Abstract

Background

This is an update of a review published in 2012. A related review "Inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia in ventilated very low birth weight preterm neonates" has been updated as well. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a serious and common problem among very low birth weight infants, despite the use of antenatal steroids and postnatal surfactant therapy to decrease the incidence and severity of respiratory distress syndrome. Due to their anti‐inflammatory properties, corticosteroids have been widely used to treat or prevent BPD. However, the use of systemic steroids has been associated with serious short‐ and long‐term adverse effects. Administration of corticosteroids topically through the respiratory tract may result in beneficial effects on the pulmonary system with fewer undesirable systemic side effects.

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness of inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids administered to ventilator‐dependent preterm neonates with birth weight ≤ 1500 g or gestational age ≤ 32 weeks after 7 days of life on the incidence of death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

Search methods

We used the standard search strategy of Cochrane Neonatal to search the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2017, Issue 1), MEDLINE via PubMed (1966 to 23 February 2017), Embase (1980 to 23 February 2017), and CINAHL (1982 to 23 February 2017). We also searched clinical trials registers, conference proceedings and the reference lists of retrieved articles for randomised controlled trials and quasi‐randomised trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials comparing inhaled versus systemic corticosteroid therapy (irrespective of dose and duration) starting after the first week of life in ventilator‐dependent very low birth weight infants.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by the Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

We included three trials that involved a total of 431 participants which compared inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids to treat BPD. No new trials were included for the 2017 update.

Although one study randomised infants at < 72 hours (N = 292), treatment started when infants were aged > 15 days. In this larger study, deaths were included from the point of randomisation and before treatment started. Two studies (N = 139) randomised and started treatment at 12 to 21 days.

Two trials reported non‐significant differences between groups for the primary outcome: incidence of death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age among all randomised infants. Estimates for the largest trial were Relative risk (RR) 1.04 (95% Confidence interval (CI) 0.86 to 1.26), Risk difference (RD) 0.03 (95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.15); (moderate‐quality evidence). Estimates for the other trial reporting the primary outcome were RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.05), RD ‐0.06 (95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.05); (low‐quality evidence).

Secondary outcomes that included data from all three trials showed no significant differences in the duration of mechanical ventilation or supplemental oxygen, length of hospital stay, or the incidence of hyperglycaemia, hypertension, necrotising enterocolitis, gastrointestinal bleed, retinopathy of prematurity or culture‐proven sepsis moderate‐ to low‐quality evidence).

In a subset of 75 surviving infants who were enrolled from the United Kingdom and Ireland, there were no significant differences in developmental outcomes at seven years of age between groups (moderate‐quality evidence). One study received grant support and the industry provided aerochambers and metered dose inhalers of budesonide and placebo for the same study. No conflict of interest was identified.

Authors' conclusions

We found no evidence that inhaled corticosteroids confer net advantages over systemic corticosteroids in the management of ventilator‐dependent preterm infants. There was no evidence of difference in effectiveness or adverse event profiles for inhaled versus systemic steroids.

A better delivery system guaranteeing selective delivery of inhaled steroids to the alveoli might result in beneficial clinical effects without increasing adverse events.

To resolve this issue, studies are needed to identify the risk/benefit ratio of different delivery techniques and dosing schedules for administration of these medications. The long‐term effects of inhaled steroids, with particular attention to neurodevelopmental outcomes, should be addressed in future studies.

Plain language summary

Inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in ventilated very low birth weight preterm infants

Review question

To compare the effectiveness of inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids administered to ventilator‐dependent preterm neonates with birth weight ≤ 1500 g or gestational age ≤ 32 weeks after 7 days of life on the incidence of chronic lung disease at 36 weeks' corrected postmenstrual age.

Background

Preterm babies (babies born before term, 40 weeks pregnancy) often need breathing (ventilator) support. Babies who need invasive (placing a breathing tube in the wind pipe) mechanical breathing support for a prolonged period often develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia (defined as requirement for supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age). It is thought that inflammation in the lungs may be part of the cause. Corticosteroid drugs reduce inflammation and swelling in the lungs, but can have serious side effects. Corticosteroid use has been associated with cerebral palsy (motor problem) and developmental delay. Inhaling steroids, so that the drug reaches the lungs directly, has been tried as a way to limit adverse effects.

Search date

23 February 2017.

Study characteristics

All three included trials were randomised, but the blinding of intervention and outcome measurement varied. Data from two trials (enrolling 139 infants) were combined as they enrolled infants between 12 and 21 days of age, but data from one trial (enrolling 292 infants) were reported separately because researchers randomised infants aged less than 72 hours. The timing when the outcomes were measured varied among studies so it was not appropriate to combine some results. In one study all deaths that occurred were reported from the time babies were randomised not from when treatment started, hence there was a greater number of babies who died in that study.

One study received grant support and the industry provided Aerochambers and metered dose inhalers of budesonide and placebo for the same study. No conflict of interest was identified.

Key results

Evidence from two studies in 370 infants, who were randomised between 12 and 21 days of age and who contributed data to the primary outcome of this review, showed that inhaled steroids administered after 7 days of age compared with systemic steroids did not decrease the incidence of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age. Evidence from the single study in which infants were randomised at less than 72 hours of age did not show difference the incidence of death or BPD.

Evidence from three studies in 431 infants contributing to secondary outcomes showed that inhaled steroids administered after seven days of age compared with systemic steroids did not significantly alter the incidence of BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age, hyperglycaemia, hypertension, duration of ventilation, duration of oxygen supplementation, length of hospital stay, intraventricular haemorrhage grade III‐IV, periventricular leukomalacia, necrotising enterocolitis, gastrointestinal bleed, retinopathy of prematurity stage > 3, culture‐proven sepsis or the incidence of adverse effects.

Adverse event profiles did not differ for inhaled versus systemic steroids but some potential complications of steroid treatment have not been reported. More research is needed to show whether any form of routine use of steroids results in overall health improvements for babies at risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence quality (according to GRADE criteria) was moderate to low.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a serious and common problem among very low birth weight infants despite the use of antenatal steroids (Roberts 2017) and postnatal surfactant therapy (Soll 1998; Bahadue 2012) to decrease the incidence and severity of respiratory distress syndrome. The incidence of BPD varies between 23% and 26% (Lee 2000; Lemons 2001) in very low birth weight infants (< 1500 g) and has an inverse relationship to both gestational age and birth weight (Lee 2000; Sinkin 1990).

Description of the intervention

Several randomised controlled trials (Avery 1985; CDTG 1991; Cummings 1989; Harkavy 1989; Kazzi 1990; Ohlsson 1992) and systematic reviews (Bhuta 1998; Doyle 2014; Doyle 2014a; Halliday 1999; Shah 2001) have demonstrated that among infants with BPD, treatment with systemic corticosteroids facilitates extubation and improves respiratory system compliance. Marked heterogeneity regarding the dose and duration of dexamethasone administration has been noted among trials. However, corticosteroids appear to have little effect on the duration of supplemental oxygen, duration of hospitalisation or mortality (Avery 1985; CDTG 1991; Harkavy 1989; Kazzi 1990; Ohlsson 1992). There are concerns regarding the short‐ and long‐term side effects of systemic steroids in this population. These include hyperglycaemia, hypertension, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, gastrointestinal haemorrhage and perforation, enhanced catabolism and growth failure, nephrocalcinosis, poor bone mineralization and susceptibility to infection (Ng 1993; Stark 2001).

The potential effects on brain growth and neurodevelopment are most alarming. Animal models (rat and rhesus monkey) at a similar stage of ontogeny to the human fetus have shown that steroids permanently affect brain cell division, differentiation and myelination, as well as the ontogeny of cerebral cortical development (Johnson 1979; Weichsel 1977). These effects are long‐lasting and associated with decreased head circumference and neuromotor abnormalities. Several follow‐up studies of postnatal systemic corticosteroid therapy in preterm infants have shown higher incidence of neurodevelopmental abnormalities in surviving dexamethasone‐treated infants (O'Shea 1999; Shinwell 2000; Yeh 1998).

