Abstract

Background

Approximately 600 million children of preschool and school age are anaemic worldwide. It is estimated that at least half of the cases are due to iron deficiency. Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with micronutrient powders (MNP) has been proposed as a feasible intervention to prevent and treat anaemia. It refers to the addition of iron alone or in combination with other vitamins and minerals in powder form, to energy‐containing foods (excluding beverages) at home or in any other place where meals are to be consumed. MNPs can be added to foods either during or after cooking or immediately before consumption without the explicit purpose of improving the flavour or colour.

Objectives

To assess the effects of point‐of‐use fortification of foods with iron‐containing MNP alone, or in combination with other vitamins and minerals on nutrition, health and development among children at preschool (24 to 59 months) and school (five to 12 years) age, compared with no intervention, a placebo or iron‐containing supplements.

Search methods

In December 2016, we searched the following databases: CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, BIOSIS, Science Citation Index, Social Science Citation Index, CINAHL, LILACS, IBECS, Popline and SciELO. We also searched two trials registers in April 2017, and contacted relevant organisations to identify ongoing and unpublished trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs trials with either individual or cluster randomisation. Participants were children aged between 24 months and 12 years at the time of intervention. For trials with children outside this age range, we included studies where we were able to disaggregate the data for children aged 24 months to 12 years, or when more than half of the participants were within the requisite age range. We included trials with apparently healthy children; however, we included studies carried out in settings where anaemia and iron deficiency are prevalent, and thus participants may have had these conditions at baseline.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the eligibility of trials against the inclusion criteria, extracted data from included trials, assessed the risk of bias of the included trials and graded the quality of the evidence.

Main results

We included 13 studies involving 5810 participants from Latin America, Africa and Asia. We excluded 38 studies and identified six ongoing/unpublished trials. All trials compared the provision of MNP for point‐of‐use fortification with no intervention or placebo. No trials compared the effects of MNP versus iron‐containing supplements (as drops, tablets or syrup).

The sample sizes in the included trials ranged from 90 to 2193 participants. Six trials included participants younger than 59 months of age only, four included only children aged 60 months or older, and three trials included children both younger and older than 59 months of age.

MNPs contained from two to 18 vitamins and minerals. The iron doses varied from 2.5 mg to 30 mg of elemental iron. Four trials reported giving 10 mg of elemental iron as sodium iron ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (NaFeEDTA), chelated ferrous sulphate or microencapsulated ferrous fumarate. Three trials gave 12.5 mg of elemental iron as microencapsulated ferrous fumarate. Three trials gave 2.5 mg or 2.86 mg of elemental iron as NaFeEDTA. One trial gave 30 mg and one trial provided 14 mg of elemental iron as microencapsulated ferrous fumarate, while one trial gave 28 mg of iron as ferrous glycine phosphate.

In comparison with receiving no intervention or a placebo, children receiving iron‐containing MNP for point‐of‐use fortification of foods had lower risk of anaemia prevalence ratio (PR) 0.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.49 to 0.88, 10 trials, 2448 children; moderate‐quality evidence) and iron deficiency (PR 0.35, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.47, 5 trials, 1364 children; moderate‐quality evidence) and had higher haemoglobin (mean difference (MD) 3.37 g/L, 95% CI 0.94 to 5.80, 11 trials, 2746 children; low‐quality evidence).

Only one trial with 115 children reported on all‐cause mortality (zero cases; low‐quality evidence). There was no effect on diarrhoea (risk ratio (RR) 0.97, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.78, 2 trials, 366 children; low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNPs containing iron reduces anaemia and iron deficiency in preschool‐ and school‐age children. However, information on mortality, morbidity, developmental outcomes and adverse effects is still scarce.

Plain language summary

Powdered vitamins and minerals added to foods at the point‐of‐use reduces anaemia and iron deficiency in preschool‐ and school‐age children

Background to the question

Approximately one billion people worldwide are deficient in at least one vitamin or mineral (also known of micronutrients). Iron, vitamin A, zinc and iodine deficiencies are very frequent among children of preschool (aged 24 months to less than 5 years) and school age (5 to 12 years of age), limiting their health and daily physical performance. Anaemia, the condition in which red blood cells have limited capacity to carry oxygen, frequently results after prolonged iron deficiency.

Point‐of‐use fortification with powdered vitamins and minerals has been proposed as a public health intervention to reduce micronutrient deficiencies in children. In this process, a powdered premix containing iron, and possibly other vitamins and minerals, is added to foods either during or after cooking, or immediately before consumption to improve their nutritious value but not their flavour or colour. In some cases, point‐of‐use fortification is also known as home fortification.

Review question

What are the effects of point‐of‐use fortification of foods with iron‐containing micronutrient powders (MNP) alone, or in combination with other vitamins and minerals, on nutrition, health and development among children of preschool and school age (24 months to 12 years of age) compared with no intervention, a placebo (dummy pill) or regular iron‐containing supplements (as drops, tablets or syrup)?

Study characteristics

This review included 13 trials with 5810 participants from Latin America, Africa and Asia. All trials compared the provision of MNP for point‐of‐use fortification with no intervention or placebo. Six trials included participants younger than 59 months of age only, four included only children aged 60 months of age or older, and three trials included children both younger and older than 59 months of age. MNPs contained from two to 18 vitamins and minerals. We searched existing clinical trials in December 2016 and ongoing trials in April 2017. We also contacted relevant institutions for additional information upon publication of the protocol and in April 2017.

Key results

The review found that children receiving iron‐containing MNP for point‐of‐use fortification of foods were at significantly lower risk of having anaemia and iron deficiency and had higher haemoglobin concentrations. We did not find any positive or negative effect on diarrhoea or mortality, but the data on these two outcomes were very limited.

Quality of the evidence

We rated the overall quality of the evidence for the provision of multiple MNP versus no intervention or placebo as moderate for anaemia, iron deficiency and adverse effects. We judged the evidence to be of low quality for haemoglobin, mortality and diarrhoea, and to be very low‐quality for ferritin. In general, the most common risk of bias in the studies was the lack of blinding for participants, personnel and outcome assessors.

Authors' conclusions

Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNPs containing iron reduces anaemia and iron deficiency in preschool‐ and school‐age children and seems feasible for public health purposes. However, future research should aim to increase the body of evidence on mortality, morbidity, developmental outcomes and adverse effects. Due to the lack of trials, we were unable to determine at this time if this intervention has comparable effects to those observed with iron supplements (provided as drops, tablets or syrup).

