Abstract

Background

Healthcare professionals, including nurses, frequently advise people to improve their health by stopping smoking. Such advice may be brief, or part of more intensive interventions.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of nursing‐delivered smoking cessation interventions in adults. To establish whether nursing‐delivered smoking cessation interventions are more effective than no intervention; are more effective if the intervention is more intensive; differ in effectiveness with health state and setting of the participants; are more effective if they include follow‐ups; are more effective if they include aids that demonstrate the pathophysiological effect of smoking.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register and CINAHL in January 2017.

Selection criteria

Randomized trials of smoking cessation interventions delivered by nurses or health visitors with follow‐up of at least six months.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors extracted data independently. The main outcome measure was abstinence from smoking after at least six months of follow‐up. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence for each trial, and biochemically‐validated rates if available. Where statistically and clinically appropriate, we pooled studies using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model and reported the outcome as a risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Main results

Fifty‐eight studies met the inclusion criteria, nine of which are new for this update. Pooling 44 studies (over 20,000 participants) comparing a nursing intervention to a control or to usual care, we found the intervention increased the likelihood of quitting (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.38); however, statistical heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 50%) and not explained by subgroup analysis. Because of this, we judged the quality of evidence to be moderate. Despite most studies being at unclear risk of bias in at least one domain, we did not downgrade the quality of evidence further, as restricting the main analysis to only those studies at low risk of bias did not significantly alter the effect estimate. Subgroup analyses found no evidence that high‐intensity interventions, interventions with additional follow‐up or interventions including aids that demonstrate the pathophysiological effect of smoking are more effective than lower intensity interventions, or interventions without additional follow‐up or aids. There was no evidence that the effect of support differed by patient group or across healthcare settings.

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate quality evidence that behavioural support to motivate and sustain smoking cessation delivered by nurses can lead to a modest increase in the number of people who achieve prolonged abstinence. There is insufficient evidence to assess whether more intensive interventions, those incorporating additional follow‐up, or those incorporating pathophysiological feedback are more effective than one‐off support. There was no evidence that the effect of support differed by patient group or across healthcare settings.

Plain language summary

Does support and intervention from nurses help people to stop smoking?

Background

Most smokers want to quit, and may be helped by advice and support from healthcare professionals. Nurses are the largest healthcare workforce, and are involved in virtually all levels of health care. The main aim of this review was to determine if nursing‐delivered interventions can help adult smokers to stop smoking.

Study characteristics

This review of clinical trials covered 58 studies in which nurses delivered a stop‐smoking intervention to smokers. More than 20,000 participants were included in the main analysis, including hospitalized adults and adults in the general community. The most recent search was conducted in January 2017. All studies reported whether or not participants had quit smoking at six months or longer.

Key Results

This review found moderate‐quality evidence that advice and support from nurses could increase people's success in quitting smoking, whether in hospitals or in community settings. Eleven studies compared different nurse‐delivered interventions and did not find that adding more components changed the effect.

Quality of evidence

The quality of evidence was moderate, meaning that further research may change our confidence in the result. This is because results were not consistent across all of the studies, and in some cases there were not very many studies contributing to comparisons.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Nursing interventions for smoking cessation.

| Nursing interventions for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adult smokers Settings: Any Intervention: Cessation interventions delivered by nurses | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Nursing interventions | |||||

| Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up (high and low intensity) Follow‐up: 6+ months | 122 per 10001 | 157 per 1000 (147 to 168) | RR 1.29 (1.21 to 1.38) | 20,881 (44 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2, 3 | Pooled results from the two subgroups described below |

| Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up ‐ High intensity intervention Follow‐up: 6+ months | 141 per 10001 | 182 per 1000 (171 to 195) | RR 1.29 (1.21 to 1.38) | 16,865 (37 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2, 3 | High intensity = initial contact > 10 minutes, additional materials (e.g. manuals) and/or strategies other than simple leaflets, additional follow‐up visits |

| Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up ‐ Low intensity intervention Follow‐up: 6+ months | 51 per 10001 | 64 per 1000 (50 to 82) | RR 1.27 (0.99 to 1.62) | 4016 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2, 4 | Low intensity = advice provided (with or without a leaflet) during single consultation lasting 10 minutes or less with up to one follow‐up visit |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Control group quit rate based on average across all included studies. 2Not downgraded for risk of bias: Sensitivity analyses excluding studies at high or unclear risk of bias did not significantly alter the effect size. 3Downgraded one level for inconsistency: Unexplained statistical heterogeneity present. 4Downgraded one level for imprecision: Total number of events < 300, confidence intervals include a significant effect and no effect.

Background

Tobacco‐related deaths and disabilities are on the increase worldwide because of continued use of tobacco (mainly cigarettes). Tobacco use has reached epidemic proportions in many low‐ and middle‐income countries, while steady use continues in high‐income nations like the USA (The Tobacco Atlas 2015; CDC 2016). According to the Centers for Disease Control, 68% of adult smokers in the USA want to quit and millions have tried (CDC 2017), with 70% of smokers visiting a healthcare professional each year (AHRQ 2008). Nurses, representing the largest number of healthcare providers worldwide, are involved in most of these visits, and therefore have the potential for a profound effect on the reduction of tobacco use (Youdan 2005).

Systematic reviews (e.g. Stead 2013) have confirmed the effectiveness of advice from physicians to stop smoking. The Agency for Health Care Research and Quality Clinical Practice Guideline (AHRQ 2008) lists nurses as one of the many providers from whom advice to stop smoking could increase quit rates, but identifies the effectiveness of advice to quit smoking given by clinicians other than physicians (including nurses) as an area requiring further research. The American Nurses Association (ANA 2012) state that nurses have tremendous potential to implement smoking cessation interventions effectively and advance tobacco use reduction goals proposed by Healthy People 2020, and note that nurses must be equipped to assist with smoking cessation, to prevent tobacco use, and to promote strategies to decrease exposure to second‐hand smoke. The American Nurses Association/American Nurses Foundation promotes the mission of Tobacco‐Free Nurses to the nation’s registered nurses through its constituent associations, members, and organizational affiliates (ANA 2012).

A review of nursing's specific role in smoking cessation is essential if the profession is to endorse the International Council of Nurses' (ICN) call to encourage nurses to "...integrate tobacco use prevention and cessation ... as part of their regular nursing practice" (ICN 2012).

The aim of this review is to examine and summarize randomized controlled trials where nurses provided smoking cessation interventions. The review therefore focuses on the nurse as the intervention provider, rather than on a particular type of intervention. We do not include smoking cessation interventions targeting pregnant women, because of the particular circumstances and motivations among this population. Interventions for pregnant smokers have been reviewed elsewhere (Chamberlain 2017; Coleman 2015).

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of nursing‐delivered interventions on smoking behavior in adults. To establish whether nursing‐delivered smoking cessation interventions: (i) are more effective than no intervention; (ii) are more effective if the intervention is more intensive; (iii) differ in effectiveness with health state and setting of the participants; (iv) are more effective if they include follow‐ups; (v) are more effective if they include aids that demonstrate the pathophysiological effect of smoking.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Inclusion criteria for studies were: (i) they had to have at least two treatment groups; (ii) allocation to treatment groups must have been stated to be 'random'. We excluded studies that used historical controls.

Types of participants

Participants were adult smokers, 18 years and older, of either gender and recruited in any type of healthcare or other setting. The only exceptions were studies that had exclusively recruited pregnant women. We included trials in which 'recent quitters' were classified as smokers, but conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether they differed from trials that excluded such individuals.

Types of interventions

We define 'nursing intervention' as the provision of advice, counseling, and/or strategies to help people quit smoking. The review includes cessation studies that compared usual care with an intervention, brief advice with a more intensive smoking cessation intervention or different types of interventions. We included studies of smoking cessation interventions as a part of multifactorial lifestyle counseling or rehabilitation only if it was possible to discern the specific nature and timing of the intervention, and to extract data on the outcomes for those who were smokers at baseline. We define 'advice' as verbal instructions from the nurse to stop smoking, whether or not they provided information about the harmful effects of smoking. We grouped interventions into low and high intensity for comparison. We categorize as 'low intensity' those trials where advice was provided (with or without a leaflet) during a single consultation lasting 10 minutes or less, with up to one follow‐up visit. We categorize as 'high intensity' those trials where the initial contact lasted more than 10 minutes, there were additional materials (e.g. manuals) or strategies or both, other than simple leaflets, and usually participants had more than one follow‐up contact. We excluded studies where participants were randomized to receive advice versus advice plus some form of pharmacotherapy, since these were primarily comparisons of the effectiveness of pharmacotherapies rather than nursing interventions. These are covered in separate reviews (Cahill 2016; Hughes 2014; Stead 2012).

