Abstract

Background

Supportive therapy is often used in everyday clinical care and in evaluative studies of other treatments.

Objectives

To review the effects of supportive therapy compared with standard care, or other treatments in addition to standard care for people with schizophrenia.

Search methods

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's register of trials (November 2012).

Selection criteria

All randomised trials involving people with schizophrenia and comparing supportive therapy with any other treatment or standard care.

Data collection and analysis

We reliably selected studies, quality rated these and extracted data. For dichotomous data, we estimated the risk ratio (RR) using a fixed‐effect model with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Where possible, we undertook intention‐to‐treat analyses. For continuous data, we estimated the mean difference (MD) fixed‐effect with 95% CIs. We estimated heterogeneity (I2 technique) and publication bias. We used GRADE to rate quality of evidence.

Main results

Four new trials were added after the 2012 search. The review now includes 24 relevant studies, with 2126 participants. Overall, the evidence was very low quality.

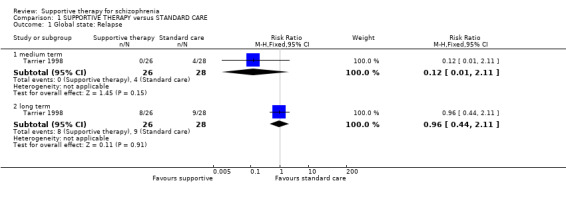

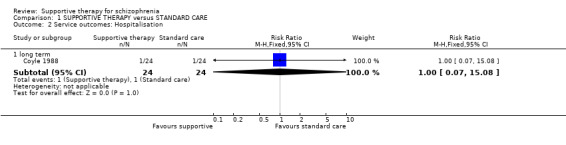

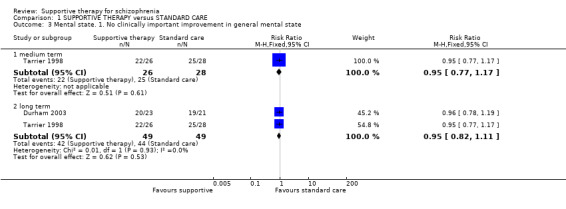

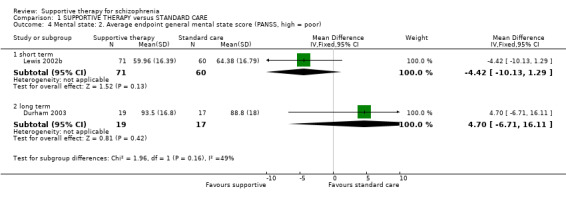

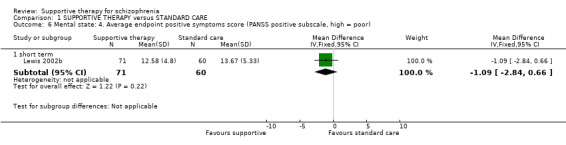

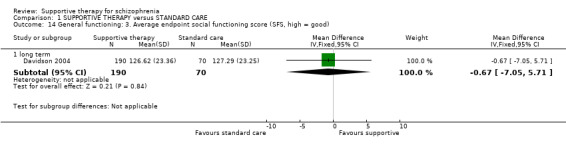

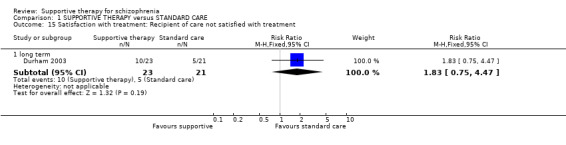

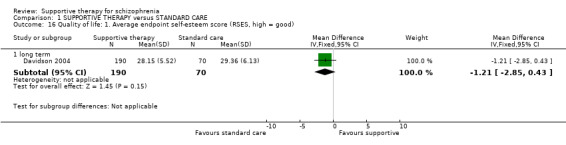

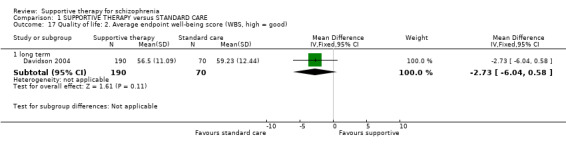

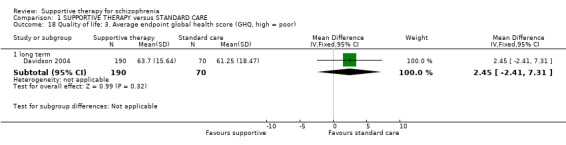

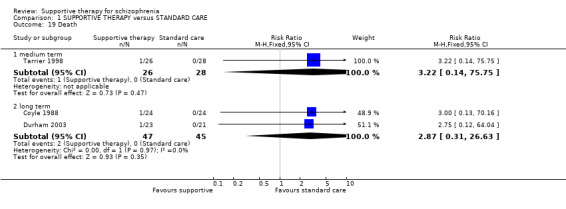

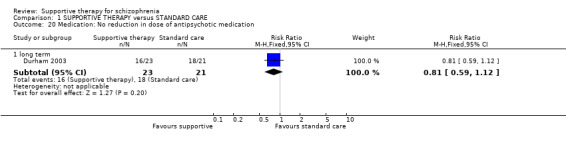

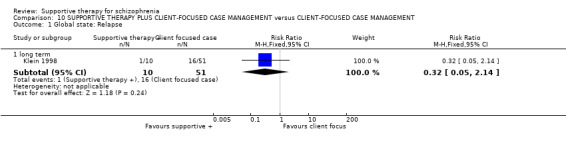

We found no significant differences in the primary outcomes of relapse, hospitalisation and general functioning between supportive therapy and standard care.

