Abstract

Background:

There is a need for a brief, open access, self-report medication adherence scale that overcomes challenges of existing adherence tools, is associated with incident cardiovascular disease (CVD), and identifies low ‘implementation’ adherers to antihypertensive medications to facilitate blood pressure (BP) management.

Methods and Results:

Antihypertensive medication adherence was assessed in a cohort of 1,532 older hypertensive adults without prior CVD using the self-report adherence scale (K-Wood-MAS-4), a hybrid tool developed to predict pharmacy refill and which captures four domains of adherence behavior: self-efficacy, physical function, intentional medication-taking, and forgetfulness. The 4-item scale categorized participants as low and high adherers using scores ≥1 and <1, respectively. Participants were followed after K-Wood-MAS-4 assessment to identify incident CVD events (stroke, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or CVD death). The prevalence of low adherence was 38.7%. During a median follow up of 2.8 years (maximum 3.8 years), 136 (8.9%) participants had an incident CVD event; 12.8% and 6.4% in low and high adherers, respectively. The adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) for incident CVD associated with low versus high adherence was 2.29 (95% CI: 1.61,3.26). Results were similar when stratified by age [<75 years – aHR 3.53 (95% CI: 1.65, 7.56); ≥75 years – aHR 1.98 (95% CI: 1.32, 2.97)], sex [women – aHR 1.90 (95% CI: 1.16, 3.12); men – aHR 2.80 (95% CI: 1.68, 4.65)], and race [black – aHR 2.22 (95% CI: 0.93, 5.31); white – aHR 2.26 (95% CI: 1.54, 3.34)].

Conclusions:

Low medication adherence using the ‘hybrid’ K-Wood-MAS-4 predicts incident CVD in a cohort of older adults with established hypertension.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease risk, hypertension, medication adherence, K-Wood-MAS-4, uncontrolled blood pressure, older women and men, PDC

CONDENSED ABSTRACT

Antihypertensive medication adherence was assessed in a cohort of 1,532 older adults without prior cardiovascular disease (CVD) using a hybrid adherence scale (K-Wood-MAS-4) developed to predict pharmacy refill adherence and capture four domains of adherence behavior: self-efficacy, physical function, intentional medication-taking, and forgetfulness. Participants were followed for a median of 2.8 years (maximum 3.8 years) after K-Wood-MAS-4 assessment to identify incident CVD events (stroke, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or CVD death). The adjusted hazard ratio for incident CVD associated with low adherence was 2.29 (95% CI: 1.61-3.26). Results were consistent within age, sex, and race sub-groups.

INTRODUCTION

Low medication adherence and uncontrolled BP remain major clinical and public health challenges among adults taking antihypertensive medication, even though the associations between taking prescribed antihypertensive medications, blood pressure (BP) control and reduced cardiovascular risk are well-established [1-7]. To address the ongoing challenges, there is a need for validated, open access tools to assess medication adherence among treated women and men with established hypertension. This may be especially important for older adults in the United States, a population with a high prevalence of hypertension, high rates of uncontrolled BP despite treatment, and high CVD risk [8], and for health care systems incorporating recommendations for lower BP treatment targets based on the new blood pressure guidelines [9].

Self-report adherence tools have the advantage over other assessment tools in that they can be captured from patients in real time and provide information on patient-specific barriers to adherence [10]. Key challenges of existing self-report tools include:

Tools may not reflect behaviors across the adherence cascade [11].

Tools may not be developed for associations with objective measures of adherence (e.g., pharmacy refill).

Self-report adherence has been inconsistently associated with incident CV events [1, 12, 13].

Data are limited that assess performance by age, sex, and racial subgroups.

Tools may not be open access.

In 2013, Krousel-Wood and colleagues published a manuscript describing a 4-item medication adherence scale (herein referred to as K-Wood-MAS-4) that predicted low pharmacy refill adherence and captured four domains of adherence behavior in older adults with uncontrolled hypertension [14]. However, the association of this tool with relevant clinical outcomes in a general sample of older adults with hypertension is not known. In the current study, we sought to determine the association of antihypertensive medication adherence using the K-Wood-MAS-4 with BP control and incident CVD in older adults. Using the established taxonomy for medication adherence research (i.e., initiation, implementation and discontinuation) [15], this study focuses on implementation behavior during the study period, which reflects the extent to which patients continue to take their medications as prescribed.

METHODS

Study population and study design

This is a secondary analysis of the Cohort Study of Medication Adherence in Older Adults (CoSMO), a prospective cohort study of factors associated with antihypertensive medication adherence and CVD among older adults with hypertension. The study design, response rates, and baseline characteristics were previously published [16]. In brief, 2194 women and men aged 65 years or older with essential hypertension, randomly selected from the roster of a large managed care organization in southeastern Louisiana, were recruited into the cohort. A baseline survey was conducted between August 2006 to September 2007 and two follow up surveys were administered approximately one and two years following the baseline survey. Data on CVD and mortality were collected through February 2011. The current analysis included CoSMO participants who answered all four K-Wood-MAS-4 questions at the first follow-up when the data for the items were first collected. The analyses were further restricted to participants who had no prior hospitalizations for stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or congestive heart failure (CHF) in the two years preceding the administration of the first follow-up survey and who had a calculated pharmacy refill adherence measure. The CoSMO study was categorized as minimal risk and approved by the Institutional Review Board and the privacy board of the managed care organization; participants provided verbal informed consent [16].

