Abstract

Background

Individuals with schizophrenia smoke more heavily than the general population and this contributes to their higher morbidity and mortality from smoking‐related illnesses. It remains unclear what interventions can help them to quit or to reduce smoking.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of different treatments for nicotine dependence in schizophrenia.

Search methods

We searched electronic databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO from inception to October 2012, and the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register in November 2012.

Selection criteria

We included randomised trials for smoking cessation or reduction, comparing any pharmacological or non‐pharmacological intervention with placebo or with another therapeutic control in adult smokers with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently assessed the eligibility and quality of trials, as well as extracted data. Outcome measures included smoking abstinence, reduction in the amount smoked and any change in mental state. We extracted abstinence and reduction data at the end of treatment and at least six months after the intervention. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence or reduction and biochemically validated data where available. We noted any reported adverse events. Where appropriate, we pooled data using a random‐effects model.

Main results

We included 34 trials (16 trials of cessation; nine trials of reduction; one trial of relapse prevention; eight trials that reported smoking outcomes for interventions aimed at other purposes). Seven trials compared bupropion with placebo; meta‐analysis showed that cessation rates after bupropion were significantly higher than placebo at the end of treatment (seven trials, N = 340; risk ratio [RR] 3.03; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.69 to 5.42) and after six months (five trials, N = 214, RR 2.78; 95% CI 1.02 to 7.58). There were no significant differences in positive, negative and depressive symptoms between bupropion and placebo groups. There were no reports of major adverse events such as seizures with bupropion.

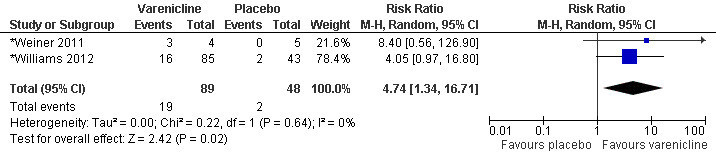

Smoking cessation rates after varenicline were significantly higher than placebo, at the end of treatment (2 trials, N = 137; RR 4.74, 95% CI 1.34 to 16.71). Only one trial reported follow‐up at six months and the CIs were too wide to provide evidence of a sustained effect (one trial, N = 128, RR 5.06, 95% CI 0.67 to 38.24). There were no significant differences in psychiatric symptoms between the varenicline and placebo groups. Nevertheless, there were reports of suicidal ideation and behaviours from two people on varenicline.

Two studies reported that contingent reinforcement (CR) with money may increase smoking abstinence rates and reduce the level of smoking in patients with schizophrenia. However, it is uncertain whether these benefits can be maintained in the longer term. There was no evidence of benefit for the few trials of other pharmacological therapies (including nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)) and psychosocial interventions in helping smokers with schizophrenia to quit or reduce smoking.

Authors' conclusions

Bupropion increases smoking abstinence rates in smokers with schizophrenia, without jeopardizing their mental state. Varenicline may also improve smoking cessation rates in schizophrenia, but its possible psychiatric adverse effects cannot be ruled out. CR may help this group of patients to quit and reduce smoking in the short term. We failed to find convincing evidence that other interventions have a beneficial effect on smoking in schizophrenia.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Schizophrenia; Smoking Prevention; Antidepressive Agents, Second‐Generation; Antidepressive Agents, Second‐Generation/therapeutic use; Benzazepines; Benzazepines/therapeutic use; Bupropion; Bupropion/therapeutic use; Nicotine; Nicotine/administration & dosage; Nicotinic Agonists; Nicotinic Agonists/therapeutic use; Quinoxalines; Quinoxalines/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Reinforcement, Psychology; Schizophrenic Psychology; Smoking Cessation; Smoking Cessation/methods; Tobacco Use Cessation Devices; Varenicline

Plain language summary

Are there any effective interventions to help individuals with schizophrenia to quit or to reduce smoking?

People with schizophrenia are very often heavy smokers. It is uncertain whether treatments that have been shown to help other groups of people to quit smoking are also effective for people with schizophrenia. In this review, we analysed studies which investigated a wide variety of interventions. Our results suggested that bupropion (an antidepressant medication previously shown to be effective for smoking cessation) helps patients with schizophrenia to quit smoking. The effect was clear at the end of the treatment and it may also be maintained after six months. Patients who used bupropion in the trials did not experience any major adverse effect and their mental state was stable during the treatment. Another medication, varenicline (a nicotine partial agonist which has been shown to be an effective intervention for smoking cessation in smokers without schizophrenia), also helps individuals with schizophrenia to quit smoking at the end of the treatment. However, this evidence is only based on two studies. We did not have sufficient direct evidence to know whether the benefit of varenicline is maintained for six months or more. In addition, there has been ongoing concern of potential psychiatric adverse events including suicidal ideas and behaviour among smokers who use varenicline. We found that two patients, among 144 who used varenicline, had either suicidal ideas or behaviour. Smokers with schizophrenia who receive money as a reward for quitting may have a higher rate of stopping smoking whilst they get payments. However, there is no evidence that they will remain abstinent after the reward stops. There was too little evidence to show whether other treatments like nicotine replacement therapy and psychosocial interventions are helpful.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Applicability in clinical practice ‐ projected numbers of people with schizophrenia per hundred patients treated with smoking cessation therapies (smoking abstinence at the end of the trial and at follow‐up after 6 months).

| Comparison | Smoking abstinence at the end of trial (per 100 patients) | Smoking abstinence at follow‐up after 6 months (per 100 patients) | ||||||||

| Number of trials | Intervention | Control | Difference * | Number needed# | Number of trials | Intervention | Control | Difference * | Number needed# | |

| Bupropion vs. placebo | 7 | 22 | 7 | ↓14 (↓5 to ↓31) |

7 (3 to 20) |

5 | 10 | 4 | ↓7 (0 to ↓24) |

15 (4 to 1350) |

| TNP vs. placebo | Data not combined because of heterogeneity of studies | No trial found | ||||||||

| Varenicline vs. placebo | 2 | 20 | 4 | ↓16 (↓1 to ↓65) |

6 (2 to 71) |

1 | 2 | 0 | ↓2 | # |

| CR + TNP vs. minimal | 1 | 50 | 10 | ↓40 | 3 | No follow‐up data available | ||||

* calculated as absolute risk reduction/increase per 100 people treated, using the rate in control (comparator) arms of trials, with the summary RR applied to calculate the expected absolute risk reduction/ increase for the investigative arms of trials (95% confidence intervals in bracket)

‘ns’ = difference not statistically significant (i.e. summary risk ratio confidence intervals cross 1.00).

# Number needed to be treated with the intervention to cause one person to experience difference in the direction noted. Number needed not given where difference between the intervention and the comparator arm was not significantly different (95% confidence intervals in bracket)

Summary of findings 2. Applicability in clinical practice ‐ smoking reduction at the end of the trial and at follow‐up after 6 months among people with schizophrenia treated with smoking cessation therapies.

|

Comparison (data were from abstinence study) |

Expired CO level at the end of trial (ppm) | Expired CO level at follow‐up after 6 months (ppm) | ||||||

| Number of trials | intervention | control | Difference | Number of trials | Intervention | Control | Difference | |

| Bupropion vs. placebo | 4 | 14.8 | 21.5 | ↓6.8 (↓2.8 to ↓10.8) |

3 | 18.8 | 22.7 | ns |

| TNP vs. placebo | Data not combined because of heterogeneity of studies | No trial found | ||||||

| Varenicline vs. placebo | 1 | #↓11.0 | #↓7.1 | ns | No follow‐up data available | |||

| CR + TNP vs. minimal | 1 | 17.7 | 27.5 | ↓9.8 | No follow‐up data available | |||

‘ns’ = difference not statistically significant

# ‐ these figures represent the mean reduction of expired CO level (in ppm) compared to the baseline level.

Background

Schizophrenia is a chronic and severe mental illness affecting approximately one per cent of the general population (American Psychiatric Association 1994). A meta‐analysis of 42 epidemiological studies across 20 different countries shows that people with schizophrenia have more than five times the odds of current smoking than the general population, and smoking cessation rates are much lower in smokers with schizophrenia compared with the general population (de Leon 2005a). In addition, smokers with schizophrenia smoke more heavily and extract more nicotine from each cigarette (Olincy 1997; Kelly 1999; de Leon 2005a; Williams 2005). People with schizophrenia have a shorter life expectancy than the general population, and chronic cigarette smoking has been suggested as a major contributing factor to higher morbidity and mortality from malignancy and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in this group of patients, especially in people aged 35 to 54 years. (Brown 2000; Lichtermann 2001; Kelly 2011). Tobacco use among individuals with schizophrenia is financially costly; a study has shown that it consumed 27% of the monthly income of those residing in a high tobacco tax state (Steinberg 2004).

