Abstract

The postpartum period represents a critical window to initiate targeted interventions to improve cardiometabolic health following pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus and/or a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. The purpose of this systematic review was to examine studies published since 2011 that report rates of postpartum follow-up and risk screening for women who had gestational diabetes and/or a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and to identify disparities in care. Nine observational studies in which postpartum follow-up visits and/or screening rates were measured among United States (U.S.) women following pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes and/or a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy were reviewed. Rates of postpartum follow-up ranged from 5.7% to 95.4% with disparities linked to Black race and Hispanic ethnicity, low level of education, and co-existing morbidities such as mental health disorders. Follow-up rates were increased if the provider was an obstetrician/endocrinologist vs. primary care. Payer source was not associated with follow-up rates. The screening rate for diabetes in women who had gestational diabetes did not exceed 58% by 4 months across the studies analyzed, suggesting little improvement in the last 10 years. While women who had a hypertensive disorder appear to have had a postpartum blood pressure measured, it is unclear if follow-up intervention occurred. Overall, postpartum screening rates for at-risk women remain suboptimal and vary substantially. Further research is warranted including reliable population level data to inform equitable progress to meeting the evidence-informed guidelines.

Keywords: cardiometabolic health, gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, postpartum follow-up, postpartum screening

Precis statement:

Despite evidence-informed guidelines, population data demonstrate that postpartum screening rates of women who manifested gestational diabetes and/or a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy remain suboptimal and vary substantially.

Introduction

The federal passage of the “Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018” highlights the urgency to focus on maternal health and mortality in the United States (U.S.), specifically related to postpartum care and follow-up.1 Cardiometabolic complications of pregnancy, specifically preeclampsia and other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, are a leading cause of preventable maternal and infant mortality.2 Pregnancy is also now recognized as a cardiometabolic stress test wherein the manifestation of a pregnancy complication such as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (HDP), or preterm delivery, reveals evolving risk for long-term maternal cardiovascular disease.3 Racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S., particularly African American or Black, Native American, and Latina women, as well as low-income women, experience greater prevalence of these pregnancy complications and the long-term cardiometabolic disease sequelae.4–8 Further, exposure to these pregnancy complications during fetal development is linked with heightened risk of offspring cardiometabolic disease in adulthood and can contribute to population-level health disparities.9

In 2011, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) issued a joint practice guideline for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women that, for the first time, acknowledged a cardiometabolic complication during pregnancy as a significant risk factor for future maternal cardiometabolic disease.10 Specific U.S. guidelines for postpartum screening following GDM include those issued by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and indicate that glucose screening occur between 4 – 12 weeks after delivery.11,12 Specific U.S. guidelines for postpartum screening for HDP, from ACOG, indicate that blood pressure be monitored in the hospital (or with an equivalent level of outpatient surveillance) for 72 hours after birth, and checked again at 7–10 days postpartum (or sooner if a woman is symptomatic).13 Ongoing follow-up and blood pressure screening is recommended to continue at the 6-week postpartum and subsequent visits.

In the past nine years, several professional associations have also issued new recommendations for postpartum follow-up care. In May of 2018, the ACOG published a Committee Opinion titled, “Optimizing Postpartum Care.”14 This document highlighted the importance of the “fourth trimester”15 and posits that a new paradigm of maternal postpartum follow-up reflect tailored, personalized ongoing care to be initiated within 3 weeks postpartum and to continue as needed with a final, comprehensive visit no later than 12 weeks after birth.

Despite longstanding recommendations for postpartum follow-up care and more recent recommendations qualifying the specific screening content of this care, as many as 40% of women do not attend any postpartum visit.14,16 Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), a surveillance system of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state health departments representing almost 83% of U.S. births, suggest wide racial/ethnic disparities exist in the percent of women who attend a postpartum care visit with a healthcare provider. In 2012, the difference between the best (Asian only) and worst (American Indian and or Alaska Native) group rates was 9.8 percentage points. Women with limited resources are also more likely to miss follow-up care during the postpartum timeframe, which can contribute to greater health disparities.17 Poor rates of postpartum follow-up and risk screening among women with pregnancies complicated by GDM or a HDP have also been reported. In 2010, Tovar and colleagues18 published a systematic review of studies published between 2008 and 2010 that focused on postpartum follow-up and glucose screening for women with GDM; they found that rates of follow-up were less than half overall and ranged from 34% to 73%. In a large managed care system with streamlined care pathways, across 14,448 deliveries over 11 years (1995–2006), the postpartum diabetes screening rate in women with GDM did increase (20.7% to 53.8%), but still almost half of women were not tested.19 More recent reviews have not been published examining rates of post-partum follow-up and risk screening, particularly since the 2011 ACC/AHA guidelines were published, and no reviews have included rates of postpartum screening of women with a HDP. Therefore, because the postpartum period represents a critical window to initiate targeted interventions to improve cardiometabolic health, the purpose of this review is to examine studies published since 2011 in which rates of postpartum follow-up and risk screening for women who had GDM and/or a HDP were reported. Studies were also reviewed to assess reported disparities in postpartum follow-up care. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement20 served as a guide in reporting the findings of this review.

