Abstract

Background

Oral zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride (Clopixol) is an anti‐psychotic treatment for people with psychotic symptoms, especially those with schizophrenia. It is associated with neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a prolongation of the QTc interval, extra‐pyramidal reactions, venous thromboembolism and may modify insulin and glucose responses.

Objectives

To determine the effects of zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride for treatment of schizophrenia.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register (latest search 09 June 2015). There were no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records in the register.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) focusing on zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride for schizophrenia. We included trials meeting our inclusion criteria and reporting useable data.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data independently. For binary outcomes, we calculated risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI), on an intention‐to‐treat basis. For continuous data, we estimated the mean difference (MD) between groups and its 95% CI. We employed a random‐effect model for analyses. We assessed risk of bias for included studies and created 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADE.

Main results

We included 20 trials, randomising 1850 participants. Data were reported for 12 comparisons, predominantly for the short term (up to 12 weeks) and inpatient populations. Overall risk of bias for included studies was low to unclear.

Data were unavailable for many of our pre‐stated outcomes of interest. No data were available, across all comparisons, for death, duration of stay in hospital and general functioning.

Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride versus:

1. placebo

Movement disorders (EPSEs) were similar between groups (1 RCT, n = 28, RR 6.07 95% CI 0.86 to 43.04 very low‐quality evidence). There was no clear difference in numbers leaving the study early (2 RCTs, n = 100, RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.01 to 6.60, very low‐quality evidence).

2. chlorpromazine

No clear differences were found for the outcomes of global state (average CGI‐SI endpoint score) (1 RCT, n = 60, MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.49) or movement disorders (EPSEs) (3 RCTs, n = 199, RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.45), both very low‐quality evidence. More people left the study early for any reason from the zuclopenthixol group (6 RCTs, n = 766, RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.81, low‐quality evidence).

3. chlorprothixene

There was no clear difference in numbers leaving the study early for any reason (1 RCT, n = 20, RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.93, very low‐quality evidence).

4. clozapine

No useable data were presented.

5. haloperidol

No clear differences between treatment groups were found for the outcomes global state score (average CGI endpoint score) (1 RCT, n = 49, MD 0.13, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.55) or leaving the study early (2 RCTs, n = 141, RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.35), both very low‐quality evidence.

6. perphenazine

Those receiving zuclopenthixol were more likely to require medication in the short term for EPSEs than perphenazine (1 RCT, n = 50, RR 1.90, 95% CI 1.12 to 3.22, very low‐quality evidence). Similar numbers left the study early (2 RCTs, n = 104, RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.47, very low‐quality evidence).

7. risperidone

Those receiving zuclopenthixol were more likely to require medications for EPSEs than risperidone (1 RCT, n = 98,RR 1.92, 95% CI 1.12 to 3.28, very low quality evidence). There was no clear difference in numbers leaving the study early ( 3 RCTs, n = 154, RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.84 to 2.02) or in mental state (average PANSS total endpoint score) (1 RCT, n = 25, MD ‐3.20, 95% CI ‐7.71 to 1.31), both very low‐quality evidence).

8. sulpiride

No clear differences were found for global state (average CGI endpoint score) ( 1 RCT, n = 61, RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.49 to 2.85, very low‐quality evidence), requiring hypnotics/sedatives (1 RCT, n = 61, RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.32, very low‐quality evidence) or leaving the study early (1 RCT, n = 61, RR 2.07 95% CI 0.97 to 4.40, very low‐quality evidence).

9. thiothixene

No clear differences were found for the outcomes of 'global state (average CGI endpoint score) (1 RCT, n = 20, RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.46) or leaving the study early (1 RCT, n = 20, RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.35), both very low‐quality evidence).

10. trifluoperazine

No useable data were presented.

11. zuclopenthixol depot

There was no clear difference in numbers leaving the study early (1 RCT, n = 46, RR 1.95, 95% CI 0.36 to 10.58, very low‐quality evidence).

12. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride (cis z isomer) versus zuclopenthixol (cis z/trans e isomer)

There were no clear differences in reported side‐effects ( 1 RCT, n = 57, RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.18, very low‐quality evidence) and in numbers leaving the study early (4 RCTs, n = 140, RR 2.15, 95% CI 0.49 to 9.41, very low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride appears to cause more EPSEs than clozapine, risperidone or perphenazine, but there was no difference in EPSEs when compared to placebo or chlorpromazine. Similar numbers required hypnotics/sedatives when zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride was compared to sulpiride, and similar numbers of reported side‐effects were found when its isomers were compared. The other comparisons did not report adverse‐effect data.

Reported data indicate zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride demonstrates no difference in mental or global states compared to placebo, chlorpromazine, chlorprothixene, clozapine, haloperidol, perphenazine, sulpiride, thiothixene, trifluoperazine, depot and isomers. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride, when compared with risperidone, is favoured when assessed using the PANSS in the short term, but not in the medium term.

The data extracted from the included studies are mostly equivocal, and very low to low quality, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Prescribing practice is unlikely to change based on this meta‐analysis. Recommending any particular course of action about side‐effect medication other than monitoring, using rating scales and clinical assessment, and prescriptions on a case‐by‐case basis, is also not possible.

