Abstract

Background

Lay health workers (LHWs) are widely used to provide care for a broad range of health issues. Little is known, however, about the effectiveness of LHW interventions.

Objectives

To assess the effects of LHW interventions in primary and community health care on maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases.

Search methods

For the current version of this review we searched The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (including citations uploaded from the EPOC and the CCRG registers) (The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 1 Online) (searched 18 February 2009); MEDLINE, Ovid (1950 to February Week 1 2009) (searched 17 February 2009); MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid (February 13 2009) (searched 17 February 2009); EMBASE, Ovid (1980 to 2009 Week 05) (searched 18 February 2009); AMED, Ovid (1985 to February 2009) (searched 19 February 2009); British Nursing Index and Archive, Ovid (1985 to February 2009) (searched 17 February 2009); CINAHL, Ebsco 1981 to present (searched 07 February 2010); POPLINE (searched 25 February 2009); WHOLIS (searched 16 April 2009); Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index (ISI Web of Science) (1975 to present) (searched 10 August 2006 and 10 February 2010). We also searched the reference lists of all included papers and relevant reviews, and contacted study authors and researchers in the field for additional papers.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of any intervention delivered by LHWs (paid or voluntary) in primary or community health care and intended to improve maternal or child health or the management of infectious diseases. A 'lay health worker' was defined as any health worker carrying out functions related to healthcare delivery, trained in some way in the context of the intervention, and having no formal professional or paraprofessional certificate or tertiary education degree. There were no restrictions on care recipients.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data using a standard form and assessed risk of bias. Studies that compared broadly similar types of interventions were grouped together. Where feasible, the study results were combined and an overall estimate of effect obtained.

Main results

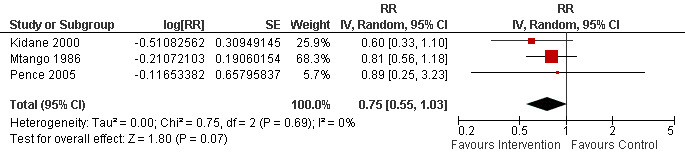

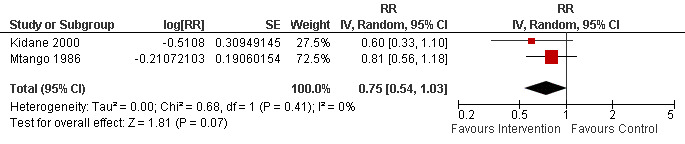

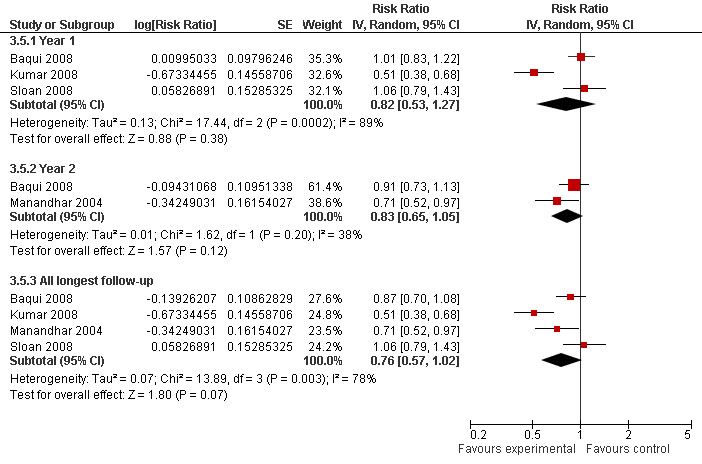

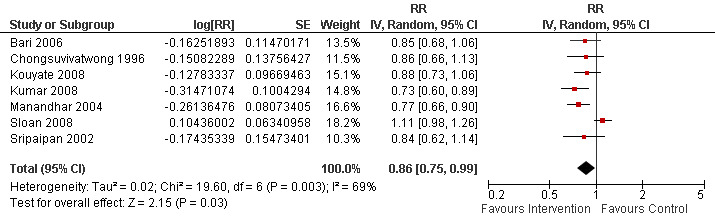

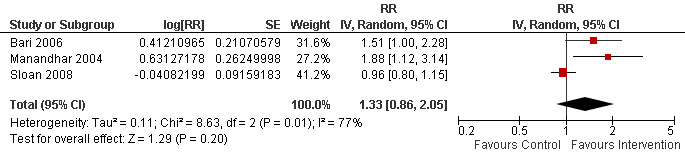

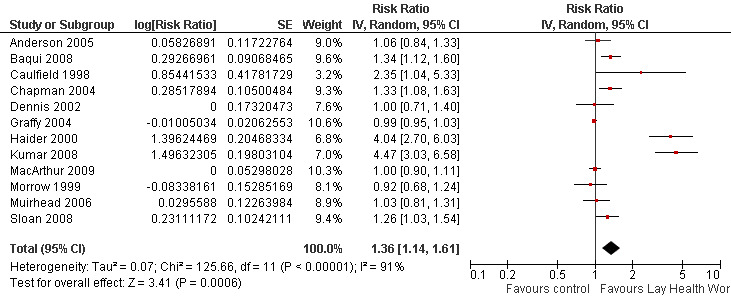

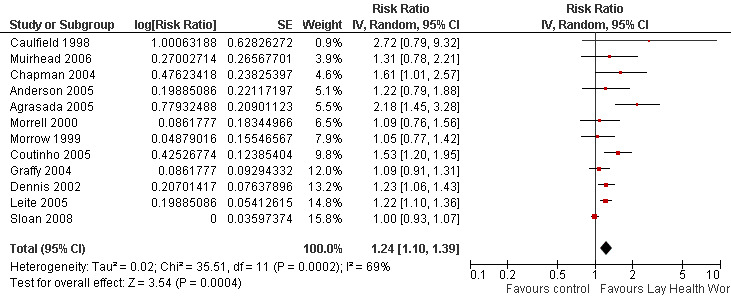

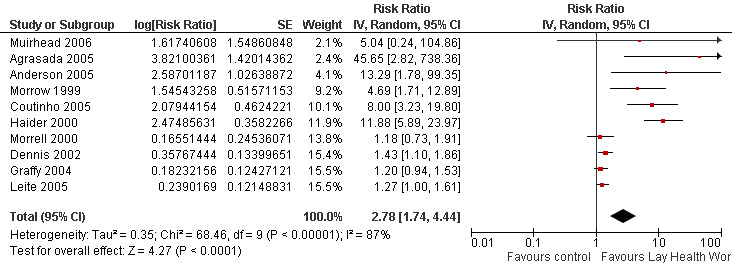

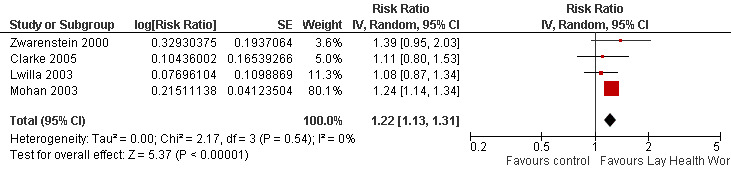

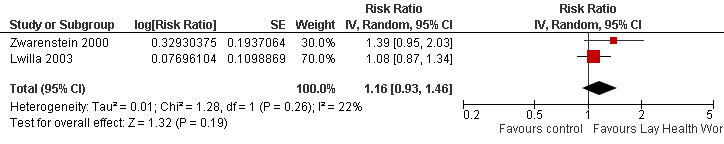

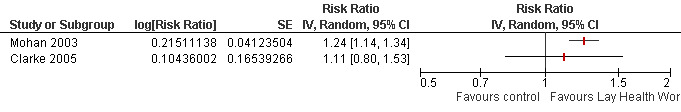

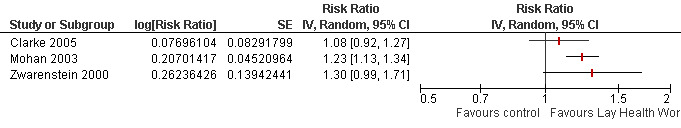

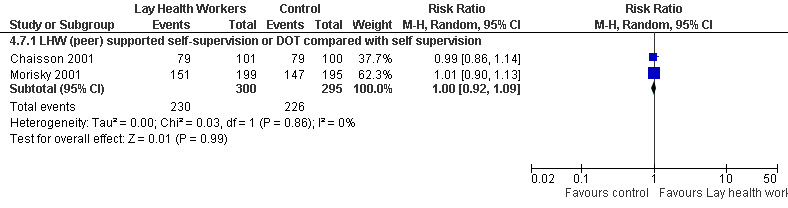

Eighty‐two studies met the inclusion criteria. These showed considerable diversity in the targeted health issue and the aims, content, and outcomes of interventions. The majority were conducted in high income countries (n = 55) but many of these focused on low income and minority populations. The diversity of included studies limited meta‐analysis to outcomes for four study groups. These analyses found evidence of moderate quality of the effectiveness of LHWs in promoting immunisation childhood uptake (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.37; P = 0.0004); promoting initiation of breastfeeding (RR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.61; P < 0.00001), any breastfeeding (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.39; P = 0.0004), and exclusive breastfeeding (RR 2.78, 95% CI 1.74 to 4.44; P <0.0001); and improving pulmonary TB cure rates (RR 1.22 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.31) P <0.0001), when compared to usual care. There was moderate quality evidence that LHW support had little or no effect on TB preventive treatment completion (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.09; P = 0.99). There was also low quality evidence that LHWs may reduce child morbidity (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.99; P = 0.03) and child (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.03; P = 0.07) and neonatal (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.02; P = 0.07) mortality, and increase the likelihood of seeking care for childhood illness (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.86 to 2.05; P = 0.20). For other health issues, the evidence is insufficient to draw conclusions regarding effectiveness, or to enable the identification of specific LHW training or intervention strategies likely to be most effective.