Theoretically, the use of inhaled corticosteroids may allow for beneficial effects on the pulmonary system without concomitant high systemic concentrations and less risk of adverse effects. Results from a large multicentre study of early use of inhaled steroids concluded that among extremely preterm infants, BPD incidence was lower among those who received early inhaled budesonide than among those who received placebo, but the advantage may have been gained at the expense of increased mortality (Bassler 2015). Results from this study have been incorporated in a Cochrane Review (Shah 2017) and a meta‐analysis (Shinwell 2016). Shinwell 2016 concluded that "Very preterm infants appear to benefit from inhaled corticosteroids with reduced risk for BPD and no effect on death, other morbidities, or adverse events. Data on long‐term respiratory, growth, and developmental outcomes are eagerly awaited". Shah 2017 summarised their findings as: "There is increasing evidence from the trials reviewed that early administration of inhaled steroids to very low birth weight neonates is effective in reducing the incidence of death or CLD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age among either all randomised infants or among survivors. Even though there is statistical significance, the clinical relevance is of question as the upper CI limit for the outcome of death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age is infinity. The long‐term follow‐up results of the Bassler 2015 study may affect the conclusions of this review. Further studies are needed to identify the risk/benefit ratio of different delivery techniques and dosing schedules for the administration of these medications. Studies need to address both the short‐ and long‐term benefits and adverse effects of inhaled steroids with particular attention to neurodevelopmental outcome".

It is noteworthy that a Cochrane Review by Onland 2017b concluded: "Despite the fact that some studies reported a modulating effect of treatment regimens in favour of higher‐dosage regimens on the incidence of BPD and neurodevelopmental impairment, recommendations on the optimal type of corticosteroid, the optimal dosage, or the optimal timing of initiation for the prevention of BPD in preterm infants cannot be made based on current level of evidence. A well‐designed large RCT is urgently needed to establish the optimal systemic postnatal corticosteroid dosage regimen".

Apart from studies included in this review, we are not aware of any other direct comparisons of early use of inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids.

How the intervention might work

It is thought that inflammation in the lungs may be part of the cause of BPD (Nelin 2017). As part of a randomised, placebo‐controlled trial of early inhaled beclomethasone therapy, Gupta 2000 measured interleukin‐8 (IL‐8) and interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist (IL‐1ra) concentrations in tracheal aspirates as markers of pulmonary inflammation. Beclomethasone‐treated infants with moderately elevated baseline IL‐8 levels received less subsequent systemic glucocorticoid therapy and had a lower incidence of BPD than non treated infants. Gupta 2000 and co‐authors concluded that early‐inhaled beclomethasone therapy was associated with a reduction in pulmonary inflammation after one week of therapy. Corticosteroid drugs when given orally or intravenously reduces this inflammation in the lungs (Nelin 2017). Corticosteroid use has been associated with cerebral palsy and developmental delay (AAP & CPS 2002; Nelin 2017). In a retrospective study of infants born at < 29 weeks PMA and assessed at 18 to 21 months corrected age it was found that exposure to inhaled steroids was not associated with increased odds of death or neurodevelopmental impairment (Kelly 2017). However, in the same study systemic steroids use before 4 weeks of age was associated with significantly worse outcomes (Kelly 2017). It is important to minimize exposure to the potentially harmful effects of corticosteroids, particularly on the developing brain (Doyle 2017).

Why it is important to do this review

Cochrane Reviews have addressed the use of systemic or inhaled corticosteroids in the prevention or treatment of BPD or chronic lung disease. These include reviews of the early use (< 8 days) of systemic postnatal corticosteroids to prevent chronic lung disease (Doyle 2014) and the late use (> 7 days) of systemic postnatal corticosteroids for chronic lung disease (Doyle 2014a).

Other Cochrane Reviews address the use of inhaled corticosteroids in the prevention or treatment of chronic lung disease. Shah 2017 reviewed the effects of early administration of inhaled corticosteroids for preventing chronic lung disease in ventilated very low birth weight preterm neonates and Onland 2017a reviewed the late use (≥ 7 days) of inhaled corticosteroids to reduce bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants.

Cochrane Reviews have also compared systemic and inhaled corticosteroids. Shah 2012 compared the use of inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids for preventing chronic lung disease in ventilated very low birth weight preterm neonates, and the use of inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of chronic lung disease in ventilated very low birth weight preterm infants (Shah 2012a).

The use of corticosteroids for other indications in neonates including intravenous dexamethasone to facilitate extubation (Davis 2001), corticosteroids for the treatment of hypotension (Ibrahim 2011) and corticosteroids for the treatment of meconium aspiration syndrome (Ward 2003) have been assessed in Cochrane Reviews.

In statements released by the European Association of Perinatal Medicine (Halliday 2001a), American Academy of Pediatrics (Watterberg 2010) and the Canadian Pediatric Society (Jefferies 2012), routine use of systemic dexamethasone for the prevention or treatment of BPD is not recommended. These recommendations were based on concerns regarding short and long‐term complications, especially cerebral palsy.

Thus, alternatives to systemic corticosteroids that may have fewer adverse consequences need to be investigated. Administration of corticosteroids topically through the respiratory tract might result in beneficial effects on the pulmonary system with fewer undesirable systemic side effects.

The aim of this review was to examine the effectiveness of inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids administered to ventilator‐dependent very low birth weight neonates of 1500 g or less after the first week of life, for the treatment of evolving BPD. This is an update of our review last published in 2012 (Shah 2012a).

Objectives

The primary objective was to compare the effectiveness of inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids administered to ventilator‐dependent preterm neonates with birth weight ≤ 1500 g or gestational age ≤ 32 weeks after 7 days of life on the incidence of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

Secondary objectives

To compare the effectiveness of inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids on other indicators of BPD, the incidence of adverse events, and long‐term neurodevelopmental outcome.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised clinical trials.

Types of participants

Ventilator‐dependent preterm infants with birth weight ≤ 1500 g or gestational age ≤ 32 weeks and postnatal age of more than 7 days of age.

Types of interventions

Inhaled corticosteroids compared to systemic corticosteroids irrespective of the type, dose and duration of therapy as long as the treatment started before 7 days of age.

Types of outcome measures

For the following two comparisons:

1. Inhaled versus systemic steroids among infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (infants randomised at < 72 hours of age)

2. Inhaled versus systemic steroids among infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (infants randomised between 12 and 21 days of age)

Primary outcomes

Death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

Secondary outcomes

Death or BPD at 28 days of age

Death at 36 week's postmenstrual age

Death at 28 days of age

For the following comparison:

3. Inhaled versus systemic steroids among infants ‐ (infants randomised at < 72 hours of age or between 12 and 21 days of age)

Secondary outcomes

BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age (requirement for supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age)

BPD at 28 days of age (requirement for supplemental oxygen at 28 days of age)

Need for ventilation amongst survivors at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

Duration of mechanical ventilation among survivors (days)

Duration of supplemental oxygen among survivors (days)

Length of hospital stay among survivors (days)

Intraventricular haemorrhage grade III‐IV (defined as per Papile 1978)

Periventricular leukomalacia (defined as cysts in the periventricular area on ultrasound or CT scan)

Hyperglycaemia (defined as blood glucose > 10 mmol/L) during the course of intervention

Hypertension (defined as systolic or diastolic blood pressure > 2 standard deviations (SD) above the mean for infant's gestational and postnatal age (Zubrow 1995)) during the course of intervention

Necrotising enterocolitis (Bell's stage II and III) (Bell 1978)

Gastrointestinal bleed (defined as presence of bloody nasogastric or orogastric aspirate)

Retinopathy of prematurity ≥ stage 3 (ICROP 1984)

Culture‐proven sepsis

Suppression of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis assessed by metyrapone or Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test

Patent ductus arteriosus defined by presence of clinical symptoms and signs or demonstration by echocardiography

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy defined as thickening of the intraventricular septum or of the left ventricular wall on echocardiography; sepsis defined by the presence of clinical symptoms and signs of infection and a positive culture from a normally sterile site

Pneumonia based on clinical and radiological signs and a positive endotracheal tube aspirate culture

Growth (weight, length/height and head circumference) at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age; cataracts (defined by presence of opacities in the lens)

Hypertrophy of the tongue

Nephrocalcinosis (defined by the presence of echo densities in the medulla of the kidney on ultrasound) (Saarela 1999)

Long‐term neurodevelopmental outcome (in surviving infants)

Neurodevelopmental impairment was defined as presence of cerebral palsy or mental impairment (Bayley scales of infant development, Mental Developmental Index < 70) or legal blindness (< 20/200 visual acuity) or deafness (aided or < 60 dB on audiometric testing) assessed at 18 to 24 months.

