Abstract

Background

Colesevelam is a second‐generation bile acid sequestrant that has effects on both blood glucose and lipid levels. It provides a promising approach to glycaemic and lipid control simultaneously.

Objectives

To assess the effects of colesevelam for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Search methods

Several electronic databases were searched, among these The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2012), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, LILACS, OpenGrey and Proquest Dissertations and Theses database (all up to January 2012), combined with handsearches. No language restriction was used.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared colesevelam with or without other oral hypoglycaemic agents with a placebo or a control intervention with or without oral hypoglycaemic agents.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected the trials and extracted the data. We evaluated risk of bias of trials using the parameters of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding, completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other potential sources of bias.

Main results

Six RCTs ranging from 8 to 26 weeks investigating 1450 participants met the inclusion criteria. Overall, the risk of bias of these trials was unclear or high. All RCTs compared the effects of colesevelam with or without other antidiabetic drug treatments with placebo only (one study) or combined with antidiabetic drug treatments. Colesevelam with add‐on antidiabetic agents demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in fasting blood glucose with a mean difference (MD) of ‐15 mg/dL (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐22 to ‐ 8), P < 0.0001; 1075 participants, 4 trials, no trial with low risk of bias in all domains. There was also a reduction in glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in favour of colesevelam (MD ‐0.5% (95% CI ‐0.6 to ‐0.4), P < 0.00001; 1315 participants, 5 trials, no trial with low risk of bias in all domains. However, the single trial comparing colesevelam to placebo only (33 participants) did not reveal a statistically significant difference between the two arms ‐ in fact, in both arms HbA1c increased. Colesevelam with add‐on antidiabetic agents demonstrated a statistical significant reduction in low‐density lipoprotein (LDL)‐cholesterol with a MD of ‐13 mg/dL (95% CI ‐17 to ‐ 9), P < 0.00001; 886 participants, 4 trials, no trial with low risk of bias in all domains. Non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes were infrequently observed. No other serious adverse effects were reported. There was no documentation of complications of the disease, morbidity, mortality, health‐related quality of life and costs.

Authors' conclusions

Colesevelam added on to antidiabetic agents showed significant effects on glycaemic control. However, there is a limited number of studies with the different colesevelam/antidiabetic agent combinations. More information on the benefit‐risk ratio of colesevelam treatment is necessary to assess the long‐term effects, particularly in the management of cardiovascular risks as well as the reduction in micro‐ and macrovascular complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, long‐term data on health‐related quality of life and all‐cause mortality also need to be investigated.

Keywords: Humans; Allylamine; Allylamine/analogs & derivatives; Allylamine/therapeutic use; Blood Glucose; Blood Glucose/metabolism; Colesevelam Hydrochloride; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/blood; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/drug therapy; Fasting; Fasting/blood; Glycated Hemoglobin; Glycated Hemoglobin/metabolism; Hypoglycemic Agents; Hypoglycemic Agents/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Colesevelam for type 2 diabetes mellitus

Colesevelam was originally approved for the treatment of hyperlipidaemia (high blood lipids) in the 2000s but has been shown to improve blood sugar as well. Therefore, we investigated its role in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A total of 1450 patients took part in six studies investigating colesevelam. These studies lasted 8 to 26 weeks. Only one small study compared colesevelam directly to placebo, the other five studies investigated a combination of colesevelam with other antidiabetic agents versus a combination of placebo with other antidiabetic agents. There were no two studies with the same intervention and comparison group. When added to other antidiabetic agents colesevelam showed improvements in the control of blood glucose and blood lipids. However, it is difficult to disentangle the effects of colesevelam from the other antidiabetic agents used because only one study compared colesevelam to placebo. The same is true for adverse effects: three studies reported on just a few non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes, no other serious side effects were observed. No study investigated mortality; complications of type 2 diabetes such as eye disease, kidney disease, heart attack and stroke; health‐related quality of life; functional outcomes and costs of treatment. Therefore, long‐term data on the efficacy and safety of colesevelam are necessary.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Colesevelam for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

| Colesevelam compared for type 2 diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus Settings: outpatient Intervention: colesevelam (± antidiabetic agents) Comparison: placebo (± antidiabetic agents) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Morbidity | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated | ||

| Mortality | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated | ||

| Health‐related quality of life | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated | ||

| Functional outcomes | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated | ||

| Costs | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated | ||

| Adverse events (all adverse events) | RR 1.06 (0.97 to 1.15) | 1450 (6) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |||

| HbA1c change from baseline to end point (%) (follow‐up 12 to 26 weeks) | The mean HbA1c change ranged across control groups from ‐0.8% to 0.2% | The mean HbA1c change in the intervention groups was 0.4% to 0.6% lower | MD ‐0.5% (‐0.6 to ‐0.4) |

1315 (5) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

| CI: confidence interval; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin A1c; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 There was insufficient information on the process of randomisation and incomplete data reporting. 2 There were no two trials with the same intervention and comparison group.

Background

Description of the condition

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder resulting from a defect in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. A consequence of this is chronic hyperglycaemia (that is, elevated levels of plasma glucose) with disturbances of carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism. Long‐term complications of diabetes mellitus include retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy and the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is increased. For a detailed overview of diabetes mellitus, please see under 'Additional information' in the information on the Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group in The Cochrane Library (see 'About', 'Cochrane Review Groups (CRGs)'). For an explanation of methodological terms, see the main glossary in The Cochrane Library.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is pandemic globally (IDF 2009). The Asia‐Pacific region will face the most challenges of this disease burden (Chan 2009). More than half of the world's population live here ranging from the richest and most developed countries to the poorest and least‐developed ones. There is a predisposition to disproportionate effects on the lower socioeconomic groups as well as middle‐aged and older adults (Agardh 2011). In addition, with the poor quality of blood glucose and the associated risk factors control is far from satisfactory (Chan 2009; Cheung 2009; Kolding 2006; Yang 2012). Taken together with the confluence of the recent upsurge of obesity and an ageing population, this will have a far‐reaching negative impact on income security, social welfare and medical services (Bruno 2011; Dall 2010; Pan 2010), particularly of the low‐ and middle‐income developing countries in the Asia‐Pacific region (Abegunde 2007; Tharkar 2010; Zhang 2010).

CVD is strikingly common, affecting almost 50% of the population with T2DM (Bays 2007; Chan 2009; Lloyd‐Jones 2010; NIDDKD 2011), and carries significant morbidity, disability, dependency and mortality (Kalyani 2010). Dyslipidaemia together with hypertension and hyperglycaemia are established risk factors for CVD among the patients with T2DM and are clearly modifiable. Targeting glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels alone is not correlated to reduced CVD events (Gerstein 2008; Patel 2008). However, managing multiple risk factors (hyperglycaemia, hypertension and dyslipidaemia) concurrently leads to a 50% reduction of CVD risk (Colhoun 2004; Gaede 2003; Mehler 2003). Nevertheless, the proportion of those achieving optimal controls in all these three important treatment goals of glycaemic control, hypertension and dyslipidaemia simultaneously, remained disappointing.

Controlling this disease is important for reducing complications, improving health‐related quality of life and reducing the economic burden associated with public health burden of disability and dependency (Kalyani 2010; UKPDS 1999). Therefore, a therapeutic agent that reduces both hyperglycaemia and dyslipidaemia simultaneously warrants further exploration.

Description of the intervention

Colesevelam is a specifically designed second‐generation bile acids (BAs) sequestrant for more selective and high‐capacity BA‐binding (Bays 2003). The non‐absorbable polymer along with the hydrophilic and water‐insoluble nature further facilitates binding upon BAs in the intestine and formation of a non‐absorbable complex for elimination in the faeces (Rosenbaum 1997). Colesevelam was originally approved for the treatment of hyperlipidaemia in 2002 (NCEP 2002). Clinical studies of colesevelam monotherapy demonstrated a lowering of low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) levels from 15% to 19%. When combing with another lipid‐lowering agent, LDL‐C levels were further reduced between 42% to 48% (Davidson 1999; Insull 2001; Rosenson 2006).

Evolving clinical trials also demonstrated improvement of glycaemic control in patients with T2DM (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Zieve 2007). These findings further provided the basis for the approval of colesevelam by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008 as an adjunct therapy for glycaemic control in adults with T2DM.

Adverse effects of the intervention

Compared to its predecessors, the unique polymer structure of this orally administered drug allows for greater tolerability, fewer adverse effects and fewer potential drug interactions (Hanus 2006). Nonetheless, adverse effects are reported to include gastrointestinal (GI) and metabolic effects. Dysphagia, oesophageal obstruction and constipating effects may be aggravated in patients with GI motility disorders (Bays 2008; Davidson 1999; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008). Although hypoglycaemia was reported, the incidence was low and only mild to moderate symptoms were observed (Goldfine 2010). In addition, animal studies suggested a significant carcinogenic risk of colesevelam on the pancreas and thyroid when given 20 and 40 times above normal doses (EMEA 2005).

Concomitant administration of colesevelam with glibenclamide and L‐thyroxine significantly decreases the bioavailability of the latter drugs (Brown 2010). However, this decrease can be avoided if the mentioned drugs are given four hours before colesevelam. There is also a potential decrease of absorption of drugs with narrow therapeutic index, such as phenytoin, as well as fat‐soluble vitamins (Jacobson 2007; Schmidt 2010).

