Abstract

Background

Children with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) frequently present with inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity, which are the cardinal symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The effectiveness of methylphenidate, a commonly used ADHD treatment, is therefore of interest in these children.

Objectives

To assess the effects of methylphenidate for symptoms of ADHD (inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity) and ASD (impairments in social interaction and communication, and repetitive, restricted or stereotypical behaviours) in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years with ASD.

Search methods

In November 2016, we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, 11 other databases and two trials registers. We also checked reference lists and contacted study authors and pharmaceutical companies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated the effect of methylphenidate versus placebo on the core symptoms of ASD or ADHD‐like symptoms, or both, in children aged 6 to 18 years who were diagnosed with ASD or pervasive developmental disorder. The primary outcome was clinical efficacy, defined as an improvement in ADHD‐like symptoms (inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity) and in the core symptoms of ASD (impaired social interaction, impaired communication, and stereotypical behaviours), and overall ASD. Secondary outcomes examined were: rate of adverse events; caregiver well‐being; need for institutionalisation, special schooling or therapy to achieve learning outcomes; and overall quality of life.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methodological procedures. We combined outcome measures that used different psychometric scales, where clinically appropriate. We used a coefficient of 0.6 to calculate standard deviations and adjust for the studies' cross‐over design. We considered a standardised mean difference (SMD) of 0.52 as the minimum clinically relevant inter‐treatment difference. We applied the GRADE rating for strength of evidence for each outcome.

Main results

The studies: we included four cross‐over studies, with a total of 113 children aged 5 to 13 years, most of whom (83%) were boys. We included two studies with five‐year‐old children since we were unable to obtain the disaggregated data for those aged six years and above, and all other participants were in our target age range. All participants resided in the USA. The duration of treatment in the cross‐over phase was one week for each dose of methylphenidate. Studies used a range of outcome scales, rated by parents, teachers or both; clinicians; or programme staff. We report parent‐rated outcomes separately.

Risk of bias: we considered three trials to be at high risk of bias due to selective reporting and all trials to be at unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and assessors, due to the potential for recognising the side effects of methylphenidate. We judged all trials to be at low or unclear risk of bias for other items.

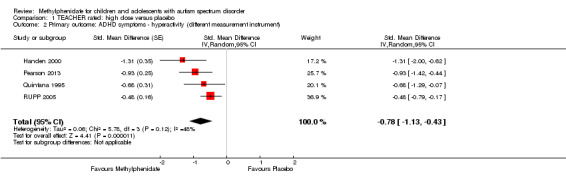

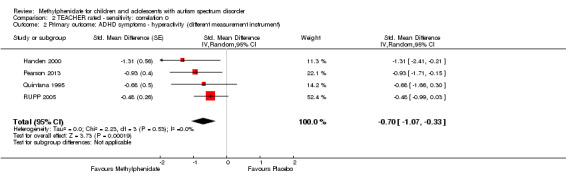

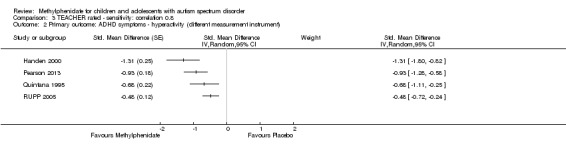

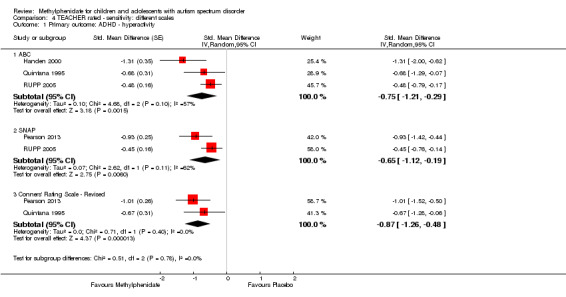

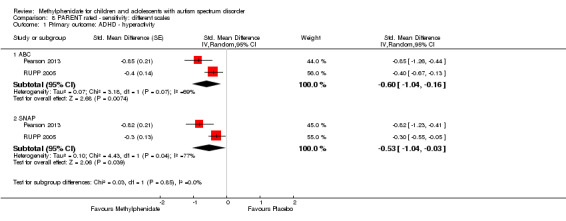

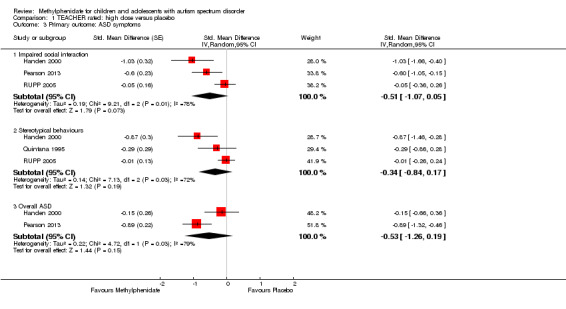

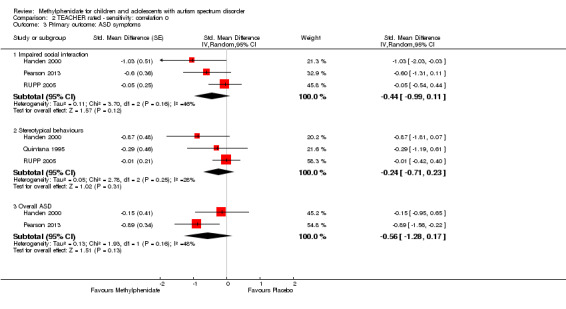

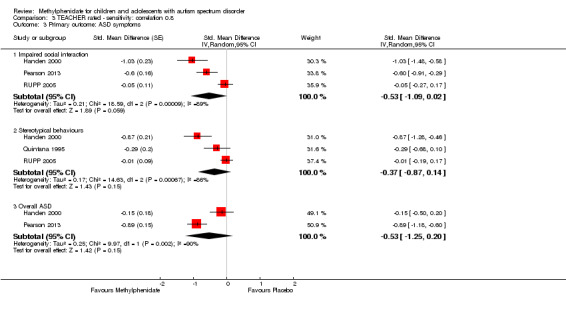

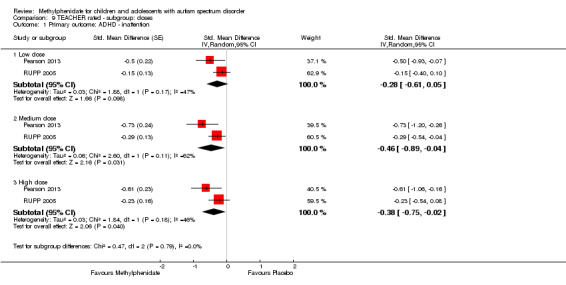

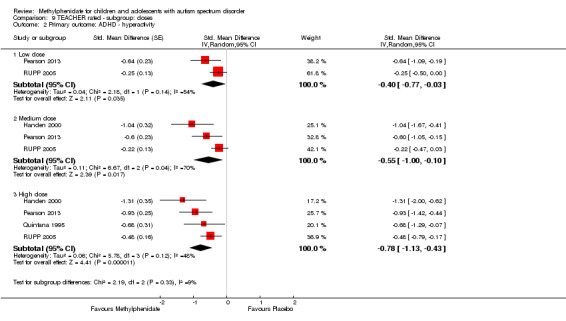

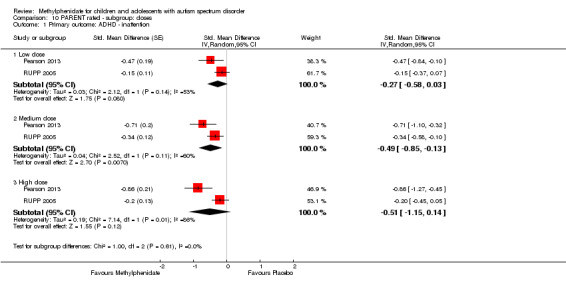

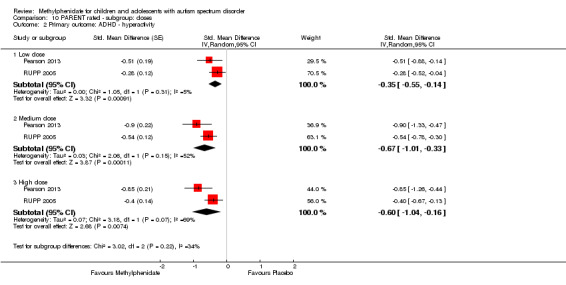

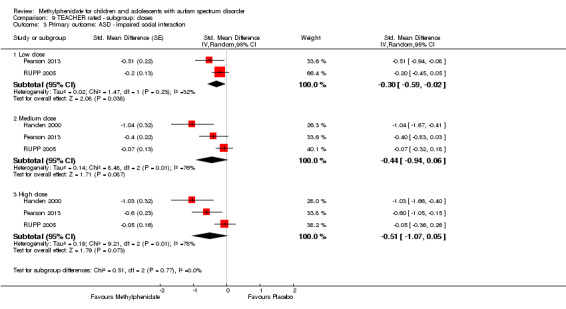

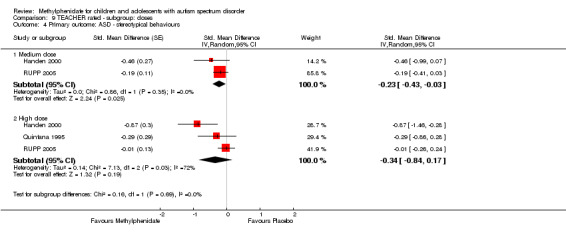

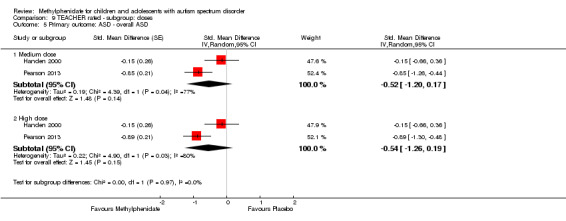

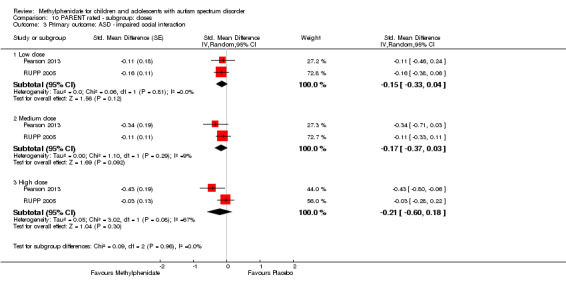

Primary outcomes: the meta‐analysis suggested that high‐dose methylphenidate (0.43 mg/kg/dose to 0.60 mg/kg/dose) had a significant and clinically relevant benefit on hyperactivity, as rated by teachers (SMD −0.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) −1.13 to −0.43; 4 studies, 73 participants; P < 0.001; low‐quality evidence) and parents (mean difference (MD) −6.61 points, 95% CI −12.19 to −1.03, rated on the hyperactivity subscale of the Aberrant Behviour Checklist, range 0 to 48; 2 studies, 71 participants; P = 0.02; low‐quality evidence). Meta‐analysis also showed a significant but not clinically relevant benefit on teacher‐rated inattention (MD −2.72 points, 95% CI −5.37 to −0.06, rated on the inattention subscale of the Swanson, Nolan and Pelham, Fourth Version questionnaire, range 0 to 27; 2 studies, 51 participants; P = 0.04; low‐quality evidence). There were inadequate data to conduct a meta‐analysis on the symptom of impulsivity. There was no evidence that methylphenidate worsens the core symptoms of ASD or benefits social interaction (SMD −0.51, 95% CI −1.07 to 0.05; 3 studies, 63 participants; P = 0.07; very low‐quality evidence), stereotypical behaviours (SMD −0.34, 95% CI −0.84 to 0.17; 3 studies, 69 participants; P = 0.19; low‐quality evidence), or overall ASD (SMD −0.53, 95% CI −1.26 to 0.19; 2 studies, 36 participants; P = 0.15; low‐quality evidence), as rated by teachers. There were inadequate data to conduct a meta‐analysis on the symptom of impaired communication.