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with micronutrients powders (MNP) compared to no intervention or placebo in preschool and school‐age children.

| Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNP compared to no intervention or placebo in preschool and school‐age children | ||||||

|

Patient or population: preschool and school‐age children Setting: all settings Intervention: point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNP Comparison: no intervention or placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no intervention or placebo | Risk with point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNP | |||||

| Anaemia (defined as haemoglobin < 110 g/L for children aged 24‐59 months and < 115 g/L for children aged 5‐11.9 years, adjusted by altitude where appropriate)* | Study population | RR 0.66 (0.49 to 0.88) | 2448 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Included studies: Inayati 2012 (C); Kemmer 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Ogunlade 2011; Osei 2008 (C); Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C). | |

| 375 per 1000 | 247 per 1000 (184 to 330) | |||||

| Haemoglobin | The mean haemoglobin score in control groups ranged from 103.50 g/L to 128.00 g/L | The mean haemoglobin score in intervention groups was, on average, 3.37 g/L higher (0.94 g/L higher to 5.80 g/L higher) | ‐ | 2746 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | Included studies: Inayati 2012 (C); Kemmer 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Ogunlade 2011; Osei 2008 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C); Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C). |

| Iron deficiency (defined by using ferritin concentrations less than 15 µg/L) | Study population | RR 0.35 (0.27 to 0.47) | 1364 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | Included studies: Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Osei 2008 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C); Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C). | |

| 220 per 1000 | 77 per 1000 (59 to 104) | |||||

| Ferritin | 0 | The standardised mean ferritin score in intervention groups was, on average, 0.42 μg/L higher (4.36 μg/L lower to 5.19 μg/L higher) | ‐ | 1066 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd,e | Included studies: Osei 2008 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C); Varma 2007 (C). |

| All‐cause mortality (number of deaths during trial) | Study population | Not estimable | 115 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowf | Included study: Inayati 2012 (C). | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Diarrhoea (≥ 3 liquid stools per day) | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.53 to 1.78) | 366 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowg | Included studies: Inayati 2012 (C); Osei 2008 (C). | |

| 96 per 1000 | 93 per 1000 (51 to 170) | |||||

| Adverse effects (any, as defined by trialists) | Study population | RR 1.09 (0.16 to 7.42) | 90 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Included study: Orozco 2015 (C). | |

| 43 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (7 to 316) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; MNP: micronutrient powder; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aMost studies had no blinding. High heterogeneity (72%) with most studies showing a positive effect of MNP. bMost studies had no blinding. High heterogeneity (93%) with most studies showing a positive effect of MNP. cMost studies had no blinding. No heterogeneity with most studies showing a positive effect of MNP. dAll the studies had no or unclear blinding. e100% heterogeneity with most inconsistency in direction of effect. fOnly one low‐risk trial reported all‐cause mortality. gTwo low‐risk trials reported diarrhoea. No heterogeneity with both studies showing no difference between intervention and comparison group.

Background

Description of the condition

Vitamin and mineral deficiencies are highly prevalent among children of preschool (usually 24 to 59 months of age) and school‐age (five to 12 years of age), limiting their health and daily physical performance. In addition to anaemia, frequently reported micronutrient deficiencies in these age groups are those of iron, vitamin A, zinc and iodine.

Anaemia is a condition characterised by a reduction in the body's oxygen‐carrying capacity. It is estimated that over 1.6 billion people, or a quarter of the world's population, are anaemic. The prevalence of anaemia globally is 43% (range 38% to 47%) in children aged six to 59 months (Stevens 2013). Most anaemia occurs in low‐ and middle‐income countries (WHO 2015b). Causes of anaemia include iron, folate, vitamin B12 and vitamin A deficiencies; chronic inflammation; parasitic infestations and inherited blood disorders (Jimenez 2010; WHO 2001). The proportion of all anaemia amenable to iron is estimated to be 42% in children (WHO 2015b). The proportions of severe anaemia amenable to iron is estimated to be 50% for children (Stevens 2013). It is assumed to be higher (about 60%) in malaria‐free areas (Rastogi 2002; Stoltzfus 2004; WHO 2009). Iron deficiency can be caused by chronic poor dietary iron intake (in quantity and quality), together with increased iron requirements resulting from growth and from losses due to intestinal parasitic infestations and menstruation in postmenarchal girls (WHO 2001). Anaemia in children is diagnosed when the haemoglobin (Hb) concentration in the blood is below a predefined cut‐off value, which varies with age and the residential elevation (WHO 2011a). Iron deficiency anaemia is diagnosed by the combined presence of anaemia and iron deficiency, measured by ferritin or any other biomarker of iron status such as serum transferrin receptors or zinc protoporphyrin (WHO 2011b).

Iron deficiency anaemia in children of preschool and school‐age is associated with considerable morbidity. This condition appears to be associated with potentially irreversible impairment of cognitive development in preschool‐age children and with reduced learning and educational performance in school‐age children (Lozoff 2007). Iron deficiency has been estimated to contribute to 0.2% of deaths in children under five years of age, and every year approximately 2.2 million years are lost due to iron‐induced disability worldwide (measured in disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs), a measure of overall disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to ill‐health, disability or early death) (Black 2008; Stoltzfus 2004; WHO 2009).

Vitamin A is an essential nutrient that comprises a group of unsaturated organic compounds such as retinol, retinal and retinoic acid. Provitamin A carotenoids, which are produced in plants, are also a primary dietary source of vitamin A (Tanumihardjo 2016). When the intake, absorption or utilisation of vitamin A or provitamin A carotenoids is inadequate, vitamin A deficiency can occur. Vitamin A deficiency disorders include xerophthalmia and increased risk of death from infectious diseases, especially among preschool children (Tanumihardjo 2016). Vitamin A deficiency is a risk factor for blindness and for mortality from measles and diarrhoea in children (Stevens 2015). In 2013, the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency was 29% in children, mostly from in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Stevens 2015).

Zinc deficiency affects overall body metabolism and can be associated with poor growth, stunting and wasting; increased infections and the appearance of skin lesions. In countries where zinc intakes are inadequate, zinc deficiency may present as poor physical growth, impaired immune competence, reproductive dysfunction and sub optimal neurobehavioral development. This can increase risk of child morbidity and mortality, and preterm births (Brown 2009; King 2016). Some authors have estimated that zinc deficiency is responsible for about 4% of child mortality (Black 2008), and that supplementing children with this nutrient may help reduce deaths related to diarrhoea and pneumonia (Yakoob 2011). It is estimated that 29.8% (95% CI 29.4% to 30.1%) of school‐age children (approximately 241 million) have insufficient iodine intakes.

Iodine deficiency affects more than one‐third of school‐age children worldwide and results in developmental delays and other health problems (Andersson 2012). Vitamin D deficiency and folate insufficiency may also be a concern during childhood.

Folic acid, another form of which is known as folate, is one of the B vitamins. Inadequate folate intake is the main cause of folate deficiency. The use of antifolate drugs used in treatment and prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, malaria and toxoplasmosis selectively inhibit folate's actions in microbial organisms such as bacteria, protozoa and fungi. In some low‐ and middle‐income countries, malabsorptive conditions, such as tropical sprue, can also cause folate deficiency. Although essential throughout life, folate is particularly critical during early stages of human development. Folate deficiency may result in megaloblastic anaemia in which low numbers of large red blood cells occur (Bailey 2015). Among other micronutrients, current micronutrient powders (MNP) formulations generally include folic acid and there is ongoing debate on risks and benefits of the provision of supplemental folic acid through point‐of‐use fortification, especially in children living in sub‐Saharan Africa where malaria is endemic (Kupka 2015).

Vitamin D has a key role in bone metabolism (Winzenberg 2011), while adequate folate and folic acid intake is particularly important for pubescent girls who are capable of reproduction, as poor maternal folate status around the time of conception increases the risk of neural tube and other defects at birth (Mulinare 1988). Unfortunately, to date, there are insufficient data to estimate the global magnitude of inadequate folate or vitamin D status among any populations, including children.

