Abstract

Background

There is evidence that family and friends influence children's decisions to smoke.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of interventions to help families stop children starting smoking.

Search methods

We searched 14 electronic bibliographic databases, including the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group specialized register, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL unpublished material, and key articles' reference lists. We performed free‐text internet searches and targeted searches of appropriate websites, and hand‐searched key journals not available electronically. We consulted authors and experts in the field. The most recent search was 3 April 2014. There were no date or language limitations.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions with children (aged 5‐12) or adolescents (aged 13‐18) and families to deter tobacco use. The primary outcome was the effect of the intervention on the smoking status of children who reported no use of tobacco at baseline. Included trials had to report outcomes measured at least six months from the start of the intervention.

Data collection and analysis

We reviewed all potentially relevant citations and retrieved the full text to determine whether the study was an RCT and matched our inclusion criteria. Two authors independently extracted study data for each RCT and assessed them for risk of bias. We pooled risk ratios using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed effect model.

Main results

Twenty‐seven RCTs were included. The interventions were very heterogeneous in the components of the family intervention, the other risk behaviours targeted alongside tobacco, the age of children at baseline and the length of follow‐up. Two interventions were tested by two RCTs, one was tested by three RCTs and the remaining 20 distinct interventions were tested only by one RCT. Twenty‐three interventions were tested in the USA, two in Europe, one in Australia and one in India.

The control conditions fell into two main groups: no intervention or usual care; or school‐based interventions provided to all participants. These two groups of studies were considered separately.

Most studies had a judgement of 'unclear' for at least one risk of bias criteria, so the quality of evidence was downgraded to moderate. Although there was heterogeneity between studies there was little evidence of statistical heterogeneity in the results. We were unable to extract data from all studies in a format that allowed inclusion in a meta‐analysis.

There was moderate quality evidence family‐based interventions had a positive impact on preventing smoking when compared to a no intervention control. Nine studies (4810 participants) reporting smoking uptake amongst baseline non‐smokers could be pooled, but eight studies with about 5000 participants could not be pooled because of insufficient data. The pooled estimate detected a significant reduction in smoking behaviour in the intervention arms (risk ratio [RR] 0.76, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.68 to 0.84). Most of these studies used intensive interventions. Estimates for the medium and low intensity subgroups were similar but confidence intervals were wide. Two studies in which some of the 4487 participants already had smoking experience at baseline did not detect evidence of effect (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.17).

Eight RCTs compared a combined family plus school intervention to a school intervention only. Of the three studies with data, two RCTS with outcomes for 2301 baseline never smokers detected evidence of an effect (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.96) and one study with data for 1096 participants not restricted to never users at baseline also detected a benefit (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.94). The other five studies with about 18,500 participants did not report data in a format allowing meta‐analysis. One RCT also compared a family intervention to a school 'good behaviour' intervention and did not detect a difference between the two types of programme (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.38, n = 388).

No studies identified any adverse effects of intervention.

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate quality evidence to suggest that family‐based interventions can have a positive effect on preventing children and adolescents from starting to smoke. There were more studies of high intensity programmes compared to a control group receiving no intervention, than there were for other compairsons. The evidence is therefore strongest for high intensity programmes used independently of school interventions. Programmes typically addressed family functioning, and were introduced when children were between 11 and 14 years old. Based on this moderate quality evidence a family intervention might reduce uptake or experimentation with smoking by between 16 and 32%. However, these findings should be interpreted cautiously because effect estimates could not include data from all studies. Our interpretation is that the common feature of the effective high intensity interventions was encouraging authoritative parenting (which is usually defined as showing strong interest in and care for the adolescent, often with rule setting). This is different from authoritarian parenting (do as I say) or neglectful or unsupervised parenting.

Keywords: Adolescent, Child, Humans, Family, Smoking Prevention, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Smoking, Smoking/psychology

Plain language summary

Do interventions in families prevent children and adolescents from starting to smoke

Review question: This review asks whether family interventions can influence children and adolescents not to smoke, compared to no‐intervention controls or as an add‐on to a school intervention. We particularly focused on children who had never smoked.

Background: Preventing children from starting to smoke is important to avoid a lifetime of addiction, poor health, and social and economic consequences. Family members influence whether children and adolescents smoke. We wanted to know if there is enough evidence to justify funding interventions in families to prevent children starting smoking.

Last search: April 2014.

Study Characteristics: We identified 27 trials; 23 in the USA and one each in Australia, India, the Netherlands, and Norway. The focus varied amongst the studies. Fifteen trials focused on substance use prevention: six focused only on tobacco prevention; one focused on alcohol; one on general substance abuse; three on tobacco, alcohol and marijuana; two on alcohol and tobacco; and two on tobacco and cardiovascular health. Two trials focused on HIV and unsafe sex prevention. Ten trials focused on family functioning, child development and modifying adolescent behaviour. Duration of follow‐up after the intervention was very varied, ranging from 6 months to over 15 years for the studies which intervened with mothers of very young children.

Key Results: Nine trials provided data to compare a family tobacco intervention to no intervention on future smoking behaviour for those who did not smoke at the start of the study. We could not include data from a further eight trials. The results showed a significant benefit of family‐based interventions over the control comparison on preventing experimentation with or taking up regular smoking. Our estimate suggested that family interventions could reduce the number of adolescents who tried smoking at all by between 16 and 32%.

Two trials provided data to compare a combined family plus school intervention to a school intervention and also favoured the family‐based intervention. The estimate suggested that the addition of a family intervention might reduce the onset of smoking by between 4 and 25%. We could not include data from a further five trials.

Our interpretation is that the common feature of the effective interventions was encouraging authoritative parenting (which is usually defined as showing strong interest in and care for the adolescent, often with rule setting). This is different from authoritarian parenting (do as I say) or neglectful or unsupervised parenting.

Quality of the Evidence: Because most of the randomised controlled trials included in the review did not report their methods in sufficient detail to be confident that the results were not biased, we judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate, which means that the estimate of effect is uncertain.

Conclusions: There is moderate quality evidence that family‐based interventions can prevent children and adolescents from starting to smoke. Intensive programs may be more likely to be successful than those of lower intensity. There is also evidence to suggest that adding a family‐based component to a school intervention may be effective. As the interventions and settings in the review differed considerably, it is important that family‐based programmes continue to be evaluated.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Family interventions compared to no intervention.

| Family interventions for preventing smoking by children and adolescents | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Children or adolescents at risk for smoking uptake

Intervention: Family intervention Comparison: No intervention control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Family intervention versus non intervention control group | |||||

| New smoking at follow‐up. Baseline never smokers only | Study population | RR 0.76 (0.68 to 0.84)1 | 48102 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity despite clinical heterogeneity in the characteristics and focus of the interventions, the age range targeted and the duration of follow‐up | |

| 230 per 1000 | 174 per 1000 (156 to 193) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

* Assumed risk based on average for control group participants reached at follow‐up. There was large variation between studies in the rate of new smoking behaviour.

1 RR <1 favours family intervention. 2 Eight studies with about 5,000 participants did not present data in a format that could be used in meta‐analysis. 3 Most studies have low or unclear risk of bias. Downgraded one level.

Summary of findings 2. Family and school intervention compared to school intervention.

| Family and school intervention compared to school intervention only for preventing smoking by children and adolescents | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Children or adolescents at risk for smoking uptake

Intervention: Family intervention in addition to school intervention Comparison: School intervention only | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| School intervention | Family and school intervention | |||||

| New smoking at follow‐up. Baseline never smokers only | 230 per 1000 | 196 per 1000 (172 to 221) | RR 0.85 (0.75 to 0.96)1 | 23012 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

* Assumed risk based on same average for control group participants reached at follow‐up as used in Analysis 1. There was large variation between studies in the rate of new smoking behaviour.

1 RR <1 favours family intervention.

2 Five studies with approximately 18,500 participants did not present data in a format that could be used in meta‐analysis, so estimate does not reflect all the evidence. 3 Most studies have low or unclear risk of bias. Downgraded one level.