There is a need for further studies covering this topic with more antipsychotic comparisons for currently relevant outcomes.

Plain language summary

Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride for schizophrenia

Background

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness where people experience delusions (strange thoughts/ideas) and/or hallucinations (hearing or seeing things that are not real). These are often known as positive or acute symptoms. People also experience negative or chronic symptoms which usually follow acute symptoms. These can include withdrawing from social contact, lack of interest in everyday activities, depression as well as problems with memory and thought processing.

Treatment usually involves a package of care involving medications known as antipsychotics, and if necessary, additional therapies such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Psychoeducation or Occupational therapy.

There are many different antipsychotics available; knowing how effective each one is compared with no treatment or placebo (dummy treatment) and with other antipsychotics is important. This review compares the oral form of the antipsychotic zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride with other antipsychotics and placebo.

Searching for evidence

An electronic search was run on 9 June 2015, searching for trials that randomised people with schizophrenia into treatment groups that received either zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride or placebo or another antipsychotic.

Evidence found

The review authors found 20 trials with 1850 participants. Most of these participants were patients in psychiatric hospitals.

The trials compared oral zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride to placebo and nine other oral antipsychotics (chlorpromazine, chlorprothixene, clozapine, haloperidol, perphenazine, risperidone, sulpiride, thiothixene, and trifluoperazine). There were also trials that compared oral zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride with an injection of zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride and some that compared two different versions of zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride.

The review authors were interested in finding evidence for zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride's effect on seven main outcomes: global state, mental state, adverse effects, death, duration of stay in hospital, leaving the study early and general functioning. Unfortunately many data provided by the trials were unusable, data were available only for global state, mental state, leaving the study early and the adverse effect of movement disorders. The trials comparing zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride with sulpiride and trifluoperazine did not provide any useable data for any of these main outcomes.

Overall results suggest zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride's effect on global and mental state, and number of participants leaving the study early is similar to the other anti‐psychotics listed above.

Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride may cause more movement disorders than clozapine, risperidone or perphenazine, but there was no difference for the other drug comparisons or placebo.

Conclusions

The evidence currently available is of very low to low quality and the meaning is therefore unclear. Data for many important outcomes are not available making conclusions about overall effectiveness of zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride difficult.

Evidence available suggest that zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride is not any worse than other antipsychotics in treating the symptoms of schizophrenia, however more trials providing good‐quality data are needed before firm conclusions can be made.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia afflicts about 1% of the world's population across geographical, racial and gender barriers (Jablensky 1992).

It is characterised by distortions in thinking and perception in the context of inappropriate and/or blunted affects. It often includes the following psychopathological phenomena:

thought echo, thought insertion/withdrawal, thought broadcasting;

delusional perception and delusions of control, influence or passivity;

hallucinations (often auditory);

thought disorders;

negative symptoms.

The course of the illness can be continuous or episodic and outcomes are polymorphic (WHO 2010).

Description of the intervention

There is one oral preparation (marketed as Cisordinol, Clopixol) and two depot forms of zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride: zuclopenthixol acetate (Cisordinol‐Acutard, Clopixol‐Acuphase, Clopixol‐Acutard), and zuclopenthixol decanoate (Cisordinol depot, Clopixol depot, Clopixol Inj.). Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride (Clopixol tablets) was manufactured by Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals, licensed in 1982 and is currently approved for use in 71 countries.

How the intervention might work

Zuclopenthixol belongs to the class of thioxanthene derivatives. Zuclopenthixol is the cis (Z)‐isomer of clopenthixoland has a high affinity for both dopamine D1 and D2 receptors. It is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and maximum serum concentration occurs after about four hours following a single oral dose. The elimination half‐life is approximately 20 hours (range 12 to 28 hours). It has a moderately high pre‐systemic metabolism and about 40% of the drug is eliminated this way (Dollery 1999).

Why it is important to do this review

Antipsychotic medication remains a key means of treating people with schizophrenia (Awad 1997; Dally 1967). Since the introduction of chlorpromazine in the early 1950's numerous antipsychotic drugs have been developed. These include haloperidol, thioridazine, trifluoperazine and zuclopenthixol and they are now inexpensive and accessible to millions. Zuclopenthixol has been licensed since the early 1980's and is used in at least 71 countries including many European countries, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

A newer generation of so called 'atypical' antipsychotics have been developed and are increasingly prevalent for treating schizophrenia, especially in high‐income countries (Taylor 2000). This increase in the use of newer drugs is mirrored by a decline in the use of the older generation antipsychotics such as zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride although they are still used for treating schizophrenia and related psychotic conditions (Kozyrev 2003; Mace 2005; Percudani 2005). However, we have found it difficult to identify reviews on the effects of the oral preparation and we found no relevant meta‐analyses. This Cochrane review is the third review relevant to this compound and concentrates on the oral form of zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride. The first review investigated the effects of zuclopenthixol acetate for rapid tranquillisation of disturbed people with serious mental illnesses (Jayakody 2012), and the second concentrates on the decanoate preparation of zuclopenthixol as this is used as a long‐acting depot preparation (da Silva Freire Coutinho 1999).