In low‐income countries, some nutritional risk factors increase the incidence or severity of infectious diseases and contribute to a high number of deaths and loss of healthy years. Micronutrient deficiencies (iron, vitamin A and zinc), in combination with childhood underweight and sub optimal breastfeeding, cause 7% of deaths and 10% of total disease burden (WHO 2009). In 2010, globally, an estimated 27% (171 million) of children younger than five years of age were stunted and 16% (104 million) were underweight. Africa and Asia have more severe burdens of undernutrition, but the problem persists in some Latin American countries (Lutter 2011). Underweight and undernutrition particularly increase child death and disability. Due to overlapping effects, these risk factors are responsible for an estimated 3.9 million deaths (35% of total deaths) and 33% of total DALYs in children younger than five years of age. Their combined contribution to specific causes of death is highest for diarrhoeal diseases (73%) and close to 50% for pneumonia, measles and severe neonatal infections (WHO 2009).

Description of the intervention

Public health strategies to address micronutrient malnutrition include prevention of parasitic infestations and other infections; dietary diversification to improve the consumption of foods with highly absorbable vitamins and minerals; industrial fortification of staple foods; provision of supplementary foods; and provision of supplements in the form of liquids, pills and tablets (Bhutta 2008), with the latter being a widespread intervention.

There are few essential nutrition actions for preschool‐ and school‐age children (WHO 2013). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a supplemental provision of 2 mg of elemental iron per kilogram bodyweight per day for three months in children less than six years of age born at term. Children of school‐age and older should receive 30 mg of iron and 250 μg (0.25 mg) of folic acid daily for three months, particularly in populations where anaemia prevalence is greater than 40% (WHO 2001). The intermittent use of iron supplements is also recommended as a public health strategy for these age groups in settings where anaemia prevalence is higher than 20% (WHO 2011c). Both supplementation regimens have proven to be effective in reducing the risk of having anaemia and iron deficiency (De‐Regil 2011a; Gera 2007). Though the current recommendations only include iron alone or with folic acid, it has been suggested that administration of additional micronutrients may prevent or reverse anaemia derived from other nutritional deficiencies (Bhutta 2008), and also have positive effects on length or height and weight, serum zinc, serum retinol and motor development (Allen 2009). However, the long regimen duration, bad taste of liquid iron drops and syrups, adverse effects associated with daily iron supplementation (e.g. gastrointestinal discomfort, constipation and teeth staining with drops or syrups) and the limited implementation of large‐scale, intermittent iron supplementation programmes have triggered the development of new approaches to provide iron and other nutrients.

Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNP has been proposed as an alternative to oral supplements and industrially fortified foods to provide micronutrients to different age groups (Zlotkin 2001; Zlotkin 2005) and is currently recommended by the World Health Organization for infants, young children and children aged 2–12 years living in populations where anaemia is a public health problem (WHO 2016). It refers to the addition of vitamins and minerals in powder form to energy‐containing foods at home or in any other place where meals are to be consumed, such as schools, nurseries and refugee camps. MNPs can be added to foods either during or after cooking, or immediately before consumption without the explicit purpose of improving the flavour or colour. In some cases, point‐of‐use fortification is also known as home fortification.

Point‐of‐use fortification with MNP can be described as a hybrid intervention between industrial fortification of staple foods or condiments and targeted vitamin and mineral supplementation. The uniqueness of this intervention results from the mixture of advantages and disadvantages inherited from both parent interventions. Point‐of‐use fortification is similar to industrial fortification of staple foods because the vitamins and minerals are added to meals or condiments regularly consumed and usually does not require additional changes to dietary intake behaviours. Point‐of‐use fortification entails the fortification of foods immediately before consumption at home or at another point of use such as schools or child‐care facilities, and there is no long‐term interaction between micronutrients and the food that can diminish their shelf life. In industrial fortification, conversely, micronutrients are added to staple foods or condiments during industrial processing and are more prone to the potential undesirable chemical interactions over time that affect the food sensory properties as well as the bioavailability of some micronutrients (WHO/FAO 2006).

Like micronutrient supplementation, point‐of‐use fortification with MNP is targeted to specific populations so that the number and quantity of micronutrients can be tailored to meet the target groups' needs without increasing the risk of overload among other population groups. Also typical of vitamin and mineral supplementation, point‐of‐use fortification allows for flexibility in the provision regimen (e.g. daily, intermittently) (Hyder 2007), and can be adapted according to the selected delivery channel (e.g. health or school systems or social protection programmes) or context.

Both micronutrient supplementation and point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNP require active participation from the target population to achieve and sustain high coverage and regular and appropriate use, with the possible exception being the use of MNP in institutional settings, where the powder is added to the meals prior to serving them to the participants, and a lesser degree of 'active participation' may potentially be expected of participants in some settings. However, in comparison to supplementation, the addition of MNP to foods or meals may result in a higher acceptance and use among children and care‐takers as a result of the lower number of adverse effects (Zlotkin 2005), and tastelessness of the product when prepared correctly. It is still unclear whether the absorption of MNP mimics that of supplements or that of industrial fortification of staple foods.

Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNP containing at least iron, vitamin A and zinc is recommended to improve iron status and reduce anaemia among infants and children aged six to 23 months of age (WHO 2016).

How the intervention might work

MNPs were initially conceived as a way to deliver a novel iron compound, encapsulated ferrous fumarate, an iron salt covered by a thin lipid layer aimed at preventing the interaction of iron with foods. The encapsulation minimises changes caused by iron to the taste or colour in the food to which it is added (Liyanage 2002). Other iron compounds have also been tested. Micronised ferric pyrophosphate has produced a similar haematological response in children aged six to 23 months in comparison to encapsulated ferrous fumarate (Christofides 2006; Hirve 2007). More recently, sodium iron ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (NaFeEDTA) has been proposed as a more efficacious fortificant that, given in a low dose, could produce similar effects on Hb as those observed with ferrous sulphate among school‐age children, particularly when added to cereal‐based foods that are rich in inhibitors of iron absorption (Troesch 2011a). Independently of the source, the iron is frequently accompanied with other micronutrients such as zinc, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin D or folic acid, and in some cases, MNP formulations may include up to 15 vitamins and minerals. These formulations are currently developed by various manufacturers (De Pee 2008; De Pee 2009). From the packaging perspective, MNP were initially delivered in single‐dose sachets, which are lightweight and relatively simple to store and transport, and allow easier dosage control (De Pee 2008; SGHI 2008); although the disposal of non‐degradable sachets has raised some environmental concerns. Currently, the package of the MNP has been broadened to the use of bulk, multi‐serving packages from which powders are added over the meals by using measuring spoons.

The use of MNP by infants and young children aged six to 23 months has been reported to reduce the risk of anaemia and iron deficiency in settings where anaemia prevalence is higher than 20%; an effect apparently similar to that achieved by oral iron and folic acid supplements (De‐Regil 2011b; Dewey 2008). Although most of the trials have examined the provision of MNP on a daily basis, other trials suggest that providing this intervention in a flexible or intermittent regimen, and hence a lower overall monthly dose, produces the similar haematological response as daily use of MNP (Hyder 2007; Ip 2009; Sharieff 2006). The intermittent provision of iron was proposed in the 1990s as a feasible public health strategy to supplement children's and women's diets and to reduce anaemia, as it is supposed to maximise absorption by provision of iron in synchrony with the turnover of the mucosal cells (Beaton 1999; Berger 1997; Viteri 1997).