Background

Tobacco use is the main preventable cause of death and disease worldwide, and the five million deaths annually attributable to tobacco use are predicted to increase to eight million annually by 2030 (Warren 2009). Smoking in adolescence continues to rise in many countries, with 23% of American high school students smoking in 2000, up from 18.5% in 1991 (Johnston 2000). Adult smoking begins in adolescence: in US studies 89% of adult smokers began regular tobacco use by the age of 18 (Bricker 2003). If poorer countries follow the trajectory of the more affluent countries, it is to be expected that 20% to 30% of 13 to 15 year olds may smoke, depending on the culture of the country and the activities of the tobacco companies (Warren 2009). Intervening to prevent smoking uptake during adolescence is critical to slowing or halting the trend towards increased tobacco‐related illness (USDHHS 1994).

A number of reviews, surveys and cohort studies have identified three broad classes of influences for smoking in adolescence: individual characteristics (e.g. gender, concerns with body weight, attitudes to smoking), family factors (parental smoking, number of smokers in the family, parental permissiveness and approval) and peer‐group or friends (number who smoke, academic expectations by friends) (Mayhew 2000). Ethnicity (Proescholdbell 2000), levels of affluence (Jarvis 1997) and level of education also affect smoking, with tertiary education being associated with lower rates of smoking (Chassin 1984; Chassin 1996). In a long‐term cohort study, Jarvis 1997 found that as adolescent smokers moved into young adulthood they were more likely to quit if they assumed adult responsibilities such as marriage and employment.

Parental behaviour also emerges as a significant determinant of adolescent smoking in a number of studies (Mounts 2002). A cohort study nested within the Hutchinson Smoking Prevention Project (Bricker 2003) found that the children of parents who had never smoked were the least likely to smoke (odds reduced by 71% compared with both parents currently smoking), while children of parents who had quit smoking also had reduced odds of smoking themselves (reduced by 39%). Several studies reported that parental advice not to smoke or explicit disapproval of smoking could be effective in young teens (Eisner 1989; Huver 2007; Krosnick 1982; Newman 1989) and in unmarried pregnant teenagers (Hussey 1992). Parenting style and parental restrictions on smoking at home also appeared to have an impact, with permissive home policies increasing the likelihood of experimentation, while authoritative parenting (combining demanding and responsive management of children's behaviour) was the least likely to prompt uptake of smoking (Jackson 1998; Proescholdbell 2000). The influence of friends and peers has also been shown to be associated with smoking behaviour (Krosnick 1982; Simons‐Morton 2002), but smoking uptake is negatively related to perceived social competence and parental monitoring. Smoking is associated with other risk behaviours (DuRant 1999).

There are some non‐modifiable family characteristics that affect the likelihood of smoking. Living in an intact two‐parent family is associated with less smoking by children (Botvin 1993: Covey 1990; Isohanni 1991; Turner 1991) while parental socio‐economic status and education are generally inversely correlated with children's smoking (Tyas 1998). However, Darling 2003 has pointed out that the focus of the literature on predicting the risk of adolescent smoking (which is a continuous process of change) from stable family characteristics such as structure may be one reason why understanding of the developmental processes involved in tobacco initiation is limited.

Further background and theoretical issues concerning adolescent smoking initiation are covered in a companion review of school‐based interventions (Thomas 2013). A Cochrane review of smoking prevention for Indigenous youth identified only two RCTs (Carson 2012). There are also Cochrane reviews of community interventions (Carson 2011) and mentoring to prevent adolescents smoking (Thomas 2011).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of interventions to help family members to strengthen non‐smoking attitudes and promote non‐smoking by children or adolescents or their family members.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were included in which students and/or family members were randomised to receive interventions or be in the control group, and were excluded if they did not state that allocation to intervention and control groups was randomised. We assessed whether studies used analytic methods appropriate to both the level of allocation and the level of measurement of the outcomes. We excluded those studies that presented only cross‐sectional data that permitted neither individuals nor clusters nor cohorts to be followed to the conclusion of the study.

Types of participants

Children (aged 5 to 12) and adolescents (aged 13 to 18) and family members. The search strategy chosen also located studies that follow these children beyond age 18.

Types of interventions

Interventions with children and family members intended to deter starting to use tobacco. Those with school‐ or community‐based components were included provided the effect of the family‐based intervention could clearly be measured and separated from the wider school‐ or community‐based interventions. Interventions that focused on preventing drug or alcohol use were included if outcomes for tobacco use were reported. The family‐based intervention could include any components to change parenting behaviour, parental or sibling smoking behaviour, or family communication and interaction.

For each study we determined whether during the study the participants received any co‐interventions such as the standard health or tobacco education curriculum taught in the school, or interventions that occurred in their community, and whether the control group received any interventions.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome was the effect of the intervention on the smoking status of children who reported no use of tobacco at baseline.

We excluded studies that:

did not assess baseline smoking status in the pre‐test survey;

measured attitudes and intentions to smoke, and did not measure smoking behaviour;

did not allow us to separate the effects of the family intervention from those of other co‐interventions;

focused primarily on cessation rather than prevention; and

did not follow up participants for at least six months from the start of the intervention.

Any measure of smoking behaviour was considered. Studies may use different measures of tobacco use, either frequency (monthly, weekly, daily), or the number of cigarettes smoked, or an index constructed from multiple measures. These measures attempt to capture the trajectories of smoking uptake in which there is a progression from initial experimentation (e.g., once a month in a younger child) to becoming a regular smoker. Not all experimenters make the transition to regular smoking, and interventions that reduce the likelihood of progression may be as useful as those that deter any experimentation. Previous reviews have noted that few studies use biochemical validation (by saliva thiocyanate or cotinine or expired air carbon monoxide levels) of self‐reported tobacco use for inclusion, and we did not require such validation here but recorded its use.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register (compiled by regular searching of electronic databases and specialist conference proceedings), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). We performed ad hoc searches of the main electronic databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, and ERIC. The MEDLINE search terms are given as an example in Appendix 1. We also searched the 'grey' literature (unpublished reports and conference proceedings), the web sites of relevant organizations, and the reference lists of key articles. Full details of the databases and websites searched are given in Appendix 2. The most recent search was performed on 3 April 2014. At the time of the search the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 3, 2014; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20140321; EMBASE (via OVID) to week 201413; and PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20140317. See the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library for full search strategies and list of other resources searched.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We reviewed all the studies retrieved from the literature searches to determine whether they were RCTs, and whether they matched our inclusion criteria. Details of those studies which did not meet the criteria are given in the Table of Excluded Studies, with the reasons for their exclusion.

Data extraction and management

One reviewer (RET) extracted data from the included studies, and the other reviewers (BCT, PB, DLL) independently checked them. We corresponded with authors to clarify study details. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus. The Co‐ordinating Editor of the Tobacco Addiction Group was available to assist with persistent disagreements.

After entering the studies in the Included Studies Table we noted they varied greatly in intensity. Programe intensity was measured using four dimensions (Baker 2015) and rated High, Medium or Low: Proximity: local [H] – personal (on site, in‐home, face‐to‐face); distant [L] (e.g. mailing, telephone); Direction: programme directed [H] (with consistent prompts and contact, accountability to participate and engage), self‐directed [L] (up to the individual to work through the materials); Exposure period: duration of provision of the intervention and number of components; Unit of delivery: to family in groups [H], individual families [H] or community [L]. Two other aspects were considered: Cost per family to deliver the programme, and Authors' description of intensity, but data were rarely provided. Summary judgments were independently made whether the intervention was high, medium, or low intensity.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Studies were independently assessed by RET, BCT, PB, and DLL for sources of bias that the Cochrane Collaboration Reviewers' Handbook identifies as potential threats to validity.

We also assessed three statistical criteria:

A reported power calculation with attainment of the desired sample size. If a non‐significant result is obtained it may be due either to inadequate sample size or a be a true negative result.

The statistical analysis was deemed appropriate to the unit of randomisation for the family intervention. Intra‐class correlations (ICCs) in smoking behaviour vary by group, school grade, frequency of smoking, gender, ethnicity, and time of school year. ICCs typically inflate the required sample size, and failure to take account of these may lead to inadequate sample size and the risk of drawing false negative conclusions (Type II error) (Dielman 1994; Murray 1990; Murray 1997; Palmer 1998). We considered statistical analysis to be appropriate if the analysis used the same unit as randomisation (for example, if the family intervention was delivered at the level of the school then the school was the unit of analysis), or if other methods were used to account for cluster effects, such as multi‐level modelling.

An intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Data synthesis

Data were extracted from randomised controlled trials that reported smoking prevention (number or percentage of non‐smoking children at baseline that remained non‐smokers at follow‐up) and a minimum follow‐up time of six months. The outcomes used were the proportion prevented from smoking and we used the longest available follow‐up time for the analysis and computed risk ratios. Adjusted risk ratios from cluster‐randomised trials were obtained directly from those trials that reported them. If there is a large degree of heterogeneity in study design, type of outcome measure and statistical reporting, quantitative synthesis is not appropriate. Where trials could be pooled we estimated the effects using a fixed effect (Mantel‐Haenszel) model.

Results

Description of studies

Twenty‐seven trials met the inclusion criteria, of which 12 were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and 15 were cluster RCTs (C‐RCTs). We identified eight new trials for this update. Full details of included studies are given in the Characteristics of included studies table. We excluded three previously included studies; Knutsen 1991 was excluded as there were no baseline smoking data for children; Nutbeam 1993 was excluded as it was not possible to evaluate the minimal family intervention separately from the school intervention in which it is included; and Salminen 2005 was excluded as, on closer examination, allocation was not randomised. Including these three, we now list 76 excluded studies, details of which can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Twenty‐three trials were conducted in the USA and one each in Australia, India, the Netherlands, and Norway.

All RCTs tested a family intervention, though the interventions were heterogeneous. The Family Resource Center intervention was tested in two trials (Connell 2007 and Fosco 2013), the Smoke‐Free Kids programme was also tested in two trials (Hiemstra 2014 and Jackson 2006), and the Strengthening Families Program (SFP 10‐14) was tested in three trials (Spoth 2001, Spoth 2002 and a short version by Riesch 2012). Twenty other interventions were each tested by only one RCT. Interventions typically addressed family functioning in order to prevent multiple risky behaviours including tobacco use and substance abuse. A smaller number focused on tobacco alone, and two (Prado 2007; Wu 2003) primarily addressed HIV and unsafe sex but assessed tobacco use outcomes. Nineteen studies had a control group which offered either no intervention, usual care, or a very minimal intervention such as a leaflet, or used a control that targeted different risk behaviours. Eight studies tested a family intervention as an adjunct to a school‐based prevention programme offered to both intervention and control groups.

In addition to heterogeneity of intervention design, focus, and comparator condition there was also variation in the length of follow‐up, ranging from 6 months to 29 years. Key features of the studies are summarised in the following two tables. Table 3 lists studies that compared a family intervention to no intervention, and Table 4 shows studies that tested a family intervention as an adjunct to a school intervention.

1. Summary of studies of family versus no intervention.

| Study | In MA | Intensity | Focus | Age/ grade at baseline | Duration of follow‐up | Control |

| Cullen 1996 | Y | High | Family functioning | New born | 27‐29 years | No intervention/'usual care' |

| Fosco 2013 | Y | High | Family functioning | 6‐8th grade | 3 years | No intervention/'usual care' |

| Haggerty 2007 | Y | High | Family functioning | 8th grade | 2 years | No intervention/'usual care' |

| Prado 2007 | Y | High | HIV & Unsafe sex | Average age 13 | 3 years | Attention control |

| Spoth 2001 | Y | High | Tobacco, alcohol, marijuana | 6th grade | 6 years | Fact sheets/booklets |

| Storr 2002 | Y | High | Child attention problems | 1st grade | 7 years (8th grade) | No intervention^ |

| Pierce 2008 | Y* | High | Family functioning | 12 years | 6 years (age 18) | No intervention |

| Connell 2007 | N | High | Family functioning | 6th grade | 11 years (age 22) | No intervention |

| Dishion 1995 | N | High | Family functioning | Age 10‐14 | 12 months | Teen focus |

| Fang 2013 | N | High | Substance abuse | Age 10‐14 | 2 years | No intervention/'usual care' |

| Olds 1998 | N | High | Family functioning | New born | 15 years | No intervention/'usual care' |

| Riesch 2012 | N | High | Family functioning | Age 9‐11 | 6 months | No intervention/'usual care' |

| Bauman 2001 | Y | Medium | Tobacco & alcohol | Age 12‐14 | 12 months | No intervention/'usual care' |

| Schinke 2004 | N | Medium | Alcohol | Average age 11.5 | 3 years | No intervention/'usual care' |

| Hiemstra 2014 | Y | Low | Tobacco | Age 9‐11 | 3 years | Fact sheets/booklets |

| Jackson 2006 | Y | Low | Tobacco | 3rd grade | 3 years | Fact sheets/booklets |

| Curry 2003 | Y* | Low | Tobacco | Age 10‐12 | 20 months | No intervention/'usual care' |

| Stevens 2002 | N | Low | Tobacco & Alcohol | Average age 11 | 3 years | Prevention of different risky behaviours |

| Wu 2003 | N | Low | HIV & Unsafe sex | Age 12‐16 | 2 years | Teen only focus |

* Includes baseline smokers

^ Also compared to school programme alone

2. Summary of studies of family & school versus school alone.

| Study | In MA | Intensity | Focus | Age/ grade at baseline | Duration of follow‐up | Control |

| Spoth 2002 | Y | High | Family Functioning | 7th grade | 1 year | School only |

| Guilamo‐Ramos 2010 | Y* | High | Tobacco | 6‐8th grade | 15 months | School only |

| Forman 1990 | N | High | Tobacco, alcohol, marijuana | Average age 15 | 1 year | School only |

| Elder 1996 | N | Medium | Tobacco & cardiovascular | 3rd grade | 3 years | School only |

| Jøsendal 1998 | Y | Low | Tobacco | 13 years | 30 months | School only |

| Ary 1990 | N | Low | Tobacco, alcohol, marijuana | 6‐9th grade | 9‐12 months | School only |

| Biglan 1987 | N | Low | Tobacco | 7‐10th grade | 12 months | School only |

| Reddy 2002 | N | Low | Tobacco & cardiovascular | Age 12 | 1‐8 months | School only |

* Includes baseline smokers

Clustering was controlled for in the following C‐RCTs: Ary 1990; Biglan 1987; Forman 1990; Fosco 2013; Hiemstra 2014; Jackson 2006; Jøsendal 1998; Reddy 2002; Riesch 2012; Spoth 2001; and Spoth 2002. Only three trials provided intraclass correlations (ICCs) (Guilamo‐Ramos 2010 < 0.01, Hiemstra 2014, ICC = "zero" and Wu 2003, ICC = 0.0000). Only one RCT (Dishion 1995) did not control for clustering, and as the ICCs for the three trials which provided them were zero, we did not apply any correction to Dishion 1995. All other trials involved individual interventions with parents or youth and correction for clustering was not required. Ten studies reported good adherence to training (where relevant) and adherence to intervention, 13 reported intermediate levels and four had no evidence about adherence, or evidence of minimal adherence (fidelity and adherence summarised in Table 5). We were unable to extract data from thirteen study reports in a format that could be included in meta‐analysis.