Exposure variables

The primary exposure was antihypertensive medication adherence as measured by the K-Wood-MAS-4 self-report medication adherence scale [14]. In brief, the self-report scale was developed to predict low pharmacy refill adherence in older adults with established and uncontrolled hypertension who were taking antihypertensive medication; this study focuses on implementation behavior [15]. The 4-item scale [14] was derived from 164 candidate items using an established conceptual model and validated tools for data capture. Using pharmacy refill in the prior year as the reference standard, the 4-item scale had moderate discrimination (C statistic of 0.704, 95% CI 0.683-0.714); had sensitivity and specificity of 67.4% and 67.8%, respectively; and performed comparably to other published tools [17-19]. The 4 items adapted from existing tools [19-21] capture four different domains of adherence behavior; each item was associated with pharmacy refill adherence: intentional and unintentional (i.e., forgetfulness) non-adherence, medication-taking self-efficacy and physical function quality of life [14]; the scale score is calculated by summing the points for the 4 questions (scale score ranges from 0 to 4, with higher score indicating worse adherence); low adherence on the K-Wood-MAS-4 was defined as a score ≥1 [14]. See Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content 1 for the K-Wood-MAS-4 items.

For comparison purposes, an objective measure of medication adherence was calculated from claims-based pharmacy refill data using prescription-based proportion of days covered (PDC). Fill dates, drug class, and days’ supply for all antihypertensive prescriptions filled in the year prior to the K-Wood-MAS-4 assessment were extracted from pharmacy utilization databases. For participants with at least two pharmacy fills in a drug class in the one-year time period, proportion of days covered (PDC) was calculated as the number of days with medication available divided by the number of days between the first and last pharmacy refills in the year. PDC was calculated for each antihypertensive medication class and averaged across all classes to yield an overall PDC in the year prior to K-Wood-MAS-4 assessment. Low pharmacy refill adherence was defined as PDC <0.8 [22].

Outcome variable

The primary outcome was the composite CVD endpoint of incident stroke, MI, CHF or cardiovascular death, from the time of the K-Wood-MAS-4 assessment through February 28, 2011 [1]. Hospitalizations for a CVD were identified through a comprehensive search of primary and secondary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD9) codes from administrative claims databases: codes 410.xx (except 410.x2) for MI; codes 402.x1, 428.xx, for CHF; and codes 430.xx, 431.xx, 432.xx, 433.xx, 434.xx for stroke. Deaths were identified using the Social Security Death Index and cross-checked against administrative claims and obituaries. Cause of death was recorded from death certificates, and when possible, confirmed using medical records. For each CVD, trained research nurses abstracted and recorded data from medical records and death certificates onto standardized forms [23]. A participant release was obtained prior to requesting and reviewing medical records for hospitalizations outside of the managed care system. Outcomes were adjudicated by two physicians (EDF, RNR), blinded to participant adherence status.

Blood pressure

For clinic visits occurring during the year from the baseline survey until the K-Wood-MAS-4 assessment, trained research staff, blinded to participant adherence status, abstracted systolic and diastolic BP measurements from medical records. For visits at which more than one measurement was taken, BP readings were averaged. Then, the average BP across all visits during the year prior to the first assessment with the K-Wood-MAS-4 was calculated [16]. Uncontrolled BP was defined as mean systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg or mean diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg [24].

Sociodemographic, clinical and behavioral variables

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, including marital status, age, sex, race, educational attainment, height and weight, duration of hypertension, and number of visits to a healthcare provider in the past year were obtained from the participant survey. Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2. Satisfaction with healthcare was measured via a modified version of the 15-item Group Health Association of America’s Consumer Satisfaction Survey [25]. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [26]. Social support was measured using the 19-item RAND Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey [27]. Stress was assessed using 4 items from the 14-item Perceived Stress Scale [28]. Participants’ use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for BP control was assessed via questions derived from a validated survey [29]. Self-reported healthy lifestyle behaviors included nonsmoking status, less than 2 alcoholic drinks per week, salt reduction, and fruit and vegetable consumption [30]. Claims data were used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index [31, 32] and to determine the number of classes of antihypertensive medication filled by each participant. All variables included in the analysis used data from the survey at the first follow up when the K-Wood-MAS-4 items were assessed, with the exception of hypertension duration, which was assessed during the baseline survey only.

Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics were calculated overall and by level of adherence (low versus high score as measured by the K-Wood-MAS-4). Chi-square tests were used to test for differences in participant characteristics by adherence level. Logistic regression models were used to calculate the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for uncontrolled BP in the period prior to K-Wood-MAS-4 assessment associated with low versus high adherence, for the K-Wood-MAS-4 and PDC, separately. The cumulative incidence of CVD was calculated overall and by level of adherence on the K-Wood-MAS-4 and PDC, separately, using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate the hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CI for incident CVD events associated with low versus high adherence. Separate models were used for the two adherence measures: K-Wood-MAS-4 and PDC. Initial models were adjusted for sociodemographics (age, sex, race, marital status, and education); subsequent models were further adjusted using the Charlson Comorbidity Index, number of classes of antihypertensive medication being taken, depressive symptoms, smoking status, body mass index, alcohol intake, fruit and vegetable consumption, and sodium reduction. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate HR and 95% CI associated with (1) each possible score on the K-Wood-MAS-4, and (2) for a one-unit increase on the K-Wood-MAS-4 scale, with a higher score reflecting worse adherence. Differences in the association between antihypertensive medication adherence and the composite cardiovascular outcome across subgroups defined by age, race, and sex were evaluated by including an interaction term in final multivariable regression models (e.g., K-Wood-MAS-4 * race). Because one of the four items in the scale relates to physical function quality of life and is known to be associated with CVD events [33], a sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding the physical function quality of life item from the K-Wood-MAS-4 scale scoring. Additionally, Cox proportional hazards models assessed the adjusted hazard ratios for low K-Wood-MAS-4 adherence in a subsample of patients with uncontrolled hypertension (n=436). In a final analysis, we determined the hazard ratios for CVD associated with each K-Wood-MAS-4 item, separately.

