Abstract

Background

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are widely prescribed for primary hypertension (systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg). However, while ACE inhibitors have been shown to reduce mortality and morbidity in placebo‐controlled trials, ARBs have not. Therefore, a comparison of the efficacies of these two drug classes in primary hypertension for preventing total mortality and cardiovascular events is important.

Objectives

To compare the effects of ACE inhibitors and ARBs on total mortality and cardiovascular events, and their rates of withdrawals due to adverse effects (WDAEs), in people with primary hypertension.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Hypertension Group Specialized Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and the ISI Web of Science up to July 2014. We contacted study authors for missing and unpublished information, and also searched the reference lists of relevant reviews for eligible studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials enrolling people with uncontrolled or controlled primary hypertension with or without other risk factors. Included trials must have compared an ACE inhibitor and an ARB in a head‐to‐head manner, and lasted for a duration of at least one year. If background blood pressure lowering agents were continued or added during the study, the protocol to do so must have been the same in both study arms.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

Nine studies with 11,007 participants were included. Of the included studies, five reported data on total mortality, three reported data on total cardiovascular events, and four reported data on cardiovascular mortality. No study separately reported cardiovascular morbidity. In contrast, eight studies contributed data on WDAE. Included studies were of good to moderate quality. There was no evidence of a difference between ACE inhibitors and ARBs for total mortality (risk ratio (RR) 0.98; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88 to 1.10), total cardiovascular events (RR 1.07; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.19), or cardiovascular mortality (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.13). Conversely, a high level of evidence indicated a slightly lower incidence of WDAE for ARBs as compared with ACE inhibitors (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.74 to 0.93; absolute risk reduction (ARR) 1.8%, number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) 55 over 4.1 years), mainly attributable to a higher incidence of dry cough with ACE inhibitors. The quality of the evidence for mortality and cardiovascular outcomes was limited by possible publication bias, in that several studies were initially eligible for inclusion in this review, but had no extractable data available for the hypertension subgroup. To this end, the evidence for total mortality was judged to be moderate, while the evidence for total cardiovascular events was judged to be low by the GRADE approach.

Authors' conclusions

Our analyses found no evidence of a difference in total mortality or cardiovascular outcomes for ARBs as compared with ACE inhibitors, while ARBs caused slightly fewer WDAEs than ACE inhibitors. Although ACE inhibitors have shown efficacy in these outcomes over placebo, our results cannot be used to extrapolate the same conclusion for ARBs directly, which have not been studied in placebo‐controlled trials for hypertension. Thus, the substitution of an ARB for an ACE inhibitor, while supported by evidence on grounds of tolerability, must be made in consideration of the weaker evidence for the efficacy of ARBs regarding mortality and morbidity outcomes compared with ACE inhibitors. Additionally, our data mostly derives from participants with existing clinical sequelae of hypertension, and it would be useful to have data from asymptomatic people to increase the generalizability of this review. Unpublished subgroup data of hypertensive participants in existing trials comparing ACE inhibitors and ARBs needs to be made available for this purpose.

Plain language summary

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus angiotensin receptor blockers for primary hypertension

Background

Hypertension, or persistent high blood pressure above 140/90 mmHg, is a prevalent risk factor that is associated with strokes and heart disease. To prevent these events, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are used widely to treat hypertension, with ARBs often substituted for ACE inhibitors due to a reputation of having fewer side effects. However, while studies have shown a preventive benefit for ACE inhibitors, there are no such studies for ARBs. Therefore, we aimed to further test this substitution by reviewing studies that directly compared an ACE inhibitor and an ARB.

Study characteristics

We searched scientific databases for randomized controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) of people with uncontrolled or controlled hypertension with or without other risk factors (an aspect of a person's condition, lifestyle or environment that affects the probability of occurrence of a disease). The evidence is current to July 2014.

Key results

We found no reliable difference between ACE inhibitors and ARBs for total deaths, deaths due to heart disease, or total heart disease and stroke. However, our conclusions alone cannot be taken to mean that ARBs would show similar benefit like ACE inhibitors if compared with placebo (a dummy treatment). ARBs do have a 1.8% lower chance of being stopped due to side effects over 4.1 years, meaning that for every 55 people treated with an ARB instead of an ACE inhibitor for 4.1 years, one person would be spared from a side effect leading to stopping the drug. This difference in side effects was mainly due to a higher rate of dry cough in people taking ACE inhibitors.

Quality of the evidence

In summary, while ARBs are slightly better tolerated than ACE inhibitors, there is a higher quality of data supporting the use of ACE inhibitors to prevent death, strokes, and heart disease that must be considered before choosing ARBs over ACE inhibitors.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for primary hypertension.

| All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for primary hypertension | |||||

| Patient or population: people with primary hypertension Settings: multicenter, outpatient Intervention: ARBs Comparison: ACE inhibitors | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| ACE inhibitors | ARBs | ||||

| Total mortality Follow‐up: mean 4.3 years | 116 per 1000 | 114 per 1000 (102 to 128) | RR 0.98 (0.88 to 1.10) | 10,248

(5 studies, 3 with events) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

| Total cardiovascular events Follow‐up: mean 4.5 years | 179 per 1000 | 192 per 1000 (172 to 213) | RR 1.07 (0.96 to 1.19) | 5499

(3 studies, 1 with events) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

| Withdrawal due to adverse effects Follow‐up: mean 4.1 years | 113 per 1000 | 94 per 1000 (84 to 105) |

RR 0.83

(0.74 to 0.93) ARR 1.8%, NNTB 55 |

10,963 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ARR: absolute risk reduction; CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; RR: risk ratio.; WDAE: withdrawal due to adverse effects. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. Footnotes 1. At least 9 initially eligible studies may have unpublished data for mortality or morbidity (or both), and at least 14 initially eligible studies may have unpublished subgroup data for people with hypertension. 2. Only 1 trial found with extractable data (ONTARGET 2008), but data for the full hypertensive subgroup was not available for this outcome. A further 6 included studies (1462 participants) may have unpublished data on this outcome. 3. For each outcome, the total incidence in the ACE inhibitor group (control group) was used as the assumed risk. | |||||

Background

Description of the condition

Hypertension is a risk factor associated with cardiovascular events such as stroke and myocardial infarction (MI).

Description of the intervention

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are widely prescribed for the treatment of primary hypertension.

How the intervention might work

ACE inhibitors and ARBs inhibit the renin‐angiotensin system (RAS) but have different sites of action; ACE inhibitors inhibit the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, while the ARBs antagonize receptor binding of angiotensin II to AT1 receptors. Therefore, it is often assumed that the two drug classes have similar efficacy in cardiovascular disease prevention. To this end, two Cochrane reviews, one analyzing ACE inhibitors and the other ARBs, have shown similar efficacy in lowering trough blood pressure (ACE inhibitors: Heran 2009a; ARBs: Heran 2009b). However, the efficacy of a drug in lowering blood pressure cannot be taken as a definitive indicator of its efficacy in reducing mortality and morbidity. For example, low dose thiazides were more efficacious in reducing coronary heart disease than high dose thiazides, despite the two having similar efficacy in lowering blood pressure (Wright 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

The substitution of ARBs for ACE inhibitors for various indications is attractive primarily because of the reputation of ARBs for being better tolerated, but the validity of this substitution in terms of comparative efficacy on mortality and morbidity should be considered. For primary hypertension, while some evidence exists for first‐line ACE inhibitors in preventing cardiovascular events (Wright 2009), the same Cochrane review found no trials comparing first‐line ARBs against placebo.

To investigate the validity of substituting ARBs for ACE inhibitors in treating primary hypertension, the most reliable method would be head‐to‐head comparisons in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). As no Cochrane review to‐date has examined the evidence from such trials, this review aims to compare ACE inhibitors and ARBs for their effects on mortality, morbidity, and withdrawals due to adverse effects (WDAE) when used for the treatment of primary hypertension.

Objectives

To compare the effects of ACE inhibitors and ARBs on total mortality and cardiovascular events, and their rates of WDAEs, in people with primary hypertension.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies:

directly compared an ACE inhibitor and an ARB;

randomized participants to the ACE inhibitor group or the ARB group;

had the same protocol regarding continuation or discontinuation of prestudy blood pressure lowering therapy in both arms;

had the same protocol for adding background blood pressure lowering therapy during the trial in both arms;

had a prespecified duration of at least one year;

were double blinded when included for WDAE.

We did not include studies that did not report extractable data on any outcome pertinent to this review in our analyses, since the contribution of any potentially missing data to the effect estimate is unknown. Where possible, we contacted the study authors for any unpublished data. If extractable data were still unavailable, we classified the study in the review as an excluded study; however, should additional data become available in the future, it will be reconsidered for inclusion (see Differences between protocol and review). Conversely, if a study met our inclusion criteria but had zero events, we included it in the qualitative report for added inclusiveness and generalizability.