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome was smoking cessation rather than a reduction in withdrawal symptoms or a reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked. Trials had to report follow‐up of at least six months for inclusion in the review. We excluded trials which did not include data on smoking cessation rates. We used the strictest available criteria to define abstinence in each study, e.g. sustained cessation rather than point prevalence. Where biochemical validation was used, we regarded only participants meeting the biochemical criteria for cessation as abstainers. We counted participants lost to follow‐up as continuing smokers (in intention‐to‐treat analyses).

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Tobacco Addiction Review Group Specialized Register for trials (most recent search 10 January 2017). This Register includes trials located from systematic searches of electronic databases and handsearching of specialist journals, conference proceedings, and reference lists of previous trials and overviews. At the time of the search the Register included the results of searches of:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), in the Cochrane Library 2016, Issue 11;

MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20161202;

Embase (via OVID) to week 201650;

PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20160926.

See the Tobaco Addiction Group module in the Cochrane Library for full search strategies and a list of other resources searched. We checked all trials with 'nurse*' or 'nursing' or 'health visitor' in the title, abstract, or keywords for relevance. See Appendix 1 for the search strategy. We also searched the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) on OVID for 'nursing' and 'smoking cessation' from 1983 to January 2017.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this update, two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts. Where there was uncertainty, we requested the full text. Two review authors checked the full text of articles flagged for inclusion, with discrepancies resolved by discussion or by referral to a third review author.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from the published reports, contacting study authors where necessary, and resolving disagreements by referral to a third person. For each trial, we extracted the following data:

(i) Author(s) and year; (ii) Country of origin, study setting, and design; (iii) Number and characteristics of participants and definition of 'smoker'; (iv) Description of the intervention and designation of its intensity (high or low); (v) Outcomes and biochemical validation.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool to assess bias in four domains:

random sequence generation (a potential source of selection bias);

allocation concealment (also a potential source of selection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

other biases.

We did not judge the trials on the basis of blinding, as we tested behavioral interventions where blinding of participants and providers is not possible.

We judged each included study to be at high, unclear, or low risk of bias in each of the above domains, according to the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook.

Measures of treatment effect

We use the risk ratio (RR) for summarizing individual trial outcomes and for the estimate of the pooled effect. Where we judged a group of studies to be sufficiently clinically and statistically homogeneous, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect method (Greenland 1985) to calculate a weighted average of the risk ratios of the individual trials, with a 95% confidence interval.

Dealing with missing data

In trials where the details of the methodology were unclear or where the results were expressed in a form that did not allow for extraction of key data, we approached the original investigators for additional information. We treated participants lost to follow‐up as continuing smokers. We excluded from totals only those participants who died before follow‐up or were known to have moved to an untraceable address.

Assessment of heterogeneity

To assess statistical heterogeneity between trials we used the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). This measures the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than to chance. Values of I2 over 75% indicate a considerable level of heterogeneity (Chapter 8, Cochrane Handbook).

'Summary of findings' table

Following standard Cochrane methodology, we created a 'Summary of findings' table for our primary outcome, smoking cessation at longest follow‐up. This includes a GRADE evaluation of the quality of evidence, based on the five standard considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias).

Results

Description of studies

Included studies

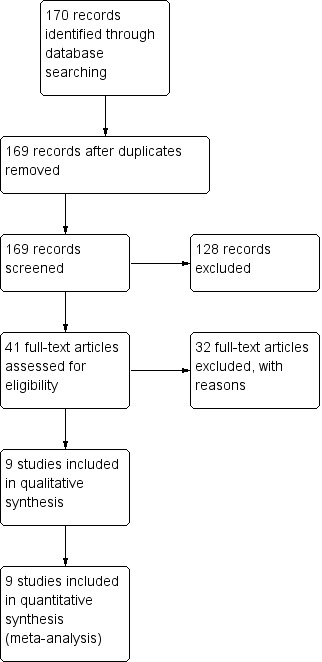

Fifty‐eight trials met the inclusion criteria, of which nine are new for this update (Kim 2003; Jorstad 2013; Berndt 2014; Hornnes 2014; Gilbody 2015; Kadda 2015; Pardavila‐Belio 2015; Zwar 2015; Smit 2016). Trials were of nursing interventions for smoking cessation in adults who used tobacco (primarily cigarettes), published between 1987 and 2017. One trial (Sanders 1989a; Sanders 1989b) had two parts with randomization at each stage, so is treated here as two separate studies, making a total of 59 studies in the Characteristics of included studies table. Forty‐four studies contributed to the primary meta‐analysis that compared a nursing intervention to a usual‐care or minimal‐intervention control. Eleven studies included a comparison between two nursing interventions, involving different components or different numbers of contacts, and contribute to a secondary meta‐analysis. Six further studies did not contribute to a meta‐analysis and their results are described separately. Sample sizes of studies contributing to a meta‐analysis ranged from 25 to 2700, but were typically between 150 and 500. Figure 1 documents the flow of studies screened and included in this update.

1.

Study flow diagram for 2017 update

Seventeen trials took place in the USA, 11 in the UK, five in The Netherlands, four in Canada, three in Australia, Denmark, and Spain, and two each in China, Japan, Norway, and South Korea. One trial took place in Belgium, one in Greece, and one in Sweden. One multicenter study was conducted in multiple European countries.

Twenty‐two trials intervened with hospitalized participants (Taylor 1990; DeBusk 1994; Rigotti 1994; Lewis 1998; Allen 1996; Carlsson 1997; Miller 1997; Feeney 2001; Bolman 2002; Hajek 2002; Quist‐Paulsen 2003; Froelicher 2004; Hasuo 2004; Chouinard 2005; Hennrikus 2005; Nagle 2005; Hanssen 2007; Wood 2008; Meysman 2010; Cossette 2011; Berndt 2014; Hornnes 2014). Two trials (Rice 1994; Jorstad 2013) recruited hospitalized participants, but with follow‐up after discharge. Kadda 2015 recruited participants following discharge after open‐heart surgery. Twenty‐eight studies recruited from primary care or outpatient clinics (Sanders 1989b; Janz 1987; Vetter 1990; Sanders 1989a; Risser 1990; Hollis 1993; Nebot 1992; Family Heart 1994; OXCHECK 1994; Tønnesen 1996; Campbell 1998; Lancaster 1999; Steptoe 1999; Canga 2000; Aveyard 2003; Kim 2003; Ratner 2004; Hilberink 2005; Kim 2005; Duffy 2006; Sanz‐Pozo 2006; Tønnesen 2006; Aveyard 2007; Jiang 2007; Wood 2008; Chan 2012; Gilbody 2015; Zwar 2015; Smit 2016). In some trials, the recruitment took place during a clinic visit, whilst in others the invitation to enroll was made by letter. One study (Terazawa 2001) recruited employees during a workplace health check, two studies enrolled community‐based adults motivated to make a quit attempt (Davies 1992; Alterman 2001), one study recruited mothers taking their child to a pediatric clinic (Curry 2003), one study recruited people being visited by a home healthcare nurse (Borrelli 2005), and one study recruited university students on campus (Pardavila‐Belio 2015).

Eighteen studies focused on adults with diagnosed cardiovascular health problems (Taylor 1990; DeBusk 1994; Family Heart 1994; Rice 1994; Rigotti 1994; Allen 1996; Carlsson 1997; Miller 1997; Campbell 1998; Feeney 2001; Bolman 2002; Hajek 2002; Jiang 2007; Chan 2012 (subgroup with cardiovascular disease); Cossette 2011; Jorstad 2013; Berndt 2014; Hornnes 2014; Kadda 2015), two studies were in participants with respiratory diseases (Tønnesen 1996; Tønnesen 2006), one was in people with diabetes (Canga 2000), and one was in people with severe mental illness (Gilbody 2015). One study recruited participants either with diagnosed cardiovascular health problems or judged to be at high risk of developing heart disease (Wood 2008). Two studies recruited surgical patients: Ratner 2004 recruited people attending a surgical pre‐admission clinic and Meysman 2010 recruited people admitted to surgical wards. One study recruited head‐and‐neck‐cancer patients at four medical centres (Duffy 2006).

All studies included adults 18 years and older who used some form of tobacco. Allen 1996, Curry 2003 and Froelicher 2004 studied women only, and Terazawa 2001 and Kim 2003 studied men only. The definition of tobacco use varied and in some cases included recent quitters.

Nine studies examined a smoking cessation intervention as a component of multiple risk factor reduction interventions in adults with cardiovascular disease (DeBusk 1994; Allen 1996; Carlsson 1997; Campbell 1998; Hanssen 2007; Jiang 2007; Wood 2008; Jorstad 2013; Kadda 2015). In four studies, the smoking cessation component was clearly defined, of high intensity, and independently measurable (DeBusk 1994; Allen 1996; Carlsson 1997; Jiang 2007), whereas in the remaining five the smoking component was less clearly specified (Campbell 1998; Hanssen 2007; Wood 2008; Jorstad 2013; Kadda 2015).

