Abstract

Background:

Breast cancer patients involve multiple decision support persons (DSPs) in treatment decision making, yet little is known about DSP engagement in decision making and association with patient appraisal of the decision process.

Methods:

Newly diagnosed breast cancer patients reported to Georgia and LA SEER registries in 2014–15 were surveyed 7 months after diagnosis. The individual most involved in the respondent’s decision making (key DSP) was surveyed. DSP engagement was measured across 3 domains: 1) Informed about decisions; 2) Involved in decisions; 3) Aware of patients’ preferences. Patient decision appraisal included subjective decision quality and deliberation. We evaluated bivariate associations using chi-square tests between domains of DSP engagement and DSP independent variables. We used Anova and multivariable logistic regression to compare domains of DSP engagement with patient decision appraisal.

Results:

2502 patients (68% RR) and 1203 eligible DSPs (70% RR) responded. Most DSPs were husbands/partners or daughters, white, and college graduates. Husbands/partners were more likely to be more informed, involved, and aware (all p<0.001). English- and Spanish-speaking Latinos had higher extent of (p 0.017), but lower satisfaction with involvement (p<0.001). A highly informed DSP was associated with higher odds of patient-reported subjective decision quality (OR 1.46; 95% CI 1.03–2.08, p=0.03). A highly aware DSP was associated with higher odds of patient-reported deliberation (OR 1.83; 95% CI 1.36–2.47, p<.001).

Conclusions:

In this population-based study, informal DSPs were engaged with and positively contributed to patients’ treatment decision making. To improve decision quality, future interventions should incorporate DSPs.

Keywords: breast cancer, social support, significant others, decision making, treatment

Precis:

In this population-based study using innovative methodology, informal decision support persons were engaged with and positively contributed to patients’ treatment decision making. To improve decision quality, future interventions should incorporate decision support persons.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with cancer face complex decisions spanning the cancer care continuum. Ensuring that decisions are high quality, defined as being both informed (based on accurate understanding of the options) and values-concordant (consistent with the patients’ underlying values) is a key element of patient-centered care.1,2 The importance of others, including family and friends, to achieving patient-centered care has been highlighted.3 However, relatively little is known about how informal decision support persons (DSPs)—unpaid family or friends distinct from paid caregivers and the health care team4—engage with patients in the treatment decision making process.

Patients with breast cancer report substantial informal care support even at the time of initial doctors visits. We previously found that 77% of patients had someone with them at their surgical appointment.5 We further found that while 90% reported at least one key DSP was involved in their treatment decisions, there was wide variation in the size and influence of this network.6 This raises the possibility that some DSPs are less engaged in decision making than others. However, little research has been done on DSP engagement in the medical decision-making process and even less is known about how such engagement influences the quality of patient decision making and patient outcomes. To date, most research regarding the role of others in breast cancer treatment decision making is limited by patient reports using small samples that lack racial and ethnic diversity. Furthermore, this research focuses on spouses, when nearly 40% of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients are unpartnered.7

To fill these gaps we undertook a study using a unique dataset consisting of paired data from patients with early stage breast cancer and their key DSPs. Our aims were to better understand DSP-reported engagement in patients’ treatment decision making process and to investigate associations between DSP engagement and patients’ appraisal of their treatment decisions.

METHODS

Study population

As described previously,8 the Individualized Cancer Care (iCanCare) Study is a large, population-based survey study of women with breast cancer. We accrued 3930 women, ages 20–79, with newly diagnosed, stage 0-II breast cancer as reported to the SEER registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County in 2014–2015. Exclusion criteria included Stage III or IV disease, tumors > 5cm, and inability to complete a questionnaire in English or Spanish (N= 258).

Patients were identified via rapid case ascertainment from surgical pathology reports and were mailed surveys approximately 2 months after surgery (median time from diagnosis to survey completion: 7 months). We provided a $20 cash incentive and used a modified Dillman approach, including post-card reminders and phone reminders with the option to complete the survey during a phone interview in Spanish or English.9–11 All materials were sent in Spanish and English to those with Spanish surnames.5,9 Survey responses were merged with SEER clinical data.

