Abstract

Background

Migraine is a common, disabling condition and a burden for the individual, health services, and society. Zolmitriptan is an abortive medication for migraine attacks, belonging to the triptan family. These medicines work in a different way to analgesics such as paracetamol and ibuprofen.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and tolerability of zolmitriptan compared to placebo and other active interventions in the treatment of acute migraine attacks in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Oxford Pain Relief Database, together with three online databases (www.astrazenecaclinicaltrials.com, www.clinicaltrials.gov, and apps.who.int/trialsearch) for studies to 12 March 2014. We also searched the reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews.

Selection criteria

We included randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐ or active‐controlled studies, with at least 10 participants per treatment arm, using zolmitriptan to treat a migraine headache episode.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. We used numbers of participants achieving each outcome to calculate risk ratios and numbers needed to treat for an additional beneficial effect (NNT) or harmful effect (NNH) compared with placebo or a different active treatment.

Main results

Twenty‐five studies (20,162 participants) compared zolmitriptan with placebo or an active comparator. The evidence from placebo‐controlled studies was of high quality for all outcomes except 24 hour outcomes and serious adverse events where only limited data were available. The majority of included studies were at a low risk of performance, detection and attrition biases, but did not adequately describe methods of randomisation and concealment.

Most of the data were for the 2.5 mg and 5 mg doses compared with placebo, for treatment of moderate to severe pain. For all efficacy outcomes, zolmitriptan surpassed placebo. For oral zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo, the NNTs were 5.0, 3.2, 7.7, and 4.1 for pain‐free at two hours, headache relief at two hours, sustained pain‐free during the 24 hours postdose, and sustained headache relief during the 24 hours postdose, respectively. Results for the oral 5 mg dose were similar to the 2.5 mg dose, while zolmitriptan 10 mg was significantly more effective than 5 mg for pain‐free and headache relief at two hours. For headache relief at one and two hours and sustained headache relief during the 24 hours postdose, but not pain‐free at two hours, zolmitriptan 5 mg nasal spray was significantly more effective than the 5 mg oral tablet.

For the most part, adverse events were transient and mild and were more common with zolmitriptan than placebo, with a clear dose response relationship (1 mg to 10 mg).

High quality evidence from two studies showed that oral zolmitriptan 2.5 mg and 5 mg provided headache relief at two hours to the same proportion of people as oral sumatriptan 50 mg (66%, 67%, and 68% respectively), although not necessarily the same individuals. There was no significant difference in numbers experiencing adverse events. Single studies reported on other active treatment comparisons but are not described further because of the small amount of data.

Authors' conclusions

Zolmitriptan is effective as an abortive treatment for migraine attacks for some people, but is associated with increased adverse events compared to placebo. Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg and 5 mg benefited the same proportion of people as sumatriptan 50 mg, although not necessarily the same individuals, for headache relief at two hours.

Plain language summary

Zolmitriptan for acute migraine attacks in adults

Migraine is a complex condition with a wide variety of symptoms. It affects about 1 person in 8, mainly women aged 30 to 50 years. For many people, the main feature is a painful, and often disabling, headache. Other symptoms include feeling sick, vomiting, disturbed vision, and sensitivity to light, sound, and smells.

Zolmitriptan is one of the triptan family of drugs. It is used to treat migraine attacks when they occur, not to prevent attacks occurring. It is available as an oral tablet to swallow whole, an oral tablet to dissolve in the mouth, and a nasal spray. This review looked at 25 studies that involved over 20,000 participants reporting the effects of zolmitriptan on migraine attacks. Most information was for tablets taken by mouth. Overall methodological quality of the included studies was good, and treatment group sizes were large enough to avoid major bias. There were inconsistencies in the way use of rescue medication and adverse events were reported.

A single oral dose of zolmitriptan relieved migraine headache pain in some people. Several different pain outcomes were reported.

One outcome was pain reduced from moderate or severe to no pain at all two hours after taking treatment. An oral zolmitriptan 2.5 mg tablet delivered this outcome to about 3 in 10 people (30%), compared with about 1 in 10 (10%) taking placebo.

Another outcome was pain reduced from moderate or severe to no worse than mild pain two hours after taking treatment (called headache relief). An oral zolmitriptan 2.5 mg tablet delivered this outcome to about 6 in 10 people (61%), compared with 3 in 10 (29%) taking placebo.

Slightly better results were obtained with higher doses of 5 mg or 10 mg oral tablets, but the 10 mg dose was associated with more adverse events, most of which were of short duration and mild or moderate in severity. Results for the 5 mg nasal spray were generally similar to those for the oral tablet, but it was significantly better than the tablet at 1 hour.

People with migraine want treatment that eliminates the headache and any associated symptoms quickly (maximum two hours) and prevents it returning (within 24 hours). Results indicate that with the 5 mg dose only 14% of those treated were pain‐free at 2 hours with no headache recurrence within 24 hours.

Oral zolmitriptan 2.5 mg and 5 mg provided headache relief at two hours to the same proportion of people (2 in 3) as oral sumatriptan 50 mg, with no difference in numbers experiencing adverse events. The individuals who respond to each drug may not be the same.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Oral zolmitriptan 2.5 mg compared with placebo for migraine headache | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with migraine headache ‐ moderate or severe pain Settings: community Intervention: oral zolmitriptan 2.5 mg Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Probable outcome with comparator | Probable outcome with intervention | NNT or NNTH and/or relative effect (95% CI) | No of studies, attacks, events | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Pain‐free response at 2 h | 100 in 1000 | 300 in 1000 | NNT 5.0 (4.5 to 5.6) | 11 studies, 5223 attacks, 1157 events | High | Lower NNTs are better than higher NNTs |

| Headache relief at 2 h | 290 in 1000 | 610 in 1000 | NNT 3.2 (3.0 to 3.5) | 11 studies, 4567 attacks, 2184 events | High | Lower NNTs are better than higher NNTs |

| Headache relief at 1 h | 210 in 1000 | 380 in 1000 | NNT 6.0 (5.2 to 7.2) | 9 studies, 4123 attacks, 1273 events | High | Lower NNTs are better than higher NNTs |

| Sustained pain‐free during the 24 h post dose | 60 in 1000 | 190 in 1000 | NNT 7.7 (5.9 to 11) | 2 studies, 984 attacks, 145 events | Moderate | Lower NNTs are better than higher NNTs Downgraded due to small number of studies and events |

| Sustained headache relief during the 24 h post dose | 140 in 1000 | 380 in 1000 | NNT 4.1 (3.5 to 5.0) | 4 studies, 1457 attacks, 451 events | High | Lower NNTs are better than higher NNTs |

| At least one AE | 170 in 1000 | 310 in 1000 | NNH 7.0 (6.1 to 8.2) | 12 studies, 5717 attacks, 1464 events | High | Higher NNHs are better than lower NNTs |

| Serious AE* | 2.0 in 1000 | 3.3 in 1000 | insufficient data to calculate | 10,561 attacks, 30 events | Moderate | *all doses > 1 mg and all formulations combined Downgraded due to small number of events |

|

AE: adverse event;CI: Confidence interval; NNT: number needed to treat; NNH: number needed to harm Note: NNT or NNH is reported when an outcome is statistically different from placebo or comparator. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

Description of the condition

Migraine is a common, disabling headache disorder, ranked seventh highest among specific causes of disability globally (Steiner 2013), and with considerable social and economic impact (Hazard 2009). Recent reviews found a one‐year prevalence of 15% globally (Vos 2012) and for adults in European countries (Stovner 2010), 13% for all ages in the USA (Victor 2010), 21% in Russia (Ayzenberg 2012), and 9% for adults in China (Yu 2012). Migraine is more prevalent in women than in men (by a factor of two to three), and in the age range 30 to 50 years.

The International Headache Society (IHS) classifies two major subtypes (IHS 2013). Migraine without aura is the most common subtype. It is characterised by attacks lasting 4 to 72 hours that are typically of moderate to severe pain intensity, unilateral, pulsating, aggravated by normal physical activity, and associated with nausea with or without photophobia and phonophobia. Migraine with aura is characterised by reversible focal neurological symptoms that develop over a period of at least 5 minutes and last for less than 60 minutes, followed by headache with the features of migraine without aura. In some cases, the headache may lack migrainous features or be absent altogether (IHS 2013).

A large prevalence study in the USA found that over half of migraineurs had severe impairment or required bed rest during attacks. Despite this high level of disability and a strong desire for successful treatment, only a proportion of people with migraine seek professional advice for the treatment of attacks. The majority were not taking any preventive medication, although one‐third met guideline criteria for being offered or considering it. Nearly all (98%) migraineurs used acute treatments for attacks, with 49% using over‐the‐counter (OTC) medication only, 20% using prescription medication, and 29% using both. OTC medications included aspirin, other non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), paracetamol (acetaminophen), and paracetamol plus caffeine (Bigal 2008; Diamond 2007; Lipton 2007). Similar findings have been reported from other large studies in France and Germany (Lucas 2006; Radtke 2009).