An important consideration when providing supplemental iron to children is the presence of malaria because the malaria parasite requires iron for growth, mainly circulating‐free iron (Okebe 2011). Approximately 40% of the world population is exposed to the parasite, and it is endemic in over 100 countries (WHO 2009; WHO 2010a). There were an estimated 839,000 malaria deaths worldwide in 2015 (uncertainty interval, 653,000 to 1.1 million). Of the estimated deaths, most occur in the WHO African Region (88%), followed by the WHO South‐East Asia Region (10%) and the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (2%) (WHO 2015a). Nonetheless, large reductions in the number of malaria cases and deaths have been documented between 2000 and 2015. Of all the complications associated with malaria, severe anaemia is the most common and causes the highest number of malaria‐related deaths. Although the mechanisms by which additional iron can benefit the parasite are far from clear (Prentice 2007), it has been hypothesised that the provision of iron along with foods or low doses of iron, either as encapsulated ferrous fumarate or NaFeEDTA, might help to prevent anaemia at the time of infection if it reduces the quantity of free iron (non‐transferrin‐bound iron) available to the parasite (Hurrell 2010).

In addition to malaria, another safety concern related to the use of MNPs is their possible effect on diarrhoea. One systematic review reported a slight, significant increase in the incidence of diarrhoea with MNP intake, with no significant increases in recurrent diarrhoea or upper respiratory infection (Salam 2013). Some trials have reported an increase in the number of diarrhoeal episodes after initiating the intervention, followed by a decrease in the frequency of liquid stools after few days (De‐Regil 2011b). As a preventive measure, some organisations have advocated the widespread distribution of information on the prompt detection and treatment of diarrhoea (WFP/DSM 2010). Despite these possible caveats, the use of MNP has been considered by some scientists as one of the most cost‐effective strategies to prevent vitamin and mineral malnutrition (Horton 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

The use of MNP for home or point‐of‐use fortification of complementary foods among infants and young children aged six to 23 months of age has been shown to be effective in reducing anaemia and iron deficiency in young children (De‐Regil 2011b). The initial success of this intervention has encouraged its use in other vulnerable populations, such as children of preschool (usually 24 months to less than 5 years of age) and school‐age (usually five to 12 years of age), as the distribution of MNP can potentially build on and enhance existing school‐feeding programmes in addition to other existing community‐based platforms. In 2012 to 2013, the World Food Programme (WFP) was in the process of planning or implementing MNP programmes to reach approximately 1.5 million school‐age children by adding MNP to school lunches (Martini 2013). Overall, MNP interventions have been pilot‐tested in all regions of the world for various population groups, but most often for children aged six to 23 months or six to 59 months; in 2013, 61 MNP projects were being implemented in 43 countries, and there were 16 national‐scale MNP programmes (UNICEF 2014). Projects distributing MNP in 2013 reported that they projected to reach more than 14 million participants in 2014 (UNICEF 2014). Likewise, it is also important to assess any adverse effects and potential adverse effects on health with this intervention in this age group.

To date, there is no systematic assessment of the effects of MNP provision among preschool‐ and school‐aged children to inform policy‐making.

This review will complement the findings of other systematic reviews, which explored the effects of point‐of‐use fortification with multiple MNP in children younger than two years of age (De‐Regil 2011b) and among pregnant women (Suchdev 2015).

Objectives

To assess the effects of point‐of‐use fortification of foods with iron‐containing MNP alone, or in combination with other vitamins and minerals on nutrition, health and development among children at preschool (24 to 59 months) and school (five to 12 years) age, compared with no intervention, a placebo or iron‐containing supplements.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs with randomisation at either individual or cluster level. Quasi‐RCTs are trials that use systematic methods to allocate participants to treatment groups such as alternation, assignment based on date of birth or case record number (Lefebvre 2011). We found no RCTs that met our inclusion criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review). We included no other types of evidence (e.g. cohort or case‐control studies) in this review, but we considered such evidence in the Discussion, where relevant.

Types of participants

We included trials aimed at children aged 24 months (two years) to 59 months (less than five years of age) and five to 12 years of age at the time of receiving the intervention with the MNP. We did not include trials specifically targeting hospitalised children with clinical conditions, HIV‐associated infections or enterally fed children.

We defined school age as that between five and 12 years of age. Although many children do not attend schools, these ages are compulsory school years in most settings, providing with it an entry point to address the nutritional needs of this age group (Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity 2016). We acknowledge the overlap between this age range and the one used for adolescent age, 10 to 19 years of age (WHO 2003), and made a pragmatic decision based on the most suitable delivery platform.

We included trials carried out in settings where anaemia and iron deficiency were prevalent; thus participants could be anaemic or not. We also included trials for which the results for children aged between 24 and less than five years of age and five to 12 years of age could be extracted separately, or in which more than half of the participants fulfilled this criterion (we performed a Sensitivity analysis if marginal decisions were made).

Types of interventions

Interventions involved the provision of MNP for point‐of‐use fortification given at any dose, frequency and duration. The comparison groups included no intervention, placebo or usual supplementation. Specifically, we assessed the evidence on the following comparisons.

Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNP versus no intervention or placebo.

Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNP versus iron‐only supplement.

Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNP versus iron and folic acid supplements.

Point‐of‐use fortification of foods with MNP versus same micronutrients in supplements.

We included interventions that combined MNP with co‐interventions, such as education, vitamin A supplementation programmes, zinc for the treatment of diarrhoea or other approaches, but only if the co‐interventions were the same in both the intervention and comparison groups. We excluded trials examining supplementary food‐based interventions (lipid‐based supplements, chewable tablets, fortified complementary foods and other industrially fortified foods).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Anaemia (defined as Hb lower than 110 g/L for children aged 24 to 59 months and lower than 115 g/L for children aged five to 11.9 years, adjusted by altitude where appropriate).*

Hb (in grams per litre).*

Iron deficiency (defined by using ferritin concentrations less than 15 µg/L).*

Ferritin (in micrograms per litre).*

All‐cause mortality (number of deaths during the trial).*

Diarrhoea (three liquid stools or more per day).*

Adverse effects (any, as defined by trialists).

We considered outcomes marked by an asterisk (*) as critical for decision making by a panel of experts and included them in the 'Summary of findings' tables (Guyatt 2011; Peña‐Rosas 2012).

Secondary outcomes

Iron deficiency anaemia (defined by the presence of anaemia plus iron deficiency, diagnosed with an indicator of iron status as selected by trialists).

Cognitive development and school performance (as defined by trialists).

Motor development and physical capacity (as defined by trialists).

All‐cause morbidity (number of participants with at least one episode of any disease during the trial).

Acute respiratory infection (as defined by trialists; e.g. pneumonia, bronchiolitis or bronchitis).

Growth (height‐for‐age Z‐score (HAZ)).

Growth (weight‐for‐age Z‐score (WAZ)).

Growth (weight‐for‐height Z‐score (WHZ)).

Adherence (percentage of children who consumed more than 70% of the expected doses over the intervention period).

Red blood cell folate (in milligrams per decilitre).

Serum/plasma retinol (in millimoles per litre).

Serum/plasma zinc concentrations (in millimoles per litre).

We intended to group the outcomes by time points as follows, if these follow‐up data were reported for the above outcomes: immediately postintervention, one to six months postintervention, and seven to 12 months postintervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the electronic databases and trial registers listed below in December 2016 and April 2017. MNP formulations were introduced after 2000, therefore, we limited the searches by publication year from 2000 onwards. There were no language limits.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials CRSO (CENTRAL; searched 7 December 2016).

MEDLINE Ovid (2000 to 6 December 2016).

Embase Ovid (2000 to 6 December 2016).

BIOSIS ISI (2000 to 6 December 2016).

Social Citation Index Web of Science (SCI; 2000 to 7 December 2016).