The following outcomes were reported at 7 years of age: these post‐hoc analyses were based on available data from a subsample of theHalliday 2001 study

British Ability Scales, Second Edition (provides a global measure of cognitive functioning (the general conceptual ability (GCA) score, with a standardised mean of 100 and SD of 15)

Activities, social, and school competency scales of the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) for children 4 to 18 years of age

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) from which overall behavioural, emotional, conduct, hyperactivity, and peer problem scores are derived

Cerebral palsy

Severe disability defined as GCA score of < 55, no independent walking, inability to dress or feed oneself, requirement for continuous home oxygen therapy, behavioural disturbance requiring constant supervision, no useful vision, or no useful hearing

Moderate disability was defined as a GCA score of 55 to 69, restricted mobility, admission to an ICU and ventilation within the past year, secondary referral for specialised help with behaviour, ability to see gross movement only or hearing loss not corrected with aid

Death or moderate/severe disability

Systolic blood pressure > 95th percentile

Diastolic blood pressure > 95th percentile

Ever diagnosed as asthmatic by 7 years of age

Severe disability defined as GCA score of < 55, no independent walking, inability to dress or feed oneself, requirement for continuous home oxygen therapy, behavioural disturbance requiring constant supervision, no useful vision, or no useful hearing

Moderate disability was defined as a GCA score of 55 to 69, restricted mobility, admission to an ICU and ventilation within the past year, secondary referral for specialised help with behaviour, ability to see gross movement only or hearing loss not corrected with aid

Death or moderate/severe disability

Systolic blood pressure > 95th percentile

Diastolic blood pressure > 95th percentile

Ever diagnosed as asthmatic by 7 years of age

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We used the criteria and standard methods of Cochrane and Cochrane Neonatal for the 2017 update (see the Cochrane Neonatal search strategy for specialized register).

We conducted a comprehensive search including: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2017, Issue 1) in The Cochrane Library; MEDLINE via PubMed (1 January 2011 to 23 February 2017); Embase (1 January 2011 to 23 February 2017); and CINAHL (1 January 2011 to 23 February 2017) using the following search terms: (bronchopulmonary dysplasia OR lung diseases OR chronic lung disease OR BPD OR CLD) AND ((anti‐inflammatory agents OR steroid* OR dexamethasone OR budesonide OR beclomethasone dipropionate OR flunisolide OR fluticasone propionate OR corticosteroid* OR betamethasone OR hydrocortisone) AND (inhalation OR aerosol OR inhale*)), plus database‐specific limiters for RCTs and neonates. See Appendix 1 for previous search methodologies and Appendix 2 for the full search strategies for each database searched for the 2017 update.

We searched clinical trials registries for ongoing or recently completed trials (clinicaltrials.gov; the World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP); and the ISRCTN Registry). We searched Abstracts2View for abstracts from the Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meetings from 2010 to 2016.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of identified trials.

Data collection and analysis

We used the methods of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group for data collection and analysis.

Selection of studies

Three review authors (SS, AO, VS) independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion of all potential studies identified as a result of the search.

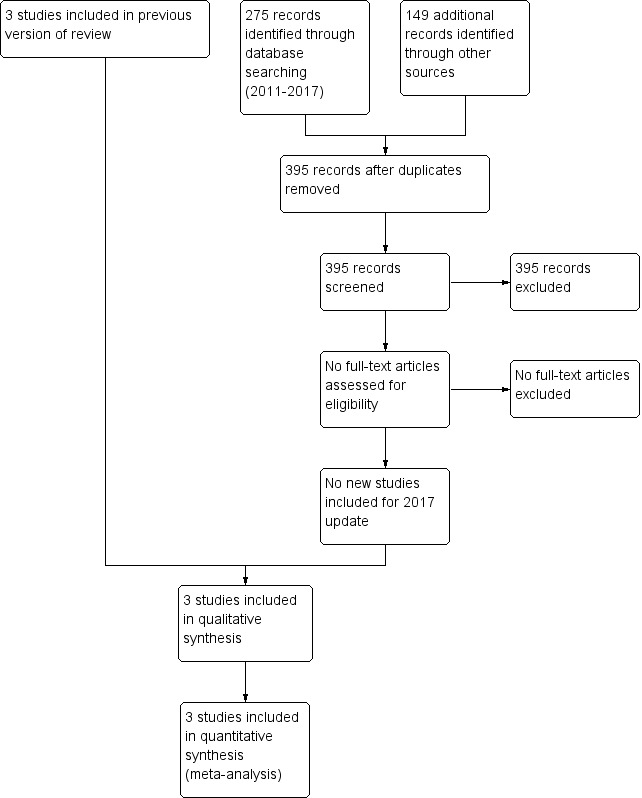

We retrieved full‐text study reports and three review authors (SS, AO, VS) independently screened the reports and identified studies for inclusion, and noted and recorded reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. We resolved disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a fourth review author (HH). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) and Characteristics of excluded studies. We did not impose any language restrictions

1.

Study flow diagram: review update

Data extraction and management

For each trial, information was sought regarding the method of randomisation, blinding and reporting of outcomes of all infants enrolled in the trial. Data from primary investigators were obtained for unpublished trials or when published data were incomplete. Retrieved articles were assessed and data extracted independently by four review authors (SS, VS, AO, HH). This update was performed by two review authors (VS, AO). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus.

For each study, data were entered into RevMan by one review author and checked for accuracy by a second reviewer author. We resolved discrepancies through discussion.

We attempted to contact authors of original reports to provide further details when information in published reports was unclear.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (VS, SS, AO) independently assessed the risk of bias (low, high, or unclear) of all included trials using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool (Higgins 2011) for the following domains:

Sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other bias.

Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by consulting a third review author. See Appendix 3 for a more detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Measures of treatment effect

We performed statistical analyses using Review Manager software (Review Manager 2014). Dichotomous data were analysed using relative risk (RR), risk difference (RD) and the number needed to benefit (NNTB) or number needed to harm (NNTH). The 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported for all estimates.

We analysed continuous data using weighted mean difference (WMD) or the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measured the same outcome but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

For clinical outcomes, such as episodes of sepsis, we analysed data as the proportion of neonates having one or more episodes.

Dealing with missing data

Levels of attrition were noted for the included studies. The impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect was explored by conducting sensitivity analyses.

All outcome analyses were on an intention‐to‐treat basis i.e. we included all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined heterogeneity among trials by inspecting the forest plots and quantifying the impact of heterogeneity using the I² statistic. If noted, we planned to explore the possible causes of statistical heterogeneity using prespecified subgroup analysis (e.g. differences in study quality, participants, intervention regimens, or outcome assessments). Heterogeneity tests, including the I² statistic, were performed to assess the appropriateness of pooling data. We used the following criteria to describe heterogeneity: < 25% no heterogeneity, ≥ 25% to 49% low heterogeneity, ≥ 50% to 74% moderate heterogeneity and ≥ 75% high heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess possible publication bias and other biases by inspecting the symmetry or asymmetry of funnel plots had there been at least 10 trials included in an analysis.

For included trials that were recently performed (and therefore prospectively registered), we explored possible selective reporting of study outcomes by comparing the primary and secondary outcomes in the reports with the primary and secondary outcomes proposed at trial registration, using the web sites www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.controlled‐trials.com. If such discrepancies were found, we planned to contact the primary investigators to obtain missing outcome data on outcomes pre‐specified at trial registration.

Data synthesis

Meta‐analysis was conducted using Review Manager software (Review Manager 2014). We used the Mantel‐Haenszel method for estimates of typical relative risk and risk difference. We analysed continuous measures using the inverse variance method. We used the fixed‐effect model for all meta‐analyses.

