Abstract

Integration of morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular methods is often necessary for the precise diagnosis and optimal clinical management of sarcomas. We have validated and implemented a clinical molecular diagnostic assay, MSK-Fusion Solid, for detection of gene fusions in solid tumors including sarcomas. Starting with RNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor material, this targeted RNA sequencing assay utilizes anchored multiplex PCR to detect oncogenic fusion transcripts involving 62 genes known to be recurrently rearranged in solid tumors including sarcomas without prior knowledge of fusion partners. From 1/2016 to 1/2018, 192 bone and soft tissue tumors were submitted for MSK-Fusion Solid analysis and 96% (184/192) successfully passed all the pre-sequencing quality control parameters and sequencing steps. These sarcomas encompass 24 major tumor types, including 175 soft tissue tumors and 9 osteosarcomas. Ewing and Ewing-like sarcomas, rhabdomyosarcoma and sarcoma-not otherwise specified were the three most common tumor types. Diagnostic in-frame fusion transcripts were detected in 43% of cases, including 3% (6/184) with novel fusion partners, specifically TRPS1-PLAG1, VCP-TFE3, MYLK-BRAF, FUS-TFCP2, and ACTB-FOSB, the latter in two cases of pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, representing a novel observation in this sarcoma. Our experience shows that this targeted RNA sequencing assay performs in a robust and sensitive fashion on RNA extracted from most routine clinical specimens of sarcomas thereby facilitating precise diagnosis and providing opportunities for novel fusion partner discovery.

Introduction

Bone and soft tissue tumors constitute a heterogeneous group of both benign and malignant neoplasms with distinct clinical, histological and genetic characteristics (1). Integration of morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular methods is often necessary for a precise diagnosis and subsequent clinical management. In the last several years, identification of chromosomal translocations and fusion genes has substantially contributed to diagnostic precision, enabling better understanding of the genetic mechanisms underlying sarcomagenesis, thus leading to better risk stratification and development of novel therapeutics (2, 3).

Traditionally, karyotyping, fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) have been used routinely for detecting gene rearrangements. Each has its limitations, which include the need for viable cells for cell culture, use of multiple FISH probes or PCR reactions to detect multiple fusion genes, and the need to know both fusion partners for RT-PCR detection. Furthermore, the most commonly used FISH test is a break-apart probe which allows detection of only one of the rearranged genes, which can pose a diagnostic challenge when promiscuous genes such as EWSR1 are involved in the rearrangement.

We have validated and implemented a clinical gene fusion detection assay for solid tumors, designated as the MSK-Solid Fusion assay. It is a targeted RNA sequencing assay that utilizes the Archer Anchored Multiplex PCR (AMP™) technology and next generation sequencing to detect gene fusions (4). The assay panel was designed to target 62 specific genes known to be recurrently involved in rearrangements associated with solid tumors and sarcomas, which allows targeted oncogenic fusion transcript detection without the knowledge of the corresponding fusion partners or breakpoints. The detection of fusions associated with these genes may provide diagnostic or prognostic information about the disease or identify a target for therapy with agents that are approved or available in the setting of clinical trials. Here we present our clinical experience and novel findings using the MSK-Solid Fusion assay in bone and soft tissue tumors.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted with the approval of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board protocol # 16–185A(1).

RNA Extraction and QC:

A minimum of 10 unstained slides and 1 H&E stained slide from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue were obtained for each sample and reviewed by a pathologist, who decided whether macro-dissection should be performed on a case-by-case basis depending on the tumor size, purity and the relationship of the tumor cells to the stromal cells etc. Specifically, 10ul of mineral oil was applied to each slide before scraping the tissue and placing it in 1.5ml Eppendorf tube. An additional 800ul of mineral oil was added to each tube for tissue deparaffinization. RNA extraction was then performed using the standard RNeasy FFPE Kit and protocol (Qiagen, Catalog #73504). Total extracted RNA was quantified using the Qubit Broad Range RNA Assay Kit (Life Tech., Catalog #Q10211) and also run on the TapeStation using RNA ScreenTape (Agilent, Catalog #5067–5576). Each RNA sample was tested using the Archer® PreSeq™ RNA QC Assay, a qPCR-based method for assessing RNA quality, prior to library preparation and sequencing. A Ct value >28 indicates low quality RNA and the sample is deemed insufficient for testing. Optimally, 200ng of unsheared RNA is used for the assay whenever available but testing was also attempted on all samples with at least 50ng of input RNA.

