Abstract

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease, is a fatal neurodegenerative disease. Neuromuscular respiratory failure is the most common cause of death, which usually occurs within two to five years of the disease onset. Supporting respiratory function with mechanical ventilation may improve survival and quality of life. This is the second update of a review first published in 2009.

Objectives

To assess the effects of mechanical ventilation (tracheostomy‐assisted ventilation and non‐invasive ventilation (NIV)) on survival, functional measures of disease progression, and quality of life in ALS, and to evaluate adverse events related to the intervention.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Neuromuscular Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL Plus, and AMED on 30 January 2017. We also searched two clinical trials registries for ongoing studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs involving non‐invasive or tracheostomy‐assisted ventilation in participants with a clinical diagnosis of ALS, independent of the reported outcomes. We included comparisons with no intervention or the best standard care.

Data collection and analysis

For the original review, four review authors independently selected studies for assessment. Two review authors reviewed searches for this update. All review authors independently extracted data from the full text of selected studies and assessed the risk of bias in studies that met the inclusion criteria. We attempted to obtain missing data where possible. We planned to collect adverse event data from the included studies.

Main results

For the original Cochrane Review, the review authors identified two RCTs involving 54 participants with ALS receiving NIV. There were no new RCTs or quasi‐RCTs at the first update. One new RCT was identified in the second update but was excluded for the reasons outlined below.

Incomplete data were available for one published study comparing early and late initiation of NIV (13 participants). We contacted the trial authors, who were not able to provide the missing data. The conclusions of the review were therefore based on a single study of 41 participants comparing NIV with standard care. Lack of (or uncertain) blinding represented a risk of bias for participant‐ and clinician‐assessed outcomes such as quality of life, but it was otherwise a well‐conducted study with a low risk of bias.

The study provided moderate‐quality evidence that overall median survival was significantly different between the group treated with NIV and the standard care group. The median survival in the NIV group was 48 days longer (219 days compared to 171 days for the standard care group (estimated 95% confidence interval 12 to 91 days, P = 0.0062)). This survival benefit was accompanied by an enhanced quality of life. On subgroup analysis, in the subgroup with normal to moderately impaired bulbar function (20 participants), median survival was 205 days longer (216 days in the NIV group versus 11 days in the standard care group, P = 0.0059), and quality of life measures were better than with standard care (low‐quality evidence). In the participants with poor bulbar function (21 participants), NIV did not prolong survival or improve quality of life, although there was significant improvement in the mean symptoms domain of the Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index by some measures. Neither trial reported clinical data on intervention‐related adverse effects.

Authors' conclusions

Moderate‐quality evidence from a single RCT of NIV in 41 participants suggests that it significantly prolongs survival, and low‐quality evidence indicates that it improves or maintains quality of life in people with ALS. Survival and quality of life were significantly improved in the subgroup of people with better bulbar function, but not in those with severe bulbar impairment. Adverse effects related to NIV should be systematically reported, as at present there is little information on this subject. More RCT evidence to support the use of NIV in ALS will be difficult to generate, as not offering NIV to the control group is no longer ethically justifiable. Future studies should examine the benefits of early intervention with NIV and establish the most appropriate timing for initiating NIV in order to obtain its maximum benefit. The effect of adding cough augmentation techniques to NIV also needs to be investigated in an RCT. Future studies should examine the health economics of NIV. Access to NIV remains restricted in many parts of the world, including Europe and North America. We need to understand the factors, personal and socioeconomic, that determine access to NIV.

Plain language summary

Mechanical ventilation for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease

Review question

Does mechanical ventilation improve the survival of people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)? How does it affect disease progression and quality of life, and does it have any unwanted effects?

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as motor neuron disease, is a condition in which nerves that control movement are lost. Management of ALS has evolved rapidly in the last 10 years. Although there is still no cure, some treatments can help manage symptoms. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis causes progressive muscle weakness, including weakness of the muscles used in breathing. Failure of ventilation (the capacity to move air in and out of the lungs) is an important cause of death in ALS. Mechanical ventilation is a method in which machines support the person's breathing. Mechanical ventilation may be invasive or non‐invasive. Invasive ventilation involves insertion of a tube into the throat (tracheostomy). Non‐invasive ventilation (NIV) is a method of helping people breathe that does not require a tracheostomy. Non‐invasive ventilation supports breathing via a mask on the face or nose that is connected via tubing to a small portable ventilator.

Study characteristics

In this updated review, we examined the evidence from two randomised trials of NIV in ALS involving a total of 54 participants. One of the trials, which studied when to start NIV, provided no usable data. A third trial, identified in a clinical trials register, currently has no published results.

Key results and quality of the evidence

Complete data were only available from a single trial of 41 participants. The results of this trial provided moderate‐quality evidence that NIV significantly prolongs survival, and low‐quality evidence that it improves or maintains quality of life compared to standard care. Median survival was increased by an estimated 48 days, from 171 to 219 days. The survival benefit from NIV was much greater in people with ALS in whom the muscles used for speaking, chewing, and swallowing (bulbar muscles) were either unaffected or only moderately weak. Among these 20 participants, the median survival with NIV was increased by an estimated 205 days (216 days with NIV, compared to 11 days with standard care). Quality of life was also maintained in participants with mild to moderate bulbar weakness. In the 21 participants with severe bulbar weakness, NIV did not prolong survival or maintain quality of life scores, although a sleep‐related symptoms score improved. Neither trial reported on adverse effects. Participants and clinicians were aware of the treatment groups, which can influence quality of life assessments.

More trials of NIV versus standard care in ALS are unlikely as it would not be ethical to withhold NIV. Future studies should examine early intervention with NIV and determine the best time to start it.

The evidence is up to date to January 2017.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Non‐invasive ventilation compared with standard care for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

| Non‐invasive ventilation compared with standard care for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with ALS Settings: people with ALS attending a single regional care centre Intervention: non‐invasive ventilation Comparison: standard care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard care | Non‐invasive ventilation (NIV) | |||||

| Survival |

All participants Median survival was 171 days. |

All participants Median survival was 48 days longer (12 to 91 days1 longer). |

‐ | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 |

21 of the 41 participants had poor bulbar function. P = 0.0059 better bulbar function, P = 0.92 poor bulbar function |

|

Participants with better (good or moderately impaired) bulbar function Median survival was 11 days. |

Participants with better (good or moderately impaired) bulbar function Median survival was 205 days longer (CI not given). |

|||||

|

Participants with poor bulbar function Median survival was 261 days. |

Participants with poor bulbar function Median survival was 39 days shorter (CI not given). |

|||||

| Quality of life (SF‐36 MCS) |

All participants Median duration that SF‐36 MCS remained above 75% of baseline was 99 days. |

All participants Median duration that SF‐36 MCS remained above 75% of baseline was 69 days longer (45 to 667 days longer). |

‐ | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2,3 |

‐ |

|

Participants with better (good or moderately impaired) bulbar function Median duration that SF‐36 MCS remained above 75% of baseline was 4 days. |

Participants with better (good or moderately impaired) bulbar function Median duration that SF‐36 MCS remained above 75% of the baseline was 195 days longer (P = 0.001, CI not given). |

|||||

|

Participants with poor bulbar function Median duration that SF‐36 MCS remained above 75% of baseline was 164 days. |

Participants with poor bulbar function Median duration that SF‐36 MCS remained above 75% of the baseline was 37 days shorter (P = 0.64, CI not given). |

|||||

| Quality of life (SF‐36 PCS) |

All participants Median duration that SF‐36 PCS remained above 75% of baseline was 81 days. |

All participants Median duration that SF‐36 PCS remained above 75% of baseline was 69 days longer (P = 0.004). |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | CI not given |

|

Participants with better (good or moderately impaired) bulbar function Median duration that SF‐36 PCS remained above 75% of baseline was 4 days. |

Participants with better (good or moderately impaired) bulbar function Median duration that SF‐36 PCS remained above 75% of the baseline was 175 days longer (P < 0.001). |

|||||

|

Participants with poor bulbar function Median duration that SF‐36 PCS remained above 75% of baseline was 132 days. |

Participants with poor bulbar function Median duration that SF‐36 PCS remained above 75% of the baseline was 18 days longer (P = 0.88). |

|||||

| Quality of life (SAQLI) |

All participants Median duration that SAQLI remained above 75% of baseline was 99 days. |

All participants Median duration that SAQLI remained above 75% of baseline was 74 days longer (P = 0.031). |

‐ | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2,3 |

CI not given |

|

Participants with good or moderately impaired bulbar function Median duration that SAQLI remained above 75% of baseline was 4 days. |

Participants with good or moderately impaired bulbar function Median duration that SAQLI remained above 75% of the baseline was 195 days longer (P = < 0.001). |

|||||

|

Participants with poor bulbar function Median duration that SAQLI remained above 75% of baseline was 132 days. |

Participants with poor bulbar function Median duration that SAQLI remained above 75% of the baseline was 29 days shorter (P = 0.77). |

|||||

| Adverse events (not reported) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; SAQLI: Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index; SF‐36 MCS: 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey Mental Component Summary; SF‐36 PCS: 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey Physical Component Summary | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Calculated CIs are approximate. 2We assessed the evidence as of moderate quality, as it was based on a single randomised trial of 41 participants. 3For quality of life outcomes, we further downgraded the evidence due to lack of blinding.