Quality of evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the quality of evidence for the following (clinically relevant) primary outcomes: death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age for infants randomised at < 72 hours of age and for infants randomised between 12 and 21 days of age. For secondary outcomes we included infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days; BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age; hyperglycaemia; hypertension. For infants randomised at < 72 hours of age we included the following outcomes at 7 years of age: general conceptual ability (GCA); moderate/severe disability; death or moderate/severe disability; systolic blood pressure > 95th percentile; diastolic blood pressure > 95th percentile; and ever diagnosed as asthmatic.

Three authors (VS, SS, AO) independently assessed the quality of the evidence for each of these outcomes. We considered evidence from randomised controlled trials as high quality but downgraded the evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations based upon the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of the evidence, precision of estimates and presence of publication bias. We used GRADEpro GDT to create ‘Summary of findings’ tables to report the quality of the evidence.

The GRADE approach results in an assessment of the quality of a body of evidence in one of four grades:

High: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Groups were analysed based on all randomised and survivors only.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses for situations where this might affect the interpretation of significant results (e.g. where there is risk of bias associated with the quality of some of the included trials or missing outcome data). However, it was determined this was unnecessary for this review.

Results

Description of studies

Three trials were identified and included in the previous review. The updated searches of databases and trials registers in 2017 identified a total of 427 records. After removal of duplicates, we assessed 395 records by title and abstract and excluded all 395 records. The study flow from the searches is illustrated in Figure 1. One study received grant support and the industry provided Aerochambers and metered dose inhalers of budesonide and placebo for the same study. No conflict of interest was identified.

Results of the search

Five trials comparing inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids in treatment of BPD were identified. Two trials (Dimitriou 1997; Nicholl 2002) were excluded as both included non ventilator‐dependent patients and the groups of ventilated infants could not be identified separately. No new studies were included for this update.

Included studies

Three trials fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the previous update of the review (Shah 2012a): Halliday 2001; Suchomski 2002 and Rozycki 2003. Although Rozycki 2003 enrolled preterm infants with birth weights between 650 g and 2000 g, on review of the published data, 93% of the enrolled infants had birth weights < 1000 g with postmenstrual age ranging from 23 to 31 weeks. Therefore, data from this trial were included in this review. Details of each trial are given in Characteristics of included studies.

Halliday 2001 enrolled infants born at < 30 weeks gestation, postnatal age < 72 hours, needing mechanical ventilation and fractional inspired oxygen concentration (FiO₂) > 0.30. Infants of 30 and 31 weeks gestation could also be included if they needed FiO₂ > 0.50. Infants with lethal congenital anomalies, severe intraventricular haemorrhage (grade 3 or 4), or proven systemic infection before entry were excluded from the trial. The trial was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of early (< 72 hours) or delayed (> 15 days) administration of systemic dexamethasone or inhaled budesonide. Infants were randomly allocated to one of four treatment groups in a factorial design: early (< 72 hours) dexamethasone, early budesonide, delayed selective (> 15 days) dexamethasone and delayed selective budesonide. Only the delayed budesonide and delayed dexamethasone groups are included in this review. Halliday 2001 randomised 142 babies to delayed selective budesonide and 150 to delayed selective dexamethasone groups. Budesonide was administered by metered dose inhaler and a spacing chamber at 400 µg/kg twice daily for 12 days. Dexamethasone was given intravenously (IV) or orally in a tapering course beginning with 0.5 mg/kg/day in two divided doses for three days reducing by half every three days for a total of 12 days of therapy. Delayed selective treatment was started if infants needed mechanical ventilation and more than 30% oxygen for > 15 days. Of 142 infants randomised to the delayed selective budesonide group, 33 received a full course, 21 received a partial course and 88 babies did not receive budesonide. Of 150 infants randomised to the delayed selective dexamethasone group, 35 received a complete course, 25 received a partial course and 90 infants did not receive dexamethasone. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. The primary outcome was death or oxygen dependency at 36 weeks. Secondary outcome measures included death or major cerebral abnormality, duration of oxygen treatment, and complications of preterm birth. Long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age were assessed in a sample from the UK and Ireland by assessors blinded to the treatment assignments.

Suchomski 2002 compared inhaled beclomethasone, either 400 or 800 µg/d, to intravenous dexamethasone in preterm infants dependent on conventional mechanical ventilation and supplemental oxygen at two weeks of age. The study included 78 preterm infants with birth weight ≤ 1500 g, gestational age ≤ 30 weeks and ventilatory dependence at 12 to 21 days of age with rate > 15/min and FiO₂ > 0.30 with a persistence of these ventilator settings for a minimum of 72 hours. Infants on high frequency ventilation were ineligible for inclusion in the study. Infants were excluded from the study if they had major congenital malformations, culture‐proven sepsis, hypertension or hyperglycaemia needing treatment, or persistent patent ductus arteriosus. Infants were randomly assigned to one of the three treatment groups: inhaled beclomethasone at 400 µg/d or 800 µg/d, or intravenous dexamethasone. Inhaled beclomethasone was continued until extubation. Post‐extubation the same dose was continued for another 48 hours. After that, the dose was halved every other day for six days, after which the steroids were stopped. Based on our inclusion criteria (to include all studies regardless of dosage of inhaled steroids), and because there was no significant difference in the effects of the two different doses, the two inhaled beclomethasone groups in Suchomski 2002 were combined to form one group in the present review. Intravenous dexamethasone was given as a 42 day tapering course starting with 0.5 mg/kg/day in two divided doses (Avery 1985). Cross‐over from either of the inhaled beclomethasone groups to intravenous dexamethasone was allowed if after four to five days of inhaled beclomethasone, the infant's ventilator and oxygen support had not decreased and the attending neonatologist felt that the infant could benefit from intravenous dexamethasone. It was reported that 18 infants from the inhaled steroid group crossed over to systemic dexamethasone. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed by the investigators. Outcome measures included adverse effects including sepsis, hypertension and hyperglycaemia; short‐term ventilatory requirements, duration of mechanical ventilation, duration of supplemental oxygen, length of stay in the hospital and need for respiratory support at 28 days or 36 weeks' postmenstrual age. Deaths at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age were not reported. For infants completing a 10 day course of either inhaled or intravenous steroids, an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test was done two weeks after completion of the steroid course.

Rozycki 2003 enrolled 61 preterm infants with birth weights between 650 g and 2000 g who at 14 days of age were at significant risk of developing moderate to severe BPD (defined as the need for mechanical ventilation and oxygen) with x‐ray changes beyond 28 days of life. Infants with culture‐proven sepsis and who were receiving FiO₂ of ≥ 0.30 were eligible if they had a ventilatory index (10,000/ventilator rate x peak pressure x pCO₂) of < 0.8. Infants without previous sepsis were eligible if the ventilatory index was < 0.51. Infants meeting these criteria had a 75% risk of developing moderate‐severe BPD. Infants with the following were excluded: pre‐existing hyperglycaemia with blood glucose > 200 mg/dL for > 24 hours, hypertension with systolic pressures > 70 to 90 mm Hg, depending on birth weight, surgery within previous seven days, active bacterial infection unless repeat blood, urine or cerebrospinal fluid cultures were sterile after 72 hours of antibiotics, thrombocytopenia with platelet count < 100,000, any gastrointestinal bleeding within the previous seven days, significant weaning from ventilator support in the previous three days and previous exposure to postnatal steroids. Eligibility was determined at 14 days of age but the study could be delayed up to six days while awaiting resolution of infections. Infants were randomised to the following four groups: Group A: aerosol placebo‐systemic dexamethasone; Group B: high beclomethasone‐systemic placebo; Group C: medium beclomethasone‐systemic placebo; and Group D: low beclomethasone‐systemic placebo. Those receiving aerosol steroids who remained ventilator‐dependent after seven days were switched to standard 42‐day tapering doses of systemic dexamethasone. The primary outcome variable was extubation within the first seven days of the study. Secondary outcome measures included: changes in ventilatory settings and oxygen delivery over the first seven days, the incidence of hypertension, hyperglycaemia, infection and growth.