All analyses were conducted using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Figures were created using R 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Of the 2003 participants who participated in the first follow-up survey, 48 did not have event data and 30 were excluded because their first CVD occurred prior to the first follow-up. An additional 205 participants were excluded because they skipped one or more questions comprising the K-Wood-MAS-4, and 188 more were missing pharmacy refill data at first follow-up. The mean age of the 1532 participants included in the analysis was 76.3 years and 61.2% were female, 27.7% were black, and 54.8% were married.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics according to adherence level using self-reported K-Wood-MAS-4

| Participant Characteristics, n (%) | Overall (N=1,532) |

Low Adherers* (N=593) |

High Adherers (N=939) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-Demographics | |||

| Age ≥ 75 years | 862 (56.3) | 333 (56.2) | 529 (56.3) |

| Female | 938 (61.2) | 390 (65.8) | 548 (58.4) ‡ |

| Black | 424 (27.7) | 197 (33.2) | 227 (24.2) ‡ |

| Married | 839 (54.8) | 313 (52.8) | 526 (56.0) |

| High school education or greater | 1235 (80.6) | 463 (78.1) | 772 (82.2) † |

| Clinical / Treatment Variables | |||

| Hypertension duration ≥ 10 Years | 963 (63.0) | 376 (63.6) | 587 (62.6) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score ≥ 2 § | 845 (55.2) | 362 (61.1) | 483 (51.4) ‡ |

| Body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 1151 (75.9) | 452 (77.4) | 699 (75.0) |

| 3+ classes of antihypertensive medication § | 706 (46.1) | 296 (49.9) | 410 (43.7) † |

| Health Care System Variables | |||

| Not satisfied with overall health care | 56 (3.7) | 38 (6.4) | 18 (1.9) ‡ |

| Not satisfied with communication | 119 (7.9) | 68 (11.6) | 51 (5.5) ‡ |

| Not satisfied with access to healthcare | 57 (3.7) | 34 (5.7) | 23 (2.5) ‡ |

| Reduced antihypertensive medications due to cost | 34 (2.2) | 23 (3.9) | 11 (1.2) ‡ |

| 6+ visits to primary care physician § | 423 (27.7) | 202 (34.1) | 221 (23.6) ‡ |

| Psychosocial / Behavioral Variables | |||

| Current or former smoker | 749 (49.3) | 293 (49.7) | 456 (49.0) |

| ≥ 2 alcoholic beverages per week | 361 (23.6) | 111 (18.8) | 250 (26.6) ‡ |

| Depressive symptoms | 199 (13.0) | 118 (19.9) | 81 (8.6) ‡ |

| Low Social Support | 533 (34.8) | 233 (39.3) | 300 (32.0) ‡ |

| High Stress | 332 (21.7) | 171 (29.0) | 161 (17.2) ‡ |

| Self-Management Behaviors | |||

| Complementary and alternative medicine use | 304 (19.8) | 120 (20.2) | 184 (19.6) |

| Increasing fruits and vegetables | 1196 (78.1) | 454 (76.6) | 742 (79.0) |

| Reducing salt | 1245 (81.3) | 472 (79.6) | 773 (82.3) |

Low adherers defined by ≥1 point on the K-Wood-MAS-4, where one point was assigned for response options reflecting less than perfect medication-taking behavior or limitations in health

p<0.05

p<0.01;

in the prior year

K-Wood-MAS-4 -Krousel-Wood 4-item medication adherence scale

Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Responded to all four items of the K-Wood-MAS-4 at 1st follow-up, had PDC at 1st follow up. Excluded if the first CVD (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, or cardiovascular death) occurred prior to 1st follow-up.

The prevalence of low adherence was 38.7% when measured by the K-Wood-MAS-4 and 23.0% when measured by PDC; K-Wood-MAS-4 adherence was associated with PDC adherence (χ2=44.9, p<0.001, concordance = 63.1%). Those categorized as having low adherence by the K-Wood-MAS-4 were more likely to be female, black, have two or more comorbidities, take three or more classes of antihypertensive medication, be dissatisfied with healthcare, indicate that they had reduced medications due to cost, report six or more visits to a healthcare provider in the last year, and report depressive symptoms, low social support, and high stress. Those with low adherence were less likely to have at least a high school education, and to drink two or more alcoholic beverages per week.