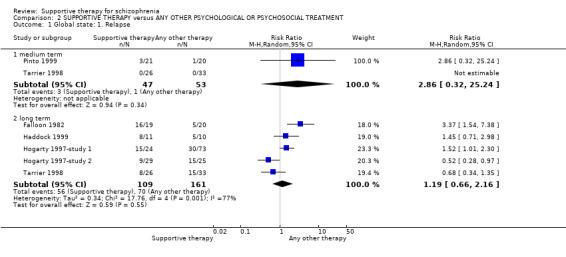

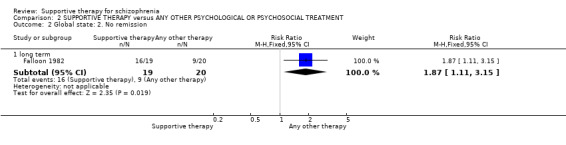

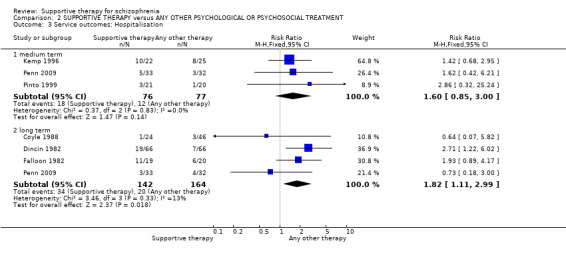

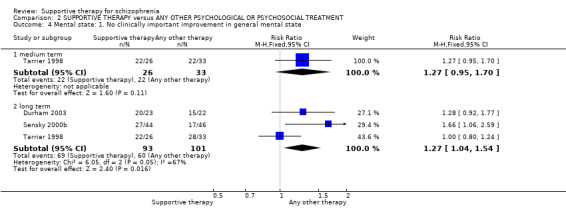

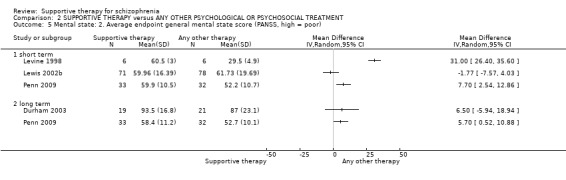

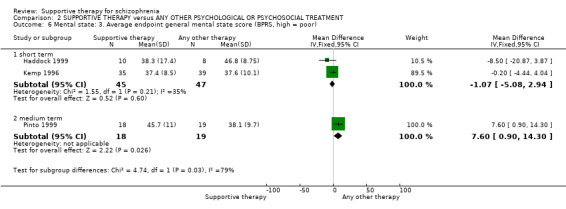

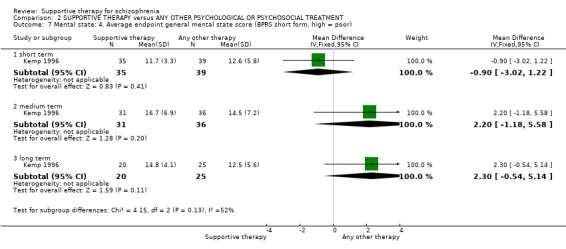

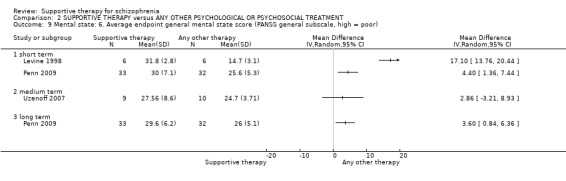

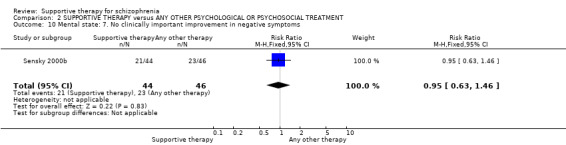

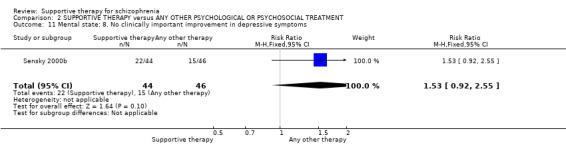

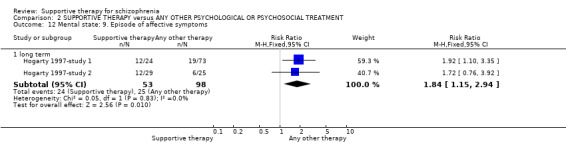

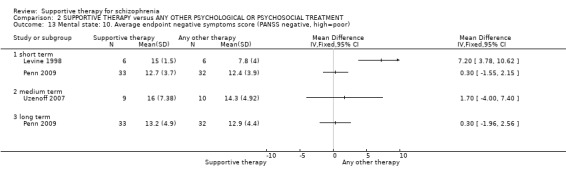

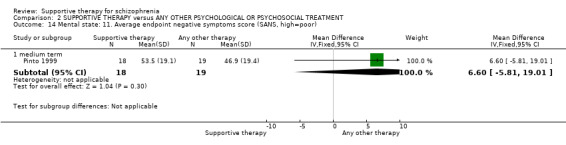

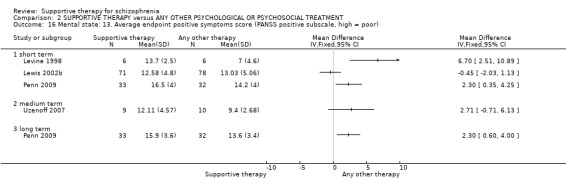

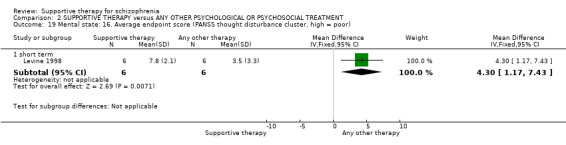

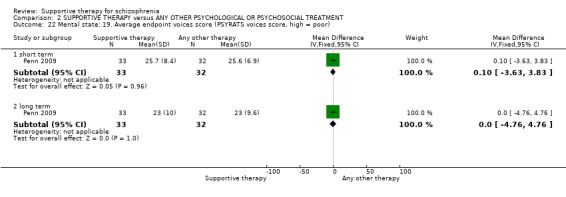

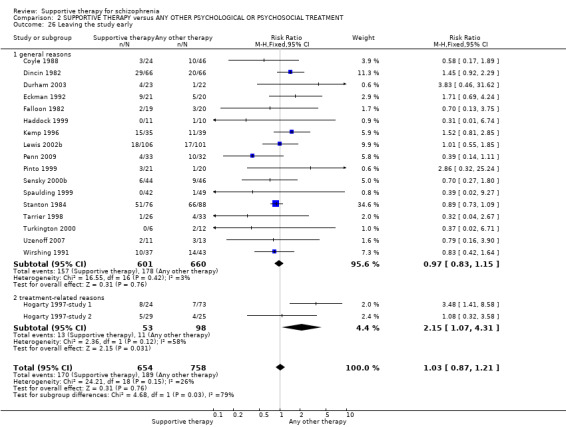

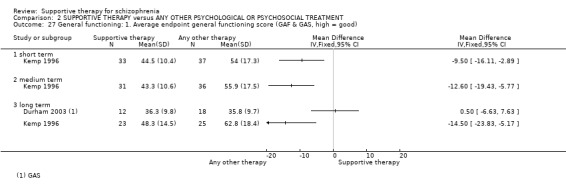

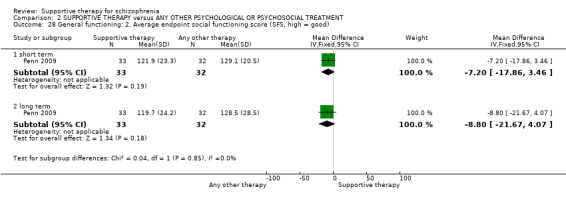

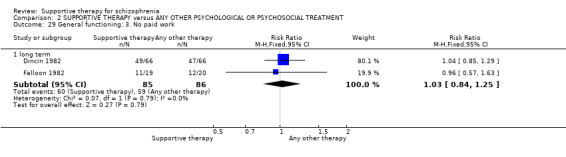

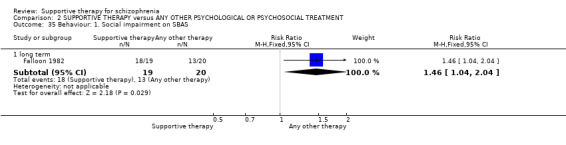

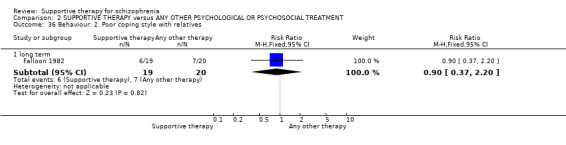

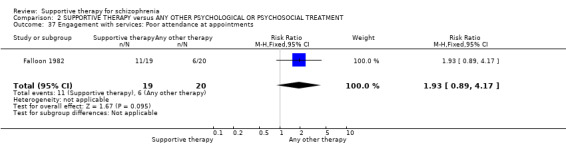

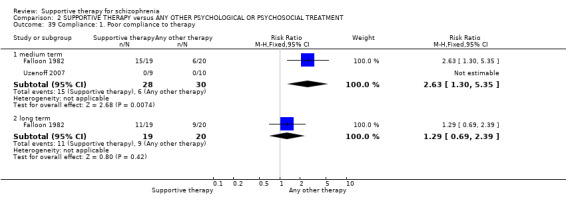

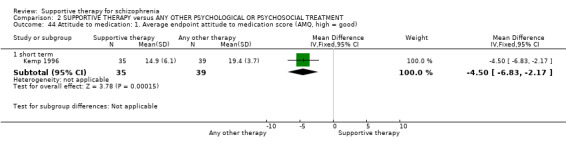

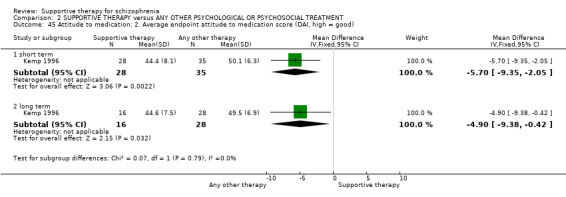

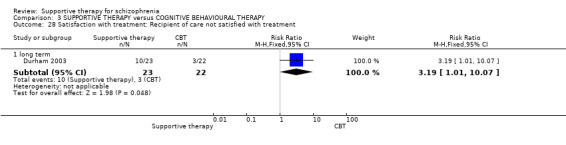

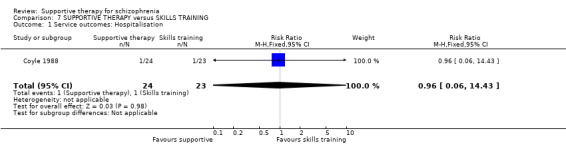

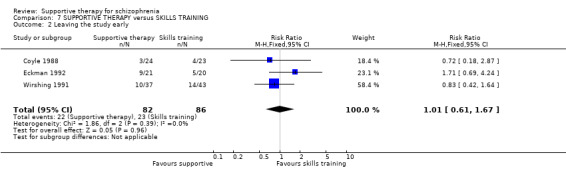

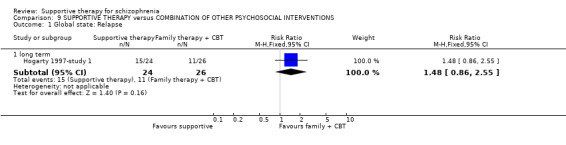

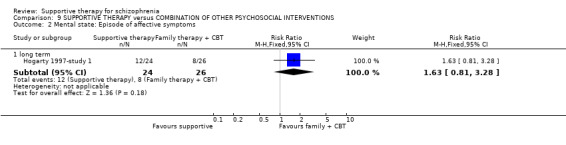

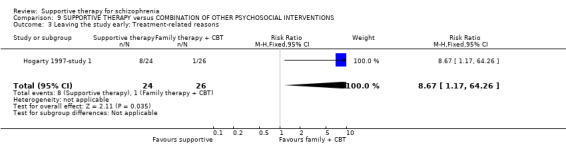

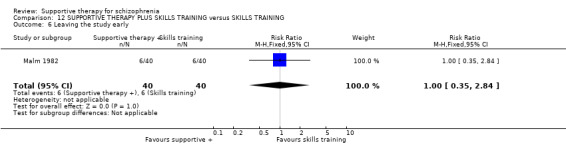

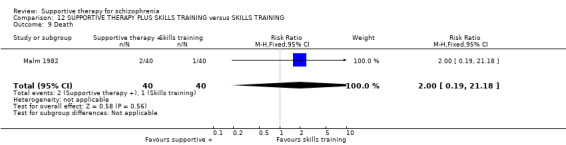

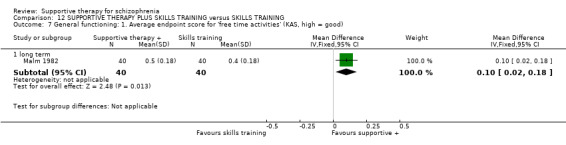

There were, however, significant differences favouring other psychological or psychosocial treatments over supportive therapy. These included hospitalisation rates (4 RCTs, n = 306, RR 1.82 CI 1.11 to 2.99, very low quality of evidence), clinical improvement in mental state (3 RCTs, n = 194, RR 1.27 CI 1.04 to 1.54, very low quality of evidence) and satisfaction of treatment for the recipient of care (1 RCT, n = 45, RR 3.19 CI 1.01 to 10.7, very low quality of evidence). For this comparison, we found no evidence of significant differences for rate of relapse, leaving the study early and quality of life.