The significant impact of migraine with regard to pain, functional health, and well‐being is well documented (Buse 2011; Leonardi 2005); it is ranked in the top 10 disorders for global years lived with disability (Vos 2012). A cross‐sectional survey of eight European Union (EU) countries (representing 55% of the adult population) has estimated an annual direct and indirect cost of migraine per person of EUR 1222, and a total annual cost for the EU of EUR 111 billion for adults aged 18 to 65 years (Linde 2012). Costs vary between countries, probably due to differences in available therapies and the way they are delivered and structural differences in healthcare systems (Bloudek 2012). In the USA, the mean annual direct cost per person has been estimated at USD 1757 for episodic migraine and USD 7750 for chronic migraine (Munakata 2009). Whatever the exact direct and indirect costs are for each country, it is clear that they are substantial. Successful treatment of acute migraine attacks not only benefits patients by reducing their disability and improving health‐related quality of life, but also has the potential to reduce the need for healthcare resources and increase economic productivity.

Description of the intervention

The symptomatic treatment of migraine advanced significantly with the development of the triptan class of drugs, of which sumatriptan was the first, in 1991. Zolmitriptan (trade names include Zomig, Zomigon, Zomigoro, AscoTop) is a second‐generation triptan, available as a standard tablet to be swallowed whole (2.5 mg), an oral disintegrating tablet (also called a 'melt'; 2.5 mg and 5 mg), and a nasal spray (5 mg). The disintegrating tablet contains aspartame, which can cause headache in some individuals and should be avoided by them. It dissolves rapidly in the mouth and can be swallowed without the need for fluid intake. It confers convenience, and may also provide faster onset of action if it dissolves sufficiently quickly to allow substantial uptake through the buccal mucosa. The nasal spray provides a route of administration that avoids oral ingestion altogether, which may be preferable for those who experience nausea and vomiting with migraine attacks. It also partly avoids the problem of slow absorption due to gastric stasis, which is commonly experienced. Up to 30% of the absorbed drug is taken up across the nasal mucosa, mostly immediately after dosing, and this may also lead to a faster onset of action.

The 'recommended' dose in the United Kingdom (UK) is 2.5 mg, with an optional second 2.5 mg dose for recurrence, and subsequent 5 mg for the next attack if 2.5 mg provides inadequate relief (BNF 2013). The maximum dose is 10 mg in 24 hours. In England in 2011 there were 300,000 prescriptions for zolmitriptan in primary care, almost two‐thirds of which were for the standard 2.5 mg tablet (PCA 2012). In the USA recommended doses are lower (1.25 or 2.5 mg) but as in the UK, the maximum dose in 24 hours is 10 mg.

In order to establish whether zolmitriptan is an effective treatment for migraine at a specified dose in acute migraine attacks, it is necessary to study its effects in circumstances that permit detection of pain relief. Such studies are carried out in individuals with established pain of moderate to severe intensity, using single doses of the interventions. Participants who experience an inadequate response with either placebo or active treatment are permitted to use rescue medication, and the intervention is considered to have failed in those individuals. In clinical practice, however, individuals would not normally wait until pain is of at least moderate severity, and may take a second dose of medication if the first dose does not provide adequate relief. Once efficacy is established in studies using single doses in established pain, further studies may investigate different treatment strategies and patient preferences. These are likely to include treating the migraine attack early while pain is mild, and using a low dose initially, with a second dose if the response is inadequate.

How the intervention might work

Zolmitriptan is a 5‐hydroxytryptamine 1 (5‐HT1) agonist, mainly targeting the 5‐HT (serotonin) 1B and 1D receptors. It has three putative mechanisms of therapeutic action (Ferrari 2002; Goadsby 2007a):

vasoconstriction of dilated meningeal blood vessels;

inhibition of the release of vasoactive neuropeptides from perivascular trigeminal sensory neurons;

reduction of pain signal transmission in the trigeminal dorsal horn.

It is used for acute treatment, having no efficacy in preventing future attacks.

Why it is important to do this review

There are a number of studies investigating the efficacy and tolerability of zolmitriptan for the treatment of acute migraine attacks, but no Cochrane review of these studies. Several treatment options are available to treat acute migraine headaches, including sumatriptan (Derry 2012a; Derry 2012b; Derry 2012c; Derry 2012d) and common OTC analgesics such as aspirin (Kirthi 2013), ibuprofen (Rabbie 2013), and paracetamol (Derry 2013). This is one of a series of reviews planned for acute treatments for migraine headaches.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and tolerability of zolmitriptan compared to placebo and other active interventions in the treatment of acute migraine headaches in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐ or active‐controlled studies using zolmitriptan to treat a migraine headache episode. Studies had to have a minimum of 10 participants per treatment arm and report dichotomous data for at least one of the outcomes specified below. We accepted studies reporting treatment of consecutive headache episodes if outcomes for the first, or each, episode were reported separately; we used first‐attack data preferentially. We accepted cross‐over studies if there was adequate (≥ 48 hours) washout between treatments.

Types of participants

Studies enrolled adults (at least 18 years of age) with episodic migraine. We used the definition of migraine specified by the International Headache Society (IHS) (IHS 1988; IHS 2004; IHS 2013) and excluded studies evaluating treatments for chronic migraine. There were no other restrictions on migraine frequency, duration, or type (with or without aura). We accepted studies that included participants taking stable prophylactic therapy to reduce the frequency of migraine attacks. If reported, details on any prophylactic therapy prescribed or allowed are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Types of interventions

We included studies that used a single dose of zolmitriptan to treat a migraine headache episode when pain was of moderate to severe intensity, or investigated different dosing strategies or timing of the first dose in relation to headache intensity, or both. There were no restrictions on dose or route of administration, provided the medication was self‐administered.

A placebo comparator is essential to demonstrate that zolmitriptan is effective in this condition. We considered active‐controlled trials without a placebo as secondary evidence. We excluded studies designed to demonstrate prophylactic efficacy in reducing the number or frequency of migraine attacks.

Types of outcome measures

In selecting the main outcome measures for this review, we considered scientific rigour, availability of data, and patient preferences. Patients with acute migraine headaches have rated complete pain relief, no headache recurrence, rapid onset of pain relief, and no side effects as the four most important outcomes (Lipton 1999).

In view of these patient preferences, and in line with the guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine issued by the IHS (IHS 2000), we considered the following main outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Pain‐free at two hours, without the use of rescue medication.

Reduction in headache pain ('headache relief') at two hours (pain reduced from moderate or severe to none or mild without the use of rescue medication).

We also collected data for pain‐free and headache relief outcomes at one hour if reported and relevant, for example, if a fast‐acting formulation of the intervention was tested. For the purposes of this review, we considered the nasal spray and oral disintegrating tablet formulations to be potentially fast‐acting.

Secondary outcomes

Sustained pain‐free during the 24 hours postdose (pain‐free within two hours, with no use of rescue medication or recurrence of pain of any intensity within 24 hours).

Sustained headache relief during the 24 hours postdose (headache relief at two hours, with no use of rescue medication or a second dose of study medication, or recurrence of moderate or severe pain within 24 hours).

Adverse events: participants with any adverse event during the 24 hours postdose; serious adverse events; adverse events leading to withdrawal.

Other outcomes

We also collected data for other outcomes, including:

use of rescue medication;

relief of headache‐associated symptoms;

relief of functional disability.

Pain intensity or pain relief had to be measured by the participant (not the investigator or care giver). Pain measures accepted for the main efficacy outcomes were the following.

Pain intensity: 4‐point categorical scale, with wording equivalent to none, mild, moderate and severe; or 100 mm VAS, where < 30 mm was considered equivalent to mild or no pain and ≥ 30 mm equivalent to moderate or severe pain (Collins 1997).

Pain relief: 5‐point categorical scale, with wording equivalent to none, a little, some, a lot, complete; or 100 mm VAS, where < 30 mm was considered equivalent to none or a little, and ≥ 30 mm equivalent to some, a lot or complete.

Definitions of important terms, including all measured outcomes, are provided in Appendix 1.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), The Cochrane Library (Issue 3 of 12, 2014).

MEDLINE (via Ovid) (1990 to 12 March 2014).

EMBASE (via Ovid) (1990 to 12 March 2014).

Oxford Pain Relief Database, searched on 22 May 2013 (Jadad 1996a).

See Appendix 2, Appendix 3, and Appendix 4 for the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE (via Ovid), and EMBASE (via Ovid), respectively.