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease (MND), is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterised by loss of upper and lower motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord (Brooks 1994; Brooks 2000). The incidence of ALS is 1 to 2 per 100,000 of the population, and the age‐specific incidence and mortality rates peak at 55 to 75 years (Worms 2001). The average life expectancy is two to three years from the onset of symptoms, although 10% of people with ALS may survive for 10 years or more (Haverkamp 1995; Turner 2003). Death usually results from respiratory failure due to denervation weakness in respiratory muscles. Respiratory muscle function at any time point during the disease trajectory is the most important predictor of survival and an important predictor of quality of life (Bach 1995; Haverkamp 1995; Vitacca 1997; Stambler 1998; Fitting 1999; Chaudri 2000; Bourke 2001; Lyall 2001a; Varrato 2001; Lechtzin 2002). Measures of respiratory muscle strength (e.g. forced vital capacity and sniff nasal inspiratory pressure) are useful in monitoring the progression of respiratory muscle weakness, but no single test of respiratory function can reliably predict the onset of respiratory failure. Furthermore, respiratory function tests have limitations in people with bulbar weakness, who cannot blow effectively (Lyall 2001a).

Assisted ventilation has long been used to support ventilation in respiratory failure (Annane 2014). Assisted ventilation can be provided by invasive (tracheostomy ventilation (TV)) and non‐invasive (NIV) means. Tracheostomy ventilation can prolong survival for many years (Bach 1993; Cazzolli 1996), but it is resource‐intensive and risks ventilator entrapment, which exacts a significant emotional toll on people with ALS and their carers (Moss 1993; Cazzolli 1996; Moss 1996). Tracheostomy ventilation may prolong life in the face of increasing disability and dependency, and hence quality of life may not be sustained. Nevertheless, people affected by ALS are increasingly aware of this option. Tracheostomy ventilation in ALS is not encouraged in Europe and North America (Hayashi 1997; Borasio 1998; Yamaguchi 2001). In Japan, however, TV is the predominant form of ventilation offered to people with ALS, and the cost is fully covered by the government and medical insurance (Kawata 2008).

Non‐invasive ventilation is another option for treating respiratory failure in people with ALS. Non‐invasive ventilation utilises a face or nasal mask and a volume‐cycled or bilevel pressure‐limited ventilator to provide an intermittent positive pressure to support ventilation. Until the turn of the century, the use of NIV varied greatly across North America and Europe (Melo 1999; Borasio 2001; Bradley 2001; Cedarbaum 2001; Chio 2001; Bourke 2002). Evidence from several retrospective and some prospective studies indicated that NIV may be associated with gain in survival (Pinto 1995; Aboussouan 1997; Kleopa 1999; Bach 2002), improved quality of life (Hein 1997; Hein 1999; Aboussouan 2001; Bourke 2001; Jackson 2001; Lyall 2001b), and improved cognitive function (Newsom‐Davis 2001). People with ALS who have little or no bulbar muscle weakness may tolerate NIV better than those with significant bulbar involvement (Cazzolli 1996; Aboussouan 1997). In the absence of a randomised controlled trial (RCT), uncertainties remained over the benefits and unwanted effects of TV and NIV.

Annane 2014, a Cochrane Review of nocturnal mechanical ventilation for a mixed group of people with chronic hypoventilation, identified eight randomised trials, three of which involved people with ALS. This review concluded that nocturnal ventilation may relieve chronic hypoventilation‐related symptoms and prolong survival, but that the quality of the studies was poor and the benefit of long‐term mechanical ventilation should be confirmed in further trials. The evidence was thought to be strongest for NIV in people with ALS.

Over the past few years, the use of NIV in ALS has greatly increased (O'Neill 2012). An RCT evaluated the effects of NIV on survival and quality of life in people with ALS (Bourke 2006). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence UK (NICE) has published guidelines on the use of NIV in people with ALS (NICE 2010). The aim of this review was to assimilate the evidence for mechanical ventilation in ALS and to assess the benefits and unwanted effects of TV and NIV. The conclusions of Radunovic 2009, the original version of this review, were based on the results of this single study of 41 participants (Bourke 2006), as the other available study provided no usable data (Jackson 2001). For this 2017 update, we identified no new RCTs or quasi‐RCTs.

Objectives

To assess the effects of mechanical ventilation (tracheostomy‐assisted ventilation and non‐invasive ventilation) on survival, functional measures of disease progression, and quality of life in ALS, and to evaluate adverse events related to the intervention.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All RCTs and quasi‐RCTs involving NIV or TV. Quasi‐RCTs are trials where treatment allocation was intended to be random but may have been biased (e.g. alternate allocation or allocation according to the day of the week). We selected studies independently of reported outcomes.

Types of participants

People with a clinical diagnosis of ALS/MND (pure mixed upper motor neuron and lower motor neuron degeneration with supportive electromyogram) according to the El Escorial criteria (Brooks 1994; Brooks 2000), at any stage of disease and with any clinical pattern of the condition (e.g. bulbar and limb onset). Subgroups of interest were participants with or without significant bulbar symptoms as categorised by the authors of the papers reviewed.

We did not consider trials of mixed neuromuscular or chest wall conditions, which are included in a separate review (Annane 2014).

Types of interventions

All forms of NIV (irrespective of pressure settings and timings) and TV, compared to no intervention or the best standard care.

Types of outcome measures

Our outcomes were not selection criteria, but rather a list of outcomes of interest within included studies.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was overall survival after initiation of assisted ventilation, as assessed by a pooled hazard ratio using life table/Cox regression methods to combine disparate periods of observation from all studies. This would have been supplemented where possible by pooled estimates of the 75%, 50% (median) survival times and confidence intervals (CIs). This is to allow for the situation where the proportional hazards assumption, necessary for Cox regression, has not been met.

Secondary outcomes

Survival at one month and six months or longer.

Quality of life assessed using validated health status questionnaires, e.g. 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) at one month and six months or longer (Lyall 2001b).

Any validated functional rating scale, such as the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS) or the ALSFRS‐Revised (ALSFRS 1996; Cedarbaum 1999), Norris (Norris 1974), or Appel scales at one month and six months or longer (Haverkamp 1995).

The proportion of people experiencing adverse events related to mechanical ventilation. We would have considered adverse events in two categories. The first category would have included the proportion of participants experiencing any adverse event attributed to ventilation (e.g. fistulae, pneumothorax, bleeding, local infection, hospitalisation, or death), and the second category would have included participants experiencing severe complications of mechanical ventilation, including life‐threatening episodes, prolonged hospitalisation, and death.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the following databases:

the Cochrane Neuromuscular Specialised Register (30 January 2017) (Appendix 1);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (30 January 2017, in the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO)) (Appendix 2);

MEDLINE (1966 to 30 January 2017) (Appendix 3);

Embase (1980 to 30 January 2017) (Appendix 4);

CINAHL Plus (1937 to 30 January 2017) (Appendix 5);

AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database) (1985 to 30 January 2017) (Appendix 6).