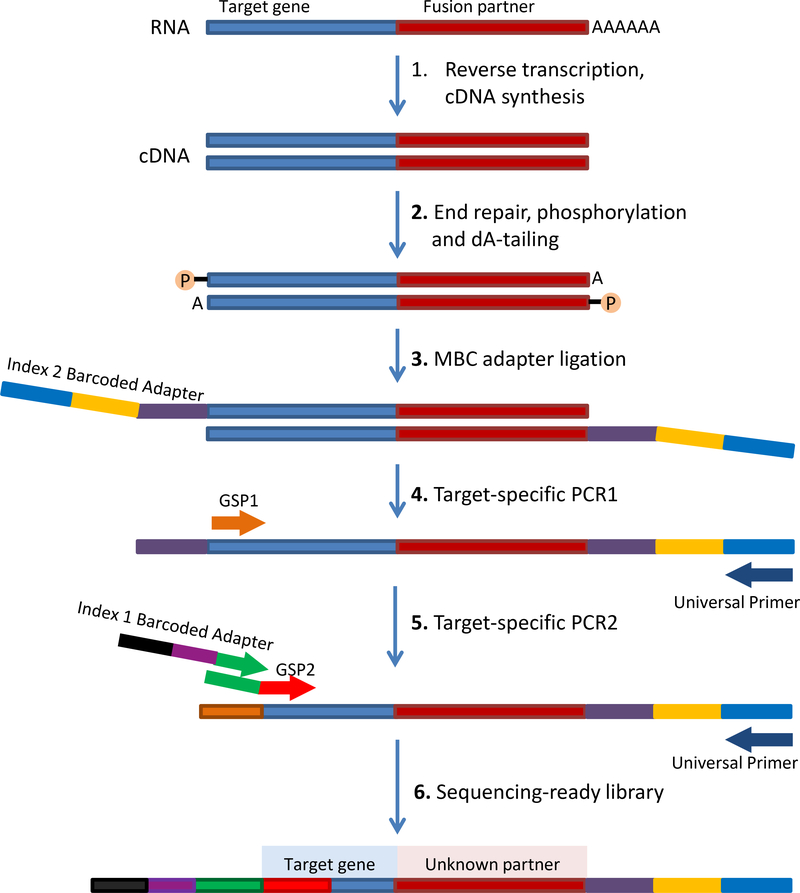

Library Preparation and Sequencing (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Schematic of Archer’s Anchored Multiplex PCR (AMP™) workflow. Adapted from www.archerdx.com. RNA is extracted from tumor formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded material followed by cDNA synthesis. cDNA undergoes end repair, dA tailing and ligation with half-functional Illumina molecular barcode adapters (MBC). Cleaned ligated fragments are subject to two consecutive rounds of PCR amplifications using two sets of gene specific primers (GSP1 pool used in PCR1 and a nested GSP2 pool designed 3’ downstream of GSP1 and used in PCR2) and primers complementary to the Illumina adapters. At the end of the two PCR steps, the final targeted amplicons are ready for 2×150bp sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer.

RNA is extracted from tumor formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded material followed by cDNA synthesis. cDNA libraries were made using the Archer™ FusionPlex™ standard protocol and supplied reagents including Archer® Universal RNA Reagent Kit for Illumina® (Catalog #AK-0040–8), Archer MBC adapters (Catalog #SA0040–45) and our custom designed Gene Specific Primer (GSP) Pool kit. Fusion unidirectional GSPs have been designed to target specific exons in 62 genes known to be involved in chromosomal rearrangements based on current literature. GSPs, in combination with adapter-specific primers, enrich for known and novel fusion transcripts (see Figure 1 for assay schematic). The assay includes 346 GSPs ranging from 18 to 39 base pairs in length designed by Archer™ to hybridize in either 5’or 3’ direction to the relevant exons of each gene. The 62 target genes, as well as those unknown fusion partners identified by MSK-Solid Fusion assay, and their corresponding NCBI RefSeq# used for gene annotation are listed in the supplementary table 4.

A detailed description of the Anchored Multiplex Technology is available elsewhere (4) and it is schematized in Figure 1. Briefly, cDNA undergoes end repair, dA tailing and ligation with half-functional Illumina molecular barcode adapters (MBC). These sequencing adapters contain molecular barcodes that allow for read de-duplication and quantitative analysis. Clean-up after all enzymatic steps are performed using AMPURE XP magnetic beads (Fisher Scientific, Catalog #NC0110018). Cleaned ligated fragments are subject to two consecutive rounds of PCR amplifications using two sets of gene specific primers (GSP1 pool used in PCR1 and a nested GSP2 pool designed 3’ downstream of GSP1, used in PCR2) and universal primers complementary to the Illumina adapters. This allows for the enrichment of fusion transcripts with the knowledge of only one of the gene partners. At the end of the two PCR steps the final targeted amplicons are ready for 2×150bp sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer.

Data analysis

At the end of MiSeq sequencing, fastq files are automatically generated using the MiSeq reporter software (Version 2.6.2.3) and analyzed using the Archer™ analysis software (Version 5.0.4). The Archer™ analysis Virtual Machine (VM) was downloaded from the Archer™ website and V2P (virtual-to-physical) technology was used to convert the Archer™ analysis VM to a dedicated Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center physical server. As a result, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center physical server inherits all Archer™ analysis software settings as the VM but with greater analysis performance allowing the simultaneous analysis of multiple samples. Modifications to the vendor pipeline were not performed. A minimum of 2M-2.5M fragments are expected to be generated for each sample. Each fusion call should be supported with a minimum of 5 unique reads and a minimum of 3 reads with unique start sites. The overall time from receipt of the sample in the laboratory to reporting of results is approximately one week.

MSK-Fusion Panel validation:

The validation of the MSK-Fusion Solid panel was performed according to NYS DOH standard requirements. The panel was fully approved by NYS DOH for use in our clinical laboratory. In brief, the accuracy study included 132 unique tumor RNA samples from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections. These samples were previously profiled in our clinical laboratory and were confirmed to be positive for fusions by alternate methods. The assay called 99% of the expected fusions with high confidence. The reproducibility and precision studies included 8 samples positive for known fusions sequenced in triplicate within the same and across 3 separate runs; 100% of the expected calls were made. Finally, the analytical sensitivity of the assay was determined using 3 cell lines harboring 3 different fusions: A673 (EWSR1-FLI1), SYO1 (SS18-SSX2) and H3122 (EML4-ALK). Serial dilutions were prepared by mixing each positive sample with RNA from a normal sample previously characterized as fusion negative. The sensitivity results demonstrated that gene fusion detection sensitivity of the assay is at approximately 3% positive tumor RNA. This assay sensitivity should be viewed as an estimate, recognizing that it can also affected by differences in the expression levels of different fusions.

Circos plot

The Circos plot of all the gene fusions identified by the MSK-Solid Fusion Assay was generated using CIRCOS (5) which is available from website http://mkweb.bcgsc.ca/tableviewer/.