Searches of MEDLINE and EMBASE started in 2009 because we were looking only for randomised controlled trials and these two databases are routinely searched and all controlled trials added to CENTRAL. This may not capture studies that have been published or indexed in the previous year, but searching back to 2009 provided a considerable overlap. We did not apply any language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We searched for additional studies in reference lists of retrieved studies and review articles, and in three clinical trials databases (www.astrazenecaclinicaltrials.com, www.clinicaltrials.gov, and apps.who.int/trialsearch). AstraZeneca, the manufacturer of Zomig, provided a database search of publications relating to zolmitriptan in migraine; no mention of unpublished data was made. No studies, published or unpublished, were identified in the list they provided that were not identified by our searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently carried out the searches and selected studies for inclusion. We viewed the titles and abstracts of all studies identified by the electronic searches on screen and excluded any that clearly did not satisfy the inclusion criteria. We read full copies of the remaining studies to identify those suitable for inclusion. Disagreements were settled by discussion with a third review author.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from the included studies using a standard data extraction form. We settled disagreements by discussion with a third review author. One review author entered data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2012).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Oxford Quality Score (Jadad 1996b) as the basis for inclusion, limiting inclusion to studies that were randomised and double‐blind as a minimum. The scores for each study are reported in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and adapted from those used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group, with any disagreements resolved by discussion. We assessed the following for each study.

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). We assessed the method used to generate the allocation sequence as: low risk of bias (any truly random process, eg random number table; computer random number generator); unclear risk of bias (method used to generate sequence not clearly stated). We excluded studies using a non‐random process (eg odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number).

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). The method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment determines whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed the methods as: low risk of bias (eg telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes); unclear risk of bias (method not clearly stated). We excluded studies that did not conceal allocation (eg open list).

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias). We assessed the methods used to blind study participants and outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed the methods as: low risk of bias (study states that it was blinded and describes the method used to achieve blinding, eg identical tablets; matched in appearance and smell); unclear risk of bias (study states that it was blinded but does not provide an adequate description of how it was achieved). We excluded studies that were not double‐blind.

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature, and handling of incomplete outcome data). We assessed the methods used to deal with incomplete data as: low risk (< 10% of participants provided no data without acceptable reason, eg they were randomised but did not have a qualifying headache). We excluded studies with high data loss.

Size of study (checking for possible biases confounded by small size). We assessed studies as being at low risk of bias (≥ 200 participants per treatment arm); unclear risk of bias (50 to 199 participants per treatment arm); high risk of bias (< 50 participants per treatment arm).

Measures of treatment effect

We used risk ratios (relative risk; RR) to establish statistical difference. Numbers needed to treat (NNT) and pooled percentages were used as absolute measures of benefit or harm.

We used the following terms to describe adverse outcomes in terms of harm or prevention of harm:

when significantly fewer adverse outcomes occurred with zolmitriptan than with control (placebo or active), we use the term the number needed to treat to prevent one event (NNTp).

when significantly more adverse outcomes occurred with zolmitriptan compared with control (placebo or active), we use the term the number needed to harm or cause one event (NNH).

Unit of analysis issues

We accepted randomisation to the individual patient only. For analysis of studies with more than one treatment arm contributing to any one analysis (for example two formulations of the same dose of zolmitriptan in the same study with a single placebo group), we would split the placebo group equally between the two treatment arms so as not to double‐count placebo participants.

Where participants treated more than one attack we used first attack data preferentially. When that was not reported we have used data from combined attacks and have considered how this might affect the results.

Dealing with missing data

The most likely source of missing data was in cross‐over studies; we planned to use only the first‐period data where possible, but where that was not provided we treated the results as if they were parallel group results. Where there were substantial missing data in any study, we would comment on this and perform sensitivity analyses to investigate their effect.

For all outcomes we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on a modified intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis, that is, we included all participants who were randomised and received an intervention. Where sufficient information was reported, we re‐included missing data in the analyses we undertook. We planned to exclude data from outcomes where data from 10% or more of participants were missing with no acceptable reason provided or apparent.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity of response rates using L'Abbé plots, a visual method for assessing differences in the results of individual studies (L'Abbé 1987). Where data could be pooled, we reported the I2 statistic.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed publication bias by examining the number of participants in trials with zero effect (relative risk of 1.0) needed for the point estimate of the NNT to increase beyond a clinically useful level (Moore 2008). In this case, we specified a clinically useful level as a NNT of 8 or greater for pain‐free at two hours, and NNT of 6 or greater for headache relief at two hours.

Data synthesis

We analysed studies using a single dose of zolmitriptan in established pain of at least moderate intensity separately from studies in which the medication was taken before pain became well established, or in which a second dose of medication was permitted.

We calculated effect sizes and combined data for analysis only for comparisons and outcomes where there were at least two studies and 200 participants (Moore 1998). Relative risk (RR) of benefit ('relative benefit') or harm ('relative risk') was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a fixed‐effect model (Morris 1995). We calculated NNT, NNTp, and NNH with 95% CIs, where possible, using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). We assumed a statistically significant difference from control when the 95% CI of the RR of benefit or harm did not include the number one.

We used the z test (Tramer 1997) to determine significant differences between NNT, NNTp, and NNH for different groups in subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

We described data from comparisons and outcomes with only one study or fewer than 200 participants in the summary tables and text, where appropriate, for information and comparison, but we did not analyse these data quantitatively.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Issues for potential subgroup analysis were dose, formulation, and route of administration.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analysis for study quality (Oxford Quality Score of 2 versus 3 or more) and for migraine type (with aura versus without aura). A minimum of two studies and 200 participants had to be available for any sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

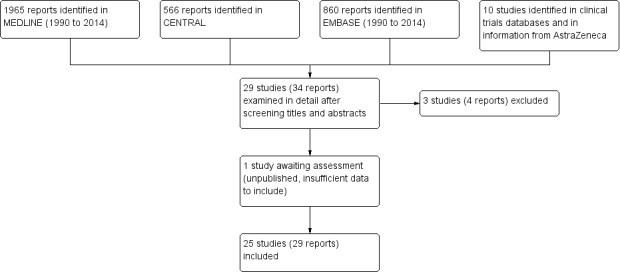

Searches of bibliographic databases identified over 800 potentially relevant reports, of which 34 were examined in detail after screening titles and abstracts. We included 25 studies in the review, two of which had published subgroup analyses in three additional reports, and another had a published post‐hoc analysis. We also identified, from the World Health Organization (WHO) international clinical trials registry platform, one additional study with 126 participants (CTRI/2009/091/000196). This study appears to satisfy the inclusion criteria, but has not been published, and the report does not provide sufficient data for us to include it in this review. The report claims that results "are similar to the published studies"; details are in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. Three studies (four reports) were excluded (Figure 1).

1.

Flow diagram.

Included studies

Twenty‐five studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria for this review (311CIL/0099 2000; Charlesworth 2003; Dahlof 1998; Dib 2002; Dodick 2005; Dowson 2002; Gallagher 2000; Gawel 2005; Geraud 2000; Geraud 2002; Goadsby 2007b; Gruffyd‐Jones 2001; Ho 2008; Klapper 2004; Loder 2005; Pascual 2000; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Sakai 2002; Solomon 1997; Spierings 2004; Steiner 2003; Tuchman 2006; Tullo 2010; Visser 1996) with contributions from a total of 20,162 participants.

The studies tested the following interventions.

Zolmitriptan standard oral tablet versus placebo (311CIL/0099 2000; Charlesworth 2003; Dahlof 1998; Dib 2002; Geraud 2000; Ho 2008; Klapper 2004; Pascual 2000; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Sakai 2002; Solomon 1997; Steiner 2003; Tuchman 2006; Visser 1996).

Zolmitriptan oral disintegrating tablet versus placebo (Dowson 2002; Loder 2005; Spierings 2004).

Zolmitriptan nasal spray versus placebo (Charlesworth 2003; Dodick 2005; Gawel 2005).

Zolmitriptan versus ketoprofen (Dib 2002).

Zolmitriptan versus sumatriptan (Gallagher 2000; Geraud 2000; Gruffyd‐Jones 2001).

Zolmitriptan versus acetylsalicylic acid plus metoclopramide (Geraud 2002).

Zolmitriptan versus almotriptan (Goadsby 2007b).

Zolmitriptan versus telcagepant (Ho 2008).

Zolmitriptan versus rizatriptan (Pascual 2000).

Zolmitriptan versus eletriptan (Steiner 2003).

Zolmitriptan versus frovatriptan (Tullo 2010).

Zolmitriptan versus naratriptan (311CIL/0099 2000).