Methods

Data Sources

A systematic search of MEDLINE was conducted to identify relevant English language, original research articles published electronically or in print from January 2011 through October 2018. This timeframe was selected to augment and update prior related reviews, particularly considering the ACC/AHA guidelines that were updated and released in 2011.10 Two distinct search arms of this systematic review were conducted to capture studies related to postpartum follow-up following both gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Search terms in the first arm included ‘gestational diabetes’ AND ‘postpartum follow-up’ AND ‘diabetes screening,’ and ‘healthcare.’ Search terms in the second search included ‘hypertens*’ AND ‘postpartum follow-up,’ and ‘postpartum’ AND ‘blood pressure screening,’ and ‘preeclampsia’ AND ‘postpartum follow-up’. Inclusion criteria were: (a) study participants were U.S. women with diagnoses of pregnancy-related complications (GDM or HDP); (b) the study measured rates of two aspects of postpartum follow-up care: visits and screening rates; (c) the study employed an observational design (cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional). The review was limited to quantitative or mixed-methods studies, excluding studies that were solely qualitative. The focus was to capture current standard clinical practice of postpartum follow-up; therefore, experimental studies were also excluded.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

A two-step exclusion process to identify relevant articles was used. First, two authors, designated as the primary reviewers, conducted the two separate search arms of the systematic review to yield the initial search results. A third author, designated as secondary reviewer, then replicated the search protocol to confirm the literature pool. The primary and secondary reviewers reviewed titles and/or abstracts to determine if the article met inclusion criteria. After excluding duplicates and irrelevant articles, the primary and secondary reviewers appraised each remaining full article to determine inclusion. If there was concern about inclusion, all authors reviewed the full article to determine inclusion. Included articles were categorized according to focus on GDM, HDP, or both, and the setting for follow-up care (postpartum obstetric or endocrinology and/or primary care). Articles were compared by study objective, sample, design, methods, outcome variables, results, findings related to predictors of postpartum follow-up after GDM and/or HDP, and disparities in follow-up visit and screening rates. The risk of bias at the study-level was assessed using the domain-based evaluation recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration,21 and we assessed overall study quality (level of evidence) using the American Diabetes Association’s Evidence-Grading System22 which assigns ratings of A, B, C, or E depending on the quality of evidence. Across the studies in this review, the strength of the evidence was ranked as either supportive evidence from well-conducted cohort studies (Category B) or supportive evidence from poorly controlled or uncontrolled cohort studies (Category C), as we excluded randomized clinical trials and experimental studies (Category A) and expert consensus or clinical experience (Category E).22

Results

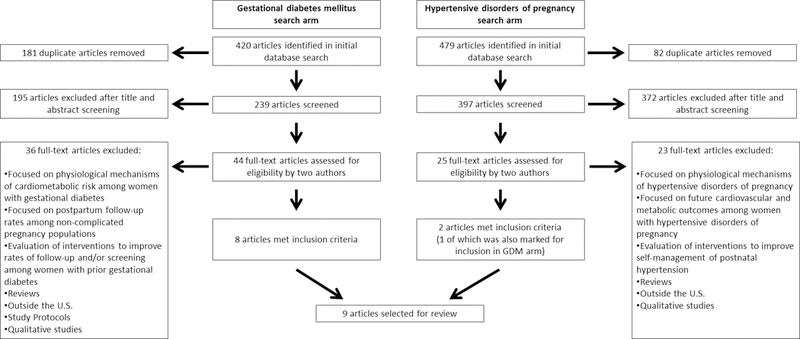

As indicated in the PRISMA flow diagram depicted in Figure 1, the initial search for the GDM arm yielded 420 articles; after removing duplicates, 239 articles were identified to be title and/or abstract reviewed by two authors. This resulted in the selection of 44 articles for full-text review; eight of these met inclusion criteria. The initial search for the HDP arm yielded 479 articles; after removing duplicates, 397 articles were identified to be title and/or abstract reviewed by two authors. This resulted in the selection of 25 articles for full-text review; two of these met inclusion criteria. Of these, one was simultaneously identified for inclusion in the GDM search arm since the study addressed both GDM and HDP.23 Therefore, as noted in Table 1, the results are from a final sample of nine articles (2014–2018) 16,23–30, representing nine unique studies that examined rates of, predictors of, and barriers to postpartum follow-up and screening among women diagnosed with GDM (n=6), HDP (n=1), or both (n=2). Among these, six were based on review of medical records;24–28,30 one was based on review of insurance claims;16 one was based on review of data from a large data warehouse;29 and, one was based on in-person questionnaires and interviews with postpartum women.23 The duration of the follow-up period ranged six weeks to three years across a total of 22,554 women (sample size range of 97 to 12,622; median, 373) with complicated pregnancies during 2003–2016. Combined, the studies include a racially and ethnically diverse population of childbearing women with minority representation ranging from 31% to 89%; notably, six studies16,25–28,30 had > 69% minority representation in the samples, reflective of the high-risk population of women who experience complications of pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Identification of articles for systematic review

Table 1.