How the intervention might work

Although colesevelam has a favourable effect on glycaemic parameters, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Proposed mechanisms include reduction in glucose absorption following binding to the colesevelam molecule and BAs leading to changes in the time course of glucose absorption in the GI tract (Staels 2009). Alternatively, the resulting drug‐BA complex may modulate the enterohepatic pathway of bile metabolism or the farnesoid X receptor (Claudel 2005; Herrema 2010; Staels 2009).

The mechanisms of action for lipid control are better understood compared to those of glycaemic control. Binding of colesevelam with BAs in the intestine impedes the re‐absorption of BAs. The result is a reduction in LDL‐C ranging from 10% at 2.3 g/day to 13% at 3.8 g/day with a threefold increase in faecal BA excretion (Donovan 2005). Accompanying very low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL‐C) production may increase triglyceride levels, but high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C) is generally unaffected or slightly increased (Insull 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

Colesevelam differs from other antidiabetic drugs in that it reduces both glucose level and LDL‐C through the BA pathways and not the classical interactions among the triumvirate of impaired β‐cell function leading to diminished insulin secretion, increased hepatic glucose production and peripheral insulin resistance (DeFronzo 1987; Houten 2006). The majority of the current armamentarium of established pharmacological agents for T2DM have only a glucocentric focus.

The goals for diabetes mellitus reach from glycaemic control to the reduction of all risk factors associated with microvascular and macrovascular disease complications. Apart from education and lifestyle modification (nutrition, weight reduction, exercise and smoking cessation), pharmacological agents are important components of effective treatment of T2DM. However, balancing the multiple goals of ideal T2DM care with the realities of patient adherence, expectations and socioeconomic circumstances are major challenges.

Understanding of the efficacy of colesevelam in the context of T2DM management would have potential implications for the treatment of the disease. Currently, there is still no comprehensive health technology assessment review on colesevelam for T2DM. Previous reviews on the use of colesevelam in clinical trials were focused on the lipid=lowering properties and did not specifically examine the issues in T2DM. One systematic review of colesevelam for T2DM focused on only three clinical trials, even though there were others available (Fonseca 2010). The aim of this review is to identify, examine and assemble comprehensive quality evidence on colesevelam for management of T2DM.

Objectives

To assess the effects of colesevelam on type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled clinical trials.

Types of participants

All adults of 18 years or above of either gender who had T2DM based on the diagnostic criteria below were included. The level of LDL‐C in T2DM that warrants addition of an antihyperlipidaemic pharmacological agent was based on the recommended criteria below.

We excluded individuals with normal fasting blood glucose (FBG) and postprandial glucose levels as well as concomitant endocrinopathy affecting their blood glucose levels.

Diagnostic criteria

Diabetes mellitus

To be consistent with changes in classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus through the years, the diagnosis should be established using the standard criteria valid at the time of the beginning of the trial (e.g. ADA 1999; ADA 2008; WHO 1998). Ideally, diagnostic criteria should have been described. If necessary, we used authors' definition of diabetes mellitus. We planned to subject diagnostic criteria to a sensitivity analysis.

Hypercholesterolaemia

The initiation of a pharmacological agent for treatment of hypercholesterolaemia was based on the recommendations of the American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association and the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III). This defined hypercholesterolaemia as a blood LDL‐C concentration of 3.36 mmol/L or greater (≥ 130 mg/dL) (ADA 2011; Grundy 2004). If the recommended criteria were not described, we used authors' definition of hypercholesterolaemia. In such instances, we also planned to subject the recommended criteria to a sensitivity analysis.

Types of interventions

|

Comparison intervention Intervention |

Placebo | Placebo with any antihyperglycaemic agent other than colesevelam | Placebo with any antihyperlipidaemic agent other than colesevelam | Placebo with any antihyperglycaemic, antihyperlipidaemic agent other than colesevelam or both |

| Colesevelam | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Colesevelam with another antihyperlipidaemic agent | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Colesevelam with another antihyperglycaemic agent | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Colesevelam with another antihyperglycaemic and antihyperlipidaemic agent | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Glycaemic control (measured by HbA1c and glucose levels (fasting and postprandial)).

Morbidity (both T2DM‐related morbidities and cardiovascular‐related co‐morbidities; all‐cause morbidity).

Adverse effects of colesevelam (all expected and unexpected serious and non‐serious adverse events (e.g. hypoglycaemia, gastrointestinal motility effects (especially constipation)). Classification of hypoglycaemic events was as defined by clinical trial protocols.

Secondary outcomes

Mortality (all‐cause and diabetes‐related, including death from vascular disease, renal disease and hypoglycaemia).

Changes in blood‐lipid profile (including total cholesterol, LDL‐C, HDL‐C, triglycerides).

Obesity measures: body weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, waist to hip‐ratio or total body fat.

Changes in blood insulin, C‐peptide levels or insulin resistance.

Functional outcomes (both physical and cognitive functions).

Health‐related quality of life or well‐being.

Costs.

Timing of outcome measurement

The outcomes of FBG and two‐hour postprandial glucose levels require trials of at least six weeks and over to yield meaningful results. Trials with HbA1c need to be over three months. Other outcomes (such as morbidity) were assessed in the short term (12 to less than 18 weeks), medium term (18 weeks to one year) and long term (more than one year).

'Summary of findings' table

We planned to establish a 'Summary of findings' table using the following outcomes listed according to priority:

morbidity;

mortality;

serious adverse events;

health‐related quality of life;

glycaemic control;

lipid control.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The following sources were used for the identification of trials:

The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2012);

MEDLINE (from inception to January 2012);

EMBASE (from inception to January 2012);

CINAHL (from inception to January 2012);

OpenGrey (from inception to January 2012);

LILACS (from inception to January 2012).

Theses:

Proquest Dissertations and Theses database (from inception to January 2012).

We also searched databases of ongoing trials (www.controlled‐trials.com/ with links to several databases and www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/). We planned to provide information including trial identifier about recognised studies in the section 'Outcomes' in the Characteristics of included studies table.

For detailed search strategies see under Appendix 1 (searches were not older than six months at the moment the final review draft was checked into the Cochrane Information and Management System for editorial approval).

No additional key words of relevance were detected during any of the electronic or other searches. Thus, the electronic search strategies were not modified. Studies published in any language were included.

We sent the results of electronic searches to the Editorial Base of the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group for confirmation.

Searching other resources

We also searched the US FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) websites for additional relevant information. The manufacturer of colesevelam was contacted for information of unpublished trials. In addition, we tried to identify additional studies by searching the reference lists of included trials and (systematic) reviews, meta‐analyses and health technology assessment reports. Content experts were contacted for further additional information, additional references, unpublished data and updated results of ongoing interventions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

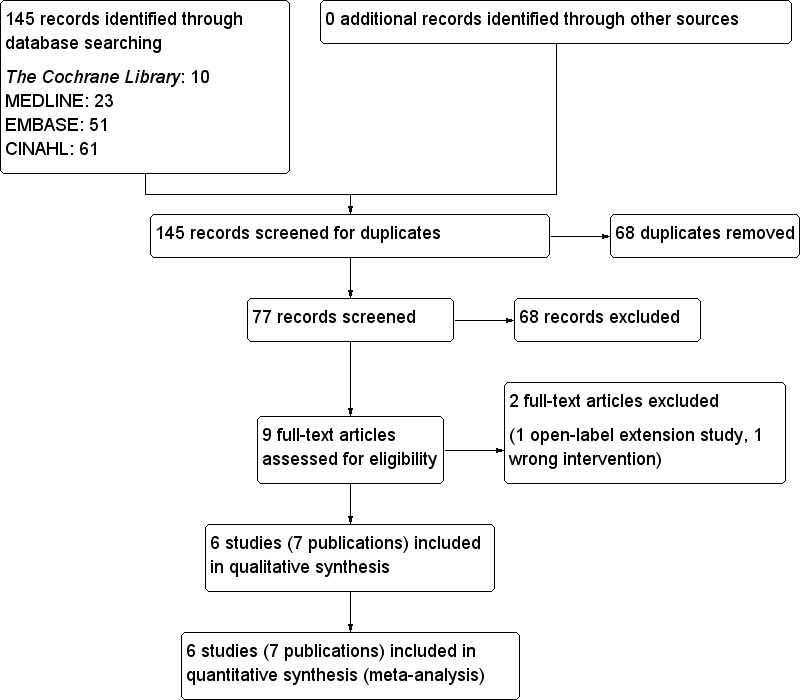

To determine the studies to be assessed further, two review authors (CPO, SCL) independently scanned the abstract, title or both sections of every record retrieved. All potentially relevant articles were investigated as full text. We selected six studies for this review. Where differences in opinion existed, they were resolved by a third party. If resolving disagreement was not possible, the article was added to those 'awaiting assessment' and authors were contacted for clarification. This is summarised in the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses) flow‐chart (Figure 1) of study selection (Liberati 2009).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

For studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, two review authors (CPO, SCL) independently extracted relevant population and intervention characteristics using standard data extraction templates (for details see Characteristics of included studies; Table 2; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion, or when required by a third party. We attempted to contact the study authors for relevant details on the trials. The results of this survey are displayed in Appendix 8.