Results

Cohort description:

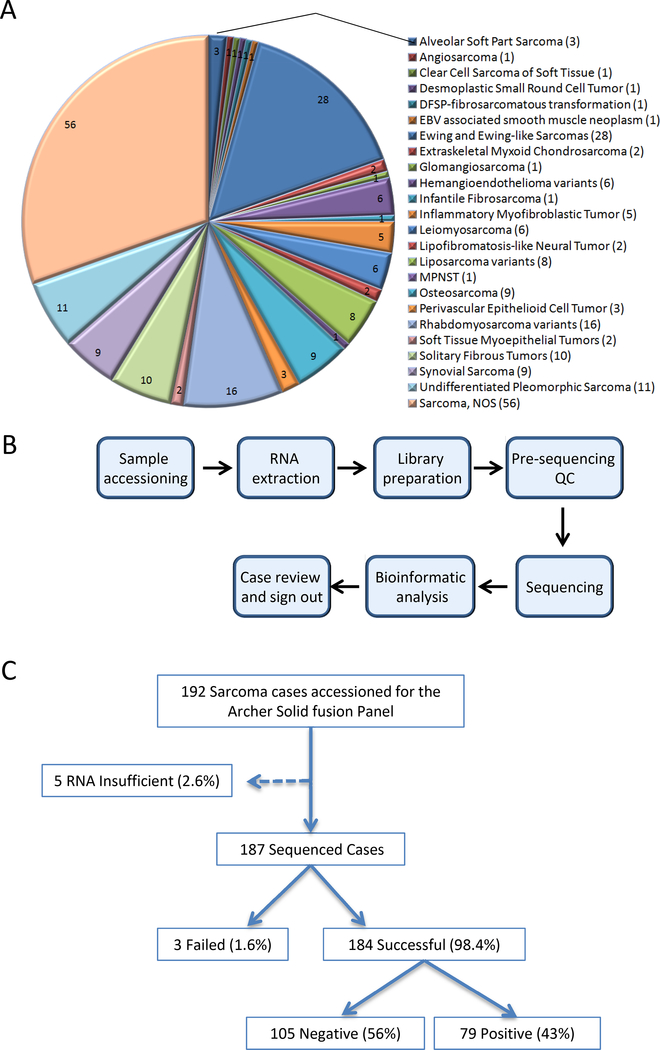

From 1/2016 to 1/2018, 192 bone and soft tissue tumors from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor material were submitted for Archer analysis and 187 successfully passed all the pre-sequencing quality control parameters (Suppl. Table 1). The successful rate for sequencing is 98%. The numbers of submitted, failed, insufficient and successful cases are summarized in Figure 2C. The tests were requested for the following reasons: 1) as part of work-up for primary diagnosis or diagnosis confirmation, 2) confirmation of fusion genes or complex rearrangements detected by MSK-IMPACT™ (a targeted Next-Generation Sequencing assay) (6), 3) for possible discovery of potential targetable rearrangements in certain tumors, including driver-negative cases by MSK-IMPACT™. In all, 184 cases were successfully sequenced. These neoplasms encompass 24 major tumor types arising from bone and soft tissue, including 174 soft tissue tumors and 9 osteosarcomas (Figure 2A). Patient demographics include 95 females and 88 males with an age range of 3 month to 87 years (median age: 40 years old) at primary diagnosis. Sarcoma-not otherwise specified, Ewing and Ewing-like sarcomas and rhabdomyosarcomas were the three most common tumor types (Suppl. Table 1). Others include alveolar soft part sarcoma, angiosarcoma, clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation, EBV-associated smooth muscle neoplasm, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, glomangiosarcoma, hemangioendothelioma, infantile fibrosarcoma, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, leiomyosarcoma, lipomatosis-like neural tumor, liposarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, osteosarcoma, perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa), soft tissue myoepithelial tumor, solitary fibrous tumor, and synovial sarcoma.

Figure 2.

A. Pie chart demonstrating the major categories of 184 bone and soft tissue tumors successfully analyzed by the MSK-Solid Fusion Assay. The number in the parentheses indicates the number of cases in each category.

B. The workflow of the MSK-Solid Fusion Assay.

C. QC summary of all the bone and soft tissue tumors submitted for Archer analysis.

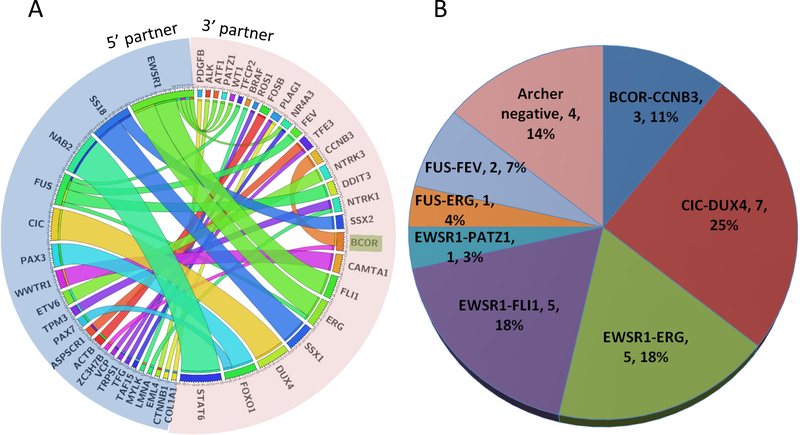

Summary of recurrent and novel gene fusions:

In-frame fusion transcripts were detected in 43% of cases (79/184) by the MSK Solid Fusion assay (Suppl. Table 1). Data from alternative methods (FISH, RT-PCR or MSK-IMPACT) were available in 43 cases which showed concordance in 38 (88%). The five discordant cases include four undifferentiated round cell sarcomas and one pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (see results and explanation in next sections). The most common gene involved in fusions is EWSR1 with different partners including ATF1, ERG, FLI1, NR4A3, PATZ1, and WT1 in various tumor types. Other commonly identified gene fusions include SS18-SSX1 or SS18-SSX2 in synovial sarcoma, NAB2-STAT6 in solitary fibrous tumor, PAX3(or PAX7)-FOXO1 in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, CIC-DUX4 in Ewing-like undifferentiated round cell sarcoma and FUS fusion to DDIT3, ERG, FEV and TFCP2 genes in different types of sarcomas (Figure 3A). The novel gene fusions include TRPS1-PLAG1, VCP-TFE3, MYLK-BRAF, FUS-TFCP2 and ACTB-FOSB. (Suppl. Table 2). In the following sections, we summarize the recurrent and novel fusions found in undifferentiated round cell and other sarcomas and describe the clinicopathological features of selected cases with novel fusions and tumors with potentially targetable fusions.

Figure 3.