Types of participants

We included participants with uncontrolled hypertension, defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of at least 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of at least 90 mmHg (or both) at baseline. Co‐morbid conditions did not comprise an exclusion criterion. We also included participants who had controlled hypertension at baseline provided that their original diagnosis of hypertension was made with our criteria of SBP greater than 140 mmHg or DBP greater than 90 mmHg (or both). If only part of a study's sample size met our criteria for participants, we requested subgroup data from the study authors.

Types of interventions

Included trials compared therapy with any ACE inhibitor versus any ARB. Trials may have included other background blood pressure lowering therapies provided that the usage of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB be the only prespecified difference in intervention between the two groups. Studies that included the addition of background therapies after randomization must have prespecified and followed the same protocol for doing so in both arms. Likewise, the protocol for continuation or discontinuation of prior blood pressure lowering therapies before randomization must have been the same in both arms.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Mortality and morbidity, subcategorized as follows (Musini 2010):

total mortality as death from all causes;

cardiovascular mortality as coronary heart disease mortality (fatal MI, sudden or rapid cardiac death) and cerebrovascular mortality (fatal stroke) combined;

cardiovascular morbidity as coronary heart disease morbidity (nonfatal MI) and cerebrovascular morbidity (nonfatal stroke) combined;

total cardiovascular events as fatal and nonfatal MI, other coronary heart disease mortality, fatal and nonfatal stroke, fatal congestive heart failure and hospitalizations for congestive heart failure.

Secondary outcomes

Withdrawals due to adverse effects (WDAE).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases for primary studies: the Hypertension Group Specialised Register (1946 to July 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to February 2014), and Ovid EMBASE (1974 to January 2014).

We searched electronic databases using a strategy combining the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying RCTs in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision) with selected MeSH terms and free‐text terms relating to ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and hypertension. We applied no language restrictions. The MEDLINE search strategy (Appendix 1) was translated into CENTRAL (Appendix 2), EMBASE (Appendix 3), and the Hypertension Group Specialised Register (Appendix 4) using the appropriate controlled vocabulary as applicable.

We searched the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) and The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched for related reviews.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all papers and relevant reviews identified. We contacted the authors of relevant papers regarding any further published or unpublished work and the authors of trials reporting incomplete information to request the missing information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (ECKL, BSH) independently examined the titles and abstracts of citations identified by the electronic searches for possible inclusion. We retrieved full‐text publications of potentially relevant studies (and translated them into English where required) and two review authors (ECKL, BSH) then independently determined study eligibility using a standardized inclusion form. We resolved any disagreements about study eligibility by discussion and, if necessary, a third review author (JMW) arbitrated.

Data extraction and management

One review author (ECKL or BSH) extracted data from included studies using a standardized data extraction form and a second review author (BSH or ECKL) checked entries. If data were presented numerically (in tables or text) and graphically (in figures), we used the numeric data because of possible measurement error when estimating from graphs. A second review author confirmed all numeric calculations and extractions from graphs or figures. We resolved any discrepancies by consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The review authors used The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessment of bias to categorize studies as having low, unclear, or high risk of bias for sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, loss of blinding, selective reporting, incomplete reporting of outcomes, and other sources of bias (Higgins 2011).

Measures of treatment effect

Combined outcomes represented participants with at least one event in the outcome. We presented treatment effects as risk ratios (RR). We presented the absolute risk reduction (ARR) and number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) for statistically significant results.

Assessment of heterogeneity

This review considered a P value of 0.10 or less from the Chi2 test as statistically significant for heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). If we had identified statistically significant heterogeneity, we had planned to use a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis. Since a random‐effects model can over‐emphasize smaller studies, we had planned a sensitivity analysis to gauge the effects of using a random‐effects model versus a fixed‐effect model on the observed intervention effect.

Data synthesis

The first analysis pooled all drugs and drug doses within each class as long as the doses were within the manufacturer‐recommended dose range for the drug. This pooling assumed that drugs in each class and their respective doses used were equi‐efficacious. We had planned a subgroup analysis to test this assumption if possible.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Potential subgroups for analysis included:

sex;

age: below 60, 60 to 80, over 80 years;

different drugs within a class;

dose of drug (measured as proportion of maximum manufacturer's recommended dose) taken;

high‐risk participants or participants with co‐morbid conditions;

participants with a previous history of cardiovascular morbidity;

different background therapies.

Sensitivity analysis

The review authors performed sensitivity analyses to elucidate the impact of studies with a high risk of bias on the observed effects of interventions. In addition, as the only significant outcome in our review was WDAE, we decided to conduct a post‐hoc sensitivity analysis to investigate the cause(s) of WDAE responsible for the difference between the ACE inhibitor and ARB arms.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

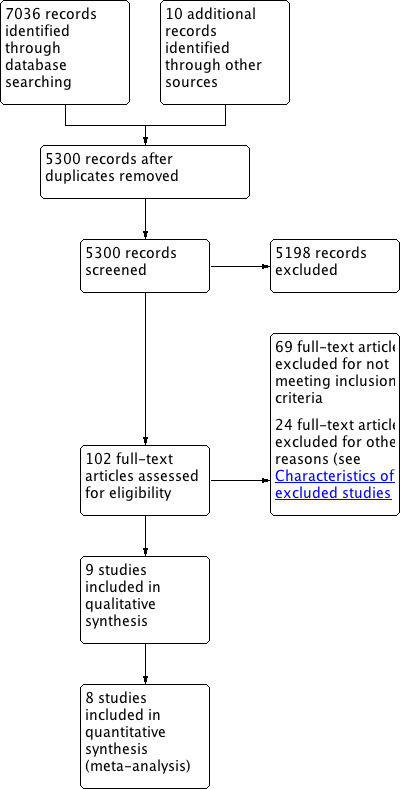

Our search revealed 7046 references, which were reduced to 5300 after de‐duplication. After screening titles and abstracts, we obtained the full‐text articles of 102 studies. Of these studies, we excluded 69 based on not meeting our inclusion criteria. In addition, we excluded a further 24 studies due to lack of outcomes pertinent to this review, inclusion of participants without hypertension with unavailability of subgroup data for the hypertensive subgroup, or high risk of bias (see Characteristics of excluded studies for details). Prior to the decision to exclude these latter studies, we contacted the study authors for additional data to verify our decision where possible.

Ultimately, nine studies (10 publications) met the inclusion criteria and eight had events to compare the effects of ACE inhibitors with ARBs on mortality, morbidity, WDAE, or a combination of these in people with primary hypertension (Figure 1).

1.

Identification and assessment of records for inclusion into the review.

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies for details.

We included nine RCTs with 11,007 participants in our review, of which eight studies (10,963 participanys) contributed to our quantitative analyses. One study (44 participants) did not contribute to the effect estimates of our meta‐analyses due to lack of events for mortality/morbidity outcomes and nonextractable data for WDAE (Sozen 2009) (see Effects of interventions). However, we included this study in our qualitative discussion for added generalizability and inclusiveness, as the study mets our inclusion criteria.

All studies had a prespecified follow‐up period of at least one year. In addition, one study had five years of follow‐up (DETAIL 2004), one had three years (Sozen 2009), one had 1.4 years (Spoelstra‐de 2006), and one had 4.5 years (ONTARGET 2008). Many of the studies were conducted at multiple centres in various geographic locations (DETAIL 2004, Northern Europe; Bremner 1997, UK; Lacourciere 2000, Canada; ONTARGET 2008, 40 countries).

Participants ranged from 55 years old (ONTARGET 2008) to 72 years old (Bremner 1997), with an approximately equal representation of men and women. One study further included participants with a mean age of 45 years (Sozen 2009). The mean blood pressure of participants in studies ranged from 143/87 mmHg (Fogari 2012) to 172/102 mmHg (Bremner 1997). Therefore, data obtained were almost exclusively from participants whose hypertension was uncontrolled prior to initiating an ACE inhibitor or ARB. Co‐morbidities and risk factors of participants included a history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, atrial fibrillation, and smoking.

ACE inhibitors studied included enalapril (DETAIL 2004; Lacourciere 2000), ramipril (Fogari 2008; Fogari 2011; Fogari 2012; ONTARGET 2008), and lisinopril (Bremner 1997; Spoelstra‐de 2006). ARBs included telmisartan (DETAIL 2004; Fogari 2011; ONTARGET 2008), losartan (Lacourciere 2000), candesartan (Spoelstra‐de 2006), and valsartan (Bremner 1997; Fogari 2008; Fogari 2012). In addition, one study included fosinopril, quinapril, and irbesartan (Sozen 2009).

