Summary

Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) is a common method for the fast identification of hit structures at the beginning of a medicinal chemistry program in drug discovery. The SBVS, described in this manuscript, is focused on finding small molecule hits that can be further utilized as a starting point for the development of inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP-13) via structure-based molecular design. We intended to identify a set of structurally diverse hits, which occupy all subsites (S1’-S3’, S2, and S3) centering the zinc containing binding site of MMP-13, by the virtual screening of a chemical library comprising more than 10 million commercially available compounds. In total, 23 compounds were found as potential MMP-13 inhibitors using Glide docking followed by the analysis of the structural interaction fingerprints (SIFt) of the docked structures.

Keywords: Matrix Metalloproteinase, structure-based virtual screening, docking, structural interaction fingerprints, Zn-chelating inhibitor

1. Introduction

The identification of a lead structure usually initiates a medicinal chemistry program in drug discovery. Traditionally, high-throughput screenings (HTS) of large compound libraries are used to deliver lead compounds for a certain protein target. The resultant small molecule leads need to be optimized through iterative analog synthesis efforts. The high costs and low hit rates associated with HTS screening campaigns as well as a steadily increasing number of new drug targets accelerated the development of cheaper and faster computational alternatives starting in the early 1990s. (1,2) Nowadays, virtual screening (VS) methods are broadly used in early-stage drug discovery for hit identification by analyzing chemical databases.

There are two different approaches, ligand- and receptor-based VS, used to prioritize compounds for synthesis and evaluation. The ligand-based approach tries to find molecules with similar physical and chemical properties to already known protein ligands. On the other hand, the receptor-based approach, also known as structure-based VS (SBVS), is not biased by known protein interaction partners. The screening starts with the 3-D structure of a target protein and a 3-D database of ligands. After virtual filtering of the compound library, the predictive binding mode of the lead structures are found by docking and the hits are scored by evaluating their binding affinities to the protein target. (3)

Within this manuscript we describe a SBVS aimed at finding new lead compounds capable of inhibiting the zinc-dependent matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP-13). MMP-13 is an extremely promising drug target for the treatment of osteoarthritis (OA). This protease is mainly responsible for the cleavage of collagen type II, which leads to the destruction of articular cartilage, one of the main symptoms of OA. (4) MMP-13 is also involved in cancer progression. The proteolytic degradation of the extracellular environment in melanoma invasion and metastasis is dependent on the stromal expression of MMP-13. (5) In breast cancer, metastasis to the bone is a very common mechanism for secondary tumor growth. Breast cancer cells manipulate signaling pathways in osteoblasts, leading to increased MMP-13 release, which promotes metastatic invasion to bone tissue. (6)

1.1. Matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets

MMP activity was described for the first time in 1962 as an enzymatic player in the metamorphosis process of tadpoles. Since then, 24 structurally and functionally related MMPs have been found in mammals. MMPs are characterized by a Zn2+-cation in their enzyme active site, which is coordinated by three histidines followed by a conserved methionine residue. Under healthy conditions, MMPs are very important regulators of cellular activities and physiological processes including reproduction, tissue remodeling, embryogenesis and angiogenesis via the degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components. MMPs can also influence the immune system by directly cleaving signaling molecules including the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and other cytokines. MMP activity is very low under healthy conditions but can be detected during repair or remodeling processes including angiogenesis, bone development or wound healing, as well as in inflamed tissue. (7)