A. Circos plot of the 78 gene fusions identified from all the soft tissue and bone tumors submitted for the MSK-Solid Fusion Assay. Note: BCOR can serve as either 5’ or 3’ partner gene in BCOR-CCNB3 or ZC3H7B-BCOR respectively.

B. Pie chart showing the gene fusions and fusion-negative cases from 28 undifferentiated round cell sarcomas (including Ewing and Ewing-like sarcomas).

Recurrent gene fusions in undifferentiated round cell sarcomas:

Undifferentiated round cell sarcomas including Ewing sarcoma and Ewing-like sarcomas were the second most common category of neoplasms submitted for RNA sequencing analysis. In total, 28 sarcomas with a tentative diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma or Ewing-like sarcomas based on morphology and immunohistochemical findings were submitted (Suppl. Table 1). Eighty six percent (24/28) were found to harbor known gene fusions by the MSK-Solid Fusion assay, of which 12 were confirmed by either FISH or MSK-IMPACT assays. There were 4 cases where the results were discordant among MSK-Solid Fusion, FISH and MSK-IMPACT assays. Two cases negative by the MSK-Solid Fusion assay showed CIC rearrangement by FISH. The reason for these discrepancies could be due to alternative breakpoints located in regions that are not covered by the gene-specific primers in the MSK-Solid Fusion assay targeted RNAseq panel. For example, a novel CIC-DUX fusion involves exon18 of CIC (7). However, only exon19 and exon20 CIC primers in the 3’ direction are included in the MSK-Solid Fusion. For the third case, FISH was negative for EWSR1 gene rearrangement whereas both MSK-Solid Fusion and MSK-IMPACT identified a EWSR1-PATZ1 fusion. PATZ1 (aka ZNF278), encoding a zinc finger protein, is located on chromosome 22q12.2, 2 Mb distal to EWSR1. PATZ1 and EWSR1 are transcribed in an opposite direction. This fusion is a result of submicroscopic inversion occurring on chromosome 22q12 and thus could be missed by FISH (8, 9). EWSR1-ERG fusion in the fourth case of Ewing sarcoma was not detected by FISH but was detected by both the MSK-Solid Fusion and MSK-IMPACT assays. This is due to a complex and unbalanced exchange of chromosomal material between chromosomes 21and 22, where ERG and EWSR1 are located respectively. The size of the chromosomal segment transferred between chromosomes 21 and 22 is often small and can be beyond the resolution of break-apart FISH, as reported previously (10).

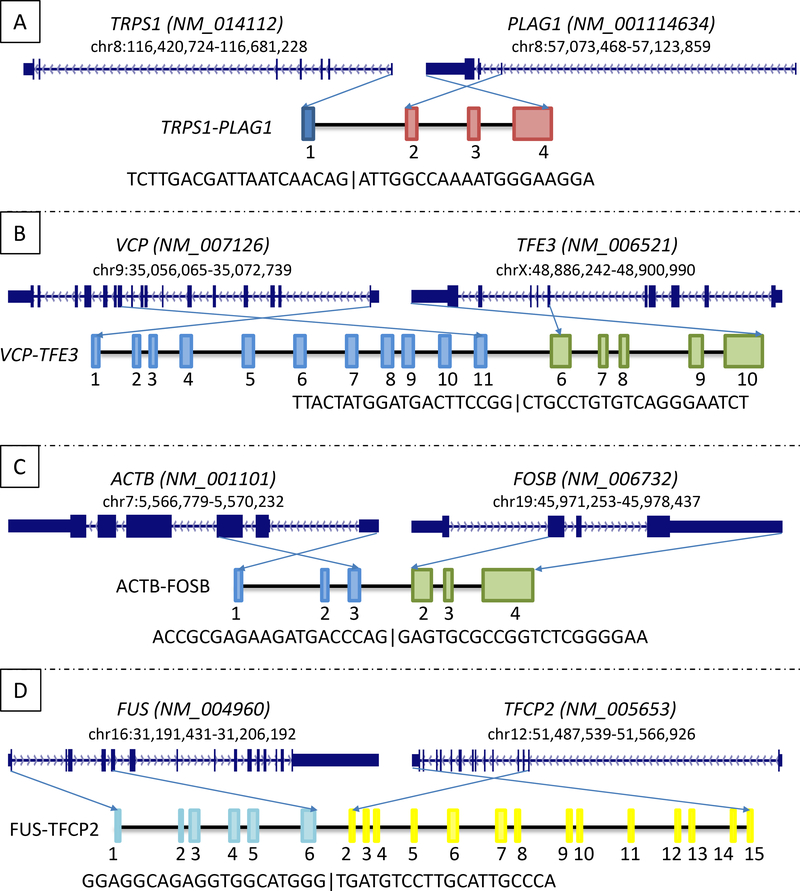

Sarcomas harboring novel fusions

Five cases were found to have gene fusions where a novel gene was discovered as a partner gene fused to a gene known to be recurrently involved in the specific tumor type. These include a myoepithelial tumor of soft tissue, a perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa), and two pseudomyogenic hemangioendotheliomas. Novel fusions were identified in two cases, one rhabdomyosarcoma and another sarcoma - not otherwise specified. These six cases are summarized as follows (Suppl. Table 2).

Case 1:

A TRPS1-PLAG1 gene fusion was identified in a myoepithelial tumor of soft tissue with break points in TRPS1 exon1 and PLAG1 exon2 (Figure 5). This tumor was a 10 × 8 × 6 cm mass arising in the forefoot of a 25-year-old male. The tumor had been stable for 8 years but rapidly increased in size in the 6 months prior to surgical resection. The tumor involved dermis, subcutaneous tissue and skeletal muscle and abutted the 5th metatarsal shaft and phalanges without invasion. An additional focus of tumor was found in the cuboid bone which was not contiguous with the soft tissue mass. No distant metastasis was found. Microscopically, both the primary tumor and cuboid lesion showed similar morphology with epithelioid to plasmacytoid cells arranged in aggregates and cords in a myxoid background. There were also scattered areas showing distinct gland formation. The tumor cells showed dense eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm with moderate nuclear pleomorphism and a mitotic activity of 2–3/10 HPFs (Figure 4A-C). Immunostains demonstrated that the tumor cells were positive for pan-cytokeratin, S100, calponin, and negative for smooth muscle actin (SMA), and CD31. INI-1 (SMARCB1) nuclear staining in the tumor cells was retained.