Objectives

To determine the effects of zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride for the treatment of schizophrenia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials. Where a trial was described as 'double‐blind' but it was implied that the study was randomised, we included these trials in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see Types of outcome measures) when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then we included these in the final analysis. If there was a substantive difference, only clearly randomised trials were utilised and the results of the sensitivity analysis described in the text. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

We included people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like disorders such as schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder or schizoaffective disorder, diagnosed by any criteria. We also included those with 'serious/chronic mental illness' or 'psychotic illness'. Where possible we excluded people with dementia, depression and problems primarily associated with substance misuse.

Types of interventions

1. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride administered in oral form, any dose.

2. Placebo or no treatment.

3. Other antipsychotic drugs: any dose, administered in depot form.

4. Other antipsychotic drugs: any dose, administered in oral form.

Types of outcome measures

All outcomes were reported for the short term (up to 12 weeks), medium term (13 to 26 weeks), and long term (more than 26 weeks). None of the included studies went beyond one year.

Primary outcomes

1. Global state: average endpoint global state score

2. Adverse effects: clinically important general adverse effect

Secondary outcomes

1. Death ‐ suicide and natural causes

2. Global state

2. 1 Relapse 2. 2 Time to relapse 2. 3 Clinically important change in global state 2. 4 Any change in global state 2. 5 Average change in global state scores

3. Service outcomes

3. 1 Hospitalisation 3. 2 Time to hospitalisation 3. 3 Duration of stay in hospital

4. Mental state

4. 1 Clinically important change in general mental state 4. 2 Any change in general mental state 4. 3 Average endpoint general mental state score 4. 4 Average change in general mental state scores 4. 5 Clinically important change in specific symptoms 4. 6 Any change in specific symptoms 4. 7 Average endpoint specific symptom score 4. 8 Average change in specific symptom scores

5. Leaving the study early

5. 1 For specific reasons 5. 2 For general reasons

6. General functioning

6. 1 Clinically important change in general functioning 6. 2 Any change in general functioning 6. 3 Average endpoint general functioning score 6. 4 Average change in general functioning scores 6. 5 Clinically important change in specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills 6. 6 Any change in specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills 6. 7 Average endpoint specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills 6. 8 Average change in specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills

7. Behaviour

7. 1 Clinically important change in general behaviour 7. 2 Any change in general behaviour 7. 3 Average endpoint general behaviour score 7. 4 Average change in general behaviour scores 7. 5 Clinically important change in specific aspects of behaviour 7. 6 Any change in specific aspects of behaviour 7. 7 Average endpoint specific aspects of behaviour 7. 8 Average change in specific aspects of behaviour

8. Adverse effects

8. 1 Any general adverse effects 8. 2 Average endpoint general adverse effect score 8. 3 Average change in general adverse effect scores 8. 4 Clinically important change in specific adverse effects 8. 5 Any change in specific adverse effects 8. 6 Average endpoint specific adverse effects 8. 7 Average change in specific adverse effects

9. Engagement with services

9. 1 Clinically important engagement 9. 2 Not any engagement 9. 3 Average endpoint engagement score 9. 4 Average change in engagement scores

10. Satisfaction with treatment

10. 1 Recipient of care satisfied with treatment 10. 2 Recipient of care average satisfaction score 10. 3 Recipient of care average change in satisfaction scores 10. 4 Carer satisfied with treatment 10. 5 Carer average satisfaction score 10. 6 Carer average change in satisfaction scores

11. Quality of life

11. 1 No clinically important change in quality of life 11. 2 Not any change in quality of life 11. 3 Average endpoint quality of life score 11. 4 Average change in quality of life scores 11. 5 No clinically important change in specific aspects of quality of life 11. 6 Not any change in specific aspects of quality of life 11. 7 Average endpoint specific aspects of quality of life 11. 8 Average change in specific aspects of quality of life

12. Economic outcomes

12. 1 Direct costs 12. 2 Indirect costs

Summary of findings

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2011) and used the GRADE profiler to import data from Review Manager (RevMan) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient‐care and decision making.

We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 12 'Summary of findings' tables.

Global state: Average endpoint global state score (clinically improved) [primary outcome]

Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effect [primary outcome]

Death: Suicide and natural causes [secondary outcome]

Service outcome: Duration of stay in hospital [secondary outcome]

Mental state: Average endpoint general mental state score (clinically improved) [secondary outcome]

Leaving the study early: any reason [secondary outcome]

General functioning: Average endpoint general functioning score (clinically improved) [secondary outcome]

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register

On June 09, 2015, the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Study‐Based Register of Trials using the following search strategy which has been developed based on literature review and consulting with the authors of the review:

*Zuclopenthixol* in Intervention of STUDY

In such a study‐based register, searching the major concept retrieves all the relevant keywords and studies because all the studies have already been organised based on their interventions and linked to the relevant topics.

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Register of Trials is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group Module). There is no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

For previous searches, please see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected references of all included studies for further relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

Where necessary, we contacted the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials. We noted the outcome of this contact in the included or awaiting assessment studies tables.

Data collection and analysis

For previous data collection and analysis see Appendix 2.