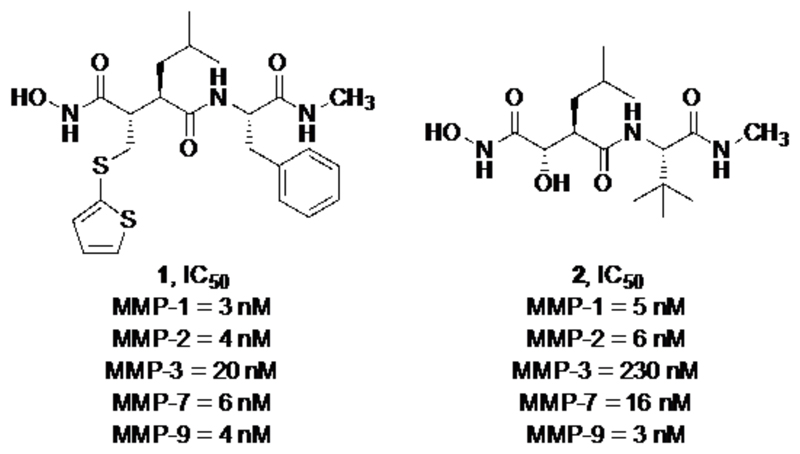

Originally, MMPs attracted the attention of numerous research groups due to their involvement in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. First-generation MMP inhibitors, developed in the early 1990s, were generally not selective for any particular MMP. Drug candidates resultant from these early programs were designed to mimic peptide sequences of collagen. These peptidomimetics also consisted of a functional group capable of chelating the active site zinc within the MMP active site in a competitive manner. Zinc chelating functionalities include the carboxylate-, carbamate-, thiol-, and hydroxamate group as well as phosphoric acid derivatives. The broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors and hydroxamic acid containing peptidomimetics, Batimastat (1) and Marimastat (2), were the first MMP inhibitors that entered clinical testing for cancer therapy. Clinical trials were suspended in phase III due to musculoskeletal toxicities resultant from non-selective binding of the inhibitors within the MMP family. (8)

Broad-spectrum MMP inhibition is common among MMP inhibitors due to the high structural homology among the active sites between MMP isoforms (Fig. 1). To circumvent this difficulty, recent research has switched to target alternative, less conserved allosteric sites with non-zinc chelating small molecules. The reports of co-crystal structures of MMPs with bound ligands could demonstrate that the significant structural differences within this highly conserved protein family lie in the conformation of surface loops (S1-S3 and S1’-S3’ subsites), which surround the catalytically active zinc ion. (9) Additionally, the development of isoform selective MMP inhibitors was aided by the discovery of the S1’* specificity loop, which is a hydrophobic pocket located adjacent to the S1’ subsite that shows the highest sequence variability within the MMP family. In the case of MMP-13, the S1’/S1’* subsite forms a very deep hydrophobic pocket that is enclosed at one end by a lysine residue. (10,11)

Figure 1.

Broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors.

1.2. MMP-13 in drug discovery

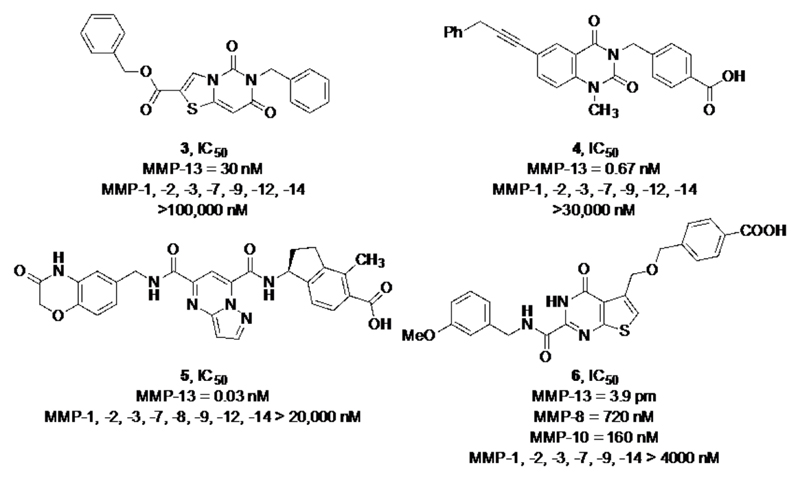

During the past 15 years, several highly potent and selective non-zinc chelating inhibitors targeting the S1’/S1’* subsite of MMP-13 were developed and several have entered clinical trials for the treatment of osteoarthritis. In the early 2000s, the first highly selective non-zinc chelating MMP-13 inhibitors, 3 and 4 (Fig. 2), were identified as part of a HTS campaign followed by an extensive structure activity relationship (SAR) study. (12) X-ray co-crystal structures revealed that the dynamic movement of the S1’ pocket seems essential for enzymatic turnover and the two compounds block enzymatic activity simply by inducing rigidity in the S1’ subsite and its adjacent S1’* specificity loop. The highly potent inhibitors 3 and 4 entered preclinical trials but had to be discontinued unexpectedly because both compounds induced renal toxicity in cynomolgus monkeys. (13,14)

Figure 2.

Non-zinc chelating MMP-13 inhibitors

In 2011, Baragi et al. from Alantos Pharmaceuticals reported the discovery and evaluation of compound 5 for intra-articular (IA) treatment of OA. In a manner analogous to compounds 3 and 4, this compound binds deep within the S1’ pocket and additionally interacts with the S1’* specificity loop. An impressive 20,000-fold selectivity for 5 was observed after assaying the activity of the compound against a broad panel of MMPs (Fig. 2). Compound 5 also exhibited a remarkable half-life in rat knee joints after IA injection. The concentration of 5 in cartilage was > 2 μM after 8 weeks following a single treatment. (15)