3. Classification of fidelity of training & intervention adherence.

| Study | Fidelity of training/ adherence | Description |

| Bauman 2001 | Good | Provided the consultants to the parents with manualised training throughout the two year programme. "Families who completed the entire program (74%) spent an average total 4 1/2 hours doing the program and parents spent an additional hour talking with the health educator by telephone. The majority of families completed all activities associated with each booklet." |

| Elder 1996 | Good | Provided classroom teachers with 1 or 1.5 training sessions. He found that of the children who began in a school which offered the school + family intervention, 47% attended such a school for the entire period. For the FACTS tobacco curriculum 87% of teachers participated in the classroom sessions, checklists were returned for 96% of classroom sessions, 96% completed the entire lesson and 87% were implemented without modification. For the Family Intervention for tobacco 97% of session‐specific activities were completed, and 78% of adults participated in the home activities. However, only 48% of home team activity cards were returned, 40% of schools participated in 'Great American Smokeout' activities, 33% of schools held assemblies about tobacco and 25% sponsored anti‐tobacco or anti‐drug clubs. |

| Fang 2013 | Good | The intervention was delivered by Internet and fidelity was assured because the computer automatically returned participants to the last place at which they logged off and participants could not log on to the next module until the previous one was completed; only data from participants who answered 3 of 4 fidelity check questions were included. |

| Forman 1990 | Good | All sessions were tape recorded and independent raters achieved intercoder agreement > 90%. In the coping skills training group half of the sessions covered > 80% of the planned activities, the average completion rate across all coping sessions was 74%, 2/3 of the students completed 9 or 10 of the intervention sessions and 92% completed at least 7. In the School‐Plus‐Parent intervention 44% of the students had at least one parent participate in the parent training sessions and of the parents who attended 74% attended at least 4 meetings. |

| Haggerty 2007 | Good | The intervention was self‐administered with telephone support. The mean level of reported completion of the family activities was 81%. On average, family consultants made 16.9 call attempts (resulting in 9.7 completed calls during the 10 weeks) and phone calls lasted about 10.5 minutes/week. in the parent and adolescent format group leaders called families each week to remind them of the upcoming session and 77.9% of families initiated the parent and teen sessions. The mean number of sessions attended was 4.56. Family sessions were led by two workshop leaders with prior experience conducting parent or teen workshops who received 20 hours of training. |

| Hiemstra 2014 | Good | 81% of intervention group children read and completed ⋝ 3 modules and 73% of control families read and completed 3 fact sheets. |

| Riesch 2012 | Good | Students received three 2‐day training sessions. On their checklists more than 90% of the content was consistently covered in the adult groups and 87% in the youth groups. |

| Schinke 2004 | Good | CD‐ROM usage was recorded by code: 95% of youths completed the CD‐ROM in the CD‐ROM intervention group, and 91% in the CD‐ROM + parent intervention group, 83% of parents watched the videotape, 67 % attended the workshop and 79% completed the parent CD‐ROM |

| Spoth 2001 | Good | ISFP intervention: each team of leaders was observed 2‐3 times and there were reliability checks on 50% of family, 30% of youth and 25% of parent sessions (paired observers' scores differed by an average of 10%): coverage of topics was 89% in youth, 87% in family, and 83% in parent sessions. PDFY intervention: each team of group leaders was observed for 2/5 sessions and 50% of these sessions were observed by two observers (average ratings difference 6%) and there was an average 69% coverage of topics. |

| Spoth 2002 | Good | SFP 10‐14 intervention: each team of facilitators was observed on 2‐3 occasions (observers' ratings differed by an average of 2.4%) and average adherence to programme components was 92%. LST intervention: each classroom teacher was observed on 2‐3 occasions (observers' ratings differed by an average 13.6%) and average programme component adherence was 85%. |

| Ary 1990 | Intermediate | Provided teachers with 2‐3 hours of classroom instruction. Surveys of teachers indicated that the control group received 10 sessions of standard tobacco and drug education (with 97% recognizing peer pressures, 97% short‐term effects on the body and brain, 96% long‐term health consequences, 84% decision‐making skills, 72% media pressures, and 67% refusal skills practice), and the intervention schools received a median of 5 sessions of other drug education in addition to PATH. There was no assessment whether the letters to parents were received or read. |

| Connell 2007 | Intermediate | Of the 500 participants, only 115 chose to participate in the Family Check Up. These families received an average 8.9 hours of direct contact with intervention staff. |

| Cullen 1996 | Intermediate | Same general practitioner provided the counselling throughout the intervention, standard questions were used to introduce new ideas but there is no statement that a manualised protocol was followed. |

| Curry 2003 | Intermediate | After 6 months 83% of the parents in the intervention group said they had read the handbook, completed one or more activities and spoken with a counsellor; 51% reported they had watched the videotape and 42% the CDC tape and 47% of the intervention and 45% of the control group children had visited a physician in the previous 6 months. However, of these only 22% in the intervention and 15% in the control group said tobacco use was discussed with the child; and 17% in the intervention and 3% in the control group said the 'Steering Clear' project was discussed. |

| Dishion 1995 | Intermediate | All participants were visited by a therapist at home but there was no process analysis. |

| Fosco 2013 | Intermediate | Of 386 families in the intervention group, 51% received a consultation from a parent consultant and 42% in the full FCU intervention. Of those receiving FCU 78% received additional follow‐up assistance such as parent skills training, education‐related concerns, support in success with homework, attendance and grades, improving school behaviour, and facilitating parent‐teacher communication. Of 180 families, 36% received positive behaviour support, 68% support in limit setting and monitoring skills, 73% support for communication and problem‐solving, 67% school‐related support. Intervention families received an average 94.2 minutes of intervention time |

| Jackson 2006 | Intermediate | Interviews with children were by staff with 2 years experience and 30 hours of training and parent interviews were computer‐assisted by a contracted survey unit. There was no process analysis whether parents received, read and discussed tip sheets, or if the control group received and read the fact sheets. |

| Jøsendal 1998 | Intermediate | A process analysis was conducted but the results were not stated, and there was no process analysis of the intervention variations as time progressed: There were "verbal assurances of compliance from Grade 8 pupils and teachers and Grade 9 pupils." |

| Pierce 2008 | Intermediate | parent counsellors completed 60 hours of training including role playing and tapes were reviewed for fidelity (no statement of fidelity outcomes). |

| Prado 2007 | Intermediate | Facilitators had an average 5 years experience working with low‐income Hispanic immigrant families, were certified in Familias Unidas and PATH, were trained in general group process facilitation and conducted 54 pilot sessions. All sessions were taped. Adherence to Familias Unidas was 3.72/6 and to PATH 3.70/6 (interrater reliability k = .75). |

| Reddy 2002 | Intermediate | There was no process analysis; 2/30 schools had shorter follow‐up; 14/20 schools displayed all 10 posters, 6 displayed 7‐9; 6/20 schools implemented all 20 activities from the teachers' manual, and 8/10 schools in the Family intervention group distributed at least 5 of the 6 booklets. |

| Stevens 2002 | Intermediate | All paediatricians and nurse practitioners received 3 hours of training. After the initial intervention visits 95% of children were seen for subsequent visits, during which prevention messages were documented as delivered in only 47% of the safety intervention and 51% of the alcohol/tobacco intervention practices |

| Storr 2002 | Intermediate | First grade CC and FSP teachers received 60 hours training and certification. In the CC Intervention the implementation mean score was 59.9% and median score 64.4% (range 30‐78%). In the FSP intervention parents attended an average 4/7 and median 5/7 of the core parenting sessions (and 13% attended none). |

| Biglan 1987 | No/minimal evidence | Provided classroom teachers with 2‐3 hours of training. No statement if the parent messages were received or read. |

| Guilamo‐Ramos 2010 | No/minimal evidence | No statement about training or fidelity of implementation. |

| Olds 1998 | No/minimal evidence | Wide ranges in the number of visits (families visited at home received an average of 9 [range 0 ‐16] visits during pregnancy and 23 [range 0 ‐ 59] from birth through the child's 2nd birthday). There was no process analysis of the content of the visits. |

| Wu 2003 | No/minimal evidence | No process analysis. |

We grouped the studies according to the intensity of the family component into three levels of intensity. In the descriptions below, the studies contributed to the comparison between a family intervention and a non intervention or usual care control, unless noted otherwise.

(a) High Intensity

Connell 2007 compared: (1) the provision of a Family Resource Center in schools with (a) brief consultations with parents; (b) telephone consultations; (c) feedback to parents on their children's behaviour at school; (d) access to videotapes and books; (e) the SHAPe Curriculum for students with 6 lessons (school success, health decisions, building positive peer groups, cycle of respect, coping with stress and anger, and solving problems peacefully), and (2) the Family Resource Center + Family Check Up (interviews exploring parent concerns, assessment including videotaping the family at home, feedback by the therapist using motivational interviewing strategies and exploring interventional services the family could use, which were delivered over two years by therapists). This study could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

Cullen 1996 tested the effect of 20‐30 minute interviews (four annually in the 1st year and two annually for the next four years) by a general practitioner with new mothers to enhance self‐worth, self‐acceptance, foster gentle physical interaction with her child, and adopt a positive attitude to modifying her child's behaviour. Children were followed up as adolescents or young adults.