Social Science Citation Index Web of Science (SSCI; 2000 to 7 December 2016).

CINAHL Plus EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 2000 to 7 December 2016).

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database; lilacs.bvsalud.org/en; 2000 to 15 December 2016).

IBECS (ibecs.isciii.es; 2000 to 15 December 2016).

POPLINE (www.popline.org; 2000 to 15 December 2016).

SciELO (Scientific Library Online; www.scielo.br; 2000 to 15 December 2016).

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 19 April 2017).

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp/en; searched 13 April 2017).

Searching other resources

We contacted authors and known experts for assistance in identifying ongoing studies or unpublished data on 21 June 2014 and again on 19 April 2017. We also contacted the regional offices of WHO; the WHO Departments of Nutrition for Health and Development, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF); the WFP; Nutrition International (formerly Micronutrient Initiative); Helen Keller International (HKI); Home Fortification Technical Advisory Group (HF‐TAG); the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN); the US Agency for International Development; and Sight and Life.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (LD‐R and MJ) independently screened all titles and abstracts retrieved by the electronic searches for eligibility. One review author (LD‐R) searched the additional sources. Each review author independently assessed two‐thirds of the full‐text reports for inclusion according to the above criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review); we assessed each paper in duplicate, resolving any disagreements through discussion.

If trials were published only as abstracts, or study reports contained little information on methods, we attempted to contact the authors to obtain further details of study design and results.

We recorded our decisions in a study flow diagram (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

For eligible trials, two review authors (MJ and JP‐R) independently extracted data using a form designed for this review. The data collection form was adapted from a similar review in a different population group (De‐Regil 2011b), and piloted by MJ and JP‐R on two included studies, before finalised for use in this review. MJ extracted data from half of the trials and JP‐R extracted data from the other half. LD‐R extracted data from all the trials. LD‐R entered data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014), and the review author who extracted the data in duplicate checked LD‐R's data entry for accuracy. We resolved any discrepancies through discussion and documented the process.

We completed the data collection form electronically and recorded information on the following.

Trial methods

Study design.

Unit and method of allocation.

Method of sequence generation.

Masking of participants, personnel and outcome assessors.

Participants

Location of the study.

Sample size.

Age.

Sex.

Socioeconomic status (as defined by trialists and where such information was available).

Baseline prevalence of anaemia.

Baseline prevalence of soil helminths.

Baseline malaria prevalence.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Intervention

Dose.

Type of iron compound.

Provision of MNP regimen.

Duration of the intervention.

Cointervention.

Comparison group

No intervention.

Placebo.

Provision of iron supplements.

Outcomes

Primary and secondary outcomes outlined under Types of outcome measures.

Exclusion of participants after randomisation and proportion of losses at follow‐up.

We recorded both prespecified and non‐prespecified outcomes, although we did not use the latter to underpin the conclusions of the review.

When information regarding any of the trials was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details. If there was insufficient information for us to be able to assess risk of bias, we categorised trials as awaiting assessment, until further information is published or made available to us.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (LD‐R and MJ) independently assessed the risk of bias of each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). Both review authors assigned each study a rating of low, high or unclear risk of bias, for the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other potential sources of bias; we also assessed the overall risk of bias. We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third review author (JP‐R).

Random sequence generation (checking for selection bias)

We described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it produced comparable groups.

Low risk of bias: any truly random process; for example, random number table, computer random number generator.

High risk of bias: any non‐random process; for example, odd or even date of birth, hospital or clinic record number.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias.

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to determine whether intervention allocations could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment.

Low risk of bias: for example, telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes.

High risk of bias: open random allocation, unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias.

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described all measures used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received.

Low risk of bias: neither participants nor personnel giving the intervention were aware of the intervention.

High risk of bias: either participants or personnel were aware of the intervention.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias.

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described all measures used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge as to which intervention a participant received.

Low risk of bias: blinding of outcomes, which is unlikely to have been broken.

High risk of bias: for example, no blinding of outcome assessment where measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding, or where blinding could have been broken.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We assessed outcomes in each included study as follows.

Low risk of bias: either there were no missing outcome data or the missing outcome data were unlikely to bias the results based on the following considerations: study authors provided transparent documentation of participant flow throughout the study, the proportion of missing data was similar in the intervention and control groups, the reasons for missing data were provided and balanced across intervention and control groups, the reasons for missing data were not likely to bias the results (for example, moving house).

High risk of bias: missing outcome data were likely to bias the results. Trials also received this rating if an 'as‐treated (per protocol)' analysis was performed with substantial differences between the intervention received and that assigned at randomisation, or if potentially inappropriate methods for imputation had been used.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias.

Selective reporting (checking for possible reporting bias)

We stated how the possibility of selective outcome reporting was examined and what was found.

Low risk of bias: where it was clear that all the study's prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review were reported.

High risk of bias: where not all the study's prespecified outcomes were reported, one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified, outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used, the study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias.

Other bias (checking for other potential sources of bias not covered by the domains above)

We assessed if the study was free of other potential bias as follows.

Low risk of bias: where there was similarity between the outcome measure at baseline, similarity between potential confounding variables at baseline, or adequate protection of study arms against contamination.

High risk of bias: where there was no similarity between outcome measure at baseline, similarity between potential confounding variables at baseline or adequate protection of study arms against contamination.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias.

Overall risk of bias

We summarised the overall risk of bias at two levels: within trials (across domains) and across trials.

Overall risk of bias within trials

For the assessment within trials, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias in each of the 'Risk of bias' domains and whether we considered they were likely to impact on the findings. We considered trials at high risk of bias if they had poor or unclear allocation concealment and either inadequate blinding of both participants and personnel or high/imbalanced losses to follow‐up. We explored the impact of the level of bias through a Sensitivity analysis.

Overall risk of bias between trials

For the assessment across trials, we set out the main findings of the review in the 'Summary of findings' table, prepared using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT 2015). We listed the primary outcomes for each comparison, with estimates of relative effects, along with the number of participants and trials contributing data for those outcomes. For each individual outcome, we assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach (Balshem 2011), which involved consideration of within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias, and resulted in one out of four levels of quality (high, moderate, low or very low). This assessment was limited only to the trials included in this review.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as prevalence ratio (PR) or risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials.

We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI to combine trials that measured the same outcome but used different measurement methods.

Rates

For rates, if they represented events that could have occurred more than once per participant, we reported the rate difference using the methodologies described in Deeks 2011.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

Where we identified both cluster‐randomised trials and individually randomised trials reporting data for the same outcome, we considered that it was reasonable to combine the results from both if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs, and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered unlikely.

Cluster‐randomised trials are labelled with a '(C)'. Inayati 2012 (C) took into account the clustering effect by using a mixed‐effects model.

Where possible, we estimated the intra cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) from trials' original data sets and reported the design effect. On the basis of this information, we used the methods set out in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to calculate the adjusted sample sizes (Higgins 2011b). We estimated the ICC from original data provided by Lundeen 2010 (C) and imputed the ICC in seven other trials (Kemmer 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C); Osei 2008 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C); Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)), and then calculated each trial's effective sample size.

Trials with more than two treatment groups

For trials with more than two intervention groups (multi‐arm trials), we included the directly relevant arms only. If we identified trials with various relevant arms, we combined the groups into a single, pair‐wise comparison (Higgins 2011b), and included the disaggregated data in the corresponding subgroup category. If the control group was shared by two or more study arms, we divided the control group (events and total population) equally by the number of relevant subgroup categories to avoid double counting the participants. We noted the details in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Two trials included additional arms in the comparisons as they provided weekly and daily regimens (Kounnavong 2011 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C)).

