Overview

Introduction

Percutaneous needle fasciotomy (PNF) is a safe, simple, and inexpensive method for treating mild to moderate Dupuytren contractures with a palpable cord and an extension deficit in the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints.

Indications & Contraindications

Step 1: The Setup

For most patients, perform PNF in a regular outpatient office after local disinfection of the skin.

Step 2: Choice of Cord Level for PNF and Anesthesia

Choose the puncture site at the thinnest part of the cord and avoid skin creases to minimize the risk of skin ruptures (Fig. 2).

Step 3: Perforating the Cord

Ensure that the finger to be treated is firmly extended throughout the procedure so that the cord is tensioned.

Step 4: Rupture of the Cord and Extension of the Joint

The effectiveness of PNF is usually obvious when the cord ruptures.

Step 5: Post-Treatment Instructions

There is usually no need for regular hand therapy, and routine follow-up visits after PNF are rarely indicated for a patient with appropriate instructions to return in case of any complications.

Results

The results of PNF have shown an excellent rate of reduction of the contracture, and a majority (79%) of the patients retained a straight joint after 2 years11.

Pitfalls & Challenges

Abstract

Background:

Percutaneous needle fasciotomy (PNF) is a minimally invasive treatment option for mild to moderate Dupuytren contractures in the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, and the procedure requires limited resources. Multiple contractures can be treated during the same session, and the treatment is considerably easier for the patient and requires a minimum of rehabilitation compared with limited fasciectomy1.

Description:

PNF can be performed in a regular outpatient clinic in most cases. With the patient in a reclined position, the cord of the contracted joint is tensioned by passive extension and is divided percutaneously with a 25-gauge needle under local anesthesia. The immediate treatment effect in terms of reduction of the contracture is readily assessed, and PNF can be performed at additional levels if needed.

Alternatives:

Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum (CCH; Xiaflex).

Total or partial fasciectomy.

Dermofasciectomy.

Amputation (in severe cases after multiple other procedures).

Rationale:

Local treatment with injection of CCH (Xiaflex) in the Dupuytren cord enables rupture of the cord similar to that after PNF2. Both CCH and PNF are minimally invasive treatments with obvious advantages compared with open surgery3, and they seem to have the same intermediate-term outcome4-6. However, CCH treatment is considerably more expensive than PNF and requires 2 visits by the patient to the outpatient clinic instead of 17. CCH has also been reported to have more complications than PNF2,8. Furthermore, multiple (>4) joint contractures9 can be treated by PNF at the same time. In the author’s experience, even bilateral contractures can be treated at the same session if requested by the patient. As the number of patients treated with CCH and PNF has increased, there has been a corresponding decrease in more invasive procedures10; however, open surgery will probably always remain an option in more severe cases or as a secondary procedure after recurrence.

Introductory Statement

Percutaneous needle fasciotomy (PNF) is a safe, simple, and inexpensive method for treating mild to moderate Dupuytren contractures with a palpable cord and an extension deficit in the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints.

Indications & Contraindications

Indications

A palpable Dupuytren cord with a concomitant extension deficit in a patient who actively seeks treatment for the condition.

A passive extension deficit of ≥20° in the MCP joint and/or a passive extension deficit of ≥30° in the PIP joint (universal indications for any treatment of Dupuytren contracture are absent in the literature, but collagenase Clostridium histolyticum [CCH] treatment has been used for contractures of ≥20°).

Anticoagulant therapy and recurrent contracture are not contraindications to PNF.

Contraindications

Secondary joint changes in the PIP joint, e.g., capsular shrinkage, indicating the need for more invasive treatment.

Local symptoms from diseased subcutaneous tissue, e.g., painful nodules within a cord, in a patient who is suitable for more invasive treatment.

Lack of patient compliance.

Step-by-Step Description of Procedure

PNF at the MCP Joint

Dupuytren cords at the MCP joint are generally easier to treat, with less risk of damage to the adjacent nerves and tendons, than those in the PIP joint. The surgeon is advised to gain experience of the method at the MCP joint level prior to starting with the PIP joint, and to ensure that the modified technique for the PIP joint described in the next section is used.