Uncontrolled blood pressure

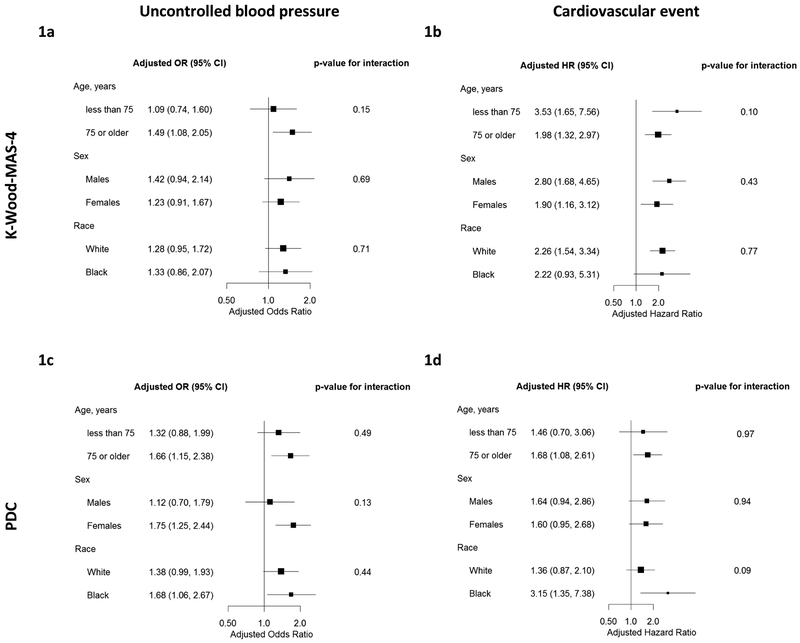

The prevalence of uncontrolled BP was 30.3%. Unadjusted and adjusted OR and 95% CI for low adherence and uncontrolled BP are presented in Table 2. After full multivariable adjustment, low adherence by the K-Wood-MAS-4 was associated with uncontrolled BP in the year prior (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.29, 95% CI 1.01-1.65). Low adherence by PDC was also associated with uncontrolled BP (aOR 1.48, 95% CI 1.13-1.93). The results for uncontrolled BP were qualitatively similar across sex, race, or age groups (Figures 1a and 1c and Table S2, Supplemental Digital Content 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for uncontrolled blood pressure associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence: K-Wood-MAS-4 and PDC

| n (%) with uncontrolled BP |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Model 1 OR (95% CI) |

Model 2 OR (95% CI) |

Model 3 OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 436 (30.3) | ||||

| K-Wood-MAS-4 | |||||

| Low adherence (≥1 point) | 192 (34.9) | 1.41 (1.12, 1.78) | 1.36 (1.08, 1.71) | 1.29 (1.02, 1.64) | 1.29 (1.01, 1.65) |

| High adherence (<1 point) | 244 (27.5) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Pharmacy refill | |||||

| Low PDC (< 0.8) | 123 (37.5) | 1.53 (1.18, 1.98) | 1.49 (1.15, 1.94) | 1.46 (1.12, 1.90) | 1.48 (1.13, 1.93) |

| High PDC (≥ 0.8) | 313 (28.2) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

OR – Odds Ratio; CI – confidence interval; K-Wood-MAS-4 – Krousel-Wood 4-item medication adherence scale; PDC – proportion of days covered; BP – blood pressure

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, and education.

Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 variables plus Charlson Comorbidity Index, number of classes of antihypertensive medications, and depressive symptoms.

Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 variables plus smoking status, body mass index, alcohol intake, fruit and vegetable consumption, and sodium reduction.

Figure 1.

a (top left). Adjusted odds ratios for uncontrolled blood pressure associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence as measured by the K-Wood-MAS-4, stratified by age, sex, and race

b (top right). Adjusted hazard ratios for the composite cardiovascular outcome associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence as measured by the K-Wood-MAS-4, stratified by age, sex, and race

c (bottom left). Adjusted odds ratios for uncontrolled blood pressure associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence as measured by pharmacy refill (proportion of days covered), stratified by age, sex, and race

d (bottom right). Adjusted hazard ratios for the composite cardiovascular outcome associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence as measured by pharmacy refill (proportion of days covered), stratified by age, sex, and race

OR – odds ratio; HR – hazard ratio; CI – confidence interval; K-Wood-MAS-4 – 4-item Krousel-Wood Medication Adherence Scale; PDC – Proportion of Days Covered

Composite cardiovascular event outcome includes occurrence of hospitalized myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, or cardiovascular death.

Models adjusted for age, sex, race marital status, education, Charlson Comorbidity Index, number of classes of antihypertensive medications, depressive symptoms, smoking status, body mass index, alcohol intake, fruit and vegetable consumption, and sodium reduction, minus the stratifying variable.

Incident cardiovascular events

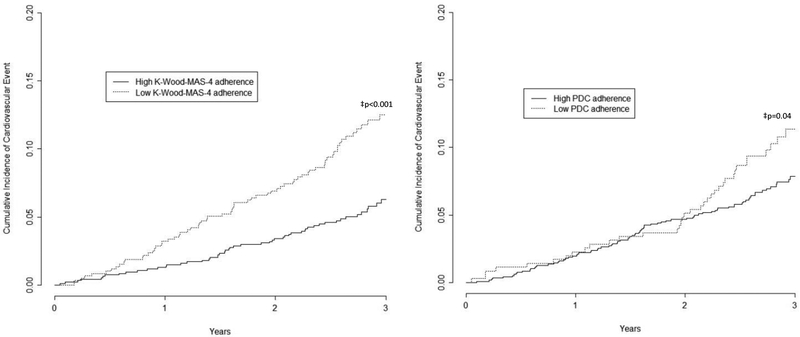

Over a median follow-up of 2.8 years (range 0.05, 3.8), 136 (8.9%) participants had a CVD event. Among these 136 participants, there were a total of 183 CVD, including 18 stroke events (affecting 1.2% of the 1532 participants), 47 MI events (3.1%), 79 CHF events (5.2%), and 39 cardiovascular deaths (2.6%). Incident CVD occurred in 12.8% versus 6.4% among those with low versus high adherence by the K-Wood-MAS-4, respectively (Figure 2a). The incidence of CVD was 11.7% and 8.1% among those with low versus high PDC adherence, respectively (Figure 2b). Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for incident CVD are presented in Table 3. After full multivariable adjustment, the hazard ratio for the composite incident CVD associated with low versus high adherence was 2.29 (95% CI 1.61-3.26) using K-Wood-MAS-4. The adjusted HR using PDC adherence comparing low versus high adherence was 1.59 (95% CI 1.10-2.32). The results for incident CVD were qualitatively similar when stratified by age, race, or sex (Figures 1b and 1d, and Table S3, Supplemental Digital Content 3).