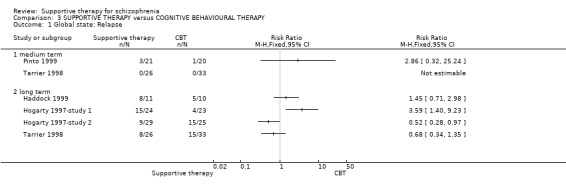

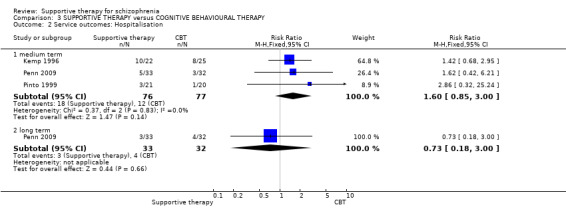

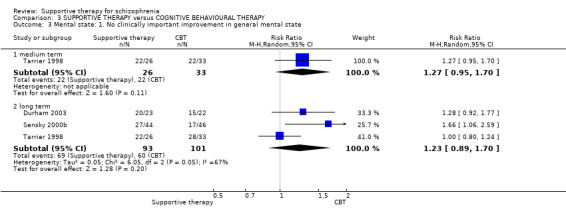

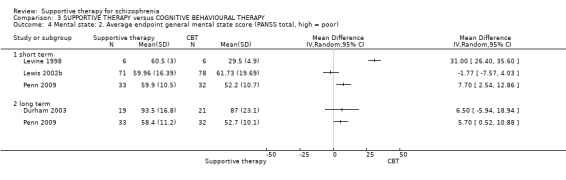

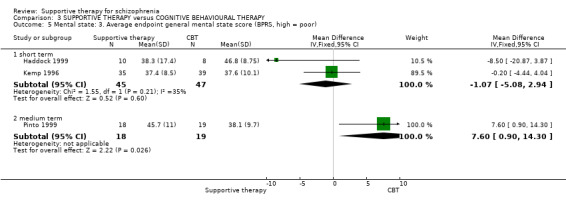

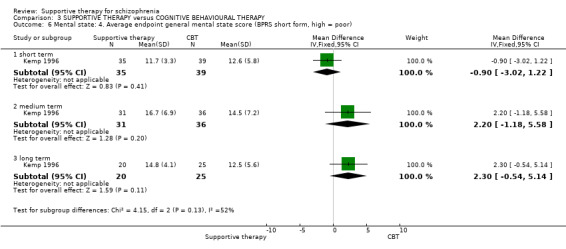

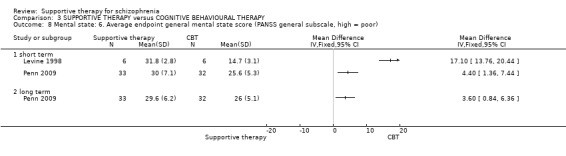

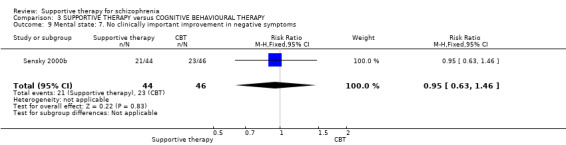

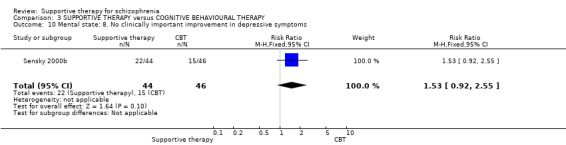

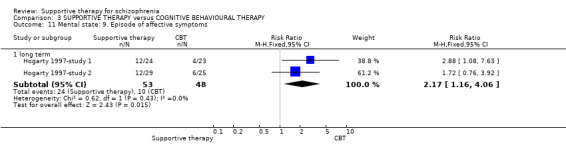

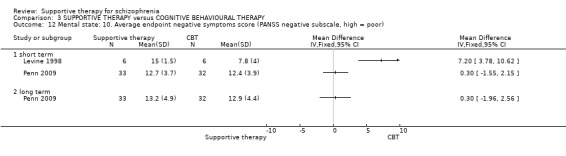

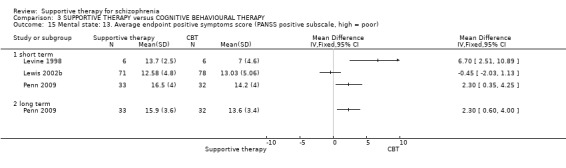

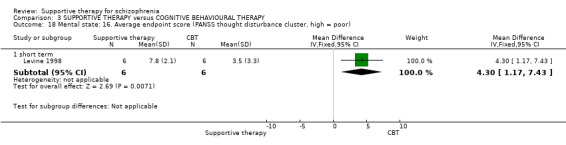

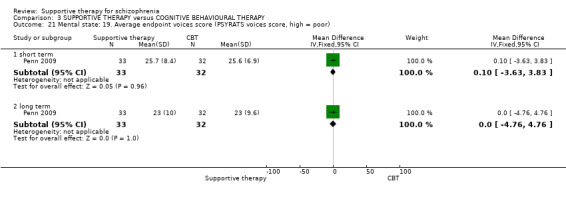

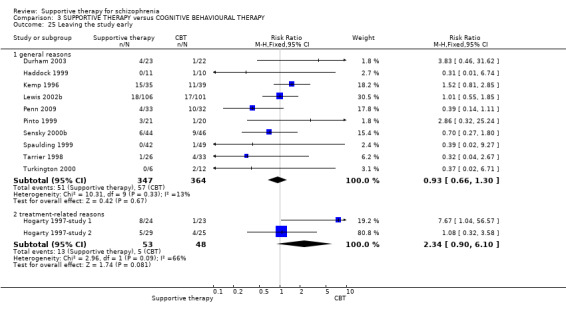

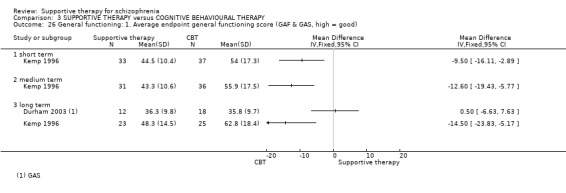

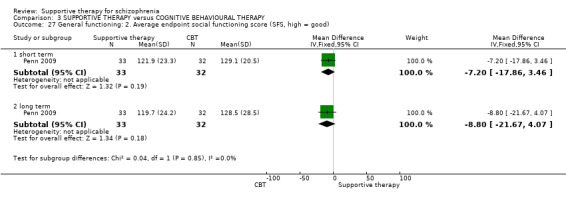

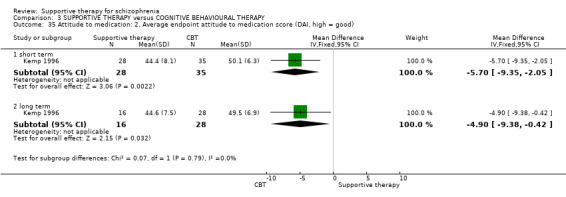

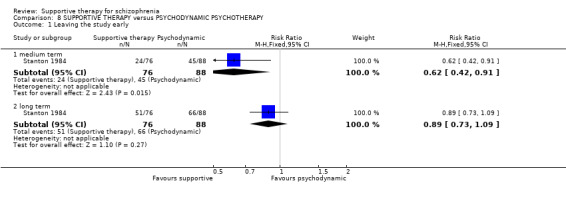

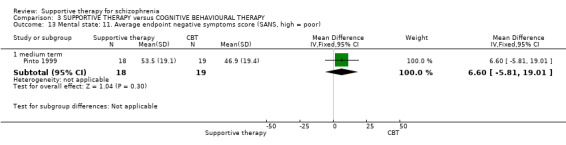

When we compared supportive therapy to cognitive behavioural therapy CBT), we again found no significant differences in primary outcomes. There were very limited data to compare supportive therapy with family therapy and psychoeducation, and no studies provided data regarding clinically important change in general functioning, one of our primary outcomes of interest.

Authors' conclusions

There are insufficient data to identify a difference in outcome between supportive therapy and standard care. There are several outcomes, including hospitalisation and general mental state, indicating advantages for other psychological therapies over supportive therapy but these findings are based on a few small studies where we graded the evidence as very low quality. Future research would benefit from larger trials that use supportive therapy as the main treatment arm rather than the comparator.

Plain language summary

Supportive therapy for schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a severe mental illness with ‘positive symptoms’ such as hallucinations (hearing voices and seeing things) and delusions (having strange beliefs). People with schizophrenia also suffer from disorganisation and ‘negative symptoms’ (such as tiredness, apathy and loss of emotion). People with schizophrenia may find it hard to socialise and find employment. Schizophrenia is considered one of the most burdensome illnesses in the world. For some people it can be a lifelong condition. Most people with schizophrenia will be given antipsychotic medications to help relieve the symptoms. In addition to this they can also receive therapy, of which there are various types. One therapy often given to people with schizophrenia is supportive therapy, where typically after a person is established in the care of mental health services, they will receive general support rather than specific talking therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). For example, in consultations with health professionals there will often be time given to listening to people’s concerns, providing encouragement, or even arranging basic help with daily living. Many people with schizophrenia also receive support from their family and friends. Supportive therapy has been described as the treatment of choice for most people with mental illness and may be one of the most commonly practiced therapies in mental health services.

It is, however, difficult to answer the question of exactly what supportive therapy is. It is difficult to find a widely accepted definition of supportive therapy. For the purposes of this review, supportive therapy includes any intervention from a single person aimed at maintaining a person’s existing situation or assisting in people’s coping abilities. This includes interventions that require a trained therapist, such as supportive psychotherapy, as well as other interventions that require no training, such as 'befriending'. Supportive therapy does not include interventions that seek to educate, train or change a person’s way of coping.

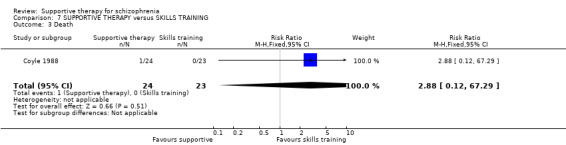

The aim of this review is to assess the effectiveness of supportive therapy compared to other specific therapies or treatment as usual. This update is based on a search run in 2012; the review now includes 24 randomised studies with a total of 2126 people. The studies compared supportive therapy either with standard care alone or a range of other therapies such as CBT, family therapy and psychoeducation. The participants continued to receive their antipsychotic medication and any other treatment they would normally receive during the trials. Overall, the quality of evidence from these studies was very low. There is not enough information or data to identify any real therapeutic difference between supportive therapy and standard care. There are several outcomes, including hospitalisation, satisfaction with treatment and general mental state, indicating advantages for other psychological therapies over supportive therapy. However, these findings are limited because they are based on only a few small studies where the quality of evidence is very low. There was very limited information to compare supportive therapy with family therapy and psychoeducation as most studies in this review focused on other psychological therapies, such as CBT. Apart from one study presenting data on death, there was no information on the adverse effects of supportive therapy. In summary, there does not seem to be much difference between supportive therapy, standard care and other therapies. Future research would benefit from larger studies where supportive therapy is the main treatment.

Ben Gray, Senior Peer Researcher, McPin Foundation: http://mcpin.org/

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus STANDARD CARE for schizophrenia.

| SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus STANDARD CARE for schizophrenia | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia

Settings: inpatients and outpatients

Intervention: SUPPORTIVE THERAPY Comparison: STANDARD CARE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus STANDARD CARE | |||||

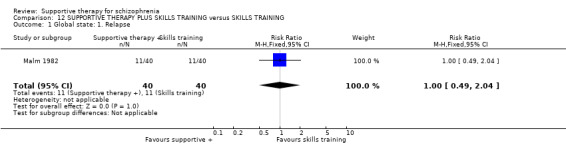

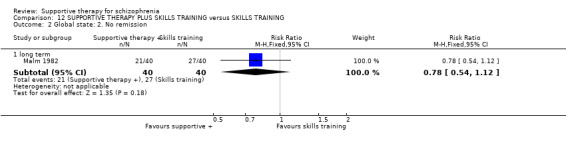

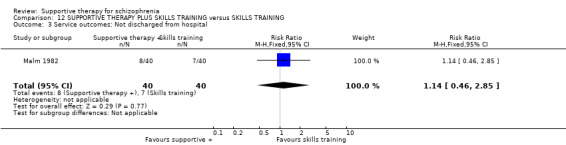

| Global state: Relapse Follow‐up: 2 years | 321 per 1000 | 309 per 1000 (141 to 678) | RR 0.96 (0.44 to 2.11) | 54 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ very low1,2, 3 | |

| Service outcomes: Hospitalisation Follow‐up: 6 months | 42 per 1000 | 42 per 1000 (3 to 628) | RR 1 (0.07 to 15.08) | 48 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| Mental state: no clinically important improvement Follow‐up: 1 to 2 years | 898 per 1000 | 853 per 1000 (736 to 997) | RR 0.95 (0.82 to 1.11) | 98 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

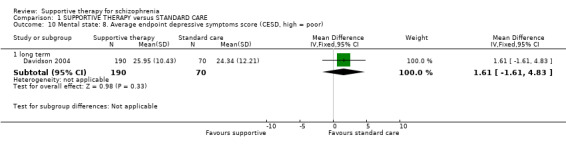

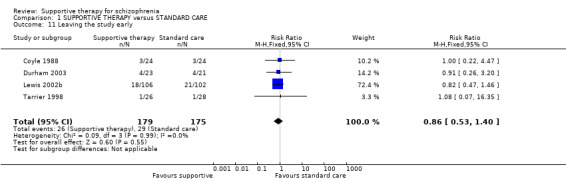

| Leaving the study early Follow‐up: 10 weeks to 2 years | 166 per 1000 | 143 per 1000 (88 to 232) | RR 0.86 (0.53 to 1.4) | 354 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 | |

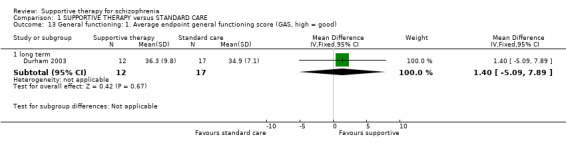

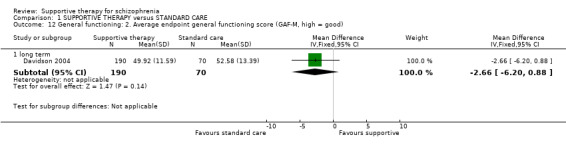

| General functioning GAS Follow‐up: 1 years | The mean general functioning in the intervention groups was 1.4 higher (5.09 lower to 7.89 higher) | 29 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,5,6 | |||

| Satisfaction with treatment: Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment Follow‐up: 1 years | 238 per 1000 | 436 per 1000 (179 to 1000) | RR 1.83 (0.75 to 4.47) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,5 | |

| Quality of life WBS | The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 2.73 lower (6.04 lower to 0.58 higher) | 260 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,5,6 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Imprecision: serious ‐ relatively few participants were included and few events; confidence intervals are wide. 2 Publication bias: strongly suspected ‐ four studies or fewer reported data for this outcome. 3 Risk of bias: serious ‐ one study had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding. 4 Risk of bias: serious ‐ one study had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation and allocation concealment; two studies had an unclear risk for blinding. 5 Risk of bias: serious ‐ one study had an unclear risk of bias for blinding. 6 Indirectness: serious ‐ we wanted to collect binary data for this outcome, however, only a proxy scale measure was available.