Authors' conclusions

LHWs provide promising benefits in promoting immunisation uptake and breastfeeding, improving TB treatment outcomes, and reducing child morbidity and mortality when compared to usual care. For other health issues, evidence is insufficient to draw conclusions about the effects of LHWs.

Keywords: Child, Preschool; Humans; Infant, Newborn; Health Promotion; Breast Feeding; Child Abuse; Child Abuse/prevention & control; Child Health Services; Child Health Services/standards; Child Mortality; Community Health Workers; Community Health Workers/standards; Home Health Aides; Immunization; Infant, Low Birth Weight; Maternal Health Services; Maternal Health Services/standards; Parent‐Child Relations; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary/prevention & control

Plain language summary

The effect of lay health workers on mother and child health and infectious diseases

A review of the effect of using lay health workers to improve mother and child health and to help people with infectious diseases was carried out by researchers in The Cochrane Collaboration. After searching for all relevant studies, they found 82 studies. Their findings are summarised below.

What is a lay health worker?

A lay health worker is a member of the community who has received some training to promote health or to carry out some healthcare services, but is not a healthcare professional. In the studies in this review, lay health workers carried out different tasks. These included giving help and advice about issues such as child health, child illnesses, and medicine taking. In some studies, lay health workers also treated people for particular health problems.

The studies took place in different settings. In many of the studies, lay health workers worked among people on low incomes in wealthy countries, or among people living in poor countries.

What the research says

The use of lay health workers, compared to usual healthcare services:

‐ probably leads to an increase in the number of women who start to breastfeed their child; who breastfeed their child at all; and who feed their child with breastmilk only;

‐ probably leads to an increase in the number of children who have their immunization schedule up to date;

‐ may lead to slightly fewer children who suffer from fever, diarrhoea and pneumonia;

‐ may lead to fewer deaths among children under five;

‐ may increase the number of parents who seek help for their sick child.

The use of lay health workers, compared to people helping themselves or going to a clinic:

‐ probably leads to an increase in the number of people with tuberculosis who are cured;

‐ probably makes little or no difference in the number of people who complete preventive treatment for tuberculosis.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. LHWs to promote immunisation uptake in children compared to usual care.

| LHWs to promote immunisation uptake in children compared to usual care | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with improving immunisation uptake among children < 2 years whose vaccination is not up to date Settings: USA(3), Ireland(1) Intervention: LHWs Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| usual care | LHWs | |||||

| Immunisation schedule up to date Interviews with mothers, record reviews Follow‐up: 6.5‐24 months | Low risk population1 | RR 1.22 (1.1 to 1.37) | 3568 (4 studies5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3,4 | ||

| 340 per 1000 | 415 per 1000 (374 to 466) | |||||

| High risk population1 | ||||||

| 560 per 1000 | 683 per 1000 (616 to 767) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Selected the next to lowest and next to highest figures to represent the control risk. 2 In Barnes 1999, only 37.5% of eligible families consented to participate, 21.2% refused to particpate, 14.3% were living out of the country or in another state. A significantly greater percentage of non‐enrolled children were covered by Medicaid insurance than enrolled children (p=0.02). The quality of evidence was downgraded by 0.5 because of these design limitations (also see footnote 3). 3 In Johnson 1993 the outcomes were recorded by a family development nurse who knew the group assignment of the mother‐child pair. 4 There is wide variation in the estimates of the included studies from no effect to a 36% relative increase. The quality of evidence was downgraded by 0.5 because of these inconsistencies. 5 Barnes 1999, Johnson 1993, LeBaron 2004, Rodewald 1999

Summary of findings 2. LHW support compared to conventional support or care for breastfeeding.

| LHW support compared to conventional support or care for breastfeeding | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with breastfeeding Settings: UK (5 studies); USA (4 studies); Bangladesh (3 studies); Brazil (2 studies); Canada; Phillipines; Mexico; India 1 Intervention: LHW support Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| usual care | LHW support | |||||

| Initiation of breastfeeding Self‐report Follow‐up: 0.3 ‐ 16 months2 | Low risk population3 | RR 1.36 (1.14 to 1.61) | 17159 (12 studies5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | ||

| 150 per 1000 | 204 per 1000 (171 to 242) | |||||

| Medium risk population3 | ||||||

| 540 per 1000 | 734 per 1000 (616 to 869) | |||||

| High risk population3 | ||||||

| 680 per 1000 | 925 per 1000 (775 to 1000) | |||||

| Any breastfeeding Self‐report Follow‐up: 0.3 ‐ 12 months6 | Low risk population7 | RR 1.24 (1.1 to 1.39) | 8104 (12 studies9) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate8 | ||

| 150 per 1000 | 186 per 1000 (165 to 208) | |||||

| Medium risk population7 | ||||||

| 320 per 1000 | 397 per 1000 (352 to 445) | |||||

| High risk population7 | ||||||

| 660 per 1000 | 818 per 1000 (726 to 917) | |||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding Self‐report Follow‐up: 3 ‐ 6 months10 | Low risk population11 | RR 2.78 (1.74 to 4.44) | 4334 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate12 | ||

| Medium risk population11 | ||||||

| 70 per 1000 | 195 per 1000 (122 to 311) | |||||

| High risk population11 | ||||||

| 250 per 1000 | 695 per 1000 (435 to 1000) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 This list includes all studies that measured breastfeeding outcomes, regardless of whether these outcomes were included in a meta‐analysis. 2 Length of follow‐up is for the study as a whole, which generally included other outcomes. Length of follow‐up for 'Initiation of breastfeeding' not always specified, but is likely to have shorter. 3 Control group risks based on baseline risks found in the included studies, specifically the next to lowest, the median and the next to highest. 4 Large inconsistencies in results. Caulfield 1998, Haider 2000 and Kumar 2008 had much higher RRs for initiation of breastfeeding, possibly explained by differences in control group rates between these 3 studies and the remaining trials. 5 Study countries: USA (3); Canada (1); Mexico (1); Bangladesh (3); UK (3); India (1). 6 Length of follow‐up is for the study as a whole, which generally included other outcomes. 7 Control group risks based on baseline risks found in the included studies, specifically the next to lowest, the median and the next to highest. 8 Moderate inconsistencies in results. Agrasada 2005, Caulfield 1998 and Coutinho 2005 measured higher rates of any breastfeeding than the other included studies. 9 Study countries: USA (3); UK (3); Brazil (2); Canada (1); Mexico (1); Bangladesh (1); Phillipines (1). 10 Length of follow‐up is for the study as a whole, which generally included other outcomes. 11 'Low' control group risk was 0%. 12 No explanation was provided.

Summary of findings 3. LHWs compared to usual care for reducing mortality and morbidity in children <5 years.

| LHWs compared to usual care for reducing mortality and morbidity in children <5 years | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with reducing mortality and morbidity in children <5 years Settings: Bangladesh (3 studies), Ethiopia, Tanzania, Nepal, Ghana, Thailand, Viet Nam, India, Burkina Faso Intervention: LHWs Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| usual care | LHWs | |||||

| Mortality among children less than 5 years Verbal autopsy Follow‐up: 1‐2 years | Study population1 | RR 0.75 (0.55 to 1.03) | 56378 (3 studies5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3,4 | ||

| 74 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (41 to 76) | |||||

| Medium risk population1 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (28 to 51) | |||||

| Morbidity e.g. fever, diarrhoea, ARI Verbal reports obtained during home visits, record reviews Follow‐up: 4‐33 months | Study population6 | RR 0.86 (0.75 to 0.99) | 17408 (7 studies9) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low7,8 | ||

| 398 per 1000 | 342 per 1000 (298 to 394) | |||||

| Low risk population6 | ||||||

| 300 per 1000 | 258 per 1000 (225 to 297) | |||||

| High risk population6 | ||||||

| 540 per 1000 | 464 per 1000 (405 to 535) | |||||

| Neonatal Mortality verbal autopsy Follow‐up: 12 ‐ 24 months | 45 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 (26 to 46) | RR 0.76 (0.57 to 1.02) | 29217 (4 studies12) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low10,11 | |