Selection of studies

For this update, review author EJB independently inspected citations from the searches and identified relevant abstracts. A random 20% sample was independently re‐inspected by Dr Marie Ann Purcell (MAP) to ensure reliability. Where disputes arose, the full report was acquired for more detailed scrutiny. Full reports of the abstracts meeting the review criteria were obtained and inspected by EJB. Again, a random 20% of full reports were‐inspected by MAP in order to ensure reliable selection. Where it was not possible to resolve disagreement by discussion, we attempted to contact the authors of the study for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

For this update, review author EJB extracted data from all included studies. In addition, to ensure reliability, JX (see Acknowledgements) independently extracted data from a random sample of these studies, comprising 10% of the total. Again, any disagreements were discussed, decisions documented and, if necessary, authors of studies contacted for clarification. With remaining problems MAP helped clarify issues and these final decisions were documented. Data presented only in graphs and figures were to be extracted whenever possible, but included only if two review authors independently had the same result. We attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary. If studies were multi‐centre, where possible, we extracted data relevant to each component centre separately.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto simple standard forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: a) the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b) the measuring instrument has not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial. Ideally, the measuring instrument should either be i. a self‐report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly, in Description of studies we noted if this was the case or not.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint) which can be difficult in unstable and difficult to measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. Endpoint and change data were combined in the analysis as we used mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Higgins 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to all data before inclusion:

Please note, we entered data from studies of at least 200 participants, for example, in the analysis irrespective of the following rules, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies. We also entered change data as when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not. We presented and entered change data into the statistical analyses.

For endpoint data:

(a) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, we subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean, and divided this by the standard deviation (SD). If this value was lower than 1, it strongly suggests a skew and the study was excluded. If this ratio was higher than 1 but below 2, there is suggestion of skew. We entered the study and tested whether its inclusion or exclusion changed the results substantially. Finally, if the ratio was larger than 2, the study was included, because skew is less likely (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011).

b) if a scale starts from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay 1987), which can have values from 30 to 210), the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐S min), where S is the mean score and 'S min' is the minimum score.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005; Leucht 2005a). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicates a favourable outcome for Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride. Where keeping to this made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives, we reported data where the left of the line indicates an unfavourable outcome. This is noted in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Again, review author EJB worked independently to assess risk of bias by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess trial quality. This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. A random 20% was screened for validity independently by MAP.

If the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus, with the involvement of another member of the review group. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted the authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. We reported non‐concurrence in quality assessment , but if disputes arose as to which category a trial was to be allocated, again, we resolved this by discussion.

We noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome/number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTB/NNTH) statistic with its confidence intervals is intuitively attractive to clinicians but is problematic both in its accurate calculation in meta‐analyses and interpretation (Hutton 2009). For binary data presented in the 'Summary of findings' tableS, where possible, we calculated illustrative comparative risks.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated mean difference (MD) between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference (SMD)). However, if scales of very considerable similarity were used, we presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and we calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was be assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies was possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we only used data of the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, the additional treatment arms were presented in the comparisons. If data were binary, we simply added and combined them within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we combined data following the formula in section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not use these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not reproduce these data or use them within the analyses. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we addressed this within the 'Summary of findings' tables by down‐rating quality. Finally, we also downgraded quality within the 'Summary of findings' tables should loss be 25% to 50% in total.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis). Those leaving the study early were all assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes, the rate of those who stayed in the study ‐ in that particular arm of the trial ‐ were used for those who did not. We undertook a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when data only from people who completed the study to that point were compared to the ITT analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50%, and data only from people who completed the study to that point were reported, we reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations

If standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals available for group means, and either 'P' value or 't' value available for differences in mean, we could calculate them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011): When only the SE is reported, SDs are calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics. If these formulae did not apply, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We nevertheless examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Assumptions about participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up

Various methods are available to account for participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up. Some trials just present the results of study completers, others use the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF), while more recently methods such as multiple imputation or mixed‐effects models for repeated measurements (MMRM) have become more of a standard. While the latter methods seem to be somewhat better than LOCF (Leon 2006), we feel that the high percentage of participants leaving the studies early and differences in the reasons for leaving the studies early between groups is often the core problem in randomised schizophrenia trials. We therefore did not exclude studies based on the statistical approach used. However, preferably we used the more sophisticated approaches. For example, MMRM or multiple‐imputation were preferred to LOCF and completer analyses were only presented if some kind of ITT data were not available at all. Moreover, we addressed this issue in the item "incomplete outcome data" of the 'Risk of bias' tool.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations which we had not predicted would arise. When such situations or participant groups arose, we fully discussed these.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. When such methodological outliers arose, we fully discussed these.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 method alongside the Chi2 'P' value. The I2 provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. 'P' value from Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2). An I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic, was interpreted as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Section 9.5.2 ‐ Higgins 2011). When substantial levels of heterogeneity were found in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

1. Protocol versus full study

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We attempted to locate protocols of included randomised trials. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. If the protocol was not available, we compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with actually reported results.

2. Funnel plot

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). Again, these are described in Section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots were possible, we planned to seek statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies, even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model. It puts added weight onto small studies which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose a random‐effects model for all analyses. The reader is, however, able to choose to inspect the data using the fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

1.1 Primary outcomes

No subgroup analysis was expected.