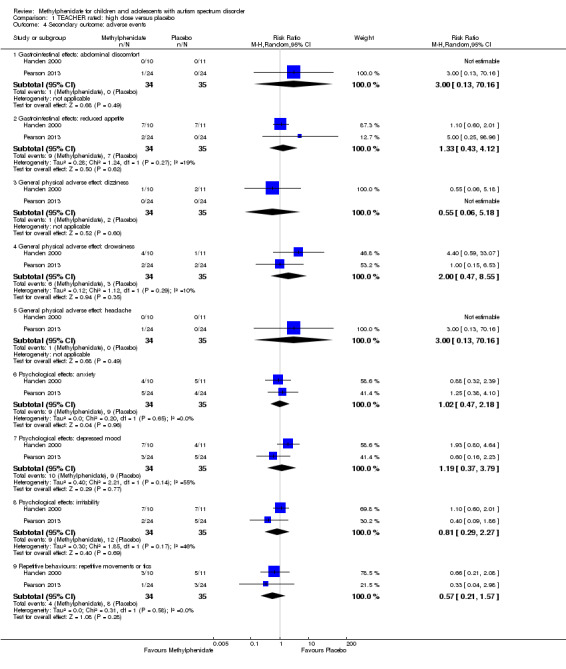

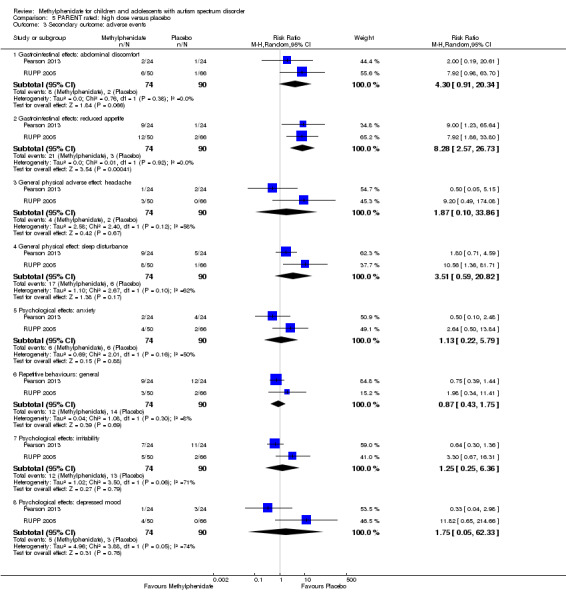

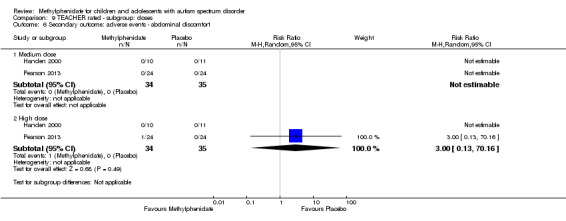

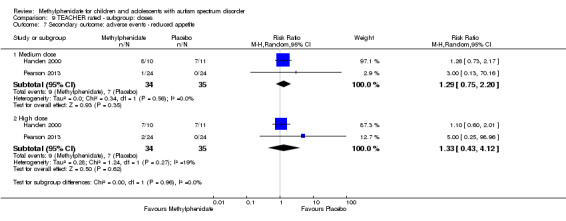

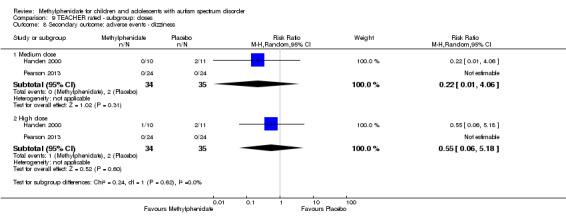

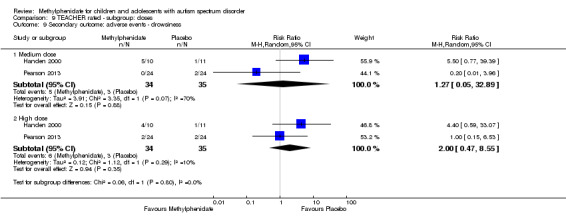

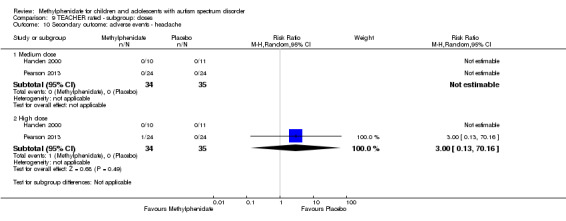

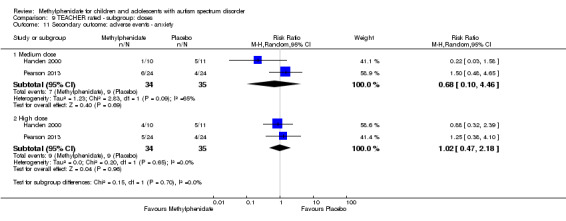

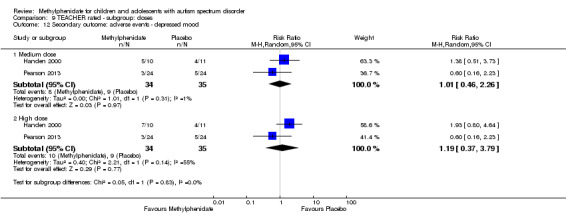

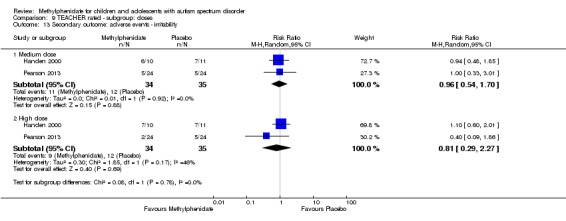

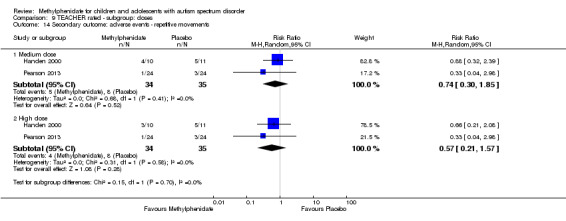

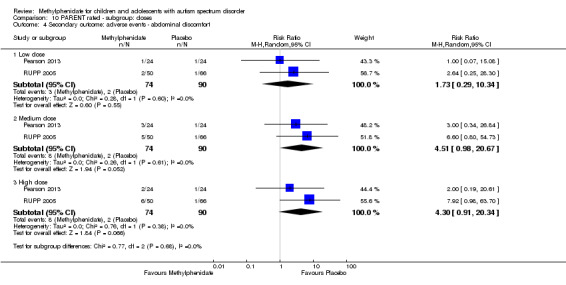

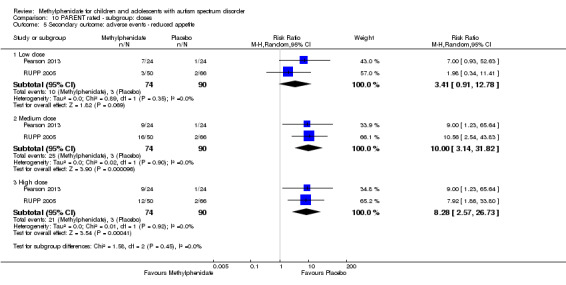

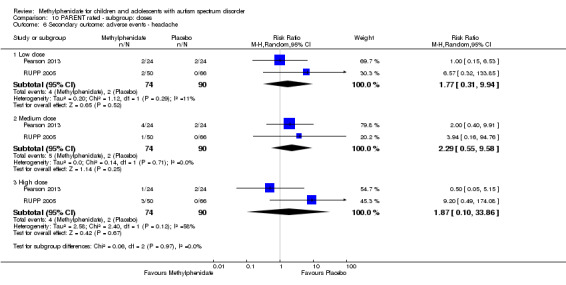

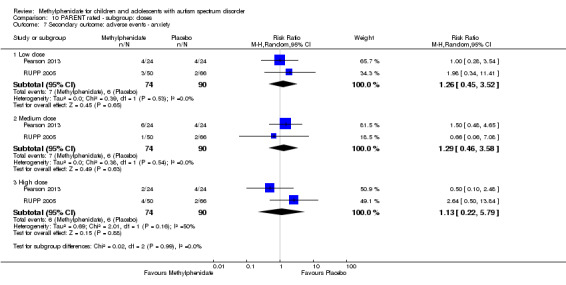

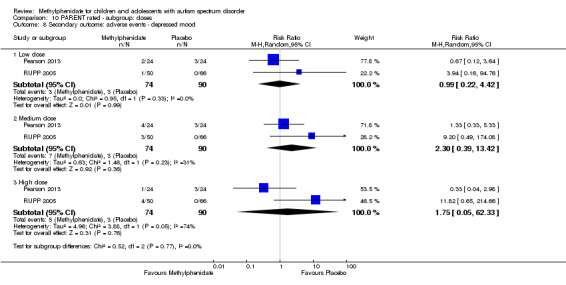

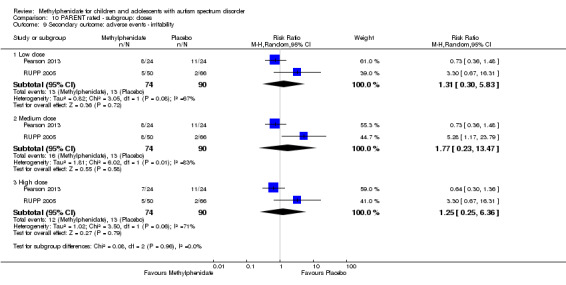

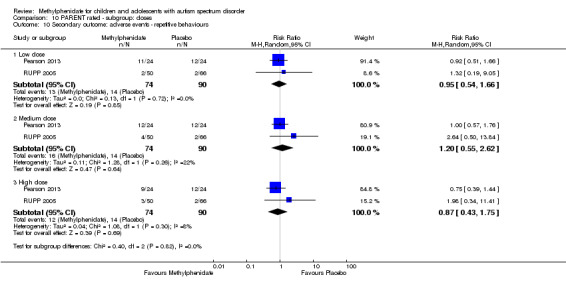

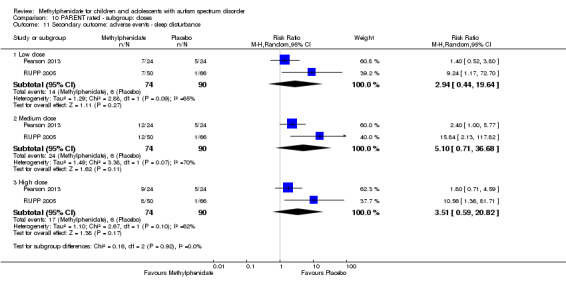

Secondary outcomes: no data were available for the secondary outcomes of caregiver well‐being; need for institutionalisation, special schooling options or therapy to achieve learning outcomes; or overall quality of life. No trials reported serious adverse events. The only adverse effect that was significantly more likely with treatment was reduced appetite as rated by parents (risk ratio 8.28, 95% CI 2.57 to 26.73; 2 studies, 74 participants; P < 0.001; very low‐quality evidence). Subgroup analysis by dose did not identify any significant differences in effect on our primary outcomes between low‐, medium‐ or high‐dose ranges.

Authors' conclusions

We found that short‐term use of methylphenidate might improve symptoms of hyperactivity and possibly inattention in children with ASD who are tolerant of the medication, although the low quality of evidence means that we cannot be certain of the true magnitude of any effect. There was no evidence that methylphenidate has a negative impact on the core symptoms of ASD, or that it improves social interaction, stereotypical behaviours, or overall ASD. The evidence for adverse events is of very low quality because trials were short and excluded children intolerant of methylphenidate in the test‐dose phase. Future RCTs should consider extending the duration of treatment and follow‐up. The minimum clinically important difference also needs to be confirmed in children with ASD using outcome scales validated for this population.

Plain language summary

Effect of methylphenidate for inattentiveness, impulsivity and/or hyperactivity in children aged 6 to 18 years with autistic spectrum disorder

Children with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) often have trouble paying attention, acting impulsively and sitting still. Methylphenidate, a stimulant drug, is often prescribed to treat children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) who also have these problems, so it is important to know how well it works for children with ASD.

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out if methylphenidate is helpful for children with ASD. We collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question and found four studies.

Key messages

Methylphenidate may improve hyperactivity in children with ASD in the short term, although there was no evidence that methylphenidate improves or worsens ASD symptoms. Some children cannot tolerate the medication's side effects.

What was studied in the review?

We looked for studies that compared children receiving methylphenidate at any dose to placebo (a dummy pill which looks like methylphenidate but has no known effects). We were most interested in investigating the effect of the drug on symptoms of ADHD (inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity) and ASD (impairments in social interaction and communication, and repetitive, restricted or stereotypical behaviours), but we also looked for information on side effects, caregiver well‐being, the need for special schooling or institutionalisation, and children's overall quality of life.

What are the main results of the review?

We found four studies involving 113 children aged 5 to 13 years and comparing methylphenidate versus placebo. We included two studies with five‐year‐old children because we were unable to separate the data for those aged six years and above, and all other participants were in our target age range. In all of these studies, children took different doses of methylphenidate (low, medium or high) for one week and placebo for another week, and their caregivers (including parents, teachers and clinicians) rated their symptoms at the end of each week. Children who could not tolerate methylphenidate in the test‐dose week (where a dose of medication is given to test the safety and tolerability of the drug) did not participate in the study. All of the studies took place in the USA.

We found that methylphenidate may improve hyperactivity, as assessed by parents and teachers, in the short term. Teachers also tended to report an improvement in children taking methylphenidate in relation to inattention, social interaction, repetitive behaviours, and overall ASD symptoms. However, the studies only lasted for about four weeks, so we do not know if there are any benefits or risks in the long term. There was not enough evidence to say whether methylphenidate has any effect on impulsivity or communication. Teachers and clinicians tended to report more improvement than parents.

We cannot be confident about these findings, mainly because parents and teachers may have recognised which treatment the children were on. The size of the improvement was not very large, except in the case of hyperactivity, where it was probably large enough to really notice the difference. Most of the improvements, except for the improvements in hyperactivity and inattention, could have happened by chance even if methylphenidate is not really effective. We cannot say anything about the likelihood of any harmful effects from methylphenidate, partly because children who had harmful effects prior to the studies, or in the test‐dose phase, are less likely to have participated in the studies.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The evidence is current to November 2016.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. High‐dose methylphenidate versus placebo for symptoms of ADHD and ASD as rated by teachers.