Predictors of follow-up and screening identified across studies of postpartum follow-up among women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), published 2014–2018.

| Reference | Study Design and Setting | Study Outcomes | Racial/Ethnic Diversity of Sample, n (%) | Predictors of Follow-up Visits and Screening | Evidence-level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDM-Diagnosed Women Only | |||||

| Battarbee et al, 2018 (22) | Retrospective case-control N = 683 GDM-diagnosed postpartum women who delivered at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, Illinois, 2008–2016 |

(1) PP follow-up within 4-months (2) GTT completion (3) Reason for GTT completion failure (provider vs. patient noncompliance) |

Hispanic: 181 (26.5) non-Hispanic White: 164 (24) non-Hispanic Black: 149 (21.8) Other/Unknown: 115 (16.8) Asian: 74 (10.8) |

Factors associated with increased likelihood of follow-up visit: Older age, married, nulliparity, non-smoker, non-Hispanic, non-Asian Factors associated with decreased likelihood of follow-up visit: Medicaid insurance, preterm delivery, presented late to prenatal care, received care in clinic staffed by resident & fellow trainees Factors associated with increased likelihood of screening: Medicaid insurance, non-English speakers, presented late to prenatal care; trainee involvement associated with improved adherence to screening guidelines |

B |

| Bernstein et al, 2017 (21) | Extended-time, population-based study with national data from OptumLabs Data Warehouse N = 12,622 continuously-insured, GDM-diagnosed women followed from 1-year preconception through 3- years post-delivery, 2005–2015 |

(1) Follow-up glucose testing within 56–84 days, 1-year, and 3-years (2) Transition to primary care for monitoring (3) GDM recurrence (4) T2DM onset |

White: 67.4% Hispanic: 12.9% Asian: 12.3% African-American: 7.4% |

Continuous insurance coverage was not sufficient to smooth transition to primary care after pregnancy complicated by GDM | B |

| Mathieu et al, 2014 (16) | Observational, retrospective, single-cohort chart review N = 373 GDM-diagnosed postpartum women seen at a major academic medical center, 2010–2012 |

(1) PP follow-up within 4-months | Caucasian/white: 60% Latina/Hispanic: 17% Other (Middle Eastern, African, Asian): 14% African American/ Black: 9% |

Factors that decreased likelihood of follow-up visit: higher BMI at diagnosis and <high school education Black or Hispanic race/ethnicity | C |

| McCloskey et al, 2014 (17) | Retrospective cross-sectional chart review of administrative and clinical data N= 415 GDM-diagnosed postpartum women who used Boston Medical Center for regular care, 2003–2009 |

(1) PP glucose testing within 70 days and 180 days after delivery | non-Hispanic Black: 274 (66.0) Hispanic: 52 (12.5) non-Hispanic White: 48 (11.6) Asian: 30 (7.2) Other/Unknown: 11 (2.7) |

Factors associated with increased likelihood of screening: Having a primary care visit, racial/ethnic minority status Younger women were less likely to be screened |

B |

| Mendez-Figueroa et al, 2014 (18) | Pre-post program evaluation of demonstration project in Rhode Island; independent groups comparison with retrospective chart review* N= 181 GDM-diagnosed postpartum women seen in specialty clinic the previous 12 months, 2010–2012 |

(1) PP glucose testing within 3- months | Hispanic/Latina: 39.4% Non-Hispanic White: 27.2% African-American: 15% Other: 11.7% Asian: 6.7% |

Factors associated with decreased likelihood of screening: Younger age, single status, English spoken as primary language, smoker, and more weight gain in pregnancy |

C |

| Ortiz et al, 2016 (20) | Retrospective review of medical records N= 97 women with GDM receiving postpartum care in a tertiary care center in New Mexico, 2012 |

(1) PP visit within 14 weeks (2) PP glucose testing (3) Documentation of use of the 5 A’s framework for health promotion † |

Hispanic/Latina: 60% American Indian: 16% Other: 12% non-Hispanic White: 11% |

Factors associated with increased likelihood of follow-up visit: Non-Hispanic white, having private insurance |

C |

| HDP-diagnosed women only | |||||

| Levine et al, 2016 (19) | Planned secondary analysis, retrospective cohort N = 193 postpartum women (fixed sample size) diagnosed with severe preeclampsia in the parent study, 2011–2013 |

(1) Documented attendance at the 6-week postpartum visit (2) Persistent hypertension |

African-American: 149 (77.2) Caucasian: 22 (11.4) Other: 22 (11.4) |

Factors associated with increased likelihood of follow-up visit: Pre-pregnancy diabetes, cesarean delivery Factors associated with decreased likelihood of follow-up visit: Younger, African-American, fewer prenatal visits Morbidly obese women, women diagnosed with severe preeclampsia based on BP, and women who were discharged home on BP medication have a significantly higher risk of persistent hypertension |

B |

| GDM- and HDP-diagnosed women | |||||

| Bennett et al, 2014 (9) | Retrospective cohort using commercial & Medicaid insurance claims in Maryland N=7,741 women with complicated pregnancies (GDM, HDP, and pre-gestational diabetes) & 23,599 women with a non-complicated comparison pregnancy, 2003–2009 |