We also searched for ongoing or unpublished trials on 1 February 2017 in:

the US National Institutes of Health trials registry ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (Appendix 7);

the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (Appendix 8).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the original review, all four review authors (AR, DA, KJ, NM) checked titles and abstracts identified by the searches for RCTs or quasi‐RCTs, and two review authors (MKR and DA) reviewed the searches for the update. We obtained the full texts of all potentially relevant studies, which the review authors independently assessed.

Data extraction and management

All review authors independently extracted data onto a specially designed form. We tried to obtain missing or additional data from the study authors wherever possible. For our primary outcome, overall survival after initiation of assisted ventilation, we planned to extract hazard ratios with standard errors or confidence intervals (CIs), or median survival times with 95% CIs, or the numbers required to construct a life table, for example the numbers surviving or failing to survive after initiation of assisted ventilation for a sequence of specified time intervals.

In any studies requiring translation, the translator would extract data directly onto a data extraction form. If possible, the review authors would have checked any numerical data extraction against the study report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All review authors decided which trials met the inclusion criteria for the review and assessed the risk of bias for the included studies. Any disagreements about inclusion were resolved by discussion between review authors. We completed a 'Risk of bias' assessment for all included studies according to the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We evaluated random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (participants and personnel, and outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. We then made a judgement on each of these criteria of 'high risk', 'low risk', or 'unclear risk', where 'unclear risk' indicates an unclear or unknown risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

In Appendix 9 we have reported in full methods that the review authors will follow if more trials become available in the future and meta‐analysis becomes possible.

'Summary of findings' table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table using the following outcomes.

Length of survival following initiation of mechanical ventilation.

Quality of life.

Adverse events.

We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence (studies that contribute data for the prespecified outcomes). We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We used footnotes to justify all decisions to down‐ or upgrade the quality of the evidence and made comments to aid readers' understanding of the review where necessary.

We reported summary scores for quality of life outcomes. We reported the median days at which quality of life remained above 75% of baseline in the 'Summary of findings' table, as raw scores were not available, and of the two quality of life analyses reported in Bourke 2006, this is more easily interpreted.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted investigators in order to verify key study characteristics and to obtain missing numerical outcome data.

Assessment of reporting biases

Our search strategies were comprehensive. For this update, we searched trials registries to identify any completed but unpublished trials.

We considered non‐randomised evidence related to adverse events, cost, and cost‐effectiveness of different forms of mechanical ventilation in the Discussion.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

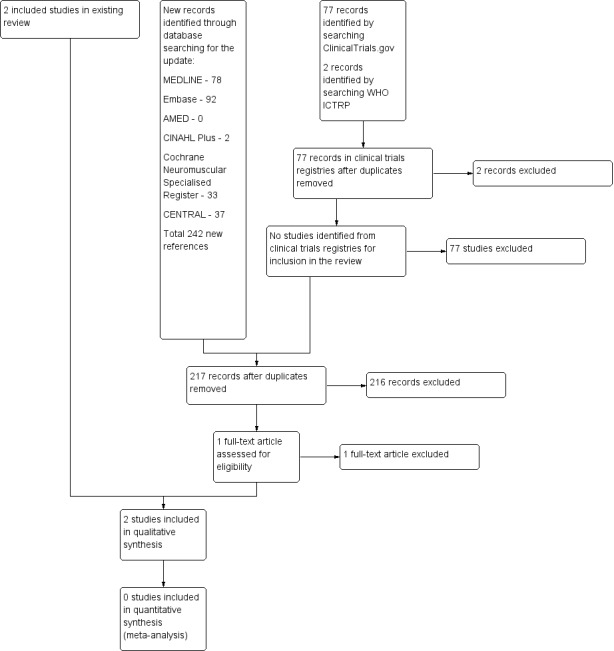

The updated database searches for this update produced the following results: MEDLINE 224 (78 new references), Embase 190 (92 new), AMED 6 (1 new), CINAHL 11 (2 new), Cochrane Neuromuscular Specialised Register 66 (33 new), and CENTRAL 63 (37 new). We reviewed 242 new references from database searches for this update, with 217 after deduplication, but none were eligible for inclusion. We also reviewed 77 records in ClinicalTrials.gov and 2 records in WHO ICTRP. See Figure 1 for a flow chart of the study selection process.

1.

A flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

We also searched the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (4 references), Health Technology Assessment database (4 references), and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (3 references) for information for inclusion in the Discussion.

Included studies

All review authors agreed on the inclusion of two studies (Jackson 2001; Bourke 2006).

The first study was a prospective randomised three‐month study in three ALS centres in the USA (Jackson 2001). The study included 20 people with ALS (no age or sex provided), of whom 13 were randomised when overnight oximetry studies documented oxygen saturation below 90% for at least one cumulative minute throughout the duration of the study (a minimum of six hours) and the individual had at least two significant symptoms of nocturnal hypoventilation. There were two groups: an early group where the participants were started immediately on NIV (seven participants) and a late group (six participants) in whom NIV was initiated when forced vital capacity (FVC) was less than 50% predicted. The report provided no demographic characteristics for the participants. The effects of NIV on ALSFRS respiratory version, Pulmonary Symptom Scale, and SF‐36 were estimated. No survival data were available from this study.

The second study was an RCT performed in a single ALS centre in the UK. It included 92 participants, of whom 41 met the criteria for randomisation (orthopnoea or maximum inspiratory pressures less than 60% or symptomatic hypercapnia, or both) and were followed up for at least 12 months or until death (Bourke 2006). Random allocation was computer generated by minimisation, a process that allows all significant prognostic factors to be included in the model. Twenty‐two participants were assigned to the NIV group and 19 participants to the standard care group. Demographic and functional characteristics of the participants in the two groups were similar at randomisation (Characteristics of included studies). The effect of NIV on survival and quality of life outcome domains (e.g. SF‐36 and the Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index (SAQLI)) was estimated in the whole cohort but also in the subgroups of participants with and without severe impairment of bulbar function. Trialists defined severe impairment as a score of three or less on a simple six‐point assessment scale.

Excluded studies

We excluded one study that was terminated early due to problems recruiting participants (Perez 2003). We excluded Pinto 2003 as it used historical controls. One study was a controlled study of exercise in people with ALS with respiratory insufficiency (Pinto 1999). One study was an anecdotal study (Sivak 1982). Twelve studies were retrospective (Goulon 1989; Kamimoto 1989; Bach 1993; Cazzolli 1996; David 1997; Buhr‐Schinner 1999; Kleopa 1999; Saito 1999; Cedarbaum 2001; Winterholler 2001; Lo Coco 2007; Shoesmith 2007), of which only Kleopa 1999 had a control group. Six studies were non‐randomised prospective observational studies (Pinto 1995; Aboussouan 1997; Lyall 2001b; Newsom‐Davis 2001; Lo Coco 2006; Mustfa 2006). Berlowitz 2016 was a cohort study examining the effects of NIV on pulmonary function decline and survival across MND/ALS phenotypes.

Pinto 1995 was a single‐centre study in Portugal that included 20 consecutive participants with bulbar features and probable or definite ALS according to El Escorial criteria. The first 10 participants were treated with oxygen, bronchodilators, and physiotherapy. The following 10 participants were submitted to bilevel positive airway pressure. Two participants were excluded, one in the first group because the participant had tracheostomy, and the other in the second group for refusing the treatment. Despite the limitation of small sample size, the study demonstrated a significant improvement in total survival time (P < 0.004) and in the survival from the onset of diurnal gas exchange disorder (P < 0.006). Although it was a controlled trial, participants were not randomised, and hence selection bias cannot be excluded.

A 2016 study looked at the early initiation of NIV within a sham and an interventional arm (Jacobs 2016). It essentially compared 4 cm continuous positive airway pressure against bilevel ventilation at 8/4 cmH2O at a stage at which NIV would not normally be used. The two groups used NIV (or sham) for only 2.0 hours/day and 3.3 hours/day, respectively. The reported outcome was decline in percentage predicted FVC during the follow‐up period. Once both groups reached the time when they met the standard criteria for starting NIV, both groups were offered NIV. There was no difference in the survival of the two groups. The review authors considered that the main objective of this study was to assess the benefits of early initiation of NIV, and the trial did not evaluate NIV against no intervention, therefore we could not consider this data as complementary to the objectives of this review.