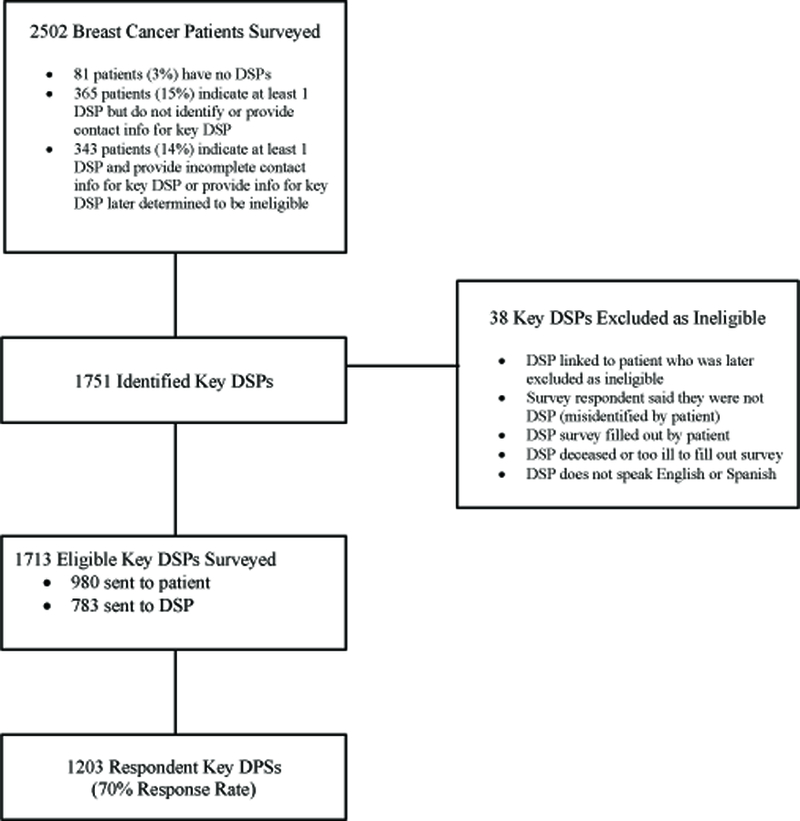

Patients were asked to complete a table describing individuals who played a key role in decisions about locoregional and systemic treatment.8 They were then instructed to think about the person who was “most helpful” in these decisions (key DSP) and asked to either: 1) provide the name and mailing address of this individual directly to our research team, or 2) receive a survey packet to deliver to this individual (including mailing if needed; postage included). Eligible DSPs were 21 years of age or older, able to read English or Spanish, and resided in the United States. Study enrollment is diagramed in Figure 1. Of 1713 eligible key DSPs surveyed, 783 surveys were sent directly to the DSP and 930 were given to DSP via patients.

Figure 1:

Flow of Decision Support Persons (DSPs) into the Study, Starting with the Initial Patient Sample.

The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and the state and institutional (Emory University and University of Southern California) IRBs of the SEER registries.

Measures

Questionnaire content was developed based on a conceptual framework derived from research on couples dealing with cancer developed by Northouse,12 and informed by research on the role of others in decision making.7,13–15 We utilized standard techniques to assess content validity, including expert reviews and cognitive pretesting and pilot testing of measures in selected patient and DSP populations.

DSP Engagement:

Guided by our conceptual framework, we asked DSPs about 3 domains of engagement in decision making developed from the concept of patient-centered care: 1) feeling informed about decisions; 2) feeling involved in decisions (extent of and satisfaction with involvement); 3) feeling aware of patients’ underlying values and treatment preferences. The items that comprise each domain are based on existing measures or prior studies of breast cancer patients,7,15–19 our work surveying significant others,15 and our cognitive pretesting and piloting in preparation for this study. We used factor analysis, Cronbach’s alphas, and Item Response Theory to assess each domain of DSP engagement and re-scaled each domain to a 5-point scale for ease of use.