Step 1: The Setup

For most patients, perform PNF in a regular outpatient office after local disinfection of the skin.

Place the patient in a reclining position, with the affected hand positioned on a separate table.

Perform local disinfection of the skin.

The surgeon should be positioned so that the nondominant hand keeps the affected finger extended throughout the procedure (Fig. 1).

Using a 3-mL syringe, mix 1 mL of methylprednisolone (or equivalent corticosteroid) with 2 mL of 2% mepivacaine (or equivalent).

Fit a 25-gauge needle (preferably one that is 1 in [2.54 cm] long since it will provide better directional and depth control) to the syringe.

Fig. 1.

An intraoperative photograph showing the setup for PNF. The patient’s hand is resting on a separate table, the skin over the cord has been disinfected, and the finger to be treated is firmly extended by the surgeon’s nondominant hand.

Step 2: Choice of Cord Level for PNF and Anesthesia

Choose the puncture site at the thinnest part of the cord and avoid skin creases to minimize the risk of skin ruptures (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The puncture site should avoid skin creases to decrease the risk of skin ruptures (even though they are not to be feared).

Choose the puncture site at the thinnest part of the cord and avoid skin creases.

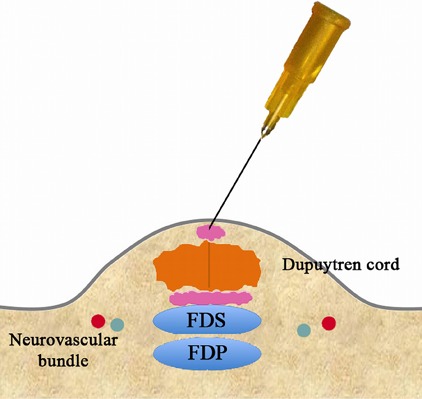

Inject a small volume subcutaneously volar to the cord, retract the needle, and wait for the local anesthetic to take effect (Figs. 3-A and 3-B).

Pass the needle through the cord at the same puncture site while tensioning the cord by passively extending the finger. Note the loss of resistance when the needle passes through the cord dorsally. Inject a slightly larger volume (Fig. 3-C), retract the needle (Fig. 3-D), and wait for the local anesthetic to take effect (Fig. 3-E).