Kori et al. from Takeda published the activity of compound 6, which binds in the same binding mode as the compounds described before (3-5) and exhibits excellent potency and selectivity for MMP-13 relative to other MMPs. The oral bioavailability of compound 6 in different species (rats, guinea pigs, rabbits, beagle dogs and cynomolgus monkeys) could be significantly improved by using the monosodium salt of the carboxylic acid functionality of this compound. Furthermore, the authors demonstrated that oral administration of the monosodium salt induced a significant reduction of a cartilage marker (C-telopeptide of type II collagen (CTX-II)) of OA, after inducing OA symptoms by injecting monoiodoacetic acid (MIA) into the rat knee joint. (16)

Despite these extremely promising preclinical results, no further improvements of compounds 5 and 6 or clinical trials using these compounds have been published in the literature and no MMP-13 inhibitor has achieved FDA approval thus far. The community continues to search for a disease-modifying anti-OA agent. However, the promising anti-cancer activities of MMP-13 inhibitors merit further investigation.

In the following section, a SBVS for MMP-13 is described. The SBVS is focused on the identification of small molecule hits that can be further utilized as starting points for the development of MMP inhibitors via structure-based molecular design. Therefore, we sought to identify structurally diverse hits, which occupy all subsites (S1’-S3’, S2, and S3) centering on the zinc containing binding site of MMP-13. We attempted to search for Zn-chelating structures within this SBVS, which could be additionally subjected to the structure-based design of selective MMP-inhibitors targeting different MMP isoforms. Although compounds interacting with the catalytically active Zn-ion lacked selectivity, the identified hits may be a useful resource for the structure-based design of non-Zn-chelating inhibitors targeting individual MMP isozymes.

2. Materials

2.1. Software

Two different programs were used in the SBVS focused on finding new inhibitors for MMP-13. The program Glide from the Schrödinger Small Molecule Drug Discovery Suite (17) was utilized for ligand docking and the program MOE developed by Chemical Computing Group (18) was used for chemical library composition and ligand-based search. We chose these programs due to their availability in our research laboratory and their popularity within the research community reflected by a myriad of cited references. The use of Glide and MOE requires the purchase of their commercial licenses from Schrödinger Inc. and Chemical Computing Group, respectively. Alternatively, other docking programs are freely available such as AutoDock (19), UCSF-DOCK (20), GOLD (21), and SwissDock (22), which have been developed and maintained by academic institutions.

2.2. Database

The virtual chemical library collection was obtained from the ZINC12 database (23,24), which comprises around 10 million commercially available compounds filtered for drug-like physical properties (25): 150 ≤ molecular weight ≤ 500, xlogP ≤ 5, number of rotatable bonds ≤ 7, polar surface area < 150 Å2, number of hydrogen bond donors ≤ 5, and number of hydrogen bond acceptors ≤ 10. The structures were downloaded in an SDF file format and converted to molecular database (mdb) files using the MOE program. The chemical structures were cleaned up to add/remove hydrogen atoms, remove salt and solvent molecules, and generate relevant protonation states at the physiological pH 7.4. The collection of chemical structures was then saved in a MOE database file format for future use.