Excluded studies

We excluded two trials (Dimitriou 1997; Nicholl 2002). Both trials included non ventilator‐dependent participants and the groups of ventilated infants could not be identified separately. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Studies awaiting classification

There are no studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

Our searches did not find any ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

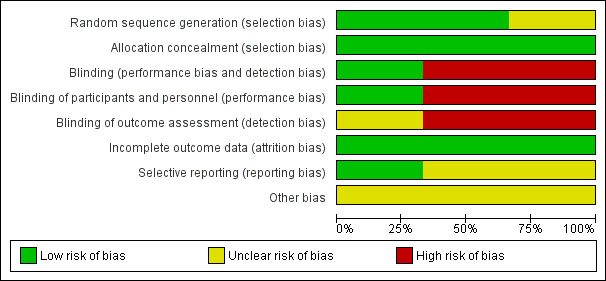

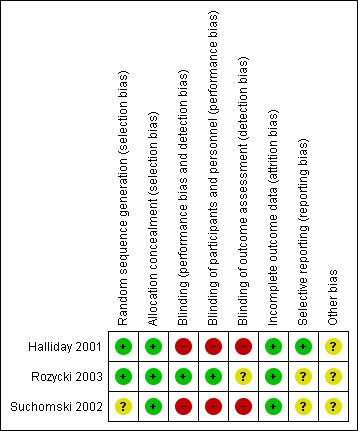

The risk of bias in the included trials are illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

The risk of bias is taken into account in the 'Summary of findings' tables for the primary outcome and important secondary outcomes (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4). Reasons for downgrading the quality of evidence is explained in the comments columns in 'Summary of findings' tables.

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Inhaled steroids compared with systemic steroids for BPD (infants randomised at < 72 hours of age).

| Inhaled steroids compared with systemic steroids for BPD (infants randomised at < 72 hours of age) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Neonates with developing BPD Settings: Neonatal intensive care unit Intervention: Inhaled steroids Comparison: Systemic steroids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Systemic steroids | Inhaled steroids | |||||

| Death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age | High risk population | RR 1.04 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.26) | 292 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Bias: The risk of bias for this single study was high. The study was not blinded at all sites. Only 35/150 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 33/142 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. Results were presented in intention to treat analyses including deaths occurring after 72 hours of age. We downgraded the quality of the evidence by one step.

Heterogeneity/consistency: Heterogeneity was N/A as there was only one study included in the analysis.

Directness of the evidence: The study was conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

|

| 580 per 1000 | 606 per 1000 | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; BPD: Bronchopulmonary dysplasia; N/A: Not applicable | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Summary of findings 2. Inhaled steroids compared with systemic steroids for BPD (infants randomised between 12 and 21 days of age).

| Inhaled steroids compared with systemic steroids for BPD (infants randomised between 12 and 21 days of age) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Neonates with developing BPD Settings: Neonatal intensive care unit Intervention: Inhaled steroids Comparison: Systemic steroids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Systemic steroids | Inhaled steroids | |||||

| Death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age | High risk population | RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.05) | 78 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Bias: The risk of bias for this single study was high. There was no blinding of the intervention or outcome measurements. We downgraded the quality of the evidence by one level.

Heterogeneity/consistency: Heterogeneity was N/A as there was only one study included in the analysis.

Directness of the evidence: The study was conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: The precision for the point estimate was low as the sample size was small Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

|

| 963 per 1000 | 902 per 1000 | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; BPD: Bronchopulmonary dysplasia; N/A: Not applicable | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Summary of findings 3. Inhaled steroids compared with systemic steroids for BPD (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age).

| Inhaled steroids compared with systemic steroids for BPD (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Neonates with developing BPD Settings: Neonatal intensive care unit Intervention: Inhaled steroids Comparison: Systemic steroids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Systemic steroids | Inhaled steroids | |||||

| BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age | High risk population | RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.32) | 429 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Bias: The risk of bias for these three studies was high. There was blinding of randomisation in all three studies. There was no blinding of the intervention or outcome measurements at all sites in the largest study (Halliday 2001). In Rozycki 2003 there was blinding of the intervention but blinding of outcome assessment was unclear. In Suchomski 2002 there was no blinding of the intervention or outcomes measurements. We downgraded the quality of the evidence by two levels.

Heterogeneity/consistency: Heterogeneity was low (I² = 39%).

Directness of the evidence: The studies were conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: The precision for the point estimate was high as the sample size was quite large. Presence of publication bias: N/A. We did not create a funnel plot as there were only three trials included in the analysis. |

|

| 422 per 1000 | 485 per 1000 (394 to 776) | |||||

| Hyperglycaemia | High risk population | RR 0.86 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.22) | 429 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Bias: The risk of bias for these three studies was high. There was blinding of randomisation in all three studies. There was no blinding of the intervention or outcome measurements at all sites in the largest study (Halliday 2001). In Rozycki 2003 there was blinding of the intervention but blinding of outcome assessments was unclear. In Suchomski 2002 there was no blinding of the intervention or outcome measurements. We downgraded the quality of the evidence by two levels. Heterogeneity/consistency: There was no heterogeneity (I² = 8%). Directness of the evidence: The studies were conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: The precision for the point estimate was high as the sample size was quite large. Presence of publication bias: N/A. We did not create a funnel plot as there were only three trials included in the analysis. |

|

| 255 per 1000 | 177 per 1000 (0 to 282) | |||||

| Hypertension | High risk population | RR (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.01) | 429 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Bias: The risk of bias for these three studies was high. There was blinding of randomisation in all three studies. There was no blinding of the intervention or outcome measurements at all sites in the largest study (Halliday 2001). In Rozycki 2003 there was blinding of the intervention but blinding of outcome assessments was unclear. In Suchomski 2002 there was no blinding of the intervention or outcome measurements. We downgraded the quality of the evidence by two steps. Heterogeneity/consistency: There was no heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Directness of the evidence: The studies were conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: The precision for the point estimate was high as the sample size was quite large. Presence of publication bias: N/A. We did not create a funnel plot as there were only three trials included in the analysis. |

|

| 604 per 1000 | 430 per 1000 (130 to 627) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; BPD: Bronchopulmonary dysplasia; N/A: Not applicable | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Summary of findings 4. Inhaled steroids compared with systemic steroids for BPD ‐ long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours of age).

| Inhaled steroids compared with systemic steroids for BPD ‐ long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours of age) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Neonates with developing BPD Settings: NICU Intervention: Inhaled steroids Comparison: Systemic steroids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Systemic steroids | Inhaled steroids | |||||

|

General conceptual ability (GCA) score at 7 years The test has a standardisation mean of 100 and SD of 15 |

The mean GCA score in the control group was 90.2 | The mean GCA score in the intervention groups was 3.4 units lower | MD ‐3.40 (95% CI ‐12.38 to 5.58) | 74 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Bias: The risk of bias for this outcome was low. This outcome was reported in a subset of infants, who had been enrolled in the trial in Ireland and the UK. The assessors of all the long‐term outcomes were blinded to the original treatment group allocation. Heterogeneity/consistency: Heterogeneity was N/A as there was only one study included in the analysis. Directness of the evidence: The study was conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was low because of the small sample size. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

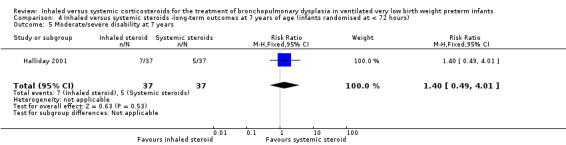

| Moderate/severe disability at 7 years | 135 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 | RR 1.40 (95% CI 0.49 to 4.01) | 74 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Bias: The risk of bias for this outcome was low. This outcome was reported in a subset of infants, who had been enrolled in the trial in Ireland and the UK. The assessors of all the long‐term outcomes were blinded to the original treatment group allocation. Heterogeneity/consistency: Heterogeneity was N/A as there was only one study included in the analysis. Directness of the evidence: The study was conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was low because of the small sample size. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

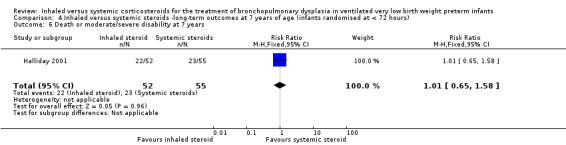

| Death or moderate/severe disability at 7 years | 418 per 1000 | 423 per 1000 | RR 1.01 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.58) | 107 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Bias: The risk of bias for this outcome was low. This outcome was reported in a subset of infants, who had been enrolled in the trial in Ireland and the UK. The assessors of all the long‐term outcomes were blinded to the original treatment group allocation. Heterogeneity/consistency: Heterogeneity was N/A as there was only one study included in the analysis. Directness of the evidence: The study was conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was low because of the small sample size. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