1.2 Clinical state, stage or problem

We proposed to undertake this review and provide an overview of the effects of zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride for people with schizophrenia in general. In addition, however, we tried to report data on subgroups of people in the same clinical state, stage and with similar problems. This was not done in this update.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, this was reported. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, the graph was visually inspected and outlying studies were successively removed to see if homogeneity was restored. For this review we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, data were presented. If not, data were not pooled and issues discussed. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off but are investigating the use of prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity were obvious we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We do not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as to imply randomisation. For the primary outcomes, we included these studies and if there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies were added to those with better description of randomisation, then all data were employed from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption/s and when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing SDs data (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption/s and when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. A sensitivity analysis was undertaken to test how prone results were to change when completer‐only data only were compared to the imputed data using the above assumption. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

3. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that were judged to be at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains of randomisation (implied as randomised with no further details available) allocation concealment, blinding and outcome reporting for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcome. If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then data from these trials were included in the analysis.

4. Imputed values

We also undertook a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster‐randomised trials.

If substantial differences were noted in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we did not pool data from the excluded trials with the other trials contributing to the outcome, but presented them separately.

5. Fixed and random effects

We synthesised all data using a random‐effects model, however, we also synthesised data for the primary outcome using a fixed‐effect model to evaluate whether this altered the significance of the results.

Results

Description of studies

Accross all comparisons there was a significant lack of data for the primary outcomes and the secondary outcomes. The majority of data were for the short term only, for inpatient populations and focused on adverse effects. Most studies were small with the exception of Fischer‐Cornelssen 1976.

Results of the search

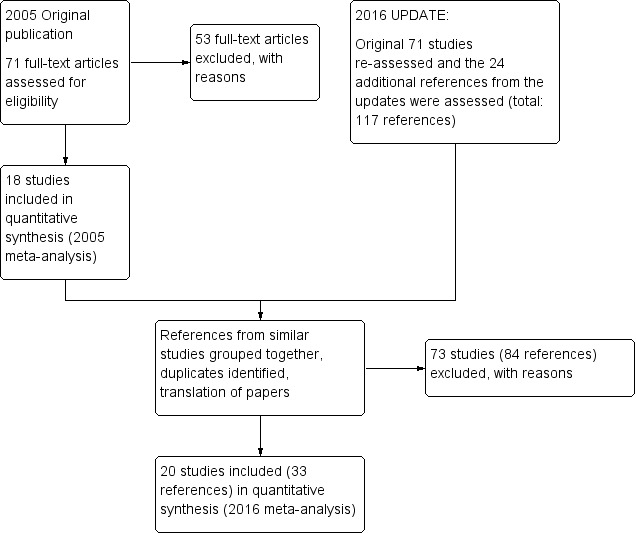

Details of the search results are illustrated in the PRISMA tableFigure 1

1.

Study flow diagram ‐ update 2016.

After obtaining the initial results of the search, removing duplicates and clearly irrelevant material, the original review authors inspected 79 abstracts. Out of these 79 papers, they selected 71 full‐text papers to be assessed for eligibility. The original authors then grouped these into 'studies' where several of the reports referred to the same trial. Fifty‐three articles were excluded with reasons and 18 studies were included in the 2005 meta‐analysis.

During the update we identified 117 potential reports for the review. We had to exclude 73 (84 reports) of these studies. So, at the end of this review update we have identified 33 reports of 20 trials for inclusion in the 2016 meta‐analysis. At the time of writing zero studies are awaiting assessment and we know of no ongoing studies at the time of writing.

Included studies

We identified 20 studies (from 33 references) spanning the period 1968 to 2008 covering 12 comparisons for inclusion in this update. Fifteen were described as randomised and in the remaining five, randomisation was implied. One trial was a cross‐over trial and one was an open‐label trial. Two authors need to be contacted for additional information at the next update (Arango 2006 and Fagerlund 2004). Ban 1975 data has been updated to reflect the two‐week washout period not originally included in the initial publication.

The trial authors were not always explicit in their descriptions of randomisation or blinding and an assumption of either or both was made based on implication and context of the discussions and/or data. The majority of the data were short term and from inpatient samples. The studies used relatively small cohorts with the exception of Fischer‐Cornelssen 1976.

Where authors published research from the same cohort in several different reports the data were pooled and used only once in the meta‐analysis. Some degree of interpretation on our part was required during this process.

Further information on the included studies can be obtained in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Excluded studies

We excluded 73 studies: two had healthy volunteers, 42 used the wrong intervention (predominantly depot), four used the wrong type of participant, eight were not randomised, 16 did not have any useable data (either data that could be extracted for meta‐analysis or no data provided), and one duplicated data from elsewhere. Galdersi 1994 was originally included but excluded in this update because it was not a randomised trial.

Further information on the excluded studies can be obtained in theCharacteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Most information is from studies at low or unclear risk of bias. It is difficult to provide a generalised assessment of the risk of bias given the low number of studies in this update. We would advise reviewing the 'Risk of bias' tables in the Characteristics of included studies table of the review.

Risk of bias overall: Unclear.