Figure 2.

a (left). Cumulative incidence of composite cardiovascular outcome by level of antihypertensive medication adherence as measured by the K-Wood-MAS-4

b (right). Cumulative incidence of composite cardiovascular outcome by level of antihypertensive medication adherence as measured by pharmacy fill (proportion of days covered)

K-Wood-MAS-4 – 4-item Krousel-Wood Medication Adherence Scale; PDC – Proportion of Days Covered

‡ p-value for log-rank test

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for incident cardiovascular disease event associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence: K-Wood-MAS-4 and PDC

| n (%) with CV outcome |

Unadjusted HR (95% CI) |

Model 1 HR (95% CI) |

Model 2 HR (95% CI) |

Model 3 HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 136 (8.9) | ||||

| K-Wood-MAS-4 | |||||

| Low adherence (≥1 point) | 76 (12.8) | 2.16 (1.54, 3.04) | 2.30 (1.64, 3.24) | 2.16 (1.53, 3.06) | 2.29 (1.61, 3.26) |

| High adherence (<1 point) | 60 (6.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Pharmacy refill | |||||

| Low PDC (< 0.8) | 41 (11.7) | 1.46 (1.01, 2.10) | 1.66 (1.14, 2.40) | 1.59 (1.09, 2.30) | 1.59 (1.10, 2.32) |

| High PDC (≥ 0.8) | 95 (8.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

HR – Hazard Ratio; CI – confidence interval; K-Wood-MAS-4 – Krousel-Wood 4-item medication adherence scale; PDC – proportion of days covered; CV – cardiovascular

Composite CV outcome includes occurrence of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, or cardiovascular death.

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, and education.

Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 variables plus Charlson Comorbidity Index, number of classes of antihypertensive medications, and depressive symptoms.

Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 variables plus smoking status, body mass index, alcohol intake, fruit and vegetable consumption, and sodium reduction.

Additional analyses for incident cardiovascular events

When the association of each item in the K-Wood-MAS-4 with CVD events was analyzed separately, the items most strongly associated with incident CVD events were self-efficacy (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 2.08, 95% CI 1.18-3.68) and physical function quality of life (aHR 1.99, 95% CI 1.34-2.97). The associations of unintentional nonadherence and intentional nonadherence with CVD events were not statistically significant (aHR 1.34, 95% CI 0.90-2.00 and aHR 1.15, 95% CI 0.46-2.82, respectively).

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios calculated separately for K-Wood-MAS-4 scores (0, 1, 2, and 3-4) are presented in Table 4. The lowest CVD incidence (6.4%) was present among those scoring 0 (best adherence) on the K-Wood-MAS-4 while those scoring 3-4 (worse adherence) had the highest CVD incidence (15.8%). After full multivariable adjustment and relative to those scoring 0, the hazard ratio for the composite CVD was highest among those scoring 3-4 (worse adherence) (aHR 3.70, 95% CI 1.12-12.24). The adjusted hazard ratio for the composite CVD associated with a one-unit increase in K-Wood-MAS-4 score was 1.57 (95% CI 1.25-1.97). The adjusted results were similar in the sensitivity analyses: (1) eliminating the physical function quality of life item from the K-Wood-MAS-4 scale (aHR 1.50, 95% CI 1.04-2.17) and (2) restricting the analysis to the sample of older adults with uncontrolled hypertension (aHR 3.31, 95% CI 1.73-6.37).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for incident cardiovascular event associated with antihypertensive medication adherence score

| n (%) | n (%) with CV outcome |

Unadjusted HR (95% CI) |

Model 1 HR (95% CI) |

Model 2 HR (95% CI) |

Model 3 HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 136 (8.9) | |||||

| K-Wood-MAS-4 | ||||||

| 0 | 939 (61.3) | 60 (6.4) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| 1 | 468 (30.6) | 65 (13.9) | 2.34 (1.64, 3.32) | 2.41 (1.69, 3.43) | 2.28 (1.59, 3.25) | 2.41 (1.68, 3.47) |

| 2 | 106 (6.9) | 8 (7.6) | 1.28 (0.61, 2.68) | 1.53 (0.72, 3.21) | 1.38 (0.65, 2.93) | 1.46 (0.69, 3.10) |

| 3-4* | 19 (1.2) | 3 (15.8) | 2.77 (0.87, 8.82) | 3.54 (1.10, 11.42) | 3.50 (1.07, 11.53) | 3.70 (1.12, 12.24) |

| K-Wood-MAS-4 (continuous score) | ||||||

| -- | -- | 1.46 (1.18, 1.81) | 1.59 (1.27, 1.98) | 1.53 (1.21, 1.92) | 1.57 (1.25, 1.97) | |

| K-Wood-MAS-4 (without physical function quality of life) † | ||||||

| Low adherence (≥1 point) | 404 (26.4) | 43 (10.6) | 1.37 (0.95, 1.96) | 1.47 (1.02, 2.12) | 1.44 (1.00, 2.07) | 1.50 (1.04, 2.17) |

| High adherence (<1 point) | 1128 (73.6) | 93 (8.2) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

only N=2 had a score of 4, and neither of these two had an event

excludes item related to limitations in moderate activities (physical function quality of life)

HR – Hazard Ratio; CI – confidence interval; K-Wood-MAS-4 – Krousel-Wood 4-item medication adherence scale; CV – cardiovascular

Composite CV event includes occurrence of hospitalized myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, or cardiovascular death.