Table 1 shows the specific items that comprise each domain of engagement. The domain of feeling informed was measured by asking DSPs whether they had received enough information about various aspects of therapy (y/n). Responses were tabulated as a count of the number of items for which DSPs responded that they received enough information and scored from 0–5 (Cronbach alpha=0.82), with higher scores indicating a higher degree of being informed.

Table 1.

Domains of DSP-Reported Engagement in Treatment Decisions

| Domain | Definition | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Informed | Knowledge of risks & benefits of treatment options | When her treatment decisions were being made, did you get enough information about (y/n): • Risks/benefits of surgical treatment options • Coping with your loved one’s/friend’s cancer & treatment • Helping your loved one/friend manage side effects • Long-term effects of treatment • Risk of breast cancer recurrence |

| Involved | Extent of involvement in decision making |

During the treatment making process how often did you (5-pt scale: Never -Very Often): • Attend doctor appointments where decisions about her treatment were discussed • Take notes for her during a doctor’s appointment • Talk to her about treatment options • Share information with her from other sources about treatment options (e.g., from the internet) • Help her manage side effects • Help take her to follow up appointments |

| Satisfaction with involvement in decision making | Would you say you (5-pt scale: Not at all - Very Much): • Would like to have had more information when making treatment decisions • Would like to have participated more in making treatment decisions • Are satisfied with the amount of involvement you had when your loved one/friend was making treatment decisions • Are satisfied that you were adequately informed about the issues important to the decision about treatment |

|

| Aware | Of patients’ preferences and values | How much did your loved one/friend talk to you about how she felt about the pros and cons of (4-pt scale: Not at All -A Lot): • Different surgical options • Having radiation • Keeping or losing her breast(s) • Having chemotherapy |

The domain of feeling involved was measured by asking DSPs to report on the extent of and satisfaction with their involvement in the decision making process. Extent of involvement was measured by 6 items asking DSPs how often they attended appointments, took notes, talked or shared information about treatment options, helped manage side effects, and took the patient to appointments (5-pt Likert scale, Not at All to Almost Always). Responses to these items were averaged to create a composite scale (Cronbach alpha=0.80), with higher scores indicating greater involvement. Satisfaction with involvement was measured by 4 items asking DSPs’ level of satisfaction with their involvement in patients’ decisions (5-pt Likert scale, Not at All to Very Much). Responses to these items were averaged to create a composite scale (Cronbach alpha=0.83), with higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction.

The domain of feeling aware was measured by 4 items asking DSPs how much the patient discussed treatment preferences with them (4-pt Likert scale, Not at all to A Lot). Responses to these items were averaged to create a composite scale (Cronbach alpha=0.76), with higher scores indicating higher levels of awareness. All four scales were rescaled to range from 0 to 5, for ease of comparison.

Other DSP Variables:

DSPs were asked to specify their relationship to the patient and were then categorized into DSP types: husband/partner, daughter, other family member, or friend/other non-family member. DSPs also reported their age, race and ethnicity (including primary language spoken among Latino DSPs), and educational attainment (high school graduate or less, some college, college degree or more). We also assessed DSPs’ objective knowledge about different treatment options using a validated 5-item knowledge scale for locoregional treatment20 adapted from a prior 12-item knowledge scale.21

Patient Independent Variables:

Because of expected co-linearity between DSP and patient sociodemographic factors, only relevant patient clinical factors were included in these analyses. Patients reported their comorbid health conditions (0, 1+) and their cancer treatment, consistent with prior work,22 including receipt of chemotherapy (y/n), radiation therapy (y/n), and primary surgical treatment (lumpectomy, mastectomy). Breast cancer stage (0, I, II) was obtained from SEER.