(1) Primary and postpartum obstetric care utilization rates in the 12 months after delivery | African-American: 48.4% White: 31.6% Other: 15.5% Hispanic: 4.5% |

For women with Medicaid insurance, major predictors of primary care within 1-year of delivery: Diagnosis of preeclampsia, DM, not GDM For women with commercial insurance, major predictors of primary care within 1-year of delivery: Other complicated medical conditions such as asthma, thyroid disease, but not pregnancy complications For women with Medicaid, statistically significant factors for predicting primary care visit within 1-year: White or Hispanic, older age, live in neighborhood with higher proportion of people without a high school diploma |

B |

| Ehrenthal et al, 2014 (15) | Prospective cohort N = 249 postpartum women with diagnosis of GDM, HDP, or both, recruited from community-based academic obstetrical hospital Interviews and surveys before hospital discharge and again at 3-months postpartum; years of data collection not reported |

(1) Self-reported attendance at the 6-week pp visit (2) Completion of glucose testing if they had GDM or follow-up BP testing if they had HDP (3) Ever having had lipid screening for women with either diagnosis |

Caucasian: 163 (65.5) African-American/ Black: 65 (26.1) Hispanic/Latina: 24 (9.6) Asian: 8 (3.2) Mixed race: 4 (1.6) |

Factors associated with increased likelihood of follow-up glucose testing: Private insurance, college education, married, high school level of health literacy Lipid screening was equally likely for women with GDM or HDP Factors associated with increased likelihood of follow-up cholesterol testing: ≥30 years age, college education, private health insurance Factors associated with decreased likelihood of follow-up screening tests: No college education, <high school level of health literacy, no private insurance |

B |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; PP, postpartum

For our review, we report on data from the pre-intervention group only, not the intervention group.

The 5 As include 5 recommended components of postpartum health promotion-related discussions: Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange

Overall Ranges of Postpartum Follow-Up

As noted in Table 2, follow-up visit rates varied extensively but were higher for specialty providers compared to primary care: 39.6% to 95.4% (median, 55%) of women followed up with an obstetrician/endocrinologist after complicated pregnancy (range of 6 weeks to 4 months post-delivery), and 5.7% to 60% (median, 37.1%) of women followed up with primary care (range of 6 months to 3 years).

Table 2.

Postpartum follow-up visit and screening rates among women with prior pregnancy complications.

| Reference | Postpartum Obstetric/ Endocrinology Care Follow-up Rates (%, time frame) |

Primary Care Follow-up Rates (%, time frame) | Glucose screening rate (%, time frame, test) | Blood pressure screening rate (%, time frame) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDM-diagnosed women only | ||||

| Battarbee et al, 2018 (22) | 82% (4 months) | -------------- | 49.8% (4 months, OGTT) |

-------------- |

| Bernstein et al, 2017 (21) | 39.6% (56–84 days) | 5.7% (6 months) 13.8% (12 months) 40.5% (3 years) |

5.8% (56–84 days, any glucose test) 21.8% (12 months, any glucose test) 51% (3 years, any glucose test) |

-------------- |

| Mathieu et al, 2014 (16) | 50% (4 months) | -------------- | -------------- | -------------- |

| McCloskey et al, 2014 (17) | 80.2% (10 weeks) | 33.7% (6 months) | 13.7% (10 weeks, any glucose test) 23.4% (6 months, any glucose test) |

-------------- |

| Mendez-Figueroa et al, 2014 (18) | -------------- | -------------- | 43.1% (3 months, OGTT) | -------------- |

| Ortiz et al, 2016 (20) | 55% (14 weeks) | -------------- | 19% (14 weeks, OGTT) | -------------- |

| HDP-diagnosed women only | ||||

| Levine et al, 2016 (19) | 52.3% (6 weeks) | -------------- | -------------- | 100% (6 weeks) |

| GDM- and HDP-diagnosed women | ||||

| Bennett el al, 2014 (9) | Medicaid: 65% (3 months) |

Medicaid: 56.6% (12 months) |

Medicaid: 5.7% (3 months, any glucose test) 15.2% (12 months, any glucose test) |

-------------- |

| Commercial insurance: 50.8% (3 months) |

Commercial insurance: 60% (12 months) |

Commercial insurance: 11.4% (3 months, any glucose test) 20.9% (12 months, any glucose test) |

||

| Ehrenthal et al, 2014 (15) | 95.4% (6 weeks) | -------------- | 57.9% (3 months, OGTT) | 97.9% (3 months) |

Abbreviations: GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Postpartum Obstetric/Endocrinology Care vs. Primary Care