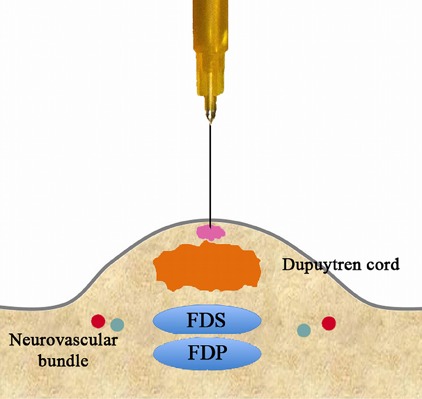

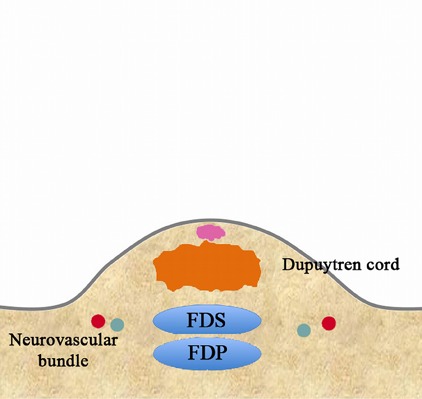

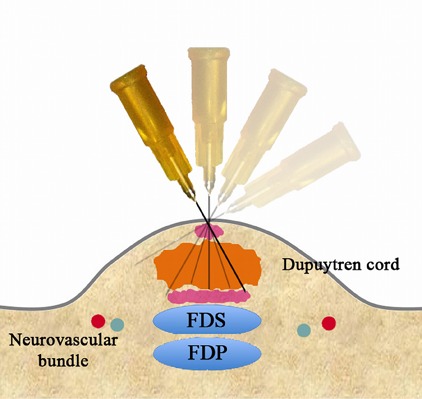

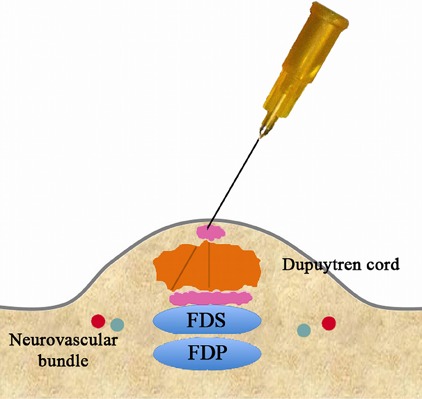

Figs. 3-A through 3-I Schematic and detailed sequential illustration of PNF. FDS = flexor digitorum superficialis, and FDP = flexor digitorum profundus. Figs. 3-A and 3-B Administration of anesthesia.

Fig. 3-A.

Inject a small volume subcutaneously volar to the cord.

Fig. 3-B.

Retract the needle and wait for the local anesthetic to take effect.

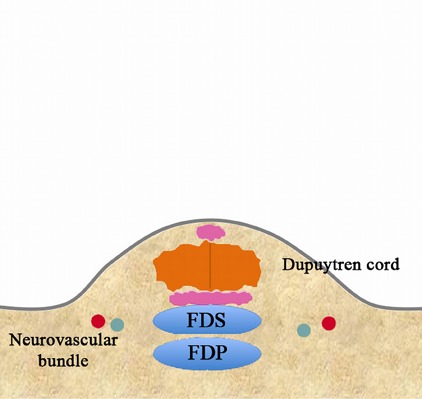

Figs. 3-C, 3-D, and 3-E Repeat administration of anesthesia.

Fig. 3-C.

Inject a slightly larger volume.

Fig. 3-D.

Retract the needle.

Fig. 3-E.

Wait for the local anesthetic to take effect.

Step 3: Perforating the Cord

Ensure that the finger to be treated is firmly extended throughout the procedure so that the cord is tensioned.

Make sure that the involved finger is firmly extended so that the cord is tensioned. This increases the resistance to the needle in the cord and enhances the loss of resistance as the needle passes through the cord, thus preventing damage to the flexor tendons. Using the same puncture site in the skin, angle the needle in a different direction (Video 1, Fig. 3-F).

Pass the needle through the cord (Fig. 3-G). An obvious loss of resistance should be felt when the needle passes dorsally. If this loss of resistance is difficult to detect, increase the tension of the cord by applying more force to extend the finger passively.

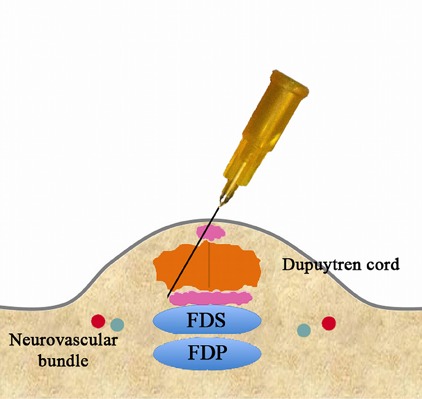

Retract the needle to the level of the skin (Fig. 3-H), angle the needle in yet another direction, and perforate the cord again (Fig. 3-I).

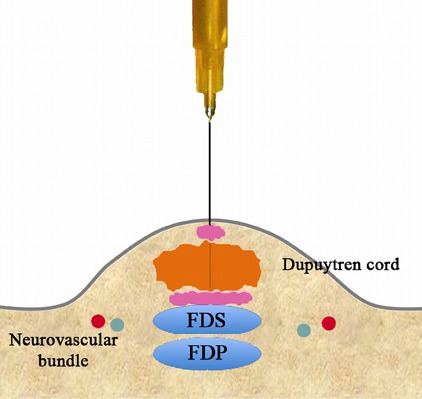

Fig. 3-I.

