Abstract

Background

This is one of three Cochrane reviews examining the role of the telephone in HIV/AIDS services. Telephone interventions, delivered either by landline or mobile phone, may be useful in the management of people living with HIV (PLHIV) in many situations. Telephone delivered interventions have the potential to reduce costs, save time and facilitate more support for PLHIV.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of voice landline and mobile telephone delivered interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV infection.

Search methods

We searched The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, PubMed Central, EMBASE, PsycINFO, ISI Web of Science, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health, World Health Organisation’s The Global Health Library and Current Controlled Trials from 1980 to June 2011. We searched the following grey literature sources: Dissertation Abstracts International, Centre for Agriculture Bioscience International Direct Global Health database, The System for Information on Grey Literature Europe, The Healthcare Management Information Consortium database, Google Scholar, Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, International AIDS Society, AIDS Educational Global Information System and reference lists of articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐randomised controlled trials, controlled before and after studies, and interrupted time series studies comparing the effectiveness of telephone delivered interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality in persons with HIV infection versus in‐person interventions or usual care, regardless of demographic characteristics and in all settings. Both mobile and landline telephone interventions were included, but mobile phone messaging interventions were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently searched, screened, assessed study quality and extracted data. Primary outcomes were change in behaviour, healthcare uptake or clinical outcomes. Secondary outcomes were appropriateness of the mode of communication, and whether underlying factors for change were altered. Meta‐analyses, each of three studies, were performed for medication adherence and depressive symptoms. A narrative synthesis is presented for all other outcomes due to study heterogeneity.

Main results

Out of 14 717 citations, 11 RCTs met the inclusion criteria (1381 participants).

Six studies addressed outcomes relating to medication adherence, and there was some evidence from two studies that telephone interventions can improve adherence. A meta‐analysis of three studies for which there was sufficient data showed no significant benefit (SMD 0.49, 95% CI ‐1.12 to 2.11). There was some evidence from a study of young substance abusing HIV positive persons of the efficacy of telephone interventions for reducing risky sexual behaviour, while a trial of older persons found no benefit. Three RCTs addressed virologic outcomes, and there is very little evidence that telephone interventions improved virologic outcomes. Five RCTs addressed outcomes relating to depressive and psychiatric symptoms, and showed some evidence that telephone interventions can be of benefit. Three of these studies which focussed on depressive symptoms were combined in a meta‐analysis, which showed no significant benefit (SMD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.21 95% CI).

Authors' conclusions

Telephone voice interventions may have a role in improving medication adherence, reducing risky sexual behaviour, and reducing depressive and psychiatric symptoms, but current evidence is sparse, and further research is needed.

Keywords: Humans, Telephone, Age Factors, Cell Phone, Depression, Depression/therapy, HIV Infections, HIV Infections/psychology, HIV Infections/therapy, HIV Infections/virology, Medication Adherence, Mental Disorders, Mental Disorders/therapy, Morbidity, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Unsafe Sex, Unsafe Sex/prevention & control

The use of the telephone to improve the health of people with HIV infection

More than 34 million people were living with HIV in 2010, and more than 2.7 million new infections occurred in that year. Improvements in drug treatments for HIV mean that the life expectancy of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV) is now almost the same as that of non‐infected people. However, the disease is still incurable, and patients require support to cope with their chronic illness and need for lifelong medication. Interventions often require people to go for face to face consultations, but barriers to healthcare, such as lack of money, transportation problems and the stigma sometimes associated with attending a clinic for HIV treatment, can prevent people from receiving the care they need. Using the telephone to deliver care to PLHIV may overcome some of these barriers, and ultimately improve health. It may also reduce costs, save time, and reduce effort. This could allow for a greater frequency of contact with patients, and the opportunity to reach more people in need of care. Mobile phones are widely used in both developed and developing countries, making them a feasible method to deliver health interventions for PLHIV.

The aim of this review was to assess the effectiveness of using the telephone to deliver interventions to improve the health of PLHIV compared to standard care. A comprehensive search of various scientific databases and other resources found 11 relevant studies. All of the studies were performed in the United States, and so the results may not apply to other countries, particularly developing countries. Some studies were aimed at any HIV positive person in the area in which the study was carried out, and others focused on specific groups of people, such as young substance using PLHIV, or older PLHIV. There were a lot of differences in the types of telephone interventions used in each study. There was some evidence that telephone interventions can improve medication adherence, reduce risky sexual behaviour, and reduce symptoms of depression in PLHIV. However, there were also a number of studies that suggested that telephone interventions were no more effective than usual care alone. We need more studies conducted in different settings to assess the effectiveness of telephone interventions for improving the health of PLHIV.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Effects of the interventions aimed at improving medication adherence for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV infection

| Effects of the interventions aimed at improving medication adherence for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV infection | ||||||

| Patient or population: People living with HIV infection Settings: All Intervention: Voice landline and mobile telephone delivered interventions to improve medication adherence | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Effects of the interventions aimed at improving medication adherence | |||||

| ART adherence | The mean art adherence in the intervention groups was 0.49 higher (1.12 lower to 2.11 higher) | 191 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Results of the studies are inconsistent. 2 All of the included studies had fewer than 400 participants.

Summary of findings 2.

Effects of the interventions aimed at improving depressive symptoms for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV infection

| Effects of the interventions aimed at improving depressive symptoms for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV infection | ||||||

| Patient or population: People living with HIV infection Settings: All Intervention: Voice landline and mobile telephone delivered interventions to improve depressive symptoms | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Effects of the interventions aimed at improving depressive and psychiatric symptoms | |||||

| Depressive symptoms Beck Depression Inventory Score | The mean depressive symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.02 higher (0.18 lower to 0.21 higher) | 447 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 All three studies have an unclear risk of bias due to missing information. 2 Studies have wide confidence intervals.

3 All the included studies had fewer than 400 participants.

Background

This review is one of three Cochrane reviews that examine the role of the telephone in the delivery of HIV/AIDS services. The other two reviews are entitled: ‘Telephone‐delivered interventions for preventing HIV infection in HIV‐negative persons’ (Van Velthoven 2012b) and ‘Telephone communication of HIV testing results for improving knowledge of HIV infection status’ (Tudor Car 2012). The titles emerged from a preliminary systematic overview of the literature (Van Velthoven 2012a). While the preliminary systematic review focussed on PLHIV, people recently being tested for HIV, and people at risk for HIV, it was felt that the population of interest was too broadly defined as those three groups are not necessarily the same groups of people. Therefore, we decided to produce three reviews with distinct populations by which we aimed to make results more cohesive and valuable. These reviews will provide a comprehensive synthesis of the evidence of the use of voice telephone interventions in HIV/AIDS services. Studies using mobile phone text messaging were excluded, as another Cochrane review is focusing on messaging for long‐term diseases management (de Jongh 2008), and a Cochrane review of mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to anti‐retroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection has been published (Horvath 2012).

Description of the condition

HIV/AIDS contributes significantly to the global burden of disease. In 2010, 34 million people were living with HIV (WHO 2011), and this number is expected to increase significantly over the next few decades as the AIDS epidemic continues (The aids2031 Consortium 2011).

Improvements in antiretroviral therapy (ART) have greatly increased the life expectancy of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV). Life expectancy of treatment naive asymptomatic PLHIV now approaches that of non‐infected people (Van Sighem 2010). However, without a cure available, patients have to continually manage their illness, which includes the use of lifelong medication (Volberding 2010).

Adherence to ART is important, with high adherence (90‐95%) being essential for stability of viral suppression (Paterson 2000). Low adherence is related to treatment failure and can also cause drug resistance (Knobel 2001). However, many patients fail to adhere to their prescribed medication. Evidence from the United States shows that at least 10% of PLHIV reported missing one or more pills on any given day, and 30‐50% of patients reported missing pills in the past two to four weeks (Reynolds 2004). Medication side effects, complicated medication regimes and psychological factors can result in poor adherence (Singh 1999). Many studies have evaluated interventions to improve adherence to long‐term medication in those with chronic illnesses such as hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus. However, effective interventions appear to be complex and even the most effective interventions do not appear to provide great increases in adherence (Haynes 2008).