1. Overview of study populations.

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) and control(s) | [n] screened | [n] randomised | [n] safety | [n] ITT | [n] finishing study | [%] of randomised participants finishing study |

| Bays 2008 | I1: colesevelam + (metformin only or metformin + oadm) C1: placebo + (metformin only or metformin + oadm) |

T: 1009 | I1: 159 C1: 157 T: 316 |

I1: 159 C1: 157 T: 316 |

I1: 149 C1: 152 T: 301 |

I1: 116 C1: 106 T: 222 |

I1: 73 C1: 68 T: 70 |

| Fonseca 2008 | I1: colesevelam + (sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas + oadm) C1: placebo + (sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas + oadm) |

T: 1180 | I1: 230 C1: 231 T: 461 |

I1: 230 C1: 231 T: 461 |

I1: 219 C1: 218 T: 437 |

I1: 166 C1: 141 T: 307 |

I1: 72 C1: 61 T: 67 |

| Goldberg 2008 | I1: colesevelam + (insulin only or insulin + oadm) C1: placebo + (insulin only or insulin + oadm) |

T: 785 | I1: 147 C1: 140 T: 287 |

I1: 147 C1: 140 T: 287 |

I1: 144 C1: 136 T: 280 |

I1: 117 C1: 114 T: 231 |

I1: 80 C1: 81 T: 80 |

| Rosenstock 2010 | I1: colesevelam + metformin C1: placebo + metformin |

T: 1668 | I1: 145 C1: 141 T: 286 |

I1: 145 C1: 141 T: 286 |

I1: 138 C1: 137 T: 275 |

I1: 124 C1: 120 T: 244 |

I1: 86 C1: 85 T: 85 |

| Schwartz 2010 | I1: colesevelam C1: placebo |

T: 66 | I1: 17 C1: 18 T: 35 |

I1: 17 C1: 18 T: 35 |

‐ | I1: 16 C1: 17 T: 33 |

I1: 94 C1: 94 T: 94 |

| Zieve 2007 | I1: colesevelam + oadm C1: placebo + oadm |

T: 234 | I1: 31 C1: 34 T: 65 |

I1: 31 C1: 34 T: 65 |

I1: 31 C1: 34 T: 65 |

I1: 27 C1: 32 T: 59 |

I1: 87 C1: 94 T: 91 |

| Total | All interventions | 729 | 566 | ||||

| All controls | 721 | 530 | |||||

| All interventions and controls | 1450 | 1096 |

"‐" denotes not reported

C: control; I: intervention; ITT: intention to treat; oadm: oral antidiabetic medications; T: total

Dealing with duplicate publications

In the case of duplicate publications and companion papers of a primary study (Zieve 2007), we maximised the yield of information by simultaneous evaluation of all available data. Zieve 2007 was included as it contained the best usable data for this review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CPO, SCL) assessed each trial independently. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, or with consultation of a third party.

We assessed the risk of bias using The Cochrane Collaboration's tool (Higgins 2011). We used the following bias criteria:

random sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding (performance bias and detection bias), separated for blinding of participants and personnel and blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

selective reporting (reporting bias);

other bias.

We judged the risk of bias criteria as 'low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk' and used the individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We attached a 'Risk of bias graph' figure and 'Risk of bias summary' figure. We assessed the impact of individual bias domains on study results at end point and study levels. The main summary assessments were incorporated into judgements about the 'quality of evidence' in the 'Summary of findings' table, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Data of the main summary assessments were imported into the GradePro software to facilitate the process of creating the 'Summary of findings' table (Brozek 2008).

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data was expressed as odds ratio (OR) or risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous data was expressed as differences in means (MD) with 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

We took into account the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over trials, cluster‐randomised trials and multiple observations for the same outcome.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to obtain relevant missing data from authors, if feasible and carefully performed evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT), as‐treated and per‐protocol (PP) populations. We also investigated attrition rates (e.g. drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals) and critically appraised issues of missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last observation carried forward (LOCF)).

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the event of substantial clinical or methodological or statistical heterogeneity we did not report study results as meta‐analytically pooled effect estimates. We identified heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots and by using a standard Chi2 test with a significance level of α = 0.1, in view of the low power of this test. We specifically examined heterogeneity employing the I2 statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across studies to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003), where an I2 statistic of 75% or more indicated a considerable level of inconsistency (Higgins 2011).

When heterogeneity was found, we attempted to determine potential reasons for it by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

We expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity:

age;

duration of T2DM;

presence of complications of diabetes at baseline;

baseline HbA1c levels;

baseline blood lipid level;

compliance with treatment (including medical and nutritional management);

presence of co‐medications (e.g. other antidiabetic agents and antihyperlipidaemic medications).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use funnel plots if we included 10 studies or more for a given outcome to assess small study bias. There are a number of explanations for the asymmetry of a funnel plot (Sterne 2001) and we planned to interpret results carefully (Lau 2006).

Data synthesis

We primarily summarised low‐risk of bias data by means of a random‐effects model. We performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines referenced in the newest version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out subgroup analyses if any one of the primary outcome parameters (see above) demonstrated statistically significant differences between intervention groups to investigate interactions.

We planned the following subgroup analyses:

age;

gender;

patients with and without co‐morbidities (e.g. ischaemic heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease);

patients with and without co‐medications (e.g. antihypertensive drugs, statins, aspirin).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size:

restricting the analysis to published studies;

restricting the analysis taking account risk of bias, as specified above;

restricting the analysis to very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results;

restricting the analysis to studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), country.

We also tested the robustness of the results by repeating the analysis using different measures of effect size (RR, OR, etc.) and different statistical models (fixed‐effect model and random‐effects model).

Results

Description of studies

For details see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies. There is no study awaiting classification.

Results of the search

The initial electronic searches identified 145 articles (Figure 1). No additional record was identified through other sources as well as no unpublished study was found. We removed 68 duplicates. On reading the titles and abstracts of the remaining 77 records, we excluded another 68 of these articles because they were not related to the review question, were reviews or non‐clinical studies.

A total of nine publications describing randomised controlled clinical trials were selected for further assessment (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Goldfine 2010; Kondo 2010; Rosenstock 2010; Schwartz 2010; Zieve 2007). Two publications (Zieve 2007) were analyses from the same trial. One of them was published as 'letter to the editor' and sub‐analysed the lipoprotein subclasses in patients with T2DM and HbA1c levels between 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) and 10.0% (86 mmol/mol). The other publication was a pilot study evaluating the effects of colesevelam hydrochloride on glycaemic control in patients with T2DM (Zieve 2007). Zieve 2007 was selected as the primary reference for this review as it contained data relevant to the review question. Goldfine 2010 was an analysis of the extended study period of the three double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase III studies (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008). Those patients who were on placebo from the three phase III studies were given colesevelam. Therefore, this analysis was not an original randomised controlled trial. Two studies (Goldfine 2010; Kondo 2010) were excluded, and details are shown in Characteristics of excluded studies. All the trials were published in the English language.

Included studies

For full details, please note the table Characteristics of included studies.

We included six trials in this review (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Rosenstock 2010; Schwartz 2010; Zieve 2007). The details of these trials are summarised in Characteristics of included studies and in Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6 and Appendix 7. There were five multicentre trials (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Rosenstock 2010; Zieve 2007). These centres were in the US, Mexico, Colombia and India. The number of centres ranged from 15 to 56. Only the trial of Schwartz 2010 was of single‐centre setting in the US. However, none of the trials reported the clinical settings in which the studies were performed. Colesevelam was supplied by the same manufacturer in all the trials.

The following is the summary of the interventions and controls found in the selected RCTs.

|

Comparison intervention Intervention |

Placebo | Placebo with any antihyperglycaemic agent other than colesevelam | Placebo with any antihyperlipidaemic agent other than colesevelam | Placebo with any antihyperglycaemic, antihyperlipidaemic agent other than colesevelam or both |

| Colesevelam | Schwartz 2010 | No | No | No |

| Colesevelam with another antihyperlipidaemic agent | No | No | No | No |

| Colesevelam with another antihyperglycaemic agent | No | Zieve 2007 | No | No |

| Colesevelam with another antihyperglycaemic, antihyperlipidaemic agent or both | No | No | No | Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Rosenstock 2010 |

Only one trial compared colesevelam with placebo (Schwartz 2010), while colesevelam or placebo was combined with other hypoglycaemic agents in the remaining five trials (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Rosenstock 2010; Zieve 2007).

Baseline characteristics

All the trials reported participation of both males and females. There was no significant difference in gender distribution between the intervention and control arms. All patients received general dietary advice. There was no information on the duration of diabetes in five trials (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Schwartz 2010; Zieve 2007). For the trial of Rosenstock 2010, there was no significant difference in the duration of T2DM among patients in the intervention and control groups. None of the publications reported any relevant baseline data on co‐morbidities.

Participants

A total of 1450 patients with T2DM took part in the six trials ranging from 35 to 461 patients per trial. There were 729 participants in the colesevelam intervention groups and 721 participants in the control groups. These patients came from multi‐ethnic backgrounds including: white people, African‐Americans, Asians, Hispanics and others. Their mean ages were all above 50 years.