Fourty‐four studies with a total of over 20,000 participants contributed to the main comparison of nursing intervention versus control. We classified 36 as high‐intensity on the basis of the planned intervention, although in some cases implementation may have been incomplete. In seven, we classified the intervention as low‐intensity (Janz 1987; Vetter 1990; Davies 1992; Nebot 1992; Tønnesen 1996; Aveyard 2003; Nagle 2005). All of these were conducted in outpatient, primary care or community settings. One further study (Hajek 2002) may be considered as a comparison between a low‐intensity intervention and usual care. Participants in the usual‐care control group received systematic brief advice and self‐help materials from the same nurses who provided the intervention. Unlike the other trials in the low‐intensity subgroup, this trial was conducted amongst inpatients with cardiovascular disease. Since the control group received a form of nursing intervention, we primarily classified the trial as a comparison of two intensities of nursing intervention. But since other studies had usual‐care groups that may have received advice from other healthcare professionals, we also report the sensitivity of the main analysis results to including it as a low‐intensity nursing intervention compared to usual‐care control.

Hajek 2002 and 10 other studies contributed to a second group comparing two interventions involving a nursing intervention. Three of these tested additional components as part of a session: demonstration of carbon monoxide (CO) levels to increase motivation to quit (Sanders 1989b); CO and spirometry feedback (Risser 1990); and CO feedback plus additional materials and an offer to find a support buddy (Hajek 2002). Five involved additional counseling sessions from a nurse (Alterman 2001; Feeney 2001; Tønnesen 2006; Aveyard 2007; Jiang 2007). One other study compared two interventions with a usual‐care control (Miller 1997). The minimal intervention condition included a counseling session and one telephone call after discharge from hospital. In the intensive condition, participants received three additional telephone calls, and those who relapsed were offered further face‐to‐face meetings, and nicotine replacement therapy if needed. We classified both interventions as intensive in the main meta‐analysis, but compared the intensive and minimal conditions in a separate analysis of the effect of additional follow‐up. Chouinard 2005 also assessed the effect of additional telephone support as an adjunct to an inpatient counseling session, so is pooled in a subgroup with Miller 1997. We included in the same subgroup a study that tested additional telephone follow‐up as a relapse prevention intervention for people who had inpatient counseling (Hasuo 2004).

Five studies (Family Heart 1994; OXCHECK 1994; Campbell 1998; Steptoe 1999; Wood 2008) were not included in any meta‐analysis and do not have results displayed graphically because their designs did not allow us to extract appropriate outcome data. The first part of a two‐stage intervention study is also included in this group (Sanders 1989a); the second part (Sanders 1989b) is included in one of the meta‐analyses. These studies are discussed separately in the Effects of interventions section below.

We determined whether the nurses delivering the intervention were providing it alongside clinical duties that were not smoking‐related, were working in health promotion roles, or were employed specifically as project nurses. Of the high‐intensity intervention studies, 21 used nurses for whom the intervention was a core component of their role (Hollis 1993; DeBusk 1994; Allen 1996; Carlsson 1997; Terazawa 2001; Kim 2003; Quist‐Paulsen 2003; Froelicher 2004; Duffy 2006; Aveyard 2007; Chan 2012; Meysman 2010; Cossette 2011; Jorstad 2013; Berndt 2014; Hornnes 2014; Gilbody 2015; Kadda 2015; Pardavila‐Belio 2015; Zwar 2015; Smit 2016). One study (Kim 2005) employed retired nurses who were trained to provide a brief intervention using the '5 As' framework. In only four studies were intensive interventions intended to be delivered by nurses for whom it was not a core task (Lancaster 1999; Bolman 2002; Curry 2003; Sanz‐Pozo 2006). Most of the low‐intensity interventions were delivered by primary care or outpatient clinic nurses. One low‐intensity inpatient intervention was delivered by a clinical nurse specialist (Nagle 2005).

Follow‐up periods for reinforcement and outcome measurements varied across studies, with a tendency for limited reinforcement and shorter follow‐up periods in the older studies. All trials had some contact with participants in the first three months of follow‐up for restatement of the intervention or point prevalence data collection or both. Eight of the studies had less than one year final outcome data collection (Janz 1987; Vetter 1990; Davies 1992; Lewis 1998; Canga 2000; Kim 2003; Berndt 2014; Pardavila‐Belio 2015). The rest had follow‐up at one year or beyond. The outcome used for the meta‐analysis was the longest follow‐up (six months and beyond), with the exception of Hanssen 2007, in which we preferred 12‐month over 18‐month data. The outcome in this study was point prevalence abstinence and we judged the 18‐month data to be too conservative, due to a rise in abstinent participants in the control group.

A brief description of the main components of each intervention is provided in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Excluded studies

Sixty studies that we had identified as potentially relevant but subsequently excluded are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, along with the reason for exclusion for each. The most common reasons for exclusion were: study design (not a randomized clinical trial); less than six months follow‐up; multicomponent studies with insufficient detail on smoking intervention/outcome; and studies in which the impact of the nursing intervention was confounded by additional pharmacological or behavioral treatment that was not provided to the control arm.

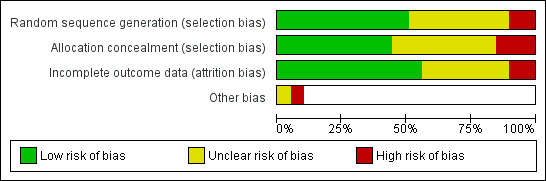

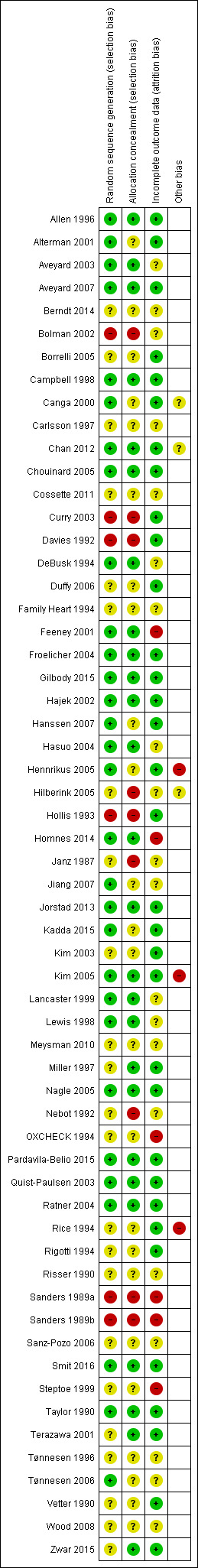

Risk of bias in included studies

As seen in Figure 2, we rated most studies at low or unclear risk of selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment) and attrition bias (loss to follow‐up). As seen in Figure 3, we judged 16 studies to be at low risk of bias across all domains, and 16 at high risk of bias in at least one domain. The rest were at unclear risk of bias.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Thirty studies provided details of a method of random sequence generation judged to be at low risk of bias, and a further 23 studies did not report how the sequence was generated and were hence rated as unclear for this domain. We judged five studies to be at high risk based on their reported methods of random sequence generation: Bolman 2002 was a cluster‐randomized study in which some hospitals picked their allocation; in Curry 2003 participants drew a colored ball from a bag; Davies 1992 allocated based on order of attendance; Hollis 1993 randomized participants based on health record number; and Sanders 1989a/Sanders 1989b randomized participants based on day of attendance. In addition to these five studies, we rated three further studies in which providers rather than participants were randomized at high risk of selection bias: Hilberink 2005 reported that self‐selection at practice level may have affected the results; in Janz 1987 allocation was determined by clinic session; and in Nebot 1992 the providers were also responsible for allocating participants, rendering allocation concealment impossible. Overall, we judged 26 studies to be at low risk of bias for allocation concealment, 24 studies had unclear risk of bias because concealments was unspecified, and we rated eight studies at high risk of bias for concealment. A sensitivity analysis including only the results of studies judged to be at low risk of selection bias did not alter the main conclusions.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged 33 studies that reported minimal to moderate loss to follow‐up and accounted for all participants in their reporting to be at low risk of attrition bias. A further 20 studies did not provide sufficient detail with which to judge the likelihood of attrition bias and hence we rated them as 'unclear' for this domain. We judged five studies to be at high risk of attrition bias: in Feeney 2001, 79% of usual‐care participants were not followed up; OXCHECK 1994 stated that their methods of accounting for missing participants may have overestimated the effect; in Sanders 1989a/Sanders 1989b only a subsample of participants from the control group was followed up; and in Steptoe 1999 and in Hornnes 2014 overall dropout rates were high and varied between intervention and control groups.