Eight studies examined rates of postpartum follow-up in obstetric/endocrinology settings, spanning from 6 weeks to 4 months post-delivery (n=5 with GDM-diagnosed women only;24,25,28–30; n=2 with GDM- and HDP-diagnosed women,16,23; n=1 with severe preeclampsia, a HDP).27 Among GDM-diagnosed women, within the first 4 months postpartum, follow-up rates at obstetric/endocrinology appointments were 39.6%29, 50%24, 55%28, 80.2%25, and 82%.30 In the study targeting women after severe preeclampsia, only 52.3% attended a postpartum appointment within 6 weeks.27 In a prospective investigation with a study visit at 3 months post-delivery, 95.4% of women diagnosed with GDM, HDP, or both, self-reported attending a postpartum appointment within 6 weeks after delivery.23 Another study compared postpartum follow-up rates among women (GDM, HDP, or pre-existing diabetes) according to whether they had Medicaid or commercial insurance and found that, within 3 months of delivery, 65% of women with Medicaid and 50.8% of women with commercial insurance had attended a postpartum obstetric visit.16

Three studies examined rates of follow-up in primary care settings following complicated pregnancies (n=2, GDM-diagnosed women only,25,29; n=1 GDM and/or HDP.16) In one study, 33.7% of GDM-diagnosed women attended a primary care visit within 6 months,25 but another showed only 5.7% of GDM-diagnosed women had a visit with primary care within six months. This rate increased to 13.8% within one year, and 40.5% within three years, similar to rates in women without complications of pregnancy.29 In a comparison by insurance type, primary care follow-up rates (GDM, HDP, or pre-existing diabetes) within 12-months of delivery were similar; 56.6% of women with Medicaid and 60% of women with commercial insurance had primary care visit.16 Thus, even if covered by insurance, overall follow-up rates in specialty and primary care settings remain suboptimal.

Postpartum Screening for Type 2 Diabetes

Among GDM-diagnosed women, a disparate 5.7% to 57.9% (median, 21.8%) had any follow-up glucose screening post-delivery (range of 3 months to 3 years). The types of glucose screening varied across seven studies, including the recommended 2-hour, 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)26,28,30, or any form of glucose testing (OGTT, fasting plasma glucose, and/or hemoglobin A1c).16,23,25,29 In general, screening rates increased with time. Bennett et al. found that for women with Medicaid or commercial insurance, the rates of glucose screening increased between 3- to 12-months postpartum (5.7% to 15.2% for Medicaid; 11.4% to 20.9% for commercial.)16 Similarly, Bernstein et al. found that 5.8% of GDM-diagnosed women were screened with any glucose test within 56–84 days postpartum, 21.8% within 1 year, and 51% within 3 years29; McCloskey et al. found that 13.7% of women underwent glucose screening by 10 weeks and 23.4% by 6 months postpartum.25 On the other hand, Ehrenthal et al. found that 57.9% of GDM-diagnosed women had glucose testing by 3 months postpartum.23 Across single time-point studies a similar pattern was revealed: 19% completed the recommended OGTT by 6 weeks postpartum;28 43.1% within 3 months;26 and 49.8% within 4 months.30 Taken together, the data show that a substantial number of GDM-diagnosed women are not screened for diabetes.

Postpartum Screening for Hypertension

Ehrenthal et al. and Levine et al. reported that 97.9%23 and 100%27 of the women who presented for follow-up appointments within 6 weeks of delivery after HDP and severe preeclampsia, respectively, also completed blood pressure screening.

Disparities in the Likelihood of Postpartum Follow-up

Five studies found that race/ethnicity predicted likelihood of follow-up. Specifically, non-Hispanic White,28,30 Asian,30 and non-Black race16 predicted increased postpartum or primary care follow-up, while Black race24,27 and Hispanic ethnicity24 predicted decreased follow-up. Ortiz et al. found having private insurance was a predictor of follow-up in the obstetric setting.28 Interestingly, however, Medicaid coverage was a negative predictor of follow-up;30 and Medicaid eligibility (based on pregnancy) was associated with a decreased likelihood of primary care follow-up.16 Mathieu et al. found having less than a high school education was associated with decreased follow-up,24 a finding supported by the study of Bennett et al.16 Health-related factors associated with increased follow-up included older age,16,30 non-smoker,16,30 preeclampsia,16 preexisting diabetes,16,27 and depression.16 Mental health disorders in pregnancy and drug or alcohol use,16 late presentation to prenatal care,30 having fewer than five prenatal care visits,27 and increased body mass index at time of GDM diagnosis24 were associated with decreased follow-up. These data suggest continued disparities in follow-up associated with Black race and Hispanic ethnicity, lower education, having a mental health disorder, and having increased body mass index.