Diagnostic criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and medications

All trial participants had T2DM. Criteria for diagnosis in four trials were based on the authors' definitions (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Schwartz 2010). The American Diabetes Association criteria were used for diagnosis in the other two trials (Rosenstock 2010; Zieve 2007). In all the trials, the patients had inadequate glycaemic control. The inadequacies of glycaemic control as measured by the HbA1c ranged from 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) to 10% (86 mmol/mol) in five trials (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Schwartz 2010; Zieve 2007) and HbA1c 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) to 10.0% (86 mmol/mol) in the remaining trial (Schwartz 2010). Most exclusion criteria consisted of significant obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) and diseases such as GI and cardiovascular disorders.

Co‐medications

Only one trial investigated drug‐naive patients (Rosenstock 2010). However, all the patients were given open‐label metformin on entry to the trial. The other studies included patients on antidiabetic agents (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Schwartz 2010; Zieve 2007). These agents were metformin monotherapy or metformin in combination with other oral antidiabetic drugs (Bays 2008); sulphonylureas alone or in combination with other oral antidiabetic agents (Fonseca 2008); insulin alone or in combination with oral antidiabetic agents (Goldberg 2008); diet or antidiabetic agents (Schwartz 2010); and sulphonylurea alone, metformin alone or sulphonylurea plus metformin (Zieve 2007). In contrast, in the study of Schwartz 2010, those who met the inclusion criteria at screening were withdrawn from all antidiabetic medications until the end of the trial. Four trials reported the concurrent use of antihypertensives (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Schwartz 2010). Other lipid‐altering drugs such as 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG‐CoA) reductase inhibitors and fibrates were also concomitantly used by patients (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Rosenstock 2010).

Treatment before study

Although there were recommendations to follow the appropriate diet, there was no specific, protocol‐directed dietary evaluation or dietary recommendations (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Rosenstock 2010). There was no reporting of dietary regimens in two other studies (Schwartz 2010; Zieve 2007). No exercise regimen was documented in all the trials. Four studies reported a placebo run‐in period after screening, whereby the patients took six colesevelam‐matching placebo tablets daily in addition to their antidiabetic medications (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Zieve 2007). In the study of Schwartz 2010, there was a wash‐out period of three days and two weeks for insulin and oral antidiabetic agents, respectively. Rosenstock 2010 did not report any pre‐treatment regimens.

Interventions

Similar colesevelam hydrochloride tablets (625 mg tablet) and dosing (3.75 g/day) were used for the interventions in all the trials. These tablets were supplied by the same manufacturer. However, the duration of the trials and the complementing management of the disease differed. The duration of treatment ranged from 8 to 26 weeks. There were no complementing antidiabetic agents and dietary recommendations in the trial of Schwartz 2010, which lasted eight weeks. The intervention was added to the existing antidiabetic regimen for 12 weeks in the trial of Zieve 2007. Both the trials of Goldberg 2008 and Rosenstock 2010 were completed in 16 weeks. The intervention was added to the existing antidiabetic and dietary regimen in Goldberg 2008. In contrast, the patients in Rosenstock 2010 were not receiving any antidiabetic treatment. Finally, both the trials of Bays 2008 and Fonseca 2008 of 26 weeks' duration, had the intervention added to the existing antidiabetic and dietary regimens.

One trial directly compared colesevelam to placebo as monotherapy (Schwartz 2010). For the other five trials, the control interventions were both placebos and combination therapies (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008; Rosenstock 2010; Zieve 2007). The placebo consisted of magnesium stearate and microcrystalline cellulose, with a commercially supplied film‐coating mixture in two trials (Bays 2008; Goldberg 2008). No information was provided for the content of the placebos in the rest of the trials (Fonseca 2008; Rosenstock 2010; Schwartz 2010; Zieve 2007).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

For details on outcome data see Appendix 2 and Appendix 5.

All included trials reported glycaemic control. Glycaemic control was defined as change in HbA1c from baseline to end of the treatment period in all studies except Schwartz 2010. Change from baseline in glucose disposal rate during the final 30 min of the insulin clamp (M‐value) to week eight was used in this study.

Secondary outcomes, additional/other outcomes

Secondary outcomes in these studies consisted mainly of mean changes of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and lipids from baseline, for the intervals during follow‐up periods as well as to end of the treatment period. Mean changes of HbA1c from baseline and for the intervals during the follow‐up periods were also included in three trials (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008). Mean changes in fructosamine as well as changes in postprandial blood glucose, insulin, proinsulin, measurements of beta‐cell function, such as homeostasis model assessment index (HOMA‐I) and using the hyperinsulinaemic‐euglycaemic clamp technique to measure the quantitative insulin sensitivity were also included in some studies. One study also used standard meal tolerance tests (MTTs) which were used to analyse plasma glucose, insulin, area‐under‐the‐curve (AUC) insulin, C‐peptide AUC and insulin AUC‐to‐glucose AUC ratio (Schwartz 2010).

Safety outcomes mainly comprised treatment‐emergent adverse events, vital signs, findings of physical examinations, electrocardiograms (ECG) and body weight. Adverse events reported were usually mild and included hypoglycaemia, constipation, dyspepsia and nausea. Laboratory measurements were composed of routine or standard haematology, serum chemistry and urinalysis. No trial reported outcomes on morbidity, functional outcomes, health‐related quality of life, well‐being and costs.

Excluded studies

Two studies (Goldfine 2010; Kondo 2010) were excluded (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

For details on study populations such as numbers randomised, analysed, ITT and safety population see Table 2.

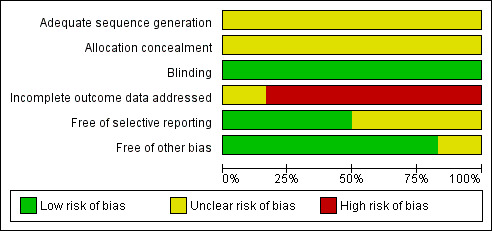

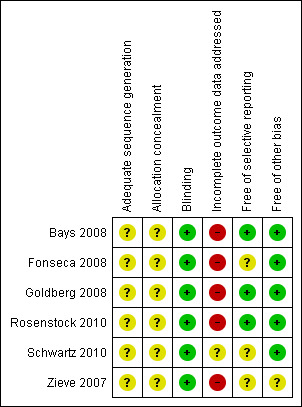

Overall, the publications suggested unclear risk of bias, predominantly in the selection bias domain within and across studies (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). These studies generally had a parallel group randomised controlled, double‐blind design, typically employing an ITT analysis. Although blinding of outcome assessors was not described, it was not likely to affect clinical laboratory parameters. There was complete inter‐rater agreement for the key quality indicators randomisation, concealment of allocation and blinding. Therefore, no discussion with a third party was necessary.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All trials did not report adequately on randomisation and allocation concealment.

Blinding

Although all trials were described as double‐blinded, none reported on the double‐blinding procedure.

Incomplete outcome data

All publications reported an ITT analysis, and the majority used the LOCF method to impute missing values. Zieve 2007 did not describe any method for handling missing values. Justifications for withdrawals from the trials were reported in all the publications. Although missing data were addressed using the LOCF approach, LOCF procedures can lead to serious bias of effect estimates. In addition, there were 6% to 39% of the patients withdrawn from the respective trials at various stages adding to attrition bias. In particular, the attrition rate in Fonseca 2008 was high and disproportionate. Therefore, data from these publications are at high or unclear risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

All the publications indicated low risk of reporting bias except for Zieve 2007 where the risk was unclear.

Other potential sources of bias

Generally, the risk for other biases was low.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Baseline characteristics

Although all six trials used the similar proprietary colesevelam of the same dose, this drug was combined with a series of different antihyperglycaemic agents. No two trials used the same colesevelam and antihyperglycaemic agent combination.

All six trials reported outcomes, including FBG, HbA1c, total cholesterol and subclasses as well as adverse effects. However, no two trials reported similar comparisons (see Appendix 5 for details).

Primary outcomes

For details on primary and secondary outcome data see Data and analyses.

Metabolic control

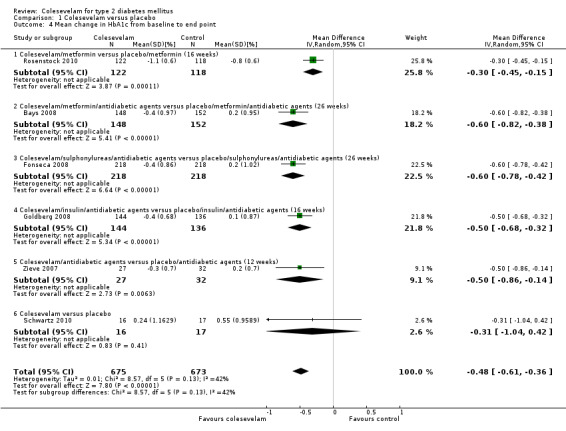

The general effect of addition of colesevelam to other hypoglycaemic agents showed a reduction in HbA1c in favour of colesevelam (MD ‐0.5% (95% CI ‐0.6 to ‐0.4), P < 0.00001; 1348 participants, 6 trials, no trial with low risk of bias in all domains; Analysis 1.4). However, the single trial comparing colesevelam to placebo only did not reveal a statistical significant difference between the two arms ‐ in fact, in both arms HbA1c increased.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colesevelam versus placebo, Outcome 4 Mean change in HbA1c from baseline to end point.