While mortality from directly AIDS‐related causes is decreasing, deaths indirectly related to AIDS such as cancer, pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease are increasing (Palella 2006). One of the side effects of prolonged ART use is an increase in cardiovascular disease risk factors such as cholesterol, lipodystrophy and insulin resistance (Mondy 2007).

PLHIV often experience discrimination, stigma and psychological distress in addition to their infection (Bravo 2010). A study reported that almost 40% of HIV positive persons living in rural areas in the United States had experienced suicidal thoughts in the past week (Heckman 2002). Psychological symptoms are linked to lower quality of life in PLHIV (Cleary 1993). The most common psychiatric co‐morbidity of HIV/AIDS is depression (Bing 2001). A meta‐analysis concluded that the frequency of a major depressive disorder was around two times higher in PLHIV compared with HIV negative participants (Ciesla 2001). However, there are many barriers to PLHIV receiving treatment for depression and psychiatric distress, including health beliefs, stigma, lack of time and transportation problems (Tobias 2007).

HIV/AIDS is also a huge burden to healthcare systems. The number of PLHIV receiving ART in low and middle‐income countries rapidly increased from only 400,000 in 2003 (WHO 2009), to 7.4 million in 2011, with a further seven million people eligible for treatment but unable to access it (WHO 2011). Healthcare systems must continue to provide acute care for people with advanced AIDS, chronic services to the increasing number of PLHIV who are maintained on ART, and preventative interventions for at risk populations (Ullrich 2011). Therefore, low cost, effective interventions are needed (Atun 2011).

Description of the intervention

Telephones are widely used both in daily life and in health care. As far back as the 1970s clinicians described the telephone as “having become as much a part of standard medical equipment as the stethoscope” (Car 2003). Telephone contacts are frequently used to extend, or substitute for traditional face to face contacts with healthcare workers (Wasson 1992; Car 2004). Clinicians have reported that they value the convenience and flexibility afforded by the telephone, as it can facilitate regular follow up and sometimes obviate the need for home visits (Car 2003). Patients have reported that they value the increased choice in the way they can receive healthcare, quicker access to care and greater convenience (Car 2004). Studies showed that patients were satisfied with using the telephone for consultation (Bunn 2005) and want to be given the opportunity to consult with their doctors by telephone (Hallam 1993).

Mobile phones have become ubiquitous with an estimated six billion users at the end of 2011 (ITU‐D 2011). Mobile phones can have advantages over landline telephones, as people often carry their mobile phone with them at all times. However, using mobile phones can pose problems, including limited privacy in certain situations, depletion of battery during a call and running out of prepaid credit (depending on who is paying). Mobile phone messaging is very popular and shows promise as a simple and cost‐effective mode of healthcare communication for HIV/AIDS services (Van Velthoven 2012c). However, the use of mobile phone messaging in HIV care may be limited by illiteracy and the short space available in a message. Mobile phone calling can overcome some of these barriers. Toll‐free numbers offer a solution for the potential costs of calling that many people living in low and middle‐income countries may not be able to afford.

Telephone consultation, either by landline or mobile phone, may be useful in the management of PLHIV in many situations. A study evaluating two HIV/AIDS clinics described three patient cases of successful telephone consultations from triage nurses to PLHIV. The patient’s complaints and symptoms were addressed and instructions by the nurse were given to deal with them (Morrison 1998).

How the intervention might work

The telephone can be used to deliver simple interventions, such as giving test results or reminding patients of appointments. It may also be used to deliver more complex interventions, such as behavioural or mental health therapy. Complex interventions can use theoretical models, such as the self‐efficacy model for HIV prevention (Fishbein 2000), the self‐regulation theory for improving medication adherence (Reynolds 2003), or the cognitive behavioural theory for depression. This may enhance knowledge, understanding and self‐efficacy and thereby change emotions and behaviour. This could encourage people to adopt healthier behaviours (e.g. reduce risky sexual behaviour, improve medication adherence, facilitate smoking cessation) or improve the uptake of healthcare (e.g. increase the proportion of healthcare appointments attended), which ultimately could improve health outcomes and survival rates.

Using telephones for consultation compared to face to face delivery of care may reduce costs, save time, reduce effort, and facilitate more support. Telephone consultations may reduce waiting times, travel time and expenses (Lattimer 1998; Mohr 2010). Telephone consultations can also be shorter than face to face consultations, which may facilitate doctors to consult with more patients within a given time (Bunn 2005). More consultations in less time could improve communication, by meeting the need for regular medical review and addressing issues of compliance and perceived lack of support for PLHIV. This is important for long‐term disease management, where the quality of physician‐patient communication can make a considerable difference to patient health outcomes (Stewart 1995).

Improving access to healthcare is a major priority for both patients and healthcare providers (McKinstry 2006). Using telephones for healthcare is especially valuable for people living in rural areas and those whose health or social circumstances make visits to healthcare providers difficult (Foster 1999; Lattimer 1998). The burden of HIV/AIDS is highest in resource‐limited settings, where there is poor infrastructure and transport. People living in these settings often face additional barriers, including limited financial means for travelling, fear of stigma and partner violence. Using telephones could overcome some of these barriers, improve access to care and strengthen communication (Lester 2006). The use of telephone interventions may also help to overcome barriers experienced by PLHIV relating to confidentiality. Individuals who fear stigma can avoid an in‐person interaction and in some cases be given the opportunity to use a pseudonym. While providing telephone care may increase access to care, it may reduce self‐screening for the client, who may only need to make a simple phone call instead of travelling to a provider. For behavioural interventions, this could influence the motivation of the patient to put effort into their treatment regime (Roffman 2007).

The effective and safe use of telephone support in healthcare depends on qualified healthcare workers delivering the intervention to avoid adverse events from occurring, such as increased out‐of hours contact and accident and emergency attendance (Bunn 2005). Health workers may be concerned about providing telephone based care and the potential risk of missing a serious condition (Hull 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

There is a large gap between theory and the empirically proven effects of eHealth applications such as telephone interventions (Black 2011). The evidence for the feasibility and effectiveness of telephone interventions in the management of PLHIV is inconclusive (Bunn 2005; Van Velthoven 2012a). Little is known about the content of telephone consultations used for different purposes (e.g. acute triage, disease management, and follow up consultations) or the quality of the advice given by telephone in comparison with face to face consulting (Car 2004). Safe and effective telephone consultations require good training of healthcare personnel (Car 2004). The key approaches for clinicians have to be defined and the skills required of them for efficient practice also need to be ascertained. Considering the potential that telephone consultation can offer to improve HIV/AIDS care, it is important to assess the effectiveness. This review intends to summarise data on how the telephone can be used for PLHIV, and will inform current and new initiatives to focus on the best interventions. We aim contribute to an evidence base for the effective and safe use of this intervention.

Objectives

Primary Objective

To assess the effectiveness of voice landline and mobile telephone delivered interventions for improving health of PLHIV.

Secondary Objective

To assess the user evaluation, costs and adverse events associated with telephone delivered interventions for PLHIV.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐randomised controlled trials (qRCTs), controlled before and after studies (CBAs) with at least two intervention and two control groups, and interrupted time series (ITS) studies with at least three time points before and after the intervention. We considered qRCTs and CBAs, because our preliminary search showed that there was a limited number of RCTs. The other study types can provide additional evidence. Including ITS studies is valuable in assessing the ongoing qualities of a new technology requiring an introduction period. We also planned to evaluate any relevant trials with economic evaluations.

Types of participants

PLHIV who receive telephone delivered consultations regardless of any demographic characteristic (e.g. age, gender, education, marital status, employment status, or income) in all settings (e.g. community settings, primary care settings, outpatient settings and hospital settings).