Dishion 1995 tested "alternative strategies to reduce escalation in problem behaviours among high‐risk young adolescents." Strategeis were to "target parents' use of effective and non‐coercive family management practices (parent focus) and young adolescent's self‐regulation and competence in family and peer environments (teen focus)." Parent sessions focused on four key skills: monitoring; positive reinforcement; limit setting and problem solving. Twelve 90‐minute counselling sessions based on scripted materials and videotapes were tested in four formats: (1) Parent focus: the parent's family management practices and communication skills (monitoring, positive reinforcement, limit setting, and problem solving, with discussion of home practices and demonstration of the skills, with exercises, role‐plays, and discussions); (2) Teen focus: teen self‐regulation and pro‐social behaviour in parental and peer environments (self‐monitoring and tracking, pro‐social goal setting, developing peer environments supportive of pro‐social behaviour; setting limits with friends and problem solving and communication skills with parents and peers); (3) combined parent and teen intervention and (4) self directed change (the six newsletters and five brief videos that accompanied the parent‐ and teen‐interventions). Interventions 1‐3 were classified as high intensity. Results could not be included in a meta‐analysis

Forman 1990 compared (1) a school intervention (10 session small groups with Botvin's Life Skills Training), and (2) the school intervention + a parent intervention (parents participated in five weekly two‐hour sessions to teach parents the coping skills their children were learning in the student groups, teach parents behaviour management skills, and develop a small group support system for parents to encourage each other to take positive, constructive action regarding their adolescents). This study of a family intervention as adjunct to a school intervention could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

Fosco 2013 compared (1) use of Family Resource Center in schools to (2) control (no intervention). A parent consultant was trained in the Family Check‐Up model to facilitate collaboration with parents, identify youth at risk, and refer at‐risk students for counselling. At risk adolescents and families participated in three motivational interviewing sessions to identify family strengths and weaknesses, motivate parents to improve parenting, and to engage in intervention services. Feedback about assessment results provided opportunity to select interventions tailored to unique needs of each family.

Guilamo‐Ramos 2010 compared (1) the Project Towards No Tobacco Use (TNT) risk reduction smoking intervention (10 modules modified for inner city schools and two face‐to‐face sessions of 2.5 hours each addressing: effective listening and tobacco information; course and consequences of tobacco use; self esteem; being true to oneself; changing negative thoughts; effective communication; assertiveness and refusal skills; advertising and social activism), and (2) the "Linking Lives" intervention (consisting of: "Raising Smoke‐Free Kids" (manual of nine short modules, two tobacco‐related homework assignments for parents to use with adolescent); two one‐day sessions (Day 1 discussed module topics, concept parents could make a difference in their adolescent's tobacco‐related behaviour, strategies for effective communication, topics parents might consider discussing in their conversations with their adolescents and the importance of setting limits; Day 2 consisted of two tobacco‐related homework assignments on consequences of smoking and ways to resist peer pressure)). Mothers received two booster calls one and six months after the intervention. This study contributes to the analysis of family interventions used as adjuncts to school interventions.

Haggerty 2007 compared two formats (self‐administered with telephone facilitator support, and a parent and adolescent format) for a seven session "Parents Who Care" programme and control (no treatment). The seven chapters of the workbook were: Relating to your teen; Risks: Identifying and reducing them; Protection: Bonding with your teen to strengthen resilience; Tools: Working with your family to solve problems; Involvement: Allowing everyone to contribute; Policies: Setting family policies on health and safety issues and Supervision: Supervising without invading. In each session parents and adolescents watched a video, practised skills separately and then as families and were asked to continue practice at home.

Olds 1998 provided for infants (1) free sensory and developmental screening performed at 12 and 24 months, with referrals for further evaluation and treatment where necessary, and (2) the same assessments and nurse home visits (nurses taught positive health‐related behaviours, competent care of the child, and personal development for the mother including family planning, educational achievement, and return to the workforce). Children's smoking was assessed at age 15 years. This study could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

Pierce 2008 tested the Parenting to Prevent Problem Behaviors Project, including a self‐help manual (with 12 chapters including building positive behaviours, setting effective limits and relationship building) and a lay facilitator to help participants to work through the manual who followed a computer‐assisted structured counselling script using motivational interviewing and searched the internet and study library for answers to parents' problems. Previously researched information sheets were sent to parents electronically or by mail, and there was a computer‐assisted structured counselling protocol for parents who needed additional help to implement best practices.

Prado 2007 assessed whether providing an intervention to focus on and strengthen Hispanic family‐centred values was required for a substance, sexual behaviour and HIV risk intervention to be effective. He compared: (1) an intervention to improve family functioning to reduce substance use and unsafe sexual behaviour (the Familias Unidas intervention to increase parental involvement, positive parenting and family support in Hispanic families (high intensity) combined with PATH [Parent pre‐adolescent training for HIV prevention]); (2) PATH and an intervention unrelated to parenting (English language lessons); and (3) PATH and a different intervention unrelated to parenting (American Heart Assocation programme).

Riesch 2012 tested a short version of the Strengthening Families Program (SFP 10‐14 ), during which a youth and parent attended the seven‐week, two‐hour‐per‐week programme with videotapes and discussions. This study could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

Spoth 2001 compared two family interventions: (1) the full length SFP 10‐14, now renamed ISF (six two‐hour session and one one‐hour sessions); (2) the Preparing for the Drug‐Free Years Program (five two‐hour sessions) and (3) a control group which received mailed information. The two family interventions are shown separately in the analysis, dividing the control group to avoid double counting

Spoth 2002 tested the SFP programme of seven one‐hour weekly sessions for parents and children to strengthen parental skills in nurturing, setting limits and communication about substances and strengthen children's prosocial and peer resistance skills, and four booster sessions offered one year later. All study participants received the Life Skills Training (LST) intervention at school, so this contributes to the analysis of family interventions used as adjuncts to school intervention.

Storr 2002 compared: (1) the Classroom‐Centered (CC) Intervention (language and mathematics curricula enhanced to encourage skills in critical thinking, composition, listening and comprehension, whole‐class strategies to encourage problem solving by children in group contexts, decrease aggressive behaviour, and encourage time on task, strategies for children not performing adequately; plus teams of children received points for good behaviour and lost points for behaviours such as starting fights ‐ the points could be exchanged for classroom activities, game periods and stickers), and (2) the Family‐School Partnership (FSP) intervention (consisting of multiple components: (a) the 'Parents on Your Side Program' trained teachers to communicate with parents and build partnerships, with a three‐day workshop, training manual and follow‐up supervisory visits; (b) weekly home‐school learning and communicating activities and (c) nine workshops for parents (first two workshops to establish an effective and enduring parent‐staff relationship and facilitate children's learning and behaviour; next five workshops focused on effective disciplinary strategies). This was classified as high intensity for the amount of contact, but there was no description of the amount of tobacco‐focused content. The FSP intervention was also compared to a usual curriculum condition, which is used as the comparator in the family versus no intervention analysis.

(b) Medium intensity

Bauman 2001 tested the Family Matters intervention: four booklets were mailed to participants, and two weeks after each booklet was posted a health educator telephoned a parent, encouraged the participation of all family members in the programme and answered questions.

Elder 1996 compared: (1) a school intervention (15 sessions in third grade about diets healthy for hearts and exercise, 12 in fourth grade about exercise, and 16 about exercise in fifth grade plus eight about tobacco; the tobacco intervention consisted of 'F.A.C.T.S. for 5' (Facts and Activities about Chewing Tobacco and Smoking) with four 50 minutes sessions on: short‐ and long‐term effects of tobacco use; motivations and fallacies about tobacco use; economic costs of tobacco use and the efforts of the tobacco companies to promote use; dangers of passive smoking and being supportive of those who want to quit), as well as a policy component, encouraging the adoption of policies for the school to be tobacco‐free and (2) the school intervention plus a family intervention consisting of a home‐based programme, using 'The Unpuffables' (four sessions with stories about adolescents who combat tobacco use, and games to play with parents) (moderate intensity). This study of a family intervention as adjunct to a school intervention could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

Fang 2013 tested an online nine session (each 35‐45 minutes) substance abuse prevention programme to strengthen the quality of girls' relationships with mothers and increase girls' resilience to resist substance use (consisting of audio, graphics, animation, activities, skill demonstrations, guided rehearsal and immediate feedback).