Allocation

Three studies were graded as low risk, 16 as unclear risk and one as high risk. All included studies were randomised or had implied randomisation. Most of the included studies did not explicitly describe the method by which randomisation was done.The majority of patients came from inpatient samples and there was a degree of diagnostic purity to the samples. Review of demographic tables (where published) indicated a roughly equal spread between different arms within the different studies.

Overall risk of selection bias: unclear.

Blinding

Thirteen studies were graded as low risk, four as unclear risk and three as high risk. Two of the studies were open‐label and all included studies used some form of established rating scale or modified rating scale to measure changes in global state, adverse effects and mental state. Several of the papers were vague on their methods for blinding, but it was generally implied in the majority. Only a few papers explicitly stated that blinding was conducted and this was usually mentioned in the title and/or abstract.

Overall risk of performance/detection bias: low risk.

Incomplete outcome data

Nine studies were graded as low risk, five as unclear risk and six as high risk. Reasons for loss to follow‐up are well‐reported and we have recorded these in the outcomes. Most studies, however, have not clearly described how they used data for people who were lost to follow‐up and we found no reporting of attempts to validate any assumptions by following up those who dropped out early. Per‐protocol analysis was used in eight studies.

Overall risk of attrition bias: low risk.

Selective reporting

Five studies were graded as low risk, five as unclear risk and 10 as high risk. Overall, due to poor reporting, we were unable to use a lot of the data (missing data were detected in nine of the studies). Findings presented as graphs, whether as percentiles or as inexact P values, are often of little use to a reviewer. Many studies failed to provide standard deviations when reporting mean changes. Three of the studies published the same data in multiple locations. One study presented its data inaccurately requiring EJB to make a professional judgement on what the authors intended.

Overall risk of reporting bias: high risk.

Other potential sources of bias

Two studies were graded as low risk, two as unclear risk and 16 as high risk. The predominant biases in this category are: response bias, instrument bias, interviewer bias and the Hawthorne effect. The authors of the included studies did not discuss these biases in any detail, if at all.

Overall risk of other bias: high risk.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9; Table 10; Table 11; Table 12

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride versus placebo.

| Patient or population: people with schizophrenia Setting: Hospital Intervention: ZUCLOPENTHIXOL Comparison: PLACEBO (short term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with PLACEBO (short term) | Risk with ZUCLOPENTHIXOL | |||||

| Global state: Average endpoint global state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effect (extrapyramidal effects ‐ UKU side effect rating scale) | 80 per 1000 | 486 per 1000 (69 to 1000) | RR 6.07 (0.86 to 43.04) | 28 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2, 3,4, 5, 6 | Risk assumed to be moderate and rounded from 7.69% to 8%. |

| Death: Suicide and natural causes (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Service outcomes: Duration of stay in hospital (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Mental state: Average endpoint general mental state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Leaving the study early (any reason) | 40 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (0 to 264) | RR 0.29 (0.01 to 6.60) | 100 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 6 | Risk assumed to be moderate and rounded from 3.85% to 4%. Low number of events in both RCTs. |

| General functioning: Average endpoint general functioning score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ possible selection bias, blinding may have been single, attrition bias and reporting bias.

2 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ selection, attrition and reporting bias

3 Risk of inconsistency: rated 'not serious' ‐ suspected but not found.

4 Risk of publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ multiple papers published with the same patient cohort.

5 Risk of large effect: rated 'very large' ‐ RR 6.07, small n number but result likely when versus placebo.

6 Risk of imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ low n numbers

Summary of findings 2. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride versus chlorpromazine.

| Patient or population: schizophrenia Setting: Outpatient and inpatient (predominantly hospitalised) Intervention: ZUCLOPENTHIXOL Comparison: CHLORPROMAZINE (short term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with CHLORPROMAZINE (short term) | Risk with ZUCLOPENTHIXOL | |||||

| Global state: Average endpoint global state score (clinically improved) (CGI‐SI, high score not reported, average score = 2.2) | The mean CGI‐SI endpoint score in the intervention group (MD) was 0 (‐0.49 lower to 0.49 higher) | ‐ | 64 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 5 | Translated study. | |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effect (EPSEs) | 300 per 1000 | 282 per 1000 (183 to 435) | RR 0.94 (0.61 to 1.45) | 199 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 4 5 6 | Risk control rounded to 30% and set to moderate. Mixture of inpatient and outpatient, though predominantly hospitalised patients. |

| Death: Suicide and natural causes (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Service outcomes: duration of stay in hospital (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Mental state: Average endpoint general mental state score (clinically improved) (BPRS, high score = 34.2) | The mean mental state: average endpoint score (BPRS, high score = 34.2) in the intervention group was 0.4 more (2.43 fewer to 3.23 more) | ‐ | 221 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 6 | Mixture of inpatient and outpatient, though predominantly hospitalised patients. | |

| Leaving the study early (any reason) | 70 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (25 to 57) | RR 0.54 (0.36 to 0.81) | 766 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 6 | Mixture of inpatient and outpatient, though predominantly hospitalised patients. Risk control set to moderate and rounded to 7%; extreme values not likely. |

| General functioning: Average endpoint general functioning score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ Selection and attrition bias likely.