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, and education.

Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 variables plus Charlson Comorbidity Index, number of classes of antihypertensive medications, and depressive symptoms.

Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 variables plus smoking status, body mass index, alcohol intake, fruit and vegetable consumption, and sodium reduction.

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates that in community dwelling older women and men, low adherence was present in 38.7% using the K-Wood-MAS-4, and was associated with uncontrolled blood pressure. Participants identified as having low medication adherence using the self-report K-Wood-MAS-4 had a 2-times higher risk of a CVD event over a median follow up of 2.8 years when compared to their counterparts with high adherence. The results were stronger when using K-Wood-MAS-4 versus PDC to identify low adherers and when limiting the analysis to those with uncontrolled hypertension; results were qualitatively similar when stratified by age, sex, and race. This finding between low self-report adherence with K-Wood-MAS-4 and CVD is in contrast to previous reports that did not identify a statistically significant association between low self-report adherence using other adherence scales and CVD [1, 12]. The current findings suggest that the K-Wood-MAS-4 scale, available in the public domain, may be useful in identifying and monitoring older women and men at risk for low antihypertensive medication adherence and adverse clinical outcomes.

Distinct from other published tools, the K-Wood-MAS-4 represents a ‘hybrid’ tool – a self-report tool that assesses four different domains of adherence behavior (i.e., intentional non-adherence, forgetfulness, medication-taking self-efficacy, and physical function quality of life) along with frequency of such behaviors which may influence clinical outcomes and was developed using an objective pharmacy refill adherence measure as the reference standard. Taking less than 1 minute to complete, this combination scale reflects behaviors across the adherence cascade [11] and may render a more precise estimate of adherence. While the association between K-Wood-MAS-4 and PDC was statistically significant, the concordance was only 63%. Given the hybrid nature of the K-Wood-MAS-4, reflecting a cascade of adherence behaviors [11] including ‘medication taking’ and ‘medication filling/refilling’ and the fact that PDC captures ‘medication filling/refilling’ only, perfect concordance between these tools is not expected. The finding that the association of K-Wood-MAS-4 adherence with incident CVD was stronger than the association with PDC pharmacy refill is encouraging for this hybrid tool and may signal that the K-Wood-MAS-4 tool facilitates detection of important dimensions influencing adherence behavior and clinical outcomes which are not captured using PDC. The analysis of individual items in the scale development paper on a subset of patients with uncontrolled hypertension [14] revealed that the item with the strongest association with pharmacy refill was intentional nonadherence (How often do you miss taking medications when you feel better?). In the current analysis using the K-Wood-MAS-4 in a broader sample to assess associations with incident CVD events, the items most strongly associated with incident CVD events were medication-taking self-efficacy and physical function quality of life. While prior work [34, 35] has reported the association between poor physical function and clinical outcomes, the self-efficacy item reflects if patients are “bothered by taking their medications”. A positive response to this item may translate into identification of subconscious motives for nonadherence (a domain not captured by other self-report adherence tools). Targeting subconscious or ‘hidden’ motives underlying adherence behavior may provide a novel approach for improving medication-taking and reducing CVD events in patients with low implementation adherence to antihypertensive medications [36].

The consistency of a statistically significant association with clinical outcomes when adherence was measured using K-Wood-MAS-4 and using PDC pharmacy fill is reassuring given that K-Wood-MAS-4 items were measured annually (prior work revealed an annual rate of decline of only 4.3% for self-report adherence in a cohort of older patients with established hypertension over 2 years of follow up [37]). PDC was calculated using all available pharmacy claims data over twelve months. The stratified and sensitivity analyses revealing similar findings across age, sex, and race subgroups provides additional support for the scale.

Objective measures of antihypertensive medication adherence such as pharmacy refill have been consistently shown to be associated with BP control and clinical outcomes [1, 38]. Yet, pharmacy refill data are not readily accessible in most settings for routine assessment of adherence and do not provide information on determinants of adherence behavior.

Self-report adherence to antihypertensive medications has been consistently associated with blood pressure control [1, 17]. However, uncertainty exists regarding the association between self-report adherence and incident CVD. Prior investigations exploring associations between self-report adherence and CVD in older adults have yielded inconsistent results [1, 12, 13, 39] and issues related to reliability [40], recall and social desirability biases associated with self-report tools have been reported. Additionally, in previous research, we found no association between self-report medication adherence using another published tool and incident CVD among older adults with hypertension, but did find a significant association between low pharmacy refill (using Medication Possession Ratio and PDC) and incident CVD [1]. It was suggested that the lack of congruence of these findings may have been due to differences in what the tools measure across the adherence cascade [40, 41]. The results of the current study indicate that a ‘hybrid’ open access self report medication adherence scale that was developed to predict low pharmacy refill, captures multiple domains of adherence, and is associated with uncontrolled BP and incident CVD may overcome some of the challenges of measuring adherence with self-report tools and provide options for real-time assessment of medication adherence in treated older adults with established hypertension (i.e., implementation adherence). The survival curves separated earlier using the K-Wood-MAS-4 when compared to PDC. This may be because the hybrid tool reflects multiple domains influencing adherence behavior and clinical outcomes and may be more sensitive to predicting CV events than a tool capturing only one domain (i.e., medication refilling). As the need to identify and address low medication adherence in clinical and research settings increases, the availability of validated and open access self-report adherence tools that are linked to BP control and incident CVD is key to identify and monitor individuals with established hypertension at high risk of low adherence and ultimately poor outcomes.