Cross‐over trials

There were no cross‐over trials that met our inclusion criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review). See Table 2 and our protocol (De‐Regil 2012), for methods for managing cross‐over trials archived for use in future updates of this review.

1. Unused methods archived for use in future updates of this review.

| Method | Approach |

| Unit of analysis issues |

Cross‐over trials We planned to only include the first period of a randomised cross‐over trial prior to the washout period or to a change in the sequence of treatments. We planned to treat them as parallel randomised controlled trials. |

Dealing with missing data

Missing participants

We noted dropout for each included study. We noted attrition on the 'Risk of bias' form and included it in the 'Risk of bias' summary. We conducted analysis on an available‐case analysis basis: we included data from those participants whose results were known. We considered attrition as a potential source of heterogeneity.

We attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. We contacted the authors and asked them to provide additional information and we performed an available‐case analysis and discussed the extent to which the missing data could alter the results or conclusions (or both) of the review. We noted in the Description of studies when authors provided additional information.

Missing data

Where key data (e.g. standard deviations (SD)) were missing from the report, we attempted to contact the corresponding authors (or other authors if necessary) of the included trials to request the unreported data. If this information was not achievable, we did not impute it and noted that the study did not provide data for that particular outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed methodological heterogeneity by examining the methodological characteristics and risk of bias of the trials, and clinical heterogeneity by examining the similarity between the types of participants, interventions and outcomes.

For statistical heterogeneity, we examined the forest plots from meta‐analyses to look for heterogeneity among trials and used the I2 statistic, Tau2 and Chi2 test to quantify the level of heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. If we identified moderate or substantial heterogeneity, we explored it by prespecified subgroup analysis (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). We considered an I2 statistic greater than 50% to indicate substantial heterogeneity. We advise caution in the interpretation of analyses with high degrees of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias (see 'Selective reporting bias' under Assessment of risk of bias in included studies), we attempted to contact study authors, asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such trials in the overall assessment of results by conducting a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis).

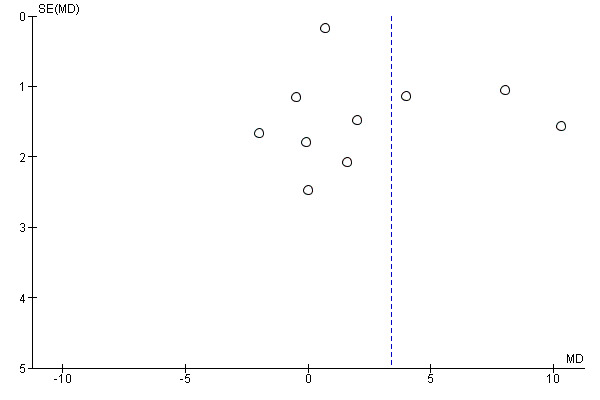

If more than 10 trials contributed data to the primary outcomes, we presented a funnel plot to evaluate asymmetry, and hence a possible indication of publication bias for primary outcomes. Any identified asymmetry could be due to publication bias, but could also be attributable to a real relationship between trial size and effect size (e.g. larger trials may have poorer participant supervision and thus compliance to supplementation, which may, in turn, influence effect size). In such a case, we included, in the Discussion, a section on the possible causes of the observed asymmetry, including descriptions of reported compliance in the larger trials as compared with smaller trials.

Data synthesis

We conducted a meta‐analysis to obtain an overall estimate of the effect of the treatment when more than one study had examined similar interventions using similar methods, been conducted in similar populations and measured similar (comparable) outcomes.

We accounted for heterogeneity using a random‐effects meta‐analysis for combining data, as we anticipated that there may be natural heterogeneity between trials attributable to the different doses, durations, populations and implementation or delivery strategies. We carried out the meta‐analysis using the inverse‐variance statistical method for continuous variables and the Mantel‐Haenszel statistical method for dichotomous variables (RevMan 2014).

We did not combine outcomes expressed as continuous or dichotomous measures.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where data were available, we carried out the following subgroup analyses:

anaemic status of participants at the start of intervention (anaemia defined as Hb values less than 110 g/L or less than 115 g/L, adjusted by altitude if appropriate): anaemic, non‐anaemic, mixed/unknown;

age of children at the start of the intervention: 24 to 59 months, five to 12 years;

refugee status: yes, no;

malaria status of the study site at the time of the trial: yes, no, not reported;

frequency: daily, weekly, flexible;

duration of intervention: less than three months, three months or more;

iron content of product: 12.5 mg or less, more than 12.5 mg;

type of iron compound: as reported by the trialists; and

number of nutrients accompanying iron: one to four, five to nine, 10 or more.

We conducted the following, post hoc subgroup analysis:

micronutrient composition: iron alone, at least iron plus vitamin A plus zinc, other combinations without bundling iron plus vitamin A plus zinc.

We used only the primary outcomes in the subgroup analysis (Primary outcomes). We did not conduct subgroup analyses for outcomes with three or fewer trials. We explored the forest plots visually and identified where CI did not overlap to identify differences between subgroup categories. We also formally investigated differences between two or more subgroups (Borenstein 2009).

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out a sensitivity analysis to explore:

the effects of removing trials at high risk of bias (trials with poor or unclear allocation concealment and blinding on either domain (i.e. both participants and personnel) or high/imbalanced loss to follow‐up) from the analysis;

the effects of different ICC values for cluster trials (where these were included, see Unit of analysis issues); and

trials with mixed populations in which marginal decisions were made (i.e. when trials included populations with an age range broader than that of our inclusion criterion: Criteria for considering studies for this review).

We conducted the following, post‐hoc sensitivity analysis:

the effects of combining studies comparing the intervention versus no intervention or placebo.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Figure 1 depicts the process for assessing and selecting trials for inclusion in this review. The search strategy identified 12,437 records for possible inclusion and 10,477 were available after duplicate records were removed. We assessed 81 full‐text reports corresponding to 57 studies for eligibility. We included 13 trials (17 reports) in the review, excluded 38 trials (57 reports) with reasons (Characteristics of excluded studies table), and identified six ongoing or unpublished trials (ACTRN12616001245482; NCT01917032; NCT02280330; NCT02302729; NCT02422953; PACTR201607001693286).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 13 trials with 5810 participants. All included trials contributed data to the review but some trials randomised participants to intervention arms that were not relevant to the comparisons we assessed. We have indicated in the Characteristics of included studies tables if we did not include any randomised arms in the analyses. Nine out of 12 trials were randomised at cluster level (labelled with a '(C)'), and for them, we have only included the estimated effective sample size in the analysis, after adjusting the data to account for the clustering effect.

In addition to the published papers, abstracts and reports identified by the search, one trial author provided us with the original data sets, for us to analyse the results for children aged 24 months and older only (Lundeen 2010 (C). Additionally, we obtained additional information on the studies for various included studies (Inayati 2012 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Ogunlade 2011; Sharieff 2006 (C); Troesch 2011b), and obtained useful information for the description of the study or the 'Risk of bias' assessment. This is presented in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Settings

All 13 trials were published after 2005, with four taking place in India (Osei 2008 (C); Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)) and four in other parts of Asia: Indonesia (Inayati 2012 (C)), Lao People's Democratic Republic (Kounnavong 2011 (C)), Kyrgyz Republic (Lundeen 2010 (C)), and China (Sharieff 2006 (C)). Two trials each were carried out in South Africa (Ogunlade 2011; Troesch 2011b) and Kenya (Macharia‐Mutie 2012), while one study each was conducted in Honduras (Kemmer 2012 (C)) and Colombia (Orozco 2015 (C)).