Disparities in the Likelihood of Postpartum Risk Factor Screening

Disparities in postpartum glucose and/or blood pressure screening rate were identified (n=4 studies). In one sample, women who had an OGTT after GDM were more likely to have Medicaid insurance (aOR=2.0; 95% CI 1.3–2.9), late presentation to prenatal care (>24 wks) (aOR=3.5; 95% CI 1.8–6.6), were non-English speaking (aOR=1.4, 95% CI 0.5–3.6), and used tobacco (aOR=0.7, 95% CI 0.2–2.1).30 Having trainee involvement increased the odds of completing the OGTT (aOR=4.6, 95% CI 2.4–8.8).30 Similarly, in a multi-ethnic sample of women, postpartum glucose testing was highest among Black, non-Hispanic women (25.3%), followed by Hispanic (23.1%), Asian (16.7%), and White women (8.3%).25 Ehrenthal et al. found higher rates of postpartum glucose and blood pressure screening among college-educated, married women with higher health literacy; for glucose testing, in particular, having private insurance (aOR = 5.0, 95% CI 1.6–14.9) and a high level of health literacy or greater (aOR 13.2, 95% CI 1.5–120.2) independently increased screening rates.23 On the other hand, younger age was associated with a decreased postpartum glucose screening25,26 and, compared to women with GDM who had a postpartum OGTT, women who did not were more often of single status (65.8% vs. 49.9%, p<0.01), were smokers (21.9% vs. 12.9%, p=0.02), and had increased gestational weight gain (30.0 vs. 26.4 lbs, p=0.02).26 Although factors such as higher education, higher health literacy, and insurance coverage in some settings increase the odds for postpartum risk screening, the preponderance of data suggest that despite increased odds, less than half of women are actually screened.

Discussion

In some women, pregnancy unmasks subclinical risk for cardiometabolic disease, representing a critical opportunity for primary and secondary prevention. Gestational diabetes is associated with a 7-fold increased risk for future Type 2 diabetes,31 and a HDP is associated with a 6-fold increased risk of future hypertension and a 4-fold increased risk of Type 2 diabetes 10–20 years after the index pregnancy.32 Yet, the findings presented here demonstrate that postpartum screening rates of women who manifested GDM and/or a HDP remain suboptimal and vary substantially. Rates of overall postpartum follow-up (with or without risk screening) range from 5.7%29 to 95.4%,23 with disparities in poor follow-up rates related to maternal factors such as Black race and Hispanic ethnicity, low level of education, and co-existing morbidities such as mental health disorders, while health care system issues related to provider type. There was a clear pattern of increased postpartum follow-up for obstetricians/ endocrinologists (range 50%−94%) compared to primary care providers (5.7%−60%). Despite evidence-informed guidelines and recommendations, the data demonstrate that many mothers do not receive appropriate or adequate postpartum care following complicated pregnancies and there has been little improvement in postpartum screening in the last 10 years.

Overall, these findings did not demonstrate that having access to health insurance coverage increased follow-up rates. Among continuously insured women who had GDM, one study showed that transition of monitoring from an obstetrician/endocrinologist to primary care increased postpartum follow-up rates over time from 6 months (5.7%) to 1 year (13.8%) to 3 years (40.5%).29 However, despite this increase, only 51% of women had been screened for diabetes 3 years after the pregnancy. Moreover, women who had Medicaid were less likely to attend a postpartum visit, including those eligible through a primary care system.16,30 One study suggested that having Medicaid coverage increased screening rates by 3 months in a primary care system in Maryland (compared to having commercial insurance),16 and another suggested Medicaid coverage in Chicago, Illinois, decreased screening rates at 4 months.30 The variation could be attributed to differences in state Medicaid polices and the structure and organization of the practices included in the respective studies. Furthermore, when comparing a population of women with Medicaid insurance to one covered by commercial insurance, Medicaid status likely serves as a proxy for low-income or education status, confounding this association. Although increasing access to insurance coverage is one strategy to address this priority, the data suggest that other factors be incorporated into policy and planning discussions. These patterns underscore that insurance coverage alone does not increase screening rates, as in countries where national healthcare has been implemented.33–35 Under the Affordable Care Act, maternal and newborn care is considered one of the ten essential health benefits and new health plans are required to cover and eliminate the cost sharing for preventive services. Yet, eligibility restrictions likely limit the accessibility of postpartum care for certain subgroups, again highlighting that access does not necessarily equate to utilization.

In terms of specific postpartum screening rates for at-risk women with GDM, the data here indicate that at best, >40% of women have not been tested by 12 weeks.23 In contrast, nearly all women (98% at 6 weeks23 and 100% at 3 months27) who had severe pre-eclampsia, GDM, or a HDP had a blood pressure screening documented. These high rates may reflect, in part, the more ubiquitous nature of blood pressure screening as a standard vital sign as compared to glucose screening. Worldwide, postpartum diabetes screening rates are <50%,33,34,36,37 either due to healthcare delivery system issues and timing of the test38,39 or provider knowledge deficits related to standard of care recommendations.35,39,40 Moreover, women who had GDM identify barriers to postpartum screening to include fatigue,39 fear of a diabetes diagnosis,41 incomplete understanding of the risk for diabetes,42,43 more concern about delivery outcomes than long-term diabetes risk, and environmental issues such as transportation difficulties and work responsibilities.39,42,44 Importantly, trust in the clinician was recently identified as an independent, modifiable factor associated with increased postpartum glucose screening in women who had GDM.44 Although the limited data available and presented here suggest that nearly all women with a pregnancy complication were screened for postpartum blood pressure abnormalities, the lack of study in this area limits the ability to more fully understand current blood pressure screening rates.