We attempted to contact authors of included studies that did not contain all of the primary and secondary outcomes pertinent to this review in the report, or where the study population included participants both with and without hypertension. Dr. Barnett and Dr. Yusuf provided subgroup data for the participants with hypertension in DETAIL 2004 (Dr. Barnett) and ONTARGET 2008 (Dr. Yusuf) in response to our inquiry.

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies for details.

Several initially eligible studies had included participants both with and without hypertension. However, we did not include these studies in our analyses due to unavailability of subgroup data on the participants with hypertension (Derosa 2011; Didangelos 2006; el‐Agroudy 2003; ELITE II 2000; Hou 2007; Nakao 2003; OPTIMAAL 2002; Schram 2005; Sengul 2006; Shoda 2006; Tutuncu 2001; Ulusoy 2010; VALIANT 2003; Yip 2008). Four studies were eligible for inclusion but did not report outcomes pertinent to this review (Akinboboye 2002; Guntekin 2008;Rizzoni 2005; Veronesi 2007), while one study reported such outcomes but only at 12 weeks, which was less than the prespecified duration of follow‐up for this review (Franke 1997). One study allocated participants by date of birth and had a significant number of unaccounted participants at the one year mark, and, therefore, we excluded it due to a high risk of selection bias and attrition bias (CORD 2009). We excluded one study due to a high risk of reporting bias because it reported only withdrawals due to cough and angioedema, and more comprehensive information on WDAE was not available after contacting the authors (Neutel 1999). Three studies were not blinded and reported only WDAE among the outcomes of interest to this review (Ichihara 2005; Nakamura 2010; Suzuki 2004). Since a lack of blinding can bias WDAE, we excluded these studies for this outcome. In summary, 14 initially eligible studies contained unextractable subgroup data for participants with hypertension, and nine initially eligible studies did not report mortality or morbidity (or both). Wherever possible, we attempted to contact authors for these data.

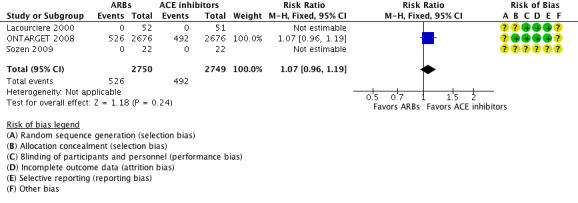

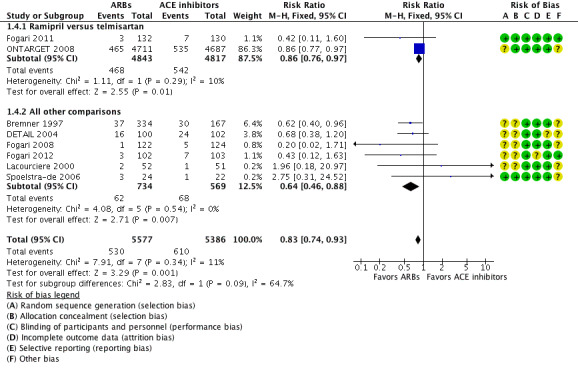

Risk of bias in included studies

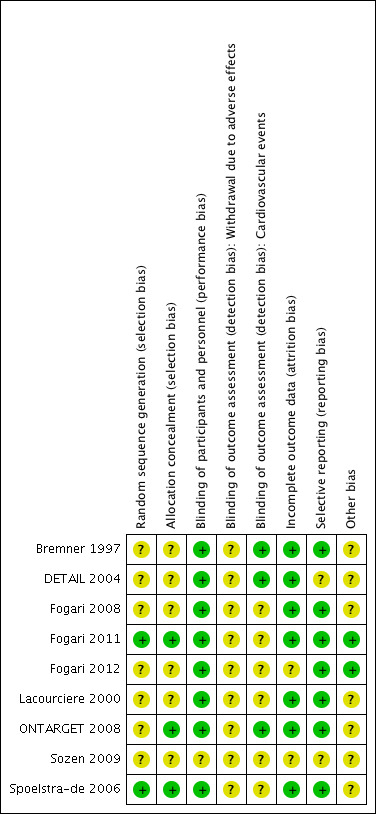

See Characteristics of included studies table and Figure 2 for more details.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All included studies reported randomization, but most did not mention the sequence generation process or method of allocation concealment (Bremner 1997; DETAIL 2004; Fogari 2008; Fogari 2012; Lacourciere 2000; Sozen 2009). In these studies, we deemed selection bias to be unclear. However, the baseline participant characteristics tables of these studies revealed no significant differences between study arms indicative of inadequate randomization.

Blinding

One study did not mentioned blinding (Sozen 2009); the other eight studies reported a double‐blind design and, therefore, we deemed them to have a low risk of performance bias. Studies that contained and reported cardiovascular events had blinded assessment of these events (Bremner 1997; DETAIL 2004; ONTARGET 2008). For studies that contributed data to WDAE, it was unclear whether blinding was lifted prior to the final decision to withdraw these participants, and, therefore, we deemed detection bias for this outcome unclear (Bremner 1997; DETAIL 2004; Fogari 2008; Fogari 2011; Fogari 2012; Lacourciere 2000; Spoelstra‐de 2006).

Incomplete outcome data

Five studies explicitly accounted for all participants in each study arm, including those whose data were unavailable due to loss to follow‐up (Bremner 1997; Fogari 2008; Fogari 2012; Lacourciere 2000; Spoelstra‐de 2006). Of these studies, the rate of discontinuation not due to adverse effects were generally low and equal between study arms. Two studies did not explicitly account for participants lost to follow‐up, although they did use intent‐to‐treat analysis, and we therefore judged them to have a low‐risk of attrition bias (DETAIL 2004; Fogari 2011). One study had an unclear risk of attrition bias because it was unclear whether the decision to withdraw participants for "uncontrolled blood pressure" was prespecified in the study's protocol, and the blood pressure threshold for such withdrawal was also not defined (Fogari 2012). However, the number of participants withdrawn for this purpose was about equal in the two arms (five for ramipril, four for valsartan), and, therefore, the effects of this action on WDAE, the only reported outcome in the study pertinent to this review, should be minimized. One study had a high rate of discontinuations (43%), and although reasons were given, the distribution of these discontinuations among the study arms was not reported (Sozen 2009).

Selective reporting

The protocol for ONTARGET 2008 (Teo 2004) had prespecified hypertension to be a subgroup for analysis, but did not specify the definition of this subgroup, such as a blood pressure threshold, or whether participants with controlled hypertension were included. In the published study, participants were grouped into tertiles according to SBP for subgroup analysis (SBP less than 134 mmHg, SBP between 134 mmHg and 150 mmHg, SBP greater than 150 mmHg), but the number of participants in none of these subgroups matched the reported percentage of participants with hypertension in the total sample size (69%). A rationale for this stratification was not available after correspondence with the authors. However, the authors provided data for the subgroup with hypertension as defined in this review for all outcomes except total cardiovascular events, which was already published as a subgroup analysis for the cohort with baseline SBP greater than 150 mmHg. Therefore, we judged this study to have a low risk of reporting bias overall.

One study had an unclear risk of reporting bias because only cardiovascular mortality and WDAE were extractable from the subgroup data provided by the authors (DETAIL 2004). In addition, while one study reported WDAE, these data were not reported separately for each study arm, and, therefore, were not extractable (Sozen 2009).

All other studies reported all prespecified outcomes, and, therefore, we judged them as having a low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Boehringer Ingelheim, manufacturer of telmisartan (Micardis®) supported one study comparing telmisartan with enalapril (DETAIL 2004). In particular, the company supported "data handling and trial management." However, statistical analyses were predetermined by "an independent scientific steering committee." One study compared telmisartan with ramipril, and was supported by a grant from Boehringer Ingelheim, along with grants from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario and the Canadian Institues of Health Research (ONTARGET 2008). Representatives from the company were involved in the operations committee, but their degree of involvement in data analysis and manuscript drafting was not stated.

One study was funded by AstraZeneca, manufacturer of lisinopril (Zestril®) and candesartan (Hytacand®), but the company "had no influence on the data analyses or manuscript preparation" (Spoelstra‐de 2006).

One study was supported by a grant from Merck Frosst Canada & Co., manufacturer of enalapril (Vasotec®) and losartan (Cozaar®), which comprised the two arms of the trial (Lacourciere 2000). Involvement of the company in other elements of the study was not described.

Three studies reported no conflicts of interest or industrial financial support (Fogari 2008; Fogari 2011; Fogari 2012). One study provided no information for industrial support (Bremner 1997). Lastly, the authors of one study reported no conflicts of interest, but information on study funding was not reported (Sozen 2009).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1 for details.