We excluded four apparently unpublished trials in clinical trials registries that compared different settings, modes, or timings of NIV (NCT00537446; NCT00560287; NCT01363882; NCT01641965). We excluded an ongoing trial in which different modes of ventilation were to be compared (NCT01746381). We enquired about two further registry entries from investigators. The contact person for NCT00958048 informed us that because participants were not willing to be randomised, investigators converted the trial to an observational study, which was not eligible for this review. An investigator of NCT00386464 reported that the trial had recruitment problems and was neither completed nor published.

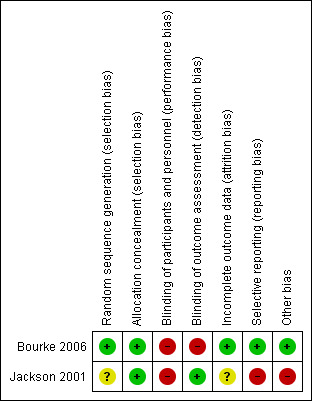

Risk of bias in included studies

For a 'Risk of bias' summary see Figure 2.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study. A green plus sign indicates low risk of bias; a red minus sign indicates high risk of bias; and a yellow question mark indicates unclear risk of bias.

Allocation

Allocation was adequately concealed in both included studies. Bourke 2006 performed centralised randomisation; random allocation was computer generated by the process of minimisation. Although the Jackson 2001 paper gives no data for allocation concealment, the study authors informed us that an independent statistician performed randomisation by preparing two sets of random assignment in blocks of four, which were then allocated to each centre.

Blinding

Blinding of participants was not possible in the included studies, as it was not possible to blind delivery of NIV. Outcome assessors were blinded in Jackson 2001; no information was given in Bourke 2006 as to whether outcome assessors were blinded to knowledge of allocation intervention.

Incomplete outcome data

Jackson 2001 provided data on only six participants from the early‐intervention group. The outcome of one randomised participant was not clear, and the paper provided no data for the late‐intervention group. We noted no obvious attrition bias in Bourke 2006. Thirteen participants withdrew during surveillance, but none withdrew after randomisation, and all participants were followed up until the end of the study or death.

Selective reporting

Bourke 2006 was free of the suggestion of selective outcome reporting, as the study protocol was available, and the trial authors reported all primary and secondary outcomes in the prespecified way. No study protocol was available for Jackson 2001. The results of Jackson 2001 were intended to be used as preliminary data, but unfortunately the investigators did not secure funding for a subsequent study.

Other potential sources of bias

In Jackson 2001, trial authors did not define nocturnal hypoventilation according to the universally accepted criteria; they accepted oxygen desaturation below 90% for at least one cumulative minute as evidence of nocturnal hypoventilation. Nocturnal oximetry showing oxygen desaturation below 88% for at least five consecutive minutes or oxygen saturation below 90% for more than 5% of sleep time are considered sufficient to initiate NIV (Mehta 2001).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Both included studies used NIV.

Jackson 2001 provided insufficient data to be included in meta‐analyses, and this prevented pooled analysis of either primary or secondary outcome measures. Our review was therefore based on the results of one study, Bourke 2006. Neither were we able to obtain individual participant data or life tables from the Bourke 2006 trialists.

Primary outcome

Bourke 2006 showed that the overall median survival after initiation of assisted ventilation was significantly different between the NIV and standard care groups (P = 0.0062). The median survival for the NIV group participants was 48 days longer than the standard care group participants (219 days compared to 171 days). The published information did not provide a 95% confidence interval (CI) for the median survival difference (48 days) or for our secondary outcomes. We were able to derive approximate CIs from P values and median survival estimates under an assumption that median survival follows a lognormal distribution. A statistical method based on a lognormal survival model gave the following estimates for the 95% CI: 12 to 91 days for the estimated 48‐day survival difference (private communication from statistical referee Dan Moore).

The overall median survival of the subgroup with better (good or moderately impaired) bulbar function was also significantly different in the NIV group (P = 0.0059), with NIV group participants surviving 205 days longer than the standard care group participants (median 216 days in NIV group versus 11 days in the standard care group).

In participants with poor bulbar function, NIV did not confer survival advantage (P = 0.92), with an overall median survival for NIV group participants of 39 days less than the standard care group (222 versus 261 days). We considered the quality of the survival evidence as moderate, as it was based on a single RCT (see Table 1).

Secondary outcomes

1. Survival at one or six months or longer

No data were available for survival at one and six months.

2. Quality of life assessed using validated health status questionnaires at one and six months or longer

No data were available at one and six months for either study.

Jackson 2001 did not systematically report quality of life data.

Bourke 2006 reported the time SAQLI and SF‐36 scores were maintained above 75% of pre‐randomisation assessment, and time‐weighted mean improvements in SF‐36 and sleep‐related SAQLI (the median (range) values of AUC (area under the curve) above baseline divided by time from randomisation to death). We have reported here the summary scores but also provide the SAQLI symptoms score, which the Bourke 2006 trialists designated as primary.

Summary scores

We were unable to calculate mean difference and 95% CI from the available data. Based on interpretation of P values from two‐sided tests of significance (0.05 significance level) on intention‐to‐treat data, the median time after initiation of assisted ventilation that quality of life was maintained above 75% of the baseline, based on the SF‐36 mental component summary (MCS), Physical Component Summary (PCS), and the SAQLI score, was significantly longer with NIV than standard care in the group as a whole and in the subgroup with normal and moderately impaired bulbar function. In participants with poor bulbar function, NIV conferred no significant benefit using these measures. For numerical data, see Table 2.

1. Duration that quality of life was maintained above 75% of baseline (median days).

| All participants (n = 41) | Better bulbar function (n = 20) | Poor bulbar function (n = 21) | |||||||

| NIV (n = 22) | Standard care (n = 19) | P | NIV (n = 11) | Standard care (n = 9) | P | NIV (n = 11) | Standard care (n = 10) | P value | |

| SF‐36 MCS | 168 (45 to 1357) | 99 (0 to 690) | 0.0017 | 199 (48 to 552) | 4 (0 to 196) | 0.001 | 127 (45 to 1357) | 164 (2 to 690) | 0.64 |

| SF‐36 PCS | 150 (27 to 908) | 81 (0 to 273) | 0.0014 | 179 (36 to 548) | 4 (0 to 94) | < 0.001 | 150 (27 to 908) | 132 (2 to 273) | 0.88 |

| SAQLI symptoms | 192 (48 to 1357) | 46 (0 to 703) | 0.0013 | 205 (69 to 629) | 4 (0 to 143) | < 0.001 | 143 (48 to 1357) | 100 (2 to 703) | 0.26 |

| SAQLI score | 173 (25 to 1357) | 99 (0 to 645) | 0.031 | 199 (61 to 595) | 4 (0 to 193) | < 0.001 | 103 (25 to 1357) | 132 (2 to 645) | 0.77 |

Data are median (range). Data from Bourke 2006.

Abbreviations: NIV: non‐invasive ventilation; SAQLI: Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index; SF‐36 MCS: 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey Mental Component Summary; SF‐36 PCS: 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey Physical Component Summary

The time‐weighted mean improvement in the SF‐36 MCS score and the sleep‐related SAQLI were found to be significantly greater in the NIV group than the standard care group in the whole cohort (n = 41) and in the participants with better bulbar function (n = 20), but not in those with poor bulbar function (n = 21). The time‐weighted mean improvement in the SF‐36 PCS was greater in the participants with better bulbar function, but not in the whole group or in the subgroup with poor bulbar function. For numerical data, see Table 3.