Participants included in all of the studies were diagnosed with migraine with or without aura in accordance with the IHS criteria (IHS 1988; IHS 2004), typically had a history of migraine for more than one year, and suffered from one to six migraine attacks per month, with slight variances. For the most part, the participants recruited into the studies were between 18 and 65 years of age, although Goadsby 2007b included participants aged 16 to 65 years and Solomon 1997 and Rapoport 1997 included participants aged 12 to 65 years. In addition, Pascual 2000 and Gallagher 2000 were not explicit about the age range of those included, but the mean ages were 39 years and 40 years, respectively. Although this review is focused on zolmitriptan for acute migraine solely in adults, we included these studies because we felt that the number of individuals younger than 18 years was small, and because all were ≥ 12 years of age they were likely to require an adult dose. Stable prophylactic medications were allowed in most of the studies with the exception of Visser 1996, in which patients were excluded if they had used prophylactic treatment in the month before the study. Almost all studies stated that study medication was not to be used within 24 hours of taking a triptan or an ergot derivative. All studies included both men and women, except the study concerning menstrual migraine (Tuchman 2006). The participants in Tuchman 2006 were required to have a diagnosis of menstrual migraine (IHS 1988), with migraine occurring within two days of the expected onset of menses to five days after onset, and with > 75% of all menstrual periods associated with migraine attacks.

Twenty‐two of the included studies had a parallel‐group design, and three had a cross‐over design, of which Dib 2002 and Ryan 2000 specified at least 48 hours between treated attacks, and Tullo 2010 did not report a minimum time, but had a 48‐hour outcome, implying that qualifying attacks had to be separated by at least that period. Most studies instructed participants to treat a single migraine attack with the study medication, though in five studies participants treated multiple attacks (Charlesworth 2003; Dodick 2005; Gallagher 2000; Gruffyd‐Jones 2001; Tuchman 2006). Only in Charlesworth 2003 and Dodick 2005 could first‐attack data for certain criteria be extracted, and these data were used where possible.

In all studies rescue medication was allowed if the headache persisted, typically two hours after study medication had been taken. In a number of studies a second dose of study medication was allowed, either if the headache persisted or if it recurred (311CIL/0099 2000; Dowson 2002; Gallagher 2000; Gawel 2005; Geraud 2002; Goadsby 2007b; Gruffyd‐Jones 2001; Ho 2008; Klapper 2004; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Spierings 2004; Steiner 2003; Tullo 2010; Visser 1996). The administration of zolmitriptan was via an oral tablet (standard or disintegrating) or a nasal spray, with the majority of studies using the standard oral tablet formulation.

In most studies the treated migraine attacks had to be of moderate or severe baseline intensity. Gallagher 2000 did not state pain intensity in the methods, but reported results for reduction from at least moderate to no greater than mild; Gawel 2005 treated any severity, but fewer than 10% were mild, and results were reported separately for attacks of moderate or severe baseline intensity; Loder 2005 treated 'as soon as possible', but reported some outcomes for attacks of moderate or severe baseline intensity; Tullo 2010 treated 'as soon as possible', reporting for mixed baseline pain intensities. Finally, Klapper 2004 treated when pain intensity was mild.

Some studies were inconsistent in the denominators reported, so that the population varied slightly in size for different outcomes or at different time points. Where this variance was not explained in the text, the denominators were changed to the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) number if this gave a more conservative estimate of the efficacy of the drug.

Excluded studies

Five studies were excluded after reading the full report (Dodick 2011; Dowson 2003; Loder 2004; Mauskop 1999; Tepper 1999). The reasons for exclusion are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

The included studies were all randomised and double‐blind. The majority of the studies provided information about withdrawals and dropouts; Goadsby 2007b, Steiner 2003, and Tullo 2010 either made no statement about withdrawals or did not give an adequate explantation for differing denominators. The methodological quality of the trials was determined using the Oxford Quality Scale (Jadad 1996a). Six studies (Charlesworth 2003; Dahlof 1998; Geraud 2002; Gruffyd‐Jones 2001; Ho 2008; Visser 1996) scored 5/5, 11 studies (Dib 2002; Dodick 2005; Dowson 2002; Gawel 2005; Geraud 2000; Klapper 2004; Loder 2005; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Spierings 2004; Steiner 2003) scored 4/5, seven studies (311CIL/0099 2000; Gallagher 2000; Goadsby 2007b; Pascual 2000; Sakai 2002; Solomon 1997; Tuchman 2006) scored 3/5 and one study (Tullo 2010) scored 2/5. Points were lost mainly due to inadequate description of the method of randomisation or double blinding, and also due to lack of information about withdrawals and drop‐outs. Most studies were performed for registration or other purposes by pharmaceutical companies and would have had to satisfy very strict requirements to randomisation and allocation concealment, and effectiveness of double blinding, although these were not always fully reported in the published studies. Details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

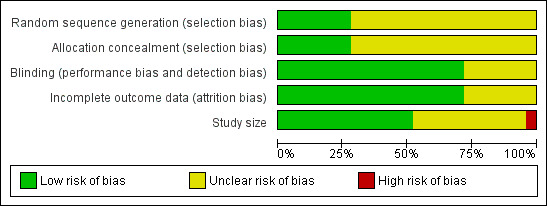

In addition a risk of bias table was created which considered sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and study size (Figure 2). Only one study (Visser 1996) was identified as being at high risk of bias, due to small size, although one other study (Sakai 2002) had group sizes very close to the cut‐off point of 50.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

All included studies used a four‐point categorical scale (none, mild, moderate, severe) for rating pain intensity.

In the great majority of studies participants treated attacks when pain was of moderate to severe intensity, or the study reported efficacy results separately for attacks where the baseline pain was moderate to severe. There were sufficient data for at least the primary outcomes of pain‐free and headache relief at two hours for pooled analyses of zolmitriptan versus placebo at doses of 1 mg, 2.5 mg, 5 mg and 10 mg, when used to treat moderate to severe pain. There were insufficient data to allow pooled analysis from studies in which participants treated attacks when pain was mild, or that included mixed baseline intensities. Unless otherwise stated, results reported in this review are for attacks of moderate to severe baseline pain intensity. There were also insufficient data from studies that allowed second or third doses of medication for a single attack in order to allow analysis of these different dosing strategies.

Analyses of other doses of zolmitriptan versus placebo and almost any dose of zolmitriptan versus an active comparator, for any outcome, were not possible because there were insufficient data; it was common for only one study to provide data. We have reported results where analyses were possible in the text and tables in this section, and details of all results in individual studies are available in Appendix 5 (efficacy) and Appendix 6 (adverse events and withdrawals).

For all analysis graphs, studies have used oral tablets unless otherwise noted in the footnotes.

See 'Summary of results A' for results of all efficacy outcomes.

Pain‐free at two hours

Zolmitriptan 1 mg versus placebo

Four studies (1200 attacks) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 1 mg with placebo. Three studies used an oral tablet formulation (Rapoport 1997; Sakai 2002; Visser 1996) and one a nasal spray formulation (Charlesworth 2003).

The proportion of attacks pain‐free at two hours with zolmitriptan 1 mg was 22% (138/621; range 9% to 25%).

The proportion of attacks pain‐free at two hours with placebo was 8.1% (47/579; range 5% to 14%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.7 (95% CI 2.0 to 3.7; Analysis 1.1); the NNT was 7.1 (5.5 to 9.9).

For oral treatment alone, the relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 1.9 (1.1 to 3.3) and the NNT was 14 (7.4 to 170).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Zolmitriptan 1 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Pain‐free at 2 h.

Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo

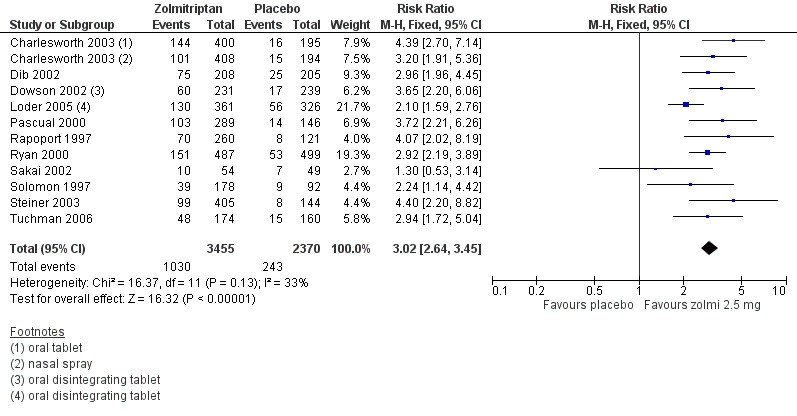

Eleven studies (5825 attacks) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 2.5 mg with placebo. Each of the 11 studies used an oral tablet (Charlesworth 2003; Dib 2002; Dowson 2002; Loder 2005; Pascual 2000; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Sakai 2002; Solomon 1997; Steiner 2003; Tuchman 2006), with one of these studies also providing information on the use of a zolmitriptan 2.5 mg nasal spray (Charlesworth 2003).