This analysis revealed several patterns of predictors of high and low postpartum follow-up and risk screening that may be underscored for consideration in future policy and intervention implementations. High rates of postpartum follow-up (not necessarily screening) were consistently associated with: White, non-Hispanic,28,30 Asian30 and non-Black16 racial and ethnic groups, having pre-conception non-public insurance coverage and a higher level of education among those also covered by private insurance.28 On the other hand, a lengthy list of consistent negative predictors included: Black race24,27 and Hispanic ethnicity,24 having less than a high school education,16,24 having a mental health disorder,16 and a higher BMI.24 Specific to postpartum diabetes screening after GDM, being younger, single, and a smoker with increased gestational weight gain were negative predictors of follow-up, while having a college education with higher health literacy and being married were positive predictors.26 Importantly, having private insurance and a minimum of a high school level of health literacy were independent predictors associated with increased completion of diabetes screening after GDM.23 Interventions such as reminder calls, involvement of nurses and outreach workers in direct case management of postpartum women,26 and improved communication between obstetricians and primary care providers45 have demonstrated some success in increasing postpartum follow-up. Further consideration of these interventions along with the trends and barriers identified may lead to innovative interventions to improve postpartum follow-up in the future.

Limitations

There were several limitations of this review. The purpose was to review the current standard clinical practice of postpartum follow-up; thus, evidence from well-conducted, generalizable randomized controlled trials was excluded (Category A).22 Of the nine studies, only one focused solely on HDP; one focused on both GDM and HDP, and seven focused specifically on risk screening following GDM. There is a paucity of data evaluating postpartum risk screening following a HDP, which in part may be due to the routine, clinical practice of blood pressure vital sign assessment during a standard postpartum office visit. Overall, the strength of evidence of the nine studies was low to moderate. Two studies26,28 did not evaluate demographic or clinical factors as confounders, and thus, present potentially biased results. The retrospective nature of the review of data from electronic medical records, insurance claims, and a large data warehouse poses a significant limitation in that the data available reflects what providers originally documented, which may not completely capture all care delivered. Additionally, the inclusion of self-reported measures in one study23 results in high risk for measurement bias, specifically recall or social desirability bias. Lastly, this review is subject to both publication bias and publication language bias as unpublished studies and those published in a language other than English were not able to be included.

Future Directions in Postpartum Care

There remains a substantial knowledge gap in understanding the poor rates of postpartum follow-up and screening for women who had GDM and/or a HDP. Further research is warranted and reliable population level data to inform equitable progress to meeting the guidelines is needed. PRAMS is the only population-based study in the United States that identifies women with GDM. Participating states can opt to include questions about postpartum screening for a more robust understanding of trends in postpartum follow-up and screening. The creation of a data infrastructure that can link data from pregnancies complicated by GDM and/or HDP in women receiving care in federally qualified health plans may also help characterize screening rates in low-income women.46 Finally, preliminary evidence demonstrates that it may be feasible and accurate to conduct postpartum glucose screening after GDM within days of delivery, before hospital discharge, representing a tremendous opportunity to increase postpartum screening rates.47

Conclusion

In conclusion, postpartum follow-up and screening rates in women who manifested GDM and/or a HDP remain suboptimal in the U.S. Health insurance coverage did not improve the rates of postpartum follow-up and screening; thus, future planning for interventions and policy must be multi-faceted to target non-modifiable factors such as Black and Hispanic ethnicity and modifiable factors such as postpartum depression, mental health disorders, trust in clinicians, and provider knowledge of screening and follow-up recommendations. The postpartum period represents a critical window to initiate targeted interventions to prevent maternal mortality and to improve maternal cardiometabolic health. With the federal passage of the “Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018”,1 systematic data collection of maternal mortality rates and identification of the causes and contributing factors to maternal mortality will aid in understanding postpartum follow-up and care. As systems-level modifications take shape in the coming years, providers across settings can consider implementing strategies such as reminder calls, involvement of case workers, improving communication between women and the care team, and importantly, building trust with the diverse women for whom they care. Increased identification and early intervention in women at risk for immediate and long-term cardiometabolic disease may substantially decrease maternal mortality and forestall the rising incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, resulting in improved population health in the future.

Contributor Information

Emily J. Jones, Department of Nursing at the College of Nursing and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, MA.

Teri L. Hernandez, Department of Medicine and Nursing at the Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Diabetes; University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO and the College of Nursing; University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO.

Joyce K. Edmonds, Connell School of Nursing, Boston College, Boston, MA..

Erin P. Ferranti, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University, Atlanta, GA..

References

- 1.Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018, H.R. 1318, 115th Congress; 2018. Retrieved at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1318