Heavy smoking in patients with schizophrenia has been reported to be associated with more of the positive symptoms of the condition, increased substance misuse, more frequent psychiatric hospitalisation and a higher suicide risk (Goff 1992; Ziedonis 1994; Workgroup on Substance Use Disorders 2006). Tobacco smoking also increases the metabolism of some antipsychotic medications (Desai 2001), and some patients may use tobacco to alleviate the side effects of neuroleptic medications. Individuals with schizophrenia often have impairment in their cognitive function, including difficulty in filtering out unnecessary information (Kumari 2002), secondary to abnormalities in the sensorimotor gating. Cigarette smoking appears to improve sensory gating in patients with schizophrenia (Adler 1998). Hence, patients with schizophrenia may use cigarette smoking to improve their cognitive function. In addition to the cognitive deficits of frontal executive function and in attention among individuals with schizophrenia, depressive symptoms, drug misuse, disorganised thinking and poor task persistence may also explain their lower motivation and greater difficulty for smoking cessation (Culhane 2008; Moss 2009). Patients with schizophrenia may be ambivalent about giving up smoking, as there are few role models of ex‐smokers and less specific support available for quitting smoking. Recent research also showed that they perceived a lower risk to their health associated with smoking when compared to people without schizophrenia (Kelly 2012). Furthermore, smoking is sometimes condoned in mental health settings, and in the past cigarettes were used in token economies to reinforce positive patient behaviour (Gustafson 1992). Smoking has also been recently shown as a possible way for social facilitation and stimulation enhancement among individuals with schizophrenia (Kelly 2012)

Tobacco control specialists and healthcare providers previously have not offered tobacco dependence treatment to patients with schizophrenia, probably secondarily to stigma, lack of information, or perceived hopelessness regarding abstinence (Williams 2006). More recent initiatives have aimed to improve the physical health of those with schizophrenia, and guidelines for cessation interventions for smokers with schizophrenia have now been published (Zwar 2007; Fiore 2008; Dixon 2009; Buchanan 2009).

Smokers with schizophrenia have a more severe nicotine dependence compared to smokers without schizophrenia (de Leon 2005a). Hence, interventions may not be as effective as they have been shown to be in the general population. We also need to consider the safety of these interventions, particularly those involving drug therapy. Some of the pharmacological treatments for nicotine dependence act on neurotransmission. For example, previous smoking cessation guidelines do not recommend the use of bupropion in smokers with schizophrenia, because there may be a theoretical risk of psychotic relapse if bupropion, a dopamine agonist, is used among patients with schizophrenia (Strasser 2001). Some case reports have suggested that varenicline (another medication which has been proven to be effective for smoking cessation in the general population) may exacerbate psychiatric symptoms including psychosis and mood symptoms (Freedman 2007; Liu 2009). Moreover, drug treatment for smoking cessation and reduction may interact with and alter the effectiveness of the antipsychotic medications commonly used among patients with schizophrenia. In addition, nicotine withdrawal can cause symptoms like depression, anxiety and irritability. All these factors may contribute to changes in the mental state of these patients, and the extent of these changes remains unclear. The aim of this review is to summarize existing evidence for different interventions in smoking cessation and reduction for individuals with schizophrenia.

Objectives

This review addressed the following objectives:

To examine the efficacy of different interventions (alone or in combination with other interventions) on smoking cessation in individuals with schizophrenia.

To examine the efficacy of different interventions (alone or in combination with other interventions) on smoking reduction in individuals with schizophrenia.

To assess any harmful effect of different interventions for smoking cessation on the mental state of patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

We included adult smokers with a current diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the criteria of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (World Health Organization 2003) or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association 1994). Smokers with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder were also included, because certain core symptoms are the same as in schizophrenia. We did not exclude patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who had other substance misuse disorder or additional psychiatric disorders, as individuals with schizophrenia have high prevalence of substance misuse disorders (Dixon 1999). If a study was conducted in a group of participants with mixed psychiatric diagnoses, we included that trial only when separate data for people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were available. We included people who may or may not have expressed an interest in stopping or reducing smoking. We reported whether or not participants in a study wanted to stop or reduce smoking.

Types of interventions

We included both pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions (alone or in combination) specific to smoking cessation or reduction. We included interventions intended for another purpose (e.g. antipsychotics for treating schizophrenia) if smoking abstinence or reduction outcomes were reported. We reported the results of these trials separately and they did not contribute to any meta‐analysis, since they were not designed to test the efficacy of the intervention for smoking cessation or reduction. The control condition could be another intervention (pharmacological or non‐pharmacological), placebo, or usual care.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Smoking abstinence at longest follow‐up

The primary outcome was abstinence from smoking assessed at least six months from the start of the intervention, according to the 'Russell Standard' (i.e. a common standard for outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials; West 2005). The United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel also suggested a minimum of six months as an adequate period of abstinence to assess treatment differences in the longer term (Fiore 2008). Abstinence could be assessed by self report or with biochemical verification. For data synthesis, we chose the strictest definition of abstinence in each trial, preferring sustained abstinence over point prevalence if both were reported. In studies that used biochemical validation of abstinence, only people whose self reports could be validated were classified as abstinent.

Change in mental state

Change in mental state was measured by change in positive symptoms (e.g. hallucinations, delusions), negative symptoms (e.g. anhedonia, avolition), and depressive symptoms.

Secondary outcomes

Smoking abstinence at the end of the intervention

This was measured as for the primary abstinence outcome.

Reduction of smoking behaviour or dependence

This was assessed at the end of the intervention and during the follow‐up period after the end of the intervention, if data were available. Measures could include any of the following: percentage change in cigarettes per day (CPD) from baseline level; absolute number of cigarettes foregone; incidence of achieving at least a 50% reduction in CPD; reduction of expired carbon monoxide (CO) level; or reduction of scores on scale measures of nicotine dependence (e.g. Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)).

Other adverse events

We recorded and assessed any other reported adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register in November 2012, using the topic‐related free‐text term 'schiz*'. See the Specialised Register section of the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library for search strategies for CENTRAL (the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and Web of Science, and dates of searches. CENTRAL was searched in The Cochrane Library 2012 issue 6, using the strategy ((SR‐SCHIZ) and (smoking):ti,ab,kw) AND NOT (SR‐TOBACCO).

In addition, we searched the following electronic databases in October 2012:

MEDLINE, MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations via OVID (1948 onwards)

EMBASE via OVID (1980 onwards)

PsycINFO via OVID (1806 onwards)

CINAHL Plus with Full Text (1979 onwards)

ISI Web of Science with Conference Proceedings (1900 onwards)

BIOSIS Previews (1969 onwards)

We included all data available up to the last date of search and in any language. We included search terms for schizophrenia, smoking and randomised trials. For schizophrenia, we used the search terms used by the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group. For smoking cessation and reduction, we used search terms defined by the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, with some modification to focus on interventions for both smoking cessation and reduction. To identify randomised trials, we used the search strategies suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Full search strategies for databases are listed in the appendix of this review (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3).

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of retrieved studies for additional relevant information. We also searched the following online clinical trials registers to identify potential ongoing and unpublished trials: 1. World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch); 2. ClinicalTrials.gov register (www.clinicaltrials.gov); 3. The Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au); 4. International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (www.controlled‐trials.com/isrctn/); 5. UK Clinical Trials Gateway (www.controlled‐trials.com/ukctg/). Where we suspected duplicate reporting of the same trial, we attempted to contact authors for clarification. If duplication was confirmed, we used the full publication together with any other related publications for additional information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All of the authors (DTT, MP and ACW) independently screened the titles and abstracts identified by the search, and decided on the possible reports to be included. We obtained and examined full text reports of all potentially relevant trials, to decide whether the studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Any disagreement between the authors was resolved through discussion. All studies excluded at this stage are reported in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (DTT and MP) independently extracted data from all included trials, with a specifically designed data extraction form. Information extracted included the following:

Methodology ‐ comprising the inclusion and exclusion criteria, method of randomisation and other design features and setting of the trial.

Demographics of participants ‐ including severity of tobacco dependency, concurrent medication used and severity of schizophrenic illness.

Details of the interventions ‐ including any target quit date set.

Outcome measures ‐ including the definition of abstinence and length of follow‐up and measurements used, including any biochemical verification.

We attempted to contact the authors of the reports if there were any uncertainties or possible duplicate reporting of the same patient group, or for clarification of the study design and results. We sought separate data for participants with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in trials that recruited people with a wider range of psychiatric diagnoses. Any disagreement between the authors was resolved through discussions or consultation with another author (ACW).