The proportion of attacks pain‐free at two hours with zolmitriptan 2.5 mg was 30% (1030/3455; range 19% to 36%).

The proportion of attacks pain‐free at two hours with placebo was 10% (243/2370; range 6% to 17%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 3.0 (2.6 to 3.5) (Figure 3; Analysis 2.1); the NNT was 5.1 (4.7 to 5.7).

For oral treatment alone, the relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 3.0 (2.6 to 3.5) and the NNT was 5.0 (4.5 to 5.6).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo, outcome: 2.1 Pain‐free at 2 h. Studies without footnotes use the standard oral tablet.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Pain‐free at 2 h.

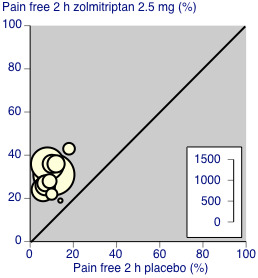

Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg was significantly better than 1 mg (z = 3.933, P = 0.0001). A L'Abbé plot shows the similarity in results between studies (Figure 4).

4.

L'Abbé plot showing results for zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo for pain‐free at 2 hours. Each circle represents a different study; size of circle is proportional to size of study; diagonal is line of equivalence

Klapper 2004 compared zolmitriptan 2.5 mg with placebo to treat headache of mild intensity; 43% (59/138) of participants were pain‐free at two hours with zolmitriptan, while 18% (26/142) experienced this outcome with placebo.

Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo

Eleven studies (9372 attacks) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 5 mg with placebo. Eight studies used an oral tablet formulation (Dahlof 1998; Geraud 2000; Ho 2008; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Sakai 2002; Spierings 2004; Visser 1996), whilst the other three studies used a nasal spray formulation (Charlesworth 2003; Dodick 2005; Gawel 2005).

The proportion of attacks pain‐free at two hours with zolmitriptan 5 mg was 32% (1616/5024; range 14% to 39%).

The proportion of attacks pain‐free at two hours with placebo was 11% (481/4348; range 2% to 14%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 3.0 (2.7 to 3.2; Analysis 3.1); the NNT was 4.7 (4.4 to 5.1).

For oral treatment alone, the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 3.2 (2.7 to 3.7) and the NNT was 4.8 (4.3 to 5.4), while for nasal spray alone, the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 2.8 (2.5 to 3.2) and the NNT was 4.6 (4.2 to 5.2).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Pain‐free at 2 h.

There was no statistically significant difference between the two formulations for the outcome of pain‐free at two hours (z = 0.53, P = 0.10).

Zolmitriptan 10 mg versus placebo

Two studies (648 participants) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 10 mg with placebo. Both studies used an oral tablet formulation (Dahlof 1998; Rapoport 1997).

The proportion of participants pain‐free at two hours with zolmitriptan 10 mg was 37% (163/439; range 36% to 39%).

The proportion of participants pain‐free at two hours with placebo was 5% (10/209; range 2% to 7%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 7.8 (4.2 to 14.5; Analysis 4.1); the NNT was 3.1 (2.7 to 3.7).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Zolmitriptan 10 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Pain‐free at 2 h.

The oral 10 mg dose was significantly better than the oral 5 mg dose for pain‐free at two hours (z = 3.882, P = 0.0001).

Headache relief at two hours

Zolmitriptan 1 mg versus placebo

Four studies (861 participants) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 1 mg with placebo. Three studies used an oral tablet formulation (Rapoport 1997; Sakai 2002; Visser 1996), and one used a nasal spray formulation (Charlesworth 2003).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at two hours with zolmitriptan 1 mg was 55% (333/626; range 27% to 55%).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at two hours with placebo was 31% (183/589; range 15% to 34%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1) (Analysis 1.2); the NNT was 4.3 (3.3 to 5.9).

For oral treatment alone the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0) and the NNT was 5.6 (3.7 to 12).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Zolmitriptan 1 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Headache relief at 2 h.

Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo

Eleven studies (4904 participants or attacks) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 2.5 mg with placebo. Each of the studies used an oral tablet formulation (311CIL/0099 2000; Charlesworth 2003; Dib 2002; Dowson 2002; Pascual 2000; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Sakai 2002; Spierings 2004; Tuchman 2006), with one of these studies also providing information on the use of a zolmitriptan 2.5 mg nasal spray (Charlesworth 2003).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at two hours with zolmitriptan 2.5 mg was 60% (1758/2921; range 54% to 67%).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at two hours with placebo was 29% (584/1983; range 21% to 36%).

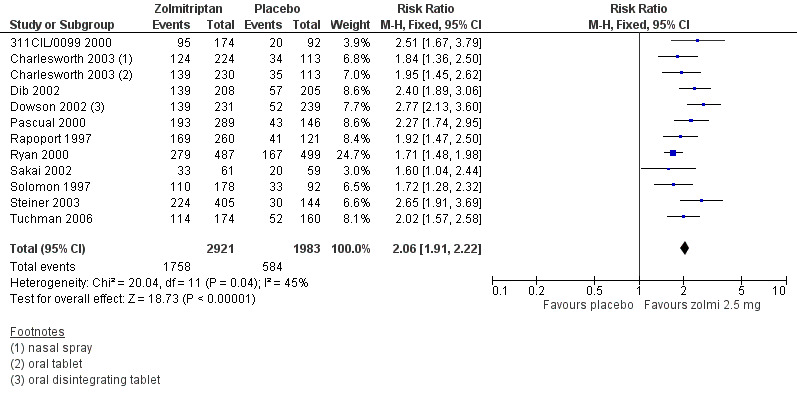

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.1 (1.9 to 2.2) (Figure 5: Analysis 2.2); the NNT was 3.3 (3.0 to 3.6).

For oral treatment alone the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 2.1 (1.9 to 2.2) and the NNT was 3.2 (3.0 to 3.5).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo, outcome: 2.2 Headache relief at 2 h. Studies without footnotes use the standard oral tablet.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Headache relief at 2 h.

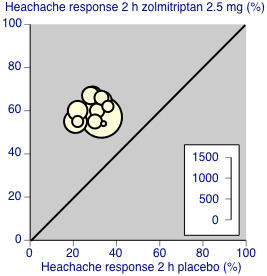

Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg was significantly better than 1 mg (z = 2.657, P = 0.008). A L'Abbé plot shows the similarity in results between studies (Figure 6).

6.

L'Abbé plot showing results for zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo for headache relief at 2 hours. Each circle represents a different study; size of circle is proportional to size of study; diagonal is line of equivalence

Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo

Eleven studies (7456 participants) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 5 mg with placebo. Eight studies used an oral tablet formulation (Dahlof 1998; Geraud 2000; Ho 2008; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Sakai 2002; Spierings 2004; Visser 1996), whilst the other three studies used a nasal spray formulation (Charlesworth 2003; Dodick 2005; Gawel 2005).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at two hours with zolmitriptan 5 mg was 63% (2537/4046; range 56% to 69%).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at two hours with placebo was 32% (1078/3410; range 15% to 43%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.0 (1.9 to 2.1; Analysis 3.2); the NNT was 3.2 (3.1 to 3.5).

For oral treatment alone, the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 1.9 (1.8 to 2.1) and the NNT was 3.5 (3.2 to 3.9), while for nasal spray alone, the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 2.1 (1.9 to 2.2) and the NNT was 2.9 (2.6 to 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Headache relief at 2 h.

The nasal spray formulation was significantly better than oral tablets for the outcome of headache relief at two hours (z = 2.746, P = 0.006).

Zolmitriptan 10 mg versus placebo

Two studies (648 participants) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 10 mg with placebo. Both studies used an oral tablet formulation (Dahlof 1998; Rapoport 1997).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at two hours with zolmitriptan 10 mg was 69% (302/439; range 67% to 71%).

The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at two hours with placebo was 28% (58/209; range 19% to 34%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.5 (2.0 to 3.1; Analysis 4.2); the NNT was 2.4 (2.1 to 3.0).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Zolmitriptan 10 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Headache relief at 2 h.

The oral 10 mg dose was significantly better than the oral 5 mg dose for headache relief at two hours (z = 2.987, P = 0.003).

Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg

Two studies (1609 attacks) compared zolmitriptan 2.5 mg with sumatriptan 50 mg (Gallagher 2000; Gruffyd‐Jones 2001). Both studies used oral tablets.

The proportion of attacks with headache relief at two hours with zolmitriptan 2.5 mg was 66% (521/795; range 65% to 67%).

The proportion of attacks with headache relief at two hours with sumatriptan 50 mg was 68% (554/814; range 64% to 71%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 0.96 (0.90 to 1.03; Analysis 5.1). There was no significant difference between treatments.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Zolmiriptan 2.5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg, Outcome 1 Headache relief at 2 h.

Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg

Two studies (1633 attacks) compared zolmitriptan 5 mg with sumatriptan 50 mg (Gallagher 2000; Gruffyd‐Jones 2001). Both studies used oral tablets.

The proportion of attacks with headache relief at two hours with zolmitriptan 5 mg was 67% (545/819; range 65% to 68%).

The proportion of attacks with headache relief at two hours with sumatriptan 50 mg was 68% (554/814; range 64% to 71%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 0.98 (0.92 to 1.1; Analysis 6.1). There was no significant difference between treatments.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Zolmitripan 5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg, Outcome 1 Headache relief at 2 h.

Headache relief at one hour

Two studies provided data for the 5 mg dose of the nasal spray (potentially fast‐acting) formulation for this outcome (Charlesworth 2003; Dodick 2005). There were insufficient data for analysis of any other dose of the nasal spray, or for any dose of the oral disintegrating tablet.

Zolmitriptan 5 mg nasal spray versus placebo

The proportion of attacks with headache relief at one hour with zolmitriptan 5 mg nasal spray was 56% (763/1362; range 54% to 57%).

The proportion of attacks with headache relief at one hour with placebo was 32% (420/1322; range 26% to 34%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 1.8 (1.6 to 1.9); the NNT was 4.2 (3.6 to 4.9) (Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 Headache relief at 1 h.

Zolmitriptan 5 mg oral tablets versus placebo

To investigate whether the nasal spray formulation was better at this early time point than the standard oral tablet, we also analysed the six studies using the same dose of standard oral tablets that reported this outcome (Dahlof 1998; Geraud 2000; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Sakai 2002; Visser 1996).

The proportion of attacks with headache relief at one hour with zolmitriptan 5 mg standard oral tablets was 38% (558/1477; range 24% to 44%).

The proportion of attacks with headache relief at one hour with placebo was 22% (183/833; range 15% to 27%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1); the NNT was 6.3 (5.1 to 8.3) (Analysis 3.3).

Adding the single study that used an oral disintegrating tablet formulation (Spierings 2004) did not change the result (RR 1.8 (1.6 to 1.9), NNT 6.1 (5.2 to 7.5)).

The nasal spray formulation was significantly better than standard oral tablets for the outcome of headache relief at one hour (z = 3.168, P = 0.001).

Sustained pain‐free during the 24 hours postdose

Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo

Two studies (984 participants) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 2.5 mg with placebo. The two studies used an oral tablet formulation (Pascual 2000; Steiner 2003).

The proportion of participants experiencing a 24‐hour sustained pain‐free response with zolmitriptan 2.5 mg was 19% (129/694; range 15% to 24%).

The proportion of participants experiencing a 24‐hour sustained pain‐free response with placebo was 6% (16/290; range 4% to 7%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 3.5 (2.1 to 5.8; Analysis 2.3); the NNT was 7.7 (6.0 to 11).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 24‐h sustained pain‐free.

Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo

Three studies (4991 attacks) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 5 mg with placebo. One study used an oral tablet formulation (Ho 2008), whilst the other two studies used a nasal spray formulation (Dodick 2005; Gawel 2005).

The proportion of attacks with a 24‐hour sustained pain‐free response with zolmitriptan 5 mg was 14% (346/2516; range 11% to 23%).

The proportion of attacks with a 24‐hour sustained pain‐free response with placebo was 2.9% (73/2475; range 1.6% to 7.1%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 4.7 (3.6 to 5.9; Analysis 3.4); the NNT was 9.3 (8.1 to 11).

For nasal spray treatment alone, the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 4.9 (3.7 to 6.5; Analysis 3.4) and the NNT was 9.6 (8.3 to 11). There was no significant difference between formulations.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 4 24‐h sustained pain‐free.

Sustained headache relief during the 24 hours postdose

Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo

Four studies (2059 attacks) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 2.5 mg with placebo. Each of the four studies used an oral tablet formulation (Charlesworth 2003; Rapoport 1997; Sakai 2002; Steiner 2003), with one also providing information on the use of the zolmitriptan 2.5 mg nasal spray (Charlesworth 2003).

The proportion of attacks with 24‐hour sustained headache relief with zolmitriptan 2.5 mg was 39% (557/1436; range 31% to 46%).

The proportion of attacks with 24‐hour sustained headache relief with placebo was 14% (85/623; range 10% to 22%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.9 (2.4 to 3.6; Analysis 2.4); the NNT was 4.0 (3.5 to 4.7).

For oral treatment alone, the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 2.9 (2.2 to 3.7) and the NNT was 4.1 (3.5 to 5.0).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 4 24‐h sustained headache relief.

Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo

Seven studies (7106 attacks) provided data comparing zolmitriptan 5 mg with placebo. Five studies used an oral tablet formulation (Geraud 2000; Ho 2008; Rapoport 1997; Sakai 2002; Spierings 2004), whilst the other two studies used a nasal spray formulation (Charlesworth 2003; Dodick 2005).

The proportion of attacks with 24‐hour sustained headache relief with zolmitriptan 5 mg was 37% (1445/3854; range 35% to 49%).

The proportion of attacks with 24‐hour sustained headache relief with placebo was 12% (375/3252; range 9% to 25%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.9 (2.4 to 3.6); the NNT was 3.9 (3.6 to 4.2).

For oral treatment alone, the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 2.4 (2.0 to 2.8) and the NNT was 4.6 (4.0 to 5.3), while for nasal spray alone the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 4.0 (3.4 to 4.6) and the NNT was 3.6 (3.3 to 3.9) (Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 5 24‐h sustained headache relief.

The nasal spray formulation was significantly better than oral tablets for the outcome of sustained headache relief during the 24 hours post dose (z = 2.076, P = 0.039).

| Summary of results A: pain‐free and headache relief | |||||||

| Studies |

Attacks treated |

Treatment (%) |

Placebo or comparator (%) |

Relative benefit (95% CI) |

NNT (95% CI) |

P for difference | |

| Pain‐free at 2 hours | |||||||

| Zolmitriptan 1 mg (all formulations) versus placebo | 4 | 1200 | 22 | 8 | 2.7 (2.0 to 3.7) | 7.1 (5.5 to 9.9) | |

| Zolmitriptan 1 mg oral versus placebo | 3 | 384 | 15 | 8 | 1.9 (1.1 to 3.3) | 14 (7.4 to 170) | 1 mg oral vs 2.5 mg oral z = 3.933, P = 0.001 |

| Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg (all formulations) versus placebo | 12 | 5825 | 30 | 10 | 3.0 (2.6 to 3.5) | 5.1 (4.7 to 5.7) | |

| Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg oral versus placebo | 11 | 5223 | 30 | 10 | 3.0 (2.6 to 3.5) | 5.0 (4.5 to 5.6) | |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg (all formulations) versus placebo | 11 | 9372 | 33 | 11 | 3.0 (2.7 to 3.2) | 4.7 (4.4 to 5.1) | |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg oral versus placebo | 8 | 4277 | 31 | 10 | 3.2 (2.7 to 3.7) | 4.8 (4.3 to 5.4) | 5 mg oral versus 5 mg nasal z = 0.53, P = 0.10 |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg nasal spray versus placebo | 3 | 5095 | 34 | 12 | 2.8 (2.5 to 3.2) | 4.6 (4.2 to 5.2) | |

| Zolmitriptan 10 mg oral versus placebo | 2 | 648 | 37 | 5 | 7.8 (4.2 to 14) | 3.1 (2.7 to 3.7) | 10 mg oral versus 5 mg oral z = 3.882, P = 0.0001 |

| Headache relief at 2 hours | |||||||

| Zolmitriptan 1 mg (all formulations) versus placebo | 4 | 861 | 55 | 31 | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1) | 4.3 (3.3 to 5.9) | |

| Zolmitriptan 1 mg oral versus placebo | 3 | 399 | 50 | 32 | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0) | 5.6 (3.7 to 12) | 1 mg oral versus 2.5 mg oral z = 2.657, P = 0.008 |

| Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg (all formulations) versus placebo | 11 | 4904 | 60 | 29 | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.2) | 3.3 (3.0 to 3.6) | |

| Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg oral versus placebo | 10 | 4567 | 61 | 29 | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.2) | 3.2 (3.0 to 3.5) | |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg (all formulations) versus placebo | 11 | 7456 | 63 | 32 | 2.0 (1.9 to 2.1) | 3.2 (3.0 to 3.5) | |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg oral versus placebo | 8 | 4292 | 59 | 30 | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.1) | 3.5 (3.2 to 3.9) | 5 mg oral versus 5 mg nasal z = 2.746, P = 0.006 |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg nasal spray versus placebo | 3 | 3164 | 68 | 33 | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.2) | 2.9 (2.6 to 3.2) | |