| Morbidity ‐ care seeking practice hospital record review Follow‐up: 12 ‐ 33 months | 131 per 1000 | 174 per 1000 (113 to 269) | RR 1.33 (0.86 to 2.05) | 11195 (3 studies15) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low13,14 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Median baseline control group risk among included studies. 2 In Pence 2005, only 2 clusters were randomised for this comparison and there were significant baseline imbalances. The quality of evidence was therefore downgraded for limitations in design. None of the 3 trials in this analysis adjusted adequately for clustering in the original report. After the design effect was taken into account, the CIs for the effect estimates were wider than reported in the original papers. 3 In Kidane 2000, cause of death from malaria was obtained from verbal autopsies during a period when measles and chronic wasting were also important health problems. Some of the deaths attributed to malaria may have been due to these other causes. In addition, authors verified only 1/3 of the deaths using a second assessor who was blinded. 4 The quality of evidence was downgraded for imprecision as the pooled estimate of effect included both no effect and appreciable benefit. The imprecision is related to the small number of clusters in Pence 2005 (2 clusters) and Kidane 2000 (24 clusters), giving a design effect of 267,7 and 12.4 for these two studies respectively. 5 Mtango 1986, Kidane 2000, Pence 2005. 6 Selected the next to lowest and next to highest control group risk. 7 For all studies it is not clear whether outcome assessors were blinded or not. The reliance on verbal reporting of outcomes may have introduced reporting bias. 8 There are moderate levels of heterogeneity across these studies (I2=69%, p=0.003) and the confidence intervals do not overlap for all of the studies. The reasons for this heterogeneity are not clear. 9 Chongsuvivatwong 1996, Sripaipan 2002, Manandhar 2004, Sloan 2008, Kumar 2008, Kouyate 2008, Bari 2006 10 There are high levels of heterogeneity across these studies (I2=78%, p=0.003) and the confidence intervals of the studies do not overlap. The effect sizes of the studies range from no effect to a 50% relative reduction. The reasons for this heterogeneity are not clear, but may relate to differences in the length of follow up across the studies (12‐24 months). 11 The quality of evidence was downgraded for imprecision as the pooled estimate of effect included both no effect and appreciable benefit. 12 Baqui 2008, Kumar 2008, Manandhar 2004, Sloan 2008. 13 There are high levels of heterogeneity across these studies (I2=77%, p=0.01) and the confidence intervals have minimal overlap. The reasons for this heterogeneity are not clear, but may relate to differences in the length of follow up across the studies (12‐33 months). 14 The 95% CI includes both no effect and appreciable benefit. 15 Bari 2006, Manandhar 2004, Sloan 2008.

Summary of findings 4. LHW support for tuberculosis (TB) treatment.

| LHW support for tuberculosis (TB) treatment | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with tuberculosis (TB) treatment Settings: USA (4 studies); South Africa (2 studies); Tanzania (1 study); Iraq (1 study)1 Intervention: LHW support Comparison: without LHW support | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| without LHW support | LHW support | |||||

| Cure for smear positive TB patients (new and retreatment) Sputum smear test Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 8 months2 | 526 per 1000 | 642 per 1000 (594 to 689) | RR 1.22 (1.13 to 1.31) | 1203 (4 studies4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| Completed preventive therapy with Isoniazid ‐ LHW supported self‐supervision or DOT compared with self‐supervision Follow‐up: mean 6 months5 | 766 per 1000 | 766 per 1000 (705 to 835) | RR 1.0 (0.92 to 1.09) | 595 (2 studies7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate6 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 This includes all studies that measured tuberculosis treatment outcomes, regardless of whether these studies were included in all of the meta‐analyses presented below. Details of the settings for the studies included in each meta‐analysis are listed below. 2 Length of follow varied from 6 months (Clarke 2005, Lwilla 2003, Mohan 2003) to 8 months (Zwarenstein 2000 ‐ retreatment patients). 3 Risk of bias assessed as low for Clarke 2005 and Zwarenstein 2000. Risk of bias assessed as moderate for Lwilla 2003 (not clear how randomisation sequence generated; significant loss to follow up and these losses higher in intervention group) and Mohan 2003 (insufficient information on the sequence generation process and allocation concealment; rate of loss to follow‐up unclear; methods generally described poorly). 4 Settings: South Africa (2); Tanzania (1); Iraq (1). 5 Length of follow‐up for all studies = 6 months. 6 Risk of bias assessed as moderate for both studies: Chaisson 2001 (insufficient information provided on method of allocation concealment; incomplete outcome data not addressed ‐ reasons for loss to follow up not discussed); Morisky 2001 (insufficient information on the sequence generation process, method of concealment, blinding). 7 Settings: all conducted in the USA.

Background

Lay health workers (LHWs) perform diverse functions related to healthcare delivery. While LHWs are usually provided with job‐related training, they have no formal professional or paraprofessional tertiary education and can be involved in either paid or voluntary care. The term LHW is thus necessarily broad in scope and includes, for example, community health workers, village health workers, treatment supporters, and birth attendants.

The primary healthcare approach adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) at Alma‐Ata promoted the initiation and rapid expansion of LHW programmes in low and middle income country (LMIC) settings in the 1970s, including a number of large national programmes (Walt 1990). However, the effectiveness and cost of such programmes came to be questioned in the following decade, particularly at a national level in the LMICs. Several evaluations were conducted and these indicated difficulties in the scaling up of LHW programmes, as a consequence of a range of factors. Important constraints included inadequate training and ongoing supervision; insecure funding for incentives, equipment and drugs; failure to integrate LHW initiatives with the formal health system; poor planning; and opposition from health professionals (Frankel 1992; Walt 1990). These constraints led to poor quality care and difficulties in retaining trained LHWs in many of the programmes. However, most of these evaluations were uncontrolled case studies that could not produce robust assessments of effectiveness.

The 1990s saw renewed interest in community or LHW programmes in LMICs. This was prompted by a number of factors including the growing AIDS epidemic; the resurgence of other infectious diseases; and the failure of the formal health system to provide adequate care for people with chronic illnesses (Hadley 2000; Maher 1999). The growing emphasis on decentralisation and partnership with community‐based organisations also contributed to this renewed interest. In high income country settings, a perceived need for mechanisms to deliver health care to minority communities and to support people with a wide range of health issues (Hesselink 2009; Witmer 1995) led to further growth in a wide range of LHW interventions.

More recently, the growing focus on the human resource crisis in health care in many LMICs has re‐energised debates regarding the roles that LHWs may play in extending services to 'hard to reach' groups and areas; and in substituting for health professionals for a range of tasks (Chopra 2008; WHO 2005; WHO 2006; WHO 2007). Task shifting is not a new concept, however it has been given particular prominence and urgency in the face of the demands placed on health systems in a number of settings by the increased need for treatment of HIV/AIDS (Hermann 2009; Lehmann 2009; Schneider 2008; Zachariah 2009). Within this context, it is thought that LHWs may be able to play an important role in helping to achieve the Millennium Development Goals for health, particularly for child survival and treatment of tuberculosis (TB) and HIV/AIDS (Chen 2004; Filippi 2006; Haines 2007; Lewin 2008). For example, LHWs may be one route to expanding the coverage of effective neonatal and child health interventions, such as exclusive breastfeeding and community‐based case management of pneumonia, which remains under 50% in many LMICs (Darmstadt 2005).

In contrast to earlier initiatives that tended to focus on generalist LHWs delivering a range of services within communities, more recent programmes have often been vertical in their approach. In these programmes LHWs deliver a single or a small number of focused interventions addressing a particular health issue, such as promotion of vaccination; or one aspect of treatment care, such as supporting treatment adherence for people with TB (Lehmann 2007; Schneider 2008). The growth of interest in LHW programmes, whether vertical or generalist, has, however, generally occurred in the absence of robust evidence on their effects. Given that these interventions may have adverse effects, for example if LHWs provide inappropriate care, in addition to having considerable direct and indirect costs, such evidence is needed to ensure LHWs do more good than harm.

In 2005, Lewin et al published a Cochrane systematic review examining the global evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (published up to 2001) on the effects of LHW interventions in primary and community health care (Lewin 2005). This review indicated promising benefits for LHW interventions in promoting immunization uptake; improving outcomes for selected infectious diseases; and for increasing the breastfeeding of infants in comparison with usual care. For other health issues, the review suggested that the outcomes were too diverse to allow statistical pooling. While a number of other reviews of LHW programmes have been published since, some have a focus that is wider than effectiveness (for example Lehmann 2007) while others examine the effects of LHWs for one area of intervention or health (for example Bhutta 2008).

This is an update of the 2005 systematic review, focusing on the effects of LHW interventions in improving maternal and child health (MCH) and managing infectious diseases. A second review, providing an update on the evidence of the effects of LHW interventions for chronic diseases, will be published later.

Objectives

To assess the effects of lay health worker interventions in primary and community health care on maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials

Types of participants

Types of healthcare providers

Any lay health worker (paid or voluntary) including community health workers, village health workers, birth attendants, peer counsellors, nutrition workers, home visitors.