2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ Selection attrition bias.

3 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ Selection, attrition and reporting bias.

4 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ Selection, attrition and reporting bias. Risk of inconsistency: rated as 'serious' ‐ All three papers reported on differing population sizes and obtained different levels of EPSEs in the experimental and control groups.

5 Risk of imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ low n numbers

6 Risk of indirectness: rated 'very serious' ‐ mixed samples

For risks rated as serious, we downgraded by 1.

For risks rated as very serious we downgraded by 2.

Summary of findings 3. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride versus chlorprothixene.

| Patient or population: schizophrenia Setting: Hospital Intervention: ZUCLOPENTHIXOL Comparison: CHLORPROTHIXENE (medium term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with CHLORPROTHIXENE (medium term) | Risk with ZUCLOPENTHIXOL | |||||

| Global state: Average endpoint global state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effect (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Death: Suicide and natural causes (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Service outcomes: duration of stay in hospital (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Mental state: Average endpoint general mental state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Leaving the study early (any reason) | 400 per 1000 | 400 per 1000 (136 to 1000) | RR 1.00 (0.34 to 2.93) | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | |

| General functioning: Average endpoint general functioning score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated as 'serious' ‐ selection, reporting bias likely.

2 Risk of publication bias: rated as 'strongly suspected' ‐ several papers published using the same cohort of patients.

3 Risk of imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ low n numbers

For risks rated as serious, we downgraded by 1.

For risks rated as very serious we downgraded by 2.

Summary of findings 4. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride versus clozapine.

| Patient or population: schizophrenia Setting: Hospital Intervention: ZUCLOPENTHIXOL Comparison: CLOZAPINE (short term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with CLOZAPINE (short term) | Risk with ZUCLOPENTHIXOL | |||||

| Global state: Average endpoint global state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effect (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Death: Suicide and natural causes (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Service outcomes: duration of stay in hospital (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Mental state: Average endpoint general mental state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Leaving the study early (any reason) | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | not estimable | 407 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Multi‐centre, multi‐drug trial with disproportionate numbers of people in different arms of the study. The authors did not report that anybody left the study in the Zuclopenthixol and clozapine arms. |

| General functioning: Average endpoint general functioning score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated as 'serious' ‐ selection, attrition, reporting and performance bias likely.

2 Risk of indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ Multiple study arms

For risks rated as serious, we downgraded by 1.

For risks rated as very serious we downgraded by 2.

Summary of findings 5. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride versus haloperidol.

| Patient or population: schizophrenia Setting: Hospital only. Intervention: ZUCLOPENTHIXOL Comparison: HALOPERIDOL (short term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with HALOPERIDOL (short term) | Risk with ZUCLOPENTHIXOL | |||||

| Global state: Average endpoint global state score (clinically improved) (CGI, mean score = 1.25) | The mean CGI endpoint score in the intervention group (MD) was 0.13 more (‐0.3 fewer to 0.55 more) | ‐ | 49 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 4 | Small study, multiple scales used (NOSIE30, BPRS, CGI). Paper only reported outcomes of some of these scales. | |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effect (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No study reported this outcome. | |

| Death: Suicide and natural causes (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No study reported this outcome. | |

| Service outcomes: duration of stay in hospital (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No study reported this outcome. | |

| Mental state: Average endpoint general mental state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No study reported this outcome. | |

| Leaving the study early (any reason) | 300 per 1000 | 297 per 1000 (216 to 405) | RR 0.99 (0.72 to 1.35) | 141 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 4 | Risk control rounded to 30% from 29.25% and, as extreme values unlikely, it was set to moderate. |

| General functioning: Average endpoint general functioning score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No study reported this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated as 'very serious' ‐ likely selection, attrition, reporting and diagnostic purity bias.

2 Risk of bias: rated as 'serious' ‐ likely selection, attrition, reporting and diagnostic purity bias. Risk of inconsistency: rated as 'serious' ‐ both papers generated differing values for people leaving the study and do not appear consistent (face validity).

3 Risk of imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ low n numbers

4 Risk of indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ not all scales reported

For risks rated as serious, we downgraded by 1.

For risks rated as very serious we downgraded by 2.

Summary of findings 6. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride versus perphenazine.

| Patient or population: schizophrenia Setting: Hospital Intervention: ZUCLOPENTHIXOL Comparison: PERPHENAZINE (short and medium term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with PERPHENAZINE (short and medium term) | Risk with ZUCLOPENTHIXOL | |||||

| Global state: Average endpoint global state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No study reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effect (EPSEs requiring medication ‐ medium term) | 400 per 1000 | 760 per 1000 (448 to 1000) | RR 1.90 (1.12 to 3.22) | 50 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | |

| Death: Suicide and natural causes (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No study reported this outcome. | |

| Service outcomes: duration of stay in hospital (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No study reported this outcome. | |

| Mental state: Average endpoint general mental state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No study reported this outcome. | |

| Leaving the study early (any reason, short and medium term) | 207 per 1000 | 130 per 1000 (56 to 304) | RR 0.63 (0.27 to 1.47) | 104 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | |

| General functioning: Average endpoint general functioning score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No study reported this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated as 'serious' ‐ likely selection and reporting bias.