Limitations and strengths

The current study was limited to insured adults ≥ 65 years of age in one region of the US, English-speaking, and relatively high adherence; thus results may not be generalizable to all people with hypertension [1]. Higher adherence rates have been reported in older compared to younger adults [42, 43]. Further research regarding the use of the K-Wood-MAS-4 scale in younger adults from broader regions is warranted. The K-Wood-MAS-4 has been internally validated; external validation is underway in another research study. Self- reported and pharmacy fill adherence measures do not assure that medications are taken correctly by patients; nevertheless, the association between K-Wood-MAS-4, pharmacy refill, blood pressure control and incident CVD supports the link between what K-Wood-MAS-4 measures and actual adherence behavior. Future studies could consider comparison of K-Wood-MAS-4 with direct assessment of adherence by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to detect drug metabolites in the blood or urine; however, direct assessment may not reflect general adherence behavior and may be subject to misclassification of ‘white coat adherers,’ patients who take their medications in the days/week prior to clinic visits. This study captured medication adherence in treated patients with established hypertension which reflects implementation behavior [15]; further research assessing associations between adherence initiation or discontinuation and incident CVD is needed. Uncontrolled BP was abstracted from medical records and not measured using standardized research measurement methods; further work using standardized blood pressure measurements is underway. Although CVD diagnoses in administrative databases were confirmed against medical records, misclassification of CVD is possible; however, it is unlikely to have been different among the adherence groups.

The study has several strengths. To our knowledge, the association of this hybrid self-report adherence tool for antihypertensive medications with incident outcomes in older adults has not been previously reported. This recently developed scale was correlated with pharmacy refill adherence and has comparable performance statistics to published adherence tools [14]. In addition, the prospective design, inclusion of a diverse sample of community-dwelling older adults with hypertension, extensive collection of risk factors and barriers to medication adherence, focus on clinical outcomes, and availability of an objective pharmacy adherence measure for comparison with the K-Wood-MAS-4 are strengths of this study. The restriction of our sample to older adults in a managed care setting minimizes the confounding effects of health insurance, access to medical care, and employment status. Advantages of this scale relative to other methods of adherence assessment include the fact that the K-Wood-MAS-4 is open access, takes less than one minute to complete, is associated with objective pharmacy fill and clinical outcomes, and captures four dimensions of adherence behavior: self-efficacy, physical function quality of life, intentional, and unintentional adherence.

Conclusion:

The K-Wood-MAS-4 self-report ‘hybrid’ tool overcomes challenges of self-report adherence assessment in that it is open access, captures 4 domains of medication-taking behavior, is linked to pharmacy refill, and identifies older patients with low implementation adherence, across age, sex, and race subgroups, which translates to uncontrolled hypertension and a 2-fold increase in CV events. Once patients with possible low adherence are identified, providers and researchers can explore reasons for nonadherence, counsel on the importance of high adherence, and recommend solutions (e.g., use of pill box reminder to address forgetfulness, health coaching to address low self-efficacy).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sponsor’s Role: The project described was supported by Grant Number R01 AG022536 from the National Institute on Aging (Krousel-Wood-Principal Investigator). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: This work was supported, in part, by R01 AG022536 from the National Institute on Aging (Krousel-Wood-Principal Investigator) and by K12 HD043451 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (Krousel-Wood-Principal Investigator; Peacock-Analyst). The authors have also received support from UL1 TR001417 (Krousel-Wood) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and from U54 GM104940 (Krousel-Wood) and P20 GM109036 (Mills, Li, Chen, Krousel-Wood, Whelton) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Paul Muntner has received research support from Amgen unrelated to the work presented in this manuscript. For the remaining authors, no potential conflicts of interest were declared.