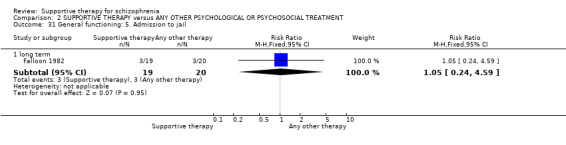

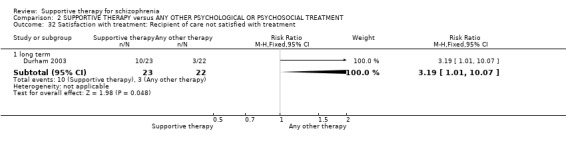

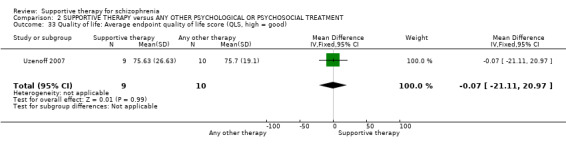

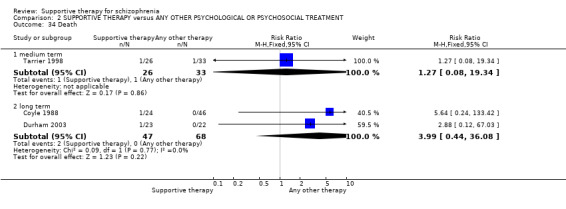

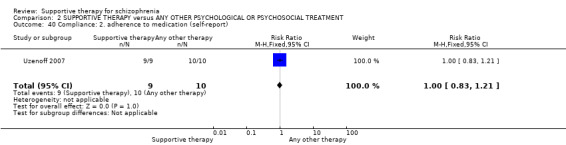

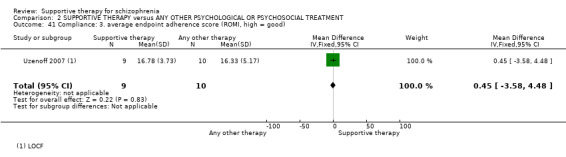

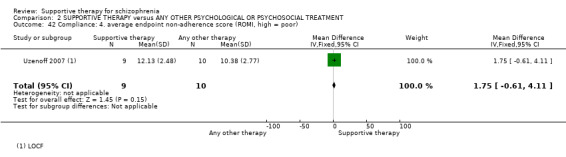

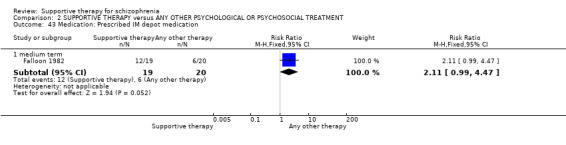

Summary of findings 2. SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus ANY OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL OR PSYCHOSOCIAL TREATMENT for schizophrenia.

| SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus ANY OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL OR PSYCHOSOCIAL TREATMENT for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Settings: inpatients and outpatients Intervention: SUPPORTIVE THERAPY Comparison: ANY OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL OR PSYCHOSOCIAL TREATMENT | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus ANY OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL OR PSYCHOSOCIAL TREATMENT | ||||||

| Global state: Relapse Follow‐up: 2 to 3 years | 435 per 1000 | 517 per 1000 (287 to 939) | RR 1.19 (0.66 to 2.16) | 270 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 | |

| Service outcomes: Hospitalisation Follow‐up: 12 weeks to 2 years | 122 per 1000 | 222 per 1000 (135 to 365) | RR 1.82 (1.11 to 2.99) | 306 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,5 | |

| Mental state: No clinically important improvement Follow‐up: 1 to 2 years | 594 per 1000 | 754 per 1000 (618 to 915) | RR 1.27 (1.04 to 1.54) | 194 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4,6 | |

| Leaving the study early Follow‐up: 10 weeks to 3 years | 249 per 1000 | 257 per 1000 (217 to 302) | RR 1.03 (0.87 to 1.21) | 1412 (19 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate7 | |

| General functioning GAF and GAS Follow‐up: 12 to 18 months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 78 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,8,9,10 | There was very high heterogeneity for this outcome so data were not pooled. 11 |

| Satisfaction with treatment: Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment Follow‐up: 1 years | 136 per 1000 | 435 per 1000 (138 to 1000) | RR 3.19 (1.01 to 10.07) | 45 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,12,13 | |

| Quality of life QLS | The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 0.07 lower (21.11 lower to 20.97 higher) | 19 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,10,13,14 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: serious ‐ four studies had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation and allocation concealment. All studies had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and two had a high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessments. 2 Inconsistency: serious ‐ there was high heterogeneity for this outcome. 3 Imprecision: serious ‐ relatively few participants were included and few events; confidence intervals are wide. 4 Publication bias: strongly suspected ‐ four studies or fewer reported data for this outcome. 5 Risk of bias: serious ‐ three studies had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation and allocation concealment. All studies had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and two were unclear for blinding of outcome assessments. 6 Risk of bias: serious ‐ one study had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation. All studies had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and one had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessments. 7 Risk of bias: serious ‐ 13 studies had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation and 14 for allocation concealment. Fifteen studies had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and one had a high risk of bias. Three studies two had a high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessments and eight were unclear. One study had a high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data, and in three it was unclear. 8 Risk of bias: serious ‐ one study had an unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment. Both studies had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and outcome assessments. 9 Inconsistency: very serious ‐ there was high heterogeneity for this outcome and data were not pooled. 10 Indirectness: serious ‐ we wanted to collect binary data for this outcome, however, only a proxy scale measure was available. 11 One study found no difference in general functioning on the GAS, the other study found a difference in favour of supportive therapy on the GAF. 12 Risk of bias: serious ‐ the study had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and outcome assessors. 13 Imprecision: very serious ‐ relatively few participants were included and few events; confidence intervals are very wide. 14 Risk of bias: serious ‐ the study had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and outcome assessments.

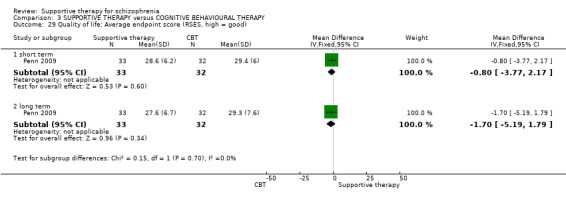

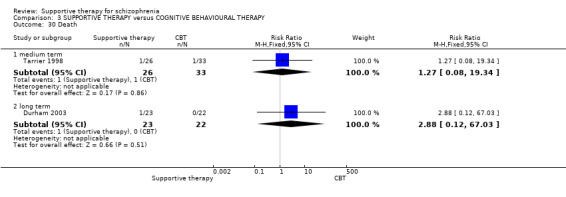

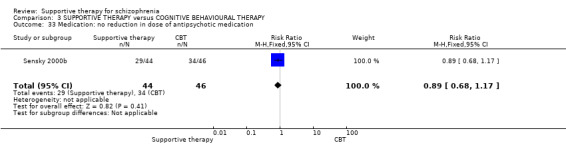

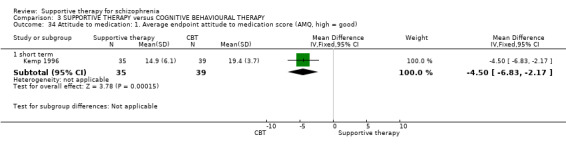

Summary of findings 3. SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY for schizophrenia.

| SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY for schizophrenia | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia

Settings: inpatients and outpatients

Intervention: SUPPORTIVE THERAPY Comparison: COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY | |||||

| Global state: Relapse Follow‐up: 2 to 3 years | 429 per 1000 | 471 per 1000 (219 to 1000) | RR 1.1 (0.51 to 2.41) | 181 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 | |

| Service outcomes: Hospitalisation Follow‐up: 12 weeks to 18 months | 156 per 1000 | 249 per 1000 (132 to 468) | RR 1.6 (0.85 to 3) | 153 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,5 | |

| Mental state: No clinically important improvement Follow‐up: 1 to 2 years | 594 per 1000 | 731 per 1000 (529 to 1000) | RR 1.23 (0.89 to 1.70) | 194 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,6 | |

| Leaving the study early Follow‐up: 10 weeks to 3 years | 150 per 1000 | 158 per 1000 (116 to 217) | RR 1.05 (0.77 to 1.44) | 812 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate7 | |

| General functioning GAF and GAS | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 78 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,8,9,10 | There was very high heterogeneity for this outcome so data were not pooled. 11 |

| Satisfaction with treatment: Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment Follow‐up: 1 years | 136 per 1000 | 435 per 1000 (138 to 1000) | RR 3.19 (1.01 to 10.07) | 45 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,12,13 | |

| Quality of life RSES Follow‐up: 12 weeks | The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 1.7 lower (5.19 lower to 1.79 higher) | 65 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,10 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: serious ‐ three trials had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation and allocation concealment. All studies had an unclear risk for blinding of participants, while two studies were rated as high risk for blinding of outcome assessors. 2 Inconsistency: serious ‐ there was high heterogeneity for this outcome. 3 Imprecision: serious ‐ relatively few participants were included and few events; confidence intervals are wide. 4 Publication bias: strongly suspected ‐ four studies or fewer reported data for this outcome. 5 Risk of bias: serious ‐ one study had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation and two for allocation concealment. All were unclear risk for blinding of participants and two for blinding of outcome assessors. 6 Risk of bias: serious ‐ one study had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation. All three had an unclear risk of blinding of participants and one for blinding of outcome assessors. 7 Risk of bias: serious ‐ seven studies had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation and allocation concealment. Nine studies had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants. Two studies two had a high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessments and four were unclear. 8 Risk of bias: serious ‐ one study had an unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment. Both studies had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and outcome assessments. 9 Inconsistency: very serious ‐ there was high heterogeneity for this outcome and data were not pooled. 10 Indirectness: serious ‐ we wanted to collect binary data for this outcome, however, only a proxy scale measure was available. 11 One study found no difference in general functioning on the GAS, the other study found a difference in favour of supportive therapy on the GAF. 12 Risk of bias: serious ‐ the study had an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and outcome assessors. 13 Imprecision: very serious ‐ relatively few participants were included and few events; confidence intervals are very wide.