Other potential sources of bias

Definitions of abstinence ranged from single point prevalence to sustained abstinence (multiple point prevalence with self‐report of no slips or relapses). In one study (Miller 1997) we used validated abstinence at one year rather than continuous self‐reported abstinence, because only the former outcome was reported for disease diagnosis subgroups.

Of the 44 studies included in the primary meta‐analysis, 22 biochemically validated self‐reports of abstinence using either urinary/saliva cotinine or exhaled CO. One study tested CO levels only amongst people followed up in person (Curry 2003), and five studies used some validation but did not report rates based on biochemical validation of every self‐reported quitter (Nebot 1992; Rice 1994; Miller 1997; Froelicher 2004; Borrelli 2005). Fifteen studies did not use any biochemical validation and relied on self‐reported smoking cessation at a single follow‐up, although two warned participants that samples might be requested for testing (i.e. 'bogus pipeline'), and Jiang 2007 sought confirmation of smoking status from a family member.

We judged three studies (Rice 1994; Hennrikus 2005; Kim 2005) to be at high risk of other bias because of differences between intervention and control groups in validation rates for reported cessation. We judged two studies to be at unclear risk of bias. In Canga 2000, the same nurse conducted all interviews and follow‐up examinations, allowing the potential for observer bias, and in Chan 2012 there was potential for the study intervention to overlap with the standard care received by participants in the control group.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Effects of intervention versus control/usual care

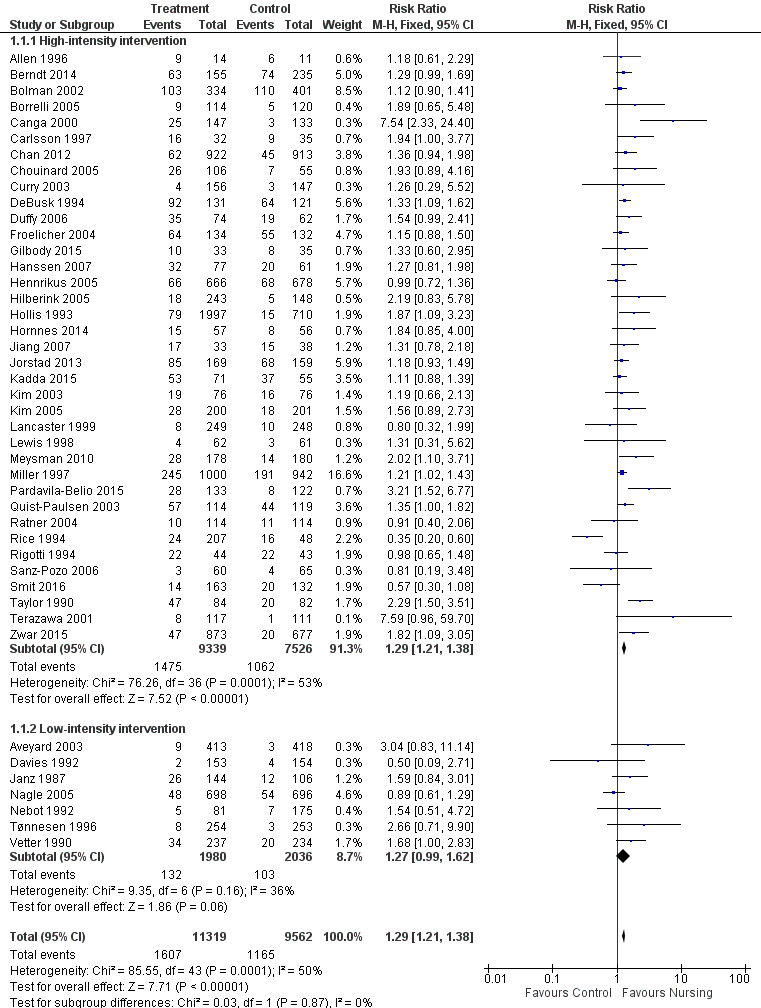

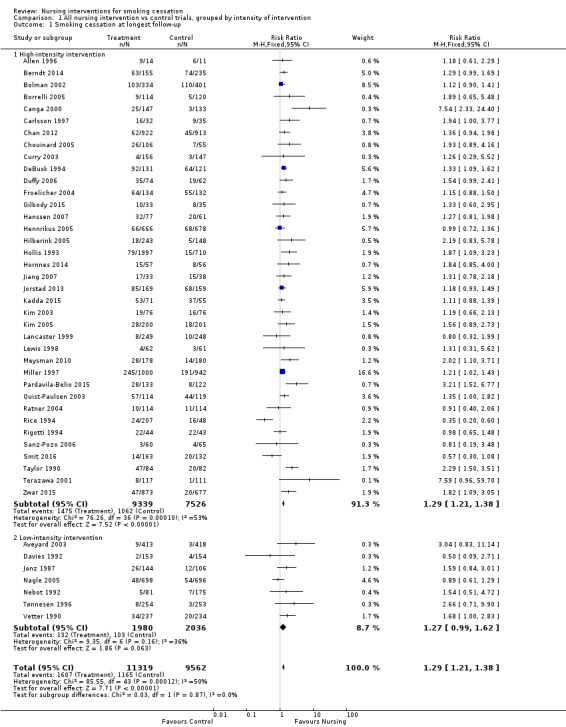

Smokers offered advice by a nursing professional had an increased likelihood of quitting compared to smokers without intervention, with evidence of moderate statistical heterogeneity between the results of the 44 studies contributing to this comparison (I2 = 50%). Heterogeneity was marginally more apparent in the subgroup of 37 high‐intensity trials (I2 = 53%). There was one trial with a significant negative effect for treatment (Rice 1994). This result may be explained by the fact that participants in both arms were advised to quit and more people in the control group had had coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Further, a multivariate analysis of one‐year follow‐up data revealed quitters were significantly more likely to be less than 48 years old, male, to have had individualized versus group or no cessation instruction, and to have had a high degree of perceived threat relative to their health state. In addition to this, three studies reported particularly large positive effects (Canga 2000; Terazawa 2001; Pardavila‐Belio 2015). Pooling all 44 studies using a fixed‐effect model gave a risk ratio (RR) of 1.29 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.21 to 1.38 at the longest follow‐up (Figure 4; Analysis 1.1). Because of the heterogeneity we tested the sensitivity to pooling the studies using a random‐effects model. This did not materially alter the estimated effect size or greatly widen the confidence interval (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.45, analysis not shown). A sensitivity analysis excluding the four outlying trials widened the CI but did not alter the point estimate whilst greatly reducing statistical heterogeneity in the high‐intensity subgroup (I2 = 15%). A further sensitivity analysis restricted to only those studies at low risk of bias across all domains also did not significantly alter the point estimate (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.51, analysis not shown).

4.

Trials of nursing intervention versus control grouped by intensity of intervention. Outcome: Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All nursing intervention vs control trials, grouped by intensity of intervention, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

We also tested the sensitivity of these results to excluding studies that did not validate all reports of abstinence, and limiting the analysis to studies judged to be at low risk of selection bias. None of these altered the estimates to any great extent, although confidence intervals became wider due to the smaller number of studies. Excluding one study (Bolman 2002) for which we were not able to enter the numbers of quitters directly did not alter the results.

Some participants in Taylor 1990 had been encouraged to use nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Exclusion of these people did not alter the significant effect of the intervention in this study. In Miller 1997 more people in the intervention conditions than the controls used NRT (44% of intensive and 39% of minimal intervention versus 29% of control). People who were prescribed NRT had lower quit rates than those who were not, but the relative differences in quit rates between the usual‐care and intervention groups were similar for the subgroups that did and did not use NRT. However, because of the different rates of use of NRT, it is probable that the increased use of NRT contributed to the effects of the nursing intervention. Use of NRT was also encouraged as part of the Canga 2000 intervention, with 17% of the intervention group accepting a prescription, and as part of the Duffy 2006 intervention, although at six months similar percentages in the intervention and control groups had used NRT over the course of the study.

Six further studies which compared a nursing intervention to control/usual care were not included in the meta‐analysis (Sanders 1989a; Family Heart 1994; OXCHECK 1994; Campbell 1998; Steptoe 1999; Wood 2008). Although they met the main inclusion criteria, in five trials the design did not allow data extraction for meta‐analysis in a comparable format to other studies, and in Sanders 1989a only a random sample of the control group was followed up.

Sanders 1989a, in which smokers visiting their family doctor were asked to make an appointment for cardiovascular health screening, reported that only 25.9% of the patients made and kept such an appointment. The percentage that had quit at one month and at one year and reported last smoking before the one‐month follow‐up was higher both in the attenders (4.7%) and the non‐attenders (3.3%) than in the usual‐care controls (0.9%). This suggests that the invitation to make an appointment for health screening could have been an anti‐smoking intervention in itself, and that the additional effect of the structured nursing intervention was small.