2. Time‐weighted mean improvement in quality of life domains.

| All participants (n = 41) | Better bulbar function (n = 20) | Poor bulbar function (n = 21) | |||||||

| NIV (n = 22) | Standard care (n = 19) | P | NIV (n = 11) | Standard care (n = 9) | P | NIV (n = 11) | Standard care (n = 10) | P value | |

| SF‐36 MCS | 2.31 (0 to 11.54) | 0 (0 to 5.23) | 0.0082 | 2.18 (0 to 11.54) | 0 (0 to 1.39) | 0.0052 | 4.47 (0 to 7.75) | 0.88 (0 to 5.23) | 0.24 |

| SF‐36 PCS | 0.18 (0 to 10.62) | 0 (0 to 6.73) | 0.51 | 0.14 (0 to 10.62) | 0 (0 to 0.39) | 0.031 | 0.21 (0 to 5.41) | 0.48 (0 to 6.73) | 0.37 |

| SAQLI symptoms | 1.07 (0 to 3.20) | 0 (0 to 1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.73 (0.52 to 2.95) | 0 (0 to 0) | < 0.001 | 0.90 (0 to 3.20) | 0.04 (0 to 1.14) | 0.018 |

| SAQLI score | 0.44 (0 to 1.59) | 0 (0 to 0.42) | < 0.001 | 0.50 (0 to 0.88) | 0 (0 to 0.07) | < 0.001 | 0.28 (0 to 1.59) | 0.04 (0 to 0.42) | 0.066 |

Data are median (range) values of area under the curve above baseline divided by time from randomisation to death. Data from Bourke 2006.

Abbreviations: NIV: non‐invasive ventilation; SAQLI: Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index; SF‐36 MCS: 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey Mental Component Summary; SF‐36 PCS: 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey Physical Component Summary

Other primary quality of life outcomes in the included study

Bourke 2006 chose the SF‐36 MCS (reported above) and the sleep‐related SAQLI symptoms domain as primary quality of life outcome measures, based on the results of a pilot study. The study report and the trial protocol do not indicate whether these outcomes were prespecified as primary.

The study showed that the median time the SAQLI symptoms domain score was maintained above 75% of the baseline after initiation of NIV was significantly longer with NIV than with standard care in the group as a whole and in the subgroup with normal and moderately impaired bulbar function. In participants with poor bulbar function, NIV conferred no significant benefit in maintaining the SAQLI symptoms score above 75% of baseline. See Table 2.

A significant difference in time‐weighted mean improvement of SAQLI between the NIV and standard care group was present in the group as a whole and in both subgroups. See Table 3.

2a. Quality of life median values at one and six months

No data were available.

3. Functional rating scale at one or six months or longer

No data were available for the ALSFRS to be analysed.

3a. Functional rating scales median values

No data were available.

4. Proportion experiencing adverse events related to mechanical ventilation

Neither Jackson 2001 nor Bourke 2006 reported adverse events related to mechanical ventilation.

Discussion

Two reports of RCTs of nocturnal mechanical ventilation in ALS were available for this review. Both trials employed NIV. Since only one of the reports provided data suitable for analysis (Bourke 2006), we were not able to perform a meta‐analysis.

Bourke 2006 was designed to assess the effect of NIV on survival and quality of life in people with ALS. The study provided moderate‐quality evidence that NIV prolongs median survival, and low‐quality evidence that it maintains quality of life in people with ALS overall. The benefit of NIV was striking in the subgroup of participants with better (normal or moderately impaired) bulbar function, but it is, however, important to note that six of nine participants in the standard group died within two weeks of randomisation, thus probably overestimating the effect of NIV in this subgroup of people with ALS. Non‐invasive ventilation did not prolong survival in people with ALS who had severe bulbar dysfunction, but did improve sleep‐related symptoms in this subgroup.

Despite the above shortcomings, Bourke 2006 has shown that NIV significantly improves quality of life over standard care, prolonging life for longer than is reported with riluzole (Miller 2012). The study has confirmed previous observations from non‐randomised trials of survival advantage and improved quality of life in people with ALS who start and can tolerate NIV at the onset of respiratory impairment (Bach 1993; Pinto 1995; Aboussouan 1997; Kleopa 1999; Lyall 2001b). It is unlikely that there will be further RCTs of NIV in unselected cohorts of people with ALS. In the view of the review authors, evidence from Bourke 2006 supports the belief that NIV is a major advance in the management of ALS, and it would be unethical in future trials not to offer NIV to people with ALS who have symptoms of nocturnal hypoventilation. The evidence supports benefit from NIV in people with ALS. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) carried out a cost‐effectiveness analysis using the Markov model and concluded that the use of NIV in the management of people with ALS represents a cost‐effective use of resources (NICE 2010).

A UK‐wide survey demonstrated that the provision of NIV to people with ALS is increasing (O'Neill 2012). A study has also reported on the obstacles people with ALS experience in using NIV and how to address them (Baxter 2013a). Some people with ALS are unable to tolerate NIV and decide to discontinue its use. Careful attention to secretion management, humidification, and comfortable interfaces may improve compliance with NIV. Detailed explanation to the patient along with emphasis of benefits may pre‐empt difficulties. A qualitative study has addressed concerns about the use of NIV in the terminal phase of the disease (Baxter 2013b). This study did not find the use of NIV in the last days of life to be associated with any adverse effects. The authors advised rapid withdrawal rather than gradual weaning when patients express a wish to discontinue NIV. The study concluded that patients' wishes should guide the use of NIV at the end of life. Another study investigated the impact of NIV on the family carer and concluded that NIV had no significant impact on carer burden (Baxter 2013c).

Conclusions from Bourke 2006 cannot be extended to people with ALS who do not have respiratory symptoms. It has been suggested that early treatment with NIV may offer a survival benefit above that demonstrated in Bourke 2006. There is some evidence from non‐controlled studies that early NIV improves survival and reduces decline of FVC in ALS (Carratu 2009). NCT01641965 is an ongoing RCT evaluating the impact of early NIV in people with ALS who have mild respiratory involvement. Jacobs 2016 is a pilot study that aimed to determine the feasibility of conducting a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of early NIV versus sham NIV in people with ALS. The study was not powered to assess clinical outcomes.

Non‐invasive ventilation settings may require titration with disease progression. A randomised trial is evaluating the use of polysomnography in guiding the initiation and further titration of NIV therapy during the course of the disease (NCT01363882). Different ventilator modes and settings are to be assessed in two NIV trials in people with ALS. The Italian multicentre randomised NIV study was designed to evaluate clinical efficacy, the participants' tolerance and quality of life and the frequency of changing settings in people with ALS who are undergoing NIV with pressure support ventilation or volume‐assisted ventilation (NCT00560287). However, this trial is compromised due to incomplete outcome data. The Columbia University study is designed to measure difference in pulmonary function and respiratory muscle pressure testing, gas exchange, and subjective dyspnoea between baseline and two different ventilator modes (high‐ and low‐level non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation) (NCT00537446). Another study is evaluating the use of an Intelligent Volume‐Assured Pressure Support (iVAPS) ventilator in ALS (NCT01746381). Most of these studies are not eligible for this review, which focuses on NIV compared to no NIV or standard care. They may, however, inform the best pressure settings of NIV and the ideal time of its initiation to obtain the maximum benefit.

Another Cochrane Review of nocturnal ventilation for daytime hypoventilation in neuromuscular and chest wall disorders concluded, while noting several methodological limitations, that mechanical ventilation is associated with survival benefit in MND (Annane 2014). This conclusion was based on three trials (Pinto 1995; Jackson 2001; Bourke 2006). Jackson 2001 is included in this review, but we consider it to be at high risk of bias due to selective reporting. We excluded Pinto 1995 as we considered it a non‐randomised controlled study. Another review on the management of respiratory problems in neurodegenerative disease concluded that the evidence to support the role of NIV was strongest for MND, although the evidence itself was weak (Jones 2012).

A limitation of the evidence in this review is that it was based on a single RCT with 41 participants, and hence we assessed the quality of the evidence as moderate for improvement in survival. However, findings of this trial are consistent with the findings of several other studies, which together offer strong support for the benefit of NIV for people with ALS in respiratory failure. We contacted investigators of registered but unreported trials to determine whether they had been abandoned or were completed but unpublished. We did not identify any study that addressed the adverse effects of NIV.

The review protocol did not define the quality of life outcome in detail. The protocol and study report of Bourke 2006 do not state whether the primary quality of life domains or analyses were prespecified (Bourke 2006; ISRCTN76330611). To reduce the risk of selective reporting in the review, we reported summary scores for both scales and both types of analysis, including results for the SAQLI symptoms score, which was a primary quality of life outcome in the trial.