Schinke 2004 compared a social learning and problem solving curriculum on CD‐ROM (consisting of goal setting, coping, peer pressure, refusal skills, norm correcting, self‐efficacy, problem‐solving (Stop, Options, Decide, Act, Self‐praise), decision‐making, effective communication and time management), and (2) the CD‐ROM + parent intervention (videotape, printed materials on the goals of the youth intervention, showed how parents could help avoid problems with alcohol, and the importance of family rituals, rules and bonding, a two‐hour parent workshop, and a parent CD‐ROM how to reduce youth alcohol use). This study could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

(c) Low intensity (usually written materials or brief contact)

Ary 1990 compared (1) the tobacco social skills Project PATH (Programs to Advance Teen Health), and (2) PATH + parent messages (three mailed brochures to support the classroom messages about refusal skills). This study of a family intervention as adjunct to a school intervention could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

Biglan 1987 compared (1) a programme of information about the health effects and short‐term effects of tobacco, including sensitization to pressures to smoke, training in refusal skills including modelling, rehearsal, reinforcement, practice, video practice, and supporting peers in refusals, and (2) the programme plus four messages mailed to parents following the programme to encourage parents to discuss their views of smoking with their child and set clear rules about smoking. This study of a family intervention as adjunct to a school intervention could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

Curry 2003 tested the 'Steering Clear Project, which included: (a) a 12‐chapter parent handbook, a videotape on the experiences of a former tobacco model, a Centers for Disease Control videotape and a comic book, pen and stickers for the child; (b) two calls from a counsellor; (c) a six‐page newsletter 14 months later; (d) access to a website and (e) prompts to physicians during appointments to encourage families to use the videos and website and talk about staying smoke‐free.

Hiemstra 2014 and Jackson 2006 compared (1) the home‐based Smoke‐Free Kids programme (six printed activity modules containing general communication about smoking, influence of smoking messages, rule setting and non‐smoking agreement, creating a smoke‐free house and environment, and peer influences), and (2) five fact sheets on youth smoking available in the media.

Jøsendal 1998 tested three formats (classroom programme with (1) involvement of parents and teachers, (2) involvement of parents only, or (3) involvement of teachers only) for an eight‐session intervention focused on personal freedom, the freedom to choose, freedom from addiction, making one's own decisions, tobacco‐resistance skills, and the short‐term consequences of smoking. Students brought two brochures home, teachers involved parents in discussions on 'appropriate occasions', and students and parents signed non‐smoking contracts. This study contributes to the analysis of family interventions used as adjuncts to a school intervention.

Reddy 2002 compared (1) the school‐based Project HRIDAY (Health‐Related Information and Dissemination Among Youth), consisting of posters, a booklet on heart health, classroom activities addressing influences to smoke, ways to refuse offers to smoke, and passive smoke, and round table discussions, and (2) HRIDAY plus a family intervention (consisting of six booklets, one of which was about tobacco, brought back to school with parents' signed opinions about the booklets). This study of a family intervention as adjunct to a school intervention could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

Stevens 2002 compared the effect of paediatrician/nurse practitioner advice about (1) alcohol and tobacco and (2) advice about gun safety, bicycle helmets and car seatbelts. Interventions encouraged family communication and rule setting, there was a brochure on effective communication, and children and parents each received 12 quarterly newsletters to reinforce the messages.

Wu 2003 compared (1) Focus on Kids (FOK), an eight session HIV small‐group risk reduction programme focusing on decision making, goal setting, communication, negotiating, and consensual relationships and information regarding safe sex, drugs, alcohol and drug selling, conducted in small groups (5‐10), led by two older peers with no parental involvement, (2) FOK + ImPACT (Informed Parents and Children Together) which included a 20‐minute video about parental monitoring and communicating, role‐playing vignettes in the child's home between the parent and youth with instructor critique and a condom demonstration from the instruction, and (3) FOK + ImPACT + booster sessions at 6 and 10 months. FOK has a minor informational component about tobacco and no family component. ImPACT is 20 minute video followed by role plays between parent and youth but has no tobacco focus. Baseline and 24 months smoking status were measured for all three programmes. We assessed ImPACT as low intensity, without tobacco intervention but with tobacco data collection.

Risk of bias in included studies

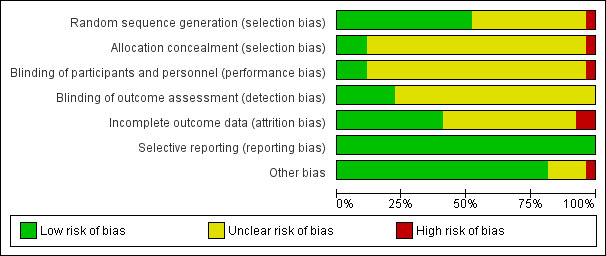

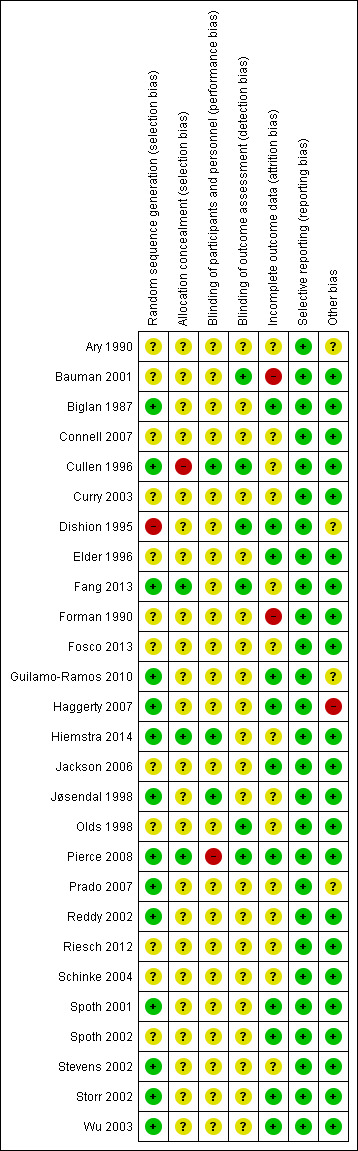

Fifty‐two per cent of trials were assessed to be at low risk of selection bias due to the method of randomisation, 44% at unknown risk (because only the words "randomised" were used with no method stated) and 4% at high risk. Eleven per cent of trials were at low risk for allocation concealment, 85% at unknown risk (no statement if performed) and 4% at high risk. Eleven per cent were at low risk for blinding of participants and personnel, 85% at unknown risk (no statement if performed) and 4% at high risk. (Note: It would have not been possible to blind participants to which programme they were in). Twenty‐two per cent of studies were at low risk for blinding of outcome assessment and 78% at unknown risk (no statement if performed). Forty‐one per cent were at low risk for incomplete outcome data, 52% at unknown risk (insufficient information provided to assess if at risk), and 7% at high risk. All were judged to be at low risk for selective reporting (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

The outcome for all analyses was smoking behaviour at longest follow‐up. Smoking behaviour could include even a puff, or more regular use.