Measures of Patient Appraisal of Decision Making:

We assessed two related but distinct domains of patients’ appraisal of their own decision making: 1) subjective decision quality (SDQ), and 2) deliberation, or extent of “thinking through” the treatment options. As previously reported,23,24 SDQ was measured using a 5-item scale assessing the degree to which patients felt informed, involved, satisfied and not regretful with the locoregional treatment decision making process. Deliberation was measured using a 4-item scale developed from a public deliberation scale6 assessing the degree to which patients thought through their treatment-related decisions. Consistent with prior studies, both measures were dichotomized with high and low cut points; an overall SDQ score > 4 indicated greater SDQ9,25 and an overall deliberation score > 4 a more deliberative decision.26

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed in two steps. First, we investigated decision outcomes among all patients for associations between whether or not a patient had a DSP and her SDQ and deliberation. Then, among those patients with paired data from a key DSP, we investigated the components of DSP engagement and associations between DSP engagement and patient decision outcomes. We evaluated bivariate associations using chi-square tests between each domain of DSP engagement (Informed, Involved, Aware) and DSP independent variables. We used Anova and multivariable logistic regression to compare the domains of DSP engagement with the patient-reported decision outcomes of SDQ and deliberation.

To reduce potential bias due to non-response, weights were created using a logistic regression of DSP non-response on demographic characteristics of the patients, and used in multivariable analysis.27 All statistical tests were 2-sided; p-values<0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study Cohort

Of 3,672 eligible patients surveyed, 2,502 completed the survey (68% response rate). 1203 DSPs returned surveys (70% response rate), for a final analytic cohort for this paper of 1203 patients and their corresponding key DSP. Response rates were significantly lower for DSPs of patients who were non-white, lower income, unpartnered, and in Georgia.

Decision Outcomes in Patients With and Without DSPs

Of 2502 patients who responded to the survey, 81 (3%) said they had no DSP. Compared with patients who had at least 1 DSP (whether or not they provided their contact information), patients with no DSPs had lower mean deliberation scores (mean difference 0.54, 95% CI 0.29–0.79; p<0.01). There was no significant association between whether or not patients had a DSP and SDQ (data not shown).

DSP Characteristics

Just under half (43%) of DSPs were husbands/partners; 23% were daughters, 23% were other family members, and 10% were friends or other non-family members. Most DSPs were age 65 or under, white, and college graduates, and 21% were Latino, 17% were black, and 20% had a high school education or less. Among patients, 56% had Stage I disease. Just over 30% received chemotherapy, 50% received radiation, 62% underwent lumpectomy and 38% underwent mastectomy (including unilateral or bilateral) (Table 2). Further details regarding variations in DSP type and characteristics, by patient characteristics, have been reported previously.6

Table 2:

Characteristics of Decision Support Persons (DSPs) and Patients (N=1203 DSPs and 1203 patients)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| DSP Characteristics | |

| DSP Type | |

| Husband/partner | 512 (43%) |

| Daughter | 277 (23%) |

| Other family | 268 (23%) |

| Friend/Other non-family | 122 (10%) |

|

Age | |

| ≤50 | 469 (40%) |

| 51–65 | 412 (35%) |

| >65 | 302 (26%) |

|

Race | |

| White | 629 (53%) |

| Black | 198 (17%) |

| Asian | 89 (8%) |

| Latino, English speaking | 160 (13%) |

| Latino, Spanish speaking | 99 (8%) |

| Other | 12 (1%) |

|

Education | |

| High school or less | 241 (20%) |

| Some college | 383 (32%) |

| College graduate | 563 (47%) |

| Patient Characteristics | |

|

Comorbid Conditions | |

| 0 | 800 (67%) |

| 1 or more | 403 (33%) |

|

Stage | |

| 0 | 187 (16%) |

| I | 653 (56%) |

| II | 327 (28%) |

|

Chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 371 (31%) |

| No | 811 (69%) |

|

Radiation | |

| Yes | 591 (50%) |

| No | 587 (50%) |

| Surgery | |

| Lumpectomy | 747 (62%) |

| Mastectomy | 456 (38%) |

Percents may not add to 100% because of rounding. Ns may not add to 1203 due to missing values.