We do not have comparable data for OXCHECK 1994, which used similar health checks, because the households had been randomized to be offered the health check in different years. The authors compared the proportions of smokers in the intervention group who reported stopping smoking in the previous year to patients attending for their one‐year follow‐up, and to controls attending for their first health check. They found no difference in the proportions that reported stopping smoking in the previous year.

The Family Heart 1994 study offered nurse‐led cardiovascular screening for men aged 40 to 59 and for their partners, with smoking cessation as one of the recommended lifestyle changes. Cigarette smokers were invited to attend up to three further visits. Smoking prevalence was lower amongst those who returned for the one‐year follow up than amongst the control group screened at one year. This difference was reduced if non‐returners were assumed to have continued to smoke, and if CO‐validated quitting was used. In that case there was a reduction of only about one percentage point, with weak evidence of a true reduction.

Campbell 1998 invited people with a diagnosis of coronary heart disease to nurse‐run clinics promoting medical and lifestyle aspects of secondary prevention. There was no significant effect on smoking cessation. At one year the decline in smoking prevalence was greater in the control group than in the intervention group. Four‐year follow‐up did not alter the effect of a lack of benefit.

Steptoe 1999 recruited people at increased risk of coronary heart disease for a multicomponent intervention. The quit rate amongst smokers followed up after one year was not significantly higher in the intervention group (9.4%, 95% CI ‐9.6 to 28.3), and there was greater loss to follow‐up of smokers in the intervention group.

Wood 2008 recruited people with established or increased risk of coronary heart disease for a multicomponent lifestyle intervention, coordinated by nurses. The authors reported results separately for those participants recruited in hospital and those recruited in general practice. For coronary patients recruited in hospital who had smoked within one month at baseline, abstinence at one year favored the intervention group (58% versus 47%), but the difference was not significant (P = 0.06). For participants at high risk of coronary heart disease recruited in general practice, the prevalence of smoking fell from baseline but did not differ between conditions.

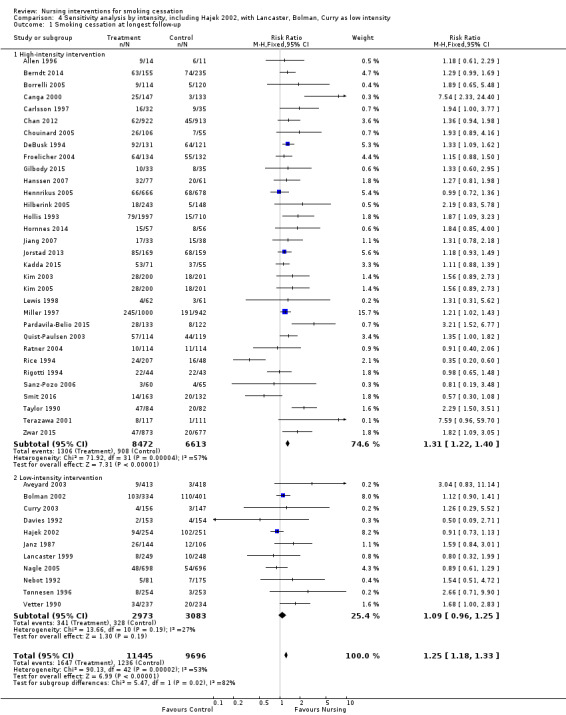

Effect of intervention intensity

We detected no evidence from our indirect comparison between subgroups that the trials we classified as using higher‐intensity interventions had larger treatment effects. In this update of the review the point estimate for the pooled effect of the seven lower‐intensity trials is effectively the same as for the 37 of higher intensity. For the low‐intensity group the confidence interval does not exclude 1, but there were fewer studies (high‐intensity subgroup RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.38, I2 = 53%, 16,865 participants, Analysis 1.1.1; low‐intensity subgroup RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.62, I2 = 36%, 4016 participants, Analysis 1.1.2). In a sensitivity analysis we included Hajek 2002, a study for which we were uncertain about the classification of the control group (as noted above in the Description of studies section), in the low‐intensity subgroup. Including this study in the low‐intensity subgroup reduced the point estimate and there was no evidence of a treatment effect (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.29). Compared to the other trials in the low‐intensity subgroup, the Hajek 2002 trial was conducted amongst hospitalized participants with cardiovascular disease and the overall quit rates were high. The large number of events gave this trial a high weight in the meta‐analysis.

The distinction between low‐ and high‐intensity subgroups was based on our categorization of the intended intervention. We particularly noted low levels of implementation in the trial reports for Lancaster 1999, Bolman 2002 and Curry 2003, so we tested the effect of moving them from the high‐ to the low‐intensity subgroup. This reduced the point estimate of effect in the low‐intensity subgroup and increased it in the high‐intensity one. If these three studies and Hajek 2002 are included in the low‐intensity subgroup, the pooled estimate of effect is small and non‐significant (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.25, 6056 participants, Analysis 4.1). We also assessed the sensitivity of the results to using additional participants in the control group for Aveyard 2003 (see Characteristics of included studies for details). This reduced the size of the effect in the low‐intensity subgroup but did not alter our conclusions.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Sensitivity analysis by intensity, including Hajek 2002, with Lancaster, Bolman, Curry as low intensity, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

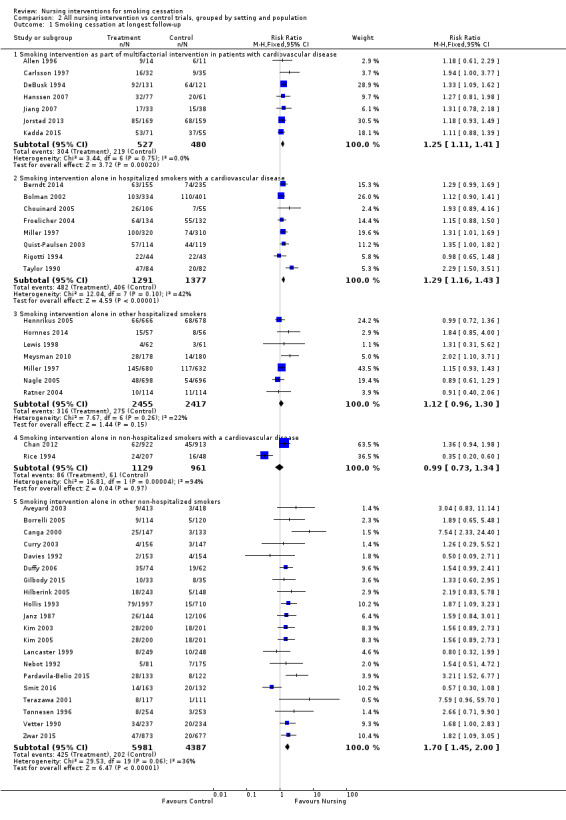

Effects of differing health states and client settings

Trials in hospitals recruited participants with health problems, but some trials specifically recruited those with cardiovascular disease, and amongst these some interventions addressed multiple risks whilst most only addressed smoking. Trials in primary care generally did not select participants with a particular health problem. We combined setting and disease diagnosis in one set of subgroups (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 All nursing intervention vs control trials, grouped by setting and population, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

Seven trials that included a smoking cessation intervention from a nurse as part of cardiac rehabilitation showed a significant pooled effect on smoking (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.41, I2 = 0%, 1007 participants, Analysis 2.1.1). Six of these (Allen 1996; Carlsson 1997; Hanssen 2007; Jiang 2007; Jorstad 2013; Kadda 2015) did not use biochemical validation of quitting, and in the seventh (DeBusk 1994) we were unable to confirm the proportion of dropouts with the study authors.

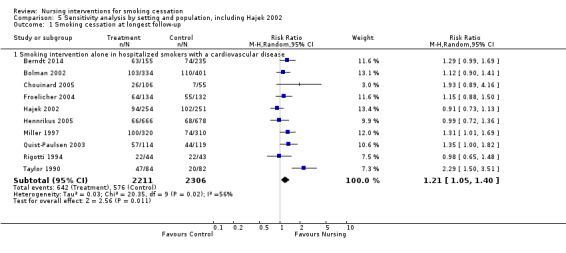

There was some heterogeneity (I2 = 42%) among eight trials of smoking‐specific interventions in hospitalized smokers with cardiovascular disease, due to the strong intervention effect in one of the eight trials (Taylor 1990). The RR was 1.29 (95% CI 1.16 to 1.43, 2668 participants, Analysis 2.1.2) and the effect remained significant if we excluded Taylor 1990 (reducing the I2 to 0%) or if we applied a random‐effects model. A sensitivity analysis of the effect of including Hajek 2002 in this category increased the heterogeneity (I2 = 56%), and the pooled effect was significant whether we used a fixed‐effect or a random‐effects model (Analysis 5.1). Excluding Taylor 1990 again removed heterogeneity but the point estimate decreased (RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.27, analysis not shown).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sensitivity analysis by setting and population, including Hajek 2002, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

Among the seven trials in non‐cardiac hospitalized smokers the risk ratio was small and the confidence interval did not exclude no effect (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.30, 4872 participants, Analysis 2.1.3). We included in this subgroup one trial that began the intervention in a pre‐admission clinic for elective surgery patients (Ratner 2004).

Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 94%) between two trials of interventions delivered to non‐hospitalized adults with cardiovascular disease (Rice 1994; Chan 2012; Analysis 2.1.4). Subgroup analysis in Rice 1994, however, suggested that smokers who had experienced cardiovascular bypass surgery were more likely to quit, and these participants were over‐represented in the control group who received advice to quit but no structured intervention.

Pooling 20 trials of cessation interventions for other non‐hospitalized adults showed an increase in the success rates (RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.45 to 2.00, 10,368 participants, Analysis 2.1.5). A sensitivity analysis testing the effect of excluding those trials (Janz 1987; Vetter 1990; Curry 2003; Hilberink 2005) where a combination of a nursing intervention and advice from a physician was used did not substantially alter this.

Higher‐ versus lower‐intensity interventions

Effects of physiological feedback

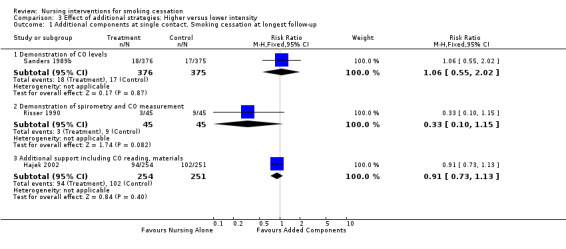

Two trials (Sanders 1989b; Risser 1990) evaluated the effect of physiological feedback as an adjunct to a nursing intervention compared to nursing without physiological feedback. Neither found any evidence of an effect at maximum follow‐up (Analysis 3.1.1 (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.55 to 2.02, 751 participants) and Analysis 3.1.2 (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.15, 90 participants)).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Effect of additional strategies: Higher versus lower intensity, Outcome 1 Additional components at single contact. Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

Effects of other components at a single contact

One trial in hospitalized smokers with cardiovascular disease (Hajek 2002) found no evidence of a significant benefit of additional support from a nurse giving additional written materials, a written quiz, an offer of a support buddy, and CO measurement compared to controls receiving brief advice and a self‐help booklet (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.13, 505 participants, Analysis 3.1.3).

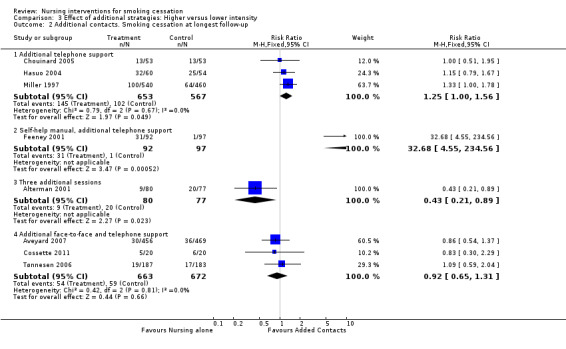

Effects of additional telephone support

There was weak evidence from pooling three trials (Miller 1997; Hasuo 2004; Chouinard 2005) that additional telephone support increased cessation compared to less or no telephone support, as the lower limit of the confidence interval was at the boundary of no effect (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.56, I2 = 0%; 1220 participants, Analysis 3.2.1).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Effect of additional strategies: Higher versus lower intensity, Outcome 2 Additional contacts. Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

Effects of additional face‐to‐face sessions

One trial of additional support from an alcohol and drug assessment unit nurse for people admitted to a coronary care unit (Feeney 2001) showed a very large benefit for the intervention (RR 32.68, 95% CI 4.55 to 234.56, 189 participants, Analysis 3.2.2). The cessation rate among the controls, however, was very low (1/97), and there was a large number of dropouts, particularly from the control group. This could have underestimated the control group quit rate. Another trial (Alterman 2001), offering four nurse sessions rather than one as an adjunct to nicotine patch, showed no benefit, with the control group having a significantly higher quit rate (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.89, 157 participants, Analysis 3.2.3). No explanation was offered for the lower than expected quit rates in the intervention group.

Effects of additional face‐to‐face sessions and telephone support

Pooled results from three trials (Tønnesen 2006; Aveyard 2007; Cossette 2011) did not show an effect of providing additional clinic sessions and telephone support compared with fewer clinic sessions and less or no telephone support (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.31, I2 = 0%, 1335 participants, Analysis 3.2.4).

Discussion

Summary of main results

The results of this meta‐analysis support a modest but positive effect for smoking cessation interventions by nurses, but we rated the quality of evidence as moderate due to unexplained statistical heterogeneity (see Table 1). A structured smoking cessation intervention delivered by a nurse was more effective than usual care on smoking abstinence at six months or longer from the start of treatment. The direction of effect was consistent in different intensities of intervention, in different settings, and in smokers with and without tobacco‐related illnesses. In a subgroup of low‐intensity studies the confidence interval did not exclude no effect, but the point estimate was effectively the same as that in the larger group of high‐intensity studies. We found insufficient evidence to assess whether more intensive interventions, those incorporating additional follow‐up, or those incorporating pathophysiological feedback are more effective than one‐off support. There was no evidence that the effect of support differed by patient group or across healthcare settings.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Overall, these meta‐analysis findings need to be interpreted carefully in light of the methodological limitations of both the review and the clinical trials. In terms of the review, it is possible that there was a publication selection bias due to using only tabulated data derived from published works (Stewart 1993). Data from the unpublished or missed studies or both could have shown more or less favorable results, although a funnel plot for the main comparison did not suggest the presence of reporting bias. For recent updates, we have also searched clinical trials registries and 'grey' literature to identify relevant unpublished studies. Secondly, finding statistical heterogeneity between the incidences of cessation in different studies limits any assumption that interventions in any clinical setting and with any type of participant are equally effective.

The findings of this review, and in particular the estimated size of the treatment effect, have remained remarkably stable since its initial publication. In 1999, 15 studies contributed to the main analysis, with a pooled risk ratio of 1.30 (95% CI 1.16 to 1.44). Further studies have more than doubled the number of participants and thus narrowed the CIs, but have had very little impact on the point estimate, which in this most recent update is the same as it was in 1999.

Effectiveness by intervention characteristics and population

The effect estimates are similar for high‐ and low‐intensity smoking cessation interventions by nurses, as was found in a review of physicians' advice (Stead 2013). Presumably, the more components added to the intervention the more intensive the intervention. However, assessing the contribution of factors such as total contact time, number of contacts, and content of the intervention was difficult. Our distinction between high and low intensity, based on the length of initial contact and number of planned follow‐ups, may not have accurately distinguished among the key elements that could have contributed to greater efficacy. We found that the nature of the smoking cessation interventions varied from advice alone, to more intensive interventions with multiple components, and that the description of what constituted 'advice only' varied. In most trials, advice was given with an emphasis on stopping smoking because of some existing health problem. To make most interventions more intensive, verbal advice was supplemented with a variety of counseling messages, including benefits of and barriers to cessation (e.g. Taylor 1990) and effective coping strategies (e.g. Allen 1996). Manuals and printed self‐help materials were also added to many interventions, along with repeated follow‐up (Hollis 1993; Miller 1997). In some studies, the proposed intervention was not delivered consistently to all participants. In recent updates the evidence for the benefit of a low‐intensity intervention has become weaker than that for a more intensive intervention, and the estimated effect is sensitive to the inclusion of one additional study (Hajek 2002) and to the classification of intensity of three studies. Almost all the intensive interventions were delivered either by dedicated project staff or by nurses with a health promotion role. Most studies in which the intensive intervention was intended to be delivered by a nurse with other roles consistently reported problems in delivering the intervention. None showed a statistically significant benefit for the intervention. We found no studies of brief opportunistic advice that were directly analogous to the low‐intensity interventions used in physician advice trials (Stead 2013).

In two studies in the low‐intensity category (Janz 1987; Vetter 1990), advice from a physician was also part of the intervention and this almost certainly contributed to the overall effect. The most highly‐weighted study in the high‐intensity subgroup (Miller 1997) produced only relatively modest results. This was due in part to the effect of the minimal treatment condition that had just one follow‐up telephone call. However, using just the high‐intensity condition in the analysis did not materially alter the pooled estimate.