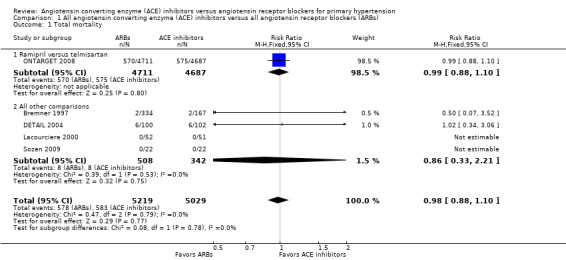

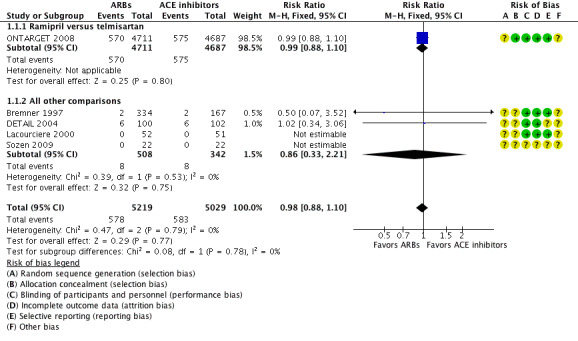

Among five (10,248 participants) included studies that reported total mortality (Bremner 1997; DETAIL 2004; Lacourciere 2000; ONTARGET 2008; Sozen 2009), three (10,101 participants) had events for total mortality (Bremner 1997; DETAIL 2004, ONTARGET 2008). There was no difference between ACE inhibitors and ARBs (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.10; Analysis 1.1) (Figure 3). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity across the trials included for this outcome (P value = 0.77).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), Outcome 1 Total mortality.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), outcome: 1.1 Total mortality.

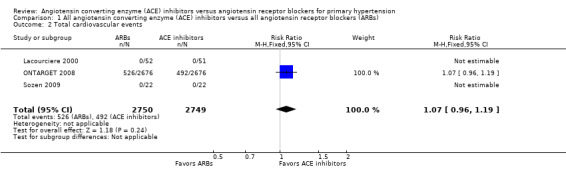

Three (5499 participants) of the included studies reported total cardiovascular events (Lacourciere 2000; ONTARGET 2008; Sozen 2009), but only one (5352 participants) had events for total cardiovascular events (ONTARGET 2008). There was no difference between ACE inhibitors and ARBs (RR 1.07; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.19; Analysis 1.2) (Figure 4). However, these data did not include all participants in the ONTARGET 2008 study that met our review's criteria for hypertension (as explained under Selective reporting (reporting bias)).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), Outcome 2 Total cardiovascular events.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), outcome: 1.2 Total cardiovascular events.

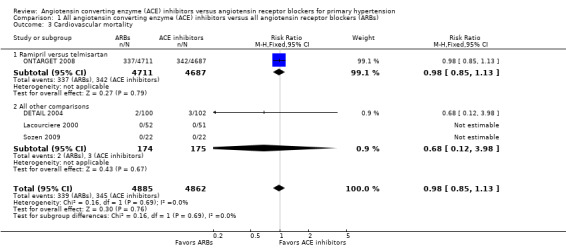

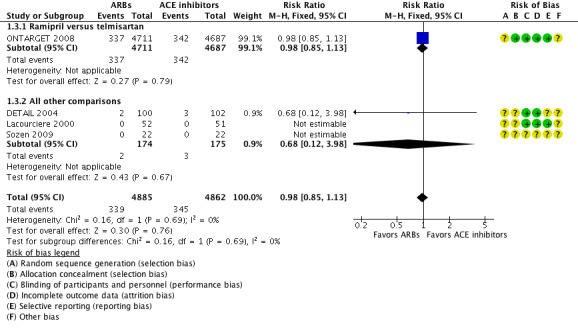

Among four (9747 participants) included studies that reported total cardiovascular mortality (DETAIL 2004; Lacourciere 2000; ONTARGET 2008; Sozen 2009), two (9600 participants) had events for total cardiovascular mortality (DETAIL 2004; ONTARGET 2008). There was no difference between ACE inhibitors and ARBs (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.13; Analysis 1.3) (Figure 5). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity across the trials included for this outcome (P value = 0.69).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), Outcome 3 Cardiovascular mortality.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), outcome: 1.3 Cardiovascular mortality.

Two (147 participants) of the included studies reported cardiovascular morbidity, but neither study had events for this outcome (Lacourciere 2000; Sozen 2009).

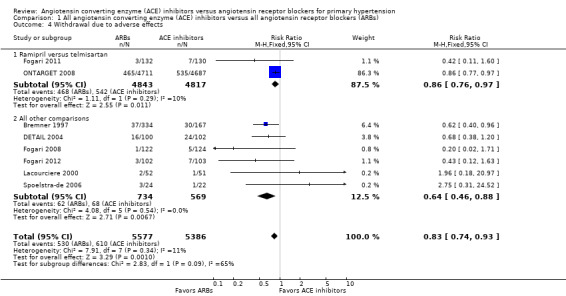

Pooling of the eight studies that reported WDAE resulted in a sample size of 10,963 participants that showed a lower rate of WDAEs for ARBs over a mean duration of 4.1 years (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.74 to 0.93; ARR 1.8%, NNTB = 55; Analysis 1.4) (Bremner 1997; DETAIL 2004; Fogari 2008; Fogari 2011; Fogari 2012; Lacourciere 2000; ONTARGET 2008; Spoelstra‐de 2006). There was no significant heterogeneity across trials for this outcome (P value = 0.34) (Figure 6). Specific reasons for WDAE were available for all studies except two (DETAIL 2004; ONTARGET 2008). Of the events in WDAE with specific reasons listed, 43% (22/51 events) in the ACE inhibitor arm was due to cough, as opposed to 4% (2/49 events) in the ARB arm. A post‐hoc sensitivity analysis involving only those studies reporting specific reasons for WDAE showed that if cough was taken out of the WDAE analysis, the results for WDAE became nonsignificant. Other reasons for withdrawal reported for ACE inhibitors include atrial flutter, edema, rash, rise in creatinine, and one case of glottis edema. For ARBs, other reasons for withdrawal included dizziness, hypotension, palpitations, dyspnea, headache, nausea, edema, urticaria, and macroalbuminuria. It should be noted that this post‐hoc analysis does not include ONTARGET 2008, which contributed the most weight in our meta‐analysis, since the individual reasons for WDAE were not available for the subgroup of participants with hypertension in this study.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), Outcome 4 Withdrawal due to adverse effects.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), outcome: 1.4 Withdrawal due to adverse effects.

A sensitivity analysis including studies excluded for high risk of bias (Neutel 1999), or lack of blinding in the context of WDAE (Ichihara 2005; Nakamura 2010; Suzuki 2004), did not affect the statistical significance of any outcome.

A prespecified subgroup analysis of individual ACE inhibitors and ARBs comparing ramipril versus telmisartan also showed no difference in total mortality (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.10), cardiovascular events (RR 1.07; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.19), or cardiovascular mortality (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.13). Statistical significance was preserved with regards to WDAE (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.76 to 0.97; ARR 1.6%, NNTB 63 over 4.4 years). Comparisons between other individual ACE inhibitors and ARBs were too underpowered to represent a meaningful subgroup analysis.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Data exist from a large sample size comparing ACE inhibitors versus ARBs for mortality and morbidity in people with hypertension, with the majority of these data derived from a single large study (ONTARGET 2008). Three studies contained data for total mortality, one study contained data for total cardiovascular events, and two studies contained data for total cardiovascular mortality. A further two studies reported these outcomes but had no events. There was no evidence of a difference between ACE inhibitors and ARBs on total mortality, total cardiovascular events, or cardiovascular mortality (Table 1). Separate data for cardiovascular morbidity were unavailable from the included studies.

In contrast, eight studies reported extractable data for WDAE, and ARBs were slightly superior to ACE inhibitors in this outcome. In a post‐hoc sensitivity analysis involving only studies that reported reasons for WDAE, the results for WDAE became nonsignificant when dry cough was eliminated from the analysis, but this change was not seen with other reported adverse effects.

Subgroup analysis of studies comparing ramipril versus telmisartan showed no change to the statistical significance of any outcome. Comparisons of other individual ACE inhibitors and ARBs were too underpowered to be meaningful.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Most of our data were derived from one trial (ONTARGET 2008), which included only participants with a history of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, or peripheral vascular disease, or diabetes with end‐organ damage. Therefore, the ability to extrapolate our results to treating asymptomatic hypertension may be limited. However, our search revealed several studies that met our inclusion criteria but did not have subgroup data available for hypertension. If these data are made available, our meta‐analysis may become more generalizable when it is updated.