Angle the needle in yet another direction and perforate the cord again.

Video 1.

Percutaneous needle fasciotomy. To provide the view for the surgeon, the finger is extended by an assistant surgeon. Normally, the finger to be treated is extended by the nondominant hand of the surgeon while the dominant hand works the syringe and needle.

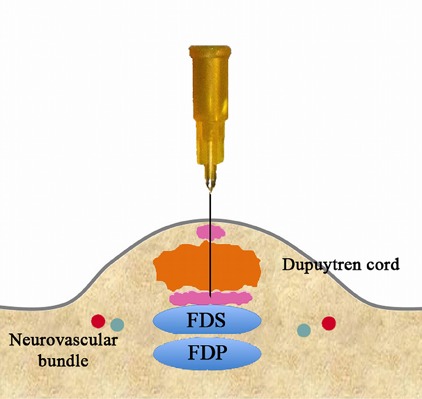

Figs. 3-F, 3-G, and 3-H Perforation of the cord.

Fig. 3-F.

Using the same puncture site in the skin, angle the needle in a different direction.

Fig. 3-G.

Pass the needle through the cord.

Fig. 3-H.

Retract the needle to the level of the skin.

Step 4: Rupture of the Cord and Extension of the Joint

The effectiveness of PNF is usually obvious when the cord ruptures.

Keep perforating the cord in different directions in a fan-shaped pattern in a transverse plane until the cord ruptures. This rupture is either felt or heard as the joint starts to straighten.

Remove the needle, place a sterile dressing over the puncture site, and extend the finger firmly to a hyperextension of at least 10°. Show the resulting full passive extension to the patient and place a bandage on the puncture site.

Step 5: Post-Treatment Instructions

There is usually no need for regular hand therapy, and routine follow-up visits after PNF are rarely indicated for a patient with appropriate instructions to return in case of any complications.

Regular therapy and routine follow-up visits are not usually necessary.

Consider the use of a night splint if there is an obvious discrepancy between the active and passive extension of the MCP joint. Secondary joint contractures can usually be overcome (Fig. 4). The splint should be volar with straight fingers and should be used for a maximum of 3 months or until the joint is completely straightened. This is usually not needed for simple MCP contractures.

Instruct the patient to stretch any residual extension deficit by using the other hand. Encourage the patient to use the hand immediately and to integrate daily stretching during his or her spare time, e.g., while riding a bus or watching television, for at least 2 months.

Inform the patient about the risk of recurrence and ensure that the patient knows how to renew contact if this should occur.

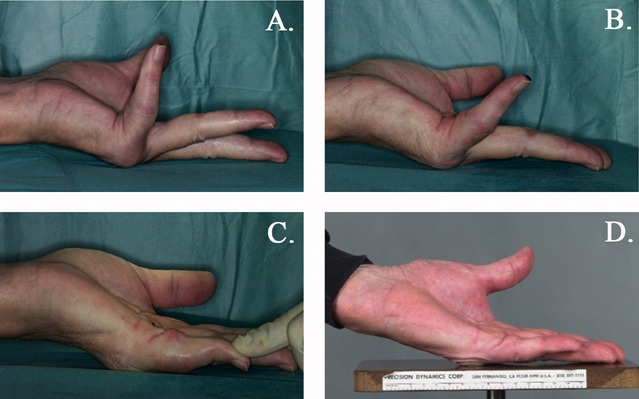

Fig. 4.

Figs. 4-A through 4-D An illustration of a joint contraction secondary to a Dupuytren contracture, and its correction over time. Fig. 4-A The maximum active extension in a patient with a severe MCP contracture before PNF. Fig. 4-B The maximum active extension immediately after PNF. Fig. 4-C The maximum passive extension at the same time. Fig. 4-D To overcome these secondary changes to the joint, the patient was provided with a night splint for 3 months. The photograph shows the active extension 1 year after PNF.