| Zolmitriptan 10 mg oral versus placebo | 2 | 648 | 69 | 28 | 2.5 (2.0 to 3.1) | 2.4 (2.1 to 3.0) | 10 mg oral versus 5 mg oral z = 2.987, P = 0.003 |

| Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg (oral) | 2 | 1609 | 66 | 68 | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.0) | not calculated | |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg (oral) | 2 | 1633 | 67 | 68 | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.1) | not calculated | |

| Headache relief at 1 hour | |||||||

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg oral versus placebo | 7 | 3584 | 39 | 22 | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.1) | 6.1 (5.2 to 7.5) | 5 mg oral versus 5 mg nasal z = 3.284, P = 0.001 |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg nasal spray versus placebo | 2 | 2684 | 56 | 32 | 1.8 (1.6 to 1.9) | 4.1 (3.6 to 4.9) | |

| Sustained pain‐free during the 24 hours post dose | |||||||

| Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg oral versus placebo | 2 | 984 | 19 | 6 | 3.5 (2.1 to 5.8) | 7.7 (5.9 to 11) | |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg (all formulations) versus placebo | 3 | 4991 | 14 | 4 | 4.7 (3.6 to 5.9) | 9.3 (8.1 to 11) | |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg nasal spray versus placebo | 2 | 4298 | 13 | 3 | 4.9 (3.7 to 6.5) | 9.6 (8.3 to 11) | |

| Sustained headache relief during the 24 hours post dose | |||||||

| Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg (all formulations) versus placebo | 4 | 2059 | 39 | 14 | 2.9 (2.4 to 3.6) | 4.0 (3.5 to 4.7) | |

| Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg oral versus placebo | 4 | 1457 | 38 | 14 | 2.9 (2.2 to 3.7) | 4.1 (3.5 to 5.0) | |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg (all formulations) versus placebo | 7 | 7106 | 37 | 12 | 3.2 (2.9 to 3.5) | 3.9 (3.6 to 4.2) | |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg oral versus placebo | 5 | 2827 | 37 | 15 | 2.4 (2.0 to 2.8) | 4.6 (4.0 to 5.3) | 5 mg oral versus 5 mg nasal z = 2.076, P = 0.038 |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg nasal spray versus placebo | 2 | 4279 | 38 | 9 | 4.0 (3.4 to 4.6) | 3.6 (3.3 to 3.9) | |

Subgroup analyses of primary outcomes

Subgroup analyses for dose and route of administration have been carried out alongside the main analyses. Three studies (Dowson 2002; Loder 2005; Spierings 2004) used an oral disintegrating tablet (ODT) formulation, but only one study contributed to any analysis, so there were insufficient data for subgroup analysis. Results for ODT formulations fell within the range of the standard tablet formulation.

Sensitivity analyses of the primary outcomes

Only one study (Tullo 2010) scored fewer than 3 points on the Oxford Quality Scale, so no sensitivity analysis could be carried out for methodological quality. Similarly, only one study (Rapoport 1997) reported data separately for participants with and without aura, so no subgroup analysis could be carried out for this subtype.

Three studies (Dib 2002; Ryan 2000; Tullo 2010) used a cross‐over design. Only with Tullo 2010 did there appear to be potential for missing data, but this study did not contribute to any meta‐analyses. Cross‐over designs may introduce other biases (Elbourne 2002; Khan 1996) but removing these studies from any analyses did not affect the results.

None of the studies using a parallel group design had substantial amounts of missing data that might influence the results.

Adverse events

All except one study reported on the number of participants experiencing any adverse events after treatment; Visser 1996 did not report adverse events for the placebo group, so no comparison could be made. Most studies appeared to collect data using spontaneous reports in diary cards and at follow‐up review after the end of treatment. Gallagher 2000, Pascual 2000, Spierings 2004, and Visser 1996 did not provide any details of the method of adverse event data collection. The duration over which data were collected was not always specified and, where it was, there were differences between studies. Most studies probably collected data during the 24 hours following treatment, but Ho 2008 specified 48 hours, Solomon 1997 and Steiner 2003 7 days, and Rapoport 1997 10 days. Spierings 2004 collected data for 24 hours for non‐serious adverse events and 7 days for serious events, while Tullo 2010 reported only events that were considered 'treatment‐related'.

In some studies a second dose of study medication was taken, and in all studies rescue medication was allowed if there was an inadequate response after a given period of time. It was likely that in all cases adverse event data continued to be collected after such additional medication. Ryan 2000 reported adverse event data according to the total dose of study medication taken.

A number of studies treated more than one attack. In Gallagher 2000, first‐attack data were reported for adverse events, while Dodick 2005, Geraud 2002, and Ryan 2000 reported events in all attacks combined. Charlesworth 2003, Gruffyd‐Jones 2001, Spierings 2004, and Tullo 2010 reported events per treatment group, but it was unclear how multiple attacks were combined.

Despite these inconsistencies, we have included as much data as possible in the adverse event analyses in order to be more inclusive and conservative (Appendix 6). See 'Summary of results B' and 'Summary of results C' for adverse event results.

Treatments were generally described as well‐tolerated, with most adverse events being of mild or moderate severity and self‐limiting.

Participants experiencing any adverse event

Zolmitriptan 1 mg versus placebo

Three studies (856 attacks) comparing zolmitriptan 1 mg with placebo provided data. Two studies used an oral tablet (Rapoport 1997; Sakai 2002) and one used a nasal spray formulation (Charlesworth 2003).

The proportion of attacks with adverse events with zolmitriptan 1 mg was 31% (132/431; range 15% to 39%).

The proportion of attacks with adverse events with placebo was 24% (103/425; range 14% to 30%).

The relative harm of treatment compared with placebo was 1.3 (1.01 to 1.6; Analysis 1.3); the NNH was 16 (8.1 to 230).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Zolmitriptan 1 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 Any adverse event.

Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo

Twelve studies (6055 attacks) comparing zolmitriptan 2.5 mg with placebo provided data. Each of the 11 studies used an oral tablet formulation (Charlesworth 2003; Dib 2002; Dowson 2002; Klapper 2004; Loder 2005, Pascual 2000; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Sakai 2002; Solomon 1997; Steiner 2003; Tuchman 2006), with one also using a nasal spray formulation (Charlesworth 2003).

The proportion of attacks with adverse events with zolmitriptan 2.5 mg was 32% (1167/3628; range 16% to 63%).

The proportion of attacks with adverse events with placebo was 17% (422/2427; range 9% to 40%).

The relative harm of treatment compared with placebo was 1.7 (1.6 to 1.9; Analysis 2.5); the NNH was 6.8 (5.9 to 7.9).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 5 Any adverse event.

Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo

Ten studies (9072 attacks) comparing zolmitriptan 5 mg with placebo provided data. Seven studies used an oral tablet formulation (Dahlof 1998; Geraud 2000; Ho 2008; Rapoport 1997; Ryan 2000; Sakai 2002; Spierings 2004), whilst the other three studies used a nasal spray formulation (Charlesworth 2003; Dodick 2005; Gawel 2005).

The proportion of attacks with adverse events with zolmitriptan 5 mg was 41% (2101/5065; range 20% to 61%).

The proportion of attacks with adverse events with placebo was 19% (742/4007; range 9% to 34%).

The relative harm of treatment compared with placebo was 2.2 (2.0 to 2.3; Analysis 3.6); the NNH was 4.4 (4.0 to 4.7).

For oral treatment alone, the relative harm of treatment compared to placebo was 2.0 (1.8 to 2.2) and the NNH was 4.6 (4.2 to 5.3), while for nasal spray alone the relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo was 2.4 (2.1 to 2.6) and the NNH was 4.2 (3.8 to 4.7) (Analysis 3.6).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo, Outcome 6 Any adverse event.

There was no statistically significant difference between the two formulations for participants experiencing any adverse events.

Zolmitriptan 10 mg versus placebo

Two studies (736 participants) comparing zolmitriptan 10 mg with placebo provided data. Both studies used an oral tablet formulation (Dahlof 1998; Rapoport 1997).

The proportion of participants experiencing adverse events with zolmitriptan 10 mg was 71% (352/499; range 67% to 75%).

The proportion of participants experiencing adverse events with placebo was 32% (75/237; range 30% to 34%).

The relative harm of treatment compared with placebo was 2.2 (1.8 to 2.7; Analysis 4.3); the NNH was 2.6 (2.2 to 3.2).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Zolmitriptan 10 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 Any adverse event.

Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg

Two studies (1771 attacks) comparing zolmitriptan 2.5 mg with sumatriptan 50 mg provided data. Both studies used oral tablet formulations (Gallagher 2000; Gruffyd‐Jones 2001).