3. Methods

3.1. Workflow

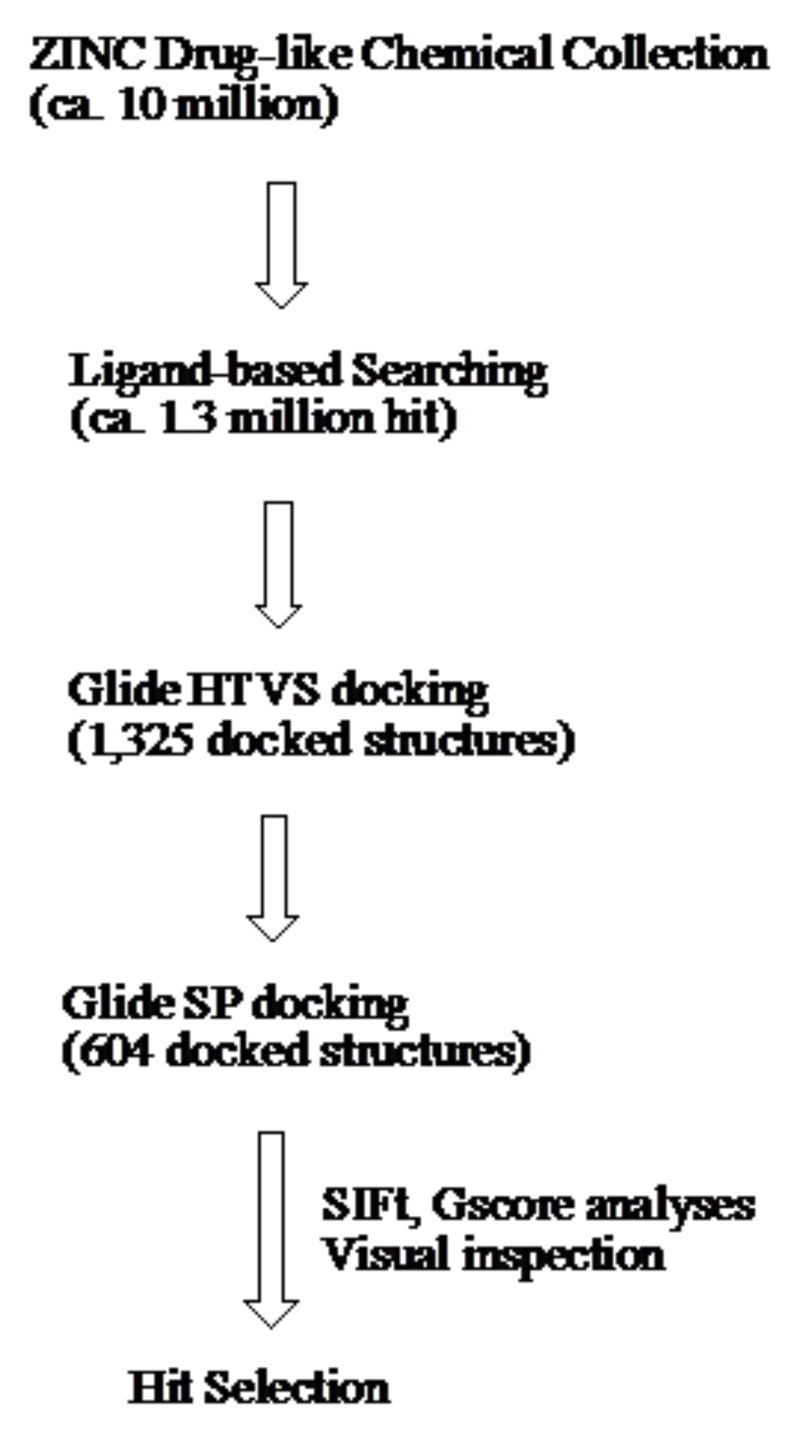

The virtual screening comprised five steps as outlined below (Fig. 3):

Ligand-based search

Analysis of X-ray structures and preparation of a target structure

Grid generation

Glide docking

Data analysis

Figure 3.

Virtual screening process and outcomes

3.2. Ligand-based search

Initially, all chemical structures possessing one or more carboxylic acid functionalities, which can chelate the catalytically active Zn-ion of MMPs, were selected from the MOE database collection generated in Section 2.2. In the Select panel of the MOE database, the keyword, mol=“O=CO” was used to search for chemical structures containing at least one carboxylic acid moiety. This search identified 1,387,623 compounds out of ca. 10 million drug-like small molecules (see Note 1). These structures were assembled and saved as SDF files for structure-based virtual screening.

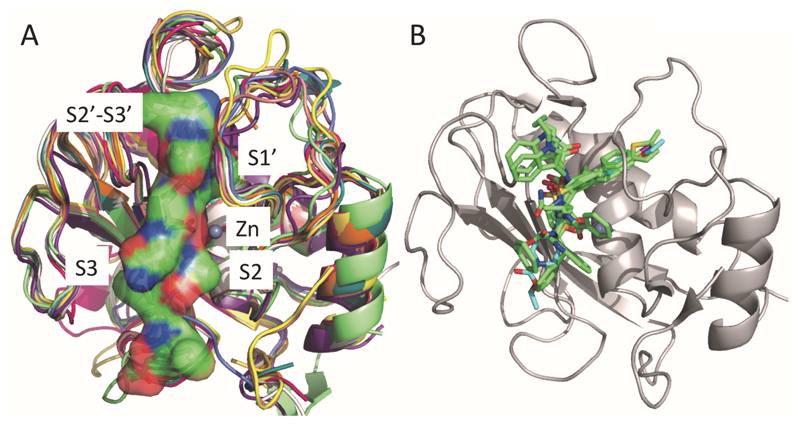

3.3. Analysis of X-ray structures and preparation of the target structure

Structure coordinates were downloaded for all MMP isozymes found in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The sequence alignment for these MMP X-ray crystal structures showed about 50% sequence identity between each isozyme. Superimposition of the MMP structures, based on the sequence alignment, also showed that the catalytic domain of different isozymes is highly conserved, and the binding sites of co-crystallized Zn-chelating inhibitors are located around the metal ion and extended toward all subsites (S1’-S3’, S2, and S3). Furthermore, the chelating moieties of inhibitors that interact with the Zn-ion are located around the metal ion at a distance of approximately 2.1 Å (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Superimposed X-ray co-crystal structures of MMP isozymes (A) and Zn-chelating inhibitors (B). Substrate mimetic (decapeptide) is represented as a surface (PDB ID: 3AYU) (A). Each subsite in the substrate-binding cleft is annotated (A) [29].