Types of interventions

We considered studies using a telephone for delivering the intervention. The comparison group was face to face consultation, usual care (e.g. recommended standard care for medication adherence) or other ways of delivering brief interventions for PLHIV. Outcome measures for patients who received telephone delivered interventions were compared with the outcomes of patients assigned to the usual care or control group. We only included studies where telephone delivered intervention happened between the health care provider and the PLHIV.

Studies using mobile phones for calling were included. Studies using mobile phone messaging (SMS, MMS) were excluded, as another Cochrane review is focusing on messaging for long‐term diseases management (de Jongh 2008). We excluded studies focused on smoking cessation as this is covered by two other Cochrane reviews (Stead 2006; Whittaker 2009). Studies which use telephones only as a part of their intervention were excluded when the telephone component could not be separately evaluated. Studies in which a telephone voice intervention was used in combination with mobile phone text messaging were excluded when the telephone component could not be evaluated separately. Studies using automated calls were also excluded (including those for a reminder). Studies which focused on any telephone delivered intervention for PLHIV, not only restricted to an intervention specific to the care of HIV, were excluded when the effectiveness of the telephone intervention specific to the HIV care of PLHIV could not be separately evaluated.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies which report on at least one of the following primary or secondary outcomes.

Primary outcomes

To evaluate the effectiveness of telephone delivered interventions we were interested in whether they can change behaviour, healthcare uptake and ultimately change clinical outcomes.

1. Behaviour outcomes (e.g. adherence to treatment (e.g. pill counts, electronic monitoring, medications diaries, patient self‐report, provider report, clinic and pharmacy records), reported health‐enhancing behaviours, disease coping, reported risky behaviour)

2. Healthcare uptake related outcomes (e.g. proportion of healthcare appointments attended)

3. Clinical outcomes (e.g. immunologic and virologic outcomes (clinic and pharmacy records reports of viral load, reports of immunology CD4+ cells), depressive symptoms and psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, HIV/AIDS related mortality (directly and indirectly related causes).

Secondary outcomes

To evaluate whether a telephone intervention is an appropriate mode of communication we were also interested in the following outcomes:

1. Patient evaluation outcomes (e.g. acceptability of service, patient‐reported communication with provider, ease and timeliness with which patients were able to obtain and maintain needed services, barriers to services, health service utilization)

2. Provider evaluation outcomes (e.g. readiness to use, timeliness and/or convenience, satisfaction)

3. Economic outcomes (e.g. cost‐effectiveness, cost‐benefit, resources used)

4. Adverse outcomes regarding the communication mode (e.g. lower quality of telephone consultations, increased out‐of hours contact for the provider, breach of confidentiality, misinterpretation of information)

For the working mechanism of effectiveness we were also interested in whether underlying factors for change such as knowledge and support from relatives were improved.

5. Proximal outcomes (e.g. knowledge, understanding, self‐efficacy)

6. Social outcomes (e.g. perceived support from family and friends, loneliness)

Search methods for identification of studies

We used terms specific to the telephone and HIV/AIDS to create a general search for all three reviews. We consulted a librarian and Cochrane HIV/AIDS Review Group's Trial Search Coordinator when developing the search strategy. Articles in all languages but with an English abstract, regardless of publication year were included. We included both peer‐reviewed studies and grey literature. Two reviewers independently performed the searches. The detailed search strategies for all databases searched are presented in the appendices (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9; Appendix 10; Appendix 11; Appendix 12; Appendix 13; Appendix 14; Appendix 15; Appendix 16; Appendix 17.)

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library)

MEDLINE (Ovid); 1980 ‐ June 2011.

PubMed Central (PMC)

EMBASE (Ovid); 1980 ‐ June 2011.

PsycINFO (Ovid); 1980 ‐ June 2011.

ISI Web of Science which includes: Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Science (CPCI‐S), Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED), Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI)

Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health (CINAHL); 1981‐ June 2011.

WHOs The Global Health Library (Regional indexes)

Searching other resources

We searched online trial registers for ongoing and recently completed studies (Current Controlled Trials: www.controlled‐trials.com). This database contains the following registers:

‐ Action Medical Research United Kingdom (UK) ‐ subset from ISRCTN Register

‐ Medical Research Council UK ‐ subset from ISRCTN Register

‐ NIH ClinicalTrials.gov Register (International) ‐ subset of randomised trial records

‐ NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme (HTA) UK ‐ subset from ISRCTN Register

‐ The Wellcome Trust UK ‐ subset from ISRCTN Register

‐ UK trials ‐ subset from ISRCTN Register, UK trials only.

Reference lists

We searched reference lists of studies being included in the review, relevant systematic reviews and key articles in this area (as described or referred to by experts in the field).

Grey literature

We also searched Dissertation Abstracts International and Centre for Agricultural Bioscience International Direct Global Health, the System for Information on Grey Literature and The Healthcare Management Information Consortium database . A preliminary Google Scholar search showed a large number of hits, so we scanned the first 500 results.

Conference proceedings

We searched the following conference databases:

‐ Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI)

‐ International AIDS Society (IAS)

‐ AIDS Education Global Information System (AEGIS)

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Search results were merged across databases using Endnote X4, and duplicates removed. Two groups of two authors (SG and MvV, SG and LTC) independently examined titles and abstracts according to pre‐specified inclusion criteria to determine study eligibility. Studies for which eligibility was uncertain on the basis of the title and abstract alone were examined with the full text. Study authors were contacted if the information contained in the abstract or full text was not sufficient to make a judgement. Three authors discussed which studies should finally be included (SG, MvV and LTC).

Data extraction and management

The full texts of the included studies were retrieved, and data extracted independently by three groups of two authors (SG and MvV, SG and LTC, MvV and LTC) using a standardised data extraction sheet. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Data extracted included:

Study citation

Methods: study aims, design, duration, recruitment method and setting, inclusion and exclusion criteria, control or comparison group, incentives for participation and duration of follow‐up

Participants: demographic characteristics, diagnostic criteria, location of study centre(s), intervention setting, power calculation details, number recruited/excluded/declined and number randomised/withdrawn/lost to follow‐up with reasons

Intervention: intervention content, intervention target, frequency of delivery, duration of intervention, who delivered the intervention, number of providers, training for patients and providers, initiator of the intervention, adherence, exposure, quality of delivery, participant responsiveness, mode of delivery, behaviour change theory used, implementation fidelity, program differentiation and security arrangements

Outcomes: outcomes collected, outcomes reported, outcome definition, method of assessing outcome, time points for assessment, measurements involved and adverse effects.

Results: quantitative data was collected for all relevant outcomes. Qualitative data was collected on health economics, adverse effects, acceptability to patients and providers, patient knowledge and understanding and social outcomes.

Key conclusions of the study were recorded.

Risk of bias data was collected in order to perform risk of bias assessment, as outlined below.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three groups of two authors (SG and MvV, SG and LTC, MvV and LTC) independently assessed each trial and performed assessment of risk of bias. Disagreements were be resolved by consensus.

Bias in RCTs was assessed as described by The Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2009) and EPOC group (EPOC 2002) for six domains:

1. Sequence generation; whether the study used a mechanism that ensured that the same sorts of participants were allocated to the intervention and control groups.

2. Allocation sequence concealment; whether the study made sure that those who admitted participants to the intervention and control groups did not know in which intervention the participants were randomised, before the intervention started.

3. Blinding; whether personnel and people assessing outcomes were being kept unaware of the allocation of the intervention after inclusion of participants (blinding of participants obviously is not feasible in this context).

4. Incomplete outcome data; whether the study addressed attrition, reasons for attrition and how this was handled during analysis.

5. Selective outcome reporting; whether all pre‐specified outcomes, described in the methods or the outcomes one would expect, were reported in the results.