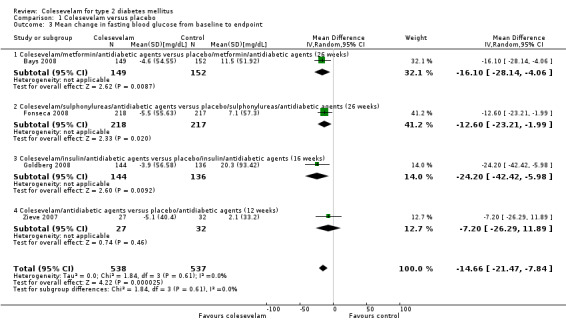

Colesevelam with add‐on hypoglycaemic agents demonstrated a statistical significant reduction in FBG with a mean difference (MD) of ‐15 mg/dL (95% CI ‐22 to ‐ 8), P < 0.0001; 1075 participants, 4 trials, no trial with low risk of bias in all domains; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colesevelam versus placebo, Outcome 3 Mean change in fasting blood glucose from baseline to endpoint.

Colesevelam plus metformin monotherapy with or without other antidiabetic agents versus placebo plus metformin with or without oral antidiabetic agents

The trial of Bays 2008 combined colesevelam with metformin only or metformin with other oral antidiabetic drugs. For FBG, the MD between the study arms was ‐16 mg/dL (95% CI ‐28 to ‐4, 301 participants, P < 0.01; Analysis 1.3) in favour of the colesevelam intervention. Similarly, the mean HbA1c difference was also significant (MD ‐0.6% (95% CI ‐0.8 to ‐0.4, 300 participants, P < 0.0001; Analysis 1.4) in favour of the colesevelam intervention.

Colesevelam plus sulphonylurea monotherapy or sulphonylurea plus oral antidiabetic agents versus placebo plus sulphonylurea monotherapy or sulphonylurea plus oral antidiabetic agents

The trial of Fonseca 2008 compared colesevelam and placebo with combinations of other oral antidiabetic agents. There were significant MDs for both FPG and HbA1c in favour of the colesevelam intervention arms. These were ‐13 mg/dL (95% CI ‐23 to ‐2, 435 participants, P < 0.05; Analysis 1.3) and ‐0.6% (95% CI ‐0.8 to ‐0.4, 461 participants, P < 0.00001; Analysis 1.4) for FBG and HbA1c, respectively.

Colesevelam plus insulin monotherapy or insulin plus oral antidiabetic agents versus placebo plus insulin monotherapy or insulin plus oral antidiabetic agents

Colesevelam and placebo were combined with antidiabetic agents in the trial of Goldberg 2008. Significant MDs were found for both FPG and HbA1c in favour of the colesevelam intervention arms. These were ‐24 mg/dL (95% CI ‐42 to ‐6, 280 participants, P < 0.05; Analysis 1.3) and ‐0.5% (95% CI ‐0.7 to ‐0.3, 280 participants, P < 0.00001; Analysis 1.4) for FBG and HbA1c, respectively.

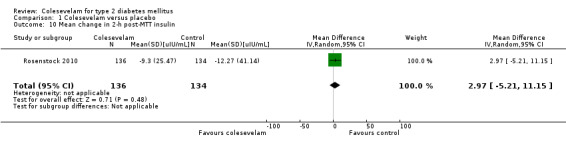

Colesevelam plus metformin versus placebo plus metformin

When comparing metformin plus placebo with colesevelam plus metformin, the latter combination showed more benefit for HbA1c (MD ‐0.3% (95% CI ‐0.5 to ‐0.2, 240 participants, P < 0.0001) Analysis 1.4 (Rosenstock 2010). However, there was no significant treatment difference for FBG at 16 weeks last observation carried forward (LOCF) (treatment difference ‐6.0 (95% CI ‐13.0 to 0.0, 275 participants, P < 0.2370)).

Colesevelam versus placebo

Although the results of Schwartz 2010 indicated benefits with colesevelam in lowering the FBG, there were no raw data available for further analysis. However, the authors reported no statistically significant change in mean HbA1c (+0.2% (from 8.2 to 8.5; P = 0.422)) with colesevelam compared with significant changes of +0.6% (from 8.7 to 9.3; P = 0.031) with placebo, from week zero to week eight LOCF.

Colesevelam plus antidiabetic agents versus placebo plus antidiabetic agents

The trial of Zieve 2007 combined colesevelam with other oral antidiabetic drugs. For FBG, the MD between the study arms was ‐7 mg/dL (95% CI ‐26 to ‐12, 59 participants, P >0.05; Analysis 1.3) which was not significant. However, the mean HbA1c difference was significant, ‐0.5% (95% CI ‐0.9 to ‐0.1, 59 participants, P < 0.006; Analysis 1.4) in favour of the colesevelam intervention.

Morbidity

There were no publications reporting data on morbidity outcomes.

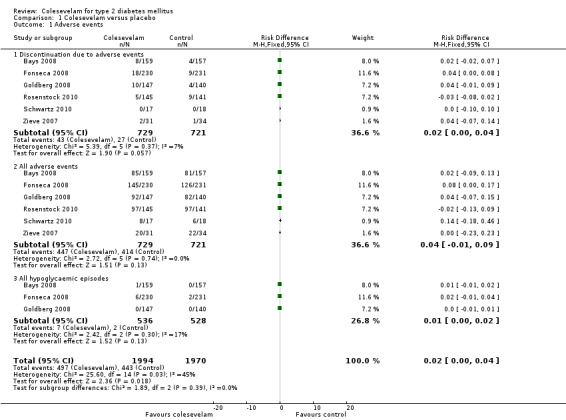

Adverse events

For details of adverse events see Appendix 6 and Appendix 7.

Adverse events were reported in all the trials and presented in both the intervention and control groups. Most of these reported events were predominantly mild to moderate GI symptoms such as constipation and dyspepsia. Discontinuation owing to adverse effects did not differ significantly between colesevelam only or colesevelam and other antidiabetic intervention and control arms (RR 1.57 (95% CI 0.89 to 2.75), P = 0.12; 1450 participants, 6 trials; Analysis 1.1). The RRs of adverse events also did not show statistically significant differences between groups.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colesevelam versus placebo, Outcome 1 Adverse events.

Only three trials reported mild hypoglycaemic episodes (Bays 2008; Fonseca 2008; Goldberg 2008).There was no severe or nocturnal hypoglycaemia reported in all these trials.

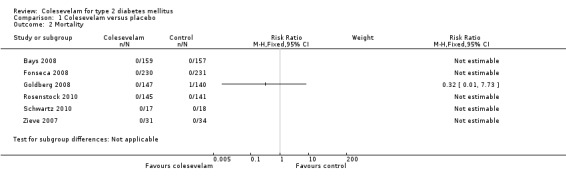

Secondary outcomes

Mortality

There were no publications reporting data on mortality outcomes.

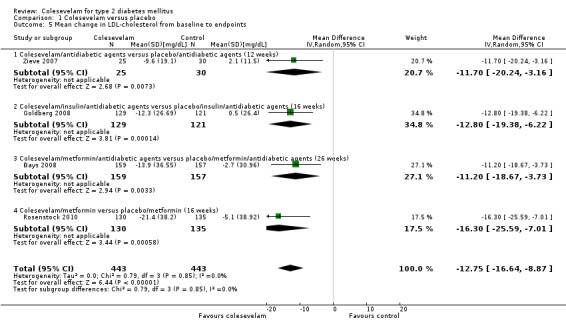

Lipid profile

For details of LDL‐C see Analysis 1.5

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colesevelam versus placebo, Outcome 5 Mean change in LDL‐cholesterol from baseline to endpoints.

Colesevelam with add‐on hypoglycaemic agents demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in LDL‐C with an MD of ‐13 mg/dL (95% CI ‐17 to ‐ 9), P < 0.00001; 886 participants, 4 trials, no trial with low risk of bias in all domains; Analysis 1.5.

The trials of Goldberg 2008 and Fonseca 2008 reported a significant reduction in triglyceride levels. However, there were no raw data available from the Fonseca 2008 trial for detailed analysis. Nevertheless, secondary data for LDL‐C, non‐HDL‐C, triglycerides, Apo‐A1 and Apo‐B suggested statistically significant changes favouring colesevelam combination with other oral antidiabetic agents.

Obesity measures

There were no publications reporting data on changes in body weight, BMI, waist circumference, waist‐to‐hip ratio or total body fat.