The proportion of attacks with adverse events with zolmitriptan 2.5 mg was 32% (283/878; range 28% to 35%).

The proportion of attacks with adverse events with sumatriptan 50 mg was 28% (251/893; range 18% to 34%).

The relative harm of treatment compared with placebo was 1.1 (0.99 to 1.3; Analysis 5.2). The NNH was not calculated.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Zolmiriptan 2.5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg, Outcome 2 Any adverse event.

Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg

Two studies (1789 attacks) comparing zolmitriptan 5 mg with sumatriptan 50 mg provided data. Both studies used oral tablet formulations (Gallagher 2000; Gruffyd‐Jones 2001).

The proportion of attacks with adverse events with zolmitriptan 5 mg was 31% (280/896; range 21% to 38%).

The proportion of attacks with adverse events with sumatriptan 50 mg was 28% (251/893; range 18% to 34%).

The relative harm of treatment compared with placebo was 1.1 (0.96 to 1.3; Analysis 6.2). The NNH was not calculated.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Zolmitripan 5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg, Outcome 2 Any adverse event.

| Summary of results B: number of participants experiencing any adverse event (all formulations) | |||||||

| Comparison | Studies | Participants | Zolmitriptan (%) | Comparator (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) | P for difference |

| Zolmitriptan 1 mg versus placebo | 3 | 856 | 31 | 24 | 1.3 (1.01 to 1.6 ) | 16 (8.1 to 230) | 1 mg v 2.5 mg z = 2.596, P = 0.010 |

| Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus placebo | 13 | 5489 | 32 | 17 | 1.7 (1.6 to 1.9) | 6.8 (5.9 to 7.9) | 2.5 mg v 5 mg z = 5.718, P < 0.0001 |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus placebo | 10 | 9072 | 41 | 19 | 2.2 (2.0 to 2.3) | 4.4 (4.0 to 4.7) | 5 mg v 10 mg z = 4.236, P < 0.0001 |

| Zolmitriptan 10 mg versus placebo | 2 | 736 | 71 | 32 | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.7) | 2.6 (2.2 to 3.2) | |

| Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg | 2 | 1771 | 32 | 28 | 1.1 (0.99 to 1.3) | not calculated | |

| Zolmitriptan 5 mg versus sumatriptan 50 mg | 2 | 1789 | 31 | 28 | 1.1 (0.96 to 1.3) | not calculated | |

There was a clear dose response relationship for zolmitriptan in comparisons with placebo, with significantly more participants experiencing adverse events with each dose increment. Excluding studies that reported over periods greater than 24 hours did not significantly change the results. There was no significant difference between zolmitriptan 5 mg and sumatriptan 50 mg.

Participants experiencing serious adverse events

Three studies did not specifically comment on serious adverse events (Goadsby 2007b; Tullo 2010; Visser 1996), four reported that there were none during the study (Rapoport 1997; Sakai 2002; Steiner 2003; Tuchman 2006), and two reported that there were no drug‐related serious adverse events (Geraud 2000; Solomon 1997). The remaining 17 studies all reported at least one serious adverse event, although most occurred outside the 24‐hour post dose window, and most were judged to be unrelated to any study medication.

In studies reporting occurrence of serious adverse events separately for the zolmitriptan and placebo treatment arms (Charlesworth 2003; Dahlof 1998; Dib 2002; Dodick 2005; Dowson 2002; Gawel 2005; Ho 2008; Klapper 2004; Loder 2005; Pascual 2000; Spierings 2004), or the absence of such events (Rapoport 1997; Sakai 2002; Steiner 2003; Tuchman 2006), the incidence was ≤ 1% in any treatment arm, and overall was 0.33% (22/6647) for all doses ≥ 1 mg (including second doses and rescue medication) and all formulations of zolmitriptan combined, and 0.20% (8/3914) for placebo. There was no evidence of a dose response relationship, and there were too few events to calculate RR or NNH. Further details of individual studies are in Appendix 6.

Withdrawals due to adverse events

Ten studies either did not specifically report on adverse event withdrawals, did not report data for each treatment arm separately, or did not report clearly either whether the percentage referred to patients or attacks, or how multiple attacks were handled (311CIL/0099 2000; Dahlof 1998; Dib 2002; Gallagher 2000; Geraud 2000; Ho 2008; Ryan 2000; Sakai 2002; Solomon 1997; Tullo 2010). The remaining studies reported the number of withdrawals per treatment group.

In studies reporting the occurrence of adverse event withdrawals separately for zolmitriptan and placebo treatment arms (Charlesworth 2003; Dodick 2005; Gawel 2005; Loder 2005; Spierings 2004; Tuchman 2006), or the absence of such withdrawals (Dowson 2002; Klapper 2004; Pascual 2000; Rapoport 1997; Steiner 2003; Visser 1996), the incidence was ≤ 2.1% in any treatment arm, and overall was 0.65% (35/5346) for all doses ≥ 1 mg (including second doses and rescue medication) and formulations of zolmitriptan combined, and 0.20% (7/3428) for placebo. There was no evidence of a dose response relationship, and there were too few events to calculate relative risk or NNH.

Four studies with active comparators reported adverse event withdrawals: Geraud 2002 for zolmitriptan versus aspirin plus metoclopramide, Goadsby 2007b for zolmitriptan versus almotriptan, and Gallagher 2000 and Gruffyd‐Jones 2001 for zolmitriptan versus sumatriptan. There was no significant difference between zolmitriptan 2.5 mg or 5 mg and sumatriptan 50 mg in these two studies that treated up to six attacks.

Other withdrawals

In most studies withdrawals due to reasons other than adverse events were well documented and included protocol violations, loss on follow‐up, withdrawal of consent, lack of efficacy, and lack of qualifying attacks. However, other studies did not provide detailed information or specify withdrawals by group, and in certain cases it was unclear if withdrawal had occurred before or after taking the study medication. The number of withdrawals was not likely to affect estimates of efficacy or harm.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review included 25 randomised, double‐blind, controlled studies with 20,162 participants. Fourteen studies had only a placebo control, six had both placebo control and an active comparator, and five had an active comparator only. Active comparators were ketoprofen, sumatriptan, acetylsalicylic acid plus metoclopramide, almotriptan, telcagepant, rizatriptan, eletriptan and frovatriptan. Included studies used zolmitriptan at doses of 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 mg in an oral tablet (either standard or disintegrating) or nasal spray formulation. Most of the data were for the 2.5 mg and 5 mg doses, and for the standard oral tablet. In most studies participants treated established attacks of moderate to severe intensity, and there were insufficient data for any analysis of treatment when pain was still mild.

For all efficacy outcomes zolmitriptan was superior to placebo, and doses of 2.5 mg or more gave clinically useful NNTs for all outcomes. The remarkably consistent response between studies for the primary outcomes, as illustrated by L'Abbe plots, was not unexpected given the inclusion criteria for the studies and the well‐defined outcomes. There was a trend for lower (better) NNTs at higher doses, with significant differences between 10 mg and 5 mg oral zolmitriptan for pain‐free at two hours, and headache relief at two hours. There were no significant differences between oral zolmitriptan 5 mg and 2.5 mg for any of the primary efficacy outcomes. There was no difference between oral and nasal spray formulation at the 5 mg dose, and insufficient data to compare oral with nasal spray formulations at other doses.

For the IHS preferred outcome of pain‐free at two hours, zolmitriptan 2.5 mg, 5 mg, and 10 mg (oral formulations) compared to placebo gave NNTs of 4.9, 4.8, and 3.1 respectively. About 30% to 40% of participants were responders with zolmitriptan compared to 5% to 10% with placebo. For headache relief at two hours the NNTs were 3.2, 3.5, and 2.4, respectively (60% to 70% responders with zolmitriptan, 30% with placebo). For sustained headache relief during the 24 hours post dose the NNTs for 2.5 mg and 5 mg were about 4 and for sustained pain‐free they were 8 to 9.

Analysis of adverse events was compromised by the fact that some studies did not specify the time period over which the data were collected, and some specified time periods different from the 24‐hour period specified in the protocol. Furthermore, studies allowed use of rescue medication for inadequate response (usually after two hours), and many allowed a second dose of study medication for headache recurrence (or sometimes lack of efficacy), and did not specify whether adverse event data continued to be collected from participants who had taken additional medication. It is likely that they were, so comparisons between doses and with placebo may not be reliable. With these caveats, we chose to pool as much data as possible. More participants experienced adverse events with zolmitriptan than with placebo, and a dose response relationship was seen over the range 1 mg to 10 mg, with NNHs of 16 to 2.6. For the most part adverse events were described as of mild to moderate intensity, and self‐limiting. Serious adverse events were uncommon and only one was reported as related to a study drug, in this case aspirin plus metoclopramide.