The X-ray co-crystal structure of MMP-13 (PDB ID: 3ELM) (26) was used as the target for the SBVS within this study. First, the protein structure was prepared for docking by refining the target protein structure. This step included: assigning bond orders, adding hydrogen atoms, creating zero-order bonds to metals, creating disulfide bonds, filling in missing side chains and loops, and deleting water molecules beyond 5 Å from hetero groups. Chain A of the target protein was used for further refinement which comprised assigning hydrogen bond interactions using the PROPKA module (pH = 7.4). Finally, the structure was subjected for restrained minimization using the OPLS3 force field.

3.4. Receptor grid generation

A receptor grid was generated for the ligand-binding site of the target protein. The grid was set to a 25 Å3 box centered on the Zn-chelating reference ligand of the MMP-13 co-crystal structure (3ELM) and the metal coordination to the zinc ion was assigned as a constraint.

3.5. Glide docking

The Virtual Screening Workflow module was used for Glide docking. The compound collection, containing at least one carboxylic acid moiety from the ligand-based search described in section 3.2, was directly used without further ligand filtering or preparation. Ligand docking was restricted by the comparison of core patterns, which required the carboxylic acid unit of docked ligands to align with that of the reference compound with a tolerance of 0.7 Å. Initially, the ligand structures were sequentially docked into the target grid in the high throughput virtual screening (HTVS) mode, which reduced about 1.3 million carboxylic acid-containing compounds to 1,325 docked structures. This process was followed by Glide standard precision (SP) mode docking of the remaining 1,325 structures, which generated 604 ligands that occupied the zinc-binding site of MMP-13. All 604 docked structures were scored and saved for data analysis and hit triage (see Note 2).

3.6. Data analysis and hit triage

The 604 docked structures occupied the entire area surrounding the Zn-ion. Since the ligand interactions with the subsites S1’-S3’, S2 and S3 are known to improve selectivity within the MMP family, the goal of this virtual screen was to identify diverse sets of Zn-chelating molecules that occupied these regions centered around the Zn-containing active site of MMP-13. Docking post-processing procedures were applied in Maestro to calculate structural interaction fingerprints (SIFt) to analyze intermolecular binding interactions between the protein and the docked structures. After the analysis of the SIFt matrix, a number of structurally diverse compounds, which show interaction with the five subsites, were selected as potential MMP-13 inhibitors. (27,28)