Changes in blood insulin, C‐peptide levels or insulin resistance

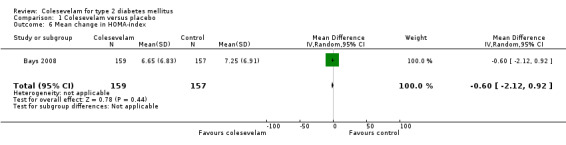

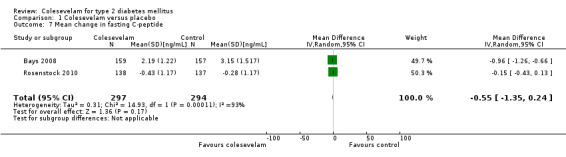

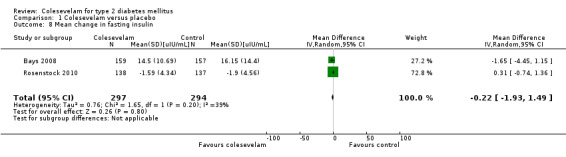

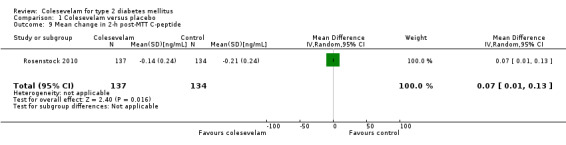

There were three publications reporting changes in these parameters (Bays 2008; Rosenstock 2010; Schwartz 2010). Rosenstock 2010 reported both fasting and two‐hour post‐MTT C‐peptide as well as fasting and two‐hour post‐MTT insulin. There were no statistical significant changes in these parameters between the intervention and control arms. Colesevelam plus metformin with or without other oral antidiabetic agents versus placebo plus metformin with or without other antidiabetic agents did not demonstrate any statistical significant mean changes in the levels of fasting C‐peptide, fasting insulin and homeostasis model assessment index (HOMA‐I) (Bays 2008). Finally, there were no suitable data available in the study of Schwartz 2010 for detailed analysis. However, the authors reported statistically significant increases in whole body insulin sensitivity in the colesevelam intervention arm compared with the placebo arm.

Functional outcomes

There were no publications reporting data on functional outcomes.

Health‐related quality of life

There were no publications reporting data on health‐related quality of life.

Costs

There were no publications reporting data on health economics.

Subgroup analyses

This was not performed owing to lack of data.

Sensitivity analyses

We did not perform sensitivity analyses owing to the different comparisons of intervention and control groups of included studies and insufficient data.

Publication and small study bias

Drawing of funnel plot was not possible owing to insufficient data.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Six studies investigating the treatment of T2DM with colesevelam that met our inclusion criteria were included in this review. A total of 1450 patients with T2DM was randomised to interventions with colesevelam or combinations of colesevelam with other antidiabetic agents. Colesevelam‐antidiabetic agents combination therapy resulted in statistically significant reductions in HbA1c compared with the placebo‐antidiabetic agents combination therapy in five trials. Significant changes in FBG favouring colesevelam combination therapies as well as significant reductions of LDL‐C were also observed. However, no single trial investigated the same intervention and comparison group. Therefore, data on comparisons with active comparators to confirm these findings were limited. Due to the limited number of trials on colesevelam monotherapy or colesevelam combination therapy for T2DM, subgroup and sensitivity analyses were not possible.

Caution is needed when interpreting these findings. The effect estimates were small. The relatively small sample size in each of the colesevelam or colesevelam combination trials contributed to the low power of the studies. Further, there were no data published on mortality, diabetic complications, functional outcomes, costs of treatment and health‐related quality of life.

Generally, colesevelam appeared to provide dual benefits of glycaemic control and lowering of LDL‐C. Apart from the predominant adverse GI effects, this drug was well tolerated, with no severe hypoglycaemia. So far, in all published randomised controlled trials of colesevelam interventions, only routine adverse effects of symptoms, clinical laboratory measurements and compliance have been reported. Further, there is still no report of pancreatic and thyroid carcinoma in humans despite the theoretical risk demonstrated in animal models (EMEA 2005).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All the six trials selected for this review used similar proprietary colesevelam pharmacological agents in the interventions. Detailed information of the placebos used in the control groups was reported in only two of the six trials (Bays 2008; Goldberg 2008). Further, the time points for assessment of the effects of interventions for the six trials differed. These time points ranged from eight to 26 weeks. No data on outcomes were available beyond 26 weeks. There were also not enough data of similar time points that could be extracted from these publications.

Quality of the evidence

All the six trials had unclear risk of biases in at least two domains. These domains were selection bias, performance bias and reporting bias. There was insufficient information on appropriate randomisation as well as blinding methods and how incomplete outcome data were addressed. Even though the pre‐specified outcomes that were objectively measured are less susceptible to detection and reporting biases, the significant number of drop‐outs and the use of LOCF approach may further impound on these estimates. These sources of bias need to be considered when interpreting the results. Further, the small sample size and number of events in each trial are affected by greater sampling variation. This is reflected in the large CI effect estimates. Taken together, these factors contributed to low quality of evidence.

Potential biases in the review process

There are several limitations in interpretation with this systematic review. First, there are limited trials on colesevelam and the varied colesevelam combinations published. Further, all these published trials had findings of beneficial effects of colesevelam on glycaemic control. Besides possible publication bias, all the included trials have other methodological issues. Potential biases may occur during selection of patients, administration of treatment and the significant number of drop‐outs affecting the assessment of outcomes. Therefore, inadequacy in the process of randomisation and blinding may be associated with exaggerated effects of the interventions due to systematic errors (bias). Moreover, methodologically fewer rigorous trials have shown significantly larger intervention effects than trials with more rigour (Egger 2003; Kjaergard 2001; Moher 1998; Schulz 1995).

Second, the small sample size of the trials leading to diminished power of the results may explain the small effect estimates between the interventions and placebo. In other words, the analyses from the size of these trials may not establish with confidence that two interventions have equivalent effects (Piaggio 2001; Pocock 1991). Third, all trials reported end‐of‐treatment responses, ranging from eight weeks to 26 weeks and long‐term responses beyond this period are not known. Fourth, although all the trials provided information on ethnicity of the participants, the number of patients from each ethnic group was insufficient for subgroup analysis. Thus, any significant difference in the results among the different ethnic groups or populations is not known.

This review consists of published data only. Original data from the manufacturers, as well as information from drug regulatory authorities such as the FDA and EMA will be useful. Unfortunately, the original data from manufacturers were not available. Similarly, the search of the FDA and EMA websites yielded no additional information. Finally, it would be difficult to exclude the possibility of biases, as all the selected trials were funded by the same pharmaceutical company.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Previous publications on colesevelam for T2DM focused on a small number of clinical trials. There has been no quality comprehensive systematic review of the effects of colesevelam on T2DM. This review included six available RCTs. These RCTs provided evidence of colesevelam monotherapy and colesevelam combination therapy with antidiabetic agents. Unfortunately, the relatively small sample size and effect estimates of each of the combinations of intervention modality do not provide sufficient evidence for general use of colesevelam for T2DM.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Data provided by landmark clinical trials have left many unresolved issues and paradoxes regarding diabetes control, cardiovascular risk and cardiovascular outcomes. While tight glycaemic control in reducing microvascular diseases is well established, its role in controlling macrovascular risk remains controversial (Duckworth 2009; Gerstein 2008; Patel 2008; UKPDS 1998). Cardiovascular risk accounts for approximately 70% of all mortality in people with diabetes, especially middle‐aged people of both genders (Laakso 1999). These mortality and morbidity risks are comparable to non‐diabetic individuals who had a cardiovascular event (Haffner 1998). Moreover, treatment focused in reducing other cardiovascular risk factors in addition to hyperglycaemia, appears to be more effective in preventing macrovascular disease than treatment of hyperglycaemia per se (Patel 2007; UKPDS 1998).

Traditionally, the gradual loss of glycaemic control in individuals with T2DM has been attributed to the progressive reduction in beta‐cell mass. This has been the major focus in diabetes research. So far, existing oral pharmacological agents for treatments have not been promising in restoring the beta‐cell mass typically lost during the natural progression of the disease. Some, such as the sulphonylureas, even hasten beta‐cell apoptosis in human islet cells in vitro (Maedler 2005). So far, published data on colesevelam suggest no effects on measurements of beta‐cell function in the short term (eight weeks) (Schwartz 2010). However, the ability of colesevelam to reduce blood glucose levels through the alternative novel non‐insulin modulated pathways may provide a means of sparing the residual functional beta‐cells in individuals with T2DM.

Colesevelam has some theoretical advantages over existing therapies with oral antidiabetic compounds as well as add‐on therapy to insulin, metformin, sulphonylureas and other antidiabetic agents. The reduction in both HbA1c and LDL‐C may help patients with T2DM to achieve the targeted HbA1c and LDL‐C levels. In addition, there is the advantage of a low risk for hypoglycaemic events. Long‐term data on efficacy and safety are not available to advocate the widespread use of colesevelam.

Implications for research.

More information on the benefit‐risk ratio of colesevelam treatment is necessary to assess the long‐term effects, particularly in the management of cardiovascular risks as well as reductions in microvascular and macrovascular complications of T2DM. In addition, long‐term data on patient‐oriented parameters, such as health‐related quality of life, diabetic complications and all‐cause mortality, also need to be investigated.