The baseline blood pressures represented in the pooled population largely ranged from mild to moderate hypertension, with mean blood pressures ranging from 143/87 mmHg (Fogari 2012) to 172/102 mmHg (Bremner 1997). Therefore, our analysis was confined largely to people whose hypertension was uncontrolled prior to starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB.

In terms of drugs represented, the analysis of total mortality included enalapril, lisinopril, ramipril, valsartan, and telmisartan; total cardiovascular events included only ramipril and telmisartan; and cardiovascular mortality included ramipril, enalapril, and telmisartan. The analysis of WDAE included enalapril, lisinopril, ramipril, losartan, candesartan, telmisartan, and valsartan. Due to our analysis being mostly represented by one comparison ‐ that of ramipril and telmisartan (ONTARGET 2008) ‐ our analyses were underpowered to differentiate the effects of different drugs and doses via subgroup analysis. However, subgroup analyses of the ramipril versus telmisartan comparison revealed no change in statistical significance to any outcome compared with the overall meta‐analysis. Likewise, our analyses lacked the variation in use of background therapy to detect differences between background therapy and monotherapy in comparing ACE inhibitors with ARBs. To this end, while study arms in our included studies did not differ in their protocols for background therapy, we could not rule out differences between ACE inhibitors and ARBs in systematic pharmacologic synergy with different background therapies.

One study contained a younger population than other included studies, but did not contribute to our quantitative analyses since it lacked events in the mortality/morbidity outcomes, and had nonextractable data for WDAE (Sozen 2009). The lack of detected events in mortality/morbidity may be attributed to the high dropout rate superimposed on an already small study, in addition to a lower‐risk study population. However, given the small study size and low‐risk study population, the impact of the high dropout rate in this study on our effect estimates is likely reduced.

Quality of the evidence

The studies containing extractable data for total mortality and cardiovascular mortality were of good quality (Bremner 1997; DETAIL 2004; ONTARGET 2008). The data for total cardiovascular events, which were based on a single large study (ONTARGET 2008), were difficult to interpret because the subgroup data for participants with hypertension seemed to deviate from the prepublished protocol (Teo 2004 under ONTARGET 2008), such that only data for participants with SBP greater than 150 mmHg were extractable (see Selective reporting (reporting bias) for details). In addition, the reported number of participants with hypertension in the total sample size differed from the sample size used for subgroup analysis. While this may have resulted from including participants with both controlled and uncontrolled hypertension in the total sample size, versus a simple stratification by blood pressure in the subgroup analysis, no definitive explanation for the discrepancy was available. Furthermore, the rationale for the sole use of SBP in stratifying subgroups was unavailable. Correspondance with the study authors indicated that there was another prespecified subgroup analysis grouping SBP into tertiles, but the rationale for this grouping remained unexplained. However, the study authors provided subgroup data for unpublished outcomes of interest to this review in response to our inquiry, and, therefore, we deemed this study to have a low risk of reporting bias.

For WDAE, we excluded studies without blinding, since a lack of blinding can bias the decision to withdraw participants. However, where blinding of a study was unclear, we attempted to contact study authors for clarification prior to exclusion. Of note, while we assumed from the blinding of personnel and participants that the decision to withdraw was made under blinded conditions, it was unknown whether any of the studies involved unblinding prior to making the final decision to withdraw participants.

Potential biases in the review process

Certain assumptions were made in our comparison of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in order to increase statistical power. The first assumption was the equi‐effectiveness of all approved doses of all drugs within either class with respect to our outcomes of interest. This assumption may have been incorrect, particularly with regards to WDAE, but the necessary subgroup analyses to test this assumption adequately would have been underpowered. In addition, to maximize inclusiveness, we included studies with background blood pressure lowering medications if they were added in an identical manner in both the ACE inhibitor and ARB arms. However, it is unknown whether the same background treatment regimen would unequally affect outcomes via unequal drug interactions with ACE inhibitors and ARBs. Once again, we lacked the variation in background therapies to perform meaningful subgroup analyses on different background medication regimens.

A retrospective exclusion of studies with a high risk of performance, detection, and reporting bias for WDAE may have introduced bias into our effect estimate for this outcome. However, we investigated this possibility via a sensitivity analysis and found no impact on statistical significance.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

While there are placebo‐controlled data supporting the use of ACE inhibitors in treating primary hypertension for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity benefit (Wright 2009), no placebo‐controlled trials have examined the use of ARBs for this indication. The conclusions of our review regarding mortality and cardiovascular outcomes provide some additional data on which to base clinical decision making, but the lack of statistical significance for these outcomes in no way establishes noninferiority of ARBs compared with ACE inhibitors. In other words, the assumption cannot be made that ARBs are superior to placebo simply by direct extrapolation from our results, without a placebo‐controlled trial of ARBs for hypertension.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In head‐to‐head comparisons of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) for primary hypertension, moderate‐quality evidence showed no difference for total mortality, while low‐quality evidence showed no difference for total cardiovascular events. However, despite the benefits that ACE inhibitors have shown over placebo for these outcomes, our results cannot be used to extrapolate the same conclusion for ARBs over placebo directly. On this note, placebo‐controlled trials on ARBs for hypertension do not exist to our knowledge and are unlikely to occur in the future for ethical reasons. In addition, ARBs were only slightly more tolerable than ACE inhibitors, with an absolute risk reduction for withdrawals due to adverse effects of 1.8% over 4.1 years, meaning that 55 people must be treated with an ARB in place of an ACE inhibitor for 4.1 years to prevent one withdrawal due to an adverse event. Furthermore, the most of our data were from a single large study including people with confirmed vascular disease or end‐organ damage, rather than people who were asymptomatic (ONTARGET 2008). In conclusion, while no evidence of a difference exists between ACE inhibitors and ARBs for total mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in treating hypertension, the small increase in tolerability for ARBs should be weighed against its less established degree of evidence of efficacy when choosing an ARB over an ACE inhibitor for hypertension.

Implications for research.

Most of our sample size was from a single study including only participants with existing vascular disease or end‐organ damage (ONTARGET 2008). However, our search revealed many studies, comparing ACE inhibitors with ARBs for other indications, that may have unpublished subgroup data for hypertension. We hope that this review may encourage the authors of such studies to make these data available to increase the generalizability of this review when it is updated. While these data may lack adequate power to detect differences on their own, they would contribute to meta‐analyses such as this one.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 August 2014 | Amended | Updated affiliation for Contact Person |

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance received from the Cochrane Hypertension Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present with Daily Update Search date: 15 February 2014 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp Angiotensin Receptor Antagonists/ 2 (angiotensin adj3 (receptor antagon$ or receptor block$)).tw. 3 arb?.tw. 4 (abitesartan or azilsartan or candesartan or elisartan or embusartan or eprosartan or forasartan or irbesartan or losartan or milfasartan or olmesartan or saprisartan or tasosartan or telmisartan or valsartan or zolasartan).tw. 5 or/1‐4 6 exp Angiotensin‐Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/ 7 angiotensin converting enzyme inhibit$.tw. 8 (ace adj2 inhibit$).tw. 9 acei.tw. 10 alacepril.tw. 11 altiopril.tw. 12 ancovenin.tw. 13 benazepril$.tw. 14 captopril.tw. 15 ceranapril.tw. 16 ceronapril.tw. 17 cilazapril$.tw. 18 deacetylalacepril.tw. 19 delapril.tw. 20 enalapril$.tw. 21 epicaptopril.tw. 22 fasidotril$.tw. 23 foroxymithine.tw. 24 fosinopril$.tw. 25 gemopatrilat.tw. 26 idapril.tw. 27 imidapril$.tw. 28 indolapril.tw. 29 libenzapril.tw. 30 lisinopril.tw. 31 moexipril$.tw. 32 moveltipril.tw. 33 omapatrilat.tw. 34 pentopril$.tw. 35 perindopril$.tw. 36 pivopril.tw. 37 quinapril$.tw. 38 ramipril$.tw. 39 rentiapril.tw. 40 saralasin.tw. 41 s nitrosocaptopril.tw. 42 spirapril$.tw. 43 temocapril$.tw. 44 teprotide.tw. 45 trandolapril$.tw. 46 utibapril$.tw. 47 zabicipril$.tw. 48 zofenopril$.tw. 49 or/6‐48 50 hypertension/ 51 hypertens$.tw. 52 exp blood pressure/ 53 (blood pressure or bloodpressure).mp. 54 or/50‐53 55 randomized controlled trial.pt. 56 controlled clinical trial.pt. 57 randomi?ed.ab. 58 placebo.ab. 59 clinical trials as topic/ 60 randomly.ab. 61 trial.ti. 62 or/55‐61 63 animals/ not (humans/ and animals/) 64 62 not 63 65 5 and 49 and 54 and 64