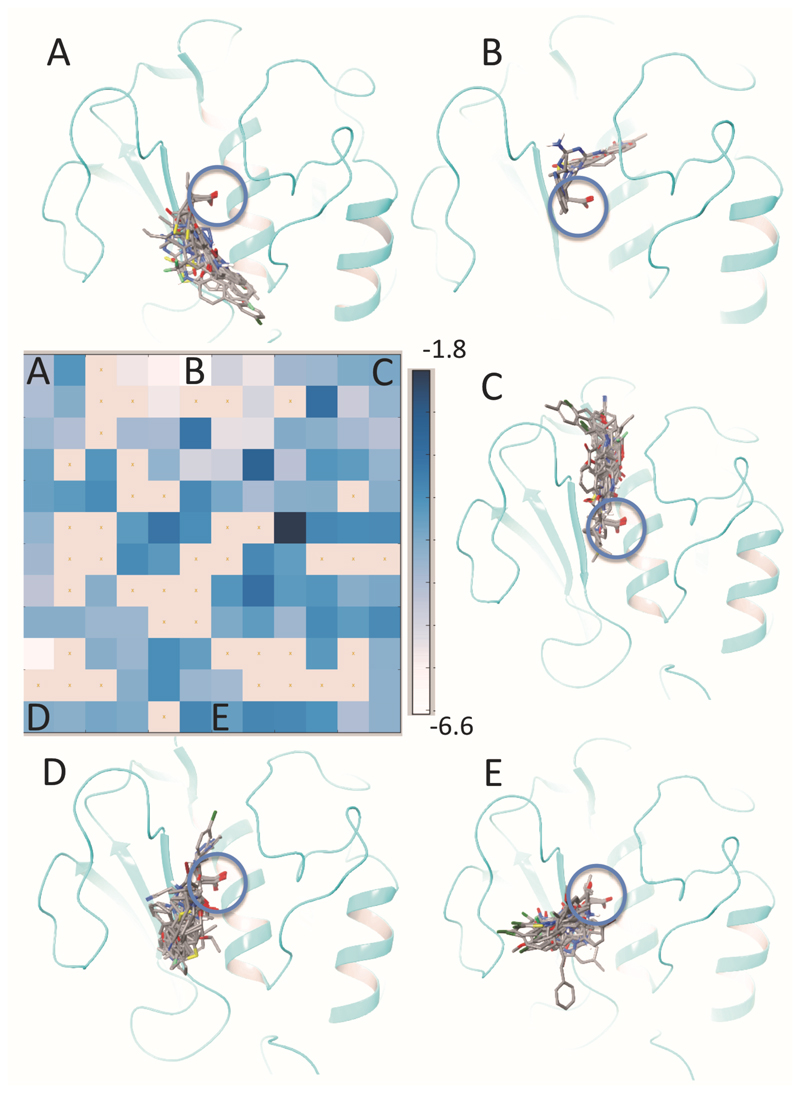

The computed matrix map shows the clustering of SIFts correlated to the docking score of the screened compounds (Fig. 5). Various positions on the map represent ligand occupancy of different binding sites. Ligand binding poses in each cluster of SIFts were visually inspected and potential hits were selected using the following selection criteria: the Glide docking score, the conformational stability of the bound inhibitor, ligand rigidity and uniqueness. Furthermore, compounds were triaged by comparing their binding poses to currently known inhibitors exhibiting interactions considered to be important for potency and selectivity for MMP-13, such as a π-stacking interaction with His222 in the S1’ site, hydrophobic contacts with Tyr176, His187, and Phe189 in the S3 site, and a hydrogen bond interaction with the protein backbone in the S2’ site. (29,26,30,31)

Figure 5.

Structural interaction fingerprints and binding poses of ligands clustered based on their interactions with the target structure. Blue circle represents the Zn-binding site. The color code in the map represents the average of the Glide docking score of different ligands clustered in each cell. It ranges from -6.6 (white, highest score) to -1.8 (dark, lowest score). The top left cell (A) of the map represents ligands occupying the S2 site, the top middle cell (B) represents ligands interacting with the S1’ site, the top right cell (C) represents ligands occupying the S2’ and S3’ sits, the bottom left cell (D) represent ligands binding the area between the subsites S2 and S3, and the middle bottom cell (E) represents the ligands occupying the S3 site.

Finally, 23 ligands were selected as potential Zn-chelating MMP-13 inhibitors (see Note 3). The ZINC ID of the selected ligands were ZINC39475452, ZINC37417840, ZINC82555302, ZINC02860431, ZINC62430943, ZINC41498653, ZINC83306707, ZINC76441060, ZINC71632004, ZINC57989822, ZINC71694581, ZINC82401153, ZINC82867972, ZINC22145620, ZINC00229666, ZINC76186843, ZINC20231914, ZINC71726611, ZINC33510136, ZINC82973537, ZINC82305218, ZINC19476737, and ZINC19438618. The structure and purchasing information for each of these hits can be found at the ZINC database website (www.zinc15.docking.org) using these ID numbers. The new updated version of ZINC15 was released in early 2016.