One study (Miller 1997) provided data on the effect of the same intervention in smokers with different types of illness and suggested a greater effect in cardiovascular patients. In these individuals the intervention increased the 12‐month quit rate from 24% to 34%. In other types of patients, the rates were increased from 18.5% to 21%. However, this hypothesis was not formally tested. In this study participants were eligible if they had smoked any tobacco in the month prior to hospitalization, but were excluded if they had no intention of quitting (although they were also excluded if they wanted to quit on their own). These criteria may have contributed to the relatively high quit rates achieved. Also, a higher proportion of participants in the intensive treatment arm than in the minimal or usual‐care intervention arms were prescribed nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). However, the intervention was also effective in those not prescribed NRT. Those given NRT were heavier smokers (with higher levels of addiction) who achieved lower cessation rates than those who did not use NRT.

This suggests that nursing professionals may have an important 'window of opportunity' to intervene with patients in the hospital setting, or at least to introduce the notion of not resuming tobacco use upon hospital discharge. The size of the effect may be dependent on the reason for hospitalization. The additional telephone support, with the possibility of another counseling session for people who relapsed after discharge, seemed to contribute to more favorable outcomes in the intensive intervention used by Miller 1997, although pooled results from three studies testing the addition of telephone counseling and further face‐to‐face contact did not detect an effect. A separate Cochrane Review of the efficacy of interventions for hospitalized patients (Rigotti 2012) supports the efficacy of interventions for this patient group, but only when the interventions included post‐discharge support for at least one month.

Providing additional physiological feedback in the form of spirometry and demonstrated CO level as an adjunct to nursing intervention did not appear to have an effect. Three studies in primary care or outpatient settings used this approach (Sanders 1989b; Risser 1990; Hollis 1993). It was also used as part of the enhanced intervention in a study with hospitalized patients (Hajek 2002). A separate Cochrane Review (Bize 2012) found little evidence about the effects of most types of biomedical tests for risk assessment on smoking cessation.

The identification of an effect for a nurse‐mediated intervention in smokers who were not hospitalized is based on 20 studies. The largest study (Hollis 1993) increased the quit rate from 2% in those who received only advice from a physician to 4% when a nurse delivered one of three additional interventions, including a video, written materials, and a follow‐up telephone call. Control group quit rates were less than 10% in almost all these studies, and more typically between 4% and 8%. The risk ratio in this group of studies (1.7) was a little higher than in some subgroups, but because of the low background quit rate the proportion of participants likely to become long‐term quitters as a result of a nursing intervention in these settings is likely to be small. However, because of the large number of people who could be reached by nurses, the effect would be important.

Combined efforts of many types of healthcare professionals are likely to be required. The US Public Health Service clinical practice guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence (AHRQ 2008) used logistic regression to estimate efficacy for interventions delivered by different types of providers. Their analysis did not distinguish among the non‐physician medical healthcare providers, so that dentists, health counselors, and pharmacists were included with nurses. The guideline concluded that these providers were effective (Table 15, odds ratio (OR) 1.7, 95% CI 1.3 to 2.1). They also concluded that interventions by multiple clinician types were more effective (Table 16, OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.9 to 23.4). Although it was recognized that there could be confounding between the number of providers and the overall intensity of the intervention, the findings confirmed that a nursing intervention that reinforces or complements advice from physicians or other healthcare providers or both is likely to be an important component in helping smokers to quit.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Support for smoking cessation by a nurse leads to a modest improvement in tobacco abstinence. Most of these interventions were delivered by nurses with a specialist health promotion function and there was insufficient evidence to know whether general nurses can achieve the same benefits. Commissioners and providers of smoking cessation services need to consider the quality of delivery of smoking cessation services if these are to be provided by general nurses.

Implications for research.

Further studies of nursing interventions are warranted, with more careful consideration of sample size, participant selection, refusals, dropouts, long‐term follow‐up, and biochemical verification. Additionally, controlled studies are needed that carefully examine the effects of 'brief advice by nursing', as this type of professional counseling may more accurately reflect the current standard of care. Work is now required to systematize interventions so that more rigorous comparisons can be made between studies. None of the trials reviewed was a replication study; this is a very important method to strengthen the science, and should be encouraged.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 October 2017 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions unchanged |

| 26 October 2017 | New search has been performed | Searches updated. Nine new included studies |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1998 Review first published: Issue 3, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 June 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions unchanged. |

| 14 June 2013 | New search has been performed | Searches updated. Seven new included studies, and new data (longer follow‐up) added for two already included studies. |

| 22 June 2011 | Amended | Additional table converted to appendix to correct pdf format |

| 29 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 21 October 2007 | New citation required and minor changes | Updated for issue 1 2008 with 12 new studies included; no major changes to results. The conclusions did not change. |

| 14 September 2003 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Updated for issue 1 2004 with 7 new studies. Conclusions now give more emphasis to possible differences between high and low intensity interventions. |

| 14 October 2001 | New citation required and minor changes | Updated for issue 3 2001 with 3 new studies. The conclusions did not change substantially. |

Acknowledgements

Lindsay Stead was an author for previous versions of this review. Nicky Cullum and Tim Coleman for their helpful peer review comments on the original version of this review. Hitomi Kobayasha, a doctoral student, for assistance with Japanese translation of a study. Jong‐Wook Ban and Hyunjik Kim for Korean language assistance. Thank you to Olga Kadda for providing additional study data for Kadda 2015, and Harald Jorstad for providing additional study data for Jorstad 2013.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Register search strategy

Run using Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS) software

#1 (nurse* or nursing):TI,AB,XKY,MH,EMT,KY #2 (health visitor*):TI,AB,XKY,MH,EMT,KY #3 #1 OR #2

XKY, MH, EMT, KY are keyword fields. XKY field includes indexing terms added for the use of the tobacco addiction group.

Appendix 2. Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

| Abstinence | A period of being quit, i.e. stopping the use of cigarettes or other tobacco products, May be defined in various ways; see also: point prevalence abstinence; prolonged abstinence; continuous/sustained abstinence |

| Biochemical verification | Also called 'biochemical validation' or 'biochemical confirmation': A procedure for checking a tobacco user's report that he or she has not smoked or used tobacco. It can be measured by testing levels of nicotine or cotinine or other chemicals in blood, urine, or saliva, or by measuring levels of carbon monoxide in exhaled breath or in blood. |

| Bupropion | A pharmaceutical drug originally developed as an antidepressant, but now also licensed for smoking cessation; trade names Zyban, Wellbutrin (when prescribed as an antidepressant) |

| Carbon monoxide (CO) | A colourless, odourless highly poisonous gas found in tobacco smoke and in the lungs of people who have recently smoked, or (in smaller amounts) in people who have been exposed to tobacco smoke. May be used for biochemical verification of abstinence. |

| Cessation | Also called 'quitting' The goal of treatment to help people achieve abstinence from smoking or other tobacco use, also used to describe the process of changing the behaviour |

| Continuous abstinence | Also called 'sustained abstinence' A measure of cessation often used in clinical trials involving avoidance of all tobacco use since the quit day until the time the assessment is made. The definition occasionally allows for lapses. This is the most rigorous measure of abstinence |

| 'Cold Turkey' | Quitting abruptly, and/or quitting without behavioural or pharmaceutical support. |

| Craving | A very intense urge or desire [to smoke]. See: Shiffman et al 'Recommendations for the assessment of tobacco craving and withdrawal in smoking cessation trials' Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2004: 6(4): 599‐614 |

| Dopamine | A neurotransmitter in the brain which regulates mood, attention, pleasure, reward, motivation and movement |

| Efficacy | Also called 'treatment effect' or 'effect size': The difference in outcome between the experimental and control groups |

| Harm reduction | Strategies to reduce harm caused by continued tobacco/nicotine use, such as reducing the number of cigarettes smoked, or switching to different brands or products, e.g. potentially reduced exposure products (PREPs), smokeless tobacco. |

| Lapse/slip | Terms sometimes used for a return to tobacco use after a period of abstinence. A lapse or slip might be defined as a puff or two on a cigarette. This may proceed to relapse, or abstinence may be regained. Some definitions of continuous, sustained or prolonged abstinence require complete abstinence, but some allow for a limited number or duration of slips. People who lapse are very likely to relapse, but some treatments may have their effect by helping people recover from a lapse. |

| nAChR | [neural nicotinic acetylcholine receptors]: Areas in the brain which are thought to respond to nicotine, forming the basis of nicotine addiction by stimulating the overflow of dopamine |

| Nicotine | An alkaloid derived from tobacco, responsible for the psychoactive and addictive effects of smoking. |

| Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) | A smoking cessation treatment in which nicotine from tobacco is replaced for a limited period by pharmaceutical nicotine. This reduces the craving and withdrawal experienced during the initial period of abstinence while users are learning to be tobacco‐free The nicotine dose can be taken through the skin, using patches, by inhaling a spray, or by mouth using gum or lozenges. |