The review authors clarified eligible comparisons in the methods, explicitly excluding trials assessing the timing of initiation and other aspects of NIV delivery or specification. This decision excludes some studies of NIV, limiting its scope to the central question of the effects of NIV versus 'standard care' or versus no NIV as originally intended. New, ongoing studies are addressing further issues about the timing of NIV initiation and further titration with the disease progression. Future reviews will assess different modes, schedules, and initiation of ventilation.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Moderate‐quality evidence from a single randomised controlled trial (RCT) of non‐invasive ventilation (NIV) involving 41 participants suggests that NIV significantly prolongs survival in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Low‐quality evidence suggests that it maintains quality of life in people with ALS. Survival and some measures of quality of life were significantly improved in the subgroup of people with better bulbar function, but not in those with severe bulbar impairment. Adverse effects related to NIV should be systematically reported, as at present there is little information on this subject.

Implications for research.

More evidence in the form of RCTs to support the use of NIV in ALS will be difficult to generate, as not offering NIV to the control group is no longer ethically justifiable. Future studies should examine the benefits of early intervention with NIV and establish the most appropriate timing for initiating NIV, in order to obtain its maximum benefit. The effect of adding cough augmentation techniques to NIV also needs to be ascertained in an RCT. Future studies should examine the health economics of NIV and factors influencing access to NIV. Access to NIV remains restricted in many parts of the world, including Europe and North America. We need to understand the factors, personal and socioeconomic, that determine access to NIV.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 June 2018 | Amended | Corrected typographical error |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2003 Review first published: Issue 4, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 January 2017 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New searches performed. We identified no new included studies. We updated some of the methodology and added a 'Summary of findings' table. We searched trials registries for ongoing or completed but unreported trials. We determined the status of apparently unpublished registered trials via contact with trial authors. We added quality of life data from Bourke 2006, for completeness of reporting. |

| 30 January 2017 | New search has been performed | Searches were updated to January 2017. |

| 24 August 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Searches updated to May 2012, no new trials included. We updated the Background and edited the review. Muhammad K Rafiq and Ruth Brassington are new authors. Kate Jewitt has withdrawn. |

| 6 August 2012 | New search has been performed | This is an update of a review first published in 2009. |

| 23 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr EA Oppenheimer for his comments on earlier drafts of the protocol. We are grateful to Professor Nigel Leigh, who developed the protocol for this review and contributed to the original assessment of studies, and Kate Jewitt, former Managing Editor of the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group, who was an author of the original review. Angela Gunn, Information Specialist at Cochrane Neuromuscular, performed the searches.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Neuromuscular. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the review authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, National Health Service, or the Department of Health. Cochrane Neuromuscular is also supported by the MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases and the Motor Neurone Disease Association.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Neuromuscular Specialised Register (CRS) search strategy

#1 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Motor Neuron Disease Explode All [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #2 "moto? neuron? disease?" or "moto?neuron? disease?" [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #3 "charcot disease" [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #4 "amyotrophic lateral sclerosis" [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #5 als:ti or als:ab or nmd:ti or mnd:ab [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #6 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #7 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Respiration, Artificial [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #8 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Ventilators, Mechanical Explode All [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #9 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Respiratory Insufficiency Explode All [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #10 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Positive‐Pressure Respiration Explode All [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #11 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Intubation, Intratracheal [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #12 (artificial NEXT respiration) or (mechanical NEXT ventilator*) [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #13 "respiratory insufficiency" or "positive pressure" or positivepressure or bipap or tracheotomy or tracheostomy or intubation [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #14 ("non invasive" or noninvasive) NEAR5 ventilation [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #15 #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #16 #6 AND #15 [REFERENCE] [STANDARD] #17 (#6 AND #15) AND (INREGISTER) [REFERENCE] [STANDARD]

Appendix 2. CENTRAL (CRSO) search strategy

#1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Motor Neuron Disease EXPLODE ALL TREES #2 ("motor neuron disease" OR "motor neurone disease" OR "motoneuron disease" OR "motorneuron disease" OR "amyotrophic lateral sclerosis"):TI,AB,KY #3 (Gehrig* NEAR syndrome*):TI,AB,KY #4 (Gehrig* NEAR disease*):TI,AB,KY #5 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 #6 MESH DESCRIPTOR Ventilators, Mechanical EXPLODE ALL TREES #7 MESH DESCRIPTOR Respiratory Insufficiency EXPLODE ALL TREES #8 MESH DESCRIPTOR Intubation EXPLODE ALL TREES #9 (artificial NEAR1 respiration):TI,AB,KY #10 (mechanical NEAR1 ventilat*):TI,AB,KY #11 (positive NEXT pressure next respiration):TI,AB,KY #12 (tracheostomy or tracheotomy or intubation):TI,AB,KY #13 (respiratory NEXT insufficiency):TI,AB,KY #14 ((positive NEXT pressure) or positivepressure or bipap):TI,AB,KY #15 (non NEXT invasive NEAR ventilation):TI,AB,KY #16 #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 #17 #5 and #16

Appendix 3. MEDLINE (OvidSP) search strategy

Database: Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present> MEDLINE(R) 1946 to December Week 1 2016 Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 randomized controlled trial.pt. (509791) 2 controlled clinical trial.pt. (98335) 3 randomized.ab. (440350) 4 placebo.ab. (205433) 5 drug therapy.fs. (2143873) 6 randomly.ab. (300053) 7 trial.ab. (473263) 8 groups.ab. (1841175) 9 or/1‐8 (4401590) 10 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (4861434) 11 9 not 10 (3799680) 12 exp Motor Neuron Disease/ (26902) 13 (moto$1 neuron$1 disease$1 or moto?neuron$1 disease).mp. (8698) 14 ((Lou Gehrig$1 adj5 syndrome$1) or (Lou Gehrig$1 adj5 disease)).mp. (211) 15 charcot disease.tw. (21) 16 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.mp. (25439) 17 or/12‐16 (35394) 18 Respiration, Artificial/ (46571) 19 exp Ventilators, Mechanical/ (9120) 20 exp Respiratory Insufficiency/ (62240) 21 Positive‐Pressure respiration/ (17376) 22 tracheotomy/ or tracheostomy/ (15141) 23 exp Intubation, Intratracheal/ (36501) 24 ((artificial adj1 respiration) or (mechanical adj1 ventilator$) or respiratory insufficiency or positive pressure$ or positivepressure$ or bipap or tracheotomy or tracheostomy or intubation).mp. (177327) 25 ((non invasive or noninvasive) adj5 ventilation).mp. (6294) 26 or/18‐25 (204730) 27 11 and 17 and 26 (261) 28 remove duplicates from 27 (224)

Appendix 4. Embase (OvidSP) search strategy

Database: Embase <1974 to 2017 January 26> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 crossover‐procedure.sh. (54965) 2 double‐blind procedure.sh. (140535) 3 single‐blind procedure.sh. (29251) 4 randomized controlled trial.sh. (476907) 5 (random$ or crossover$ or cross over$ or placebo$ or (doubl$ adj blind$) or allocat$).tw,ot. (1375392) 6 trial.ti. (222222) 7 or/1‐6 (1537379) 8 (animal/ or nonhuman/ or animal experiment/) and human/ (1771621) 9 animal/ or nonanimal/ or animal experiment/ (3818500) 10 9 not 8 (3101225) 11 7 not 10 (1421688) 12 Motor Neuron Disease/ or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/ (37204) 13 (moto$1 neuron$1 disease$1 or moto?neuron$1 disease$1).mp. (11931) 14 ((Lou Gehrig$1 adj5 syndrome$1) or (Lou Gehrig$1 adj5 disease)).mp. (187) 15 charcot disease.tw. (26) 16 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.tw. (23559) 17 or/12‐16 (39624) 18 exp Artificial Ventilation/ (164181) 19 Ventilator/ (25931) 20 exp Respiratory Failure/ (85263) 21 exp Assisted Ventilation/ (141349) 22 Tracheotomy.mp. or TRACHEOTOMY/ (13209) 23 tracheostomy.mp. or TRACHEOSTOMY/ (23193) 24 RESPIRATORY TRACT INTUBATION/ (2942) 25 ((non invasive or noninvasive) adj5 ventilation).mp. (11674) 26 (artificial ventilat$ or artificial respiration or (mechanical adj1 ventilator$) or respiratory failure or respiratory insufficiency or positive pressure$ or positivepressure$ or bipap or assisted ventilation or intubation).mp. (263834) 27 or/18‐26 (356006) 28 11 and 17 and 27 (206) 29 remove duplicates from 28 (194) 30 29 not medline.st. (190)

