs, and behavior [37]. Suggestions for development or improvement of these interventions are provision of clear oral health education using a positive approach, early referral to a dental practice, dietary regulations at school and a multidisciplinary approach in providing parental support [35]. Further research should focus on developing the most effective methods on resolving inequalities in oral health.

During interpretation of our results, attention needs to be paid to some limitations. We have not performed an intraoral examination on the children for diagnosing dental caries, which is known as the gold standard [38]. Instead, we have used intraoral photographs. This method has shown to perform moderately [19]. Therefore, non-differential misclassification could have occurred in our data, which may have led to a possible underestimation of the association between SEP indicators and dental caries prevalence. Subsequently, use of intraoral examination would have resulted in stronger associations. Furthermore, occurrence of response bias could not have been completely avoided due to the use of questionnaires. Especially for the parent-reported oral health behavior questions it is likely that we received socially desirable answers. Although we were able to adjust for a broad range of confounding factors, residual confounding should still be considered. The municipality of Rotterdam published for each district a social index score based on capacities, living environment, participation, and social bonding [39]. However, we made a ranking of the districts ourselves. This turned out to be representative of the ranking of the municipality of Rotterdam, the Netherlands, except for Hoogvliet [39]. Therefore, caution needs to be taken when interpreting the results for this district. As a final point, use of a multilevel model would have given us the association between SEP and caries independent of district characteristics. Influence of district characteristics on the caries distribution, however, was not likely from the logistic regression analysis. Therefore, we chose not to perform a multilevel logistic regression analysis for our study.

The major strength of this study was the large population of children with different socioeconomic backgrounds included. Furthermore, we performed adequate statistical methods and considered different approaches to answer our research questions. Another strength is that we have also included SEP on a community level per district. Geo-mapping of these results gave us a clear insight of where the disparities are the greatest and where preventive strategies should be targeted at.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, dental caries is more prevalent among children with a lower SEP and this is even visible at the district level. The magnitude of inequalities in oral health among districts was previously unknown and should be unacceptable in a developed country such as The Netherlands. These new findings will help the development of health strategies to be better targeted and to efficiently reduce caries prevalence. Future research should address the pathways that are responsible for the high prevalence of dental caries among socially disadvantaged groups.

Supplementary Material

References

- [1].Gomes MC, Pinto-Sarmento TC, Costa EM, Martins CC, Granville-Garcia AF, Paiva SM. Impact of oral health conditions on the quality of life of preschool children and their families: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:55. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kragt L, van der Tas JT, Moll HA, Elfrink ME, Jaddoe VW, Wolvius EB, et al. Early Caries Predicts Low Oral Health-Related Quality of Life at a Later Age. Caries Res. 2016;50(5):471–479. doi: 10.1159/000448599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Flaxman A, Naghavi M, Lopez A, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res. 2013;92(7):592–597. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Slobbe LCJ, Smit JM, Groen J, Poos MJJC, Kommer GJ. Costs of illness in the Netherlands 2007; trends in Dutch health expenditures 1999-2010. [accessed 31.10.2016];2011 www.rivm.nl/dsresource?objectid=rivmp:61294&type=org&disposition=inline&ns_nc=1.

- [5].Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, Bloomer E, Goldblatt P Consortium for the European Review of Social Determinants of Health and the Health Divide. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380(9846):1011–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Schwendicke F, Dörfer CE, Schlattmann P, Foster Page L, Thomson WM, Paris S. Socioeconomic inequality and caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2015;94(1):10–18. doi: 10.1177/0022034514557546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Christensen LB, Twetman S, Sundby A. Oral health in children and adolescents with different socio-cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68(1):34–42. doi: 10.3109/00016350903301712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Maliderou M, Reeves S, Noble C. The effect of social demographic factors, snack consumption and vending machine use on oral health of children living in London. Br Dent J. 2006;201(7):441–444. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4814072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pieper K, Dressler S, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Neuhäuser A, Krecker M, Wunderlich K, et al. The influence of social status on pre-school children's eating habits, caries experience and caries prevention behavior. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(1):207–215. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schuller AA, van Dommelen P, Poorterman JH. Trends in oral health in young people in the Netherlands over the past 20 years: a study in a changing context. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2014;42(2):178–184. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Truin GJ, Frencken JE, Mulder J, Kootwijk AJ, de Jong E. Prevalentie van tandcariës en tanderosie bij Haagse schoolkinderen in de periode 1996-2005. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2007;114:335–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Verrips GH, Kalsbeek H, Eijkman MA. Ethnicity and maternal education as risk indicators for dental caries, and the role of dental behavior. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21(4):209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(1):7–12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kämppi A, Tanner T, Päkkilä J, Patinen P, Järvelin MR, Tjäderhane L, et al. Geographical distribution of dental caries prevalence and associated factors in young adults in Finland. Caries Res. 2013;47(4):346–354. doi: 10.1159/000346435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Priesnitz MC, Celeste RK, Pereira MJ, Pires CA, Feldens CA, Kramer PF. Neighbourhood Determinants of Caries Experience in Preschool Children: A Multilevel Study. Caries Res. 2016;50(5):455–461. doi: 10.1159/000447307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Duijster D, van Loveren C, Dusseldorp E, Verrips GH. Modelling community, family, and individual determinants of childhood dental caries. Eur J Oral Sci. 2014;122(2):125–133. doi: 10.1111/eos.12118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kooijman MN, Kruithof CJ, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, van IJzendoorn MH, de Jongste JC, et al. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update 2017. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(12):1243–1264. doi: 10.1007/s10654-016-0224-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schaart R, Westerman S, Moens MB. The Dutch standard classification of education SOI 2006. [accessed 01.10.2016];Statistics Netherlands. 2008 www.cbs.nl/en-gb/background/2008/24/the-dutch-standard-classification-of-education-soi-2006.