Nine trials took place in institutional settings with eight occurring in schools (Ogunlade 2011; Orozco 2015 (C); Osei 2008 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C); Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)) and one in a feeding centre (Macharia‐Mutie 2012). The remaining trials took place in communities.

Three trials reported to be conducted in areas where malaria is endemic (Kounnavong 2011 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Varma 2007 (C)).

We have indicated in the Characteristics of included studies table the reported baseline prevalence of anaemia, which varied substantially across the trials that provided this information (range 7.3% to 92% among the nine trials reporting these data that did not exclude participants with anaemia).

Participants

Among the 13 trials, the sample sizes ranged between 90 and 2193 participants, and included children from six months up to 15 years of age. Six trials only included children up to 59 months of age (Inayati 2012 (C); Kemmer 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Orozco 2015 (C)), while four trials included only children aged five years or older (Osei 2008 (C); Troesch 2011b; Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)), and three trials included children both younger and older than 59 months of age (Ogunlade 2011; Sharieff 2006 (C); Varma 2007 (C)). Eleven trials included boys and girls; two trials did not report the sex of the participants (Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)).

Seven trials excluded children with low Hb values (cut‐offs varied and ranged from 70 g/L to 110 g/L or lower) (Kounnavong 2011 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Orozco 2015 (C); Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)), while the study in Honduras included only non‐anaemic children (Kemmer 2012 (C)). Overall, the participants in these trials came from low‐ and middle‐income populations, with the authors of seven trials reporting that participants were of low socioeconomic status (Inayati 2012 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Ogunlade 2011; Orozco 2015 (C); Troesch 2011b; Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)), and three trials describing the participants as living in rural agricultural communities (Kemmer 2012 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Osei 2008 (C)). In two trials, the authors mentioned that some (Kounnavong 2011 (C)) or all (Sharieff 2006 (C)) participants were relatively wealthy, based on household characteristics such as being able to pay school fees or having electricity, an improved water source and a latrine.

Comparisons

All included trials compared the provision of MNP versus no intervention or placebo and are therefore included in comparison 1. None of the trials contributed data to any other comparison.

Micronutrient powder composition, iron dose and regimen

As described in the Characteristics of included studies tables, there was little consistency in MNP composition across most trials. Three trials reported a formulation of 14 vitamins and minerals (Inayati 2012 (C); Orozco 2015 (C); Osei 2008 (C)), two trials reported a formulation with six vitamins and minerals (Kemmer 2012 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C)), and each of the remaining trials reported a different formulation (range of two to 18 vitamin and minerals).

The iron dose and type of iron compound also varied across trials. Four trials reported giving 10 mg of elemental iron either as NaFeEDTA (Osei 2008 (C)), chelated ferrous sulphate (Vinodkumar 2006 (C)), or microencapsulated ferrous fumarate (Inayati 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C)). Three trials gave 12.5 mg of elemental iron as microencapsulated ferrous fumarate (Kemmer 2012 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Orozco 2015 (C)). Three trials gave 2.5 mg of elemental iron (Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Troesch 2011b) or 2.86 mg of elemental iron (Ogunlade 2011) as NaFeEDTA. Two trials gave 30 mg of elemental iron (Sharieff 2006 (C)) or 14 mg of elemental iron (Varma 2007 (C)) as microencapsulated ferrous fumarate, while one trial gave 28 mg of elemental iron as ferrous glycine phosphate (Vinodkumar 2009 (C)). Overall, seven trials used encapsulated ferrous fumarate (Inayati 2012 (C); Kemmer 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C), Orozco 2015 (C), Sharieff 2006 (C), Varma 2007 (C)); four trials used iron as ferric sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate (NaFeEDTA) (Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Ogunlade 2011, Osei 2008 (C), Troesch 2011b), one trial used chelated ferrous sulphate (Vinodkumar 2006 (C)), one trial used ferrous glycine phosphate (Vinodkumar 2009 (C)).

All trials included daily provision of MNP in at least one arm of the study. However, for seven trials carried out in school settings, daily was defined variably as five or six times a week when school was in session (Ogunlade 2011; Orozco 2015 (C); Osei 2008 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C); Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)). Two trials also included arms with intermittent use, providing MNPs either once or twice a week (Kounnavong 2011 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C)). The study duration ranged from eight weeks to 12 months, with four trials reporting a duration of 23 or 24 weeks (six months) (Kounnavong 2011 (C); Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)), and two trials reporting a duration of four months (Kemmer 2012 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012), with the remaining trials each reporting a different duration. For one trial, duration varied for each participant depending on whether they achieved a WHZ score of ‐1.0 or greater during the intervention period and were discharged (Inayati 2012 (C)). The most common co‐intervention was antihelminthic treatment, reported by nine trials (Kemmer 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Ogunlade 2011; Orozco 2015 (C); Osei 2008 (C); Troesch 2011b; Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)). One trial also gave vitamin A supplementation (Kounnavong 2011 (C)), and one trial also provided a sweet or juice after carrying out assessments (Osei 2008 (C)).

Excluded studies

We excluded 38 studies (57 reports and two personal communications). The age of the participants was outside the scope of this review in 21 trials (Aboud 2011; Ahmed 2003; Geltman 2009; Hirve 2007; Ip 2009; Jack 2012; Jaeggi 2015; Khan 2014; Menon 2007; Neufeld 2008; Samadpour 2011; Smuts 2005; Soofi 2013; Suchdev 2007 (C); Teshome 2017; Troesch 2009; Wijaya‐Erhardt 2007; Zlotkin 2001; Zlotkin 2003a; Zlotkin 2003b; Zlotkin 2013). In 18 trials, the participants were less than 24 months old (Aboud 2011; Geltman 2009; Hirve 2007; Ip 2009; Jack 2012; Jaeggi 2015; Khan 2014; Menon 2007; Neufeld 2008; Samadpour 2011; Smuts 2005; Soofi 2013; Suchdev 2007 (C); Wijaya‐Erhardt 2007; Zlotkin 2001; Zlotkin 2003a; Zlotkin 2003b; Zlotkin 2013). In two trials, children were aged 12 to 59 months but 51% of the participants were aged between 12 and 23 months (Ahmed 2003; Teshome 2017). One trial was conducted on healthy, non‐pregnant, non‐lactating young women (Troesch 2009).

In eight trials, the interventions did not evaluate MNP‐containing iron. One trial evaluated the effect of iron drops and not powders for point‐of‐use fortification (Bagni 2009 (C)), while two trials involved a fortified condiment or seasoning in powder form and not a MNP for point‐of‐use fortification (Chen 2008; Manger 2008). Three trials evaluated the effects of zinc and placebo tablets dissolved in freshly prepared fruit juice and administered to the children every day (Kikafunda 1998); the effects of four powdered fortificants added to a base powder containing protein 8 g, sugar 12 g and maltodextrin 4 g to be dissolved in 100 mL of a soy‐based fruit drink (Osendarp 2007); or the effects of synthetic β‐carotene powder added to rice (Vuong 2002). Two trials were of ineligible interventions (Menon 2016; Rim 2008). From these, one study assessed the effects of behaviour‐change interventions in Bangladesh, where half of the sample were offered MNP sachets containing iron, folic acid, zinc, and vitamins A and C for sale to mothers (Menon 2016).