Engagement Measures and Engagement by DSP Characteristics

In bivariate analyses husbands/partners were significantly more likely to report higher scores on all domains of engagement (informed, involved (extent and satisfaction) and aware) than other types of DSPs (all p<0.01). Other findings include a higher mean extent of involvement among English- and Spanish-speaking Latinos (p 0.02) compared with other racial/ethnic groups, but lower satisfaction with involvement (p<0.01). The mean score and interquartile range for each domain, as well as further details of variations in DSP engagement by DSP characteristics, are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Bivariate Analyses of the Three Domains of DSP Engagement, by DSP Characteristic

| Characteristic | Informed (Mean score 3.75, IQR 3–5) |

Involved | Aware (Mean score 3.82, IQR 2.92–5) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extent (Mean score 3.63, IQR 3–4.59) |

Satisfaction (Mean score 4.1, IQR 3.67–4.83) |

|||||||

| Mean Score | P | Mean Score | P | Mean Score | P | Mean Score | P | |

| DSP Type | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Husband/partner | 4.07 | 4.15 | 4.10 | 3.41 | ||||

| Daughter | 3.55 | 3.95 | 3.81 | 3.18 | ||||

| Other family | 3.55 | 3.71 | 3.81 | 3.23 | ||||

| Friend/Other non-family | 3.27 | 3.18 | 3.84 | 3.22 | ||||

| Age | 0.002 | 0.762 | 0.074 | 0.158 | ||||

| ≤50 | 3.52 | 3.92 | 3.84 | 3.23 | ||||

| 51–65 | 3.86 | 3.91 | 3.99 | 3.34 | ||||

| >65 | 3.98 | 3.89 | 4.02 | 3.32 | ||||

| Race and Ethnicity | 0.809 | 0.017 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 3.82 | 3.91 | 4.19 | 3.37 | ||||

| Black | 3.71 | 3.75 | 3.77 | 3.10 | ||||

| Asian Latino, English speaking |

3.53 3.55 |

3.78 3.97 |

3.37 3.82 |

3.08 3.35 |

||||

| Latino, Spanish speaking | 3.98 | 4.17 | 3.34 | 3.27 | ||||

| Education | 0.012 | 0.610 | <0.001 | 0.647 | ||||

| High school or less | 4.10 | 3.92 | 3.67 | 3.25 | ||||

| Some college | 3.79 | 3.89 | 3.96 | 3.30 | ||||

| College graduate | 3.63 | 3.93 | 4.03 | 3.31 | ||||

IQR: interquartile range

DSP Engagement and Patient Decision Appraisal

After adjustment for DSP and patient covariates, having a highly informed DSP was associated with higher odds of greater patient-reported SDQ (OR 1.46; 95% CI 1.03–2.08, p=0.03). Having a highly aware DSP was associated with higher odds of a more deliberative decision (OR 1.83; 95% CI 1.36–2.47, p<.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable Regression Models of Patient Decision Appraisal

| Subjective Decision Qualitya | Deliberationb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSP Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | Odd Ratio (95% CI) | P |

| Informed | 1.46 (1.03 – 2.08) | 0.03 | 0.76 (0.56 – 1.02) | 0.06 |

| Involved | 0.89 (0.63 – 1.38) | 0.54 | 0.92 (0.68 – 1.23) | 0.57 |

| Aware | 0.86 (0.60 – 1.23) | 0.40 | 1.83 (1.36 – 2.47) | <.01 |

| Objective Knowledge | 0.91 (0.66 – 1.27) | 0.59 | 1.25 (0.94 – 1.65) | 0.12 |

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval.

DSP race was also significantly associated with subjective decision quality.

DSP race and education, as well as patient comorbid conditions and surgery type, were also significantly associated with deliberation. Models also adjusted for DSP age, patient stage, receipt of chemotherapy, receipt of radiation, and SEER site without significant associations with patient decision appraisal.

DISCUSSION

In this study we assessed a novel construct—the engagement of key DSPs in the decision making process of breast cancer patients—in three domains: informed, involved, and aware. We found that DSPs felt highly engaged in the decision-making process and that this varied by sociodemographic characteristics of the DSPs.

Ours is the first study to suggest that among patients with a key DSP, engaging that person can have a positive influence on important decision appraisal outcomes, including subjective decision quality and deliberation. Our findings suggest that having an informed DSP may be one way to achieve better subjective decision quality. This may be because being informed is a key component of subjective decision quality, and the informed DSP contributes to that component.23 While feeling informed is not the same as possessing objective knowledge, our measure of DSPs’ objective knowledge was not associated with SDQ. Importantly, the two measures were not correlated in our data, suggesting that it may be that a DSP who feels more informed is better able to provide decision support that feels helpful to the patient.