We categorised trials according to the primary aim of the study (i.e. smoking cessation, smoking reduction, or intervention with other aims). To group trials by category in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, we used the prefixes *, + , and ^ as part of the study identifiers. For each category, we grouped the trials according to the specifics of the intervention.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

During data extraction, two authors (DTT and MP) also independently assessed each trial for risk of bias according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We recorded sequence generation during randomisation, concealment of allocation, blinding, completeness of outcome data (including use of intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis) and selective outcome reporting for each trial. We also identified other potential sources of bias. We categorised each trial as being at low, uncertain or high risk of bias for each domain, based on the standards described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated summary estimates for the extracted data. Results for dichotomous outcomes were expressed as risk ratios (RR). The RR was calculated as: ((number of participants with the outcome in intervention group / number of participants randomised to intervention group) / (number of participants with the outcome in the control group / number of participants randomised to the control group)). An RR greater than one favoured the intervention group. Results for continuous outcomes were expressed as mean difference (MD) where measured with the same scale, or standardised mean difference (SMD) where measured with different scales. A summary MD or SMD below zero favoured the intervention group in all continuous outcome measures.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact trial authors for any missing data. For data synthesis, where no additional information was forthcoming, we assumed any missing data as failure to achieve the outcome. We also addressed the potential impact of the missing data in the risk of bias table for each study. We did not include trials for meta‐analysis of continuous outcomes if there was no standard deviation (SD) or other estimate of variability available.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined statistical heterogeneity among trials with the Cochran Q test and by calculating the I² statistic. The I² statistic describes the percentage of the variability in the summary estimate due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2003). Values over 50% suggested moderate heterogeneity and values over 75% suggest substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where appropriate, we assessed potential publication bias with funnel plots of the log risk ratio, mean difference or standardised mean difference.

Data synthesis

Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis of the trial data. For abstinence and reduction, we conducted analyses with data from six‐month follow‐up (primary outcome) and from the end of the intervention (secondary outcome). For change in mental state we conducted separate analyses for positive, negative, and depressive symptoms, using data available at the end of the intervention.

For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the summary estimates using the Mantel‐Haenszel method and reported the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the risk ratios. We calculated the summary estimates for continuous outcomes using the inverse variance approach, also with 95% CIs. Change‐from‐baseline measurements and final measurements were combined for continuous outcomes if the mean difference was used to express the summary results, following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

We pooled data using the random‐effects model, although the fixed‐effect model was also used to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses when appropriate, to assess whether the estimate of treatment effect was influenced by various factors, such as location of the trials or publication types etc.

Results

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

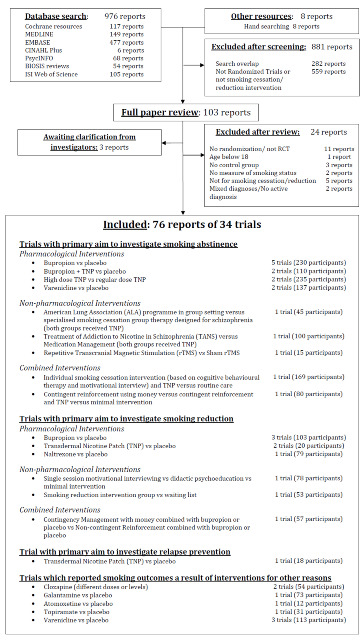

We identified 976 reports from the electronic search of the databases (149 reports from MEDLINE, 477 from EMBASE, 68 from PsycINFO, 6 from CINAHL Plus, 54 from BIOSIS reviews, 105 from ISI Web of Science with Conference Proceedings, and 117 reports from CENTRAL and the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register) (Figure 1). We identified eight further trial reports from handsearching and nine ongoing studies from the online clinical trials registers and from handsearching (See Characteristics of ongoing studies). After screening, we reviewed the full text of 103 reports which were considered potentially eligible. We excluded 24 reports of 22 trials after reviewing the full text (See Characteristics of excluded studies). We also contacted the investigators of two trials to clarify the method of treatment allocation, as we had concerns that these two trials were not randomised because of the uneven number of participants among the treatment groups. We have not received any response; see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

1.

Summary of the process of identifying randomised trials for inclusion

The final review includes 34 trials; see the Characteristics of included studies table. The primary aim of 16 trials was to investigate an intervention for smoking cessation (studies prefixed with an asterisk: *George 2000; *Evins 2001; *George 2002; *Evins 2005; *Baker 2006; *Evins 2007; *Gallagher 2007; *Williams 2007; *George 2008; *Li 2009; *Williams 2010; *Weiner 2011; *Chen 2012; *Weiner 2012; *Williams 2012; *Wing 2012). Nine studies focused on smoking reduction (studies prefixed with a cross; +Hartman 1991; +Dalack 1999; +Steinberg 2003; +Fatemi 2005; +Akbarpour 2010; +Bloch 2010; +Szombathyne 2010; +Tidey 2011; +Gelkopf 2012). One trial investigated the use of nicotine patch for relapse prevention after smoking cessation (^Horst 2005). The remaining eight studies reported outcomes related to smoking abstinence or reduction, but their main aims were to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for other purposes. These studies are reported separately, and do not contribute data to any meta‐analysis (McEvoy 1995; de Leon 2005b; Kelly 2008; Weinberger 2008; Sacco 2009; Hong 2011; Meszaros 2012; Shim 2012)

Included studies

1. Trials of interventions for smoking cessation, reduction or relapse prevention

Study and participant characteristics

There were 26 trials in this category; most were conducted in the United States and reported in English, apart from *Baker 2006, conducted in Australia; *Wing 2012, conducted in Canada; +Akbarpour 2010, conducted in Iran; +Bloch 2010 and +Gelkopf 2012, conducted in Israel; *Chen 2012 conducted in Taiwan; and *Li 2009, conducted in China and reported in Chinese. Most of the reports were published in journals, except for four trials which were only reported as letters to editors or conference proceedings (+Fatemi 2005; *Williams 2007; +Szombathyne 2010; *Wing 2012). There were three cross‐over studies (+Hartman 1991; +Dalack 1999; +Fatemi 2005) with washout periods from five days to two weeks. The relapse prevention study (^Horst 2005) involved an open‐label phase followed by a randomised controlled trial; in this review we only considered data from the randomised trial phase.

Most trials recruited participants from the community. Four trials (*Chen 2012; *Li 2009; +Akbarpour 2010; +Gelkopf 2012) recruited only smokers in inpatient units, and +Hartman 1991 recruited from hospitals and the community. Two studies did not report details of recruitment (*George 2000; +Steinberg 2003).

Three trials (+Hartman 1991; *Baker 2006; *Gallagher 2007) recruited smokers with mixed psychiatric diagnoses, but data for participants with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were available for separate analysis. A significant number of studies explicitly excluded participants with any active substance misuse other than nicotine (+Dalack 1999; *Evins 2001; *George 2002; *Evins 2005; *Evins 2007; *George 2008; +Akbarpour 2010; +Bloch 2010; +Tidey 2011; *Weiner 2011; +Gelkopf 2012; *Weiner 2012; *Williams 2012; *Wing 2012). +Szombathyne 2010 investigated schizophrenia patients with both nicotine and alcohol dependence.

Sixteen trials explicitly stated that participants had expressed interest in quitting or reducing smoking (*George 2000; *Evins 2001; *George 2002; *Evins 2005; ^Horst 2005; *Baker 2006; *Evins 2007; *Williams 2007; *George 2008; +Bloch 2010; *Williams 2010; +Tidey 2011; +Gelkopf 2012; *Weiner 2012; *Williams 2012; *Wing 2012). +Steinberg 2003 measured changes in quitting motivation after motivational interviewing, where the participants had different levels of interest in quitting smoking at the baseline. Participants in *Chen 2012 also varied in their motivation and readiness to quit smoking. Target quit dates were set in 13 studies (*George 2000; *Evins 2001; *George 2002; *Evins 2005; ^Horst 2005; *Baker 2006; *Evins 2007; *George 2008; *Williams 2010; *Weiner 2011; *Weiner 2012; *Williams 2012; *Wing 2012).

Interventions

We evaluated a range of interventions. Of the studies comparing pharmacotherapy with placebo, the commonest interventions were bupropion (*Evins 2001; *George 2002; *Evins 2005; +Fatemi 2005; *Li 2009; +Akbarpour 2010; +Bloch 2010; *Weiner 2012), transdermal nicotine patch (TNP) (+Hartman 1991; +Dalack 1999; ^Horst 2005) and varenicline (*Weiner 2011; *Williams 2012). +Szombathyne 2010 investigated the effect of naltrexone in smoking and alcohol reduction. Two studies compared the combination of bupropion and TNP, with TNP and placebo (*Evins 2007; *George 2008). Two trials compared the efficacy of different dosages of TNP (*Williams 2007; *Chen 2012) for smoking cessation. Some of the drug therapy studies provided psychosocial interventions to all participants. These psychosocial interventions included group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (*Evins 2001; *Evins 2005; *Evins 2007; +Bloch 2010), group therapy for motivational enhancement, psychoeducation and relapse prevention (*George 2002); group behavioural therapy (*George 2008; *Wing 2012); smoking cessation educational classes along with discussions with health educators (^Horst 2005); group psychoeducation (*Chen 2012); group therapy using the American Cancer Society Fresh Start Program (*Weiner 2012) and individual smoking cessation counselling (*Weiner 2011; *Williams 2012). The duration of drug treatment varied from seven hours (+Hartman 1991) to six months (^Horst 2005).