| High‐dose methylphenidate versus placebo for symptoms of ADHD and ASD as rated by teachers | ||||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6 to 18 years with ASD Settings: paediatric or psychiatric outpatient or inpatient units, special education units or classes Rater: teachers, clinicians or programme staff Intervention: high‐dose methylphenidate Comparison: placebo Follow‐up: 1 week Measure of effect: if necessary, we transformed results to ensure that lower scores represented fewer symptoms for all comparisons. We standardised results using standardised mean differences (SMD). As such, results are expressed in standardised units, and a negative SMD represents an improvement in symptoms. As a rough guide, an SMD of 0.20 to 0.49 represents a small effect, 0.50 to 0.79 a moderate effect, and ≥ 0.80 a large clinical effect. We used an SMD of 0.52 as the minimum clinically relevant intertreatment difference. | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with high‐dose methylphenidate | |||||

| Primary outcome: ADHD‐like symptoms | ||||||

| Inattention Measured using SNAP‐IV inattention subscale (range 0 to 27) |

— | The mean inattention score in the intervention group was 2.72 units lower (5.37 lower to 0.06 lower) | — | 51 teachers (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — |

| Hyperactivity | — | The mean hyperactivity score in the intervention group was 0.78 standard units lower (1.13 lower to 0.43 lower) | — | 73 teachers (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — |

| Impulsivity | See comment | — | 36 teachers (1 RCT) |

— | Insufficient data to pool results | |

| Primary outcome: core symptoms of ASD | ||||||

| Impaired social interaction | — | The mean impaired social interaction score in the intervention group was 0.51 standard units lower (1.07 lower to 0.05 higher) | — | 63 teachers (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | — |

| Impaired communication | See comment | — | 24 teachers (1 RCT) |

— | Insufficient data to pool results | |

| Stereotypical behaviours | — | The mean stereotypical behaviours score in the intervention group was 0.34 standard units lower (0.84 lower to 0.17 higher) | — | 69 teachers (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — |

| Overall ASD | — | The mean overall ASD score in the intervention group was 0.53 standard units lower (1.26 lower to 0.19 higher) | — | 36 teachers (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — |

| Secondary outcome: rate of adverse effects | ||||||

| Total number of adverse events | See comment | — | 79 teachers (1 RCT) |

— | Insufficient data to pool resultsd | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD: autism spectrum disorders; CI: confidence interval; SNAP‐IV: Swanson, Nolan and Pelham scale, Fourth Revision;RCT: randomised controlled trial | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one point for limitations in design and implementation. bDowngraded one point for imprecision because data came from small studies. cDowngraded one point for indirectness of evidence. dData on individual adverse events are presented in the text.

Summary of findings 2. High‐dose methylphenidate versus placebo for symptoms of ADHD and ASD as rated by parents.

| High‐dose methylphenidate versus placebo for symptoms of ADHD and ASD as rated by parents | ||||||

| Patient or population: Children aged 6 to 18 years with ASD Settings: paediatric or psychiatric outpatient or inpatient units, special education units or classes Rater: parents Intervention: high‐dose methylphenidate Comparison: placebo Follow‐up: 1 week Measure of effect: if necessary, we transformed results to ensure that lower scores represented fewer symptoms for all comparisons. We standardised results using standardised mean differences (SMD). As such, results are expressed in standardised units, and a negative SMD represents an improvement in symptoms. As a rough guide, an SMD of 0.20 to 0.49 represents a small effect, 0.50 to 0.79 a moderate effect, and ≥ 0.80 a large clinical effect. We used an SMD of 0.52 as the minimum clinically relevant intertreatment difference. | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with high‐dose methylphenidate | |||||

| Primary outcome: ADHD‐like symptoms | ||||||

| Inattention Measured using SNAP‐IV inattention subscale (range 0 to 27) |

— | The mean inattention score in the intervention group was 3.16 units lower (6.89 lower to 0.57 higher) | — | 71 parents (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — |

| Impulsivity | See comment | — | 48 parents (1 RCT) |

— | Insufficient data to pool results | |

| Hyperactivity Measured using ABC hyperactivity subscale (range 0 to 48) |

— | The hyperactivity score in the intervention group was 6.61 units lower (12.19 lower to 1.03 lower) | — | 71 parents (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — |

| Primary outcome: core symptoms of ASD | ||||||

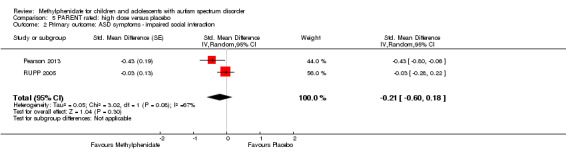

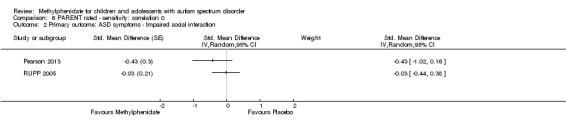

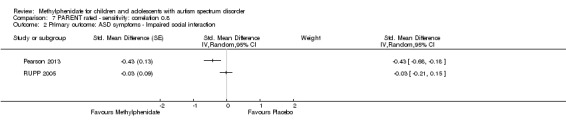

| Impaired social interaction | — | The impaired social interaction score in the intervention group was 0.21 standard units lower (0.60 lower to 0.18 higher) | — | 71 parents (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | — |

| Impaired communication | See comment | — | 48 parents (1 RCT) |

— | Insufficient data to pool results | |

| Stereotypical behaviours | See comment | — | 48 parents (1 RCT) |

— | Insufficient data to pool results | |

| Overall ASD | See comment | — | 48 parents (1 RCT) |

— | Insufficient data to pool results | |

| Secondary outcome: rate of adverse events | ||||||

| Total number of adverse events | See comment | — | 108 parents (1 RCT) |

— | Insufficient data to pool resultsd | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ABC: Aberrant Behavior Checklist; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD: autism spectrum disorders; CI: confidence interval; SNAP‐IV: Swanson, Nolan and Pelham scale, Fourth Revision;RCT: randomised controlled trial | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

a Downgraded one point for limitations in design and implementation. b Downgraded one point for imprecision because data came from small studies. c Downgraded one point for indirectness of evidence. d Data on individual adverse events are presented in the text.