6. Other potential biases; relevant for this review were comparability of intervention and control group characteristics at baseline, imbalance of outcome measures at baseline and protection against contamination.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Qualitative examination revealed a fairly high degree of clinical heterogeneity between the included studies in terms of: intervention characteristics; type of provider of the intervention; characteristics of participants; and context of study population and outcomes. Three studies assessing the effect of telephone delivered interventions for improving medication adherence were deemed sufficiently homogenous, and sufficient data was available, for meta‐analysis to be performed. Three studies of the effect of telephone delivered interventions to reduce depressive symptoms, as measured using the Beck Depression Inventory, were also deemed sufficiently homogenous for meta‐analysis. For all other outcomes, a narrative synthesis of findings is presented, with effect sizes calculated for outcomes where there was sufficient data. Where possible, an assessment is made on the quality, size of the effect observed and statistical significance of the studies.

Where meta‐analysis was performed, statistical heterogeneity was examined for using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2011). This statistic gives the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that can be attributed to heterogeneity rather than chance. A value of greater than 50% is considered substantial heterogeneity.Values of I2 >50% were not found, indicating that there was not substantial statistical heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

We have systematically described the included studies according to design, setting, participants, control, and outcomes. When available, we have also aimed to provide additional information such as intervention integrity (e.g. adherence, exposure, quality of delivery, participant responsiveness etc). We have grouped the included studies according to intervention type. We have presented each included study in a "Characteristics of included studies" Table and provided a risk of bias assessment and quality assessment of included studies. The excluded studies are presented in "Excluded studies" with reasons for exclusion. We have presented the effects of interventions according to the groups listed under "Types of outcome measures".

We present a summary of treatment effect by type of intervention. Analysis was performed using Review Manager. Continuous outcomes were calculated as mean difference and weighted mean difference with 95% CI. Where appropriate, data were pooled using a fixed‐effects model with standardised mean differences (SMDs) for continuous outcomes. Results for the different outcomes were analysed separately. Missing data (e.g. studies, outcomes, summary data and individuals) was sought from original investigators. The GRADE approach was used to evaluate the aggregate quality of the evidence (Higgins 2011) for the primary outcomes.

Results

Description of studies

We describe the studies in the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies Tables.

Results of the search

The joint search strategy for the three Cochrane reviews on the use of telephone delivered interventions for HIV yielded 14 717 citations. We found ten relevant studies focused on the use of telephone delivered interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV infection (Collier 2005; Heckman 2007; Kalichman 2011; Lovejoy 2011; Lucy 1994; Ransom 2008; Reynolds 2008; Rotheram‐Borus 2004; Stein 2007; Watakasol 2010) and one relevant conference proceeding (Cox 2006). We found no relevant on‐going trials.

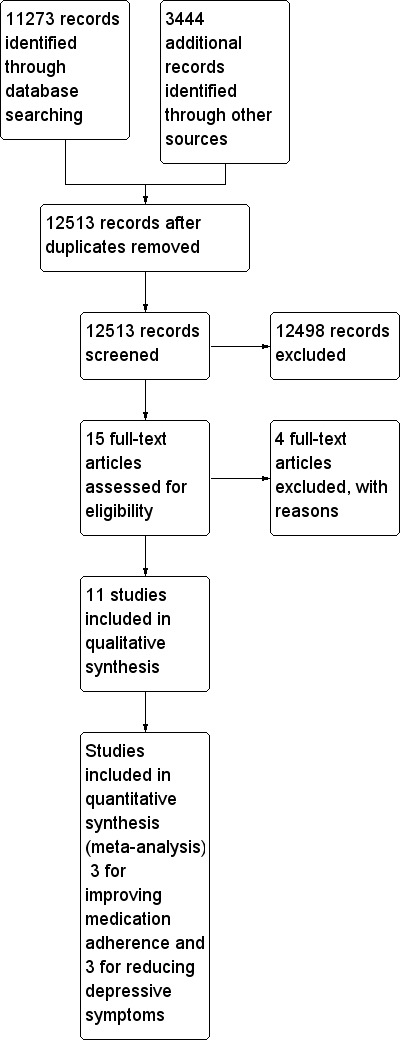

We present the search process in the form of a flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Design

We identified 11 eligible studies, all of which were RCTs.

Sample sizes

Studies varied in size. The largest (Heckman 2007) was a multicentre trial with 299 participants. The second largest study had 282 participants from 30 different study sites in three countries (United States, Italy and Puerto Rico) (Collier 2005). The number of participants in the other included multicentre trials were 175 (Rotheram‐Borus 2004), 109 (Reynolds 2008), 100 (Lovejoy 2011), 79 (Ransom 2008) and 42 (Watakasol 2010). Of the four single centre trials included, the largest had 177 participants (Stein 2007), the second 61 participants (Cox 2006), the third 40 participants (Kalichman 2011) and the smallest just 17 participants (Lucy 1994).

Setting

All studies were based in the United States, although one of the studies also had sites in Italy and Puerto Rico (Collier 2005). Three of the included studies focused on PLHIV living in rural areas (Heckman 2007; Ransom 2008; Watakasol 2010). Heckman 2007 defined rural as residence in a community with a population of 50,000 or less that was at least 20 miles from a city with 100,000 or more residents; Ransom 2008 defined rural as residence in a community with a population of 50,000 or less; and Watakasol 2010 defined rural as living in a county that met the United States Department of Agricultures definition of rural.

Participants

All participants in the included studies were HIV positive. Three studies included only participants living in rural areas (Heckman 2007; Ransom 2008; Watakasol 2010), and two studies included only participants with comorbid depression (Ransom 2008; Stein 2007). One study included only late middle‐age and older adults (Lovejoy 2011), and another only young substance users who engaged in risky sexual behaviour (Rotheram‐Borus 2004). Two studies included only participants initiating antiretroviral therapy (Collier 2005; Reynolds 2008), one of which included only those with advanced HIV infection (Collier 2005). The majority of participants were men in all the included studies, and one study included only men (Lucy 1994). One study enrolled patients with their self‐identified care giver, if they had one (Stein 2007). Further details on the characteristics of participants in the included studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Interventions

Five studies involved telephone interventions focused on improving adherence to antiretroviral medication. The intervention used by Reynolds 2008 involved structured proactive telephone calls based on self‐regulation theory.The intervention was delivered by registered nurse specialists from a central site over 16 weeks and 24‐hour support was also available via a toll free number. The intervention was designed not only to provide information about the antiretroviral regimen, but also to assist patients in recognising, self‐managing and effectively solving problems that commonly affect adherence over time. Kalichman 2011 also used an intervention based on self‐regulation theory. Participants received four unannounced telephone calls over an eight week period, in which a pill count was performed, followed by self‐regulation counselling to try to improve medication adherence. Collier 2005 gave participants in the intervention group up to 16 scripted telephone calls over 96 weeks delivered by study site staff members, mostly nurses. The calls focused on medication taking behaviour, barriers to adherence and development of strategies to increase adherence. The intervention was delivered by a masters level social worker with experience working in AIDS services. Cox 2006 was the only study to use an intervention delivered by a pharmacist. Calls were made at day four, two weeks, and then monthly for six months. The intervention involved correcting ART medication dose or frequency, suggesting methods to minimise adverse effects, arranging clinic appointments for adverse effects, assistance with medication supply and advice on medication storage requirements.Watakasol 2010 used a single session telephone administered motivational interviewing (MI) adherence improvement intervention. The intervention lasted 60 minutes and was delivered by a psychologist.

One study involved a telephone intervention focused on reducing risky sexual behaviour (Lovejoy 2011), and also used MI. The study had two intervention groups, one in which participants received one session of MI, and one in which participants received four sessions of MI. With the exception of treatment dose, the interventions were designed to be identical. The intervention was delivered by masters level psychology students. Participants sexual relationship dynamics and their readiness to always engage in condom protected sex were explored. For those in the pre‐contemplation and contemplation stages of change, providers tried to move the participant towards readiness to change. For those who felt ready to engage in condom protected sex on all occasions, providers addressed participant confidence to carry out their intentions, barriers to carrying out their intentions, and ways to overcome these barriers.