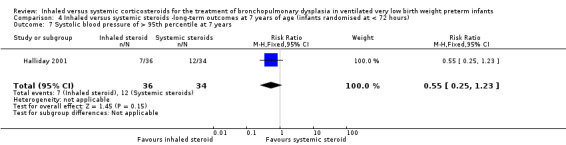

| Systolic blood pressure > 95th percentile at 7 years | 353 per 1000 | 194 per 1000 | RR 0.55 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.23) | 70 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Bias: The risk of bias for this outcome was low. This outcome was reported in a subset of infants, who had been enrolled in the trial in Ireland and the UK. The assessors of all the long‐term outcomes were blinded to the original treatment group allocation. Heterogeneity/consistency: Heterogeneity was N/A as there was only one study included in the analysis. Directness of the evidence: The study was conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was low because of the small sample size. We downgraded the quality of the evidence by one step. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

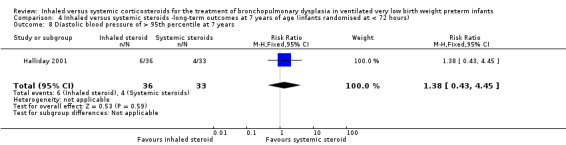

| Diastolic blood pressure > 95th percentile at 7 years | 121 per 1000 | 167 per 1000 | RR (1.38, 95% CI 0.43 to 4.45) | 69 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Bias: The risk of bias for this outcome was low. This outcome was reported in a subset of infants, who had been enrolled in the trial in Ireland and the UK. The assessors of all the long‐term outcomes were blinded to the original treatment group allocation. Heterogeneity/consistency: Heterogeneity was N/A as there was only one study included in the analysis. Directness of the evidence: The study was conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was low because of the small sample size. We downgraded the quality of the evidence by one step. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

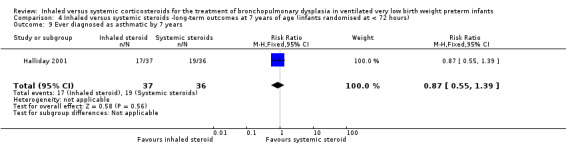

| Ever diagnosed as asthmatic by 7 years | 528 per 1000 | 459 per 1000 | RR 0.87 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.39) | 73 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Bias: The risk of bias for this outcome was low. This outcome was reported in a subset of infants, who had been enrolled in the trial in Ireland and the UK. The assessors of all the long‐term outcomes were blinded to the original treatment group allocation. Heterogeneity/consistency: Heterogeneity was N/A as there was only one study included in the analysis. Directness of the evidence: The study was conducted in the target population of newborn infants. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was low because of the small sample size. We downgraded the quality of the evidence by one step. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; BPD: Bronchopulmonary dysplasia; NICU: Neonatal intensive care unit; N/A: Not applicable | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

There were elements of risk of bias in the three included studies. For details see the information below.

Allocation

In the study by Halliday 2001 after identifying an eligible infant, the clinician telephoned the randomisation centre to enrol the infant and to determine the treatment group (low risk of bias).

Suchomski 2002 was a prospective randomised controlled trial. Three sets of 27 cards were assembled followed by placement of one card each into one of 81 opaque envelopes. As infants were enrolled, a card was sequentially pulled and the infant assigned to the appropriate study group (low risk of bias).

Rozycki 2003 was a prospective randomised double‐blind controlled trial. The infants were randomised using a random table number and only the pharmacy was aware of the individual group assignment (low risk of bias).

Blinding

Halliday 2001 was a multi‐centre RCT involving 47 centres. The interventions and outcome measures were not blinded in all the centres (high risk of bias). However, in 11 centres the trial was conducted double blind. In these centres, placebo metered dose inhalers and intravenous saline were used to mask treatment allocation. Comparisons were made for the primary outcome variables between the centres observing double blind strategy and the other centres. The long‐term assessments at 7 years of age were performed by assessors blinded to the group assignments (low risk of bias).

In Suchomski 2002 blinding of the intervention was not performed (high risk of bias). Blinding of outcome measurement was not ensured (high risk of bias). Cross‐over from inhaled steroid groups to intravenous dexamethasone was allowed at the discretion of attending neonatologist.

In Rozycki 2003 blinding of intervention was performed (low risk of bias). Blinding of outcome measurement was unclear (unclear risk of bias).

Incomplete outcome data

There was complete follow up of all randomised infants in all three studies (low risk of bias in all three studies).

Selective reporting

There was no selective reporting in the trial by Halliday 2001 (low risk of bias ). The protocols for the other trials were not available, so we can not judge if there were any deviations or not.

Other potential sources of bias

We are not aware of any other sources of bias in the included trials (unclear risk).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Halliday 2001 randomised infants at < 72 hours of age; Suchomski 2002 randomised infants at 12 to 21 days; and Rozycki 2003 randomised after 14 days of age. All trials reported outcomes from the age of randomisation. Although infants received steroids after the first two weeks of life in all trials, the time period over which outcomes were measured differed among studies. Data from all three trials were combined for meta‐analyses of secondary outcomes (Halliday 2001; Suchomski 2002; Rozycki 2003).

For outcomes that included death we performed separate analyses for Halliday 2001 which reported on deaths from randomisation at < 72 hours and we combined results from Suchomski 2002 and Rozycki 2003.

1. Inhaled versus systemic steroids among infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (infants randomised at < 72 hours of age)

Because only Halliday 2001 was included in these analyses, tests for heterogeneity were not applicable.

Primary outcome

Death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

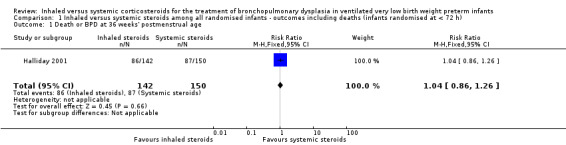

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups for the combined outcome of death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.26; RD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.14; 1 study, N = 292; Analysis 1.1; moderate‐quality evidence).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (infants randomised at < 72 h), Outcome 1 Death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

Secondary outcomes

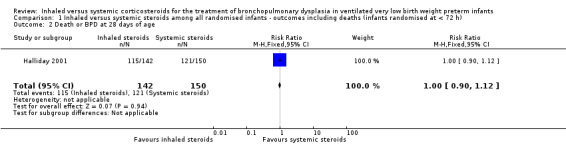

Death or BPD at 28 days of age

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups for the combined outcome of death or BPD at 28 days of age (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.12; RD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.09; 1 study, N = 292; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (infants randomised at < 72 h), Outcome 2 Death or BPD at 28 days of age.

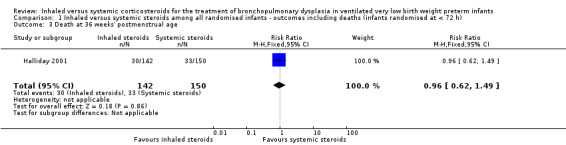

Death at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

There was no statistically significant effect on death at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age between groups (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.49; RD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.09; 1study, N = 292; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (infants randomised at < 72 h), Outcome 3 Death at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

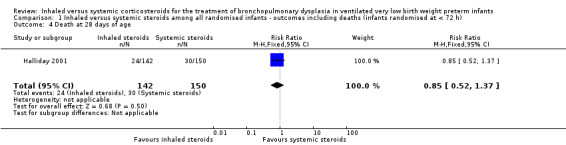

Death at 28 days of age

No statistically significant effect on mortality by 28 days was noted between the groups (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.37; RD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.06; 1 study, N = 292; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (infants randomised at < 72 h), Outcome 4 Death at 28 days of age.

2. Inhaled versus systemic steroids among infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (infants randomised between 12 and 21 days of age)

Because only Suchomski 2002 was included in these analyses, tests for heterogeneity were not applicable. Rozycki 2003 did not report on deaths at 36 weeks' PMA or at 28 days of age.