Figure 5.

The schematic diagrams of the novel gene fusions detected by the MSK-Solid Fusion Assay.

A.The TRPS1-PLAG1 rearrangement between genes TRPS1 exon1 and PLAG1 exon2 in a soft tissue myoepithelial tumor.

B.A VCP-TFE3 fusion between VCP exon11 and TFE3 exon 6 in a perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of pancreas.

C.The ACTB-FOSB between genes ACTB exon3 and FOSB exon2 in two pseudomyogenic hemangioendotheliomas.

D.A FUS-TFCP2 fusion between genes FUS exon6 and TFCP2 exon2 in a rhabdomyosarcoma.

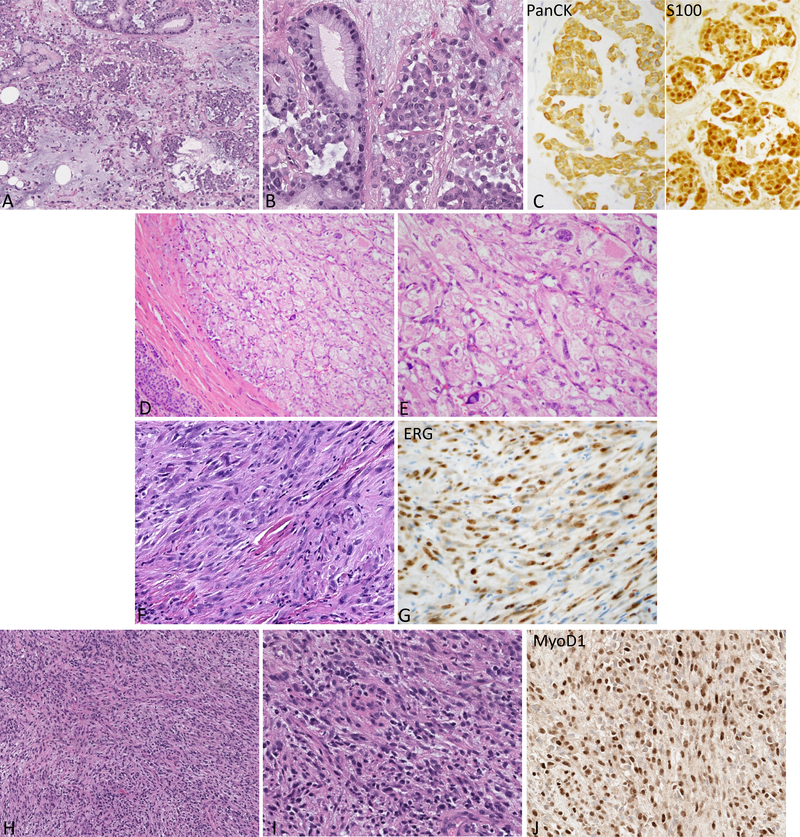

Figure 4.

Representative H&E and immunophenotype of the sarcomas with novel fusions.

A-C: Soft tissue myoepithelial tumor shows epithelioid to plasmacytoid cells in aggregates in a myxoid background with scattered areas showing distinct gland formation. The tumor is strongly and diffusely positive for Pan-CK and S100 by IHC. (A: 200x, B-C: 400x)

D-E: Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) in the pancreas. The tumor is well circumscribed at the periphery and demonstrates large polygonal cells with eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm. (D: 200x, E: 400x)

F-G: Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma composed of spindle cells with moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm and is positive for ERG immunostain. (400x)

H-J: Rhabdomyosarcoma (FUS-TFCP2) arising in the maxillary gingiva demonstrating monomorphic oval to spindle cells in an inflammatory background. The tumor is strongly positive for MyoD1 by IHC. (H: 200x, I-J: 400x)

Case 2:

In a perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) arising in the pancreas of a 69-year-old male, a VCP-TFE3 fusion was found between VCP exon 11 and TFE3 exon 6 (Figure 5). This tumor showed a pure epithelioid morphology with a nested growth pattern. The tumor cells were large and polygonal with eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm. The nuclei varied from small to very large focally and demonstrated prominent nucleoli and intranuclear inclusions (Figure 4D-E). Although the individual tumor nodules were well circumscribed, perineural invasion with multiple small clusters of tumor cells were identified. This tumor was negative for HMB45, S100, synaptophysin, chromogranin and cytokeratins while it showed focal SMA positivity with strong nuclear labeling for TFE3, which highly correlates with TFE3 gene fusions (11). FISH confirmed TFE3 gene rearrangement (not shown).

Cases 3 and 4:

A 54-year-old female presented with a small, superficial and pimple-like lesion over her right posterior deltoid region. Pathology showed a cellular neoplasm involving the dermis and subcutis composed of spindle to epithelioid cells with a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4F-G). Moderate cytologic atypia and rare scattered mitoses were noted. Tumor cells were positive by immunohistochemistry for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD31 and ERG, and had retained INI1 (SMARCB1). Ki-67 stain showed a low proliferation activity of 5%. A novel ACTB-FOSB fusion was detected between ACTB exon3 and FOSB exon2 (Figure 5), supporting the diagnosis of pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma. However, FISH using break-apart probes flanking FOSB gene was negative. This could be due to a complex gene rearrangement not apparent by FISH or insertion of portion of the ACTB gene into the FOSB locus or other alternative mechanism. Alignment of the sequence from the fusion identified a 68-bp duplication of the junction region of ACTB-FOSB fusion, which includes 13 bp of 3’ end of ACTB exon3 and 55 bp of 5’ end of FOSB exon2 (data not shown).