For the purposes of this review, we defined the term lay health worker as any health worker who:

performed functions related to healthcare delivery,

was trained in some way in the context of the intervention, but

had received no formal professional or paraprofessional certificate or tertiary education degree.

Exclusions

We excluded interventions in which a healthcare function was performed as an extension to a participant's profession (for example teachers providing health promotion in schools). We defined the term profession in this study as remunerated work for which formal tertiary education was required.

We did not consider formally trained nurse aides, medical assistants, physician assistants, paramedical workers in emergency and fire services, and other self‐defined health professionals or health paraprofessionals. We also excluded trainee health professionals and trainees of any of the cadres listed above.

We also made other exclusions. Some of these exclusions were not specified in the original protocol but were developed as issues emerged from papers considered for the original review and for this review update. They were interventions:

involving patient support groups only, as these interventions were seen as different to LHW interventions in that the lay people involved meet only to provide each other with informal support rather than to provide care or services to others, and also seldom receive training in the context of the intervention;

involving teachers delivering health promotion or related activities in schools. We reasoned that this large and important system of LHWs constitutes a unique group (teachers) and setting (schools) that, due to the scale and importance, would be better addressed in a separate systematic review;

involving peer health counselling programmes in schools, in which pupils teach other pupils about health issues as part of the school curriculum. Again, we reasoned that this type of intervention contains a unique group and setting that is better suited to a separate review;

in which the LHW was a family member trained to deliver care and provide support only to members of his or her own family (that is in which LHWs did not provide some sort of care or service to others, or were unavailable to other members of the community). These interventions were assessed as qualitatively different from other LHW interventions included in this review given that parents or spouses have an established close relationship with those receiving care which could affect the process and effects of the intervention.

All of these interventions targeted 'closed' groups of clients, that is clients who, for the purposes of the intervention, are not part of the general population.

We also excluded:

LHWs in non‐primary level institutions (e.g. referral hospitals);

RCTs of interventions to train self‐management tutors who were health professionals rather than lay persons. Furthermore, RCTs that compared lay self management with other forms of management (i.e. those that did not focus on the training of tutors etc.) were also excluded as these were concerned with the effects of empowering people to manage their own health issues rather than with the effects of interventions using LHWs. These studies are the subject of another Cochrane review (Foster 2007). RCTs of interventions to train self‐management tutors who were themselves lay persons were eligible for inclusion in this review;

'Head‐to‐head' comparisons of different LHW interventions. It was felt that these should be reviewed separately as they address the question of the relative effectiveness of different types of LHW interventions rather than the question of the effects of LHWs compared to other types of intervention;

Multi‐faceted interventions that included LHWs and professionals working together and did not include a comparison group that enabled us to separately assess the effects of the LHW intervention.

Types of recipients

There were no restrictions on the types of patients or recipients for whom data were extracted.

Types of interventions

Any intervention delivered by LHWs and intended to improve maternal or child health (MCH) or the management of infectious diseases. We included interventions if the description was adequate for us to establish that it was a LHW intervention. Where such detail was unclear, we contacted study authors, whenever possible, to establish whether the personnel described were LHWs.

For the purposes of this review, a MCH or infectious diseases intervention was defined as follows.

Child health: any interventions aimed at improving the health of children aged less than five years.

Maternal health: any interventions aimed at improving reproductive health, ensuring safe motherhood, or directed at women in their role as carers for children aged less than five years.

Infectious diseases: any interventions aimed at preventing, diagnosing, or treating communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria, and diarrhoeal diseases.

We decided to include infectious diseases in this review (rather than in the sister review on chronic diseases) as many of these are highly relevant to MCH (for example diarrhoeal diseases, malaria). In addition, this review includes a number of comparisons that are of high interest to LMICs. LHW interventions to support adherence to TB and HIV treatment are also highly relevant to these settings.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies if they assessed any of the following primary and secondary outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Health behaviours, such as the type of care plan agreed, and adherence to care plans (medication, dietary advice etc.)

Healthcare outcomes as assessed by a variety of measures. These included mortality; physiological measures (e.g vitamin C levels); and participants' self reports of symptom resolution, quality of life, or patient self‐esteem

Harms or adverse effects

Secondary outcomes

Utilisation of services

Consultation processes, such as how healthcare providers interacted with healthcare users; or how often patients were managed correctly according to guidelines

Recipient satisfaction with care

Costs

Social development measures, such as the creation of support groups for the promotion of other community activities

We excluded studies which measured only recipients' knowledge, attitudes, or intentions. Such studies assessed, for example, knowledge of what constituted a 'healthy diet', or attitudes toward people with HIV/AIDS. These measures were not considered to be useful indicators of the effectiveness of LHW interventions.

Search methods for identification of studies

See: the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) methods used in reviews.

For this update, we searched the following electronic databases for primary studies:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) which includes citations uploaded from the EPOC and Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group Trial Registers (The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 1) (searched 18 February 2009);

MEDLINE, Ovid (1950 to February Week 1 2009, except August 2001 to December 2003 (see note below)) (searched 17 February 2009);

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid (February 13 2009) (searched 17 February 2009);

EMBASE, Ovid (1980 to 2009 Week 05, except August 2001 to December 2003 (see note below)) (searched 18 February 2009);

AMED, Ovid (1985 to February 2009) (searched 19 February 2009);

British Nursing Index and Archive, Ovid (1985 to February 2009) (searched 17 February 2009);

CINAHL, Ebsco (1982 to present) (searched 07 February 2010);

POPLINE (searched 25 February 2009);

WHOLIS (searched 16 April 2009).

Search strategies incorporated the methodological component of the EPOC search strategy combined with selected index terms and free text terms relating to LHWs (for example community health aides, home health aides, or voluntary workers). We translated the MEDLINE search strategy for use in the other databases using the appropriate controlled vocabulary, as applicable. We revised search strategies from the original review to reflect our improved knowledge, following the first version of this review, of terms used in the literature to describe LHW interventions. We tailored the search strategy to each database and performed a sensitivity analysis to ensure that most of the relevant studies retrieved during the first review were retrieved again. It should be noted that we did not search MEDLINE or EMBASE between August 2001 and 2004 as it was anticipated, during searches done in 2006, that all trials in these databases from that period would also appear in CENTRAL.

Full strategies for all databases are included in Appendix 1.

Other resources:

we searched the reference lists of all included papers and relevant reviews identified;

we contacted authors of relevant papers regarding any further published or unpublished work;

we searched the Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index (ISI Web of Science) from 1975 (searched 10 August 2006 for 55 studies and 10 February 2010 for 16 studies) for papers which cited the studies included in the review.

For this update, we did not search HealthStar as journal articles from this database are now indexed in MEDLINE. We did not search the Leeds Health Education Effectiveness Database as it seems to be comprised of journals that are indexed either in MEDLINE or EMBASE.

For the original review (Lewin 2005), we searched the following electronic databases:

MEDLINE (1966 to August 2001);

CENTRAL and specialised Cochrane Trial Registers (EPOC, Consumers and Communication Review Group) (to August 2001);

Science Citations (to August 2001);

EMBASE (1966 to August 2001);

CINAHL (1966 to August 2001);

Healthstar (1975 to 2000);

AMED (1966 to August 2001);

Leeds Health Education Effectiveness Database (www.hubley.co.uk).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of trials

Two review authors assessed independently the potential relevance of all titles and abstracts identified from the electronic searches. We retrieved full text copies of the articles identified as potentially relevant by either one or both review authors.

Assessment of the eligibility of interventions can vary between review authors. Therefore, each full paper was evaluated independently for inclusion by at least two review authors. When review authors disagreed, a discussion was held to obtain consensus. If no agreement was reached, a third review author was asked to make an independent assessment. Where appropriate, we contacted study authors for further information and clarification.

Reasons for the exclusion of studies at the data extraction stage are included in the table 'Characteristics of excluded studies'.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the approach recommended by The Cochrane Collaboration for assessing risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane reviews (Higgins 2008).

Two review authors assessed independently the risk of bias of all included trials. We performed further analysis of the quality of evidence related to each of the key outcomes using the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008; Higgins 2008). Using this approach, we rated the quality of the body of evidence for each key outcome as 'High', 'Moderate', 'Low', or 'Very Low'.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from the included studies using a standard form. Two review authors independently extracted all outcome data. We then checked the data against each other and, if necessary, made reference to the original paper. Any outstanding discrepancies between the two data extraction sheets were discussed by the data extractors and resolved by consensus. We tried to contact study authors to obtain any missing information.

We extracted data relating to the following from all the included studies.

Participant (LHW and recipient) information. For LHWs this included terms used to describe the LHW, selection criteria, basic education, and tasks performed. For recipients, data included the health problems or treatments received, their age and demographic details, and their cultural background.

The healthcare setting (home, primary care facility, or other); the geographic setting (rural, formal urban, or informal urban settlement) and country.

The study design and its key features (e.g., whether the allocation to groups was at the level of individual healthcare provider or at the village or suburb level).

The intervention (specific training and ongoing monitoring and support (including duration, methods, who delivered the training etc.), and the healthcare tasks performed with recipients).