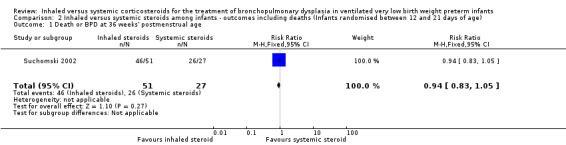

Primary outcome

Death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

There was no statistically significant difference between groups for the combined outcome of death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.05; RD ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.05; 1 study, N = 78; Analysis 2.1; low‐quality evidence).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (Infants randomised between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 1 Death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

Secondary outcomes

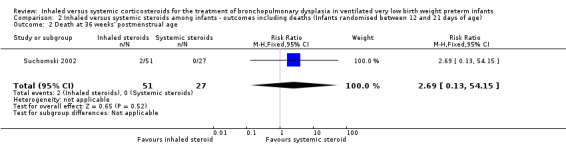

Death at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

There was no statistically significant effect on death at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age between groups (RR 2.69, 95% CI 0.13 to 54.15; RD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.12; 1 study, N = 78; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (Infants randomised between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 2 Death at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

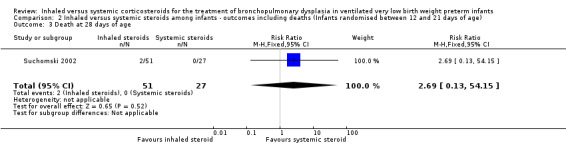

Death at 28 days of age

No statistically significant effect on mortality by 28 days was noted between groups (RR 2.69, 95% CI 0.13 to 54.15; RD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.12; 1 study, N = 78; Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among infants ‐ outcomes including deaths (Infants randomised between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 3 Death at 28 days of age.

3. Inhaled versus systemic steroids among infants ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours of age or between 12 and 21 days of age)

Secondary outcomes

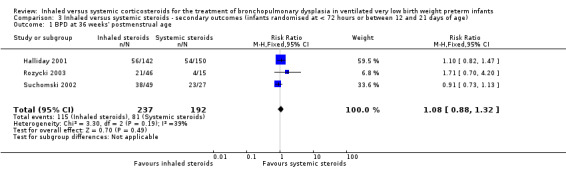

BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age in the inhaled steroid compared to systemic steroid group (typical RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.32; typical RD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.12; 3 studies, N = 429; Analysis 3.1; low‐quality evidence). There was low heterogeneity for both RR (39%) and RD (28%).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 1 BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

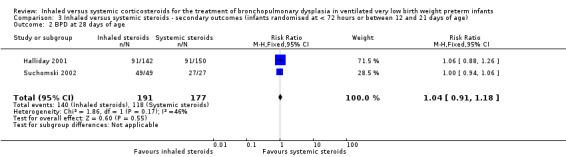

BPD at 28 days of age

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of BPD at 28 days between groups (typical RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.18; typical RD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.12; 2 studies, N = 368; Analysis 3.2). There was low heterogeneity for both RR (46%) and RD (0 %).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 2 BPD at 28 days of age.

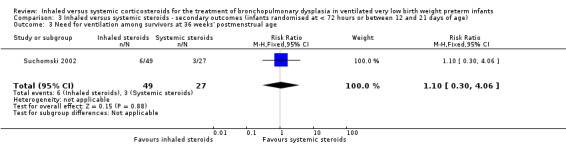

Need for ventilation amongst survivors at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

There was no statistically significant difference for this outcome between groups (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.30 to 4.06; RD 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.16; 1 study, N = 76; Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 3 Need for ventilation among survivors at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

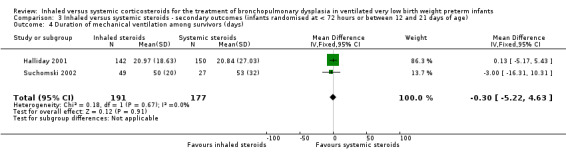

Duration of mechanical ventilation among survivors (days)

The duration of mechanical ventilation was not statistically significantly different between groups (typical WMD ‐ 0.3 days, 95% CI ‐5.2 to 4.6; 2 studies, N = 368; Analysis 3.4). There was no heterogeneity for WMD (0%).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 4 Duration of mechanical ventilation among survivors (days).

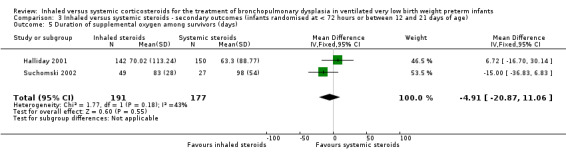

Duration of supplemental oxygen among survivors (days)

The duration of supplemental oxygen was not statistically significantly different between groups (typical WMD ‐4.91 days, 95% CI ‐21 to 11; 2 studies, N = 368; Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 5 Duration of supplemental oxygen among survivors (days).

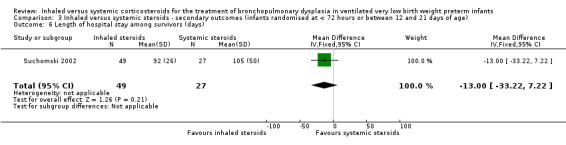

Length of hospital stay among survivors (days)

There was no statistically significant difference in the length of hospital stay among survivors between groups (MD ‐13, 95% CI ‐33 to 7; 1 study, N = 76; Analysis 3.6). Test for heterogeneity not applicable.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 6 Length of hospital stay among survivors (days).

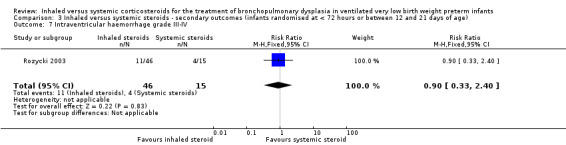

Intraventricular haemorrhage grade III‐IV

There was no statistically significant difference in length of hospital stay among survivors between groups (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.40; RD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.23; 1 study, N = 61; Analysis 3.7). Test for heterogeneity not applicable.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 7 Intraventricular haemorrhage grade III‐IV.

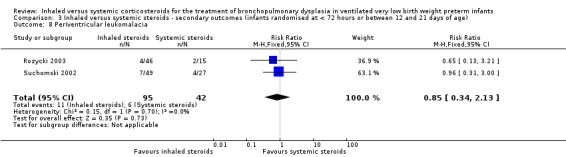

Periventricular leukomalacia

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of periventricular leukomalacia between groups (typical RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.13; typical RD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.10; 2 studies, N = 137; Analysis 3.8). There was no heterogeneity for either RR (0%) or RD (0%).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 8 Periventricular leukomalacia.

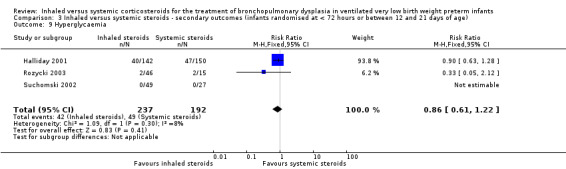

Hyperglycaemia

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of hyperglycaemia between groups (typical RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.22; typical RD ‐0.03, ‐0.11 to 0.05; 3 studies, N = 429; Analysis 3.9; low‐quality evidence). There was no heterogeneity for either RR (8%) or RD (0 %).

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 9 Hyperglycaemia.

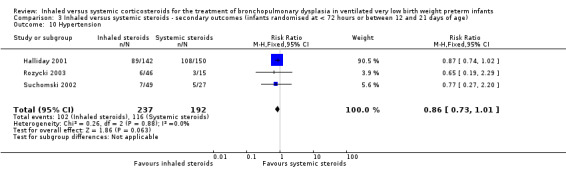

Hypertension

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of hypertension between groups (typical RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.01; typical RD ‐0.08, 95% Ci ‐0.17 to 0.00; 3 studies, N = 429; Analysis 3.10; low‐quality evidence). There was no heterogeneity for either RR (0%) or RD (0%).

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 10 Hypertension.

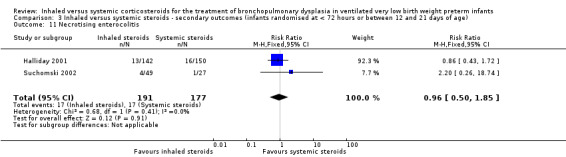

Necrotising enterocolitis

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of necrotising enterocolitis between groups (typical RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.85; typical RD ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.06; 2 studies, N = 368; Analysis 3.11). There was no heterogeneity for either RR (0%) or RD (0%).