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

Database: Wiley ‐ Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials <2014 Issue 1> Search date: 15 January 2014 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ID Search #1 (angiotensin near/3 receptor next (antagon* or block*)):ti,ab,kw #2 (AT next 2 next receptor next (antagon* or block*)):ti,ab,kw in #3 arb*:ti,ab #4 abitesartan:ti,ab,kw #5 azilsartan.ti,ab,kw #6 candesartan:ti,ab,kw #7 elisartan:ti,ab,kw #8 embusartan:ti,ab,kw #9 eprosartan:ti,ab,kw #10 forasartan:ti,ab,kw #11 irbesartan:ti,ab,kw #12 losartan:ti,ab,kw #13 milfasartan:ti,ab,kw #14 olmesartan:ti,ab,kw #15 saprisartan:ti,ab,kw #16 tasosartan:ti,ab,kw #17 telmisartan:ti,ab,kw #18 valsartan:ti,ab,kw #19 zolasartan:ti,ab,kw #20 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19) #21 (angiotensin next converting next enzyme next inhibitor*):ti,ab,kw #22 ace near/2 inhibit*:ti,ab,kw #23 acei:ti,ab #24 alacepril:ti,ab,kw #25 altiopril:ti,ab,kw #26 ancovenin:ti,ab,kw #27 benazepril*:ti,ab,kw #28 captopril:ti,ab,kw #29 ceranapril:ti,ab,kw #30 ceronapril:ti,ab,kw #31 cilazapril*:ti,ab,kw #32 deacetylalacepril:ti,ab,kw #33 delapril:ti,ab,kw #34 enalapril*:ti,ab,kw #35 epicaptopril:ti,ab,kw #36 fasidotril*:ti,ab,kw #37 foroxymithine:ti,ab,kw #38 fosinopril*:ti,ab,kw #39 gemopatrilat:ti,ab,kw #40 idapril:ti,ab,kw #41 imidapril*:ti,ab,kw #42 indolapril:ti,ab,kw #43 libenzapril:ti,ab,kw #44 lisinopril:ti,ab,kw #45 moexipril*:ti,ab,kw #46 moveltipril:ti,ab,kw #47 omapatrilat:ti,ab,kw #48 pentopril*:ti,ab,kw #49 perindopril*:ti,ab,kw #50 pivopril:ti,ab,kw #51 quinapril*:ti,ab,kw #52 ramipril*:ti,ab,kw #53 rentiapril:ti,ab,kw #54 saralasin:ti,ab,kw #55 nitrosocaptopril:ti,ab,kw #56 spirapril*:ti,ab,kw #57 temocapril*:ti,ab,kw #58 teprotide:ti,ab,kw #59 trandolapril*:ti,ab,kw #60 utibapril*:ti,ab,kw #61 zabicipril*:ti,ab,kw #62 zofenopril*:ti,ab,kw #63 (#21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29 or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33 or #34 or #35 or #36 or #37 or #38 or #39 or #40 or #41 or #42 or #43 or #44 or #45 or #46 or #47 or #48 or #49 or #50 or #51 or #52 or #53 or #54 or #55 or #56 or #57 or #58 or #59 or #60 or #61 or #62) #64 MeSH descriptor: [Hypertension] this term only #65 hypertens*:ti,ab #66 MeSH descriptor: [Blood Pressure] explode all trees #67 ("blood pressure" or bloodpressure):ti,ab #68 (#64 or #65 or #66 or #67) #69 (#20 and #63 and #68)

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

Database: EMBASE <1974 to 2014 Week 2> Search date: 15 January 2014 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp Angiotensin Receptor Antagonist/ 2 (angiotensin adj3 (receptor antagon$ or receptor block$)).tw. 3 arb?.tw. 4 (abitesartan or azilsartan or candesartan or elisartan or embusartan or eprosartan or forasartan or irbesartan or losartan or milfasartan or olmesartan or saprisartan or tasosartan or telmisartan or valsartan or zolasartan).tw. 5 or/1‐4 6 exp Dipeptidyl Carboxypeptidase Inhibitor/ 7 angiotensin converting enzyme inhibit$.tw. 8 (ace adj2 inhibit$).tw. 9 acei.tw. 10 alacepril.tw. 11 altiopril.tw. 12 ancovenin.tw. 13 benazepril$.tw. 14 captopril.tw. 15 ceranapril.tw. 16 ceronapril.tw. 17 cilazapril$.tw. 18 deacetylalacepril.tw. 19 delapril.tw. 20 enalapril$.tw. 21 epicaptopril.tw. 22 fasidotril$.tw. 23 foroxymithine.tw. 24 fosinopril$.tw. 25 gemopatrilat.tw. 26 idapril.tw. 27 imidapril$.tw. 28 indolapril.tw. 29 libenzapril.tw. 30 lisinopril.tw. 31 moexipril$.tw. 32 moveltipril.tw. 33 omapatrilat.tw. 34 pentopril$.tw. 35 perindopril$.tw. 36 pivopril.tw. 37 quinapril$.tw. 38 ramipril$.tw. 39 rentiapril.tw. 40 saralasin.tw. 41 s nitrosocaptopril.tw. 42 spirapril$.tw. 43 temocapril$.tw. 44 teprotide.tw. 45 trandolapril$.tw. 46 utibapril$.tw. 47 zabicipril$.tw. 48 zofenopril$.tw. 49 or/6‐48 50 exp hypertension/ 51 hypertens$.tw. 52 ((elevat$ or high$ or low$ or rais$) adj2 blood pressure).tw. 53 or/50‐52 54 randomized controlled trial/ 55 crossover procedure/ 56 double‐blind procedure/ 57 (randomi$ or randomly).tw. 58 (crossover$ or cross‐over$).tw. 59 placebo$.tw. 60 (doubl$ adj blind$).tw. 61 allocat$.ab. 62 comparison.ti. 63 trial.ti. 64 or/54‐63 65 (animal$ not (human$ and animal$)).mp. 66 64 not 65 67 5 and 49 and 53 and 66 68 67 and (2012$ or 2013$).em.

Appendix 4. Hypertension Group Specialised Register search strategy

Database: Hypertension Group Specialised Register Search date: 15 July 2014 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ #1 (((abitesartan or azilsartan or candesartan or elisartan or embusartan or eprosartan or forasartan or irbesartan or losartan or milfasartan or olmesartan or saprisartan or tasosartan or telmisartan))) AND ( INREGISTER) #2 (((valsartan or zolasartan or KT3‐671 or atacand or teveten or avapro or cozaar or benicar or micardis or diovan))) AND ( INREGISTER) #3 #1 OR #2 OR #3 #4 (((angiotensin converting or angiotensin‐converting or ace inhibit* or acei or carboxypeptidase inhibit* or kininase))) AND ( INREGISTER) #5 (((alacepril or altiopril or ancovenin or benazepril or captopril or ceronapril or cilazapril or deacetylalacepril or delapril or enalapril or epicaptopril))) AND ( INREGISTER) #6 #5 OR #6 #7 #4 AND #7

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. All angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus all angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total mortality | 5 | 10248 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.88, 1.10] |

| 1.1 Ramipril versus telmisartan | 1 | 9398 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.88, 1.10] |

| 1.2 All other comparisons | 4 | 850 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.33, 2.21] |

| 2 Total cardiovascular events | 3 | 5499 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.96, 1.19] |

| 3 Cardiovascular mortality | 4 | 9747 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.85, 1.13] |

| 3.1 Ramipril versus telmisartan | 1 | 9398 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.85, 1.13] |

| 3.2 All other comparisons | 3 | 349 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.12, 3.98] |

| 4 Withdrawal due to adverse effects | 8 | 10963 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.74, 0.93] |

| 4.1 Ramipril versus telmisartan | 2 | 9660 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.76, 0.97] |

| 4.2 All other comparisons | 6 | 1303 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.46, 0.88] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bremner 1997.