The second pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma with ACTB-FOSB fusion was found in a 15-year-old boy who presented with complete collapse of his T2 vertebral body. Imaging showed a destructive lesion centered within the T2 vertebral body with evidence of cortical disruption and extension into the surrounding soft tissue. Pathology showed a cellular proliferation of spindle to epithelioid cells with moderate eosinophilic cytoplasm arranged in a somewhat fascicular pattern. Moderate cytologic atypia and slightly increased mitotic activity was noted (8/10 HPF). The neoplastic cells were strongly and diffusely positive for ERG, positive for AE1/3 and CAM5.2, variably positive for CD31 and SATB2, and negative for S100, SMA, desmin and CD34. INI1 showed retained nuclear expression. The same ACTB-FOSB fusion was detected between ACTB exon3 and FOSB exon2 by MSK-Solid Fusion assay. The sequence from the fusion aligned perfectly with ACTB and FOSB in the reference genome.

Case 5:

A 74-year-old woman presented with a lesion growing on her right maxillary gingiva, CT imaging showed 4.0 × 2.5 × 2.1 cm expansile lytic lesion within the right maxillary alveolar ridge extending beyond midline and involving the hard palate and regional metastasis to the neck. The lesion showed a cellular neoplasm composed of oval to spindle cells in an inflammatory background with frequent mitotic figures and focal necrosis. The cells were monomorphic with minimal pleomorphism (Figure 4H-J). Immunohistochemical stains showed that the tumor cells were diffusely and strongly positive for Caldesmon, SMA, Desmin, Factor XIIIa, ALK (not shown) and patchy-positive for MYOD1. The neoplastic cells were negative for CD34, BCL2, S100, nuclear beta-catenin, EMA and cytokeratin. The ALK positivity raised the possibility of an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. However, FISH analysis for ALK gene rearrangement was negative. Archer analysis identified a FUS-TFCP2 fusion between FUS exon6 and TFCP2 exon2 (Figure 5). The morphological and immunohistochemical findings were most consistent with rhabdomyosarcoma. Recently, two similar cases with the same morphology and gene fusions have been described and referred to as “epithelioid rhabdomyosarcoma” (12).

Case 6:

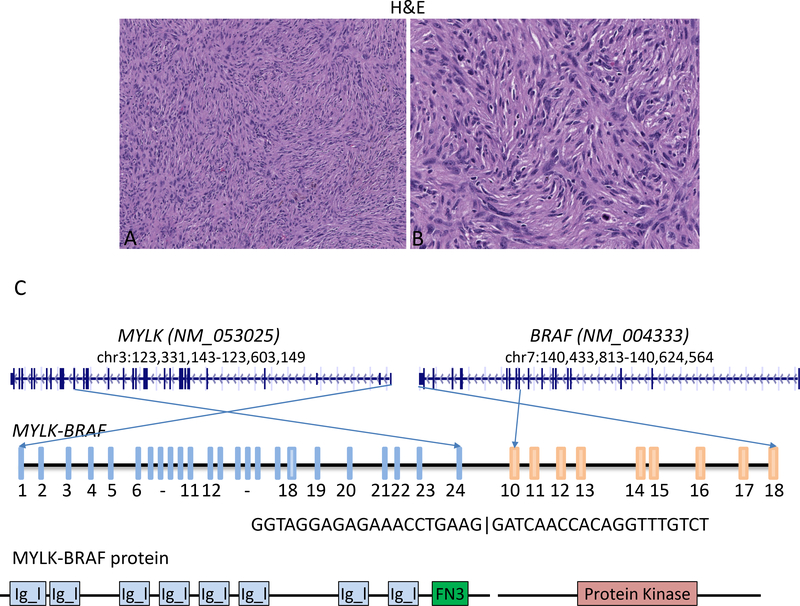

A 54-year-old female with clinical history of uterine leiomyoma and myomectomy, presented with cough and hemoptysis. PET scan showed multiple metastatic tumors to the lung and bones. A lung biopsy was performed and showed a tumor composed of a mixture of spindled to epithelioid cells in a whorling and storiform growth pattern (Figure 6). The tumor cells demonstrated focal moderate to severe atypia and a high mitotic count (up to 38/10 HPF). The tumor cells were strongly positive for CD10 and moderately positive for CyclinD1, while negative for both epithelial or mesenchymal markers (ER, PR, SMA, Myogenin, Desmin, Caldesmon, EMA, Myoglobin, AE1/AE3, CK5/6, CK7, CK20, PAX8, RCC, ERG, S100, HMB45, MelanA, WT1, beta HCG, CA125, CD21, CD31, CD34, CD45, CD99, CD117 , ALK, CDK4 and MDM2) by immunohistochemistry. A MYLK-BRAF fusion was identified by fusion assay. The rearrangement resulted in a fusion between MYLK exon24 and BRAF exon10, and thus the predicted fusion protein includes BRAF protein kinase domain (Figure 6). A primary site could not be found on clinical work-up and the patient’s hysterectomy specimen was not available.

Figure 6.

Representative H&E images (A-B) of the metastatic sarcoma-not otherwise specified to the lung with unknown primary site. The tumor shows a mixture of spindled to epithelioid cells in a whorling and nodular growth pattern. (C) Schematic diagrams of the novel fusion MYLK-BRAF joining MYLK exon24 to BRAF exon10. The BRAF protein kinase domain is included in the predicted fusion protein. (Magnification: A: 200x, B: 400x) Protein domain info taken from http://www.uniprot.org/

Igl: immunoglobulin-like domain

FN3: Fibronectin type-III domain

Tumors with potentially targetable fusions

In addition to MYLK-BRAF fusion described above, eight more sarcomas were found to harbor gene fusions including the kinase domain of a protein kinase (Suppl.Table 3). The well-known gene fusion between ETV6 exon5 and NTRK3 exon15 was detected in an infantile fibrosarcoma and two inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (13, 14). A TFG-ROS1 fusion between genes TFG exon4 and ROS1 exon35 was found in the third inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (14, 15). The fourth inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors had an EML4-ALK fusion between EML4 exon2 and ALK exon20, also reported previously (15). Two additional targetable fusions involving the NTRK1 kinase domain, LMNA-NTRK1 and TPM3-NTRK1, were identified in three tumors; one was a sarcoma-not otherwise specified and the other two were lipomatosis-like neural tumor (16).