PNF at the PIP Joint

The risk of injury to the neurovascular bundle and the flexor tendons increases at the PIP level. As in all other Dupuytren contracture treatments, the PIP joint is considerably more difficult to treat, and other procedures such as limited fasciectomy should be considered when the cord is thick and/or secondary joint changes are anticipated. PNF could, however, be a reasonable option in the presence of a thin, superficial cord. In contrast to the central peritendinous cord at the MCP joint level, cords that engage the PIP joints are usually located in an ulnar or radial position to the cord, i.e., close to the neurovascular bundle. The following modification to the method described above is therefore recommended.

Carefully instruct the patient to report any paresthesia in the finger during the procedure, especially when the needle is inserted in different directions to divide the cord.

Use only a minimal volume of local anesthetic subcutaneously between the intended puncture site and the cord; anesthesia of the digital nerve should be avoided. If repeated needling is required, test sensitivity to touch in the fingertip occasionally to ensure intact nerve function and abort the procedure if the patient reports a digital nerve block.

Perform PNF as described above. Tension the cord maximally and change direction when the needle has passed through the cord. If possible, choose a dorsolateral angle away from the neurovascular bundle and flexor tendons.

When the cord starts to rupture, inject a larger volume of local anesthetic and retract the needle. Wait until satisfactory local anesthesia takes effect and perform the extension maneuver. Do not continue to insert the needle.

A volar night splint with straight fingers for 3 months is usually required for PIP contractures.

Results

The results of PNF have shown an excellent rate of reduction of the contracture, and a majority (79%) of the patients retained a straight joint after 2 years11. Dupuytren contracture is, however, notorious for recurrence, regardless of treatment method. One study on 1,013 fingers treated with PNF and followed for a median of 3 years showed a recurrence rate of 48%12. Another randomized controlled trial between PNF and limited fasciectomy indicated a recurrence rate of 21.8% in the PNF group compared with 5.3% in the limited fasciectomy group using standard definitions of recurrence13, and even higher recurrence rates have been reported14. However, PNF is a simple procedure that can be performed repeatedly, and 53% of the patients with recurrence in the latter study chose another PNF procedure.

Patient-reported outcome measures have shown a significant improvement in a disease-specific questionnaire, the Unité Rhumatologique des Affections de la Main (URAM), in a general upper extremity questionnaire (Quick-DASH [an abbreviated version of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire]), and with visual analog scales, indicating that most patients are very satisfied with the method4,6,11.

Older patients (>55 years) seem to have a better outcome in terms of a lower rate of recurrence compared with younger patients13.

Pitfalls & Challenges

Skin ruptures (Fig. 5) are common (5% to 38%)6,15 and should not be feared. If a skin rupture occurs, show it to the patient and reassure him or her that this is a well-known complication that will heal by secondary intention within approximately 2 weeks. Do not attempt any other closure of the skin, regardless of the size of the rupture. Apply a compressive dressing and instruct the patient to remove it the next day and to wash the skin rupture with soap and water before applying a simple bandage and continue to do so until healing. If there are doubts about compliance with these recommendations, ensure that the patient is scheduled to have the wound checked in approximately 2 days.

Nerve injuries are rare complications (<0.5%)8,16 that occur almost exclusively at the PIP joint level. Use a minimal amount of local anesthetic in the PIP joint and instruct the patient to report any paresthesia so that the risk of damage to the digital nerves is reduced.

Tendon injuries have been reported but at a very low rate (<0.05%)8.

Fig. 5.

An example of skin ruptures after PNF. These wounds healed uneventfully within 2 weeks.

Footnotes

Published outcomes of this procedure can be found at: J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018 Jul 5;100(13):1079-86.

Disclosure: The author indicated that no external funding was received for any aspect of this work. The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest form is provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSEST/A238).