Six studies had types of study design other than RCT (Angdembe 2015; Clarke 2015; De Pee 2007; Huamán‐Espino 2012; Paganini 2016; Rah 2012). One trial described the post‐tsunami experience with distribution of Vitalita sprinkles in Aceh and Nias, Indonesia, and did not have a control group (De Pee 2007), and two involved cross‐sectional surveys (Angdembe 2015; Clarke 2015). One of these references was a literature review of the effects of iron‐fortified foods, including in‐home iron fortification of complementary foods using MNP in gut microbiome (Paganini 2016).

One registered study aimed to find out whether adding a small quantity of powdered beef liver to day‐care meals of Brazilian preschool children from Salvador for 12 months could prevent anaemia and micronutrient deficiencies, and improve their growth, health and development in the same way (or better), than adding a small quantity of MNP (Sprinkles) (Gibson 2010). However, the study was not conducted because the baseline micronutrient survey data showed no evidence of micronutrient deficiencies among the preschool‐age children.

Two studies had ineligible comparison types (Sampaio 2013; Selva Suárez 2011).

See the Characteristics of excluded studies table for a detailed description of the trials and the reasons for their exclusion.

Ongoing studies

We identified six ongoing studies (ACTRN12616001245482; NCT01917032; NCT02280330; NCT02302729; NCT02422953; PACTR201607001693286). The studies are being conducted in Colombia (NCT01917032), Guatemala (NCT02302729), Pakistan (NCT02422953), Philippines (NCT02280330), Tanzania (PACTR201607001693286), and Vietnam (ACTRN12616001245482). Most studies are being conducted in children of different age ranges: six to 12 months of age and preschool‐age children (36 to 48 months of age) (NCT02302729); healthy boys and girls aged four to six years (NCT02280330), children aged six to 59 months with moderate anaemia (Hb concentration 70 g/L to 100 g/L) (PACTR201607001693286), non‐anaemic children aged five to 59 months (NCT01917032), and healthy primary school boys and girls aged six to nine years (ACTRN12616001245482). One study is on pregnant women, lactating mothers and children aged six to 59 months (NCT02422953). See Characteristics of ongoing studies table for details.

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, study methods were not well described in many of the included trials. However, we contacted all study authors and obtained a very high response rate: 83.3% of study authors provided additional information that improved the quality of our assessment (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). All provided clarifications are noted in the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

In total, we judged nine out of 13 studies at low risk of bias (Inayati 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Ogunlade 2011; Orozco 2015 (C); Osei 2008 (C); Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C)).

Allocation

Sequence generation

In four trials, the method for generation of random sequence was unclear (Kemmer 2012 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C); Troesch 2011b; Vinodkumar 2009 (C)). We judged the remaining nine trials at low risk of bias on this domain. Inayati 2012 (C); Varma 2007 (C); and Vinodkumar 2006 (C) used random tables for sequence generation. Kounnavong 2011 (C) and Ogunlade 2011 used computer‐generated random numbers. Lundeen 2010 (C) and Osei 2008 (C) used shuffling cards to generate the random sequence. Orozco 2015 (C) reported using random blocks of variable length. Macharia‐Mutie 2012 used block randomisation by age and sex generated with Excel (Microsoft) by one investigator not involved in recruitment and data collection.

Allocation concealment

In one trial, allocation concealment was unclear (Sharieff 2006 (C)), while another did not conceal allocation and thus was rated at high risk of bias (Kounnavong 2011 (C)). We judged the remaining 11 trials at low risk of bias (Inayati 2012 (C); Kemmer 2012 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Ogunlade 2011; Orozco 2015 (C); Osei 2008 (C); Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C))

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

One trial had unclear blinding of participants (Orozco 2015 (C). We rated eight trials at high risk of bias as they did not blind the intervention to the participants and personnel (Inayati 2012 (C); Kemmer 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Sharieff 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)). We judged the remaining four trials at low risk of bias (Ogunlade 2011: Osei 2008 (C); Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C)).

Blinding of outcome assessors

Five trials had unclear blinding of outcome assessment (Kemmer 2012 (C); Osei 2008 (C); Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)). Five trials did not blind the intervention and were at high risk of bias (Inayati 2012 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Sharieff 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C)). We judged the three remaining trials at low risk of detection bias (Kounnavong 2011 (C); Ogunlade 2011; Orozco 2015 (C)).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged that trials with more than 20% loss to follow‐up, or with imbalanced loss to follow‐up in different arms of trials, were inadequate in terms of completeness of outcome data. Three trials were at high levels of attrition, or loss was not balanced across groups and may have occurred for reasons associated with treatment (Kemmer 2012 (C); Ogunlade 2011; Varma 2007 (C)). With Kemmer 2012 (C), 31% of participants did not have Hb measurements. In Ogunlade 2011, attrition of the intervention group was 17.1% while attrition in the control group was 9.3%. For Varma 2007 (C), both intervention and control arms had 20% or more loss to follow‐up.

We judged the remaining 10 trials at low risk of attrition bias (Inayati 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Orozco 2015 (C); Osei 2008 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C); Troesch 2011b; Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)).

Selective reporting

In 11 trials, it was impossible to judge selective reporting (Kemmer 2012 (C); Kounnavong 2011 (C); Lundeen 2010 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Orozco 2015 (C), Osei 2008 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C); Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)). One trial had a high risk of bias because they excluded from analysis children with adherence lower than 60% (Ogunlade 2011). We judged one study at low risk of reporting bias (Inayati 2012 (C)).

Other potential sources of bias

We rated three studies at high risk of other potential sources of bias (Kounnavong 2011 (C); Orozco 2015 (C); Vinodkumar 2009 (C)). Kounnavong 2011 (C) and Vinodkumar 2009 (C) had imbalanced Hb levels among intervention and control arms at baseline. Orozco 2015 (C) reported that, at the start of the study, the overall mean age of preschool‐age children was 4.8 years (SD 0.3), with a minimum age of 3.8 years and a maximum age of 5.2 years, with statistical differences between the two groups. Also, 71.1% of participants presented an adequate nutritional status, compared to 25.6% who had malnutrition due to excess (15.6% were overweight and 10% were obese). There were significant differences in the nutritional status between the groups at the beginning of the study.

With the remainder of the trials, there was insufficient information to permit judgement (Inayati 2012 (C); Kemmer 2012 (C); Macharia‐Mutie 2012; Osei 2008 (C); Sharieff 2006 (C)), or other potential bias was unlikely (Lundeen 2010 (C); Ogunlade 2011; Troesch 2011b; Varma 2007 (C); Vinodkumar 2006 (C)).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We included data from 13 trials, involving 5810 participants, in this review; for trials that included more than two treatment arms, we may not have included all arms in our analyses. We have organised the summary of results by comparisons and by primary and secondary outcomes. Most of the included trials focused on haematological indices and few reported on any of the other outcomes prespecified in the review protocol (De‐Regil 2012). Many of the findings showed heterogeneity that could not be explained by standard sensitivity analyses or subgroup analysis, including quality assessment, and so we used a random‐effects model to analyse the results.

See the Data and analyses section for detailed results on primary and secondary outcomes.

For those outcomes that included data from cluster‐randomised trials, the number included is the effective sample size; that is, sample sizes and event rates have been adjusted for cluster‐trials to take account of the design effect.