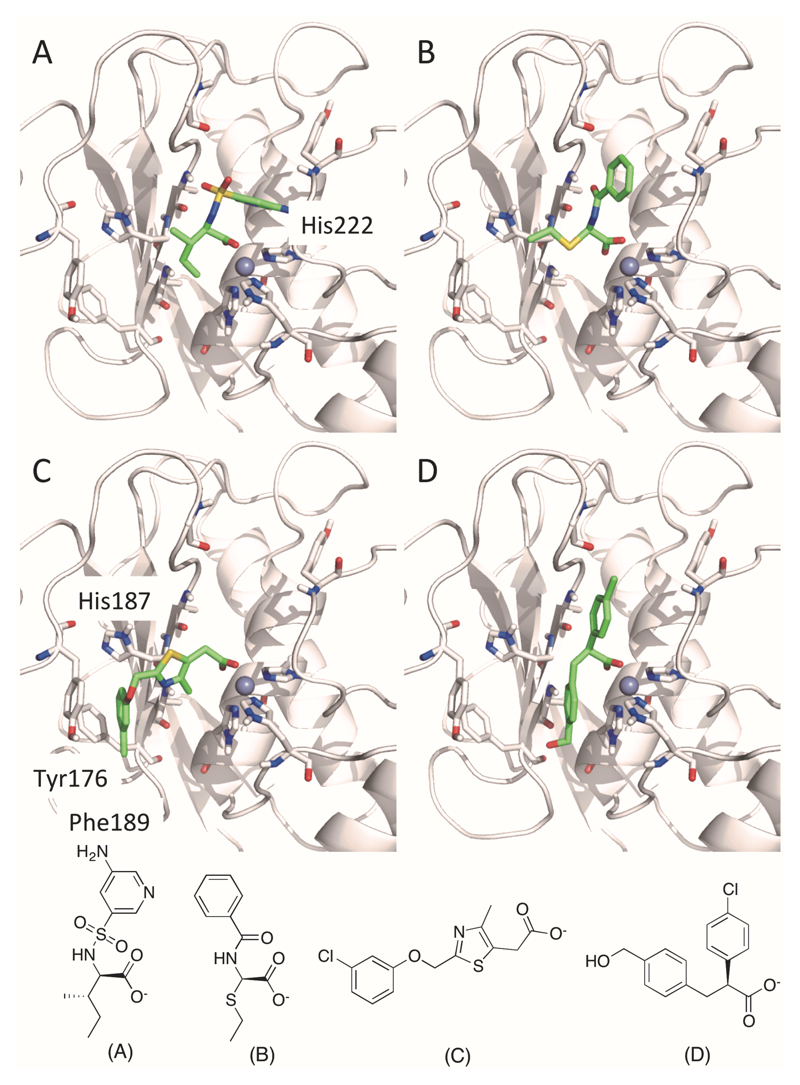

Binding poses of four representative hits are shown in Fig. 6. ZINC62430943 forms a metal-π interaction between the Zn-ion and the pyridine ring and the sulfonamide moiety can form a hydrogen bond interaction with the amide backbone of Leu185 (Fig. 6A). ZINC82305218 interacts with the amide backbone of Leu185 in the substrate binding site via a hydrogen bond and is oriented toward the S2’-S3’ subsite (Fig. 6B). ZINC41498653 forms hydrophobic contacts with Tyr179, His187 and Phe189 in the S3 subsite (Fig. 6C). ZINC57989822 occupies the substrate binding-site near the Zn-ion by forming a hydrogen bond interaction with the amide backbone of Ala188 (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Representative hits and their binding poses in MMP-13. (A) ZINC62430943, (B) ZINC82305218, (C) ZINC41498653, and (D) ZINC57989822 are shown in green sticks. Amino acids in the active site of MMP-13 are shown in gray sticks, and protein structures are shown in a gray ribbon diagram. Figures were generated using the program PyMol.[31]

4. Notes

We assembled a drug-like chemical library of structures obtained from the ZINC database and performed a ligand-based search using MOE. These procedures could also be conducted using LigPrep (32), Canvas (33), and Knime (34) in the Schrödinger program suite. In our study, the analysis of the database to search for potential ligands was faster in MOE compared to using other modules of the Schrödinger program suite.

We identified pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) (35) in the 604 docked ligands obtained from Glide SP, which implies that the ZINC drug-like compound set includes PAINS. Thus, it is necessary to filter for PAINS during the chemical library composition process. Current MOE and Schrödinger programs have additional substructure filters for removal of PAINS.

Coordination to the Zn-ion and the highly conserved catalytic domain of MMP isozymes (Fig. 4A) suggests that most of the identified hits will also inhibit other MMP isoforms. Currently, 199 X-ray structures of MMP isozymes are available in the PDB database: 63 for MMP-12 (macrophase metalloelastase), 43 for MMP-13 (collagenase 3), 31 for MMP-3 (Stromelysin-1), 19 for MMP-9, 18 for MMP-8 (Neutrophil collagenase), 10 for MMP-2 (72 kDa type IV collagenase), 9 for MMP-14, 3 for MMP-7, 1 for MMP-10, 1 for MMP-11, 1 for MMP-16, and a solution structure for MMP-20. Therefore, the hits identified from this virtual screen may form the basis for the structure-based design of inhibitors specifically targeting each MMP isoform.