In prior work we found that women who involved greater numbers of DSPs in their treatment decisions reported more deliberative decisions.8 We believe this analysis expands this work by showing that having a more aware key DSP was also associated with more deliberation. We acknowledge that a more deliberative decision is not necessarily a “good” one; patients and DSPs may spend a lot of time thinking through a decision and ultimately choose a treatment against the recommendation of their healthcare provider.28 Yet studies suggest the process of decision making is an important outcome in itself,29 and that feeling rushed may cause dissatisfaction with this process.23 Further work to assess the clinical outcomes of these decisions is needed.

Our results linking DSP engagement to patient reported decision appraisal have important clinical implications. The need for interventions to support patient decision making, as a means of improving decision quality and patient-centered care, has been identified.1 Our findings and limited other work suggest that in order to have the greatest impact, interventions designed to support patient decision making should incorporate informal decision supporters. We believe there may be an opportunity for decision aids to include modules for patients to view together with their DSPs, and to facilitate interaction over geographic distance for DSPs who do not live with or near the patient. Such interventions would promote DSP engagement beyond just husbands/partners, potentially translating to positive impacts on patients’ decision appraisal.

Our findings also highlight the potential for interventions aimed at DSPs themselves to support engagement with patients in treatment decision making. Such interventions could include educational modules to better meet the informational needs of DSPs and suggest meaningful ways to become involved in patients’ decision making. Exercises to improve DSPs’ awareness of patients’ values and preferences could also be included. Our finding that Latino DSPs reported higher extent of, but lower satisfaction with involvement is consistent with our prior work identifying a mismatch between actual and desired involvement in partners of Latina breast cancer patients.30 Together, these results suggest a need to help better align patient and DSP expectations and preferences for involvement in a potentially vulnerable population where language and health literacy may represent barriers to achieving optimal decision processes. Given their high reported extent of involvement, Latino DSPs may be an ideal population to include in further research as an intervention would not need to “bring them to the table,” but could instead focus on maintaining their engagement in a meaningful way. The distinct domains of DSP engagement assessed in this study together represent a taxonomy of engagement to be further explored in future research.

Although our study was a large, population-based survey in a diverse sample of patients and DSPs with high response rates, and used novel methodology to identify and survey DSPs, there are potential limitations. Recall bias is possible; to mitigate this we anchored questions around specific memorable activities. It is possible that DSPs who did not respond may have had lower engagement. Our innovative measures of DSP engagement were based on existing frameworks and subject to extensive pilot testing, but we created them de novo and they should be validated in other populations of DSPs and cancer patients. The findings for race/ethnicity should be viewed with caution because they may reflect cultural differences in how DSPs respond to the questions rather than underlying differences in engagement. Finally, our study included only women who received breast cancer treatment in Georgia and Los Angeles and their DSPs and therefore, may not be geographically generalizable.

Conclusions

Informal decision supporters are engaged in the treatment decision making processes of breast cancer patients. Such engagement is associated with positive appraisal of this process among patients, yet there are sub-groups of DSPs with low engagement. Our work has important clinical implications not just for patients, but for families, who are also affected by the cancer and treatment experience. Armed with the knowledge about the key role played by DSPs, clinicians and researchers can develop decision support tools to be used by patients along with their DSPs, as well as DSP-facing interventions to improve engagement. Ultimately, such tools may improve the quality of patients’ decision making, satisfaction with their decisions, and clinical outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the work of Alex Jeanpierre, MPH, Rose Juhasz, PhD, and the staff of SEER Georgia and Los Angeles. We acknowledge with gratitude the many patient and decision supporter participants in this study.

Funding Sources: This work was funded by grants P01CA163233 to the University of Michigan from the National Cancer Institute and RSG-14–035-01 from the American Cancer Society.