| Outcome | Often used to describe the result being measured in trials that is of relevance to the review. For example smoking cessation is the outcome used in reviews of ways to help smokers quit. The exact outcome in terms of the definition of abstinence and the length of time that has elapsed since the quit attempt was made may vary from trial to trial. |

| Pharmacotherapy | A treatment using pharmaceutical drugs, e.g. NRT, bupropion |

| Point prevalence abstinence (PPA) | A measure of cessation based on behaviour at a particular point in time, or during a relatively brief specified period, e.g. 24 hours, 7 days. It may include a mixture of recent and long‐term quitters. cf. prolonged abstinence, continuous abstinence |

| Prolonged abstinence | A measure of cessation which typically allows a 'grace period' following the quit date (usually of about two weeks), to allow for slips/lapses during the first few days when the effect of treatment may still be emerging. See: Hughes et al 'Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations'; Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2003: 5 (1); 13‐25 |

| Relapse | A return to regular smoking after a period of abstinence |

| Secondhand smoke | Also called passive smoking or environmental tobacco smoke [ETS] A mixture of smoke exhaled by smokers and smoke released from smouldering cigarettes, cigars, pipes, bidis, etc. The smoke mixture contains gases and particulates, including nicotine, carcinogens and toxins. |

| Self‐efficacy | The belief that one will be able to change one's behaviour, e.g. to quit smoking |

| SPC [Summary of Product Characteristics] | Advice from the manufacturers of a drug, agreed with the relevant licensing authority, to enable health professionals to prescribe and use the treatment safely and effectively. |

| Tapering | A gradual decrease in dose at the end of treatment, as an alternative to abruptly stopping treatment |

| Tar | The toxic chemicals found in cigarettes. In solid form, it is the brown, tacky residue visible in a cigarette filter and deposited in the lungs of smokers. |

| Titration | A technique of dosing at low levels at the beginning of treatment, and gradually increasing to full dose over a few days, to allow the body to get used to the drug. It is designed to limit side effects. |

| Withdrawal | A variety of behavioural, affective, cognitive and physiological symptoms, usually transient, which occur after use of an addictive drug is reduced or stopped. See: Shiffman et al 'Recommendations for the assessment of tobacco craving and withdrawal in smoking cessation trials' Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2004: 6(4): 599‐614 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. All nursing intervention vs control trials, grouped by intensity of intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | 44 | 20881 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.21, 1.38] |

| 1.1 High‐intensity intervention | 37 | 16865 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.21, 1.38] |

| 1.2 Low‐intensity intervention | 7 | 4016 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.99, 1.62] |

Comparison 2. All nursing intervention vs control trials, grouped by setting and population.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | 43 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Smoking intervention as part of multifactorial intervention in patients with cardiovascular disease | 7 | 1007 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [1.11, 1.41] |

| 1.2 Smoking intervention alone in hospitalized smokers with a cardiovascular disease | 8 | 2668 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.16, 1.43] |

| 1.3 Smoking intervention alone in other hospitalized smokers | 7 | 4872 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.96, 1.30] |

| 1.4 Smoking intervention alone in non‐hospitalized smokers with a cardiovascular disease | 2 | 2090 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.73, 1.34] |

| 1.5 Smoking intervention alone in other non‐hospitalized smokers | 20 | 10368 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.70 [1.45, 2.00] |

Comparison 3. Effect of additional strategies: Higher versus lower intensity.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Additional components at single contact. Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Demonstration of CO levels | 1 | 751 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.55, 2.02] |

| 1.2 Demonstration of spirometry and CO measurement | 1 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.10, 1.15] |

| 1.3 Additional support including CO reading, materials | 1 | 505 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.73, 1.13] |

| 2 Additional contacts. Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Additional telephone support | 3 | 1220 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [1.00, 1.56] |

| 2.2 Self‐help manual, additional telephone support | 1 | 189 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 32.68 [4.55, 234.56] |

| 2.3 Three additional sessions | 1 | 157 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.21, 0.89] |

| 2.4 Additional face‐to‐face and telephone support | 3 | 1335 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.65, 1.31] |

Comparison 4. Sensitivity analysis by intensity, including Hajek 2002, with Lancaster, Bolman, Curry as low intensity.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | 43 | 21141 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [1.18, 1.33] |

| 1.1 High‐intensity intervention | 32 | 15085 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [1.22, 1.40] |

| 1.2 Low‐intensity intervention | 11 | 6056 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.96, 1.25] |

Comparison 5. Sensitivity analysis by setting and population, including Hajek 2002.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | 10 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Smoking intervention alone in hospitalized smokers with a cardiovascular disease | 10 | 4517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.21 [1.05, 1.40] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Allen 1996.

| Methods | Country: USA (Maryland) Recruitment setting: hospital inpatients. Intervention: Prior to hospital discharge and 2 weeks post‐discharge | |

| Participants | 116 women post‐CABG. 25 smokers amongst them. Smoker defined by use of cigs in 6 months before admission Nurses provided intervention as part of their core role | |

| Interventions | 1. Multiple risk factor intervention, self‐efficacy programme: 3 sessions with nurse using AHA Active Partnership Program and a follow‐up call 2. Usual care (standard discharge teaching and physical therapy instructions) Intensity: High | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12m ('current use') Validation: none | |

| Notes | Data on number of quitters derived from percentages. Likely to include some who stopped prior to intervention | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Consenting patients were randomly assigned to receive special intervention or usual care by using a computerized schema that achieved a balanced allocation." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The nurse obtaining study consent and the participants were unaware of the group assignment at the time consent was obtained and baseline data were collected." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Similar number lost to follow‐up in both arms; dropouts counted as smokers |

Alterman 2001.

| Methods | Country: USA Recruitment setting: community volunteers, motivated to quit, cessation clinic | |

| Participants | 160 smokers (≥ 1 pack/day) in relevant arms | |

| Interventions | All received nicotine patch 21 mg 8 weeks incl weaning Medium Intensity: 4 sessions over 9 weeks, 15 ‐ 20 mins, advice and education from nurse practitioner Low Intensity: single 30‐min session with nurse, 3 videos | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12 m, not defined Validation: CO < 9 ppm, urine cotinine < 50 ng/ml | |

| Notes | No control group so not in main analysis High intensity intervention not included in review | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Urn randomization" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Rate of dropout similar in both groups; dropouts counted as smokers. Authors give 77 as ITT denominator for medium‐intensity group. N randomized of 80 used in MA. |

Aveyard 2003.

| Methods | Country: UK Recruitment setting: 65 general practices, invitation by letter | |

| Participants | 831 current smokers in relevant arms, volunteers but not selected by motivation (> 80% precontemplators) Intervention from practice nurses with 2 days training in Pro‐Change system | |

| Interventions | 1. In addition to tailored self‐help in 2., asked to make appointment to see practice nurse. Single postal reminder if no response. Up to 3 visits, at time of letters. Reinforced use of manual 2. Self‐help manual based on Transtheoretical model, maximum of 3 letters generated by expert system. No face‐to‐face contact Intensity: Low (Standard S‐H control and telephone counselling arms not used in review) | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12 m, self‐reported sustained for 6m Validation: saliva cotinine < 14.2 ng/ml | |

| Notes | Low uptake of nurse component, 20% attended 1st visit, 6% 2nd and 2% 3rd, also more withdrawals (20%) Nursing arm discontinued part‐way through recruitment. We use only the Manual (control) group recruited during 4‐arm section of trial (3/418, data from author website www.publichealth.bham.ac.uk/berg/pdf/Addiction2003.pdf, compared to 15/683 for Manual group across the entire trial). This increases apparent benefit of nurse intervention. A sensitivity analysis did not alter any findings from the MA | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Minimization was used to allocate individuals to arms to balance three predictors of smoking cessation success... Questionnaires were read optically and the data transferred automatically to the Access database that performed the minimization and controlled the contacts." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "There was no reason and no way that the clerical assistant running the database could alter the questionnaire reading schedule." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Highest withdrawal rate in nursing group (20%). Participants with missing data counted as smokers |

Aveyard 2007.

| Methods | Country: UK Recruitment: Patients from 26 GP practices; 92% volunteers in response to mailing |

|

| Participants | 925 smokers 51% women, av. age 43, 50% smoked 11 ‐ 20 cpd Interventions from practice nurses trained to give NHS smoking cessation support and manage NRT | |

| Interventions | Both interventions included 8 wks 16 mg nicotine patch

1. Basic support; 1 visit (20 ‐ 40 mins) before quit attempt, phone call on TQD, visits/phone calls at 7 ‐ 14 days and at 21 ‐ 28 days (10 ‐ 20 mins)

2. Weekly support; as 1. plus additional call at 10 days and visits at 14 and 21 days Intensity: High (for both groups) |

|