Appendix 5. CINAHL Plus (EBSCOhost) search strategy

Monday, January 30, 2017 7:05:10 AM S33 S31 AND S32 2 S32 EM 20151101‐ Limiters ‐ Exclude MEDLINE records Search modes ‐ Boolean/Phrase 154,352 S31 S30 Limiters ‐ Exclude MEDLINE records Search modes ‐ Boolean/Phrase 11 S30 S18 and S23 and S29 96 S29 S24 or S25 or S26 or S27 or S28 46,165 S28 (non invasive or noninvasive ) and ventilation 2,388 S27 (MH "Intubation, Intratracheal+") 11,461 S26 respiratory failure or Tracheotomy or Tracheostomy or intratracheal intubation 21,686 S25 mechanical ventilat* or positive pressure* or positivepressure* or bipap 19,602 S24 (MH "Mechanical Ventilation (Iowa NIC)") OR (MH "Ventilators, Mechanical") OR (MH "Respiration, Artificial") 16,209 S23 S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 7,215 S22 ("Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis") 3,195 S21 Lou Gehrig* and ( disease* or syndrome* ) 37 S20 (moto* neuron* disease* or moto?neuron* disease) 1,340 S19 (MH "Motor Neuron Diseases+") 6,504 S18 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 904,082 S17 ABAB design* 92 S16 TI random* or AB random* 196,479 S15 ( TI (cross?over or placebo* or control* or factorial or sham? or dummy) ) or ( AB (cross?over or placebo* or control* or factorial or sham? or dummy) ) 388,859 S14 ( TI (clin* or intervention* or compar* or experiment* or preventive or therapeutic) or AB (clin* or intervention* or compar* or experiment* or preventive or therapeutic) ) and ( TI (trial*) or AB (trial*) ) 147,267 S13 ( TI (meta?analys* or systematic review*) ) or ( AB (meta?analys* or systematic review*) ) 52,124 S12 ( TI (single* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) or AB (single* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) ) and ( TI (blind* or mask*) or AB (blind* or mask*) ) 30,822 S11 PT ("clinical trial" or "systematic review") 132,091 S10 (MH "Factorial Design") 988 S9 (MH "Concurrent Prospective Studies") or (MH "Prospective Studies") 297,562 S8 (MH "Meta Analysis") 26,160 S7 (MH "Solomon Four‐Group Design") or (MH "Static Group Comparison") 53 S6 (MH "Quasi‐Experimental Studies") 8,169 S5 (MH "Placebos") 9,984 S4 (MH "Double‐Blind Studies") or (MH "Triple‐Blind Studies") 34,806 S3 (MH "Clinical Trials+") 209,300 S2 (MH "Crossover Design") 14,288 S1 (MH "Random Assignment") or (MH "Random Sample") or (MH "Simple Random Sample") or (MH "Stratified Random Sample") or (MH "Systematic Random Sample") 74,845

Appendix 6. AMED (OvidSP) search strategy

Database: AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine) <1985 to January 2017> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 Randomized controlled trials/ (1815) 2 Random allocation/ (314) 3 Double blind method/ (608) 4 Single‐Blind Method/ (80) 5 exp Clinical Trials/ (3589) 6 (clin$ adj25 trial$).tw. (6531) 7 ((singl$ or doubl$ or treb$ or trip$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$ or dummy)).tw. (2737) 8 placebos/ (578) 9 placebo$.tw. (2953) 10 random$.tw. (16335) 11 research design/ (1888) 12 Prospective Studies/ (941) 13 meta analysis/ (203) 14 (meta?analys$ or systematic review$).tw. (3023) 15 control$.tw. (33313) 16 (multicenter or multicentre).tw. (933) 17 ((study or studies or design$) adj25 (factorial or prospective or intervention or crossover or cross‐over or quasi‐experiment$)).tw. (12019) 18 or/1‐17 (51672) 19 Motor neuron disease/ (109) 20 (moto$1 neuron$1 disease$1 or moto?neuron$1 disease).mp. (182) 21 ((Lou Gehrig$1 adj5 syndrome$1) or (Lou Gehrig$1 adj5 disease)).mp. (2) 22 charcot disease.tw. (1) 23 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/ (207) 24 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.tw. (287) 25 or/19‐24 (443) 26 exp Respiration artificial/ or artificial respiration.mp. (473) 27 Ventilators mechanical/ or mechanical ventilat$.mp. (441) 28 exp respiratory insufficiency/ (169) 29 respiratory insufficiency.mp. (151) 30 (positive pressure$ or positivepressure$).mp. (192) 31 bipap.mp. (4) 32 Tracheotomy/ or tracheotomy.mp. (31) 33 tracheostomy.mp. (84) 34 Intubation/ or intubation.mp. (123) 35 ((non invasive or noninvasive) adj5 ventilation).mp. (119) 36 or/26‐35 (1112) 37 18 and 25 and 36 (6)

Appendix 7. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

1 Ventilation in ALS

2 Non‐invasive ventilation in ALS

3 Tracheostomy ventilation in ALS

4 Mechanical ventilation in ALS

Appendix 8. WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search strategy

1 Ventilation in ALS

2 Non‐invasive ventilation in ALS

3 Tracheostomy ventilation in ALS

4 Mechanical ventilation in ALS

Appendix 9. Additional methods

If meta‐analysis becomes possible with the inclusion of more trials, we will use the following methods, which are based on a standard template developed by Cochrane Airways and modified by the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group.

Measures of treatment effect

For the primary outcome measure we planned to calculate an overall measure of treatment efficacy combining survival results at different time points. This measure is based on estimating a pooled hazard ratio (i.e. at any given time point the risk of death for the survivors in the treated group divided by risk of death for the survivors in the control group) as described by Parmar 1998. We wanted to use this measure rather than the summary risk ratio (RR) calculated by the Cochrane statistical software, Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014), because the Parmar method uses all the data on survival from the whole observation period, whereas Review Manager 5 needs the survival rates at the same fixed point in time since the start of observation to be reported for all the studies if they are to be combined.

For the secondary outcome measures reported as continuous variables, we planned to calculate a mean of the difference between their effects using Review Manager 5. Had we found trials using dichotomous outcome measures such as death rates after a fixed time, for example three months, we planned to obtain RR with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Had we found trials where the studies measured continuous outcomes that are conceptually the same but are measured in different ways (such as different assessment scales), we planned to combine the results and express them as standardised mean differences (using standard deviation units) with 95% CI.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to use the I² statistic for quantifying inconsistency across trials in any meta‐analysis, as described in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, using the following as a rough guide for interpretation (Higgins 2011):

0% to 40%: low heterogeneity;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If in the future we identify more trials, we will assess small‐study effects using funnel plots; however, these must be interpreted with caution and are not considered useful if fewer than 10 trials are included in an analysis (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We planned to use Review Manager 5 for data synthesis if possible. We planned to use a fixed‐effect analysis, and to use a random‐effects analysis in the event of unexplained heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Had we found heterogeneity of a moderate or greater level, we planned to first check the data and then consider whether pooling the data was justified. We would then have undertaken a sensitivity analysis by repeating the calculation omitting the trials at high risk of bias. If heterogeneity was not explained by variations in trial quality, we would have used a random‐effects approach to obtain the pooled estimates from the group of trials.

Subgroups of interest were participants with or without significant bulbar symptoms as categorised by the authors of the papers reviewed.