References

- 1.Cheng T, et al. Structure-Based Virtual Screening for Drug Discovery: A Problem-Centric Review. The AAPS Journal. 2012;14(1):133–141. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9322-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ripphausen P, et al. Quo Vadis, Virtual Screening? A Comprehensive Survey of Prospective Applications. J Med Chem. 2010;53(24):8461–8467. doi: 10.1021/jm101020z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh S, et al. Structure-based virtual screening of chemical libraries for drug discovery. Curr Opin Chem Bio. 2006;10(3):194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takaishi H, et al. Joint diseases and matrix metalloproteinases: A role for MMP-13. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2008;9(1):47–54. doi: 10.2174/138920108783497659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zigrino P, et al. Stromal Expression of MMP-13 is Required for Melanoma Invasion and Metastasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(11):2686–2693. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison C, et al. Microarray and Proteomic Analysis of Breast Cancer Cell and Osteoblast Co-cultures: Role of Osteoblast Matrix Metalloproteinase(MMP)-13 in Bone Metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(39):34271–34285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.222513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandenbroucke RE, Libert C. Is there new hope for therapeutic matrix metalloproteinase inhibition? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(12):904–927. doi: 10.1038/nrd4390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothenberg ML, Nelson AR, Hande KR. New Drugs on the Horizon: Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors. Stem Cells. 1999;17(4):237–240. doi: 10.1002/stem.170237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel CK, et al. Structural Basis for the Highly Selective Inhibition of MMP-13. Chemistry & Biology. 2005;12(2):181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li JJ, Johnson AR. Selective MMP13 inhibitors. Medicinal Research Reviews. 2011;31(6):863–894. doi: 10.1002/med.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dormán G, et al. Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors. Drugs. 2010;70(8):949–964. doi: 10.2165/11318390-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson AR, et al. Discovery and characterization of a novel inhibitor of matrix metalloprotease-13 that reduces cartilage damage in vivo without joint fibroplasia side effects. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(38):27781–27791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li JJ, et al. Quinazolinones and Pyrido[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-ones as Orally Active and Specific Matrix Metalloproteinase-13 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. J Med Chem. 2008;51(4):835–841. doi: 10.1021/jm701274v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai H, et al. Assessment of the renal toxicity of novel anti-inflammatory compounds using cynomolgus monkey and human kidney cells. Toxicology. 2009;258(1):56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gege C, et al. Discovery and Evaluation of a Non-Zn Chelating, Selective Matrix Metalloproteinase 13 (MMP-13) Inhibitor for Potential Intra-articular Treatment of Osteoarthritis. J Med Chem. 2011;55(2):709–716. doi: 10.1021/jm201152u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nara H, et al. Discovery of Novel, Highly Potent, and Selective Quinazoline-2-carboxamide-Based Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 Inhibitors without a Zinc Binding Group Using a Structure-Based Design Approach. J Med Chem. 2014;57(21):8886–8902. doi: 10.1021/jm500981k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friesner RA, et al. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem. 2004;47(7):1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molecular Operating Environment(MOE), 2013.08. Chemical Computing Group Inc.; 1010 Sherbooke St. West, Suite #910, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 2R7: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris GM, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(16):2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen WJ, et al. DOCK 6: Impact of new features and current docking performance. J Comput Chem. 2015;36(15):1132–1156. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones G, et al. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J Mol Biol. 1997;267(3):727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grosdidier A, Zoete V, Michielin O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39(Web Server issue):W270–277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irwin JJ, et al. ZINC: a free tool to discover chemistry for biology. J Chem Inf Model. 2012;52(7):1757–1768. doi: 10.1021/ci3001277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK. ZINC - A free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. J Chem Inf Model. 2005;45(1):177–182. doi: 10.1021/ci049714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipinski CA. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2000;44(1):235–249. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(00)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monovich LG, et al. Discovery of potent, selective, and orally active carboxylic acid based inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase-13. J Med Chem. 2009;52(11):3523–3538. doi: 10.1021/jm801394m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh J, et al. Structural interaction fingerprints: A new approach to organizing, mining, analyzing, and designing protein-small molecule complexes. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006;67(1):5–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2005.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng Z, Chuaqui C, Singh J. Structural interaction fingerprint (SIFt): A novel method for analyzing three-dimensional protein-ligand binding interactions. J Med Chem. 2004;47(2):337–344. doi: 10.1021/jm030331x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto H, et al. Structural basis for matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2)-selective inhibitory action of beta-amyloid precursor protein-derived inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(38):33236–33243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.264176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gall AL, et al. Crystal structure of the stromelysin-3 (MMP-11) catalytic domain complexed with a phosphinic inhibitor mimicking the transition-state. J Mol Biol. 2001;307(2):577–586. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Browner MF, Smith WW, Castelhano AL. Matrilysin-inhibitor complexes: Common themes among metalloproteases. Biochemistry. 1995;34(20):6602–6610. doi: 10.1021/bi00020a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrödinger Release 2016-2: LigPrep, version 3.8. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sastry M, et al. Large-scale systematic analysis of 2D fingerprint methods and parameters to improve virtual screening enrichments. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50(5):771–784. doi: 10.1021/ci100062n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berthold MR, et al. Studies in Classification, Data Analysis, and Knowledge Organization. Springer; 2007. Knime: The Konstanz Information Miner. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baell J, Walters MA. Chemistry: Chemical con artists foil drug discovery. Nature. 2014;513(7519):481–483. doi: 10.1038/513481a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]