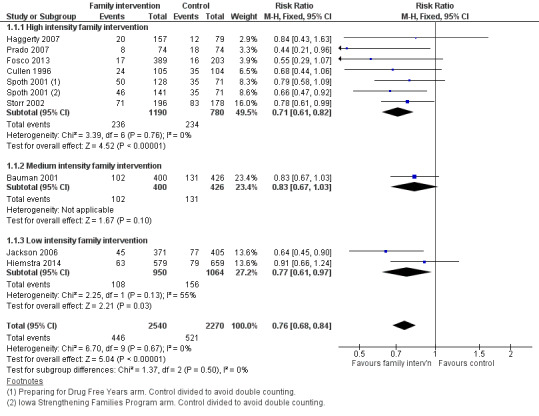

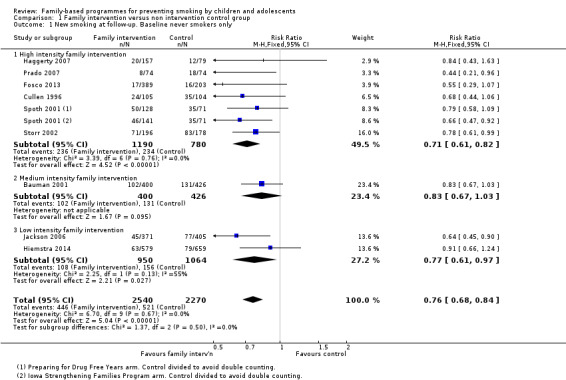

Analysis 1. Family intervention compared to no intervention

Nine studies (4810 participants at follow‐up) reported the impact of a family intervention on smoking uptake for baseline never smokers in a format suitable for meta‐analysis. The pooled estimate detected a reduction in smoking behaviour in the intervention arm (risk ratio [RR] 0.76, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.68 to 0.84) Figure 3 (Analysis 1.1). When the trials were analysed by intensity of family intervention there was a significant effect in the subgroup of six which used a high intensity intervention (Cullen 1996;Fosco 2013; Haggerty 2007; Prado 2007; Spoth 2001 (two arms: PDFY and ISFP); Storr 2002) (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.82). Only one study was categorised as using a medium intensity intervention (Bauman 2001). Two used a low intensity intervention (Hiemstra 2014; Jackson 2006) with a RR of 0.77, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.97. Three of the studies individually reported significant effects; Spoth 2001 (using the Iowa Strengthening Families intervention) and Storr 2002 which were high intensity, and Jackson 2006, which was low intensity.

3.

Family intervention versus non intervention control group: New smoking at follow‐up. Baseline never smokers only.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Family intervention versus non intervention control group, Outcome 1 New smoking at follow‐up. Baseline never smokers only.

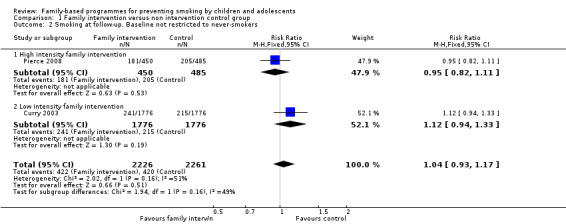

Two studies provided data for meta‐analysis but included some participants who already had experience of smoking at baseline. One used a high intensity family intervention (Pierce 2008) and one a low intensity intervention (Curry 2003). When pooled, these studies (4487 participants) did not detect evidence of any intervention effect (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.17, Analysis 1.2)

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Family intervention versus non intervention control group, Outcome 2 Smoking at follow‐up. Baseline not restricted to never‐smokers.

Eight studies (approximately 5000 participants) compared a family intervention to control, but did not report outcomes in a format suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis. Effects are summarised in Analysis 1.3. Four used a high intensity intervention (Connell 2007; Dishion 1995; Olds 1998; Riesch 2012), two a medium intensity (Fang 2013; Schinke 2004) and two a low intensity intervention (Stevens 2002; Wu 2003). Only one of these studies reported a significant positive effect (Wu 2003); most of the remainder reported non significant effects favouring the intervention.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Family intervention versus non intervention control group, Outcome 3 Smoking at follow‐up. Results not in meta‐analysable format.

| Smoking at follow‐up. Results not in meta‐analysable format | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of participants | Results |

| High intensity family intervention | ||

| Connell 2007 | 998 6th graders allocated. 115/500 intervention received additional Family Check Up component | No overall effect; 'The correlations reveal that, in general, random assignment to the intervention condition was not significantly correlated with problem behaviors over time.' However 'engagement with a family‐centered intervention reduced the risk for problem behaviors from early to late adolescence, including antisocial behavior and tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use.' using CACE modelling to match engagers with similar controls. Treatment predicted significantly less growth in tobacco use, although the intervention effect diminished over time. The effect size for the difference in estimated tobacco use at age 22 for the engagers in the intervention vs. control condition was large (reported in Connell 2009) |

| Dishion 1995 | Pre‐test: 119 families randomly assigned to 4 family therapy treatment groups to "reduce escalation in problem behaviors among high‐risk adolescents" and a control condition, followed for one year | Results reported as Frequency (Log + 1). The F ratios report an N of 140, which includes all intervention groups and the non‐random control and thus the probabilities reported in the text are not reported here. Parent‐only baseline 0.91, 1 year follow‐up 0.63 Teen only Baseline 0.81, 1 year follow‐up 1.66 Parent and teen baseline 0.95, 1 year follow‐up 2.09 Self‐directed baseline 0.75, 1 year follow‐up 1.16. |

| Olds 1998 | 400 pregnant women randomised to different types of antenatal & postnatal support until child's 2nd birthday. Follow‐up at 15 years | No differences reported in amount of cigarette use in past 6 months between any groups |

| Riesch 2012 | 167 parent‐youth dyads recruited from elementary schools in Madison, Wisconsin and Indianapolis, Indiana, and randomised to the Strengthening Families Program 10‐14 (SFP 10‐14) or data collection only | No baseline smoking data. Abstract states: "Youth participation in alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs was very low and did not differ post program." There was attrition in the intervention group from 87 to 63 and in the control from 81 to 66 and post program data for "smoked a cigarette, even a puff" are incomplete. |

| Medium intensity family intervention | ||

| Fang 2013 | Pre‐test: 108; at 2‐years 93 | No evidence of effect: 'The intervention, however, did not exert significant effect on girls’ cigarette use over time.' 30‐day cigarette use, mean (SD): Intervention 0.02 (0.14), Control 1.95 (9.87), p = 0.171 |

| Schinke 2004 | 514 10‐12 year olds | No evidence of additional effect of parent component over CD based intervention. Past 30 day cigarette use CD + parent group; pretest 0.6, 3y 0.8. CD; pretest 0.6, 3y 0.9. Control; pretest 0.7, 3y 1.3; (p < .05 for both intervention groups compared to control) |

| Low intensity family intervention | ||

| Stevens 2002 | 12 paediatric practices in New England approached 4,096 families and recruited 85% (n= 3525) of their 5th and 6th grade children and their parents; 3094 completed the baseline assessment and 2173 (70%) child‐parent pairs completed the 36 month follow‐up. | At baseline 5.4% of children in the alcohol and tobacco intervention and 4.6% in the gun safety, bicycle helmet and set belt use safety intervention group had ever smoked (n.s.). No control group. At 36 months follow‐up there were no significant differences in having ever smoked, OR = 0.97 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.20), P = 0.78. |

| Wu 2003 | 800 African‐American youth 13‐16 years. (1) Focus on Kids (FOK): 8 session (each 1.5 hours) HIV small‐group risk reduction programme on decision making, goal setting, communicating, negotiating, and consensual relationships and information regarding safe sex, drugs, alcohol and drug selling. Conducted in small groups (5‐10), no parent participation. (2) (a) FOK + (b) ImPACT (Informed Parents and Children Together): 20‐min video emphasising concepts of parental monitoring and communicating with 2 instructor‐led role‐playing vignettes between the parent and youth in the child's home. The interventionist critiques the role play according to the main talking points of the videotape and conducts a condom demonstration. (3) (a) FOK + (b) 4 FOK booster sessions at 6m and 10m + (c) + ImPACT Focus on Kids has a minor informational component about tobacco and no family component. ImPACT is 20 minute video followed by role plays between parent and youth, then criticised by interventionist. It has no tobacco focus, but baseline and 24 months smoking were measured for all 3 programmes. ImPACT assessed as low intensity. |

At 24 months the past 6 month smoking rate was significantly lower (P = .003) in the ImPACT family intervention group (+/‐FOK boosters), 12.5%, than the FOK control, 22.7% in the risk reduction intervention (Focus on Kids) is 22.7% and in the combined ImPACT (Informed parents and Children Together) groups is 12.5% Table 1 shows baseline smoking rates for those who remained in the study at 24 months were 27% in the FOK and 23% in the ImPACT group, implying smoking rates decreased for both intervention groups at 24 months (data from Stanton 2004). . |

Analysis 2. Combined family plus school intervention compared to school intervention

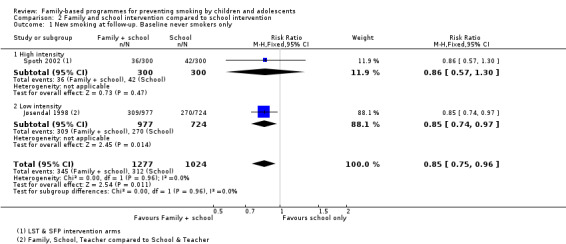

Two studies (Jøsendal 1998 and Spoth 2002, 2301 participants at follow‐up) evaluated the effect of a family intervention added to a school‐based intervention and reported suitable data for meta‐analysis. There was evidence of a benefit of the additional intervention over the school component alone (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.96, Analysis 2.1), with Jøsendal 1998 detecting a significant benefit.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Family and school intervention compared to school intervention, Outcome 1 New smoking at follow‐up. Baseline never smokers only.