2 Risk of imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ low n numbers

For risks rated as serious, we downgraded by 1.

For risks rated as very serious we downgraded by 2.

Summary of findings 7. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride versus risperidone.

| Patient or population: schizophrenia Setting: Mostly hospital. Huttunen group did not state Intervention: ZUCLOPENTHIXOL Comparison: RISPERIDONE (short and medium term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with RISPERIDONE (short and medium term) | Risk with ZUCLOPENTHIXOL | |||||

| Global state: Average endpoint global state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effect ‐ short term (EPSEs requiring medication) | 271 per 1000 | 520 per 1000 (303 to 888) | RR 1.92 (1.12 to 3.28) | 98 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 5 6 | |

| Death: Suicide and natural causes (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Service outcomes: duration of stay in hospital (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Mental state: Average endpoint general mental state score (clinically improved) (PANSS, average score = 20.5) ‐ medium term | The mean PANNS endpoint score in the intervention group (MD) was 3.2 fewer (‐7.71 fewer to 1.31 more) | ‐ | 25 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | Small study. Standard deviations may be standard errors. Open label trial. | |

| Leaving the study early (any reason, short and medium term) | 310 per 1000 | 403 per 1000 (260 to 626) | RR 1.30 (0.84 to 2.02) | 154 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3 4 | Risk control taken as mean of extremes: high + low / 2 (changed from 21.43% to 31%) |

| General functioning: Average endpoint general functioning score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated as 'very serious' ‐ open label trial, likely selection bias.

2 Risk of imprecision: rated as 'very serious' ‐ strongly suspect reported standard deviations are standard errors, low n numbers

3 Risk of publication bias: rated as 'strongly suspected' ‐ all studies published findings across several consecutive years in different journals and at conferences.

4 Risk of bias: rated as 'very serious' ‐ study 1 (selection, reporting, diagnostic purity and attrition bias likely ‐ author emailed); study 2 (open label); study 3 (reporting and attrition bias).

5 Risk of publication bias: rated as 'strongly suspected' ‐ multiple papers over consecutive years published with the same data.

6 Risk of bias: rated as 'serious' ‐ diagnostic purity and attrition bias; likely selection and reporting bias (authors contacted)

For risks rated as serious, we downgraded by 1.

For risks rated as very serious we downgraded by 2.

Summary of findings 8. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride versus sulpiride.

| Patient or population: schizophrenia Setting: Not specified in study. Intervention: ZUCLOPENTHIXOL Comparison: SULPIRIDE (short term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with SULPIRIDE (short term) | Risk with ZUCLOPENTHIXOL | |||||

| Global state: Average endpoint global state score (clinically improved) (CGI ‐ unchanged/worse) | 226 per 1000 | 266 per 1000 (111 to 644) | RR 1.18 (0.49 to 2.85) | 61 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | The study did not report clinical improvement so unchanged/worse is reported for this outcome. Usually we report clinical improvement. |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effect ‐ requiring hypnotics/sedatives | 419 per 1000 | 252 per 1000 (113 to 554) | RR 0.60 (0.27 to 1.32) | 61 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | |

| Death: Suicide and natural causes (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Service outcomes: duration of stay in hospital (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| Mental state: Average endpoint general mental state score (clinically improved) (BPRS) | The mean BPRS endpoint score in the intervention group (MD) was 1.3 fewer (‐5.08 fewer to 2.48 more) | ‐ | 61 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| Leaving the study early (any reason) | 230 per 1000 | 476 per 1000 (223 to 1000) | RR 2.07 (0.97 to 4.40) | 61 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | Control of risk rounded up from 22.58% to 23%. |

| General functioning: Average endpoint general functioning score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated as 'serious' ‐ diagnostic purity, attrition bias. Per‐Protocol analysis suspected.

2 Risk of imprecision: rated as ' very serious' ‐ percentages used to describe data and comparisons are made against an assumption of baseline measurements. Low n numbers.

For risks rated as serious, we downgraded by 1.

For risks rated as very serious we downgraded by 2.

Summary of findings 9. Zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride versus thiothixene.

| Patient or population: schizophrenia Setting: hospital Intervention: ZUCLOPENTHIXOL Comparison: THIOTHIXENE (medium term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with THIOTHIXENE (medium term) | Risk with ZUCLOPENTHIXOL | |||||

| Global state: Average endpoint global state score (clinically improved) (unchanged/worse ‐ CGI) | 600 per 1000 | 300 per 1000 (102 to 876) | RR 0.50 (0.17 to 1.46) | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | The study did not report clinical improvement so unchanged/worse is reported for this outcome. Usually we report clinical improvement. |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effect (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported on this outcome. | |

| Death: Suicide and natural causes (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported on this outcome. | |

| Service outcomes: duration of stay in hospital (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported on this outcome. | |

| Mental state: Average endpoint general mental state score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported on this outcome. | |

| Leaving the study early (any reason) | 700 per 1000 | 399 per 1000 (168 to 945) | RR 0.57 (0.24 to 1.35) | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | |

| General functioning: Average endpoint general functioning score (clinically improved) (no data) | not pooled | not pooled | not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported on this outcome. | |