The number of LHWs who were approached, trained and followed up; the number of recipients enrolled at baseline; and the number and proportion followed up.

The outcomes assessed and timing of the outcome assessment.

The results (effects), organised into eight areas (healthcare behaviours, health status and wellbeing, harms or adverse effects, consultation processes, utilisation of services, recipient satisfaction with care, social development measures and costs).

Any recipient involvement in the selection, training, and management of the LHW interventions.

Data synthesis

We grouped together studies that compared broadly similar types of interventions (n = 76), as listed below. The remaining eight studies were extremely diverse and could not be usefully grouped. We considered grouping the studies by type of LHW. However, doing this would have resulted in groups of interventions that were very dissimilar in other ways (for example, peer counsellors to promote TB treatment taking and peer counsellors to support women at risk of abuse would have been included in one group), and for which it would not have been feasible, or useful from a policy perspective, to pool findings. We therefore grouped together studies according to the type of health issue that the LHWs addressed.

1. LHW interventions to promote immunisation uptake compared with usual care.

2. LHW interventions to reduce mortality and morbidity in children under five compared with usual care. Analysis was undertaken for the following outcomes:

2.1 mortality among children under five years,

2.2 neonatal mortality,

2.3 child morbidity,

2.4 care‐seeking behaviour.

3. LHW interventions to promote breastfeeding compared with usual care. Analysis was undertaken for the following outcomes:

3.1. initiation of breastfeeding,

3.2. any breastfeeding up to 12 months post partum,

3.3. exclusive breastfeeding up to six months post partum.

4. LHW interventions to provide support to mothers of sick children compared with usual care.

5. LHW interventions to prevent or reduce child abuse compared with usual care.

6. LHW interventions to promote parent‐child interaction or health promotion compared with usual care.

7. LHW interventions to support women with a high risk of low birthweight babies or other poor outcomes in pregnancy compared with usual care.

8. LHW interventions to improve TB treatment and prophylaxis outcomes compared with other forms of adherence support.

Where feasible, we combined the results of the included studies to obtain an overall estimate of effect. This was possible for the subgroups 1 to 3 and 8 listed above. Outcome comparisons for LHW interventions to promote the uptake of breastfeeding and immunization were expressed as adherence to beneficial health behaviour. Outcomes for the subgroups including LHW interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality in children were expressed as the number of events (mortality and morbidity). Only dichotomous outcomes were included in meta‐analysis owing to the methodological complications involved in combining and interpreting studies in which different continuous outcome measures have been used. Differences in baseline variables were rare and not considered influential. We re‐analysed data on an intention‐to‐treat basis, where possible: beneficial health behaviours were analysed on a worst case basis, that is persons lost to follow up were assumed to be non‐adherent to the beneficial health behaviours. In the same way, morbidity and mortality were analysed on a best case basis, that is persons lost to follow`up were assumed to be alive and not to have experienced any morbidity events.

In two studies, Baqui 2008 (outcome: initiated breastfeeding) and Kumar 2008 (outcomes: initiated breastfeeding and reported illness in children), the results were presented as cluster means. The number of events in each groups was estimated as (N*cluster mean/100).

We made adjustment for clustering for studies that used a cluster randomised design. Where no information on the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) was reported in any of the cluster RCTs included in the analysis group, we assumed an ICC of 0.02 for this adjustment. This ICC is typical of primary and community care interventions (Campbell 2000). Where an ICC was reported among the studies in a group, this ICC was used for the adjustments to other studies. This was the case for the following analysis groups:

neonatal mortality, an ICC of 0.0012 was used from Kumar 2008;

breastfeeding, an ICC of 0.07 was used from MacArthur 2009.

We calculated log relative risks (RR) and standard errors (SE) of the log RR for both individual and cluster RCTs (unadjusted). We then adjusted the unadjusted SEs for cluster RCTs for the effect of clustering using the multiplicative factor square root of the design effect (= (1 + (mean cluster size‐1)*ICC)). We analysed the log RRs for individual RCTs and the adjusted log RRs for cluster RCTs together, using the generic inverse variance method in Review Manager 5. RRs were preferred to odds ratios because event rates were often high and, in these circumstances, odds ratios can be difficult to interpret (Altman 1998). Random‐effects model meta‐analysis was preferred because the studies were heterogeneous.

For the remaining groups of studies (LHW interventions to provide support for mothers of sick children; to prevent or reduce child abuse; to promote parent‐child interaction and health promotion; and to support women with a higher risk of low birthweight babies or other poor outcomes in pregnancy), the outcomes assessed and the settings in which the studies were conducted were very diverse. Consequently, we judged it inappropriate to combine the results of included studies quantitatively given that an overall estimate of effect would have little practical meaning. A descriptive review of these subgroups is presented in the results section below.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

During the review process, we identified several factors that might explain heterogeneity. These included: characteristics of the participants and intervention setting (child immunisation uptake); risk of bias in included studies (child mortality); and characteristics of the intervention and comparator (cure for smear positive TB patients). These were undertaken as exploratory, hypothesis generating analyses since these factors were not identified a priori and a number of potential explanatory factors were considered.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

A total of 9705 titles and abstracts (excluding duplicates), written in English and other languages, was identified. We considered 526 full text papers for inclusion in this review, 89 of which met our inclusion criteria. When combined with the RCTs included in the last review (43 in total), a total of 132 trials were eligible for inclusion in this review update.

Given the very large number of studies eligible for inclusion in this review update, a decision was taken to split the updated review into two parts. This review includes all studies relevant to maternal and child health (MCH) and infectious diseases. A separate review (forthcoming) will include the following health issues: cancer screening; chronic diseases management including diabetes, mental illness and hypertension; and studies focusing on care of the elderly. This review, therefore, includes a total of 82 studies (including 21 from the original review) that are relevant to MCH and infectious diseases.

Setting

Of the 82 studies included in this review, 55 studies (67%) were conducted in six high income countries: Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the UK, and the USA. Forty‐one of the 82 studies were conducted in the USA. Twelve studies (14.6%) were conducted in eight middle income countries (Brazil, China, India, Mexico, Philipines, Thailand, Turkey, and South Africa). Fifteen trials (18.3%) were from 10 low income countries (Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Ghana, Iraq, Jamaica, Nepal, Pakistan, Tanzania, and Vietnam). These assignments are based on the World Bank's classification of countries by gross national income per capita in 2008.

In 59 studies the intervention was delivered to patients based in their homes. Five interventions were based solely in a primary care facility (Chaisson 2001; Caulfield 1998; Merewood 2006; Olds 2002; Zaman 2008). A further eight studies involved a combination of home, primary care, and community‐based interventions. Four studies delivered the intervention mainly by telephone (Dennis 2002; Dennis 2009; Graffy 2004; Singer 1999), while one implemented the intervention through community meetings (Manandhar 2004). For five studies, other sites were used such as the workplace, churches, or homeless shelters.

Intervention characteristics

Objective of the interventions

The objectives of the interventions varied greatly and are discussed in more detail for each group of studies in the 'Effects of interventions' section below.

Mode of delivery

There was great variety in the mode of intervention delivery adopted in different studies. Some trials used very specific delivery techniques that were tailored to the individual recipient, while other intervention delivery approaches were far less specific. LHWs carried out home visits in many of the trials. In other trials, interventions were delivered through telephone calls and postcards; at community meetings; or during the recipient's visit to a healthcare centre. For more information, please see the description provided for each group of studies under 'Effects of interventions'.

Other characteristics

The involvement of recipients in the interventions was generally poorly described in the included studies. The most common form of involvement was the recruitment of people who had experienced a particular health condition to deliver the intervention to others who had the health condition. Few studies recorded that recipients or community members had been involved in the selection of LHWs. However, a number of trials recruited LHWs from participant communities, often to represent its demographic characteristics.

Participants

Lay health workers

Few studies documented the number of LHWs delivering care. Where this was reported, there were considerable differences in numbers. These ranged from two LHWs in Graham (1992) and Schuler (2000) to 150 LHWs in Chongsuvivatwong (1996).

It was difficult to group the studies in terms of either LHW selection or training because of a lack of information about these aspects in the trial reports. In some cases, individuals had been recruited for their familiarity with a target community or because of their experience of a particular health condition.

The level of education of the LHWs was often poorly reported but appears to have been very varied. Data on the duration of training received indicated a range of 0.4 to 146 days. The longest period (146 days) included six months of practical field training. The training approaches varied greatly between studies and were not described in the same level of detail in all of them. The terms used included: courses, classes, seminars, sessions, workshops, reading, discussion groups, meetings, role play, practical training, field work, video‐taped interviews, and in‐class practice.

Recipients

Different recipients were targeted in the different groups of studies. For more information, please go to the description provided for each subgroup under 'Effects of interventions'.

Outcomes

Most studies reported multiple effect measures and many did not specify a primary outcome. Relevant outcomes were extracted and were categorised for the analysis according to the results detailed below and in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables.