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blind, controlled design Prespecified duration of follow‐up: 52 weeks % lost to follow‐up: 0.6% % discontinuation not due to adverse effects: 5.4% Total % premature discontinuation for any reason: 24.1% |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 501 (167 for lisinopril, 334 for valsartan, due to 2:1 randomization) Mean baseline BP: 172/102 mmHg (sitting) Mean age: 71.8 years % male: 44.7% % white race: not reported Other risk factors: not reported BP requirement for entry: mild‐to‐moderate hypertension, defined as "sitting diastolic blood pressure ≥ 96 mmHg and ≤ 110 mmHg after a two week placebo run‐in period" Exclusion criteria: symptomatic heart failure; severe angina pectoris; significant valvular heart disease; second‐ or third‐degree heart block; malignant hypertension; history of cerebrovascular accident or MI within the last 3 months; history of heart failure within last 6 months; significant hepatic, renal, or gastrointestinal disease Location: UK |

|

| Interventions | BP‐lowering agents discontinued, 2‐week placebo run‐in period Participants were assessed at 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 26, 39, and 52 weeks. Study medications were uptitrated as below if sitting DBP ≥ 90 mmHg. Downtitration also occurred "based on clinical judgment" ACE inhibitor arm titration steps: Step 1: lisinopril 2.5 mg daily Step 2: lisinopril 10 mg daily Step 3: lisinopril 20 mg daily Step 4: lisinopril 20 mg + HCTZ 12.5 mg daily Step 5: lisinopril 20 mg + HCTZ 25 mg daily ARB arm titration steps: Step 1: valsartan 40 mg daily Step 2: valsartan 80 mg valsartan daily Step 3: valsartan 80 mg valsartan daily (no change from step 2) Step 4: valsartan 80 mg valsartan + HCTZ 12.5 mg HCTZ daily Step 5: valsartan 80 mg valsartan + HCTZ 25 mg daily Criteria for withdrawal from trial included: intolerable symptoms from lack of therapeutic response or adverse effects, or a sitting DBP ≥ 110 mmHg, or a sitting DBP ≥ 90 mmHg while on step 5. No additional BP‐lowering drug was allowed for the entire trial |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality: death due to all causes WDAE: did not breakdown different adverse effects This study also reported changes in BP at 12 and 52 weeks as a primary outcome |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomization not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomization not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | Double‐blinded study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Unclear risk | Investigator evaluated tentative adverse effects and made withdrawal decision. It is unclear whether blinding was broken prior to making final decision to withdraw |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Cardiovascular events | Low risk | All events were included |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | Reasons for discontinuation given. Similar rates of loss to follow‐up and nonadverse effect‐related discontinuation in both arms |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information on funding or industrial support |

DETAIL 2004.

| Methods | "Prospective, randomized, double‐blind, double‐dummy, parallel‐group" design Prespecified duration of follow‐up: 5 years % lost to follow‐up in participants with hypertension: not reported, but intention‐to‐treat analysis used % discontinuation due to other reasons in our subgroup of interest (see notes) |

|

| Participants | Number of participants with hypertension: 202 (102 for enalapril, 100 for telmisartan) Mean baseline BP: 158/87 mmHg Mean age: 61.0 years % male: 72.3% % white race: 98.5% Other risk factors: type 2 diabetes mellitus (100%) Location: "39 centres in Northern Europe" |

|

| Interventions | 1‐month screening period with continuation of old medication, with mandatory inclusion of an ACE inhibitor Study medications were titrated as follows if SBP > 160 mmHg or DBP > 100 mHg ACE inhibitor arm titration steps: Step 1 (at 0 weeks): enalapril 10 mg + telmisartan placebo daily Step 2 (at 4 weeks): enalapril 20 mg enalapril + telmisartan placebo daily Step 3 (at 2 months): dose reduction of study medication "at the discretion of the local investigator", or addition of non‐ACE inhibitor/ARB BP‐lowering therapy if SBP > 160 mmHg or DBP > 100 mmHg ARB arm titration steps: Step 1 (at 0 weeks): telmisartan 40 mg + enalapril placebo daily Step 2 (at 4 weeks): telmisartan 80 mg + enalapril placebo daily Step 3 (at 2 months): dose reduction of study medication "at the discretion of the local investigator", or addition of non‐ACE inhibitor/ARB BP‐lowering therapy if SBP > 160 mmHg or DBP > 100 mmHg "Target blood pressure was initially less than 160/90mmHg, but lower targets…allowed as local or national guidelines changed during the study" |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality: death from all causes Cardiovascular events: MI, cardiac failure, cerebrovascular accident WDAE: did not specify specific adverse effects |

|

| Notes | As this study included people without hypertension, unpublished subgroup data for the people with hypertension were obtained from the authors for total and cardiovascular mortality. Subgroup data pertaining to nonfatal cardiovascular events were not obtained in an extractable form Participants were followed for 28 days after discontinuation for safety; 2 MIs in the enalapril arm (included in our analysis) occurred during this 28‐day period Supported by Boehringer Ingelheim |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomization not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomization not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | "Double‐blind, double‐dummy" trial |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Unclear risk | Unclear whether blinding was lifted before or after making decision to discontinue |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Cardiovascular events | Low risk | All events were included |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | The authors provided subgroup data for the subgroup with this review's definition of hypertension. Although the rate of loss to follow‐up in this subgroup was not available, intention‐to‐treat analysis was used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Rates of nonfatal cardiovascular events was not in an extractable form from the subgroup data for hypertension provided by the authors |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | "Data handling and trial management were supported by Boehringer Ingelheim," but the statistical analyses were predetermined by "an independent scientific steering committee." Boehringer Ingelheim had provided research grants to several of the main authors |

Fogari 2008.

| Methods | "Double‐blind, randomized, parallel‐group study" Duration of follow‐up: 1 year % lost to follow‐up: 3% with ACE inhibitor, 2% with ARB % discontinuation due to not achieving adequate BP: 18% with ACE inhibitor, 16% with ARB |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 246 (124 for ramipril, 122 for valsartan) Mean baseline BP: 152/95 mmHg (sitting) Mean age: 65 years % male: 46% % white race: not reported Other comorbidities/risk factors: atrial fibrillation (100%), smoking (12.6%) BP requirement for entry: SBP 140‐160 mmHg, DBP 90‐100 mmHg, or both Location: Italy |

|

| Interventions | 2‐week placebo washout Participants were assessed every 4 weeks for BP response. Study medications were uptitrated as below if BP was > 140/90 mmHg. If response was not achieved at 8 weeks, the participant was discontinued from the trial ACE inhibitor arm titration steps: Step 1: ramipril 5 mg daily Step 2: ramipril 7.5 mg daily Step 3: ramipril 10 mg daily ARB arm titration steps: Step 1: valsartan 160 mg daily Step 2: valsartan 240 mg daily Step 3: valsartan 320 mg daily |

|

| Outcomes | WDAE: details given (atrial flutter, cough, hypotension) Other main outcomes reported: atrial fibrillation recurrence, P‐wave duration, serum procollagen type I carboxyterminal peptide levels |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomization not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomization not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | Double‐blinded study. "Study medications were provided in capsules of identical appearance...stored in coded bottles" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Unclear risk | Unclear whether blinding was lifted before or after making decision to discontinue |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Cardiovascular events | Unclear risk | Outcome not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | All particpants were accounted for in report |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information on funding or industrial support. "The authors report no conflict of interest" |

Fogari 2011.

| Methods | "Prospective, randomized, double‐blind, parallel‐arm" design Prespecified duration of follow‐up: 1 year % lost to follow‐up: not reported, but intention‐to‐treat analysis used Total % discontinuation for any reason: 4.2% |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 262 (130 for ramipril, 132 for telmisartan) Mean baseline BP: 154/94 mmHg (sitting) Mean age: 66.0 years % male: 45.4% % white race: not reported Other risk factors: atrial fibrillation (100%), metabolic syndrome (100%), smoking (17%) BP criteria for entry: SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and < 160 mmHg or DBP ≥ 90 and < 100 mm Hg, or both Exclusion criteria: history of MI or stroke; diabetes mellitus; congestive heart failure; unstable angina; valvular disease; left atrium size > 46 mm; hypercholesterolemia; cardioversion within last 8 weeks; cardiac surgery within last 6 months; pregnancy; previous treatment with ACE inhibitors, ARBs, calcium channel blockers, or antiarrhythmics; known sensitivity/contraindications to study medications |

|

| Interventions | 2‐week washout period: discontinue BP‐lowering agents, take placebo Follow‐up occurred every month. Study medications were uptitrated as below if sitting BP > 140/90 mmHg. "No concomitant medication was allowed throughout the study." Study medications were given in "capsules of identical appearance (same colour, size, and taste)" ACE inhibitor arm titration steps: Step 1: ramipril 5 mg daily Step 2: ramipril 7.5 mg daily Step 3: ramipril 10 mg daily Step 4: withdrawn from trial ARB arm titration steps: Step 1: telmisartan 80 mg daily Step 2: telmisartan 120 mg daily Step 3: telmisartan 160 mg daily Step 4: withdrawn from trial |

|

| Outcomes | WDAE: details given (atrial flutter, glottis edema, intolerable dry cough, hypotension, headache, nausea) Other main outcomes reported: atrial fibrillation relapses, time to first recurrence and severity of atrial fibrillation, laboratory markers |

|

| Notes | Study also included an amlodipine arm with 129 participants | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A "computer generated randomization list" was used |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A "computer generated randomization list" was used |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | Double‐blinded trial. "To maintain blindness, the study drugs were given in capsules of identical appearance (same colour, size, and taste) stored in coded bottles" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Unclear risk | Unclear whether blinding was lifted before or after making decision to discontinue |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Cardiovascular events | Unclear risk | Outcome not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | Rate of loss to follow‐up not specifically reported, but intention‐to‐treat analysis was used. Number of discontinuations not due to adverse effects were similar in both ramipril (24 participants) and telmisartan (21 participants) arms |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | "The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article" "The author(s) received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article" |