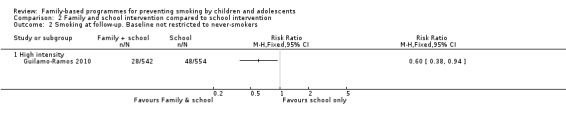

One high intensity intervention study (Guilamo‐Ramos 2010, 1096 participants) provided data for meta‐analysis but included some participants who already had experience of smoking at baseline. There was evidence of a benefit of the additional intervention over the school component alone (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.94, Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Family and school intervention compared to school intervention, Outcome 2 Smoking at follow‐up. Baseline not restricted to never‐smokers.

Five studies (approximately 18,500 participants) evaluated the effect of a family intervention added to a school‐based intervention, but did not report outcomes in a format suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis. Effects are summarised in Analysis 2.3. One used a high intensity intervention (Forman 1990), one a medium intensity intervention (Elder 1996) and three a low intensity intervention (Ary 1990; Biglan 1987; Reddy 2002). None of these studies reported significant effects.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Family and school intervention compared to school intervention, Outcome 3 Smoking at follow‐up. Results not in meta‐analysable format.

| Smoking at follow‐up. Results not in meta‐analysable format | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of participants | Results |

| High intensity interventions | ||

| Forman 1990 | Baseline: 279 students in 30 schools completed 20 hour training programme and pre and post‐treatment assessment sessions; 201 completed booster and 1 year assessment | At 1 year, no significant differences in mean* cigarette use: School Intervention pretest mean = 2.90, 1 year follow‐up = 3.02 School + parent intervention pretest mean = 2.81, 1 year follow‐up = 2.95 School + parent intervention (parent attended no sessions) pretest mean = 2.84, year follow‐up = 2.81 Control pretest mean 2.83, 1 year follow‐up = 2.93 *Frequency of cigarette use averaged over groups: never = 1, used to but quit = 2, a few a month = 3, a few a week = 4, every day = 5. |

| Medium intensity interventions | ||

| Elder 1996 | Eligibles; all 3rd grade children 1991‐1 (n not stated) . Average of 9087 children evaluated 1992‐1994, and 7,827 at 36 months (at end of 5th grade) of whom 6,527 gave complete information. | At 3 years no significant differences in the percentages in the experimental (4.7%) and control groups (5%) stating that they had ever smoked (OR = 1.01, 95% CI 0.79‐1.30). No evidence provided of any effects from adding the family "Unpuffables" intervention to the school intervention |

| Low intensity interventions | ||

| Ary 1990 | Pre‐test: 7,837 1 year: 6,263 completed assessments at baseline and one year | After 1 year there were no effects of the messages to parents. "The children of parents who received the parent messages as part of the experimental evaluation of this component did not differ significantly in their levels of smoking or smokeless tobacco use from those whose parents did not receive parent messages." |

| Biglan 1987 | Pre‐test:3,387; at one year 2,391 | At 1 year there were no effects of the messages to parents . "The provision of parent messages did not affect outcome". |

| Reddy 2002 | Randomised to Project HRIDAY (Health‐Related Informantion and Dissemination Among Youth) (n = 1439) or to School/Family Intervention (n = 1863) or control. Family intervention consisted of six booklets taken home to parents, only one of which discussed tobacco | At posttest there was no significant difference between the school+family and the school alone condition, although both intervention conditions were significantly different to control (p < .01). ‘The family based program did not appear to significantly add to outcomes’. Mean score at posttest for question ‘Have you ever tried a cigarette/bidi’, 1=Yes. School + Family .0366 (95% CI .0264 to .0504); School .0571 (.0422 to .0768); Control .0937 (.0728 to .1198). Increase in score from pre‐ to posttest was smaller for School + Family than other conditions but CIs wide and no statistical test reported. |

Analysis 3. Other comparisons

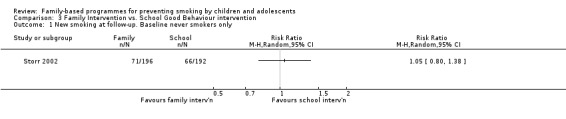

One trial (Storr 2002) contributing to Analysis 1 also had a school‐based comparison arm. The family‐school partnership arm and the classroom centred 'Good Behavior Game' arms had similar effects on behaviour (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.38, n = 388, Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Family Intervention vs. School Good Behaviour intervention, Outcome 1 New smoking at follow‐up. Baseline never smokers only.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We divided studies into two groups. The first group evaluated family‐based interventions used on their own, compared to a no‐intervention control. The second group evaluated family‐based interventions used as adjuncts to school‐based prevention interventions; these were compared to school‐based interventions alone. Pooling nine trials with baseline never‐smokers (six trials used a high, one a medium and two a low intensity intervention) found fewer participants in the intervention arms began smoking than those in no‐intervention control groups. Pooling two trials with baseline never‐smokers comparing a family intervention plus a school intervention to a school intervention alone (one high and one low intensity) found fewer participants in the combined arms began smoking than those only receiving the school‐based programmes. No study reported any possible harms from the interventions.

Thus, there was moderate quality evidence of benefit for family interventions used on their own, and when used as adjuncts to school interventions. For stand alone interventions, a family intervention might reduce new smoking behaviour, including experimenting or trying 'just a puff', by between 16 and 32%. Based on an average prevalence of new smoking across study control groups of 230 per 1000 this would translate to a reduction to between 156 and 193 per 1000 with the intervention (Table 1). However, the prevalence of new smoking that occurred by the time of follow‐up differed across studies and the absolute effect of an intervention would depend on the setting. For interventions used as adjuncts to school programmes the estimated benefit would be a reduction in new smoking behaviour of between 4 and 25%. Based on the same assumed control group rate of 230 per 1000 this would translate to a reduction in new behaviour to between 172 and 221 per 1000 from the addition of a family component to a school intervention (Table 2).

The common feature of the effective high intensity interventions was encouraging authoritative parenting (interest in and care for the adolescent, often with rule setting). Cullen 1996 used 12 visits by a general practitioner with new mothers to enhance self‐worth, self‐acceptance, foster gentle physical interaction with her child, and adopt a positive attitude to modifying her child's behaviour. Fosco 2013 provided a Family Resource Center in schools and a consultant used motivational interviewing to identify family strengths and weaknesses, motivate parents to improve parenting and engage in intervention services tailored to the unique needs of each family. Haggerty 2007 provided telephone facilitator support as parents and teens worked through a workbook to identify risks and reduce them, bond with the teen, solve family problems, set family policies and supervise without invading. Prado 2007 provided an intervention to strengthen Hispanic family‐centred values and increase parental involvement, positive parenting and family support. Spoth 2001 provided sessions for parents and children to strengthen parental skills in nurturing, setting limits and communication about substances, and strengthen children's prosocial and peer resistance skills. Storr 2002 provided workshops to facilitate children's learning and behaviour and focus on effective disciplinary strategies. In a medium intensity intervention Bauman 2001 sent Family Matters booklets to parents and a health educator telephoned a parent, encouraged the participation of all family members in the programme and answered questions.

The common feature of the effective high intensity interventions used as adjuncts to school interventions was again encouraging authoritative parenting. Guilamo‐Ramos 2010 encouraged parents to think they could make a difference in their adolescent's tobacco‐related behaviour, including strategies for effective communication, topics parents might consider discussing in their conversations with their adolescents, the importance of setting limits, and ways to resist peer pressure. Spoth 2002 encouraged parents to strengthen their skills in nurturing, setting limits and communicating about substances, and strengthen their children's prosocial and peer resistance skills. The classroom intervention in Jøsendal 1998 focused on personal freedom, the freedom to choose, freedom from addiction, and making one's own decisions and the low intensity family component focused on teachers involving parents in discussions and students signing non‐smoking contracts.