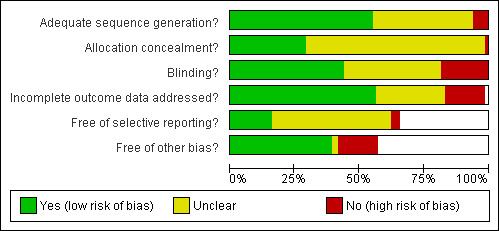

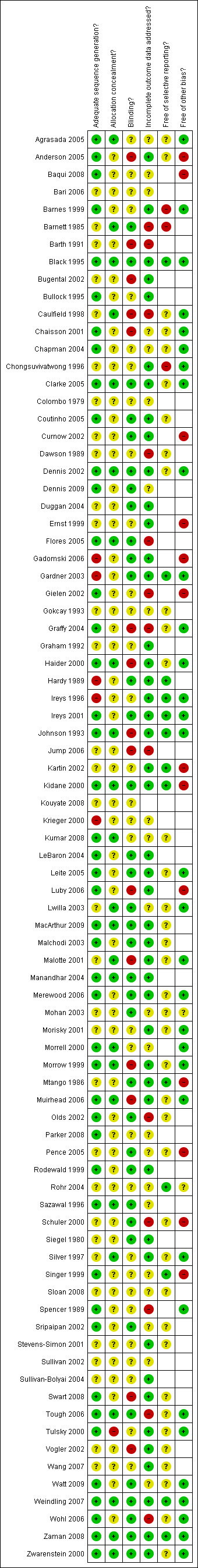

Risk of bias in included studies

Assessments of the risk of bias for included studies are shown in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table and are summarised in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The risk of bias assessments were not used for deciding which studies should be included in the meta‐analyses. Rather, these assessments were used in interpreting the results and, particularly, in assessing the quality of evidence for specific effects of LHW interventions.

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

LHWs have been employed to deliver a wide range of interventions in many healthcare settings. Attempting to group studies by intervention type is therefore problematic; a more useful approach is to focus on the intended outcome or objective of each study. In this review, trials have been arranged into groups, each containing studies that used broadly similar methods to influence a single health care outcome or a group of closely related outcomes. Meta‐analysis was performed for four of the groups. In the majority of cases the analysis included the primary study outcome. Forest plots and GRADE tables for all meta‐analyses conducted are referenced below.

For the remaining groups, we considered the outcomes too diverse to be pooled usefully. The outcomes for studies not included in the meta‐analyses are reported briefly in the text and in Table 5 (for studies that could not be assigned to groups).

1. Outcomes for studies not assigned to any group or category.

| Study, and outcomes measured | Intervention data (number of participants) | Control data | Measure of effect (95% CI) | P value | Authors’ conclusion |

| Curnow 2002 | No intervention | Intervention group – clinical + Fibre Optic Transillumination (FOTI) | P value | Authors’ conclusions | |

| 24‐month DFS caries increments of first permanent molars: Clinical D1FS | 1.104 | 0.669 | 0.006 | Children in the intervention group had significantly less caries on their newly erupted permanent teeth when compared to the control group | |

| 24‐month DFS caries increments of first permanent molars: Clinical D3FS | 0.455 | 0.192 | 0.008 | ||

| 24‐month DFS caries increments of first permanent molars: Clinical + FOTI D1FS | 1.194 | 0.808 | 0.023 | ||

| 24‐month DFS caries increments of first permanent molars: Clinical + FOTI D3FS | 0.477 | 0.205 | 0.007 | ||

| Caries increment score 12 months after eruption of 1st permanent molars: clinical D1FS | 0.736 | 0.466 | 0.0316 | ||

| Caries increment score 12 months after eruption of 1st permanent molars: clinical D3FS | 0.264 | 0.105 | 0.0404 | ||

| Caries increment score 12 months after eruption of 1st permanent molars: clinical + FOTI D1FS | 0.788 | 0.524 | 0.0474 | ||

| Caries increment score 12 months after eruption of 1st permanent molars: clinical + FOTI D3FS | 0.28 | 0.111 | 0.0348 | ||

| Ernst 1999 | Hospital recruited clients (intervention) (N=28) | Hospital recruited controls (N=25) | Measure of effect (95% CI) | P value | Authors’ conclusion |

| Endpoint domain scores on 5 point Likert scale at 3 years : (1) Utilization of alcohol/drug treatment (Mean, SD) |

1 (4.9) | ‐0.6 (5.9) | Assessment of hospital recruited clients and controls after 3 years shows that clients scored significantly higher on the summary endpoint score of overall improvement in multiple domains. | ||

| (2) Abstinence from drug and alcohol (Mean, SD) | 3.9 (3.20) | 2.6 (4.2) | |||

| (3) Use of Family Planning (Mean, SD) | 2.3 (4.8) | 2.1 (4.70) | |||

| (4) Health and wellbeing of target child (Mean, SD) | 6.1 (2.3) | 4.1 (2.8) | |||

| (5) Appropriate connection with community services (Mean, SD) | 3.8 (4.7) | 1.9 (4.2) | |||

| (6) Multiple domains of the subjects' lives (Mean, SD) | 17.10 | 10.10 | t test ‐2.11 | 0,04 | |

| Flores 2005 | Case management (intervention) (N=139) | Control (N=136) | Measure of effect (95% CI) | P value | Authors’ conclusion |

| Proportion of children that obtained Health Insurance Coverage (primary outcome) | 96 | 57 | Adj. OR 7.78 [5.2 ‐11.64] | <0.0001 | Community based case managers were more effective in obtaining coverage for uninsured children than traditional Medicaid and SCHIP outreach and enrolment |

| Proportion continously insured (%) | 78 | 30 | <0.0001 | ||

| Proportion continously uninsured (%) | 4 | 43 | <0.0001 | ||

| Mean time (no.of days) to obtain insurance (SD) | 87.5 (68) | 134.8 (102.4) | <0.009 | ||

| Parents very satisfied with process of obtaining insurance (%) | 80 | 29 | <0.0001 | ||

| Mean parental satisfaction score for obtaining insurance (Likert scale 1‐5, SD) | 1.33 (0.77) | 2.4 (1.4) | <0.0001 | ||

| Gadomski 2006 | Intervention (N=416 farms) | Control (N=429 farms) | P value | Authors’ conclusions | |

| Mean Cumulative Injury density per 100 full time equivalents among children of all ages | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.85 | Active dissemination of NAGCAT guidelines halved the incidence of NAGCAT preventable injuries among 7‐19 year olds on intervention farms in comparison to control farms. In 0 ‐ 19 years group, there was a sig increase in time span to occurence of a NAGCAT preventable injury in intervention compared to control group. | |

| Mean Cumulative incidence densities for strictly work related injuries all age groups | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.31 | ||

| Injury incidence density/100 FTEs for children less than 7 years | 1.27 | 1.36 | 0.77 | ||

| Injury incidence density/100 FTEs for children 7 ‐ 16 years | 0.5 | 0.63 | 0.96 | ||

| North American Guidelines for Childrens Agricultural Tasks (NAGCAT) ‐ preventable injury incidence densities among 7 ‐19 year olds | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.68 | ||

| All NAGCAT – related injury incidence densities among 7 – 19 year olds | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.5 | ||

| Proportion reporting setting limits on amount of time child could perform work between breaks (%) | 25 | 16 | <0.01 | ||

| Proportion providing supervision to children while they were performing work (%) | 42 | 36 | 0.06 | ||

| Proportion preventing child from doing a particular job (%) | 61 | 61 | |||

| Proportion adding roll‐over protection structure during study period (%) | 3.5 | 2,9 | 0.89 | ||

| Proportion adding or repairing a power take off | 25 | 24 | 0.76 | ||

| Mean number of safety related changes made | 1.57 | 1.39 | 0.03 | ||

| Gielen 2002 | Enhanced intervention group | Standard intervention group | P value | Authors’ conclusions | |

| Proportion with hot water temperature ≤ 48.9 oC (N=115) | 47 | 47 | NS | There were no significant differences between the standard and enhanced intervention groups in the rates at which any of the safety practices were observed at home observation. | |

| Proportion with working smoke alarms (N=114) | 81 | 84 | NS | ||

| Proportion stairs protected by gate or door (N=96) | 27 | 23 | NS | ||

| Proportion poisons kept latched or locked up (N=121) | 10 | 12 | NS | ||

| Proportion homes with ipecac syrup (N=89) | 31 | 27 | NS | ||

| Parker 2008 | Intervention (N=23) | Control (N=30) | Intervention change (95% CI) | P value | Authors’ conclusion |

| Post‐intervention FEV1 intraday variability (Mean %, SD) | 14.4 (12.1) | 17.1 (13.7) | ‐1.3 [‐5.8, 3.0] | 0.559 | There was a significant beneficial effect on lung function in daily nadir FEV1 and daily nadir PF and reduced unscheduled health care utilization for asthma in the last 3 and 12 months. |

| Post‐intervention peak flow variability (Mean %, SD) | 8.7 (8.50) | 11.6 (9.7) | ‐2.1 [‐5.0, 0.8] | 0.153 | |