- [19].Elfrink ME, Veerkamp JS, Aartman IH, Moll HA, Ten Cate JM. Validity of scoring caries and primary molar hypomineralization (DMH) on intraoral photographs. JM Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009;10(Suppl.1):5–10. doi: 10.1007/BF03262693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Landis JR, Koch GG. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schuller AA, van Kempen IPF, Poorterman JHG, Verrips GHW. Kies voor tanden: Een onderzoek naar mondgezondheid en preventief tandheelkundig gedrag van jeugdigen. [accessed 05.09.2016];2013 www.tno.nl/media/1167/kiesvoortanden_tnols2013r10056.pdf.

- [22].CBS. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek: Jaarrapport Integratie 2014. [accessed 10.10.2016];2014 http://www.cbs.nl/NR/rdonlyres/4735C2F5-C2C0-49C0-96CB-0010920EE4A4/0/jaarrapportintegratie2014pub.pdf.

- [23].Elfrink ME, Schuller AA, Veerkamp JS, Poorterman JH, Moll HA, ten Cate BJ. Factors increasing the caries risk of second primary molars in 5-year-old Dutch Children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20(2):151–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2009.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-care databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med. 1991;10(4):585–598. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294(22):2879–2888. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cheng TL, Goodman E. Committee on Pediatric Research, Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in research on child health. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e225–237. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Christensen L, Twetman S, Sundby A. P Oral health in children and adolescents with different socio-cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68(1):34–42. doi: 10.3109/00016350903301712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kiefte-de Jong JC, de Vries JH, Bleeker SE, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Raat H, et al. Socio-demographic and lifestyle determinants of 'Western-like' and 'Health conscious' dietary patterns in toddlers. Br J Nutr. 2013;109(1):137–147. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512000682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Peres MA, Sheiham A, Liu P, Demarco FF, Silva AE, Assunção MC, et al. Sugar Consumption and Changes in Dental Caries from Childhood to Adolescence. J Dent Res. 2016;95(4):388–394. doi: 10.1177/0022034515625907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sohn W, Burt BA, Sowers MR. Carbonated soft drinks and dental caries in the primary dentition. J Dent Res. 2006;85(3):262–266. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].van den Branden S, van den Broucke S, Leroy R, Declerck D, Hoppenbrouwers K. Oral health and oral health-related behaviour in preschool children: evidence for a social gradient. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(2):231–237. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1874-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Griffin SO, Barker LK, Wei L, Li CH, Albuquerque MS, Gooch BF. Use of dental care and effective preventive services in preventing tooth decay among U.S. Children and adolescents--Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, United States, 2003-2009 and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2005-2010. MMWR Suppl. 2014;63(2):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].CBS. Met hoger inkomen meer naar tandarts en mondhygiënist. [accessed 20.08.2016];2016 https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2016/11/met-hoger-inkomen-meer-naar-tandarts-en-mondhygienist.

- [35].Duijster D, de Jong-Lenters M, de Ruiter C, Thijssen J, van Loveren C, Verrips E. Parental and family-related influences on dental caries in children of Dutch, Moroccan and Turkish origin. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43(2):152–162. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Truin GJ, Frencken JE, Mulder AJ, Kootwijk AJ, de Jong E. Tandcariës en tanderosie bij de Haagse schooljeugd in de periode 2002-2008. Epidem Bull. 2009;44(1):2–9. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Steele J, Shen J, Tsakos G, Fuller E, Morris S, Watt R, et al. The Interplay between socioeconomic inequalities and clinical oral health. J Dent Res. 2015;94(1):19–26. doi: 10.1177/0022034514553978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gimenez T, Piovesan C, Braga MM, Raggio DP, Deery C, Ricketts DN, et al. Visual Inspection for Caries Detection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2015;94(7):895–904. doi: 10.1177/0022034515586763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Vleugels W, van Gelder J, van Doveren T, Koppelaar P, Ergun C, van Dun L. Rotterdam sociaal gemeten: 3e meting Sociale Index. [accessed 05.08.2016];2010 http://www.rotterdam.nl/COS/publicaties/Vanaf%202005/09-3100.Sociale%20Index%202010.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.