Five trials predominantly examined the effect of non‐pharmacological interventions. +Steinberg 2003 examined the effect of a single session of motivational interview and compared this with didactic psychoeducation and minimal control intervention. *George 2000 compared the American Lung Association programme in a group setting with a specialised group therapy designed for schizophrenia which had more focus on motivational enhancement, psychoeducation, social skills training and relapse prevention strategy; participants in both groups also received TNP. *Williams 2010 investigated the effect of the Treatment of Addiction to Nicotine in Schizophrenia (TANS) programme (individual 45‐minute weekly sessions for 26 weeks) and compared this with Medication Management (MM) (nine individual 20‐minute sessions over 26 weeks). Participants also received TNP in both groups in this trial. +Gelkopf 2012 in Israel examined the effect of a weekly group session for five weeks, focusing on smoking reduction in a hospital setting. Apart from psychosocial interventions, *Wing 2012 used repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to investigate whether this was effective for smoking cessation among individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Three other trials investigated the combined effect of pharmacological and psychosocial interventions. In *Baker 2006, a combination of individually administered motivational interviewing with CBT and TNP was compared with routine care. In a three‐arm study, *Gallagher 2007 compared contingent reinforcement (CR) using money, with and without additional TNP, and a self quit control without TNP. In +Tidey 2011, participants were randomised to four different combinations of interventions: bupropion and contingency management (CM); placebo and CM; bupropion and non‐contingent reinforcement (NR); placebo and NR.

Outcomes

Abstinence was defined and measured in 16 trials (*George 2000; *Evins 2001; *George 2002; *Evins 2005; *Baker 2006; *Evins 2007; *Gallagher 2007; *Williams 2007; *George 2008; *Li 2009; *Williams 2010; *Weiner 2011; *Chen 2012; *Weiner 2012; *Williams 2012; *Wing 2012). Three of these studies did not explicitly report whether participants expressed any interest in quitting smoking (*Li 2009; *Weiner 2011; *Chen 2012). Five trials did not report any continuation of follow‐up beyond the end of the intervention; *Williams 2007; *Li 2009; and *Chen 2012 reported abstinence at eight weeks; *Weiner 2011 and *Weiner 2012 after 12 weeks. *Wing 2012 reported abstinence at week 10, i.e. six weeks after the end of the intervention which last for four weeks. The other 10 studies provided results for longer follow‐up, of at least 24 weeks after the start of treatment. All trials except *Li 2009 validated abstinence biochemically. One study reported the rate of relapse to smoking after abstinence (^Horst 2005).

Nine trials only reported smoking reduction as the main outcome measure (+Hartman 1991; +Dalack 1999; +Steinberg 2003; +Fatemi 2005; +Akbarpour 2010; +Bloch 2010; +Szombathyne 2010; +Tidey 2011; +Gelkopf 2012). Most of the studies which measured smoking abstinence also reported some measures of smoking reduction. Self report of reduction in cigarettes per day (CPD) was commonly used as a measure of reduction (+Hartman 1991; +Dalack 1999; *Evins 2001; *George 2002; +Steinberg 2003; *Evins 2005; +Fatemi 2005; *Baker 2006; *Evins 2007; *Gallagher 2007; *Li 2009;+Akbarpour 2010; +Bloch 2010; +Szombathyne 2010; *Williams 2010; +Tidey 2011; +Gelkopf 2012; *Williams 2012). These outcomes were reported after a range of follow‐up periods which varied from two days (+Hartman 1991) to four years (*Baker 2006). Expired carbon monoxide (CO) level reduction was also frequently reported as a measure of smoking reduction (+Dalack 1999; *George 2000; *George 2002; +Steinberg 2003; *Evins 2005; ^Horst 2005; *Gallagher 2007; +Tidey 2011; *Weiner 2011; *Williams 2010; *Weiner 2012; *Wing 2012). Other measures of smoking reduction included plasma cotinine level (*Evins 2001), scale measure of nicotine dependence (e.g. Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)) (+Steinberg 2003; +Fatemi 2005; *Gallagher 2007; *Li 2009; +Bloch 2010; *Weiner 2012), urine cotinine level (+Fatemi 2005; *Weiner 2012) and salivary cotinine level (*Gallagher 2007).

Most studies reported measures of mental state of the participants (+Dalack 1999;*George 2000; *Evins 2001; *George 2002; *Evins 2005; +Fatemi 2005; *Baker 2006; *Evins 2007; *George 2008; *Li 2009; +Akbarpour 2010; +Bloch 2010; *Williams 2010; +Tidey 2011; *Weiner 2011; *Chen 2012; +Gelkopf 2012; *Weiner 2012; *Williams 2012; *Wing 2012; *Chen 2012).

2. Trials of interventions with primary aim other than smoking cessation, reduction or relapse prevention

Eight trials reported outcomes of smoking behaviour change, but were not originally designed to investigate smoking cessation or reduction (McEvoy 1995; de Leon 2005b; Kelly 2008; Weinberger 2008; Sacco 2009; Hong 2011; Meszaros 2012; Shim 2012). Weinberger 2008 only included participants with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. Meszaros 2012 included people with both nicotine and alcohol dependence. Five studies included non‐smokers as participants, and performed separate analyses for those who smoked, in relation to their smoking behaviours (de Leon 2005b; Kelly 2008; Weinberger 2008; Hong 2011; Shim 2012). Although varenicline has been shown to be an effective treatment for smoking cessation in the general population, three studies investigated its possible uses in schizophrenia other than primarily for smoking cessation. Hong 2011 and Shim 2012 examined the effect of varenicline on cognitive function in schizophrenia. Meszaros 2012 investigated the use of varenicline as a treatment for alcohol dependence among individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Two trials investigated the effect of clozapine in patients with treatment‐resistant schizophrenia (McEvoy 1995; de Leon 2005b). Other interventions included galantamine (Kelly 2008), atomoxetine (Sacco 2009) and topiramate (Weinberger 2008). None of these trials included smoking abstinence as an outcome, but used various methods to measure smoking reduction.

Risk of bias in included studies

1. Trials of interventions for smoking cessation, reduction or relapse prevention

We judged 11 trials to have used an adequate method for generating the randomisation sequence (+Dalack 1999; *Evins 2001; +Steinberg 2003; *Evins 2005; ^Horst 2005; *Baker 2006; *Evins 2007; *Gallagher 2007; *Williams 2010; +Tidey 2011; +Gelkopf 2012). Most of the other studies were classified as unclear because there was no description of the randomisation process and we could not clarify details with the investigators. We obtained additional information on *Li 2009 and +Bloch 2010 (see details in Characteristics of included studies), and judged these two trials as having a high risk of bias.

We judged five studies to have used an adequate method of allocation concealment (+Dalack 1999; *Evins 2001; *Evins 2005; *Evins 2007; *Williams 2010). Other studies did not clearly report the method of allocation concealment and we could not clarify this with the investigators, so the risk of bias was judged to be unclear. Correspondence with *Li 2009, showed that there was no concealment of allocation sequence and hence we judged the study as having a high risk of bias. We had some clarification from *Gallagher 2007 regarding allocation concealment. In their study, allocation was not done centrally and there was a possibility that research staff might know which group the subsequent participant would be assigned to. Hence, we judged that study as having a high risk of bias in allocation concealment. +Bloch 2010 reported that people were randomly allocated based upon their order of arrival and we judged that it was unlikely that allocation concealment was done properly and hence that it had a high risk of bias. We also obtained information from +Gelkopf 2012 regarding their randomisation (see details in Characteristics of included studies), and we believe that it is likely that allocation concealment would be compromised at the very end of the drawing, as the next person's allocation group would become obvious. As a result, we also judged it as high risk of bias.