Acknowledgements

None.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Search terms and databases |

| Unless otherwise stated, search terms are free text terms. Abbreviations: '$': stands for any character; '?': substitutes one or no character; adj: adjacent (i.e. number of words within range of search term); exp: exploded MeSH; MeSH: medical subject heading (MEDLINE medical index term); pt: publication type; sh: MeSH; tw: text word. |

| The Cochrane Library |

| #1 MeSH descriptor Diabetes mellitus, type 2 explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Insulin resistance explode all trees #3 ( (impaired in All Text and glucose in All Text and toleranc* in All Text) or (glucose in All Text and intoleranc* in All Text) or (insulin* in All Text and resistanc* in All Text) ) #4 (obes* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #5 (MODY in All Text or NIDDM in All Text or TDM2 in All Text or TD2 in All Text) #6 ( (non in All Text and insulin* in All Text and depend* in All Text) or (noninsulin* in All Text and depend* in All Text) or (non in All Text and insulindepend* in All Text) or noninsulindepend* in All Text) #7 (typ? in All Text and (2 in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #8 (typ? in All Text and (II in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #9 (non in All Text and (keto* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #10 (nonketo* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #11 (adult* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #12 (matur* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #13 (late in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #14 (slow in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #15 (stabl* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #16 (insulin* in All Text and (defic* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #17 (plurimetabolic in All Text and syndrom* in All Text) #18 (pluri in All Text and metabolic in All Text and syndrom* in All Text) #19 MeSH descriptor Glucose Intolerance explode all trees #20 (typ?2 in All Text near/3 diabet* in All Text) #21 (keto in All Text and (resist* in All Text near/3 diabet* in All Text) ) #22 (non in All Text and (keto* in All Text near/3 diabet* in All Text) ) #23 (nonketo* in All Text near/3 diabet* in All Text) #24 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10) #25 (#11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23) #26 (#24 or #25) #27 MeSH descriptor Diabetes insipidus explode all trees #28 (diabet* in All Text and insipidus in All Text) #29 (#27 or #28) #30 (#26 and not #29) #31 colesevelam* in All Text #32 ((bile in All Text near/6 acids* in All Text) and sequestrant* in All Text) ) #33 (BA* in All Text and sequestrant* in All Text) #34 (#31 or #32 or #33) #35 (#30 and #34) |

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

| CINAHL |

|

| LILACS |

| (colesevelam or bile acid$ sequestrant$ or BA$ sequestrant$ or Cholestagel or Welchol) [Subject descriptor] and (Diabetes mellitus or insulin resistance) [Palavras] and (random$ or placebo$ or trial or group$) [Palavras] |

| OpenGrey |

| (colesevelam OR bile acid* sequestrant* OR BA* sequestrant* OR Cholestagel OR Welchol) [Abstract] and (Diabetes mellitus OR insulin resistance) [Abstract] and (random OR placebo OR trial OR group) [Abstract] |

| Proquest Dissertations and Theses database |

|

Appendix 2. Description of interventions

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) (route, frequency, total dose/day) | Control(s) (route, frequency, total dose/day) |

| Bays 2008 | Colesevelam tablets 3.75 g daily with existing metformin monotherapy or with existing metformin in combination with additional oral antidiabetic agents | Placebo with existing metformin monotherapy or with existing metformin in combination with additional oral antidiabetic agents |

| Fonseca 2008 | Colesevelam tablets 3.75 g daily with existing sulphonylureas monotherapy or with existing sulphonylureas in combination with additional oral antidiabetic agents | Placebo with existing sulphonylureas monotherapy or with existing sulphonylureas in combination with additional oral antidiabetic agents |

| Goldberg 2008 | Colesevelam tablets 3.75 g daily with existing insulin monotherapy or with existing insulin in combination with additional oral antidiabetic agents | Placebo with existing insulin monotherapy or with existing insulin in combination with additional oral antidiabetic agents |

| Rosenstock 2010 | Colesevelam tablets 3.75 g daily and metformin | Placebo and metformin |

| Schwartz 2010 | Colesevelam tablets 3.75 g daily | Placebo |

| Zieve 2007 | Colesevelam tablets 3.75 g daily with existing antidiabetic agents | Placebo with existing antidiabetic agents |

Appendix 3. Baseline characteristics (I)

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) and control(s) | Participating population | Country | Sex (% female) | Age (mean years (SD)) | HbA1c (mean % (SD)) | BMI (mean kg/m2 (SD)) |

| Bays 2008 | I: colesevelam + (metformin only or metformin + oadm) C: placebo + (metformin only or metformin + oadm) |

Participants with T2DM | USA and Mexico | I: 49 C: 47 |

I: 55.7 (9.6) C: 56.9 (9.5) |

I: 8.2 (0.7) C: 8.1 (0.6) |

I: 33.9 (5.3) C: 33.0 (6.3) |

| Fonseca 2008 | I: colesevelam + (sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas + oadm) C: placebo + (sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas + oadm) |

Participants with T2DM | USA and Mexico | I: 44 C: 47 |

I: 56.6 (10.3) C: 57.0 (10.3) |

I: 8.2 (0.68) C: 8.3 (0.72) |

I: 33.1 (5.95) C: 32.5 (5.64) |

| Goldberg 2008 | I: colesevelam + (insulin only or insulin + oadm) C: placebo + (insulin only or insulin + oadm) |

Participants with T2DM | USA and Mexico | I: 48 C: 49 |

I: 56.9 (9.8) C: 56.3 (9.3) |

I: 8.3 (0.62) C: 8.3 (0.63) |

I: 34.9 (5.82) C: 34.9 (5.91) |

| Rosenstock 2010 | I: colesevelam + metformin C: placebo + metformin |

Participants with T2DM | USA, Mexico, Colombia and India | I: 52 C: 60 |

I: 52.7 (11.5) C: 53.9 (10.1) |

I: 7.8 (1.0) C: 7.5 (0.9) |

I: 30.6 (4.7) C: 29.8 (4.4) |

| Schwartz 2010 | I: colesevelam C: placebo |

Participants with T2DM | USA | I: 41 C: 61 |

I: 51.4 (12.7) C: 56.0 (7.9) |

I: 8.2 (0.9) C: 8.7 (0.9)) |

I: 35.2 (3.6) C: 33.4 (5.2) |

| Zieve 2007 | I: colesevelam + oadm C: placebo + oadm |

Participants with T2DM | USA | I: 48 C: 41 |

I: 56.7 (9.7) C: 55.7 (9.1) |

I: 7.9 (0.8) C: 8.1 (0.9) |

I: 32.5 (5.2) C: 32.2 (5.5) |

|

Footnotes BMI: body mass index; C: control; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin A1c; I: intervention; oadm: oral antidiabetic medications; SD: standard deviation; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus | |||||||

Appendix 4. Baseline characteristics (II)

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) and control(s) | Duration of disease (n (%) since diagnosis) | Ethnic groups (%) | Duration of intervention | Follow‐up | Co‐medications |

Co‐interventions (%) |

Co‐morbidities | |

| Bays 2008 | I: colesevelam + (metformin only or metformin + oadm) C: placebo + (metformin only or metformin + oadm) |

‐ | I:

White: 56

Black: 15

Asian: 4

Hispanic: 25

Others: 1 C: White: 60 Black: 17 Asian: 3 Hispanic: 20 Others: 1 |

26 weeks | 0, 12, 18, 26 weeks | Antihypertensives Sulphonylureas Thiazolidinediones α‐glucosidase inhibitors Meglitinides |

‐ | ‐ | |

| Fonseca 2008 | I: colesevelam + (sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas + oadm) C: placebo + (sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas + oadm) |

‐ | I:

White: 59

Hispanic: 29

Black: 10

Asian: 2

Others: 1 C: White: 55 Hispanic: 26 Black: 15 Asian: 3 Others: 1 |

26 weeks | 0, 6, 12, 18, 26 weeks | Sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas plus combination therapy | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Goldberg 2008 | I: colesevelam + (insulin only or insulin + oadm) C: placebo + (insulin only or insulin + oadm) |

‐ | I:

White: 64

Black: 16

Asian: 2

Hispanic: 17

Others: 1 C: White: 64 Black: 19 Asian: 1 Hispanic: 16 Others: 1 |

16 weeks | 0, 4, 8, 16 weeks | Insulin only or insulin plus oadm | I:

AHT: ACEI 41.5 ATII 19.0 BB 18.4 DHP 12.9 TH 17.0 AHL: Fibrates: 8.8 Statin 55.1 C: AHT: ACEI 46.4 ATII 15.7 BB 21.4 DHP 13.6 TH 11.4 AHL: Fibrates: 10.0 Statin 59.3 |

‐ | |

| Rosenstock 2010 | I: colesevelam + metformin C: placebo + metformin |

< 1 year: 175 (47) 1 to 5 years: 81 (28) > 5 years: 30 (11) |

I: White: 15 Hispanic: 61 Black: 2 Asian: 22 C: White: 14 Hispanic: 64 Black: 1 Asian: 21 |

16 weeks | 4, 8, 12, 16 weeks | Metformin | I: ACEI 12 ATII 8 Statins 8 PI 22 C: ACEI 16 ATII 13 Statins 6 PI 20 |

‐ | |

| Schwartz 2010 | I: colesevelam C: placebo |

‐ | I: White: 47 Black: 6 Asian: 0 Hispanic: 47 C: White: 11 Black: 6 Asian: 6 Hispanic: 78 |

8 weeks | 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 weeks | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Zieve 2007 | I: colesevelam + oadm C: placebo + oadm |