We considered non‐randomised evidence concerning adverse events and the cost and cost‐effectiveness of different forms of mechanical ventilation in the Discussion.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to undertake sensitivity analyses to demonstrate the effect of downweighting or ignoring those studies that were at high risk of bias on individual criteria, if sufficient numbers of trials and relevant data were available for meta‐analysis.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bourke 2006.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 41 participants with ALS Age: 63.7 ± 10.3 and 63.0 ± 8.1 years Male sex 64% and 53% Disease duration 1.9 ± 1.3 and 2.0 ± 1.1 years Baseline characteristics: vital capacity (% predicted) 55.6 ± 18.7% and 48.8 ± 20.7%, maximum inspiratory pressure ‐ Pimax (% predicted) 31.1 ± 11.0% and 31.0 ± 10.6%, SNIP (% predicted) 22.6 ± 11.4% and 24.4 ± 10.8%, PaCO2 (mmHg) 6.1 ± 1.1 and 6.4 ± 1.2 in NIV and standard care group respectively at randomisation (mean ± SD) |

|

| Interventions | Intervention: NIV (n = 22) Control: standard care (n = 19) |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: overall survival after initiation of assisted ventilation Secondary outcomes: survival at 1 and 6 months, SF‐36, and SAQLI |

|

| Funding | ResMed UK Ltd and the Motor Neurone Disease Association provided funding for the study. | |

| Conflicts of interest for primary investigators | No reported conflicts of interest | |

| Notes | Protocol: ISRCTN76330611 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Immediate allocation following randomisation |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not possible to blind delivery of the non‐invasive ventilation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No information given on whether outcome assessors were blinded to knowledge of allocation intervention when assessing the data. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 13 withdrawals during surveillance, but no participants withdrew after randomisation. 1 participant alive 45 months after randomisation; all others were followed up to death. All outcome measures were measured by intention to treat. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is available, and all of the study’s prespecified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review were reported. The report and protocol do not state whether the choice of primary quality of life outcomes in the trial report or the choice of analyses were prespecified, but data were provided for all domains. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other bias identified. |

Jackson 2001.

| Methods | Prospective randomised study | |

| Participants | 7 participants with ALS in early NIPPV group and 6 participants in late NIPPV group No age or sex provided. Baseline characteristics: FVC = 77 ± 13% (mean ± SD) in early NIPPV group at baseline and time of randomisation. FVC = 77 ± 6% (mean ± SD) in late NIPPV at baseline. The time to randomisation (FVC < 50% predicted) for the late NIPPV group = 59 ± 38 days (mean ± SD). |

|

| Interventions | Early NIPPV (FVC 70% to 100%) and late ("standard of care") NIPPV (FVC < 50%) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: not available Secondary outcomes: survival at 3 months, SF‐36, ALSFRS‐R, and SAQLI |

|

| Funding | National Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association. Respironics for provision of equipment | |

| Conflicts of interest for primary investigators | No conflicts of interest statement given in the manuscript. | |

| Notes | Pilot study that failed to develop further, due to lack of funding. The study was deemed as at high risk of bias due to selective reporting. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Described as randomised but no method of randomisation stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | 2 sets of random assignments in blocks of 4 for each centre were prepared by a statistician. Randomisation was carried out separately for bulbar‐ and limb‐onset participants. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Participants were not blinded to their treatment allocation. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Trial described as a single‐blind study, with pulmonary assessments, ALSFRS‐R, SAQLI, and SF‐36 repeated every 3 months by a blinded clinical evaluator. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Only early NIPPV group analysed, outcome of 1 participant not clear. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Study protocol not available. Numerical data not systematically reported. |

| Other bias | High risk | Nocturnal hypoventilation not defined as per the universally accepted criteria. |

ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis ALSFRS‐R: revised Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale FVC: forced vital capacity NIPPV: non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation NIV: non‐invasive ventilation PaCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood SAQLI: Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index SD: standard deviation SF‐36: 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey SNIP: sniff nasal inspiratory pressure

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Aboussouan 1997 | Not a randomised trial. Observational cohort study of 18 NIV tolerant and 21 NIV non‐tolerant participants with ALS |

| Bach 1993 | Not a randomised trial. Retrospective study of 89 people with ALS. No control group |

| Berlowitz 2016 | Not a randomised trial. Study of the effect of NIV on survival and pulmonary function decline across MND/ALS phenotypes using data from 929 people with ALS/MND |

| Buhr‐Schinner 1999 | Not a randomised trial. Retrospective study without control group. 38 people with ALS received intermittent nasal mechanical ventilation using pressure‐ and volume‐cycled respirators. |

| Cazzolli 1996 | Not a randomised trial. Retrospective study. 29 people with ALS used nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation, and 50 used tracheostomy intermittent positive pressure ventilation. |

| Cedarbaum 2001 | Not a randomised trial. No control group. 28 participants received BPAP, and 7 received mechanical ventilation via tracheostomy. |

| David 1997 | Not a randomised trial. Retrospective study without control group. 13 people with ALS received BPAP. |

| Goulon 1989 | Not a randomised trial. Retrospective study of 16 people with ALS receiving assisted ventilation |

| Jacobs 2016 | Primary aim was early initiation of NIV. Once current standard criteria for NIV initiation were reached, both arms were offered NIV. Study did not assess NIV use in people with ALS with respiratory muscle weakness causing ventilator failure or nocturnal hypoventilation with sleep‐disordered breathing. |

| Kamimoto 1989 | Not a randomised trial. Retrospective study of 13 people with ALS receiving mechanical ventilation |

| Kleopa 1999 | Not a randomised trial. Retrospective study of 122 people with ALS. 38 participants used BPAP for more than 4 hours day, 32 participants used BPAP for less than 4 hours a day, and 52 participants refused to try BPAP. |

| Lo Coco 2006 | Not a randomised trial. Prospective study of 44 NIV tolerant ALS participants and 27 NIV non‐tolerant participants |

| Lo Coco 2007 | Not a randomised trial. Retrospective study of 33 consecutive ALS patients in acute respiratory failure receiving tracheostomy intermittent positive pressure ventilation |

| Lyall 2001b | Not a randomised trial. Prospective cohort study of 16 people with ALS on NIV and 11 normal age‐matched controls |

| Mustfa 2006 | Not a randomised trial. A prospective 1‐year study of the efficacy of NIV for ALS. Comparison group declined NIV. Not blinded |

| NCT00386464 | Described in trial registry as a randomised comparison of NIV at night or usual care. Investigator responded to review authors' enquiry in November 2015 that the trial had recruitment problems, was not completed, and there have been no publications. |

| NCT00537446 | Does not compare ventilation to no ventilation or standard care; compared high‐level ventilation versus low‐level ventilation (each for 2 hours) |

| NCT00560287 | Does not compare ventilation to no ventilation or standard care; this was a comparison of pressure support versus volume‐assisted mode NIV delivered by home care providers. No publication identified. |

| NCT00958048 | Listed in trial registry as a randomised controlled trial of non‐invasive ventilation (BPAP) versus no non‐invasive ventilation. The contact person (Dr Lee) informed the review authors that the study was converted into an observational study, as participants were not willing to be randomised, hence the study was not eligible for inclusion. |

| NCT01363882 | Randomised trial. Does not compare ventilation to no ventilation or standard care. Polysomnography‐guided adjustment of NIV versus standard initiation of NIV |

| NCT01641965 | Randomised trial. Does not compare ventilation to no ventilation or standard care; compared home pressure ventilator model Vivo 40 (BREAS Medical AB) initiated early (when FVC is less than 75% predicted) versus standard initiation (when FVC is less than 50% predicted). No outcome data on NIV, survival, or quality of life available in abstract. |

| NCT01746381 | Randomised trial. Does not compare ventilation to no ventilation or standard care; compared different modes of ventilation (intelligent Volume‐Assured Pressure Support (iVAPS) versus standard built‐in self test (BiST) mode) |

| NCT02537132 | Randomised trial. Assessment of adaptation to NIV via home‐ or clinic‐based training |

| Newsom‐Davis 2001 | Not a randomised trial. Prospective study of 9 people with ALS with hypoventilation given NIPPV, compared with 10 normal age‐matched controls without ventilation problems |

| Perez 2003 | Randomised trial terminated early due to problems recruiting participants |

| Pinto 1995 | Not a randomised trial. Prospective controlled study of 20 consecutive patients, first 10 received standard care and following 10 received NIV |

| Pinto 1999 | Not a randomised trial. Controlled study of exercise in people with ALS with respiratory insufficiency. 8 participants on NIV and 12 ALS controls |

| Pinto 2003 | Not a randomised trial. Historical controls |

| Saito 1999 | Not a randomised trial. Retrospective review of 25 cases using positive pressure ventilation with tracheostomy |

| Shoesmith 2007 | Not a randomised trial. Retrospective review of 13 cases |

| Sivak 1982 | Not a randomised trial. Anecdotal study |