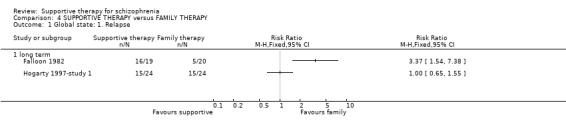

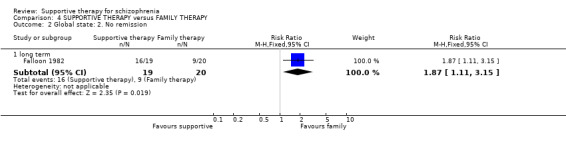

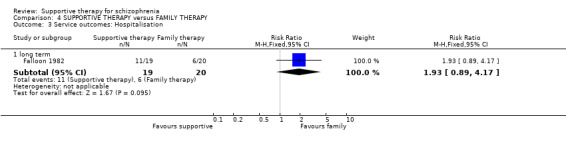

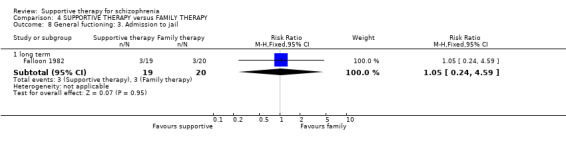

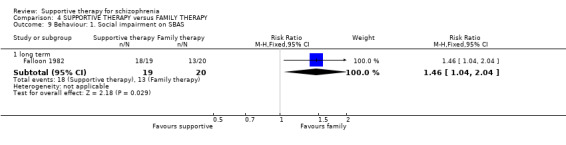

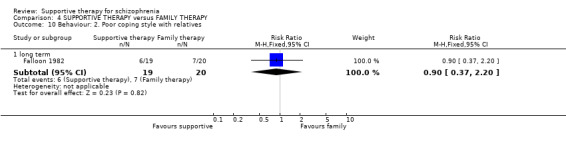

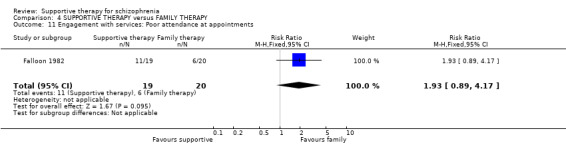

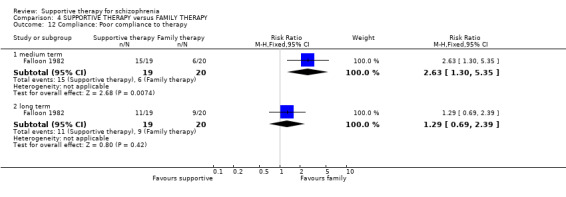

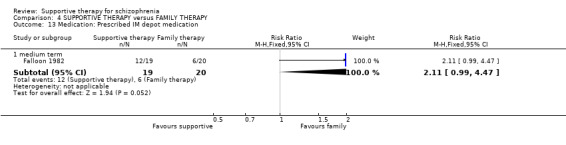

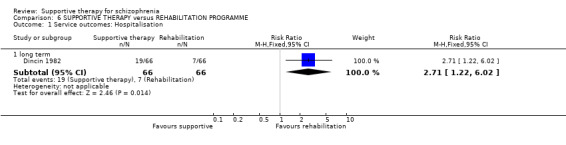

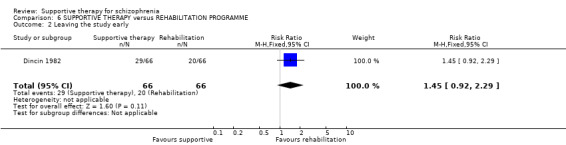

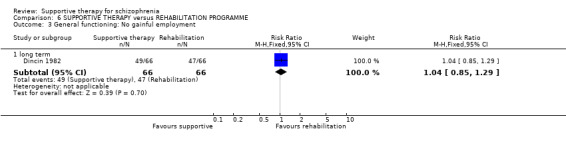

Summary of findings 4. SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus FAMILY THERAPY for schizophrenia.

| SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus FAMILY THERAPY for schizophrenia | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia

Settings: inpatients and outpatients

Intervention: SUPPORTIVE THERAPY Comparison: FAMILY THERAPY | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus FAMILY THERAPY | |||||

| Global state: Relapse Follow‐up: 2 to 3 years | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 87 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 | There was high heterogeneity for this outcome and data were not pooled.5 |

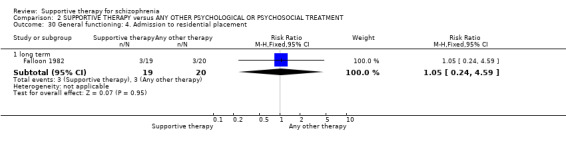

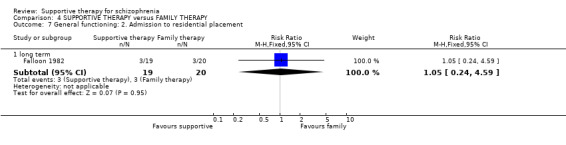

| Service outcomes: Hospitalisation Follow‐up: 2 years | 300 per 1000 | 579 per 1000 (267 to 1000) | RR 1.93 (0.89 to 4.17) | 39 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,6 | |

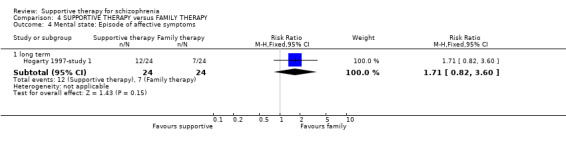

| Mental state: Episode of affective symptoms | 292 per 1000 | 499 per 1000 (239 to 1000) | RR 1.71 (0.82 to 3.6) | 48 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,7,8 | |

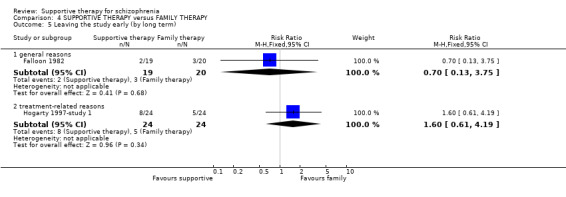

| Leaving the study early | 182 per 1000 | 231 per 1000 (102 to 525) | RR 1.27 (0.56 to 2.89) | 87 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,4 | |

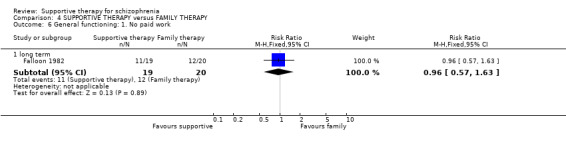

| General functioning: No paid work | 600 per 1000 | 576 per 1000 (342 to 978) | RR 0.96 (0.57 to 1.63) | 39 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,6,9 | |

| Satisfaction with treatment ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported data for satisfaction with treatment. |

| Quality of life ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported data for quality of life. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: very serious ‐ both studies had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding of participants. One study was rated high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessors. 2 Inconsistency: very serious ‐ there was high heterogeneity for this outcome and data were not pooled. 3 Imprecision: serious ‐ relatively few participants were included and few events; confidence intervals are wide. 4 Publication bias: strongly suspected ‐ two studies or fewer reported data for this outcome. 5 One study found no difference in relapse rates, the other study found a difference in favour of family therapy. 6 Risk of bias: serious ‐ the study had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding of participants. 7 Risk of bias: very serious ‐ the study had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding of participants. It was rated high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessors. 8 Indirectness: serious ‐ we wanted to collect binary data for no clinical improvement in general symptoms, however, only a proxy measure was available. 9 Indirectness: serious ‐ we wanted to collect binary data for no overall improvement in general functioning, however, only a proxy measure was available.

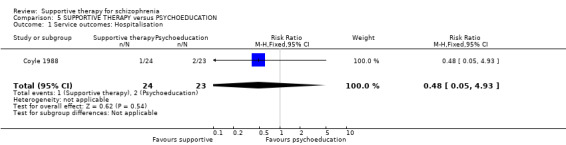

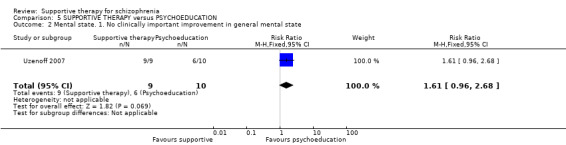

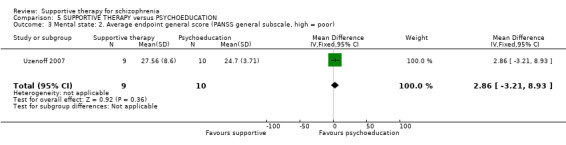

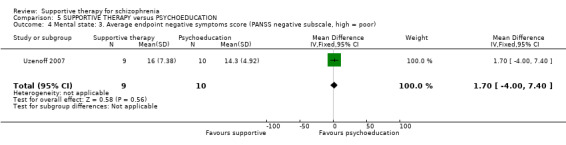

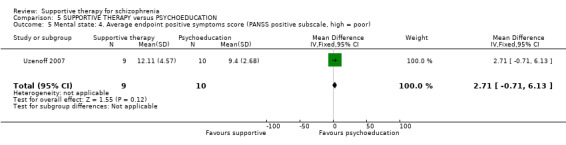

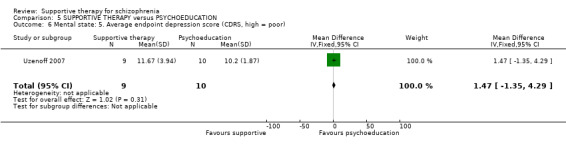

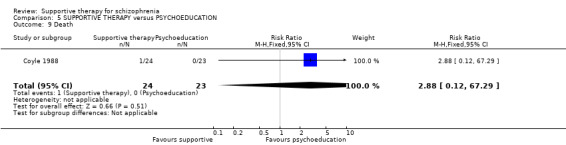

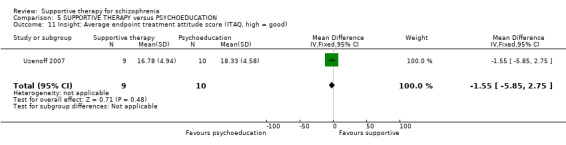

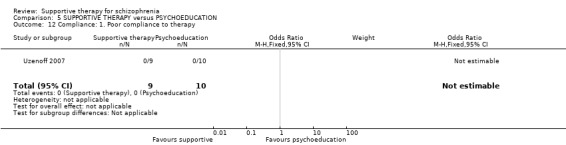

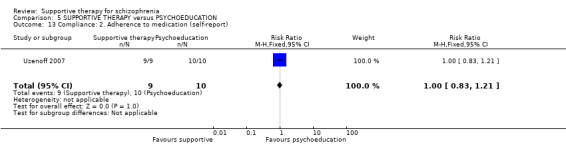

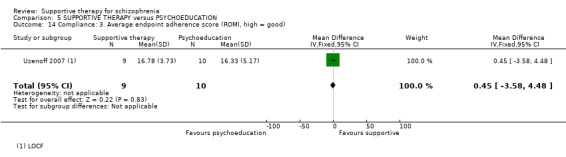

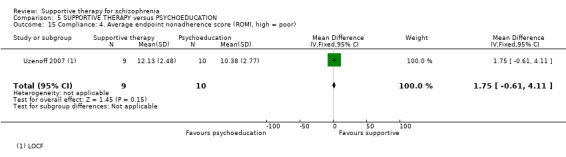

Summary of findings 5. SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus PSYCHOEDUCATION for schizophrenia.

| SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus PSYCHOEDUCATION for schizophrenia | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia

Settings: inpatients and outpatients

Intervention: SUPPORTIVE THERAPY Comparison: PSYCHOEDUCATION | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SUPPORTIVE THERAPY versus PSYCHOEDUCATION | |||||

| Global state: Relapse ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported data on relapse. |

| Service outcomes: Hospitalisation Follow‐up: 6 months | 87 per 1000 | 42 per 1000 (4 to 429) | RR 0.48 (0.05 to 4.93) | 47 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| Mental state. No clinically important improvement Follow‐up: 6 months | 600 per 1000 | 966 per 1000 (576 to 1000) | RR 1.61 (0.96 to 2.68) | 19 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | |

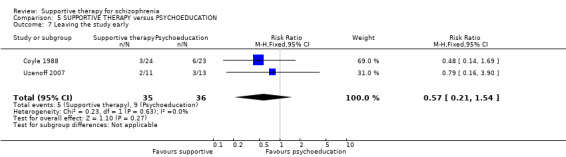

| Leaving the study early Follow‐up: 6 months | 250 per 1000 | 142 per 1000 (52 to 385) | RR 0.57 (0.21 to 1.54) | 71 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,5 | |

| General functioning ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported data for general functioning. |

| Satisfaction with treatment ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported data for satisfaction with treatment. |

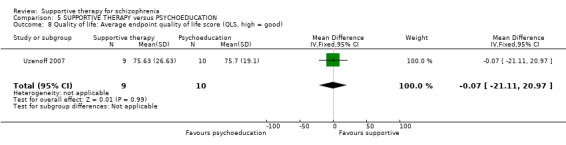

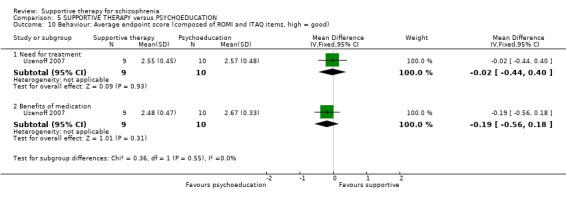

| Quality of life QLS | The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 0.07 lower (21.11 lower to 20.97 higher) | 19 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4,6 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: serious ‐ the study had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding of participants and outcome assessors. 2 Imprecision: very serious ‐ relatively few participants were included and few events; confidence intervals are wide. 3 Publication bias: strongly suspected ‐ two studies or fewer reported data for this outcome. 4 Risk of bias: serious ‐ the study had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding of participants. 5 Risk of bias: serious ‐ both studies had an unclear risk of bias for randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding of participants and one study was unclear risk for outcome assessors. 6 Indirectness: serious ‐ we wanted to collect binary data for this outcome, however, only a proxy scale measure was available.

Background

Description of the condition

One of the common features of psychotherapies and professional interventions for people with schizophrenia is to provide support. For example, in an out‐patient consultation there will often be time allocated to listening to patients' concerns, giving encouragement, or even arranging basic help with day to day living, such as access to local resources. The key elements of support are to maintain an existing situation, or assist pre‐existing coping abilities. Supportive therapy has been described as the treatment model of choice for most patients (Hellerstein 1994), and may be the most commonly practiced intervention in the mental health service.

Description of the intervention

It is, however, difficult to answer the question of exactly what is supportive therapy? A starting point is to look at the literature on supportive psychotherapy, which has been defined as "a dyadic treatment characterised by the use of direct measures to ameliorate symptoms and to maintain, restore or improve self esteem, adaptive skills and ego function" (Pinsker 1991). There may also be a difference in the practice of supportive therapy according to country (Holmes 1995). In the UK, supportive therapy implies a frequency of less than once a week, whereas in America, some practitioners would regard any psychodynamic intervention at a frequency of less than four or five times a week as supportive psychotherapy (Werman 1994).

How the intervention might work

Even though there is no internationally agreed definition, one of the key features is that supportive therapy aims to enhance, rather than challenge, current psychological defence mechanisms. An alternative view is to identify supportive therapy according to the components of the therapy (Misch 2000). For example, one expert proposes seven distinct components; reassurance, explanation, guidance, suggestion, encouragement, affecting change in the environment, and permission for catharsis (Bloch 1996). Bloch also argues that supportive therapy must be a long‐term intervention. The difficulty of this proposal is that there is no clear reason why a specific component of therapy should be regarded as supportive. Possible solutions include defining supportive therapy according to outcome, according to the perception of the client or by identifying a feature of therapy that is inherently supportive, regardless of its impact on a client (Barber 2001).

There are many other forms of support that can be given which are distinct from the psychodynamic tradition. For example, there are mental health workers who have the job title of support worker whose role is often to provide practical support such as reminders and transport for other services, or to spend time befriending a client.

Why it is important to do this review

Ultimately, the lack of a widely accepted definition of supportive therapy means we are not able to avoid an arbitrary element in the definition used for this review. Our definition (see Types of interventions) is influenced by the potential usefulness of this review, which could be:

to give information on the effectiveness of a therapy that is commonly used as the control arm of clinical trials for psychotherapies in schizophrenia;

to help clinicians with the decision of whether to offer a supportive intervention;

to help clinicians understand the value of supportive elements of their individual interactions with people who have schizophrenia.

Objectives

To review the effects of supportive therapy compared with standard care, or other treatments in addition to standard care for people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We sought all relevant randomised controlled trials. Where a trial was described as 'double‐blind', but it was only implied that the study was randomised, we included these trials in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see 'Types of outcome measures') when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then we included them in the final analyses. If there was a substantive difference, then we only used clearly randomised trials and the results of the sensitivity analysis were described in the text. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

We included people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like illnesses using any criteria. We included trials where it was implied that the majority of participants had a severe mental illness that was likely to be schizophrenia. We did not exclude trials due to age, nationality, gender, duration of illness or treatment setting.

Types of interventions

1. Supportive therapy and supportive care

We have used the phrase 'supportive therapy and supportive care' here to indicate that this review covers a wider variety of interventions than supportive psychotherapy alone. However, for the sake of simplicity, we used the term 'supportive therapy' elsewhere in this review. These interventions are provided by a single person with the main purpose of maintaining current functioning or assisting pre‐existing coping abilities in people who have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like illness. The therapies can be aimed at individuals or groups of people. If the content of the therapy was not sufficiently clear after reading a clinical study, then we included any therapy that had supportive or support in its title. We have included advocacy as a form of supportive therapy. Advocacy is a narrower intervention than other interventions included in the review, but it nevertheless fits our definition as it assists people with their communication and interaction with mental health workers.

A number of common therapies are excluded as they are designed to teach new skills or change pre‐existing skills. These include cognitive behavioural therapy(CBT) (Cormac 2004), social skills training, psycho‐education (Pekkala2002), compliance therapy (McIntosh 2006) and problem‐solving therapy.

Some therapies or schemes have been excluded as they involve a team approach rather than an individual worker, or because they are designed to alter a person's environment, rather than to help the person cope with their environment. These include family placement (Pharoah 2006), supported employment and supported accommodation (Chilvers 2006) . An exception was to include an intervention if it was clear that it consisted of a practitioner whose main purpose was to help a client cope with their current situation, rather than alter the situation to make it easier for the client. We have also excluded counselling (unlike the meta‐analysis from the National Institute of Clinical Excellence on supportive therapy (NICE 2003)). The main purpose of counselling is to give an opportunity for a client to explore, discover and clarify ways of living (DoH 2001). Counselling employs a wide variety of techniques, and the purpose may be to facilitate a change in someone's life rather than to maintain the current situation. As counselling has such a broad scope, an exception was to include a clinical trial if there was a clear indication that the main purpose of counselling was to provide support rather than facilitate change or give an opportunity to explore personal issues.

2. Standard care

This is defined as the care a person would normally receive had they not been included in the research trial. This would include interventions such as medication, hospitalisation, community psychiatric nursing input and/or day hospital.

3. Other treatments

This would include any other treatment (biological, psychological or social) such as medication, problem‐solving therapy, psycho‐education, social skills training, CBT, family therapy or psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Types of outcome measures

We reported outcomes for the short term (up to 12 weeks), medium term (13 to 26 weeks), and long term (more than 26 weeks)

Primary outcomes

1. Global state

1.1 Relapse

2. Service outcomes

2.1 Hospitalisation

5. General functioning

5.1 No clinically important change in general functioning

Secondary outcomes

1. Global state

1.2 Time to relapse 1.3 No clinically important change in global state 1.4 Not any change in global state 1.5 Average endpoint global state score 1.6 Average change in global state scores

2. Service outcomes

2.2 Time to hospitalisation

3. Mental state

3.1 No clinically important improvement 3.2 Not any change in general mental state 3.3 Average endpoint general mental state score 3.4 Average change in general mental state scores 3.5 No clinically important change in specific symptoms 3.6 Not any change in specific symptoms 3.7 Average endpoint specific symptom score 3.8 Average change in specific symptom scores

4. Leaving the study early

4.1 For specific reasons 4.2 For general reasons

5. General functioning

5.2 Not any change in general functioning 5.3 Average endpoint general functioning score 5.4 Average change in general functioning scores 5.5 No clinically important change in specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills 5.6 Not any change in specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills 5.7 Average endpoint specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills 5.8 Average change in specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills

6. Satisfaction with treatment

6.1 Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment 6.2 Recipient of care average satisfaction score 6.3 Recipient of care average change in satisfaction scores 6.4 Carer not satisfied with treatment 6.5 Carer average satisfaction score 6.6 Carer average change in satisfaction scores

7. Quality of life

7.1 No clinically important change in quality of life 7.2 Not any change in quality of life 7.3 Average endpoint quality of life score 7.4 Average change in quality of life scores 7.5 No clinically important change in specific aspects of quality of life 7.6 Not any change in specific aspects of quality of life 7.7 Average endpoint specific aspects of quality of life 7.8 Average change in specific aspects of quality of life

8. Death ‐ suicide and natural causes

9. Behaviour

9.1 No clinically important change in general behaviour 9.2 Not any change in general behaviour 9.3 Average endpoint general behaviour score 9.4 Average change in general behaviour scores 9.5 No clinically important change in specific aspects of behaviour 9.6 Not any change in specific aspects of behaviour 9.7 Average endpoint specific aspects of behaviour 9.8 Average change in specific aspects of behaviour

10. Adverse effects

10.1 No clinically important general adverse effects 10.2 Not any general adverse effects 10.3 Average endpoint general adverse effect score 10.4 Average change in general adverse effect scores 10.5 No clinically important change in specific adverse effects 10.6 Not any change in specific adverse effects 10.7 Average endpoint specific adverse effects 10.8 Average change in specific adverse effects

11. Engagement with services

11.1 No clinically important engagement 11.2 Not any engagement 11.3 Average endpoint engagement score 11.4 Average change in engagement scores

12. Engagement in structured activities

12.1 No clinically important change in engagement in structured activities 12.2 Not any change in engagement in structured activities 12.3 Average endpoint engagement in structured activities score 12.4 Average change in engagement in structured activities scores 12.5 No clinically important change in specific activities, such as employment, education or attendance at day centres 12.6 Not any change in specific aspects of functioning, such as employment, education or attendance at day centres 12.7 Average endpoint specific aspects of functioning, such as employment, education or attendance at day centres 12.8 Average change in specific aspects of functioning, such as employment, education or attendance at day centres

13. Insight

13.1 Average endpoint insight score 13.2 Average endpoint treatment attitude score 13.3 Average endpoint adherence score

14. Compliance

14.1 Adherence 14.2 Poor Compliance

15. Medication

15.1 Reduction in dose 15.2 Prescribed intramuscular (IM) depot medication

16. Attitude to medication

16.1 Average endpoint attitude to medication score 16.2 Average endpoint need for treatment

17. Economic outcomes

17.1 Average change in total cost of medical and mental health care 17.2 Total indirect and direct costs.

18. 'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADEapproach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008) and used the GRADE profiler to import data from Review Manager (RevMan) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient‐care and decision making. We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Global state: Relapse

Service outcomes: Hospitalisation

Leaving the study early

Mental state: No clinically important change in general mental state

General functioning: No clinically important change in general functioning

Satisfaction with treatment: Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment

Quality of life: No clinically important change in quality of life

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register (28 November 2012)

[((*support* OR *advoc*) in title of REFERENCE) and ((*support* or *individual* or *sociotherapy* or *socioenvir*) in intervention of STUDY)]

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches of relevant journals and conference proceedings. For details of databases searched see Group Module.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected the reference lists of all identified studies, including existing reviews, for relevant citations.