References

- 1.van Rijssen AL, Gerbrandy FS, Ter Linden H, Klip H, Werker PM. A comparison of the direct outcomes of percutaneous needle fasciotomy and limited fasciectomy for Dupuytren’s disease: a 6-week follow-up study. J Hand Surg Am. 2006. May-Jun;31(5):717-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strömberg J, Vanek P, Fridén J, Aurell Y. Ultrasonographic examination of the ruptured cord after collagenase treatment or needle fasciotomy for Dupuytren’s contracture. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2017. September;42(7):683-8. Epub 2017 Jun 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peimer CA, Blazar P, Coleman S, Kaplan FT, Smith T, Lindau T. Dupuytren contracture recurrence following treatment with collagenase Clostridium histolyticum (CORDLESS [Collagenase Option for Reduction of Dupuytren Long-Term Evaluation of Safety Study]): 5-year data. J Hand Surg Am. 2015. August;40(8):1597-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scherman P, Jenmalm P, Dahlin LB. One-year results of needle fasciotomy and collagenase injection in treatment of Dupuytren’s contracture: a two-centre prospective randomized clinical trial. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2016. July;41(6):577-82. Epub 2015 Dec 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skov ST, Bisgaard T, Søndergaard P, Lange J. Injectable collagenase versus percutaneous needle fasciotomy for Dupuytren contracture in proximal interphalangeal joints: a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2017. May;42(5):321-8.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strömberg J, Ibsen-Sörensen A, Fridén J. Comparison of treatment outcome after collagenase and needle fasciotomy for Dupuytren contracture: a randomized, single-blinded, clinical trial with a 1-year follow-up. J Hand Surg Am. 2016. September;41(9):873-80. Epub 2016 Jul 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen NC, Shauver MJ, Chung KC. Cost-effectiveness of open partial fasciectomy, needle aponeurotomy, and collagenase injection for Dupuytren contracture. J Hand Surg Am. 2011. November;36(11):1826-34.e32. Epub 2011 Oct 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krefter C, Marks M, Hensler S, Herren DB, Calcagni M. Complications after treating Dupuytren’s disease. A systematic literature review. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2017. October;36(5):322-9. Epub 2017 Sep 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaudreuil J, Lermusiaux JL, Teyssedou JP, Lahalle S, Lasbleiz S, Bernabé B, Lellouche H, Orcel P, Bardin T. Multi-needle aponeurotomy for advanced Dupuytren’s disease: preliminary results of safety and efficacy (MNA 1 study). Joint Bone Spine. 2011. December;78(6):625-8. Epub 2011 Feb 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao JZ, Hadley S, Floyd E, Earp BE, Blazar PE. The impact of collagenase Clostridium histolyticum introduction on Dupuytren treatment patterns in the United States. J Hand Surg Am. 2016. October;41(10):963-8. Epub 2016 Aug 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strömberg J, Ibsen Sörensen A, Fridén J. Percutaneous needle fasciotomy versus collagenase treatment for Dupuytren contracture: a randomized controlled trial with a two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018. July 5;100(13):1079-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pess GM, Pess RM, Pess RA. Results of needle aponeurotomy for Dupuytren contracture in over 1,000 fingers. J Hand Surg Am. 2012. April;37(4):651-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Rijssen AL, ter Linden H, Werker PM. Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial on treatment in Dupuytren’s disease: percutaneous needle fasciotomy versus limited fasciectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012. February;129(2):469-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foucher G, Medina J, Navarro R. Percutaneous needle aponeurotomy: complications and results. J Hand Surg Br. 2003. October;28(5):427-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lermusiaux JL, Lellouche H, Badois JF, Kuntz D. How should Dupuytren’s contracture be managed in 1997? Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1997. December;64(12):775-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rijssen AL, Werker PM. Percutaneous needle fasciotomy in Dupuytren’s disease. J Hand Surg Br. 2006. October;31(5):498-501. Epub 2006 Jun 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]