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 11 Necrotising enterocolitis.

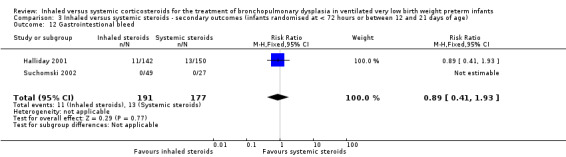

Gastrointestinal bleed

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of gastrointestinal bleed between groups (typical RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.93; typical RD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.04; 2 studies, N = 368; Analysis 3.12). As there were no outcomes in either group in one trial, test for heterogeneity for RR was not applicable. There was no heterogeneity for RD (0%).

3.12. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 12 Gastrointestional bleed.

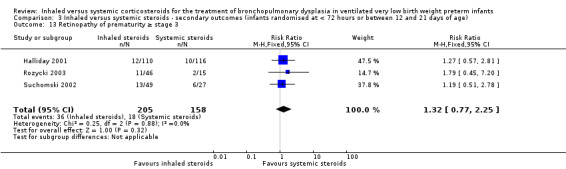

Retinopathy of prematurity ≥ stage 3

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of retinopathy of prematurity between groups (typical RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.77 to 2.25; typical RD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.11; 3 studies, N = 363; Analysis 3.13). There was no heterogeneity for either RR (0%) or RD (0%).

3.13. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 13 Retinopathy of prematurity ≥ stage 3.

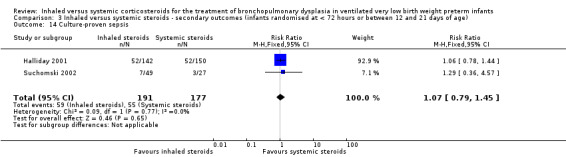

Culture‐proven sepsis

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of culture‐proven sepsis between groups (typical RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.45; RD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.12; 2 studies, N = 368; Analysis 3.14). There was no heterogeneity for either RR (0%) or RD (0%).

3.14. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐ secondary outcomes (infants randomised at < 72 hours or between 12 and 21 days of age), Outcome 14 Culture‐proven sepsis.

Other outcomes

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test

Suchomski 2002 reported that the ACTH test was completed for 24 infants. The baseline cortisol levels before the ACTH stimulation test for the 800 µg/d inhaled group (3 ± 2.3 µg/dL; N = 7) and the intravenous group (1.6 ± 1.3 µg/dL; N = 10) were statistically significantly lower than for the 400 µg/d inhaled group (7.3 ± 4.2 µg/dL; N = 7). However, the response to ACTH (i.e. relative rise in cortisol level) was similar in all three groups: 12 ± 5.7 µg/dL in the 400 µg/d inhaled group, 15.6 ± 8.5 µg/dL in the 800 µg/d inhaled group and 10.7 ± 4.6 µg/dL in the intravenous group, P = 0.408. Post ACTH stimulation cortisol levels were 18.4 ± 8.0 µg/dL in the 800 µg/d inhaled group, 19.3 ± 5.9 µg/dL in the 400 µg/d inhaled group and 12.3 ± 5.7 µg/dL in the intravenous group, P = 0.048.

No relevant data for the following outcomes were available for analysis: measurement of pulmonary functions, growth at 36 week PMA, nephrocalcinosis, hypertrophy of tongue, cataract, pneumonia or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

4. Inhaled versus systemic steroids among children at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours of age)

A subset of infants enrolled in the OSECT study (Halliday 2001) were followed to a median age of 7 years. The study followed 127 (84%) of 152 survivors from the United Kingdom and Ireland. Of these, 75 children belonged to the late budesonide and late dexamethasone groups; 38 children belonged to the late budesonide group; and 37 children to the late dexamethasone group.

Tests for heterogeneity were not applicable to any of these analyses because only one study was included in each analysis.

There were no statistically significant differences between the early inhaled and the early systemic corticosteroid groups for the following outcomes in the Halliday 2001 study which reported on 75 children.

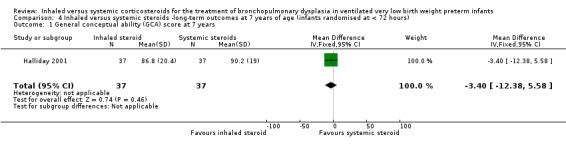

General conceptual ability score at 7 years

There was no significant difference between the groups of infants who received inhaled or systemic steroids (MD ‐3.40, 95% CI ‐12.38 to 5.58; 1 study, N = 74; Analysis 4.1; moderate‐quality evidence).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours), Outcome 1 General conceptual ability (GCA) score at 7 years.

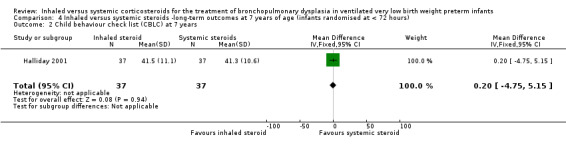

Child Behaviour Checklist at 7 years

There was no significant difference between the groups of infants who received inhaled or systemic steroids (MD 0.20, 95% CI ‐4.75 to 5.15; 1 study, N = 74; Analysis 4.2; moderate‐quality evidence).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours), Outcome 2 Child behaviour check list (CBLC) at 7 years.

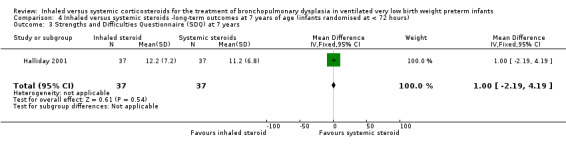

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire at 7 years

There was no significant difference between the groups of infants who received inhaled or systemic steroids, (MD 1.00, 95% CI ‐2.19 to 4.19; 1 study, N = 74; Analysis 4.3; moderate‐quality evidence).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours), Outcome 3 Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) at 7 years.

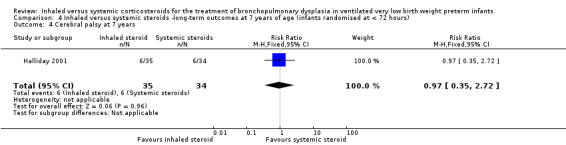

Cerebral palsy at 7 years

There was no significant difference between the groups of infants who received inhaled or systemic steroids (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.35 to 2.72; RD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.17; 1 study, N = 69; Analysis 4.4; moderate‐quality evidence).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours), Outcome 4 Cerebral palsy at 7 years.

Moderate/severe disability at 7 years

There was no significant difference between the groups of infants who received inhaled or systemic steroids (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.49 to 4.01; RD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.22; 1 study, N = 74; Analysis 4.5; moderate‐quality evidence).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours), Outcome 5 Moderate/severe disability at 7 years.

Death or moderate/severe disability at 7 years

There was no significant difference between the group who received inhaled steroids versus the group who received systemic steroids (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.58; RD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.19; 1 study, N = 107; Analysis 4.6; moderate‐quality evidence).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours), Outcome 6 Death or moderate/severe disability at 7 years.

Systolic blood pressure > 95th percentile at 7 years

There was no significant difference between the groups of infants who received inhaled or systemic steroids (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.23; RD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.05; 1 study, N = 70; Analysis 4.7; moderate‐quality evidence).

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours), Outcome 7 Systolic blood pressure of > 95th percentile at 7 years.

Diastolic blood pressure > 95th percentile at 7 years

There was no significant difference between the groups of infants who received inhaled or systemic steroids (RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.43 to 4.45; RD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.21; 1 study, N = 69; Analysis 4.8; moderate‐quality evidence).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours), Outcome 8 Diastolic blood pressure of > 95th percentile at 7 years.

Ever diagnosed with asthma by 7 years

There was no significant difference between the groups who received inhaled or systemic steroids (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.39; RD ‐0.07, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.16; 1 study, N = 73; Analysis 4.9; moderate‐quality evidence).

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Inhaled versus systemic steroids ‐long‐term outcomes at 7 years of age (infants randomised at < 72 hours), Outcome 9 Ever diagnosed as asthmatic by 7 years.

Discussion

Summary of main results