Cancer incidence data collection was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003862–04/DP003862; the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute. Cancer incidence data collection in Georgia was supported by contract HHSN261201300015I, Task Order HHSN26100006 from the NCI and cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003875–04-00 from the CDC. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors. The State of California, Department of Public Health, the NCI, and the CDC and their Contractors and Subcontractors had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Dr. Veenstra was supported by grant K07 CA196752–01 from the NCI and a Cancer Control and Population Sciences Career Development Award from the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA: Helping patients decide: ten steps to better risk communication. J Natl Cancer Inst 103:1436–43, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A new health system for the 21st Century The National Academy of Sciences; Washington, DC, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 3.in Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, et al. (eds): Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis Washington (DC: ), 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arno PS, Levine C, Memmott MM: The economic value of informal caregiving. Health Aff (Millwood) 18:182–8, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, et al. : Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 101:1337–47, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallner LP, Li Y, McLeod MC, et al. : Decision-support networks of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Cancer 123:3895–3903, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawley ST, Hamilton AS, Graff JJ, et al. : Decision involvement and choice of mastectomy in diverse breast cancer patients. J Nat Cancer Inst 101:1337–1347, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallner LP, Li Y, McLeod MC, et al. : Decision-support networks of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Cancer, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Hawley ST, Janz NK, Hamilton A, et al. : Latina patient perspectives about informed treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns 73:363–70, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, et al. : Racial/ethnic differences in adequacy of information and support for women with breast cancer. Cancer 113:1058–67, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillman DA: Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method, Wiley, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, et al. : Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin 60:317–39, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maly RC, Unmezawa Y, Leake B, et al. : Determinants of participation in treatment decision-making by older breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 85:201–209, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janz N, Mujahid M, Hawley S, et al. : Racial/ethnic differences in adequacy of information and support for women with breast cancer. Cancer 113:1058–1067, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lillie SE, Janz NK, Graff JJ, et al. : Racial/Ethnic Variation in Partners’ Perspectives about the Breast Cancer Treatment Decision-Making Experience. Oncol Nursing Forum In press, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Hawley ST, Lantz P, Janz NK, et al. : Factors associated with patient involvement in surgical treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Education and Counseling 65:387–395, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz SJ, Lantz PM, Janz NK, et al. : Patient involvement in surgical treatment decisions for breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 23:5526–5533, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CN, Chang Y, Adimorah N, et al. : Decision Making about Surgery for Early-State Breast Cancer. J Am College of Surgeons 214:1–10, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sepucha KR, Ozanne E, Silvia K, et al. : An approach to measuring the quality of breast cancer decisions. Patient Education & Counseling 65:261–269, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sepucha KR, Belkora JK, Chang Y, et al. : Measuring decision quality: psychometric evaluation of a new instrument for breast cancer surgery. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 12:51, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CN, Dominik R, Levin CA, et al. : Development of instruments to measure the quality of breast cancer treatment decisions. Health Expect 13:258–72, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friese CR, Martinez KA, Abrahamse P, et al. : Providers of follow-up care in a population-based sample of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 144:179–84, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Resnicow K, Abrahamse P, Tocco RS, et al. : Development and psychometric properties of a brief measure of subjective decision quality for breast cancer treatment. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 14:110, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez KA, Li Y, Resnicow K, et al. : Decision Regret following Treatment for Localized Breast Cancer: Is Regret Stable Over Time? Med Decis Making 35:446–57, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallner LP, Abrahamse P, Uppal JK, et al. : Involvement of Primary Care Physicians in the Decision Making and Care of Patients With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:3969–3975, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez KA, Resnicow K, Williams GC, et al. : Does physician communication style impact patient report of decision quality for breast cancer treatment? Patient Educ Couns 99:1947–1954, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grovers RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, et al. : Survey methodology (ed 2), Wiley, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scherer LD, de Vries M, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. : Trust in deliberation: The consequences of deliberative decision strategies for medical decisions. Health Psychol 34:1090–9, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elwyn G, Miron-Shatz T: Deliberation before determination: the definition and evaluation of good decision making. Health Expect 13:139–47, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lillie SE, Janz NK, Friese CR, et al. : Racial and ethnic variation in partner perspectives about the breast cancer treatment decision-making experience. Oncol Nurs Forum 41:13–20, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]