Background

Description of the condition

Autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) is a group of developmental disorders described in theDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), fifth edition (DSM‐5), which includes autistic disorder, Asperger's disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. ASD encompasses disorders previously referred to as early infantile autism, childhood autism, Kanner's autism, high‐functioning autism and atypical autism. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD‐10) classifies childhood autism as a disorder of psychological development, defined by the presence of abnormal or impaired development that is manifest before three years of age, and the characteristic type of abnormal functioning in all three areas of psychopathology: reciprocal social interaction; communication; and restricted, stereotyped, repetitive behaviour (WHO 2007).

The fourth edition, text revision of the DSM described three characteristic manifestations of ASD (DSM‐IV‐TR): impaired social interaction; impairment of communication; and restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour (Filipek 1999; Wing 1997). The DSM‐5 uses five diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of ASD: persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts; restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities; symptoms present in the early developmental period; symptoms causing clinically significant impairment; and disturbances that are not better explained by intellectual disability or global developmental delay. Studies published prior to 2014 used diagnostic criteria from the fourth edition of the DSM (DSM‐IV or DSM‐IV‐TR), as the DSM‐5 was only published in May 2013.

A systematic review of prevalence studies by Williams 2006 estimated an overall prevalence of 7.1 per 10,000 children (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.6 to 30.6) for typical autism and a prevalence of 20.0 per 10,000 children (95% CI 4.9 to 82.1) for ASD (based on the DSM‐IV classification). AABASD 2007 estimated the prevalence of ASD in Australia to be 62.5 per 10,000 for children aged 6 to 12 years. Reported frequencies for ASD across the USA and other countries have approached 1% of the population, with similar estimates in child and adult samples (Brugha 2011). Since DSM‐5 criteria superseded earlier versions of the DSM, reports have shown reduced numbers of children diagnosed with ASD and an increase in the percentage with intellectual impairment (Sturmey 2014).

Early observations of autism by Kanner 1943 led to recognition of the autism spectrum as a heterogenous group of disorders with varying clinical presentations and severities (AAP 2001; NICHD 2014). The onset is typically before three years of age (see DSM‐IV), although diagnosis is often delayed for an additional two or three years (Filipek 2000). Children commonly present with speech delay, poor eye contact, social impairment, unusual or repetitive play, need for routine, difficulty coping with change and obsessions. Approximately 50% or more have intellectual impairment (Sturmey 2014), but others have an intelligence quotient (IQ) in the normal range. Children may also present with abnormal movements, heightened levels of anxiety, phobias, sleeping and eating disturbances, temper tantrums and self‐injurious or aggressive behaviour. Diagnosis of ASD includes history from parents and teachers, clinical observation, psychological and often speech language assessment. Numerous behaviour rating scales have been developed both to aid the assessment of ASD and to monitor response to therapy (AAP 2001; Bertoglio 2009; Filipek 1999; Lord 2000; Santosh 2006; Scahill 2005; Scahill 2006; Wagner 2007; WHO 2007).

Abnormalities of attention (including being overly focused or easily distracted), hyperactivity and impulsivity are common in individuals with ASD (Burack 1997; Lecavalier 2006; Nicolson 2000; Siegel 2012). Studies of children with ASD indicate that 24% to 83% of these children would also meet the criteria for a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on their symptoms of inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity – the cardinal symptoms for ADHD (Frazier 2001; Hyman 2013; Simonoff 2013), although comorbid diagnoses of both ADHD and ASD have only been permitted since the DSM‐5 revision (Hyman 2013). ADHD is a prevalent childhood behavioural disorder, more common in boys, which may persist into adulthood. The prevalence of ADHD in the general population of school‐age children is approximately 3% to 5%, although some reports show even higher incidence (Polanczyk 2007). Children with ADHD appear to have impaired functioning of the prefrontal cortex, a high‐order cortical region that is believed to use representational knowledge of rules and goals, and working memory, to accomplish tasks (Busardò 2016). This region has an important role in inhibiting inappropriate behaviour and sustaining attention. In children with ASD, inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity increase the risk of poor school performance and academic underachievement, causing further social impairment due to inappropriate and impulsive behaviours, which may also place the child at risk of harm.

The mainstays of treatment for children with ASD are behavioural interventions and pharmacological treatments. The SIGN 2007 guidelines suggest considering behavioural interventions to address a wide range of specific behaviours. There is also some evidence for tailored social communication interventions (such as the use of visual augmentation). Recent Cochrane Reviews of interventions for children with ASD do not support the use of acupuncture (Cheuk 2011), theory of mind skills training (Fletcher‐Watson 2014), omega‐3 fatty acids (James 2011), chelation (James 2015), auditory integration therapy (Sinha 2011), or intravenous secretin (Williams 2012), although there is some evidence that various social competencies may improve with music therapy (Geretsegger 2014), social skills groups (Reichow 2012a), and early intensive behavioural interventions (Reichow 2012b).

Pharmacological treatments have also been widely used in children with ASD to treat both core and co‐morbid symptoms. There is no evidence supporting the use of antidepressants or anticonvulsants to reduce core features of ASD in children (Hurwitz 2012; Williams 2013). There may be a limited role for risperidone, perhaps only in the short term and targeted at specific behaviours (Jesner 2007). Aripiprazole may improve irritability, hyperactivity and repetitive movements in children with ASD in the short term (Ching 2012). Psychostimulants, in particular methylphenidate, have also been prescribed to treat symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention and impulsivity in children with ASD, despite concerns that these medications may worsen ASD symptoms or cause more adverse events than in typically developing children (see Why it is important to do this review).

Description of the intervention

Methylphenidate has been used clinically for over 50 years to treat the symptoms of ADHD in children and is, by far, the most common psychostimulant medication used for this purpose. Over 20 years ago, Aman 1995 identified it as a candidate for treating inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity in children with ASD. A recent meta‐analysis of the effectiveness of methylphenidate in children with ADHD concluded that methylphenidate may result in improved ADHD symptoms with an estimated effect size of −0.77 standardised mean difference (SMD) (Storebø 2015).

Treatment with immediate‐release formulations of methylphenidate is usually initiated at 5 mg once or twice daily, up to a maximum of 60 mg per day. Treatment with modified‐release formulations of methylphenidate is usually initiated at a dose of 18 mg once daily (in the morning), and increased, if necessary, up to a maximum of 54 mg once daily (NICE 2013). Methylphenidate is also available in some countries in an extended‐release form as a transdermal patch (Mayo Clinic 2014). Short‐release formulations of methylphenidate are absorbed rapidly within 30 minutes, and their effects last up to six hours. Long‐acting or modified‐release forms usually contain both immediate‐ and delayed‐release formulations and are taken once daily (in the morning). They are available in 8‐ and 12‐hour preparations. The advantages of these controlled‐release products include the possible decrease in likelihood and severity of rebound symptoms (Szymansk 2001) and an increase in compliance in children due to reduced dosing frequency and fewer tablets. With short‐acting formulations, the maximum recommended dose is 1.5 mg/kg/day or 60 mg in two or three divided doses (TGL 2012). This can be given as a once‐daily dose in the combination formulations.

The optimal dose of methylphenidate is based on observations of clinical response by the individual, as individual responses are variable, and the optimum dose is not predictable. The dose is initially titrated by increasing the daily dose every week until the effects are observable or until adverse events warrant dose reduction or cessation. In children with ADHD, the ability to attend and focus, particularly in busy environments such as the classroom, indicates clinical effect. Most side effects of methylphenidate are dose dependent (Rossi 2010). Common side effects include headache, loss of appetite, abdominal discomfort, nausea, anxiety and insomnia (Rossi 2010). These effects could lead to intolerance of the drug. Methylphenidate may also increase blood pressure and heart rate, and consultation with a cardiologist is recommended before starting the drug in children with cardiac abnormalities. It also infrequently causes other serious conditions, such as growth restriction, psychosis, liver dysfunction and neuroleptic malignant syndrome, for which monitoring is needed (Medsafe 2010).

How the intervention might work

Although its mechanism of action is uncertain, a number of animal and human studies have investigated the effects of methylphenidate on the way various tasks are performed, and brain imaging and brain chemistry studies have attempted to elucidate how it might work. Methylphenidate is believed to improve symptoms of ADHD by increasing the action of catecholamines, which are a class of neurotransmitters (chemicals that transmit messages in the brain) that include dopamine and noradrenaline (Wilens 2008). Methylphenidate acts in certain areas of the brain, particularly in the prefrontal cortex and striatum. The potential mechanisms by which methylphenidate enhances the action of dopamine include blocking processes in the nerve endings in the brain that remove dopamine from areas where it plays an active role, and extending its duration of action. Methylphenidate is also believed to have a number of complex actions on various dopamine receptors (particularly D2 dopamine autoreceptors and D1 dopamine receptors) in the nervous tissue of the brain. Methylphenidate increases the action of noradrenaline and may have an effect on other neurotransmitters, such as histamine, acetylcholine and serotonin, which, in turn, modify the action of catecholamines (Wilens 2008). The mechanisms by which methylphenidate might work in children with ASD who have inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity have not yet been established.