Adequate blinding to treatment allocation in assessment of outcomes was observed in 10 trials (+Hartman 1991; +Dalack 1999; *Evins 2001; *George 2002; *Evins 2005; +Fatemi 2005; *Evins 2007; +Tidey 2011; *Williams 2012; *Wing 2012). Some studies reported double‐blinding but their reports did not explicitly state who was blinded, and we were not able to clarify this with the investigators (*Williams 2007; *George 2008; *Li 2009; +Akbarpour 2010; +Bloch 2010; +Szombathyne 2010; *Weiner 2011; *Chen 2012: *Weiner 2012). We judged that double‐blinding implied that it was likely that participants and investigators were blinded, but we declared all these studies as having an unclear risk of bias even though it was likely that the possible bias introduced into these studies was minimal. Some studies were assessed to have inadequate blinding. Significant bias could be introduced in these studies without adequate blinding, as self report measures (e.g. self reported reduction of cigarettes used) and subjective assessment (e.g. assessment of psychiatric symptoms) were used for outcome assessments. Three studies did not report any blinding (*George 2000; *Gallagher 2007; +Gelkopf 2012). Only the outcome assessor was blinded in another three studies (+Steinberg 2003; *Baker 2006; *Williams 2010). ^Horst 2005 blinded participants but not the outcome assessor.

There were wide‐ranging variations in how missing outcome data were handled. We judged nine studies as having a low risk of bias secondary to incomplete outcome data (+Dalack 1999; *George 2002; *Baker 2006; *Evins 2007; +Akbarpour 2010; *Weiner 2011; *Chen 2012; +Gelkopf 2012; *Weiner 2012). These studies included all participants who were randomised and used true intention‐to‐treat analysis. Those with missing data were classified either as non‐abstinent or as failing to achieve smoking reduction in these studies (*Baker 2006; *Evins 2007; *Weiner 2012). Some trials used the 'last observation carried forward' approach to handling missing data (+Steinberg 2003; *Gallagher 2007). We had a concern whether this approach was appropriate, as those who were lost to follow‐up may be more likely to relapse, so that the 'last observation carried forward' assumption would probably have overestimated the intervention effect by assuming these participants to have maintained abstinence. Hence, we categorised these trials as having a high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data. In other trials, participants who were randomised were excluded from the analysis for various other reasons. These reasons included dropping out before the start of the intervention (*Evins 2001; *Evins 2005; *George 2008; *Williams 2010; +Tidey 2011; *Williams 2012); the need for dose change for symptom stabilisation or side effects of medications (*George 2000); stopping the intervention during the trial (^Horst 2005; *Li 2009; +Bloch 2010); and lost to follow‐up (+Hartman 1991). We judged all these studies to have a high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data. Three trials did not clearly state how they handled missing outcome data, and were classified as having an unclear risk of bias (+Fatemi 2005; *Williams 2007; +Szombathyne 2010). *Wing 2012 mentioned that an intention‐to‐treat analysis was employed but we could not confirm this. As a result, we classified this trial as at unclear risk of bias.

Three studies did not report all outcome results as predicted in their methods section or in their protocol, and these trials were classified as having a high risk of selective reporting (+Dalack 1999; +Fatemi 2005; *Gallagher 2007).

There were large differences in contact time between the intervention and control groups in a number of trials which examined the effect of non‐pharmacological interventions. *Baker 2006 compared an intervention involving eight hours of individual contact over eight weeks with routine care, which had no extra contact time. *Gallagher 2007 compared three groups; Contingent Reinforcement (CR) with transdermal nicotine patch (TNP), CR only, and self quit without any active intervention. The self quit group had only three visits, but the other two groups had 12 visits for each group. +Steinberg 2003 compared three groups: motivational interview for 40 minutes; didactic psychoeducation for 40 minutes; and minimal intervention for five minutes. In *Williams 2010, the Treatment of Addiction to Nicotine in Schizophrenia (TANS) group received 24 sessions of 45‐minute individual psychological intervention, compared to the Medication Management (MM) group only received nine 20‐minute sessions. +Gelkopf 2012 compared the smoking reduction intervention group which had a weekly one‐hour session for five weeks, with the waiting list which only received one lecture on the dangers of smoking.

There were some other possible biases. Despite randomisation, four studies had statistically significant differences in some characteristics between the intervention and the control groups (*George 2000; *Evins 2005; *Williams 2010; +Tidey 2011). In ^Horst 2005, where the RCT phase followed an earlier open‐label phase, the report did not clearly state whether the two comparison groups were similar in terms of their baseline characteristics. Six trials lacked biochemical validation of smoking status (+Hartman 1991; *Li 2009; +Akbarpour 2010; +Bloch 2010; +Szombathyne 2010; +Gelkopf 2012). Two of the three cross‐over studies had relatively short washout periods, of five days (+Dalack 1999) and one week (+Hartman 1991). In the other cross‐over study (+Fatemi 2005), individual data were not available in the report and it was unclear whether paired analyses were used in the analysis. In those studies which were reported either as 'letters to editors' or as conference proceedings (*Williams 2007; *Weiner 2011; *Wing 2012), there was insufficient information to assess whether any other important bias existed, and we judged them as unclear. *Williams 2012 was sponsored by the drug company that manufactured varenicline, and we judged it as unclear whether any other important bias existed.

2. Trials of interventions with primary aim other than smoking cessation, reduction or relapse prevention

Within this group we only judged two trials to have a low risk of bias in sequence generation (Kelly 2008; Meszaros 2012), and one trial as having a low risk of bias in allocation concealment. Other trials did not explicitly describe the way in which the randomisation sequence was generated, and we could not clarify this with the investigators, so the risks of bias in sequence generation and allocation concealment were rated as unclear. Four trials reported double‐blinding but their reports did not explicitly state who were blinded, and we were not able to clarify this with the investigators (McEvoy 1995; Sacco 2009; Meszaros 2012; Shim 2012). The study by de Leon 2005b excluded four participants from the analysis without stating the reason. Another study used the 'last observation carried forward' method for missing data (Weinberger 2008). In Hong 2011 and Meszaros 2012, there were no intention‐to‐treat analyses and they did not include all people who were randomised in their denominators. Hence, we judged these four trials as having a high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data.

In Kelly 2008 and Weinberger 2008, the results in the reports were subgroup analyses of larger related trials, and some people who smoked were not included in the analysis. The reason for not including these people was unclear, and selection bias might have been introduced. The study by de Leon 2005b reported unequal numbers among the intervention groups and there was no information as to whether these groups were comparable in characteristics and in their baseline cotinine levels. There were also baseline differences between comparison groups in the study by McEvoy 1995. We therefore judged all these trials as having a high risk for other biases.

Effects of interventions

We have grouped the included studies under the following categories: 1. Trials in which the primary aim was smoking cessation; 2. Trials in which the primary aim was smoking reduction; 3. Trials in which the primary aim was relapse prevention; 4. Trials of other interventions which reported smoking outcomes. Within each category, if appropriate, trials were grouped according the principal intervention comparison in each study. For instance, if the main comparison of a study was a drug therapy (even if there was any additional psychosocial intervention for both treatment and placebo groups), the study was grouped under pharmacological interventions. Similarly, if the main comparison of a study was a psychosocial intervention (even if there was any additional drug treatment to all the comparison groups), this was grouped under non‐pharmacological interventions.

1. Trials with a primary aim of smoking abstinence

1.1 Pharmacological intervention ‐ bupropion

Intervention rationale: Bupropion is an atypical antidepressant with both dopaminergic and adrenergic actions. There is robust evidence that bupropion is a safe and effective treatment for nicotine dependence in the general population (Hughes 2007). There is however a theoretical concern about the safety of using bupropion in patients with schizophrenia, as bupropion may precipitate or exacerbate psychosis because of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties. Bupropion and its metabolite inhibit the cytochrome P450 CYP2D6 isoenzyme, and co‐administration of bupropion with drugs that are metabolised by this isoenzyme (including antipsychotic medications such as risperidone, haloperidol) may cause significant drug interactions (GlaxoSmithKline 2008). This, as well as bupropion’s dopaminergic action, may adversely affect the mental state of individuals with schizophrenia. In addition, seizure is a recognised adverse effect of bupropion in the general population, with a rate of between 0.1% and 0.4% (GlaxoSmithKline 2008).