Discussion

We have implemented and clinically validated a targeted RNA sequencing assay to detect multiple genes fusions using Archer FusionPlex technology (4). This custom-designed gene panel allows high-throughput and rapid identification of both recurrent and novel gene rearrangements. The advantage of this assay over other technologies is the ability to multiplex and detect both common and novel fusion genes without the need for primers specific to both fusion partners of a given fusion. In our cohort, we were able to identify the following rare events:

1) Novel partner genes for known recurrent gene fusions, which include TRPS1-PLAG1 in one soft tissue myoepithelial tumor, VCP-TFE3 in a pancreatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) and ACTB-FOSB in a pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma.

EWSR1 and PLAG1 are the most common gene partners involved in rearrangements found in myoepithelial tumors and mixed tumors arising in soft tissue and skin respectively (17). Documented fusion partners for EWSR1 include POU5F1, PBX1, ZNF444, ATF1 and PBX3 while PLAG1 has been found to fuse with CTNNB1 and LIFR (17, 18). In this study, we found a novel PLAG1 fusion partner gene, TRPS1, forming a TRPS1-PLAG1 fusion in a soft tissue myoepithelial tumor. TRPS1 is located on chromosome 8q12.1 and encodes a GATA-like zinc finger transcription factor that represses GATA-regulated gene expression (19, 20). TRPS1 has been reported to be frequently amplified in prostate and breast cancers (21). Our myoepithelial tumor showed similar morphology with distinct focal gland formation often seen in PLAG1-rearranged tumors (18).

The genetic alterations underlying perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) include inactivation of TSC1/TSC2 genes or TFE3 gene fusion (22, 23). SFPQ-TFE3 is the most common rearrangement found in fusion-associated perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa). Other reported rare partner genes are DVL2 and NOVO (24). Our study revealed VCP as a novel partner fused to TFE3 in this fusion-driven perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa). VCP encodes valosin-containing protein, an ATPase in the AAA (ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities) family. VCP has very diverse cellular functions including protein degradation, membrane fusion, DNA damage repair, cell cycle control, NF-κB pathway activation and autophagy etc (25, 26). The nested growth pattern with epithelioid cytology seen in our case is in keeping with the common morphology in TFE3 translocation-driven perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) (22). Unlike usual perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas), this tumor did not exhibit melanocytic markers. Another differential diagnosis with the morphological pattern and TFE3 rearrangement is alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS). However, the location of this tumor in a visceral organ and the presence of a TFE3 fusion other than the ASPSCR1-TFE3 (a.k.a. ASPL-TFE3) universally seen in all ASPS reported (27), makes this diagnosis unlikely in this case.

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma or epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma is a rare malignant vascular tumor most commonly arising from soft tissue or bone in the extremities (28, 29). It affects predominantly males between 20–50 years of age and characterized by multifocality and indolent clinical behavior (29). Morphologically, tumor cells are epithelioid with abundant pink cytoplasm giving the appearance of rhabdomyoblasts. All cases show co-expression of cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and endothelial markers including FLI1, ERG and CD31. After the initial discovery of a balanced t(7;19)(q22;q13) translocation in two cases (30), subsequent RNA sequencing discovered a novel SERPINE1-FOSB fusion from 2 cases (31). Diffuse nuclear positivity of FOSB was observed in 96% of pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (32), suggesting FOSB is likely the target gene involved in most pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma. We identified ACTB-FOSB as a novel fusion in two cases of pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma. The fusion is between ACTB exon3 and FOSB exon2. The breakpoint in FOSB is the same as previously reported, which supports the diagnosis (31).

The detection of gene fusions involving kinase genes can identify a target for therapy using agents that are approved or available in the setting of clinical trials. Gene fusions involving NTRK1, NTRK3, ROS1 and BRAF protein kinase domains were identified in various tumor types. The two cases of lipomatosis-like neural tumor which showed TPM3-NTRK1 and LMNA-NTRK1 fusions have been published recently (16). lipomatosis-like neural tumor usually arises from the superficial soft tissue in children and young adults. It is composed of monomorphic spindle cells infiltrating the adipose tissue and which resemble infantile fibromatosis or fibrous hamartoma of infancy morphologically. Tumor cells are usually positive for S-100 and CD34 and negative for SOX10 and melanocytic markers. Recurrent gene rearrangements involving NTRK1 were found in 71% cases (16). ETV6-NTRK3 fusion was detected in one infantile fibrosarcoma and two inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. NTRK1/NTRK2/NTRK3, encoding Tropomyosin-receptor-kinase (TRK) receptors A, B and C respectively, function as nerve growth factor receptors that regulate synaptic strength and plasticity of the mammalian nervous system (33). Genetic alterations in NTRK genes have been found to be oncogenic in a variety of cancer types (13–16, 34–39). Durable clinical responses have been shown in patients with NTRK-positive solid tumors who received NTRK inhibitors (40, 41). TFG-ROS1 fusion was found in a case of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. In a recent report, a dramatic response was shown in a boy with refractory ROS1 fusion-positive inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor to crizotinib, a ROS1/ALK/MET kinase inhibitor (15). In-frame fusions involving the BRAF kinase domain, such as MYLK-BRAF, uncovered in our patient, have been found in 0.3% of tumors across multiple tumor types in two large surveys, one of 10,945 tumors [6] and the other of 20,573 tumors (42). Although the efficacy of BRAF inhibitors and other kinase inhibitors in cancers driven by BRAF fusions has not been investigated systematically, the discovery of these novel fusions expands the potentially targetable genetic alteration repertoire in sarcomas.