Four studies involved telephone interventions focused on reducing depressive and psychiatric symptoms. Heckman 2007 had two telephone delivered group interventions; a telephone‐delivered coping improvement intervention and a telephone‐delivered information support group. Both interventions involved eight 90 minute sessions, delivered once weekly over eight weeks. Both had six to eight participants per group, and used teleconference technology to conduct the sessions. Separate intervention groups were conducted for men who had sex with men, heterosexual men and women. The coping improvement intervention groups were co‐facilitated by two masters or PhD level clinicians, who used cognitive behavioural principles to identify stressors and their severity and develop and optimise coping skills. The information support groups were co‐facilitated by two nurse practitioners and/or social workers, who provided information and directed discussion on assigned topics (e.g. HIV symptoms management, exercise and nutrition) for the first hour of the session, and then facilitated discussion of topics generated by group members for the remaining 30 minutes. This was the only study to use a group telephone intervention. Lucy 1994 used weekly structured telephone calls lasting 20‐45 minutes, primarily aimed at providing psychosocial support but also at health monitoring, HIV education and early referrals to appropriate services, given over a 16 week period. Ransom 2008 used six 50 minutes sessions of telephone‐delivered interpersonal psychotherapy provided by a psychologist. This intervention aimed to treat depressive symptoms by improving interpersonal relations. Stein 2007 gave 12 psychoeducational telephone calls delivered by a social worker, a clinical psychologist, or a nurse, over a six month period to both HIV positive participants and their identified informal care giver. The telephone intervention was structured to provide education, and encourage problem appraisal and resolution through referral.

One study's intervention (Rotheram‐Borus 2004) addressed improving antiretroviral medication adherence, reducing risky sexual behaviour and reducing emotional distress. This was a three module intervention, with one module targeting each of the aforementioned areas. Each of the three modules was six sessions long, and each session lasted two hours. Module one aimed to improve adherence to ART; module two aimed to decrease unprotected sexual acts and substance use by identifying situations in which the participant was more likely to partake in risky behaviour and suggesting how they might modify their behaviour; and module three was aimed at reducing emotional distress by anticipating situations in which negative feelings may arise (such as anxiety or anger) and suggesting techniques to control these emotions, such as relaxation, self‐instruction and meditation. This intervention was initially planned as a group intervention, but slower than anticipated recruitment, difficulties agreeing mutually suitable times for the group sessions, and poor adherence to the intervention resulted in changing it to a one‐to‐one intervention.

Intervention integrity was only mentioned in one study (Lovejoy 2011) where therapist providing motivational interviewing were evaluated for intervention fidelity using the using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) code. All therapists were at least proficient and often competent in the majority of the domains evaluated by the MITI code, suggesting that intervention fidelity in the study was retained.

All the included studies compared a telephone intervention to a control group with no active intervention. One study compared a telephone intervention to an in‐person intervention group, and to a control group with no active intervention (Rotheram‐Borus 2004). One study compared two different telephone interventions to a control group with no active intervention (Heckman 2007). One study compared the same telephone intervention, given once or given four times, to a control group with no active intervention (Lovejoy 2011).

Outcomes

Six of the studies addressed outcomes relating to medication adherence (Collier 2005; Cox 2006; Kalichman 2011; Reynolds 2008; Rotheram‐Borus 2004; Watakasol 2010). Three studies addressed outcomes relating to immunologic and/or virologic improvements (Collier 2005; Cox 2006; Ransom 2008). Two studies addressed outcomes relating to risky sexual behaviour (Lovejoy 2011; Rotheram‐Borus 2004). Five studies addressed outcomes relating to depressive and/or psychiatric symptoms (Heckman 2007; Lucy 1994; Ransom 2008; Rotheram‐Borus 2004; Stein 2007). Two of these studies included only PLHIV who had comorbid depression (Ransom 2008; Stein 2007).

Excluded studies

We excluded four studies at the full text screening stage (Konkle‐Parker 2010; Puccio 2006; Uzma 2011; Wang 2010). Three (Konkle‐Parker 2010; Uzma 2011; Wang 2010) were excluded because they assessed the efficacy of interventions with both a telephone and a face‐to‐face component, and the telephone component could not be separately evaluated. One (Puccio 2006) study was excluded due to ineligible study design.

Risk of bias in included studies

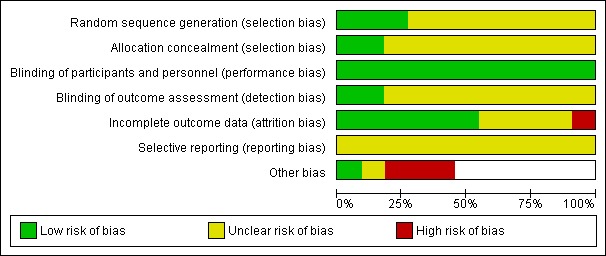

Two of the included studies (Kalichman 2011 and Lovejoy 2011) were at low risk of bias. The remaining studies (Collier 2005; Cox 2006; Heckman 2007; Lucy 1994; Ransom 2008; Reynolds 2008; Rotheram‐Borus 2004; Stein 2007; Watakasol 2010) had an unclear risk of bias due to lack of available detail about their methodology. See Figure 2 (Risk of bias graph) and Figure 3 (Risk of bias summary) for summaries of the risk of bias assessment of included studies. See Characteristics of included studies for explanation of the risk of bias assessment for each study. The criteria for assessing risk of bias are described in the Methods section.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Risk of selection bias was low in three studies (Kalichman 2011; Lovejoy 2011; Watakasol 2010) and unclear in the remaining studies, as it was not mentioned.

Blinding

We believe that blinding of participants was unlikely to be feasible in all the included studies, due to the type of interventions being used. However, we do not think that this will have affected the results, and so we judged all the included studies to be at low risk of performance bias.

Risk of detection bias was low in Kalichman 2011 and Lovejoy 2011 as both stated that blinding of outcome assessment was performed. None of the other included studies mentioned the risk of detection bias, and so was judged to be unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

Ransom 2008 was deemed at high risk of bias, as a greater number of participants (n=10) discontinued from the intervention group than the control group (n=3). Collier 2005, Heckman 2007, Kalichman 2011, Lovejoy 2011, Reynolds 2008 and Watakasol 2010 were thought to be at low risk of attrition bias, and Cox 2006, Lucy 1994, Rotheram‐Borus 2004 and Stein 2007 were unclear.

Selective reporting

Reporting bias was unclear for all the included studies, as none of the study protocols were available to us.

Other potential sources of bias

Collier 2005 was thought to be at high risk of bias for contamination. Lucy 1994 and Rotheram‐Borus 2004 were both thought to be at high risk of bias from baseline differences between the intervention and control groups.

Effects of interventions

We will describe the effects of the interventions by type of outcome.

Primary outcomes

Behaviour outcomes

Improving medication adherence

Six included studies reported on outcomes related to medication adherence (Collier 2005; Cox 2006; Kalichman 2011; Reynolds 2008; Rotheram‐Borus 2004; Watakasol 2010).

Three of the studies (Cox 2006; Watakasol 2010; Rotheram‐Borus 2004 ) found no evidence that the telephone interventions used improved medication adherence. Cox 2006 found no significant difference in the proportion of participants who were adherent to their medication between the intervention and control groups (P=0.08). Watakasol 2010 found no significant differences in dose adherence or schedule adherence between the intervention and control groups. Repeated‐measures multivariate analysis of variance revealed ‘no statistically significant ‘Condition x Time’ interaction' (P=0.81) on the combined set of outcome variables. Univariate analysis revealed that the percentage schedule adherence increased over time in both the intervention and the control groups (P=0.01). There were no significant differences between groups in readiness to change, intrinsic motivation or adherence self‐efficacy. Adherence self‐efficacy improved over time in both groups. The authors suggest that the improvements in both groups in schedule adherence and adherence self‐efficacy may be due to the use of medication diaries to collect adherence data. It is important to note that this study was performed on a rural population, and was a single session telephone intervention. Rotheram‐Borus 2004 states that ‘The proportion of ART use and adherence to ART medication were similar among intervention conditions over time.’