Why it is important to do this review

Methylphenidate is commonly believed to be effective for children with ADHD, and a 2015 Cochrane Review of 185 studies of methylphenidate in children with ADHD found that methylphenidate may improve teacher‐rated ADHD symptoms and general behaviour as well as parent‐rated quality of life (Storebø 2015). Up to one third of adolescents with ASD who also meet criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD are currently treated with psychostimulants, most commonly methylphenidate (Frazier 2011). However, a number of studies in the 1970s and 1980s reported that stimulant medication, particularly dextroamphetamine, resulted in increased stereotypical movements in children with ASD (Birmaher 1988; Campbell 1975; Di Martino 2004). Concerns about stereotypy were reinforced by animal research demonstrating stimulant‐induced stereotypy in several animal species (Aman 1982). These concerns about methylphenidate worsening these core symptoms of ASD resulted in methylphenidate being considered contraindicated in children with ASD (Aman 1982; Birmaher 1988). Additional adverse events that may impact negatively on social interaction, including irritability, aggression, self‐mutilating behaviour, emotional lability and dysphoria have also been frequently reported in children with ASD who are treated with psychostimulants (Cortese 2012; Di Martino 2004; Ghuman 2009). However, methylphenidate has also been found to increase positive social interactions and social behaviour and to reduce social anxiety (Patin 2015). Moreover, studies have suggested that methylphenidate improves emotion processing (Conzelmann 2011; Schlochtermeier 2011), also helping children and adolescents with ADHD to recognise faces, facial emotions or both (Demirci 2016;Williams 2008), which may lead to improved social interaction. In addition, methylphenidate has been reported to reduce social interaction deficits in a mouse model of autistic spectrum disorders (Hara 2015), and methylphenidate appeared to improve some social behaviours and self‐regulation in one study of children with ASD (Jahromi 2009 in RUPP 2005). The effect of methylphenidate on impaired social interaction and communication in children with ASD is, however, unknown.

Psychostimulants may be effective in the treatment of ADHD‐like symptoms in children and adolescents with ASD (Cortese 2012). However, the effect of psychostimulants on the core symptoms of ASD (impaired communication, impaired social interaction, and repetitive, restricted or stereotypical behaviours) is uncertain, and their potential to worsen these symptoms remains a concern. It is important to identify whether similar effect sizes and similar risks of adverse events are present in children with ASD and children with ADHD but without ASD.

Objectives

To assess the effects of methylphenidate for symptoms of ADHD (inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity) and ASD (impairments in social interaction and communication, and repetitive, restricted or stereotypical behaviours) in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years with ASD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised (double‐blinded) controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years of age, diagnosed with ASD using criteria from DSM III, DSM‐IV or DSM‐IV‐TR, or diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorder according to the ICD‐10 (WHO 2007). We included children with concurrent diagnoses, such as anxiety disorder, intellectual impairment, learning delays and speech impairment, and congenital syndromes such as fragile X syndrome. We included children receiving co‐interventions, including psychotropic medications, dietary modifications and therapist‐based interventions such as speech, occupational and psychological therapy. We excluded children with other established causes of cognitive or behavioural problems such as acquired brain injury.

Types of interventions

We included trials if they used methylphenidate, irrespective of formulation or dose, and compared it to a placebo. We included trials giving methylphenidate to participants in addition to other psychotropic medications if these were provided to both arms. We included trials in which the treatment was administered in any setting, including the home, hospital or residential care.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Clinical efficacy

An improvement in ADHD‐like symptoms (inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity), as measured by psychometric instruments or observations of behaviour such as the fourth revision of the Swanson, Nolan and Pelham (SNAP‐IV) questionnaire, Conners' Global Index, and Conners' Parent Rating Scale ‐ Revised (CPRS‐R) (Kollins 2010)

An improvement in the core symptoms of ASD (impaired social interaction, impaired communication, and stereotypical behaviours), and overall ASD, as measured by psychometric instruments or observations of behaviour such as the Aberrant Behaviour Checklist (ABC) and the Child Autism Rating Scale (CARS) (Lord 2014)

Secondary outcomes

Rate of adverse events, for example, common adverse events of nausea and insomnia, and also more serious adverse events such as growth retardation and hypertension

Caregiver well‐being, including levels of parental stress, as assessed using scales such as the Parenting Stress Index (Abidin 1983)

Need for institutionalisation of children or adolescents, special schooling options or therapy to achieve learning outcomes, as measured either dichotomously (by need or no need) for institutionalisation of children or adolescents, special schooling options or therapy, or by duration of institutionalisation, special schooling options or therapy

Overall quality of life of the child or adolescent, as measured by a validated overall quality of life scale such as the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (Kollins 2010)

We listed our primary outcomes and rate of adverse events in a 'Summary of findings' table indicating levels of evidence for the findings. For more information see GRADE and 'Summary of findings', beneath Data synthesis.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases in May 2014 and again in November 2016. Appendix 1 reports search strategies for each source, and Appendix 2 provides further details (including exact search dates).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 4), in the Cochrane Library, which contains the Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialised Register (searched 21 November 2016).

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to November Week 2 2016).

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐indexed Citations Ovid (18 November 2016).

MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print Ovid (18 November 2016).

Embase Ovid (1974 to 18 November 2016).

CINAHLPlus EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1936 to 21 November 2016).

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to November Week 2 2016).

ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center; 1966 to 21 November 2016).

ERIC Proquest (Education Resources Information Center; 1966 to 16 May 2014).

Science Citation Index Web of Science (SCI; 1970 to 22 November 2016).

Social Sciences Citation Index Web of Science (SSCI; 1970 to 22 November 2016).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science Web of Science (CPCI‐S; 1990 to 22 November 2016).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Social Sciences & Humanities Web of Science (CPCI‐SS&H; 1990 to 22 November 2016).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; 2016, Issue 11) part of the Cochrane Library (searched 21 November 2016).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; 2015, Issue 2) part of the Cochrane Library (searched 21 November 2016).

AutismData (autism.org.uk/autismdata; searched 22 November 2016).

Proquest Dissertations & Theses (searched 2 December 2016).

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 22 November 2016).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO IRCTP; apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 22 November 2016).

Searching other resources

We contacted drug manufacturers by email, including Mallinckrodt, Novartis, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Shire and Medice, to obtain unpublished data. We also searched the references of relevant studies and (systematic) reviews to identify additional studies. Finally, we contacted the first author of included RCTs as well as specialists in developmental paediatrics to enquire about other relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (NS, MVD) independently read the title and abstracts of all records yielded by the search to determine suitability according to the criteria mentioned above (Criteria for considering studies for this review). They then obtained the full‐text reports of potentially relevant studies, or studies for which more information was needed, and assessed them for eligibility. The two review authors resolved any disagreements by discussion or asked a third review author (LD) to act as arbiter. We listed any excluded studies that initially appeared eligible for inclusion, along with the reasons for exclusion after full‐text review. We created a PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the selection process (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (NS, LD) extracted the following data using the piloted data extraction sheet shown in Appendix 3: type of study, participants, type of intervention (including dose and administration form), measurement scales used, and reported outcomes. A third review author (MVD) checked the extracted data in case of discrepancies that could not be resolved by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used a checklist to assess the risk of bias in each included study. Using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2017), two review authors (NS, MVD) independently assessed each study as being at low, high or unclear risk of bias on each of the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other sources of bias (see Appendix 4 for a detailed description of the criteria used). In the event of any disagreements, a third review author (LD) evaluated the study and a consensus was reached.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous outcome data

We use the standardised mean difference (SMD) for all continuous outcomes because this enabled us to combine and compare the results of the different scales used to measure outcomes that are conceptually the same. Where outcomes were assessed using the same scale in separate studies, we used the mean difference (MD). If necessary, we transformed results to ensure that a negative MD or SMD indicated an improvement in functioning for all comparisons.

The SMD expresses the size of the intervention effect in each included study relative to the variability observed in that study (Deeks 2017). This method is based on the assumption that the differences in standard deviations (SD) between trials reflect differences in scales and not real differences in variability between the populations included in the trials. The SMD is 'scale free', that is, since the dependent variable is standardised, the original units are replaced by standardised units. We used Hedges' g formulation to calculate the SMD. It is calculated by dividing the mean differences between groups by the SD. Hedges' g uses a weighting to account for the population sizes in the different studies (Egger 2001).

We included clinician or other trained observer ratings with teacher ratings in a single meta‐analysis where outcomes were measured using psychometric scales rated by a number of different observers (for example, teachers, trained observers and/or clinicians), providing participants were rated in classroom or similarly structured contexts. However, we considered that parent ratings should be considered as a separate outcome because children's behaviour at home may differ from that in more structured clinical or educational settings, and because teachers (or clinicians) have different relationships and contact hours with children compared to parents and may place greater emphasis on academic aspects (Zhang 2005).

We reported effect sizes separately for low, medium and high doses of methylphenidate. We did not combine the data from different doses within included studies because these are repeated measures on the same participants. We reported doses per kg of body weight, whether studies used individualised doses calculated per kg of participant body weight, or used proprietary doses of 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg and 20 mg of methylphenidate with adjustment for participant weight. We reported data from high‐dose methylphenidate as our primary outcome and performed a subgroup analysis of our results for medium‐ and low‐dose methylphenidate.

Low, medium and high doses are calculated based on the mg/kg/dose ranges. We did not use mg/kg/day because parents or clinicians (or both) may withhold afternoon doses because of adverse events. Low‐dose methylphenidate included doses between 0.11 mg/kg/dose and 0.21 mg/kg/dose, medium‐dose methylphenidate included doses between 0.22 mg/kg/dose and 0.36 mg/kg/dose, and high‐dose methylphenidate included doses between 0.43 mg/kg/dose and 0.6 mg/kg/dose.

Dichotomous outcome data

We reported dichotomous outcomes (such as presence or absence of adverse events and institutionalisation) as risk ratios (RRs), which we calculated as the proportion of patients in the treatment group who experienced the outcome (or event) divided by the proportion of participants in the control group who experience the outcome (or event). Where there were no events in either the treatment group or the control group, we reported these outcomes separately without pooling them. We calculated 95% CIs for all dichotomous outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

We analysed cross‐over trials, in which each individual participant was allocated to a sequence of interventions (for example, placebo, low dose, medium dose, high dose) in a semi‐randomised order, as follows. If there were no carry‐over or period effects, the appropriate analysis of continuous data for a cross‐over trials is a paired t‐test. However, not all studies clearly reported paired analyses. Therefore, for each study and each comparison (e.g. placebo versus low dose, placebo versus medium dose, placebo versus high dose) we calculated the MD, the SD of the difference and its standard error (SE), the SMD, the pooled SD, and the SE of the SMD in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We used a correlation coefficient of 0.6 in our calculation of the SE (of the MD and the SMD), as this was the within‐subject correlation calculated by RUPP 2005, based on three methylphenidate cross‐over studies involving participants with developmental disabilities.

In the case that studies reported the mean outcome measure for two raters rating the same children using the same scale separately, we combined the data from the two raters by averaging the scores and calculating the combined SD, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

See also Appendix 5 and Redman 2014.

Dealing with missing data

When necessary, we contacted the authors of included studies for information regarding missing data, dropouts and/or data not included in the study report but relevant to the review; for example, we sought outcomes of interest and summary data (such as number of participants and events) if authors had not included them in the published study report. We reported our attempt to obtain additional data and the results of these attempts in the Results section.