Abstinence outcomes

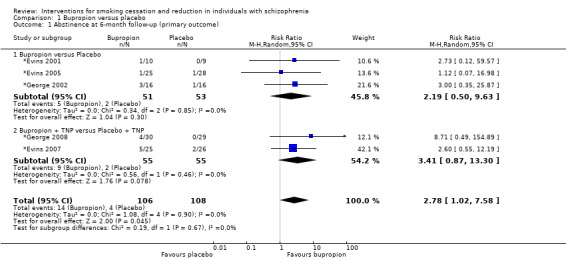

Seven trials with a total of 340 participants investigated bupropion as an aid for smoking cessation. Five trials (*Evins 2001; *George 2002; *Evins 2005; *Evins 2007; *George 2008) had six‐months follow‐up from the start of bupropion treatment. *Weiner 2012 and these five trials recruited participants who were interested in quitting smoking, and set a target quit date. The study in China by *Li 2009 did not report whether participants had any interest in quitting. At six‐months follow‐up, participants who took bupropion were nearly three times more likely to be abstinent compared to those allocated to placebo, with a lower confidence interval that just excluded one (five trials, N = 214, risk ratio (RR) 2.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02 to 7.58, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.1; Figure 2). There was no strong evidence for a difference in relative effect between the three trials using bupropion as the sole pharmacotherapy and the two trials using bupropion as an adjunct to transdermal nicotine patch (TNP) (*Evins 2007; *George 2008); confidence intervals were wide in both subgroups. The number of successful quitters was small in all studies. Two trials (*Evins 2001; *Evins 2007) reported data on smoking cessation from a follow‐up of longer than six months: In the two‐year follow‐up report for *Evins 2001, 4 of 18 participants were abstinent, including the only person who was abstinent at the end of the trial. The investigators reported that three of the four abstinent after two years received bupropion slow release (SR) during the trial or during the follow‐up period, and the fourth quit during an extended medical hospitalisation. By the 12‐month follow‐up for *Evins 2007, two more intervention group participants had relapsed. Had the outcome at this point been used in the meta‐analysis, the estimated effect would have been smaller and the confidence intervals for the pooled estimate would have included one (i.e. statistically non‐significant).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bupropion versus placebo, Outcome 1 Abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up (primary outcome).

2.

Bupropion versus placebo: Abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up (primary outcome)

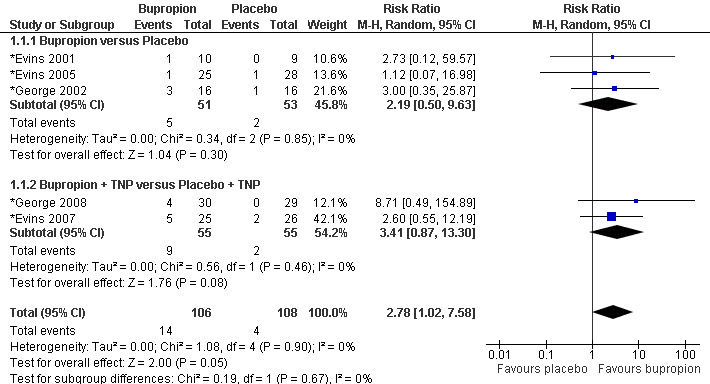

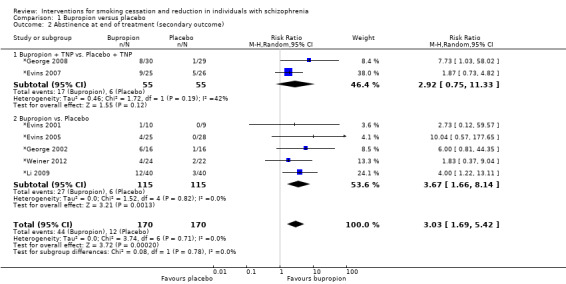

The effect size was similar for the secondary outcome of abstinence at the end of treatment, but the confidence intervals were narrower, reflecting the two additional trials and the larger number of successful short‐term quitters (seven trials, N = 340; RR 3.03, 95% CI 1.69 to 5.42, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.2). Sensitivity analyses detected no important difference in effect from omitting any of the following: one trial was conducted outside the USA and the participants' interests in quitting were uncertain (*Li 2009); or one trial using the lower dose of 150 mg bupropion daily (*Evins 2001), compared with 300 mg daily in other trials.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bupropion versus placebo, Outcome 2 Abstinence at end of treatment (secondary outcome).

Mental state outcomes

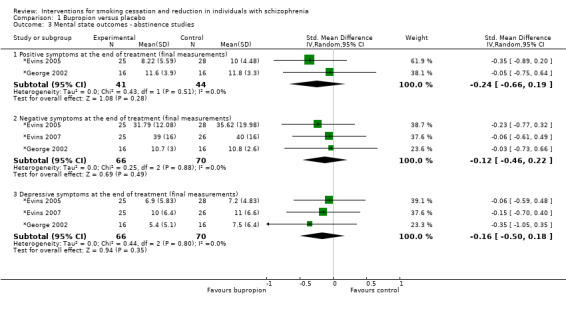

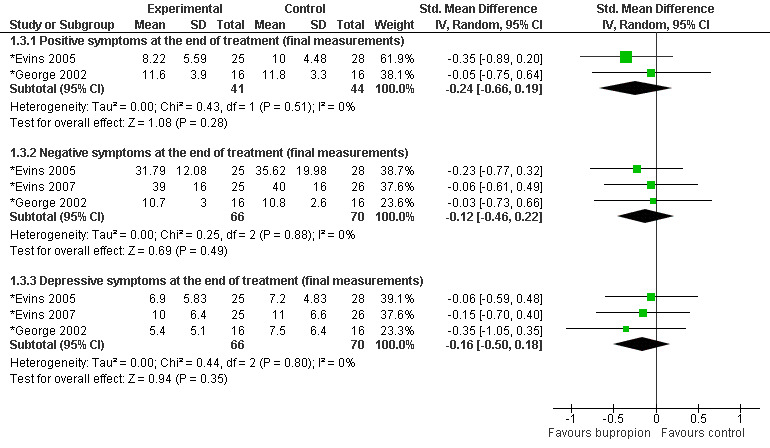

All trials reported the effect of bupropion on the mental state of the participants. Compared with placebo, there was no evidence that bupropion caused any significant deterioration of positive, negative or depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia during smoking cessation. Two studies provided sufficient final measurement data for estimation of change of positive symptoms, and one additional study also provided sufficient data to estimate the effect of bupropion on negative and depressive symptoms. There was no evidence that bupropion, compared to control, caused a significant difference in positive symptoms (two trials, N = 85; standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.24, 95% CI ‐0.66 to 0.19; I² = 0%), in negative symptoms (three trials, N = 136; SMD ‐0.12, 95% CI ‐0.46 to 0.22; I² = 0%) or depressive symptoms (three trials, N = 136; SMD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.50 to 0.18; I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.3; Figure 3). Other trials also consistently reported that there was no significant difference in these symptoms between the bupropion group and the placebo group after bupropion treatment, but without reporting full data (*George 2008; *Li 2009; *Weiner 2012). In *Evins 2001, bupropion treatment was associated with improvement in negative symptoms and greater stability of psychotic and depressive symptoms, compared to the placebo, during the quit attempt. Three studies also reported the effect of abstinence on the mental state of the participants, and found no effects of smoking abstinence on positive, negative or depressive symptoms (*Evins 2005; *Evins 2007; *George 2008).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bupropion versus placebo, Outcome 3 Mental state outcomes ‐ abstinence studies.

3.

Bupropion versus placebo: Mental state outcomes

Adverse effects

Regarding other adverse effects of bupropion, one participant who took bupropion had a seizure at the end of the trial (*Weiner 2012). However, this patient had a history of polydipsia and was found to have hyponatraemia when he had the seizure. It was likely that the seizure related to polydipsia rather than to bupropion. No seizures were reported in any other trial.

The prevalence of dry mouth was significantly higher in the bupropion group compared to the control group in one study (P < 0.05; *George 2002). The same research group, in a second study (*George 2008), reported significant differences in concentration, jitteriness, light‐headedness, muscle stiffness and frequent nocturnal awakening in the bupropion group. Three of the 59 participants (two in the placebo group and one in the bupropion group) had a psychotic breakdown during that trial, but the authors concluded this was unrelated to bupropion. *Li 2009 reported significantly higher prevalence of insomnia, dry mouth and sweatiness in the bupropion group compared to the control group. Two people from this trial had a recurrence of psychotic symptoms, but the author did not report to which group they had been allocated. One participant in *Evins 2005, randomised to bupropion, had an allergic reaction to the medication. Two participants in *Evins 2007, using bupropion and TNP, dropped out from the trial because of insomnia and dizziness. In *Weiner 2012, they did not find any significant group differences in any of the major adverse events measured by Side Effect Checklists (SEC). The SEC included common bupropion side effects such as restlessness, insomnia, dry mouth and sedation. Five participants from the bupropion group dropped out because of side effects (two people complained of restlessness and increased anxiety in the first week, one complained of worsening of psychosis, one developed a rash at week two, and one developed a seizure, as reported above). The remaining trial reported 'no serious adverse events' (*Evins 2001).