Results of two studies suggested that the telephone interventions used did improve adherence to medication (Kalichman 2011; Reynolds 2008). Kalichman 2011 found that adherence in the self‐regulation counselling telephone intervention group showed significant improvements in all outcomes compared to the control group. Adherence in the telephone intervention group improved from 87.4% (SD 17.7) at baseline to 94.1% (SD 9.8) at four month follow up (P<0.01). Adherence in the control group decreased from 91.0% (SD 9.7) to 87.8% (SD 17.2) at four month follow up. There was also a significant improvement in the intervention group in self‐efficacy (P <0.05) and use of adherence behavioural strategies (P <0.05). Reynolds 2008 found that mean self‐reported adherence was consistently higher in the intervention group than in the control group at each time point for assessment (99.7% versus 97.3%, P=0.032).

One study (Collier 2005) suggested that the telephone intervention used could improve medication adherence. There was no evidence of a difference in self‐reported adherence between intervention and control groups (odds ration [OR]=0.86 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 0.57‐1.29]; P=0.46). However, participants in the intervention group who received a higher proportion of telephone calls had a lower likelihood of low adherence (OR=0.46 [95% CI, 0.23‐0.90]; P=0.02). This suggests that telephone calls may be a useful tool in improving adherence, but that the intensity of the intervention may need to be greater than that used in this study, or that it is only beneficial to particular patient populations.

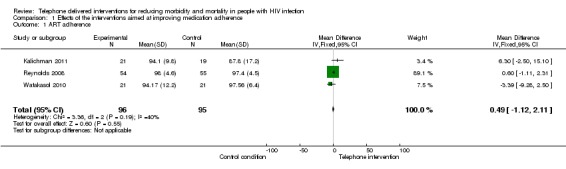

A meta‐analysis of the three studies for which there was sufficient data (Kalichman 2011; Reynolds 2008; Watakasol 2010) showed no significant difference between telephone delivered intervention and control (SMD 0.49, 95% CI ‐1.12,2.11) (Analysis 1.1, Figure 4). The quality of evidence for this outcome was deemed to be low (Table 1).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Effects of the interventions aimed at improving medication adherence, Outcome 1 ART adherence.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Effects of the interventions for improving medication adherence, outcome: 1.1 ART adherence.

There is some weak evidence that telephone interventions may be able to improve medication adherence in PLHIV. It is not clear what type of intervention, if any, is most effective, the frequency of intervention delivery required to improve adherence, or the target population(s) that are most likely to benefit.

Reducing risky sexual behaviour

Two studies reported on outcomes relating to risky sexual behaviour (Lovejoy 2011; Rotheram‐Borus 2004). Both studies measured the proportion of protected sexual acts.

One study of young drug users living with HIV (age 16‐29, had used illicit drugs at least five times in the last three months) (Rotheram‐Borus 2004) had a telephone intervention group, an in‐person intervention group, and a control group. No significant difference was found in the proportion of protected sexual acts between the telephone intervention group and the control group over time. Those in the in‐person group had a significantly higher proportion of protected sexual acts compared to participants in the telephone group (P<0.01). No significant differences were found between any groups for number of sexual partners, disclosure of serostatus to partners, or any drug use related outcomes.

A second study of late middle‐aged and older adults (age 45‐66) (Lovejoy 2011) had a one session telephone intervention group, a four session telephone intervention group, and a control group. There was no significant difference in the mean number of condom protected acts between the control group and the one session intervention group at three months (OR=0.81 [0.47‐1.41]) or six months (OR=0.61 [0.35‐1.09]). The control group had approximately three times as many unprotected sexual acts as the four session intervention group at three months (OR=3.24, 95% CI [1.79‐5.85]) and six months (OR=2.70 [1.45‐5.00]). There was no difference in the proportion of participants who were in an action stage for always using protection during anal and/or vaginal intercourse between the one session intervention group and the control group at three months (OR=2.69 [0.88‐8.27]) or six months (OR=1.87 [0.66‐5.30]). Participants in the four session intervention group were three times as likely to be in the action stage for always using protection at three months (OR=3.15 [1.02–9.72]), but this relationship was no longer significant at six months (OR=2.23 [0.78–6.40]).

Effect sizes were not estimable due to missing data. There is some evidence that telephone interventions may be able to reduce risky sexual behaviour in a middle‐aged and older adult population.

Healthcare uptake related outcomes

Healthcare uptake related outcomes (e.g. proportion of healthcare appointments attended, proportion of patients receiving test results) were not measured in any of the included studies.

Clinical outcomes

The clinical outcomes reported in the included studies can be divided into immunologic or virologic related outcomes, and psychiatric or depressive symptom related outcomes.

Immunologic and virologic outcomes

Three of the included studies addressed immunologic and/or virologic outcomes (Collier 2005; Cox 2006; Reynolds 2008). The telephone interventions had no statistically significant effects on time to virologic failure in Collier 2005 and Reynolds 2008. Only one of four immunologic and virologic measures used by Cox 2006 showed a statistically significant effect of the telephone intervention.

In one trial (Collier 2005) 37% (n=52) of participants in the usual care group had virologic failure, compared to 32% (n=45) in the intervention group. There was no statistically significant difference in time to virologic failure between the two groups (P=0.32).

In a second trial (Reynolds 2008) a Kaplan‐Meier survival curve for the intervention group remained above the control group from weeks 20 to 64, suggesting a lower risk of regimen failure. However, being in the intervention group was not a statistically significant predictor of virologic failure (P=0.21, 95% CI: 0.38 to 1.23)

In a third trial (Cox 2006) the following were measured: change in CD4 lymphocyte count; log change in HIV RNA copies/mL; proportion of participants with HIV RNA <50 copies/mL at the end of follow up; and percentage of patients with HIV RNA >50 copies/mL over time. A significant difference was found only in the percentage of participants with <50 HIV RNA copies at the end of follow up (P=0.03). Average CD4 count for the intervention group was 67 cells/mm3, and 47 cells/mm3 in the control group (P=0.35). Log HIV RNA was ‐3.3 copies/mL in the control group, and ‐3.4 copies/mL in the intervention group (P=0.93).

Effect sizes were not estimable due to missing data. There was little evidence that telephone interventions used in these studies had any affect on immunologic and virologic outcomes.

Depressive and psychiatric symptoms

Six studies reported outcomes related to depressive and/or psychiatric symptoms (Lucy 1994; Ransom 2008; Heckman 2007; Stein 2007; Rotheram‐Borus 2004; Watakasol 2010).