See also Appendix 5 and Redman 2014.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity in two steps. First, we assessed clinical heterogeneity by comparing the populations included in the studies, the settings, the treatment modalities, and the outcomes. Clinical heterogeneity was considered sufficient to preclude the pooling of studies if: the participant ages were obviously different (for example, we did not combine data from studies of teenagers aged 16 to 18 years with data from studies of children aged 6 to 8 years); the severity of the ASD was obviously different (for example, we did not combine data from studies of children who require institutional care with data from studies of those with mild symptoms causing little impairment); or the outcome measures were not clinically comparable (for example, we did not combine data from a study that only measures impulsivity with data from a study that only measures hyperactivity).

Second, we assessed statistical heterogeneity by performing a Chi2 test and calculating the I2 value according to the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2017). We interpreted the I2 value as follows (Deeks 2017).

0% to 40%: may not be important.

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We were unable to identify small study effects and publication bias using a funnel plot because of the small number of included studies. See Appendix 5 and Redman 2014.

Data synthesis

We pooled the available data using the generic inverse variance method, and we applied a random‐effects model (Deeks 2017). In the absence of clinical or statistical heterogeneity (see Assessment of heterogeneity), we also applied a fixed‐effect model for pooling, and we compared the effect estimates obtained from each of the two methods in order to assess the robustness of the estimates.

Measures of effect size using SMDs are difficult to interpret in terms of whether they represent a clinically important between‐treatment difference, or a clinically meaningful effect. In this review we used an SMD of 0.52 as a between‐treatment minimum clinically important difference (MCID), based on the Zhang 2005 finding of a MCID of 6.6 on the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale ‐ Parent Interview (ADHDRS‐PI), which was equivalent to an SMD of 0.52. Storebø 2015 also used this SMD of 0.52 as a clinically meaningful effect size. This aligns with the rule of thumb that an effect size of 0.20 to 0.49 represents a small effect; 0.50 to 0.79, a moderate effect; and 0.80 or above, a large effect, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2017).

Summary of findings table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADEpro software, GRADEpro GDT 2015, for our prespecified primary outcome of clinical efficacy, as assessed by an improvement in ADHD‐like symptoms (inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity) and an improvement in symptoms of ASD (including impaired social interaction, impaired communication, and repetitive, restricted or stereotypical behaviour). We also reported one secondary outcome (rates of adverse events) in this table. We reported our findings separately for teacher‐rated and parent‐rated outcomes, and we reported the results for high doses of methylphenidate.

We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the evidence of studies contributing data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes (GRADE 2004). We included the following comparisons: low dose methylphenidate versus placebo, medium dose methylphenidate versus placebo, and high dose methylphenidate versus placebo. We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (see Higgins 2011a and Schünemann 2017 respectively) and GRADEpro GDT 2015. We justified all decisions to downgrade the quality of studies (from high to moderate, low or very low) using footnotes, and we provided comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed a subgroup analysis on the different doses of methylphenidate (low, medium and high dose).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess:

the effect of the correlation coefficient; one assuming no correlation (correlation coefficient of zero) and one assuming a higher correlation (correlation coefficient of 0.80); and

the influence of the different scales on the same outcome. For example, if trial authors used more than one scale to measure the same outcome in a study, we repeated the meta‐analyses for the different scales in order to assess if this changed the interpretation of our results. We used the SMD to compare the results across the different scales.

See Appendix 5 and Redman 2014.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

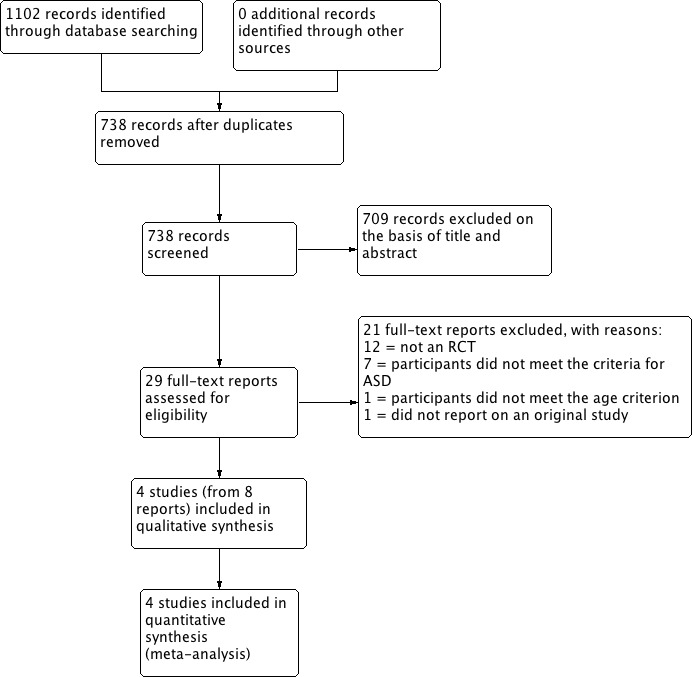

Our searches retrieved a total of 1102 records, of which 364 were duplicates. We screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining 738 records and excluded 709 irrelevant records. We next obtained and assessed the full texts of the remaining 29 reports for eligibility and excluded 21; most of the excluded studies were either not controlled trials or studied participants who did not meet the criteria for ASD (see Excluded studies; Characteristics of excluded studies). We included four studies in the review (see Included studies; Characteristics of included studies). We contacted the corresponding authors of all included studies for further information, but no authors identified additional studies that met our inclusion criteria (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; RUPP 2005). See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included four studies in this review (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; Quintana 1995; RUPP 2005). The RUPP 2005 (Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology) study resulted in three journal articles and two conference abstracts, which we treated in the analysis as a single study.

The four included studies all had a randomised, double‐blind, cross‐over design, comparing the effect of placebo and more than one dose of methylphenidate for each study participant. The cross‐over trial design was appropriate for the clinical context, given that ASD is a relatively stable, chronic condition. Furthermore, no period or carry‐over effects would be anticipated for methylphenidate, even in the absence of a washout period, as the elimination half‐life for both the immediate‐ and extended‐release forms is two to three hours (Novartis 2014). The average duration of action of (immediate‐release) methylphenidate is approximately four hours, and the extended‐release form used in Pearson has a duration of action of approximately eight hours (Novartis 2014). Data collection was also focused at the end of each week of intervention, further reducing the risk of any carry‐over effect.

Details for each individual study can be found in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Study design

All studies were cross‐over studies, completed in four to six weeks, comparing placebo with methylphenidate at either two doses, in Handen 2000 and Quintana 1995, or three, in Pearson 2013 and RUPP 2005.

Location of studies

All studies took place in the USA (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; Quintana 1995; RUPP 2005).

Participants

Participant diagnoses

In all four included studies participants had ASD and ADHD‐like symptoms.

In Handen 2000, participants had autistic disorder or pervasive developmental disorder ‐ not otherwise specified (PDD‐NOS) (score on the CARS of 30 or more) and symptoms of ADHD (score of 15 or more on the Hyperactivity Index of the Conners' Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS)).

In Pearson 2013, 19 participants had autistic disorder, three had Asperger's disorder and two had PDD‐NOS and symptoms of ADHD (mean ADHD index score from CTRS‐Revised of 67.2 standard deviation (SD) 8.7), with several participants meeting DSM‐IV‐TR criteria for additional disorders, including oppositional defiant disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder and separation anxiety.

In Quintana 1995, participants had autistic disorder (as assessed with the CARS, ranging from 30.0 to 59.5) and a range of baseline behaviours, including temper tantrums and agitation.

In RUPP 2005, participants had autistic disorder, Asperger's disorder or PDD‐NOS and chronic interfering symptoms of hyperactivity or impulsiveness (or both), as assessed with the Clinician Global Impression ‐ Severity (CGI‐S) scale, ranging from moderately to severely ill.

Participant age and sex

Participant ages ranged from 5 to 11 years in Handen 2000; from 7 to 12 years in Pearson 2013; from 7 to 11 years in Quintana 1995; and from 5 to 13 years in RUPP 2005. All studies recruited more boys than girls: Handen 2000 randomised 13 children (10 boys and 3 girls), Pearson 2013 randomised 24 children (19 boys and 5 girls), Quintana 1995 randomised 10 children (6 boys and 4 girls), and RUPP 2005 randomised 66 children (59 boys and 7 girls).

Participant cognitive status

Participant cognitive functioning ranged from severe/profound intellectual impairment to average IQ (Handen 2000), moderate intellectual impairment (IQ 46) to above average IQ (IQ 112) (Pearson 2013), mild intellectual impairment to average IQ (Quintana 1995), and severe intellectual impairment to above average IQ (Slosson IQ 16 to 135) (RUPP 2005).

Participant recruitment

Investigators recruited participants from special education programmes, a psychiatric inpatient unit or an intensive day‐treatment programme (Handen 2000); special education classrooms of a large metropolitan public school district (Pearson 2013); a state psychiatric institute outpatient clinic (Quintana 1995); and five university outpatient centres (RUPP 2005).

Dose of methylphenidate

Handen 2000 used methylphenidate 0.3 mg/kg/dose two or three times daily, and methylphenidate 0.6 mg/kg/dose two or three times daily.

Pearson 2013 adjusted all doses for participant weight, using 10 mg to 20 mg extended‐release methylphenidate in the morning and 2.5 mg to 5 mg immediate‐release in the afternoon in the low‐dose phase, 15 mg to 30 mg extended‐release methylphenidate in the morning and 5 mg to 10 mg immediate‐release in the afternoon in the medium‐dose phase, and 20 mg to 40 mg extended‐release methylphenidate in the morning and 5 mg to 10 mg immediate‐release in the afternoon in the high‐dose phase.

Quintana 1995 used methylphenidate 10 mg and methylphenidate 20 mg, twice a day.

RUPP 2005 adjusted all doses for participant weight, using 2.5 mg to 5 mg methylphenidate two to three times daily, 5 mg to 10 mg methylphenidate two to three times daily, and 10 mg to 20 mg methylphenidate two to three times daily.

Outcomes

The outcomes reported were: overall severity of ADHD symptoms (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; Quintana 1995; RUPP 2005); hyperactivity (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; Quintana 1995; RUPP 2005); hyperactivity/impulsivity (RUPP 2005); restlessness‐impulsivity (Pearson 2013); inattention (Pearson 2013; RUPP 2005); overall severity of core features of autism (Handen 2000); lethargy/social withdrawal (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013); social skills (Pearson 2013); social communication with respect to joint attention (RUPP 2005); inappropriate speech (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013); stereotypic behaviour (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; Quintana 1995); compulsive/repetitive behaviour (RUPP 2005); irritability (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; Quintana 1995); aggression (Handen 2000); emotional lability (Pearson 2013); oppositional behaviour (Pearson 2013); oppositional defiant disorder (RUPP 2005); self‐regulation (RUPP 2005); compliance (RUPP 2005); regulated affective state (RUPP 2005); abnormal involuntary movements (Quintana 1995); any other atypical behaviours (Pearson 2013) and presence or severity (or both) of common adverse events of methylphenidate (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; Quintana 1995; RUPP 2005).