| Post‐intervention daily nadir FEV1 (% predicted, SD) | 83.1 (15.7) | 75.6 (18.5) | 10.0 [0.9, 19.1] | 0.032 | |

| Post‐intervention daily nadir peak flow (% predicted, SD) | 94.1(15) | 85.1(19,2) | 8.2 [1.1, 15.2] | 0.023 | |

| Proportion needed unscheduled medical care in last 12 months at post‐intervention | 59 (N=115) | 73 (n=112) | 0.40 [0.22, 0.74] | 0.004 | |

| Proportion needing unscheduled medical care in last 3 months at post‐intervention | 45 | 56 | 0.43 [0.23, 0.80] | 0.007 | |

| Proportion with any symptom more than 2 days per week, not on controller (corticosteriod) medication at post‐intervention | 42 | 46 | 0.56 [0.29, 1.06] | 0.073 | |

| Proportion with any symptom more than 2 days per week, not on any controller medication, at post‐intervention | 32 | 37 | 0.39 [0.20, 0.73] | 0.004 | |

| Swart 2008 | Intervention data (N=189) | Control data (N=188) | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | Authors’ conclusion |

| Mean Total Injury Risk score (90) | 13.9 (0.53) | 14.2 (5.4) | ‐0.31 [‐1.8, 1.2] | 0.680 | Home visiting can effectively reduce home‐based child injury risks for burns related to unsafe practices. A non‐significant decline was noted for injuries related to electrical burns, paraffin burns and poison ingestion. |

| Mean risk score for burns, electrical (Total Risk score =20) | 1.1 (0.14) | 1.3 (0.14) | ‐0.19 [‐0.54, 0.16] | 0.294 | |

| Mean risk score for burns, paraffin (Total Risk score =20) | 3.2 (0.21) | 3.2 (0.21) | ‐0.03 [‐0.64, ‐0,57] | 0.911 | |

| Mean risk score for Burns, safety practices (Total Risk score =13) | 2.5 (0.12) | 2.9 (0.12) | ‐0.41 [‐0.76, ‐0.07] | 0.021 | |

| Mean risk score for Poison (Total Risk score =19) | 1.9 (0.20) | 2.4 (0.20) | ‐0.45 [‐1.01, 0.11] | 0.110 | |

| Mean risk score for Falls (Total Risk score =15) | 3.7 (0.24) | 3.6 (0.24) | 0.09 [‐0.60, 0.78] | 0.785 | |

| Zaman 2008 | LHW (N=52) | Usual care (N=53) | Measure of effect (95% CI) | P value | Authors’ conclusion |

| Communication skills: greets cordially (%) | 88.46 | 83.02 | OR 1.56 [0.29 – 8.32] | 0.597 | Nutrition counselling intervention resulted in (1) some improvements in LHW communication skills (2) more appropriate actions during consultations (3) improvements in child weight‐for‐age and weight‐for‐height at 180 days after the intervention, compared to usual care. |

| Communication skills: passes friendly remarks | 82.69 | 50.94 | OR 4.6 [1.32, 15.92] | 0.0160 | |

| Communication skills: pays attention to mothers | 90.38 | 84.91 | OR 1.67 [0.38, 7.34] | 0.498 | |

| Communication skills: encourages mothers to talk | 63.46 | 52.83 | OR 1.55 [0.48, 4.99] | 0.462 | |

| Communication skills: positive non‐verbal communication and body language | 94.23 | 90.57 | OR 1.7 [0.28, 10.51] | 0.563 | |

| Communication skills: asks about feeding and pays attention to reply | 50 | 24.53 | OR 3.07 [0.93] | 0.064 | |

| Communication skills: praises the mother about positive action | 36.54 | 7,55 | OR 7.5 [1.68, 29.5] | 0.008 | |

| Communication skills: recommends changes in inappropriate feeding practices | 32.69 | 3,77 | OR 12.38 [2.43, 63.25] | 0.003 | |

| Communication skills: explains why changes have to be done | 28.85 | 3,77 | OR 10.34 [2.05, 52.18] | 0.005 | |

| About feeding: asks if the child is breastfed | 50.03 | 27.27 | OR 3.15 [0.95, 10.43] | 0.060 | |

| About feeding: asks about other foods and drinks | 46.15 | 11,76 | OR 6.42 [1.37, 30.1] | 0.018 | |

| About feeding: asks size of portion | 27.45 | 5,66 | OR 6.18 [1.04, 36.6] | 0.045 | |

| About feeding: asks if changed feeding during illness | 15.56 | 9,09 | OR 2 [0.46, 8.73] | 0.353 | |

| Actions: weighs child | 57.69 | 47,17 | OR 1.52 [0.50 4,64] | 0.456 | |

| Actions: plots weight in growth chart | 36.54 | 7,95 | OR 7.05 [0.50, 4.64] | 0.034 | |

| Actions: checks current feeding against age recommended feeding | 38.46 | 5,66 | OR 10.4 [1.91, 56.8] | 0.007 | |

| Actions: checks if the mother has understood | 29.41 | 1,89 | OR 21.66 [2.6, 181.93] | 0.0046 | |

| Feeding practices: offered eggs 8 days ‐ 2 weeks | 47.68 (N=151) | 31. 95 (N=169) | OR 1.94 [1.04, 3.62] | 0.037 | |

| Feeding practices: offered chicken/beef/mutton 8 days ‐ 2 weeks | 49.67 | 31.95 | OR 2.1 [1.15, 3.83] | 0.016 | |

| Feeding practices: offered liver 8 days ‐ 2 weeks | 17.22 | 9.47 | OR 1.99 [0.89, 4.44] | 0.093 | |

| Feeding practices: added ghee/butter/oil 8 days ‐ 2 weeks | 30.46 | 24.85 | OR 1.32 [0.51, 3.42] | 0.562 | |

| Feeding practices: offered thick kitchuri 8 days ‐ 2 weeks | 61.59 | 44.97 | OR 1.96 [0.95, 4.05] | 0.068 | |

| Feeding practices: offered eggs at 180 days | 47.62 (N=126) | 26.72 (N=131) | OR 2.49 [1.03, 6.03] | 0.043 | |

| Feeding practices: offered chicken / beef / mutton at 180 days | 60.32 | 39.69 | OR 2.3 [0.996, 5.34] | 0.051 | |

| Feeding practices: offered liver at 180 days | 30.95 | 19.85 | OR 1.81 [0.79, 4.10] | 0.159 | |

| Feeding practices: added ghee/butter/oil at 180 days | 53.97 | 38.17 | OR 1.89 [0.75, 4.78] | 0.174 | |

| Feeding practices: offered thick kitchuri at 180 days | 65.87 | 44.27 | OR 2,43 [1.02, 5.76] | 0.044 | |

| Weight for age Z score ‐ 1st visit ‐ 2 weeks (Mean, SD) | ‐1.089 (1.23) | ‐1.439 (1.22) | 0.125 | ||

| Weight for age Z score ‐2nd visit ‐ 45 days (Mean, SD) | ‐1.319 (1.29) | ‐1.334 (1.19) | 0.950 | ||

| Weight for age Z score ‐ 3rd visit ‐ 180 days (Mean, SD) | ‐1.174(1.94) | ‐1.72 (1.27) | 0.012 | ||

| Height for age Z score ‐ 1st visit ‐ 2 weeks (Mean, SD) | ‐1.115 (1.36) | ‐1.407 (1.22) | 0.167 | ||

| Height for age Z score ‐2nd visit ‐ 45 days (Mean, SD) | ‐1.36 (1.29) | ‐1.575 (1.44) | 0.241 | ||

| Height for age Z score ‐ 3rd visit ‐ 180 days (Mean, SD) | ‐1.582 (1.58) | ‐1.705 (1.24) | 0.559 | ||

| Weight for height Z score ‐ 1st visit ‐ 2 weeks (Mean, SD) | ‐0.45 (1.01) | ‐0.559 (1.08) | 0.452 | ||

| Weight for height Z score ‐2nd visit ‐ 45 days (Mean, SD) | ‐0.536 (1.22) | ‐0.382 (1.08) | 0.447 | ||

| Weight for height Z score ‐ 3rd visit ‐ 180 days (Mean, SD) | ‐0.286 (1.22) | ‐0.794 (1.15) | 0.005 |

Detailed descriptions of the comparison groups for each study are available in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

LHW interventions to promote immunization uptake compared with usual care

Setting

Eight studies conducted in high and middle income countries were identified. One was conducted in China (Wang 2007), one in Ireland (Johnson 1993), one in Turkey (Gokcay 1993), and the remaining five in the USA (Barnes 1999; Colombo 1979; Krieger 2000; LeBaron 2004; Rodewald 1999). Apart from Wang 2007, conducted in a rural population, all other studies were implemented among urban communities.

Participants

Recipients: all studies were conducted among populations of low socioeconomic status. One study (Krieger 2000) was directed at an adult population (over 65 years of age). All other studies were directed at children of different age groups under five years.