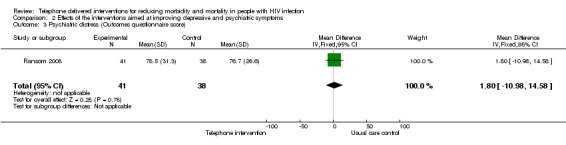

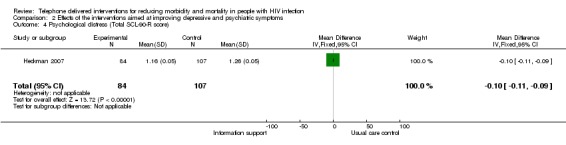

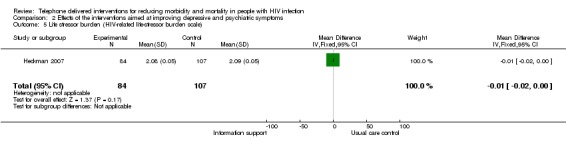

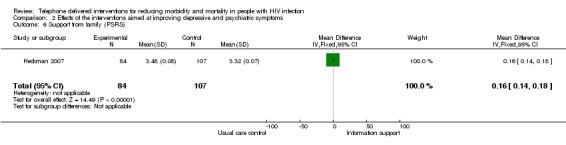

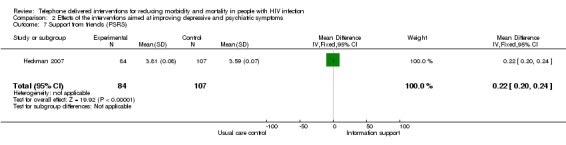

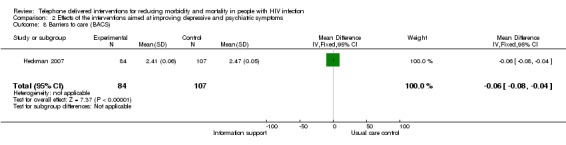

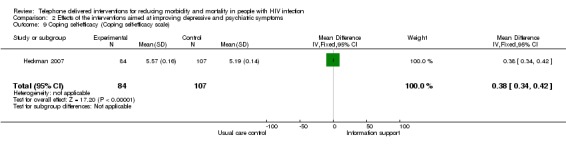

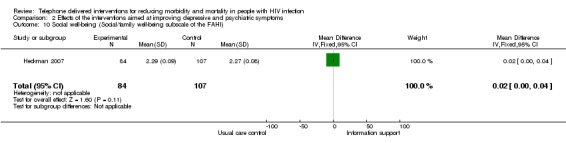

Three studies reporting depressive symptoms using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Heckman 2007; Ransom 2008; Stein 2007) were deemed to be sufficiently heterogeneous to be combined into a meta‐analysis, which showed no significant difference between telephone delivered intervention and control (SMD 0.2, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.21, Analysis 2.1, Figure 5).The quality of this evidence was judged to be low (Table 2). Heckman 2007 had two telephone intervention groups. One was an eight session Information Support Group Intervention, and the other was an eight session Coping Improvement Group Intervention. These were compared to a control group, which received usual care. Participants in the Information Support telephone intervention group reported receiving significantly more support from friends than participants in the control group at four month follow‐up (P<0.04) and eight month follow up (P<0.05) and fewer barriers to care (P<0.05). Ransom 2008 assessed depressive symptoms, psychiatric symptoms, social support and loneliness using the BDI, the Outcomes Quesionnaire (OQ), the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale and the Provision of Social Relations Scale (PSRS) respectively. Participants in the teletherapy group reported significant reductions in BDI scores from pre intervention (28.7, SD 11.2) to postintervention (23.5, SD 12.5) (mean change score=5.2). ANOVA of BDI scores found a significant time x condition interaction (P <0.05). Those in the teletherapy group had greater decreases in Outcomes Questionnaire score from pre‐intervention (87.0, SD 24.0) to postintervention (78.5, SD 31.1) (mean change score=1.5) and ANOVA conducted using total scores on the Outcomes Questionnaire found a significant time x condition interaction (P<0.05). The only information provided for results of the University of California Los Angeles Loneliness scale and Provision of Social Relations Scale was: 'No hypothesized condition × time interactions were found for the UCLA Loneliness Scale or the PSRS.' Stein 2007 assessed change in depressive symptoms; change in depression severity category; percentage of participants with a 50% or greater decrease in depressive symptoms; and whether the patient went into remission for their depression or not. All of these were measured using the BDI. Results showed that at 6 months there was no significant difference between groups for depression outcomes, and the study authors concluded that the psycho‐educational telephone support intervention did not reduce depressive symptoms for HIV patients more than an assessment only control condition.

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Effects of the interventions aimed at improving depressive and psychiatric symptoms, Outcome 1 Depressive symptoms (BDI score).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Effects of the interventions aimed at improving depressive and psychiatric symptoms, outcome: 2.1 Depressive symptoms (BDI score).

Rotheram‐Borus 2004 focussed on a young substance abusing population who participated in risky sexual behaviour, and used a different tool for measuring depressive/psychiatric symptoms, the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), which assesses global severity of mental health symptoms. At 15 months, log emotional distress was 0.8 in the telephone group, 0.9 in the in‐person group, and 0.9 in the control group. The study authors stated that ‘Logs of the overall score for emotional distress on the BSI were similar between intervention conditions over time.’ Effect size was not estimable due to missing data. Lucy 1994 measured reduction in psychiatric distress using the General Severity Index of the BSI. Change in General Severity Index was ‐5.83 (SD 4.97) in the intervention group and 0.93 (SD 5.82) in the control group (P<0.05), meaning there was a significant decline in psychological distress in the intervention group as compared to the control group. However, there was no significant difference in total GSI score between groups at the end of the study period (SMD ‐6.53, 95% CI 11.71 to ‐1.35, (Analysis 2.2).

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Effects of the interventions aimed at improving depressive and psychiatric symptoms, Outcome 2 Psychiatric distress (General Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Index).

A further study (Watakasol 2010) assessed depression using the BDI. However, they measured it only as an adherence related variable, to use when conducting explanatory analysis. Their intervention was aimed at improving adherence, not depressive symptoms, so they did not expect or observe any change in depressive symptoms. As the intervention did not aim to reduce depressive symptoms it was not included in the meta‐analysis.

There is some weak evidence of low quality for the use of voice landline and mobile telephone delivered interventions for reducing depressive and psychiatric symptoms in PLHIV.

Secondary outcomes

Very few studies addressed our secondary outcomes. Patient and provider evaluation outcomes, proximal outcomes and social outcomes were not addressed in any of the included studies. Economic outcomes were briefly mentioned in Kalichman 2011, which stated that the resources used for the telephone intervention mirror those typically available in routine clinical services, but no further analysis of cost‐effectiveness was performed. Rotheram‐Borus 2004 was the only study to give details of the costings. The study authors stated ‘The total cost of the in‐person intervention for the three modules was $3500 per participant (approximately $1167 per module), which was higher than the cost of the $2692 per participant for the telephone intervention (approximately $897 per module). The excess cost of travelling time and expenses for in‐person sessions accounted for this difference. Personnel counted for most of the total costs: 65% for in‐person sessions and 60% for telephone sessions. Overhead costs averaged 25% and material and instrumental costs averaged 12% of total costs across intervention conditions.' Adverse outcomes were very briefly mentioned by Lovejoy 2011, which states ‘No adverse outcomes were reported during the clinical trial’. They were not mentioned in any of the other included studies.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The aim of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness of telephone delivered interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV infection. This is one of three Cochrane reviews examining the role of the telephone in HIV/AIDS services. Eleven eligible studies were identified and included in this review.

Evidence for whether telephone interventions can reduce risky sexual behaviour in people living with HIV is limited, with only two included studies with outcomes related to risky sexual behaviour. The studies had very different participant populations (late middle‐age and older PLHIV Lovejoy 2011 versus young substance using PLWA Rotheram‐Borus 2004). In the first study (Lovejoy 2011), a significant reduction in outcomes related to risky sexual behaviour was seen only in the group receiving a four‐session intervention. There was no difference in outcomes between those receiving a one session intervention, and those in the control group. The second study (Rotheram‐Borus 2004) found no significant differences in outcomes relating to risky sexual behaviour between those receiving an 18‐session telephone intervention, and those in the control group. Differences in the results of the study may be related to the very different study populations.

There was some evidence that telephone interventions can improve medication adherence. Six studies reported on outcomes related to adherence. Three of the studies (Cox 2006; Watakasol 2010; Rotheram‐Borus 2004) reported no significant difference between participants in the telephone intervention group and those in the control group. Two studies (Kalichman 2011; Reynolds 2008) found a significant difference between the telephone intervention group and the control group for adherence related outcomes. One study (Collier 2005) was inconclusive, with some suggestion that the telephone intervention used could improve medication adherence. There was no evidence of a difference in self‐reported adherence between intervention and control groups, but participants in the intervention group who received a higher proportion of telephone calls had a lower likelihood of low adherence, suggesting that telephone calls may be a useful tool in improving adherence. Only three of the six included studies had sufficient data to include in a meta‐analysis (Kalichman 2011; Reynolds 2008; Watakasol 2010) and this showed that the telephone interventions had no significant effect on ART adherence at the end of the studies follow‐up periods.