2. Personal contact

If necessary we would have contacted the first author of each relevant study for information on unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this update review authors NM and KSW independently inspected citations from the new electronic search and identified relevant abstracts. NM and KSW also inspected full articles of the abstracts meeting inclusion criteria. CEA carried out the reliability check of all citations from the new electronic search.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

For this update, NM extracted data from included studies. If data were presented only in graphs and figures NM extracted these data whenever possible. If studies were multi‐centre, where possible, NM extracted data relevant to each component centre separately.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: a. the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b. the measuring instrument has not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial.

Ideally, the measuring instrument should either be i. a self‐report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly; if relevant we noted whether or not this is the case in Description of studies.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult to measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. Had we had both change and endpoint data, we would have combined them in the analysis as we used mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Higgins 2011, Chapter 9.4.5.2).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to all data before inclusion:

standard deviations (SDs) and means are reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors;

when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the SD, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution (Altman 1996));

if a scale started from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, (Kay 1986), which can have values from 30 to 210), we modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐S min), where S is the mean score and S min is the minimum score.

Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied. We entered skewed endpoint data from studies of fewer than 200 participants as other data within the data and analyses section rather than into a statistical analysis. Skewed data pose less of a problem when looking at mean if the sample size is large; we entered such endpoint data into syntheses.

When continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not, we entered skewed change data into analyses regardless of size of study.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005; Leucht 2005a). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for supportive therapy.

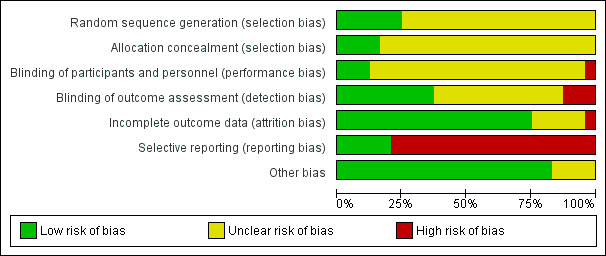

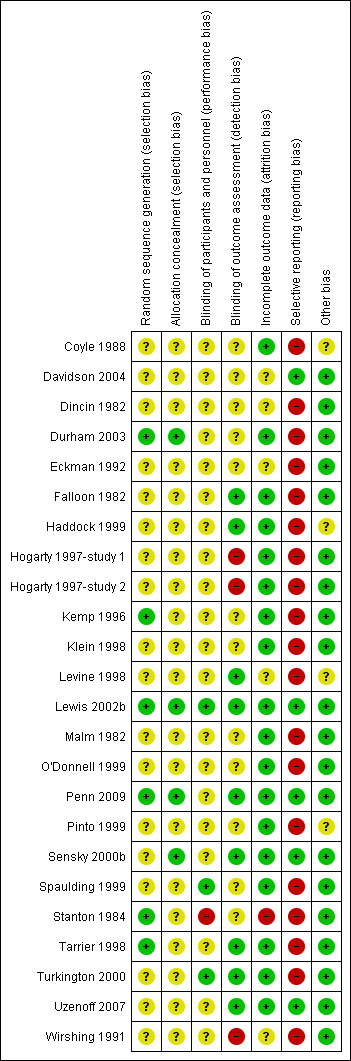

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this update, NM and KSW worked independently by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess trial quality. This new set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain additional information.

We have noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). The Number Needed to Treat/Harm (NNT/H) statistic with its confidence intervals is intuitively attractive to clinicians but is problematic both in its accurate calculation in meta‐analyses and interpretation (Hutton 2009). For binary data presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables, where possible, we calculated illustrative comparative risks.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we estimated mean difference (MD) between groups. We would prefer not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference (SMD)). However, if scales of very considerable similarity had been used, we would have presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and we would have calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

We did not include any cluster‐randomised trials in this version of the review. If we had found trials where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we would have presented data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review, if we include cluster‐randomised trials, we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999).

If we had included trials where clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC is not reported it will be assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would be possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason, cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, had we included such trials, we planned to use only the data of the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involves more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary, we simply added these and combined within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we combined data following the formula in section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not reproduce these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not reproduce these data or use them within analyses. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we addressed this within the 'Summary of findings' tables by down‐rating quality. Finally, we also downgraded quality within the 'Summary of findings' tables where loss was 25% to 50% in total.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis). Those leaving the study early were all assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes, the rate of those who stayed in the study ‐ in that particular arm of the trial ‐ were used for those who did not. We undertook a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when 'completer' data only were compared to the intention‐to‐treat analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome is between 0% and 50% and completer‐only data were reported, we reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations

If standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there are missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals available for group means, and either a P value or T value available for differences in mean, we can calculate them according to the rules described in the Handbook (Higgins 2011): When only the SE is reported, SDs are calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Handbook (Higgins 2011) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, T or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics. If these formulae do not apply, we can calculate the SDs according to a validated imputation method, which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We nevertheless examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leucht 2007). Therefore, where LOCF data have been used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data have been assumed, we reproduced these data and indicated that they are the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations which we had not predicted would arise. When such situations or participant groups arose, we fully discussed these.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. When such methodological outliers arose, we fully discussed these.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 method alongside the Chi2 P value. The I2 provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2). An I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic was interpreted as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). When substantial levels of heterogeneity were found in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). Where the I2 estimate was equal to or greater than 75%, we interpreted this as indicating the presence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). We did not summate data if inconsistency was high, but presented the data separately and investigated reasons for heterogeneity. If data were heterogeneous we used a random‐effects model.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Section 10 of the Handbook (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots are possible, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model: it puts added weight onto small studies which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose the fixed‐effect model for all analyses. The reader is, however, able to choose to inspect the data using the random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses ‐ only primary outcomes

1.1 Clinical state, stage or problem

We proposed to undertake this review and provide an overview of the effects of supportive therapy for people with schizophrenia in general. In addition, however, we tried to report data on subgroups of people in the same clinical state, stage and with similar problems. However, there were not enough included studies in the comparisons to undertake subgroup analyses.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, we have reported this. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, we visually inspected the graph and successively removed outlying studies to see if homogeneity was restored. For this review we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, we would present these data. If not, then we did not pool data and discussed issues. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off, but we use prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity was obvious, we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We do not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

We applied all sensitivity analyses to the primary outcomes of this review.

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way so as to imply randomisation. For the primary outcomes, we included these studies and if there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies were added to those with better description of randomisation, then we entered all data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption/s and when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them, but continued to employ our assumption.

Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing SDs data (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption/s and when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. A sensitivity analysis was undertaken to test how prone results were to change when completer‐only data only were compared to the imputed data using the above assumption. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them, but continued to employ our assumption

3. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that were judged to be at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains of randomisation (implied as randomised with no further details available): allocation concealment, blinding and outcome reporting for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcome. If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then we included data from these trials in the analysis.

4. Imputed values

We planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials if we had used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster‐randomised trials, however, no cluster‐randomised trials were included in this version of the review.

If we noted substantial differences in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we did not pool data from the excluded trials with the other trials contributing to the outcome, but presented them separately.

5. Fixed‐effect and random‐effects

We synthesised data using a fixed‐effect model, unless data were heterogenous, in which case we used a random‐effects model (see Assessment of heterogeneity).

Results

Description of studies

Please see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification, andCharacteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

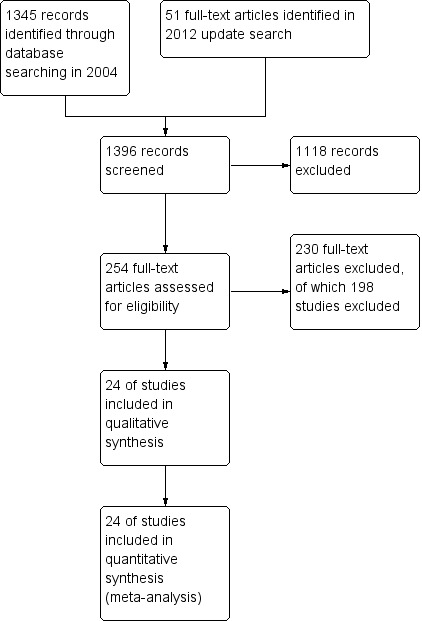

In total, we identified 1396 references from the searches, many of which could be excluded on the basis of their abstracts. We selected 227 references in the previous search and 51 from the update search and obtained full‐text papers for assessment. We included an additional four studies (Davidson 2004; Klein 1998; Penn 2009; Uzenoff 2007); the review now includes 24 studies with 56 references (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

1. Method

Due to the nature of the interventions, none of the 24 included studies were able to use a double‐blind technique. Some (11/24), however, endeavoured to reduce bias by having some or all outcomes rated by people blind to allocation (Durham 2003; Eckman 1992; Haddock 1999; Kemp 1996; Levine 1998; Lewis 2002b; Sensky 2000b; Spaulding 1999; Stanton 1984; Tarrier 1998; Turkington 2000). Two studies attempted to keep therapists blind to the specific study hypothesis (Coyle 1988; Stanton 1984). Some studies reported outcomes immediately after therapy, whilst others reported outcomes after a follow‐up period without therapy.

2. Duration

The overall duration of the trials varied between 10 weeks and three years. Three studies (Levine 1998; Lewis 2002b; Penn 2009) were short term (up to 12 weeks). Five studies (Coyle 1988; Klein 1998; Pinto 1999; Turkington 2000; Uzenoff 2007) were medium term (13 to 26 weeks), and the remaining 16 studies were long term (more than 26 weeks).

3. Participants

Nineteen included studies had less than 100 participants; the range of the number of participants was 12 to 315. A total of 2126 people participated in the 24 trials, most of whom had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Ten studies included only people with schizophrenia, however two of these (Coyle 1988; Malm 1982) did not describe criteria clearly. Sixteen trials included people with other psychotic illnesses (schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder and other psychoses). Of these, one study also included people with bipolar disorder (O'Donnell 1999) and one included severely disturbed psychiatric patients (Dincin 1982). Twenty‐three studies employed operational criteria for diagnoses (DSM‐II, DSM‐III, DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐IV, ICD‐10, RDC, WHO Discrimination Criteria), however, one of these trials Coyle 1988 did not report how the diagnoses were reached. Malm 1982 described the diagnostic criteria used, but these were not recognised operational criteria. Twenty trials included male and female participants, two studies (Eckman 1992; Wirshing 1991) included men only, and the remaining two studies (Levine 1998; Uzenoff 2007) did not report the sex of participants. Ages of participants ranged from 16 to 72 years.

4. Setting

Eleven trials took place in outpatient settings. Three trials were conducted in inpatient settings (Haddock 1999; Spaulding 1999; Stanton 1984), seven were in a mixture of inpatient and outpatient settings (Durham 2003; Lewis 2002b; Malm 1982; O'Donnell 1999; Pinto 1999; Turkington 2000; Wirshing 1991), and the rest did not report on setting.