LHWs: Krieger (2000) utilised peers selected from senior centres. In all other studies the LHWs were volunteers serving as outreach, village‐based workers or home visitors and recruited from the community. Information on educational background was available from three studies and indicated that the LHWs were college educated (LeBaron 2004; Rodewald 1999) or primary school graduates (Gokcay 1993). Only four studies provided specific information related to training: in Johnson (1993), LHWs were trained for four weeks on early childhood development principles, while Krieger (2000) reported training for only four hours. Both studies indicated that monitoring during implementation was provided. In Gockay (1993), LHWs were trained for three weeks on MCH, communication skills and on tasks to be undertaken during home visits. In Colombo 1979, coordinators were enrolled in a neighbouring college for education and training on communication skills, health care and education concepts over a six month period. Five studies indicated that monitoring or supervision was provided by a professional person but the methods used to monitor or evaluate delivery of the intervention were not specified.

Description of interventions

Immunization uptake was the primary goal in five of the studies. In four studies (Barnes 1999; Krieger 2000; LeBaron 2004; Rodewald 1999) LHWs were used to encourage individuals whose immunisation schedules were not up to date, or who had not received any vaccinations, to attend clinics to be vaccinated. This was done through postcards; phone calls or home visits, or both. In Wang (2007), LHWs delivered a birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine through a home visit to babies born in rural areas, using an out‐of‐cold chain delivery strategy. This intervention was compared to both hospital delivered vaccine and vaccine delivered using a prefilled injection device. In the remaining three studies (Colombo 1979; Gokcay 1993; Johnson 1993) immunization uptake was one of several goals tied to child health and development. Here, families were visited at home by the LHW and were given guidance and information about child health, including immunization, and were encouraged to get their children vaccinated at a clinic.

Results

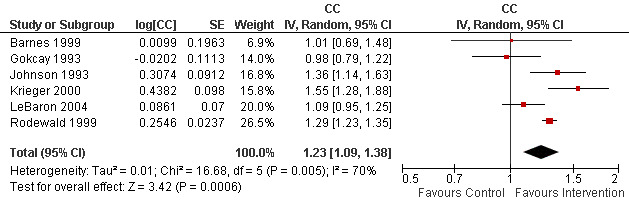

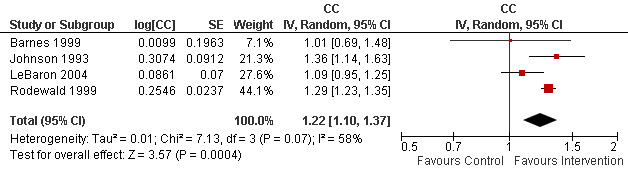

Data from six studies on the outcome 'immunisation schedule up to date' were included in a meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.2; Figure 3; Table 1). This showed evidence of moderate quality that LHWs can increase the proportion of children with immunisation schedule up to date (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.38; P = 0.0006), but the results were heterogeneous ( I2 = 70%, P = 0.005). In a post hoc analysis, we excluded Krieger (2000), a study focusing on adults, and Gokcay (1993), which had been implemented in a very different setting to the other studies (that is a middle rather than a high income country) (Analysis 1.3; Figure 4). The subsequent findings indicate that LHW‐based promotion strategies can increase immunisation uptake in children (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.37; P = 0.0004). The control group risk was 47.4% (range 30% to 72%). However, the results were still heterogeneous (I2 = 58%, P = 0.07) suggesting that LHW interventions have variable effects. No compelling explanation for this heterogeneity was identified. In addition, there is only indirect data (from high income countries and one middle income country) regarding the effects of LHW interventions to promote immunization uptake in low income countries.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LHW interventions to promote immunisation uptake in children under five compared with usual care, Outcome 2 Immunisation schedule up to date ‐ adjusted for clustering.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 LHW interventions to promote immunisation uptake in children under five compared with usual care, outcome: 1.5 Immunisation schedule up to date.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LHW interventions to promote immunisation uptake in children under five compared with usual care, Outcome 3 Immunisation schedule up to date (excl. Gökcay and Krieger).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 LHW interventions to promote immunisation uptake in children under five compared with usual care, outcome: 1.8 Immunisation schedule up to date (excl. Gökcay and Krieger).

Two studies were not included in the meta‐analysis: Colombo 1979 did not provide sufficient data while Wang 2007 was different in intent to the other included studies (see above) and therefore measured different outcomes. Results from these two studies showed LHW interventions to have positive effects on immunization outcomes. In Colombo 1979, the subgroup for which outreach workers were specially trained to focus on preventive procedures for preschool children had markedly higher use rates for preventive care, such as immunization, when compared to the control group who received only routine care. In Wang 2007, coverage of the birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine increased in all three groups. There was a statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference between each of the groups in favour of the LHW interventions.

LHW interventions to reduce mortality and morbidity in children under five years compared with usual care

Setting

Fourteen studies conducted in 11 countries were identified. One study was implemented in the USA (Jump 2006) and all of the remaining studies were undertaken in LMICs: Bangladesh (Baqui 2008; Bari 2006; Sloan 2008), Burkina Faso (Kouyate 2008), Ethiopia (Kidane 2000), Ghana (Pence 2005), India (Kumar 2008; Sazawal 1996), Nepal (Manandhar 2004), Pakistan (Luby 2006), Tanzania (Mtango 1986), Thailand (Chongsuvivatwong 1996), and Vietnam (Sripaipan 2002). Aside from Jump 2006, all were community‐level interventions among rural or urban populations.

Participants

Recipients: these interventions targeted families of low socioeconomic status with children aged zero to five years. Jump 2003 was conducted among infants in an orphanage.

LHWs: these were nominated by village health committees or leaders in two studies (Manandhar 2004; Pence 2005) and by community members in two studies (Kidane 2000; Kouyate 2008). In Baqui 2008, LHWs were selected by a partner NGO while, in Sloan 2008, they were employees of the government’s nutrition programme. The LHWs in Jump 2006 were members of the staff of an orphanage. The education level of the LHWs was generally poorly described. In Kumar 2008, the LHWs had 12 years of education or more and, in Bari 2006, they had a minimum of 10th grade education. No information was provided on the educational background of the LHWs in the other included studies. Eight studies indicated that training was provided and this ranged from two days (Chongsuvivatwong 1996) to six weeks (Pence 2005). Supervision was performed by a village committee in two studies (Pence 2005; Sripaipan 2002); by the government trainers from the disease programme in two studies (malaria control in Kidane 2000; nutrition programme and partner NGO in Sloan 2008); by the regional programme supervisor in one study (Kumar 2008); or was not specified.

Description of interventions

The main purpose of these interventions was to promote health or essential newborn care and, in some cases, to manage or treat illness, including acute respiratory infections (ARI), malaria, diarrhoea, malnutrition, and other illnesses during the neonatal period. In five of the studies, the main LHW tasks included visiting homes to educate mothers about ARI or malaria; early recognition of symptoms; first line management of fever by tepid sponging; treatment with anti‐malarials or antibiotics; and referral of severe cases to health facilities (Chongsuvivatwong 1996; Kidane 2000; Kouyate 2008; Mtango 1986; Pence 2005). In the Pence study (2005), education about immunization, hygiene and other childhood illnesses was also given and the LHWs distributed multi‐vitamins, deworming tablets and vaccines in addition to anti‐malarials and antibiotics.

In five studies, LHW promoted birth preparedness and essential newborn care using various strategies. The LHW interventions were initiated in the antenatal period in two studies (Baqui 2008; Bari 2006), and included pregnancy surveillance, vitamin supplementation and promotion of birth preparedness. In the postnatal period, LHWs identifed and referred sick neonates after providing first line treatment. In Sloan 2008, the LHW promoted community‐based kangaroo care. In contrast, in Kumar 2008 the focus was on the identification of newborn stakeholders at community level and the promotion of behaviour change for improved survival of newborns. This was undertaken through folk songs and discussions at community level gatherings. In Manandhar (2004), the LHWs facilitated meetings where local perinatal health problems were identified and local strategies formulated to promote maternal and child health.

Four studies focused on the prevention or management of diarrhoeal diseases. In Luby (2006), LHWs arranged neighbourhood meetings and provided education concerning health problems associated with hand and water contamination. LHWs provided a broad range of interventions at household level for the prevention of diarrhoea, including: bleach; hand washing; a new disinfectant for drinking water; and a new disinfectant plus hand washing. The LHWs in Sazawal 1996 managed diarrhoea and prevented malnutrition by providing zinc preparations to children with diarrhoea. Growth monitoring, nutrition education, and referral to health facilities of those who were ill or failing to gain weight were the focus of activities in Sripaipan 2002. The LHWs also conducted rehabilitation programmes and made home visits to malnourished children. In the fourth study, the LHWs were trained to provided massage therapy as part of management of diarrhoea among children staying at an orphanage (Jump 2006).

Results

Data from seven studies were included in several meta‐analyses (Table 2). Findings are discussed below for the main outcomes measured by the included studies: mortality among children less than five years, neonatal mortality, child morbidity, and care‐seeking behaviour.

Outcome 1: mortality among children less than five years