Outcome measurement

Included studies used a number of different psychometric instruments or scales to measure our primary outcomes (see Table 3 for symptoms of ADHD and Table 4 for symptoms of ASD). Neither Handen 2000 nor Quintana 1995 nominated a primary outcome measure. Pearson 2013 justified the use of the CTRS‐Revised as their primary outcome measure because it had been shown previously in the literature to be "sensitive to medication treatment response in children with ADHD in the general school‐age population and in children with ASD and symptoms of ADHD". RUPP 2005 did not justify the use of the teacher‐rated hyperactivity subscale of Aberrant Behaviour Checklist as their primary outcome measure.

1. Instruments used to measure ADHD outcomes.

| Instrument | Inattention | Impulsivity | Hyperactivity | |||

| Teachera | Parent | Teachera | Parent | Teachera | Parent | |

| ABC | — | — | — | — | H, Q, R | P, R |

| ACTeRS | P | P | — | — | P | P |

| Conners' Global Index | — | — | P | P | P | P |

| CPRS‐R and CTRS‐R | P | P | — | — | P, Q | P |

| Conners' Abbreviated Parent/Teacher Questionnaire | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| SNAP‐IV | P, R | P, R | — | — | P , R | P, R |

a'Teacher' includes clinician and trained observer raters.

Letters (H, P, Q, R) indicate those studies that used a particular instrument to rate the particular outcome. Letters in bold and underlined font indicate the instrument we used in our meta‐analysis: H: Handen 2000; P: Pearson 2013; Q: Quintana 1995; R: RUPP 2005.

ABC: Aberrant Behavior Checklist; ACTeRS: ADD‐H (Attention deficit disorder ‐ hyperactivity) Comprehensive Teacher Rating Scale; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CPRS‐R: Conners' Parent Rating Scale ‐ Revised; CTRS‐R: Conners' Teacher Rating Scale ‐ Revised;SNAP‐IV: Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Questionnaire, Fourth Edition.

2. Instruments used to measure ASD outcomes.

| Instrument | Impaired social interaction | Impaired communication | Stereotypical behaviours | Overall ASD | ||||

| Teacher a | Parent | Teacher a | Parent | Teacher a | Parent | Teacher a | Parent | |

| ABC | H | P | H | P | H, Q | P | — | — |

| ACTeRS | P | P | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CARS | — | — | — | — | — | — | H | — |

| CYBOCS | — | — | — | — | R | — | — | — |

| CPRS‐R and CTRS‐R | P | P | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Iowa CTRS | H | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Social communication questionnaire | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | P |

| SNAP‐IV | R | R | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Clinician Global Impression ‐ Severity | — | — | — | — | — | — | P | — |

a'Teacher' includes clinician and trained observer raters;

Letters (H, P, Q, R) indicate the studies which used a particular instrument to rate the particular outcome. Letters in bolded and underlined font indicate the instrument we used in our meta‐analysis: H: Handen 2000; P: Pearson 2013; Q: Quintana 1995; R: RUPP 2005;

ABC: Aberrant Behavior Checklist; ACTeRS: ADD‐H (Attention deficit disorder ‐ hyperactivity) Comprehensive Teacher Rating Scale; ASD: autism spectrum disorders; CARS: Child Autism Rating Scale; CPRS‐R: Conners' Parent Rating Scale ‐ Revised; CTRS‐R: Conners' Teacher Rating Scale ‐ Revised; CYBOCS: Children's Yale‐Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scales;Iowa CTRS: Iowa Conners' Teacher Rating Scale; SNAP‐IV: Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Questionnaire, 4th Edition.

Study and author funding

The Fanny Pushkin Rosenberg Research Foundation provided study funding for Handen 2000, and the National Institute of Mental Health Bethesda, the National Institutes of Health Bethesda, and the Korczak Foundation for RUPP 2005. One or more study authors in Pearson 2013 had received funding from or served as a consultant or advisor for: the Forest Research Institute, Curemark LLC, United Biosource Corporation, BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Confluence Pharmaceutica, Hoffman LaRoche, Johnson & Johnson, Supernus Pharmaceutica, Shire, Lilly, Organon, Sigma Tau, Targacept, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Noven, Seaside Therapeutics, Abbotts Laboratories, Pearson Assessments/Psychological Corporation or Ezra Innovations. Quintana 1995 did not report funding sources.

Excluded studies

We excluded 21 studies from this review: 12 because they were not a RCT (Akyol 2015; Aman 1991; Armstrong 2008; Barnard‐Brak 2016; Birmaher 1988; Croteau 2013; Di Martino 2004; Flapper 2008; Gurbuz 2016; Mayes 1994; Scahill 2007; Sinzig 2014); 7 because the participants did not meet the criteria for ASD (Aman 1997; Epstein 2011; Faraone 2001; Simonoff 2013; Steele 2006; Von Morgenstern 2014; Çetín 2015); 1 because it did not report on an original study (Shea 2006), and 1 because the participants in the study did not meet the age criterion (Ghuman 2009).

The excluded RCTs included Aman 1997, which was a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over study of methylphenidate and different doses of fenfluramine in children with mental retardation or borderline IQ and ADHD; participants did not meet criteria for ASD. Birmaher 1988 studied methylphenidate in children with autism and features of ADHD, but this was not a randomised controlled trial. Ghuman 2009 was a randomised, controlled, double‐blind, cross‐over study of methylphenidate for ADHD symptoms in preschoolers with ASD or developmental delay (IQ of less than 70), but participants were aged from three to five years, which is younger than the cutoff for inclusion in our review. Di Martino 2004 studied methylphenidate in children with autism or pervasive developmental disorder and features of ADHD, but it was not a RCT. Simonoff 2013 was a randomised, controlled, double‐blind trial of optimal dose methylphenidate in children and adolescents with severe ADHD and intellectual disability (IQ 30 to 69), but although it measured symptoms of autism using the parent‐reported Social Communication Questionnaire, participants did not meet criteria for ASD. Steele 2006 was an open‐label, randomised trial comparing immediate‐release methylphenidate with extended‐release methylphenidate in children with a diagnosis of ADHD, but although parent stress and social play were measured, participants did not meet criteria for ASD. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

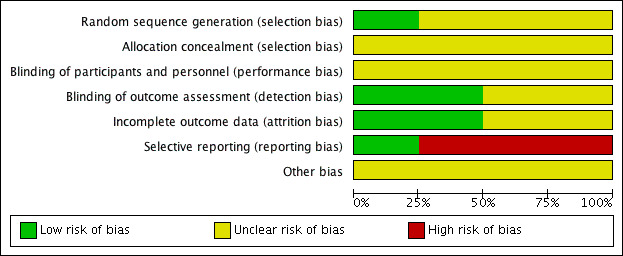

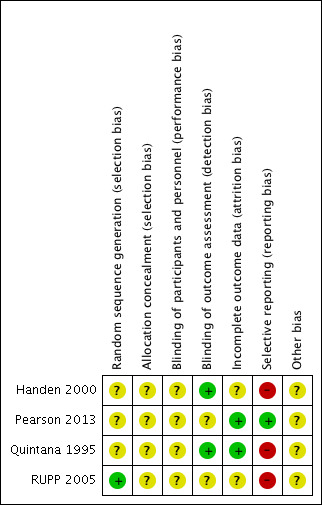

We assessed all of the included trials for risk of bias across the seven domains of the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2017). The results of this assessment are shown for each study in the 'Risk of bias' tables, beneath the Characteristics of included studies tables and summarised in 'Risk of bias' graphs (Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

We assessed three studies as being at unclear risk of selection bias based on inadequate information about the generation of random numbers (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; Quintana 1995). One study, RUPP 2005, reported an appropriate method for generating a random numbers list, so we considered it to be at low risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

We rated all four studies at unclear risk of selection bias based on inadequate information about the method of allocation concealment (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; Quintana 1995; RUPP 2005).

Blinding

None of the studies provided enough information to assess to what extent blinding had been successful.

Performance bias

We considered the risk of performance bias to be unclear in all four studies (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013; Quintana 1995; RUPP 2005).

The main issue was inadequate information about whether participants had taken methylphenidate prior to the study, and hence whether some of these children and their parents could have recognised the active medication (by recognising adverse events, for example) (Handen 2000; Pearson 2013). The corresponding author for Handen 2000 was unable to retrieve this information but indicated that from his recall some participants were likely to have had previous exposure to methylphenidate.

Detection bias

We considered the risk of detection bias to be low in Handen 2000 and Quintana 1995 and unclear in Pearson 2013 and RUPP 2005.

The study staff were unblinded during the test‐dose week in Pearson 2013 and RUPP 2005.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed two studies, Pearson 2013 and Quintana 1995, to be at low risk of attrition bias, because all missing data were accounted for. We assessed Handen 2000 to be at unclear risk of attrition bias because there was insufficient information about the method of imputing missing data, and the corresponding author was not able to retrieve this information. We assessed RUPP 2005 to be at unclear risk of attrition bias because outcome data for the impaired communication outcome was incomplete.

Selective reporting

We considered the risk of reporting bias to be high in Handen 2000, Quintana 1995 and RUPP 2005, and low in Pearson 2013. We assessed Handen 2000 to be at high risk of reporting bias because authors did not provide parent ratings (although they reported that this outcome was incomplete because many participants resided in inpatient clinics or residential halls). Quintana 1995 did not report CARS outcomes, despite listing the CARS score as an outcome. We were unable to contact the corresponding author to clarify this. RUPP 2005 did not report the Clinician Global Impression ‐ Improvement subscale score outcome, although it was used in a composite score to define response. In addition, two subsequent publications (in 2007 and 2009, see RUPP 2005) reported additional outcomes that the original publication did not mention. We rated Pearson 2013 at low risk of reporting bias because the reporting of outcomes was comprehensive.

Other potential sources of bias

We considered all four studies to be at unclear risk of bias due to a lack of information about either study funding (in Handen 2000 and Quintana 1995) or potential conflicts of interest of the investigators/authors (in Pearson 2013 and RUPP 2005). The corresponding author of Handen 2000 could not retrieve this information, and we were unable to contact the corresponding author of Quintana 1995. It is unclear if the affiliations with pharmaceutical companies reported in RUPP 2005 represent a risk of bias, so we judged this study to be at unclear risk of bias. We assessed Pearson 2013 at unclear risk of bias, because the authors reported having received previous financial support from a number of pharmaceutical companies (including manufacturers of pharmaceuticals for behavioural syndromes in children), although the included study was not funded by any pharmaceutical companies.