There was very little evidence that telephone interventions can improve immunologic and virologic outcomes. Three of the included studies addressed immunologic and/or virologic outcomes (Collier 2005; Cox 2006; Reynolds 2008). The telephone interventions had no statistically significant effects on time to virologic failure in Collier 2005 and Reynolds 2008. Only one of four immunologic and virologic measures used by Cox 2006 showed a statistically significant effect of the telephone intervention.

There was some evidence that telephone interventions can reduce depressive and/or psychiatric symptoms. Six studies reported outcomes related to depressive and/or psychiatric symptoms (Lucy 1994; Ransom 2008; Heckman 2007; Stein 2007; Rotheram‐Borus 2004; Watakasol 2010). Two of the studies (Rotheram‐Borus 2004 and Stein 2007) found no evidence that a telephone intervention can reduce depressive and/or psychiatric symptoms in PLWA. Three studies (Heckman 2007; Lucy 1994; Ransom 2008) found evidence that telephone interventions can reduce psychiatric symptoms in PLHIV. A further study (Watakasol 2010) assessed depression using the BDI, but only as an adherence related variable to use when conducting explanatory analysis, and there was no expectation or observation of an improvement in depressive symptoms, as the intervention used was not targeted at reducing depressive symptoms. A meta‐analysis of three studies (Heckman 2007; Ransom 2008; Stein 2007) found no significant effect of the telephone intervention compared to the control group at the end of the studies follow‐up periods.

None of the eligible studies provided any information about healthcare uptake related outcomes, patient or providers acceptability of telephone delivered interventions, proximal outcomes or social outcomes. Information on cost‐effectiveness and adverse events was sparse.

Whilst the interventions were very heterogeneous, there were some important commonalities that may suggest features that demonstrate or lack effectiveness. The characteristics of the included participants appears to be potentially important to the efficacy of an intervention. The two studies focusing on risky sexual behaviour (Lovejoy 2011 and Rotheram‐Borus 2004) had conflicting results but included very different populations. Lovejoy 2011 included middle aged and older adults, while Rotheram‐Borus 2004 included young substance users who display risky sexual behaviour. In the studies focusing on depressive and psychiatric symptoms (Heckman 2007; Lucy 1994; Ransom 2008; Rotheram‐Borus 2004; Stein 2007), those in which there was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups focused on specific populations. As previously mentioned, Rotheram‐Borus 2004 included young substance users who display risky sexual behaviour, while Stein 2007 included only those living in rural areas. Intervention intensity also appears to be important. Lovejoy 2011 found a significant reduction in risky sexual behaviour in participants randomised to a 4 session intervention compared to control, but no significant difference between those randomised to a 1 session intervention and control. The single session intervention used by Watakasol 2010 also appeared ineffective. Collier 2005 found no evidence of a difference in self‐reported adherence between intervention and control, but found that participants in the intervention group who received a higher proportion of telephone calls had a lower likelihood of low adherence. This perhaps suggests that greater intensity of intervention is beneficial, or that only a particular population benefited from the intervention.However, with such a small number of included studies, and heterogeneity of interventions, participants and outcomes, identifying components of interventions that demonstrated or lacked effectiveness is challenging.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We performed a thorough search of an extensive range of databases and considered as eligible all experimental study designs accepted by The Cochrane Collaboration. We found only 11 eligible studies. The heterogeneity of studies in terms of study population, interventions, and outcomes is fairly high, resulting in low comparability.

All the eligible studies were performed in the United States, with one study (Collier 2005) also having study sites in Italy and Puerto Rico. The applicability of these results to other settings, particularly in low and middle‐income countries with a high burden of HIV infection is unclear. None of the eligible studies provided any information about healthcare uptake related outcomes, patients' or providers' acceptability of telephone delivered interventions, proximal outcomes or social outcomes. Information on cost‐effectiveness and adverse events was extremely limited.

Rapidly rising mobile phone use in developed and developing countries (ITU‐D 2011) at least theoretically provides a great opportunity for improvement of health and healthcare in resource‐limited settings (Lester 2006). Technology has the potential to be highly beneficial in reducing morbidity and mortality in PLHIV, given the high prevalence and poor treatment outcomes of HIV infection in developing countries. However, the existing evidence offers insufficient information on the efficacy of telephone interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV infection, either in developed or developing countries.

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of evidence included in this systematic review is relatively poor. Two of the included studies (Kalichman 2011 and Lovejoy 2011) were at low risk of bias. The remaining studies (Collier 2005; Cox 2006; Heckman 2007; Lucy 1994; Ransom 2008; Reynolds 2008; Rotheram‐Borus 2004; Stein 2007; Watakasol 2010), however, had an unclear risk of bias due to lack of available detail about their methodology.

Potential biases in the review process

This review has a number of strengths. We rigorously followed The Cochrane Collaboration methodology, performed a comprehensive search and included all Cochrane accepted experimental study designs. We believe it is unlikely that we missed any relevant study.

Nine out of 11 included studies were at unclear risk of bias (Collier 2005; Cox 2006; Heckman 2007; Lucy 1994; Ransom 2008; Reynolds 2008; Rotheram‐Borus 2004; Stein 2007; Watakasol 2010) due to lack of available detail about the methodology even after we had contacted the authors. It is possible that if we had sufficient information to properly evaluate the risk of bias in these studies that it may have been high.

The heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of participants, interventions and outcomes meant we were unable to pool the studies in a meta‐analysis for all outcomes. Our narrative synthesis uses the study as the unit of analysis, which may introduce reporting bias. All the included studies were conducted in the United States (although Collier 2005 also had sites in Puerto Rico and Italy), perhaps limiting generalisability.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The studies included in this review suggest that voice telephone interventions may reduce morbidity and mortality in PLHIV in the USA by improving medication adherence, reducing risky sexual behaviour, and reducing the burden of depressive and psychiatric symptoms. However, the evidence is inconsistent and sparse. The evidence for the use of mobile phone text messaging for improving adherence to ART in developing countries is more conclusive. A Cochrane review evaluating the use of mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to ART in PLHIV (Horvath 2012) included two studies, both of which were RCTs. Meta‐analysis of both trials found that weekly text messaging was associated with a lower risk of non‐adherence (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.89). One trial found that weekly text messaging was associated with non‐occurrence of virologic failure at 12 months (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.99). A systematic review of the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions to increase ART adherence in PLHIV in sub‐Saharan Africa suggested that a variety of interventions, including mobile phone text messaging, can effectively increase adherence (Barnighausen 2011).

There is also high quality evidence for the use of telephone‐administered psychotherapy for patients with depression, a common comorbidity in PLHIV. A meta‐analysis of patients with depression, some of whom were PLHIV and some of whom had other health problems or depression alone, showed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms for patients enrolled in telephone‐administered psychotherapy as compared to control conditions (d=0.26, 95% CI = 0.14‐0.39, P<0.0001) (Mohr 2008). Attrition rates were also considerably lower in participants receiving telephone interventions.

There is also evidence suggesting that interactive voice response systems may be effective. Tucker 2012 assessed the efficacy of using an interactive voice response system for PLHIV to self‐monitor HIV risk behaviours daily. Results showed that this intervention was able to assess and reduce risky behaviour in rural PLHIV. A study of PLHIV who use non‐injection drugs by Aharonovich 2012 aimed to extend brief motivational interviewing (MI) delivered in person by using a HealthCall intervention in addition. Participants were randomised to receive either MI alone, or MI plus HealthCall. Those who received HealthCall were asked to call a specified number daily for 30 days, where they answered a short set of pre‐recorded questions about their drug use on the previous day. The information collected was used to provide personalised feedback about their drug use. Results suggested that HealthCall was a feasible and acceptable method of extending patient involvement in a brief intervention.

Authors' conclusions

The included studies show inconsistent evidence for all types of outcomes. There is some evidence that voice telephone interventions can reduce morbidity and mortality in people with HIV infection in the United States, by improving medication adherence, reducing risky sexual behaviour, and reducing the burden of psychiatric symptoms. However, current evidence is scarce. We cannot currently recommend the use of voice telephone interventions of reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV infection in practice.