Thirteen studies were carried out in the USA (Coyle 1988; Davidson 2004; Dincin 1982; Eckman 1992; Falloon 1982; Hogarty 1997‐study 1; Hogarty 1997‐study 2; Klein 1998; Penn 2009; Spaulding 1999; Stanton 1984; Uzenoff 2007; Wirshing 1991); seven in the UK (Durham 2003, Haddock 1999; Kemp 1996; Lewis 2002b; Sensky 2000b; Tarrier 1998; Turkington 2000); one in Australia (O'Donnell 1999); one in Israel (Levine 1998); one in Italy (Pinto 1999); and one in Sweden (Malm 1982).

5. Interventions

5.1 Experimental intervention

All studies used supportive therapy in addition to standard care (including antipsychotic medication). There were variations between studies with regard to frequency and duration of therapy sessions. Most studies used twice‐weekly, weekly and fortnightly sessions, although some studies did not report on the frequency or duration of intervention (Durham 2003; Haddock 1999; O'Donnell 1999; Pinto 1999). The duration of therapy varied between five weeks and three years. Fifteen studies investigated individual treatment, and six studies delivered supportive therapy in a group format (Dincin 1982; Eckman 1992; Levine 1998; Malm 1982; Spaulding 1999; Wirshing 1991). Seven studies reported the use of therapy manuals or protocols (Durham 2003; Hogarty 1997‐study 1; Hogarty 1997‐study 2; Lewis 2002b; Malm 1982; Penn 2009; Spaulding 1999). Eight studies reported that therapists were supervised (Davidson 2004; Haddock 1999; Hogarty 1997‐study 1; Hogarty 1997‐study 2; Lewis 2002b; Malm 1982; Penn 2009; Sensky 2000b), and six that audiotapes of sessions were monitored for quality (Haddock 1999; Lewis 2002b; Penn 2009; Sensky 2000b; Turkington 2000; Uzenoff 2007). Six of the studies reported that the same therapists delivered experimental and control interventions, and three studies reported using different therapists for different therapeutic interventions (Durham 2003; O'Donnell 1999; Stanton 1984). Therapists delivering the supportive intervention were trained in a different therapeutic modality, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or family therapy, in four studies (Haddock 1999; Lewis 2002b; Penn 2009; Sensky 2000b).

5.2 Control intervention

Five studies compared supportive therapy with standard treatment alone (Coyle 1988; Davidson 2004; Durham 2003; Lewis 2002b; Tarrier 1998), the remaining trials used various other psychosocial interventions for comparison. Twelve studies compared supportive therapy with CBT (Durham 2003; Haddock 1999; Hogarty 1997‐study 1; Hogarty 1997‐study 2; Kemp 1996; Levine 1998; Lewis 2002b; Pinto 1999; Sensky 2000b; Spaulding 1999; Tarrier 1998; Turkington 2000). Two studies used family therapy as a comparison (Falloon 1982; Hogarty 1997‐study 1). Skills training was investigated in three studies (Coyle 1988; Eckman 1992; Wirshing 1991); other comparisons were personal therapy plus family therapy (Hogarty 1997‐study 1), psychoeducation (Coyle 1988; Uzenoff 2007), milieu rehabilitation programme (Dincin 1982) and insight‐oriented psychotherapy (Stanton 1984). One study investigated supportive therapy combined with client‐focused case management in comparison with client‐focused case management (O'Donnell 1999). One trial compared supportive therapy with intensive case management in comparison with intensive case management (Klein 1998). Finally, one trial investigated the effect of adding supportive therapy to a combination of social skills training and medication (Malm 1982). Fourteen of the studies attempted to match experimental and control psychosocial interventions for the amount of therapist contact (Eckman 1992; Falloon 1982; Haddock 1999; Kemp 1996; Levine 1998; Lewis 2002b; Penn 2009; Pinto 1999; Sensky 2000b; Spaulding 1999;Tarrier 1998; Turkington 2000; Uzenoff 2007; Wirshing 1991). In contrast, four studies took the approach that different interventions by their nature involve different amounts of therapist contact (Dincin 1982; Hogarty 1997‐study 1; Hogarty 1997‐study 2; Stanton 1984). The other studies did not report on this matter. Davidson 2004 gave all participants a $28 stipend whether they received supportive care or not to control for possible effects of receiving funds to take part in social activities.

6.Outcomes

Listed below are the outcomes for which we could obtain usable data, followed by a summary of data that could not be used in the meta‐analysis.

6.2 Outcome scales

6.2.1 Mental state

i. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay 1987) This scale assesses the severity of psychotic symptomatology in general. It consists of three subscales, positive symptoms, negative symptoms and general psychopathology, and a total score. This scale was used by Durham 2003; Levine 1998; Lewis 2002b; Penn 2009 and Uzenoff 2007.

ii. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Lukoff 1996) This is a semi‐structured interview, which assesses the major psychiatric symptoms. It is a 16‐item scale, and each item is scored on a seven‐point scale, ranging from ’not present’ to ’extremely severe’. The range of possible scores is 24 to 168, and high scores indicate more severe symptoms. Data from the BPRS is reported by Haddock 1999; Kemp 1996; Penn 2009; and Pinto 1999. Kemp 1996 reported data for the full version of the BPRS immediately after treatment. They also used an abridged version of the scale, which contained seven of the 16 items, including psychotic symptoms, negative symptoms and depression. Results for the abridged version were reported immediately after treatment and at six‐month, 12‐month and 18‐month follow‐up.

iii. Schedule for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Andreasen 1983) This scale assesses the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. A six‐point scale is used to rate alogia, affective blunting, avolition‐apathy, anhedonia‐apathy, anhedonia‐asociality and attention impairment. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. This scale was used by Pinto 1999 and Sensky 2000b.

iv. Schedule for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Andreasen 1984) This scale selectively assesses the positive symptoms of psychosis and the higher the score, the more severe the symptoms. Pinto 1999 used this scale.

v. Psychotic Symptoms Rating Scales (PSYRATS) (Haddock 1999b) This consists of two scales, which assess delusional beliefs and auditory hallucinations. There are 11 items in the auditory hallucinations scale, including frequency, duration, level of distress, controllability, loudness, location and beliefs about origin of voices. The delusional beliefs scale has six items, including preoccupation, intensity of distress, conviction and disruption. Each item is rated on a five‐point scale. The PSYRATS were used by Lewis 2002b and Penn 2009.

vi. Belief about Voices Questionnaire‐Revised (BAVQ‐R) (Chadwick 2000) This scale is a 35‐item measure of beliefs about auditory hallucinations and the emotional and behavioural reactions to them. There are five BAVQ‐R subscales: malevolence, benevolence, resistance, engagement, and omnipotence. Each item is rated on a four‐point scale; a higher score indicates more belief in their voices. This scale was used by Penn 2009.

vii. Comprehensive Psychiatric Rating Scale (CPRS) (Montgomery 1978)

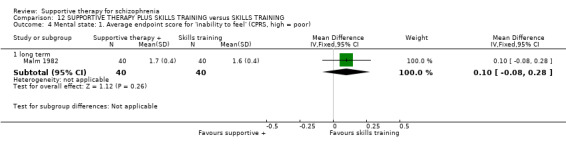

This is a general psychiatric rating scale, which was used by Sensky 2000b and Malm 1982. A high score indicates severe symptoms. Malm 1982 used the schizophrenia subscale, which consists of 45 items and a global rating of degree of illness. The paper reported useable data for only two of the 45 items on this scale.

viii. Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI‐II) (Beck 1996) This scales measures the severity of depression. It has 21 self‐reported items measured on a four point scale. A higher score indicates more severe depression. This scale was used by Penn 2009.

ix. Calgary Depression Rating Scale (CDRS) (Addington 1993) This is a nine‐item structured interview scale developed specifically for assessing depression in individuals with schizophrenia. The CDRS assesses depression as separate from overlapping negative or extrapyramidal symptoms. Higher scores indicate greater depression. This scale was used by Uzenoff 2007.

x. Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale (CES‐D) (Radloff 1977) This is a 20‐item scale to measure depressive symptomology. The possible range of scores is zero to 60 and higher scores indicate more symptoms. This scale was used by Davidson 2004.

xi. Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979) This scale was developed using a 65‐item psychopathology scale to identify the 17 most commonly occurring symptoms in primary depressive illness. The maximum score is 30, and a higher score indicates more severe psychopathology. The scale was used by Sensky 2000b.

6.1.2 General functioning

i. Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) (APA 1987) The GAF disability scale is taken from the DSM‐III‐R (APA 1987). The scale has 10 defined anchor points relating to social competence, and scores range from zero to 100. A higher score indicates better functioning. Durham 2003; Kemp 1996; and Klein 1998 report data from this scale. Davidson 2004 uses the GAF‐M, which is a modified version.

ii. Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (Endicott 1976) This scale provides a rating between zero and 100, which reflects overall degree of psychological or psychiatric health. A high score indicates better health. This scale was used by Durham 2003.

iii. Katz Adjustment Scales (KAS) (Katz 1963) This collection of scales measures social adjustment and behaviour. It was used by Malm 1982. It consists of items which can be grouped into subscales including ’performance of socially expected activities’ (15 items) and ’free‐time activities’ (23 items), the two subscales chosen by Malm 1982. In this study, the items were also grouped into syndromes, entitled ’offensive behaviour’ (two items) and ’withdrawal’ (six items).

iv. Social Functioning Scale (SFS ) (Birchwood 1990) The SFS is a 79‐item self‐report questionnaire to both the patients and the caregiver, about performance in seven areas: Social Engagement (SE), Interpersonal Communication (IC), Recreational Activities (RA), Social Activities (SA), Independence Competence (INC), Independence Performance (IP) and Occupational Activity (OA). The purpose of the scale is to provide an evaluation of strengths and weaknesses of patient functioning, and it may reveal aims for therapeutic intervention.

6.1.3 Behaviour

i. Social Behaviour Adjustment Scale (SBAS) (Platt 1980) Falloon 1982 was the only study to use this scale. Scoring is based on a structured interview with a key informant from the person's family. Areas covered include household tasks, spare time/leisure activity, work/study, decision making, friendliness/affection, everyday conversation, relationships outside the family, behavioural disturbance, social and interpersonal role performance, and adverse effects on the family and other people in the community. Each item is scored on a scale from zero to two, and higher scores indicate greater impairment or dissatisfaction.

6.1.4 Insight

i. Beck Cognitive Insight Scale ‐ (BCIS) composite (Beck 2004) The BCIS is a 15‐item self‐report measure composed of two subscales: self‐reflectiveness and self‐certainty. Penn 2009 used a composite index of insight, computed from the BCIS. Higher scores reflect greater cognitive insight.

ii. Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire (ITAQ) (McEvoy 1989) This scale assesses an individual’s recognition of illness and need for treatment and includes 11 questions. Reponses are rated as follows: 2 = good insight, 1 = partial insight, and 0 = no insight, which are summed to provide a total insight score. Higher scores correspond to better insight. Uzenoff 2007 reported data on this scale.

iii. Schedule for Assessment of Insight (SAI) (David 1990) The schedule is a semi‐structured interview with three components; treatment compliance, awareness of illness and ability to relabel psychotic symptoms correctly. The range of possible scores is zero to 14, but scores are expressed as a percentage of maximum insight. Low scores therefore indicate poor insight. The expanded version of the SAI was used by Kemp 1996.

6.1.5 Compliance