- 2.American College of Obstetricians and Gynceologists Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:e1–e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferranti EP, Jones EJ, Hernandez TL. Pregnancy Reveals Evolving Risk for Cardiometabolic Disease in Women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2016;45:413–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:335–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1862–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manuck TA. Racial and ethnic differences in preterm birth: A complex, multifactorial problem. Semin Perinatol 2017;41:511–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiang AH, Li BH, Black MH, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes risk after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2011;54:3016–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang S, Cardarelli K, Shim R, Ye J, Booker KL, Rust G. Racial disparities in economic and clinical outcomes of pregnancy among Medicaid recipients. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:1518–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker DJ, Thornburg KL. The obstetric origins of health for a lifetime. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2013;56:511–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women−−2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1404–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e49–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care 2018;41:S137–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:1122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing Postpartum Care. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e140–e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spelke B, Werner E. The Fourth Trimester of Pregnancy: Committing to Maternal Health and Well-Being Postpartum. R I Med J (2013) 2018;101:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett WL, Chang HY, Levine DM, et al. Utilization of primary and obstetric care after medically complicated pregnancies: an analysis of medical claims data. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:636–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryant AS, Haas JS, McElrath TF, McCormick MC. Predictors of compliance with the postpartum visit among women living in healthy start project areas. Matern Child Health J 2006;10:511–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tovar A, Chasan-Taber L, Eggleston E, Oken E. Postpartum screening for diabetes among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Prev Chronic Dis 2011;8:A124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrara A, Peng T, Kim C. Trends in postpartum diabetes screening and subsequent diabetes and impaired fasting glucose among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus: A report from the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Study. Diabetes Care 2009;32:269–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Diabetes Association. Introduction: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care 2018;41:S1–S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehrenthal DB, Maiden K, Rogers S, Ball A. Postpartum healthcare after gestational diabetes and hypertension. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:760–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathieu IP, Song Y, Jagasia SM. Disparities in postpartum follow-up in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Clin Diabetes 2014;32:178–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCloskey L, Bernstein J, Winter M, Iverson R, Lee-Parritz A. Follow-up of gestational diabetes mellitus in an urban safety net hospital: missed opportunities to launch preventive care for women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:327–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendez-Figueroa H, Daley J, Breault P, et al. Impact of an intensive follow-up program on the postpartum glucose tolerance testing rate. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;289:1177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine LD, Nkonde-Price C, Limaye M, Srinivas SK. Factors associated with postpartum follow-up and persistent hypertension among women with severe preeclampsia. J Perinatol 2016;36:1079–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ortiz FM, Jimenez EY, Boursaw B, Huttlinger K. Postpartum Care for Women with Gestational Diabetes. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2016;41:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernstein JA, Quinn E, Ameli O, et al. Follow-up after gestational diabetes: a fixable gap in women’s preventive healthcare. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2017;5:e000445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Battarbee AN, Yee LM. Barriers to Postpartum Follow-Up and Glucose Tolerance Testing in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Am J Perinatol 2018;35:354–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:1773–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lykke JA, Langhoff-Roos J, Sibai BM, Funai EF, Triche EW, Paidas MJ. Hypertensive pregnancy disorders and subsequent cardiovascular morbidity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the mother. Hypertension 2009;53:944–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cosson E, Bihan H, Vittaz L, et al. Improving postpartum glucose screening after gestational diabetes mellitus: a cohort study to evaluate the multicentre IMPACT initiative. Diabet Med 2015;32:189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGovern A, Butler L, Jones S, et al. Diabetes screening after gestational diabetes in England: a quantitative retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierce M, Modder J, Mortagy I, Springett A, Hughes H, Baldeweg S. Missed opportunities for diabetes prevention: post-pregnancy follow-up of women with gestational diabetes mellitus in England. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e611–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cabizuca CA, Rocha PS, Marques JV, et al. Postpartum follow up of gestational diabetes in a Tertiary Care Center. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2018;10:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nowik CM, Pudwell J, Smith GN. Evaluating the Postpartum Maternal Health Clinic: How Patient Characteristics Predict Follow-Up. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2016;38:930–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderberg E, Carlsson KS, Berntorp K. Use of healthcare resources after gestational diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal case-control analysis. Scand J Public Health 2012;40:385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernstein JA, McCloskey L, Gebel CM, Iverson RE, Lee-Parritz A. Lost opportunities to prevent early onset type 2 diabetes mellitus after a pregnancy complicated by gestational diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2016;4:e000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nielsen JH, Olesen CR, Kristiansen TM, Bak CK, Overgaard C. Reasons for women’s non-participation in follow-up screening after gestational diabetes. Women Birth 2015;28:e157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett WL, Ennen CS, Carrese JA, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of postpartum follow-up care in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: a qualitative study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:239–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oza-Frank R, Conrey E, Bouchard J, Shellhaas C, Weber MB. Healthcare Experiences of Low-Income Women with Prior Gestational Diabetes. Matern Child Health J 2018;22:1059–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zera CA, Nicklas JM, Levkoff SE, Seely EW. Diabetes risk perception in women with recent gestational diabetes: delivery to the postpartum visit. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;26:691–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Werner EF, Has P, Kanno L, Sullivan A, Clark MA. Barriers to Postpartum Glucose Testing in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Am J Perinatol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Martinez NG, Niznik CM, Yee LM. Optimizing postpartum care for the patient with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:314–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrick CJC,B, Keller M, Olsen M, Colditz G Screening for diabetes in high-risk women: Building the data infrastructure to study postpartum diabetes screening among low-income women with gestational diabetes. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2017;1:71–2. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Werner EF, Has P, Tarabulsi G, Lee J, Satin A. Early Postpartum Glucose Testing in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Am J Perinatol 2016;33:966–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]