Effects of interventions

We presented the results for the primary outcome, clinical efficacy (defined as an improvement in ADHD‐like symptoms and an improvement in symptoms of ASD), as rated by teachers for high‐dose methylphenidate in Table 1, and as rated by parents for high‐dose methylphenidate in Table 2.

Below, we report the results separately for the features of ADHD, the core symptoms of ASD and overall ASD. For symptoms of ADHD, we report results on inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity, as rated by teachers and parents separately. For ASD outcomes, we report results on impaired social interaction, impaired communication, and stereotypical behaviours as well as overall ASD, as rated by teachers and parents separately. No meta‐analysis was possible for the primary outcomes of impulsivity or impaired communication, as only Pearson 2013 measured impulsivity and impaired communication as rated by parents, and only Handen 2000 measured impaired communication as rated by teachers.

Doses differed between studies, with some using doses calculated per kg of participant body weight, and others using proprietary doses of 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg and 20 mg of methylphenidate with adjustment for participant weight. Doses were three times daily in two studies: Handen 2000, although parents elected to omit the third daily dose for 2/13 children, and RUPP 2005, where the third dose was half of the earlier doses, and no information was available about whether any parents elected to omit the third dose. Quintana 1995 and Pearson 2013 administered doses twice daily, although parents elected to omit the second dose in 5/24 children in the Pearson 2013 study because of "behaviour concerns in the late afternoon/evening".

A number of different psychometric instruments/scales were used both across and within included studies to measure our primary outcomes (see Table 3 for ADHD‐like symptoms and Table 4 for symptoms of ASD). Where an included study used more than one outcome measure, we used the measure in our analysis, which was also used by one or more of our other included studies. This was a pragmatic approach given the absence of a generally accepted gold standard outcome instrument/scale. We therefore report effect sizes as measured on the most commonly used scales across our included studies. The scales used in our meta‐analysis are highlighted in bold and underlined font in Table 3 and Table 4. We used a coefficient of 0.6, which was the within‐subject correlation calculated by RUPP 2005 (based on three methylphenidate cross‐over studies involving participants with developmental disabilities), and we performed sensitivity analyses using a coefficient of 0 and 0.8.

No data were available to assess short‐term (1 to 3 months), medium‐term (3 to 6 months) and long‐term (6 to 12 months) outcomes, as the duration of observation was limited to one week under each experimental condition in all included studies.

We were unable to perform subgroup analyses based on ages 6 to 12 years and 13 to 18 years, because only one study, RUPP 2005, included children aged 13 years and did not report any individual data, and no studies included children aged 14 years or older.

We were unable to perform subgroup analyses based on the formulation of methylphenidate. Only one study, Pearson 2013, used an extended‐release form, so we were unable to compare extended‐release with immediate‐release formulations. Furthermore, Pearson 2013 used both extended‐release methylphenidate (for the morning dose) and immediate‐release methylphenidate (for the afternoon dose, if it was administered). However, parents were asked to focus only on their child's morning behaviour for their ratings, and teachers only saw the children on the extended‐release dose; therefore, we considered this study to have a single treatment arm (extended‐release methylphenidate). No studies used transdermal preparations, so we were unable to compare oral with transdermal methylphenidate.

No data were available on the secondary outcomes of caregiver well‐being; need for institutionalisation, special schooling options or therapy to achieve learning outcomes; or overall quality of life.

Primary outcomes: clinical efficacy

1. Improvement in ADHD‐like symptoms: inattention

Two studies measured inattention as rated by teachers and parents (Pearson 2013; RUPP 2005). Both studies used the inattention subscale of the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham, Fourth Version (SNAP‐IV) questionnaire, which was used in our primary analysis. This subscale consists of nine items, which are measured on a rating scale ranging from zero to three. Pearson 2013 also used the cognitive‐inattention subscale of the Conners' Parent Rating Scale ‐ Revised (CPRS‐R) short form, and the inattention subscale of the ADD‐H (attention deficit disorder ‐ hyperactivity) Comprehensive Teacher Rating Scale (ACTeRS). See Table 3.

Participants in the Pearson 2013 study differed from those in the RUPP 2005 study in three ways. First, 13/24 children had previous methylphenidate exposure, whereas RUPP 2005 excluded children who had had an adequate trial of methylphenidate in the previous two years. Second, participants in the RUPP 2005 study may have been more unwell than those in the Pearson 2013 study; children in the Pearson 2013 study were rated moderately to severely ill by clinicians and recruited from psychiatric outpatient clinics, while children in the RUPP 2005 study were recruited from special education classrooms. Finally, unlike those in RUPP 2005, participants in the Pearson 2013 study were permitted to remain on other prescribed psychotropic medication, including antidepressant and antipsychotic medication. However, we did not consider that these minor differences were sufficient to preclude their data being combined.

We downgraded the quality of evidence of the pooled effect for both teacher‐rated and parent‐rated inattention to low, due to imprecision (data came from only two small studies), and limitations in study design and implementation in both studies.

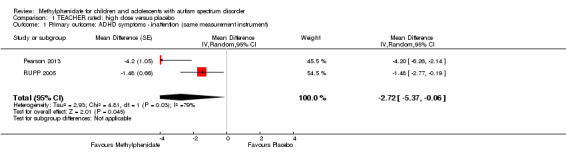

1.1 Teacher rated

The pooled difference between treatment and placebo was statistically significant and favoured the treatment group (MD −2.72 points, 95% CI −5.37 to −0.06, rated on SNAP‐IV inattention subscale, range 0 to 27; 2 studies, 51 participants; Analysis 1.1; Table 1).

1.1. Analysis.

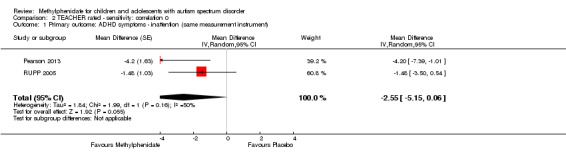

Comparison 1 TEACHER rated: high dose versus placebo, Outcome 1 Primary outcome: ADHD symptoms ‐ inattention (same measurement instrument).

An I2 of 79% indicated considerable heterogeneity.

As a sensitivity analysis, we applied a correlation coefficient of 0 and of 0.8. When we applied a correlation coefficient of 0, the pooled difference between treatment and placebo was no longer statistically significant (MD −2.55 points, 95% CI −5.15 to 0.06, rated on SNAP‐IV inattention subscale, range 0 to 27; 2 studies, 51 participants; Analysis 2.1). When we applied a correlation coefficient of 0.8, the pooled difference between treatment and placebo remained statistically significant and in favour of the treatment group (MD −2.77 points, 95% CI −5.43 to −0.11 rated on SNAP‐IV inattention subscale, range 0 to 27; 2 studies, 51 participants; Analysis 3.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 TEACHER rated ‐ sensitivity: correlation 0, Outcome 1 Primary outcome: ADHD symptoms ‐ inattention (same measurement instrument).

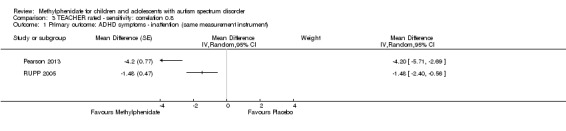

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 TEACHER rated ‐ sensitivity: correlation 0.8, Outcome 1 Primary outcome: ADHD symptoms ‐ inattention (same measurement instrument).

Both studies used the SNAP‐IV measurement scale. Pearson 2013 also used the CPRS‐R and the ACTeRS. Our conclusions did not change when the ACTeRS and the CTRS‐R results were substituted as a sensitivity analysis.

1.2 Parent rated

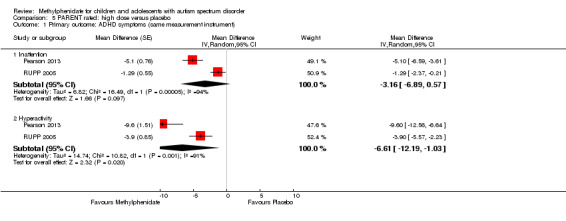

The pooled difference between treatment and placebo was not statistically significant (MD −3.16 points, 95% CI −6.89 to 0.57, rated on SNAP‐IV inattention subscale, range 0 to 27; 2 studies, 71 participants; Analysis 5.1; Table 2).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 PARENT rated: high dose versus placebo, Outcome 1 Primary outcome: ADHD symptoms (same measurement instrument).

An I2 of 86% indicated considerable heterogeneity.

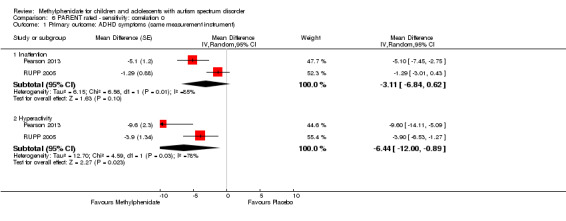

As a sensitivity analysis, we applied a correlation coefficient of 0 and of 0.8. Using a correlation coefficient of 0 (MD −3.11 points, 95% CI −6.84 to 0.62, rated on SNAP‐IV inattention subscale, range 0 to 27; 2 studies, 71 participants; Analysis 6.1), as well as 0.8 (MD −3.18 points, 95% CI −6.91 to 0.56, rated on SNAP‐IV inattention subscale, range 0 to 27; 2 studies, 71 participants; Analysis 7.1), we could not rule out that the pooled difference between treatment and placebo may have been due to chance.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 PARENT rated ‐ sensitivity: correlation 0, Outcome 1 Primary outcome: ADHD symptoms (same measurement instrument).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 PARENT rated ‐ sensitivity: correlation 0.8, Outcome 1 Primary outcome: ADHD symptoms (same measurement instrument).

Both studies used the SNAP‐IV measurement scale. Pearson 2013 also used the CPRS‐R and the ACTeRS. Our conclusions did not change when the ACTeRS and the CTRS‐R results were substituted as a sensitivity analysis.

2. Improvement in ADHD‐like symptoms: impulsivity

Only Pearson 2013 measured impulsivity (as rated by 24 parents and 18 teachers), so we were unable to pool results. Pearson 2013 used the restless‐impulsivity subscale of the Conners' Global Index to measure impulsivity (see Table 3). This scale was rated by parents as well as teachers.

2.1 Teacher rated

Methylphenidate had a significant, beneficial effect compared to placebo on impulsivity as rated by teachers (MD −14.8 points, 95% CI −18.52 to −11.08, rated on Conner's Global Index restless‐impulsivity subscale, range unknown). We note that Pearson 2013 reported that these results were significant, although they did not provide a P value.

2.2 Parent rated