‐ | I: White: 45 Black: 23 Hispanic: 23 Others: 7 C: White: 62 Black: 12 Hispanic: 27 Others: 0 |

12 weeks | 1, 4, 8,12 weeks | Sulphonylureas or metformin or sulphonylureas plus metformin |

‐ | ‐ | |

|

Footnotes "‐" denotes not reported ACEI: angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; AHL: antihyperlipidaemics; AHT: antihypertensives; ATII: angiotensin II antagonists; BB: selective β‐blocker; BMI: body mass index; C: control; DHP: dihydropyridine derivatives; I: intervention; oadm: oral antidiabetes medications; PI: platelet aggregations inhibitors; SD: standard deviation; TH: thiazides |

|||||||||

Appendix 5. Matrix of study endpoints

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Primarya end point(s) | Secondaryb end point(s) | Otherc end point(s) | Time period of outcome measurement |

| Bays 2008 | Mean change from baseline HbA1c level | Mean change in HbA1c, FPG and fructosamine levels from baseline to weeks 6, 12, 18 and 26; mean change in C‐peptide, adiponectin and insulin levels and homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) index from baseline to week 26; mean change and mean % change in concentrations of TC, LDL‐C, HDL‐C, non‐HDL‐C, Apo A‐I, and Apo B from baseline to week 26; mean change in TC/HDL‐C, LDL‐C/HDL‐C, non‐HDL‐C/HDL‐C and Apo B/Apo A‐I ratios from baseline to week 26; and median change and median % change in high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hsCRP) and TG levels from baseline to week 26 | Treatment‐emergent adverse events (AEs), clinical laboratory blood test results, changes in vital signs and findings on physical examinations as well as compliance | 0, 12, 18, 26 weeks |

| Fonseca 2008 | Mean change from baseline HbA1c level | Mean change in HbA1c, FPG, fructosamine and C‐peptide levels from baseline to week 26, pre‐defined reduction in FPG level of ≥ 30 mg/dL or in HbA1c level of ≥ 0.7% from baseline at week 26. Other secondary end points included mean % change in lipids, lipoproteins, and lipid and lipoprotein ratios; and median change and median % change in hsCRP and triglycerides | Treatment‐emergent AEs, clinical laboratory blood test results, changes in vital signs, and findings on physical examinations as well as compliance | 0, 6, 12, 18, 26 weeks |

| Goldberg 2008 | Mean change from baseline HbA1c level | Mean change in FPG, fructosamine and HbA1c levels from baseline to weeks 4, 8 and 16; mean change in C‐peptide levels from baseline to week 16; mean change and mean % change in concentrations of TC, LDL‐C, HDL‐C, non‐HDL‐C, TG, and Apo A‐I and Apo B levels and in ratios of TC/HDL‐C, LDL‐C/HDL‐C, non‐HDL‐C/HDL‐C and Apo B/Apo A‐I from baseline to week 16; and median change and median % change in levels of high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein and TGs from baseline to week 16 | Vital signs, physical examinations, treatment‐emergent AEs, and clinical laboratory test results including kidney functions at weeks ‐3 (screening), 0 (randomisation baseline), 8 and 16 or at an early termination visit, if applicable as well as compliance | 0, 4, 8, 16 weeks |

| Rosenstock 2010 | Mean change from baseline HbA1c level | Mean change in FPG, fasting insulin, fasting C‐peptide, post‐meal tolerance test (MTT) glucose, post‐MTT insulin, post‐MTT C‐peptide, change and % change in lipids and Apo, and hsCRP, % of patients achieving HbA1c < 7.0%, A1C ≤ 6.5%, LDL‐C < 100 mg/dL or LDL‐C < 70 mg/dL were also evaluated. HbA1c, FPG, lipids, and lipid and Apo ratios | Vital signs, physical examinations, occurrence and severity of AEs, clinical laboratory test results and compliance | 4, 8, 12, 16 weeks |

| Schwartz 2010 | Change from baseline in glucose disposal rate (insulin clamp) | Change from baseline in M‐value at week 2; change from baseline in area under the curve for glucose (AUCg) and insulin (AUCi) at weeks 2 and 8; acute and chronic effects of colesevelam on postprandial glucose; change from baseline in HbA1c at weeks 0 and 8; change from baseline in FPG and fasting insulin at weeks 2, 4, 6 and 8; and change from baseline in fructosamine at weeks 4 and 8 | Vital signs, clinical laboratory tests, and ECGs, evaluation of the incidence and severity of AEs as well as compliance | 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 weeks |

| Zieve 2007 | Mean change from baseline HbA1c level | Mean changes in fructosamine levels, FPG levels, the postprandial glucose level, the meal glucose response, % changes in lipid parameters (LDL‐C, TC, HDL‐C, TG, Apo) A‐I and B, and LDL particle concentration) | AEs, laboratory tests at weeks ‐5, 0 and 12 as well as compliance | 1, 4, 8, 12 weeks |

|

Footnotes a,b Verbatim statement in the publication; c not explicitly stated as primary or secondary endpoint(s) in the publication AE: adverse event; Apo: apolipoprotein; AUCg: area under the curve for glucose; AUCi: area under the curve for insulin; ECG: electrocardiogram; FPG: fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL‐C: high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA‐I: homeostasis model assessment index; hsCRP: high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LDL‐C: low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; MTT: meal tolerance test; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglyceride | ||||

Appendix 6. Adverse events (I)

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) and control(s) | Deaths (n) | All adverse events (n (%)) | Severe/serious adverse events (n (%)) | Left study due to adverse events (n (%)) |

| Bays 2008 | I: colesevelam + (metformin only or metformin + oadm) C: placebo + (metformin only or metformin + oadm) |

I: 0 C: 0 |

I: 8 (5) C: 5 (3) T: 13 (6) |

I: 4 (3) C: 2 (1) T: 6 (3) |

I: 8 (5) C: 4 (3) T: 12 (6) |

| Fonseca 2008 | I: colesevelam + (sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas + oadm) C: placebo + (sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas + oadm) |

I: 0 C: 0 |

I: 145 (63) C: 126 (55) T: 261 (59) |

I: 9 (4) C: 7 (3) T: 16 (4) |

I: 18 (8) C: 9 (4) T: 27 (6) |

| Goldberg 2008 | I: colesevelam + (insulin only or insulin + oadm) C: placebo + (insulin only or insulin + oadm) |

I: 0 C: 1 |

I: 92 (63) C: 82 (59) T: 174 (61) |

I: 13 (9) C: 11 (8) T: 24 (8) |

I: 2 (1) C: 1 (1) T: 3 (1) |

| Rosenstock 2010 | I: colesevelam + metformin C: placebo + metformin |

I: 0 C: 0 |

I: 97 (67) C: 97 (69) T: 195 (69) |

I: 2 (1) C: 1 (1) T: 3 (1) |

I: 5 (3) C: 9 (6) T: 14 (5) |

| Schwartz 2010 | I: colesevelam C: placebo |

I: 0 C: 0 |

I: 8 (47) C: 6 (33) T: 14 (0.4) |

I: 1 (6) C: 1 (6) T: 2 (6) |

I: 0 (0) C: 0 (0) |

| Zieve 2007 | I: colesevelam + oadm C: placebo + oadm |

‐ | I: 20 (65) C: 22 (65) T: 42 (65) |

‐ | I: 2 (7) C: 1 (3) T: 3 (5) |

|

Footnotes "‐" denotes not reported C: control; I: intervention; oadm: oral antidiabetes medications; T: total | |||||

Appendix 7. Adverse events (II)

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) and control(s) | Hospitalisation (n (%)) | Outpatient treatment (n (%)) | All hypoglycaemic episodes (n (%)) | Severe/serious hypoglycaemic episodes (n (%)) | Nocturnal hypoglycaemic episodes (n (%)) | Symptoms (n (%)) |

| Bays 2008 | I: colesevelam + (metformin only or metformin + oadm) C: placebo + (metformin only or metformin + oadm) |

‐ | ‐ | I: 1 (0.6) C: 0 (0) T: 1 (0.5) |

‐ | ‐ | I: 8 (5) C: 5 (3) T: 13 (6) |

| Fonseca 2008 | I: colesevelam + (sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas + oadm) C: placebo + (sulphonylureas only or sulphonylureas + oadm) |

‐ | ‐ | I: 6 (3) C: 2 (1) T: 8 (2) |

‐ | ‐ | I: 145 (63) C: 126 (55) T: 261 (59) |

| Goldberg 2008 | I: colesevelam + (insulin only or insulin + oadm) C: placebo + (insulin only or insulin + oadm) |

‐ | ‐ | I: 0 C: 0 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Rosenstock 2010 | I: colesevelam + metformin C: placebo + metformin |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | I: 97 (61) C: 97 (69) T: 195 (69) |

| Schwartz 2010 | I: colesevelam C: placebo |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Zieve 2007 | I: colesevelam + oadm C: placebo + oadm |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Footnotes "‐" denotes not reported C: control; I: intervention; oadm: oral antidiabetes medications; T: total | |||||||

Appendix 8. Survey of authors' reactions to provide information on trials

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Study author contacted | Study author replied |

| Bays 2008 | Y | Y |