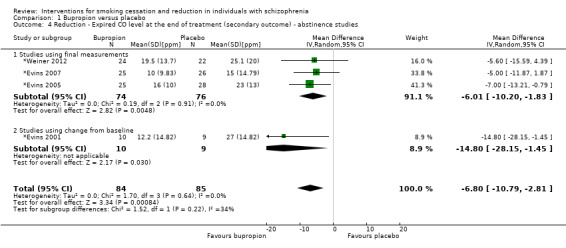

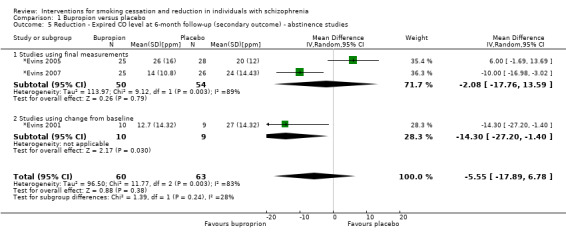

Smoking reduction

Most trials also reported some outcome measures for smoking reduction. However, the data for these outcome measures were probably from the entire sample (i.e. including participants who successfully abstained from smoking and those who continued to smoke). Three trials reported data for smoking reduction measured by expired carbon monoxide (CO) level. At the end of treatment, there was a significant reduction of expired CO in the bupropion group compared to the control group (four trials, N = 169; MD ‐6.80 parts per million (ppm), 95% CI ‐10.79 to ‐2.81 ppm, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.4). *Evins 2001 reported incomplete data for expired CO level and did not contribute to the meta‐analysis, but both favoured bupropion at the end of the treatment. At six months after the start of treatment there was no significant difference in expired CO level (three trials, N = 123; MD ‐5.55 ppm, 95% CI ‐17.89 to 6.78 ppm; Analysis 1.5) but there was substantial heterogeneity among trials (I² = 83%), largely due to one trial in which the average CO level was higher in the bupropion group than the placebo group (*Evins 2005).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bupropion versus placebo, Outcome 4 Reduction ‐ Expired CO level at the end of treatment (secondary outcome) ‐ abstinence studies.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bupropion versus placebo, Outcome 5 Reduction ‐ Expired CO level at 6‐month follow‐up (secondary outcome) ‐ abstinence studies.

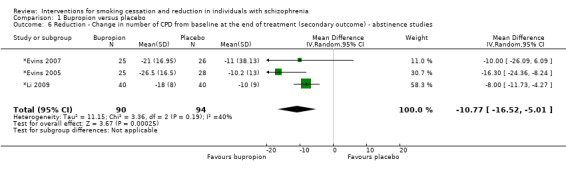

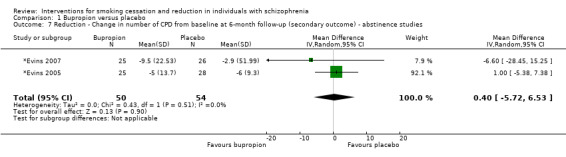

Three trials provided data from the entire sample to contribute to a meta‐analysis for smoking reduction measured by cigarettes per day (CPD). At the end of bupropion treatment, there was a significant reduction of CPD in the bupropion group compared to controls (three trials, N = 184; MD ‐10.77, 95% CI ‐16.52 to ‐5.01, I² = 40%; Analysis 1.6). One study reported a separate analysis for participants who had not quit smoking; those who received bupropion had a significant reduction in CPD compared to those who received placebo (*Evins 2005). Another trial, which did not provide raw data for meta‐analysis, also reported a significant reduction in self reported CPD in the bupropion group versus the placebo group (*George 2002). At six months after starting bupropion, two studies provided sufficient data for meta‐analysis. At this point there was no significant difference in the number of CPD between the bupropion and placebo groups (two trials, N = 104; MD 0.40, 95% CI ‐5.72 to 6.53, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.7).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bupropion versus placebo, Outcome 6 Reduction ‐ Change in number of CPD from baseline at the end of treatment (secondary outcome) ‐ abstinence studies.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bupropion versus placebo, Outcome 7 Reduction ‐ Change in number of CPD from baseline at 6‐month follow‐up (secondary outcome) ‐ abstinence studies.

1.2 Pharmacological intervention ‐ transdermal nicotine patch (TNP)

One trial compared the use of high dose TNP (42 mg) with regular dose TNP (21 mg) in 51 patients with schizophrenia who wanted to quit smoking (*Williams 2007). There was no placebo control group. Seven‐day point prevalence abstinence rates at eight weeks were not significantly different between the high dose group (32%) and the regular dose group (23%). Survival analysis examining time to first relapse back to smoking also did not differ between the two groups. However, the authors reported that tolerability and compliance was good for both groups.

Another trial in Taiwan (*Chen 2012) investigated the effect of different doses of TNP (31.2 mg for the first four weeks, then normal 20.8 mg for the next four weeks, (high dose)), compared 20.8 mg for eight weeks (low dose) among 184 patients with schizophrenia in the chronic wards of two psychiatric hospitals. Their motivation and readiness to stop smoking were variable. Seven‐day abstinence rates at week eight were higher in the low dose compared to the high dose TNP group, although the difference was not significant (low dose: 4.3%; high dose: 1.1%). The investigators reported that the low dose TNP group reduced smoking by three more cigarettes on average, compared to the high dose group, although it is likely that this included people who succeeded in quitting entirely. There were no statistically significant differences between expired CO level and FTND scores between the two groups at the end of the intervention. There were also no significant differences between the two groups in positive and negative symptom scores.

Two other studies examined the effect of TNP together with non‐pharmacological interventions (*Baker 2006; *Gallagher 2007). In *Gallagher 2007, the smoking abstinence rate at the end of the trial (36 weeks) was significantly higher in participants who used TNP compared to those without TNP; both groups also received money as contingent reinforcement. Results of these two studies are summarised in the 'combined interventions' section below.

1.3 Pharmacological intervention ‐ Varenicline

Intervention rationale: Varenicline is a nicotinic acetylcholine α4β2 receptor partial agonist and an α7 full agonist. Varenicline is effective in treating tobacco dependence and its efficacy is probably superior to bupropion (Cahill 2012). The main adverse effect of varenicline is nausea, but this tends to subside over time. There has been concern that varenicline may be associated with psychiatric symptoms including hostility, aggression and suicidal behaviour and psychosis among individuals with and without psychiatric disorders. In February 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration issued a public health advisory, reporting an association between varenicline and an increase in neuropsychiatric adverse events (FDA 2008). This warning continues to be in place after a recent review (FDA 2011).

Abstinence outcomes

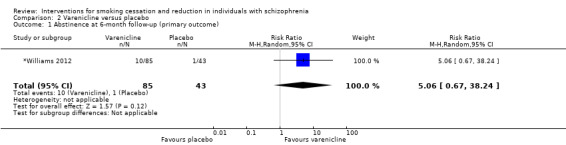

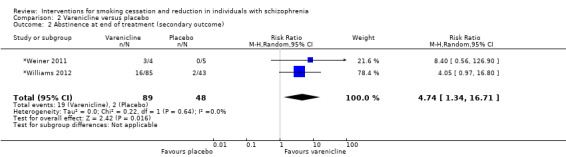

Two trials with a total of 137 participants reported smoking abstinence rates after 12 weeks of treatment with varenicline (*Weiner 2011; *Williams 2012). Both trials set the target quit date (TQD) at around one week after the start of medication. *Williams 2012 also provided data at six‐month follow‐up after starting varenicline. According to this trial, at six‐month follow‐up, participants who took varenicline were around five times as likely to abstain from smoking compared to the placebo group. However, this result did not reach statistical significance and had a wide confidence interval (one trial, N = 128, RR 5.06, 95% CI 0.67 to 38.24, P = 0.12; Analysis 2.1). Both trials contributed data to a meta‐analysis for the secondary outcome of abstinence at the end of treatment. Participants who took varenicline were also nearly five times as likely to abstain from smoking at the end of the treatment, compared to the placebo group (two trials, N = 137, RR 4.74, 95% CI 1.34 to 16.71, I² = 0%; Analysis 2.2; Figure 4). Although the RR reached statistical significance, the confidence interval was wide. A sensitivity analysis omitting *Weiner 2011 (reported as a 'letter to the editor' rather than a full paper), resulted in the RR being reduced to 4.04, just reaching statistical significance (P = 0.05).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Varenicline versus placebo, Outcome 1 Abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up (primary outcome).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Varenicline versus placebo, Outcome 2 Abstinence at end of treatment (secondary outcome).

4.

Varenicline versus placebo: Abstinence at the end of treatment (secondary outcome)

Mental state outcomes and other adverse events

Both studies reported that there were no significant differences between the varenicline and placebo groups in positive symptoms during the trial period. *Williams 2012 also did not find any difference between the two groups in negative symptoms throughout the trial, while *Weiner 2011 reported that the two groups did not differ in depressive symptoms.