Footnotes

Conference Presentation: This work was presented, in part, at the European Society for Patient Adherence and Compliance Annual Meeting, 2015.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krousel-Wood M, Holt E, Joyce C, Ruiz R, Dornelles A, Webber LS, et al. , Differences in cardiovascular disease risk when antihypertensive medication adherence is assessed by pharmacy fill versus self-report: the Cohort Study of Medication Adherence among Older Adults (CoSMO). J Hypertens, 2015. 33(2): p. 412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey JE, Wan JY, Tang J, Ghani MA, Cushman W, Antihypertensive medication adherence, ambulatory visits, and risk of stroke and death. J Gen Intern Med, 2010. 25(6): p. 495–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corrao G, Parodi A, Nicotra F, Zambon A, Merlino L, Cesana G, et al. , Better compliance to antihypertensive medications reduces cardiovascular risk. J Hypertens, 2011. 29(3): p. 610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esposti LD, Saragoni S, Benemei S, Batacchi P, Geppetti P, Di Bari M, et al. , Adherence to antihypertensive medications and health outcomes among newly treated hypertensive patients. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res, 2011. 3: p. 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kettani FZ, Dragomir A, Cote R, Roy L, Berard A, Blais L, et al. , Impact of a better adherence to antihypertensive agents on cerebrovascular disease for primary prevention. Stroke, 2009. 40(1): p. 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazzaglia G, Ambrosioni E, Alacqua M, Filippi A, Sessa E, Immordino V, et al. , Adherence to antihypertensive medications and cardiovascular morbidity among newly diagnosed hypertensive patients. Circulation, 2009. 120(16): p. 1598–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS, Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care, 2005. 43(6): p. 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. , Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2015. 131(4): p. e29–e322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. , 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawkshead J, Krousel-Wood MA, Techniques of measuring medication adherence in hypertensive patients in outpatient settings: advantages and limitations. Dis Manag Health Outcomes, 2007. 15: p. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peacock E and Krousel-Wood M, Adherence to Antihypertensive Therapy. Med Clin North Am, 2017. 101(1): p. 229–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu JR, Mosser DK, Chung ML, Lennie TA, Objectively measured, but not self-reported, medication adherence independently predicts event-free survival in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail., 2008. 14(3): p. 203–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gehi AK, Ali S, Na B, Whooley MA, Self-reported medication adherence and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease: the heart and soul study. Arch Intern Med, 2007. 167(16): p. 1798–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krousel-Wood M, Joyce C, Holt EW, Levitan EB, Dornelles A, Webber LS, et al. , Development and evaluation of a self-report tool to predict low pharmacy refill adherence in elderly patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Pharmacotherapy, 2013. 33(8): p. 798–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, et al. , A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2012. 73(5): p. 691–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Islam T, Morisky DE, Webber LS, Barriers to and determinants of medication adherence in hypertension management: perspective of the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults. Med Clin North Am, 2009. 93(3): p. 753–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ, Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens, 2008. 10: p. 348–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Krousel-Wood M, Islam T, Webber LS, Re R, Morisky DE, Muntner P, New medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in seniors with hypertension. Am J Manag Care, 2009. 15(1): p. 59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim MT, Hill MN, Bone LR, Levine DM, Development and testing of the Hill-Bone Compliance to High Blood Pressure Therapy Scale. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs, 2000. 15(3): p. 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogedegbe G, Mancuso CA, Allegrante JP, Charlson ME, Development and evaluation of a medication adherence self-efficacy scale in hypertensive African-American patients. J Clin Epidemiol, 2003. 56(6): p. 520–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JE Jr. and Sherbourne CD, The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care, 1992. 30(6): p. 473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, Lee JL, Jan SA, Brookhart MA, et al. , Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am J Manag Care, 2009. 15(7): p. 457–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, et al. , Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol, 2002. 156(9): p. 871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, et al. , The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA, 2003. 289(19): p. 2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davies AR and Ware JE, GHAA’s consumer satisfaction survey and user’s manual. 1991, Group Health Association of America: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knight RG, Williams S, McGee R, Olaman S, Psychometric properties of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behav Res Ther, 1997. 35(4): p. 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherbourne CD and Stewart AL, The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med, 1991. 32(6): p. 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen S, Kamarck T, and Mermelstein R, A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav, 1983. 24(4): p. 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lengacher CA, Bennett MP, Kipp KE, Berarducci A, Cox CE, Design and testing of the use of a complementary and alternative therapies survey in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum, 2003. 30(5): p. 811–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Questionnaire. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003-04, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/sp_bpq_c.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR, A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis, 1987. 40(5): p. 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, and Ciol MA, Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol, 1992. 45(6): p. 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonaccio M, Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Persichillo M, De Curtis A, Cerletti C, et al. , Health-related quality of life and risk of composite coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular events in the Moli-sani study cohort. Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2017: p. 2047487317748452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown DS, Thompson WW, Zack MM, Arnold SE, Barile JP, Associations between health-related quality of life and mortality in older adults. Prevention Science, 2015. 16(1): p. 21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen NB, Badon S, Greenlund KJ, Huffman M, Hong Y, Lloyd-Jones DM, The association between cardiovascular health and health-related quality of life and health status measures among US adults: a cross-sectional study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2001–2010. Health and quality of life outcomes, 2015. 13(1): p. 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krousel-Wood M, Kegan R, Whelton PK, Lahey LL, Immunity-to-Change: Are Hidden Motives Underlying Patient Nonadherence to Chronic Disease Medications? Am J Med Sci, 2014. 348(2): p. 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krousel-Wood M, Joyce C, Holt E, Muntner P, Webber LS, Morisky DE, et al. , Predictors of decline in medication adherence: results from the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults. Hypertension, 2011. 58(5): p. 804–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sikka R, Xia F, and Aubert RE, Estimating medication persistency using administrative claims data. Am J Manag Care, 2005. 11(7): p. 449–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathews R, Peterson ED, Honeycutt E, Chin CT, Effron MB, Zettler M, et al. , Early Medication Nonadherence After Acute Myocardial Infarction: Insights into Actionable Opportunities From the TReatment with ADP receptor iNhibitorS: Longitudinal Assessment of Treatment Patterns and Events after Acute Coronary Syndrome (TRANSLATE-ACS) Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 2015. 8(4): p. 347–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green LW, Mullen PD, and Friedman RB, Epidemiological and community approaches to patient compliance, in Patient Compliance in Medical Practice and Clinical Trials, Cramer JA and Spilker B, Editors. 1991, Raven Press: New York: p. 373–386. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steiner JF, Rethinking adherence. Ann Intern Med, 2012. 157(8): p. 580–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marentette MA, Gerth WC, Billings DK, Zamke KB, Antihypertensive persistence and drug class. Can J Cardiol, 2002. 18(6): p. 649–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rolnick SJ, Pawloski PA, Hedblom BD, Asche SE, Bruzek RJ, Patient characteristics associated with medication adherence. Clin Med Res, 2013. 11(2): p. 54–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.