Fogari 2012.

| Methods | Prospective, randomized, double‐blinded, parallel‐arm design Prespecified duration of follow‐up: 1 year % lost to follow‐up: 1.9% with ACE inhibitor, 2% with ARB % discontinuation due to not achieving adequate BP: 4.9% with ACE inhibitor, 9.9% with ARB |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 205 (103 for ramipril, 102 for valsartan) Mean baseline BP: 143/87 mmHg (sitting, in A.M.) Mean age: 62 years % male: 53% % white race: not reported Other comorbidities/risk factors: Type 2 diabetes with HbA1c < 7% (100%), smoking (21%) BP criteria for entry: SBP 150‐180 mmHg, DBP 95‐110 mmHg, or both. However, only participants who did not respond to amlodipine/HCTZ therapy (BP > 130/80 mmHg after treatment) were ultimately randomized Exclusion criteria: heart failure; nonhypertension‐related hypertrophic cardiomyopathies; secondary hypertension; history of: angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack, MI, coronary artery bypass graphing, and symptomatic arrhythmia |

|

| Interventions | 2‐week placebo washout 4‐week amlodipine 10 mg + HCTZ 12.5 mg pretreatment Nonresponders to amlodipine/HCTZ pretreatment (defined as BP > 130/80 mmHg) were randomized to ramipril/amlodipine/HCTZ or valsartan/amlodipine/HCTZ Participants were followed every 4 weeks and study medications were uptitrated as below if sitting BP > 130/80 mmHg ACE inhibitor arm titration steps: Step 1: ramipril 5 mg daily Step 2: ramipril 10 mg daily ARB arm titration steps: Step 1: valsartan 160 mg daily Step 2: valsartan 320 mg daily "No concomitant medication was allowed throughout the study" "All medications were identical in appearance (same size, taste and color)" |

|

| Outcomes | WDAE: details given (cough, edema, rash, hypotension, dizziness) Other main outcomes reported: ejection fraction and other echocardiogram markers, laboratory markers |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomization not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomization not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | Double‐blinded trial. "All medications were identical in appearance (same size, taste and color)" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Unclear risk | Unclear whether blinding was lifted before or after making decision to discontinue |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Cardiovascular events | Unclear risk | Outcome not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Unclear risk | Participants were withdrawn during the randomized phase due to "uncontrolled BP" (5 in ramipril arm, 4 in valsartan arm), but there was no mention of the definition of "uncontrolled BP" for this purpose, or of any prespecified protocols for such a withdrawal |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | "The authors state no conflict of interest and have received no payment in preparation of this manuscript" |

Lacourciere 2000.

| Methods | Prospective, randomized, double‐blinded design Duration of follow‐up: 1 year % discontinuation not due to adverse effects: 8.7% Total % discontinuation: 10.7% |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 103 (51 for enalapril, 52 for losartan) Mean baseline BP: 160/96 mmHg (sitting) Mean age: 58.5 years % male: 80.6% % white race: 96.1% % oriental: 2.9% % black: 1.0% Other risk factors: type 2 diabetes mellitus (100%), early nephropathy (100%) BP requirement for entry: sitting DBP 90‐115 mmHg after washout and single‐blind placebo run‐in Exclusion criteria: cerebrovascular accident or MI within last 12 months, unstable angina, history of heart failure, arrhythmias, current transient ischemic attack, renovascular disease, history of malignant hypertension (SBP > 210 mmHg), clinically significant arteriovenous conduction disturbances, use of agents for stable angina that may affect BP (except beta‐blockers and nitrates), treatment with oral corticosteroids, drug/alcohol abuse, pregnancy, breastfeeding, ineffective contraception, serum creatinine ≥ 200 mM, serum potassium ≥ 5.5 mM or ≤ 3.5 mM Location: Canada |

|

| Interventions | 7‐day washout period; 14 days for participants being treated with ACE inhibitors. Any background BP‐lowering agents were discontinued, with the exception of beta‐blockers and nitrates used for stable angina 2‐ to 4‐week single‐blind placebo run‐in Participants in either arm were started at step 1 and uptitrated as below if sitting DBP > 85 mmHg at each visit. "Early up‐titration" was allowed if DBP > 105 mmHg, but no further details were given regarding the protocol for doing so. Participants with sitting DBP > 100 mmHg by week 20 were discontinued from the study ACE inhibitor arm titration steps: Step 1 (week 0): enalapril 5 mg daily Step 2 (week 4): enalapril 10 mg daily Step 3 (week 8): enalapril 20 mg daily Step 4 (week 12): enalapril 20 mg + HCTZ 12.5 mg daily Step 5 (week 12 and after): enalapril 20 mgril + HCTZ 25 mg daily Step 6 (week 12 and after): add other BP‐lowering agent (other than ACE inhibitor, ARB, or calcium channel blocker) ARB arm titration steps: Step 1 (week 0): losartan 50 mg daily Step 2 (week 4): losartan 50 mg daily (no change from step 1) Step 3 (week 8): losartan 100 mg daily Step 4 (week 12): losartan 100 mg + HCTZ 12.5 mg daily Step 5 (week 12 and after): losartan 100 mg + HCTZ 25 mg daily Step 6 (week 12 and after): add other BP‐lowering agent (other than ACE inhibitor, ARB, or calcium channel blocker) |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality and cardiovascular events: none occurred in this study WDAE: specific adverse effects given (cough, urticaria, dyspnea) Other main outcomes reported: changes in BP, ambulatory BP, laboratory values |

|

| Notes | Funding: Grant from Merck Frosst Canada & Co. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomization not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomization not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | Double‐blinded trial |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Unclear risk | Unclear whether blinding was lifted before or after making decision to discontinue |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Cardiovascular events | Unclear risk | Outcome not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Withdrawal due to adverse effects | Low risk | Reasons given for all discontinuations. Rates of discontinuation similar in both the ACE inhibitor and ARB arms |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes and outcomes of interest to this review reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | "Supported by a grant from Merck Frosst Canada & Co." |

ONTARGET 2008.

| Methods | Double‐blind randomized controlled design Mean duration of follow‐up: 4.5 years % lost to follow‐up/discontinued: unavailable in our subgroup of interest, but in the main study "99.8% were followed until a primary event occurred or until the end of the study" |

|

| Participants | Total patients with SBP > 150 mmHg: 5329 (data for total cardiovascular events available only for this subgroup) Total patients with SBP > 140 mmHg or DBP > 90 mmHg: 9398 (provided by authors) Age: all patients must have been at least 55 years of age (mean age unavailable for hypertension subgroup) % male: unavailable for hypertension subgroup Other risk factors: all patients had 1 of: previous MI, stable or unstable angina, previous multivessel percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or multivessel coronary artery bypass graft, previous stroke, previous transient ischemic attacks, peripheral artery disease, diabetes mellitus with evidence of end‐organ damage (percentage breakdown of risk factors unavailable for hypertensive subgroup) Exclusion criteria: intolerance to ACE inhibitors or ARB, symptomatic congestive heart failure, valvular or outflow tract obstruction, constrictive pericarditis, complex congenital heart disease, idiopathic syncope, heart transplant recipient, planned cardiac surgery, uncontrolled hypertension on treatment (BP > 160/100 mmHg), stroke due to subarachnoid hemorrhage, significant renal artery disease, hepatic dysfunction, uncorrected volume or sodium depletion, primary hyperaldosteronism, hereditary fructose intolerance, "other major non‐cardiac illness expected to reduce life expectancy or interfere with study participation," and taking another experimental drug Location: international ("40 countries") |

|

| Interventions | Single‐blind run‐in period: ramipril 2.5 mg daily for 3 days, telmisartan 40 mg and ramipril 2.5 mg daily for 7 days, telmisartan 40 mg daily for 11‐18 days ACE inhibitor arm: Ramipril 5 mg daily for the first 2 weeks, and then ramipril 10 mg daily. telmisartan 80 mg placebo was also taken daily. No information on further titration or background therapy ARB arm Telmisartan 80 mg + ramipril 5 mg placebo daily for the first 2 weeks, and then telmisartan 80 mg + ramipril 10 mg placebo daily. No information on further titration or background therapy |

|