*Williams 2012 mentioned that there were 13 serious adverse events (SAEs) in 10 participants (nine from the varenicline group and one from the placebo group). In the varenicline group, two patients had three SAEs which were considered to be related to varenicline use. One patient with a history of depression and suicidal ideation, as well as a history of a suicide attempt by overdose, was hospitalised for one day following six days of using varenicline. Another patient with a history of four previous suicide attempts took an overdose and suffered a seizure for which he was hospitalised ('varenicline suicidal patient 1'). No treatment‐related adverse events were reported in the placebo group. One death was reported during the post‐therapy follow‐up period, from accidental drowning 51 days after the last dose of varenicline. The investigators did not consider this to be treatment‐related. They did not find any between‐group differences for other adverse effects, including neuropsychiatric SAEs or study discontinuations. The most common adverse events in the varenicline group were nausea (23.8%), headache (10.7%) and vomiting (10.7%). In *Weiner 2011, no participant reported any suicidal ideation at baseline or throughout the trial. The varenicline group reported worsening of constipation, insomnia and nausea, which have all been noted previously as side effects of varenicline in the general population.

Smoking reduction

*Williams 2012 reported that for non‐abstinent participants, there was a statistically significant reduction of cigarettes per day (CPD) from baseline, in favour of the varenicline group at week 12, who smoked three fewer CPD compared to the placebo group (95% CI 0.4 to 6.1, P = 0.03). The result was no longer significant at week 24. However, non‐abstainers in both groups had reduced levels of expired carbon monoxide (CO) level at week 12, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.11). In *Weiner 2011 from week four onwards the varenicline group showed a significantly greater reduction of expired CO from baseline compared to the placebo group (P = 0.02), although it was unclear whether this result included those who managed to abstain from smoking.

1.4 Non‐pharmacological intervention ‐ American Lung Association (ALA) programme in group setting versus specialised smoking cessation group therapy designed for schizophrenia (both groups receiving transdermal nicotine patch (TNP))

*George 2000 investigated the efficacy of specialised smoking cessation group therapy for patients with schizophrenia, interested in quitting. There was a borderline significant difference in smoking abstinence rate at the end of the trial (based on continuous abstinence in the last four weeks of treatment) between the American Lung Association (ALA) programme group (23.5%), and the specialised group therapy group (32.1%, P = 0.06). However, at six‐month follow‐up, the smoking abstinence rate was significantly higher in the ALA programme group (17.6%) than the specialised group therapy group (10.7%, P < 0.03). There was no statistically significant difference in the expired CO level between the two therapy groups during the course of the trial. There were also no significant differences in psychiatric symptoms or medication side effects between the ALA group and the specialised group therapy group. The authors performed a secondary analysis based on whether the participant received atypical or typical antipsychotic medications. Smoking abstinence rates at the end of the trial and at six‐months follow‐up were significantly higher in the group of patients who receive atypical antipsychotic medications.There was also a significant reduction in expired CO level with TNP in patients treated with atypical antipsychotic medications, compared to those treated with typical antipsychotics.

1.5 Non‐pharmacological intervention ‐ treatment of addiction to nicotine in schizophrenia (TANS) versus medication management (MM) (both groups receiving transdermal nicotine patch (TNP))

*Williams 2010 examined two manualised individual behavioural counselling approaches ‐ treatment of addiction to nicotine in schizophrenia (TANS) and medication management (MM), alongside TNP. There were no statistically significant differences in abstinence rates between the two groups at 12 weeks after the target quit date (TANS: 15.6%; MM: 26.2%, P = 0.22), at six months (TANS: 14%; MM: 16%, P = 0.78) and at 12 months (TANS: 12%; MM: 12%, P = 0.90). There were overall significant reductions of expired CO levels and CPD from baseline in both groups, but there were no differences in CO reduction and reduction of CPD between the two groups. The author also reported that there was a positive association between the percentage of sessions attended and the smoking abstinence rate at 12 weeks, regardless of the treatment conditions.

1.6 Non‐pharmacological intervention ‐ active repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) versus sham rTMS

Intervention rationale: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a non‐invasive technique that can induce changes in brain cortical function. High frequency (>1 Hz) rTMS to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) has shown potential as a smoking cessation therapy by reducing tobacco craving and consumption in smokers without a psychiatric diagnosis (Eichhammer 2003; Amiaz 2009).

In *Wing 2012, active rTMS (four weeks with five treatments per week) was compared with sham rTMS. Active rTMS did not increase smoking abstinence rates. While it significantly reduced tobacco craving in the first week, active rTMS did not alter craving in the following three weeks.

1.7 Combined interventions ‐ individual smoking cessation intervention (based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and motivational interview) and transdermal nicotine patch (TNP) versus routine care

*Baker 2006 compared the effect of an individual smoking cessation intervention (based on CBT and motivational interview) and TNP versus routine care in a group of patients with psychotic disorders of mixed diagnoses. All the participants expressed interest in quitting smoking. The authors provided a subgroup analysis of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (N = 169). There were no overall statistically significant differences between the treatment group and the control group in either continuous abstinence or point prevalence abstinence rates at three months, six months, twelve months and four years after the initial assessment (the authors had set the threshold for statistical significance at P < 0.01 to control for multiple comparisons). In terms of smoking reduction, there was a significant difference at three months after the initial assessment, with 42.5% of the treatment group reducing their cigarette consumption by at least 50% relative to baseline, compared with 15.7% of the control group (odds ratio 3.96, 99% CI 1.53 to 10.23, P < 0.001). However, the differences in smoking reduction between the treatment group and the control group were not statistically significant at subsequent follow‐up sessions at six months,12 months and four years after the initial assessment.

1.8 Combined interventions ‐ Contingent reinforcement (CR) using money versus contingent reinforcement and transdermal nicotine patch (TNP) versus minimal intervention

*Gallagher 2007 evaluated the effects of CR using money (with and without additional TNP) compared with minimal intervention in a group of patients with serious mental illnesses. We conducted a subgroup analysis for participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (N = 80). About 32.5% of participants expressed interest in quitting smoking. The abstinence rates at weeks 20 and 36 (the end of the trial) were significant higher in the CR with TNP group, compared with the CR group without TNP (week 20: 56.3% versus 27.8%; week 36: 50% versus 27.8%), and also versus the minimal intervention group (week 20: 10%; week 36: 10%). There was also a significantly larger reduction in Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) scores in the CR with TNP group both at week 24 and at week 36, compared with the CR group without TNP, and with the minimal intervention group. The CR with TNP group had a significantly lower expired CO level both at week 20 and at week 36 compared to the minimal intervention group. However, there was no significant difference in the expired CO level at either week 20 or week 36 between the CR groups with and without TNP. Number of CPD was lower at week 36 in the CR with TNP group compared to the minimal intervention group, but there was no statistically significant difference at week 20. There was no significant difference in the number of CPD either at week 20 or at week 36 between the CR group and the minimal intervention group, nor between the CR groups with and without TNP.

2. Trials with a primary aim of smoking reduction

2.1 Pharmacological intervention ‐ bupropion

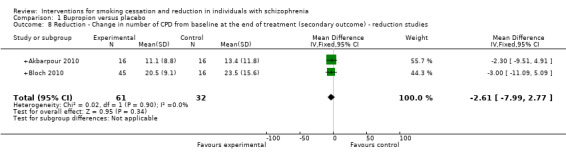

Three trials investigated primarily the effect of bupropion for smoking reduction (+Fatemi 2005; +Akbarpour 2010; +Bloch 2010). +Tidey 2011 investigated the effect of bupropion with contingency management, compared with placebo and non‐contingent reinforcement. Two trials (+Akbarpour 2010; +Bloch 2010) provided data contributing to a meta‐analysis for smoking reduction measured by number of CPD. At the end of about three months of bupropion treatment, there was no significant difference in the number of CPD between the bupropion group and the placebo group (two trials, N = 93; mean difference (MD) ‐2.61, 95% CI ‐7.99 to 2.77, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.8). +Bloch 2010 reported scores measuring positive and negative symptoms before and after the intervention, and analysis showed that there were no significant differences between bupropion and placebo groups for positive and negative symptoms at the end of the treatment. Neither trial reported any other adverse effects related to bupropion.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bupropion versus placebo, Outcome 8 Reduction ‐ Change in number of CPD from baseline at the end of treatment (secondary outcome) ‐ reduction studies.

In the cross‐over study by +Fatemi 2005, the investigators reported that at the end of the 21‐day active bupropion phase, participants showed a non‐significant trend for reductions in exhaled CO, urine cotinine and urine nicotine and metabolites, compared with the placebo phase. These participants were encouraged to reduce the amount they smoked, rather than to quit entirely. Their results also showed that during the trial, bupropion did not exacerbate positive and negative symptoms in these patients.

In +Tidey 2011, the investigators did not find that the 300 mg dose of bupropion for 22 days reduced smoking, as measured by expired CO level, urinary cotinine level and CPD. The researchers commented that their participants did not actively seek smoking cessation treatment and may have had lower motivation levels compared with other studies. They also reported that bupropion did not increase psychiatric symptoms. In addition, there were no significant differences in adverse events between the bupropion and placebo groups. There were no reports of seizure or of suicidal behaviour in the bupropion group.

2.2 Pharmacological intervention ‐ transdermal nicotine patch