In conclusion, the MSK-Solid Fusion assay is a reliable single and comprehensive test for detection of known fusions, and offers the potential to uncover unknown partner genes, and some novel rearrangements including targetable fusions. Especially in sarcomas, where diagnostic difficulties remain and targetable drivers are rare, it is conceivable that new fusions can be discovered enhancing our diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by the Department of Pathology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center R&D fund and in part by the NIH/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support grant under award P30CA008748.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest

No disclosure or conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Fletcher CDM, Gronchi A, Singer S, et al. Tumours of soft tissue: Introduction In: Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F (eds). World Health Organization., International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone; 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2013, pp 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor BS, Barretina J, Maki RG, et al. Advances in sarcoma genomics and new therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:541–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mertens F, Johansson B, Fioretos T, Mitelman F. The emerging complexity of gene fusions in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2015;15:371–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng Z, Liebers M, Zhelyazkova B, et al. Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat Med 2014;20:1479–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res 2009;19:1639–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med 2017;23:703–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangray S, Somers GR, He J, et al. Primary Undifferentiated Sarcoma of the Kidney Harboring a Novel Variant of CIC-DUX4 Gene Fusion. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:1298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantile M, Marra L, Franco R, et al. Molecular detection and targeting of EWSR1 fusion transcripts in soft tissue tumors. Med Oncol 2013;30:412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mastrangelo T, Modena P, Tornielli S, et al. A novel zinc finger gene is fused to EWS in small round cell tumor. Oncogene 2000;19:3799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S, Deniz K, Sung YS, et al. Ewing sarcoma with ERG gene rearrangements: A molecular study focusing on the prevalence of FUS-ERG and common pitfalls in detecting EWSR1-ERG fusions by FISH. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2016;55:340–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Argani P, Lal P, Hutchinson B, et al. Aberrant nuclear immunoreactivity for TFE3 in neoplasms with TFE3 gene fusions: a sensitive and specific immunohistochemical assay. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:750–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson S, Perrin V, Guillemot D, et al. Transcriptomic definition of molecular subgroups of small round cell sarcomas. J Pathol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alassiri AH, Ali RH, Shen Y, et al. ETV6-NTRK3 Is Expressed in a Subset of ALK-Negative Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:1051–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto H, Yoshida A, Taguchi K, et al. ALK, ROS1 and NTRK3 gene rearrangements in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours. Histopathology 2016;69:72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lovly CM, Gupta A, Lipson D, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors harbor multiple potentially actionable kinase fusions. Cancer Discov 2014;4:889–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agaram NP, Zhang L, Sung YS, et al. Recurrent NTRK1 Gene Fusions Define a Novel Subset of Locally Aggressive Lipofibromatosis-like Neural Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:1407–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jo VY, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial neoplasms of soft tissue: an updated review of the clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and genetic features. Head Neck Pathol 2015;9:32–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Shao SY, et al. Frequent PLAG1 gene rearrangements in skin and soft tissue myoepithelioma with ductal differentiation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2013;52:675–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang GT, Steenbeek M, Schippers E, et al. Characterization of a zinc-finger protein and its association with apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1414–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malik TH, Shoichet SA, Latham P, et al. Transcriptional repression and developmental functions of the atypical vertebrate GATA protein TRPS1. EMBO J 2001;20:1715–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang GT, Jhamai M, van Weerden WM, Jenster G, Brinkmann AO. The TRPS1 transcription factor: androgenic regulation in prostate cancer and high expression in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2004;11:815–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Argani P, Aulmann S, Illei PB, et al. A distinctive subset of PEComas harbors TFE3 gene fusions. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:1395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folpe AL, Kwiatkowski DJ. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms: pathology and pathogenesis. Hum Pathol 2010;41:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Argani P, Zhong M, Reuter VE, et al. TFE3-Fusion Variant Analysis Defines Specific Clinicopathologic Associations Among Xp11 Translocation Cancers. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:723–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer H, Weihl CC. The VCP/p97 system at a glance: connecting cellular function to disease pathogenesis. J Cell Sci 2014;127:3877–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stach L, Freemont PS. The AAA+ ATPase p97, a cellular multitool. Biochem J 2017;474:2953–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ladanyi M, Lui MY, Antonescu CR, et al. The der(17)t(X;17)(p11;q25) of human alveolar soft part sarcoma fuses the TFE3 transcription factor gene to ASPL, a novel gene at 17q25. Oncogene 2001;20:48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid Sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma). Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:1088; author reply −9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trombetta D, Magnusson L, von Steyern FV, et al. Translocation t(7;19)(q22;q13)-a recurrent chromosome aberration in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma? Cancer Genet 2011;204:211–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walther C, Tayebwa J, Lilljebjorn H, et al. A novel SERPINE1-FOSB fusion gene results in transcriptional up-regulation of FOSB in pseudomyogenic haemangioendothelioma. J Pathol 2014;232:534–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hung YP, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. FOSB is a Useful Diagnostic Marker for Pseudomyogenic Hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:596–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snider WD. Functions of the neurotrophins during nervous system development: what the knockouts are teaching us. Cell 1994;77:627–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greco A, Pierotti MA, Bongarzone I, et al. TRK-T1 is a novel oncogene formed by the fusion of TPR and TRK genes in human papillary thyroid carcinomas. Oncogene 1992;7:237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haller F, Knopf J, Ackermann A, et al. Paediatric and adult soft tissue sarcomas with NTRK1 gene fusions: a subset of spindle cell sarcomas unified by a prominent myopericytic/haemangiopericytic pattern. J Pathol 2016;238:700–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross JS, Wang K, Gay L, et al. New routes to targeted therapy of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas revealed by next-generation sequencing. Oncologist 2014;19:235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaishnavi A, Capelletti M, Le AT, et al. Oncogenic and drug-sensitive NTRK1 rearrangements in lung cancer. Nat Med 2013;19:1469–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiesner T, He J, Yelensky R, et al. Kinase fusions are frequent in Spitz tumours and spitzoid melanomas. Nat Commun 2014;5:3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu G, Diaz AK, Paugh BS, et al. The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nat Genet 2014;46:444–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doebele RC, Davis LE, Vaishnavi A, et al. An Oncogenic NTRK Fusion in a Patient with Soft-Tissue Sarcoma with Response to the Tropomyosin-Related Kinase Inhibitor LOXO-101. In: Cancer Discov. Vol. 5, 2015, pp 1049–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. Efficacy of Larotrectinib in TRK Fusion-Positive Cancers in Adults and Children. N Engl J Med 2018;378:731–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross JS, Wang K, Chmielecki J, et al. The distribution of BRAF gene fusions in solid tumors and response to targeted therapy. Int J Cancer 2016;138:881–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.